Abstract

BACKGROUND

Problem drinking that predates enlistment into military service may contribute to the overall burden of alcohol misuse in the Armed Forces; however, evidence bearing on this issue is limited. The current study examines prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among new US Army soldiers.

METHODS

Cross-sectional survey data were collected from soldiers reporting for basic combat training. The survey retrospectively assessed lifetime alcohol consumption and substance abuse/dependence, enabling estimation of the prevalence of lifetime binge drinking and heavy drinking in a sample of 30,583 soldiers and of probable alcohol use disorder (AUD) among 26,754 soldiers with no/minimal lifetime use of other drugs. Co-occurrence of mental disorders and other adverse outcomes with binge drinking, heavy drinking, and AUD was examined. Discrete-time survival analysis, with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function, was used to estimate associations of AUD with subsequent onset of mental disorders and vice versa.

RESULTS

Weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking was 27.2% (SE=0.4%) among males and 18.9% (SE=0.7%) among females; respective estimates for heavy drinking were 13.9% (SE=0.3%) and 9.4% (SE=0.4%). Among soldiers with no/minimal drug use, 9.5% (SE=0.2%) of males and 7.2% (SE=0.5%) of females had lifetime AUD. Relative to no alcohol misuse, binge drinking, heavy drinking, and AUD were associated with increased odds of all adverse outcomes under consideration [adjusted odds ratios (AORs)=1.5 to 4.6; ps<.001]. Prior mental disorders and suicidal ideation were associated with onset of AUD (AORs=2.3 to 2.8; ps<.001); and prior AUD was associated with onset of mental disorders and suicidal ideation (AORs=2.0 to 3.2, ps<0.005).

CONCLUSIONS

Strong bidirectional associations between alcohol misuse and mental disorders were observed in a cohort of soldiers beginning Army service. Conjoint recognition of alcohol misuse and mental disorders upon enlistment may provide opportunities for risk mitigation early in a soldier's career.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are prevalent and impactful in the United States and worldwide, contributing markedly to the global burden of disease (Whiteford et al., 2013). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III (NESARC-III), which surveyed a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized civilian adults, has documented the high prevalence and morbidity associated with AUDs in the United States (Grant et al., 2015).

Alcohol misuse and AUDs are also prevalent among US military personnel. One-fifth of military personnel were classified as heavy drinkers (consuming 5 or more drinks once a week or more) in a recent survey representing the total active force (Mattiko et al., 2011). Population-based health behavior surveys of active duty personnel administered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) revealed significant increases in binge drinking (35% to 47%) and heavy drinking (15% to 20%) from 1998-2008 that were highest among those with combat exposure (Bray et al., 2013). A study of mental disorders in a representative sample of 671 Ohio Army National Guard members found that AUD was the most common lifetime disorder, with a prevalence of 44% (Fink et al., 2016a). U.S. military veterans also have a high prevalence (42%) of lifetime AUD (Fuehrlein et al., 2016).

Alcohol misuse profoundly impacts servicemembers’ individual health and well-being (Waller et al., 2015). In the aforementioned survey of US military personnel representing the total active force, a dose-response relationship was observed between drinking level and serious consequences such as accidents and injuries; and occupational, relational, and legal problems related to alcohol use (Mattiko et al., 2011). Heavy drinking was associated with a particularly marked increase in these adverse consequences. Heavy drinking also has been found to be associated with increased risk for suicidal behaviors among Army soldiers (Mash et al., 2014). Similarly, AUDs were associated with increases over time in depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms among Ohio National Guard members (Sampson et al., 2015). Beyond impacts on individual health and functioning, alcohol misuse burdens the Armed Forces as an organization, with dose-response relationships observed between level of drinking and productivity loss (Mattiko et al., 2011).

These observations underscore the importance of gaining a contemporary, population-based perspective on the extent of alcohol use problems and concomitant adverse outcomes among US military personnel. Estimates derived from the overall active force are informative and actionable; however, they leave unanswered questions regarding potential contributors to the burden of alcohol misuse in the military (e.g., relative roles of selection factors versus experiences related to military service). What is also needed is information pertaining to pre-enlistment experiences and conditions that may shape the mental health needs of servicemembers as they integrate into military culture and encounter military-specific exposures such as deployment.

Available evidence suggests that mental disorders in general – and substance use problems in particular – commonly emerge prior to servicemembers’ enlistment in the Armed Forces. An analysis from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) found that approximately 38% of soldiers with 30-day Substance Use Disorder (SUD; due to alcohol and/or drug misuse) reported onset prior to their enlistment in the US Army (Kessler et al., 2014). More than 40% of Ohio National Guard members with lifetime AUD reported onset of the disorder prior to enlistment (Fink et al., 2016a). These studies established pre-enlistment onset via retrospective self-report. In contrast, a report from the Army STARRS New Soldier Study (NSS; also the basis for the current analysis) estimated prevalence of lifetime SUD (due to alcohol and/or drug use) among new soldiers just starting basic combat training (Rosellini et al., 2015). Lifetime prevalence of SUD in these incoming soldiers was 12.6%, which although substantial did not differ significantly from the prevalence (13.9%) observed in a demographically-matched civilian sample. Another survey of US Navy recruits during 2011-2014 found that approximately 40% of those aged 21 and older had engaged in risky drinking prior to beginning their Navy service (Derefinko et al., 2016). Rates were even higher among younger recruits (<21 years old), with more than half endorsing risky drinking and approximately 10% endorsing harmful/hazardous drinking prior to beginning their military service.

