Abstract

The Zika virus (ZIKV) pandemic is a global concern due to its role in the development of congenital anomalies of the central nervous system. This mosquito-borne flavivirus alternates between mammalian and mosquito hosts, but information about the biogenesis of ZIKV is limited. Using a human neuroblastoma cell line (SK-N-SH) and an Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line (C6/36), we characterized ZIKV infection by immunofluorescence, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and electron tomography (ET) to better understand infection in these disparate host cells. ZIKV replicated well in both cell lines, but infected SK-N-SH cells suffered a lytic crisis. Flaviviruses scavenge host cell membranes to serve as replication platforms and ZIKV showed the hallmarks of this process. Via TEM, we identified virus particles and 60–100nm spherular vesicles. ET revealed these vesicular replication compartments contain smaller 20–30nm spherular structures. Our studies indicate that SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells are relevant models for viral cytoarchitecture study.

Keywords: Flavivirus, Zika Virus, Human Neuroblastoma, SK-N-SH, Aedes albopictus, C6/36, Electron Microscopy, Electron Tomography

INTRODUCTION

Originally discovered in 1947 in a sentinel Rhesus monkey during yellow fever studies in the Zika forest of Uganda and then isolated from mosquitoes in the same region in 1948 (1), ZIKV was regarded as an unimportant mosquito-borne flavivirus until its emergence in Latin America. Currently, multiple countries are reporting autochthonous outbreaks of Zika virus (ZIKV) with continuing mosquito-borne transmission since 2015 (2), and other countries are experiencing significant cases of infection associated with non-vector mediated transmission. These include maternal-fetal transmission (3), sexual transmission from and to both males and females (4–7), and blood transfusion (8). Previously considered a benign disease, ZIKV infection is generally asymptomatic or characterized by mild fever, rash, headaches, and arthralgia (9). However, as the current pandemic has unfolded, it has become evident that ZIKV infection has a profound neurotropism and can cause a number of severe, debilitating and even fatal neurological birth defects such as fetal wasting, microcephaly, seizure disorders, and ocular problems (9–11). Complications have also been noted in adults, including Guillain-Barre syndrome (12), transverse myelitis (13), and meningoencephalitis (14). As a consequence, ZIKV infection is now regarded as a serious disease.

ZIKV is a member of the Flaviviridae family, and is closely related to several other mosquito-borne flaviviruses (MBFV), such as, Dengue, West Nile virus and Yellow Fever (15). Flaviviruses are single-stranded, positive sense RNA viruses. After binding and entry into a cell, the 11kb viral RNA genome is released into the cytoplasm and translated at the endoplasmic reticulum into a single polyprotein. Viral and host proteases cleave this polyprotein into 3 structural (capsid, membrane [M], and envelope [E]) and 7 nonstructural (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) proteins (16).

A remarkable feature of flavivirus biology is the interaction between virus replication and the cellular membranes. These viruses induce a marked proliferation and rearrangement of endoplasmic reticulum membranes and reconfigure them into a variety of vesicular structures that bulge into the ER lumen and serve as replication compartments. Within these compartments, NS5, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, in conjunction with other viral nonstructural proteins and host factors, synthesize a double-stranded viral RNA, and form a replication complex to produce viral progeny genomes. The progeny strands and the viral structural proteins associate on adjacent lamellae of the ER where immature particles are generated and intruded into the ER lumen. The particles are transported to and traverse the Golgi structures, acquiring glycosylation. Finally, in a post-Golgi vesicle, the covalent attachment between the preM and E structural proteins is cleaved by furin and the mature virion is formed and exits the cell (17).

A unique requirement of the viral biology of ZIKV and other MBFV is the need to replicate both in mammalian and mosquito cells. The ultrastructure of a number of vector-borne flaviviruses has been well-studied (18–25). There have been recent reports examining ZIKV infection in human skin cells (26) and African green monkey kidney cells (27). In addition papers have depicted ZIKV replication in cells of neural origin (28, 29). However, the ultimate aim of our work is to characterize the cell biology and cytoarchitecture of ZIKV infection at extremely high resolution microscopy techniques, and for this purpose well-characterized cell lines of relevant origin are required. Therefore, in this study, we characterized the cytoarchitecture of ZIKV replication in human neuroblastoma and Aedes albopictus mosquito cells using a current South American ZIKV isolate. Additionally, we characterized the envelope protein’s localization to the endoplasmic reticulum and visualized the ultrastructural scaffolding of infection. We also employed electron tomography to provide a 3-dimensional comparison of ZIKV infection in both human and mosquito cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Viruses

SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells (HTB-11, ATCC), obtained from a bone marrow sample from a 4-year-old female neuroblastoma patient, were maintained in Eagle’s minimal essential media (EMEM, ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies) (complete EMEM) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Aedes aegypti cells (CCL-125, ATCC) and Aedes albopictus cells were developed by Singh (30) from pools of A. aegypti and A. albopictus larvae, respectively. Singh’s Aedes albopictus cells were further subcloned by Igarashi (31) to create the C6/36 cell line (kindly provided by Dr. Stephen Whitehead, NIH/NIAID). Both mosquito cell lines were cultured in complete EMEM at 28°C, 5% CO2.

