Abstract

A series of intra-molecular hydrogen bonded imidazoles and related heterocyclic compounds were screened for their N–H chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast properties. Of the compounds, imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides (I45DCs) were found to provide the strongest contrast, with the contrast produced at a large chemical shift from water (7.8 ppm) and strongly dependent on pH. We have tested several probes based on this scaffold, and demonstrated that these probes could be applied for in vivo detection of kidney pH after intravenous administration.

Keywords: chemical exchange saturation transfer; imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides; molecular imaging; pH imaging

1. INTRODUCTION

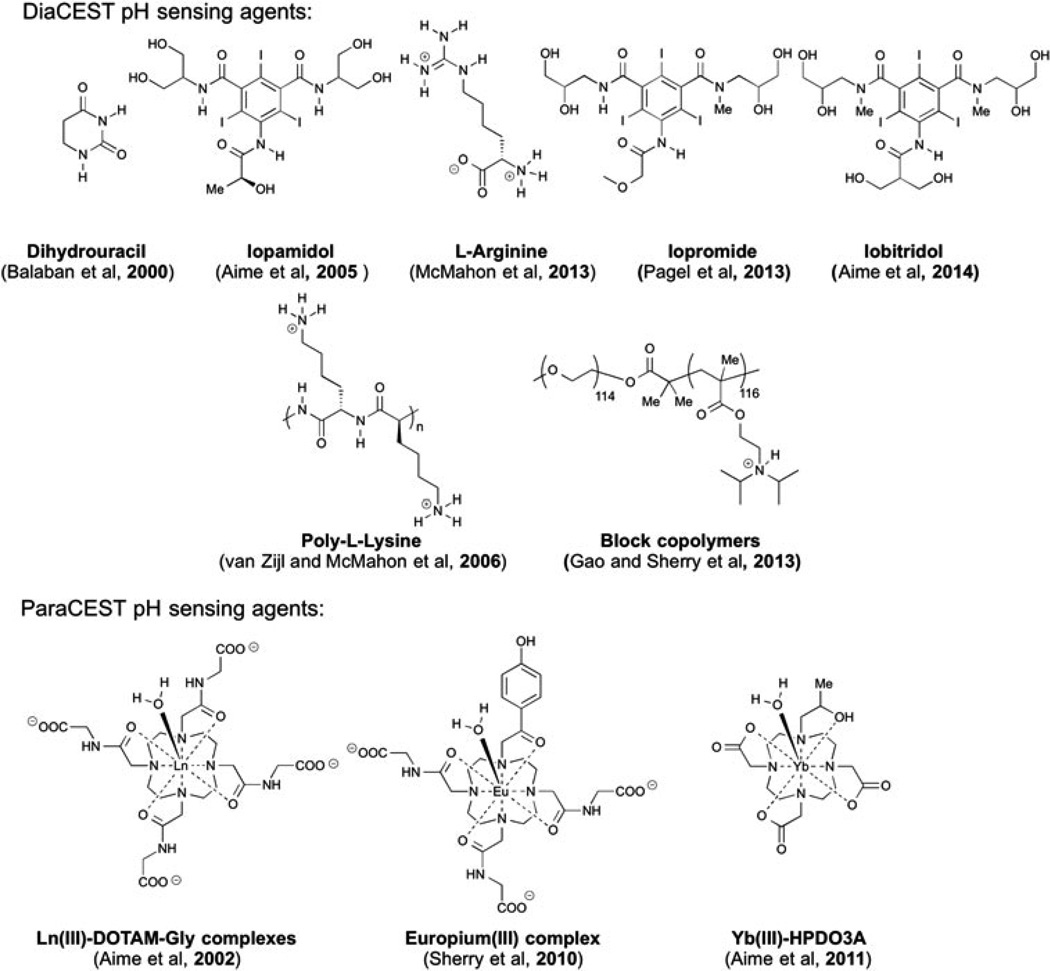

Ischemia is a common cause of acute kidney injury, with biomarkers to detect this condition an active area of research (1). Acidosis is a factor in the extension of this injury (2), and as a result pH measurements represent one promising biomarker for detection (3). Compared with microelectrode measurements, less invasive magnetic resonance (MR) methods are attractive, taking advantage of the exquisite spatial and temporal resolution that these methods provide (4). Significant progress has been made in both magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) (5–11) and relaxation based MR probes for in vivo pH detection (12–16). Recently, hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate has also been applied to MR pH imaging (17). Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) has been developed as a new method to improve the inherent sensitivity of MR (18–22). The CEST contrast mechanism involves selective saturation of labile protons on the CEST agent, followed by rapid proton exchange between these labile protons and bulk water. This process could offer several-thousand-fold signal amplification and several advantages over relaxation-based contrast agents, such as the capability of switching contrast between on and off (18–22), and simultaneous, multi-frequency detection (23–25). Several paramagnetic CEST (paraCEST) agents (26–32) and diamagnetic CEST (diaCEST) (33–41) agents have been developed as pH imaging probes. Some examples are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of paraCEST and diaCEST pH sensors.

A variety of compounds are attractive as diaCEST MRI contrast agents because of their bio-compatibility, including glucose (42,43), glycogen (44), glutamate (45), creatine (46), L-arginine (25), glycosaminoglycans (47), glycoproteins (48), nucleic acids (49–51) and peptides (24,52). However, a limitation in the sensitivity of most diaCEST agents is their small chemical shift from bulk water. Common metabolites show CEST contrast at around 1–3 ppm, which is improved to 5.5 ppm by barbituric acid (53) and thymidine analogues (50). Iodinated diaCEST/CT agents have been shown to provide exchangeable protons at about 6 ppm with a dependence on pH suitable for sensing (35,40,54), including for imaging acute kidney injury (3). As we have shown recently, it is possible to increase the shift above 6 ppm by employing the intra-molecular bond shifted hydrogens (IM-SHY principle). Previously we developed a library of diaCEST agents based on OH and NH protons in phenol and aniline derivatives (55–57). Here we were interested in designing pH sensors with large chemical shifts using IM-SHY. In particular, we report imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides (I45DCs) as new pH sensitive diaCEST agents, which can provide CEST signal at 7.8 ppm from water with improved sensitivity and specificity compared with existing agents. In addition, we have evaluated one I45DC, Compound 5, to measure the pH of kidney in mice after intravenous (IV) administration.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

