Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is a heterogeneous disease arising from at least two precursors—the conventional adenoma (CA) and the serrated polyp. We and others have previously shown a relationship between the human gut microbiota and colorectal cancer; however, its relationship to the different early precursors of colorectal cancer is understudied. We tested, for the first time, the relationship of the gut microbiota to specific colorectal polyp types.

Results

Gut microbiota were assessed in 540 colonoscopy-screened adults by 16S rRNA gene sequencing of stool samples. Participants were categorized as CA cases (n = 144), serrated polyp cases (n = 73), or polyp-free controls (n = 323). CA cases were further classified as proximal (n = 87) or distal (n = 55) and as non-advanced (n = 121) or advanced (n = 22). Serrated polyp cases were further classified as hyperplastic polyp (HP; n = 40) or sessile serrated adenoma (SSA; n = 33). We compared gut microbiota diversity, overall composition, and normalized taxon abundance among these groups.

CA cases had lower species richness in stool than controls (p = 0.03); in particular, this association was strongest for advanced CA cases (p = 0.004). In relation to overall microbiota composition, only distal or advanced CA cases differed significantly from controls (p = 0.02 and p = 0.002). In taxon-based analysis, stool of CA cases was depleted in a network of Clostridia operational taxonomic units from families Ruminococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Lachnospiraceae, and enriched in the classes Bacilli and Gammaproteobacteria, order Enterobacteriales, and genera Actinomyces and Streptococcus (all q < 0.10). SSA and HP cases did not differ in diversity or composition from controls, though sample size for these groups was small. Few taxa were differentially abundant between HP cases or SSA cases and controls; among them, class Erysipelotrichi was depleted in SSA cases.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that gut microbes may play a role in the early stages of colorectal carcinogenesis through the development of CAs. Findings may have implications for developing colorectal cancer prevention therapies targeting early microbial drivers of colorectal carcinogenesis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0218-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Microbiome, Microbiota, Adenoma, Polyp, Colorectal, Cancer, Serrated

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. CRC represents a heterogeneous group of cancers arising through different combinations of genetic and epigenetic events [2]: the “conventional” pathway to CRC is characterized by adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mutation, chromosomal instability, and paucity of CpG island hypermethylation, while the “serrated” pathway is characterized by B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) mutation, chromosomal stability, and high CpG island hypermethylation [3]. The majority of CRC cases (~60%) arise via the “conventional” pathway, with ~20% arising from the “serrated” pathway and ~20% arising from an alternate pathway [4]. These distinct molecular pathways originate with different precursor lesions: the “conventional” pathway with conventional adenomas (CAs) and the “serrated” pathway with sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs) [4]. An additional serrated polyp type, the hyperplastic polyp (HP), has negligible malignant potential [2]. Different polyp types also have tendencies to present in specific colorectal locations [2, 5].

Mounting evidence implicates gut bacteria as causal players in colorectal carcinogenesis [6], though their distinct contributions through CAs or SSAs have not been examined simultaneously. Stool transplant experiments from colon tumor-bearing mice or human CRC patients to germ-free mice have revealed a critical role of the gut microbiota in CRC development [7, 8]. Additionally, studies in humans, including a study by our group [9], have associated mucosal or stool microbiota composition with presence of colorectal polyps or CRC [6]. Recently, greater attention has been focused on characterizing the gut microbiota across different stages of colorectal carcinogenesis [10, 11], to better distinguish bacteria contributing to CRC initiation (“driver” bacteria) from bacteria proliferating as a result of CRC (“passenger” bacteria) [12]. Microbes and their metabolites have been proposed to promote carcinogenesis by several mechanisms, including induction of inflammatory signaling pathways, genetic mutations, and epigenetic dysregulation [13–15]. Because CRC arises along different molecular pathways from specific precursor lesions at specific colorectal sites, it is possible that different bacteria are involved in each pathway and associated with each precursor type and/or location; however, no studies have characterized the gut microbiota of colorectal polyp cases according to histologic type and location.

Here, we characterize the microbiota of stool samples from 540 colonoscopy-screened individuals. Detailed endoscopy and pathology reports allowed us to classify these individuals as polyp-free controls, CA cases, HP cases, or SSA cases and to define polyp location within the colorectum. We aimed to determine whether overall microbial community composition differs between these groups and to identify bacterial taxa differing across the groups.

Methods

Study population

We included samples from two independent study populations: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Study of In-home Tests for Colorectal Cancer (SIT), hereafter referred to as the CDC study, and the New York University (NYU) Human Microbiome and Colorectal Tumor study, hereafter referred to as the NYU study.

The CDC study enrolled 451 participants at the University of Minnesota/Minnesota Gastroenterology between December 2012 and July 2014, as part of a study to evaluate the performance of in-home screening tests for CRC. The study participants completed fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) and subsequently underwent colonoscopy. Eligible participants were individuals 50–75 years old scheduled to have a colonoscopy for routine screening only, able to read English, and not currently taking anticoagulant medication. Additionally, participants must not have had more than one episode of rectal bleeding in the last 6 months, a positive FOBT in the past 12 months, a colonoscopy in the past 5 years, a personal history of CRC, polyps, or inflammatory bowel disease, or a personal or family history of familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. From the 451 subjects, we further excluded 17 who withdrew from the study, 4 subjects for whom sequencing failed, and 32 subjects with both conventional and serrated polyp types or unclassified polyps, resulting in 398 subjects. The CDC study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) of the University of Minnesota and the CDC, and all participants provided written consent.

The NYU study enrolled 239 participants from Kips Bay Endoscopy Center in New York City between June 2012 and August 2014. Eligible participants were individuals 18 years or older who recently underwent a colonoscopy, were able to read English, and had not been on long-term antibiotic treatment. We further excluded participants that had missing colonoscopy reports (n = 2), personal history of CRC (n = 10) or polyps (n = 49), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 22), previous anastomosis (n = 6), personal history of familial adenomatous polyposis (n = 1), those with their most recent colonoscopy reports >3 years prior to stool sample collection (n = 12), and subjects with both conventional and serrated polyp types or unclassified polyps (n = 12); exclusion due to these non-mutually exclusive criteria resulted in 142 subjects remaining. Of these subjects, 54% were receiving a colonoscopy for routine screening, while the remaining 46% had indications for colonoscopy including abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, change in bowel habit, or family history of polyps/cancer. The NYU study was approved by the IRB of NYU School of Medicine, and all participants provided written consent.

