ABSTRACT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an important opportunistic human pathogen that lives in biofilm-like cell aggregates at sites of chronic infection, such as those that occur in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis and nonhealing ulcers. During growth in a biofilm, P. aeruginosa dramatically increases the production of filamentous Pf bacteriophage (Pf phage). Previous work indicated that when in vivo Pf phage production was inhibited, P. aeruginosa was less virulent. However, it is not clear how the production of abundant quantities of Pf phage similar to those produced by biofilms under in vitro conditions affects pathogenesis. Here, using a murine pneumonia model, we show that the production of biofilm-relevant amounts of Pf phage prevents the dissemination of P. aeruginosa from the lung. Furthermore, filamentous phage promoted bacterial adhesion to mucin and inhibited bacterial invasion of airway epithelial cultures, suggesting that Pf phage traps P. aeruginosa within the lung. The in vivo production of Pf phage was also associated with reduced lung injury, reduced neutrophil recruitment, and lower cytokine levels. Additionally, when producing Pf phage, P. aeruginosa was less prone to phagocytosis by macrophages than bacteria not producing Pf phage. Collectively, these data suggest that filamentous Pf phage alters the progression of the inflammatory response and promotes phenotypes typically associated with chronic infection.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, bacteriophages, cystic fibrosis, dissemination, inflammation, lung infection, macrophages, neutrophils

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that often infects sites of nonresolving inflammation, such as chronic ulcers and the airways of people with cystic fibrosis (CF), as well as medical devices, such as catheters and endotracheal tubes (1–3). During chronic infection, P. aeruginosa forms biofilm-like aggregates (4). When studied in vitro, some of the most highly transcribed genes in P. aeruginosa biofilms belong to a filamentous Pf1-like bacteriophage (Pf phage) (5, 6). The Pf prophage is also prevalent among clinical P. aeruginosa isolates from people with CF (7–13), and approximately 107 Pf phage per ml has been detected in the sputum of people with CF, where they interact with host polymers, such as mucin, to increase viscosity (14). These observations suggest that Pf phage may play a role in infection pathogenesis.

Indeed, previous work showed that the deletion of the Pf prophage from the P. aeruginosa chromosome reduced virulence in a murine pneumonia model (15). However, in that study, the virulence of a Pf phage-deficient mutant was compared to that of wild-type bacteria, where, presumably, the level of Pf phage produced by P. aeruginosa in vivo was likely not as high as that observed under in vitro conditions, where phage titers could be as high as 1010 PFU/ml (16). At present, it is not clear how the production of biofilm-relevant quantities of Pf phage affects pathogenesis. Thus, we investigated how the production of abundant quantities of Pf phage affected bacterial infection phenotypes and the host immune response.

We found that P. aeruginosa producing Pf phage at levels comparable to those achieved in biofilms promotes phenotypes typically associated with chronic infections, including a noninvasive phenotype, resistance to phagocytosis, and a tempered inflammatory response by the host. These in vivo observations suggest that Pf phage may contribute to the establishment of chronic infections and may help P. aeruginosa evade host defense mechanisms.

RESULTS

Production of Pf phage by P. aeruginosa reduces inflammation and dissemination.

To examine how the production of abundant Pf phage affected pathogenesis, we superinfected P. aeruginosa PAO1 with Pf phage strain Pf4. Superinfective Pf4 is spontaneously generated by P. aeruginosa biofilms and can infect bacterial hosts that already contain Pf4 integrated into the chromosome as a prophage, causing lytic Pf4 replication (15). Engineered strains of P. aeruginosa unable to produce Pf4 are still susceptible to superinfection by Pf4 and produce wild-type levels of phage (14). Because the basal level of Pf4 production in PAO1 broth cultures is very low (14), we examined pathogenesis in the lungs of mice infected with either wild-type PAO1 or PAO1 superinfected with Pf4 (PAO1+Pf4).

PAO1+Pf4 produced ∼105 phage particles per 10,000 bacterial cells (Fig. 1A), similar to the amount of Pf4 produced by P. aeruginosa biofilms (14, 16). In contrast, PAO1 produced about 3 Pf phage particles per 10,000 bacterial cells, nearly 5 log units less. We then intratracheally infected mice with PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4. The amount of Pf4 in homogenized lungs was enumerated at different times postinfection (Fig. 1B and S1A in the supplemental material). Relative to the amount of Pf phage in the inoculum, in vivo Pf4 levels were elevated, suggesting either an elevated rate of phage production or an accumulation of Pf phage in the lung.

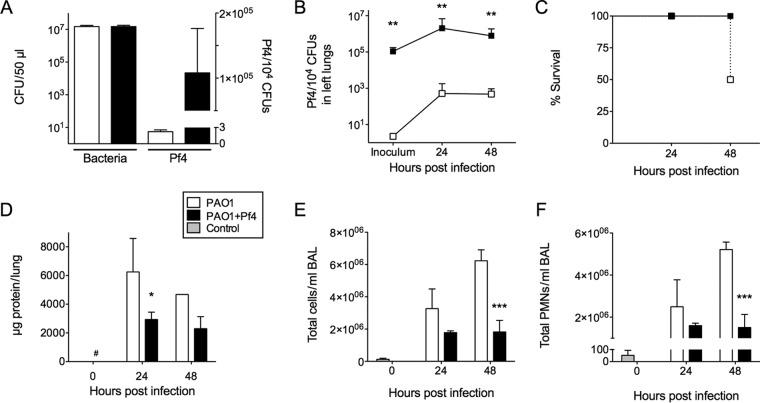

FIG 1.

