Abstract

Aims

Mechanisms underlying pain perception and afferent hypersensitivity, such as central sensitization, may impact overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms. However, little is known about associations between OAB symptom severity, pain experience, and presence of comorbid chronic pain syndromes. This study examined relationships between OAB symptoms, somatic symptoms, and specific chronic pain conditions in which central sensitization is believed to play a primary role, in a community-based sample of adult women with OAB

Methods

We recruited adult women with OAB to complete questionnaires assessing urinary symptoms, pain and somatic symptoms, and preexisting diagnoses of central sensitivity syndromes. We analyzed the effects of overall bodily pain intensity, general somatic symptoms, and diagnoses of central sensitivity syndromes on OAB symptom bother and health-related quality of life.

Results

Of the 116 women in this study, over half (54%) stated their urge to urinate was associated with pain, pressure, or discomfort. Participants reported a wide range of OAB symptoms and health-related quality of life. There was a significant, positive correlation between OAB symptoms and somatic symptoms as well as overall pain intensity. Only 7% of women met diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia; yet these women demonstrated significantly increased OAB symptom burden and decreased OAB quality of life compared to those without fibromyalgia.

Conclusion

Women with more severe OAB symptoms reported increased general somatic symptom burden and increased overall body pain intensity, especially women with fibromyalgia. These findings suggest that attributes of pain and co-morbidity with chronic pain conditions may impact the experience of OAB symptoms for many women.

Mesh Terms: overactive bladder, urge urinary incontinence, central sensitization, fibromyalgia, functional somatic disorders

Introduction

The pathophysiology of idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) remains unclear, yet some authors have proposed that OAB may have a sensory hypersensitivity component related to dysfunctional afferent hyperactivity (1–3). While pain is not considered characteristic of OAB, up to 40% of women with OAB will describe urgency as being due to pain, pressure, or discomfort, as opposed to attributing it to fear of incontinence (3, 4). These data suggest the possibility that mechanisms underlying pain perception and afferent hypersensitivity contribute to the clinical manifestations of OAB. Nevertheless, very little is known about associations between OAB symptoms and pain.

Central sensitization is postulated to underlie the pathophysiology of a range of chronic pain and somatic conditions, collectively referred to as central sensitivity syndromes (CSS) (5–7). Central sensitization is an induced state of spinal hypersensitivity and a well-recognized mechanism of centrally amplified pain perception, with some similarities to pathophysiologic mechanisms believed to contribute to OAB (8). These syndromes often manifest with greater somatic symptom burden, considerable morbidity, and lower quality of life, especially when multiple CSS occur in the same individual (5). CSS include conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraine, temporomandibular disorders (TMD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), and idiopathic low back pain (6).

Prior data suggest that OAB frequently overlaps with some CSS such as IBS (9–12), fibromyalgia (13, 14), and idiopathic back pain (15), which raises the possibility of common disease mechanisms. Indeed, some authors have proposed that the observed overlap in OAB and IBS reflects a common pathophysiology (12). For many CSS, associations with OAB or urinary conditions have not been studied, yet co-morbidity may be an important clinical finding to phenotype OAB patients (16). Whether severity of OAB symptoms is associated with intensity of general bodily pain or multiple co-morbid CSS have to our knowledge not previously been examined.

Given these knowledge gaps surrounding interrelationships among OAB, pain symptoms, and pain conditions, the objective of this study was to examine the relationships between OAB symptoms, somatic symptoms, and chronic pain conditions (i.e. CSS) in a community-based sample of adult women with OAB. We hypothesized that women with greater OAB symptom burden would demonstrate associations with greater bodily pain, greater somatic complaints, and more frequent co-morbid CSS.

Materials and Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, we recruited a community-based sample of adult women self-reporting OAB symptoms from an institutional research study recruitment service and asked them to complete an anonymous, electronic survey. Our institution maintains a list of Institutional faculty and staff and volunteer community members that can be used for study participant recruitment, known as the Research Notification Distribution List. Specific details on demographics are not available, but the list contains over 18,500 individuals who receive daily email advertisements of research study opportunities. Inclusion criteria included women 18 or older with a presumptive diagnosis of OAB based on a score of ≥4 on the OAB-V3 awareness tool, a validated 3-item screening tool with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 91% for OAB diagnosis (17). Women were excluded if they reported diagnoses of neurologic conditions that might contribute to their urinary symptoms (i.e. spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke) or had a history of bladder cancer, pelvic irradiation, or bowel diversions. We also excluded women who reported being previously diagnosed with IC/BPS. Participants were incentivized to participate in the study with a random drawing of retail gift cards.

Participants completed several questionnaires assessing demographics, lower urinary tract symptoms, and co-morbid pain conditions. The Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OABq) is a psychometrically-validated questionnaire comprised of two subscales that assesses symptom bother and health-related quality of life over the previous 7 days (18). We used the 8-item symptom scale OABq-SS (18) and the 13-item OABq-HRQL scale (19), each transformed to a 100-point score. A higher score on the OABq-SS reflects increased bother of OAB symptoms, while a lower score on the OABq-HRQL reflects a greater negative effect of OAB on health-related quality of life. A difference of 10 points for these transformed scores is considered to be clinically meaningful. The survey also included a single item from the Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology questionnaire: “Would you say your urge to urinate is mainly because of pain, pressure, or discomfort or because you are afraid you will not make it to the bathroom in time to avoid wetting?”(4)

The Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS8) is an 8-item instrument that assesses the presence and severity of somatic symptoms experienced in the preceding 7 days, including: stomach/bowel problems; back pain; pain in arms, legs, or joints; headaches; chest pain or shortness of breath; dizziness; feeling tired or low energy; and trouble sleeping (20). Severity is graded on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) and is scored by summing the responses (range 0 to 32). Reponses can be categorized into no/minimal (0–3), low (4–7), medium (8–11), high (12–15), and very high (16–32) somatic symptom burden. The SSS8 has previously been validated as a reliable self-reported measure of somatic symptom burden in population-based studies.

The NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain intensity instrument is 3-item tool that measures the intensity of generalized, full body pain in the preceding 7 days at its worst, the average pain, and the present level of pain on an ordinal scale from 1 (none) to 5 (very severe). The instrument is scored using item-level calibrations through the PROMIS Assessment Center Scoring Service. The final score is represented by a T-score, a standardized score with a mean of 50 and a 10-point standard deviation calibrated to the general U.S. population. A higher score represents more severe pain intensity.

Finally, we assessed the presence of CSS by self-report of a prior diagnosis or by validated patient-reported diagnostic measures, when available, including: a 3-item migraine headache screening tool (21); the proposed modified American College of Rheumatology (ACR) diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia (22); and the Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (23). Chronic pelvic pain was defined as: “pelvic pain, either constantly or off and on, for 3 months or more. By pelvic pain I mean pain below the belly button or in the female organs” (24).

Statistical analyses included Student’s t-test for comparisons of means and testing of linear regression models. Our primary outcomes were the subscales of the OABq (i.e OABq-SS and OABq-HRQL). Primary exposures measures included the SSS8, the PROMIS score, and individual diagnoses of CSS, any CSS, and increasing numbers of CSS. We used Pearson correlations to examine strength of associations between OABq-SS, OABq-HRQL, SSS8, and PROMIS pain scores. We developed separate multiple linear regression models to analyze the effects of co-morbid conditions on the OABq-SS and OABq-HRQL that included age (as a control variable) and diagnoses of individual CSS. Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (%), unless otherwise specified. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE v.14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographic and clinical information for the 116 participants is presented in Table 1. Over half (54%) stated their urge to urinate was at least partly associated with pain, pressure, or discomfort; 28.5% stated this was the main cause. Participants reported a wide range of OAB symptom bother and effects on quality of life as well as substantial somatic symptom burden as measured by the SSS8. With a mean SSS8 score of 7.7 ± 4.7 (range 0–22), 22 (19%) women reported none to minimal, 36 (32%) low, 34 (30%) medium, and 22 (19%) high to very high somatic symptom burden. The mean PROMIS Pain intensity score was 43 ± 7 (range 31 – 54). Mean OABq-SS, OABq-HRQL, SSS8, and PROMIS pain intensity scores did not differ between subjects stating their urgency was associated with pain, pressure, or discomfort, with fear of leakage, or with both (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of cohort of 116 women with OAB participating in the current study. N (%), unless otherwise specified.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (± SD) | 125 | 41.5 ± 13.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| NH White | 101 | 87 |

| NH Black | 10 | 9 |

| Other | 5 | 4 |

| Highest education | ||

| Less than high school | 1 | 1 |

| High school graduate | 6 | 5 |

| Some college or Associates degree | 29 | 25 |

| College Graduate | 46 | 40 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 34 | 29 |

| Current OAB meds | 3 | 3 |

| “Would you say this urge to urinate is mainly because of…?” | ||

| Pain, pressure, or discomfort | 33 | 28.5 |

| You are afraid you will not make it to the bathroom in time to avoid wetting | 31 | 26.7 |

| Neither | 22 | 19.0 |

| Both | 30 | 25.9 |

| Mean OABq-SS (± SD), range | 116 | 34 ± 18, 5 – 80 |

| Mean OABq-HRQL (± SD), range | 116 | 74 ± 20, 11 – 100 |

| Mean PROMIS Pain intensity score (± SD) | 114 | 43 ± 6.8 |

| Mean Somatic Symptom Score – 8 (± SD) | 114 | 7.7 ± 4.7 |

| Frequency of CSS | ||

| Low Back Pain | 48 | 38 |

| Migraine | 38 | 30 |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | 21 | 17 |

| Pelvic Pain | 16 | 13 |

| Restless Leg Syndrome | 15 | 12 |

| Temporomandibular Disorder | 13 | 10 |

| Neck pain | 12 | 10 |

| Fibromyalgia | 9 | 7 |

| Endometriosis | 6 | 5 |

| Chemical Sensitivity | 2 | 2 |

| Vulvodynia | 1 | 1 |

| Any CSS | 84 | 72 |

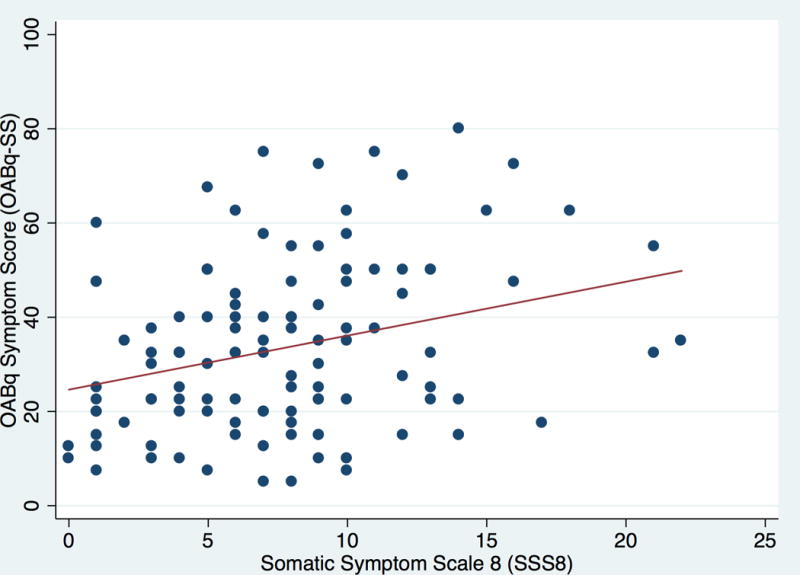

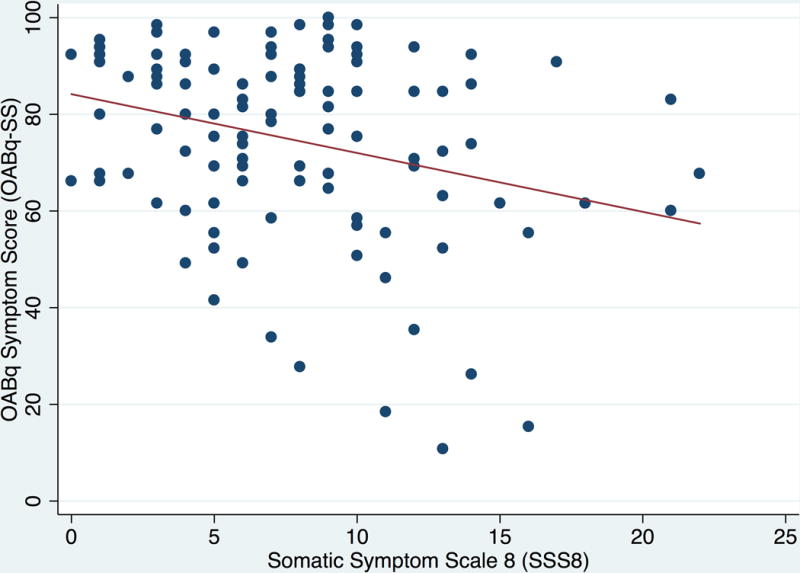

When we examined the associations between OAB symptom bother, health-related quality of life, and general somatic symptom burden, there was a significant positive correlation between OABq-SS and SSS8 (Pearson coefficient r = .296, p=.001) and a significant negative correlation between OABq-HRQL and SSS8 (Pearson coefficient r = −.292, p=.002). These findings suggest that greater OAB symptom bother and lower quality of life were both associated with greater levels of general somatic symptoms (Figure 1). A significant positive correlation was also demonstrated between PROMIS pain intensity score and OABq-SS (Pearson coefficient r = .272, p = .003), but not with OABq-HRQL.

Figure 1.

A and B. Associations between general somatic symptom bother (SSS8) and OAB symptom bother (OABq-SS; Figure 1A) and health related quality of life (OABq-HRQL; Figure 1B). There was a significant positive correlation between increasing OAB symptom bother severity and increasing somatic symptoms (Pearson coefficient r = .296, p=.001). There was a significant negative correlation between decreasing OAB-specific health-related quality of life and increasing somatic symptoms (Pearson coefficient r = −.292, p=.002).

Analyses of differences in OAB symptoms as a function of presence of individual CSS revealed significant differences only in women with fibromyalgia (compared to those without) for OAB symptom bother (Table 2). The mean OABq-SS score was 19 points higher for women with co-morbid fibromyalgia than those without. There were no differences in either the OABq-SS or OABq-HRQL for women with any CSS versus no CSS. Women with the greatest number of CSS comorbidities (3 or more CSS) reported higher OAB symptom bother and lower health-related quality of life compared to those with fewer CSS, but these trends were not statistically significant (p >.1, Table 3). However, greater number of CSS was associated with significantly greater somatic symptom burden as measured by the SSS8 (p =.003).

Table 2.

Comparison of mean OABqSS and OABqHRQL scores between women with and without individual central sensitivity syndromes (CSS).

| With CSS | Without CSS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | ||

| Low Back Pain | OABqSS | 34 | 29 – 40 | 34 | 30 – 38 |

| OABqHRQL | 74 | 68 – 80 | 73 | 68 – 77 | |

| Migraine | OABqSS | 32 | 27 – 38 | 35 | 31 – 39 |

| OABqHRQL | 77 | 71 – 83 | 72 | 67 – 76 | |

| IBS | OABqSS | 36 | 27 – 44 | 34 | 30 – 37 |

| OABqHRQL | 65 | 54 – 75 | 75 | 72 – 79 | |

| Pelvic Pain | OABqSS | 30 | 21 – 40 | 35 | 31 – 38 |

| OABqHRQL | 78 | 69 – 88 | 73 | 69 – 77 | |

| Restless Leg Syndrome | OABqSS | 38 | 30 – 46 | 34 | 30 – 37 |

| OABqHRQL | 69 | 61 – 77 | 74 | 70 – 78 | |

| TMJD | OABqSS | 31 | 20 – 43 | 34 | 31 – 38 |

| OABqHRQL | 73 | 57 – 89 | 73 | 70 – 77 | |

| Neck pain | OABqSS | 45 | 35 – 55 | 33 | 30 – 36 |

| OABqHRQL | 62 | 50 – 75 | 75 | 71 – 78 | |

| Fibromyalgia | OABqSS | 52 | 37 – 68 | 33 | 30 – 35 |

| OABqHRQL | 62 | 41 – 83 | 75 | 71 – 78 | |

| Endometriosis | OABqSS | 34 | 16 – 52 | 34 | 31 – 37 |

| OABqHRQL | 67 | 52 – 82 | 74 | 70 – 77 | |

| Any CSS | OABqSS | 34 | 30 – 38 | 34 | 27 – 41 |

| OABqHRQL | 73 | 69 – 78 | 73 | 65 – 81 | |

Significant values in bold.

Table 3.

Mean (95% confidence intervals) OAB scores across increasing numbers of central sensitivity syndromes.

| Number of CSS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | |

| Number of women (%) | 32 (28) | 44 (38) | 18 (16) | 22 (19) |

| OABq-SS | 32 (27 – 39) | 32 (27 – 37) | 33 (24 – 41) | 38 (29 – 47) |

| OABq-HRQL | 74 (66 – 81) | 77 (72 – 83) | 75 (67 – 82) | 72 (62 – 81) |

| SSS8ˆ | 6.0 (4.3 – 7.7) | 7.0 (5.6 – 8.4) | 8.7 (6.9 – 10.5) | 10.5 (8.8 – 12.1) |

Significant for trend, p=.003

After adjusting for the presence of other concurrent CSS, fibromyalgia and neck pain were both associated with higher OAB symptom bother scores (Table 4). Presence of comorbid fibromyalgia was associated with a 23-point higher mean score on the OABq-SS compared to absence of fibromyalgia. Significant effects of comorbid CSS on OAB-related quality of life were also observed. The largest effect, as for symptom bother, was for presence of comorbid fibromyalgia, which was associated with 17-point lower mean OABq-HRQL scores than in those without fibromyalgia. Women with IBS also reported significantly lower OABq-HRQL scores relative to those without these conditions, whereas those with pelvic pain had higher OABq-HRQL scores. Secondary analyses of these findings did not demonstrate differences based on whether subjects reported urgency associated with pain, pressure, or discomfort or with fear of leakage (data not shown).

Table 4.

Results of multiple linear regression models for OAB symptom bother (OABq-SS) and health-related quality of life (OABq-HRQL).

| OABq-SS | OABq-HRQL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% CI | P value | Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.1 | −.3, .3 | 0.947 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −.3, .2 | 0.745 |

| Low back pain | −1.6 | 3.7 | −8.9, 5.8 | 0.676 | 2.8 | 4.0 | −5.1, 10.7 | 0.480 |

| Migraine | −4.8 | 3.8 | −12.4, 2.8 | 0.213 | 5.4 | 4.1 | −2.7, 13.6 | 0.189 |

| IBS | 1.0 | 4.6 | −8.2, 10.2 | 0.830 | −10.4 | 5.0 | −20.3-, .5 | 0.040 |

| Pelvic pain | −8.7 | 6.2 | −21., 3.6 | 0.165 | 11.7 | 6.7 | −1.5, 24.9 | 0.083 |

| Restless Legs | 0.7 | 5.6 | −10.4, 11.9 | 0.896 | −0.8 | 6.0 | −12.8, 11.2 | 0.893 |

| TMJD | −2.1 | 5.7 | −13.5, 9.2 | 0.710 | 2.0 | 6.1 | −10.2, 14.1 | 0.749 |

| Neck pain | 13.1 | 6.2 | .8, 25.5 | 0.038 | −8.0 | 6.7 | −21.3, 5.3 | 0.234 |

| Fibromyalgia | 22.8 | 6.3 | 10.2, 35.4 | 0.001 | −16.5 | 6.8 | −30.-, 2.9 | 0.018 |

| Endometriosis | −9.9 | 9.3 | −28.4, 8.6 | 0.290 | 7.9 | 10.0 | −12., 27.8 | 0.431 |

Significant values in bold.

Discussion

In this community-based sample of women with OAB, we demonstrated that many women with OAB reported considerable somatic symptom burden. Of potential importance both clinically and mechanistically were findings that greater general bodily pain intensity and somatic symptom severity were associated with significantly greater OAB symptom bother. Elevated somatic symptom bother was further associated with lower OAB-specific health-related quality of life. To our knowledge, these observed links between greater OAB symptom bother and greater general pain intensity and somatic symptom severity have not previously been reported.

The current study also builds on a small prior literature reporting possible associations between presence of comorbid CSS and OAB symptoms and tested for these associations for the first time in a community-based sample of women. For most individual diagnoses of CSS, OAB symptom bother and health-related quality of life did not differ between women with and without co-morbid conditions. Notably, however, while only 7% of women in this OAB sample met ACR diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, those with fibromyalgia had significantly greater OAB symptom bother and, after adjusting for concomitant CSS, lower OAB health-related quality of life. Women with predominantly visceral comorbid pain conditions, such as IBS, also reported lower OAB health-related quality of life. Additionally, 35% of participants reported 2 or more co-morbid CSS. Although not statistically significant, we did note a trend (p >.1) whereby women with 3 or more concomitant CSS reported greater OAB symptom bother and lower quality of life compared to those with fewer CSS. Taken together with findings for overall pain ratings, these results appear to provide support for our hypothesis that the pathophysiology of OAB in some women may involve central sensitization mechanisms that also impact on chronic pain (8).

Our finding that a diagnosis of fibromyalgia is significantly associated with worse OAB symptoms is consistent with prior studies, but the extant literature on associations between OAB and fibromyalgia is limited. In a population survey of South Korean men and women, having fibromyalgia significantly increased the odds of concomitant OAB compared to not having fibromyalgia (OR 3.39, 95% CI 1.82 – 6.31), with increased odds associated with moderate to severe OAB (14). In a study of Brazilian women, those with fibromyalgia were more likely to report urge incontinence, urinary frequency, and detrusor overactivity on urodynamics than controls (13). To our knowledge, there are no comparable data in U.S. women. Fibromyalgia is considered to be one of the prototypical CSS, characterized by generalized, whole body somatic and pain complaints (5–7). Women with fibromyalgia frequently report multiple, concomitant CSS, reflecting a widespread alteration in afferent signal processing (6, 7). The pattern of results in the current study, in which comorbid fibromyalgia and visceral conditions were linked to OAB symptom bother and/or quality of life, support the idea that OAB may cluster with at least some well-recognized CSS due to overlapping central sensitization mechanisms.

This interpretation is consistent with prior arguments regarding the frequent co-occurrence of OAB and IBS in the same individual that have led some to hypothesize that these conditions share a common pathophysiology (12). In the Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (EpiLUTS) survey, investigators reported a higher prevalence of a self-reported diagnosis of IBS in women with urinary symptoms (ranging from 9.3 to 20.2% depending on number and types of symptoms vs. 6.3% without symptoms) (9) and in women with OAB, defined as urgency and/or urge incontinence occurring at least sometimes during the past 4 weeks (13.8% vs. 6.2%, p<.001) (10). In our study, 17% of women qualified as having IBS based on Rome III criteria, consistent with these studies. Although some data suggest women with IBS are more likely to report storage-type urinary symptoms of greater severity than those without IBS (25), our data did not demonstrate any differences in symptom bother. We did find a lower health-related quality of life for women with IBS when controlling for the presence of concomitant CSS, but it is unclear if this finding is specific for OAB or reflects toileting behavior for bowel symptoms.

There remains ongoing debate about the overlap in symptoms between women with OAB and IC/BPS and whether these conditions represent related spectrum entities with common pathophysiology of bladder hypersensitivity (1–3). Over half (54%) of the women in the current study described their urgency as associated with pain, pressure, or discomfort, with or without the fear of leakage. Other investigators of OAB and IC/BPS have reported similar findings. Clemens et al., using the same questions as the current study, found that 40% of women with OAB attributed their urgency to pain, pressure, or discomfort, as opposed to attributing it to fear of incontinence (4). Lai et al. demonstrated that women with OAB reported significantly higher levels of pain associated with bladder symptoms than controls, although not as high as those with IC/BPS (3). Our data appear to support these authors’ findings that pain symptoms in women with OAB may not be entirely attributable to IC/BPS. However, we did not identify any differences in OAB symptoms, health related quality of life, or somatic symptom burden associated with urgency related to pain, pressure or discomfort.

There are a number of limitations to the current study. We relied on participant self-report of CSS diagnoses for many of the conditions rather than validated diagnostic tools, because there are no measures for many CSS that are suitable for use in a survey study. We did use validated diagnostic and screening tools when available; however, inaccuracies of diagnoses may have biased our findings for some conditions. Next, our sample of participants was drawn from a somewhat unique non-clinical population participating in a research study recruitment pool. Details are not available for the entire population, but the sample we recruited tended to be racially homogeneous, highly-educated, and employed. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to the larger population of women with OAB. Importantly, this was not a convenience sample of women recruited from a clinic setting and thus was mostly comprised of untreated women, as reflected in very few undergoing therapy with OAB medication. We did not assess for active lifestyle or behavioral therapies or whether they had seen a provider for their OAB. In addition, while we did exclude subjects based on a diagnosis of IC/BPS, there remains the possibility that study participants did, in fact, have un-diagnosed IC/BPS instead of OAB. As a survey, the study sample is subject to selection bias, whereby women who are more bothered with their symptoms might be more likely to respond. However, we did capture a wide range of symptom bother, suggesting this may not be a significant factor. Moreover, key findings of this study derived from correlational analyses between OAB symptoms and other somatic and pain-related measures, an approach focused on rank-ordering and therefore not highly sensitive to differences in mean symptom levels. Finally, for many of the individual CSS, our sample included a small number of individuals and our study was not well-powered to analyze differences across these conditions. Larger studies with enrollment targeted to women with those conditions are needed to more thoroughly investigate possible associations.