Demographic information assessment

Demographic information (e.g., age, sex, height, weight) was collected by questionnaire in the CDC and NYU studies. BMI was categorized as underweight or normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Colonoscopy

Colorectal polyps were identified at colonoscopy and confirmed by pathology. Polyp-free controls were defined as those with no polyps identified during colonoscopy and no previous history of colorectal polyps. Subjects with histologically confirmed normal biopsies were also included in the control group. CA cases were defined as those with at least one tubular or tubulovillous adenoma and no other polyps of hyperplastic, SSA, or unclassified histology. We further classified CAs as non-advanced if they were <1 cm and had no villous tissue and as advanced if they were ≥1 cm and/or contained villous tissue [16]. HP cases were defined as having at least one HP, with no other polyps of tubular, tubulovillous, SSA, or unclassified histology. SSA cases were defined as having at least one SSA, with or without HP(s), and with no other polyps of tubular, tubulovillous, or unclassified histology. Proximal polyps were defined as polyps located in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, or splenic flexure, and distal polyps were defined as polyps located in the descending colon, sigmoid colon, or rectum. We classified participants as either proximal or distal cases based on the location of their polyp(s); participants with both proximal and distal polyps were classified as distal cases.

Stool samples

All subjects collected stool samples onto the two sections of Beckman Coulter Hemoccult II SENSA® cards (Beckman Coulter, CA) at home. We have previously shown that sample collection by this method preserves stool microbiota composition assessed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing [17]. Other studies have since confirmed this finding, observing that stool collection card sampling produces reproducible and accurate 16S rRNA gene-derived microbiota data [18] and exhibits stability at room temperature for up to 8 weeks [19]. Samples were collected up to 4 months prior to colonoscopy (range 3–122 days prior) in the CDC study or up to 3 years after colonoscopy (range 5–1026 days after) in the NYU study. CDC participant samples were mailed to a laboratory for fecal occult blood testing within several days of stool collection; this testing does not impact stool microbiota composition [18] (see the Quality control section). After testing, samples were refrigerated at 4 °C until shipment to NYU and, upon arrival, were stored at −80 °C until analysis (range 7–183 days from sample collection to receipt by NYU). NYU participant samples were mailed directly to NYU following at-home collection and stored immediately at −80 °C until analysis.

Microbiota assay

DNA was extracted from stool using the PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Mo Bio Laboratory Inc., CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, we cut the two sections from the cards containing the stool sample and placed them into 750 μl bead solution. The fecal material in bead solution was lysed using the Powerlyzer (Mo Bio Laboratory Inc., CA) at 4500 rpm for 45 s. DNA was collected and eluted using silica columns included with the PowerLyzer PowerSoil kit. Barcoded amplicons were generated covering the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using the F515/R806 primer pair [20]. The PCR reaction was set up using FastStart High Fidelity PCR system, dNTP pack (Roche, IN) and run as follows: an initial denaturing step at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 52 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and then a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. PCR products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, IN) and quantified using the Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, CA). Amplicon libraries were pooled at equal molar concentrations and sequenced using a 300-cycle (2 × 151 bp) MiSeq reagent kit on the Illumina MiSeq platform for paired-end sequencing.

Sequence read processing

Forward and reverse reads were joined using join_paired_ends.py in QIIME [21], allowing a minimum base-pair overlap of 10 and a maximum of 20% difference in overlap region. Sequences were demultiplexed, and poor-quality sequences excluded, using the default parameters of QIIME script split_libraries_fastq.py [21]. From the 540 stool samples, we obtained 19,255,455 quality-filtered 16S rRNA gene sequence reads. Sequence reads were clustered into de novo operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% identity, and representative sequence reads for each OTU were assigned taxonomy based on fully sequenced microbial genomes (IMG/GG Greengenes), using QIIME pick_de_novo_otus.py script [21]. Chimeric sequences (identified using ChimeraSlayer [22]), sequences that failed alignment, and singleton OTUs were removed. The final dataset retained 18,617,524 sequences (mean ± SD = 34,477 ± 19,417 sequence reads/sample) and contained 221,501 OTUs.

Quality control

All samples underwent DNA extraction and sequencing in the same laboratory, and laboratory personnel were blinded to case/control status. A total of 3 sequencing batches were run: 2 for the CDC samples and 1 for the NYU samples. Quality control samples and negative controls were included across all sequencing batches. DNA from 6 stool sample repeats from 4 volunteers were included in each of 3 sequencing batches (2 CDC, 1 NYU) for a total of 72 quality control samples. In order to mimic the sample workflow of the CDC study, 1/6 of the quality control stool samples were treated with Hemoccult SENSA developer (Beckman Coulter, CA). We calculated intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the Shannon diversity index and DESeq2-normalized counts [23] of abundant bacterial phyla and genera and found the ICCs to be generally high (Additional file 1: Table S1), indicating high similarity of microbiota profiles within repeated samples from the same volunteer. Additionally, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) showed clustering of the repeated samples from each volunteer regardless of batch or developer treatment, indicating good reproducibility (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Of 9 negative controls (3 in each batch), 6 had zero sequence reads, 2 had 1 read, and 1 had 21 reads, indicating minimal laboratory contamination.

α-Diversity

Within-subject microbial diversity (α-diversity) was assessed using species richness and the Shannon diversity index, which were calculated in 500 iterations of rarefied OTU tables of 4000 sequence reads per sample. This sequencing depth was chosen to sufficiently reflect the diversity of the samples (Additional file 1: Figure S2) while retaining the maximum number of participants for the analysis (1 control excluded from this analysis due to sequencing depth = 2088). To compare α-diversity between cases and controls, we modeled richness and Shannon index as outcomes in linear regression, adjusting for age, sex, study, and categorical BMI.

Sequence read count filtering

The raw counts of 221,501 de novo OTUs were agglomerated to 13 phyla, 28 classes, 51 orders, 103 families, and 256 genera. We then filtered out low-count taxa by including only taxa with at least 2 sequence reads in at least 40 participants, resulting in inclusion of 11 phyla, 20 classes, 24 orders, 51 families, 89 genera, and 2347 OTUs (7 of which were of unassigned taxonomy); this filtered data was used in all downstream analyses described below.

Microbial community types

The stool samples were clustered into community types, or enterotypes, of similar microbial composition at the OTU level using the Dirichlet multinomial mixture (DMM) model [10, 24], implemented using the “DirichletMultinomial” package in R. Fisher’s exact test with Monte Carlo simulations was used to determine differences in community types between cases and controls.

Distances and PERMANOVA

β-Diversity (between-sample differences) was assessed at the OTU level using unweighted and weighted UniFrac phylogenetic distances [25] and the Jensen-Shannon divergence (JSD). The unweighted UniFrac considers only OTU presence or absence, while the weighted UniFrac and JSD take into account OTU relative abundance. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) [26] of the distance matrices, as implemented in the “vegan” package in R, was used to identify whether case/control status explains variation in microbial community composition, adjusting first for study, age, sex, and categorical BMI.

