Abstract

Background: The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has experienced a prolonged outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus since 2012. Healthcare workers (HCWs) form a significant risk group for infection. Objectives: The aim of this survey was to assess the knowledge, attitudes, infection control practices and educational needs of HCWs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to MERS coronavirus and other emerging infectious diseases. Methods: 1500 of HCWs from Saudi Ministry of Health were invited to fill a questionnaire developed to cover the survey objectives from 9 September 2015 to 8 November 2015. The response rate was about 81%. Descriptive statistics was used to summarise the responses. Results: 1216 HCWs were included in this survey. A total of 56.5% were nurses and 22% were physicians. The most common sources of MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV) information were the Ministry of Health (MOH) memo (74.3%). Only (47.6%) of the physicians, (30.4%) of the nurses and (29.9%) of the other HCWs were aware that asymptomatic MERS-CoV was described. Around half of respondents who having been investigated for MERS-CoV reported that their work performance decreased while they have suspicion of having MERS-CoV and almost two thirds reported having psychological problems during this period. Almost two thirds of the HCWs (61.2%) reported anxiety about contracting MERS-CoV from patients. Conclusions: The knowledge about emerging infectious diseases was poor and there is need for further education and training programs particularly in the use of personal protective equipment, isolation and infection control measures. The self-reported infection control practices were sub-optimal and seem to be overestimated.

Keywords: knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, practice, health care workers, MERS-CoV, emerging infectious diseases

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has experienced a prolonged outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus since 2012 [1,2]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) form a significant risk group for infection [3,4,5]. Most of the cases in health care workers occurred in the early period of the outbreak [6]. The risk of importation of other emerging infectious diseases, particularly with large population movements during the Hajj and Umrah is also significant.

1.2. Aim

We aimed to explore the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of healthcare workers in the Kingdom, particularly focusing on the recent disease of international significance MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

2. Methods

A survey was performed of healthcare workers in Mecca, Medina and Jeddah in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 2015. The questionnaire was developed by the primary author and pilot tested on a small number of healthcare workers. Participants were recruited from 9 September 2015 to 8 November 2015. The survey was administered on paper in either Arabic or English according to respondent preference. The responses entered into an electronic database for analysis. The content areas included MERS coronavirus knowledge and sources of information; personal experiences with MERS-CoV; opinions about the location of management of patients with emerging infectious diseases; attitudes of the HCWs to infection control practices; the educational needs of the HCWs about emerging infectious diseases; and self-reported infection control practices of the HCWs. All responses were anonymous. A Chi Square test was used to compare differences in the proportions of categorical variables. Significance was determined at the 0.05 threshold.

Ethical permission to conduct the survey was obtained from the department of medical research and studies, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (approval number A00298). This department is registered in Saudi National Committee for Biomedical Ethics (Registration number H-02-J-002).

3. Results

Of the 1500 invited to participate in the survey, responses were received from 1216 health care workers (HCW) included in this survey. This included 267 (22%), medical practitioners, 685 (56.5%) nurses, and 264 other healthcare workers, including health inspectors, pharmacists, lab technicians and radiology technicians. Of the participants, 472 (68.9%) of the nurses and 207 (77.5%) of the physicians working in primary health care centres. The majority of survey participants were Saudi (87.9%), and had diploma qualifications (64.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants and their awareness about Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

| Socio-Demographic Fetchers | Physicians | Nurses | Other HCWs * | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Number | 267 (22) | 685 (56.3) | 264 (21.7) | 1216 (100) | |

| Gender: | |||||

| Male | 199 (74.5) | 299 (43.6) | 201 (76.1) | 699 (57.5) | |

| Female | 68 (25.5) | 386 (56.4) | 63 (23.9) | 517 (42.5) | |

| Work place: | |||||

| Hospital | 57 (21.3) | 204 (29.8) | 31 (11.7) | 292 (24) | |

| PHC | 207 (77.5) | 472 (68.9) | 228 (86.4) | 907 (74.6) | |

| Other | 3 (1.1) | 9 (1.3) | 5 (1.9) | 17 (1.4) | |

| Have you heard about Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)? | p ** | ||||

