ABSTRACT

Tuberculosis (TB) remains among the most deadly diseases in the world. The only available vaccine against tuberculosis is the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which does not ensure full protection in adults. There is a global urgency for the development of an effective vaccine for preventing disease transmission, and it requires novel approaches. We are exploring the use of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as a vector for antigen delivery to mucosal sites. Here, we demonstrate the successful expression and surface display of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis fusion antigen (comprising Ag85B and ESAT-6, referred to as AgE6) on Lactobacillus plantarum. The AgE6 fusion antigen was targeted to the bacterial surface using two different anchors, a lipoprotein anchor directing the protein to the cell membrane and a covalent cell wall anchor. AgE6-producing L. plantarum strains using each of the two anchors induced antigen-specific proliferative responses in lymphocytes purified from TB-positive donors. Similarly, both strains induced immune responses in mice after nasal or oral immunization. The impact of the anchoring strategies was reflected in dissimilarities in the immune responses generated by the two L. plantarum strains in vivo. The present study comprises an initial step toward the development of L. plantarum as a vector for M. tuberculosis antigen delivery.

IMPORTANCE This work presents the development of Lactobacillus plantarum as a candidate mucosal vaccine against tuberculosis. Tuberculosis remains one of the top infectious diseases worldwide, and the only available vaccine, bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), fails to protect adults and adolescents. Direct antigen delivery to mucosal sites is a promising strategy in tuberculosis vaccine development, and lactic acid bacteria potentially provide easy, safe, and low-cost delivery vehicles for mucosal immunization. We have engineered L. plantarum strains to produce a Mycobacterium tuberculosis fusion antigen and to anchor this antigen to the bacterial cell wall or to the cell membrane. The recombinant strains elicited proliferative antigen-specific T-cell responses in white blood cells from tuberculosis-positive humans and induced specific immune responses after nasal and oral administrations in mice.

KEYWORDS: Lactobacillus plantarum, LAB, tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mucosal vaccine, bacteriology, immunology, lactic acid bacteria

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB) and remains among the most deadly human pathogens (1). About one-third of the world's population is infected with M. tuberculosis, and in 2014, the bacterium killed about 1.5 million people, of which 1.1 million were HIV negative (2). The current vaccine against TB is an attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis known as bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). The BCG vaccine prevents TB in infants with high efficacy, but it fails to protect against pulmonary disease in adolescents and adults (3, 4). In addition, the current BCG vaccine is not recommended for use in HIV-infected individuals, especially infants (5, 6). Therefore, the development of an effective vaccine for preventing disease transmission is urgent and remains a global priority. Currently, 15 vaccine candidates undergoing clinical trials are targeted to adolescents and adults rather than to children (2).

The most commonly used M. tuberculosis antigens are proteins produced by actively growing and metabolizing bacteria, such as proteins from the antigen 85 family (Ag85A, Ag85B, and Ag85C), which are considered virulence factors with high immunogenicity (7–9). Proteins belonging to the ESAT-6 family also possess strong antigenic properties and are known to be the main targets for T cells in the early infection phase (10, 11). Immunity to TB involves numerous different mechanisms, cell subsets, and cytokines (9, 12, 13). It is well established that the induction of a Th1 response, with the essential role of CD4+ T cells and contributions of interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, is a critically important element of the protective response against TB (12–15).

Bacteria are interesting potential vectors for the delivery of vaccines, particularly mucosal vaccines (16–20). Bacteria are simple to culture by fermentation, and access to a large genetic engineering toolbox allows for control of antigen expression and fine-tuning of antigenic properties. The approach of using microorganisms as a delivery vector for antigens has already been applied to developing a mucosal vaccine against TB. Live recombinant attenuated Salmonella strains secreting an M. tuberculosis fusion antigen induce Th1 responses when used as oral vaccines (21). Furthermore, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium engineered to deliver a DNA vaccine against TB elicits a specific immune response in mice and provides protection to the lungs and spleen after intranasal immunization (22). Recombinant variants of the commensal bacterium Streptococcus mitis expressing M. tuberculosis Ag85B have been shown to colonize gnotobiotic piglets and induce production of specific IgG and IgA antibodies after oral administration (23).

Nonpathogenic Gram-positive food-grade bacteria, particularly lactic acid bacteria (LAB), have been widely exploited as an alternative to attenuated pathogens. Due to their safe status and well-developed genetic engineering methods, LAB have a great potential as delivery vectors for antigens. Results from studies over the past 25 years show progress in the development of LAB as mucosal vaccine vectors (19, 24–28). Several lactic acid bacteria belonging to the Lactobacillus genus are known to modulate the immune system by interacting with dendritic cells (DCs) and to skew a subsequent T-cell response toward Th1 polarization (29). The immunomodulatory properties of lactobacilli vary between strains (30, 31), and Lactobacillus plantarum was described as a potential immunological adjuvant in the late 1970s (32). Currently, many studies support the view that L. plantarum enhances the mucosal immune response without negatively influencing immune homeostasis (33). These traits increase the attractiveness of L. plantarum as a candidate vehicle for antigen delivery.

In this study, we exploited L. plantarum for production of M. tuberculosis antigens, with the ultimate aim of developing a candidate mucosal vaccine against tuberculosis. We developed bacteria that display a fusion protein comprising the antigens Ag85B and ESAT-6 (referred to as AgE6) on the surface using one of two different anchoring domains: an N-terminal lipoprotein anchor or a C-terminal cell wall anchor. Using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from TB-positive blood donors, we show that AgE6-producing L. plantarum strains induced antigen-specific memory T-cell responses in vitro. Subsequently, we investigated the immunogenic potential of our strains in vivo using a mouse model.

RESULTS

Construction of L. plantarum strains for display of the AgE6 fusion antigen.

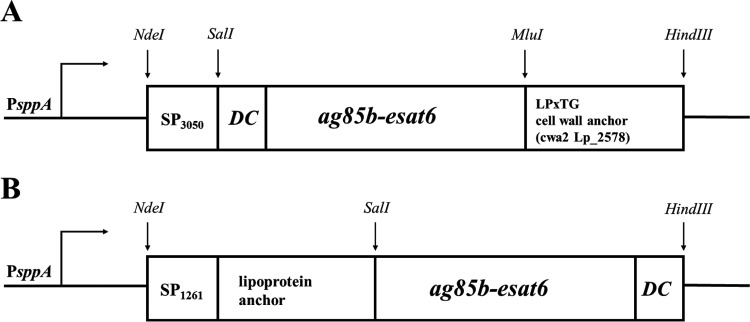

Two different anchors were used for surface display of the AgE6 hybrid antigen, and a schematic overview of the generated expression vectors is provided in Fig. 1. The expression plasmids were constructed to link the AgE6 protein to the cell surface via a C-terminal cell wall anchor (Fig. 1A) or an N-terminal lipoprotein anchor (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Expression cassettes for production of surface-displayed AgE6. All parts of the cassette are easily exchangeable using the indicated restriction sites. (A) C-terminal anchoring to the cell wall was accomplished by fusing the N terminus of AgE6 to the signal peptide from Lp_3050 (SP3050) and the C terminus to a cell wall anchor from Lp_2578 (cwa2, which comprises the C-terminal 194 residues of Lp_2578) (34). (B) N-terminal anchoring via a lipoprotein anchor was achieved by fusing the N terminus of AgE6 to residue 75 of Lp_1261 (this part of Lp_1261 includes a 23-residue signal peptide, SP1261). The position of the 12-residue DC-binding peptide (DC) is also indicated. PsppA indicates the pheromone-inducible promoter that drives gene expression.

For C-terminal anchoring, we selected a cell wall anchor (cwa2) derived from Lp_2578 (34) that contains an LPXTG domain, which is expected to lead to covalent binding to the peptidoglycan. In addition, a peptide with known affinity for dendritic cells (DCs) (35, 36) was fused to the N-terminal end of the fusion protein. After C-terminal anchoring to the peptidoglycan, the N-terminal DC-binding peptide was expected to protrude from the bacterial cell surface (Fig. 1A).

In the second construct, we used a lipoprotein anchor derived from Lp_1261, which is expected to lead to covalent binding of the N terminus to the cell membrane (37). The N-terminal end of the AgE6 protein was fused to the lipoprotein anchor, whereas the DC-binding peptide was fused to the C-terminal end of the antigen such that it was expected to protrude from the bacterial cell (Fig. 1B). As a negative control, we used an L. plantarum strain harboring the empty vector pEv (37).

Production and surface display of AgE6.