Differential abundance testing

We used negative binomial generalized linear models, as implemented in the “DESeq2” [23] package in R, to test for differentially abundant taxa by case/control status at phylum-genus levels and at OTU level. This method models raw count data with a negative binomial distribution and adjusts internally for “size factors” which normalize for differences in sequencing depth between samples. Models were adjusted for sex, age, categorical BMI, and study. DESeq2 default outlier replacement, independent filtering of low-count taxa, and filtering of count outliers were turned off. Taxa models with maximum Cook’s distance >10 were removed prior to p value adjustment for the false discovery rate (FDR) [27]. We considered an FDR-adjusted p value (q value) less than 0.10 as significant.

OTU correlation network

Spearman’s correlation was used to assess relationships between OTUs that were associated with case/control status. OTU counts were normalized for DESeq2 [23] size factors, to account for differences in library size in a consistent manner to our differential abundance analysis, prior to correlation analysis. Correlations were calculated independently for the groups under comparison (e.g., in control + CA samples). Correlation coefficients with magnitude ≥0.3 were selected for visualization using the “igraph” package in R.

Results

Participant characteristics

We included a total of 540 colonoscopy-screened individuals in the current analysis, composed of 323 polyp-free controls, 144 cases with CAs only, 40 cases with HPs only, and 33 cases with SSAs (with or without HPs). CA cases were more likely to be male and tended to be older than controls (Table 1). HP cases also tended to be older than controls, while SSA cases did not differ from controls in sex ratio or age. Of the CAs, 15% (n = 22) were considered advanced and 38% (n = 55) had polyps in the distal colon (Table 1). As expected, the majority of HPs were located in the distal colon (n = 34; 85%) and the majority of SSAs were located in the proximal colon (n = 30; 91%) (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Table 1.

Demographic and polyp characteristics of the study participants

| Controls | CA cases | HP cases | SSA cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 323 | 144 | 40 | 33 |

| Male, % | 47.1 | 67.4** | 52.5 | 54.5 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 61.3 ± 7.2 | 63.1 ± 6.6* | 64.4 ± 7.5* | 63.1 ± 7.0 |

| Whitea, % | 94.4 | 95.0 | 92.5 | 97.0 |

| Family history of cancerb, % | 25.2 | 29.1 | 41.0 | 25.0 |

| BMI categoryc, % | ||||

| Under or normal-weight (BMI <25 kg/m2) | 39.9 | 31.2 | 32.5 | 24.2 |

| Overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) | 38.7 | 43.1 | 42.5 | 45.5 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 21.4 | 25.7 | 25.0 | 30.3 |

| Study, % | ||||

| CDC | 75.5 | 70.1 | 60.0 | 87.9 |

| NYU | 24.5 | 29.9 | 40.0 | 12.1 |

| Polyp histologyd, % | ||||

| TA <1 cm only | 84.0 | |||

| TA ≥1 cm, TVA, or TA and TVA only | 15.3 | |||

| Hyperplastic only | 100.0 | |||

| SSA only | 81.8 | |||

| SSA and hyperplastic only | 18.2 | |||

| Polyp locatione, % | ||||

| Proximal | 60.4 | 15.0 | 90.9 | |

| Distal | 38.2 | 85.0 | 9.1 | |

CA conventional adenoma, HP hyperplastic polyp, SSA sessile serrated adenoma

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, different from controls by Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Chi-squared test for continuous or categorical variables, respectively

a n = 4 were missing race

b n = 7 were missing family history

cThose missing BMI (CDC n = 1, NYU n = 3) were re-coded as the median (CDC 27 kg/m2, NYU 25 kg/m2) in order to retain sample size in covariate adjusted analyses

d TA tubular adenoma, TVA tubulovillous adenoma, SSA sessile serrated adenoma, n = 1 subject with a TA could not be classified by size, so conventional adenoma percentage will not sum to 100%

eProximal: polyps only in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, or splenic flexure; distal: any polyp located in the descending colon, sigmoid colon, or rectum; see Additional file 1: Table S2 for further breakdown by specific location; n = 2 subjects with CAs could not be classified by location, so CA percentage will not sum to 100%

Global gut microbiota shifts in relation to colorectal polyps

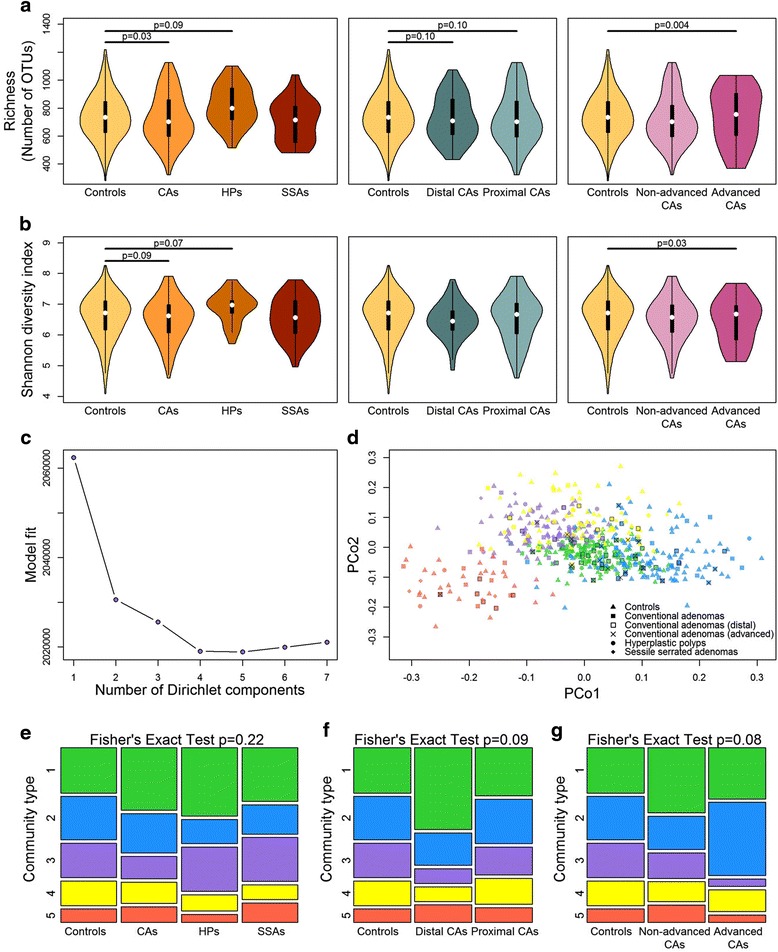

We first investigated microbial community diversity of the participants according to polyp histology and location. CA cases tended to have lower community diversity than controls (richness: p = 0.03; Shannon index: p = 0.09), a pattern that was consistent for both proximal and distal CA cases, and particularly apparent in advanced CA cases (richness: p = 0.004; Shannon index: p = 0.03) (Fig. 1a, b; Additional file 1: Table S3). Conversely, HP cases had marginally higher diversity than controls (richness: p = 0.09; Shannon index: p = 0.07), while community diversity of SSA cases did not differ from controls (richness: p = 0.96; Shannon index: p = 0.89), though sample sizes for HP and SSA groups were small.