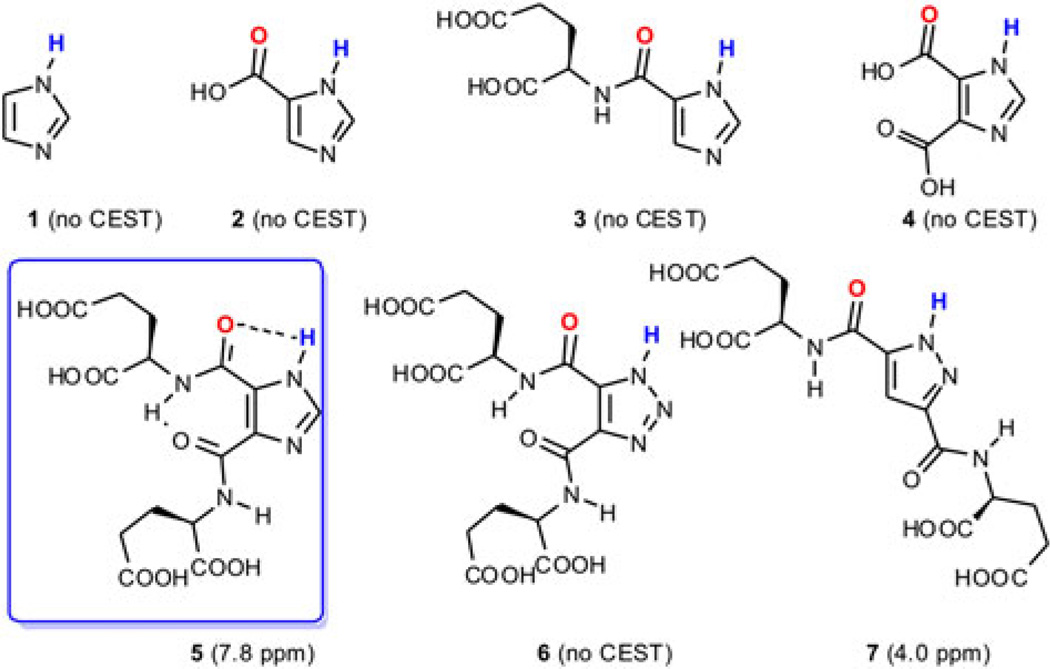

Heterocycles, including pyrrole, imidazole, pyrazole, imidazole, triazole, tetrazole and their analogues, represent another class of compounds where exchangeable protons could be provided at downfield chemical shifts due to the strong de-shielding effect from the aromatic ring and capacity for concurrent intramolecular hydrogen bonding (see below). Importantly, they are also capable of registering a response to changes in pH. For example, the chemical shift of the C-2 proton on certain N-alkylated imidazoles suggests 2-imidazole-1-yl-3-ethoxy-carbonyl propionic acid (IEPA) as an important MRS pH sensing agent (11). Inspired by this, we investigated the capacity of imidazole N–H exchangeable protons for pH sensing via CEST. However, imidazole (1, Fig. 2) gave poor saturation transfer efficiency and failed to give significant CEST contrast at neutral pH due to its fast exchange rate with water (kaw).

Figure 2.

Azole derivatives analysed for their CEST properties.

Further inspiration for the compounds shown in Fig. 2 and studied here was derived from the catalytic site of serine proteases. Such proteases have a well-defined hydrogen bonding network, which slows the exchange of the imidazole N–H groups in histidine sufficiently to allow detection through CEST contrast, with the exchangeable proton demonstrating chemical shifts as far as 13 ppm downfield from water (58,59). Aiming to decrease the kaw to the slow–intermediate exchange regime for our scanners to allow detection through CEST MRI, imidazoles were synthesized that might contain heterocyclic N–H functions as partners in an intra-molecular hydrogen bond (Fig. 2). After a series of negative results (2–4, and several other compounds listed in the Supporting Information), we found 4,5-bis[(Glu)carbonyl]-1H-imidazole (5), which provides significant contrast at 7.8 ppm downfield from water at neutral pH. Glutamate was chosen as the side chain to increase water solubility and reduce aggregation. The 1,2,3-1H-triazole analogue (6) failed to provide any CEST signal, even the expected amide signal at about 2 ppm. The pyrazole analogue (7) resonated significantly further upfield (~4 ppm, see Supporting Information) than did 5. These results suggest a critical role of the additional carbon between the nitrogens in imidazoles for balancing the pKa of the exchangeable proton and the hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, the additional hydrogen bonds in I45DC were reported to stabilize its ‘folded’ conformation by 14 kcal/mol in solution and in the solid state, which also contribute to the salutary CEST contrast properties of 5 (60,61).

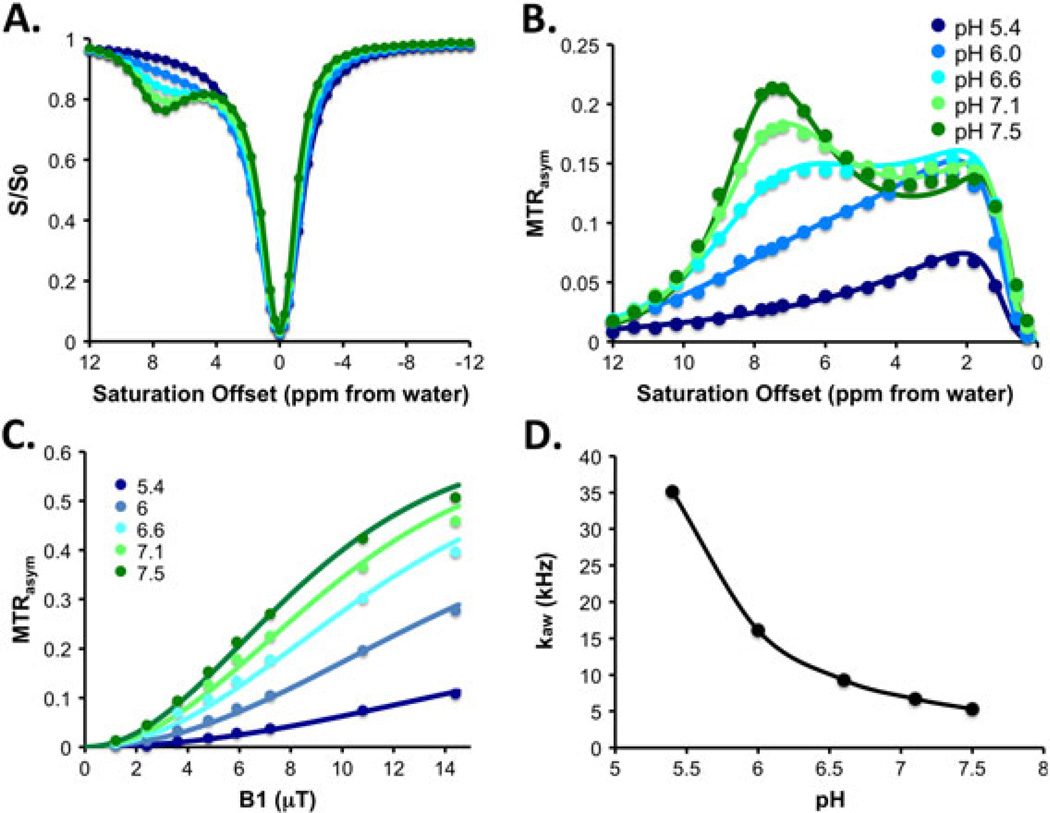

We then investigated the CEST properties of 5 in detail. As shown in Fig. 3, at fixed saturation field strengths (ω1, with ω1 = 5.9 µT shown), the CEST contrast changed significantly with pH. At pH 5.4, there was minimal contrast observed at 7.8 ppm despite the presence of significant amide CEST signal at 1.5 ppm. The contrast at 7.8 ppm increased, reaching a maximum at physiologic pH: 7% at pH 6.0, 13% at pH 6.6, 18% at pH 7.1 and 22% at pH 7.5. Above pH 7.5 the contrast decreased (see Supporting Information). This behaviour is in agreement with the acid–base properties of I45DCs. I45DCs were reported as low in basicity and exist as neutral species at pH 5–8. The imidazolium pKa in I45DCs was reported to be around 1.5 (60).

