Abstract

The genome and structural organization of a novel insect-specific orthomyxovirus, designated Sinu virus, is described. Sinu virus (SINUV) was isolated in cultures of C6/36 cells from a pool of mosquitoes collected in northwestern Colombia. The virus has six negative-sense ssRNA segments. Genetic analysis of each segment demonstrated the presence of six distinct ORFs encoding the following genes: PB2 (Segment 1), PB1, (Segment 2), PA protein (Segment 3), envelope GP gene (Segment 4), the NP (Segment 5), and M-like gene (Segment 6). Phylogenetically, SINUV appears to be most closed related to viruses in the genus Thogotovirus.

Keywords: Sinu virus, Orthomyxoviridae, Thogotovirus genus, Insect-specific viruses

INTRODUCTION

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) are viruses infecting vertebrates that are biologically transmitted by hematophagous arthropods in an alternative vertebrate-arthropod cycle (Bolling et al., 2015). Arboviruses replicate in both their vertebrate and arthropod hosts; and some are capable of causing major diseases outbreaks, such as dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, Rift Valley fever and bluetongue, affecting both human and domestic animal populations.

During the past two decades with the advent of sequencing and metagenomics, a second group of viruses has been discovered in hematophagous insects that are now generally refered to as “insect-specific viruses” (ISVs) (Bolling et al. 2015, Blitvich and Firth, 2015, Junglen and Drosten, 2013). Although many of the ISVs are genetically related to some of the important vertebrate pathogenic arboviruses, they differ biologically from the true arboviruses by their inability to infect vertebrates or to replicate in vertebrate cells (Bolling et al. 2015). They are host-restricted to replication in invertebrate cells.

To date, most of known ISVs have been associated with blood-feeding Diptera (mosquitoes, sandflies and midges) and relatively few have been described in Acari or other types of hematophagous arthropods (Bolling et al. 2015, Blitvich and Firth, 2015).

The purpose of this report is to describe and characterize a novel ISV orthomyxovirus, designated Sinu virus, that was isolated in C6/36 mosquito cells from a pool of adult mosquitoes collected in Cordoba Department on the Caribbean Coast of Colombia in 2013. SINUV appears to be most closely related phylogenetically to the tick-borne viruses in the genus Thogotovirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The study site was located in the municipality of San Bernardo del Viento (9° 21′ 30.97″ N, 75° 58′ 37.28″W), Cordoba department, in northern Colombia on the Caribbean Coast. The area encompasses about 321 Km2 (Figure 1) and is classified as lowland dry tropical forest with high mean annual temperature (29°C) and relative humidity of 80%. The region has two contrasting seasons: a dry season from December to April and a rainy season from May until November (Climate-Data.org 2016 http://en.climate-data.org/location/50073/). Most of the territory is composed of plateau areas, with approximately 34.2 km of beaches, which are used for ecotourism (Acosta 2013, Rojas et al., 2010). The natural vegetation varies from intervened dry forests to flooded lands, including mangrove swamps and estuaries with halophytic vegetation (CVS, 2004, Serrano 2004).

Fig. 1. Location of Sinu virus isolation.

A red dot indicates the location of the mosquito sampling site in the San Bernado del Viento municipality.

Mosquito collections

Mosquitoes from San Bernardo were collected, using CDC-light traps, during arbovirus field studies between 2012 and 2013. After collection, mosquitoes were killed by freezing and transported in liquid nitrogen to the University of Antioquia in Medellín, where they were stored at −70 °C. The mosquitoes pools were subsequently transported on dry ice to the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston for virus assay, following all national and Institutional regulations.

Processing mosquitoes for virus isolation

At UTMB, the mosquitoes were separated into pools of approximately 50 insects that were homogenized in plastic tubes, containing 1.0 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin stock (Sigma), and a 3 mm stainless steel ball, using a TissueLyser (Quiagen). After centrifugation at 10.000 rpm for 10 mins, 100 μL of each mosquito homogenate was inoculated into a single well of a 24-multiwell tissue culture plate (Corning), containing a monolayer of Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells. After absorption for 2 hrs, 1.5mL of maintenance medium was added to each well and the cultures were incubated for 7–8 days at 28°C. Cultures were examined every 2 days for evidence of viral cytopathic effect (CPE). If CPE was observed, 150μL of the culture fluid was removed from the well and inoculated into a 12.5 mL flask culture of C6/36 cells to obtain material for study and further characterization, as described below.

Evaluation of CoB 38d (SINUV) growth in mosquito and vertebrate cells

In order to determine the host range of SINUV, a C6/36 cell stock of CoB 38d was inoculated into 12.5 cm2 flask cultures of the following cell lines, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA.: Aedes albopictus clone C6/36 (CRL-1660); baby hamster kidney BHK-21 (CCL-10); African green monkey kidney Vero E6 (CRL-1586) and chicken embryonic fibroblask cells (CRL-12203). Cells were grown in 5 mL of culture medium, recommended in the ATCC specification sheets. C6/36 cells were incubated at 28°C; Vero, baby hamster and chick embryonic cells were maintained at 37°C. When a confluent monolayer of cells was present in the flasks, 200 uL of stock virus (CoB 38d) was inoculated into each flask. After incubation for 2 hours, the inoculum was aspirated and each flask was washed three times with 5 mL of maintenance medium. After the final wash, 500 uL of the medium was removed as a day 0 sample and was frozen at −80°C for subsequent testing. Cultures were incubated at the temperatures noted above. Each day thereafter, for seven consecutive days, all of the medium was removed by aspiration for testing and 5 mL of fresh medium was added. Total RNA was subsequently extracted from all samples (day 0 to 7), using Trizol (Ambion) reagent and RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), following instructions of the manufacturer. The viral RNA extracted was assessed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay using SINUV-specific primers targeting the PB1 gene (primer sequences and PCR conditions available upon request).

Transmission electron microscopy

For ultrastructural analysis, infected C6/36 cells were fixed for at least 1hr in a mixture of 2.5% formaldehyde prepared from paraformaldehyde powder and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.05M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), to which 0.03% picric acid and 0.03% CaCl2 were added. The monolayers were washed in 0.1M cacodylate buffer, and cells were scraped off and processed further as a pellet. The pellets were postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 1 h, washed with distilled water, and en bloc stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 20 min at 60°C. The pellets were dehydrated in ethanol, processed through propylene oxide, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Ultrathin sections were cut on a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), stained with lead citrate, and examined in a Philips 201 transmission electron microscope at 60 kV.