The present study provides a novel perspective on the burden of alcohol misuse in the military by examining the prevalence and correlates of lifetime alcohol misuse among soldiers entering the US Army. We build on prior investigations of this Army STARRS sample (Rosellini et al., 2015) by focusing specifically on problem drinking (versus SUD) and by examining the full spectrum of alcohol misuse. We estimate the prevalence of lifetime binge drinking and heavy drinking in a representative sample of new Army soldiers, as well as lifetime and 12-month AUD in a subsample with no or minimal lifetime use of other drugs. We also extend prior research by examining prevalence of mental disorders and other adverse outcomes among subgroups of soldiers with histories of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and AUD. Finally, to improve understanding of the nature of associations between alcohol misuse and mental disorders, we utilize age-of-onset data to determine whether AUD is associated with increased risk of subsequent mental disorders, and conversely whether certain mental disorders are associated with increased risk of onset of AUD. These association analyses may elucidate other vulnerabilities and mental health needs of soldiers with pre-enlistment histories of alcohol misuse; and provide information about risk factors for onset of AUD in this population.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

Prior reports describe the design and methodology of Army STARRS (Kessler et al., 2013a, Ursano et al., 2014). The New Soldier Survey (NSS) component was administered at three basic training installations during the period of April 2011 to November 2012. Soldiers reporting for Basic Combat Training were surveyed while completing intake procedures. Representative samples of 200-300 soldiers per site were selected on a weekly basis to attend a 30-minute informed consent session that covered the study's purposes, procedures, and protections against breach of confidentiality. Nearly all (99.9%) selected soldiers consented to the self-administered questionnaire (SAQ), and 93.5% of those who consented completed the full SAQ. Incomplete SAQs were mainly due to time constraints (e.g., cohorts arriving late or having to leave early). Of soldiers who completed the SAQ, 77.1% consented to linkage of responses to their Army/DoD administrative records. Recruitment, consent, and data protection procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of all collaborating institutions.

As in prior NSS studies (Ursano et al., 2015, Rosellini et al., 2015, Nock et al., 2015), the sample was constrained to respondents whose complete SAQ data were successfully linked to their Army/DoD Administrative records (n=38,507). Analyses incorporate a combined analysis weight that adjusts for differential administrative record linkage consent among SAQ completers and includes a post-stratification of these consent weights to known demographics and service traits of the population of soldiers attending Basic Combat Training during the study period. A description of NSS clustering and weighting is available in a previous report devoted to those topics (Kessler et al., 2013b).

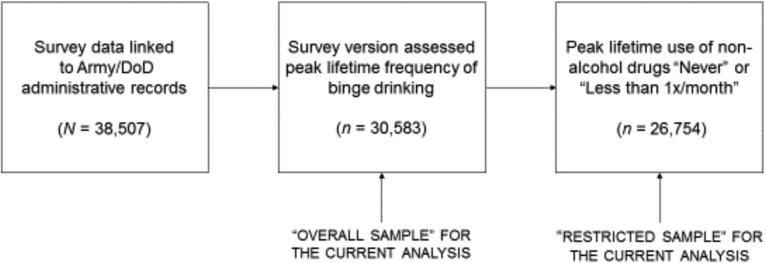

For this investigation of alcohol misuse, additional sample restriction was necessary (Figure 1) because the item assessing consumption of 5 or more alcoholic drinks in one day (i.e., alcohol binges; used to derive binge drinking and heavy drinking variables) was added to the NSS survey partway into data collection. Analyses are therefore based on data from participants in the third and fourth (of 4 total) NSS administrations (n=30,583). We report prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, heavy drinking, and non-alcohol substance use among these respondents, who for the purposes of this report are referred to as the “overall sample”.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, heavy drinking, and drug use was estimated in the sample of survey respondents who consented to linkage of their responses to their Army/DoD administrative records, and who were administered a version of the survey instrument that contained the item assessing peak lifetime frequency of binge drinking (“Overall Sample”). Due to a limitation of the survey design, prevalence of probable Alcohol Use Disorder could only be estimated in a subsample of those soldiers who endorsed no or minimal lifetime use of non-alcohol drugs (“Restricted Sample”).

The current study aimed to examine the full range of alcohol misuse including Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD); however, the NSS survey did not discriminate between substance use disorder symptoms resulting from alcohol versus other substance use. We therefore conducted analyses of the prevalence and correlates of probable Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) in a subsample that conservatively excluded respondents who endorsed lifetime use of non-alcohol substances at a frequency of “1-3 times per month” or greater. The subsample of soldiers with no or minimal use of non-alcohol substances (n=26,754) is henceforth called the “restricted sample.”