Figure 3.

Experimental data for 5. (A) Z spectra; (B) MTRasym spectra; (C) power dependence; (D) pH dependence of kaw. Experimental conditions: CEST data were obtained at 25 mM concentration, pH 5.4, 6.1, 6.6, 7.1, 7.5, tsat = 3 s, ω1 = 5.9 µT and 37 °C. For power and pH dependence measurements, ω1 = 1.2, 2.4, 3.6, 4.8, 7.2, 10.8 and 14.4 µT (see Supporting Information for additional data with more pH values).

To understand further the exchange mechanism of these compounds, the imidazole N–H kaw of 5 was determined by performing the QUESP experiment at nearly physiological pH values, as shown in Fig. 3 (36), with contrast increasing as a function of saturation field strength. At pH values of 5.4 and 6.0, the N–Hexchanged too rapidly to achieve significant signal, roughly estimated as 35 100/s and 16 100/s, respectively. The rate reduced with increasing pH and reached a minimum of 5300/s at pH7.5. These large changes resulted in pH-dependent CEST contrast. The contrast at 7.8 ppm changed from 2 to 10% from pH6.0 to 7.5 at 3.6 µT, 8% to 22% at 5.4 µT, and 10% to 27% at 7.2 µT, as shown in Fig. 3C. The large chemical shift of the labile protons, pH sensitivity and high water solubility of 5 make it a suitable as a pH sensor. The mechanism of contrast enhancement is expected to be similar to the behaviour seen previously and attributed to changes in conformation as the pH drops (60), although an additional factor impacting proton exchange includes an increase in available protons.

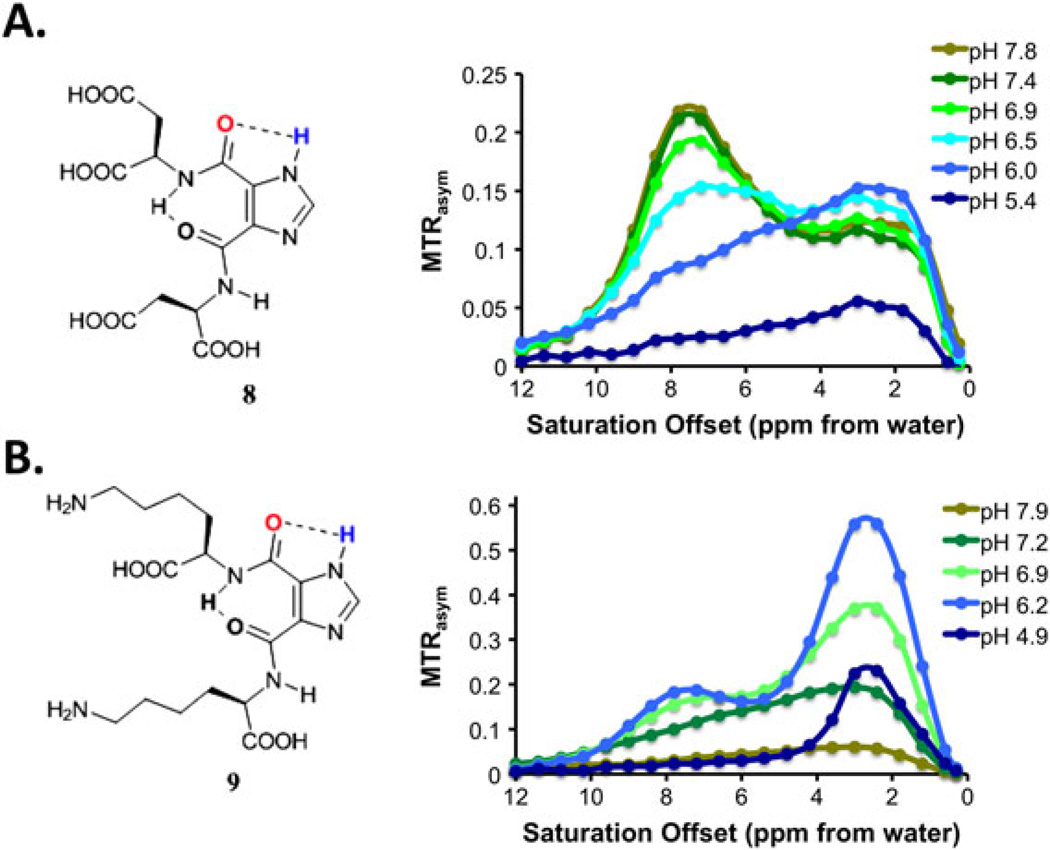

In order to test if the I45DC scaffold could tolerate chemical modification, we prepared two additional water soluble analogues. The first, 4,5-bis[(Asp)carbonyl]-1H-imidazole (8), has a very similar structure to 5. The second, 4,5-bis[(Lys)carbonyl]-1H-imidazole (9), departs somewhat from 5 by containing a free amine on the side chains. As shown in Fig. 4, 8 worked similarly to 5, with a slightly slower kaw (5000/s) at pH 7.4. On the other hand, 9 showed significant contrast at pH 6.2 but then contrast decreased with increasing pH, with kaw increasing to 12 000/s at pH 7.2. The results indicated that CEST contrast of I45DCs can be generalized to similar structures and that the pH sensitivity can be finely tuned by modifying the peptide side chains.

Figure 4.

pH dependence of 8 and 9. Experimental conditions: CEST data were obtained at 25 mM concentration; Z spectra shown are at pH 5–8, tsat = 3 s, ω1 = 5.9 µT, 37 °C.

