Abstract

The paper utilizes data collected at three time points in a longitudinal study of perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) and a comparison group of perinatally exposed but HIV-uninfected (PHEU) youths in the United States (N = 325). Using growth curve modeling, the paper examines changes in substance use symptoms among PHIV+ and PHEU youths as they transition through adolescence, and assesses the individual and contextual factors associated with the rate of change in substance use symptoms. Findings indicate that substance use symptoms increased over time among PHIV+ youths, but not among PHEU youths. The rate of change in these symptoms was positively associated with an increasing number of negative life events. Study findings underscore the need for early, targeted interventions for PHIV+ youths, and interventions to reduce adversities and their deleterious effects in vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Adolescence, Stress, People living with HIV, Drug use

Introduction

Addressing the HIV epidemic entails reducing community viral load by increasing early identification of HIV infection, rapid linkage to HIV care, treatment initiation with optimal medication adherence, and sustained retention in care of HIV+ individuals. This approach, also known as Treatment as Prevention (TasP), is a promising HIV prevention strategy [1–3]. Similar to behavioral risk reduction strategies (e.g. condom use), maximizing the benefits of TasP entails reducing any barriers to its implementation, especially among high-risk populations. Substance use is a formidable barrier to the implementation of TasP and other behavioral risk reduction strategies among youths [4]. Previous studies have reported that adolescents with perinatally-acquired HIV (PHIV+), similar to their peers, are experimenting with alcohol and illicit drugs [5, 9–12]. The emergence of substance use among PHIV+ youths poses a serious public health concern; substance use can function as a barrier to antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence [11, 13, 14] and condom use, leading to viral suppression failure and ART drug resistance [15], as well as increased risk for secondary transmission of HIV due to condomless sex [7, 16–18]. As such, substance use undermines the potential public health impact of both biomedical and behavioral-risk reduction strategies among PHIV+ youth.

Only a few studies have examined the prevalence and correlates of substance use among PHIV+ youths with studies reporting rates of any or lifetime substance use ranging from 13–60 % [7, 11, 19, 20]. Our current understanding of problematic substance use among PHI-V+ youths is limited because substance use typically begins to take off in middle-older adolescence and PHI-V+ youths are only now reaching this age in large enough numbers to be studied. The majority of prior studies conducted among PHIV+ youths have included mostly early-middle aged adolescents, and almost none of these studies looked at problematic substance use because the numbers of substance abusing PHIV+ youths would be too small at the younger age range. However, Mellins and colleagues found substance use disorders increased from 1.8 %, when PHIV+ youth were on average 12 years old, to 4.2 %, when participants were 14 years [21]. While still relatively low during early-middle adolescence, these findings suggested an increase not only in substance use, which is developmentally normative during adolescence, but also an increase in problematic substance use (as evidenced by the increase in substance use disorders) [21]. Thus further examination of substance use in PHIV+ youths as they age through adolescence is warranted in order to advance our understanding of the development of problematic substance use and thus ability to treat this highly vulnerable group [5].

Little is known about how substance use symptoms develop among PHIV+ youths, nor about the individual and contextual factors that influence substance use in this population. In particular, the role of HIV infection in the development of problematic substance use is unclear. Findings from prior studies that have examined differences in substance use between PHIV+ and youths perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) youths suggest that youth HIV status was not associated with greater likelihood of substance use. Rather, other key individual (e.g. youths’ age, mental health problems), social (e.g. perceived peer norms) and contextual (e.g. caregiver psychiatric disorder, substance use in the household) factors appear to confer greater risk [7, 11, 19, 20]. However, these studies were largely cross-sectional and focused on mostly younger adolescence, when rates of problematic substance use and disorder are typically low [22, 23]. In contrast, one longitudinal examination of the development of alcohol and marijuana use across adolescence in PHI-V+ and PHEU youths found differences in substance use by HIV status. Although both groups experienced a significant increase in alcohol use (from 12.8 to 56.9 % of PHIV+ youths and from 15.5 to 48.9 % of PHEU youths) and marijuana use (from 4.1 to 30.7 % of PHIV+ youths and from 7.8 to 29.6 % of PHEU youths) over time, PHIZ+ youths were less likely to use marijuana than PHEU youths [5]. However, this study did not examine key individual, social and contextual factors that may account for differences in substance use between PHI-V+ and PHEU youths.

In the United States (U.S.), the pediatric HIV epidemic is concentrated among minority youth residing in impoverished, inner city neighborhoods, which expose these youth to well-known risk factors for substance use and abuse [24–26]. Substance use among urban minority youth has been associated with various factors, including mal-adaptive coping strategies (e.g. emotional and avoidance coping behaviors) and/or inadequate psychosocial resources (e.g. positive future orientation) to mitigate the deleterious effects of stressors [27–30], and environmental stressors such as trauma, stressful life events, neighborhood disorganization, and exposure to violence and victimization [31–36]. In addition to the challenges associated with adolescence (e.g. peer relations, school transitions, academic pressures), PHIV+ youths also experience familial and environmental stressors (e.g. bereavement, household poverty, poor caregiver physical and mental health) that impact their wellbeing [31–33]. Therefore, in a context of multiple chronic stressors and limited family and community resources, PHIV+ youths are at increased risk for substance use compared to their peers. Moreover, PHI-V+ youths also experience additional stressors, such as chronic pain, delayed developmental milestones, and managing a chronic, life-threatening, and highly stigmatized illness, [31, 33, 34, 37, 38] which potentially place them at even greater risk for substance use as they age. Understanding the role HIV and other key individual and contextual factors may play in the development of substance use is important to the development of effective substance use preventive interventions.