Measures

Binge Drinking and Heavy Drinking

Items assessing frequency of alcohol use were adapted from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)(Kessler and Ustun, 2004) for use in Army STARRS. Respondents rated frequency of any alcohol use (1 or more drinks) and of alcohol binges (5 or more drinks). Respondents rated frequency of use for “the times when you used each...substance most often,” using the categories “never,” “less than once a month,” “1-3 days a month,” “1-2 days a week,” “3-4 days a week,” or “every or nearly every day” (coded 0-5 for analysis). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) definition of binge drinking is “drinking 5 or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days”. Thus, ratings ≥2 (“1-3 days a month”) for drinking 5 or more alcoholic drinks were considered positive for lifetime Binge Drinking. The SAMHSA definition of heavy drinking is “drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days.” Therefore, ratings ≥3 (“1-2 days a week”) for drinking 5 or more alcoholic drinks were considered positive for lifetime Heavy Drinking.

Other (Non-Alcohol) Substance Use

Survey items also assessed peak lifetime frequency of use of marijuana/hashish; spice (e.g., K2, plant food, fake weed); any other illegal drug (e.g., cocaine, ecstasy, speed, LSD, poppers); prescription stimulants (e.g., Adderall, diet pills, amphetamines); prescription tranquilizers or muscle relaxers (e.g., Ativan, Valium) or sedatives (e.g., Ambien, Quaalude); and prescription pain relievers (e.g., codeine, OxyContin). Items assessing the final three substance types specified that respondents should rate use that occurred “without a doctor's prescription or more than prescribed or to get high, buzzed, or numbed out.” Nicotine use also was assessed but will be the focus of a separate report. Respondents indicated whether they had used each substance “never,” “less than once a month,” “1-3 days a month,” “1-2 days a week,” “3-4 days a week,” or “every or nearly every day” (coded 0-5 for analysis). Ratings ≥2 (“1-3 days a month”) were considered positive for estimating lifetime prevalence of non-alcohol substance use in the overall sample.

Probable Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Diagnosis of SUD was based on self-administered CIDI Screening Scales (CIDI-SC)(Kessler et al., 2013c). Respondents who endorsed any substance use were asked to think about the period of their lives when they used the most alcohol (for those with no lifetime use of other drugs), drugs (for those with no lifetime use of alcohol), or alcohol or drugs (for those with lifetime alcohol and other drug use). Respondents then rated frequency of problems related to substance use as “never,” “less than once a month,” “1-3 days a month,” “1-2 days a week,” “3-4 days a week,” or “every or nearly every day.” Problems related to substance use that were assessed in the NSS were: interference with work, school, or home responsibilities; interpersonal problems; use in situations that could be dangerous to self or others (e.g., when driving or using a weapon); lack of control over use; problems with law enforcement; concern about being unable to use in certain situations; worrying about level of use; feeling a need to cut down or stop use; feeling guilty about use; and needing an eye-opener to relieve withdrawal symptoms. An algorithm that employed respondents’ ratings of these items was used to diagnose lifetime SUD, and the diagnosis was validated against structured clinical interviews in a clinical calibration study (Kessler et al., 2013c).

SUD data from respondents whose lifetime use of non-alcohol drugs was “never” or “less than once a month” were considered in this study. Given the absence/rarity of non-alcohol drug use in this restricted sample, we inferred that SUD items had been rated in reference to alcohol use and labeled cases of lifetime SUD as “probable lifetime AUD”. To establish past-year AUD, we used a survey item that inquired how many months out of the past 12 respondents had these types of problems related to their substance use. Responses ≥1 month were coded positive for probable past-year AUD. Age-of-onset was assessed with an item inquiring how old the respondent was the first time he or she had the reported problems related to substance use. Age-of-onset was used to establish the temporal relationship of AUD to other diagnoses.

Co-occurring mental disorders

Associations of alcohol misuse with mental disorders were examined. Diagnoses were established using the CIDI-SC and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist, and validated in a prior study (Kessler et al., 2013c). Mental disorders under consideration for this report were lifetime and past 30-day PTSD, major depressive episode (MDE), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and panic disorder (PD); and lifetime mania/hypomania. Ages of onset were assessed and used to determine temporal relationships of these conditions with AUD.

Other co-occurring adverse outcomes

Suicidal ideation was assessed using a modified version of the Columbia Suicidal Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2011). Co-occurrence of alcohol misuse with lifetime and past 30-day suicidal ideation was considered. Probable lifetime traumatic brain injury (TBI) was assessed and defined as endorsing any lifetime head, neck, or blast injury that was associated with loss or alteration of consciousness or memory lapse (Stein et al., 2015). Finally, the NSS assessed occurrence of (1) any past-year motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) while the respondent was driving, and (2) any past-year MVAs that caused injury or property damage for which the respondent was at fault; these outcomes also were examined in relation to alcohol misuse.

Socio-demographic and Army service variables

Models of associations between AUD and PTSD, MDE, GAD, PD, mania/hypomania, and suicidal ideation adjusted for time-varying person-year and education and time-invariant sex, race-ethnicity, religion at the time of the interview, marital status at the time of the interview, parental education, and nativity. All models also adjusted for Army service component (Regular Army, National Guard, or Army Reserve) and site of Basic Combat Training.