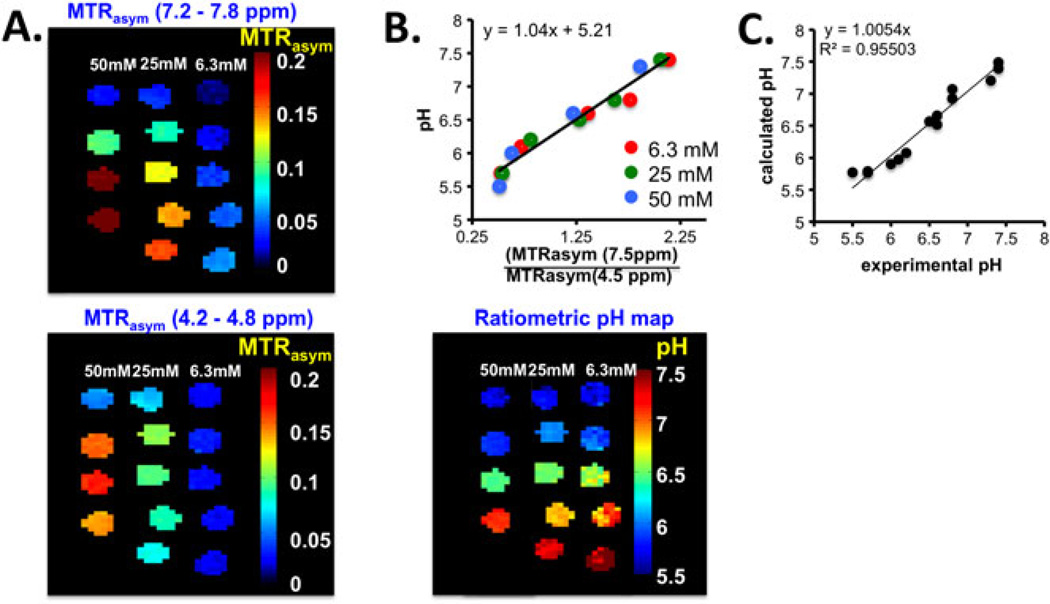

For pH sensing it is important to develop probes with signals that can be internally calibrated to take into account changes in agent concentration versus changes in pH. To take advantage of the strong but relatively pH inert (for pH 6.5–7.8) CEST signal region between 3 and 5 ppm (Fig. 3), we introduced a ratiometric method by dividing the pH sensitive signal from 7.2 – 7.8 ppm by the pH insensitive signal from 4.2 – 4.8 ppm based on the assignments in the Supporting Information. We first were interested in determining a suitable saturation field strength, and as shown in Supporting Information (Fig. S3) the contrast increased with saturation field strength well past the maximum we can achieve for Tsat = 3 s continuous wave saturation pulses using a 72 mm body transmit coil (ω1 = 5.9 µT) for both 5 and 8. Compound 5 has a faster change in ratio(MTRasym) with pH than compound 8 (Fig. S3B). Based on this, phantoms of 5 were prepared at 6.25 mM (pH 5.7, 6.1, 6.6, 6.8, 7.1, 7.4), 25 mM (pH 5.7, 6.2, 6.5, 6.8, 7.4) and 50 mM (pH 5.5, 6.0, 6.6, 7.3), and were scanned using ω1 = 5.9 µT. The CEST contrast images and pH ratiometric images are shown for comparison in Fig. 5. The results indicate that the calibrated pH images agree well with the values determined via pH electrode over a range of different concentrations. Mean-while, the image contrasts for the tubes were significantly different from each other, with contrast decreasing with decreasing pH unidirectionally over the range of interest. This consistent result encouraged us to investigate I45DCs for in vivo applications.

Figure 5.

pH calibration of 5. Experimental conditions: CEST data were obtained at 6.25 mM, 25 mM or 50 mM concentration, tsat = 3 s, ω1 = 5.9 µT and 37 °C, with physiological pH values shown in the figure. (A) CEST contrast observed at 7.2–7.8 ppm (upper panel) and 4.2–4.8 ppm (lower panel) with different concentrations and pH values; (B) calibration plot using all tubes in the phantom (upper panel) and pH map after ratiometric calibration (lower panel); (C) experimental versus calculated pH. pH measurements were made with a precision of ±0.1 unit.

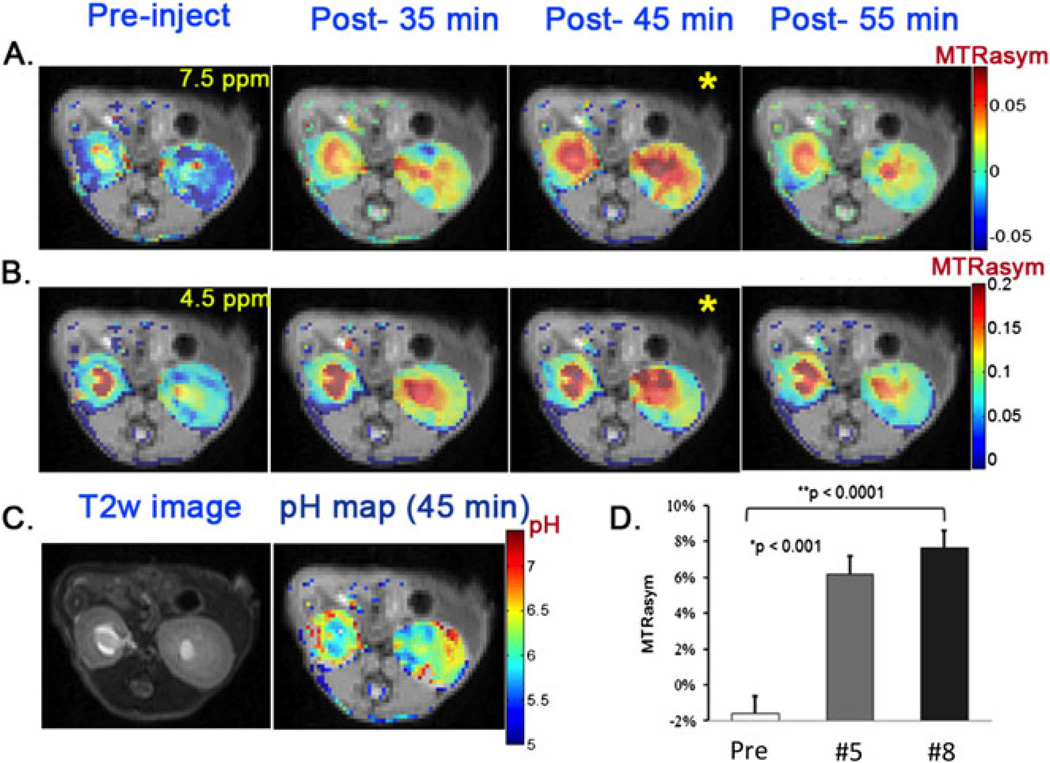

Next, we evaluated whether 5 or 8 could be detected after administration into live animals through injecting 100 µL of a 0.25 M solution of each into three mice and collecting CEST images. Images consisting of a single axial slice containing both kidneys were chosen (Fig. 6). We used a 12-point collection scheme (±4.2, 4.5, 4.8, 7.2, 7.5 and 7.8 ppm) to minimize experimental error and increase reproducibility, using ω1 = 5.9 µT to reduce the sensitivity to B0 inhomogeneity. The CEST signal at 7.5 ppm increased in both the calyx and cortex and reached a maximum at about 45 min post-injection (Fig. 6A, B), which indicated maximal probe uptake. The average CEST contrast was 7.6 ± 1.0% and 6.2 ± 1.0% over the whole kidney for compounds 5 and 8, respectively (Fig. 6D). Based on 5 (a) displaying a larger increase in ratio (MTRasym) as a function of pH than 8, and (b) producing stronger CEST contrast in the kidneys after tail vein administration, it was selected for pH mapping. At the peak CEST contrast time point (45 min), the ratiometric method was applied to obtain a pH image and is shown in Fig. 6C. The average pH for the whole kidney was about 6.5 ± 0.1 (N = 3), which is consistent with the pH ~ 6.6–6.7 reported previously (54,62).

Figure 6.

In vivo kidney images and pH maps. Experimental conditions: tsat = 3 s, ω1 = 5.9 µT. (A) 7.5 ppm CEST contrast maps at pre-, post-35 min, post-45 min and post-55 min injection of compound 5; (B) 4.5 ppm CEST contrast maps for the same times as in A; (C) T2w image and pH map using compound 5 for the same mouse; (D) average contrast over the whole kidney for pre- and post-45 min injection of compounds 5 and 8.