One factor that is a potential barrier to fully understanding substance use and abuse among PHIV+ youths is that the criteria for diagnosing substance use disorders, which are stipulated in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), were developed primarily for adults. As such, they may not account for developmental differences between youth and adults with respect to substance use (e.g. withdrawal symptoms and physiological dependence, which are less prevalent in youth). The use of DSM criteria to diagnose substance use disorders can result in a negative diagnosis even though a youth may be abusing substances or demonstrating multiple substance-related problems [39, 40]. For example, Aarons and colleagues found that 18 % of youth in treatment for substance abuse did not meet DSM criteria for substance use disorders even though all exhibited substance use-related problems that required treatment [40]. As such, examining the development of symptoms of substance use disorders over time may allow us to understand problematic substance use in high risk youth who would have otherwise been undetected through examination of disorder.

In summary, there are few published studies of substance use among PHIV+ youths, and those that exist are cross sectional, focus on early to middle adolescence when substance use is just beginning, and have limited data on psychosocial factors that influence substance use that would inform preventive interventions. To date, there are few longitudinal analyses, particularly from studies that follow youth into older adolescence, when substance use becomes much more prevalent in other populations and when problematic use frequently begins. To address this issue, using data from a relatively large study of psychosocial determinants of behavior in a sample composed of both PHIV+ and PHEU youths with similar age and demographic backgrounds, this paper examines prospective changes in substance use symptoms in PHI-V+ youths, in comparison to PHEU youths. We assess the role of HIV as well as individual and contextual factors associated with these changes. These analyses are guided by elements of the Social Action Theory (SAT) [41], which asserts that health outcomes (in this case, substance use symptoms) are influenced by contextual factors in which the behavior occurs, including youths’ internal context (e.g. youths’ age, gender, youths’ HIV status), external context or environment (e.g. neighborhood stressors, stressful life events, caregiver mental health and caregiver HIV status), and self-regulation (e.g. youths’ future aspirations). PHEU youths were chosen as the comparative group for PHIV+ youths because, with the exception of the child’s HIV status, sociodemographic and family characteristics, including perinatal exposure to HIV, are very similar, thus providing an initial opportunity to explore the unique contribution of HIV infection to substance use, in addition to contextual factors. In these analyses, we hypothesize that PHIV+ youths will have a greater increase in the substance use symptoms compared to PHEU youths, given the additional burden of illness-related stressors.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This paper utilizes data from the Child and Adolescent Self-Awareness and Health Study (CASAH), a multi-center longitudinal study of PHIV+ and PHEU youths receiving care at four primary and tertiary centers in NYC. A detailed description of the study design is provided elsewhere [21]. Briefly, PHIV+ and PHEU youths and their caregivers were recruited between 2003 and 2008 when the youths were aged 9–16 years. Data were collected using caregiver and youth individual interviews, conducted separately but simultaneously whenever possible at the youth’s/care-giver’s homes, their medical clinics, or our research office, by trained bachelor-level interviewers. Based on participant preference, all youths were interviewed in English, and 67 caregiver interviews were conducted in Spanish. Consistent with standard procedures for translation and back-translation [42], all study instruments were translated into Spanish and certified by an Institutional review board (IRB)-approved expert translator. IRB approval was obtained from all study sites. All caregivers provided written informed consent for themselves and their youths who were <18 years of age; youths provided written assent (if <18 years) or consent if ≥18 years. Monetary reimbursement for each completed session ($25) and public transport was provided.

Of the 443 eligible participants, 11 % refused contact with the research team, and 6 % could not be contacted by the site clinic coordinators. A total of 367 (83 %) caregiver–youths dyads were approached, of whom N = 340 were enrolled at baseline (77 % of eligible families; 206 PHI-V+ and 134 PHEU youth). The baseline and Follow-up 1 (FU1) interviews were completed approximately 18 months apart (Myears = 1.65, SD = 0.45). Although not originally planned, funding was obtained for additional follow-up interviews (Phase 2). Phase 2 involved re-recruiting families from phase 1 for three additional follow-up interviews, each 1 year apart. Families were eligible for phase 2 interviews if the youths were at least 13 years old and it had been at least 1 year since their FU1 interview. All youth and their care-givers who were re-enrolled in the study at phase 2 (FU2) provided written consent and assent, as necessary.

These analyses utilized three waves of data collection: phase 1 (baseline and follow-up: FU1) and phase 2 (FU2). Overall, the retention rates were high: 82.4 % (166 PHI-V+ and 114 PHEU youths) between baseline and FU1, and 79 % (166 PHIV+ and 104 PHEU) of youths who were initially enrolled in phase 1 were successfully recruited for phase 2. The median time interval between FU1 and FU2 was 3 years (Myears = 2.89, SD = 1.29). At FU2, youths’ ages ranged from 13 to 24 years (Mage = 16.73, SD = 2.74).

A total of 325 youths (196 PHIV+ and 129 PHEU) with data on all key covariate variables at baseline were included in these analyses; 15 youths were excluded from these analyses due to missing data. There were no differences by youths’ HIV status, gender, race/ethnicity, age, and mental health outcomes between the youths whose data are analyzed and those excluded from the analysis. Among youths included in the study, we observed minimal but statistically significant differences in follow-up time (in years between assessments) by HIV status between baseline and FU1 (MPHEU = 1.09, SD = 0.42, MPHIV+ = 1.28, SD = 0.63; t = −3.08, p = 0.005), and FU1 and FU2 (MPHEU = 2.46, SD = 1.06, MPHIV+ = 3.19, SD = 1.35; t = −4.48, p <0.001). This difference is accounted for in our analytic models as youths’ HIV status and age at each follow-up are included as covariates (see Data Analytic Strategy).