In vivo Pf phage production by P. aeruginosa reduces mortality, acute lung injury, and recruitment of inflammatory cells. (A) Pf4 was enumerated by qPCR, and the number of Pf4 phage was normalized to the numbers of bacteria (in numbers of CFU). Results are the mean ± SD from three experiments. See also Fig. S1A. (B) Pf4 production in whole homogenized left lungs was monitored by qPCR. Results are the mean ± SD for eight animals per condition, except for PAO1 at the 48-h time point, where there were five animals. **, P < 0.01. (C) Infection with PAO1 resulted in a 50% mortality rate (4/8 animals), while all mice infected with PAO1+Pf4 survived (8/8 animals). It should be noted that one of the PAO1-infected mice succumbed to infection while in queue for processing at 48 h postinfection. Results for this animal were included in this study. However, the other three mice that succumbed to PAO1 infection in the middle of the night were not included to avoid bias. Thus, the results for PAO1 at the 48-h time point included five animals. (D) BAL fluid was collected from PAO1- or PAO1+Pf4-infected lungs, and total protein was quantified. Results are the mean ± SD for four animals for all samples except for the sample for PAO1 at the 48-h time point, where the results are for 1 animal. *, P < 0.05; #, the value is below the detection limit of 125 μg/ml. (E and F) Total leukocyte and PMN counts in BAL fluid were measured by flow cytometry. The key to the bars is the same as that provided in Fig. 1D. Results are the mean ± SD for three animals per condition. ***, P < 0.001.

We found that half of the mice infected with PAO1 died within 48 h (Fig. 1C), whereas none of the mice infected with PAO1+Pf4 succumbed to infection. In addition, we noted that lungs from surviving animals infected with PAO1 showed noticeable signs of hemorrhage and edema, which were not seen in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice (Fig. S2), suggesting greater acute lung injury. Accordingly, the total protein content in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, a measure of acute lung injury, was higher in PAO1-infected mice than PAO1+Pf4-infected mice (Fig. 1D).

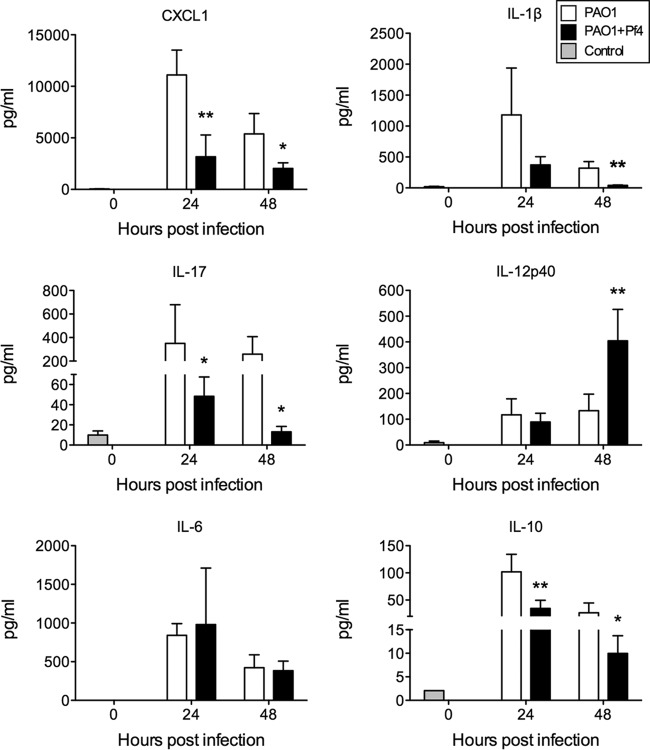

Acute lung injury is typically accompanied by an excessive influx of inflammatory cells (17). Using flow cytometry, we detected more total CD45+ leukocytes in the airways of PAO1-infected mice than in the airways of PAO1+Pf4-infected mice (Fig. 1E), the majority of which were, not surprisingly, neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) (Fig. 1F). The number of macrophages also increased over the course of infection in both groups. However, we did not observe a significant difference in macrophage numbers between PAO1- and PAO1+Pf4-infected mice (data not shown). Consistently, the levels of production of the neutrophil chemokine CXCL1 and the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-17 were elevated in the BAL fluid of PAO1-infected mice (Fig. 2). However, the levels of IL-12p40, a proinflammatory cytokine, were lower at 48 h in the BAL fluid of PAO1-infected mice, while those of IL-10, an immunosuppressive factor, were higher at 24 and 48 h in the BAL fluid of PAO1-infected mice.

FIG 2.

Proinflammatory cytokine levels are lower in BAL fluid collected from animals infected by P. aeruginosa producing Pf4 than in animals infected by wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1. Cytokines were quantified in BAL fluid by the Luminex assay. Results are the mean ± SD from four experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

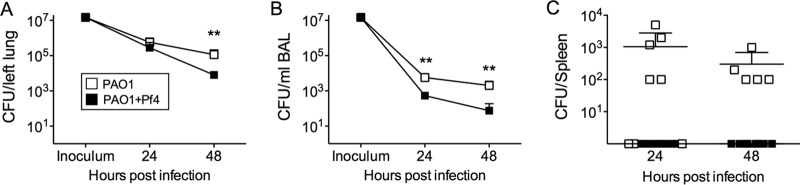

One possible explanation for the reduced lung injury in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice is that there were fewer bacteria in the lungs postinfection. In lung homogenates from both PAO1- and PAO1+Pf4-infected mice, similar numbers of bacteria were recovered at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 3A), indicating that the reduced lung injury in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice was not due to lower bacterial loads at this time. However, after 48 h, bacterial numbers were lower in the PAO1+Pf4-infected group than in PAO1-infected mice, suggesting that the infection was beginning to resolve.

FIG 3.