Zika virus Paraiba/2015 strain (ZIKV) isolated from a febrile female patient (kindly provided by Drs. Pedro F.C Vasconcelos, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Brazil and Stephen Whitehead, NIH/NIAID) was propagated in African green monkey kidney cells (Vero, ATCC) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.005. Viral titer was done by immunofocus assay as previously described (21) using African green monkey kidney cells (Vero, ATCC), anti-flavivirus group antigen clone D1-4G2-4-15 (4G2, Millipore) as a primary antibody (1:1000 dilution), and anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase antibody (Dako) as a secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution).

Cytopathic effect of infected cells was evaluated via Giemsa staining. Cultures of mock and ZIKV-infected cells were fixed with methanol for 10 minutes followed by staining with a 1:5 dilution of Giemsa stain (aqueous) for 30 minutes. Preparations were then rinsed with water and imaged using a 40× objective an AxioVert.A1 equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam 503 mono camera.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells were plated at 3 × 104 cells/well in 8 well Labtek dishes (Nunc), infected with ZIKV Paraiba (MOI 10), and immunofluorescence assays were performed as previously described (21). Mouse monoclonal Dylight 488-conjugated protein disulfide isomerase 1D3 (PDI, Enzo Life Sciences) was used as a cellular marker for the endoplasmic reticulum. The E protein of ZIKV was localized through the use of anti-flavivirus group antigen antibody, clone D1-4G2-4-15 (4G2, Millipore). Since antibodies against non-structural proteins were not available, staining for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was used as a surrogate marker for virus replication and stained by mouse monoclonal anti-dsRNA J2, IgG2a (English and Scientific Consulting). Secondary antibodies used were: Alexa Fluor 594 & 647-conjugated anti-mouse (Life Technologies). All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000. Cell volumes were determined by observation and measurement of nuclear (DAPI) and anti-E (4G2) staining of ZIKV infected cells using Zen 2012 SP1 software (Zeiss). Fifteen cells for each cell line were imaged and length, width, and height of both the 4G2 label and DAPI determined. Nuclear volumes for SK-N-SH & C6/36 cells were calculated assuming they were spheres. Due to length and width measurements, 4G2 staining volumes for SK-N-SH cells were calculated as rectangles, while C6/36 4G2 volumes were calculated assuming a spherical shape. The average nuclear and anti-E volumes of SK-N-SH cells were 2894 and 7913 µm3, respectively. Those for C6/36 cells were 354 and 645 µm3. Nuclear volumes were subtracted from the anti-E staining volumes to give the approximate volumes of virion/vesicle containing cellular areas.

Apoptosis Detection

Immunofluorescence staining for cleaved (active) caspase 3 as well as TUNEL staining were used to assess apoptosis in ZIKV infected cells. Immunofluorescence was performed as above, using 1:1000 diluted rabbit monoclonal anti-active caspase 3 (Abcam) and 1:1000 diluted Alexa Fluor 594 anti-rabbit specific IgG (Life Technologies). TUNEL staining was performed as in (32) using in situ cell death detection kit, TMR red (Roche).

Electron Microscopy and Tomography

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and tomography, samples were prepared and processed essentially as described previously (21), except that araldite embedding resin (SPI, Inc., West Chester, PA) was substituted for Spurr’s resin. Silver-colored sections were used for TEM. Sections for electron tomography (ET) were cut at a setting of 150 nm, and collected on Formvar/carbon-coated 2 × 1 mm copper or gold slot grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA).

Samples were imaged for TEM and ET as described previously (21), except as follows. Dual-axis tomographic tilt series of serial sections were collected using SerialEM software (University of Colorado, Boulder CO) (33), and Ultrascan camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA). Volumetric reconstructions were created either manually or semi-automatically using the IMOD applications Etomo or Batchruntomo (University of Colorado) (34), respectively. Counting of virions and virus-induced vesicles was performed using a modeling feature in IMOD to highlight spheres of a desired size and track them throughout the tomogram.