Measures

Substance use symptoms, the primary outcome in this study, were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; child and young adult versions) [43], an extensively used and well-validated measure of DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses [44]; note these data were collected prior to DSM V. The substance use symptoms were computed as a sum of symptoms related to alcohol [range: 0–14; meanbaseline = 0.57 (0.9); meanFU1 = 1.12 (1.2); meanFU2 = 1.23(1.8)], marijuana [range: 0–12; meanbaseline = 0.14 (0.9); meanFU1 = 0.12 (0.7); meanFU2 = 0.46 (1.4)], and “other drug/substance” use [range: 0–18; mean baseline = 0(0); meanFU1 = 0(0); meanFU2 = 0.02 (0.4)] in the DISC-IV questionnaire; note that the means (and standard deviations) were computed among youth who endorsed any substance use symptoms. Of note, these analyses utilize only youth report of substance use data which has been shown to be reliable [45] and preferable since caregivers may not be aware of youths’ substance use [46].

Internal context factors included youths’ age, gender, HIV status, and race/ethnicity

Youths’ HIV status was determined via medical charts and clinician verification. At baseline, youths self-identified their race based on their ethnic/cultural heritage (e.g. Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Caribbean French), and these were collapsed into four racial/ethnic categories (see Table 1): Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and Other. Given the small distribution of Non-Hispanic Whites and Other Race/Ethnicity participants, these two categories were collapsed into a single race/ethnicity category in our multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of youths stratified by HIV status (N = 325)

| Characteristic | PHIV+ (N = 196)

|

PHEU (N = 129)

|

t-test/χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | ||

| Internal context factors | |||||

| Age | 12.29 (2.18) | 11.92 (2.33) | −1.403 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 98 (50.0) | 65 (50.4) | 0.01 | ||

| Females | 98 (50.0) | 64 (50.0) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-hispanic black/African-American | 91 (46.7) | 58 (44.6) | 1.53 | ||

| Non-hispanic white | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Hispanic | 97 (49.7) | 68 (52.3) | |||

| Other | 5 (2.6) | 4 (3.1) | |||

| External context factors | |||||

| Type of caregiver | |||||

| Biological | 68 (34.7) | 90 (69.8) | 38.31*** | ||

| Non-biological | 128 (65.3) | 39 (30.2) | |||

| Household income | |||||

| Below NY poverty line | 132 (71.0) | 113 (90.4) | 16.50*** | ||

| Above NY poverty line | 54 (29.0) | 12 (9.6) | |||

| Caregiver HIV status | |||||

| Positive | 134 (71.3) | 113 (90.4) | 42.42 *** | ||

| Negative | 54 (28.7) | 12 (9.6) | |||

| Caregiver depression | |||||

| Baseline | 7.19 (7.16) | 8.82 (8.52) | 1.84 | ||

| FU1 | 7.53 (7.56) | 7.88 (7.70) | 0.36 | ||

| FU2 | 7.25 (6.68) | 9.08 (8.56) | 1.63 | ||

| Major life events | |||||

| Baseline | 6.40 (5.95) | 6.10 (4.78) | −0.48 | ||

| FU1 | 12.51 (14.88) | 10.59 (12.95) | −1.20 | ||

| FU2 | 12.70 (13.88) | 15.95 (15.88) | 1.90 | ||

| Neighborhood stress | |||||

| Baseline | 9.87 (7.59) | 11.64 (9.01) | 1.85 | ||

| FU1 | 11.10 (8.74) | 11.79 (8.58) | 0.65 | ||

| FU2 | 13.58 (10.28) | 14.66 (9.70) | 0.85 | ||

| Self-regulation | |||||

| Future orientation | 0.08 (0.98) | 0.12 (1.03) | 1.73 | ||

| Substance use | |||||

| Prevalence of any substance use in the past year, excluding nicotine | |||||

| Baseline | 5 (2.55) | 9 (6.98) | 3.98 | ||

| FU1 | 11 (5.61) | 6 (4.65) | 0.45 | ||

| FU2 | 40 (20.41) | 13 (10.08) | 4.37 | ||

| Mean number of symptoms at each wave among youth who endorsed any substance use symptoms (excluding nicotine) | |||||

| Baseline | 5 (35.71) | 3.80 (2.59) | 9 (64.29) | 4.11 (3.10) | 0.19 |

| FU1 | 11(64.71) | 3.18 (2.04) | 6 (35.29) | 2.83 (1.47) | −0.37 |

| FU2 | 40 (75.47) | 3.55 (2.42) | 13 (24.53) | 4.54 (4.33) | 0.78 |

p <0.10

P < 0.05

p < 0.001

External context factors included caregiver HIV status, type of caregiver (birth parent vs. non-birth parent caregiver), caregiver depression, household poverty, major life events, and neighborhood stress

Caregiver HIV status was assessed using self-report data about personal HIV tests and results (HIV infected vs. uninfected/untested). Caregiver depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory [47], a 21-item self-report measure of the presence and intensity of depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, loss of interest, guilt, suicidality, and vegetative changes (our sample, α = 0.89). Household poverty (living below or above the New York State poverty line) was based on household income adjusted for the number of household members. Major life events were assessed using an instrument developed at a mental health program for families affected by HIV [48]. This 46-item checklist (our sample, α = 0.86) assesses events related to one’s family (e.g. increase arguments between parents), self (e.g. major illness), or peers (e.g. having a close friend with a drug problem). Participants rated the impact of each event (i.e., bad, neutral, and good). A total score was computed as the sum of the impact ratings of all items designated by the respondent as “bad,” with higher scores reflecting more adverse stressful life events. Neighborhood stress was measured using the City Stress Inventory [49], a 16-item index that assesses neighborhood disorder and exposure to violence (our sample, α = 0.86) using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = often). Neighborhood stress was computed as the mean score of these stressors.