Pf phage production inhibits bacterial dissemination in vivo. (A and B) Viable bacteria were enumerated in lung homogenates (A) or BAL fluid (B). Control mice showed sterile lungs and BAL fluid after 48 h (n = 4). Results are the mean ± SD for eight animals per condition, except for PAO1 at the 48-h time point, where there were five animals. **, P < 0.01. (C) At 24 and 48 h postinfection, spleens were collected and homogenized. Viable bacteria were then enumerated. Control mice (n = 4) showed sterile spleens after 48 h. Results are the mean ± SD for eight animals per condition, except for PAO1 at the 48-h time point, where there were five animals.

In BAL fluid, which collects bacteria that had not been cleared or invaded the tissue space, significantly (P < 0.01) more bacteria were recovered from animals infected with PAO1 than animals infected with PAO1+Pf4 at all time points postinfection (Fig. 3B). Bacterial aggregation likely did not account for the reduced numbers of CFU detected in BAL fluid, as similar bacterial counts were found in BAL fluid after mechanical homogenization (Fig. S1B). Because BAL fluid contains bacteria that were present in and washed out of the airways and alveolar spaces, these results raise the possibility that PAO1+Pf4 was more adherent to the lung mucosa than PAO1 and was not dislodged as easily as PAO1 by lavage. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections revealed an accumulation of eosinophilic material with punctate hematoxylin staining in the airway lumen of mice infected with PAO1+Pf4, which was not seen in the lungs of mice infected with PAO1 (Fig. S3). The presence of these blockages could account for the reduced number of bacteria present in BAL fluid collected from PAO1+Pf4-infected lungs, as the bacteria could have become trapped. Consistently, spleens collected from PAO1+Pf4-infected animals were sterile, whereas spleens collected from animals infected with PAO1 contained bacteria (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results suggest that the production of filamentous phage by P. aeruginosa reduces inflammation and dissemination by sequestering bacteria within the lung.

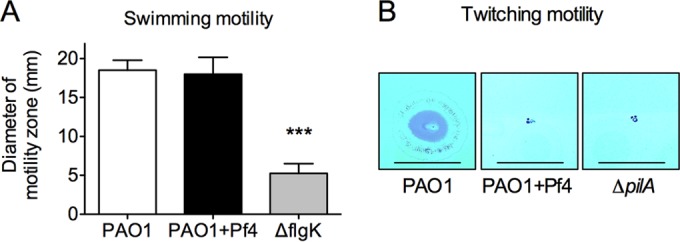

Pf phage impacts twitching but not swimming motility.

Bacterial motility is important for bacterial invasiveness in vivo (18, 19). Therefore, we assessed the impact of Pf phage production on motility. We found that both PAO1 and PAO1+Pf4 demonstrated swimming motility comparable to that of the flagellar ΔflgK mutant (Fig. 4A), suggesting that differences in dissemination in vivo were not due to the reduced swimming motility of PAO1+Pf4. We also compared twitching motility, which is mediated by type IV pili. While PAO1 demonstrated twitching motility, PAO1+Pf4 exhibited minimal twitching motility that was approximately equal to that of the type IV pilus ΔpilA mutant (Fig. 4B). As type IV pili are the receptors that Pf4 utilizes to infect PAO1 (20), these findings are consistent with the loss or inactivation of type IV pili from Pf4-producing cells, which would impair the ability of PAO1+Pf4 to disseminate (19).

FIG 4.

Bacterial motility is affected by Pf4 production. (A) The swimming motility of PAO1, PAO1+Pf4, and the ΔflgK flagellar mutant was measured after growth at 37°C for 24 h on 0.3% swim agar. Results are the mean ± SD from three experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Representative images showing twitching motility at the agar-plastic interface of petri dishes. PAO1, PAO1+Pf4, or a twitching-deficient type IV pilus mutant (the ΔpilA mutant) was stab inoculated through the agar to the plastic dish below. Bacteria were allowed to grow for 24 h at 37°C, after which the agar was removed and the adherent bacteria on the petri dish were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Bars, 10 mm.

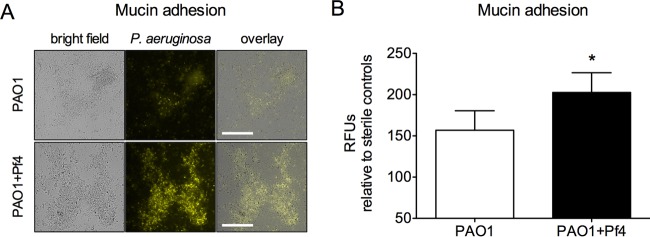

Pf phage production promotes bacterial adhesion to mucin.

Because Pf phage promotes bacterial adhesion to abiotic surfaces (21) and increases the viscosity of mucin and other host polymers (14), it is possible that Pf phage could inhibit bacterial dissemination in vivo by increasing bacterial adhesion to mucosal surfaces. To test this idea, fluorescent PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 was placed onto mucin-coated glass. After 15 min, nonadherent bacteria were washed away and adherent bacteria were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. More PAO1+Pf4 bacteria than PAO1 bacteria remained (Fig. 5), indicating that Pf4 production enhanced bacterial adhesion to mucin.

FIG 5.

Production of filamentous Pf phage by P. aeruginosa promotes adhesion to mucin. (A) Representative images showing PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 (constitutively expressing YFP) adhering to mucin-coated glass surfaces after nonadherent bacteria were washed away. Bars, 50 μm. (B) Adhesion to mucin was quantified by measurement of the number of relative fluorescent units (RFUs), and the value was normalized to that for sterile mucin-coated glass to account for background fluorescence. Results are the mean ± SD from four separate experiments. *, P < 0.05.

