Abstract

Despite adequate dietary management, patients with Classic Galactosemia continue to have increased risks of cognitive deficits, speech dyspraxia, primary ovarian insufficiency, and abnormal motor development. A recent evaluation of a new galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT)-deficient mouse model revealed reduced fertility and growth restriction. These phenotypes resemble those seen in human patients. In this study, we further assess the fidelity of this new mouse model by examining the animals for the manifestation of a common neurological sequela in human patients: cerebellar ataxia.

The balance, grip strength, and motor coordination of GALT-deficient and wild-type mice were tested using a modified rotarod. The results were compared to composite phenotype scoring tests, typically used to evaluate neurological and motor impairment. The data demonstrated abnormalities with varying severity in the GALT-deficient mice. Mice of different ages were used to reveal the progressive nature of motor impairment. The varying severity and age-dependent impairments seen in the animal model agree with reports on human patients. Finally, measurements of the cerebellar granular and molecular layers suggested that mutant mice experience cerebellar hypoplasia, which could have resulted from the down-regulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Introduction

Classic Galactosemia (OMIM 230400) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder resulting from homozygous deleterious mutations in the galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) gene. Although dietary management can prevent the acute toxicities associated with the newborn period, some patients continue to demonstrate increased risks of cognitive deficits, speech problems, primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), and abnormal motor functions, which include tremor, dystonia and ataxia (Waggoner 1993; Waisbren et al 2012; Rubio-Agusti et al 2013).

To date, many questions about the ataxia phenotype, among others, seen in some patients with Classic Galactosemia remain unanswered. For instance, it is unclear why only approximately 15–18% of the galactosemic patients have been reported to manifest this phenotype while over 90% of the female patients will have POI (Waggoner 1993; Waisbren et al 2012). There is equally uncertainty about the time of onset of the neurological abnormality and the molecular mechanisms involved. In model systems studies, Jumbo-Lucioni et al reported that co-removal of the dGALK (galactokinase) gene or sugarless overexpression corrected the aberrant glycosylation of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) extracellular synaptomatrix carbohydrates and the impaired coordinated movement in a Drosophila model of Classic Galactosemia (Jumbo-Lucioni et al 2014), further solidifying the pathogenic roles of galactose-1 phosphate and aberrant glycosylation GALT deficiency in this invertebrate. Studies in human patients led some investigators to propose that aberrant signaling pathways, notably phosphatidylinositol signaling (Berry 2011; Coss et al 2014), and defective glycosylation secondary to the accumulation of toxic galactose metabolites and deficiency of UDP-galactose are responsible for the neurological damages observed in these patients (Maratha et al 2016; Maratha et al 2016). Yet, it is important to realize that these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and that they may act at different times during the central nervous system (CNS) development.

A recent study of a new GALT-deficient mouse model revealed growth restriction and reduced fertility (Tang et al 2014), phenotypes commonly seen in human patients with Classic Galactosemia. In this study, we further assessed the fidelity of this new mouse model by evaluating the mutant mice for the manifestation of cerebellar ataxia with experiments using a modified rotarod, placing more emphasis on evaluating the ataxia-related motor impairment in mice. The results, which were validated using composite score testing (Guyenet et al 2010), revealed age-dependent motor impairment in the GALT-deficient mice. Histological studies showed significantly decreased thickness of both granular and molecular layers, which could partly result from down-regulation of the canonical phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/ protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway in GALT-deficient cells reported earlier (Balakrishnan et al 2016).

Methods and Materials

Animals and Diet

GALT-deficient mice used in this study were constructed as previously described (Tang et al 2014). All mice were confirmed genotyped (molecular and biochemical) using protocol published (Tang et al 2014). Homozygous GalT−/− were determined to have zero GALT activity in their red blood cells and livers. All mice were fed with normal chow since weaning. No galactose challenge was attempted throughout this work.

Modified Rotarod

To better assess the ataxia-related motor impairment of mice with GALT deficiency, we modified the traditional single-rod rotarod to encourage the animal to walk along the rod alternating between limbs, instead of passively using its body for support. This was accomplished using 1 cm diameter array of circular rods (Fig. 1). Discs were also placed on the sides of the animal to minimize external distractions. The discs also assisted in maximizing the animals’ movement around the rod instead of along the length. The incorporation of these changes placed greater emphasis on testing ataxic-related impairment in our mouse model.