Self-regulation The factor included in these analyses was youths’ future life orientation

Of the available indicators in the larger study, future orientation was chosen as the best indicator for this sub-analysis because it captures the motivation domain of the self-regulatory processes, and its conceptual relevance among youth has been documented in varied studies: future orientation has been identified as a protective factor in low-income and minority youth, with several benefits including resilience against stressors, positive socio-emotional adjustment, and reduced risk for risky behaviors [50–53]. Future orientation was assessed using items adapted from Monitoring the Future [54], which assesses youths’ perceptions about the probability of completing school, getting employment, getting married, having children, making money, and moving out of their neighborhood (our sample, α = 0.61).

Data Analytic Strategy

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to compare baseline characteristics between PHIV+ and PHEU youths, and to assess the relationship (Chi squares and t-tests for binary and continuous data as appropriate) between predictor variables (e.g. age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income) and substance use symptoms. Results of these analyses indicated that caregiver HIV status and type of caregiver (i.e., birth parent) were confounded, reflecting the fact that 100 % of birth mothers were by definition HIV-positive and almost all birth parents participating in the study were the mother. Therefore, caregiver HIV status was not included in the analyses. Given that 30 % of our sample had more than one participant per family, we also included having a sibling in the study as a covariate in these analyses.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; v. 7.0) was used to fit a multilevel linear growth curve model of the change (i.e., increase or decrease) in substance use symptoms over time. While a repeated regression performs list-wise deletion for cases with missing values in one or more data points, HLM maximizes all available data because its algorithms do not require information across all follow-ups to compute growth estimates for all participants [55]. Therefore, all N = 325 cases were used in this analysis. We modeled changes in substance use symptoms over time by including variables at Level 1 (i.e., time-varying covariates, e.g. time, major life events, household poverty, caregiver depression, and neighborhood stress) and Level 2 (i.e., person-centered baseline characteristics, e.g. age, sex, race, ethnicity, youths’ HIV status, type of caregiver, and future orientation score). The HLM analysis was conducted in three analytic steps: (1) we examined the relationship between youths’ socio-demographic characteristics and substance use symptoms at baseline; (2) we assessed variation in youths’ substance use symptoms across the three waves and assessed the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on these changes; and (3) we utilized a mixed model to examine the influence of psychosocial stressors on changes in youths’ substance use symptoms, adjusting for baseline socio-demographic characteristics. For brevity, we present our final models below (p <0.05).

Results

Socio-Demographics

A summary of the baseline internal and external context factors, self-regulation variable, and substance use symptoms at baseline and follow-up, for both PHIV+ and PHEU youths, is presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between PHIV+ and PHEU youths in age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The majority (75.4 %) of youths (both PHIV+ and PHEU) were living below the New York State Poverty line, but PHEU youths were less likely to live below the poverty line compared to PHI-V+ youths (χ2 = 16.50; p ≤ 0.001). With regard to care-giver type, significantly fewer PHIV+ youths were living with a biological caregiver (34.7 vs. 69.8 %; χ2 = 38.31; p ≤ 0.001), and thus, fewer PHIV+ youths were living with a HIV + caregiver compared to PHEU youths, as 100 % of birth mothers were HIV positive. There were no differences in caregiver depression, major life events and neighborhood stress by youth HIV status. Similarly, there were no differences in future orientation by youth HIV status at baseline.

Substance Use and Symptoms

As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of any past year substance use (excluding nicotine use) was low at baseline and increased at each follow-up assessment for PHI-V+ and PHEU youths; there were no significant differences in prevalence of any past year substance use between PHIV+ and PHEU youths at any time point. In cross-sectional analyses, among substance-using youths, prevalence of at least one symptom was reported in approximately one-third of PHIV+ youths (35.7 %; n = 5) and two-thirds of PHEU youths (4.3 %; n = 9). Among PHI-V+ youth, prevalence increased at each follow-up assessment (64.7 %; n = 11 at FU1 and 75.5 %; n = 40 at FU2), but it decreased among PHEU youths (35.3 %; n = 6 at FU1 and 24.5 %; n = 13 at FU2). Marijuana use symptoms were the most prevalent symptoms reported at each assessment point (baseline: 7(5.2 %) of PHEU and 4(1.9 %) of PHIV+ ; FU1: 4(3.5 %) of PHEU and 6(3.6 %) of PHIV+ ; and FU2: 7(6.7 %) of PHEU and 30(16.8 %) of PHIV+), followed by alcohol use symptoms (baseline: 3 (2.2 %) of PHEU and 2 (1.0 %) of PHIV+ ; FU1: 3 (2.6 %) of PHEU and 8 (4.8 %) of PHIV+ ; and FU2: 9 (8.6 %) of PHEU and 21 (11.7 %) of PHIV+). In unadjusted bivariate analyses, the difference in the mean number of substance use symptoms between PHIV+ and PHEU youths was not statistically significant at any assessment point (see Table 1).

HIV-Related Indicators

As shown in Table 2, more than 60 % of PHIV+ youth were virally suppressed (i.e., HIV viral load of less than 200 copies/mL [56]) across the three time points, although the proportion of virally suppressed youth reduced slightly with each successive assessment. Similarly, the proportion of PHIV+ youth with CD4 cell counts less than 500 cells/mm3 increased across the study. Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTI) were the predominant type of anti-retroviral drug.

Table 2.

