Abstract

Diabetic skin ulcers represent a challenging clinical problem with mechanisms not fully understood. In this study, we investigated the role and mechanism for the primary unfolded protein response (UPR) transducer inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α) in diabetic wound healing. Bone marrow–derived progenitor cells (BMPCs) were isolated from adult male type 2 diabetic and their littermate control mice. In diabetic BMPCs, IRE1α protein expression and phosphorylation were repressed. The impaired diabetic BMPC angiogenic function was rescued by adenovirus-mediated expression of IRE1α but not by the RNase-inactive IRE1α or the activated X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), the canonical IRE1α target. In fact, IRE1α RNase processes a subset of microRNAs (miRs), including miR-466 and miR-200 families, through which IRE1α plays an important role in maintaining BMPC function under the diabetic condition. IRE1α attenuated maturation of miR-466 and miR-200 family members at precursor miR levels through the regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD) independent of XBP1. IRE1α deficiency in diabetes resulted in a burst of functional miRs from miR-466 and miR-200 families, which directly target and repress the mRNA encoding the angiogenic factor angiopoietin 1 (ANGPT1), leading to decreased ANGPT1 expression and disrupted angiogenesis. Importantly, cell therapies using IRE1α-expressing BMPCs or direct IRE1α gene transfer significantly accelerated cutaneous wound healing in diabetic mice through facilitating angiogenesis. In conclusion, our studies revealed a novel mechanistic basis for rescuing angiogenesis and tissue repair in diabetic wound treatments.

Introduction

Diabetic skin ulcers represent a challenging clinical problem that often results in amputation (1). Neovascularization is one of the rate-limiting steps of wound healing, but it is found aberrant in wound beds in patients with diabetes with unclear mechanisms (2). Bone marrow–derived progenitor cells (BMPCs) are an important endogenous repair reservoir for neovascularization (3). It is believed that therapies of stem/progenitor cells targeting angiogenesis are hopeful solutions for refractory tissue repair. However, the dysfunction of patient-derived progenitor cells has been implicated in diabetes, which represents a major obstacle to the eventual success of autologous cell therapies in the clinic (4,5).

Metabolic stress associated with diabetes, for example, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and inflammatory cytokines (6,7), imposes cellular stress on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and may cause accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen. These conditions can trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), leading to activation of three major ER transmembrane sensors, including inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (8). Among others, IRE1α is a primary UPR transducer that, when activated by autophosphorylation, functions as an RNase and executes an unconventional splicing of the mRNA encoding a potent transcription factor X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), which activates expression of the genes primarily involved in the UPR signaling. In addition to processing the XBP1 mRNA, IRE1α can process select mRNAs or microRNAs (miRs) and subsequently lead to their degradation, a process known as regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD) (9–11). Upon activation of the RIDD pathway, IRE1α recognizes unique G/C sites within the stem-loop structures of select pre-miRs and initiates unconventional cleavage of the substrates. This action counteracts the cleavage and processing by the RNase Dicer, causing the pre-miRs to be degraded. Recent research suggested that IRE1α-mediated cleavage of XBP1 and RIDD of mRNAs or miRs are separable activities that are associated with distinct IRE1α conformational changes and affinities to the substrates (12). A unique role has been speculated for IRE1α in diabetes-related complications because of the observation that IRE1α activities are attenuated during persistent ER stress (13,14). However, the exact downstream targets of IRE1α and the mechanisms of IRE1α-mediated UPR in diabetes-associated wound healing disorders are poorly characterized.

miRs are small noncoding RNAs that act as key posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression by base pairing to the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of their target mRNAs, thereby mediating mRNA translational repression or cleavage (15). miRs have been shown to be involved in a wide range of biological processes with highly tissue-specific expression and distinct temporal expression patterns (15). Our previous reports demonstrate that miRs are important gene regulators in angiogenesis mediated by BMPCs in type 2 diabetes (16,17). Whereas most of the current research efforts are focused on identifying the downstream targets of miRs, the upstream mechanisms through which miRs are regulated remain largely unknown. It was not until recently that the importance of miRs in ER stress–induced pathogenesis has been recognized (18,19). However, it is unclear whether IRE1α plays a role in regulating miR expression in type 2 diabetes.

In this study, we reported an important biological function of IRE1α beyond its canonical role in mediating ER stress response in diabetes. Attenuation of IRE1α RNase activity resulted in an increase of a subset of miRs in diabetes, leading to impaired BMPC angiogenic functions, which cannot be reversed by restoring IRE1α’s canonical downstream target XBP1. We further uncovered that the IRE1α-mediated miR repression occurred at the pre-miR level and led to increased functional miRs that exerted the translational block on expression of the proangiogenic factor angiopoietin 1 (ANGPT1). The findings from this study not only advance our understanding of the cause of impaired angiogenesis in diabetes but also provide a novel therapeutic strategy for diabetic wound healing by enhancing IRE1α activity.

Research Design and Methods

Animals

Male type 2 diabetic mice (BKS.Cg-m+/+ Leprdb/J, db/db, age 10–12 weeks, plasma glucose 362.23 ± 41.12 mg/dL) and their age- and sex-matched nondiabetic healthy littermates (BKS.Cg-m−/− Lepdb/− lean, db/+, plasma glucose 160.77 ± 22.25 mg/dL) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). IRE1αflox/flox (C57BL/6 background) mice were generated as we described previously (20). All animal procedures were performed according to Wayne State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

BMPC In Vitro Culture and Adenovirus Infection

In vitro expansion of BMPCs was performed as described in our previous reports (17,21). Bone marrow mononuclear cells from the tibias and femurs of mice were plated on a culture flask coated with rat plasma vitronectin (Sigma-Aldrich) and maintained in endothelial growth media (EGM-2; Lonza) in 37°C, 5% CO2. For in vitro and in vivo experiments, we used the first passage cells that were cultured for 7 days and ∼80% confluent. The following characterization tests have been performed: 1) cell morphology; 2) Ulex-lectin binding and Dil-ac-LDL uptake fluorescent staining; 3) flow cytometry for cell surface markers Sca-1, CD34, Flk-1, Sca-1/Flk-1, VE-cadherin (CD144), CD11b, and CD45; and 4) Western blot analyses for typical endothelial functional protein expressions including VE-cadherin, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). To generate IRE1α−/− BMPCs, BMPCs from IRE1αflox/flox mice were infected with adenovirus (Ad)-Cre in order to delete the floxed Ire1α exons as we described previously (20). Adenoviral vectors for expression of flag-tagged human IRE1α (Ad-IRE1α) were provided by Dr. Yong Liu (Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai, China). Adenovirus expressing spliced XBP1 was provided by Dr. Umut Ozcan (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) (22). Adenovirus expressing human ANGPT1 and β-Gal were purchased from Vector Biolabs. For transfection of cells with adenovirus, cells were seeded in six-well plates. After 24 h, cells were transfected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-spliced XBP1 (XBP1s), or Ad-GFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 500 for 48 h as described previously (20).

Transfection of Pre-miR–Expressing Plasmids, Small Interfering RNA, and miR Mimic

Plasmids expressing pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-466 were constructed by inserting human pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-466 sequence into pCMV-miR vector between the SgfI and MluI site (Origene). The empty plasmid served as control. BMPCs were transfected with either 100 ng of the pre-miR–expressing plasmid or the empty plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Cells were collected simultaneously at 24 h after transfection for further analyses. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes or miR mimics were transfected into BMPCs with DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In each experiment, nonrelated scramble oligo was used as a negative control. After 60 h, the cells were harvested for the experiments.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analyses

Total RNA from BMPCs was isolated by miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). For mRNA expression analysis, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using miR primers synthesized by Exiqon. Amplification and detection of specific miR products were performed with the ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System, using U6 as an internal control. The Ct value was normalized by subtracting the U6 Ct value, which gave the ΔCt value. The relative expression levels of each target between groups were then calculated using the following equation: relative gene expression = 2−(ΔCt_treatments − ΔCt_controls).

Western Blot Analyses and Detection of IRE1α Phosphorylation by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE

Total cell lysates were prepared from cultured BMPCs. Denatured proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a 0.45-mm polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (GE Healthcare). Levels of β-actin were determined as loading controls. For the detection of phosphorylated IRE1α, 30 μg of cell lysates were loaded in 5% Phos-tag SDS-PAGE (Wako Chemicals) according to the manufacturer's instructions (23). Tunicamycin-treated liver lysate was used as positive control. The membrane was incubated with the primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Membrane-bound antibodies were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (GE Healthcare). The signal intensities were determined by Quantity One 4.4.0 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

BMPC Functional Assays

In tube formation assay, BMPCs in EBM-2 were plated in a 48-well cell culture plate (5 × 104 cells per well) precoated with 150 μL of growth factor-reduced Matrigel-Matrix (BD Biosciences), as we described previously (17). The migration assay was performed using in vitro scratch assay as described previously (17). Cell proliferation was evaluated using CellTiter 96 AQueous one solution cell proliferation assay kit (Promega).

miR Array Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from db/db BMPCs and db/+ BMPCs and subjected to mouse genome-wide miR microarray analysis using µParaflo Biochip Technology (LC Sciences) based on the latest version of the miRBase database (Sanger miRBase version 21, released 21 July 2014). The array covered all the 1,915 mature sequences of mouse miRs in the miR library. The detailed information of the microarray analysis can be found at the GEO repository (access number GSE72616).