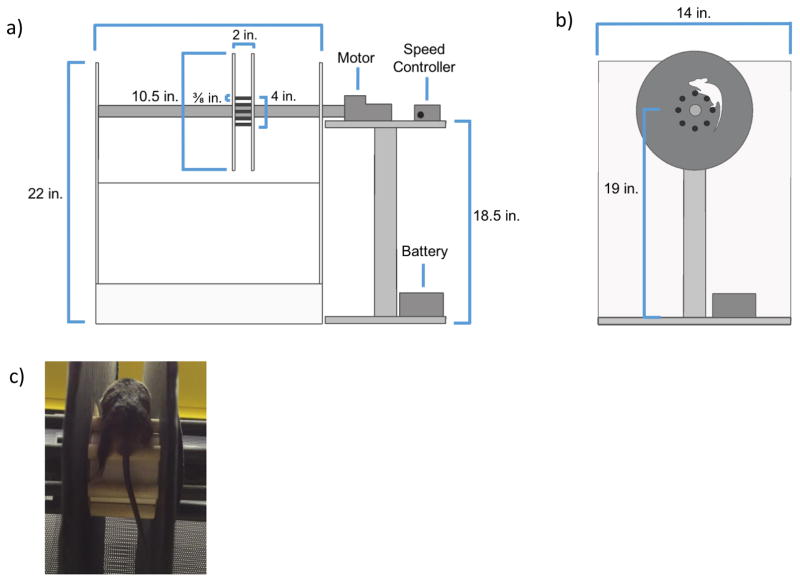

Figure 1. Modified Rotarod.

a: Front view of Production Model. The rotating rod placed at an appropriate height above a landing pad. The cylindrical array of rungs are in between the two disks, 27 cm in diameter. The entire length of the rod is 56 cm. The entire model is enclosed is plexi-glass, while the motor drives the rotation of the rod. The speed controller adjusts the speed between 6 RPM and 12 RPM.

b: Side view of Production Model. The animated mouse demonstrates how the animal must move to stay stable on the device as the rod rotates clockwise.

c: Working Model. Mouse demonstrating alternating leg movement on modified rotarod with rungs.

The modified rotarod rotated in conjunction with a PPI motor (100 RPM, 24 V, 3 A). The rod’s speed was adjusted with a pulse width modulator (6–90 V, 10 A Rated) and was powered with a Power Sonic rechargeable battery (12 V, 7A). As with common rotarods (Kamens and Crabbe 2007), the time the animal successfully walked on the rod was used as a measure of motor coordination. The rod’s speed gradually increased to 6 RPM over two minutes for training purposes. After resting for two-minute, the mouse was tested at 6 RPM for a maximum of two minutes (lower time if animal failed test). The trial was repeated at 12 RPM. Each mouse was tested three times at each speed after a five-minute resting period. The modified apparatus built for this study is displayed in Fig. 1.

Composite Phenotype Scoring Test

To validate the results obtained using the modified rotarod, the mice’s gait, as well as kyphosis severity, hind limb clasping phenotype, and the ability to walk across the ledge of the cage were evaluated. These tests offer sensitive quantification of disease severity in mouse models of cerebellar ataxia (Guyenet et al 2010). Following the published protocol of Guyenet and coworkers, a researcher without any prior knowledge of the mice’s genotype conducted the tests in order to prevent bias. Each mouse was accessed three times for each test. All tests were quantified on a scale from zero to three, where three was considered the most severe manifestation.

Histological Studies

The animal cranium was extracted and placed in ice cold PBS followed by 10% formalin to fix for at least 48 hours. Several washes were done with 70% ethanol over a period of 48 hours to rehydrate the tissue. The whole brain with attached cerebellum was isolated from the skull and cut in half along the mid-sagittal plane prior to tissue processing, slide preparation, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining performed by the Research Histology Core Facility of the ARUP Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT, USA). H&E-stained sections were sent to board-certified pathologists at the University of Florida for the measurement of the granular and molecular layers in a single-blinded manner. Slides were then used for Purkinje cell count of each section.