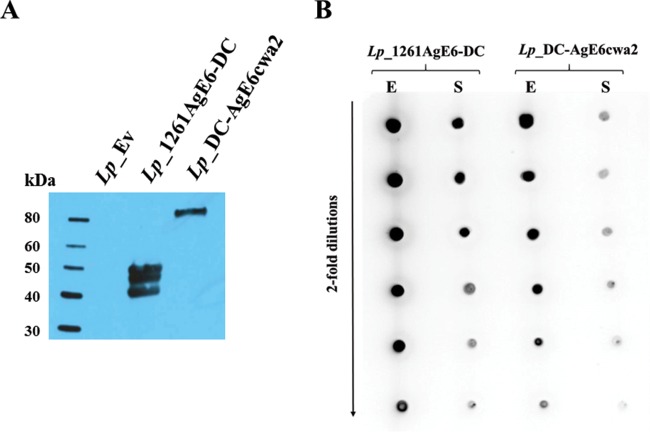

To induce the expression of anchor-fused AgE6 protein, we added a peptide pheromone to growing recombinant L. plantarum strains (38). We then analyzed protein production in crude cell-free protein extracts by Western blotting using an anti-ESAT-6 antibody (Fig. 2A). The protein extracts from L. plantarum bacteria harboring pLp_1261AgE6-DC showed a band of the expected size (48.4 kDa) and two additional bands of slightly smaller sizes that most likely were breakdown products. The protein extracts from the strain harboring pLp_3050DC-AgEcwa2 showed only one distinct band. The molecular mass of this protein was higher than the expected 61.2-kDa size. Such a shift is commonly observed when using the cwa2 anchor (34, 39, 40) and likely results from covalent binding to the peptidoglycan layer. No bands were observed in the protein extracts from the negative-control strain. Additionally, we evaluated the amount of surface-coupled AgE6 relative to the total amount of AgE6 produced by the bacterial cells (Fig. 2B) and we compared production by the two AgE6-displaying L. plantarum strains. Intact bacterial cells were used to determine surface-located AgE6, whereas crude protein extracts were used to detect total AgE6. The dot-plot analysis revealed stronger signals for Lp_1261AgE6-DC in both the surface-located and total protein fractions (Fig. 2B). The data show that Lp_1261AgE6-DC produced more antigen than did Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 and that a larger fraction of the antigen was targeted to the cell surface.

FIG 2.

Detection of AgE6 produced by L. plantarum strains. (A) The anchor-fused AgE6 in strains Lp_1261AgE6-DC (predicted size, 48 kDa) and Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 (predicted size, 61 kDa) was analyzed by Western blotting. A strain harboring the pEv plasmid (empty vector) (37) was used as a negative control. (B) Comparison of AgE6 fractions in total protein extracts (E) and surface-located AgE6 detected on intact bacterial cells (S) for both antigen-producing strains. In both analyses, bacterial cultures were harvested 3 h after induction and the hybrid AgE6 was detected using a monoclonal mouse anti-ESAT-6 antibody and polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse HRP-conjugated IgG. The data presented are from one representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times and gave similar results.

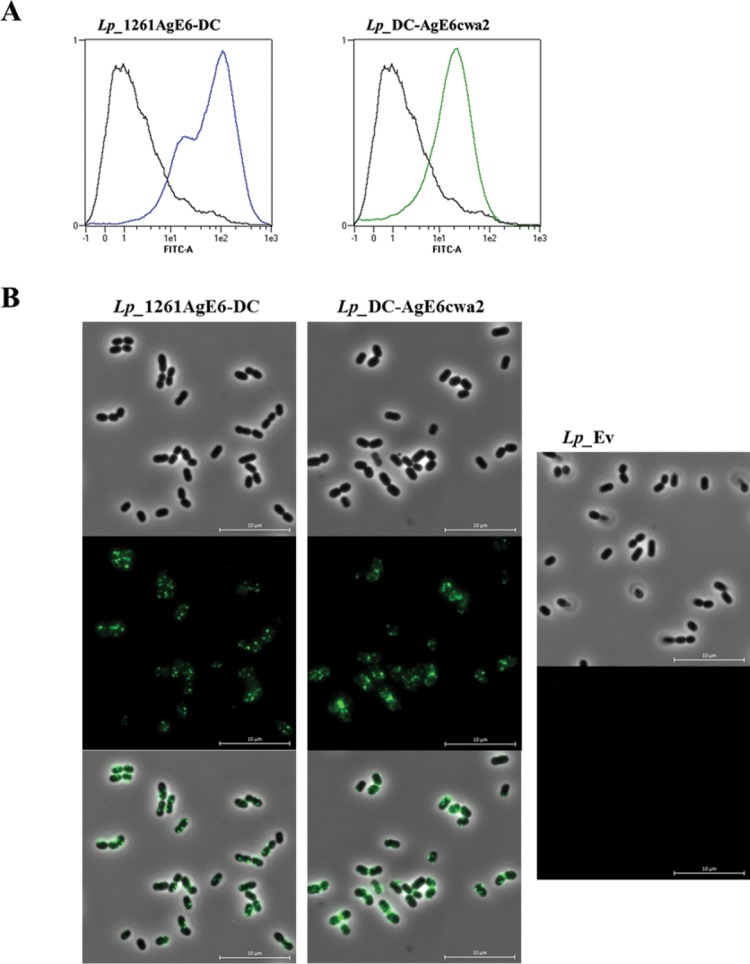

After labeling of live bacteria with an anti-ESAT-6 antibody, surface display of the AgE6 antigen was investigated by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B). Figure 3A shows a substantial increase in fluorescence intensity for the antigen-producing bacteria compared to that in the negative control. The flow cytometry data were confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy, which revealed green cells for only the strains expected to have AgE6 at the surface (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Analysis of the surface localization of AgE6 by flow cytometry (A) and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (B). L. plantarum cells harboring plasmids designed for N- or C-terminal anchoring of AgE6 were probed with a mouse anti-ESAT-6 monoclonal antibody and subsequently with an FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody. L. plantarum harboring the pEv plasmid, lacking the antigen gene fragment, was used as a negative control (black line in both histograms in panel A). Panel B shows bright field, fluorescence, and overlay images. The data presented are from one representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times and gave similar results.

Antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses of human PBMCs.

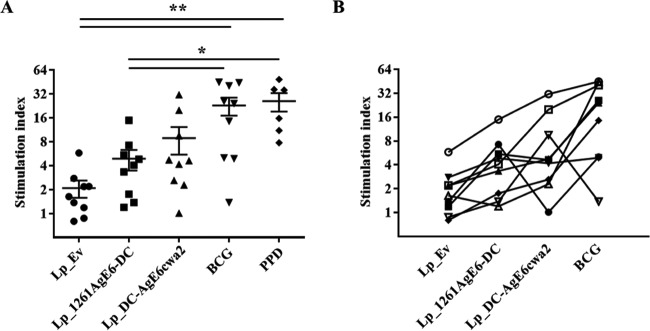

To investigate the ability of AgE6-producing Lactobacillus bacteria to induce an antigen-specific immune response in vitro, we stimulated PBMCs purified from TB-positive donors with the recombinant bacteria and measured T-cell responses (Fig. 4). The proliferation of lymphocytes induced by AgE6-producing Lactobacillus bacteria was higher than in the negative control, Lp_Ev (Fig. 4), and the two AgE6-expressing strains induced similar proliferative responses. We also observed proliferation in response to BCG and purified protein derivative (PPD), confirming that the cells from TB-positive donors responded to M. tuberculosis antigens.

FIG 4.

Proliferation of PBMCs isolated from TB-positive blood donors presented for grouped (A) and individual (B) donors. PBMCs were purified from individual donors and stimulated with Lp_Ev, Lp_1261AgE-DC, Lp_DC-AgEcwa2, BCG, or PPD for 8 to 10 days. Lymphocyte proliferation was measured using the thymidine incorporation assay. Each point represents an average of technical triplicates for one donor and is presented as a stimulation index (fold change relative to unstimulated cells). The results per group presented in panel A are the means ± SEMs (n = 9 for L. plantarum and BCG stimulation; n = 6 for PPD stimulation). *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01. In panel B, each symbol represents one blood donor; the lines illustrate how individual donors responded to the various stimuli.

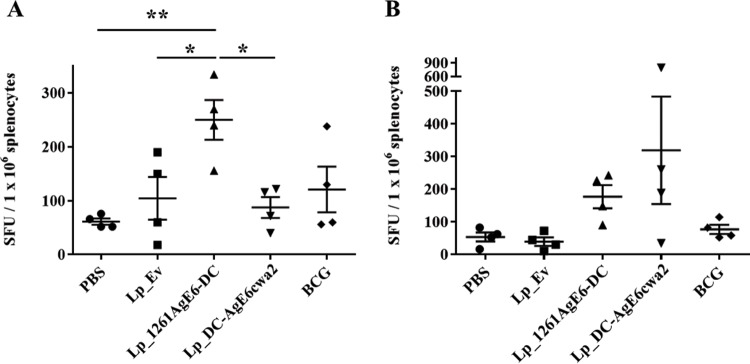

Antigen-specific IFN-γ production by splenocytes from immunized mice.