In Vitro IRE1α-Mediated Pre-miR Cleavage Assay

In vitro cleavage of pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 by bioactive, recombinant IRE1α protein was performed as described previously with modifications (11). In brief, plasmids carrying either human pre-miR-200 sequence or human pre-miR-34 sequence (both from Origene) were used as template for PCR amplification of the linearized DNAs containing T7 promoter region and pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 sequences. The DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Promega) was used to recover ultrapure DNA from the PCR products. Transcription of large-scale RNAs of pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 was performed using the T7 RiboMax Express RNA Production System (Promega). In vitro–transcribed RNA (1 μg) was incubated with or without 1 μg bioactive recombinant human IRE1α protein (SignalChem) in a kinase reaction buffer provided by SignalChem. The cleavage reactions were initiated by adding ATP (2 mmol/L final concentration). Reaction without ATP was used as a control for each sample. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reaction products were resolved on 1.2% denaturing agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Luciferase 3′-UTR Reporter Assays

The miR-target luciferase reporter assay was performed as previously described (24). Synthetic oligonucleotides of human ANGPT1 mRNA 3′-UTR was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector system (SwitchGear). HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with 100 ng ANGPT1 3′- reporter and 0.1 nmol miR mimics (Exiqon) or 100 ng pre-miR plasmids. After 48 h, luciferase activity was measured, and the relative reporter activity was normalized to that of scramble oligo cotransfection. A reduced firefly luciferase expression indicates the direct binding of miRs to the cloned target sequence.

BMPC Cell Therapy and Gene Therapy for Wound Healing In Vivo

Wounds were created on the dorsal skin of the mouse as previously described (17). Full-thickness skins were removed using a 6-mm punch biopsy without hurting the underlying muscle. For BMPC therapy, immediately after punch, 1 × 106 BMPCs with different gene manipulation in 40 µL PBS were topically placed onto the wound area. The grouping was as follows: 1) db/+ wound with PBS, 2) db/db wound with PBS, 3) db/db wound with db/+ BMPCs infected with Ad-GFP, 4) db/db wound with db/db BMPCs infected with Ad-GFP, and 5) db/db wound with db/db BMPCs transfected with Ad-IRE1α. For IRE1α gene transfer, 108 particle forming units (pfu) of Ad-IRE1α or Ad-GFP was preloaded in 40 μL PBS at 4°C. The adenovirus suspension was injected onto the wound edge in the panniculus carnosus layer immediately after wounding, using a Hamilton syringe and 301/2 gauge needle as described previously (25). The grouping was as following: 1) db/+ wound with Ad-GFP, 2) db/db wound with Ad-GFP, and 3) db/db wound with Ad-IRE1α. Wounds were covered with transparent oxygen-permeable wound dressing (Bioclusive; Johnson & Johnson). The dressings were changed every other day. Wound closure rates were measured by tracing the wound area onto acetate paper. The tracings were digitized, and the areas were calculated with a computerized algorithm and converted to percent wound closure (ImageJ). Wound closure rates were calculated as percentage closed (y%) = [(area on day0 − open area on dayx)/area on day0] × 100, as we described previously (17). On day 6 after wounding, wounds and the adjacent skin were collected for CD31 immunochemistry staining.

Statistics

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences between the 2 two groups was determined with Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. When more than two treatment groups were compared, one-way ANOVA followed by least significant difference post hoc testing was used (26). For the in vivo wound closure data, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing was used to compare both differences between treatments and time courses. In all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

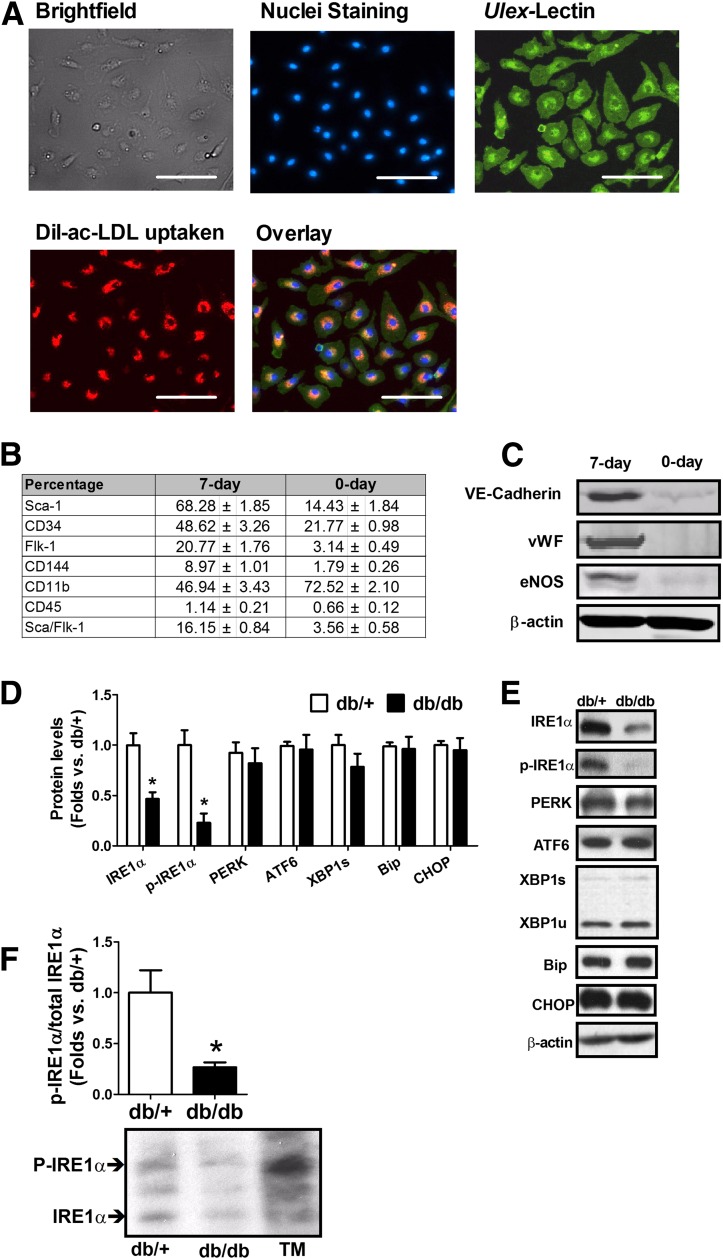

Reduced IRE1α Activity in Diabetic BMPCs Is Associated With Impaired BMPC Functions