Fig. 1.

α-Diversity and community types of colonoscopy-screened participants. a Violin plots of species richness and b Shannon diversity index by polyp histology (controls n = 322, CA cases n = 144, HP cases n = 40, SSA cases n = 33), location (distal CA n = 55, proximal CA n = 87), and advancement level (non-advanced CA n = 121, advanced CA n = 22). These indices were calculated for 500 iterations of rarefied (4000 sequences per sample) OTU tables, and the average over the iterations was taken for each participant (1 control excluded due to sequencing depth = 2088). p values from multiple linear regression are shown. c Fitting to the DMM [24, 56] model indicates optimal classification into 5 community types. d Principal coordinate analysis of Jensen-Shannon divergence values between participants, colored by community type. Green community type 1, blue type 2, purple type 3, yellow type 4, red type 5. e Distribution of the community types in groups distinguished by histology, f location, or g advancement level. p value from Fisher’s exact test with Monte Carlo simulation is shown. CAs conventional adenomas, HPs hyperplastic polyps, SSAs sessile serrated adenomas

We identified 5 microbial community types among the participants using Dirichlet multinomial mixture models [24] (Fig. 1c, d), each containing controls, CA cases, HP cases, and SSA cases. The top 20 OTUs contributing the most to the Dirichlet components are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S3; OTUs from Prevotella copri (increased normalized abundance in community type 5), Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (lower normalized abundance in community type 2), and an unclassified Bacteroides species (increased normalized abundance in community type 1) were the highest contributors. While the distribution of these community types did not differ significantly by histology (Fig. 1e; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.22), we observed a marginally significant difference in community-type distribution by CA polyp location (Fig. 1f; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.09) and by CA non-advanced or advanced classification (Fig. 1g; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.08). Compared with controls, a higher percentage of distal CA cases were members of community type 1 and fewer were members of community types 3 and 4, while a higher percentage of advanced CA cases were members of community type 2 and fewer were members of community types 3 and 5. Direct comparison of distal CA cases to controls revealed a significant difference in community type distribution between the two groups (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.01), though direct comparison of advanced CA cases to controls did not (p = 0.20).

PERMANOVA analyses of between-sample distances adjusting for covariates largely supported the findings from the community-type analyses: stool microbial composition of distal CA cases and advanced CA cases tended to differ from controls (distal vs. controls: unweighted UniFrac p = 0.02, weighted UniFrac p = 0.05, JSD p = 0.11; advanced vs. controls: unweighted UniFrac p = 0.002, weighted UniFrac p = 0.02, JSD p = 0.02), while the other case groupings (all CA cases, proximal CA cases, non-advanced CA cases, HP cases, and SSA cases) did not differ significantly from controls (all p ≥ 0.10). We did not further classify CA cases into joint location × advanced categories due to sample size restrictions (n = 7 in the distal advanced group).