Titration of SINUV in mosquito cells

A SINUV stock, prepared in the C6/36 cells, was titrated in 24-well culture plates with monolayers of C6/36 cells. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the virus stock were prepared in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Then 100μL of each dilution was inoculated into four microplate wells. After absorption at 28°C for 2 hrs, 1.5 mL of maintenance medium was added to each well. Maintenance medium was minimal essential medium (Gibco), supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 2% MEM non-essential amino acid solution (Sigma), 1% NaHCO3 solution (1.5%) and 1% of a L-glutamine-penicillin-streptomycin 100X solution (Sigma). Microplate cultures were incubated at 28°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Six days post-infection, mosquito cells from each well were spotted onto Cel-Line 12 well glass slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for examination by indirect fluorescent antibody technique (IFAT), as described before (Xiao et al, 2001). A standard IFAT was done, using a mouse hyperimmune polyclonal antibody prepared against Thogoto virus, obtained from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA). The tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) per mL was calculated, using the Reed–Muench method (Reed and Muench, 1938).

RNA extraction, construction of RNA library, sequence assembly and analysis

Viral RNA was extracted from culture fluid of C6/36 cells infected with isolate CoB 38d (SINUV) using Qiamp RNA mini kit (Qiagen) as previously described by (Vasilakis et al., 2014). The genome sequence of CoB 38d was obtained using parallel sequencing and an Illumina TruSeq RNA v2 Kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a highly efficient protocol was made including the rRNA removal (Ribo-Zero technology) followed by a rapid, ligation-free cDNA synthesis procedure for preparing directional RNA-seq libraries (ScriptSeq v2 technology) (Pease 2012). The data generated were assembled using a de novo strategy implemented in the Mira Software (Chevreux et al. 2004). The resulting contigs were visually inspected and sequences were annotated using the Geneious v. 9 and deposited in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of the isolated orthomyxovirus used in this study

| Classification

|

strain ID | Source Isolation | Genbank Accesion N°

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Virus name | Abbreviation | PB2 | PB1 | PA | G | NP | M | ||

| Influenza virus A | Influenza virus A | FLUAV | A/duck/Mongolia/675/2015(H3N8) | Anas platyrhync hos | LC132933 | LC132934 | LC132935 | LC132936 | LC132937 | LC132939 |

| Influenza virus B | Influenza virus B | FLUBV | B/Lee/40 | NI | NC_002205 | NC_002204 | NC_002204 | NC_002207 | NC_002208 | NC_002210 |

| Influenza virus C | Influenza virus C | FLUCV | C/Ann Arbor/1/50 | NI | NC_006307 | NC_006308 | NC_006309 | NC_006310 | NC_006311 | NC_006312 |

| Influenza virus D | Influenza virus D | FLUDV | D/bovine/France/2986/2012 | NI | NC_026953 | NC_026956 | NC_026948 | NC_026952 | NC_026949 | NC_026950 |

| Isavirus | Infectious salmon anemia virus | ISAV | NI | Atlantic salmon | NI | NC_006503 | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Araguari virus | ARAV | BeAn 174214 | Philander opossum | Provided by autor | ||||||

| Cygnet River virus | CyRV | 10-01646 | Cairina moschate (Muscovy duck) | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | JQ693418 | |

| Johnston Atoll virus | JAV | LBJ | Ornithodoros capensis | NI | FJ861697 | NI | FJ861696 | NI | NI | |

| Quaranja virus | Lake Chad virus | LKCV | Ib An 38918 | Plesiotagra vitellinus | NI | FJ861698 | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Quaranfil virus | QRFV | EG T 377 | Argas reflexus | GQ499302 | FJ861695 | GQ499303 | FJ861694 | JN412853 | GQ499304 | |

| Tjuloc virus | TLKV | LEIV 152K | Argas arboreus | JQ928945 | JQ928944 | JQ928943 | JQ928941 | JQ928942 | JQ928946 | |

| Wellfleet Bay virus | WBV | 10-280-G | Somateria mollissima | NC_025795 | NC_025796 | NC_025797 | NC_025798 | NC_025793 | KM114309 | |

| Thogotovirus | Aransas bay virus | ABV | RML65660-8 | Ornithodoros capensis | KC506162 | KC506163 | KC506164 | KC506165 | KC506166 | KC506167 |

| Batken virus | BKNV | LEIV-K306 | Hyalomma marginatum | NI | NI | KJ396673 | KJ396674 | X97340 | KJ396672 | |

| Bourbon virus | BRBV | Original | Human | KU708253 | KU708254 | KP657748 | KU708255 | KP657749 | KP657750 | |

| Dhori virus | DHOV | 1313/61 | Hyalomma dromedarri | GU969308 | GU969313 | GU969309 | GU969310 | GU969311 | GU969312 | |

| Jos virus | JOSV | IBAn-17854 | Bos indicus | HM627174 | HM627170 | HM627175 | FJ861696 | HM627173 | HM627172 | |

| Thogoto virus | THOV | SiAr 126 | Rhiphacephalus bursa | NC_006508 | NC_006495 | NC_006496 | NC_006506 | NC_006507 | NC_006504 | |

| Upulo virus | UPOV | C5581 | Ornithodoros capensis | KC506156 | KC506157 | KC506158 | KC506159 | KC506160 | KC506161 | |

| Unclassified | Sinu virus* | SINU | CoB 38d | Mosquitoes unknown | KX949591 | KX949590 | KX949589 | KX949586 | KX949588 | KX949587 |

NI: No information

Virus sequenced in this study

Genome characterization

The recovered genome for isolate CoB 38d was characterized, based on its genetic traits such as genome size, terminal regions, genome organization, potential Open Reading Frames (ORFs), encoded proteins, potential glycosylation sites, cysteine residues, and conserved motifs, using a set of applications available in the Geneious software v. 9 (Kearse et al., 2012) and the open source NetGlyc v.1.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/).

Genetic Variability

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of orthomyxoviruses closely related to the CoB 38d strain were obtained from the GenBank database (Tables 1 and 2). Regions referred to the ORFs were translated into amino acid sequences, using the Genious software V.9 to determinate the best amino acid substitution model by using the ProtTest v3.4 software (Darriba et al., 2011). Alignments were visually checked and identity calculations were performed, using Geneious software v.9, as well as by the Boxplot analysis implemented in the R package v.1.14.4 (Maechler et al., 2016) and T test as previously described (Williamson et al., 1989).

Table 2.