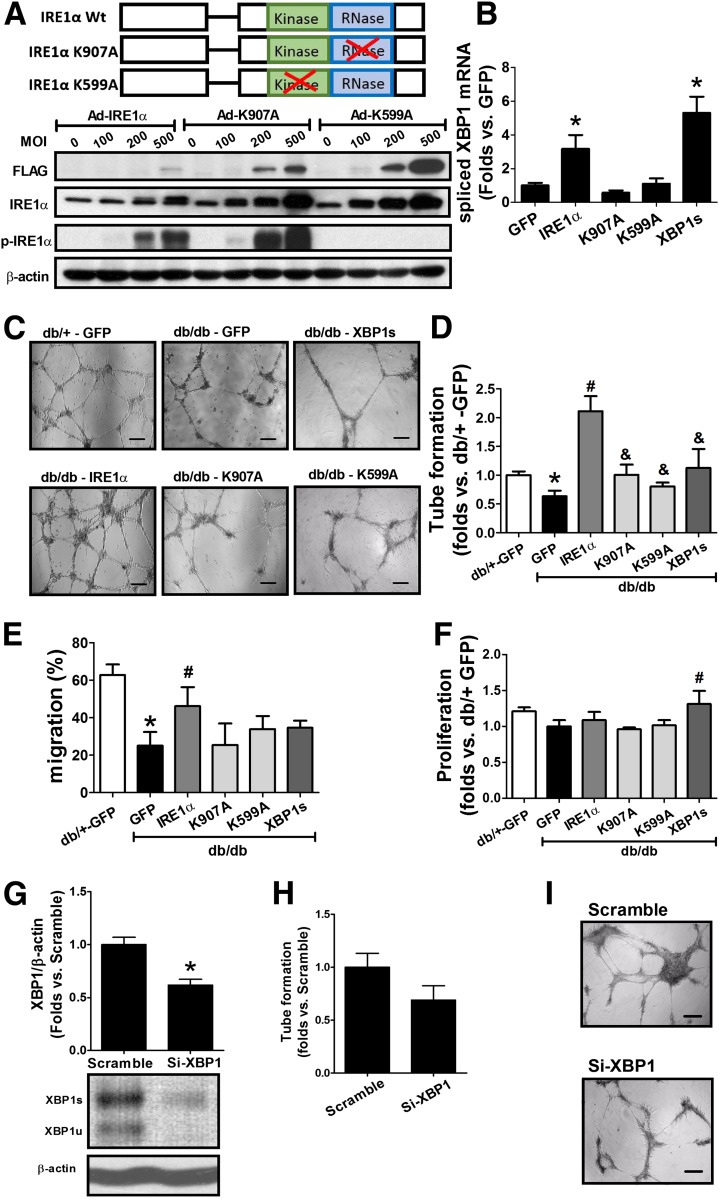

Bone marrow mononuclear cells were cultured in vitro for 7 days and were characterized as endothelial progenitor cell–enriched population (17,27). The BMPCs we cultured possessed spindle-shaped and cobblestone-like appearances, as well as Ulex-lectin binding and Dil-ac-LDL uptake double-positive phenotype (Fig. 1A). These are typical characteristics of endothelial lineage. Moreover, these cells displayed increased percentages of Sca-1, CD34, Flk-1, VE-cadherin (CD144), and Sca-1/Flk-1 double staining but decreased percentage of CD11b and unchanged CD45 (Fig. 1B). Western blot analyses indicated that these cells expressed typical functional proteins produced by endothelial cells, such as VE-cadherin, vWF, and eNOS (Fig. 1C). These data confirmed that the cells used in this study were an endothelial progenitor cell–enriched population. To evaluate the involvement of UPR in diabetic BMPCs, we examined the activity of the primary UPR transducer IRE1α in BMPCs isolated from db/db and db/+ mice. Western blot analyses revealed that the levels of IRE1α total protein and its phosphorylated form (p-IRE1αser-724) were significantly decreased in db/db BMPCs compared with that in the control db/+ BMPCs (Fig. 1D and E). The reduced levels of the phosphorylated IRE1α in db/db BMPCs were further confirmed by a Phos-tag acrylamide gel that can separate phosphorylated protein from unphosphorylated (Fig. 1F). In comparison, the levels of the other ER stress sensors and mediators, including PERK and ATF6, the chaperone protein BiP (Bip/Grp78), and the ER stress–induced proapoptotic factor CHOP, in db/db BMPCs were comparable to those in the db/+ BMPCs (Fig. 1D and E). We also detected major transcripts in canonical UPR pathways using real-time PCRs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our data suggested that that the canonical UPR pathways in db/db type 2 diabetic BMPCs were not activated. The deficiency in IRE1α RNase activity in diabetes does not alter the UPR signaling mediated through XBP1. To test whether IRE1α deficiency leads to BMPC dysfunction, adenoviral vectors expressing flag-tagged full-length human IRE1α protein (Ad-IRE1α), its RNase mutant form (Ad-K907A), or its kinase mutant form (Ad-K599A) were used to manipulate IRE1α RNase activity (20) (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the adenovirus expressing the activated form of XBP1 (XBP1s) was used to evaluate the effect of the canonical IRE1α/XBP1 axis in BMPC function. IRE1α RNase activity, as indicated by spliced XBP1 mRNA levels, was significantly increased in BMPCs upon the infection of Ad-IRE1α, but not by Ad-K907A or Ad-K599A (Fig. 2B). Importantly, IRE1α overexpression increased the formation of vessel-like tube networks (Fig. 2C and D) and augmented BMPC migration (Fig. 2E) without affecting cell proliferation (Fig. 2F). In contrast, Ad-K907A or Ad-K599A did not induce any of these changes (Fig. 2C–F), suggesting that IRE1α was critical for BMPC angiogenesis and that the defect in IRE1α RNase activity contributed to BMPC dysfunction in diabetes. On the other hand, overexpression of the activated form of XBP1 modestly improved cell proliferation (Fig. 2F) with no effect on tube formation or migration (Fig. 2C–E). This evidence suggests that IRE1α regulates BMPC function independent of activating XBP1. In db/+ BMPCs, when XBP1 expression was knocked down by siRNA (Fig. 2G), the tube formation of BMPCs was only slightly impaired (Fig. 2H and I).

Figure 1.

Deficient IRE1α activity in BMPCs in diabetes. BMPCs from type 2 diabetic db/db mice and the healthy control db/+ mice were cultured in vitro for 7 days. A: Fluorescent immunocytochemical staining of Ulex-lectin binding and Dil-ac-LDL. B: Flow cytometry analysis of Sca-1, CD34, Flk-1, VE-cadherin (CD144), and Sca-1/Flk-1 cell surface markers of BMPCs cultured for 7 days. Bar = 100 μm. C: Western blot analysis of protein levels of VE-cadherin, vWF, and eNOS in BMPCs cultured for 7 days. D: ER stress response–related protein expressions in db/db vs. db/+ BMPCs. n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+. E: Representative protein bands in db/+ and db/db BMPCs, revealed by Western blot analysis. F: Phosphorylated IRE1α (P-IRE1α) and unphosphorylated IRE1α in db/db and db/+ BMPCs separated in Phos-tag gel. n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+. Representative bands were shown beneath bar graph. Tunicamycin (TM)-treated liver tissue lysate served as a positive control for IRE1α phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Augmentation of IRE1α RNase activity boosts BMPC function in diabetes. BMPCs were isolated from individual mice and transfected with flag-tagged Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, Ad-K599A, or Ad-XBP1s, using adenovirus carrying GFP as controls. Flag-tagged protein and total IRE1α protein expression were determined by Western blot analysis. The XBP1s mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. A: Flag-tagged IRE1α and total IRE1α protein expression in db/db BMPCs after infection with flag-tagged Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, or Ad-K599A at 0, 100, 200, 500 MOI for 48 h. B: qRT-PCR analysis of XBP1 mRNA splicing in BMPCs infected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, Ad-K599A, or Ad-XBP1s. n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-GFP. C: Representative pictures showing tube formation of db/db BMPCs transfected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, Ad-K599A, Ad-XBP1s, or Ad-GFP at 500 MOI for 48 h, respectively. db/+ BMPCs transfected with Ad-GFP served as normal controls. Bar = 500 μm. D: Bar graph of tube formation quantification. n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+ + Ad-GFP; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-GFP; &P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-IRE1α. E: Migration of db/db BMPCs transfected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, Ad-XBP1s, or Ad-GFP as evaluated by in vitro wound scratch assay. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+ + Ad-GFP; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-GFP. F: Proliferation of db/db BMPCs infected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-K907A, Ad-XBP1s, or Ad-GFP as evaluated by CellTiter 96 AQueous Cell Proliferation Assay. n = 5 per group. #P < 0.05 vs. db/db GFP. G: Western blot analysis of XBP1 protein in db/+ BMPCs transfected with XBP1 siRNA (Si-XBP1) or scramble oligo. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. scramble. H: Tube formation in db/+ BMPCs infected with XBP1 siRNA or scramble oligo. n = 5 mice per group. I: Representative pictures of tube formation in db/+ BMPCs transfected with XBP1 siRNA or scramble oligo. Bar = 500 μm. Wt, wild type.

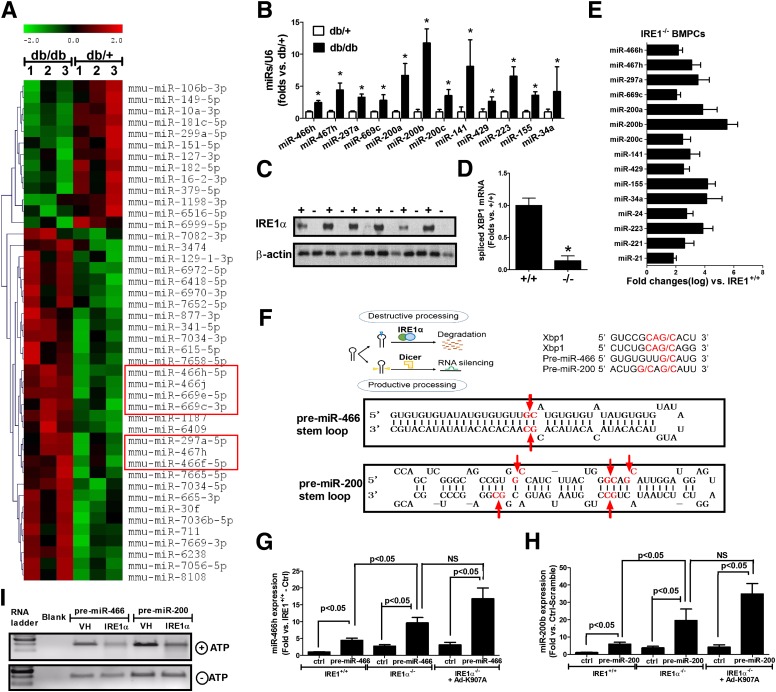

IRE1α Deletion Results in the Elevation of a Subset of miRs

To gain mechanistic insights into the role of IRE1α in the regulation of miRs in diabetic BMPCs, we did a miR microarray in db/db and db/+ BMPCs and identified a subset of miRs that were upregulated in diabetes (db/db). The miR microarray analysis revealed that among 44 significantly altered miRs in db/db BMPCs, 31 of them were upregulated, including the miR-466 family members (Fig. 3A, framed in red). In addition, qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that the elevation of miR-466 family members and many other miRs that have been implicated in oxidative stress and inflammatory response in diabetes (28), including miR-200 family members (miR-200a/b/c, miR-141, and miR-429), miR-223, miR-155, and miR-34a, in diabetic BMPCs (Fig. 3B). IRE1α−/− BMPCs were generated by infecting IRE1αflox/flox BMPCs with adenovirus expressing CRE recombinase (Fig. 3C). qRT-PCR analyses indicated that deletion of IRE1α led to a decrease in spliced XBP1 mRNA but significant increases of many similar miRs that were elevated in diabetic BMPCs, including the miR-466 family, the miR-200 family, miR-155, miR-34a, and miR-223 (Fig. 3D and E). Notably, the miR-466 family has one mature miR member, miR-466 in human, and several mature miR members in mouse, including miR-466s, miR-467s, miR-669s, and miR-297s. The miR-200 family has five mature miR members in both human and mouse, including miR-200a/b/c, miR-141, and miR-429. Examination of the pre-miR sequence of these miRs revealed that they possess G/C splicing sites within the stem loop of the secondary structures, matching the defined cleavage motif sequence of IRE1 RNase activity (29) (Fig. 3F). In fact, expression of pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 in IRE1α−/− BMPCs yielded much higher levels of mature miRs than that in the control BMPCs, compared with that in IRE1α+/+ BMPCs (Fig. 3G and H). Expression of pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 in the IRE1α−/− BMPCs infected with Ad-K907A (RNase mutant form of IRE1α) still yielded higher levels of mature miRs, suggesting that IRE1α RNase activity is required to suppress mature miR-466 and miR-200. Furthermore, we performed in vitro IRE1α-mediated RNA cleavage assay by incubating pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 with bioactive recombinant human IRE1α protein. The in vitro cleavage assay indicated a direct splicing activity of IRE1α on pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200, as pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 incubated with the recombinant IRE1α protein were partially degraded (Fig. 3I). Together, this evidence supports that IRE1α suppresses production of mature miR-466 and miR-200 family members by targeting their pre-miRs through the RIDD pathway.