Data Analysis

Weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, heavy drinking, and non-alcohol substance use was calculated in the overall sample (N=30,583). Weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, lifetime heavy drinking, lifetime probable AUD, and probable past-year AUD were calculated in the restricted sample of respondents with no or minimal non-alcohol drug use (n=26,754). Missing data were rare (≤1.8%) and left missing in the analyses. Pearson's Χ2 was used to test for sex differences in the prevalence of alcohol misuse. Supplementary analyses also used Pearson's Χ2 to evaluate differences by race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, or Other), age group (18-20, 21-23, or 24 and older), and Army service component (Regular Army, Army National Guard, or Army Reserve).

In the restricted sample, weights-adjusted logistic regression models were fit to estimate associations of the different types of alcohol misuse (binge drinking, heavy drinking, probable lifetime AUD, and probable past-year AUD) with mental disorders and other adverse outcomes, adjusting for socio-demographic and Army service variables. Each alcohol misuse category was compared to the reference group “No Lifetime Alcohol Misuse”.

Age-of-onset data were used to create person-year datasets for discrete-time survival analysis (Singer and Willett, 2003) of the associations of (1) temporally prior AUD with subsequent onset of PTSD, MDE, GAD, PD, mania/hypomania, and suicidal ideation; and (2) temporally prior mental disorders/ suicidal ideation with subsequent onset of AUD. The person-year file was limited to 12-33 years of age due to exceedingly low prevalence of AUD and mental disorders prior to age 12 and of enlistment after age 33. All models adjusted for socio-demographic and Army service variables and were fit using a logistic link function (Efron, 1988). Survival coefficients were exponentiated to create odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals; the interpretation of OR in the discrete time survival models indicates the effect of a given predictor on the hazard. Because NSS data were clustered and weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization method was used to estimate standard errors. Multivariable significance was examined using design-based Wald Χ2 tests. Two-tailed p values <.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using the software R Version 3.0.2 (R Core Team, 2013) with the R library survey (Lumley, 2004, Lumley, 2012) to estimate the discrete-time survival models.

Results

Prevalence of Binge Drinking, Heavy Drinking, and Non-Alcohol Substance Use

Table 1 shows weighted lifetime prevalence of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and non-alcohol substance use in the overall sample. Binge drinking [Χ2(1)=165.96, p<.001] and heavy drinking [Χ2(1)=84.37, p<.001] were substantially more prevalent among male than female soldiers. Male soldiers also displayed higher prevalence of marijuana use [Χ2(1)=8.69, p=.003] and synthetic marijuana use [Χ2(1)=12.72, p<.001]. Supplementary Table 1 shows prevalence of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and non-alcohol substance use by race/ethnicity, age group, and service component. Substantive differences included higher prevalence of binge drinking and heavy drinking among soldiers aged 21 and older compared to those aged 18-20. Binge drinking and heavy drinking were also more prevalent among White soldiers than among members of other race/ethnicity groups, with Black soldiers displaying the lowest prevalence. Variation in the proportion of females across race/ethnicity groups may contribute to these differences; among subgroups of soldiers identifying as White, Black, Hispanic, and Other, the proportions of females were 12.1%, 26.9%, 17.9%, and 17.3%, respectively.

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, heavy drinking, and non-alcohol substance use in new Army soldiers

| Overall (N=30,583) | Males (n=25,736) | Females (n=4847) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binge Drinking | 25.8% (0.4%) | 27.2% (0.4%) | 18.9% (0.7%) |

| Heavy Drinking | 13.1% (0.2%) | 13.9% (0.3%) | 9.4% (0.4%) |

| Marijuana/hashish | 8.5% (0.2%) | 8.7% (0.2%) | 7.6% (0.5%) |

| Synthetic marijuana/spice | 3.6% (0.1%) | 3.8% (0.2%) | 2.6% (0.3%) |

| Any other illegal drug | 2.2% (0.1%) | 2.3% (0.1%) | 2.1% (0.2%) |

| Prescription analgesics | 3.6% (0.1%) | 3.6% (0.1%) | 3.4% (0.2%) |

| Prescription stimulants | 3.0% (0.1%) | 3.0% (0.1%) | 3.0% (0.2%) |

| Prescription tranquilizers | 2.1% (0.1%) | 2.1% (0.1%) | 2.3% (0.2%) |

Notes. Values are weighted percentage (standard error). Binge drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks per day “1-3×/month” or more. Heavy drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks per day 1-2×/week” or more. Non-alcohol drug use was considered present if peak lifetime frequency was “1-3×/month” or more. For prescription drugs, survey items specified that respondents should only consider use that occurred without a doctor's prescription; in excess of the amount prescribed; or to get “high, buzzed, or numbed out”.