Mice were immunized by either intranasal or oral administration of the L. plantarum strains producing surface-displayed AgE6, Lp_1261AgE6-DC and Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2. Mice that were administered PBS and Lp_Ev were used as negative controls. A BCG-immunized group was also included.

A Th1 response, particularly the antigen-specific production of IFN-γ by memory cells, is thought to be crucial in protecting against M. tuberculosis infection (15). Therefore, we investigated the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes from immunized mice by enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays after in vitro restimulation with purified recombinant AgE6 (rAgE6) (Fig. 5). Oral vaccination with Lp_1261AgE6-DC resulted in a significantly higher frequency of AgE6-specific IFN-γ-secreting spleen cells than that seen with PBS and Lp_Ev, whereas oral vaccination with Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 did not increase the number of IFN-γ secretors compared with that in the negative-control groups (Fig. 5A). Intranasal immunization increased the numbers of AgE6-specific cytokine-producing splenocytes for both AgE6-producing strains, but the differences relative to the negative control were not statistically significant (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, splenocytes from mice immunized with BCG did not show elevated production of IFN-γ after stimulation with rAgE6 (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG 5.

Frequency of IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes isolated from mice immunized via the oral (A) or the nasal (B) route. Splenocytes were purified and incubated with the purified AgE6 protein for 36 to 48 h. IFN-γ-secreting cells were enumerated by ELISPOT. Results are presented as spot-forming units (SFU) per number of stimulated splenocytes. Each point represents one mouse and an average of technical duplicates; the overall results per group are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 4). *, P <0.05; **, P < 0.01.

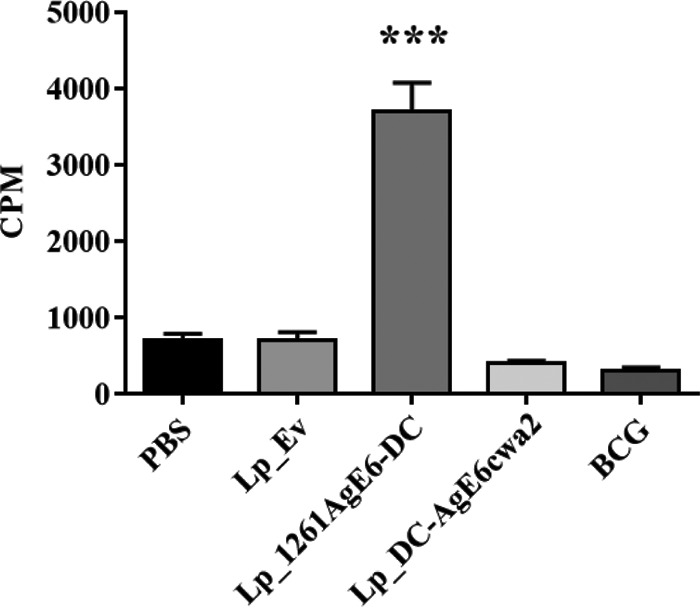

Antigen-specific PBMC proliferative responses from intranasally immunized mice.

Antigen-mediated PBMC responses from intranasally immunized mice were measured by the thymidine incorporation assay. Due to low yields of PMBCs isolated from individual mice, freshly isolated cells within each group were pooled (4 mice per group). The results (Fig. 6) showed that the rAgE6-induced proliferation of PBMCs from Lp_1261AgE6-DC-vaccinated mice was significantly higher than for all other groups. Notably, we did not observe increased proliferation for the Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 and BCG groups (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Proliferation of PBMCs isolated from mice immunized via the intranasal route. PBMCs from individual mice were purified and pooled within each group (4 mice per group); 1 × 105 PBMCs for each group were incubated with rAgE6 for 7 days. PMBC proliferation was measured using the thymidine incorporation assay. Results are presented as counts per minute (CPM). Bars represent means of triplicate values ± SEMs. ***, P <0.001.

We were unable to carry out a similar experiment for orally immunized mice, because the amount of PBMCs was not sufficient to set up the proliferation assay.

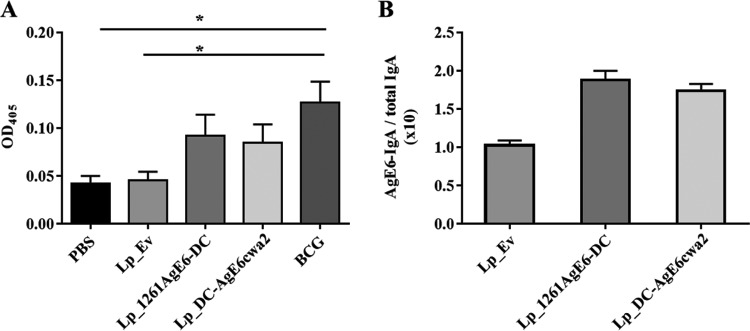

Antigen-specific IgA secretion in mucosal sites of orally immunized mice.

Secretory IgAs play a crucial role in immune defense at mucosal surfaces. To investigate the mucosal immune response induced by oral immunization with AgE6-displaying L. plantarum, we determined the levels of antigen-specific IgA in feces using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Figure 7A shows increased levels of IgA in fecal samples from mice immunized with Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2, Lp_1261AgE6-DC, or BCG compared with the levels in the control groups. Additionally, we measured total IgA in fecal samples from groups immunized with L. plantarum-based vaccines (Lp_Ev, Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2, and Lp_1261AgE6-DC), enabling normalization of AgE6-specific IgA levels to total IgA levels. No differences in total IgA levels were detected (data not shown); consequently, the normalized data (Fig. 7B) show trends similar to those of the nonnormalized data, i.e., a higher level of production of AgE6-specific IgA in mice administered the AgE6-displaying strains.

FIG 7.

Antigen-specific IgA antibodies detected after oral immunization by ELISA. Fecal samples were collected from mice on the termination day and pooled within each group (4 mice per group). (A) Detection of antigen-specific IgA in the different groups using recombinant AgE6 protein. The results are presented as means of at least three independent measurements of OD405 ± SEMs. *, P <0.05. (B) Values for groups immunized with Lp_Ev, Lp_1261AgE-DC, or Lp_DC-AgEcwa2 after normalization by total IgA (based on the OD values). The results represent the ratios of antigen-specific IgA versus total IgA and are presented as a mean of duplicates ± SEMs.

DISCUSSION

In the last 25 years, LAB have been widely used for the production of heterologous proteins, including antigens from pathogenic bacteria. LAB are promising candidates for vaccine delivery, since they interact with mucosal surfaces and may have adjuvant properties. In this study, we engineered L. plantarum bacteria for surface display of antigens derived from M. tuberculosis to investigate the potential of surface-located TB-antigens for inducing immune responses in mice. The model LAB, Lactococcus lactis, has already been exploited as a potential delivery vector for a mucosal DNA vaccine against TB and one of the engineered Lactococcus strains was shown to induce a Th1-cell immune response in mice (41). In our work, we selected L. plantarum due to the stronger immunomodulatory properties of this species (42), and we focused on protein rather than on gene delivery.

Previous studies have shown that surface display of heterologous proteins on Lactobacillus using various anchoring methods leads to varying levels of functionality in vitro and in vivo (37, 39, 40, 43). The N-terminal lipoprotein anchor used in this study has previously been used for functional display of invasin from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (37) and a CCL3 chemokine (39), whereas the C-terminal cell wall anchor has been exploited for functional display of cancer antigens (34, 44) and an anti-DEC-205 antibody (40).

Flow cytometry (Fig. 3A) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B) confirmed the surface localization of AgE6 in both strains. The results from the human lymphocyte proliferation assay demonstrate that the surface-located hybrid M. tuberculosis antigen was recognized by memory T cells of TB-positive donors in vitro (Fig. 4). In this in vitro test system, we did not observe significant differences between the two AgE6-expressing strains.

For the evaluation of Lp_1261AgE6-DC and Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 as potential TB vaccines in mice, we selected two administration routes, namely oral and nasal. M. tuberculosis uses the mucosa of the respiratory tract for invasion, and targeting of antigens to the respiratory tract via intranasal injection or inhalation is a commonly explored strategy in TB vaccine development (45–47). On the other hand, when it comes to L. plantarum, the oral route is of interest, because this food-grade bacterium is a natural resident of the intestinal microflora (48, 49). Mucosal immunization is potentially highly advantageous in vaccinology since the majority of pathogens enter the body via mucosal surfaces and it has been established that mucosal vaccination generates both mucosal and systemic immune protection (47, 50).