Figure 3.

IRE1α deletion results in the elevation of a subset of miRs. Total RNA was extracted from db/db and db/+ BMPCs for miR microarray analysis. A: Heat map of miR microarray analysis in db/+ and db/db BMPCs. n = 3 per group. B: qRT-PCR analysis of mature miRs of miR-466 and miR-200 families as well as miR-223, miR-155, and miR-34a in db/+ and db/db BMPCs. n = 7 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+. IRE1α−/− BMPCs were generated by infecting IRE1αflox/flox BMPCs with Ad-CMV-Cre (100 MOI, Ad-β-Gal infection as control IRE1+/+ BMPCs). IRE1α protein expression was determined by Western blot analyses. C: IRE1α protein expression in IRE1+/+ and IRE1−/− BMPCs. n = 6 per group. D: qRT-PCR analysis of XBP1 mRNA splicing in IRE1α−/− and IRE1α+/+ BMPCs. n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. IRE1α+/+ BMPCs. E: qRT-PCR analysis of mature miRs in IRE1−/− and IRE1+/+ BMPCs. n = 6 per group. The elevation of all the miRs listed in this panel was statistically significant compared to IRE1α+/+ BMPCs (P < 0.05). F: Upper left illustration of IRE1α-mediated miR decay by destroying pre-miR stem-loop structure. Upper right sequence motif and stem-loop structure for the IRE1α cleavage sites within human XBP1 mRNA, pre-miR-466, and pre-miR-200. Lower pictures show the predicted miR secondary structures for miR-466 and miR-200 with their potential IRE1α cleavage sites (G/C sites marked with red arrows). G: Mature miR expression after pre-miR-466 transfection in either IRE1α+/+ BMPCs, IRE1−/− BMPCs, or IRE1α−/− BMPCs infected with Ad-K907A. Plasmid expressing pre-miR-466 or empty plasmid was transfected into either IRE1α−/− or IRE1α+/+ BMPCs via TurboFECT at the concentration of 100 ng/106 cells. miR-466h was detected using real-time PCRs. n = 6 per group. H: Mature miR expression after pre-miR-466 transfection in IRE1α −/− BMPCs. Plasmid carrying pre-miR-200 or empty plasmid was transfected into either IRE1α +/+ BMPCs, IRE1α −/− BMPCs, or IRE1α −/− BMPCs infected with Ad-K907A, via TurboFECT at the concentration of 100 ng/106 cells. Levels of miR-200b were analyzed using qRT-PCR. n = 6 per group. I: In vitro IRE1α-mediated pre-miR cleavage assay. In vitro–transcribed pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-466 RNA was incubated with or without recombinant IRE1α protein in the presence or absence of ATP in the reaction buffer. The cleavage reaction products were resolved on an agarose gel. The reaction without ATP initiation serves as a control for each sample. VH, vehicle buffer that did not contain IRE1α protein.

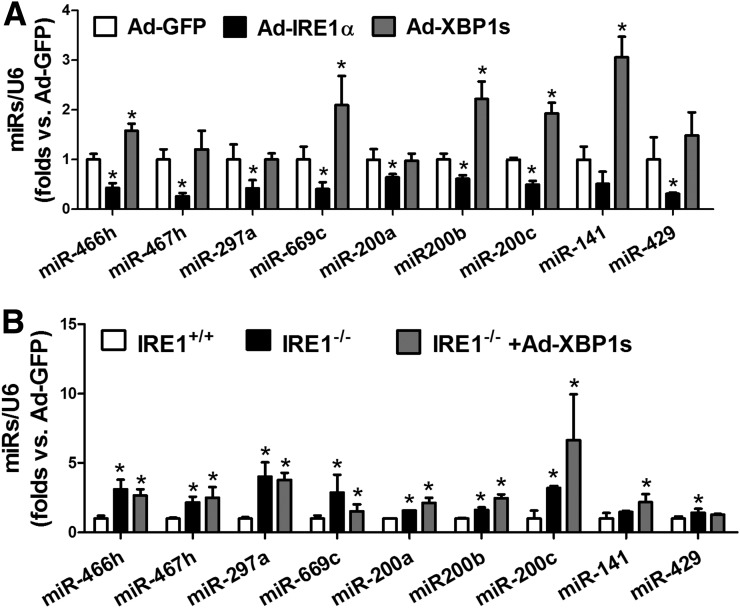

IRE1α-Mediated Suppression of miR Expression Is Independent of XBP1

To verify whether the repression of miR expression by IRE1α is associated with activation of XBP1, exogenous IRE1α or the active form of XBP1 was expressed in db/db BMPCs using an adenoviral-based overexpression system. Overexpression of IRE1α significantly repressed the levels of miR-466 and miR-200 family members in db/db BMPCs, whereas expression of the activated XBP1 failed to do so (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we overexpressed the active form of XBP1 in IRE1α−/− BMPCs to test whether XBP1 can reverse the expressions of miR-466 and miR-200 family miRs induced by IRE1α deletion. As shown in Fig. 4B, overexpression of the activated XBP1 did not lower the high expression levels of miR-466 or miR-200 in IRE1α−/− BMPCs, suggesting that IRE1α-mediated miR repression is independent of the IRE1α-mediated canonical signaling pathway through activating XBP1.

Figure 4.

IRE1α-induced suppression on miR expression is independent of XBP1. BMPCs were isolated from db/db mice and transfected with adenovirus carrying IRE1α, XBP1s, or GFP at 500 MOI for 48 h. qRT-PCR was used to determine miR expressions. A: Levels of miR-466 and miR-200 family members in db/db BMPCs infected with adenovirus carrying IRE1α, XBP1s, or GFP. U6 serves as internal control. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-GFP. BMPCs were isolated from individual IRE1αfl/fl mice and transfected with Ad-CMV-Cre to delete IRE1α protein expression; IRE1αfl/fl BMPCs transfected with Ad-GFP served as IRE1α+/+ control. IRE1α−/− BMPCs were then transfected with Ad-XBP1s or Ad-GFP at 500 MOI for 48 h. B: Levels of miR-466 and miR-200 family members in IRE1α−/− BMPCs infected with adenovirus carrying either XBP1s or GFP. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. IRE1α+/+.

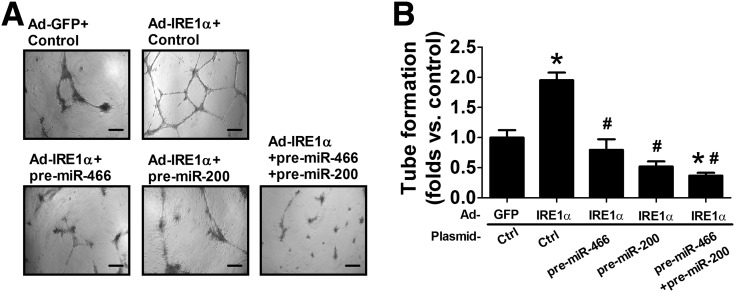

IRE1α Promotes BMPC Tube Formation by Repressing miR-466 and miR-200

To determine the functional involvement of IRE1α-mediated suppression of miR-466 and miR-200, pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 was transferred into IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs to test whether overexpression of one of these two miR families can compromise IRE1α-induced augmentation of diabetic BMPC function. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, expression of IREα stimulated angiogenesis, as indicated by vessel-like tube formation in db/db BMPCs. However, this improvement in angiogenesis was suppressed by overexpression of pre-miR-466, pre-miR-200, or coexpression of pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 (Fig. 5A and B), indicating that the role of IRE1α in preserving angiogenesis and BMPC function is at least partially through repression of miR-466 and miR-200.

Figure 5.

Expression of pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 abolish the augmentation of BMPC tube formation induced by IRE1α overexpression. BMPCs were isolated from type 2 diabetic db/db mice and transfected with Ad-GFP or Ad-IRE1α at 500 MOI for 48 h. Pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 or both pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 were transfected into IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs. BMPC function was evaluated by tube formation on Matrigel. A: Representative pictures showing tube formation in IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs transfected with empty plasmid (control), pre-miR-466, pre-miR-200, or both pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200. Bar = 500 μm. B: Bar graph of tube formation quantification. n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. db/db BMPCs infected with Ad-GFP + control; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db BMPCs infected with Ad-IRE1 + control.

