A long-ago ancestor of the modern domestic dog is alive today in the form of the canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT). This tumor was first identified in the late 1800s when it was found to be transferred to new hosts through tumor cells (1). We now know the tumor is naturally transmitted from dog to dog by direct contact, primarily through coitus or any activity that permits the sloughing of cells (2). The tumors are rarely metastatic and most tumors regress within a few months leaving previously infected dogs with immunity to later infection. Most interesting, DNA analysis provides definitive evidence that all CTVTs found thus far are from a single source, one that existed before the dispersal of dog breeds around the world (3, 4).

In this issue of Science, Murchison et al. describe the first whole genome sequence of CVTV, sampled from the tumors of a random bred Australian Aboriginal camp dog and a pure-bred American cocker spaniel from Brazil. Sequence analysis revealed approximately 1.7 million somatic variants shared between the two tumors that are presumed to have arisen during transformation or in the years of passage, prior to separation of tumors by geographic boundaries. The number of somatic mutations is more than 100-fold larger than the average mutation load of a human tumor, indicating the long period over which mutations have accumulated within these cells and the number of alterations required to develop a stable colony.

The mutations were scattered throughout the genome with more than 10,000 genes carrying at least one predicted protein modifying mutation. This list encompasses nearly half of the annotated genes from the reference sequence (5) and illuminates a cadre of genes and proteins necessary for cellular replication versus organism development.