RESULTS

Infection of human neuroblastoma and mosquito cells with Zika virus

In Latin America, the enzootic ZIKV is currently circulating in Aedes mosquitoes which then transmit the virus to humans causing disease. Both Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes have been implicated in ZIKV transmission. Therefore, we chose to evaluate the susceptibility of relevant cell lines to the 2015 ZIKV Paraiba, an isolate derived from a recent case in the current Brazilian outbreak. We infected human neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH), Aedes aegypti (CCL–125), and Aedes albopictus (C6/36) cells with ZIKV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Serial samples were collected for determination of viral replication and evaluation of cytopathology. ZIKV replicated well in the SK-N-SH and C6/36 cell lines, reaching titers of 106 focus forming units (ffu) per ml by 72 hours post-ZIKV infection (hpi) in SK-N-SH cells and 96 hpi in C6/36 cells (Fig. 1). Conversely, CCL-125 cells showed negligible virus replication over the time course, with a maximum titer of 60 ffu/ml at 72 hpi (data not shown).

Figure 1. Titer of ZIKV Paraiba in cell culture.

Supernatants from SK-N-SH or C6/36 cells, infected at a MOI of 10, were assayed for viral titer by immunofocus assay. Error bars indicate SEM from three independent experiments.

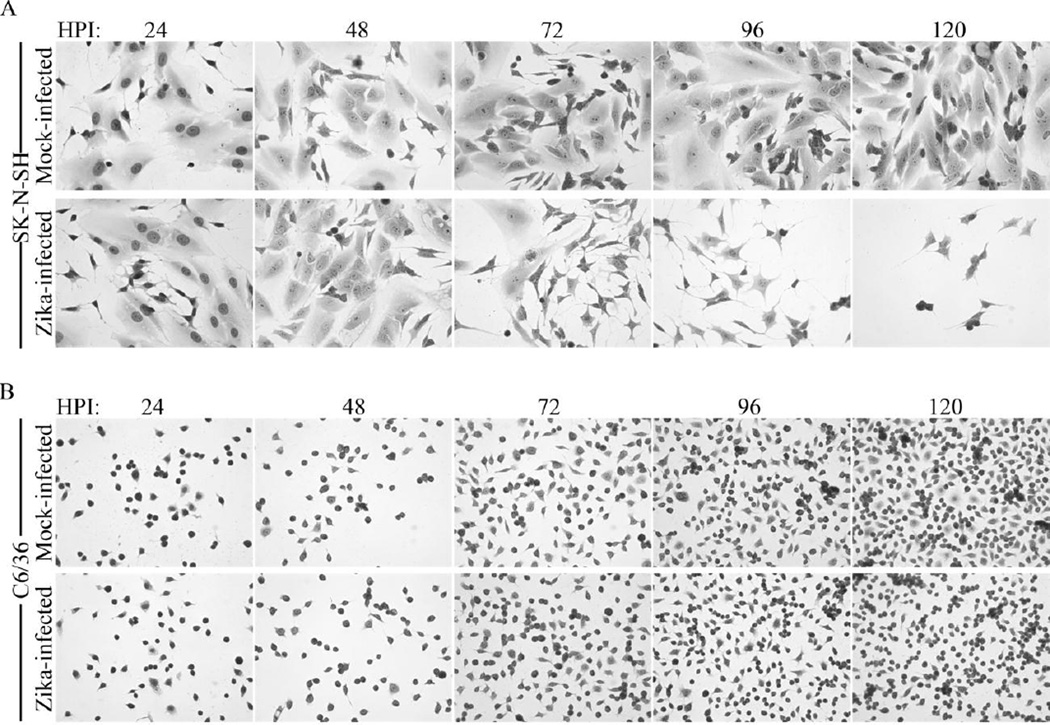

The effects of virus replication on cellular morphology were observed via light microscopy and Giemsa staining for signs of cytopathic effect (CPE). By 48 hpi, CPE as manifest by rounding and cytoplasmic condensation of cells was evident in infected SK-N-SH cells (Fig 2A). By 72 hpi, considerable CPE and sloughing of cells and syncytia formation were evident. After 96 hpi, an acute lytic crisis was apparent and few cells remained attached to the culture dish. On the other hand, C6/36 (Fig 2B) and CCL-125 (data not shown) cells showed no overt signs of CPE over the course of evaluation (120 hpi). Due to the failure of ZIKV to replicate in the CCL-125 cells, we continued our experiments with only the SK-N-SH and C6/36 cell lines.

Figure 2. Replication of ZIKV Paraiba in cell culture.

Phase contrast images of Giemsa stained (A) SK-N-SH or (B) C6/36 cells infected with ZIKV Paraiba (MOI 10) at indicated time points.

