Abstract

Objectives

Rural smokers are more likely to be uninsured and live in poverty, which may pose significant cost barriers to accessing smoking cessation medications. As part of a randomized clinical trial, we provided support to connect low-income smokers with the use of pharmaceutical assistance programs (PAPs) to improve medication access.

Methods

Study participants were rural smokers enrolled in a randomized clinical trial testing in-office telemedicine versus telephone-based approaches to deliver counseling sessions. For potentially qualified participants, we developed a system to connect them with PAPs that provided smoking cessation medications at low or no cost. Participants reported medication utilization 3 and 6 months after randomization.

Results

Of the 560 study participants, 312 (55.7%) met initial screening criteria for PAP eligibility. Of those eligible, 104 (33.3%) initiated a PAP application, with 49 (15.7%) completing the application and ultimately receiving medications through the programs. Despite the availability of assistance with the PAP application process, overall medication use among those that were eligible for PAP was significantly lower than among participants with higher incomes or access to prescription insurance (60.4% vs. 51.3%; P = 0.04). Abstinence among PAP-eligible smokers was also lower at the 3-month follow-up (P = 0.01), but this difference was not present at the 6- and 12-month follow-up surveys.

Conclusion

With substantial assistance, some low-income smokers without prescription insurance can get effective smoking cessation medications through PAPs, but overall access remains worse than among those with higher incomes or prescription insurance.

Tobacco use is a chronic condition that in 2012 affected 24.2% of Americans with income levels of 200% Federal Poverty Level (FPL) or lower.1 Although smoking cessation pharmacotherapy is highly recommended,2 relatively few smokers wanting to quit actually use medications.3 Rural smokers are more likely to have low income, lack health insurance,4 and have reported that the cost of smoking cessation medications is a barrier to accessing treatment.5

Many pharmaceutical companies offer patient assistance programs to enable low-income smokers who lack prescription drug coverage to obtain medications for little or no cost.6,7 However, the complexity of the application process and variability in program enrollment criteria create barriers to accessing medication through these programs.9 As a result, there is limited evidence demonstrating that medication assistance programs lead to positive health outcomes.8 It is possible that underserved (rural) smokers who desire to quit and would like to use pharmacotherapy might benefit from pharmaceutical assistance programs (PAPs) to access smoking cessation medications.

As part of a clinical trial testing two behavioral intervention approaches to assist smoking cessation in rural Kansas,10,11 we implemented a protocol to help smokers acquire smoking cessation medications through PAP. In the present report, we detail our approach to helping participants enroll in PAP and the relative success of our efforts in helping participants complete the necessary paperwork and ultimately receive free or reduced-price smoking cessation medications.

Methods

Study participants were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of 560 rural smokers who received four counseling sessions over a period of 3 months. Smokers received patient-centered cessation counseling either within their primary care physician’s office with the use of video-based telemedicine or through telephone-based counseling calls delivered outside the physician’s office. In short, Connect2Quit was designed to compare the standard-of-care counseling approach for smoking cessation, i.e., telephone calls, with counseling using video-based telemedicine integrated at the patient’s provider’s office. Participants were referred by clinic personnel or recruited on site by medical students from 20 rural primary care practices and safety net clinics. Community-based efforts were also conducted to recruit Latino smokers. Participants were 18 years of age or older, had a physician who was part of the study, spoke English or Spanish, and had a telephone. All participants received four counseling sessions.10,11 The University of Kansas Medical Center Ethics Committee approved all study procedures. More details of the trial have been published previously.10,11

Participants did not receive free smoking cessation medications as part of the randomized trial,10 so a system to assist them in obtaining medications through their health insurance or a PAP was established. At baseline, study personnel collected information on insurance coverage, income, prescription medication use, and potential contraindications to smoking cessation medications use.10 If the participant’s insurance program did not cover smoking cessation medications or the patient did not have insurance, counselors provided information on PAPs following the process that is described below.