Descriptive summary of HIV-related indicators for perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) youth (N = 196)

| Baseline N (%) | Follow-up 1 (FU2) N (%) | Follow-up 2 (FU2) N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion virally suppresseda | 130 (66.3) | 128 (65.3) | 121 (61.7) |

| CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | |||

| <500 | 79 (40.3) | 83 (51.2) | 91 (55.8) |

| 501–1000 | 91 (46.4) | 64 (39.5) | 56 (34.3) |

| >1000 | 26 (13.3) | 15 (9.3) | 16 (9.8) |

| Proportion on ART | 166 (86.0) | 133 (82.9) | 151 (91.0) |

| Type of ART regimenb | |||

| NNRTI | 40 (24.1) | 23 (11.7) | 42 (21.4) |

| PI | 101 (60.8) | 70 (35.7) | 98 (50.0) |

| NRTI | 160 (96.4) | 97 (49.5) | 135 (68.9) |

| Otherc | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.5) | 27 (13.8) |

| Proportion of Efavirenzb | 21 (12.6) | 11 (8.3) | 23 (15.2) |

NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; P1 protease inhibitor; NNRTI Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

Viral suppression defined as HIV viral load of less than 200 copies/mL [56]

Computed as proportion of respondents on ART

Other includes entry and fusion inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, CCR5 inhibitors

Growth Curve Modeling

Substance use symptoms were significantly associated with youths’ age and HIV status (internal context) at baseline (i.e., mean intercept). As noted in Table 3, substance use symptoms were higher among older youth [b = 0.07 (SE = 0.02); p < 0.001]. PHIV+ youths reported fewer substance use symptoms than PHEU youths [b = −0.21 (SE = 0.10); p < 0.001]. Race/ethnicity and gender were not significantly associated with youths’ substance use symptoms, nor were type of caregiver (external context) or future orientation (self-regulation).

Table 3.

Prospective changes in substance use symptoms among PHIV+ and PHEU youths

| Fixed effect | Substance use symptoms

|

|

|---|---|---|

| b | SE | |

| Mean score at baseline, β00 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| Age at baseline, β01 | 0.07*** | 0.02 |

| HIV-positive, β02 | −0.21** | 0.10 |

| Females, β03 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| CG is bioparent, β04 | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| African American, β05 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

| Latino, β06 | 0.09 | 0.21 |

| Baseline future orientation (z-score), β07 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Having sibling in the study, β08 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Linear change across waves, β10 | −0.13 | 0.32 |

| HIV-positive, β11 | 0.33** | 0.14 |

| Females, β12 | −0.06 | 0.13 |

| CG is bioparent, β13 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| African American, β14 | 0.05 | 0.29 |

| Latino, β15 | 0.06 | 0.29 |

| Baseline future orientation (z-score), β16 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Living in poverty over time, β20 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Caregiver depression over time, β30 | 0.001 | 0.01 |

| Environmental stressors over time, β40 | 0.008 | 0.01 |

| Count of negative life events over time, β50 | 0.01*** | 0.01 |

p <0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

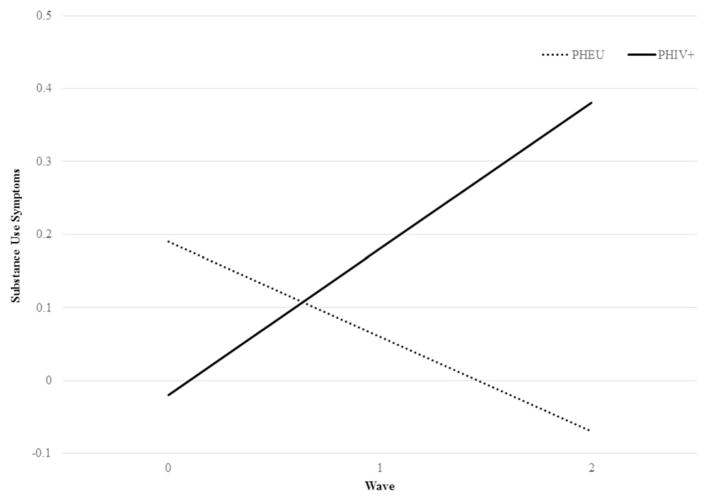

After adjusting for baseline differences in our growth curve models, the overall change in youths’ substance use symptoms followed a linear relationship over time (see Fig. 1). This linear relationship, however, was only observed for PHIV+ youths. Compared to PHEU youths who had no linear change in substance use symptoms over time, PHIV+ reported an increase in substance use symptoms over time [b = 0.33 (SE = 0.14); p < 0.001]. Among the internal and external contextual factors and the self-regulation factor assessed as time-varying covariates, only major negative life events was significantly associated with the changes in substance use symptoms among PHI-V+ and PHEU youths across time [b = 0.01 (SE = 0.01); p <0.001].

Fig. 1.

Prospective changes in substance use symptoms among PHIV+ and PHEU youths

Discussion

This study assessed the changes in substance use symptoms among PHEU and PHIV+ youths and examined the factors associated with changes in youths’ substance use symptoms across time. Substance use symptoms were positively associated with youths’ age and negatively associated with youths’ HIV status at baseline, and positively associated with number of negative life events experienced and youths’ HIV status over time. The public health consequences of substance use among PHIV+ and PHEU youths [6, 7, 15–18, 57, 58] underscore the need for both primary (preventive) and secondary (treatment) interventions to eliminate substance use among both PHIV+ and PHEU youths. These analyses also utilize substance use symptoms rather than the onset of substance use disorders, which characterizes our earlier work among PHIV+ and PHEU youths. Substance use disorders are less common during adolescence. Therefore, a focus on substance use symptoms allows us to more accurately describe the significant substance use experimentation that typically begins in this developmental stage. This approach is useful in understanding what predicts changes in substance use symptoms among youths whose substance use symptoms may not meet DSM diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders, but nonetheless exhibit problematic substance use behaviors that require attention. Given that substance use typically emerges in adolescence and worsens in young adulthood [23], understanding the symptoms and associated factors is critical to developing substance use prevention programs to mitigate the primary and secondary HIV risk challenges among PHEU and PHIV+ youths.