IFN-γ production by Th1 cells is central in controlling TB, because this proinflammatory cytokine activates macrophages, which are a target for M. tuberculosis infection (51, 52). We observed a significantly increased AgE6-specific IFN-γ response in spleen cells isolated from mice immunized orally with Lp_1261AgE6-DC (Fig. 5A), suggesting a specific systemic reaction in response to the AgE6 delivered by this strain. It was shown previously that oral vaccination with M. tuberculosis antigens leads to detectable mucosal and systemic immune responses (53–55) and even induces protective immunity in the lungs of mice and guinea pigs (54, 55). The lack of an increase in IFN-γ production by AgE6-stimulated splenocytes from BCG-vaccinated mice may be due to the fact that BCG does not contain ESAT-6 (56). In contrast to what was observed for mice orally immunized with lipoprotein-anchored AgE6, the number of IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes did not increase in mice that had been orally immunized with Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2. Importantly, antigens coupled with the cell wall anchor (cwa2) are located on the most external part of the bacterial cells, whereas in the case of lipoprotein anchoring (Lp_1261), the displayed proteins are likely to be more embedded in the cell wall. This difference may cause the cell wall-anchored AgE6 protein to be more prone to digestive activity in the gastrointestinal tract, which may reduce its efficacy in oral immunization. It is also possible that the difference between the strains is due to, or augmented by, different levels of surface-displayed antigens (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, upon nasal administration, we observed an increased frequency of IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes for groups immunized with either of the two AgE6-producing L. plantarum strains (Fig. 5B). However, in this case, due to the rather large variability among the individual mice, we were not able to obtain statistical significance.

In vitro stimulation of PBMCs isolated from intranasally immunized animals showed that cells from mice immunized with Lp_1261AgE6-DC proliferated to a significantly higher degree than each of the other groups (Fig. 6). There is no obvious explanation for our observation that the antigen-specific IFN-γ response generated in the spleen of mice intranasally immunized with Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 was not reflected in the PBMC proliferation assay. However, such apparent inconsistencies are not unique, since previous studies have found that T-cell proliferation does not necessarily correlate with IFN-γ production by memory cells (57, 58).

IgA antibodies are a major component of humoral immunity at mucosal sites and play a crucial role in neutralizing pathogens (59, 60). Recent studies in animal models have found that antigen delivery by orally administered L. plantarum may elicit secretion of specific IgA antibodies against antigens related to influenza (61), cancer (44), foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) (62), and classical swine fever virus (63). In this regard, we investigated whether orally administered AgE6-displaying L. plantarum induced production of AgE6-specific IgA antibodies at intestinal mucosa. The results for the Lp_1261AgE6-DC and Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 groups indicated that both strains elicited secretion of antigen-specific IgAs, but the elevation of the IgA levels was not statistically significant relative to those of the negative controls. The secretion of specific IgA antibodies was significantly increased in mice immunized with BCG relative to that in the negative controls (Fig. 7), suggesting successful induction of a mucosal antibody response to the Ag85B antigen in BCG.

To summarize, the results show that both AgE6-displaying L. plantarum strains elicit specific immune responses after intranasal and oral administrations. Lp_1261AgE6-DC seemed to be a stronger inducer of immunity regardless of the administration route. One possible explanation may simply be that there was a higher level of production of antigen (both total and surface located), meaning that higher doses of antigen were used when applying this strain for immunization. Better control and improved production of antigens in the bacterial cells might be one way to obtain stronger responses. Nevertheless, the results represent an encouraging step in the development of L. plantarum as a carrier for TB antigens. The system explored here provides noninvasive mucosal immunization and benefits from the safe status and likely the natural immune-modulating properties of L. plantarum. Notably, there are clear roads to further improve the system, such as coexpression and coadministration of adjuvants, exploration of other antigens, and coexpression of multiple antigens.

In conclusion, the present study shows that L. plantarum produces the hybrid Ag85B-ESAT-6 antigen (AgE6) and displays it on the bacterial surface using two different anchors. In vitro experiments demonstrate that blood cells from TB-positive patients proliferate in response to AgE6 antigens produced by L. plantarum. In vivo analyses show that both vaccine candidates induce antigen-specific immune responses after oral or nasal immunization. This study suggests that L. plantarum may have potential as a vector for delivering M. tuberculosis antigens to mucosal sites, which may be a new approach in future TB vaccine development. Additional modifications and improvements, including adjuvant strategies, are possible and should be studied to improve this microbial delivery system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Lactobacillus plantarum strains were cultured in MRS broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) at 37°C without shaking. Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid) at 37°C with shaking. Erythromycin was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml for L. plantarum. For E. coli, final concentrations of erythromycin and ampicillin were 200 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively. Liquid medium was solidified by adding 1.5% (wt/vol) agar.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC-AgE6 | Ampr, pUC57 vector with synthetic Ag85B–ESAT-6 gene | GenScript |

| pBAD/HisB-EF | Ampr, pBAD/HisB (Invitrogen) derivative, containing the gene encoding EfEndo18A | 69 |

| pBAD-AgE6 | Ampr; pBAD/HisB-EF derivative, where the gene sequence encoding the EfEndo18A protein was replaced by a fragment encoding the AgE6 fusion antigen | This study |

| pEV | Eryr, control plasmid (“empty vector”) | 37 |

| pLp_1261Inv | Eryr, pLp_2588AmyA (66) derivative, encoding a lipoprotein anchor sequence from Lp_1261 fused to an inv gene fragment | 37 |

| pLp_3050NucA | Eryr, pSIP401 (64) derivative, encoding the signal peptide sequence from Lp_3050 fused to the nucA gene | 67 |

| pSip_AgE6 | Eryr, pLp_3050NucA derivative, where the gene sequence encoding the Lp_3050NucA protein was replaced by the gene sequence encoding the AgE6 fusion antigen | This study |

| pLp_0373OFAcwa2 | Eryr, pLp_0373Nuc derivative, encodes the signal peptide sequence from Lp_0373 fused to the ofa gene and a subsequent cell wall anchor-encoding sequence (cwa2) | 34 |

| pLp_0373AgE6cwa2 | Eryr, pLp_0373OFAcwa2 derivative, where the ofa gene fragment was replaced by a fragment encoding the AgE6 fusion antigen | This study |

| pLp_1261AgE6 | Eryr, pLp_1261Inv derivative, where the inv gene fragment was replaced by a fragment encoding the AgE6 fusion antigen | This study |

| pLp_1261AgE6-DC | Eryr, pLp_1261AgE6 derivative, encodes the AgE6 antigen with a DC-binding peptide fused to its C terminus | This study |

| pLp_3050AgE6cwa2 | Eryr, pLp_0373OFAcwa2 derivative, where the ofa gene was replaced by a gene encoding the AgE6 fusion antigen and the Lp_0373 signal sequence was replaced by the Lp_3050 signal sequence | This study |

| pLp_3050DC-AgE6cwa2 | Eryr, pLp_3050Ag8E6cwa2 derivative, where a DC-binding peptide was inserted between the Lp_3050 signal sequence and the N terminus of the AgE6 antigen | This study |

| Strains | ||

| L. plantarum WCFS1 | Host strain | 79 |

| E. coli TOP10 | Host strain | Invitrogen |

| Lp_1261AgE6-DC | L. plantarum WCFS1 harboring pLp_1261AgE6-DC, for surface display of the AgE6 fusion antigen using an N-terminal covalent lipoprotein anchor | This study |

| Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 | L. plantarum WCFS1 carrying pLp_3050DC-AgE6cwa2, for surface display of the AgE6 fusion antigen using a C-terminal covalent cell wall anchor (cwa2) | This study |

| Lp_Ev | L. plantarum WCFS1 carrying pEv (empty vector), used as a negative-control strain | 37 |

EfEndo18A, Enterococcus faecalis endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase 18A.

DNA manipulations and plasmid construction.