Assessment of apoptosis induced by ZIKV in human neuroblastoma and A. albopictus cells

Widespread loss of the monolayer integrity in the neuroblastoma cells by 96–120 hpi suggested activation of cell death pathways. We, therefore, examined two parameters often associated with virus induced cell death: caspase activation and apoptosis. Immunofluorescence studies of infected SK-N-SH cells confirmed the presence of cleaved (active) caspase 3, an executioner caspase, indicating that the apoptosis cascade had been activated in these cells. (Fig. 3). Active caspase 3 staining was noted in some neuroblastoma cells as early as 24 hpi and was extensive by 72 hpi (Fig 3B). The development of apoptosis was confirmed by the use of a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated TMR red-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Fig 4). TUNEL staining was first seen in SK-N-SH cells at 72 hpi but, presumably due to lysis and to cell sloughing, TUNEL positive cells were difficult to find at later time points. Thus, the lytic crisis observed in ZIKV-infected neuroblastoma cells was most likely effected by caspase-mediated apoptosis.

Figure 3. Active caspase 3 staining during ZIKV Paraiba infection in SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells.

Cells were mock-infected (A) or infected with ZIKV Paraiba at a MOI of 10 (B), fixed, and stained for cleaved caspase 3 (red) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). 63× magnification.

Figure 4. TUNEL staining during ZIKV Paraiba infection in SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells.

Cells were mock-infected (A) or infected with ZIKV Paraiba at a MOI of 10 (B), fixed, and TUNEL stained to visualize single-stranded DNA breaks (red) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). DNase I treated cells were used as a positive control and the TUNEL enzyme was omitted from the negative control samples (A). 63× magnification.

In infected C6/36 cells, some cleaved caspase 3 staining was seen at 48 hpi, became more common by 96 hpi and was widespread by 120 hpi. (Fig 3B). Interestingly, when the C6/36 cells were subjected to TUNEL staining, only rare cells were TUNEL positive (Fig 4). These results suggested that progression to apoptosis was being blocked even in the face of caspase activation.

Localization of Zika virus E glycoprotein and site of virus replication in infected human neuroblastoma and A. albopictus cells

Previously studied vector-borne flaviviruses induce a pronounced expansion and rearrangement of ER membranes in infected cells (18, 19, 21–25). ZIKV infection of the human neuroblastoma cells led to a dramatic increase of ER as evidenced by a pronounced increase of staining for protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein, compared to mock infected samples (Fig 5). Signal for the ZIKV E glycoprotein was evident at 24 hpi (data not shown) and by 72 hpi, almost all cells in the culture were positive (Fig 5). E glycoprotein was diffusely present in the cytoplasm and clearly overlapped with the PDI staining (Fig. 5), thus confirming that this viral structural protein was associated with the ER.

Figure 5. Localization of ZIKV E to endoplasmic reticulum (PDI) in SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells.

Cells were mock-infected (A) or infected at a MOI of 10 with ZIKV Paraiba (B), fixed, and stained for ZIKV E protein (4G2, red) and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI, green). Areas of colocalization between these two proteins appear yellow. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). 72 hours post infection, 63× magnification.

To identify sites of virus genome replication, we used an antibody for dsRNA, a surrogate marker for virus replication. A punctate pattern of dsRNA staining that overlapped with PDI staining for ER was clearly present in ZIKV infected neuroblastoma cells (Fig 6). Mock infected cells did not stain for E protein (Fig 5) or dsRNA (Fig 6). Taken together, these results indicated that ZIKV replication was occurring in association with the ER in the neuroblastoma cells.

Figure 6. Localization of dsRNA to endoplasmic reticulum (PDI) in SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells.

Cells were mock-infected (A) or infected with ZIKV Paraiba at a MOI of 10 (B), fixed, and stained for double-stranded RNA (J2, red) and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI, green). Areas of colocalization between these two proteins appear yellow. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). 72 hours post infection, 63× magnification.

In C6/36 cells, ER expansion was apparent but slightly less obvious due to cell morphology (Fig 5). The C6/36 cells are noticeably smaller than the SK-N-SH cells and more rounded in shape making differences in ER levels less striking than in the SK-N-SH. C6/36 cells showed a one day delay in reaching similar levels of ZIKV E protein staining at 48 hpi to those seen in SK-N-SH cells at 24 hpi (Fig 5). Viral replication, as denoted by dsRNA staining, was similar in pattern and amount, but again delayed by 24 hours compared with the neuroblastoma cells (Fig 6). The delay in both ZIKV E protein and dsRNA staining corresponds with the viral titer seen in these two cell lines. In brief this data shows that, like other flaviviruses, ZIKV replication occurs within the confines of the ER in both mosquito and human cells.