Prior studies have not found any statistically significant differences in substance use and substance use disorders between PHIV+ and PHEU youths [7, 11, 19, 20], thus concluding that HIV status alone, may be inconsequential in the development of substance use disorders among PHIV+ and PHEU youth. However, in this study, we found that youths’ HIV status influences substance use symptoms over and above the influence of other key contextual factors that were also significantly associated with substance use symptoms (e.g. negative life events). Although PHIV+ youths reported fewer substance use symptoms than PHEU youths at baseline, the onset of substance use symptoms increased at a faster rate among PHIV+ youth as they transitioned through adolescence compared to PHEU youths. This findings is consistent with the prior reports that chronically ill adolescents are just as likely as or even more likely than their “healthy” peers to report substance use [59]. The higher burden of substance use symptoms among PHIV+ youths could be attributed to various disease-related factors. For example, PHI-V+ youths may utilize substance use as a mechanism for coping with the physical pain or fear of dying, or to forget about their illness [60]. Moreover, substance use among PHIV+ youths could also be attributed to management of developmental and psychosocial stressors (e.g. the desire to fit in, to feel “normal,” peer pressure). Alternatively, over-protection by caregivers or withdrawal of PHIV+ youths from social circles as a strategy for managing their stigmatized identity may deprive them of the opportunity to acquire knowledge and develop skills to negotiate developmentally normative pressures to engage in substance use. These developmental and psychosocial stressors may act in concert with illness-related stressors to increase PHI-V+ youths’ vulnerability to substance use.

Similar to prior studies conducted among youth [61–64], including PHIV+ and PHEU youths [19], we found that a higher experience of negative life events was associated with increased number of substance use symptoms. The most frequently reported negative life events at each assessment point were death of a family member, getting a failing grade, hearing gunshots on your block, loss of a close friendships, witnessing drug deals on your block, witnessing a fight involving a weapon, and breaking up with a girlfriend or boyfriend. However, type of caregiver, household poverty, caregiver depression and neighborhood stressors were not significantly associated with adolescents’ substance use symptoms, irrespective of youth’s HIV status. These findings suggest that substance use among PHIV+ and PHEU youths is associated with acute (or abrupt) life events within youths’ family and peer networks rather than chronic stressors (e.g. household poverty and neighborhood violence), and that youths may be utilizing maladaptive coping strategies (e.g. substance use) to manage these acute life events [64, 65]. Prior studies have found that youth initiate substance use as a means of coping with a variety of stressors and influences in their socio-ecological contexts [61, 66, 67], and that the likelihood of substance use among youth is a function of the stress levels and the extent to which this stress level is offset by stress moderators, social networks, social competencies, and resources [68]. PHIV+ and PHEU youths must develop strategies to cope with the chronic life stressors (e.g. household poverty, neighborhood stressors, and poor caregiver mental health), and this may explain why we did not observe an association between these stressors and substance use symptoms. Conversely, when exposed to acute and unforeseen negative life events, youths living in a context of limited resources may find it more difficult to effectively mobilize the resources required to cope with negative life events, hence resorting to mal-adaptive coping strategies such as substance use. Alternatively, the relationship between negative life events and substance use symptoms could represent a feedback loop: substance use increases youths’ exposure to negative life events (e.g. violence and trauma), which in turn increases the likelihood of substance use. Our findings affirm the impact of stressors on the wellbeing of PHIV+ and PHEU youths. These findings suggest a need for early life intervention programs to equip PHIV+ and PHEU youths with a repertoire of life skills to navigate the myriad chronic and acute stressors they may experience.

Our findings highlight the selective vulnerability of PHIV+ youths across adolescence, but several critical gaps persist in our understanding of the development of substance use symptoms among PHIV+ youths, particularly with regard to HIV mediated effects and the role of self-regulatory factors on substance use. First, HIV infection has been associated with neurocognitive changes in the subcortical white matter and frontostriatal systems involved in regulation of mood and behavior [69], which increase PHIV+ youths’ vulnerability to mental health problems. However, the association between HIV infection and substance use, especially of marijuana, the most prevalent substance used in this current sample, remains largely unexamined. Therefore, the extent to which HIV related neurocognitive changes could increase PHI-V+ youths’ susceptibility to marijuana abuse and dependence is not known. Additionally, there is a need for future studies to examine the impact of different ART regimens on substance use and mental health problems, particularly for medications such as Efavirenz that cross blood–brain barrier and have been associated with adverse neuropsychiatric effects [70–72].

Additionally, our analyses explore a limited set of self-regulatory factors (i.e., future life orientation), but there is a need to expand the range of self- and social regulatory factors (e.g. stigma, cognitive functioning, self-efficacy re: negotiating peer pressure) in order to advance our understanding of the factors that increase or decrease PHI-V+ youths’ vulnerability to substance use. The increase in substance use among youths, particularly PHIV+ youths, raises several public health concerns, given the association of substance use with sexual risk behaviors, including condomless sex, which may result in onward transmission of HIV [73, 74], as well as non-adherence to ART, which may result in treatment failure and increased risk for HIV transmission [7, 8, 11, 13, 14]. Moreover, there are few evidence-based psychosocial interventions for PHI-V+ youths [32], and there is a lack of evidence-based interventions targeting co-morbidity of HIV and substance use in this population [75]. Our findings suggest a need for early substance use prevention and treatment interventions to mitigate this heightened vulnerability as they transition through adolescence. There is also a need for studies to examine the association between HIV-related neurocognitive changes and substance use and dependency among PHIV+ youths. This research is relevant for developing effective prevention and treatment interventions for PHIV+ youths.

Finally, our findings suggest multi-level interventions to address the multiplicity of risk factors for substance use across PHIV+ and PHEU youths’ ecological contexts are necessary. Future research could expound on stress moderators, social networks, social competencies, and resources that influence substance use among PHIV+ and PHEU youths. Studies should also explore possible associations between HIV-related neurocognitive deficits and marijuana use and dependency among PHIV+ youths. Given the high rates of marijuana use in this population, it would be important for future studies to assess use of other substances particularly tobacco and nicotine products in their increasing diverse forms e.g. hookah, e-cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, etc. These products are often used in conjunction with marijuana to manage stress in adolescents and young adults and thus of increasing concern [76–79].