Taxa associated with conventional adenomas

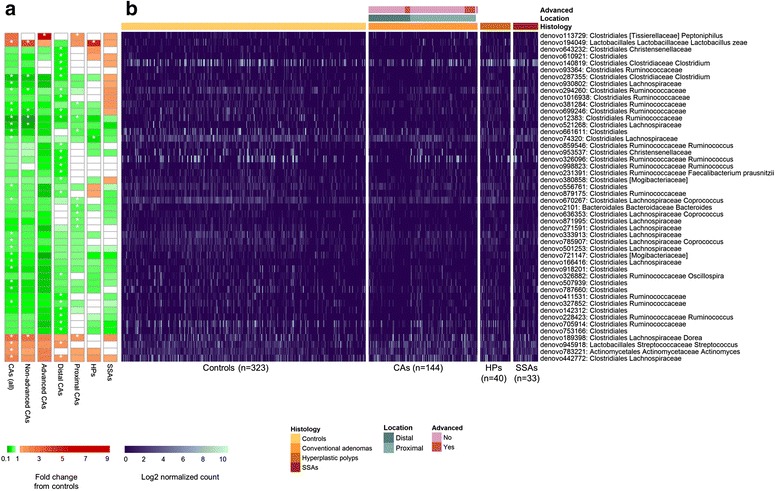

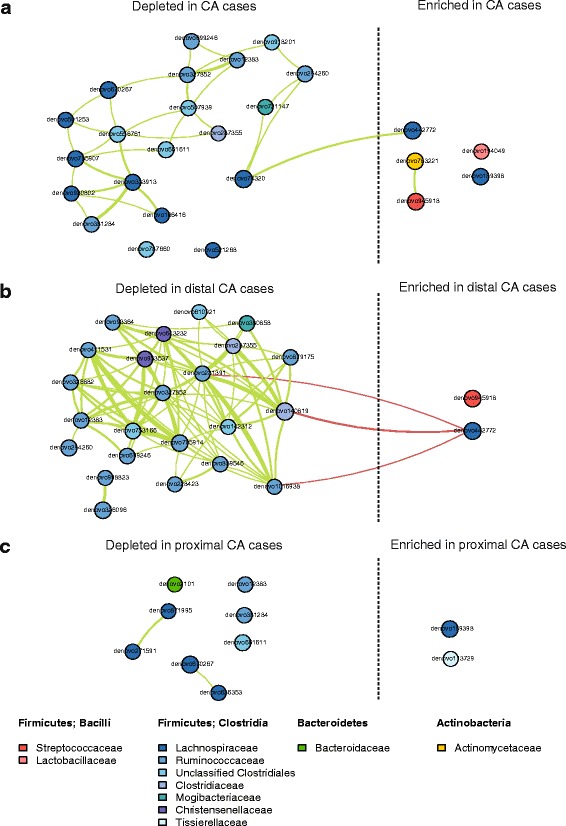

We next explored taxonomic signatures of the gut microbiota by polyp histology and location using negative binomial generalized linear models [23]. We identified 25 OTUs that were differentially abundant (q < 0.10) between CA cases and controls (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S4); 20 of these, all from class Clostridia, had decreased normalized abundance in CA cases compared to controls. Conversely, 1 OTU each from Actinomyces, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus zeae, Dorea, and an unclassified Lachnospiraceae genus had increased normalized abundance in CA cases. Many of the decreased Clostridia OTUs formed a correlation network, while the increased Actinomyces and Streptococcus OTUs were also inter-correlated (Fig. 3a). At broader levels of taxonomic classification, the observed OTU level associations manifested in an observed increased normalized abundance of class Bacilli and genera Streptococcus, Actinomyces, and Dorea in CA cases compared to controls (Table 2). Analysis of broader taxonomic classification levels also revealed that CA cases exhibited greater normalized abundance than controls of class Gammaproteobacteria, its order Enterobacteriales, and genera Corynebacterium (class Actinobacteria), Peptoniphilus, and Phascolarctobacterium (class Clostridia), and decreased normalized abundance of genus Coprobacillus (class Erysipelotrichi), and unknown genera within family Mogibacteriaceae (class Clostridia) and order RF39 (class Mollicutes) (Table 2; Additional file 1: Table S5).

Fig. 2.

Heatmaps of OTUs that were differentially abundant between colorectal polyp cases and controls. All OTUs with q < 0.10 for comparisons of any case group (all CA, non-advanced CA, advanced CA, distal CA, proximal CA, HP, SSA) vs. controls are included in the figure. a Heatmap shows fold change from controls in the DESeq2 models, with white star indicating q < 0.10 for the comparison. b Heatmap shows OTU counts in each participant. For display, counts were normalized for DESeq2 size factors and log2 transformed after adding a pseudocount of 1. n = 1 and n = 2 CA cases were missing advanced status or location information, respectively. CAs conventional adenomas, HPs hyperplastic polyps, SSAs sessile serrated adenomas

Fig. 3.

Microbial community ecology in controls and conventional adenoma cases. Correlation network of OTUs differentially abundant between a controls and all CA cases, b controls and distal CA cases, and c controls and proximal CA cases. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were estimated using counts (normalized for DESeq2 size factors) and calculated among the samples under comparison. Lines shown between OTUs indicate Spearman’s correlation ≥0.3 (green) or ≤-0.3 (red). Direction of enrichment in relation to all CA/distal CA/proximal CA cases vs. controls was determined from DESeq2 models. OTUs are colored according to family membership. Line thickness represents strength of the correlation, in steps of 0.3–0.4 (thinnest), 0.4–0.5, 0.5–0.6, 0.6–0.7, and >0.7 (thickest). CA conventional adenoma

Table 2.

Differentially abundanta classes and genera between controls and CA cases, HP cases, and SSA cases

| CA cases vs. controls | HP cases vs. controls | SSA cases vs. controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Mean countb | Fold change (95% CI) | q c | Fold change (95% CI) | q c | Fold change (95% CI) | q c |

| Class | |||||||

| Firmicutes; Bacilli | 506.3 | 2.11 (1.6, 2.78) | 2.45E−06 | 1.23 (0.78, 1.94) | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.49, 1.3) | 0.79 |

| Firmicutes; Erysipelotrichi | 305.8 | 0.92 (0.79, 1.07) | 0.57 | 1.1 (0.85, 1.41) | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.52, 0.89) | 0.09 |

| Proteobacteria; Gammaproteobacteria | 394.4 | 1.81 (1.19, 2.76) | 0.04 | 0.32 (0.16, 0.63) | 0.02 | 0.43 (0.21, 0.88) | 0.18 |

| Genus | |||||||

| Actinobacteria; Actinobacteria; Actinomycetales; Actinomycetaceae; Actinomyces | 9.1 | 1.69 (1.32, 2.17) | 0.0006 | 1.24 (0.82, 1.87) | 0.99 | 1.07 (0.7, 1.64) | 0.98 |

| Actinobacteria; Actinobacteria; Actinomycetales; Corynebacteriaceae; Corynebacterium | 1.0 | 3.73 (1.88, 7.4) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.28, 2.22) | 0.99 | 0.86 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.98 |

| Firmicutes; Bacilli; Lactobacillales; Streptococcaceae; Streptococcus | 422.2 | 2.38 (1.76, 3.21) | 1.35E−06 | 1.26 (0.78, 2.05) | 0.99 | 0.72 (0.43, 1.21) | 0.65 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; NA; NAd | 2624.0 | 1.44 (1.26, 1.65) | 6.31E−06 | 1.18 (0.94, 1.47) | 0.92 | 0.98 (0.77, 1.25) | 0.98 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; [Mogibacteriaceae]; NAd | 16.2 | 0.78 (0.65, 0.94) | 0.06 | 0.85 (0.63, 1.15) | 0.99 | 0.89 (0.65, 1.22) | 0.88 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; [Tissierellaceae]; Peptoniphilus | 1.6 | 3.41 (1.83, 6.35) | 0.002 | 0.55 (0.21, 1.46) | 0.99 | 0.85 (0.32, 2.28) | 0.98 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Lachnospiraceae; Anaerostipes | 45.7 | 1.23 (0.98, 1.54) | 0.30 | 1.96 (1.36, 2.84) | 0.03 | 1.02 (0.69, 1.52) | 0.98 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Lachnospiraceae; Dorea | 216.1 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | 0.06 | 1.09 (0.88, 1.34) | 0.99 | 1 (0.8, 1.25) | 0.99 |

| Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Veillonellaceae; Phascolarctobacterium | 115.4 | 1.91 (1.24, 2.96) | 0.04 | 1.12 (0.57, 2.22) | 0.99 | 0.85 (0.41, 1.76) | 0.98 |

| Firmicutes; Erysipelotrichi; Erysipelotrichales; Erysipelotrichaceae; Coprobacillus | 10.8 | 0.59 (0.39, 0.88) | 0.07 | 0.36 (0.19, 0.68) | 0.07 | 1.03 (0.53, 2.01) | 0.98 |

| Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria; Burkholderiales; Alcaligenaceae; Sutterella | 430.2 | 2.06 (1.52, 2.78) | 8.60E−05 | 0.84 (0.52, 1.37) | 0.99 | 0.97 (0.58, 1.65) | 0.98 |

| Tenericutes; Mollicutes; RF39; NA; NAd | 36.4 | 0.42 (0.22, 0.78) | 0.06 | 1.1 (0.44, 2.77) | 0.99 | 1.06 (0.4, 2.81) | 0.98 |