Details of the orthomyxovirus described based on NGS, used in this study

| Putative Classification

|

Source Isolation | Putative arthropod host | Country of Isolation | Genbank Accesion N° to PB1 sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Virus name | ||||

| Quaranjavirus | Jingshan Fly Virus 1 | True flies | Atherigona orientalis | China | KM817615 |

| Jiujie Fly Virus | Horseflies | Unidentified Tabanidae | China | KM817616 | |

| Sanxia Water Strider Virus 3 | Water striders | Unidentified Gerridae | China | KM817617 | |

| Shayang Spider Virus 3 | Spiders | Neoscona nautica | China | KM817618 | |

| Shuangao Insect Virus 4 | Insect mix 1 | Unidentified Diptera | China | KM817619 | |

| Wuhan Louse Fly Virus 3 | Insect mix 2 | Unidentified Hippoboscoidea | China | KM817620 | |

| Wuhan Louse Fly Virus 4 | Insect mix 2 | Unidentified Hippoboscoidea | China | KM817621 | |

| Wuhan Mosquito Virus 3 | Mosquito Hubei | Culex tritaeniorhynchus | China | KM817622 | |

| Wuhan Mosquito Virus 4 | Mosquito Hubei | Culex tritaeniorhynchus | China | KM817623 | |

| Wuhan Mosquito Virus 5 | Mosquito Hubei | Culex tritaeniorhynchus | China | KM817624 | |

| Wuhan Mosquito Virus 6 | Mosquito Hubei | Culex quinquefasciatus | China | KM817625 | |

| Wuhan Mosquito Virus 7 | Mosquito Hubei | Anopheles sinensi | China | KM817626 | |

| Wuhan Mothfly Virus | Insect mix 4 | Psychoda alternata | China | KM817627 | |

| Thogotovirus | Dielmo orthomyxovirus | Culicoides imicola | Culicoides imicola | Senegal | Provided by autor (Temmand et al., 2016) |

Phylogenetic analysis and signal

Phylogenetic trees of the amino acid alignments were created, using the neighbor-joining method and maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstructions with the RAxML v 8.1.21 hybrid version (Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood) (Pfeiffer and Stamatakis, 2010). A bootstrap analysis was performed using 1,000 replicates (reliability value of 95%) and trees were visualized in the FigTree graphic viewer (Rambaut 2008). In addition, Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed, using Beast v1.8 (Drummond et al., 2012), under the HKY+3+I model, estimating the evolutionary rate using both a strict and an uncorrelated log-normal relaxed clock model.

The phylogenetic signal of each RNA segment was assessed, using the maximum likelihood method (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003). The initial step in this phylogenetic exploration involved the alignment of genomes. This was followed by the reconstruction the phylogenetic signal determined for each 200 nt window, using the bootscanning sliding window approach implemented in the Simplot software. The phylogenetic signal and number of resolved trees for each of the three quartets were estimated in percentage values (Alcantara et al., 2009, Escoto-Delgadillo et al., 2008).

Reassortment analyses of CoB 38d and other orthomyxoviruses

Because viruses with segmented genomes have the potential for reassorment (Gombold and Raming, 1986), nucleotide sequences for each RNA segment of the CoB 38d isolate were used to investigate potential genome reassortment events with other members of the Thogotovirus and Quaranjavirus genera, using the Simplot V. 3.5.1 software (Lole et al., 1999). Nucleotide sequence similarities are represented in percentage values. For each segment, values ranging from 80 to 100% indicate reassortment.

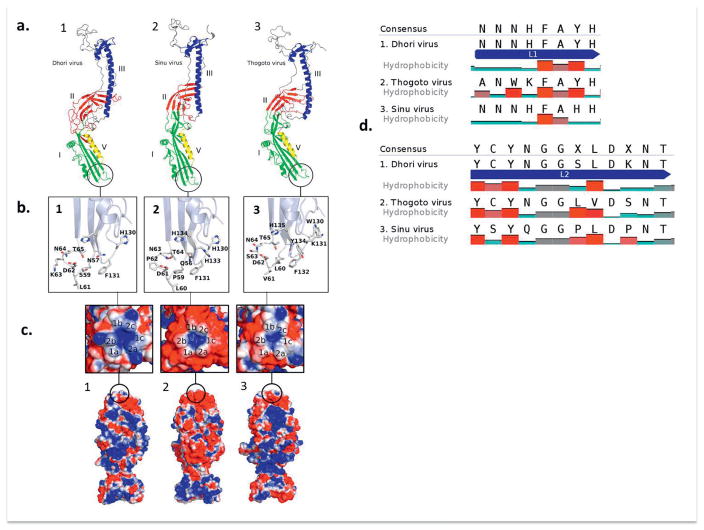

Molecular modeling and electrostactic maps of the CoB 38d GP protein

A BLASTP (Altschul et al., 1990) search against the PDB (Berman et al., 2000) database was used to identity suitable templates. Sequence alignments between target and template amino acid sequences were performed with PROMALS3D (Pei et al., 2008). Structural models were constructed, using Modeller 9v16 (Webb and Sali, 2014). A total of 100 models were constructed for each target. The best model, based on DOPE score (Shen and Sali, 2006), was selected for further evaluation with PRoSA (Wiederstein and Sippl, 2007) and Ramachandran plots generated with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1996). Pymol (http://www.pymol.org) was used to inspect the 3D structure models, calculate structural alignments and to generate electrostatic maps with APBS plugin (Baker et al., 2001). Geneious v9 was used to inspect sequence alignments.

RESULTS

Virus Isolation and in vitro characterization

Virus strain CoB 38d was isolated from a single pool of 50 adult mosquitoes (species not identified) collected in June 2013 in northern Colombia. Based on the locality where the mosquito pool was collected, the virus has been designated Sinu virus (SINUV).

The original homogenate of mosquito pool CoB 38d produced CPE in a culture of C6/36 on the fifth day after inoculation. After passage a second time in C6/36 cells, a filtrate of the culture medium was inoculated into flask cultures of Vero and BHK cells, which were inoculated at 37°C for 14 days. No CPE was observed. A portion (about 10–12 μL) of the second C6/36 culture material was also inoculated intracranially into a litter of newborn mice. No illness or death occurred in the pups after 14 days. Animal work was done at UTMB under an approved IACUC protocol (#9505045).

To determine if SINUV replication occurred in vertebrate cells without producing CPE, additional experiments were carried out in C6/36, Vero, BHK and chick embryonic cell cultures to assay for virus replication by RT-PCR. Samples of medium from the four SINUV-inoculated cell lines were collected from day 0 to day 7, as described in the Methods section. After RNA extraction, a partial region of the PBI gene of SINUV was amplified and run on gels with expected band size between 500 to 550 pb. SINUV RNA extracted from culture fluid from the C6/36 cells from days 0 to 7 post-inoculation (dpi) displayed strong bands on all days (data not shown). In contrast, extracted and amplified viral RNA from the Vero, BHK and chick cells showed decreasing intensity of the RNA bands from day 0 to day 3. On days 4 to 7, no bands were visible, indicating that SINUV did not replicate in the three vertebrate cell lines (data not shown).

Virion morphology

In ultrathin sections of infected C6/36 cells spherical virus particles 130–140 nm in diameter were found free in cytosol. They had an envelope ~7 nm thick covered with a crown of projections ~14 nm long with ~15 nm periodicity (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Ultrastructure of CoB 38d virus in C6/36 cells.

Enveloped spherical virions 130–140 nm in diameter with multiple spikes at the surface are localized free in the cytosol. Bar= 100nm.