This study is not without limitations that could impact interpretations of study findings. Participants were recruited from HIV primary care clinics, which may limit generalization findings to youth in other settings. Although we recruited and interviewed 76 % of eligible participants in the study recruitment sites, this convenience sample may not reflect the large population of PHIV+ and PHEU youths, particularly those outside of NYC and youths who are not followed in HIV clinics. Although we attempted to recruit PHIV+ and PHEU youths from similar communities based on the demographics of pediatric HIV disease, other factors (e.g. access to services) may have altered group effects. Due to human subject protections, we were not able to collect data on patients who refused contact, so we are not in a position to adjust our analyses for any recruitment bias. This study also utilized self-report instruments, which are susceptible to reporting bias, especially for sensitive topics such as substance use. Lastly, we did not explore the role of biological/genetic factors, which could influence youths’ substance use symptoms.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Despite these limitations, the findings from the present study have several important clinical and policy implications, as they provide important insights into the long-term changes in substance use symptoms among PHIV+ and PHEU youths, highlighting the sources of vulnerability to substance use in this population. Similar to patterns seen in other populations, substance use and substance use symptoms increased over time for both groups. However, PHI-V+ youths experienced a greater increase in substance use symptoms over time compared to PHEU youths. To date, substance abuse treatment programs developed specifically for PHIV+ youth are not available. Therefore, there is a great need to develop or tailor existing interventions to the developmental stage and HIV-specific needs of these youths, in order to promote positive developmental outcomes. Within primary care settings, comprehensive public health approaches such as the Screening, Brief Interventions and Referral (SBIRT) have shown some promise in evaluating and intervening with adolescents at risk for problematic alcohol and substance use [80]. Such approaches, with some tailoring to accommodate the unique needs of PHIV+ youths, could be adapted within primary care adolescent HIV clinics. Health care providers are in a unique position to utilize the routine clinic visits of PHI-V+ youths engaged in care as an opportunity to assess for substance use issues and associated psychosocial risk factors, and address them accordingly. A similar approach may not be feasible for PHEU youths, since they are not followed in HIV clinics and often are not as connected to regular health care, mental health care, or other support services as their PHIV + counterparts. However, medical providers in adult clinics may serve a key role in reaching these youth. Providers may discuss the increased risk of substance use in PHEU adolescents with their adult HIV+ patients with adolescent children, and suggest or refer these youths for assessment and intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH63636; PI: Claude Ann Mellins, Ph.D.), and a center Grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (P30MH43520; Center PI: Robert H Remien, Ph.D.).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest All authors do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at all study sites. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1619–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339(6122):966–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, et al. Psychological adjustment, substance use, HIV knowledge, and risky sexual behavior in at-risk minority females: developmental differences during adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(4):373–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Santamaria EK, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Substance use and the development of sexual risk behaviors in youth perinatally exposed to HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(4):442–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tapert SF, Aarons GA, Sedlar GR, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and sexual risk-taking behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(3):181–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-exposed youth: roles of caregivers, peers and HIV status. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(2):133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapetanovic S, Wiegand RE, Dominguez K, et al. Associations of medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and risky health behaviors in highly active antiretroviral therapy-experienced perinatally HIV-infected youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(8):493–501. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conner LC, Wiener J, Lewis JV, et al. Prevalence and predictors of drug use among adolescents with HIV infection acquired perinatally or later in life. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):976–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9950-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu CS, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1131–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams PL, Leister E, Chernoff M, et al. Substance use and its association with psychiatric symptoms in perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-affected adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1072–82. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao D, Kekwaletswe T, Hosek S, Martinez J, Rodriguez F. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19(1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120600652303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naar-King S, Templin T, Wright K, Frey M, Parsons JT, Lam P. Psychosocial factors and medication adherence in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(1):44–7. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner EM, Burman WJ, Steiner JF, Anderson PL, Bangsberg DR. Antiretroviral medication adherence and the development of class-specific antiretroviral resistance. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1035. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ba8ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiener LS, Battles HB, Wood LV. A longitudinal study of adolescents with perinatally or transfusion acquired HIV infection: sexual knowledge, risk reduction self-efficacy and sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(3):471–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9162-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koenig LJ, Pals SL, Chandwani S, et al. Sexual transmission risk behavior of adolescents with HIV acquired perinatally or through risky behaviors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(3):380–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f0ccb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nugent NR, Brown LK, Belzer M, Harper GW, Nachman S, Naar-King S. Youth living with HIV and problem substance use: elevated distress is associated with nonadherence and sexual risk. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2010;9:113–5. doi: 10.1177/1545109709357472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alperen J, Brummel S, Tassiopoulos K, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for substance use among perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected and perinatally exposed but uninfected youth. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS patient care STDs. 2011;25(7):413–22. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Leu C-S, et al. Prevalence and change in psychiatric disorders among perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-exposed youth. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):953–62. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merikangas KR, McClair VL. Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Hum Genet. 2012;131(6):779–89. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Racial/ethnic disparities among children with diagnoses of perinatal HIV infection-34 states, 2004–2007. MMWR. 2010;59(4):97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. HIV Surveillance—United States, 1981–2008. MMWR. 2011;60(21):689–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denning P, DiNenno E. Communities in crisis: is there a generalized HIV epidemic in impoverished urban areas of the United States. Paper presented at: XVIII international AIDS conference; July 18–23, 2010; Vienna, Australia. Abstract WEPDD103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(4):444, e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141(1):105–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Compas BE, Banez GA, Malcarne V, Worsham N. Perceived control and coping with stress: a developmental perspective. J Soc Issues. 1991;47(4):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke AT. Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35(1):10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Valentin C, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: the role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(10):1065–75. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11):1035–41. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143646.15240.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy DA, Moscicki AB, Vermund SH, Muenz LR Network AMHAR. Psychological distress among HIV+ adolescents in the REACH study: effects of life stress, social support, and coping. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(6):391–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, et al. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1533–44. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.575120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Miller NL. Life events, neighborhood stress, psychosocial functioning, and alcohol use among urban minority youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abus. 2000;9(1):19–50. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fielden SJ, Sheckter L, Chapman GE, et al. Growing up: perspectives of children, families and service providers regarding the needs of older children with perinatally-acquired HIV. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1050–3. doi: 10.1080/09540120600581460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):18593. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown SA, Tomlinson K, Winward J. Substance use disorders in adolescence. In: Beauchaine TP, Hinshaw SP, editors. Child and adoelscent psychopathology. 2. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013. pp. 489–510. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, Garland AF, Wood PA. Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):419–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. Am Psychol. 1991;46(9):931. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preciado J, Henry M. Linguistic barriers in health education and services. In: Garcia JG, Zea MC, editors. Psychological interventions and research with Latino populations, Chapter 13. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1997. pp. 235–54. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Psychological Association A. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV: American Psychiatric Association. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenbaum JE. Truth or consequences: the intertemporal consistency of adolescent self-report on the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(11):1388–97. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams RJ, McDermitt DR, Bertrand LD, Davis RM. Parental awareness of adolescent substance use. Addict Behav. 2003;28(4):803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT. Beck depression inventory. San Antonio: The Psychological Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellins CA, Havens J, Kang E. Child psychiatry service for children and families affected by the HIV epidemic. Paper presented at: IX International AIDS Conference; Berlin, Germany. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Health Psychol. 2002;21(3):254. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyman PA, Cowen EL, Work WC, Kerley JH. The role of children’s future expectations in self-system functioning and adjustment to life stress: a prospective study of urban at-risk children. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5(04):649–61. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seginer R. Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: how resilient adolescents construct their future. Int J Behav Dev. 2008;32(4):272–82. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aspinwall LG. The psychology of future-oriented thinking: from achievement to proactive coping, adaptation, and aging. Motiv Emot. 2005;29(4):203–35. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seiffge-Krenke I, Aunola K, Nurmi JE. Changes in stress perception and coping during adolescence: the role of situational and personal factors. Child Dev. 2009;80(1):259–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson LD, O’Malley P, Bachman J. National survey results on drug use from the monitoring the future study, 1975–1997. Rockville: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. New York: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Health Resources and Services Administration H. [Accessed 27 Apr 2016];HIV/AIDS Bureau performance measures. 2013 http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliverhivaidscare/coremeasures.pdf.