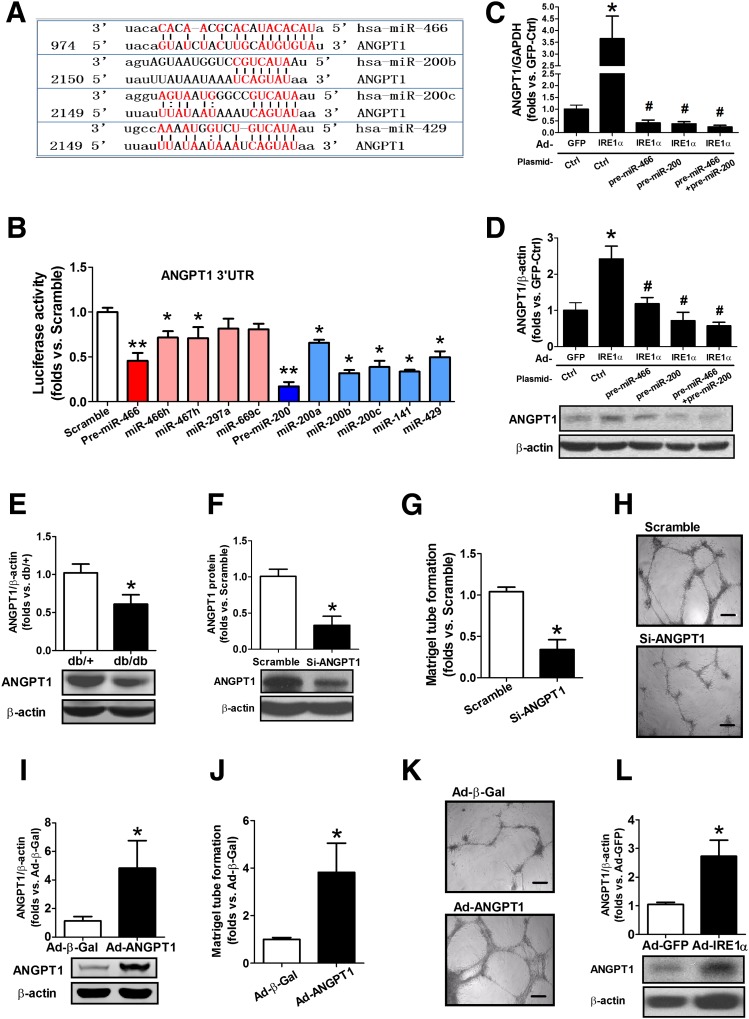

Expression of IRE1α Can Rescue the Defect of ANGPT1, a Direct Target of Both miR-466 and miR-200 Family miRs, in Diabetic BMPCs

Next, we determined the genes targeted by miR-466 and miR-200 under the regulation of IRE1α in BMPCs. A computer algorithm in PicTar and microRNA.org database indicates that miR members from the miR-466 and miR-200 families, including miR-466, miR-200b, miR-200c, and miR-429, all target the mRNA encoding an important proangiogenic factor, ANGPT1 (Fig. 6A). ANGPT1 is a secreted glycoprotein that activates endothelial cell–specific tyrosine-protein kinase (TEK/TIE2) receptor. ANGPT1 is known to be a key regulator that promotes normal angiogenesis during embryogenesis (30) and restores microvascular function in diabetes (31–33). To verify whether these miRs directly bind to the 3′-UTR of ANGPT1 mRNA, the complete 3′-UTR sequence of human ANGPT1 mRNA was introduced into a luciferase reporter system followed by transfection of either pre-miRs or individual mature miRs. The reporter analysis confirmed that ANGPT1 was the genuine target of miR-466 and miR-200 family miRs, including miR-466, miR-200b/c, and miR-429 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, whereas each mature miR can modestly suppress the ANGPT1 mRNA, coexpression of pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 exerted much greater repression, implicating the synergetic effects of miRs of the same pre-miR family on the translational control of ANFPT1 expression. To determine whether IRE1α regulates ANGPT1 through the miR pathway, we examined expression of ANGPT1 mRNA and protein in IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs upon transfection with the plasmid vectors expressing pre-miR-266 and pre-miR-200. The qRT-PCR results indicated that upregulation of the ANGPT1 mRNA, induced by overexpression of IRE1α, was reversed by expression of pre-miR-466 and/or pre-miR-200 (Fig. 6C). Consistently, Western blot analysis indicated that both pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 inhibited expression of ANGPT1 protein induced by IRE1α (Fig. 6D). These observations confirm that ANGPT1 expression is indeed regulated by IRE1α via suppressing miRs. In fact, db/db BMPCs only produced ∼50% of ANGPT1, compared with db/+ BMPCs (Fig. 6E). When ANGPT1 protein was downregulated by ∼60% by ANGPT1 siRNA in db/+ BMPCs, tube formation by BMPCs was severely impaired (Fig. 6F–H). Conversely, when ANGPT1 was overexpressed in db/db BMPCs (Fig. 6I), the tube formation was restored (Fig. 6J–K). Furthermore, overexpression of IRE1α significantly augmented ANGPT1 protein expression in db/db BMPCs by ∼2.5-fold (Fig. 6L). This evidence supports the essentiality of ANGPT1 in maintaining BMPC functions in diabetes and indicates that the ANGPT1 defect in diabetic BMPCs is largely attributed to the impaired IRE1α-miR regulatory axis.

Figure 6.

IRE1α overexpression can rescue the defect of ANGPT1, the direct target of miR-200 and miR-466 members, and impaired angiogenesis in diabetes. Luciferase vector carrying human ANGPT1 mRNA 3′-UTR sequence was cotransfected with pre-miR-466 or its mature miRs, pre-miR-200 or its mature miRs, or scramble oligo as controls. After 24 h, the cells were collected for detection of luciferase activity. A reduction in luciferase activity indicates direct binding. A: The putative binding sequences of miR-466 and miR-200 in the 3′-UTR of the ANGPT1 mRNA. The red text indicates the putative binding base pairs between the miRNA and the 3′-UTR of the mRNA based on a computer algorithm. B: Luciferase activities in T293 cells cotransfected with the plasmid vectors expressing the ANGPT mRNA 3′-UTR reporter; pre-miR-466; pre-miR-200; individual miRs including miR-466h, miR-200a/b/c/, miR-141, and miR-429; or scramble oligo. n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. scramble transfection; **P < 0.01 vs. scramble transfection. C: qRT-PCR analysis of ANGPT1 mRNA expression in IRE1α-overexpressing BMPCs transfected with the plasmid vector expressing pre-miR-466 or pre-miR-200 transfection. n = 6 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. GFP-Ctrl; #P < 0.05 vs. Ad-IRE1α-Ctrl. D: Western blot analysis of ANGPT1 protein in IRE1α-overexpressing BMPCs transfected with the plasmid vectors expressing pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200. n = 6 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. GFP-Ctrl; #P < 0.05 vs. Ad-IRE1α-Ctrl. BMPCs were isolated from individual db/db or db/+ mice. ANGPT1 mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. ANGPT1 protein expressions were determined by Western blot analysis. The db/db BMPCs were transfected with Ad-GFP or Ad-IRE1α at 500 MOI for 48 h. Pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 were transfected into IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs. ANGPT1 mRNA and protein levels were determined by qRT-PCRs and Western blot analyses, respectively. E: ANGPT1 protein expression in db/db vs. db/+ BMPCs. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+. F: ANGPT1 protein expression in db/+ BMPCs transfected with ANGPT1 siRNA (si) or scramble oligo. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. scramble oligo. G: Tube formation in db/+ BMPCs infected with ANGPT1 siRNA or scramble oligo. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+ BMPC scramble. H: Representative pictures of tube formation in db/+ BMPCs transfected with ANGPT1 siRNA or scramble oligo. Bar = 500 μm. I: ANGPT1 protein expression in db/db BMPCs transfected with either Ad-β-Gal or Ad-ANGPT1 at 100 MOI for 48 h. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-β-Gal. J: Tube formation in db/db BMPCs transfected with either Ad-β-Gal or Ad-ANGPT1. n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-β-Gal. K: Representative pictures of tube formation in db/db BMPCs transfected with either Ad-β-Gal or Ad-ANGPT1. Bar = 500 μm. L: ANGPT1 protein expression in db/db BMPCs infected with either Ad-GFP or Ad-IRE1α at 500 MOI for 48 h. n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-GFP.

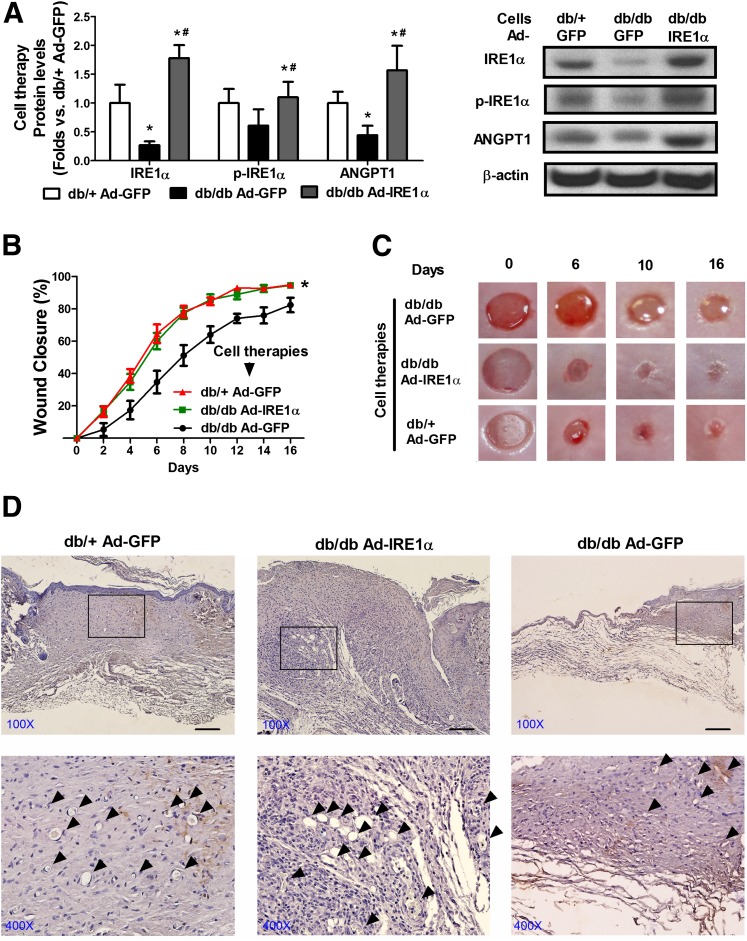

Cell Therapy Using Diabetic BMPCs With IRE1α Overexpression Improves Diabetic Wound Healing In Vivo