Titration of SINUV in mosquito cells

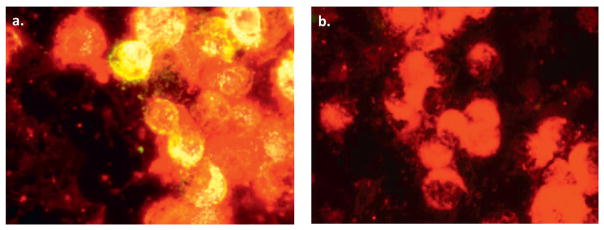

As CoB 38d virus did not cause illness in mice, it was not possible to produce a specific mouse immune ascitic fluid (MIAF) for use in serologic tests. However, in preliminary indirect fluorescent antibody tests (IFAT), it was observed that MIAFs produced against Thogoto virus, and to a lesser extent to Dhori virus (Sbrana et al., 2007), reacted with C6/36 cells infected with CoB 38d (Fig. 3). These observations confirmed the ultrastructural studies, indicating that CoB 38d was an orthomyxovirus, probably related to Thogoto virus. For this reason, a Thogoto virus MIAF, obtained from World Reference Center of Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses, was used in IFATs to determine the growth of CoB 38d in C6/36 cells. The TCID50 of the second passage stock of CoB 38d was calculated as 106 TCID50/mL.

Fig. 3. Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assay.

(a) CoB 38d antigen in infected C6/36 cells, as detected by indirect fluorescent antibody technique (IFAT), using a Thogoto virus hyperimmune mouse ascitic fluid (HMAF). (b) C6/36 cell control (uninfected) stained by IFAT, using the same HMAF.

Genetic characterization of SINUV

The complete CoB 38d virus genome consisted of six RNA segments. The genome of the virus was determined to be 10,833 nucleotides (nt) in length, including the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. The length of the segments ranged from 1009 nt (segment 1) to 2376 nt (Segment 6) (Table 3). Highly conserved terminal sequences for CoB 38d were determined to be: 5′ AGTATTAACAAGAG[A/C/G]TTTC and 3′ AAAAA[T/G/C][C/T] [T/C] CTTTGTTACTACTACC. Each segment encodes for a structural protein with related functional properties as follows:

Table 3.

Genomic characteristic of SINUV based on each genome length, terminal UTR sequences (5′ and 3′), ORFs, and 3′-5′ terminal site conservative

| Seg men t |

Seg men t lent h (nt) |

5′ UT R lent ght (nt) |

5′ terminal site conservative | ORF (nt) | ORF (aa) | 3′ UT R lent ght (nt) |

3′ terminal site conservative | FLUAV/ THOV homolog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 2376 | 31 | AGTATTAACAAGAGATTTC | 2298 (32->2329) | 765 | 47 | AAAAATCTCTTTGTTACTACTACC | PB2 |

| S2 | 2225 | 28 | AGTATTAACAAGAGCTTTA | 2133 (29->2171) | 790 | 54 | AAAAAGCTCTTTGTTACTACTACC | PB1 |

| S3 | 2000 | 59 | AGTATTAACAAGGACTTTA | 1911 (60->1970) | 636 | 30 | AAAAAGTCCTTTGTTACTACTA - - | PA |

| S4 | 1662 | 31 | AGTATTAACAAGAGCTTTA | 1497 (32->1578) | 498 | 84 | AAAAAGCTCTTTGTTACTACT - - - | GP |

| S5 | 1561 | 60 | AGTATTAACAAGAGGT - - - | 1422 (61->1432) | 473 | 79 | AAAAACCTCTTTGTTACTACT - - - | |

| S6 | 1009 | 52 | AGTATTAACAAGAGG - - TC | 816 (53->858) | 271 | 141 | AAAAACCTCTTTGTTACT - - - - - - | M-like |

| Total genome lenght | 10833 |

nt, nucleotides; aa, amino acids.

Boldface indicate a divergence;-, gap

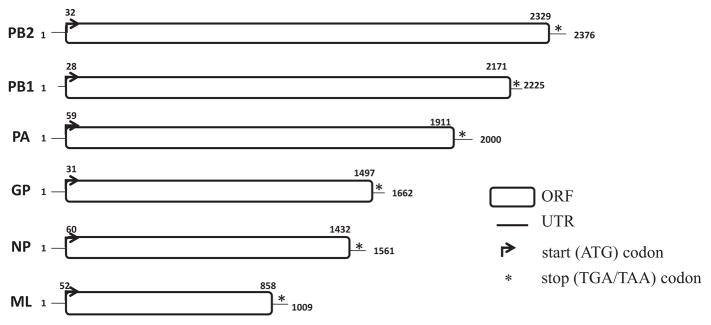

Segments 1 to 3: polymerase proteins (PA, PB1, PB2)

CoB 38d RNA segments 1–3 ranged from 2,376 to 2,000 nt in length, and encode the proteins of a replicative polymerase complex, based on their identity to the influenza virus proteins. The length open reading frame (ORF) of the segment 1 was shown to be 2,298 nucleotides in length, encoding a protein of 765 amino-acid (aa). The largest segment of SINUV shows sequence homology to orthomyxoviral Polymerase basic protein 2 or PB2 gene sequence (Pfam Id PF00604; “Flu_PB2”) (Figure 4, Table 3). T ORF of of SINUV segment 2 is 2,133 nt long (710 aa) and corresponds to orthomyxoviral Polymerase basic protein 1 or PB1 sequence (Pfam Id PF00602; “Flu_PB1” (Table 3). ORF encoded by segment 3 of SINUV is 1,911 nt long and encodes a 636 aa of Flu-PA protein (Polymerase acidic protein or PA) (Pfam Id PF00603; “Flu_PA”) (Figure 4, Table 3).

Fig. 4. Genome structure of the isolate CoB 38d.

The six RNA segments are shown in positive-sense orientation (5′->3′). Numbers indicates the nucleotide positions along the segments. Black line represents the 5′ and 3′ NCRs (Non Coding Regions); rectangular with rounded sides correspond to the ORFs (Open Reading Frames); Black arrows and asterisks represents the start (ATG) and stop (TGA/TAA) codons respectively.

Segment 4: Glycoprotein

ORF of segment 4 is 1,497 nt long and encodes a 498 aa. The putative glycoprotein (GP) of SINUV displayed conservation with the “baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein family” (Pfam Id PF03273; “Baculo_gp64”) (Figure 4, Table 3).

The GP amino acid sequence of SINUV displayed conserved domains, which were identified as domain I (aa position 36–199), II (aa positions 21–35 and 200–267), III (271–345), IV (400–448) and V (408–427). Fusion peptides were determined as YSYQGGPLDPNTGDIE (L2) and NNNHFA (L1). A total of 16 Cys residues and 7 potential NGlyc sites were found over the GP amino acid sequence. Supplementary Figure 1 summarizes the conserved domains, cysteine residues, and potential glycosylation sites for SINUV and other Thogotovirus members.