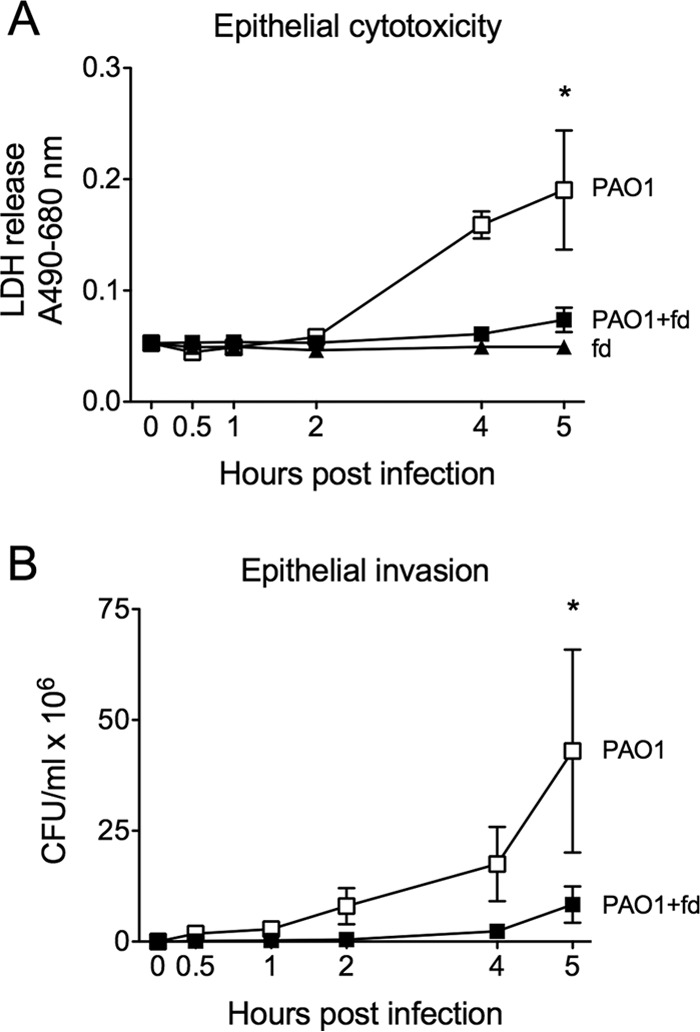

Filamentous phage reduces cytotoxicity and bacterial invasion of epithelial cultures.

Another possible explanation for the decreased dissemination of PAO1+Pf4 in mice is that both PAO1 and PAO1+Pf4 escaped the lungs equally well but PAO1+Pf4 grew more slowly as a result of producing abundant Pf4 (Fig. S4A), thereby hindering its ability to colonize other tissues. To address this possibility, we used filamentous fd phage, which, like Pf4, belongs to the genus Inovirus and has a filamentous morphology similar to that of Pf4. fd phage uses Escherichia coli as a host and cannot replicate in P. aeruginosa. Thus, fd does not reduce the growth rate of PAO1 (Fig. S4A and B). When purified fd phage was mixed with PAO1 and added to the apical surface of polarized organotypic human tracheal epithelial cell cultures, the bacteria were less cytotoxic to the epithelial cells (Fig. 6A) and bacterial invasion of the basal compartment was reduced (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that P. aeruginosa was less damaging to epithelial cells when filamentous phage was present and that filamentous phage sequestered bacteria on the apical side of the epithelial cell cultures.

FIG 6.

Filamentous phage reduces cytotoxicity and bacterial invasion of epithelial cultures. The filamentous bacteriophage fd, which infects E. coli and cannot infect P. aeruginosa (Fig. S3), was purified, and ∼2 × 108 PFU was mixed with ∼1 × 107 CFU of P. aeruginosa PAO1. PAO1 or PAO1+fd was then applied to the apical surface of polarized organotypic human tracheal epithelial cell cultures. (A) Cytotoxicity was measured as the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from damaged epithelial cells into the basal medium. (B) Bacteria that penetrated the epithelial layer were detected in the basal compartment by enumerating the CFU at the indicated times. Results are the mean ± SD from four separate experiments. *, P < 0.05 by comparison of the results for PAO1 and PAO1+fd by 2-way analysis of variance.

P. aeruginosa producing Pf phage alters macrophage polarization.

Macrophages are critical mediators of inflammation and are effective in promoting the clearance of acute P. aeruginosa infection in the lung (22). During an inflammatory response, macrophages functionally polarize into two broad subpopulations, designated M1, or classically activated macrophages, and M2, or alternatively activated macrophages, depending on the stimuli to which they are exposed (23). M1 macrophages generally predominate early during bacterial infection and are characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines and antimicrobial factors, such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ), IL-12, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and an enhanced ability to phagocytize and kill bacteria (24, 25). In contrast, M2 macrophages accumulate later, function to reduce the inflammatory response, are less effective at bacterial phagocytosis, and are characterized by expression of IL-10 and Arg1 (26, 27).

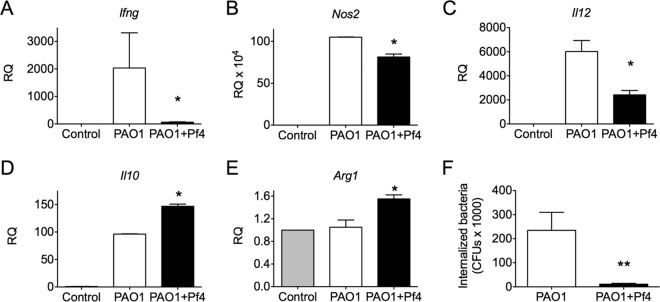

Given that the inflammatory response was dampened in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice compared to the response in PAO1-infected mice, we assessed whether Pf4 production by P. aeruginosa influenced macrophage polarization. To test this, we isolated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from mice and measured the expression of M1 and M2 markers after challenge with PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4. PAO1-infected BMDMs expressed mRNAs for the M1 markers Ifng, Nos2, and Il12a at significantly (P < 0.05) higher levels, especially for Ifng, than PAO1+Pf4-infected BMDMs (Fig. 7A to C). In contrast, PAO1+Pf4-infected BMDMs expressed the M2 markers Il10 and Arg1 at higher levels than PAO1-infected BMDMs (Fig. 7D and E). In addition, significantly (P < 0.01) less PAO1+Pf4 than PAO1 was internalized by BMDMs (Fig. 7F). These results raise the possibility that Pf phage production by P. aeruginosa influences macrophage polarization.