Progenitor cells are considered hopeful candidates for cell therapies in regenerative medicine (34,35). Therefore, the efficacy of genetically engineered BMPC therapy was tested in an excisional wound model as we previously established (17). Since our in vitro data showed that overexpression of IRE1α facilitates angiogenesis and upregulation of ANGPT1 in diabetic BMPCs, augmenting BMPC-mediated angiogenesis via correcting the IRE1α deficiency may improve wound healing in diabetic animals. To test this possibility, we infected db/db BMPCs with adenovirus expressing IRE1α for 48 h prior to cell therapies on diabetic wounds. Equal numbers of db/+ BMPCs or db/db BMPCs (106) infected with Ad-GFP served as normal and diabetic control cell therapies. Expression of total and phosphorylated IRE1α as well as ANGPT1 proteins in the infected BMPCs was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7B and C, from day 4 and throughout the healing course, diabetic wounds treated with IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs showed significantly faster closure than those treated with GFP-expressing db/db BMPCs, with concomitant augmentation of capillary formation as shown by the functional endothelial cell surface marker CD31 staining (day 8 samples) (Fig. 7D, arrows indicate capillary-like structure). Notably, wounds that received IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPCs were healed with a slightly keratinized epithelial layer, whereas wounds that received GFP-expressing db/db BMPCs still had large open wound areas (Fig. 7C). The healing curve of IRE1α-expressing db/db BMPC therapy was similar to that of the db/+ BMPC therapy. This suggests that IRE1α gene transfer significantly enhances the therapeutic potential of diabetic BMPCs, achieving efficacy comparable to healthy BMPCs.

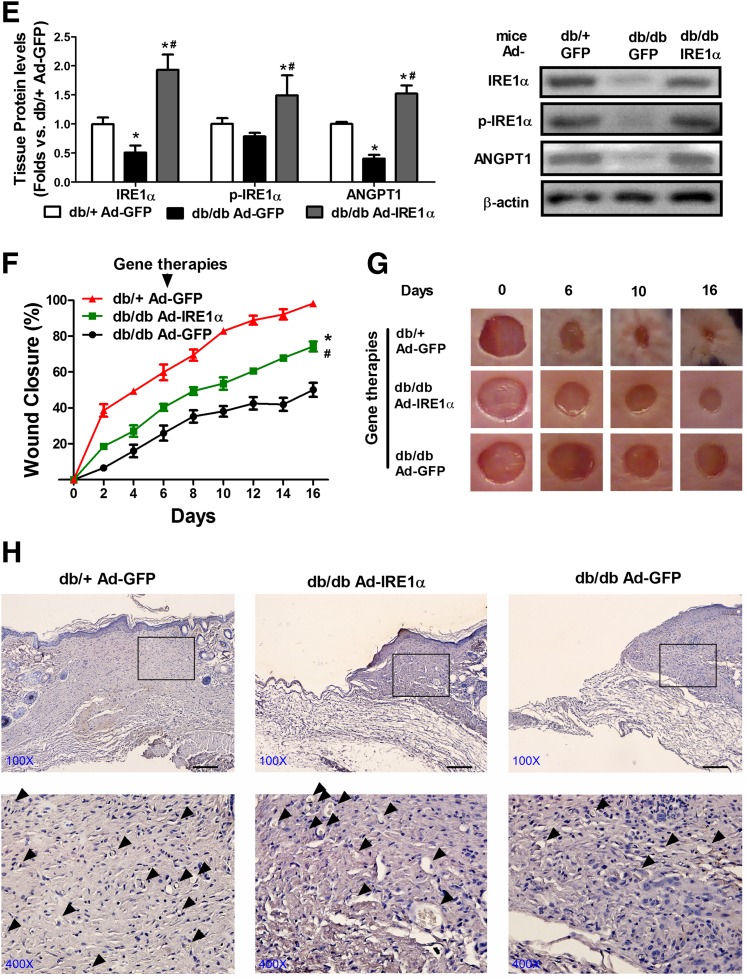

Figure 7.

Diabetic cell therapy with IRE1α overexpression or local gene transfer of IRE1α improves diabetic wound healing in vivo. Full thickness excisional wound (6 mm) was created on the back of each mouse. For cell therapies, db/db BMPCs were infected with Ad-IRE1α or Ad-GFP at 500 MOI for 48 h. Immediately after wounding, 1 × 106 Ad-IRE1α– or Ad-GFP–infected BMPCs were transplanted onto db/db wounds. For local gene transfer, db/db wounds were injected with 1 × 108 particle forming units Ad-IRE1α or Ad-GFP in 40 μL PBS solution. Wounds were covered with oxygen-permeable wound dressing (3M). Wound edge was traced and digitalized for percentage calculation. A: Western blot analysis of protein expressions of IRE1α, phosphorylated (p) form of IRE1α, and ANGPT1 in BMPCs that were used for cell therapies. Representative protein bands were shown on the right side. n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+ + Ad-GFP; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-IRE1α. B: Wound closure curves in db/db mice that received BMPC therapies. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/db BMPC + Ad-GFP. C: Representative pictures of diabetic wounds after the cell therapy. D: Capillary formation as evaluated by CD31 staining (brown) in wounds that received cell therapies. The arrowheads indicated a capillary-like structure at wound edge. Bar = 100 μm. E: Western blot analysis of protein expressions of IRE1α, phosphorylated form of IRE1α, and ANGPT1 in wound tissues transfected with either Ad-GFP or Ad-IRE1α. Representative protein bands were shown on the right side. n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/+ + Ad-GFP; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-IRE1α. F: Wound curves of local gene transfer. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Ad-GFP; #P < 0.05 vs. db/+ Ad-GFP. G: Representative pictures of diabetic wounds after the gene therapies. H: Capillary formation as evaluated by CD31 staining (brown) in wounds that received gene therapies. The arrowheads indicate a capillary-like structure at wound edge. Bar = 100 μm.

Direct Gene Transfer of IRE1α Partially Recovers Diabetic Wound Healing In Vivo

Furthermore, we sought to test whether direct IRE1α gene transfer to the wound bed can achieve the same success of IRE1α gene-engineered cell therapies. Immediately after the wounds were created on db/db mice, Ad-IRE1α or Ad-GFP was injected into the wound edge in the panniculus carnosus layer. Our results indicated that Ad-IRE1α–treated db/db wounds displayed accelerated wound closure from day 2, compared with Ad-GFP–treated db/db wounds (Fig. 7F and G). The wound capillary formation was also improved by the IRE1α gene transfer (Fig. 7H). By the end of the experiment, Ad-IRE1α–treated db/db wounds were healed by ∼70%, whereas Ad-GFP–treated db/db wounds were only healed by ∼50%, suggesting that IRE1α gene transfer is beneficial to diabetic wound healing. However, the effectiveness of IRE1α gene transfer is modest, since the Ad-IRE1α–treated db/db wounds were healed slower than the Ad-GFP–treated db/+ wounds (∼100% closure on day 16). Apparently, the IRE1α gene transfer in BMPC cell therapy showed much higher efficacy than the IRE1 gene transfer in local tissue (Fig. 7B and C). These results support the notion that IRE1α-induced acceleration of the wound healing process is through boosting angiogenic cell activities in diabetic bed sores where the direct IRE1a gene transfer failed to fully exert the effect due to dysfunctional tissues/cells.