(a) Granular and Molecular Layer Measurements

The thicknesses of molecular and granular layers of each cerebellum were measured using a micrometer. Twenty measurements throughout the cerebellum were performed on each slide (GalT+/+ n=5, GalT+/− n=5, GalT−/− n=5).

(b) Purkinje Cell Count

Purkinje cells of five cerebellar papillae were counted and length of papillae was measured from the most superficial point of the papillae to the intersection between the end of fissures on each side of the papillae. Twenty measurements were performed on each slide (GalT+/+ n=5, GalT+/− n=5, GalT−/− n=5). All slides were reviewed by two board-certified pathologists. Both pathologists simultaneously reviewed each slide using a dual headed microscope, each using an independent ocular micrometer with a 10X objective, following calibration when taking measurements and counting.

Immunoblot analyses

Protein lysates from dissected cerebella were prepared by mechanical disruption of the tissue in hypotonic buffer [25 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 25 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.2)] with protease and phosphatase inhibitors at 4°C. The cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 15 min at 4°C. Pierce BCA protein estimation kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine total protein concentration. 40 μg of the total protein was resolved by 12% SDS- PAGE before being transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The procedures for immunoblot analyses of the key protein members of the PI3K/Akt pathway in the protein lysates, as well as the vendors for the antibodies used, are reported in an earlier study (Balakrishnan et al 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was performed to determine statistical significance of experimental results among groups.

Results

Rotarod Studies

We performed rotarod studies using the following six groups of mice:

| GalT−/− | GalT+/− | GalT+/+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 5 months old | 12 mice | 10 mice | 8 mice |

| 6 to 10 months old | 12 mice | 11 mice | 10 mice |

Human patients who are heterozygous for deleterious GALT mutations are clinically normal, and we did not observe any statistically significant differences between the GalT+/+ and the GalT+/− mice. Therefore, we grouped these mice together as one group for subsequent comparison with the GalT−/− mice.

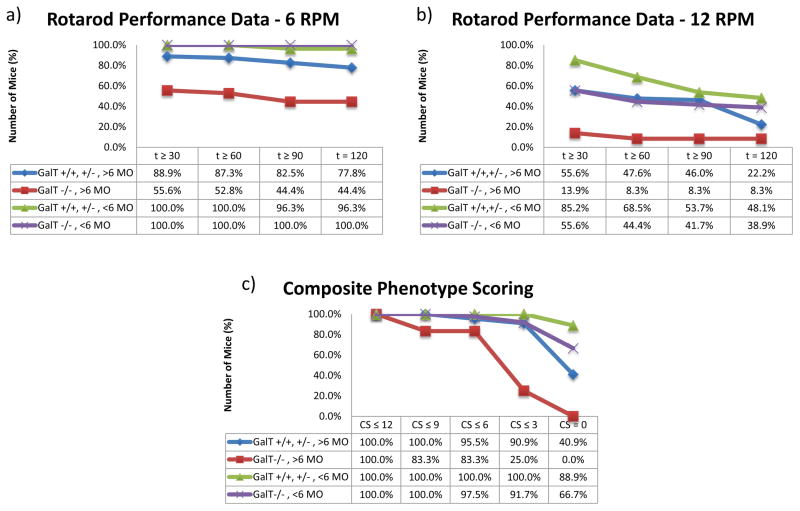

As shown in Fig. 2a & b, 87.3% of (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice aged between 6 to 10 months were able to attain the one-minute mark at 6 RPM. Comparatively, 52.8% of GalT−/− mice met the one-minute mark. 77.8% of the (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice and 44.4% of the GalT−/− sufficiently completed the entire two-minute test at 6 RPM (p = 3.14 x 10−4). At 12 RPM, 47.6% of (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice and 8.3% GalT−/− met the one-minute mark. 22.2% of (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice and an unchanged 8.3% of GalT−/− completed the test to the two-minute mark at 12 RPM (p = 6.03 x 10−3).

Figure 2. Modified Rotarod Performance Test and Composite Phenotype Scoring.

a: Rotarod Results for 6 RPM. Percentages of mice that completed the time points along the x-axis (seconds) are indicated.

b: Rotarod Data for 12 RPM. Percentages of mice that completed the time points along the x-axis (seconds) are indicated.

c: Composite Phenotype Scoring Data. Percentages of mice rated on a scale of 0–12, with 12 representing the highest degree of cerebellar ataxia.