Remaining results are based on the restricted sample of respondents with no or minimal non-alcohol drug use. Table 2 shows weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, lifetime heavy drinking, probable lifetime AUD, and probable past-year AUD in the restricted sample. Each type of alcohol misuse was less prevalent among women [Χ2(1)=8.52 to 142.66, ps<.005]. Supplementary Table 2 provides prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, lifetime heavy drinking, probable lifetime AUD, and probable past-year AUD by race/ethnicity, age group, and service component in the restricted sample. Race/ethnicity and age group differences for binge drinking and heavy drinking were analogous to those found in the overall sample, though in some cases less pronounced. Probable lifetime AUD was slightly more prevalent among soldiers who identified their race as Other or White than among those who identified as Hispanic or Black; and among those aged 21 and older.

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence of lifetime binge drinking, heavy drinking, and probable alcohol use disorder among new soldiers with infrequent (<monthly)1 lifetime use of other substances

| Overall (n=26,754) | Males (n=22,452) | Females (n=4302) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binge Drinking | 20.7% (0.3%) | 22.0% (0.4%) | 14.3% (0.7%) |

| Heavy Drinking | 9.3% (0.2%) | 9.9% (0.2%) | 6.4% (0.5%) |

| Probable lifetime AUD | 9.1% (0.2%) | 9.5% (0.2%) | 7.2% (0.5%) |

| Probable past-year AUD | 5.7% (0.2%) | 5.9% (0.2%) | 4.7% (0.5%) |

Notes. AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder. Values are weighted percentage (standard error). Binge drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks per day “1-3×/month” or more. Heavy drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks per day “1-2×/week” or more.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a less stringent exclusion criterion for non-alcohol drug use. Respondents whose peak lifetime use of non-alcohol drugs was “1-3×/month” were included in the sensitivity analysis sample, in addition to those whose peak frequency was “Never” and “Less than 1×/month” (n = 27,620). Prevalence estimates for Binge Drinking, Heavy Drinking, probable lifetime AUD, and probable past-year AUD were 21.7% (SE=0.3%), 9.9% (SE=0.2%), 10.0% (SE=0.2%), 6.3% (SE=0.2%), respectively (i.e., within 1% of the values reported in this table).

Co-occurrence of Alcohol Misuse with Mental Disorders and other Adverse Outcomes

Relative to soldiers with no lifetime alcohol misuse, and adjusting for socio-demographic and Army service variables, the prevalence of all adverse outcomes under consideration was significantly higher among soldiers with lifetime binge drinking (AORs=1.53 for lifetime suicidal ideation to 2.08 for lifetime PD; ps<.001), lifetime heavy drinking (AORs=1.67 for past-year MVA while driving to 2.61 for lifetime mania/hypomania; ps<.001), probable lifetime AUD (AORs=1.74 for past-year MVA while driving to 3.66 for past-month suicidal ideation; ps<.001), and probable past-year AUD (AORs=1.99 for past-year MVA while driving to 4.55 for past-month suicidal ideation; ps<.001). See Supplementary Table 3 for full results of these association analyses.

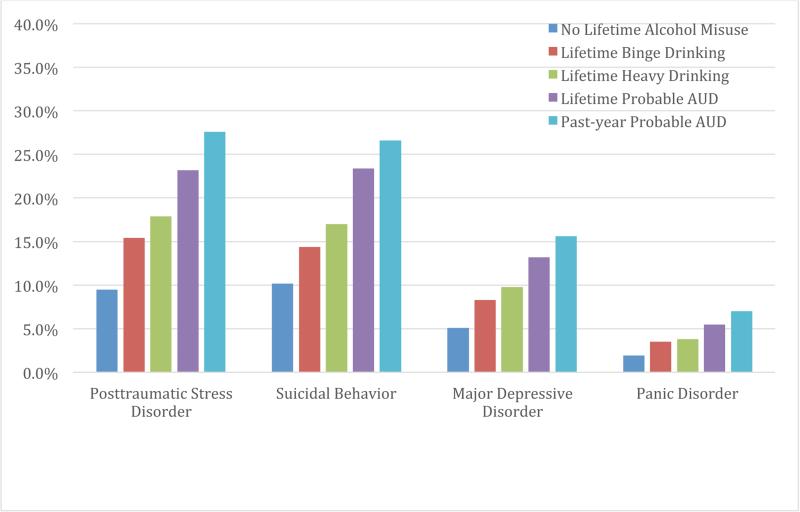

Figure 2 displays prevalence of selected conditions (lifetime PTSD, suicidal ideation, MDE, and PD) by alcohol misuse category. As the figure illustrates, prevalence of adverse outcomes generally increased in a dose-response fashion as severity of alcohol misuse increased. The complete set of comorbidity estimates is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2.

Weighted prevalence of lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal behavior, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder by categories of alcohol misuse. Standard errors range from 0.1% to 1.5%. Estimates were derived from the restricted sample of 26,754 new soldiers with no or minimal lifetime use of non-alcohol drugs. All four co-occurring conditions were more prevalent among soldiers with lifetime binge drinking, lifetime heavy drinking, lifetime probable AUD and past-year probable AUD than among soldiers with no lifetime alcohol misuse (all p's<.001).