PAP-eligible participants

Participants with income levels under 400% FPL were eligible for PAP if they also: 1) did not have any kind of health insurance, 2) had insurance that did not provide prescription drug coverage, or 3) had prescription drug coverage that did not cover smoking cessation medications. Counselors assisted patients in applying for pharmaceutical assistance from one of three programs. Pfizer Connection to Care provided assistance to obtain varenicline, nicotine inhaler, or nicotine nasal spray at no cost. Glaxo-Smith-Kline (GSK) Bridges to Access provided bupropion SR for a nominal copay of $10. Together Rx (www.togetherrxaccess.com) provided participants with a discount card that could be used at the pharmacy counter. Pfizer Connection to Care, GSK Bridges to Access, and Together Rx were available for individuals with incomes below 200%, 250%, and 400% FPL, respectively.

Assistance process

Study counselors identified PAP-eligible participants and assisted them in answering questions and faxing or mailing the application forms and a list of accepted proofs of income; for Together Rx, our counselors were able to complete the application during the counseling session. Clinic staff with PAPs already in place also assisted patients in completing and submitting applications. Required documentation for Pfizer Connection to Care and GSK Bridges to Access included proof of income, a prescription for the selected medication, and application forms completed and signed by their health care provider. For patients from clinics that did not provide assistance, study counselors guided patients through the application process. Participants in the video-based telemedicine and telephone-based arms were called 7 and 10 days, respectively, after initiating the application process with the study counselor to troubleshoot the PAP paperwork. Finally, after participants had mailed the required documentation to the study offices, our staff reviewed the final application packets for completeness and forwarded the completed application to the PAP.

Once applications were approved at the pharmaceutical company, Pfizer Connection to Care shipped medications to provider’s office, while GSK Bridges to Access provided a voucher to buy bupropion SR treatment for 60 days directly from a local pharmacy for a $10 copay. The Together Rx cards were sent directly to patients’ home addresses. Three weeks after the application was completed and mailed to the pharmaceutical company, personnel followed up with participants to determine if they received the pharmacotherapy, voucher, or discount card.

Outcome measures

We tracked the number of PAP-eligible participants who initiated the application process and those who ultimately were connected with medication based on self-report or PAP report when the participant was not available for follow-up calls.

As secondary outcome measures, all participants were asked, as part of 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires, if they had used any form of smoking cessation medications, the type of medication used, and whether or not they had quit smoking during the preceding 3 months.

Participant characteristics

Baseline information included age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, number of children younger than 12 years living in household, health and prescription insurance, income, and employment status. Number of cigarettes smoked per day, importance to quit smoking, and past use of smoking cessation medications were also collected at baseline.

Analysis

Trial participants are characterized as PAP eligible or noneligible participants and, among those who are PAP eligible, whether they initiated the application process or not. Participation in PAP, demographics, and smoking history characteristics are presented as frequencies and percentages. We compared the proportion of patients who reported using cessation medications, the types of medications used, the duration of medication use, and verified abstinence rates across these three groups. Information on medication utilization was collected at 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires. We collapsed these to a single end point of smoking cessation medication use at either time because participants could decide to begin pharmacotherapy at any time during the counseling sessions.

Information was examined comparing PAP eligible versus PAP noneligible and PAP eligible who initiated the application versus PAP eligible who did not initiated the application. For each set of comparisons we used chi-square and t tests to compare proportions and means, respectively, between groups. The limited sample size precluded multivariable modeling. Data was analyzed with the use of SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and statistical significance for all analysis was considered at a P value of 0.05.

Results

Of the 560 study subjects enrolled in the parent trial, 312 (55.7%) were eligible for PAP based on their income and insurance status. There were a number of important demographic differences noted between those eligible for PAP and those not eligible. PAP-eligible smokers were more likely to be younger, nonwhite, and not married (Table 1). Consistent with the income requirements, PAP eligible participants were less likely to be employed full time, had a lower hourly income, and were less likely to have medical or prescription medication insurance. They also had more children younger than 12 years at home. PAP-eligible participants were less likely to have tried varenicline or bupropion SR previously, but there were no significant differences in use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products, including nicotine gum, lozenge, and patch (Table 1). Among the PAP-eligible participants, 4.5% had income from 250% to 400% FPL and were eligible for only the Together Rx discount card; the rest were eligible for all of the PAPs.