CA, conventional adenoma, HP hyperplastic polyp, SSA sessile serrated adenoma

aDifferential abundance was detected by the “DESeq” function in the DESeq2 package. All classes and genera with an FDR-adjusted q < 0.10 are included in the table. Models were adjusted for sex, age, study, and categorical BMI. See Additional file 1: Table S5 for comparisons at the phylum, order, and family level

bCounts were normalized by dividing raw counts by DESeq2 size factors

cFDR-adjusted p value. FDR adjustment was conducted at each level (i.e., class, genus) separately

dNA: unclassified genus

CAs were further classified as proximal (n = 87) or distal (n = 55) and as non-advanced (n = 121) or advanced (n = 22), in order to explore taxonomic signatures associated with these sub-groups. Many OTUs from class Clostridia had decreased normalized abundance in distal CA cases compared to controls, including OTUs from families Ruminococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, Christensenellaceae, and Mogibacteriaceae (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S6). These OTUs formed a positive correlation network with each other (Fig. 3b). One OTU from Streptococcus and one from Lachnospiraceae had increased normalized abundance in distal CA cases, and the OTU from Lachnospiraceae was inversely correlated with several of the decreased Clostridia OTUs (Fig. 3b). These OTU level associations manifested in associations at broader taxonomic levels, including significantly decreased normalized abundance of class Clostridia and families Mogibacteriaceae, Christensenellaceae, and Clostridiaceae in distal CA cases compared to controls (Additional file 1: Table S6). Proximal CA cases also had some differentially abundant OTUs from controls, including Dorea and Peptoniphilus OTUs (increased normalized abundance in proximal CA cases), and Bacteroides, Coprococcus, and unclassified Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae OTUs (decreased normalized abundance in proximal CA cases) (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S6); most of these OTUs were uncorrelated with one another (Fig. 3c). Analysis at broader levels of taxonomic classification revealed additional differences between proximal CA cases and controls that were not all apparent at the OTU level; similar to the all CA case analysis, proximal CA cases exhibited greater normalized abundance than controls of classes Bacilli and Gammaproteobacteria, order Enterobacteriales, and genera Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, Dorea, Peptoniphilus, and Phascolarctobacterium, among others (Additional file 1: Table S6).

Although the overall microbiota composition of advanced CA cases was significantly different from controls in the global analysis, we observed only one differentially abundant OTU (from genus Peptoniphilus, q < 0.10) between advanced CA cases and controls (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S7); this is likely an issue of low power as the sample size of advanced CA cases was small (n = 22). However, both non-advanced and advanced CA cases exhibited similar directions of fold change in OTU normalized abundance from controls (Fig. 2), indicating similarity between the two groups. At broader taxonomic classification levels, advanced CA cases exhibited greater normalized abundance than controls of genera Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Peptoniphilus, Porphyromonas, and Haemophilus and lower normalized abundance than controls of genera Lachnospira, Lachnobacterium, and unclassified genera from Mogibacteriaceae, Christensenellaceae, and RF39 (Additional file 1: Table S7). Non-advanced CA cases, making up the majority of all CA cases, exhibited similar differentially abundant taxa from controls as in the all CA case analysis.

Taxa associated with hyperplastic polyps and SSAs

We identified few differentially abundant taxa between HP cases or SSA cases and controls (q < 0.10). HP cases had increased normalized abundance of Lactobacillus zeae and decreased normalized abundance of an unidentified OTU in family Lachnospiraceae (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S4). HP cases also had decreased normalized abundance of class Gammaproteobacteria, order Enterobacteriales, and genus Coprobacillus and increased normalized abundance of genus Anaerostipes, compared to controls (Table 2; Additional file 1: Table S5). SSA cases had decreased normalized abundance of class Erysipelotrichi (Table 2); however, no other taxa (phylum-genus levels or OTU level) were identified as differentially abundant (q < 0.10) between SSA cases and controls.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted our main analysis excluding participants (n = 5) who collected their stool sample <2 weeks after their colonoscopy, in order to ensure results were not biased by effects of colon preparation and colonoscopy on the microbiota (Additional file 1: Table S8). We also conducted our main analysis excluding participants who had taken antibiotics within 30 days prior to sample collection (n = 19 from the NYU study), in order to ensure results were not biased by effects of antibiotics on the microbiota (antibiotic usage information was not available in the CDC study) (Additional file 1: Table S9). Excluding these participants groups did not substantially impact findings.

Discussion

In this large study of colonoscopy-screened adults, we found that CA-associated changes in gut microbiota diversity and composition in relation to controls depended on the severity and location of the adenoma. More specifically, advanced CA cases had the greatest reduction in community diversity compared to controls, while distal or advanced CA cases differed significantly in microbiota composition from controls. Such differences were not observed for subjects with hyperplastic polyps or SSAs. Our results indicate that gut bacteria may play distinct roles in the development of site-specific histologically different polyp types. To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously consider different polyp histologies and locations and the largest study of the gut microbiota and colorectal polyps to date.

Our finding of reduced species richness and diversity in CA cases, particularly advanced CA cases, is consistent with observations in CRC from our group in the USA [9] and from another group in China [28]. Decreased gut microbial diversity, often observed in other diseases including obesity [29] and inflammatory bowel diseases [30, 31], is likely indicative of underlying bacterial dysbiosis, possibly due to domination by opportunistic pathogenic bacteria and/or loss of commensal bacteria. While other reports of colorectal polyp [32–35] and cancer [10, 36–38] showed mixed results in regard to community diversity, including findings of no differences in diversity or increased diversity in cases, sample sizes for these studies were small (N for cases ranged from 7 to 53). These differing results may be related to limited power or to the specific bacterial drivers or pathogens present in each unique study population.

Our observation of global OTU-level composition shifts in distal, but not proximal, CA cases compared to controls is likely due to stool being a better proxy for the bacterial communities of the distal colon than of the proximal colon [39]. This was proposed in a recent metagenomic study of colorectal cancer, in which carcinoma-associated bacterial genes were more abundant in stool of distal CRC cases than proximal CRC cases [10]. Additionally, there is evidence that mucosal bacterial biofilms play a role in proximal, but not distal, CRCs [40], further suggesting that bacteria are involved in proximal tumor formation, but that stool may be an inappropriate sample to test their involvement. However, despite the lack of global OTU-level shifts in proximal CA cases compared to controls, we did observe a taxonomic signature for proximal CA cases at broader levels of taxonomic classification; further, this signature differed from that of distal CA cases. This finding suggests that the role bacteria play in CA development may differ between proximal and distal colon sites. There are known molecular distinctions between proximal and distal CRCs, most notably that proximal CRCs are more likely to be hypermethylated and to have elevated mutation rates [41]. Additionally, the luminal environment differs between proximal and distal colon sites: there are high levels of easily fermentable carbohydrate substrates in the proximal colon, which decrease distally through the colon [39, 42]; the mucus layer increases in thickness distally through the colon [42]; the number of bacterial cells increases distally through the colon [43]; and immune activity decreases distally through the colon [44]. These differences can result in site-specific bacterial communities and processes, which may contribute to CA development in distinct ways.