FIG 7.

Pf phage production by P. aeruginosa promotes M2-like macrophage polarization and reduces bacterial susceptibility to phagocytosis. (A to E) Macrophages were challenged with PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 for 1 h. After the bacteria were removed, macrophages were incubated for an additional 6 h before RNA was harvested. The expression of genes associated with M1 macrophage polarization (Ifng, Nos2, and Il12a) or M2 macrophage polarization (Il10 and Arg1) was analyzed by qPCR. Expression is displayed as the relative quantity (RQ) compared to the quantity for the housekeeping gene Hprt. Results are the mean ± SD from duplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05 relative to the results for PAO1. (F) After 1 h of infection with PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4, a significant difference (**, P < 0.01) between the amount of PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 internalized by macrophages was observed. Results are the mean ± SD from three experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that filamentous Pf phage causes P. aeruginosa to be less invasive, less inflammatory, and more resistant to phagocytosis by macrophages, phenotypes that are typically associated with chronic infection. Previous work indicated that deletion of the Pf4 prophage from P. aeruginosa reduced its virulence compared to that of wild-type P. aeruginosa carrying the Pf4 prophage (15). We took a different approach and investigated how the production of biofilm-relevant quantities of Pf phage by P. aeruginosa might affect pathogenesis. However, our approach had limitations. First, we artificially increased the level of phage production in P. aeruginosa using purified phage, and it is possible that the spontaneous production of similar amounts of Pf phage by P. aeruginosa would produce different results. Second, in the model of acute infection that we used, the lack of dissemination and the reduced inflammation caused by PAO1+Pf4 were beneficial to the host, and the infection appeared to be clearing at 48 h. Thus, conclusions drawn from the 48-h time point could be due to reduced bacterial loads in the lung at this time rather than the effects of the phage.

It is likely that other bacterial phenotypes important for infection pathogenesis are affected by the production of large amounts of Pf phage. For example, the global transcriptional regulator MvaT represses Pf4 production in P. aeruginosa (20). Because MvaT also regulates several virulence genes (28), it is possible that the derepression of Pf4 is accompanied by altered expression of virulence genes, which may affect pathogenesis. However, while Pf phage production undoubtedly affects many aspects of bacterial physiology, several lines of evidence support our conclusion that Pf phage prevents bacterial dissemination by sequestering bacteria within the lungs. First, Pf4 promotes bacterial adhesion to mucin, a major component of mucosal surfaces. Second, filamentous phage reduces bacterial invasion through epithelial monolayers. Third, at the 24-h time point, fewer bacteria were washed out of the lung by lavage in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice than in PAO1-infected animals, even though equal numbers of bacteria were present in the lung homogenates.

Because Pf phage is abundant on the surface of P. aeruginosa (21) and Pf phage is structurally similar to type IV pili (29), Pf phage and type IV pili may promote bacterial adhesion to mucosal surfaces through similar mechanisms (30). As Pf phage-producing bacteria are deficient in twitching motility, they might be expected to be less invasive, similar to the noninvasive phenotype displayed by hyperpiliated, twitching-deficient strains of P. aeruginosa (19). Furthermore, Pf phage can increase the viscosity of host polymers such as mucin (14), which could trap bacteria within the host polymers present at sites of infection, a possibility consistent with the presence of airway blockages in histological sections from PAO1+Pf4-infected mice.

Overall, our data show a bias for reduced inflammation in vivo when Pf phage is produced by P. aeruginosa. For example, PAO1 caused greater acute lung injury and attracted more neutrophils to the airways than PAO1+Pf4, which corresponded to the higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid collected from PAO1-infected mice. The sustained inflammatory response induced by PAO1 may also promote bacterial dissemination by increasing vascular permeability and tissue damage (31, 32).

The reduced inflammation in PAO1+Pf4-infected mice may be related to the ability of PAO1+Pf4 to affect the polarization state of macrophages. Differences in the macrophage activation state could account for the reduced acute lung injury caused by PAO1+Pf4 relative to that caused by PAO1. However, after 48 h of infection by PAO1, the level of the M1 marker IL-12 in BAL fluid was elevated, but M1 was suppressed in macrophages. The production of IL-12 in vivo by other cell types could explain this. Furthermore, while IL-12 is an M1 marker (25), IL-12 expression does not always track with M1 differentiation (33).

Consistent with the possibility that PAO1+Pf4 polarized macrophages toward an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype, PAO1+Pf4 was more resistant to phagocytic uptake by macrophages. Resistance to phagocytosis may be related to many factors, including the loss of type IV pili (34), the polarization of macrophages toward an M2 program (35–37), or direct interference with phagocytosis by Pf phage. While the mechanism remains to be elucidated, the reduced phagocytic activity of macrophages against P. aeruginosa producing Pf phage could contribute to infection persistence.

Overall, our results suggest that the lack of dissemination and the reduced inflammation caused by the production of filamentous Pf phage set up conditions that could promote persistent infection by P. aeruginosa. Given our previous observations that Pf phage promotes both desiccation survival and antibiotic tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms (14), the observations from our in vivo studies presented here further implicate Pf phage as a contributor to the ability of P. aeruginosa to establish chronic infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Pf4 and fd bacteriophages.