It appears that mice aged younger than 6 months outperformed mice older than 6 months in both (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) and GalT−/− groups (Fig. 2a & b). However, statistical analyses reveal significant difference only in the GalT−/− mice. GalT−/− mice younger than 6 months significantly outperformed GalT−/− mice older than 6 months at 6 RPM and 12 RPM (p = 2.5 x 10−8 and p = 1.34 x 10−4, respectively).

Composite Phenotype Scoring Test

Using Composite Phenotype Scoring, which evaluates coordination (ledge test), neurological/motor impairment (hind limb clasping), gait, and degree of kyphosis, we showed 25% of homozygous GalT−/− mice older than six months had composite scores less than or equal to 3, compared to 90.9% in the (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice (p = 2.0 x 10−4) (Fig. 2c).

Similar to the rotarod results, GalT−/− mice younger than 6 months had a significantly lower composite score than mice older than 6 months, suggesting the progressive nature of the impairment (p = 8.0 x 10−5). There was no significant difference in the composite scores between older and younger mice in the (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) group (p = 8.1 x 10−2), as well as the scores between GalT−/− and (GalT+/+ + GalT+/−) mice younger than 6 months old (p = 6.5 x 10−1).

Histological Studies of Isolated Cerebella

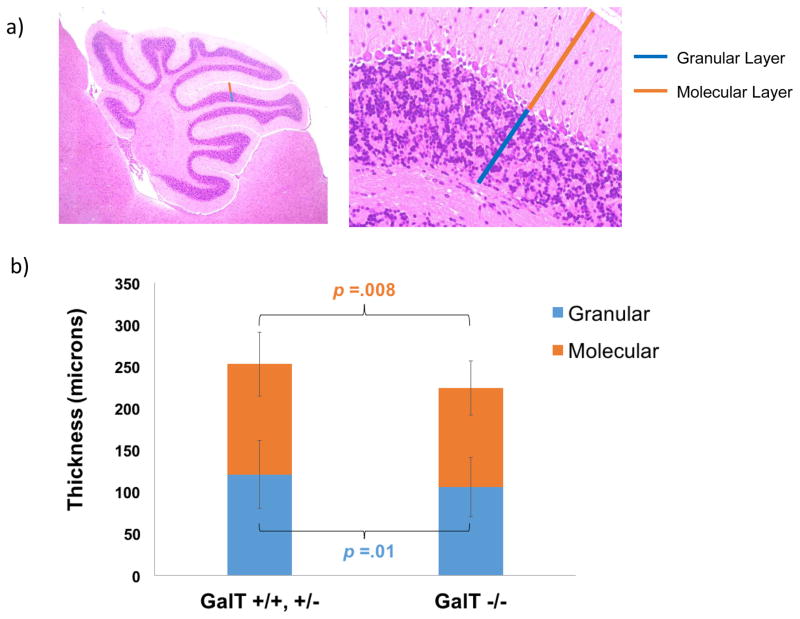

As a first step to delineate the underlying mechanisms that may account for the ataxia-related motor impairment displayed in the GalT−/− mice, histological studies were performed on isolated cerebella from five GalT +/+, five GalT +/−, and five GalT −/− mice. Since we observed more severe motor impairment in the older mice, we focused our histological studies on mice aged between six to ten months of age. We did not observe any remarkable changes in the morphology and the number of the Purkinje cells in the H&E stained sections of the mutant mouse cerebella, but the combined thickness of the granular and molecular layers in the GalT−/− mice was 13.05% (p = 0.002) smaller than in the (GalT+/+ and GalT+/−) mice (Fig. 3a & b).

Figure 3. Analysis of isolated cerebella from normal and mutant mice.

a: Location of molecular and granular layers of cerebellum.

b: Thickness measurements of molecular and granular layers in wild-type, heterozygous and homozygous mutant mouse cerebella with respective p values.