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics

| Characteristic | PAP noneligible (n = 248) | PAP eligible (n = 312) | PAP eligible | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application initiated (n = 104) | Application not initiate (n = 208) | |||

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 50.3 ± 12.0a | 45.1 ± 13.1a | 45.4 ± 13.3 | 45.0 ± 13.1 |

| Gender male, n (%) | 94 (37.9) | 103 (33.0) | 39 (37.5) | 64 (30.8) |

| Race white, n (%) | 218 (87.9)a | 246 (78.8)a | 79 (76.0) | 167 (80.6) |

| Ethnicity Latino, n (%) | 16 (6.5) | 34 (11) | 13 (12.5) | 21 (10.0) |

| Married, n (%) | 137 (55.2)a | 101 (32.5)a | 34 (32.7) | 67 (31.9) |

| High school or more education, n (%) | 208 (83.9) | 242 (77.6) | 80 (76.9) | 162 (77.9) |

| Kids <12 y old in household, mean ± SD | 0.36 ± 0.76a | 0.68 ± 1.19a | 0.78 ± 1.41 | 0.64 ± 1.07 |

| Hourly income, $, mean ± SD | 18.20 ± 8.82a | 14.45 ± 5.89a | 14.33 ± 5.64 | 14.51 ± 6.02 |

| Health insurance for most medical care, n (%) | 237 (95.6)a | 115 (36.9)a | 31 (29.8) | 84 (40.4) |

| Prescription drug coverage, n (%) | 231 (93.1)a | 89 (28.6)a | 25 (24) | 64 (30.9) |

| Full-time employment, n (%) | 115 (46.4)a | 118 (37.9)a | 34 (32.7) | 84 (40.6) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day, mean ± SD | 20.58 ± 10.53 | 19.07 ± 10.03 | 19.04 ± 9.23 | 19.08 ± 10.42 |

| Importance to quit smoking (scale 0–10), mean ± SD | 9.15 ± 1.73a | 9.57 ± 1.23a | 9.53 ± 1.20 | 9.58 ± 1.25 |

| Prior smoking cessation medications, n (%) | ||||

| Varenicline | 93 (37.5)a | 72 (23.2)a | 28 (26.9) | 44 (21.4) |

| Nicotine patch | 129 (52) | 155 (49.8) | 53 (51) | 102 (49.3) |

| Nicotine gum | 83 (33.5) | 102 (32.8) | 31 (29.8) | 71 (34.3) |

| Nicotine lozenge | 26 (10.5) | 35 (11.3) | 14 (13.5) | 21 (10.1) |

| Bupropion | 85 (34.3)a | 77 (24.8)a | 28 (26.9) | 49 (23.7) |

Abbreviation used: PAP, pharmaceutical assistance program.

Difference significant at P <0.05 for comparison between those not eligible and eligible for PAP. Among those eligible for PAP, there were no significant differences across these baseline statistics.

One-third (33.3%) of those smokers who were identified as PAP eligible at baseline decided to initiate the application process. Of these, 54 completed and 50 failed to complete the process (Appendix 1). The average rating of importance to quit completely was 9.6 among PAP-eligible participants who where connected with medication, and 9.5 among PAP-eligible participants who initiated the application process but were not connected with medication (P = 0.56). Among PAP-eligible participants who where connected with medication, five applications were denied mainly because the proof of income that was provided was not accepted by the company. Ultimately, 49 participants—nearly one-half of those PAP eligible who initiated the application process (47.1%)—obtained medication, a voucher, or a discount card. For the 49 patients who were connected with medication, 27 applications (55.0%) were processed by study personnel and 22 (44.9%) were processed by staff at clinics that had PAPs already in place.

Most of the smokers who obtained medications through a PAP did so through Pfizer Connection to Care, and the medication most commonly obtained was varenicline (n = 31; 62.0%). In contrast, fewer applications were completed for the discount program TogetherRx (14.8%) and GSK Bridges to Access for bupropion SR (7.3%); bupropion SR was removed from the list of medication included in Bridges to Access halfway through the trial.