At this point, a number of diaCEST imaging probes have been developed that appear to be quite promising for pH mapping, including iodinated agents such as iopamidol, iobitridol, iopromide and our new I45DC compounds. One of the advantages of our I45DC scaffold is that the chemical shifts are the largest of all probes developed to date, which is an important factor to consider for studies on 3 T scanners, although on high field preclinical scanners the contrast produced was quite similar to that produced by iopamidol (3). Another advantage of the I45DC probes is the ease of modification through the schemes presented in this article, allowing adjustment of the exchange properties and biodistribution for a particular medical application. On the other hand, while some toxicity data for I45DC compounds are available in the literature, with the LD50 reported at 200–350 mg/kg in rodents (63–65), a clear advantage of the aforementioned iodinated CEST agents is their prior approval for administration to patients at high concentrations, which has allowed pilot studies of pH imaging technology in patients (62). Another disadvantage of the current group of I45DCs is that, with the largest chemical shift around 7.8 ppm, the kex values (~4000/s) are still not ideal for 3 T scanners (57). Based on these considerations, we believe the I45DC agents represent a strong new alternative to the existing iodinated pH imaging probes.

3. CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that imidazole N–H protons can be tuned for CEST imaging through appropriate ring substitution. In particular I45DCs 5, 8 and 9 had imidazole N–H protons that resonated at 7.8 ppm from water, which produced significant contrast. Their CEST properties were systematically studied, with the contrast response to pH found to be significantly different upon attachment of lysine, suggesting their viability as pH sensors. Compound 5 was injected into mice and the pH of the kidneys was accurately measured.

4. EXPERIMENTAL

4.1. General for the tested compounds

Imidazole-5-carboxylic acid, imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid, 1,2,3-triazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid and pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). H-Glu(Ot-Bu)Ot-Bu HCl, H-Asp(Ot-Bu)Ot-Bu HCl and H-Lys(N-Boc) Ot-Bu were purchased from Chem-Impex (Wood Dale, IL, USA). Solvents used for chromatography were ACS or HPLC grade, as appropriate. Reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) and by 1H NMR. EM Science 60 F silica gel plates were used for TLC analyses. Flash column chromatography was performed over ICN EcoChrom silica gel (32–63 mm). HPLC purifications were performed using 18C columns (19 mm × 250 mm, Waters Atlantis) at 10 mL/min flow rate of water–acetonitrile eluent, unless specified otherwise. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz spectrometer. The chemical shifts are reported as δ values (ppm) relative to the water signal in D2O. High-resolution mass spectral analyses were performed using the electrospray ionization (ESI) method.

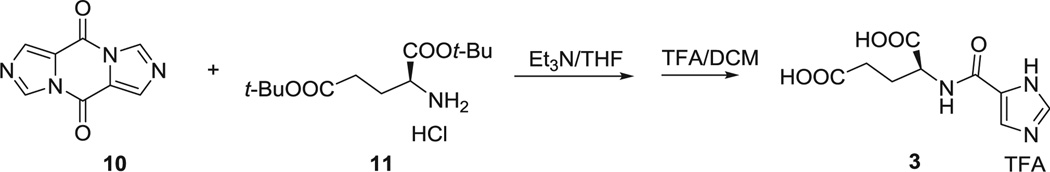

4.2. Synthesis of (S)-2-(1H-imidazole-5-carboxamido)pentanedioic acid (3)

Diimidazo[1,5-a]piperazine-5,10-dione (10) (66) 376 mg (2 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL dry THF. H-Glu(Ot-Bu)Ot-Bu HCl (11) 1.2 g (4 mmol) and triethyl amine 3 mL (20 mmol) were added to the solution at 0 °C and the reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. After the solvent was removed under vacuum, the tert-butyl protected intermediate was obtained by flash column chromatography. Then, this intermediate was dissolved in 5 mL TFA/DCM (1/1) for 2 h at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, compound 3 was purified by HPLC as a white powder, 310 mg, yield 23%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 8.69 (s, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 4.47 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.38 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 2.20–2.11 (m, 1H), 2.01–1.94 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 177.0, 174.6, 162.8 (q, TFA), 158.7, 135.5, 126.6, 120.7, 116.4 (q, TFA), 52.4, 29.8, 25.6. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + H+) C9H12N3O5+: 242.0771; found 242.0781.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 8/92, 10 mL/min): 9.5 min.

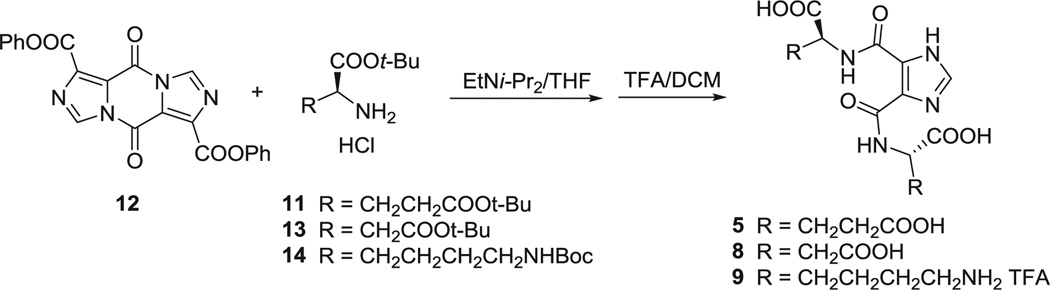

4.3. Synthesis of imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides (5, 8, 9)

5,10-Dioxo-5H,10H-diimidazo[1,5-a:1′-5′-d]pyrazine-1,6-dicarboxylic acid diphenyl ester (12) (67), 214 mg (0.5 mmol) and 5 mL THF were added to a dry flask. To this suspension at 0 °C was added the protected amino acids (11, 13 or 14; 1 mmol) and EtNi-Pr2 2 mL (11 mmol). After stirring at room temperature for 2 h, the reaction was refluxed for 2–4 days, monitored by TLC. After the solvent was removed under vacuum, the tert-butyl protected intermediate was obtained by flash column chromatography. Then, this intermediate was dissolved in 5 mL TFA/DCM (1/1) for 2 h at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, compound 5, 8 or 9 was purified by HPLC.

5 yield 66% white powder.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 7.89 (s, 1H), 4.57 (dd, J1 = 6.6 Hz, J2 = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 2.45 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4H), 2.25–2.22 (m, 2H), 2.09–2.05 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 176.9, 174.5, 161.4, 136.9, 129.8, 52.1, 29.9, 26.0. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + Na+) C15H18N4NaO10+: 437.0915, found 437.0916.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 15/85, 6 mL/min): 15.0 min.

8 yield 58% white powder.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 7.84 (s, 1H), 4.87 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, 2H), 3.05–2.91 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 174.3, 173.8, 161.2, 136.9, 129.8, 49.0, 35.6. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + Na+) C13H14N4NaO10+: 409.0602, found 409.0585.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 15/85, 10 mL/min): 9.4 min.