Among soldiers with probable lifetime AUD, prevalence of co-occurring lifetime mental disorders ranged from 5.5% (SE=0.6%) for PD to 23.2% (SE=1.1%) for PTSD. Other highly prevalent lifetime outcomes among those with probable lifetime AUD were TBI (64.3% vs. 39.4% of those with no alcohol misuse) and suicidal ideation (23.4% vs. 10.2% of those with no alcohol misuse). Among soldiers with probable past-year AUD, prevalence of co-occurring 30-day mental disorders ranged from 5.6% (SE=0.7%) for PD to 20.2% (SE=1.3%) for PTSD.

Associations of Mental Disorders and Suicidal Ideation with Onset of Probable Alcohol Use Disorder

The first set of discrete time-survival models estimated associations of temporally prior PTSD, MDE, GAD, PD, mania/hypomania and suicidal ideation with subsequent onset of probable AUD. After adjusting for socio-demographic and Army service variables, each mental disorder was associated with increased odds of subsequent AUD. Adjusted odds-ratios for the predictors of interest ranged from 2.31 for PTSD to 2.85 for mania/hypomania (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations of temporally prior mental disorders with subsequent onset of alcohol use disorder among new soldiers with infrequent (<monthly) lifetime use of other substances (n=26,754)

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 2.31 | 1.91-2.79 | <.001 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 2.70 | 2.28-3.21 | <.001 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 2.73 | 2.32-3.21 | <.001 |

| Panic Disorder | 2.66 | 1.97-3.60 | <.001 |

| Mania/hypomania | 2.85 | 2.39-3.39 | <.001 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 2.58 | 2.29-2.90 | <.001 |

Note. Results are from six separate discrete-time survival models of onset of alcohol use disorder, with the row label indicating the predictor of interest. Odds ratios reflect adjustment for socio-demographic and Army service variables.

Associations of Probable Alcohol Use Disorder with Onset of Other Mental Disorders

The second set of discrete time-survival models estimated associations of temporally prior AUD with subsequent onset of other mental disorders/suicidal ideation. After adjusting for socio-demographic and Army service variables, probable AUD was associated with increased odds of subsequent PTSD, MDE, GAD, PD, mania/hypomania, and suicidal ideation. Adjusted odds-ratios for AUD ranged from 1.98 for the outcome of suicidal ideation to 3.15 for the outcome of PTSD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of temporally prior alcohol use disorder with subsequent onset of other mental disorders among new soldiers with infrequent (<monthly) peak lifetime use of other substances (n=26,754)

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 3.15 | 2.67-3.72 | <.001 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 2.92 | 1.56-5.46 | <.001 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 2.24 | 1.76-2.84 | <.001 |

| Panic Disorder | 2.12 | 1.27-3.53 | 0.004 |

| Mania/hypomania | 2.68 | 1.88-3.81 | <.001 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 1.98 | 1.51-2.59 | <.001 |

Note. Results are from separate discrete-time survival models of onset of the six different mental disorders, with alcohol use disorder as the predictor and the row label indicating the outcome in question. Odds ratios reflect adjustment for socio-demographic and Army service variables.

Discussion

In this study of new soldiers reporting on their alcohol and substance use prior to entering the military, we found that more than 1 in 4 men (27.2%) reported binge drinking and 1 in 7 reported heavy drinking (13.9%); prevalence was lower in women (18.9% and 9.4%, respectively). With the exception of lifetime marijuana use (reported by 8.7% of men and 7.6% of women), endorsement of other drug use was below 4% for both males and females.

Prevalence and correlates of probable Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) were estimated only among soldiers with minimal lifetime use of non-alcohol drugs, a study limitation that is discussed below. Some 9.5% of male soldiers and 7.2% of female soldiers in this subgroup met criteria for probable lifetime AUD; with 5.9% of males and 4.7% of females indicating that AUD symptoms were problematic during the past year. The higher prevalence of all forms of alcohol misuse among male soldiers is consistent with evidence from epidemiological surveys indicating that AUDs, binge drinking, and heavy drinking are more common among men than women (Grant et al., 2015, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

The limited available data on alcohol use of new military recruits suggest that the prevalence of lifetime binge drinking observed in our sample of incoming Army soldiers is similar to that of Naval recruits, 26% of whom endorsed “heavy drinking” – which was closest to our definition of Binge Drinking – during the year prior to basic training (Ames et al., 2002). A somewhat higher prevalence was observed in a study of Air Force recruits where 49% of the 78% of recruits who endorsed any alcohol use (i.e., ~38% of the total sample) endorsed binge drinking (Taylor et al., 2007). To our knowledge, other studies of military recruits have not estimated the prevalence of AUDs. However, the prevalence of probable past-year AUD in our restricted sample (5.7%) is similar to that observed in a recent study of Canadian Regular Military Forces Personnel (4.5%) (Rusu et al., 2016).

US-representative data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III (NESARC-III) indicate that the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month AUDs among 18- to 29-year olds is 37% and 27%, respectively (Grant et al., 2015), much higher than the respective estimates from our sample of new soldiers. This seems to indicate that the US Army's efforts to screen out individuals with AUD are, to some extent, successful. However, it should be noted that the NESARC-III comparison is not completely apt, as our estimates of AUD derive from a subsample of new soldiers with no or minimal lifetime use of other drugs. Other important differences between the two studies include the predominance of respondents from the younger end of the 18-29 age spectrum in our sample and differences in the setting (household vs. site of Army basic combat training) and modality (self-administered questionnaire vs. face-to-face interview) of assessment.