Segment 5: Nucleoprotein

ORF encoded by segment 5 is 1,422 nt long and encodes a 473 aa. The open reading frame (ORF) encoded by segment 5 of CoB 38d virus is conserved with respect to flu NP-like protein (Pfam Id: SSF161003; “flu NP-like”) (Table 3).

Segment 6: M-like THOV protein

The smallest RNA segment of CoB 38d virus virus encodes a ORF with 816 nt long (271aa). This segment encodes a undescribed protein of unknown function by InterProScan. Analysis using the translated nucleotide-protein Blast X program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) showed low percentage of aa similarity (23%) with the M protein of THOV

Genetic Variability

Amino acid and nucleotidic alignment analysis of individual segments of SINUV were variable and demonstrated a relative similarity with members of the genus Thogotovirus, family Orthomyxoviridae based on PB1, PA, PB2 and GP sequences (Table 4), as follows:

Segment 1 (PB2) of SINUV shares a 26.1% to 29.3% amino acid identity (39.8%–42.7% nt identity) with Dhori virus (DHOV), Bourbon virus (BRBV) and Thogoto virus (THOV). A much higher percentage of identity was displayed in the PB1 segment, which shares 54.8% to 55.3% amino acid identity (55.2%–56.8% nt identity) with THOV and DHOV. The PA segment shares 31.8% to 35.5% amino acid identity (36.2%–36.4% nt identity) with DHOV, BRBV, Batken virus (BKNV) and THOV (Table 4). The GP of SINUV shares 29.3% to 29.8% amino acid identity to DHOV, BRBV and BKNV, as well as with Upolu, Aransas Bay and Jos viruses (Table 4). The NP of CoB 38d shares 32.4% to 43.8% amino acid identity to the NP of Thogotovirus genus (Tables 3 and 4). Segment 6 of CoB 38d shares at a low percentage of amino acid identity (18.8% to 20.7.0%) with the putative matrix (M) of THOV (Tables 3 and 4).

Boxplot analysis

Genetic distances found among members of the genus Thogotovirus were significantly smaller than the values obtained between members other orthomyxovirus genera. The SINUV sequence showed 60% mean genetic variability (p values <0.05, overall p value = 0.0003567) within all genera in the family Orthomyxoviridae (Supplementary Figure 2, supplementary table 1). Interestingly, genetic distances within the genera Quaranjavirus and Thogovirus showed relative high genetic variability with mean values of 50% and 37% respectively, in comparison with other orthomyxoviruses (Supplementary Figure 2, supplementary table 1).