The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2, and the basic outline of the constructed expression vectors is shown in Fig. 1. All plasmids used in this study for expression in Lactobacillus spp. are derivatives of the modular pSIP400 vector series, constructed and developed for inducible gene expression, secretion, and surface anchoring of proteins (34, 64–67). Plasmids pLp_0373OFAcwa2 (34), pLp_1261Inv (37), and pLp_3050NucA (67) were used as starting points. The Ag85B–ESAT-6 gene fragment was designed so that the predicted signal sequence of Ag85B (68) was removed and the C-terminal end of the Ag85B antigen was fused to the ESAT-6 antigen. A three-amino-acid linker encoding Gly-Thr-Ala and containing a KpnI restriction site was introduced between the two antigens for their easy exchange in the future. The Ag85B–ESAT-6 gene fragment encoding the Ag85B–ESAT-6 fusion (AgE6) was optimized for expression in L. plantarum, synthesized at GenScript (Piscataway, NJ), and cloned into a pUC57 plasmid, yielding pUC-AgE6. The gene fragment encoding AgE6 was amplified from pUC-AgE6 using the AgMluR and AgSalIF primers. The PCR fragment was directly cloned into the PCR-Blunt TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and the resulting plasmid was digested by SalI and MluI. The resulting 1.2-kb AgE6-encoding fragment was cloned into SalI/MluI-digested pLp_0373OFAcwa2 (34), yielding pLp_0373AgE6cwa2. To exchange the Lp_0373 signal peptide with the Lp_3050 signal peptide, the pLp_0373AgE6cwa2 plasmid was digested with SalI and HindIII and the 1.8-kb gene fragment encoding AgE6cwa2 was ligated into SalI/HindIII-digested pLp_3050NucA (67), yielding pLp_3050AgE6cwa2. A gene fragment encoding a 12-residue-long DC-binding sequence (FYPSYHSTPQRP) (35, 36) was fused to the 5′ end of the antigen-encoding gene fragment by overlap extension-PCR in three subsequent PCRs. In the first step, the DNA fragment was amplified from pLp_3050AgE6cwa2 using primer pair P1-DCF/AgMluR. The PCR product was used as a template in the next PCR with primers P2-DCF and AgMluR. Subsequently, the PCR product was used as a template in the next amplification reaction with primer pair P3-DCF/AgMluR. The final PCR fragment was subcloned into the PCR-Blunt TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and the resulting plasmid was digested with SalI and MluI. The resulting 1.2-kb fragment encoding DC-AgE6 was cloned into SalI/MluI-digested pLp_3050AgE6cwa2, yielding the final expression vector, pLp_3050DC-AgE6cwa2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| AgMluR | CCTTAACGCGTTGCAAACATGCCGGT |

| AgSalI | GTCGACTTTAGTCGTCCAGGTTTGCC |

| P1-DCF | CGCCACAACGGCCATTTAGTCGTCCAGGTTT |

| P2-DCF | CCAAGTTATCATAGTACGCCACAACGGCCATTTAGT |

| P3-DCF | GTCGACTTTTATCCAAGTTATCATAGTACGCCAC |

| pAgESAT-CytF | CATATGTTTAGTCGTCCAGGTTTGC |

| pAgESAT-CytR | GGAAACAGCTATGACCATGATTAC |

| SekF | GGCTTTTATAATATGAGATAATGCCGAC |

| DC-E6R | CTATGATAACTTGGATAAAATGCAAACATGCCGGTAAC |

| E6-DCF | GTTACCGGCATGTTTGCATTTTATCCAAGTTATCATAGTACGCC |

| Hind-DCR | TTGAAGCTTTTATGGCCGTTGTGGCGT |

| pBAD_AG_F | TCATCATCACAGATCTTTTAGTCGTCCAGGTTTGCC |

| pBAD_AG_R | CAAAACAGCCAAGCTTTTATGCAAACATGCCGGT |

Italic font indicates restriction sites; bold font indicates parts of the DC-binding peptide; underlining indicates 15-bp extensions that are complementary to the ends of the BglII/HindIII-digested pBAD vector (such overlapping sequences are necessary when using in-fusion cloning).

To construct the vector with a lipoprotein anchor, the sequence encoding AgE6 was amplified from pUC-AgE6 using the pAgESAT-CytF and pAgESAT-CytR primers. The 1.2-kb PCR fragment was subcloned into the PCR-Blunt TOPO vector, and the resulting plasmid was digested with NdeI and HindIII. The fragment encoding AgE6 was cloned into NdeI/HindIII-digested pLp_3050NucA, yielding pSip_AgE6. Subsequently, the pSip_AgE6 plasmid was digested with SalI and HindIII, and the fragment encoding AgE6 was ligated to pLp_1261Inv (37) digested with the same enzymes, resulting in pLp_1261AgE6. The gene fragment encoding Lp_1261AgE6 was then amplified using the SekF and DC-E6R primers and pLp_1261AgE6 as the template, whereas a 36-bp DNA fragment encoding the DC-binding sequence was amplified using the E6-DCF and Hind-DCR primers and pLp_DC-AgE6cwa2 as a template. The products of these two PCRs, with 38-bp overlapping fragments, were fused in a subsequent overlap extension-PCR using the outer primer pair SekF and Hind-DCR. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with SalI and HindIII and cloned into SalI/HindIII-digested pLp_1261AgE6, yielding pLp_1261AgE6-DC.

To make a plasmid for overexpressing and purifying the recombinant fusion protein, the sequence encoding AgE6 was amplified from pUC-AgE6 using the pBAD_AG_F and pBAD_AG_R primers and inserted into BglII/HindIII-digested pBAD/HisB-EF (69) using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA), yielding the plasmid pBAD-AgE6. This expression plasmid encodes AgE6 fused to an N-terminal His tag.

All plasmids were first transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells. Positive clones were screened by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion, after which the PCR-amplified fragments were verified by sequencing. Plasmids pLp_1261AgE6-DC and pLp_DC-AgE6cwa2 were purified using a PureYield plasmid miniprep system (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and electroporated into L. plantarum cells according to the method of Aukrust et al. (70).

Overexpression and purification of rAgE6 protein.

An overnight culture of E. coli harboring pBAD-AgE6 was diluted to achieve an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.1 in fresh Terrific broth medium, prepared according to the method of Tartof and Hobbs (71) and supplemented with ampicillin. The culture was incubated at 37°C until the OD600 reached ∼0.6, using a Harbinger Biotechnology Lex-48 bioreactor system (Biofrontier Technology Pte Ltd., Singapore) following the manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression was then induced by adding arabinose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to a final concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol). Bacterial cells were harvested after 24 h by centrifugation at 6,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The pellet was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −20°C until purification. Inclusion bodies containing rAgE6 were recovered from bacterial cells, and the protein was refolded according essentially to methods described previously (72, 73). Cells harvested from a 500-ml culture were resuspended in 20 ml washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% deoxycholic acid, pH 8.0) with 20 μl lysozyme (100 mg/ml), and the bacteria were sonicated for 20 min on ice using a Sonics Vibracell (30% amplitude, 5 s on/off). Insoluble material was collected by centrifugation at 2,500 × g and 4°C for 10 min and washed three times with 20 ml washing buffer. Inclusion bodies were then solubilized in 25 to 30 ml of buffer A1 (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) at room temperature, and the remaining insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 12,500 × g and 4°C for 15 min. Solubilized rAgE was purified using Protino Ni-NTA agarose (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG). The protein was washed 5 times in the column by alternating between washing buffer 1 (3 M urea, 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0) and washing buffer 2 (3 M urea, 60% isopropanol, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) before eluting with buffer B1 (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Fractions containing rAgE were dialyzed against dialysis buffer 1 (3 M urea, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) using SnakeSkin dialysis tubing (10-kDa molecular mass cutoff; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Dialyzed protein was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap QFF 5-ml column (GE Healthcare), using the dialysis buffer as the starting buffer. The protein was eluted by applying a linear gradient of 0 to 50% buffer B2 (3 M urea, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 8.5) for 40 min at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. Fractions containing rAgE6 were pooled and dialyzed against dialyzing buffer 2 (20 mM glycine, pH 9.2) at 4°C for 24 h. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford microassay (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA).

Harvesting of recombinant L. plantarum strains.

Overnight cultures of L. plantarum strains were diluted in fresh MRS medium to an OD600 of ∼0.1 and incubated at 37°C until the OD600 reached ∼0.3. AgE6 expression was then induced by adding the IP-673 peptide pheromone (Caslo, Lyngby, Denmark) to a final concentration of 25 ng/ml (38). The bacterial cells were harvested 3 h after induction by centrifugation at 5,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. Pellets were washed twice with PBS before use in subsequent experiments. To determine the number of CFU, harvested bacterial cells were cultivated on solid MRS medium supplemented with antibiotics for 48 h and the colonies were counted.

Crude cell-free protein extract preparation.

Bacterial cells from a 50-ml culture containing 1 × 109 CFU/ml of L. plantarum were harvested 3 h after induction (as described above) and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. Cell-free protein extracts were prepared by disrupting cells in FastPrep tubes containing 1.5 g of glass beads (size ≤106 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) using a FastPrep FP120 cell disrupter with a shaking speed of 6.5 m/s for 45 s. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g and 4°C for 2 min.