The Pf4 and fd bacteriophages were purified as described previously (14). Briefly, P. aeruginosa PAO1 (38) (obtained from the laboratory of C. Manoil) infected with Pf4 or Escherichia coli (ATCC 15669) infected with fd (ATCC 15669-B2) was grown overnight in LB broth at 37°C with shaking. The bacteria were then removed by centrifugation (9,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature), and the supernatants were filter sterilized using 0.2-μm-pore-size syringe filters. NaCl was then added to 0.5 M, followed by the addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 to a final concentration of 10% (wt/vol). The samples were allowed to precipitate overnight at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. The phage pellet was washed gently with 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After the supernatant was discarded, 500 μl PBS was added to the phage pellet, which was allowed to dissolve overnight. Phage was then quantified either by determination of the number of PFU on lawns of E. coli for fd or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Pf4, as described below.

Growth curves.

An isolated colony of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown on an LB plate was picked and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.1 in 3 ml LB broth at 37°C with shaking. At this time, 100 μl PBS, Pf4, or fd (both at 1010 phage per ml) was added, and growth was measured by determination of the absorbance (OD600) using a Genesys 20 spectrophotometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA).

In vivo infection model.

An isolated colony of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown on an LB plate was picked and grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600, 0.5) in 4 ml LB broth at 37°C with shaking. The culture was then split into two aliquots. One aliquot was infected with 100 μl of Pf4 stock (∼1010 Pf4 phage/ml), and the other was supplemented with 100 μl sterile PBS. These cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. On the following day, the bacteria, designated PAO1 and PAO1+Pf4, were pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min. The Pf4 phage in the supernatants of these overnight cultures was quantified by qPCR (see below). The bacterial pellet was resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 3.0 × 108 CFU/ml. Mice (C57BL/6, male; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were challenged with PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 (1.5 × 107 CFU in 50 μl PBS; Fig. 1A) by oropharyngeal aspiration, as described previously (39). Control mice were challenged with 50 μl sterile PBS. The University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures.

Sample collection and analyses.

Mice were sacrificed at 24 and 48 h postinfection. The left lung was isolated, while the right lung was lavaged with 1.5 ml sterile PBS as described previously (39), and the spleens were harvested. Left lungs and spleens were homogenized in 1 ml cold PBS, serially diluted in PBS, and plated to quantify the viable bacteria. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples (1-ml aliquots) were pelleted and resuspended in 750 μl ACK lysis buffer (Gibco, Chagrin Falls, OH) for 30 s, followed by washing in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2% fetal calf serum (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS] buffer). The cell-free fraction was frozen for protein assays. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml FACS buffer and counted using a Bio-Rad TC20 automated cell counter. The BAL fluid cells were stained with the following antibodies for flow cytometry analysis: CD45-Alexa Fluor 700, Ly6G-allophycocyanin, F4/80-e450, CD11b-peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5, CD11c-Alexa Fluor 780, and SiglecF-phycoerythrin (PE) (all were from eBioscience, except for SiglecF-PE, which was from BD Biosciences). After staining, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and then analyzed using a BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer and FlowJo software. The number of neutrophils was calculated as the frequency of CD45+, Ly6G-positive, and F4/80-negative cells among all acquired events times the total BAL fluid cell number.

The Luminex assay and a multiplex fluorescent bead array (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used to quantify the levels of IL-1β, CXCL1/keratinocyte chemoattractant, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-6, and IL-17 in BAL fluid using analytes from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The levels in samples were measured in duplicate, and the data were normalized to those on a standard curve generated for each factor. The total protein content in BAL fluid samples was measured with a Pierce 660-nm protein assay (Thermo, Waltham, MA). The contents in samples were measured in duplicate, and the data were normalized to those on a standard curve generated with bovine serum albumin.

The bacteria in the remaining BAL fluid were enumerated after 1:10 dilution in PBS followed by homogenization using a handheld homogenizer to break apart bacterial aggregates. Samples were then serially diluted and plated to enumerate viable bacteria.

Quantification of Pf4 by qPCR.

As several factors can produce plaques on bacterial lawns (other species of phage, pyocins, host defensins, etc.), we quantitated Pf4 using a qPCR assay as described previously (14), with modifications. Briefly, PCR primers that amplify 135 bp of the circularization site of the circular Pf4 genome were used (primers RF-F [5′-TAGGCATTTCAGGGGCTTGG] and RF-R [5′-GAGCTACGGAGTAAGACGCC]). As primers targeting this region do not amplify the linear Pf4 prophage sequence in the PAO1 chromosome (21), only circularized Pf4 DNA is detected.

To quantitate intact Pf4 particles in bacterial supernatants and lung homogenates, bacterial cells and debris were removed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were treated with DNase (100 μg/ml) for 60 min to destroy unprotected DNA, followed by heating at 70°C for 15 min to denature the DNase and any phage particles, releasing intact Pf4 DNA. Samples were then diluted 10 times with water, and 2 μl was used as a template in 10-μl qPCR mixtures containing 5 μl SYBR Select master mix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and 100 nM primers RF-F and RF-R. All samples were run in duplicate. Cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min on an ABI 7900 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For a standard curve, the sequence targeted by the RF-F and RF-R primers was inserted into the plasmid pCR2.1, and serial dilutions of this plasmid were amplified.

Bacterial adhesion assay.

Glass-bottom dishes (diameter, 35 mm; MatTek) were coated with 100 μl of porcine gastric mucin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in PBS at 80 mg/ml. The mucin was allowed to dry at room temperature overnight. Mucin-coated dishes were then rinsed with 1 ml PBS followed by the addition of either PAO1 or PAO1+Pf4 (constitutively expressing yellow fluorescent protein [YFP] [40]) to overnight cultures at 3 × 108 CFU in 3 ml LB broth. The samples were incubated statically at 37°C for 15 min, followed by two gentle rinses with 1 ml PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria. Adherent bacteria were imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Adherence was quantified by measuring the total fluorescence intensity in two fields of view from four replicates using Volocity image analysis software (Improvision; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). To calculate the number of relative fluorescent units (RFUs), the measured fluorescence intensity of each field of view was divided by the background fluorescence intensity of sterile mucin controls and multiplied by 100.