9 yield 62% white powder.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 8.01 (s, 1H), 4.43 (dd, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 3.9 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4H), 1.91–1.77 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.56 (m, 4H), 1.42–1.34 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 174.9, 162.7 (q, TFA), 160.7, 136.5, 129.1, 116.1 (q, TFA), 54.3, 52.9, 39.1, 30.0, 26.2, 21.9. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + H+) C17H29N6O6+: 413.2143, found 413.2130.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 8/92, 10 mL/min): 15 min.

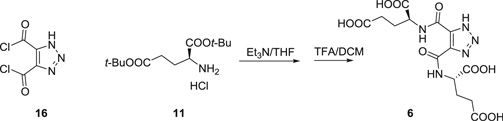

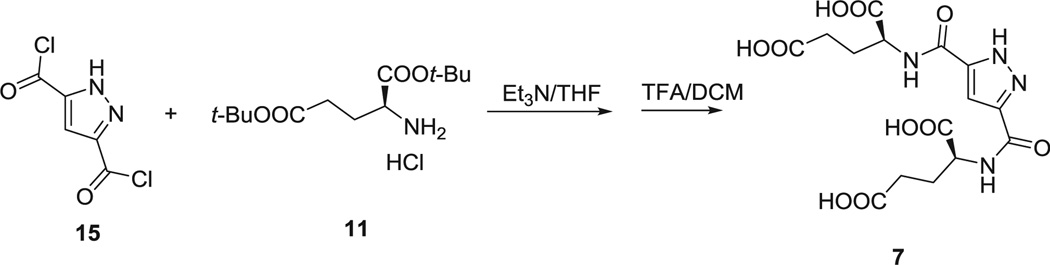

4.4. Synthesis of 6

1H-1,2,3-Triazole-4,5-dicarbonyl dichloride (16) was prepared using the same procedure as for 15 (67). 16 326 mg (1.7 mmol) and THF 10 mL were added to a dry flask. To this suspension at 0 °C was added H-Glu(Ot-Bu)Ot-Bu HCl (11) 1.0 g (3.4 mmol) and triethyl amine 3 mL (20 mmol). The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, the tert-butyl protected intermediate was obtained by flash column chromatography. Then, this intermediate was dissolved in 5 mL TFA/DCM (1/1) for 2 h at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, Compound 6 was purified by HPLC as a light yellow powder, 300 mg, yield 43%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.54 (dd, J1 = 6.3 Hz, J2 = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4H), 2.22–2.14 (m, 2H), 2.05–1.98 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 176.9, 174.2, 160.4, 137.1, 52.1, 29.8, 25.8. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + Na+) C15H18N4NaO10+: 437.0915, found 437.0921.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 15/85, 10 mL/min): 12.5 min.

4.5. Synthesis of 7

1H-Pyrazole-3,5-dicarbonyl dichloride (15) (68) 384 mg (2 mmol) and THF 10 mL were added to a dry flask. To this suspension at 0 °C was added H-Glu(Ot-Bu)Ot-Bu HCl (11) 1.2 g (4 mmol) and triethyl amine 3 mL (20 mmol). The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, the tert-butyl protected intermediate was obtained by flash column chromatography. Then, this intermediate was dissolved in 5 mL TFA/DCM(1/1) for 2 h at room temperature. After all of the solvent was removed under vacuum, Compound 7 was purified by HPLC as a white powder, 280 mg, yield 34%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 7.09 (s, 1H), 4.45 (dd, J1 = 6.9 Hz, J2 = 3.9 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.92 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ 176.9, 174.6, 161.8, 141.6, 106.3, 52.0, 30.0, 25.6. MS: HR-ESI calculated for (M + Na+) C14H17N5NaO10+: 438.0868, found 438.0873.

HPLC (Waters Atlantis, MeCN/H2O 15/85, 10 mL/min): 10.5 min.

4.6. Phantom solutions

Samples were dissolved in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at the desired concentrations and titrated using high concentration HCl/NaOH to the pH values listed. The solutions were then placed in 1 mm glass capillaries and assembled in a holder for CEST MR imaging. The samples were kept at 37 °C during imaging. Phantom CEST experiments were performed on a Bruker 11.7T vertical MR scanner, using a 20 mm birdcage transmit–receive coil. The CEST images were acquired using a RARE (RARE = 8) sequence with a CW saturation pulse length of 3 s and saturation field strengths (B1) from 1.2 µT to 14.4 µT. The CEST Z spectra were acquired by incrementing the saturation frequency every 0.3 ppm from −15 to 15 ppm for phantoms; TR = 6 s, effective TE = 17 ms, matrix size = 64 × 48 and slice thickness of 1.2 mm.

4.7. Animal imaging

All experiments conducted with mice were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). BALB/c mice weighing 20–25 g (Charles River Laboratories) were maintained under specific pathogen free conditions in the Johns Hopkins University animal facility. During MRI acquisition, the mice were anesthetized using 0.5–2% isoflurane and placed in a 23 mm transmit–receive mouse coil. Their breath rate was monitored throughout the in vivo MRI experiments using a respiratory probe. To minimize motion artifacts, we selected a 1.5 mm thick slice in the middle of the calyx and kept the respiratory rate constant at about 30 breaths/min. A 100 µL volume of a 0.25 M I45DC solution in PBS (pH 7.3) was slowly injected via a catheter into the tail vein. In vivo images were acquired on a Bruker BioSpec 11.7 T horizontal MR scanner, with one axial slice 1.5 mm thick crossing both renal centres chosen for the CEST measurements. CEST images with saturation frequencies of (±7.2 ppm, ±7.5 ppm, ±7.8 ppm) and (±4.2 ppm, ±4.5 ppm, ±4.8 ppm) were acquired repeatedly every 10 min both pre- and post-injection. Another set of saturation weighted images with frequency incrementing every 0.1 ppm from −1 to 1 ppm, termed the water saturation shift reference (WASSR) (69), were collected for B0 mapping as the first pre-injection and the final post-injection set of images, using a 0.5 s saturation pulse with B1 = 0.5 µT, and TR/effective TE = 2 s/15 ms. Image parameters were similar to those for the phantom except for TR/effective TE = 5 s/15 ms, and setting B1 = 5.9 µT. CEST contrast was quantified as in phantoms.

4.8. Post-processing

All post-processing was performed using in-house written MATLAB scripts. CEST contrast was quantified in the images using

| (1) |

With this metric based on the subtraction of the two water signal intensities with saturation pulses at frequencies of +Δω and −Δω with respect to water, i.e. S(+Δω) and S(−Δω), a voxel-by-voxel B0 map was generated as described previously (69) using WASSR images for phantoms and live animals. As is shown for a representative mouse in the supporting information (Fig. S1), −75 Hz < B0 < +75 Hz for the kidneys, which is much smaller than the magnitude of the saturation pulse strength (ω1 = 5.9 µT). Because of this, B0 correction was not necessary to perform in vivo. Instead, average maps of MTRasym using the 12 offsets were calculated. All images were masked due to visceral movements present in regions outside the kidney; however, representative unmasked images are displayed in the supporting information (Fig. S2).