| Yes | 263 (98.5) | 677 (98.8) | 261 (98.9) | 1201 | 0.906 |

| No | 4 (1.5) | 8 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) | 15 | |

| MERS has been diagnosed in patients in the practice of the HCW: | |||||

| Yes | 75 (28.10) | 218 (31.8) | 58 (22) | 351 | 0.02 |

| No | 192 (71.9) | 462 (67.4) | 203 (76.9) | 857 | |

| Don’t Know | 0 (0) | 5 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) | 8 | |

| Do you think that Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) a problem in this community? | |||||

| Strongly agree | 118 (44.2) | 362 (52.8) | 145 (54.9) | 625 | 0.105 |

| Agree | 104 (39) | 230 (33.6) | 88 (33.3) | 422 | |

| Neutral | 24 (9) | 65 (9.5) | 18 (6.8) | 107 | |

| Disagree | 17 (6.4) | 23 (3.4) | 10 (3.8) | 50 | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (1.5) | 5 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) | 12 | |

| The HCWs who had been investigated for MERS-CoV and the duration from sample taking and releasing the result: | |||||

| One day | 7 (23.3) | 54 (36.7) | 18 (45) | 79 | 0.013 |

| 2 days | 10 (33.3) | 34 (23) | 8 (20) | 52 | |

| 3 days | 9 (30) | 46 (31.2) | 9 (22.5) | 64 | |

| More | 4 (13.3) | 13 (8.8) | 5 (12.5) | 22 | |

| The impact of suspicion of having MERS-CoV on the HCWs work performance, social and psychological life: | |||||

| Work performance: | 17 (17.7) | 61 (63.5) | 18 (18.8) | 96 | 0.006 |

| Social life | 18 (16.1) | 72 (64.3) | 22 (19.6) | 112 | 0.001 |

| Psychological life | 18 (13.3) | 96 (71.1) | 21 (15.6) | 135 | 0.001 |

| Clinical experience of the HCWs in the last 2 years or less regarding: | |||||

| Working in place where MERS-CoV infected patient was diagnosed or admitted. | 75 (28.1) | 218 (31.8) | 58 (22) | 351 | 0.02 |

| Cared a MERS-CoV infected patient. | 24 (9) | 106 (15.5) | 15 (5.7) | 145 | <0.001 |

| After the MERS-CoV outbreak: | |||||

| Sometimes get scared of going to work for fear of contacting MERS-CoV patient. | 123 (46.1) | 448 (65.4) | 173 (65.5) | 744 | <0.001 |

| Sometimes avoid body contact whenever HCWs are in a public area. | 116 (43.4) | 421 (61.5) | 154 (58.3) | 691 | <0.001 |

* Healthcare Workers; ** p values represent results of chi-squared test for the null hypothesis of no difference in the Socio-demographic characteristics of participants and their awareness about MERS-CoV.

Almost all participants had heard about MERS-CoV (98.8%) and understood it to be a problem for the community (86.1%). A significant minority (28.9%) of participants had worked at facilities where MERS-CoV had been diagnosed and many respondents had personally been tested for MERS-CoV mostly due to contact with cases within or outside the workplace (Table 1).

3.1. MERS Coronavirus Knowledge and Sources of Information

Healthcare workers generally had a good understanding of the requirement to test patients admitted to ICU and those who were contacts, but a significant minority felt there was no indication for MERS-CoV investigation for the patient with acute respiratory illness requiring hospitalisation but not ICU. The majority of respondents correctly identified the need for infection prevention measures, patient risk factors and the mode of transmission by close contact. Unexpectedly, a significant proportion of respondents thought that MERS-CoV could be spread through mosquito bites. Only (47.6%) of the physicians, (30.4%) of the nurses and (29.9%) of the other HCWs were aware that asymptomatic MERS-CoV was described (Table 2).