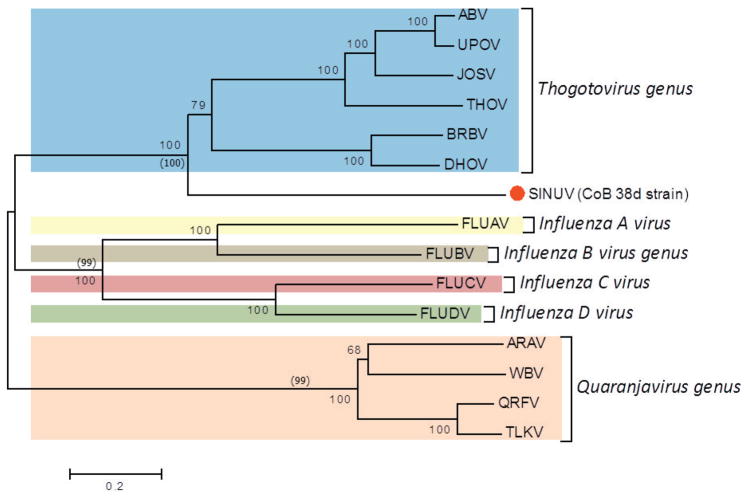

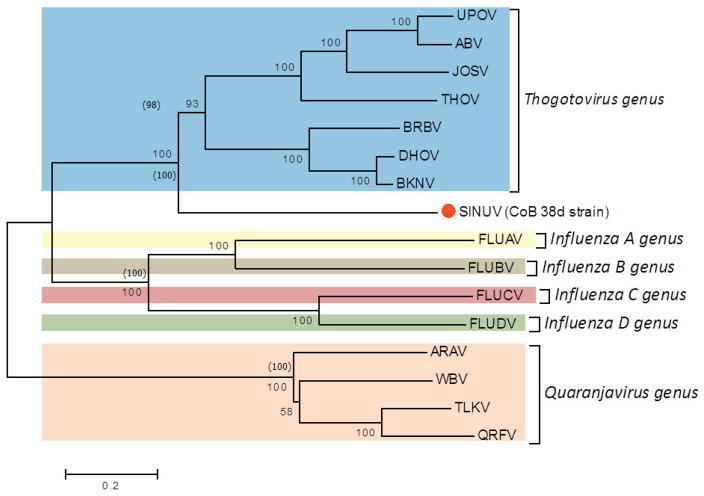

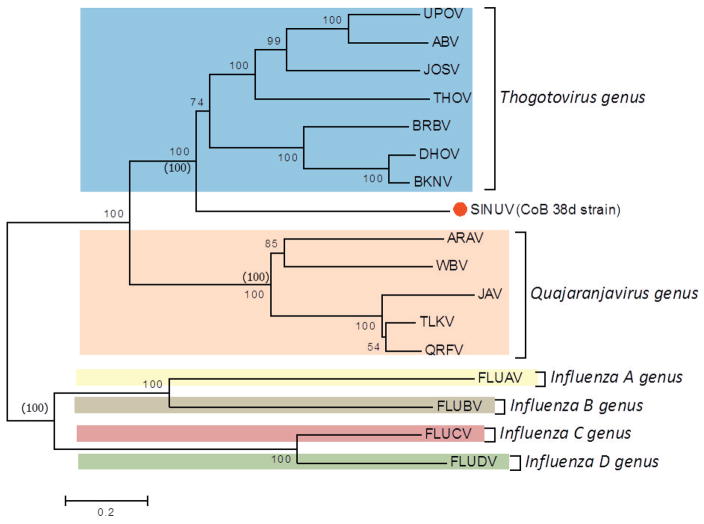

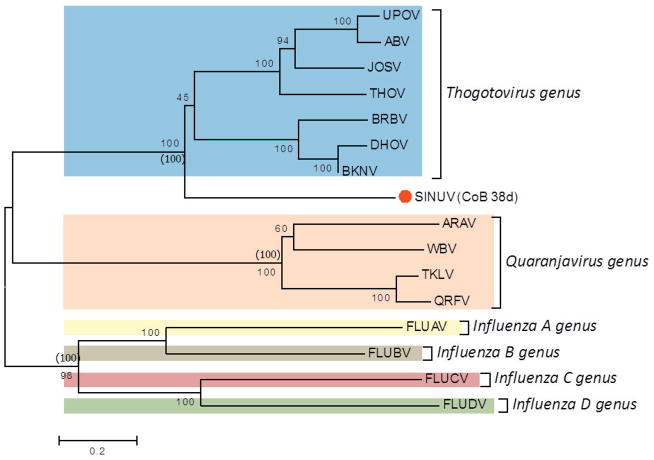

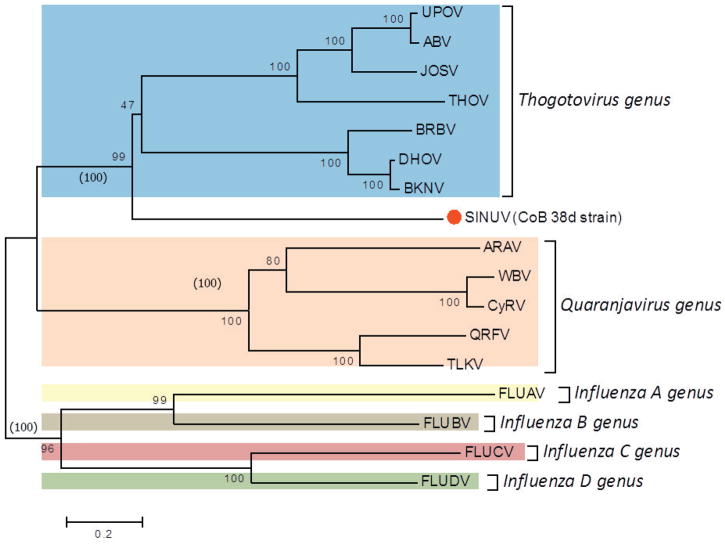

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis, using the protein sequences for all segments (1 to 6) of SINUV in comparison to other orthomyxoviruses, displayed a similar topology. Phylogenetic relationships showed that CoB 38d is a new member of the family Orthomyxoviridae, grouping in a monophyletic cluster distinct from other orthomyxoviruses described previously (Figure 5a–f). Based on the high bootstrap supports (98–100%) in the phylogenetic trees, SINUV clearly clusters with members of the Thogotovirus genus (Figures 5a–f). Importantly, SINUV consistently placed in a basal position to the Thogotovirus genus clade, suggesting that this virus diverged at an earlier time.

Fig. 5. Phylogenetic analysis based on (a) PB2, (b) PB1, (c) PA, (d) GP, (e) NP and (f) M-like proteins based of full length ORFs.

Values over each node of the tree correspond to the bootstrap support values for NJ and values into () correspond to ML. Bayesian posterior probability values are placed within parenthesis. Number over the bars represents the number of amino acid substitutions/site. Scale bar is representing the amino acid substitution/site.

Phylogenetic signals for each RNA segment (in nucleotides) were assessed and determined in overall percentage values in comparison to other members of the family Orthomyxoviridae (Quaranjavirus, Influenzavirus A, Influenzavirus B, Influenzavirus C, Influenzavirus D, and Isavirus genera) with high bootstrap values for NJ (98%) and ML trees (100%). Values of overall percentages under the three quartets and percentages of resolved trees over each genomic segment are summarized in supplementary material (Table S2, Supplementary Figure 3).

Molecular modeling and electrostatic maps of the SINUV GP protein

The stereochemical quality of the generated models presented ~90% of their residues in the most favored regions of the plot. The overall quality of the models was also evaluated using z-scores obtained from ProSA-web server. The calculated z-scores were negative and in the range of −5.02 to −6.84; these value are in agreement with good quality structures and with the z-score found for the template (−5.32) (Table S3, Supplementary Figure 4). The 3D models were also aligned with the selected template. The domains I, III and V were highly conserved in all proteins, with an average R.M.S.D of 0.67 A°, 2.41 A° and 0.21 A°, respectively. On the other hand, domain II was less conserved, with an average R.M.S.D of 6.13 A°. Notably, some of the beta-sheets on the interface of domain II and III became less structured in envDhori (Figure 6A). While domain II of envSinu and envThogoto have two disulfide bridges stabilizing antiparallel beta sheets, envDhori lacks one disulfide bridge, explaining its less ordered structure (Figure 6B). The predicted structures and electrostatic maps of SINU, THOV and DHOV glycoproteins are displayed in Figures 6C and D.

Fig. 6. Three dimensional structure of the glycoprotein (GP).

(a1) DHOV; (a2) isolate CoB 38d and (a3) THOV. (b) Fusion peptide domain in detail for each virus respectively. (c) top and vertical views of the trimmer 3D structures and electrostatic charges (1a,1b,1c,2a,2b,2c) distribution in the structure (red areas=negatively charged; white areas = neutral charge; blue areas = positively charged). (d) Alignment of the fusion peptides of DHOV, THOV and SINUV.

DISCUSSION

Based on its genome sequences and sizes, number of segments, and genetic characteristics (ORFs, and 5′-3′ termini), SINUV is similar to members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. The SINUV genome is characterized by six negative-sense, single-stranded RNA segments with translated functional ORFs. The similar genes, proteins and functions (S1 to S3 related to the polymerase subunits PB1, PB2 and PA proteins; S4 encoding for the glycoprotein; S5 encoding the nucleoprotein, and S6 encoding the M-like), all support the inclusion of SINUV within the family Orthomyxoviridae (Figure 4, Table 3).

In order to confirm the genetic relationship of SINUV to other orthomyxoviruses, we performed a phylogenetic reconstruction, based on all complete ORFs, that confirms the multiple alignment and box plot approaches. Regardless of the analyzed RNA segment analyzed, the inferred phylogenetic trees depicted SINUV as a separate clade most closely related to members of the Thogotovirus genus (Figure 5a–f). Importantly, SINUV was consistently placed at a basal phylogenetic relationship to all recognized species of the genus isolated from various arthropods and vertebrates including humans. Combining all results obtained for the current analyses (genetic divergence and phylogeny) we conclude that the unique clade position, as well as the genetic similarity (protein similarity) of less than 35% for all encoded proteins indicate that SINUV represents a unique member within the family Orthomyxoviridae. To this date SINUV is the only known member of this genus to have a host-restricted range. Given that the observed phylogenetic reconstructions do not show a deep tree node distance to the rest of the genus members, at this time, it is impossible to reconstruct or identify ancestral host switching processes, as well as to infer the direction of the virus spread to new hosts. Understandably the genetic diversity of this genus will be greatly enriched with future virus discovery studies in various arthopods and should provide valuable information on the properties of new divergent viruses, such as host range restriction to insects and deconstruction of their evolutionary ancestry and pathogenic potential.

Segment 6 of SINUV contains a predicted open reading frame of 271 aa which does not share sequence homology with any known protein, using protein databases (e.g. RCSB PDB, ViPR, Uniprot); but it displays a low amino acid identity of 23% with the M protein of THOV. Further studies are necessary to know the role of this segment of SINUV. Differences in the conserved segment termini are also compatible with a significant evolutionary distance of SINUV from other members of the Thogotovirus genus.