4.9. pH calibration using phantoms and in vivo pH map generation

The pH calibration scheme was developed based on examining the data for 5 at three different concentrations (6.25 mM, 25 mM and 50 mM), with each concentration containing four or five samples with pH varied from 5.7 to 7.4. For all the 14 samples of each agent, the ratio between the average MTRasym value of (±7.2 ppm, ±7.5 ppm, ±7.8 ppm) and that of (±4.2 ppm, ±4.5 ppm, ±4.8 ppm) (B1 = 5.9 µT) was plotted as a function of measured pH, with the correlation function of pH = ratio × 1.04 + 5.21. Based on the ratio and pH correlation function from the phantoms, the in vivo dynamic pH maps of the kidneys were generated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH R01 EB015031, CA134675, CA197470, R21 EB020905 and S10RR025118.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malagrino PA, Venturini G, Yogi PS, Dariolli R, Padilha K, Kiers B, Gois TC, da Motta-Leal-Filho JM, Takimura CK, Girardi ACC, Carnevale FC, Zeri ACM, Malheiros DMAC, Krieger JE, Pereira AC. Catheter-based induction of renal ischemia/reperfusion in swine: description of an experimental model. Physiol Rep. 2014;2(9e12150) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siesjo BK. Pathophysiology and treatment of focal cerebral-ischemia 1. Pathophysiology. J Neurosurg. 1992;77(2):169–184. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo DL, Busato A, Lanzardo S, Antico F, Aime S. Imaging the pH evolution of an acute kidney injury model by means of iopamidol, a MRI-CEST pH-responsive contrast agent. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(3):859–864. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies RJ, Raghunand N, Garcia-Martin ML, Gatenby RA. pH imaging. A review of pH measurement methods and applications in cancers. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2004;23(5):57–64. doi: 10.1109/memb.2004.1360409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies RJ, Liu Z, Bhujwalla Z. 31P-MRS measurements of extracellular pH of tumors using 3-aminopropylphosphonate. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(1 Pt 1):C195–C203. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.1.C195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhujwalla ZM, Artemov D, Ballesteros P, Cerdan S, Gillies RJ, Solaiyappan M. Combined vascular and extracellular pH imaging of solid tumors. NMR Biomed. 2002;15(2):114–119. doi: 10.1002/nbm.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Sluis R, Bhujwalla ZM, Raghunand N, Ballesteros P, Alvarez J, Cerdan S, Galons JP, Gillies RJ. In vivo imaging of extracellular pH using 1H MRSI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(4):743–750. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<743::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Provent P, Benito M, Hiba B, Farion R, Lopez-Larrubia P, Ballesteros P, Remy C, Segebarth C, Cerdan S, Coles JA, Garcia-Martin ML. Serial in vivo spectroscopic nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of lactate and extracellular pH in rat gliomas shows redistribution of protons away from sites of glycolysis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(16):7638–7645. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabenstein DL, Isab AA. Determination of the intracellular pH of intact erythrocytes by H-1-NMR spectroscopy. Anal Biochem. 1982;121(2):423–432. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gil MS, Cruz F, Cerdan S, Ballesteros P. Imidazol-1-ylalkanoate esters and their corresponding acids – a novel series of extrinsic H-1 NMR probes for intracellular pH. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1992;2(12):1717–1722. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Martin ML, Herigault G, Remy C, Farion R, Ballesteros P, Coles JA, Cerdan S, Ziegler A. Mapping extracellular pH in rat brain gliomas in vivo by H-1 magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging: comparison with maps of metabolites. Cancer Res. 2001;61(17):6524–6531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Wu K, Sherry AD. A novel pH-sensitive MRI contrast agent. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38(21):3192–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghunand N, Zhang S, Sherry AD, Gillies RJ. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of tissue pH using a novel pH-sensitive contrast agent, GdDOTA-4AmP. Acad Radiol. 2002;9(Suppl 2):S481–S483. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghunand N, Howison C, Sherry AD, Zhang S, Gillies RJ. Renal and systemic pH imaging by contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(2):249–257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe MP, Parker D, Reany O, Aime S, Botta M, Castellano G, Gianolio E, Pagliarin R. pH-dependent modulation of relaxivity and luminescence in macrocyclic gadolinium and europium complexes based on reversible intramolecular sulfonamide ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(31):7601–7609. doi: 10.1021/ja0103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Martin ML, Martinez GV, Raghunand N, Sherry AD, Zhang SR, Gillies RJ. High resolution pH(e) imaging of rat glioma using pH-dependent relaxivity. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(2):309–315. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, in’t Zandt R, Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Golman K, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate. Nature. 2008;453(7197):940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature07017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143(1):79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancu I, Dixon WT, Woods M, Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. CEST and PARACEST MR contrast agents. Acta Radiol. 2010;51(8):910–923. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.502126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu G, Song X, Chan KWY, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(7):810–828. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terreno E, Castelli DD, Aime S. Encoding the frequency dependence in MRI contrast media: the emerging class of CEST agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2010;5(2):78–98. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(4):927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aime S, Carrera C, Castelli DD, Crich SG, Terreno E. Tunable imaging of cells labeled with MRI-PARACEST agents. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44(12):1813–1815. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, DeLiso MA, Berman SDC, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM. New ‘multicolor’ polypeptide diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (DIACEST) contrast agents for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(4):803–812. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu GS, Moake M, Har-el YE, Long CM, Chan KWY, Cardona A, Jamil M, Walczak P, Gilad AA, Sgouros G, van Zijl PCM, Bulte JWM, McMahon MT. In vivo multicolor molecular MR imaging using diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer liposomes. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(4):1106–1113. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aime S, Delli Castelli D, Terreno E. Novel pH-reporter MRI contrast agents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(22):4334–4336. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4334::AID-ANIE4334>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aime S, Barge A, Delli Castelli D, Fedeli F, Mortillaro A, Nielsen FU, Terreno E. Paramagnetic lanthanide(III) complexes as pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents for MRI applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(4):639–648. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu YK, Soesbe TC, Kiefer GE, Zhao PY, Sherry AD. A responsive europium(III) chelate that provides a direct readout of pH by MRI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(40):14002–14003. doi: 10.1021/ja106018n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delli Castelli D, Terreno E, Aime S. Yb-III-HPDO3A: a dual pH- and temperature-responsive CEST agent. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(8):1798–1800. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheth VR, Li YG, Chen LQ, Howison CM, Flask CA, Pagel MD. Measuring in vivo tumor pHe with CEST-FISP MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):760–768. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McVicar N, Li AX, Suchy M, Hudson RHE, Menon RS, Bartha R. Simultaneous in vivo pH and temperature mapping using a PARACEST-MRI contrast agent. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(4):1016–1025. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castelli DD, Ferrauto G, Cutrin JC, Terreno E, Aime S. In vivo maps of extracellular pH in murine melanoma by CEST–MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):326–332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(5):799–802. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<799::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PC. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med. 2003;9(8):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aime S, Calabi L, Biondi L, De Miranda M, Ghelli S, Paleari L, Rebaudengo C, Terreno E. Iopamidol: exploring the potential use of a well-established X-ray contrast agent for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(4):830–834. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (QUEST and QUESP): pH calibration for poly-L-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(4):836–847. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan KWY, Liu G, Song X, Kim H, Yu T, Arifin DR, Gilad AA, Hanes J, Walczak P, van Zijl PCM, Bulte JWM, McMahon MT. MRI-detectable pH nanosensors incorporated into hydrogels for in vivo sensing of transplanted-cell viability. Nat Mater. 2013;12(3):268–275. doi: 10.1038/nmat3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun PZ, Benner T, Kumar A, Sorensen AG. Investigation of optimizing and translating pH-sensitive pulsed-chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging to a 3 T clinical scanner. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(4):834–841. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang SR, Zhou KJ, Huang G, Takahashi M, Sherry AD, Gao JM. A novel class of polymeric pH-responsive MRI CEST agents. Chem Commun. 2013;49(57):6418–6420. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42452a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen LQ, Howison CM, Jeffery JJ, Robey IF, Kuo PH, Pagel MD. Evaluations of extracellular pH within in vivo tumors using acidoCEST MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(5):1408–1417. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu RH, Longo DL, Aime S, Sun PZ. Quantitative description of radiofrequency (RF) power-based ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) pH imaging. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(5):555–565. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan KW, McMahon MT, Kato Y, Liu G, Bulte JW, Bhujwalla ZM, Artemov D, van Zijl PC. Natural D-glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(6):1764–1773. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker-Samuel S, Ramasawmy R, Torrealdea F, Rega M, Rajkumar V, Johnson SP, Richardson S, Goncalves M, Parkes HG, Arstad E, Thomas DL, Pedley RB, Lythgoe MF, Golay X. In vivo imaging of glucose uptake and metabolism in tumors. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):1067–1072. doi: 10.1038/nm.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kogan F, Singh A, Debrosse C, Haris M, Cai K, Nanga RP, Elliott M, Hariharan H, Reddy R. Imaging of glutamate in the spinal cord using GluCEST. Neuroimage. 2013;77:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kogan F, Haris M, Singh A, Cai K, Debrosse C, Nanga RP, Hariharan H, Reddy R. Method for high-resolution imaging of creatine in vivo using chemical exchange saturation transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):164–172. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song X, Airan RD, Arifin DR, Bar-Shir A, Kadayakkara DK, Liu G, Gilad AA, van Zijl PC, McMahon MT, Bulte JW. Label-free in vivo molecular imaging of underglycosylated mucin-1 expression in tumour cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6719. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snoussi K, Bulte JWM, Gueron M, van Zijl PCM. Sensitive CEST agents based on nucleic acid imino proton exchange: detection of poly(rU) and of a dendrimer-poly(rU) model for nucleic acid delivery and pharmacology. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(6):998–1005. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bar-Shir A, Liu GS, Liang YJ, Yadav NN, McMahon MT, Walczak P, Nimmagadda S, Pomper MG, Tallman KA, Greenberg MM, van Zijl PCM, Bulte JWM, Gilad AA. Transforming thymidine into a magnetic resonance imaging probe for monitoring gene expression. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(4):1617–1624. doi: 10.1021/ja312353e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu GS, Liang YJ, Bar-Shir A, Chan KWY, Galpoththawela CS, Bernard SM, Tse T, Yadav NN, Walczak P, McMahon MT, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM, Gilad AA. Monitoring enzyme activity using a diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(41):16326–16329. doi: 10.1021/ja204701x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilad AA, McMahon MT, Walczak P, Winnard PT, Jr, Raman V, van Laarhoven HW, Skoglund CM, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC. Artificial reporter gene providing MRI contrast based on proton exchange. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(2):217–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan KWY, Yu T, Qiao Y, Liu Q, Yang M, Patel H, Liu GS, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM, Hanes J, Zhou SB, McMahon MT. A diaCEST MRI approach for monitoring liposomal accumulation in tumors. J Control Release. 2014;180:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Longo DL, Dastru W, Digilio G, Keupp J, Langereis S, Lanzardo S, Prestigio S, Steinbach O, Terreno E, Uggeri F, Aime S. Iopamidol as a responsive MRI-chemical exchange saturation transfer contrast agent for pH mapping of kidneys: in vivo studies in mice at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(1):202–211. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang X, Song XL, Li YG, Liu GS, Banerjee SR, Pomper MG, McMahon MT. Salicylic acid and analogues as diaCEST MRI contrast agents with highly shifted exchangeable proton frequencies. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(31):8116–8119. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song X, Yang X, Ray Banerjee S, Pomper MG, McMahon MT. Anthranilic acid analogues as diamagnetic CEST (diaCEST) MRI contrast agents that feature an IntraMolecular-bond Shifted HYdrogen (IM-SHY) Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015;10(1):74–80. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang X, Yadav NN, Song X, Banerjee SR, Edelman H, Minn I, van Zijl PCM, Pomper MG, McMahon MT. Tuning phenols with Intra- Molecular bond Shifted HYdrogens (IM-SHY) as diaCEST MRI contrast agents. Chem Eur J. 2014;20(48):15824–15832. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lauzon CB, van Zijl P, Stivers JT. Using the water signal to detect invisible exchanging protons in the catalytic triad of a serine protease. J Biomol NMR. 2011;50(4):299–314. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9527-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bachovchin WW. Contributions of NMR spectroscopy to the study of hydrogen bonds in serine protease active sites. Magn Reson Chem. 2001;39:S199–S213. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rush JR, Sandstrom SL, Yang JQ, Davis R, Prakash O, Baures PW. Intramolecular hydrogen bond strength and pKa determination of N,N′-disubstituted imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides. Org Lett. 2005;7(1):135–138. doi: 10.1021/ol047812a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baures PW, Rush JR, Wiznycia AV, Desper J, Helfrich BA, Beatty AM. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding and intermolecular dimerization in the crystal structures of imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid derivatives. Cryst Growth Des. 2002;2(6):653–664. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muller-Lutz A, Khalil N, Schmitt B, Jellus V, Pentang G, Oeltzschner G, Antoch G, Lanzman RS, Wittsack HJ. Pilot study of iopamidol-based quantitative pH imaging on a clinical 3T MR scanner. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med. 2014;27(6):477–485. doi: 10.1007/s10334-014-0433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiricheck LT. Pharmacological activity and toxicity of neurotropic agents in experimental hypodynamia. Farmakol Toksikol. 1979;42(3):221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aleksandrova IY, Tkachenko EI, Sapronov NS, Sholtes L, Trnovets T, Plotrovskii LB. Structure, synthesis, and pharmacological activity of a metabolite of etimizole. Pharm Chem J. 1986;20(2):99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kniga M. Central action of imdazolecarboxylic acid derivatives. Farmakol Toksikol. 1959;22:11. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moarbess G, Deleuze-Masquefa C, Bonnard V, Gayraud-Paniagua S, Vidal JR, Bressolle F, Pinguet F, Bonnet PA. In vitro and in vivo antitumoral activities of imidazo[1,2-a]quinoxaline, imidazo[1,5-a] quinoxaline, and pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(13):6601–6610. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiznycia AV, Baures PW. An improved method for the synthesis of dissymmetric N,N′-disubstituted imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamides. J Org Chem. 2002;67(20):7151–7154. doi: 10.1021/jo025536c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eisenwiener A, Neuburger M, Kaden TA. Cu2+ and Pt2+ complexes of pyrazole and triazole based dinucleating ligands. Dalton Trans. 2007;2:218–233. doi: 10.1039/b612948j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.