Table 2.

Health care workers (HCWs)’ knowledge about MERS-CoV infection.

| Knowledge about MERS-CoV Infection | Correct Responses | p ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians | Nurses | Other HCWs * | Total | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Indications of testing for MERS-CoV: | |||||

| Acute respiratory illness requiring ICU | 224 (83.9) | 552 (80.6) | 188 (71.2) | 964 | <0.001 |

| Acute respiratory illness requiring hospitalisation but not ICU | 153 (57.3) | 391 (57.1) | 154 (58.3) | 698 | <0.001 |

| Mild respiratory illness not requiring hospitalisation | 170 (63.7) | 316 (46.1) | 108 (40.9) | 594 | <0.001 |

| Mild acute respiratory illness where there is a history of contact with a confirmed MERS case | 203 (76) | 409 (59.7) | 175 (66.3) | 787 | <0.001 |

| Other acute non-respiratory illness in patients with a history of contact with a confirmed MERS case | 189 (70.8) | 437 (63.9) | 153 (58.2) | 779 | <0.001 |

| MERS-CoV infection: | |||||

| About 3–4 out of every 10 people reported with MERS-CoV have died. | 149 (55.8) | 345 (50.4) | 121 (45.8) | 615 | <0.001 |

| Some infected people had mild symptoms (such as cold-like symptoms) | 212 (79.4) | 441 (64.4) | 146 (55.3) | 799 | <0.001 |

| Most of the people who died had an underling medical condition | 196 (73.4) | 407 (59.4) | 149 (56.4) | 752 | <0.001 |

| MERS-CoV has spread from ill people to others through close contact | 233 (87.3) | 530 (77.4) | 189 (71.6) | 952 | <0.001 |

| The possibility of transmission through infected camel and bats | 194 (72.7) | 340 (49.6) | 122 (46.2) | 656 | <0.001 |

| Higher risk for getting MERS-CoV or having a severe case include pre-existing conditions such as diabetes; cancer, renal failure and patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. | 235 (88) | 476 (69.5) | 165 (62.5) | 876 | <0.001 |

| The incubation period for MERS is usually about 5 or 6 days but can be more | 183 (68.5) | 333 (48.6) | 100 (37.9) | 616 | <0.001 |

| MERS is spread through mosquito bite | 159 (59.6) | 284 (41.50) | 99 (37.5) | 542 | <0.001 |

| Some infected people had no symptoms | 127 (47.6) | 208 (30.4) | 79 (29.9) | 414 | <0.001 |

| MERS-CoV infected patient need isolation | 253 (94.8) | 616 (89.9) | 228 (86.4) | 1097 | <0.001 |

* Healthcare Workers; ** p values represent results of chi-squared test for the null hypothesis of no difference in Correct responses of the HCWs knowledge about MERS-CoV infection across groups.

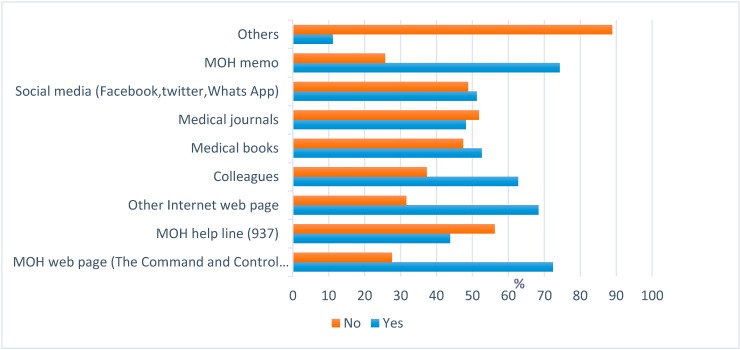

The most common sources of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome MERS-CoV information were the Ministry of Health (MOH) memo (74.3%) and MOH web page (72.4%), with smaller proportions reporting use of the MOH Helpline (937) (43.8%) and medical journals (48.2%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The most commonly used information sources of MERS-CoV by Healthcare workers (HCWs).