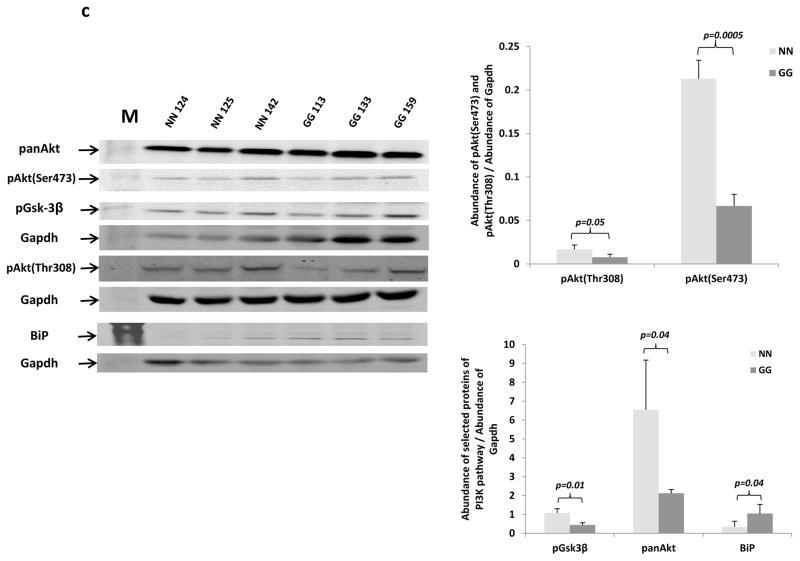

c: Protein expression levels of pAkt (Thr308), pAkt (Ser473), panAkt, pGsk3β and BiP from the cerebella of normal (NN) and mutant mice (GG) (n=3 for each group) were compared by Western blot analysis. (M=Molecular weight markers).

Quantified results for the abundance of the selected proteins are presented in the graphs shown on the right.

Immunoblot Analyses of Isolated Cerebella

To further understand the molecular mechanisms that might account for the reduced thickness of the granular and molecular layers in the cerebella of the GalT−/− mice, we assessed the expression levels of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the isolated tissues. The PI3K/Akt growth signaling pathway is essential for the normal growth and survival of many tissues, including neuronal tissues (Zhang et al 2010; Xu et al 2011; Zhang et al 2013). Fig. 3c shows significant reduced steady-state protein abundance of pAkt(Ser473), pAkt(Thr308), pan-Akt, pGSK-3β, but increased abundance of BiP, a stress response protein (Little et al 1996).

Discussion

Despite adequate dietary management, ataxia remains a known complication with variable severity in many patients with Classic Galactosemia (Waggoner 1993; Waisbren et al 2012). Therefore, there is an urgent need to elucidate the mechanisms of impairment affecting these patients in order to improve their quality-of-life. Various groups have made notable advances in this aspect through studies of patients and model organisms (Haberland et al 1971; Bohles et al 1986; Nelson et al 1992; Berry et al 2001; Kushner et al 2010; Berry 2011; Potter et al 2013; Rubio-Agusti et al 2013; Coss et al 2014; Jumbo-Lucioni et al 2014; Timmers et al 2015; Jumbo-Lucioni et al 2016; Maratha et al 2016; Timmers et al 2016). In this study, we aimed to establish if our GALT-deficient mouse model is a suitable animal model for the pathophysiology studies of the ataxia phenotype in human patients. To begin with, we had to demonstrate that the mutant mice exhibit ataxia-related motor impairments. There are other movement disorders (e.g., tremor and dystonia) experienced by some of the patients with the disease (Waggoner 1993; Waisbren et al 2011; Rubio-Agusti et al 2013), but we would like to focus on ataxia in this pilot study. The positive outcome of the study will justify future examination of other movement disorders in this mouse model.

As shown in Fig. 2, the GalT−/− mice manifest ataxia-related motor impairments with varying degrees of severity in rotarod studies, which was validated by composite phenotype scoring tests. In addition, we demonstrated the progressive nature of the impairments in older mice. We hypothesize that as the mutant mice grow older, the chronic stress-related cellular damages induced by toxic galactose metabolites finally reach the threshold beyond which the functions of the targeted organs begin to fail. In a broad sense, our hypothesis shares some features from the thesis of “apoptosis lente” proposed by Vincent and colleagues (Vincent et al 2004), where they proposed a more stately neuronal degenerative process involving the apoptotic cascade is involved in the pathophysiology of chronically damaged neurons in diabetes. Our results nonetheless are in agreement with two reports of patient observations (Bohles et al 1986; Rubio-Agusti et al 2013). However, because only a small number of patients were examined in the two reports, more research will be needed to confirm the progressive nature of the phenotype in human patients. Also, in human patients, variability of phenotypes has been attributed to epigenetic factors, but none have been convincingly identified. Based upon our evaluation shown in Fig. 2, we feel that we can launch further studies into the pathophysiology of the phenotype in our mouse model.