Irrespective of the above issues, our findings suggest that 1 of 8 soldiers enter Army service with a history of heavy drinking and – even among those with minimal lifetime drug use – 1 in 11 enter with probable lifetime AUD. This implies that the US army “inherits” an appreciable portion of its overall burden of alcohol misuse. However, the literature strongly suggests that more alcohol misuse emerges as soldiers progress in their careers. Data from the All-Army Study component of Army STARRS indicated that the majority of soldiers with 30-day SUD had post-enlistment onset (Kessler et al., 2014). Substantially higher prevalence of lifetime AUD is observed in surveys that include more experienced military personnel and veterans. AUDs were the most prevalent lifetime disorders among Ohio National Guard members (44%)(Fink et al., 2016a) and Canadian Regular Force members (32%)(Pearson et al., 2014). A contemporary survey of U.S. military veterans revealed that 42% had lifetime AUD and 15% had past-year AUD (Fuehrlein et al., 2016). Finally, there is evidence that deployments are associated with increased risk of new-onset AUDs (Jacobson et al., 2008). More prospective research on alcohol misuse among servicemembers is needed, including studies evaluating the impact of deployment stressors and other factors related to military experiences. We intend to study the longitudinal course of alcohol misuse in future work with the the Army STARRS cohorts.

Our psychiatric comorbidity data are consistent with other studies showing a strong association of PTSD with AUDs in US (Marshall et al., 2012) and UK (Head et al., 2016) military samples, and reveal that this association is also observed among Army recruits. Further analysis provided evidence for a bidirectional association between PTSD and AUD. Other studies of the temporal relationship of these disorders have yielded similar findings (Nickerson et al., 2014, Smith et al., 2014), which have been interpreted as supporting both “self-medication” and “substance-induced anxiety” models of PTSD and substance use disorder comorbidity. The particularly strong association of AUD with subsequent PTSD (AOR=3.15) in our analysis suggests assessment of alcohol misuse may be relevant to identifying soldiers at increased risk for PTSD following traumas incurred during military service.

Psychiatric comorbidity of AUD is by no means limited to PTSD, and associations of similar magnitude were observed between AUD and other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and suicidal ideation. These results converge with findings from the general US population, where AUDs display considerable comorbidity with both PTSD and other mental disorders (Grant et al., 2015). Consistent with recent findings in a sample of Ohio National Guard personnel (Fink et al., 2016b), we found that AUDs preceded as well as followed the onset of mental disorders and suicidal ideation. Although not all investigations have found bidirectional relationships between AUDs and mental disorders (Kuo et al., 2006), overall the available evidence suggests that interventions for AUD may help reduce the burden of other mental disorders, and vice versa. For patients with dual diagnosis, consideration should be given to treating both problems simultaneously (Roberts et al., 2015). These patients may benefit from management of comorbid conditions using disorder-specific psychotherapies with or without pharmacotherapy. For example, the psychotherapy Seeking Safety combined with a selective serotonin reuptake inihibtor yielded meaningful benefits for PTSD and AUD symptoms in veterans with both conditions (Hien et al., 2015). Additional research is needed to demonstrate the impact of treatments aimed not only at PTSD, but at the full range of comorbid mental disorders seen among military personnel with AUDs.

Finally, several non-psychiatric adverse outcomes were included in the analysis to illustrate other correlates of AUD that may have implications for screening and intervention. Among new Army soldiers, all types of alcohol misuse under consideration were associated with lifetime TBI and past-year MVAs. These findings are perhaps unsurprising given the known cognitive and motor effects of alcohol intoxication and the clustering of health-risk behaviors (Meader et al., 2016). Alcohol misuse – particularly heavy drinking – has previously been linked to serious adverse consequences (an outcome that included injuries and accidents) in military personnel (Mattiko et al., 2011). These results convey the broad impact of alcohol misuse and reinforce the importance of screening, prevention, and intervention efforts.

The current results must be interpreted in light of several important limitations. Evaluation of alcohol misuse, substance use, and mental disorders relied on retrospective self-report and is subject to response and recall biases. Respondents may have under-reported alcohol use and mental disorder symptoms, although this bias is typically reduced when confidential self-administration is employed as the mode of assessment (Kessler et al., 2013b). For soldiers who endorsed lifetime use of alcohol and other drugs, the survey did not establish whether reported abuse/dependence symptoms were due to alcohol use, drug use, or a combination of the two. Thus we were limited to examining prevalence and correlates of “probable AUD” among new soldiers with no or minimal lifetime use of other drugs. We applied a conservative exclusion criterion (resulting in exclusion of 12.5% of the overall sample) to increase confidence that cases of SUD remaining in the restricted sample were due entirely to alcohol misuse. A consequential tradeoff is that individuals with polysubstance use disorders – and even AUD accompanied by semi-regular use of other drugs – are not represented.