3.2. Personal Experiences with MERS-CoV

A significant minority of respondents reporting having been investigated for MERS-CoV. Only about two thirds of the HCWs (60.4%) received the result of their investigations in the first two days. It also, shows that, there are 351 (28.9%) of HCWs in this study work in places where MERS-CoV cases had been diagnosed in the last 2 years or less. (62%) of them are nurses, (21%) are physicians and (17%) are other HCWs. 145 (11.9) from the HCWs in this study were care sharing providers to MERS-CoV infected patients (Table 1).

Of these respondents, around half reported that their work performance decreased while they have suspicion of having MERS-CoV, a similar proportion had disturbances in their social lives, and almost two thirds reported having psychological problems during this period. Almost two thirds of the HCWs (61.2%) reported anxiety about contracting MERS-CoV from patients patient and more than half (56.8%) reported avoiding contact with others in public areas (Table 1).

3.3. Location of Management of Patients with Emerging Infectious Diseases

A high proportion of all respondent groups felt that their workplaces were not well prepared to care for patients with emerging infectious diseases, although many respondents indicated that they were personally well prepared.

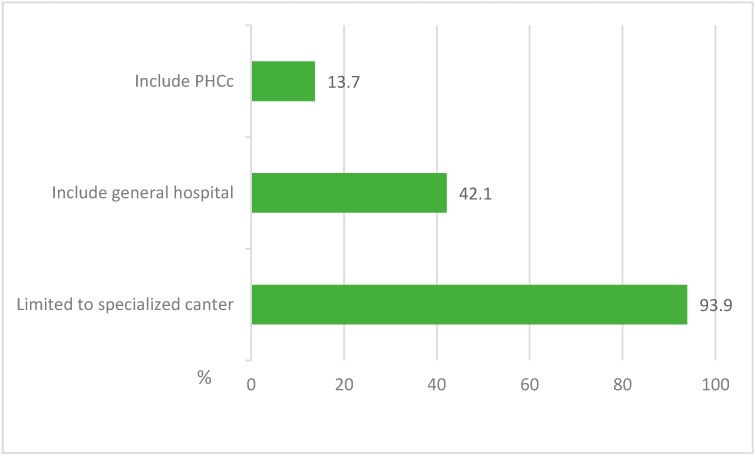

The majority of respondents believed that patients with MERS-CoV and other emerging infectious diseases should be managed in specialised centres, but a significant proportion also agreed that general hospitals also had a role in managing such patients. A minority indicated that patients with emerging infectious diseases could be managed in primary healthcare clinics (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Opinions of the HCWs about the sites that should manage the MERS-CoV and other emerging infectious disease patients.