The decreased thicknesses of the combined molecular and granular layer in the cerebella of the mutant mice suggest the GalT−/− mice experience cerebellar hypoplasia (Fig. 3a & b). Indeed, cerebellar atrophy has also been reported in patients with Classic Galactosemia (Nelson et al 1992). Since we have previously demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is down-regulated in the primary skin fibroblasts derived from the mutant mice (Balakrishnan et al 2016), we examined the protein expression levels of this pathway in the isolated cerebella. As shown in Fig. 3c, we showed that the down-regulated PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the cerebella may explain, in part if not wholly, the hypoplasia observed (Balakrishnan et al 2016). Future studies are required to further validate if the hypoplasia detected is responsible for motor impairment observed in the GALT deficient mice. Nevertheless, perturbation of this growth signaling pathway was also found in patient-derived dermal fibroblasts of patients exposed to toxic levels of galactose (Coss et al 2014).

Earlier, we reported smaller, more acidophilic Purkinje cells in a punctuated layer were found in GALT-deficient pups challenged with galactose (Tang et al 2014). Other abnormal changes were also documented in human patients with Classic Galactosemia (Nelson et al 1992; Potter et al 2013). Therefore, we were initially puzzled when we were unable to observe decreased Purkinje cell counts or remarkable change in their morphology in the cerebella of the mutant mice, which would have otherwise provided more direct evidence for Purkinje cell death/damages in these animals. Yet, it is noteworthy to mention that Timmers et al also failed to notice any changes in white matter microstructure, as well as grey matter density, in the cerebella of a small number of human galactosemic patients, despite the fact that they found profound changes elsewhere in the same brains (Timmers et al 2015; Timmers et al 2016). Moreover, we did not challenge our mice with galactose in this study as we did for the pups we reported earlier (Tang et al 2014). Furthermore, although we did not observe any gross abnormalities in the Purkinje cell layers, this does not automatically preclude the absence of adverse changes. It could simply be the result of the limited resolutions in H&E stained sections and/or that the changes are too subtle to be seen at the histological levels. Future experiments, which include electrophysiological studies of these mice, determination of cerebellar weight, and more sophisticated immunostaining of the Purkinje cells, could provide additional clues to the underlying mechanisms of the observed motor impairments in the mutant animals.

Acknowledgments

Details of funding

Grant support to KL include 1R01HD074844 (NIH/NICHD), a Research Grant from the Galactosemia Foundation (USA), a generous gift from the Dershem Family (Race 4 Jase), the K2R2R grant award from the Primary Children’s Hospital Foundation (Intermountain Healthcare). The authors confirm independence from the sponsors and the sponsors have not influenced the content of the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Wyman Chen declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Rose Caston declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Bijina Balakrishnan declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Anwer Siddiqi declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Kamalpreet Parmar declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Manshu Tang declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Merry Feng declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Kent Lai declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Informed Consent

This research does not contain any studies with human subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Animal Rights

All institutional and national guideline for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Details of ethics approval

This research does not involve human subjects and therefore, IRB approval is not required.

Details of the contributions of individual authors:

Wyman Chen - Planning and Performance of the Experiments, and Composition of the Manuscript.

Rose Caston - Planning and Performance of the Experiments, and Composition of the Manuscript.

Bijina Balakrishnan - Planning and Performance of the Experiments.

Anwer Siddiqi – Planning & Performance of the Experiments.

Kamalpreet Parmar – Planning & Performance of the Experiments.

Manshu Tang – Planning & Performance of the Experiments.

Merry Feng – Planning & Performance of the Experiments.

Kent Lai - Planning of the Experiments, Interpretation of the Results, and Composition of the Manuscript.