- 57.Barnes GM, Welte JW, Hoffman JH. Relationship of alcohol use to delinquency and illicit drug use in adolescents: gender, age, and racial/ethnic differences. J Drug Issues. 2002;32(1):153–78. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suris JC, Parera N. Sex, drugs and chronic illness: health behaviours among chronically ill youth. Eur J Pub Health. 2005;15(5):484–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.King G, Delaronde SR, Dinoi R, Forsberg AD Committee HBIEP. Substance use, coping, and safer sex practices among adolescents with hemophilia and human immunodeficiency virus. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18(6):435–41. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(96)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nation M, Heflinger CA. Risk factors for serious alcohol and drug use: the role of psychosocial variables in predicting the frequency of substance use among adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 2006;32(3):415–33. doi: 10.1080/00952990600753867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Low NC, Dugas E, O’Loughlin E, et al. Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Windle M, Mun EY, Windle RC. Adolescent-to-young adulthood heavy drinking trajectories and their prospective predictors. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(3):313–22. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158(4):343–59. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fishbein DH, Herman-Stahl M, Eldreth D, et al. Mediators of the stress–substance–use relationship in urban male adolescents. Prev Sci. 2006;7(2):113–26. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(01):119–37. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, Morris J. Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):569–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhodes JE, Jason LA. A social stress model of substance abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(4):395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharer L, Gendelman H, Grant I, Everall I, Lipton S, Swindells S. Neuropathological aspects of HIV-1 infection in children. Neurol AIDS. 2005:659–65. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gutiérrez F, Navarro A, Padilla S, et al. Prediction of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with long-term efavirenz therapy, using plasma drug level monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(11):1648–53. doi: 10.1086/497835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Munoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with efavirenz: prevalence, correlates, and management. A neurobehavioral review. AIDS Rev. 2009;11(2):103–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lochet P, Peyriere H, Lotthe A, Mauboussin J, Delmas B, Reynes J. Long-term assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse reactions associated with efavirenz. HIV Med. 2003;4(1):62–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wainberg MA, Friedland G. Public health implications of antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance. JAMA. 1998;279(24):1977–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wheeler WH, Ziebell RA, Zabina H, et al. Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance associated mutations and HIV-1 subtypes in new HIV-1 diagnoses, US–2006. AIDS. 2010;24(8):1203–12. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283388742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murphy DA, Chen X, Naar-King S. Parsons for the adolescent trials network JT. Alcohol and marijuana use outcomes in the healthy choices motivational interviewing intervention for HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(2):95–100. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The origins of the correlations between tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use during adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39(07):995–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Lynskey M. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1518–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use among Australians: a comparison of their associations with other drug use and use disorders, affective and anxiety disorders, and psychosis. Addiction. 2001;96(11):1603–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961116037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Degenhardt L, Hall W. The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: results from the national survey of mental health and well-being. Nicot Tob Res. 2001;3(3):225–34. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. SBIRT for adolescent drug and alcohol use: current status and future directions. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44(5):463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]