3.4. Educational Needs about Emerging Infectious Diseases

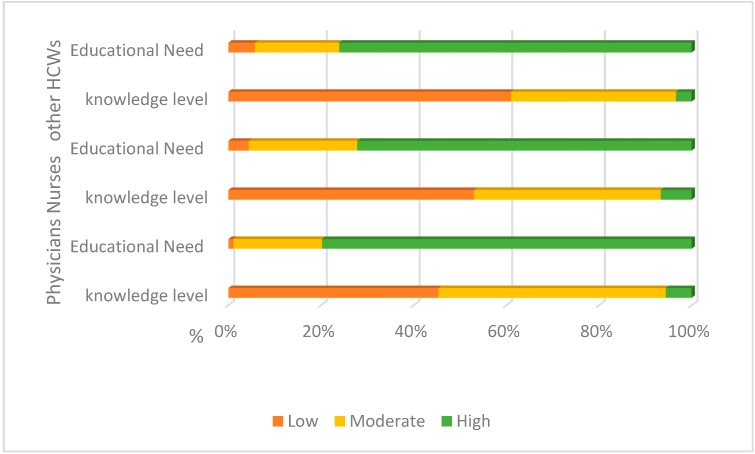

It was noted that 45% of physicians, 53% of nurses and 61% of other HCWs in the study perceive their knowledge about MERS-CoV, Ebola and others emerging infectious diseases to be low, while 40% of them indicated that it was moderate and ≤7% indicated it was high (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perception of the HCWs about the level of their knowledge and the needs of educational courses about MERS-CoV and other emerging infectious diseases.

As expected, the majority of the HCWs in the study (≥72.3%) indicated that that they are in need for educational courses and training about the MERS-CoV, Ebola and other emerging infectious diseases (Figure 3).

3.5. Attitudes to Infection Control Practices

A large majority of participants reported that they were more eager to apply infection control measures since the onset of MERS-CoV in KSA. Unexpectedly, almost two thirds of respondents were unaware of guidelines or protocols for the care of patients with MERS-CoV infection. Only 22.8% reported having received training about dealing with infectious disease outbreaks, 37.1% reported training in infection control policies and procedures, 54.4% reported training in hand hygiene and 45.6% reported training in N95 mask wearing techniques (Table 3).

Table 3.

HCWs attitudes and barriers to infection control practices following MERS-CoV outbreak.

| Self-Reporting Infection Control Practice | Physicians | Nurses | Other HCWs * | Total | p ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Hand washing after patient contact: | |||||

| Always | 161 (60.3) | 444 (64.8) | 160 (60.6) | 765 | 0.040 |

| Very Often | 69 (25.8) | 130 (19) | 50 (18.9) | 249 | |

| Sometimes | 33 (12.4) | 96 (14) | 40 (15.2) | 169 | |

| Rarely | 3 (1.1) | 11 (1.6) | 12 (4.5) | 26 | |

| Never | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 7 | |

| Wearing of surgical mask during patient contact: | |||||

| Always | 115 (43.1) | 308 (45) | 106 (40.2) | 529 | <0.001 |

| Very Often | 75 (28.1) | 157 (23) | 58 (22) | 290 | |

| Sometimes | 60 (22.5) | 162 (23.6) | 51 (19.3) | 273 | |

| Rarely | 14 (5.2) | 44 (6.4) | 32 (12.1) | 90 | |

| Never | 3 (1.1) | 14 (2) | 17 (6.4) | 34 | |

| Wearing of N95 mask during patient contact: | |||||

| Always | 118 (44.2) | 317 (46.3) | 105 (39.8) | 540 | 0.009 |

| Very Often | 57 (21.4) | 136 (19.9) | 53 (20.1) | 246 | |

| Sometimes | 38 (14.2) | 129 (18.8) | 51 (19.3) | 218 | |

| Rarely | 35 (13.1) | 76 (11.1) | 27 (10.2) | 138 | |

| Never | 19 (7.1) | 27 (3.9) | 28 (10.6) | 74 | |

| After the MERS outbreak, are the HCWs become more eager to apply infection control measures? | |||||

| Strongly Agree | 184 (68.9) | 429 (62.6) | 162 (61.4) | 775 | 0.12 |

| Agree | 72 (27) | 202 (29.5) | 78 (29.5) | 352 | |

| Do you have a guideline or protocol for caring for patients with MERS? | |||||

| Yes | 142 (53.2) | 234 (34.2) | 65 (24.6) | 441 | <0.001 |

| No | 62 (23.2) | 238 (34.7) | 98 (37.1) | 398 | |

| Don’t Know | 63 (23.6) | 213 (31.1) | 101 (38.3) | 441 | |

| HCWs training assessment: | |||||

| How to deal with an infectious disease outbreak. | 80 (30) | 152 (22.1) | 45 (17.8) | 277 | 0.011 |