A major shift in stool microbiota composition observed for CA cases was the depleted normalized abundance of a network of Clostridia OTUs from families Ruminococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Lachnospiraceae; this was particularly apparent in distal CA cases, in which the class Clostridia was significantly depleted. Members of these Clostridia families have in common the capacity to generate butyrate from fermentation of non-digestible plant fibers [45], which is beneficial to colonic health [46]. Depletion of butyrate-producing bacteria in the distal colon, where carbohydrate substrate supply is already compromised [39, 42], may allow for adenoma growth. The decreased normalized abundance of Clostridia we have observed here is consistent with our previous study of CRC, in which the relative abundance of class Clostridia was depleted in stool samples of CRC cases compared to controls [9]. Other studies have also found decreased relative abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria in adenoma [33, 47, 48] and CRC [36, 37], supporting the protective effects of butyrate against CRC.

The taxonomic signature of proximal CA cases was not apparent at the OTU-level, though distinct patterns emerged at broader levels of taxonomic classification; this is perhaps because the stool microbiota are a poor proxy for the microbiota of the proximal colon, thus reducing power to detect OTU-level differences between proximal CA cases and controls. Proximal CA cases exhibited greater normalized abundance than controls of classes Bacilli and Gammaproteobacteria, order Enterobacteriales, and genera Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, Dorea, Peptoniphilus, and Phascolarctobacterium; some of these bacteria may be candidate drivers of the CA pathway in the proximal colon. Some results from other studies are similar to these findings (though none of these studies have distinguished adenomas by location): the genera Dorea [48], Phascolarctobacterium [48], and Streptococcus [32, 33, 49], as well as genera within the Enterobacteriaceae family of Gammaproteobacteria [32, 34, 35, 48, 49], were elevated in mucosal or stool samples from adenoma cases compared to controls. Additionally, the Enterobacteriaceae family and Actinomycetales order have been highlighted as potential CRC driver bacteria, based on their over-representation in off-tumor compared to on-tumor paired samples from CRC patients [12]. Members of Enterobacteriaceae are known to cause inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract and could contribute to CRC via inflammatory mechanisms [12, 50]. Interestingly, a recent report on CRCs found that invasive polymicrobial bacterial biofilms were a key feature of proximal colon tumors, but not distal tumors [40]. This study implicated the organization, rather than composition, of mucosal communities in proximal CRC development. It will be important for future studies to examine the mucosal communities of proximal CAs and to determine the microbial organizational and/or compositional factors associated with their presence.

The observation that the stool microbial composition of SSA cases was similar to that of controls was unexpected, since an animal model [51] and human study [52] suggest involvement of host microbiota in serrated polyp development. We did observe a decrease in the Erysipelotrichi class in SSA cases; this class has been associated with colon mucus barrier impenetrability in mice [53] and may play a protective role in SSA development. Our lack of other findings is likely related to low power due to the small sample size of SSA cases and the proximal location of SSAs. Another potential explanation for this finding is the possibility that bacteria may initiate CRC via a mechanism related to the conventional pathway, but not serrated pathway, such as by inducing chromosomal instability [54].

Strengths of this study include the large sample size, the histologic and location classification of polyps for all cases, the inclusion of polyp-free controls, and the comprehensive bacterial profiling using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. However, this study also has several limitations. We did not examine colorectal mucosal samples; while easily obtainable stool samples are important for developing tools for risk stratification and screening for CRC [38, 47], mucosal samples are important from a prevention standpoint, as they allow for better identification of bacteria associated with adenoma. Assessment of differences in the stool microbiota between polyp cases and polyp-free controls may provide insight into systematic differences in the gut microbiota between these groups that may contribute to polyp development. Future studies incorporating mucosal samples will be able to better pinpoint specific mucosal-associated bacteria responsible for polyp initiation and growth. Further limitations are the mostly white study population, limiting generalizability to other racial groups, the lack of antibiotic usage information in the CDC study, and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to establish the temporality of the bacteria-adenoma relationship.

Conclusions

Due to the different molecular origins and etiologies of CRC, which may vary by colon site [44], it is critically important to consider that the role bacteria play in adenoma development may differ by polyp histology and location, as our results suggest. Although evidence is mounting for a role of driver bacteria in colorectal carcinogenesis, it is likely that different bacterial drivers can confer the same risk for CRC [12]. Bacterial drivers may differ between patients and populations and between polyp histologies and locations. The possibility that there are multiple population-specific, histology-specific, and site-specific bacterial drivers of CRC highlights the need for additional, larger studies in different populations, taking into consideration polyp histology and location, in order to fully characterize the broad array of potential bacterial drivers of CRC, as well as potential protective bacteria, and to identify their functions. Identification of the bacterial drivers of CRC may lead to development of targeted prophylactic therapies. Identification of beneficial bacteria depleted in adenomas may lead to implementation of dietary interventions or probiotic/prebiotic therapies to promote their regrowth and recolonization [55]. Thus, continued study of the early stages of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence may lead to actionable means for CRC prevention.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the US National Cancer Institute under award numbers R01CA159036, U01CA182370, R01CA164964, R03CA159414, P30CA016087, and R21CA183887 and by AACR/Pancreas Cancer Action Network Career Development Award.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and will be submitted to the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP).

Authors’ contributions

JA, RBH, JAS, TRC, and GM planned the study. JA, RBH, JAS, TRC, and GM collected the data. BAP, CD, and JW conducted the study. BAP, JA, and RBH interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. BAP, JA, RBH, JAS, TRC, and GM revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. BAP, CD, JAS, TRC, GM, JW, EY, HF, IL, JS, CF, RBH, and JA approved the final draft submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies described in this manuscript were approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) of the University of Minnesota, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the NYU School of Medicine, and all participants provided written informed consent (IRB study number: i12-00855).