Although the current International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2015) (ICTV) (www.ictvonline.org/virustaxonomy.asp) only lists two species within the genus Thogotovirus, there are now actually eight viruses within the genus: Thogoto (THOV), Dhori (DHOV), Batken (BKNV), Upolu (UPOV), Aransas Bay (ABV), Jos (JOSV), Bourbon (BRBV) and Dielmo orthomyxovirus (DOV) (Allison et al., 2015, Bussetti et al., 2014, Lvov et al., 2015, Briese et al., 2014, Lambert et al., 2015, Temmam et al., 2016). The addition of SINUV to the genus will bring the total number of thogotoviruses to nine. Most of the thogotoviruses have been associated with ticks, although Batken virus has been isolated from both ticks and mosquitoes (Lvov et al, 1974), Sinu virus was isolated from mosquitoes and Dielmo orthomyxovirus was found in Culicoides midges (Temmam et al., 2016).

Seven of the nine thogotoviruses (THOV, DHOV, BKNV, UPOV, ABV, JOSV, and BRBV) replicate in vertebrate (Vero or BHK) cells and cause illness and death in newborn mice (CDC 2016, Lambert et al., 2015). SINUV does not, and only grew in C6/36 cells. The status of DOV is unknown, since it was identified by next-generation sequencing and not isolated. DHOV and THOV have been associated with disease (encephalitis and febrile illness) in humans (CDC, 2016), and THOV has caused abortion in sheep (Davies et al., 1984). BRBV has also been associated with febrile illness and death in humans (Kosoy et al., 2015). The disease potential of the other thogotoviruses, including SINUV, for humans and animals is unknown. With the exception of DOV, all of the other eight thogotoviruses were initially detected by culture (in vitro) in vertebrate or insect cell lines or by inoculation of newborn mice. However, given the tremendous number and diversity of arthropods on Earth and the increasing use of metagenomics to search for novel virus genomes in all life forms (Li et al. 2015, Temman et al. 2016, Shi et al. 2016, Paez-Espino et al. 2016) one can assume that other new thogotoviruses (and quaranjaviruses) will be discovered in non-hematophagous arthropods and other vertebrates.

Supplementary Material

A. Schematic representation of the conserved domains (DI to DV) found in the GP protein of the Isolate CoB 38d and members of the Thogotovirus genus. Pink arrows represents the fusion peptide areas; green dots and red arrows are representing the cysteine (Cys) residues and potential N glycosilation (NGlyc) sites, respectively. B. Number and aminoacid position of the NGlyc sites and the signal peptides (within parenthesis) over the threshold value (0.5).

Box plot analysis of the isolate CoB 38d and other members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. Genetic distance intra and inter groups are indicated in the X-axis as numbers of amino acid substitution/site. Each genus is represented by a unique colored box. Line in the middle of each box represents the mean distance and the size of the boxes are proportional to the genetic distance variation within and between groups.

Graphic representation of the Simplot analysis performed for the concatenated ORFs related to the six encoded proteins (PB2-PB1-PA-HA-NP-M) of the isolate CoB 38d and other thogotoviruses. Traced line represents the threshold value for consider reassortment; Area highlighted in salmon color shows the genomic region with punctual areas of genetic similarity (>0.8) with CoB 38d isolate. Line in green: JOSV; Line in blue: ABV virus; Line in Red : DHOV; Line in grey: THOV; line in yellow: UPOV

Intragroup and intergroup genetic distances (number of aa subsitutions/per site). Segment 2 PB1

Phylogenetic signal by each segment on isolate CoB 38d

Ramachandran (%): Percentage of residues locates on the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot. Prosa: calculated z-scores for the generated models. Identity (%) and positivity (%): values calculated using BLASTP alignments between target and template sequences.

Highlights.

A novel orthomyxovirus-related virus (designated Sinu virus) was isolated from mosquitoes in C6/36 cells.

The complete genome of SINUV was sequenced.

Sequence analysis indicates that SINUV is a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae

SINUV is phylogenetically closest to viruses to the genus Thogotovirus.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements And Support

MAC is supported by a PhD scholarship from the Colombian Department of Science (Colciencias Convocatoria 567). The fieldwork in Colombia was supported in part by Colciencias grant 111549326198. Laboratory work in the USA was funded in part by NIH grant R24 AI120942. We also acknowledge the help of Sandro Patroca da Silva in doing the Boxplot analysis and Richard Hoyos for mosquito collections.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acosta K. La economía de las aguas del río Sinú. Economía y sociedad. 2013;25:79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara LC, Cassol S, Libin P, Deforche K, Pybus OG, Van Ranst M, Galvao-Castro B, Vandamme AM, de Oliveira T. A standardized framework for accurate, high-throughput genotyping of recombinant and non-recombinant viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W634–W642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison AB, Ballard JR, Tesh RB, Brown JD, Ruder MG, Keel MK, Munk BA, Mickley RM, Gibbs SE, Travassos daRosa AP, Ellis JC, Ip HS, Shearn-Bochsler VI, Rogers MB, Ghedin E, Holmes EC, Parrish CR, Dwyer C. Cyclic avian mass mortality in the northeastern United States is associated with a novel orthomyxovirus. J Virol. 2015;89(2):1389–1403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02019-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E, Lipman D. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. PNAS. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitvich BJ, Firth AE. Insect-specific flaviviruses: A systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses. 2015;7(4):1927–1959. doi: 10.3390/v7041927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolling BG, Weaver SC, Tesh RB, Vasilakis N. Insect-specific virus discovery: significance for the arbovirus community. Viruses. 2015;7:4911–14928. doi: 10.3390/v7092851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briese T, Chowdhary R, Travassos da Rosa A, Hutchison SK, Popov V, Street C, Tesh RB, Lipkin WI. Upolu virus and Aransas Bay virus, two presumptive bunyaviruses, are novel members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. J Virol. 2014;88:5298–5309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03391-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussetti AV, Palacios G, Travassos da Rosa A, Savji N, Jain K, Guzman H, Hutchison S, Popov VL, Tesh RB, Lipkin WI. Genomic and antigenic characterization of Jos virus. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:293–298. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.035121-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arbovirus Catalogue. 2016 https://wwwn.cdc.gov/arbocat/VirusBrowser.aspx.