| Infection control policies and procedures. | 98 (36.7) | 285 (41.6) | 68 (25.8) | 451 | <0.001 |

| Hand washing techniques. | 158 (59.2) | 389 (56.8) | 115 (43.6) | 662 | 0.001 |

| N95 mask wearing techniques. | 145 (54.3) | 317 (46.3) | 92 (34.8) | 554 | <0.001 |

| IN the last 12 months, the HCW who got an annual influenza vaccine. | 182 (68.2) | 403 (58.8) | 138 (52.3) | 723 | 0.001 |

| IN the last 3–5 years, the HCW who got Meningitis vaccine. | 209 (78.3) | 502 (73.3) | 194 (73.5) | 905 | 0.263 |

| HCW through his work career who ever had been took viral hepatitis (B) immunisation or examined for its antibodies. | 172 (64.4) | 331 (48.3) | 110 (41.7) | 613 | <0.001 |

| The barriers to infection control practices as addressed by HCWs | |||||

| Lack of knowledge about the mode of transmission of the disease MERS-CoV: | 240 (90) | 645 (94.2) | 238 (90.2) | 1123 | 0.118 |

| Not wearing mask while examine or contact with the patient: | 262 (98) | 647 (94.5) | 252 (95.5) | 1161 | <0.001 |

| No hand washing after examine or contact with the patient: | 260 (97.3) | 652 (95.2) | 250 (94.7) | 1162 | <0.001 |

| Limitation of infection control material: | 217 (81.3) | 603 (88) | 213 (80.7) | 1033 | 0.014 |

| Lack of policy and Procedures in infection control: | 227 (85) | 598 (87.3) | 236 (89.4) | 1061 | 0.003 |

| Insufficient training in infection control measurements: | 243 (91) | 633 (92.4) | 240 (90.9) | 1116 | 0.178 |

| Less commitment of health care workers to the policies and procedures: | 250 (93.6) | 659 (96.2) | 242 (98.4) | 1151 | <0.001 |

| Overcrowding in ER: | 258 (96.6) | 666 (97.2) | 246 (93.2) | 1170 | 0.010 |

* Health Care Workers; ** p values represent results of chi-squared test for the null hypothesis of no difference in HCWs attitudes and barriers to infection control practices following MERS-CoV outbreak between HCWs groups.

A high proportion of respondents agreed that emergency department overcrowding, poor hand hygiene and mask use contributed to the risk of HCW being infected with MERS-CoV. Similarly, a high proportion agreed that a lack of knowledge about the mode of transmission, a lack of policies and procedures, and insufficient training in infection control procedures also contributed to the risk (Table 3).

3.6. Self-Reported Infection Control Practices

Self-reported compliance with hand hygiene was moderate, with only about two thirds of the HCWs (60.3%) of the physicians, (64.8%) of the nurses and (60.6%) of the other HCWs practicing regular hand washing after patient contact. Less than half of respondents reported full compliance with use of surgical masks when required, and a similar proportion reported compliance with N95 respirators when required (Table 3).

Compliance with immunisation recommendations was poor, with only 59.5% self-reporting receipt of annual influenza vaccine within the last 12 months, 74.4% reporting receipt of meningococcal vaccine in the last 3–5 years, and 50.4% reporting have received hepatitis B immunisation or testing for immunity during their work career (Table 3).

4. Conclusions

The control of emerging infectious diseases in the hospitals can be limited by case detection and management using transmission-based precautions to all confirmed and probable cases. For MERS-CoV in health care settings, this requires early recognition, testing and airborne precautions [7]. In this survey we found that despite a high basic level of awareness about MERS coronavirus and the importance of infection control, there remained significant misconceptions. We have previously described more than 171 secondary cases in healthcare workers in the 939 cases reported to July 2015 with another 174 cases acquired by other patients while in hospital [8]. Another study suggested that, infected health care workers were an important group involved in disease spread [9].