Western blot analysis.

To analyze AgE6 expression in L. plantarum, protein extracts (prepared as described above) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 10% Mini-Protean TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the iBlot dry-blotting system (Invitrogen). The proteins were detected with the SNAP i.d. 2.0 protein detection system (Merck kGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) using a specific monoclonal mouse anti-ESAT-6 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) diluted 1:15,000 and subsequently a polyclonal horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Dako, Denmark A/S) diluted 1:7,500.

Dot blot analysis.

To evaluate the amount of AgE6 antigen on the bacterial surface and to compare this with the AgE6 fraction in the total protein extract, bacteria were harvested 3 h after induction and protein extracts were prepared as described above. A cell suspension with 1 × 109 CFU/ml of recombinant L. plantarum (surface-located AgE6) and a protein extract from the same amount of cells (total AgE6) were diluted 5-fold, after which series of 2-fold serial dilutions were prepared. A 2-μl volume of each dilution was applied to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was then blocked with 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich) in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TTBS) buffer (0.1% [vol/wt] Tween 20, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature. The AgE6 proteins were detected by incubating for 1 h with monoclonal mouse anti-ESAT-6 antibodies and then incubating 1 h with polyclonal HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG.

Flow cytometry and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of L. plantarum expressing AgE6.

Bacterial cells were harvested as described above. Approximately 1 × 109 CFU was resuspended in 50 μl PBS containing 2% BSA and 0.4 μl monoclonal mouse anti-ESAT-6 antibody and then incubated for 30 min on ice. After incubation, cells were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min and washed 4 times with PBS containing 2% BSA at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in 50 μl PBS containing 2% BSA and 0.8 μl polyclonal rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) and then incubated on ice in the dark for 30 min. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed 4 times with PBS, and resuspended in 100 μl PBS without BSA at 4°C. The resulting bacterial suspensions were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using a MACSQuant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, bacteria were visualized under an Axio Observer.z1 microscope (Zeiss, Germany), and the fluorescence was acquired at excitation wavelengths of 450 to 490 nm and emission wavelengths of 500 to 590 nm.

Isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Tuberculosis-positive patients were diagnosed using the interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) for tuberculosis (74) at Østfold Hospital Trust (SiØ) in Kalnes, Norway. Blood was collected from TB-positive volunteers after they signed a consent form approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK). Human PBMCs were isolated and handled according to institutional ethical guidelines (Østfold Hospital Trust, Norway). Cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation for 25 min at 1,500 × g using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield Diagnostics Ltd., Dundee, Scotland) at room temperature. The PBMCs were washed four times with PBS to remove the platelets. The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS; PAA Cell Culture Company, BioPath Stores, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Human lymphocyte proliferation assay.

T-cell proliferation was measured using the thymidine incorporation assay. Briefly, 1 × 105 freshly isolated PBMCs were seeded in triplicate into the wells of 96-well plates. Recombinant L. plantarum cells were prepared as described above. Next, 1 × 107 CFU quantities of L. plantarum strains were inactivated by UV irradiation for 45 min, washed with PBS, resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and then added to the PBMCs. As controls, PBMCs were stimulated with 50 ng/ml purified protein derivative (PPD; Statens Serum Institut, Denmark) or 0.75 × 105 to 3 × 105 BCG bacteria (InterVax Ltd., Toronto, Canada). Nonstimulated PBMCs were used as a negative control. The cells were incubated with stimuli for 8 to 10 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. At 24 h before harvesting, the cells were pulsed with 20 μl 0.5 μCi [methyl-3H]thymidine (PerkinElmer Inc., Australia) in RPMI 1640 (supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin). Cells were harvested using a Packard Filtermate 196 cell harvester (Canberra Packard, Mt. Waverly, VIC, Australia) with glass fiber filters (PerkinElmer) and analyzed using a TopCount NXT microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Immunization protocol.

All animal experiments were approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority (Mattilsynet, Norway). Female 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 BomTac mice were purchased from Taconic Bioscience (Ejby, Denmark) via Folkehelseinstituttet (Oslo, Norway). Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated cages (Innovive Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) under standard conditions (12 h light/dark cycle, 23 to 25°C, 45 to 50% relative humidity). Water and the standard diet (RM1; SDS Special Diet Services, Whitham, United Kingdom) were given ad libitum for the duration of the study. Mice were divided into 10 groups (n = 4 each), and two administration routes were applied: oral (5 groups) and intranasal (5 groups). All experimental groups are listed and described in Table 3. L. plantarum cells were prepared as described above. Bacterial cultures were harvested 3 to 6 days before each immunization, and the washed cells were stored at −20°C. Subsamples of the harvested cells were used to determine the CFU and to carry out flow cytometry for confirming the proper expression and surface location of the antigens. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBS on the day of administration. The immunization protocol was established based on published data (e.g., see references 75, to ,78). For intranasal immunization, mice were administered 20 μl PBS (negative control) or PBS containing 1 × 109 CFU L. plantarum or 0.3 × 105 to 1.2 × 105 BCG bacteria at days 1, 2, 12, 14, 25, and 26. For oral immunization, mice were administered 100 μl PBS (negative control) or PBS containing 1 × 109 CFU L. plantarum or 0.3 × 105 to 1.2 × 105 BCG bacteria at days 1, 2, 3, 13, 14, 15, 25, 26, and 27. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia at day 38 for intranasal immunization and at day 40 for oral immunization.

TABLE 3.

Experimental groups used for oral and intranasal immunization of mice

| Vaccine | Experimental group |

|---|---|

| PBS | Negative-control group, mice immunized with PBS |

| Lp_Ev | Negative-control group, mice immunized with L. plantarum not expressing the AgE6 antigen |

| Lp_1261AgE6-DC | Mice immunized with L. plantarum producing AgE6 with an N-terminal lipoprotein anchor and DC-targeting peptide |

| Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2 | Mice immunized with L. plantarum producing AgE6 with a C-terminal cell wall anchor and DC-targeting peptide |

| BCG | Control group, mice immunized with BCG |

Isolation of mouse PBMCs.

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture from mice anesthetized with a mixture of zolazepam (75 mg/kg of body weight), tiletamine (75 mg/kg of body weight), and xylazine (1.8 mg/kg of body weight). Blood was mixed with an equal volume of PBS, layered onto 3 ml of Histopaque-1077 solution (Sigma), and centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 min at room temperature. Mononuclear cells were collected and washed 3 times with PBS by centrifuging at 250 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The yields of PBMCs from mice immunized intranasally were in the ranges of 4 × 105 to 54 × 105 cells/ml for PBS, 0.8 × 105 to 7.9 × 105 cells/ml for Lp_Ev, 0.5 × 105 to 4.8 × 105 cells/ml for Lp_1261AgE6-DC, 2.2 × 105 to 7.1 × 105 cells/ml for Lp_DC-AgE6cwa2, and 1.5 × 105 to 5.2 × 105 cells/ml for BCG groups; cells were pooled within each group (4 mice per group).

Isolation of splenocytes.

The spleens were collected, mashed through 100-μm Corning cell strainers (Sigma-Aldrich), and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The cell pellets were resuspended and incubated in red cell lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 min and washed two times with RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Feces.

On the day of termination, fecal samples were collected from individual mice vaccinated orally and pooled within each group (4 mice per group). Feces were resuspended at a concentration of 100 mg/ml in PBS containing protease inhibitors (cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), homogenized mechanically by vortexing, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −20°C until analysis.

IFN-γ secretion by splenocytes.

The frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells was determined by ELISPOT assay according to the supplier's instructions (Mabtech AB, Nacka Strand, Sweden). Briefly, 2.5 × 105 cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of purified rAgE6 in duplicate for 36 to 48 h. The frequency of cytokine-secreting cells was measured using the CTL-ImmunoSpot S6 microanalyzer (CTL-Europe GmbH, Bonn, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unstimulated lymphocytes were used as a negative control.

Mouse lymphocyte proliferation assay.

The proliferation of PBMCs purified from mice immunized via the intranasal route was measured by the thymidine incorporation assay as described above. Briefly, 1 × 105 freshly isolated cells were seeded in the wells of 96-well plates. The cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml rAgE6 in triplicates. The PBMCs were incubated with stimuli for 7 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Unstimulated lymphocytes were used as a negative control.

IgA antibody assay.