Discussion

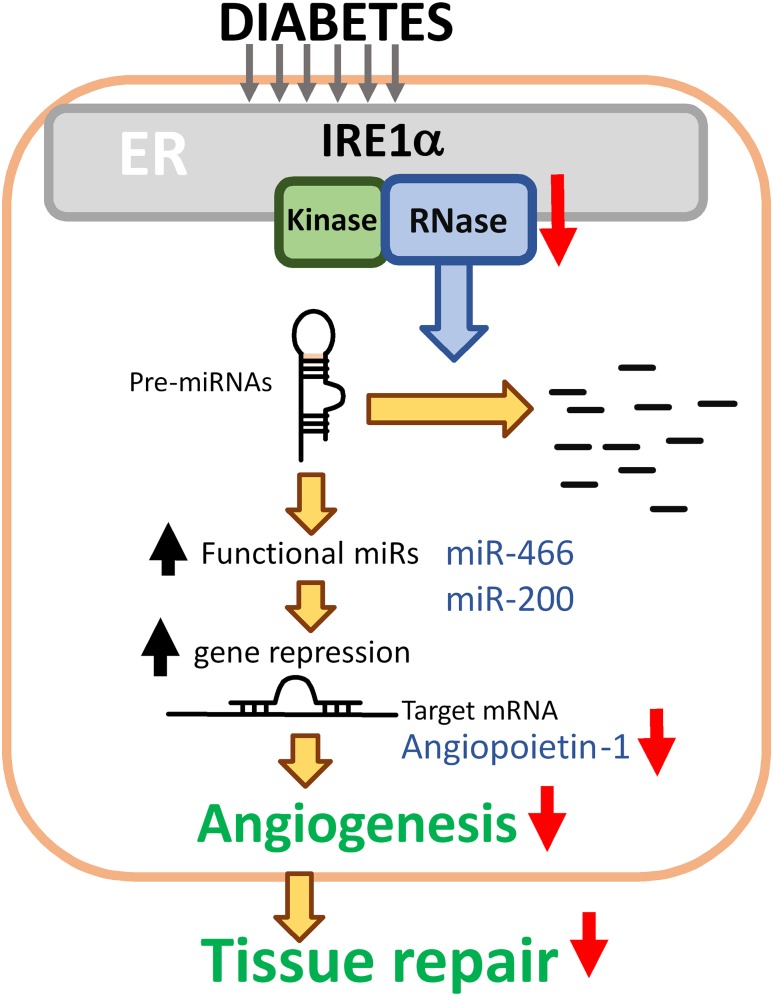

In this study, we have discovered that IRE1α promotes the angiogenic potential of diabetic BMPCs through modulating miR biogenesis, which is distinct from its role in mediating canonical UPR. Deficient IRE1α RNase activity is an important cause of the elevation of a subset of miRs in diabetes, including the miR-466 and miR-200 families, which contributes to the functional impairment of BMPCs. The suppression of miR expression by IRE1α occurs at the pre-miR level through the RIDD pathway and is not associated with XBP1 activation. The proangiogenic factor ANGPT1 is significantly attenuated in diabetic BMPCs, but the ANGPT1 defect can be rescued by IRE1α overexpression through repressing miR-466 and miR-200 family miRs. Diabetic BMPC therapies with IRE1α gene transfer resulted in improved wound capillary formation and fully recovered wound closure in diabetic mice in vivo. In aggregates, our study has demonstrated that deficient IRE1α RNase activity in diabetes bursts select miR expression, which leads to the suppression of ANGPT1 expression and subsequent disruption of angiogenesis, contributing to an impaired wound healing process (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Schema of hypothesis. Under the diabetic condition, IRE1α RNase activity degrades miR precursors, including pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200. These two miR families repress ANGPT1 mRNA translation, leading to downregulation of ANGPT1. Activity of IRE1α is suppressed in diabetic BMPCs. As a result, the downregulated ANGPT1 by increased miR-466 and miR-200 activities contributes to decreased angiogenesis and ineffective wound tissue repair under the diabetic conditions.

It has been suggested that ER stress represents an important aspect of metabolic insults in diabetes (36). Chronic hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, two major causative factors of type 2 diabetes, disrupts ER homeostasis and produces excessive unfolded/misfolded proteins in the ER lumen (37). However, differential activation of ER stress sensors may rely on specific stimuli and timing of the ER stress, exerting differential UPR programs. In the context of diabetes-related skin ulcers, the roles of UPR and angiogenesis have been addressed as separate events (38,39), yet little is known about the functional interplay between these two events. In our study, BMPCs from type 2 diabetic db/db mice display deficiencies in IRE1α protein expression, with no change in other ER sensors or canonical UPR signaling pathways, suggesting that the unique change of IRE1α may be related to the impaired function of BMPCs under the diabetic condition. Current reports suggest that metabolic tissues or cell types, such as liver (hepatocytes), adipose tissue (adipocytes), and pancreas (β-cells), are responding to metabolic stress through canonical UPR pathways (37,40,41). To date, little is known regarding how angiogenic cells, for example, BMPCs, are responding to metabolic stress in diabetes. Our studies demonstrated that metabolic stress regulates ER function in BMPCs through noncanonical UPR pathways, as the IREα-XBP1 pathway was repressed while other ER stress sensors or downstream pathways remained unchanged (Fig. 1E). Our supplemental data confirmed that the canonical UPR pathways in db/db type 2 diabetic BMPCs were not activated (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mechanism by which the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway is repressed under the diabetic condition is an interesting question. Many pathological changes in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, such as hyperglycemia, elevated levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation, are associated with ER stress response and expression of the ER stress sensor IRE1α. A recent study showed that obesity-associated chronic inflammation, an inflammatory stress condition found in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes animal models, can repress IRE1α activity by S-nitrosylation of IRE1α (42). This may partially explain why type 1 and type 2 diabetes lead to the similar change in IRE1α expression and activity. In addition to splicing the XBP1 mRNA, IRE1α can process select mRNAs or pre-miRs, leading to their degradation through the RIDD pathway (9–11). Recent studies suggested that IRE1α undergoes dynamic conformational changes and switches its functions depending on the duration and types of ER stress (12,13). Under acute ER stress, IRE1α forms oligomeric clusters to process XBP1 mRNA splicing during the acute phase. However, under physiological ER stress, IRE1α's functional specificity as an RNase shifts to cleaving primarily ER-targeted mRNAs or miRs via the RIDD pathway (9,11,43,44). Additionally, a recent study suggested the existence of mechanisms regulating XBP1 mRNA splicing through modulating recruitment of XBP1 mRNA to ER membranes (45). Therefore, there might be circumstances in which XBP1 mRNA splicing is not solely dependent on IRE1α RNase activity. However, when IRE1α is exogenously overexpressed in mammal cells, for example, adenovirus-mediated gene transfer, what we have observed is that overexpressed IRE1α functions to splice both XBP1 mRNA and precursor miRs. Bhatta et al. (46) reported that ER stress markers were elevated in bone marrow endothelial outgrowth cells in db/db mice at the age of 15 months, which were considered as aged mice (the life span of db/db mice is ∼18–20 months). Aging is a significant factor associated with ER stress and the UPR. Along with advanced aging, there is a shift in the balance between the protective adaptive response of the UPR and proapoptotic signaling where the protective arm is significantly reduced and the apoptotic arm is more robust (47). The discrepancy between observation of Bhatta et al. and ours reflects the dynamic changes in the balance of protective versus detrimental ER stress response in aging or the progression of diabetes.

Another important finding in this study is that the regulation of IRE1α on BMPC function or miR biogenesis in diabetes is independent of its canonical UPR pathway through activating XBP1. XBP1 is a well-known RNA substrate of IRE1α under ER stress (48). However, in diabetic BMPCs, in which IRE1α RNase activity is impaired, XBP1 mRNA splicing is not altered (Fig. 1D and E). Furthermore, the impaired angiogenesis in diabetic BMPCs can be rescued by overexpression of IRE1α, but not the activated XBP1 (Fig. 2C and D), thus confirming that XBP1 does not play a dominant role in IRE1α-regulated BMPC angiogenesis in diabetes. XBP1 knockdown did not induce significant impairment of BMPC function either (Fig. 2G–I). Importantly, our data show that neither miR expression nor upregulation of miRs caused by IRE1α deletion can be affected by activation of XBP1, suggesting that XBP1 does not function congruously with IRE1α on miR biogenesis. As a matter of fact, XBP1 has been reported to induce miR expression under certain circumstances (49,50), probably due to its role in the activation of gene expression as a transcription factor. Although the mechanism by which IRE1α selectively processes RNA substrates (miRs or XBP1 mRNA) remains to be elucidated, our study suggested that the IRE1α-regulated BMPC functional change and miR biogenesis in diabetes are independent of XBP1, a scenario distinct from the canonical IRE1α-UPR signaling pathway under the pharmacological or acute ER stress conditions.

Recent studies have uncovered a new dimension in which miRs regulate cellular behavior in response to physiological and pathophysiological stress (51). In this study, through miR microarray, we identified 44 significantly altered miRs in diabetic BMPCs, 31 of which were elevated (Fig. 3A). Previously, we found out that expression of Dicer, the rate-limiting enzyme that produces functional miRs, was decreased in diabetic BMPCs (17). On the basis of this, it was predicted that the majority of miRs in diabetic BMPCs are supposed to decrease. However, in this study, we have identified a subset of stress miRs that are controlled by IRE1α RNase activity and are actively participating in regulating BMPC function. IRE1α deletion results in a group of significantly upregulated miRs, many of which were similarly elevated in diabetic BMPCs (Fig. 3B and E). On the other hand, overexpression of IRE1α suppresses the expression of these miRs (Fig. 4A). This unveils the possibility that IRE1α may interfere with miR biogenesis and that impaired IRE1α RNase activity leads to the elevation of mature miRs in diabetes. Furthermore, pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 in IRE1α−/− BMPCs yielded significantly higher levels of mature miR-466 and miR-200s than that in the control BMPCs, indicating that IRE1α-induced reduction of miR biogenesis happened at the pre-miR level. Pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 are processed by IRE1α RNase because these two precursor miRs possess G/C sites at the stem-loop structure that match the IRE1α RNase target motif (Fig. 3F) (29). The IRE1α-mediated miR cleave assay indicated that pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 were indeed the RNA substrates of IR1α RNase activity (Fig. 3I). Importantly, augmentation of diabetic BMPC angiogenic function by restoring IRE1α activities was compromised by overexpression of pre-miR-466 and pre-miR-200 (Fig. 5A and B), indicating that the downregulation of miR-466 and miR-200 by IRE1α is critical to maintain effective angiogenesis in diabetes. In addition, we overexpressed Dicer in db/db BMPCs using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer and observed BMPC tube formation (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Our results indicated that overexpression of Dicer improved BMPC tube formation (Supplementary Fig. 2B and C), compared with their diabetic control. The previous report and ours indicated that Dicer controls a subset of miRs that improve angiogenesis (proangiogenic miRs) (17,52,53). Therefore, even though both Dicer and IRE1α improve angiogenesis and regulate miR biogenesis, Dicer and IRE1α improve angiogenesis and regulate miR biogenesis through distinct mechanisms.

Our study also provides the first evidence that miR-466 and miR-200 function in the same direction to regulate angiogenesis by targeting the same gene under the diabetic condition. Although previous reports have found that each of the miR-466 and miR-200 family miRs targets different genes in diverse types of cells (54–56), our study has confirmed that ANGPT1 is the direct target of miR-466 and miR-200 family miRs in BMPCs, as indicated by mRNA 3′-UTR binding assay and the gene and protein expression analysis (Fig. 6A–D). As a matter of fact, these two miR families have been reported to similarly respond to detrimental cellular stress and share comment target genes, for example, Nfat5 in immune cells and Dcx and Patah1b1 in neural stem cells (57,58). Our study delineated an important regulatory mechanism of miR-466 and miR-200 against the diabetic environment, in which the UPR transducer IRE1α functions as the upstream regulator and the proangiogenic factor ANGPT1 acts as an effector. Therefore, IRE1α-mediated miR decay represents a noncanonical UPR signaling that exerts an important role in promoting BMPC angiogenesis by protecting ANGPT1 from the miR attack under the diabetic condition.