Bacterial motility assays.

Swimming motility was assessed using a sterilized platinum wire to stab P. aeruginosa PAO1, PAO1+Pf4, or the ΔflgK mutant (41) into 0.3% agar plates. The swimming zone was measured after an overnight incubation at 37°C, as described previously (42). Twitching motility was assessed by stab inoculating PAO1, PAO1+Pf4, or the ΔpilA mutant (43) through a 1.5% agar plate to the underlying plastic dish. After incubation for 24 h, the agar was carefully removed, and the zone of motility on the plastic dish was visualized and measured after staining with 0.05% Coomassie brilliant blue (44).

Macrophage culture and assays.

Isolation and activation of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were done as described previously (22). Briefly, marrow cells were cultured for 7 days in Mac medium (RPMI, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 20% supernatant from the L929 cell line). BMDMs were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 bacterial cells per macrophage for 1 h at 37°C, washed twice with RPMI containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria, and then cultured for an additional 6 h. RNA was then isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The level of expression of Nos2, Infg, Il12a, Il10, and Arg1 relative to that of the housekeeping gene Hprt was measured by qPCR using predesigned primer and probe sets (ABI TaqMan gene expression assays). To assess phagocytosis, BMDMs were infected with bacteria at an MOI of 50 per macrophage for 1 h in RPMI–10% FBS, washed with RPMI–100 μg/ml gentamicin for 15 min to kill extracellular bacteria, and then lysed with 1 ml 0.1% Triton X-100 in water for 5 min. Samples were then serially diluted, and viable bacteria were enumerated.

ALI culture and assays.

Cryopreserved primary human tracheal epithelial cells at passage 1 or 2 were used for differentiated air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures, as described previously (45). Briefly, epithelial cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Culture inserts with 3-μm pores (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) were used so that bacteria added at later times could be detected in the basal compartment. The epithelial cells initially grew on culture inserts until they were fully confluent, after which they were switched to ALI culturing for 3 weeks. After this time, overnight cultures of PAO1 grown in 3 ml LB at 37°C with shaking were pelleted by centrifugation (9,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature), washed, and resuspended at 1 × 108 CFU/ml in HBSS. Sterile PBS (200 μl) or purified fd phage (200 μl of a 2 × 1010-PFU/ml stock) was then added to 1.8 ml HBSS or 1.8 ml PAO1 in HBSS. One hundred microliters of PAO1, PAO1+fd, or fd phage in HBSS was then added to the apical surface of the ALI cultures, and 50-μl aliquots were collected from the basal compartment at the times indicated above. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from damaged epithelial cells was quantitated using a colorimetric LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Thermo, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The bacterial numbers in the basal supernatants were measured by serial dilution and enumeration of the CFU.