This survey revealed that, about two third of the HCWs whose contact to MERS-CoV cases were investigated for possible infection, which may reflect a high index of suspicion , the anxiety about infection and accessibility to health services. This study also showed significant proportion with personal experience of MERS-CoV either as HCW at institutions caring for cases or being investigated for possible infection following contact with cases [10].

A survey of healthcare workers in South Korea found a poor level of knowledge of the modes of transmission, which was implicated in the rapid spread of the infection in hospitals. Worryingly, more than half of respondents in this survey thought that MERS-CoV could be spread through mosquito bites [10]. The infection control measures are very crucial for respiratory infectious cases in the healthcare institutes [11]. A high proportion of respondents identified hospital overcrowding, poor hand hygiene and mask use, lack of knowledge about the mode of transmission, a lack of policies and procedures, and insufficient training in infection control procedures also contributed to the risk of spread. Self-reported adherence with infection control measures was surprisingly poor, particularly in light of previous studies suggesting that self-reported adherence generally overestimates observed behaviour.

The results of this survey suggest that there was poor knowledge about emerging infectious diseases, and self-reported infection control practices were sub-optimal. However, there was recognition in respondents of the need for further education and training, particularly in the use of personal protective equipment despite the high level of trust in official sources of information. System level improvements, such as incorporation of emerging infectious diseases into medical schools and continuous medical education programs, the implementation of isolation and infection control measures, and appropriate nursing-to-patient ratios would also improve preparedness [12].

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Medical Research and Studies, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for the ethical approval of this study and General Directorate Departments of health in Makkah, Medina and Jeddah Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia for facilitating the data collection of this survey. We also appreciate the efforts of Ibrahim Asiri from Jeddah Directorate Departments of health and Tariq Al maghamsi from General Directorate Departments of health in Medina for helping us in data collection.

Author Contributions

Abdullah J. Alsahafi designed the study, obtained ethical approval, collected, entered and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; Allen C. Cheng reviewed and supervised all parts of the work. All authors have read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This work is self-funded and there is no competing financial interest of the authors.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mailles A., Blanckaert K., Chaud P., van der Werf S., Lina B., Caro V., Campese C., Guéry B., Prouvost H., Lemaire X., et al. First Cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infections in France, Investigations and Implications for the Prevention of Human-to-Human Transmission, France, May 2013. [(accessed on 21 September 2016)]. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20502. [PubMed]

- 3.Annicka R., Annette L., Christian D., Seilmaier M., Böhmer M., Graf P., Gold H., Wendtner C., Zanuzdana A., Schaade L., et al. Contact Investigation for Imported Case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20 doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A., Alabdullatif Z.N., Assad M., Almulhim A., Makhdoom H., et al. Hospital outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memish Z.A., Zumla A.I., Assiri A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in health care workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:884–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall A.J., Tokars J.I., Badreddine S.A., Saad Z.B., Furukawa E., Al Masri M., Haynes L.M., Gerber S.I., Kuhar D.T., Miao C., et al. Health care worker contact with MERS patient, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:2148–2151. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.141211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bialek S.R., Allen D., Alvarado-Ramy F., Arthur R., Balajee A., Bell D., Best S., Blackmore C., Breakwell L., Cannons A., et al. First confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States, updated information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection, and guidance for the public, clinicians, and public health authorities—May 2014. Am. J. Transplant. 2014;14:1693–1699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsahafi A.J., Cheng A.C. The epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2012–2015. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;45:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim T.H. Institutional preparedness for infectious diseases and improving care. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2015;58:606–610. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.G. Healthcare workers infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and infection control. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2015;58:647–654. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan A., Farooqui A., Guan Y., Kelvin D.J. Emerging problems in infectious diseases lessons to learn from mers-cov outbreak in South Korea. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015;9:543–546. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y. Healthcare policy and healthcare utilization behavior to improve hospital infection control after the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2015;58:598–605. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]