- Chevreux B, Pfisterer T, Drescher B, Driesel AJ, Muller WEG, Wetter T, Suhai S. Using the miraEST assembler for reliable and automated mRNA transcript assembly and SNP detection in sequenced ESTs. Genome Res. 2004;14:1147–1159. doi: 10.1101/gr.1917404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CVS. Diagnóstico Ambiental de la Cuenca Hidrográfica del Río Sinú. Montería. Colombia: 2004. Corporación Autónoma Regional de los Valles del Sinú y del San Jorge, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. ProtTest-HPC: Fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. European Conference on Parallel Processin. 2011:177–184. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies FG, Soi RK, Wariru BN. Abortion in sheep caused by Thogoto virus. Vet Rec. 1984;115:654. doi: 10.1136/vr.115.25-26.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Climate-Data.org. CLIMATE; San Bernardo del Viento: 2016. [Accessed 24 August 2016]. http://en.climate-data.org/location/50073/ [Google Scholar]

- Escoto-Delgadillo M, Flores Romero L, Gomez Flores-Ramos L, Vazquez Torres BM, Torres Mendoza BM, Vazquez Valls E. Comparing RIP, REGA and SIMPLOT software to define the HIV-1 recombination in Mexican population. XVII Int AIDS Conf; 3–8 August 2008; Mex City, Mex. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gombold JL, Raming RF. Analysis of reassortants of genome segments in mice mixedly infected with rotaviruses SA-11 and RRV. J Virol. 1986;57:110–116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.110-116.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Internationl Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. [Accessed 24 August 2016];Virus Taxonomy: 2015 Releases. 2015 www.ictvonline.org/virustaxonomy.asp.

- Junglen S, Drosten C. Virus discovery and recent insights into virus diversity in arthropods. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. BMC. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosoy OI, Lambert AJ, Hawkinson DJ, Pastula DM, Goldsmith CS, Hunt DC, Staples JE. Novel thogotovirus associated with febrile illness and death, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;5:760–764. doi: 10.3201/eid2105.150150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert AJ, Velez JO, Brault AC, Calvert AE, Bell-Sakyi L, Bosco-Lauth AM, Staples JE, Kosoy OI. Molecular, serological and in vitro culture-based characterization of Bourbon virus, a newly described human pathogen of the genus Thogotovirus. J Clin Virol. 2015;73:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullmann JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Shi M, Tian J, Lin X, Kang Y, Chen L, Qin X, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. eLife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lole KS, Bollinger RC, Paranjape RS, Gadkari D, Kulkarni SS, Novak NG, Ingersoll R, Sheppard HW, Ray SC. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol. 1999;73(1):152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lvov DK, Karas FR, Tsyrkin YuM, Vargina SG, Timofeev EM, Osipova NZ, Veselovskaya OV, Grebenyuk YuI, Gromashevski VL, Fomina KB. Batken virus, a new arbovirus isolated from ticks and mosquitos in Kirghiz S.S.R. Archiv Fur Die gesamte Virusforschung. 1974;44:70–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01242183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lvov DK, Shcholkanov MY, Alkhovsky SV, Deryabin PG. Taxonomy and Ecology. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press; 2015. Zoonotic Viruses of Northern Eurasia. [Google Scholar]

- Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik K. R package version 2.0.4. 2016. Cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Espino D, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Pavlopoulos GA, Thomas AD, Huntemann M, Mikhailova N, Rubin E, Ivanova N, Kyrpides NC. Uncovering Earth’s virome. Nat. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature19094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease J, Sooknanan R. A rapid, directional RNA-seq library preparation workflow for Illumina® sequencing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer W, Stamatakis A. Hybrid MPI/Pthreads parallelization of the RAxML phylogenetics code. Parallel & Distributed Processing, Workshops and Phd Forum (IPDPSW), 2010 IEEE International Symposium; IEEE; 2010. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pei J, Kim BH, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. [Accessed 4 April 2016];FigTree v1.1.1: Tree figure drawing tool. 2008 Available: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas X, Giraldo P, Sierra-Correa C. Plan Integral de Manejo DMI Cispatá - La Balsa - Tinajones y sectores aledaños. Serie de Publicaciones Especiales. 2010;18 [Google Scholar]

- Sbrana E, Jordan R, Hruby DE, Mateo RI, Xiao SY, Siirin M, Newman PC, Travassos da Rosa AP, Tesh RB. Efficacy of the antipoxvirus compound ST-246 for treatment of severe orthopoxvirus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:768–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano B. The Sinú river delta on the northwestern Caribbean coast of Colombia: Bay infilling associated with delta development. J South Am Earth Sci. 2004;16:623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Shen MY, Sali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2507–2524. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Lin XD, Vasilakis N, Tian JH, Li CX, Chen LJ, Eastwood G, Diao XN, Chen MH, Chen X, Qin XC, Widen SG, Wood TG, Tesh RB, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. Divergent viruses discovered in arthropods and vertebrates revise the evolutionary history of the Flaviviridae and related viruses. J Virol. 2016;90:659–669. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmam S, Monteil-Bouchard S, Robert C, Baudoin JP, Sambou M, Aubadie-Ladrix M, Labas N, Raoult D, Mediannikov O, Desnues C. Characterization of viral communities of biting midges and identification of novel thogotovirus species and rhabdovirus genus. Viruses. 2016;8(3):77. doi: 10.3390/v8030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilakis N, Guzman H, Firth C, Forrester NL, Widen SG, Wood TG, Rossi SL, Ghedin E, Popov V, Blasdell KR, Walker PJ, Tesh RB. Mesoniviruses are mosquito-specific viruses with extensive geographic distribution and host range. Virol J. 2014;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B, Sali A. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. Vol. 47. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using Modeller; pp. 5.6.1–5.6.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:407–410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DF, Parker RA, Kendrick JS. The box plot: A simple visual method to interpret data. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:916–921. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-11-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S-Y, Guzman H, Zhang H, Travassos da Rosa APA, Tesh RB. West Nile virus infection in the golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus): A model for West Nile encephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:714–721. doi: 10.3201/eid0704.010420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Schematic representation of the conserved domains (DI to DV) found in the GP protein of the Isolate CoB 38d and members of the Thogotovirus genus. Pink arrows represents the fusion peptide areas; green dots and red arrows are representing the cysteine (Cys) residues and potential N glycosilation (NGlyc) sites, respectively. B. Number and aminoacid position of the NGlyc sites and the signal peptides (within parenthesis) over the threshold value (0.5).

Box plot analysis of the isolate CoB 38d and other members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. Genetic distance intra and inter groups are indicated in the X-axis as numbers of amino acid substitution/site. Each genus is represented by a unique colored box. Line in the middle of each box represents the mean distance and the size of the boxes are proportional to the genetic distance variation within and between groups.

Graphic representation of the Simplot analysis performed for the concatenated ORFs related to the six encoded proteins (PB2-PB1-PA-HA-NP-M) of the isolate CoB 38d and other thogotoviruses. Traced line represents the threshold value for consider reassortment; Area highlighted in salmon color shows the genomic region with punctual areas of genetic similarity (>0.8) with CoB 38d isolate. Line in green: JOSV; Line in blue: ABV virus; Line in Red : DHOV; Line in grey: THOV; line in yellow: UPOV

Intragroup and intergroup genetic distances (number of aa subsitutions/per site). Segment 2 PB1

Phylogenetic signal by each segment on isolate CoB 38d

Ramachandran (%): Percentage of residues locates on the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot. Prosa: calculated z-scores for the generated models. Identity (%) and positivity (%): values calculated using BLASTP alignments between target and template sequences.