Smoking cessation medications use at either 3-months or 6-months was 9 percentage points higher (60.4% vs. 51.3%; P = 0.04) for PAP-noneligible compared with PAP-eligible participants. Among PAP-eligible participants, medication use did not differ significantly between those who did (54.2%) and did not (49.7%) initiate the application process (P = 0.48).

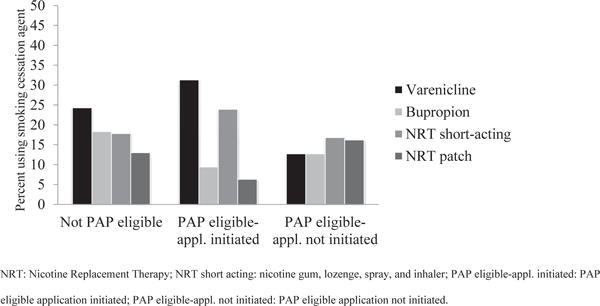

There were differences in the smoking cessation medication selected by participants (Figure 1). For example, varenicline utilization was highest among PAP-eligible participants who initiated the application process (31.3% vs. 12.7%; P = 0.00), and the nicotine patch was the NRT most commonly used by those eligible who did not initiate the PAP application process (16.2% vs 6.3%; P = 0.02). Bupropion SR utilization was higher for PAP-noneligible smokers (18.3% vs 11.5%; P = 0.03). On average, PAP-noneligible participants used their medication for a longer period of time (5.3 wk vs. 3.9 wk; P = 0.03) and had significantly higher abstinence rates at 3-month follow-up (26.2% vs 17.3%; P = 0.01) than participants who were PAP eligible. The difference in abstinence rates was not significant at the 6- and 12-month evaluations (P = 0.07 and P = 0.27, respectively). For PAP-eligible participants who initiated the application process and PAP-eligible participants who did not initiate the application process, no differences in abstinence rates were observed at 3-, 6-, or 12-month follow-ups (P = 0.112, P = 0.599, and P = 0.624, respectively).

Figure 1.

Distribution of smoking cessation medications used.

Discussion

We found that PAP eligibility criteria effectively identified people with lower income and fewer resources who might benefit from free access to medications. At follow-up, however, fewer PAP-eligible patients reported using smoking cessation medications compared with patients with insurance coverage. This suggests that the PAP was less effective, compared with insurance that covered smoking cessation medications, at getting medications into the hands of smokers that wanted to quit. Moreover, among those PAP eligible, medication use was equivalent across those who did and did not initiate the PAP application process, implying that assistance with the application process did not improve access.

The types of medication used, however, did differ across these three groups. The availability of PAP programs, which provided expensive medications such as varenicline at no cost, might have attracted more low-income participants to this medication rather than fast-acting NRTs and bupropion. The small percentage of patients participating in the discount card program was probably associated with the fact that only 4.5% of patients eligible for PAP fell into the 250% to 400% FPL range. Those falling below 250% may have opted for the free medications available through the Pfizer and GSK programs. Interestingly, the nicotine patch was an important option for those PAP eligible who did not initiate the PAP application process. Although PAP-noneligible smokers continued smoking cessation medications for a longer period of time, this did not translate into a significant difference in long-term abstinence. Most smoking cessation medications should be used for 8–12 weeks or longer to optimize outcomes,2 but both PAP-eligible and PAP-noneligible participants reported using smoking cessation medication for a shorter period of time. Data on reasons for discontinuation were not collected as part of this study, although other studies have reported adverse events and relapse to smoking as main factors, and these could have affected the participants in our trial.12,13

Even when smokers were assisted in the process of applying for PAP and reported high motivation to quit smoking at baseline, few completed the paperwork necessary to initiate the process. Only 15.7% of patients eligible for assistance (49/312) completed the process and were connected with smoking cessation medications. Programs such as Pfizer Connection to Care require documentation of economic hardship or other employment circumstances. Although information on the reasons for not completing the process was not collected in this study, others have reported that the process is too time consuming and complex, particularly regarding the required income documentation.14 Other factors influencing PAP utilization include lack of patient awareness and prescriber recommendation,15 not using adequate health literacy in the design of forms and messages,9,16 and the perception of patient’s inability to complete the forms on their own.17

Limitations

Outcome data presented in this study is based on self-report, and recall bias may have affected the results. In addition, smokers participating in this study were rural smokers, so results may not be generalizable to the whole United States population. In addition, our findings may not generalize to patients completing applications on their own or with other forms of support.