IgA antibodies in fecal samples were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Microtiter plates were coated with 10 μg/ml rAgE6 for antigen-specific IgA and with 1 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgA (Sigma) for total IgA detection and incubated overnight at room temperature. Supernatants from the fecal samples were diluted 1.5-fold for AgE6-specific IgA and 1:100 for total IgA in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA and then incubated in the precoated microtiter plate overnight at 4°C (100 μl per well). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA (Sigma) was used for color development. The OD at 405 nm, with the reference wavelength set to 650 nm, was measured using a Sunrise plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland).

Statistical tests.

Statistical significance was determined by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with Tukey's post hoc tests using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Results are presented as means ± the standard errors of the means (SEM).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Øystein Almås and Åse-Berit Mathisen at the Østfold Hospital Trust (SiØ) in Kalnes, Norway, for cooperating and providing blood from TB-positive patients, Inger Øynebråten at OUH for help with ELISPOT assays, Claus Aagaard and Frank Follman at SSI for technical discussions related to the purification of the antigen, and Ewa Piskorz for technical assistance during animal experiments.

This work was funded by a Ph.D. fellowship from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences to Katarzyna Kuczkowska and by grants 196363 and 234502 from the Globvac program of the Research Council of Norway.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lerm M, Netea MG. 2016. Trained immunity: a new avenue for tuberculosis vaccine development. J Intern Med 279:1–15. doi: 10.1111/joim.12449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. 2015. Global tuberculosis report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufmann SH. 2010. Novel tuberculosis vaccination strategies based on understanding the immune response. J Intern Med 267:337–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Costa C, Walker B, Bonavia A. 2015. Tuberculosis vaccines—state of the art, and novel approaches to vaccine development. Int J Infect Dis 32:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parida SK, Kaufmann SH. 2010. Novel tuberculosis vaccines on the horizon. Curr Opin Immunol 22:374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan MJ, Thole J. 2012. Tuberculosis vaccines: a strategic blueprint for the next decade. Tuberculosis 92:S6–S13. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armitige LY, Jagannath C, Wanger AR, Norris SJ. 2000. Disruption of the genes encoding antigen 85A and antigen 85B of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: effect on growth in culture and in macrophages. Infect Immun 68:767–778. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.2.767-778.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denis O, Lozes E, Huygen K. 1997. Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses against culture filtrate antigens in Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin-infected mice. Infect Immun 65:676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich J, Weldingh K, Andersen P. 2006. Prospects for a novel vaccine against tuberculosis. Vet Microbiol 112:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okkels LM, Andersen P. 2004. Protein-protein interactions of proteins from the ESAT-6 family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 186:2487–2491. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2487-2491.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmood A, Srivastava S, Tripathi S, Ansari MA, Owais M, Arora A. 2011. Molecular characterization of secretory proteins Rv3619c and Rv3620c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEBS J 278:341–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agger EM Novel adjuvant formulations for delivery of anti-tuberculosis vaccine candidates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 102:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen P, Urdahl KB. 2015. TB vaccines; promoting rapid and durable protection in the lung. Curr Opin Immunol 35:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst JD. 2012. The immunological life cycle of tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol 12:581–591. doi: 10.1038/nri3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ottenhoff THM, Kaufmann SHE. 2012. Vaccines against tuberculosis: where are we and where do we need to go? PLoS Pathog 8:e1002607. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina E, Guzmán CA. 2001. Use of live bacterial vaccine vectors for antigen delivery: potential and limitations. Vaccine 19:1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena M, Van TTH, Baird FJ, Coloe PJ, Smooker PM. 2013. Pre-existing immunity against vaccine vectors–friend or foe? Microbiology 159:1–11. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049601-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths KL, Khader SA. 2014. Novel vaccine approaches for protection against intracellular pathogens. Curr Opin Immunol 28:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeBlanc JG, Aubry C, Cortes-Perez NG, de Moreno de LeBlanc A, Vergnolle N, Langella P, Azevedo V, Chatel JM, Miyoshi A, Bermudez-Humaran LG. 2013. Mucosal targeting of therapeutic molecules using genetically modified lactic acid bacteria: an update. FEMS Microbiol Lett 344:1–9. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michon C, Langella P, Eijsink VGH, Mathiesen G, Chatel JM. 2016. Display of recombinant proteins at the surface of lactic acid bacteria: strategies and applications. Microb Cell Fact 15:70. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juárez-Rodríguez MD, Yang J, Kader R, Alamuri P, Curtiss R III, Clark-Curtiss JE. 2012. Live attenuated Salmonella vaccines displaying regulated delayed lysis and delayed antigen synthesis to confer protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 80:815–831. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05526-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parida SK, Huygen K, Ryffel B, Chakraborty T. 2005. Novel bacterial delivery system with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium carrying plasmid encoding Mtb antigen 85A for mucosal immunization: establishment of proof of principle in TB mouse model. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1056:366–378. doi: 10.1196/annals.1352.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daifalla N, Cayabyab MJ, Xie E, Kim HB, Tzipori S, Stashenko P, Duncan M, Campos-Neto A. 2015. Commensal Streptococcus mitis is a unique vector for oral mucosal vaccination. Microbes Infect 17:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells JM, Mercenier A. 2008. Mucosal delivery of therapeutic and prophylactic molecules using lactic acid bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:349–362. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Kharrat P, Chatel J-M, Langella P. 2011. Lactococci and lactobacilli as mucosal delivery vectors for therapeutic proteins and DNA vaccines. Microb Cell Fact 10:S4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyszyńska A, Kobierecka P, Bardowski J, Jagusztyn-Krynicka E. 2015. Lactic acid bacteria—20 years exploring their potential as live vectors for mucosal vaccination. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:2967–2977. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarahomjoo S. 2012. Development of vaccine delivery vehicles based on lactic acid bacteria. Mol Biotechnol 51:183–199. doi: 10.1007/s12033-011-9450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosales-Mendoza S, Angulo C, Meza B. 2016. Food-grade organisms as vaccine biofactories and oral delivery vehicles. Trends Biotechnol 34:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohamadzadeh M, Olson S, Kalina WV, Ruthel G, Demmin GL, Warfield KL, Bavari S, Klaenhammer TR. 2005. Lactobacilli activate human dendritic cells that skew T cells toward T helper 1 polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2880–2885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500098102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijerink M, Van Hemert S, Taverne N, Wels M, De Vos P, Bron PA, Savelkoul HF, van Bilsen J, Kleerebezem M, Wells JM. 2010. Identification of genetic loci in Lactobacillus plantarum that modulate the immune response of dendritic cells using comparative genome hybridization. PLoS One 5:e10632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen HR, Frøkiær H, Pestka JJ. 2002. Lactobacilli differentially modulate expression of cytokines and maturation surface markers in murine dendritic cells. J Immunol 168:171–178. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloksma N, De Heer E, Van Dijk H, Willers J. 1979. Adjuvanticity of lactobacilli. I. Differential effects of viable and killed bacteria. Clin Exp Immunol 37:367–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bron PA, van Baarlen P, Kleerebezem M. 2011. Emerging molecular insights into the interaction between probiotics and the host intestinal mucosa. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:66–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fredriksen L, Mathiesen G, Sioud M, Eijsink VG. 2010. Cell wall anchoring of the 37-kilodalton oncofetal antigen by Lactobacillus plantarum for mucosal cancer vaccine delivery. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7359–7362. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohamadzadeh M, Duong T, Sandwick S, Hoover T, Klaenhammer T. 2009. Dendritic cell targeting of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen expressed by Lactobacillus acidophilus protects mice from lethal challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:4331–4336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900029106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curiel TJ, Morris C, Brumlik M, Landry SJ, Finstad K, Nelson A, Joshi V, Hawkins C, Alarez X, Lackner A. 2004. Peptides identified through phage display direct immunogenic antigen to dendritic cells. J Immunol 172:7425–7431. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fredriksen L, Kleiveland CR, Hult LTO, Lea T, Nygaard CS, Eijsink VG, Mathiesen G. 2012. Surface display of N-terminally anchored invasin by Lactobacillus plantarum activates NF-κB in monocytes. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5864–5871. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01227-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halbmayr E, Mathiesen G, Nguyen T-H, Maischberger T, Peterbauer CK, Eijsink VG, Haltrich D. 2008. High-level expression of recombinant β-galactosidases in Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus sakei using a sakacin P-based expression system. J Agric Food Chem 56:4710–4719. doi: 10.1021/jf073260+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuczkowska K, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VG, Oynebraten I. 2015. Lactobacillus plantarum displaying CCL3 chemokine in fusion with HIV-1 Gag derived antigen causes increased recruitment of T cells. Microb Cell Fact 14:169. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michon C, Kuczkowska K, Langella P, Eijsink VG, Mathiesen G, Chatel JM. 2015. Surface display of an anti-DEC-205 single chain Fv fragment in Lactobacillus plantarum increases internalization and plasmid transfer to dendritic cells in vitro and in vivo. Microb Cell Fact 14:95. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pereira VB, Saraiva TDL, Souza BM, Zurita-Turk M, Azevedo MSP, De Castro CP, Mancha-Agresti P, dos Santos JSC, Santos ACG, Faria AMC, Leclercq S, Azevedo V, Miyoshi A. 2015. Development of a new DNA vaccine based on mycobacterial ESAT-6 antigen delivered by recombinant invasive Lactococcus lactis FnBPA+. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:1817–1826. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells JM. 2011. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of lactobacilli. Microb Cell Fact 10:S17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kajikawa A, Nordone SK, Zhang L, Stoeker LL, LaVoy AS, Klaenhammer TR, Dean GA. 2011. Dissimilar properties of two recombinant Lactobacillus acidophilus strains displaying Salmonella FliC with different anchoring motifs. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:6587–6596. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05153-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mobergslien A, Vasovic V, Mathiesen G, Fredriksen L, Westby P, Eijsink VG, Peng Q, Sioud M. 2015. Recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum induces immune responses to cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1 and maturation of dendritic cells. Hum Vaccin Immunother 11:2664–2673. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1056952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Källenius G, Pawlowski A, Brandtzaeg P, Svenson S. 2007. Should a new tuberculosis vaccine be administered intranasally? Tuberculosis 87:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hokey DA, Misra A. 2011. Aerosol vaccines for tuberculosis: a fine line between protection and pathology. Tuberculosis 91:82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diogo GR, Reljic R. 2014. Development of a new tuberculosis vaccine: is there value in the mucosal approach? Immunotherapy 6:1001–1013. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siezen RJ, Francke C, Renckens B, Boekhorst J, Wels M, Kleerebezem M, van Hijum SA. 2012. Complete resequencing and reannotation of the Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 Genome. J Bacteriol 194:195–196. doi: 10.1128/JB.06275-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahrné S, Nobaek S, Jeppsson B, Adlerberth I, Wold AE, Molin G. 1998. The normal Lactobacillus flora of healthy human rectal and oral mucosa. J Appl Microbiol 85:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srivastava A, Gowda DV, Madhunapantula SV, Shinde CG, Iyer M. 2015. Mucosal vaccines: a paradigm shift in the development of mucosal adjuvants and delivery vehicles. APMIS 123:275–288. doi: 10.1111/apm.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyadova IV, Panteleev AV. 2015. Th1 and Th17 cells in tuberculosis: protection, pathology, and biomarkers. Mediators Inflamm 2015:854507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper AM, Khader SA. 2008. The role of cytokines in the initiation, expansion, and control of cellular immunity to tuberculosis. Immunol Rev 226:191–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ancelet LR, Aldwell FE, Rich FJ, Kirman JR. 2012. Oral vaccination with lipid-formulated BCG induces a long-lived, multifunctional CD4+ T cell memory immune response. PLoS One 7:e45888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doherty TM, Olsen AW, van Pinxteren L, Andersen P. 2002. Oral vaccination with subunit vaccines protects animals against aerosol infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 70:3111–3121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3111-3121.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hosseini M, Dobakhti F, Pakzad SR, Ajdary S. 2015. Immunization with single oral dose of alginate-encapsulated BCG elicits effective and long-lasting mucosal immune responses. Scand J Immunol 82:489–497. doi: 10.1111/sji.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brodin P, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2004. ESAT-6 proteins: protective antigens and virulence factors? Trends Microbiol 12:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laouar Y, Crispe IN. 2000. Functional flexibility in T cells: independent regulation of CD4+ T cell proliferation and effector function in vivo. Immunity 13:291–301. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anthony DD, Milkovich KA, Zhang W, Rodriguez B, Yonkers NL, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. 2012. Dissecting the T cell response: proliferation assays vs. cytokine signatures by ELISPOT. Cells 1:127–140. doi: 10.3390/cells1020127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogra PL. 2003. Mucosal immunity: some historical perspective on host-pathogen interactions and implications for mucosal vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol 81:23–33. doi: 10.1046/j.0818-9641.2002.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiong N, Hu S. 2015. Regulation of intestinal IgA responses. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:2645–2655. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi S-H, Yang W-T, Yang G-L, Cong Y-L, Huang H-B, Wang Q, Cai R-P, Ye L-P, Hu J-T, Zhou J-Y, Wang C-F, Li Y. 2014. Immunoprotection against influenza virus H9N2 by the oral administration of recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum NC8 expressing hemagglutinin in BALB/c mice. Virology 464-465:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang M, Pan L, Zhou P, Lv J, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang Y. 2015. Protection against foot-and-mouth disease virus in guinea pigs via oral administration of recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum expressing VP1. PLoS One 10:e0143750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu Y-G, Guan X-T, Liu Z-M, Tian C-Y, Cui L-C. 2015. Immunogenicity of recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum expressing classical swine fever virus E2 protein in conjunction with thymosin α-1 as an adjuvant in swine via oral administration. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3745–3752. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00127-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sørvig E, Grönqvist S, Naterstad K, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VGH, Axelsson L. 2003. Construction of vectors for inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and L. plantarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 229:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sørvig E, Mathiesen G, Naterstad K, Eijsink VG, Axelsson L. 2005. High-level, inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and Lactobacillus plantarum using versatile expression vectors. Microbiology 151:2439–2449. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mathiesen G, Sveen A, Piard JC, Axelsson L, Eijsink VGH. 2008. Heterologous protein secretion by Lactobacillus plantarum using homologous signal peptides. J Appl Microbiol 105:215–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mathiesen G, Sveen A, Brurberg M, Fredriksen L, Axelsson L, Eijsink V. 2009. Genome-wide analysis of signal peptide functionality in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. BMC Genomics 10:425. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinrich Olsen A, van Pinxteren LA, Meng Okkels L, Birk Rasmussen P, Andersen P. 2001. Protection of mice with a tuberculosis subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85b and esat-6. Infect Immun 69:2773–2778. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2773-2778.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bøhle LA, Mathiesen G, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Eijsink VG. 2011. An endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Enterococcus faecalis V583 responsible for the hydrolysis of high-mannose and hybrid-type N-linked glycans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 325:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aukrust TW, Brurberg MB, Nes IF. 1995. Transformation of Lactobacillus by electroporation. Methods Mol Biol 47:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tartof K, Hobbs C. 1987. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Bethesda Res Lab Focus 9:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aagaard C, Hoang T, Dietrich J, Cardona P-J, Izzo A, Dolganov G, Schoolnik GK, Cassidy JP, Billeskov R, Andersen P. 2011. A multistage tuberculosis vaccine that confers efficient protection before and after exposure. Nat Med 17:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nm.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Korsholm KS, Karlsson I, Tang ST, Brandt L, Agger EM, Aagaard C, Andersen P, Fomsgaard A. 2013. Broadening of the T-cell repertoire to HIV-1 Gag p24 by vaccination of HLA-A2/DR transgenic mice with overlapping peptides in the CAF05 adjuvant. PLoS One 8:e63575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clifford V, He Y, Zufferey C, Connell T, Curtis N. 2015. Interferon gamma release assays for monitoring the response to treatment for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 95:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corthésy B, Boris S, Isler P, Grangette C, Mercenier A. 2005. Oral immunization of mice with lactic acid bacteria producing Helicobacter pylori urease B subunit partially protects against challenge with Helicobacter felis. J Infect Dis 192:1441–1449. doi: 10.1086/444425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grangette C, Muller-Alouf H, Goudercourt D, Geoffroy MC, Turneer M, Mercenier A. 2001. Mucosal immune responses and protection against tetanus toxin after intranasal immunization with recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum. Infect Immun 69:1547–1553. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1547-1553.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hernani Mde L, Ferreira PC, Ferreira DM, Miyaji EN, Ho PL, Oliveira ML. 2011. Nasal immunization of mice with Lactobacillus casei expressing the pneumococcal surface protein C primes the immune system and decreases pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 62:263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reveneau N, Geoffroy MC, Locht C, Chagnaud P, Mercenier A. 2002. Comparison of the immune responses induced by local immunizations with recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum producing tetanus toxin fragment C in different cellular locations. Vaccine 20:1769–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kleerebezem M, Boekhorst J, van Kranenburg R, Molenaar D, Kuipers OP, Leer R, Tarchini R, Peters SA, Sandbrink HM, Fiers MW, Stiekema W, Lankhorst RM, Bron PA, Hoffer SM, Groot MN, Kerkhoven R, de Vries M, Ursing B, de Vos WM, Siezen RJ. 2003. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1990–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337704100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]