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Additional file

Figure S1. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances for quality control stool specimens. Figure S2. Rarefaction curves of richness and the Shannon index. Figure S3. Count heatmap of top 20 OTUs contributing the most to the Dirichlet components of the Dirichlet multinomial mixture model. Table S1. Quality control intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) and 95% CIs for the Shannon index and normalized counts of selected phyla and genera. Table S2. Number of participants with polyp(s) in the specified colon locations, stratified by assignment into case type and polyp location groupings used in analysis. Table S3. Richness and Shannon diversity index by group. Table S4. Differentially abundant OTUs between controls and conventional adenoma cases, hyperplastic polyp cases, or SSA cases. Table S5. Differentially abundant taxa (phylum‐genus levels) between controls and conventional adenoma cases, hyperplastic polyp cases, or SSA cases. Table S6. Differentially abundant taxa (phylum‐OTU level) between controls and proximal or distal conventional adenoma cases. Table S7. Differentially abundant taxa (phylum‐OTU level) between controls and non‐advanced or advanced conventional adenoma cases. Table S8. Sensitivity analysis—excluding participants (n = 5) who collected their stool sample <2 weeks after their colonoscopy. Table S9. Sensitivity analysis—excluding participants (n = 19 from the NYU study) who had taken antibiotics within 30 days prior to sample collection (antibiotic usage information was not available in the CDC study). (PDF 631 kb)

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langner C. Serrated and non-serrated precursor lesions of colorectal cancer. Dig Dis. 2015;33:28–37. doi: 10.1159/000366032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2088–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strum WB. Colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1065–1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1513581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keku TO, Dulal S, Deveaux A, Jovov B, Han X. The gastrointestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G351–G363. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00360.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zackular JP, Baxter NT, Iverson KD, Sadler WD, Petrosino JF, Chen GY, et al. The gut microbiome modulates colon tumorigenesis. MBio. 2013;4:e00692–00613. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00692-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter NT, Zackular JP, Chen GY, Schloss PD. Structure of the gut microbiome following colonization with human feces determines colonic tumor burden. Microbiome. 2014;2:20. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J, Shi J, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, Stadlmayr A, Tang L, Lan Z, et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6528. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakatsu G, Li X, Zhou H, Sheng J, Wong SH, Wu WK, et al. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8727. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tjalsma H, Boleij A, Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irrazabal T, Belcheva A, Girardin SE, Martin A, Philpott DJ. The multifaceted role of the intestinal microbiota in colon cancer. Mol Cell. 2014;54:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang T, Owen JL, Lightfoot YL, Kladde MP, Mohamadzadeh M. Microbiota impact on the epigenetic regulation of colorectal cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis P, Hold GL, Flint HJ. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:661–672. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond JH. Polyp guideline: diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance for patients with colorectal polyps. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3053–3063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominianni C, Wu J, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Comparison of methods for fecal microbiome biospecimen collection. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha R, Chen J, Amir A, Vogtmann E, Shi J, Inman KS, et al. Collecting fecal samples for microbiome analyses in epidemiology studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:407–416. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song SJ, Amir A, Metcalf JL, Amato KR, Xu ZZ, Humphrey G, et al. Preservation methods differ in fecal microbiome stability, affecting suitability for field studies. mSystems. 2016;1(3):e00021–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.112730.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes I, Harris K, Quince C. Dirichlet multinomial mixtures: generative models for microbial metagenomics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Kelley ST, Knight R. Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1576–1585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01996-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McArdle BH, Anderson MJ. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology. 2001;82:290–297. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0290:FMMTCD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B-Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huipeng W, Lifeng G, Chuang G, Jiaying Z, Yuankun C. The differences in colonic mucosal microbiota between normal individual and colon cancer patients by polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:138–144. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a26719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55:205–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez C, Antolin M, Santos J, Torrejon A, Casellas F, Borruel N, et al. Unstable composition of the fecal microbiota in ulcerative colitis during clinical remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:643–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mira-Pascual L, Cabrera-Rubio R, Ocon S, Costales P, Parra A, Suarez A, et al. Microbial mucosal colonic shifts associated with the development of colorectal cancer reveal the presence of different bacterial and archaeal biomarkers. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen HM, Yu YN, Wang JL, Lin YW, Kong X, Yang CQ, et al. Decreased dietary fiber intake and structural alteration of gut microbiota in patients with advanced colorectal adenoma. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1044–1052. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.046607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanapareddy N, Legge RM, Jovov B, McCoy A, Burcal L, Araujo-Perez F, et al. Increased rectal microbial richness is associated with the presence of colorectal adenomas in humans. Isme j. 2012;6:1858–1868. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goedert JJ, Gong Y, Hua X, Zhong H, He Y, Peng P, et al. Fecal microbiota characteristics of patients with colorectal adenoma detected by screening: a population-based study. EbioMedicine. 2015;2(6):597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu N, Yang X, Zhang R, Li J, Xiao X, Hu Y, et al. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients. Microb Ecol. 2013;66:462–470. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weir TL, Manter DK, Sheflin AM, Barnett BA, Heuberger AL, Ryan EP. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:766. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane LE. Acquisition, evolution and maintenance of the normal gut microbiota. Dig Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):90–98. doi: 10.1159/000268127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dejea CM, Wick EC, Hechenbleikner EM, White JR, Mark Welch JL, Rossetti BJ, et al. Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406199111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Koropatkin NM, Cameron EA, Martens EC. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. J AOAC Int. 2012;95:50–60. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.SGE_Macfarlane. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee GH, Malietzis G, Askari A, Bernardo D, Al-Hassi HO, Clark SK. Is right-sided colon cancer different to left-sided colorectal cancer?—a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vital M, Howe AC, Tiedje JM. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. MBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00889-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:235–243. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zackular JP, Rogers MA, Ruffin MT, Schloss PD. The human gut microbiome as a screening tool for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:1112–1121. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall T, Burcal L, Mpande CN, Jenkins N, et al. Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:138–147. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geng J, Song Q, Tang X, Liang X, Fan H, Peng H, et al. Co-occurrence of driver and passenger bacteria in human colorectal cancer. Gut Pathog. 2014;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terzic J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–2114.e2105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bongers G, Pacer ME, Geraldino TH, Chen L, He Z, Hashimoto D, et al. Interplay of host microbiota, genetic perturbations, and inflammation promotes local development of intestinal neoplasms in mice. J Exp Med. 2014;211:457–472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ito M, Kanno S, Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Jakobsson HE, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Schutte A, Ermund A, Boysen P, Bemark M, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota shapes the colon mucus barrier. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:164–177. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pino MS, Chung DC. The chromosomal instability pathway in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2059–2072. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dominianni C, Sinha R, Goedert JJ, Pei Z, Yang L, Hayes RB, et al. Sex, body mass index, and dietary fiber intake influence the human gut microbiome. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014;509:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nature13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and will be submitted to the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP).