Abstract

The small leucine rich repeat proteoglycans are major components of the cornea. Lumican, keratocan, decorin, biglycan and osteoglycin are present throughout the adult corneal stroma and fibromodulin in the peripheral limbal area. In the cornea literature these proteoglycan have been reviewed as structural, collagen fibril-regulating proteins of the cornea. However, these proteoglycans are members of the leucine-rich–repeat superfamily, and share structural similarities with pathogen recognition toll-like receptors. Emerging studies are showing that these proteoglycans have a range of interactions with cell surface receptors, chemokines, growth factors and pathogen associated molecular patterns and are able to regulate host immune response, inflammation and wound healing. This review discusses what is known about their innate immune-related role directly in the cornea, and studies outside the field that find interesting links with innate immune and wound healing responses that are likely to be relevant to the ocular surface. In addition, the review discusses phenotypes of mice with targeted deletion of proteoglycan genes and genetic variants associated with human pathologies.

Introduction

The cornea, comprised of a stratified epithelium, basement membrane, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane and a single cell layered endothelium, is the outermost, avascular, refractive and protective barrier of the eye. Approximately 500 micrometers thick in humans, the stroma makes up 90% of the cornea. The stroma contains collagen fibrils of uniform diameter that are organized into orthogonal lamellae. The stroma is also rich in proteoglycans that interact with collagens to regulate fibril thickness, interfibrillar spacing and hydration, required to maintain the optical qualities of the cornea necessary for vision (Hassell and Birk, 2010; Meek and Knupp, 2015). This review discusses the role of the stromal proteoglycans in corneal inflammation and wound healing responses.

Proteoglycans are proteins, covalently conjugated to one or more glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate or heparan sulfate. The stromal proteoglycans belong to a group known as the small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans (SLRPs) carrying characteristic tandem repeats of leucine-rich repeat motifs in their core proteins. Of the ~17 known SLRPs, lumican (LUM), keratocan (KERA), mimecan/osteoglycin (OGN), decorin (DCN) and biglycan (BGN) are major components of the corneal stroma. Fibromodulin (FMOD), abundant in the sclera, is also present in the peripheral limbal region of the cornea. Therefore, the review covers these six SLRPs and their known and speculated functions in the cornea.

Historically, proteoglycans were purified by dissociative extraction, ion-exchange and molecular sieve chromatography, and sedimentation-equilibrium centrifugation. The proteoglycans were characterized by gel electrophoresis before or after cleavage of the GAG side chains to visualize the core proteins (Hassell et al., 1986; Heinegard and Sommarin, 1987). The undigested samples had high “polydispersity” appearing as smears in polyacrylamide gels while the digested “monodisperse” core proteins shifted to a faster migrating sharp band - a characteristic behavior of all proteoglycans. The earliest study of SLRPs described a low buoyant density proteoglycan in cesium chloride density centrifugations of extracts from nasal cartilage that carried chondroitin sulfate side chains (Heinegard et al., 1981) and a protein with high leucine content by amino acid analysis. Later, sequencing of cDNA clones prepared from a fibroblast cell line led to the identification of decorin (Krusius and Ruoslahti, 1986). Within a decade genes encoding biglycan (Fisher et al., 1989; Fisher et al., 1991), decorin (Santra et al., 1994; Scholzen et al., 1994), lumican (Blochberger et al., 1992a; Chakravarti and Magnuson, 1995; Chakravarti et al., 1995), fibromodulin (Antonsson et al., 1993; Sztrolovics et al., 1994), keratocan (Funderburgh et al., 1998; Tasheva et al., 1999), mimecan/osteoglycin (Funderburgh et al., 1997) and other members were sequenced and localized to specific chromosomes. An explosion of molecular biological studies and development of gene-targeted mice now present an exciting and evolving picture of the breadth of functions and molecular interactions of the core proteins (Chakravarti, 2001; Chakravarti et al., 1998; Danielson et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2003; Svensson et al., 1999; Tasheva et al., 2002; Xu et al., 1998).

Core protein structure and leucine rich repeat types –

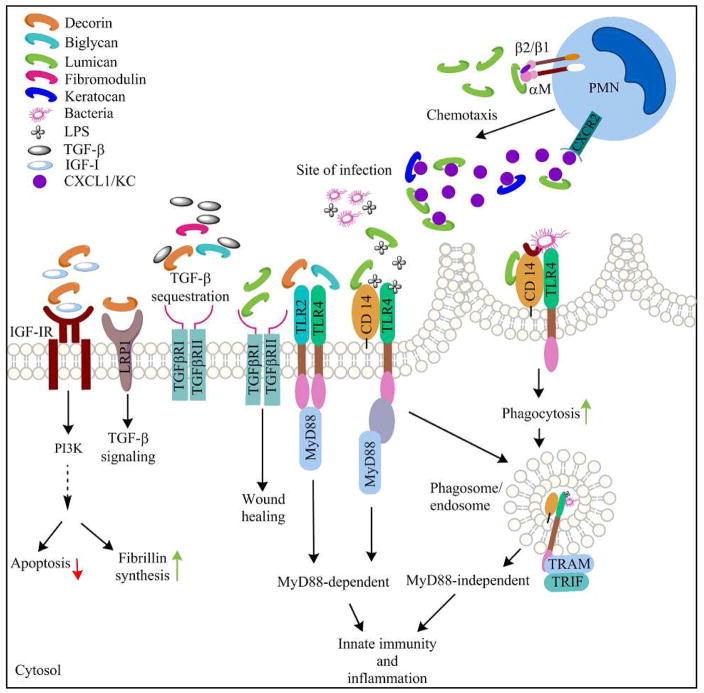

The acronym SLRP coined in the 1990s diffuses their connection to the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) superfamily of ~370 proteins which includes pathogen recognition receptors and other regulators of innate immunity. Almost the entire core proteins in SLRPs consist of tandem repeats of LRR motifs in which the minimum conserved residues are LXXLXLXXNXL with varying lengths of 20–27 amino acids (Bella et al., 2008; McEwan et al., 2006). All of the SLRPs discussed here have 12 such motifs numbered LRR 1–12. The crystal structures of decorin and biglycan core proteins have been resolved (Scott et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2004); similar to ribonuclease inhibitor (RNI), the first LRR protein to be crystallized, they have a curved solenoid shape, where each LRR motif forms a β strand and the inner concave surface forms a β sheet (Figure 1). The 4 cysteine residues at the N-terminus are disulfide bonded at alternate residues to form the N-terminal cap, while the C-terminal two-cysteine residues form disulfide bonds with each other. The difference in the spacing of the N-terminal cysteine residues is used to group the SLRPs into five classes; biglycan and decorin (Fisher et al., 1989) are Class I, lumican (Blochberger et al., 1992b), fibromodulin (Oldberg et al., 1989) and keratocan (Corpuz et al., 1996) are Class II and osteoglycin (Funderburgh et al., 1997) belongs to Class III.

Fig 1.

A crystal structure of Decorin, a Class I SLRP. Model provided by SwissModel (Kiefer et al., 2009). Decorin has a curved solenoid shape, where each LRR motif forms a β-strand and the inner concave surface forms a β-sheet (arrows).

The penultimate LRR motif, with 30–39 residues, is atypical, forms an extended loop or “ear” and found in the SLRP subfamily only. Sequence alignment studies of the “ear” motif suggest the SLRPs to have evolved from an ancestral gene by large-scale genome duplication and loss of genes (Huxley-Jones et al., 2009; Park et al., 2008). A recent study used hidden Markov modeling that uses a statistical Bayesian network-based approach to identify patterns, on all 375 LRR superfamily members to identify seven signature LRR motifs (Ng et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, the closely related SLRPs, lumican, fibromodulin and keratocan have similar distributions of 5/7 signature LRR motifs. In a hierarchical clustering of all the LRR proteins, the SLRPs form a tight cluster, and interestingly, several TLR members are placed close to the SLRPs.

Glycosaminoglycan side chains

The Class II SLRPs lumican, keratocan, fibromodulin and Class III osteoglycin, are post-translationally modified with keratan sulfate (KS) side chains covalently linked to an asparagine residue. Lumican and fibromodulin have five potential KS substitution sites, keratocan four and osteoglycin has one (Kalamajski and Oldberg, 2010). The cornea contains the type I KS form which has a long (~50) linear poly-N-acetyl lactosamine consisting of repeating units of the disaccharide[→ 3Galβ(1 → 4)GlcNAcβ(1 →], linked to an asparagine residue via a mannose containing branched oligosaccharide (Funderburgh, 2002; Quantock et al., 2010). Treatment of these SLRPs with N-glycosydase or removal of the keratan sulfate side chains with keratanase yield faster-migrating, sharper bands by gel electrophoresis. These negatively charged KS side chains regulate corneal development, wound healing, corneal hydration and transparency (Funderburgh, 2000; Quantock et al., 2010). Decorin and biglycan have one or two chondroitin/dermatan sulfate side chains, respectively, O-linked to serine residues.

Expression and distribution in the developing and adult cornea

These proteoglycans are all expressed in the human cornea. However, most of the data on expression in the developing organism is derived from studies in the mouse. Keratocan is primarily restricted to the cornea in the adult mouse, but it is more widely expressed in the developing embryo in the eye, ear, snout, tail and limb regions. The lumican transcript is detectable in the mouse embryo as early as E9.5, and in the developing cornea by E13.5 (Chakravarti, 2002; Chakravarti et al., 1998). In the adult mouse cornea, Keratocan, biglycan and decorin are present throughout, while lumican becomes more packed at the posterior stroma (Chakravarti et al., 2003). Fibromodulin is detectable throughout the developing cornea but restricted to the limbal area by P30 (Chen et al., 2010). In fungal infections of the cornea, the SLRP genes are down regulated at the early stages, whereas in mouse models of Pseudomonas keratitis lumican expression increases in the cornea within 6 hours of infection (Shao et al., 2013). Vascular endothelial cells variably express these SLRPs in response to pro-inflammatory signals. Biglycan (Moreth et al., 2010; Schaefer et al., 2005) and decorin (Koninger et al., 2006; Swirski et al., 2004) are expressed by macrophages and induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines. Lumican, on the other hand, expressed at basal levels and induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in fibroblasts, is barely detectable in macrophages and neutrophils (Lee et al., 2009; Wu and Chakravarti, 2007; Wu et al., 2007). A glycoprotein form of lumican is present in arterial blood vessel walls, and in cultured Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) (Funderburgh et al., 1991; Lee et al., 2009).

Regulation of collagen assembly and the cornea

A major function of SLRPs is their interactions with collagen fibrils and their ability to modulate collagen fibril structure, organization and corneal functions. These SLRP-collagen interactions were identified in a number of ways. Very early on electron microscopy of corneal sections stained with cupromeronic blue showed proteoglycans to occupy bands (a–e) along the collagen fibril (Scott and Bosworth, 1990); combined with immunoelectron microscopy, decorin (CSPG) was found primarily on the d and e bands (Pringle and Dodd, 1990). There are excellent reviews that discuss the collagen-proteoglycan associations in details (Chen and Birk, 2013; Kalamajski and Oldberg, 2010; Scott, 1991). In vitro collagen fibrillogenesis assays show that corneal proteoglycans and the core protein forms of lumican (and decorin) alter the kinetics of fibril formation and reduce overall turbidity, and by EM these fibrils appear thinner (Hassell et al., 1983; Rada et al., 1993). In solid phase binding assays, lumican and fibromodulin bind to immobilized mouse-tail collagen through LRR5–7. Fibromodulin shows stronger binding through another site in LRR11 (Kalamajski and Oldberg, 2007). Gene targeted mice deficient in selected SLRPs show altered collagen fibril structures in multiple connective tissue types as discussed later.

SLRPs in human eye diseases and phenotypes of gene targeted null-mice

Table 1 summarizes known and potential associations of these SLRPs with human disease, phenotypes of knockout mice and immune-related functions of the core proteins. Although recent studies are uncovering immune and inflammation regulatory functions, and changes in expression during infections and inflammation, there are no reported associations of SLRP gene variants with ocular wound healing, immune or autoimmune disease in humans.

Table 1.

Disease and knockout mouse phenotypes

| Proteoglycan | KO mice | Mouse phenotype | Disease associations | Functions in immune responses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biglycan BGN) | Bgntm1Mfy | Reduced growth rate and decreased bone mass | Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia Renal disease |

Binds TGF - β Promotes TLR2/4 response Upregulates renal CXCL13 & B cell infiltration, |

Cho,2016 Xu, 1998 Schaefer, 2005 |

| Decorin DCN) | Dcntm1Ioz | Thinning and fragility of the skin | Corneal dystrophy Renal disease |

Elevates TLR2/4 response, binds TGF-β and attenuates signal, binds LRP-1 to promote TGF-β signals | Mellgren, 2015 |

| Fibromodulin FMOD) | Fmodtm1Aol | Abnormal tail and Achilles tendons | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia Mantle cell lymphoma |

Regulates TGF-β1 bioavailability Promotes complement activation |

|

| Keratocan KERA) | Keratm1Cyl | Corneal thinning | Cornea plana congenita | Promotes neutrophil migration | |

| Lumican LUM) |

Lumtm1Chak Lumtm1Wwk |

Corneal opacity & thinning, poor wound healing, fragile skin | Myopia | Bind to LPS and CD14, promotes wound healing & neutrophil migration | Chakravarti, 1998 |

| Osteoglycin OGN) | Ogntm1Eta | Collagen fibril diameter increased in cornea and skin | Cardiac Hypertrophy & left ventricular mass | Binds TGF-β | Tasheva, 2002 |

Thus far, SLRP gene variants are associated with corneal structural anomalies and dystrophies. Two mutations in keratocan, a deleterious amino acid substitution and a premature stop codon were identified in patients with cornea plana, a flattening of the cornea that may be associated with other corneal malformations (Pellegata et al., 2000). The keratocan-null mice show thinning of the corneal stroma and a mild increase in collagen fibril diameter, while corneal transparency was unaffected (Liu et al., 2003). Lumican has been inconclusively associated with high myopia (Feng et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Park et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2006). The corneas of Lum−/− mice have large-diameter fibrils with irregular contours, and by slit lamp biomicroscopy the cornea appears cloudy, while the skin and tendon show loss of tensile strength (Chakravarti et al., 1998). The Fmod-null mice, on the other hand have unremarkable collagen architecture in the central cornea. By contrast, in the limbal area, where fibromodulin is normally present (Chen et al., 2014), the fibrils have slightly larger diameter. Mice deficient in both lumican and fibromodulin show a severe collagen structure defect (much worse than the phenotype in mice deficient in lumican alone) in the entire cornea, suggesting functional cooperation between these two SLRPS (Chakravarti et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014). The double-null mice show increased axial length reminiscent of myopia (Chakravarti et al., 2003; Song et al., 2003). A deletion on chromosome 12q21.33 encompassing KERA, LUM, DCN and EPYC (epiphycan) was reported in families with posterior amorphous corneal dystrophy (Kim et al., 2014). Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy is due to dominant negative mutations in decorin, where a truncated protein is secreted into the extracellular matrix, disrupting normal collagen architecture and corneal transparency (Bredrup et al., 2005). Gene-targeted mouse models expressing truncated decorin reflect some features of the human disease, but the phenotype is milder as the truncated protein is not secreted and thus less disruptive to collagen fibril assembly and the ECM (Chen et al., 2013; Mellgren et al., 2015). Two BGN mutations that disrupt TGF-β interactions, have been recently identified in patients with spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, characterized by spine and long bone defects and osteoarthritis (Cho et al., 2016), while the Bgn-null mice display osteoporosis-like reduced bone mass (Xu et al., 1998). The corneas of Bgn-null mice have normal collagen fibril structure suggesting a minor role in collagen fibril regulation in the cornea. The collagen fibril defect in the Bgn-Dcn double null mice is exacerbated compared to the Dcn-null mice, and biglycan levels are elevated in the cornea of the latter, suggesting some biglycan-mediated rescue of the collagen fibril phenotype (Zhang et al., 2009). There are no reported ocular pathologies associated with osteoglycin, however it is implicated in the regulation of left ventricular mass cardiac pathologies in humans (Petretto et al., 2008). Ogn-null mice have thicker collagen fibrils in the skin and cornea without an overt corneal phenotype (Tasheva et al., 2002). There are no other reported connective tissue anomalies in the Ogn-nulls, except that in a pro-hypertrophic stimulus model the cardiac phenotype was attenuated, consistent with increased osteoglycin levels in human disease (Petretto et al., 2008).

SLRPs modulate corneal wound-healing responses

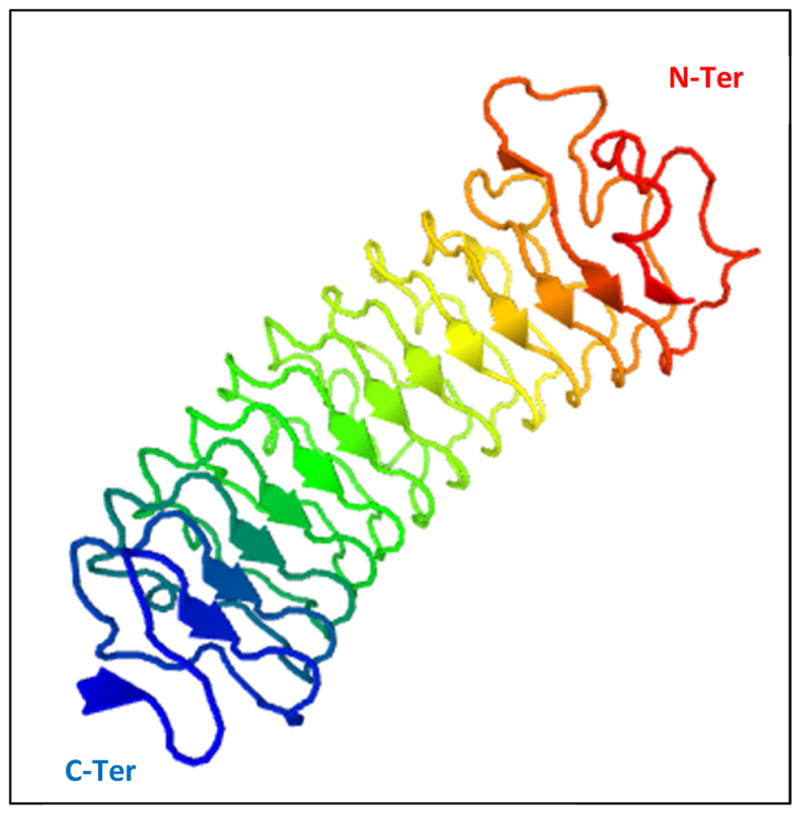

Recent studies suggest that SLRPs interact with multiple cell-signaling pathways. These interactions are likely to influence various aspects of corneal wound healing responses and resolution of infections as discussed here (Figure 2). The cornea is subject to traumas that include epithelial and stromal injuries, and clinical procedures such as epithelial debridement preceding UV crosslinking treatments of keratoconus patients, and refractive surgeries. Depending on the type of injury, wound-healing responses are initiated in the epithelium, stroma or both. Epithelial injuries disrupt normal epithelial exfoliation and differentiation, and promote apoptosis, loss of epithelial morphology and rapid migration of basal cells to close the wound (Mohan et al., 2003; Netto et al., 2005). Stromal keratocytes adjacent to an epithelial injury undergo apoptosis, keratocytes activated at the margin migrate into the de-cellularized region, bone marrow derived cells are recruited, and a provisional wound matrix is produced (Mohan et al., 2003; Netto et al., 2005). If the injuries are extensive or chronic, damaging myofibroblasts and scar tissues appear (Torricelli et al., 2016). These multistep processes are orchestrated by autocrine and paracrine growth factor, cytokine and chemokine signals (Klenkler and Sheardown, 2004; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015; Terai et al., 2011). These SLRPs are primarily mesenchymal connective tissue constituents, and thus major regulators of stromal wound healing. Thus far, lumican is the only known exception in that it is expressed by the epithelia during wound healing. Lumican-null mice show delayed closure of corneal epithelial wounds and recombinant lumican promotes epithelial cell migration via integrin β1, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and ERK1/2 activation as well as through interactions of its C-terminal domain with ALK5, the TGF-β RI receptor (Saika et al., 2000; Seomun and Joo, 2008; Vij et al., 2005; Yamanaka et al., 2013). In cancer however, lumican inhibits melanoma cell migration through integrin β1 interactions, and lumican counteracts tumor progression by a combination of MMP14-inhibition and suppression of cell proliferation (Brezillon et al., 2009; Stasiak et al., 2016; Zeltz et al., 2010).

Fig 2.

A schematic representation of functions of the SLRPs in innate immune signals and corneal wound healing.

Upon injury the corneal epithelium and the stroma produce insulin, IGF-I and IGF-II that signal via IGF-IR to phosphorylate PI3K and AKT, promote cell survival and production of ECM and cell adhesive proteins in epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes (Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015) (Musselmann et al., 2008; Vincent and Feldman, 2002). Studies of renal fibrosis and cartilage chondrocytes show induction of decorin by IGF-IR signaling; the renal fibrosis study further report that decorin interacts with IGF-IR, AKT/PKB to induce other ECM proteins such as fibrillin (Chubinskaya et al., 2007; Schaefer et al., 2007). This axis has not been investigated in the cornea, although increased expression and release of decorin from a remodeling ECM is likely to impact corneal wound healing.

TGF-β1 and TGF-β2, the major subtype in the cornea, promote epithelial cell growth, promote or inhibit stromal cell growth and migration during corneal wound healing reviewed by others (Saika, 2004; Saika et al., 2001). Under homeostatic conditions, the TGF-β isoforms promote ECM protein synthesis and restrict immune response to help maintain corneal immune privilege. In injury and infections, TGF-β signals cross talk with PDGF and integrins to promote myofibroblast differentiation and fibrosis (Jester et al., 2002; Xing and Bonanno, 2009). Decorin, biglycan and fibromodulin bind TGF-β (Brown et al., 2002; Hildebrand et al., 1994), to reduce its bioavailability and compete with the signaling receptors to attenuate signal transduction (Droguett et al., 2006; Hausser et al., 1994). Decorin also interacts with lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1) to promote TGF-β signals. In multiple myopathies, aortic aneurysms and osteogenesis imperfecta, TGF-β signal excesses are implicated (Dietz, 2010). Interestingly, decorin levels in tissues of such patients were decreased and this was mirrored in fibroblasts of mouse models as well (Dietz, 2010; Grafe et al., 2014). In keratoconus, a stromal thinning disease of the cornea, these SLRPs were reduced and in cultured stromal fibroblasts, these SLRPs and TGF-β signals were altered (Foster et al., 2014). Thus, the SLRPs may be key modulators of TGF-β signals in multiple connective tissue and ocular pathologies.

SLRPs and complement activation

The complement pathways regulate innate immunity, inflammation and clearance of bacteria and damaged host cells (Ricklin et al., 2010) – all potentially important in protecting the cornea and maintaining its transparency. Identification of a polymorphism in the complement Factor H gene in age-related macular degeneration, some ten years ago, has led to intensive studies of the complement systems in the retina (Klein et al., 2005). In the cornea, however complement functions have not been investigated significantly. Early studies demonstrated the presence of complement pathway intermediates and activities in the central and peripheral cornea (Mondino et al., 1996; Mondino and Hoffman, 1980). In rheumatoid arthritis, SLRPs present in the cartilage have been linked to complement functions. Decorin and biglycan bind to C1q at its C-terminal domain and inhibit the classical complement activation pathway (Groeneveld et al., 2005). Fibromodulin activates the classical pathway in vitro by binding to the N-terminal domain of C1q (Sjoberg et al., 2005; Sjoberg et al., 2009). Fibromodulin also binds to C4BP (Happonen et al., 2009), an inhibitor of the classical and the lectin-mediated complement activation pathway, which could have a counter-modulatory effect on complement activation. Thus, fibromodulin, strategically located in the peripheral cornea (Chen et al., 2010), where complement components are probably higher than the central cornea, may regulate complement functions in the cornea.

SLRPs regulate innate immune signals, neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis

Lumican, biglycan and, more recently decorin have been shown to interact with TLR-2 and/or −4 signaling pathways. Toll-like receptors are Type I transmembrane pathogen recognition receptors regulate a variety of host innate immune response to pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and intracellular DNA sensing receptors. The reader is directed to several excellent reviews on TLRs for in depth discussion of these pathways (Beutler, 2004; Kawai and Akira, 2010; Medzhitov, 2001) and for their role at the ocular surface (Kumar and Yu, 2006; Pearlman et al., 2008). TLR-2 recognizes a range of pathogens from lipopeptides, peptidoglycans, lipoteichoic to fungal zymosan and viral hemagglutinin protein (Kawai and Akira, 2010). TLR-4, the first such receptor to be studied recognizes bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (Beutler et al., 2001). TLR-4 response to LPS involves initial binding of LPS with LPS-binding protein (LBP), followed by its interactions with CD14, which delivers LPS to TLR-4 complexed with MD-2 a soluble protein. CD-14 is a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol-linked membrane protein that facilitates TLR-2 and TLR-4 signals (Jiang et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Triantafilou and Triantafilou, 2002), and recently identified as a co-receptor for TLR-7 and −9 as well (Baumann et al., 2010). Lumican-null mice are hypo responsive to LPS-mediated septic shock, while Lum −/− peritoneal macrophages are also hypo responsive to LPS in cell culture (Lee et al., 2009), with lower induction of TNF-α that could be rescued with exogenous recombinant lumican (Wu et al., 2007). Thus, lumican cooperates with TLR-4 and increases host response to LPS. Mechanistically, this involves weak interactions of lumican with LPS and a specific high affinity binding with CD14 involving a tyrosine-containing site near its N-terminal end (Shao et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2007). In sterile LPS wounds of the cornea, the Lum −/− mice show lower TNF-α and reduced infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages in the cornea (Vij et al., 2005). In infectious (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) bacterial keratitis, within 24 hours post infection, the Lum −/− mice show poor bacterial clearance, lower neutrophil counts (Shao et al., 2013), but overall higher inflammatory cell in late disease, elevated clinical disease score and higher TNF-α levels. Consistent with poor neutrophil infiltration in injured or infected Lum −/− corneas, in vitro chemotaxis assays also show that lumican promotes neutrophil chemotaxis towards LPS and the chemokine CXCL1, and that this is mediated through its interactions with αM (CD11b), β2 (CD18) and β1 (CD29) integrin subunits (Lee et al., 2009). Another study showed direct binding of lumican and keratocan to CXCL1 (KC) and that this may regulate a chemokine gradient important for neutrophil migration (Carlson et al., 2007). Phagocytosis, a process by which cells take up bacteria and damaged host cells for clearance is mediated by multiple processes driven by complement, Fc receptors, dectins integrins, CD14 and lectins (Underhill and Gantner, 2004). Lumican contributes to both opsonic, integrin (CD18) mediated, and non-opsonic CD14-mediated phagocytosis; in P. aeruginosa infections lumican contributes the most towards CD14-mediated bacterial phagocytosis (Shao et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2013).

Based on studies in systems other than the eye, biglycan and decorin also regulate TLR signals. Macrophages stimulated with pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, Il-6) express biglycan. Biglycan-null mice like lumican-nulls are hypresponsive to LPS and show better survival in LPS sepsis models (Schaefer et al., 2005). However, unlike lumican, biglycan alone, without added LPS, induces pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages in culture and thus is viewed as a danger associated molecular pattern. Decorin also enhances LPS response in macrophages to induce TNF-α production in a TLR-2 and −4 dependent manner (Merline et al., 2011).

Concluding remarks

The SLRPs discussed here are abundant in the cornea, sclera and other connective tissues, where they regulate collagen fibril assembly, corneal transparency and biomechanical properties. Their LRR motifs have the ability to interact with a wide range of other proteins including cell surface receptors, growth factors, ligands and microbial pathogen associated molecular patterns. While there is no concrete experimental evidence, it is tempting to suggest that collagen-matrix incorporated SLRPs are likely to be less interactive with immune signals, while their release from a remodeling matrix or de novo synthesis during injury, inflammation and infections can lead to their increased immune-modulatory functions. As the field begins to understand more about when and where these SLRPs become biologically active in host immune responses, their roles in normal healing processes and dysregulations in chronic infections and autoimmunity will become evident.

This review discusses small leucine rich repeat proteoglycans of the cornea.

The review focuses on functions of the proteoglycans in innate immune response, inflammation and wound healing of the cornea.

Functions of lumican, keratocan, fibromodulin, biglycan, decorin and osteoglycin are discussed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Hassell for his helpful comments and NEI/NIH grants (EY11654, EY 026104) to SC for funding support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antonsson P, Heinegard D, Oldberg A. Structure and deduced amino acid sequence of the human fibromodulin gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1174:204–206. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90117-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann CL, Aspalter IM, Sharif O, Pichlmair A, Bluml S, Grebien F, Bruckner M, Pasierbek P, Aumayr K, Planyavsky M, Bennett KL, Colinge J, Knapp S, Superti-Furga G. CD14 is a coreceptor of Toll-like receptors 7 and 9. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2689–2701. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella J, Hindle KL, McEwan PA, Lovell SC. The leucine-rich repeat structure. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2307–2333. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B. Inferences, questions and possibilities in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature. 2004;430:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Du X, Poltorak A. Identification of Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) as the sole conduit for LPS signal transduction: genetic and evolutionary studies. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochberger TC, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Isolation and partial characterization of lumican and decorin from adult chicken corneas. A keratan sulfate-containing isoform of decorin is developmentally regulated. J Biol Chem. 1992a;267:20613–20619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochberger TC, Vergnes JP, Hempel J, Hassell JR. cDNA to chick lumican (corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan) reveals homology to the small interstitial proteoglycan gene family and expression in muscle and intestine. J Biol Chem. 1992b;267:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredrup C, Knappskog PM, Majewski J, Rodahl E, Boman H. Congenital stromal dystrophy of the cornea caused by a mutation in the decorin gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:420–426. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezillon S, Radwanska A, Zeltz C, Malkowski A, Ploton D, Bobichon H, Perreau C, Malicka-Blaszkiewicz M, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Lumican core protein inhibits melanoma cell migration via alterations of focal adhesion complexes. Cancer Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CT, Lin P, Walsh MT, Gantz D, Nugent MA, Trinkaus-Randall V. Extraction and purification of decorin from corneal stroma retain structure and biological activity. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;25:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EC, Lin M, Liu CY, Kao WW, Perez VL, Pearlman E. Keratocan and lumican regulate neutrophil infiltration and corneal clarity in lipopolysaccharide-induced keratitis by direct interaction with CXCL1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35502–35509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705823200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S. The cornea through the eyes of knockout mice. Exp Eye Res. 2001:73. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S. Functions of lumican and fibromodulin: lessons from knockout mice. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:287–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1025348417078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Magnuson T. Localization of mouse lumican (keratan sulfate proteoglycan) to distal chromosome 10. Mamm Genome. 1995;6:367–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00364803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Magnuson T, Lass JH, Jepsen KJ, LaMantia C, Carroll H. Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly: skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1277–1286. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Paul J, Roberts L, Chervoneva I, Oldberg A, Birk DE. Ocular and scleral alterations in gene-targeted lumican-fibromodulin double-null mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2422–2432. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Stallings RL, SundarRaj N, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Primary structure of human lumican (keratan sulfate proteoglycan) and localization of the gene (LUM) to chromosome 12q21.3–q22. Genomics. 1995;27:481–488. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Birk DE. The regulatory roles of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in extracellular matrix assembly. FEBS J. 2013;280:2120–2137. doi: 10.1111/febs.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Oldberg A, Chakravarti S, Birk DE. Fibromodulin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis during peripheral corneal development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:844–854. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Sun M, Iozzo RV, Kao WW, Birk DE. Intracellularly-retained decorin lacking the C-terminal ear repeat causes ER stress: a cell-based etiological mechanism for congenital stromal corneal dystrophy. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Young MF, Chakravarti S, Birk DE. Interclass small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan interactions regulate collagen fibrillogenesis and corneal stromal assembly. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SY, Bae JS, Kim NK, Forzano F, Girisha KM, Baldo C, Faravelli F, Cho TJ, Kim D, Lee KY, Ikegawa S, Shim JS, Ko AR, Miyake N, Nishimura G, Superti-Furga A, Spranger J, Kim OH, Park WY, Jin DK. BGN Mutations in X-Linked Spondyloepimetaphyseal Dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubinskaya S, Hakimiyan A, Pacione C, Yanke A, Rappoport L, Aigner T, Rueger DC, Loeser RF. Synergistic effect of IGF-1 and OP-1 on matrix formation by normal and OA chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpuz L, Funderburgh J, Funderburgh M, Bottomley G, Prakash S, Conrad G. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of keratocan. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9759–9763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz HC. TGF-beta in the pathogenesis and prevention of disease: a matter of aneurysmic proportions. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:403–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI42014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droguett R, Cabello-Verrugio C, Riquelme C, Brandan E. Extracellular proteoglycans modify TGF-beta bio-availability attenuating its signaling during skeletal muscle differentiation. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng YF, Zhang YL, Zha Y, Huang JH, Cai JQ. Association of Lumican gene polymorphism with high myopia: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:1321–1326. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L, Termine J, Young M. Deduced protein sequence of bone small proteoglycan I (Biglycan) shows homology with proteoglycan II (decorin) and several nonconnective tissue proteins in a variety of species. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4571–4576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Heegaard AM, Vetter U, Vogel W, Just W, Termine JD, Young MF. Human biglycan gene. Putative promoter, intron-exon junctions, and chromosomal localization. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14371–14377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J, Wu WH, Scott SG, Bassi M, Mohan D, Daoud Y, Stark WJ, Jun AS, Chakravarti S. Transforming growth factor beta and insulin signal changes in stromal fibroblasts of individual keratoconus patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL. Keratan sulfate: structure, biosynthesis, and function. Glycobiology. 2000;10:951–958. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.10.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL. Keratan sulfate biosynthesis. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:187–194. doi: 10.1080/15216540214932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL, Corpuz LM, Roth MR, Funderburgh ML, Tasheva ES, Conrad GW. Mimecan, the 25-kDa corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan, is a product of the gene producing osteoglycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28089–28095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, Conrad GW. Arterial lumican. Properties of a corneal-type keratan sulfate proteoglycan from bovine aorta. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24773–24777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL, Perchellet AL, Swiergiel J, Conrad GW, Justice MJ. Keratocan (Kera), a corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan, maps to the distal end of mouse chromosome 10. Genomics. 1998;52:110–111. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafe I, Yang T, Alexander S, Homan EP, Lietman C, Jiang MM, Bertin T, Munivez E, Chen Y, Dawson B, Ishikawa Y, Weis MA, Sampath TK, Ambrose C, Eyre D, Bachinger HP, Lee B. Excessive transforming growth factor-beta signaling is a common mechanism in osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 2014;20:670–675. doi: 10.1038/nm.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld TW, Oroszlan M, Owens RT, Faber-Krol MC, Bakker AC, Arlaud GJ, McQuillan DJ, Kishore U, Daha MR, Roos A. Interactions of the extracellular matrix proteoglycans decorin and biglycan with C1q and collectins. J Immunol. 2005;175:4715–4723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happonen KE, Sjoberg AP, Morgelin M, Heinegard D, Blom AM. Complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein interacts directly with small glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. J Immunol. 2009;182:1518–1525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell J, Cintron C, Kublin C, Newsome D. Proteoglycan changes during restoration of transparency in corneal scars. Archives Biocchemistry and Biophysics. 1983;222:362–369. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell JR, Birk DE. The molecular basis of corneal transparency. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell JR, Kimura JH, Hascall VC. Proteoglycan core protein families. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:539–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser H, Groning A, Hasilik A, Schonherr E, Kresse H. Selective inactivity of TGF-beta/decorin complexes. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:243–245. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinegard D, Paulsson M, Inerot S, Carlstrom C. A novel low-molecular weight chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan isolated from cartilage. Biochem J. 1981;197:355–366. doi: 10.1042/bj1970355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinegard D, Sommarin Y. Proteoglycans: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1987;144:305–319. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)44185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen LM, Heinegard D, Twardzik DR, Border WA, Ruoslahti E. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor beta. Biochem J. 1994;302( Pt 2):527–534. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley-Jones J, Pinney JW, Archer J, Robertson DL, Boot-Handford RP. Back to basics--how the evolution of the extracellular matrix underpinned vertebrate evolution. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2008.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Huang J, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD. TGFbeta induced myofibroblast differentiation of rabbit keratocytes requires synergistic TGFbeta, PDGF and integrin signaling. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:645–657. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, Shamel L, Sovath S, Mudd S, Huber M, Kalis C, Keck S, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Beutler B. CD14 is required for MyD88-independent LPS signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:565–570. doi: 10.1038/ni1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. Fibromodulin binds collagen type I via Glu-353 and Lys-355 in leucine-rich repeat 11. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26740–26745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. The role of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in collagen fibrillogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Lee CJ, Jin MS, Lee CH, Paik SG, Lee H, Lee JO. Crystal structure of CD14 and its implications for lipopolysaccharide signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11347–11351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Frausto RF, Rosenwasser GO, Bui T, Le DJ, Stone EM, Aldave AJ. Posterior amorphous corneal dystrophy is associated with a deletion of small leucine-rich proteoglycans on chromosome 12. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenkler B, Sheardown H. Growth factors in the anterior segment: role in tissue maintenance, wound healing and ocular pathology. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koninger J, Giese NA, Bartel M, di Mola FF, Berberat PO, di Sebastiano P, Giese T, Buchler MW, Friess H. The ECM proteoglycan decorin links desmoplasia and inflammation in chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:21–27. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusius T, Ruoslahti E. Primary structure of an extracellular matrix proteoglycan core protein deduced from cloned cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7683–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Yu FS. Toll-like receptors and corneal innate immunity. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:327–337. doi: 10.2174/156652406776894572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Bowrin K, Hamad AR, Chakravarti S. Extracellular matrix lumican deposited on the surface of neutrophils promotes migration by binding to beta2 integrin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23662–23669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhai L, Zeng S, Peng Q, Wang J, Deng Y, Xie L, He Y, Li T. Lack of Association Between LUM rs3759223 Polymorphism and High Myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:707–712. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Birk DE, Hassell JR, Kane B, Kao WW. Keratocan-deficient mice display alterations in corneal structure. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubimov AV, Saghizadeh M. Progress in corneal wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;49:17–45. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan PA, Scott PG, Bishop PN, Bella J. Structural correlations in the family of small leucine-rich repeat proteins and proteoglycans. J Struct Biol. 2006;155:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Knupp C. Corneal structure and transparency. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;49:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellgren AE, Bruland O, Vedeler A, Saraste J, Schonheit J, Bredrup C, Knappskog PM, Rodahl E. Development of congenital stromal corneal dystrophy is dependent on export and extracellular deposition of truncated decorin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:2909–2915. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline R, Moreth K, Beckmann J, Nastase MV, Zeng-Brouwers J, Tralhao JG, Lemarchand P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Signaling by the matrix proteoglycan decorin controls inflammation and cancer through PDCD4 and MicroRNA-21. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan RR, Hutcheon AE, Choi R, Hong J, Lee J, Ambrosio R, Jr, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Apoptosis, necrosis, proliferation, and myofibroblast generation in the stroma following LASIK and PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondino BJ, Chou HJ, Sumner HL. Generation of complement membrane attack complex in normal human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1576–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondino BJ, Hoffman DB. Hemolytic complement activity in normal human donor corneas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:2041–2044. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040893021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreth K, Brodbeck R, Babelova A, Gretz N, Spieker T, Zeng-Brouwers J, Pfeilschifter J, Young MF, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L. The proteoglycan biglycan regulates expression of the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13 and aggravates murine lupus nephritis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4251–4272. doi: 10.1172/JCI42213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselmann K, Kane BP, Alexandrou B, Hassell JR. IGF-II is present in bovine corneal stroma and activates keratocytes to proliferate in vitro. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netto MV, Mohan RR, Ambrosio R, Jr, Hutcheon AE, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Wound healing in the cornea: a review of refractive surgery complications and new prospects for therapy. Cornea. 2005;24:509–522. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000151544.23360.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng AC, Eisenberg JM, Heath RJ, Huett A, Robinson CM, Nau GJ, Xavier RJ. Human leucine-rich repeat proteins: a genome-wide bioinformatic categorization and functional analysis in innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4631–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000093107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldberg A, Antonsson P, Lindblom K, Heinegard D. A collagen-binding 59- kd protein (fibromodulin) is structurally related to the small interstitial proteoglycans PG-S1 and PG-S2 (decorin) EMBO J. 1989;8:2601–2604. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Huxley-Jones J, Boot-Handford RP, Bishop PN, Attwood TK, Bella J. LRRCE: a leucine-rich repeat cysteine capping motif unique to the chordate lineage. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:599. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Mok J, Joo CK. Absence of an association between lumican promoter variants and high myopia in the Korean population. Ophthalmic Genet. 2013;34:43–47. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.736591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman E, Johnson A, Adhikary G, Sun Y, Chinnery HR, Fox T, Kester M, McMenamin PG. Toll-like receptors at the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2008;6:108–116. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70279-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegata N, Dieguez-Lucena J, Joensuu T, Lau S, Montgomery K, Krahe R, Kivela T, Kucherlapati R, Forsius H, Chapelle Adl. Mutations in KERA, encoding keratocan, cause cornea plana. Nat Genet. 2000;25:91–95. doi: 10.1038/75664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petretto E, Sarwar R, Grieve I, Lu H, Kumaran MK, Muckett PJ, Mangion J, Schroen B, Benson M, Punjabi PP, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ, Kiesewetter C, Tasheva ES, Corpuz LM, Webb MD, Conrad GW, Kurtz TW, Kren V, Fischer J, Hubner N, Pinto YM, Pravenec M, Aitman TJ, Cook SA. Integrated genomic approaches implicate osteoglycin (Ogn) in the regulation of left ventricular mass. Nat Genet. 2008;40:546–552. doi: 10.1038/ng.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle G, Dodd C. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of the core protein of decorin near the d and e bands of tendon collagen fibrils by use of monoclonal antibodies. J Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1990;38:1405–1411. doi: 10.1177/38.10.1698203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quantock AJ, Young RD, Akama TO. Structural and biochemical aspects of keratan sulphate in the cornea. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:891–906. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada JA, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Regulation of corneal collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro by corneal proteoglycan (lumican and decorin) core proteins. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:635–648. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S. TGF-beta signal transduction in corneal wound healing as a therapeutic target. Cornea. 2004;23:S25–30. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000136668.41000.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S, Liu CY, Azhar M, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Gendron RL, Kao CW, Kao WW. TGFbeta2 in corneal morphogenesis during mouse embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2001;240:419–432. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S, Shiraishi A, Liu CY, Funderburgh JL, Kao CW, Converse RL, Kao WW. Role of lumican in the corneal epithelium during wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2607–2612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Danielson KG, Iozzo RV. Structural and functional characterization of the human decorin gene promoter. A homopurine-homopyrimidine S1 nuclease-sensitive region is involved in transcriptional control. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:579–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Babelova A, Kiss E, Hausser HJ, Baliova M, Krzyzankova M, Marsche G, Young MF, Mihalik D, Gotte M, Malle E, Schaefer RM, Grone HJ. The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2223–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI23755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Tsalastra W, Babelova A, Baliova M, Minnerup J, Sorokin L, Grone HJ, Reinhardt DP, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM. Decorin-mediated regulation of fibrillin-1 in the kidney involves the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and Mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:301–315. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholzen T, Solursh M, Suzuki S, Reiter R, Morgan JL, Buchberg AM, Siracusa LD, Iozzo RV. The murine decorin. Complete cDNA cloning, genomic organization, chromosomal assignment, and expression during organogenesis and tissue differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28270–28281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. Proteoglycan: collagen interactions and corneal ultrastructure. Biochem Eye. 1991;19:877–881. doi: 10.1042/bst0190877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Bosworth TR. A comparative biochemical and ultrastructural study of proteoglycan-collagen interactions in corneal stroma. Functional and metabolic implications. Biochem J. 1990;270:491–497. doi: 10.1042/bj2700491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott PG, Dodd CM, Bergmann EM, Sheehan JK, Bishop PN. Crystal structure of the biglycan dimer and evidence that dimerization is essential for folding and stability of class I small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13324–13332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott PG, McEwan PA, Dodd CM, Bergmann EM, Bishop PN, Bella J. Crystal structure of the dimeric protein core of decorin, the archetypal small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15633–15638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402976101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seomun Y, Joo CK. Lumican induces human corneal epithelial cell migration and integrin expression via ERK 1/2 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Lee S, Gae-Scott S, Nakata C, Chen S, Hamad AR, Chakravarti S. Extracellular matrix lumican promotes bacterial phagocytosis, and Lum−/− mice show increased Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection severity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35860–35872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Scott SG, Nakata C, Hamad AR, Chakravarti S. Extracellular matrix protein lumican promotes clearance and resolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg A, Onnerfjord P, Morgelin M, Heinegard D, Blom AM. The extracellular matrix and inflammation: fibromodulin activates the classical pathway of complement by directly binding C1q. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32301–32308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg AP, Manderson GA, Morgelin M, Day AJ, Heinegard D, Blom AM. Short leucine-rich glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix display diverse patterns of complement interaction and activation. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Lee YG, Houston J, Petroll WM, Chakravarti S, Cavanagh HD, Jester JV. Neonatal corneal stromal development in the normal and lumican-deficient mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:548–557. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiak M, Boncela J, Perreau C, Karamanou K, Chatron-Colliet A, Proult I, Przygodzka P, Chakravarti S, Maquart FX, Kowalska MA, Wegrowski Y, Brezillon S. Lumican Inhibits SNAIL-Induced Melanoma Cell Migration Specifically by Blocking MMP-14 Activity. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Aszodi A, Reinholt FP, Fassler R, Heinegard D, Oldberg A. Fibromodulin-null mice have abnormal collagen fibrils, tissue organization, and altered lumican deposition in tendon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9636–9647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swirski FK, Gajewska BU, Robbins CS, D’Sa A, Johnson JR, Pouladi MA, Inman MD, Stampfli MR. Concomitant airway expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and decorin, a natural inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta, breaks established inhalation tolerance. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2375–2386. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztrolovics R, Chen XN, Grover J, Roughley PJ, Korenberg JR. Localization of the human fibromodulin gene (FMOD) to chromosome 1q32 and completion of the cDNA sequence. Genomics. 1994;23:715–717. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasheva ES, Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Corpuz LM, Conrad GW. Structure and sequence of the gene encoding human keratocan. DNA Seq. 1999;10:67–74. doi: 10.3109/10425179909033939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasheva ES, Koester A, Paulsen AQ, Garrett AS, Boyle DL, Davidson HJ, Song M, Fox N, Conrad GW. Mimecan/osteoglycin-deficient mice have collagen fibril abnormalities. Mol Vis. 2002;8:407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai K, Call MK, Liu H, Saika S, Liu CY, Hayashi Y, Chikama T, Zhang J, Terai N, Kao CW, Kao WW. Crosstalk between TGF-beta and MAPK signaling during corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:8208–8215. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torricelli AA, Santhanam A, Wu J, Singh V, Wilson SE. The corneal fibrosis response to epithelial-stromal injury. Exp Eye Res. 2016;142:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K. Lipopolysaccharide recognition: CD14, TLRs and the LPS-activation cluster. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:301–304. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill DM, Gantner B. Integration of Toll-like receptor and phagocytic signaling for tailored immunity. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1368–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij N, Roberts L, Joyce S, Chakravarti S. Lumican regulates corneal inflammatory responses by modulating Fas-Fas ligand signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:88–95. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent AM, Feldman EL. Control of cell survival by IGF signaling pathways. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2002;12:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IJ, Chiang TH, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, Lu SC, Hou YC, Lin LL. The association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 5′-regulatory region of the lumican gene with susceptibility to high myopia in Taiwan. Mol Vis. 2006;12:852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Chakravarti S. Differential Expression of Inflammatory and Fibrogenic Genes and Their Regulation by NF-{kappa}B Inhibition in a Mouse Model of Chronic Colitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:6988–7000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Vij N, Roberts L, Lopez-Briones S, Joyce S, Chakravarti S. A novel role of the lumican core protein in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced innate immune response. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26409–26417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing D, Bonanno JA. Effect of cAMP on TGFbeta1-induced corneal keratocyte-myofibroblast transformation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:626–633. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Bianco P, Fisher LW, Longenecker G, Smith E, Goldstein S, Bonadio J, Boskey A, Heegaard AM, Sommer B, Satomura K, Dominguez P, Zhao C, Kulkarni AB, Robey PG, Young MF. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;20:78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka O, Yuan Y, Coulson-Thomas VJ, Gesteira TF, Call MK, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Chang SH, Xie C, Liu CY, Saika S, Jester JV, Kao WW. Lumican binds ALK5 to promote epithelium wound healing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltz C, Brezillon S, Kapyla J, Eble JA, Bobichon H, Terryn C, Perreau C, Franz CM, Heino J, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Lumican inhibits cell migration through alpha2beta1 integrin. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2922–2931. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Chen S, Goldoni S, Calder BW, Simpson HC, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Young MF, Iozzo RV, Birk DE. Genetic evidence for the coordinated regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis in the cornea by decorin and biglycan. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8888–8897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806590200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]