The process designed as part of this trial could have added extra steps that might have influenced our findings. Clinics assisted their patients potentially on site and via telephone, but the research staff helped participants by mailing or faxing application materials to the patient, providing telephone support, and communicating with participants’ health care providers as needed. Finally, the GSK program for bupropion SR was discontinued during the trial, which limited our ability to evaluate the usefulness of that program for patients.

Conclusion

Although this program was successful in connecting 49 smokers with smoking cessation medications, there were an additional 258 smokers who were PAP eligible but did not acquire medications through these programs. Smokers with prescription insurance and higher incomes more frequently accessed smoking cessation medications. Further work is needed to identify alternatives for improving access to appropriate pharmacotherapy for low-income smokers wanting to quit. Although pharmaceutical companies are generous when providing free access to chronic medications, the ability to access medications through PAP for any given individual is a difficult challenge to overcome. Ultimately, PAP may not be able to correct important gaps in care for rural and low-income populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Award no. R01HL087643 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1. Distribution of study participants by participation in pharmacy patient assistance programs (PAPs)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Angie Leon-Salas, Instructor, School of Pharmacy, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica.

Jamie J. Hunt, Teaching Assistant Professor, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO.

Kimber P. Richter, Professor, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Niaman Nazir, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Edward F. Ellerbeck, Professor and Chair, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Theresa I. Shireman, Professor, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, Brown University, Providence, RI.

References

- 1.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;10(260) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence Clinical practice guideline 2008 update. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: 2011. Available at: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/incpovhlth/2010/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Jeffries SK, Mussulman LM, Casey GN. Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. J Rural Health. 2008;24(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson PE. Patient assistance programs and patient advocacy foundations: alternatives for obtaining prescription medications when insurance fails. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(21 Suppl 7):S13–S17. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisholm MA, DiPiro JT. Pharmaceutical manufacturer assistance programs. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):780–784. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felder TM, Palmer NR, Lal LS, Mullen PD. What is the evidence for pharmaceutical patient assistance programs? A systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1) doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhry NK, Lee JL, Agnew-Blais J, Corcoran C, Shrank WH. Drug company-sponsored patient assistance programs: a viable safety net? Health Aff Proj Hope. 2009;28(3):827–834. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mussulman L, Ellerbeck EF, Cupertino AP, Preacher KJ, Spaulding R, Catley D, et al. Design and participant characteristics of a randomized-controlled trial of telemedicine for smoking cessation among rural smokers. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter KP, Shireman TI, Ellerbeck EF, Cupertino AP, Catley D, Cox LS, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop-smoking medications: data from the ITC four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:94–103. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etter JF, Schneider NG. An internet survey of use, opinions and preferences for SCM: nicotine, varenicline, and bupropion. Nicotin Tob Res. 2013;15:59–68. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duke KS, Raube K, Lipton HL. Patient-assistance programs: assessment of and use by safety-net clinics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(7):726–731. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.7.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omojasola A, Hernandez M, Sansgiry S, Paxton R, Jones L. Predictors of $4 generic prescription drug discount programs use in the low-income population. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(1):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federman AD, Safran DG, Keyhani S, Cole H, Halm EA, Siu AL. Awareness of pharmaceutical cost-assistance programs among inner-city seniors. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(2):117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisu M, Richman J, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Kiefe CI. Pharmaceuticals companies’ medication assistance programs: potentially useful but too burdensome to use? South Med J. 2009;102(2):139–144. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31818bbe5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]