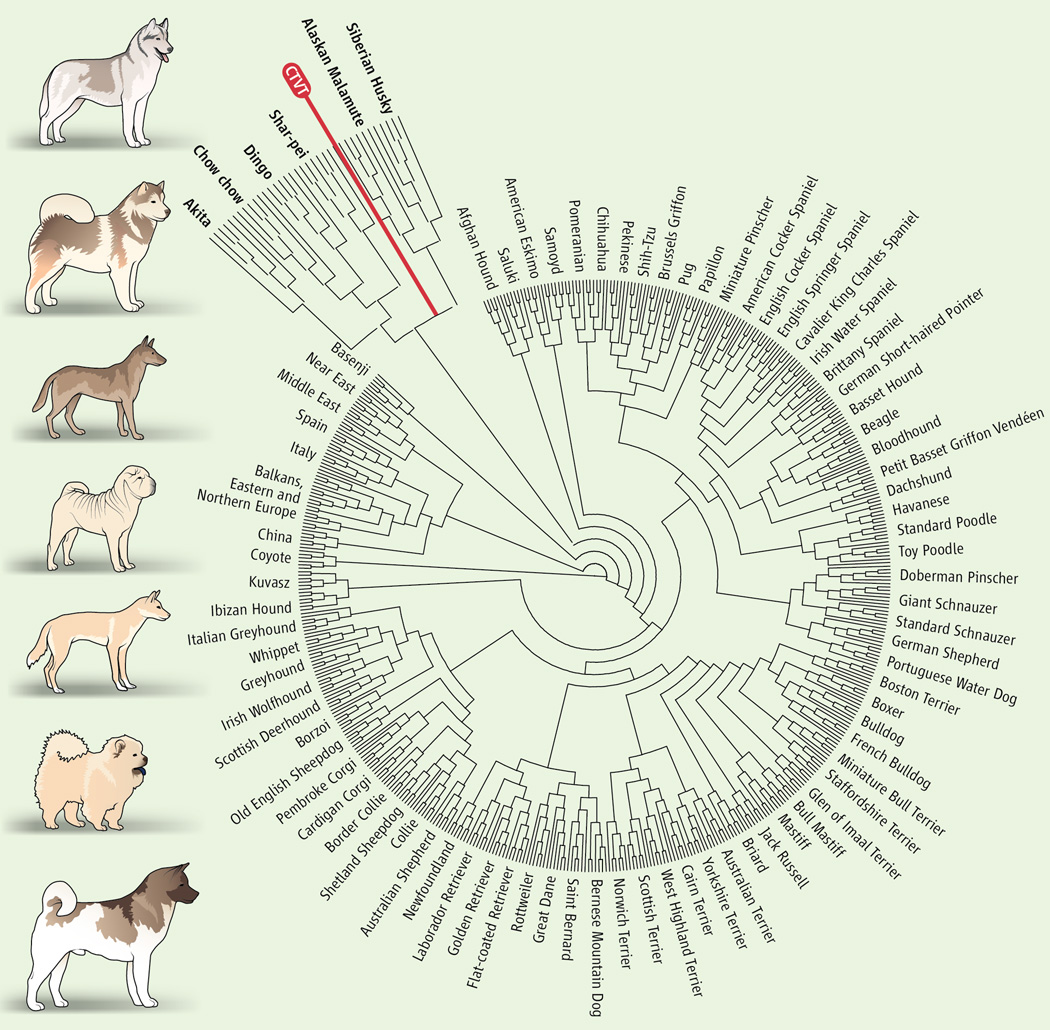

An examination of 23,782 SNP loci in CTVT and over 1100 modern dogs, wolves, and coyotes places the origin of the tumor at ~11,000 years before present with a second divergence of geographical strains of CTVT < 500 years ago. Principal component analysis suggests that the first dog with CTVT would be of ancient origin using modern classification schemes (6). Pairwise distance calculations place the Alaskan Malamute, a 4000 year old breed that originally came to America from Eastern Asia and Siberia, as the closest living relative of CTVT. In addition, the founder animal carried a mixture of “wolf-like and dog-like” alleles and was likely medium to large in size and had short, straight fur, a black or agouti coat, prick ears, and a pointy face. Fanciers will note that the morphologic description fits the modern Alaskan Malamute, but could also match that of any number of large spitz-type dogs.

Naturally occurring transmissible tumors are extremely rare. The only other known example is the Tasmanian devil facial tumor (DFTD), which was first identified in 1996 and has since spread rapidly throughout the population. Unlike the canine tumor, DFTD is highly virulent, metastasizes readily, and is ultimately fatal (7). Sequencing of DFTD revealed a 3–8-fold increase in somatic mutations compared to human tumors as opposed to the >100 fold increase in the canine tumor (8). This likely relates to the age of the tumor as DFTD has been acquiring mutations for ~20 years while CTVT has been evolving for >10,000 years. In contrast to CTVT, DFTD is driving its population toward extinction, which will lead eventually to its own demise (7). It is possible the canine tumor also started as an aggressive cancer that developed into a stable pathogen. A close comparison of the mutations found in each tumor type might reveal variants important for understanding the different behaviors of the two tumor types.

One fact both tumors share is that both appeared in populations of low diversity. The Tasmanian devil is a small island species with little heterogeneity (9). Analysis of the major histocompatibility loci in CTVT reveals that the source individual was inbred and is largely homozygous at the most variable DLA haplotypes (3). The restricted gene pools in both founding populations may have aided the initial establishment of a clonally transmissible tumor. In the case of the dog, however, the population did not stay isolated and the introduction of new MHC alleles may have kept tumor growth at bay. By comparison, Tasmanian devils are a small, closed population and there is therefore little hope of developing new resistance alleles.

We now have an image of a dog from the past based on a genomic profile taken from a clonally propagating population of cells. For generations modern dog has served as little more than culture medium for a genomic snap shot of what one lineage of dogs looked like 11,000 years ago. What more can this living fossil reveal? Murchison et al. have identified 646 genes that appear entirely dispensable for cellular life. Evolutionary studies of these genes may reveal enormous information as to their function and the processes they now participate in. CTVT has evolved methods of fooling the host’s immune system, allowing it to establish a colony long enough for transfer. Can elucidation of those mechanisms help us understand new means by which pathogens escape host surveillance? Once more the domestic dog provides us with a unique system for answering difficult questions, making one wonder what else is hiding in the doghouse.

Figure 1.

Genomic analysis places the founder of CTVT within the Ancient dog group. Shown are the images of dogs that are most similar to CTVT. From top to bottom: Siberian husky, Alaskan Malamute, A depiction of the CTVT founder, Shar-pei, Dingo, Chow chow, and Akita. The relationship tree shows the placement of the Ancient dog group (expanded) with 80 modern dog breeds and wolves. The tree is modified from vonHoldt et al.(6).

References

- 1.Novinski MA. Zur Frage uber die Impfung der Krebsigen Geschwulste. Zentralbl. Med. Wissensch. 1876;14:790. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlson AG, Mann FC. The transmissible venereal tumor of dogs: observations on forty generations of experimental transfers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1952 Jul 10;54:1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1952.tb39989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murgia C, Pritchard JK, Kim SY, Fassati A, Weiss RA. Clonal origin and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Cell. 2006 Aug 11;126:477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebbeck CA, Thomas R, Breen M, Leroi AM, Burt A. Origins and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution. 2009 Sep;63:2340. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derrien T, et al. Revisiting the missing protein-coding gene catalog of the domestic dog. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vonholdt BM, et al. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature. 2010 Apr 8;464:898. doi: 10.1038/nature08837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins CE, et al. Emerging disease and population decline of an island endemic, the Tasmanian devil Sarcophilus harrisii. Biol Conserv. 2006 Aug;131:307. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murchison EP, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the Tasmanian devil and its transmissible cancer. Cell. 2012 Feb 17;148:780. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddle HV, Sanderson C, Belov K. Characterization of major histocompatibility complex class I and class II genes from the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) Immunogenetics. 2007 Sep;59:753. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]