The ultrastructure of ZIKV replication in human neuroblastoma and A. albopictus cells

After performing immunofluorescence assays to characterize ZIKV replication in both SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy, we turned to transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visualize the cytoarchitecture of ZIKV infection in both human and mosquito cells at high resolution. In SK-N-SH cells, low magnification TEM images showed dramatic ER proliferation compared with mock-infected cells (Fig 7A–B), encompassing nearly all of the cytoplasm (Fig 7C). As has been reported for other flaviviruses (18, 19,21–23, 35–38), ZIKV-induced vesicular replication compartments (or spherules), measuring 60–100nm in diameter, were found within the rough-ER lumen, often in closely packed groups (Fig 7E). Sometimes within the spherules, vesicles that appear to be a smaller sized (20–40nm) were seen (Fig 7E), however, we believe this to be due to the plane of section through the sample and not a difference in structure. Additionally, TEM showed virus particles (~30 nm in diameter), within membranes of the ER. The virions were often observed in small groups resembling “peas in a pod.” (Fig.7G).

Figure 7. Ultrastructure of ZIKV Paraiba infection.

Cells were mock-infected (A–B) or ZIKV Paraiba infected at a MOI of 10 (C–H), fixed, resin embedded, 70nm section cut, and processed for transmission electron microscopy (see Materials and Methods). (C–D) Lower magnification showing ER proliferation comprising the majority of the cytoplasm. (E–H) Higher magnification showing round vesicles surrounded by ER membrane with virions present. Scale bars shown in inset.

In the C6/36 cells, significant accumulations of ER expansion were also seen in ZIKV infected cells (Fig 7D). With additional magnification, numerous vesicles (60–100nm in diameter) were seen scattered within the ER scaffold (Fig 7F&H). Virions were intermixed with these vesicles within the ER membranes, showing similar size (~30nm) and distribution as seen with the neuroblastoma cells (Fig 7F&H).

Like in other flavivirus studies (18, 19, 21, 23), open necks or communicating pores between adjacent vesicles or connecting vesicles to the cytoplasm were seen in both cell lines. Previous works (19, 23) have also noted structures within the vesicles, which are believed to be the actual replication complexes. We observed these structures in both SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells; however, in some vesicles, the structures internal to the vesicle had a ring-like appearance and a diameter of 20–30nm (Fig 7H).

Three-dimensional electron tomography of ZIKV replication in human neuroblastoma and A. albopictus cells

The use of dual-axis electron tomography (ET) provided significant additional information to the 2-D images described in the previous section. The 3-D imagery clearly demonstrated that spherical replication compartments intruded into ER cisternae and were attached to the lamella of the ER in both the human neuroblastoma (Fig 8A and Movie S1) and A. albopictus (Fig 8B and Movie S2) cells. A small number of the vesicular replication compartments were obviously tubular rather than spherical in form, as has been reported in other flavivirus models (18, 21,23, 35–38).

Figure 8. Electron tomography of ZIKV Paraiba-infected SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells.

SK-N-SH (A) or C6/36 (B) cells were infected at a MOI of 10, fixed, embedded in epoxy resin, and 150 nm sections cut for dual-axis electron tomography. Panels show the 3-D surface rendering of convoluted membrane (green). Scale bar shown in inset of rendered images.

The dual-tilt tomography also revealed that the circular structures noted within the vesicles were, in fact, “hollow” spherical structures, approximately 20–30nm in diameter, an observation not evident by standard TEM (Movie S1 & S2). Interestingly, these smaller spheres sometimes appeared attached to the wall of the vesicle where the vesicles were contiguous with the ER lamellae (Fig 8A & B, insets). Tomography confirmed that the virions were in membrane bound profiles of ER, and in some cases, they were adjacent to the replication compartments (Fig 8A & B). We did not observe any obvious structures suggestive of nascent virions budding into the ER.

In an effort to estimate of the number of vesicles and virions within a single cell, we utilized a software modeling function of the IMOD suite, described in the materials and methods, to select and enumerate these structures within the chosen imaging areas in both cell lines. In the SK-N-SH cells, 598 virus particles and 267 virus-induced vesicles were counted per cubic micrometer. Fewer virions and vesicles were seen in the C6/36 cells, 212 and 188 per cubic micrometer, respectively. These values, although accurate for the sections imaged, are almost certainly not representative of the entire infected cell volume, as areas enriched for vesicles, virions, and proliferated ER were preferentially chosen for ET imaging. However, in an effort to estimate the amount of virions and vesicles present per cell, we determined, via confocal microscopy (described in material and methods), the approximate volume of 4G2 antibody staining material for each cell line to allow extrapolation of the particle and vesicles counts established by our ET experiments. For SK-N-SH cells, this calculated to 3×106 virions and 1×106 vesicles per cell while the smaller C6/36 cells were estimated to have 2×105 virions and 2×105 vesicles per cell. Virus particle and vesicles counts for both cells lines were performed at the 72hpi time point. Interestingly, the one log difference in virion and vesicle counts between SK-N-SH and C6/36 cells parallels the one log difference seen in virus titer (Fig 1) at this time point.

DISCUSSION

The recent explosion of ZIKV infections in Latin America has led to a surge of interest in this emerging virus. Amid global travel concerns and a paucity of information on the effects of ZIKV on humans, ZIKV research has quickly expanded. Driving much of the concern is the pronounced neurotropism of this virus as well as the expanding catalog of structural and functional neurological problems patent in infected human fetuses and newborns (9). In order to model and study the cytoarchitecture and cell biology of ZIKV, the human neuroblastoma cell line, SK-N-SH, offers a convenient in vitro model system. We have shown these cells to be permissive for ZIKV infection in their undifferentiated state supporting virus production of up to 107 ffu/ml. ZIKV replication in these cells, illuminated by immunofluorescence, was characterized by abundant staining for the E glycoprotein, increasing quantities of dsRNA, and expansion of the ER as infection progressed. Furthermore, clear evidence of caspase mediated programmed cell death was apparent in the neuroblastoma cell line, leading to an acute lytic crisis. This is very similar to observations from our lab with a tick-borne flavivirus (32, 39), where the lytic crisis is followed by the initiation and long-term maintenance of a persistent infection. In the light of long-term presence of ZIKV in human semen (6), it will be important to determine if ZIKV persistence can also be established in SK-N-SH cells and to characterize that state. Furthermore, the SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells undergo differentiation and neurite generation when treated with retinoic acid (40). Recent work by others (29) has found that differentiation of some neuroblastoma cell lines can confer a resistance to ZIKV infection. It would be interesting to determine if this occurs with the SK-N-SH cells, to examine terminally differentiated neuroblastoma cells for ultrastructural changes that may not be apparent via immunofluorescence, and finally to determine the mechanism for the resistance.

As an arbovirus virus, ZIKV is cycled between Aedes mosquitoes and vertebrate hosts. Therefore, in addition to looking at neuroblastoma cells, we wanted to characterize the cytoarchitecture of ZIKV replication in mosquito cells as well. The primary vector for ZIKV is Aedes aegypti so we first tried to infect CCL-125, a cell line derived from A. aegypti larvae (30). Our attempts to infect CCL-125 with ZIKV saw very minimal virus production, and the cells showed no signs of morphological changes 120 hours after ZIKV infection. Early studies reported a lack of susceptibility of CCL-125 to some mosquito-borne flaviviruses (Japanese encephalitis and Dengue 1–4), despite a permissiveness for West Nile virus (41). However, a more recent report showed that Dengue-2 did replicate in the CCL-125 cells (42). Thus, the resistance of CCL-125 to ZIKV may not be entirely unexpected.

Since Aedes albopictus mosquitoes have also been implicated in ZIKV transmission, we examined the C6/36 cells derived from this species. Although C6/36 cells showed no morphological changes via light microscopy with ZIKV infection, they were clearly permissive for ZIKV. Infected cells yielded amounts of virus and developed immunofluorescence staining patterns that were similar to the human neuroblastoma cells. Morphologically, we noted no detrimental effects of ZIKV infection on the C6/36 cells (Fig 2B). Staining for cleaved caspase 3 was first noted at 48 hpi in these cells and was evident at later times points, too; however, only rare mosquito cells were TUNEL positive from 72–120 hpi, indicating that widespread frank apoptosis was not induced. Although we have not investigated these findings, the lack of apoptosis in ZIKV-infected C6/36 cells may be related to upregulation of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) genes which have been shown to be operative in Dengue 2 virus-infected C6/36 cells (43) or, perhaps, through inhibition of a molecule downstream of caspase-3 within the apoptosis pathway. Further studies into ZIKV infection and the apoptotic pathway in mosquito cells are required to better understand the role of caspase activation and cell death.

When examined at the ultrastructural level by TEM and ET, the cytoarchitecture of ZIKV replication was very similar in both mammalian and mosquito cell lines. Both cell types exhibited the hallmark membrane proliferation and rearrangements seen with many positive-strand RNA viruses (20). The 60–100 nm spherical virus-induced replication compartments were abundant and a clear apposition to the ER lamella was evident. The structures within the replication compartments were revealed by ET to be 20–30 nm “hollow” spherical structures that abutted the connection between the replication compartment and the adjacent cytoplasm. Some of the replication compartments were clearly tubular in profile, but still had the smaller internal structures. Others have shown that these smaller structures within the replication compartments can be disrupted by RNase treatment under condition specific for dsRNA digestion (19). Future experiments are planned to better characterize the biogenesis of the replication compartments as well as the full complement of viral and cellular components contained therein.

Virus particles were evident in the ER cisternae and in some instances were immediately adjacent to replication compartments. The virions we observed were ~30nm in diameter, in contrast to the 50nm diameter reported for purified ZIKV particles (44, 45). We believe this difference to be related to differences in virus particle maturity between purified virus particles and particles we observed that are likely nucleocapsids located within the lumen of the ER (36, 46). We did not identify any structures consistent with immature virions budding into the ER in either cell line. It is likely that higher resolution microscopy will be required to identify immature budding virions. In summary, we have performed initial characterization of ZIKV in two very relevant cell types. This work will provide a solid framework for the detailed study of viral biogenesis and assembly.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

First electron tomography of Zika virus cytoarchitecture

Comparison of Zika virus infection in human neuroblastoma & mosquito cells

Ultrastructure of Zika virus infection in human neuroblastoma & mosquito cells

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIH/NIAID.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smithburn KC. Studies on Certain Viruses Isolated in the Tropics of Africa and South America. Immunological Reastions As Determined by Cross-Neutralization Tests. Journal of Immunology. 1951;68:441–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Zika Situation Report. 2016 http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/situation-report/28-april-2016/en/. Accessed.

- 3.Brasil P, Pereira JP, Gabaglia CR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Carvalho de Sequeira P, Siqueira AM, Abreu de Carvalho LM, Contrim da Cunha D, Calvet GA, Neves ES, Moreira ME, Rodrigues Baiao AE, Nassar de Carvalho PR, Janzen C, Valderramos SG, Cherry JD, Bispo de Filippis AM, Nielsen-Saines K. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro-Preliminary Report. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, Blitvich BJ, Travassos da Rosa A, Haddow AD, Lanciotti RS, Tesh RB. Probable Non-Vector-borne Transmission of Zika Virus, Colorado, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17:880–882. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. First Female-to-Male Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus Infection Reported in New York City. CDC Newsroom Releases. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turmel JM, Abgueguen P, Hubert B, Vandamme YM, Maquart M, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Leparc-Goffart I. Late Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus Related to Persistence in the Semen. The Lancet. 2016;387:2501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30775-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musso D, Roche C, Robin E, Nhan T, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V-M. Potential Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2015;21:359–361. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musso D, Nhan T, Robin E, Roche C, Bierlaire D, Zisou K, Shan Yan A, Cao-Lormeau V-M, Broult J. Potential for Zika Virus Transmission Through Blood Transfusion Demonstrated During an Outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.14.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson KB, Thomas SJ, Endy TP. The Emergence of Zika Virus: A Narrative Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.7326/M16-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, Almeida Sacramento G, Icksang Ko A, Maia M, Belfort R., Jr Oculuar Findings in Infants With microcephaly Associated with Presumed Zika Virus Congential Infectino in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2016;134:529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slavov SN, Otaguiri KK, Kashima S, Covas DT. Overview of Zika virus (ZIKV) Infection in Regards to the Brazilian Epidemic. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2016;49:e5420. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20165420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika Virus in the Americas- Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mecharles S, Herrmann C, Poullain P, Tran T-H, Deschamps N, Mathon G, Landais A, Breurec S, Lannuzel A. Acute Myelitis Due to Zika Virus Infection. The Lancet. 2016;387:1481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carteaux G, Maquart M, Bedet A, Contou D, Brugieres P, Fourati S, de Langavant LC, de Broucker T, Brun-Buisson C, Leparc-Goffart I, Dessap AM. Zika Virus Associated with Meningoencephalitis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:1595–1596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J, Smith AM, Fernandez E, Cabrera OH, Garber C, Noll M, Klein RS, Noguchi KK, Mysorekar IU, Diamond MS. Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy in Mice Causes Placental Damage and Fetal Demise. Cell. 2016;165:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartenschlager R, Miller S. Molecular Aspects of Dengue Virus Replication. Future Medicine. 2008;3:155–165. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roby JA, Setoh YX, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. Post-translational Regulation and Modifications of Flavivirus Structural Proteins. Journal of General Virology. 2015;96:1551–1569. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CKE, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krinjinse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. Composition and Three-Dimensional Architecture of the Dengue Virus Replication and Assembly Sites. Cell Host & Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie LK, Hoenen A, Morgan G, Mackenzie JM. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Provides the Membrane Platform for Biogenesis of the Flavivirus Replication Complex. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:10438–10447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero-Brey I, Bartenschlager R. Viral Infection at High Magnification: 3D Electron Microscopy methods to Analyze the Architecture of Infected Cells. Viruses. 2015;7:6316–6345. doi: 10.3390/v7122940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Offerdahl DK, Dorward DW, Hansen BT, Bloom ME. A Three-Dimensional Comparison of Tick-Borne Flavivirus Infection in Mammalian and Tick Cell Lines. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miorin L, Romero-Brey I, Maiuri P, Hoppe S, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R, Marcello A. Three-Dimensional Architecture of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Replication Sites and Trafficking of the Replicated RNA. Journal of Virology. 2013;87:6469–6481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03456-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junjhon J, Pennington JG, Edwards TJ, Perera R, Lanman J, Kuhn RJ. Ultrastructural Characterization and Three-Dimensional Architecture of Replication Sites in Dengue Virus-Infected Mosquito Cells. Journal of Virology. 2014;88:4687–4697. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteman MC, Popov V, Sherman MB, Wen J, Barrett ADT. Attenuated West Nile Virus Mutant NS1 130-132QQA/175A/207A Exhibits Virus-Induced Ultrastructural Changes and Accumulation of Protein in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Journal of Virology. 2014;89:1474–1478. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02215-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bily T, Palus M, Eyer L, Elsterova J, Vancova M, Ruzek D. Electron Tomography Analysis of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Infection in Human Neurons. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:10745. doi: 10.1038/srep10745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertiop N, Perea-Lecoin M, Surasombatpattana P, Talignani L, Thomas F, Cao-Lormeau V-M, Choumet V, Briant L, Despres P, Amara A, Yssel H, Misse D. Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. Journal of Virology. 2015;89:8880. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00354-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira Barreto-Vieira D, Barth OM, da Silva MAN, Cardoso Santos C, da Silva Santos A, Filho JBF, Bispo de Filippis AM. Ultrastructure of Zika Virus Particles in Cell Cultures. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2016 doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Tang H, Song H, Ming G-l. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Minibioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell. 2016;165:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes BW, Addanki KC, Sriskanda AN, McLean E, Bagasra O. Infectivity of Immature Neurons to Zika Virus: A Link to Congenital Zika Syndrome. EBioMedicine. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh K. Cell Cultures Derived from Larvae of Aedes Albopictus and Aedes Aegypti. Current Science. 1967;36:506–508. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igarashi A. Isolation of a Singh's Aedes albopictus Cell Clone Sensitive to Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses. Journal of General Virology. 1978;40:531–544. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-40-3-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mlera L, Lam J, Offerdahl DK, Martens C, Sturdevant D, Turner C, Porcella SF, Bloom ME. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals a Signature Profile for Tick-Borne Flavivirus Persistence in HEK 293T Cells. MBio. 2016;7:314–316. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00314-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mastronarde D. Automated Electron Microscope Tomography Using Robust Prediction of Specimen Movements. Journal of Structural Biology. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kremer J, Mastronarde D, McIntosh J. Computer Visualization of Three-Dimensional Image Data Using IMOD. Journal of Structural Biology. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takasaki T, Takada K, Kurane I. Electron Microscopic Study of Persistent Dengue Virus Infection: Analysis Using a Cell Line Persistently Infected with Dengue-2 Virus. Intervirology. 2001;44:48–54. doi: 10.1159/000050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hase T, Summers P, Eckels K, Baze W. An Electron and Immunuoelectron Microscopic Study of Dengue-2 Virus Infection of Cultured Mosquito Cells: Maturation Events. Archives of Virology. 1987;92:273–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01317484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grief C, Galler R, Cortes L, Barth O. Intracellular Localisation of Dengue-2 RNA in Mosquito Cell Culture Using Electron Microscopic in situ Hybridization. Archives of Virology. 1997;142:2347–2357. doi: 10.1007/s007050050247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barth O. Replication of Dengue Viruses in Mosquito Cell Cultures- A Model From Ultrastructural Observations. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87:565–574. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761992000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mlera L, Offerdahl DK, Martens C, Porcella SF, Melik W, Bloom ME. Development of a Model System for Tick-Borne Flavivirus Persistence in HEK 293T Cells. MBio. 2015;6:e00614–e00615. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00614-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraveka JM, Li L, Bielawski J, Obeid LM, Ogretmen B. Involvement of Endogenous Ceramide in the Inhibition of Telomerase Activity and Induction of Morphologic Differentiation in Response to All-trans-retinoic Acid in Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;419:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh K, Paul SD. Multiplication of Arboviruses in Cell Lines From Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Current Science. 1968;37:65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wikan N, Kuadkitkan A, Smith DR. The Aedes aegypti cell line CCL-125 is Dengue Virus Permissive. Journal of Virological Methods. 2009;157:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen T-H, Lo T-P, Yang C-F, Chen W-J. Additive Protection by Antioxidant and Apoptosis-Inhibiting Effects on Mosquito Cells with Dengue 2 Virus Infection. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:e1613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostyuchenko VA, Lim EX, Zhang S, Fibriansah G, Ng TS, Ooi JS, Shi J, Lok SM. Structure of the thermally stable Zika virus. Nature. 2016;533:425–428. doi: 10.1038/nature17994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sirohi D, Chen Z, Sun L, Klose T, Pierson TC, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. The 3.8 A resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science. 2016;352:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackenzie JM, Westaway EG. Assembly and maturation of the flavivirus Kunjin virus appear to occur in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and along the secretory pathway, respectively. J Virol. 2001;75:10787–10799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10787-10799.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.