Conclusions

In this community-based sample of women with OAB, we documented several associations with CSS, including greater OAB symptom bother and lower OAB health-related quality of life for several conditions. Women with more severe OAB symptoms also reported greater general somatic symptom burden and general pain intensity. These findings suggest that attributes of pain and co-morbidity with chronic pain and somatic conditions impact the experiences of OAB for many women. Taken further, these associations also suggest possible common mechanisms of afferent pathophysiology between OAB and CSS, which is proposed as a unifying theme for these disorders. Further study of co-morbidities in women with OAB focusing on disease mechanisms and effects on treatment outcomes are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study was supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23DK103910, and by the Vanderbilt Office of Clinical and Translational Scientist Development. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Vanderbilt University, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Homma Y. Hypersensitive bladder: towards clear taxonomy surrounding interstitial cystitis. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2013;20(8):742–3. doi: 10.1111/iju.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemens JQ. Afferent neurourology: A novel paradigm. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2010;29(Suppl 1):S29–31. doi: 10.1002/nau.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai HH, Vetter J, Jain S, Gereau RWt, Andriole GL. The overlap and distinction of self-reported symptoms between interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and overactive bladder: a questionnaire based analysis. The Journal of urology. 2014;192(6):1679–85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens JQ, Bogart LM, Liu K, Pham C, Suttorp M, Berry SH. Perceptions of “urgency” in women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome or overactive bladder. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2011;30(3):402–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states–maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):141–54. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yunus MB. Editorial Review: An Update on Central Sensitivity Syndromes and the Issues of Nosology and Psychobiology. Current rheumatology reviews. 2015;11(2):70–85. doi: 10.2174/157339711102150702112236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds WS, Dmochowski RR, Wein A, Bruehl S. Does central sensitization help explain idiopathic OAB? Nature Review Urology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.95. Accepted manuscript, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyne KS, Kaplan SA, Chapple CR, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, Bush EN, et al. Risk factors and comorbid conditions associated with lower urinary tract symptoms: EpiLUTS. BJU international. 2009;103(Suppl 3):24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyne KS, Cash B, Kopp Z, Gelhorn H, Milsom I, Berriman S, et al. The prevalence of chronic constipation and faecal incontinence among men and women with symptoms of overactive bladder. BJU international. 2011;107(2):254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malykhina AP, Wyndaele JJ, Andersson KE, De Wachter S, Dmochowski RR. Do the urinary bladder and large bowel interact, in sickness or in health? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2012;31(3):352–8. doi: 10.1002/nau.21228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly D, Chapple C. Relationship between overactive bladder (OAB) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): concurrent disorders with a common pathophysiology? BJU international. 2013;111(4):530–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2013.11019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Araujo MP, Faria AC, Takano CC, de Oliveira E, Sartori MG, Pollak DF, et al. Urodynamic study and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia and lower urinary tract symptoms. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2008;19(8):1103–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0577-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung JH, Kim SA, Choi BY, Lee HS, Lee SW, Kim YT, et al. The association between overactive bladder and fibromyalgia syndrome: a community survey. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2013;32(1):66–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliasson K, Elfving B, Nordgren B, Mattsson E. Urinary incontinence in women with low back pain. Manual therapy. 2008;13(3):206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitti VW, Kopp Z, Lin AT, Moore KH, Oefelein M, Mills IW. Can we predict which patient will fail drug treatment for overactive bladder? A think tank discussion. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2010;29(4):652–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Bavendam T, Roberts R, Elinoff V. Validation of a 3-item OAB awareness tool. International journal of clinical practice. 2011;65(2):219–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyne KS, Gelhorn H, Thompson C, Kopp ZS, Guan Z. The psychometric validation of a 1-week recall period for the OAB-q. International urogynecology journal. 2011;22(12):1555–63. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyne KS, Thompson CL, Lai JS, Sexton CC. An overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life short-form: validation of the OAB-q SF. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2015;34(3):255–63. doi: 10.1002/nau.22559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, Spangenberg L, Zenger M, Brahler E, et al. The somatic symptom scale-8 (SSS-8): a brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):399–407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003;61(3):375–82. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078940.53438.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis care & research. 2010;62(5):600–10. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langenberg PW, Wallach EE, Clauw DJ, Howard FM, Diggs CM, Wesselmann U, et al. Pelvic pain and surgeries in women before interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;202(3):286 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo YJ, Ho CH, Chen SC, Yang SS, Chiu HM, Huang KH. Lower urinary tract symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2010;17(2):175–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]