Name of one author who serves as guarantor

Kent Lai

References

- Balakrishnan B, Chen W, Tang M, et al. Galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalT) gene: A novel positive regulator of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in mouse fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;470:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry GT. Is prenatal myoinositol deficiency a mechanism of CNS injury in galactosemia? J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:345–355. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry GT, Hunter JV, Wang Z, et al. In vivo evidence of brain galactitol accumulation in an infant with galactosemia and encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2001;138:260–262. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.110423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohles H, Wenzel D, Shin YS. Progressive cerebellar and extrapyramidal motor disturbances in galactosaemic twins. Eur J Pediatr. 1986;145:413–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00439251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coss KP, Treacy EP, Cotter EJ, et al. Systemic gene dysregulation in classical Galactosaemia: Is there a central mechanism? Mol Genet Metab. 2014;113:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet SJ, Furrer SA, Damian VM, Baughan TD, La Spada AR, Garden GA. A simple composite phenotype scoring system for evaluating mouse models of cerebellar ataxia. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2010 doi: 10.3791/1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland C, Perou M, Brunngraber EG, Hof H. The neuropathology of galactosemia. A histopathological and biochemical study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1971;30:431–447. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumbo-Lucioni P, Parkinson W, Broadie K. Altered synaptic architecture and glycosylated synaptomatrix composition in a Drosophila classic galactosemia disease model. Dis Model Mech. 2014 doi: 10.1242/dmm.017137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumbo-Lucioni PP, Parkinson WM, Kopke DL, Broadie K. Coordinated Movement, Neuromuscular Synaptogenesis and Trans-Synaptic Signaling Defects in Drosophila Galactosemia Models. Hum Mol Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Crabbe JC. The parallel rod floor test: a measure of ataxia in mice. Nature protocols. 2007;2:277–281. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner RF, Ryan EL, Sefton JM, et al. A Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:618–627. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little E, Tocco G, Baudry M, Lee AS, Schreiber SS. Induction of glucose-regulated protein (glucose-regulated protein 78/BiP and glucose-regulated protein 94) and heat shock protein 70 transcripts in the immature rat brain following status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 1996;75:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratha A, Colhoun HO, Knerr I, Coss KP, Doran P, Treacy EP. Classical Galactosaemia and CDG, the N-Glycosylation Interface. A Review. JIMD reports. 2016 doi: 10.1007/8904_2016_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratha A, Stockmann H, Coss KP, et al. Classical galactosaemia: novel insights in IgG N-glycosylation and N-glycan biosynthesis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:976–984. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MD, Jr, Wolff JA, Cross CA, Donnell GN, Kaufman FR. Galactosemia: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;184:255–261. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1319076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter NL, Nievergelt Y, Shriberg LD. Motor and speech disorders in classic galactosemia. JIMD reports. 2013;11:31–41. doi: 10.1007/8904_2013_219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Agusti I, Carecchio M, Bhatia KP, et al. Movement disorders in adult patients with classical galactosemia. Mov Disord. 2013;28:804–810. doi: 10.1002/mds.25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Siddiqi A, Witt B, et al. Subfertility and growth restriction in a new galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) - deficient mouse model. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:1172–1179. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers I, van der Korput LD, Jansma BM, Rubio-Gozalbo ME. Grey matter density decreases as well as increases in patients with classic galactosemia: A voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Res. 2016;1648:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers I, Zhang H, Bastiani M, Jansma BM, Roebroeck A, Rubio-Gozalbo ME. White matter microstructure pathology in classic galactosemia revealed by neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9780-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent AM, Russell JW, Low P, Feldman EL. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:612–628. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner D, Buist NRM. Long-term complications in treated galactosemia - 175 U.S. cases. International Pediatrics. 1993;8:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Waisbren S, Potter N, Gordon C, et al. The Adult Galactosemic Phenotype. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Diseases. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9372-y. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisbren SE, Potter NL, Gordon CM, et al. The adult galactosemic phenotype. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9372-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang Q, Yu S, Yang Y, Ding F. The protective effects of chitooligosaccharides against glucose deprivation-induced cell apoptosis in cultured cortical neurons through activation of PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK1/2 pathways. Brain Res. 2011;1375:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Deng Z, Liao J, et al. Leptin attenuates cerebral ischemia injury through the promotion of energy metabolism via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2013;33:567–574. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qu Y, Tang J, et al. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is required for neuroprotection of thalidomide on hypoxic-ischemic cortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 2010;1357:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]