The importance of IRE1α in angiogenesis has been further investigated in diabetic wound healing through the cell- or direct gene transfer–based therapeutic approach. IRE1α-expressing diabetic BMPCs demonstrated equal efficacy in promoting wound healing as normal BMPCs did, suggesting the effect of IRE1α gene transfer on restoring diabetic BMPC function, which was consistent with our in vitro findings. One of the important mechanisms contributing to the acceleration of diabetic wound healing by IRE1α expression was through promoting angiogenesis, as demonstrated by increased capillary density in wound beds (Fig. 7D). Additionally, wounds that received IRE1α-expressing BMPCs were covered by a slightly keratinized epidermis layer upon wound closure (Fig. 7C and D), suggesting that IRE1α-expressing BMPC therapy may facilitate wound re-epithelialization. This newly formed epidermis layer may be due to accelerated keratinocyte migration from the wound edge or may be constituted by the transformation of transplanted BMPCs, an interesting question to be elucidated in the future. The direct gene transfer of IRE1α to the diabetic wounds, however, did not prove as effective as the cell therapies. This may be due to the disrupted cellular components within the diabetic wound bed, which comprised the overall improvement of healing in the direct gene transfer approach. Additionally, we should clarify that there are paradoxical changes in angiogenesis coexisting in different tissues in diabetes. Diabetes possesses the phenotype of excessive formation of premature blood vessels in retina and a defect in the formation of small blood vessels in peripheral tissues, such as the skin. Our findings could be specific for peripheral angiogenesis but not diabetic retinopathy. In summary, our studies provide a novel concept that the IRE1α-mediated noncanonical UPR pathway plays an important role in promoting angiogenesis in diabetes. The related findings have important implications in tissue repair and regeneration associated with diabetic wounds.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the staff from the Department of Laboratory Animal Research at Wayne State University for providing excellent care for the animals.

Funding. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R01 DK109036-01 (to J.-M.W.), R01 DK090313-05, and ES017829 and the American Heart Association grants 09GRNT2280479 (to K.Z.) and 13SDG16930098.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. J.-M.W. designed research studies, conducted experiments for in vivo wound healing experiments, analyzed data from in vitro and in vivo experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Y.Q. assisted with experiments for BMPC culture and data acquisition. Z.-q.Y. and L.L. contributed to data interpretation. K.Z. contributed to the experimental design, data analysis, and interpretation; edited the manuscript; and provided the key reagents. J.-M.W. and K.Z. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db16-0052/-/DC1.

See accompanying article, p. 23.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available from http://wwwcdcgov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014StatisticsReporthtml. Accessed 24 October 2014

- 2.Demidova-Rice TN, Durham JT, Herman IM. Wound healing angiogenesis: innovations and challenges in acute and chronic wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2012;1:17–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 1997;275:964–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, et al. Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation 2002;106:2781–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loomans CJ, de Koning EJ, Staal FJ, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004;53:195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yalcin A, Hotamisligil GS. Impact of ER protein homeostasis on metabolism. Diabetes 2013;62:691–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 2008;454:455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response: a stress signaling pathway critical for health and disease. Neurology 2006;66(Suppl. 1):S102–S109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science 2006;313:104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upton JP, Wang L, Han D, et al. IRE1α cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science 2012;338:818–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.So JS, Hur KY, Tarrio M, et al. Silencing of lipid metabolism genes through IRE1α-mediated mRNA decay lowers plasma lipids in mice. Cell Metab 2012;16:487–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam AB, Koong AC, Niwa M. Ire1 has distinct catalytic mechanisms for XBP1/HAC1 splicing and RIDD. Cell Reports 2014;9:850–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 2007;318:944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim I, Xu W, Reed JC. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008;7:1013–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae ON, Wang JM, Baek SH, Wang Q, Yuan H, Chen AF. Oxidative stress-mediated thrombospondin-2 upregulation impairs bone marrow-derived angiogenic cell function in diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:1920–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JM, Tao J, Chen DD, et al. MicroRNA miR-27b rescues bone marrow-derived angiogenic cell function and accelerates wound healing in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurel M, Chevet E. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling: the microRNA connection. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013;304:C1117–C1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christian P, Su Q. MicroRNA regulation of mitochondrial and ER stress signaling pathways: implications for lipoprotein metabolism in metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014;307:E729–E737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, Wang S, Malhotra J, et al. The unfolded protein response transducer IRE1α prevents ER stress-induced hepatic steatosis. EMBO J 2011;30:1357–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JM, Isenberg JS, Billiar TR, Chen AF. Thrombospondin-1/CD36 pathway contributes to bone marrow-derived angiogenic cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes via Sonic hedgehog pathway suppression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013;305:E1464–E1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SW, Zhou Y, Lee J, et al. The regulatory subunits of PI3K, p85alpha and p85beta, interact with XBP-1 and increase its nuclear translocation. Nat Med 2010;16:429–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L, Xue Z, He Y, Sun S, Chen H, Qi L. A Phos-tag-based approach reveals the extent of physiological endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS One 2010;5:e11621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, et al. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:18081–18086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balaji S, LeSaint M, Bhattacharya SS, et al. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of insulin-like growth factor 1 enhances wound healing and induces angiogenesis. J Surg Res 2014;190:367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schröder K, Kohnen A, Aicher A, et al. NADPH oxidase Nox2 is required for hypoxia-induced mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells. Circ Res 2009;105:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006;8:315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulsmans M, De Keyzer D, Holvoet P. MicroRNAs regulating oxidative stress and inflammation in relation to obesity and atherosclerosis. FASEB J 2011;25:2515–2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prischi F, Nowak PR, Carrara M, Ali MM. Phosphoregulation of Ire1 RNase splicing activity. Nat Commun 2014;5:3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takakura N, Watanabe T, Suenobu S, et al. A role for hematopoietic stem cells in promoting angiogenesis. Cell 2000;102:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G, et al. Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J Clin Invest 2011;121:2278–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho CH, Sung HK, Kim KT, et al. COMP-angiopoietin-1 promotes wound healing through enhanced angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, and blood flow in a diabetic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:4946–4951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh GY. Orchestral actions of angiopoietin-1 in vascular regeneration. Trends Mol Med 2013;19:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao J, Yang Z, Wang JM, et al. Shear stress increases Cu/Zn SOD activity and mRNA expression in human endothelial progenitor cells. J Hum Hypertens 2007;21:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang M, Malik AB, Rehman J. Endothelial progenitor cells and vascular repair. Curr Opin Hematol 2014;21:224–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harding HP, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the development of diabetes: a review. Diabetes 2002;51(Suppl. 3):S455–S461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Back SH, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and type 2 diabetes. Annu Rev Biochem 2012;81:767–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee J, Ozcan U. Unfolded protein response signaling and metabolic diseases. J Biol Chem 2014;289:1203–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng R, Ma JX. Angiogenesis in diabetes and obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2015;16:67–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2006;69–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu S, Watkins SM, Hotamisligil GS. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatic lipid homeostasis and stress signaling. Cell Metab 2012;15:623–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, Calay ES, Fan J, et al. METABOLISM. S-nitrosylation links obesity-associated inflammation to endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction. Science 2015;349:500–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 2009;186:323–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han D, Lerner AG, Vande Walle L, et al. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell 2009;138:562–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coelho DS, Gaspar CJ, Domingos PM. Ire1 mediated mRNA splicing in a C-terminus deletion mutant of Drosophila Xbp1. PLoS One 2014;9:e105588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhatta M, Ma JH, Wang JJ, Sakowski J, Zhang SX. Enhanced endoplasmic reticulum stress in bone marrow angiogenic progenitor cells in a mouse model of long-term experimental type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2015;58:2181–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown MK, Naidoo N. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in aging and age-related diseases. Front Physiol 2012;3:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng L, Xiao Q, Chen M, et al. Vascular endothelial cell growth-activated XBP1 splicing in endothelial cells is crucial for angiogenesis. Circulation 2013;127:1712–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartoszewski R, Brewer JW, Rab A, et al. The unfolded protein response (UPR)-activated transcription factor X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces microRNA-346 expression that targets the human antigen peptide transporter 1 (TAP1) mRNA and governs immune regulatory genes. J Biol Chem 2011;286:41862–41870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng L, Li Y, Yang J, et al. XBP 1-deficiency abrogates neointimal lesion of injured vessels via cross talk with the PDGF signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:2134–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendell JT, Olson EN. MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell 2012;148:1172–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res 2007;101:59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 2007;100:1164–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seo M, Choi JS, Rho CR, Joo CK, Lee SK. MicroRNA miR-466 inhibits lymphangiogenesis by targeting prospero-related homeobox 1 in the alkali burn corneal injury model. J Biomed Sci 2015;22:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME. The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev 2008;22:894–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baseler WA, Thapa D, Jagannathan R, Dabkowski ER, Croston TL, Hollander JM. miR-141 as a regulator of the mitochondrial phosphate carrier (Slc25a3) in the type 1 diabetic heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012;303:C1244–C1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo Y, Liu Y, Liu M, et al. Sfmbt2 10th intron-hosted miR-466(a/e)-3p are important epigenetic regulators of Nfat5 signaling, osmoregulation and urine concentration in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1839:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shyamasundar S, Jadhav SP, Bay BH, et al. Analysis of epigenetic factors in mouse embryonic neural stem cells exposed to hyperglycemia. PLoS One 2013;8:e65945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.