Data analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (version 5) software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test, unless otherwise specified. Differences were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We declare no conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to C. W. Frevert and B. W. Johnson at the University of Washington's Histology and Imaging Core. We also thank B. S. Tseng for providing P. aeruginosa expressing YFP.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL089455, HL098067, and HL128995 (to W.C.P.), NIH grant HL089215 (to T.S.H.), and a Cystic Fibrosis Foundation postdoctoral fellowship (to P.R.S.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00648-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. 2003. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168:918–951. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elder MJ, Stapleton F, Evans E, Dart JK. 1995. Biofilm-related infections in ophthalmology. Eye 9(Pt 1):102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, Pulcini E, Secor P, Sestrich J, Costerton JW, Stewart PS. 2008. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 16:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjarnsholt T, Alhede M, Eickhardt-Sorensen SR, Moser C, Kuhl M, Jensen PO, Hoiby N. 2013. The in vivo biofilm. Trends Microbiol 21:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteley M, Bangera MG, Bumgarner RE, Parsek MR, Teitzel GM, Lory S, Greenberg EP. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860–864. doi: 10.1038/35101627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folsom JP, Richards L, Pitts B, Roe F, Ehrlich GD, Parker A, Mazurie A, Stewart PS. 2010. Physiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms as revealed by transcriptome analysis. BMC Microbiol 10:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finnan S, Morrissey JP, O'Gara F, Boyd EF. 2004. Genome diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients and the hospital environment. J Clin Microbiol 42:5783–5792. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5783-5792.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirov SM, Webb JS, O'May CY, Reid DW, Woo JK, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. 2007. Biofilm differentiation and dispersal in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiology 153:3264–3274. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manos J, Arthur J, Rose B, Tingpej P, Fung C, Curtis M, Webb JS, Hu H, Kjelleberg S, Gorrell MD, Bye P, Harbour C. 2008. Transcriptome analyses and biofilm-forming characteristics of a clonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the cystic fibrosis lung. J Med Microbiol 57:1454–1465. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/005009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathee K, Narasimhan G, Valdes C, Qiu X, Matewish JM, Koehrsen M, Rokas A, Yandava CN, Engels R, Zeng E, Olavarietta R, Doud M, Smith RS, Montgomery P, White JR, Godfrey PA, Kodira C, Birren B, Galagan JE, Lory S. 2008. Dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:3100–3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winstanley C, Langille MG, Fothergill JL, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Paradis-Bleau C, Sanschagrin F, Thomson NR, Winsor GL, Quail MA, Lennard N, Bignell A, Clarke L, Seeger K, Saunders D, Harris D, Parkhill J, Hancock RE, Brinkman FS, Levesque RC. 2009. Newly introduced genomic prophage islands are critical determinants of in vivo competitiveness in the Liverpool epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genome Res 19:12–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.086082.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fothergill JL, Walshaw MJ, Winstanley C. 2012. Transmissible strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infections. Eur Respir J 40:227–238. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00204411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knezevic P, Voet M, Lavigne R. 2015. Prevalence of Pf1-like (pro)phage genetic elements among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Virology 483:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Secor PR, Sweere JM, Michaels LA, Malkovskiy AV, Lazzareschi D, Katznelson E, Rajadas J, Birnbaum ME, Arrigoni A, Braun KR, Evanko SP, Stevens DA, Kaminsky W, Singh PK, Parks WC, Bollyky PL. 2015. Filamentous bacteriophage promote biofilm assembly and function. Cell Host Microbe 18:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice SA, Tan CH, Mikkelsen PJ, Kung V, Woo J, Tay M, Hauser A, McDougald D, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S. 2009. The biofilm life cycle and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are dependent on a filamentous prophage. ISME J 3:271–282. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McElroy KE, Hui JG, Woo JK, Luk AW, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA, Thomas T. 2014. Strain-specific parallel evolution drives short-term diversification during Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E1419–E1427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314340111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. 2002. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell 111:635–646. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staudinger BJ, Muller JF, Halldorsson S, Boles B, Angermeyer A, Nguyen D, Rosen H, Baldursson O, Gottfreethsson M, Guethmundsson GH, Singh PK. 2014. Conditions associated with the cystic fibrosis defect promote chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:812–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comolli JC, Hauser AR, Waite L, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS, Engel JN. 1999. Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products PilT and PilU are required for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Infect Immun 67:3625–3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castang S, Dove SL. 2012. Basis for the essentiality of H-NS family members in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194:5101–5109. doi: 10.1128/JB.00932-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb JS, Lau M, Kjelleberg S. 2004. Bacteriophage and phenotypic variation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J Bacteriol 186:8066–8073. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8066-8073.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manicone AM, Birkland TP, Lin M, Betsuyaku T, van Rooijen N, Lohi J, Keski-Oja J, Wang Y, Skerrett SJ, Parks WC. 2009. Epilysin (MMP-28) restrains early macrophage recruitment in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Immunol 182:3866–3876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sica A, Mantovani A. 2012. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacMicking J, Xie QW, Nathan C. 1997. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol 15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, Mantovani A, Martinez FO, Mege JL, Mosser DM, Natoli G, Saeij JP, Schultze JL, Shirey KA, Sica A, Suttles J, Udalova I, van Ginderachter JA, Vogel SN, Wynn TA. 2014. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benoit M, Desnues B, Mege JL. 2008. Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. J Immunol 181:3733–3739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtnekert J, Kawakami T, Parks WC, Duffield JS. 2013. Changes in macrophage phenotype as the immune response evolves. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diggle SP, Winzer K, Lazdunski A, Williams P, Camara M. 2002. Advancing the quorum in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: MvaT and the regulation of N-acylhomoserine lactone production and virulence gene expression. J Bacteriol 184:2576–2586. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.10.2576-2586.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbs M, Mattick JS. 1993. Common components in the assembly of type 4 fimbriae, DNA transfer systems, filamentous phage and protein-secretion apparatus: a general system for the formation of surface-associated protein complexes. Mol Microbiol 10:233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doig P, Todd T, Sastry PA, Lee KK, Hodges RS, Paranchych W, Irvin RT. 1988. Role of pili in adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to human respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun 56:1641–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart CL, Goyert SM. 1996. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity 4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80254-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW, Greenberger MJ, Danforth JM, Kunkel RG, Strieter RM. 1995. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha mediates lung leukocyte recruitment, lung capillary leak, and early mortality in murine endotoxemia. J Immunol 155:1515–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahan RS, Birkland TP, Smigiel KS, Vandivort TC, Rohani MG, Manicone AM, McGuire JK, Gharib SA, Parks WC. 2016. Stromelysin-2 (MMP10) moderates inflammation by controlling macrophage activation. J Immunol 197:899–909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speert DP, Loh BA, Cabral DA, Salit IE. 1986. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa by human neutrophils and monocyte-derived macrophages is correlated with bacterial piliation and hydrophobicity. Infect Immun 53:207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krysko O, Holtappels G, Zhang N, Kubica M, Deswarte K, Derycke L, Claeys S, Hammad H, Brusselle GG, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV, Bachert C. 2011. Alternatively activated macrophages and impaired phagocytosis of S. aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy 66:396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thurlow LR, Hanke ML, Fritz T, Angle A, Aldrich A, Williams SH, Engebretsen IL, Bayles KW, Horswill AR, Kielian T. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J Immunol 186:6585–6596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol 3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holloway BW, Krishnapillai V, Morgan AF. 1979. Chromosomal genetics of Pseudomonas. Microbiol Rev 43:73–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston LK, Rims CR, Gill SE, McGuire JK, Manicone AM. 2012. Pulmonary macrophage subpopulations in the induction and resolution of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47:417–426. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0090OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klausen M, Heydorn A, Ragas P, Lambertsen L, Aaes-Jorgensen A, Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2003. Biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa wild type, flagella and type IV pili mutants. Mol Microbiol 48:1511–1524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drake D, Montie TC. 1988. Flagella, motility and invasive virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol 134:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao K, Tseng BS, Beckerman B, Jin F, Gibiansky ML, Harrison JJ, Luijten E, Parsek MR, Wong GC. 2013. Psl trails guide exploration and microcolony formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 497:388–391. doi: 10.1038/nature12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semmler AB, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. 1999. A re-examination of twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 145(Pt 10):2863–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai Y, Altemeier WA, Vandree J, Piliponsky AM, Johnson B, Appel CL, Frevert CW, Hyde DM, Ziegler SF, Smith DE, Henderson WR Jr, Gelb MH, Hallstrand TS. 2014. Increased density of intraepithelial mast cells in patients with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction regulated through epithelially derived thymic stromal lymphopoietin and IL-33. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133:1448–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.