In summary, lifetime alcohol misuse is fairly common among new soldiers entering the US Army. Alcohol misuse ranging from lifetime binge drinking to past-year AUD is associated with an array of mental disorders and other adverse outcomes. Analyses incorporating age-of-onset indicate that AUDs are associated with increased odds of onset of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and suicidal ideation; and, conversely, that these same problems are associated with subsequent onset of AUD. The substantial associations of AUD with other mental health problems, which appear to be bidirectional in nature, must be considered in assessment and treatment planning. These associations also suggest that efforts to prevent alcohol misuse may decrease the future burden of not just AUD but other mental disorders; similarly, mental health promotion efforts may reduce adverse impacts of alcohol misuse. Conjoint recognition of problematic alcohol use and mental health problems upon a soldier's entry into the military provides a tremendous opportunity for intervention and risk mitigation, early in a soldier's military career.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) collaborating scientists: Lisa J. Colpe, PhD, MPH and Michael Schoenbaum, PhD; Army liaisons/consultants: COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH (USAPHC) and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC); Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); K. Nikki Benevides, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul D. Bliese, PhD (University of South Carolina); Susan Borja, PhD (NIMH); Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD (Stony Brook University School of Medicine); Gregory G. Brown, PhD (University of California San Diego); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Catherine L. Dempsey, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Stephen E. Gilman, ScD (Harvard School of Public Health); Marjan G. Holloway, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Karestan C. Koenen, PhD (Columbia University); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Rema Raman, PhD (University of California San Diego); Holly J. Ramsawh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Anthony Joseph Rosellini, PhD (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); LCDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Michaelle Scanlon, MBA (NIMH); Jordan W. Smoller, MD, ScD (Harvard Medical School); Amy Street, PhD (Boston University School of Medicine); Michael L. Thomas, PhD (University of California San Diego); Leming Wang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Christina L. Wassel, PhD (University of Pittsburgh); Simon Wessely, FMedSci (King's College London); Christina L. Wryter, BA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Hongyan Wu, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School). Kerry Ressler MD, PhD (Emory University) chaired the Scientific Advisory Board.

Funding

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under U01MH087981 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Ve terans Administration, Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Dr. Stein has in the past three years been a consultant for Healthcare Management Technologies, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Pfizer, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, Resilience Therapeutics, Tonix Pharmaceuticals, and Turing Pharmaceuticals. In the past three years, Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sanofi-Aventis Groupe. Dr. Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and U.S. Preventive Medicine. Dr. Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosure The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

References

- AMES GM, CUNRADI CB, MOORE RS. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use among young adults prior to entering the military. Prev Sci. 2002;3:135–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1015435401380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAY RM, BROWN JM, WILLIAMS J. Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:799–810. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEREFINKO KJ, KLESGES RC, BURSAC Z, LITTLE MA, HRYSHKO-MULLEN A, TALCOTT GW. Alcohol issues prior to training in the United States Air Force. Addict Behav. 2016;58:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFRON B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:414–425. [Google Scholar]

- FINK DS, CALABRESE JR, LIBERZON I, TAMBURRINO MB, CHAN P, COHEN GH, SAMPSON L, REED PL, SHIRLEY E, GOTO T, D'ARCANGELO N, FINE T, GALEA S. Retrospective age-of-onset and projected lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among U.S. Army National Guard soldiers. J Affect Disord. 2016a;202:171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINK DS, GALLAWAY MS, TAMBURRINO MB, LIBERZON I, CHAN P, COHEN GH, SAMPSON L, SHIRLEY E, GOTO T, D'ARCANGELO N, FINE T, REED PL, CALABRESE JR, GALEA S. Onset of Alcohol Use Disorders and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in a Military Cohort: Are there Critical Periods for Prevention of Alcohol Use Disorders? Prev Sci. 2016b;17:347–56. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUEHRLEIN BS, MOTA N, ARIAS AJ, TREVISAN LA, KACHADOURIAN LK, KRYSTAL JH, SOUTHWICK SM, PIETRZAK RH. The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addiction. 2016;111:1786–94. doi: 10.1111/add.13423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANT BF, GOLDSTEIN RB, SAHA TD, CHOU SP, JUNG J, ZHANG H, PICKERING RP, RUAN WJ, SMITH SM, HUANG B, HASIN DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–66. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEAD M, GOODWIN L, DEBELL F, GREENBERG N, WESSELY S, FEAR NT. Post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol misuse: comorbidity in UK military personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1171–80. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIEN DA, LEVIN FR, RUGLASS LM, LOPEZ-CASTRO T, PAPINI S, HU MC, COHEN LR, HERRON A. Combining seeking safety with sertraline for PTSD and alcohol use disorders: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:359–69. doi: 10.1037/a0038719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON IG, RYAN MA, HOOPER TI, SMITH TC, AMOROSO PJ, BOYKO EJ, GACKSTETTER GD, WELLS TS, BELL NS. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA. 2008;300:663–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, GEBLER N, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, STEIN MB, URSANO RJ, HEERINGA SG. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013a;22:267–75. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, HEERINGA SG, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, GEBLER N, HWANG I, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, STEIN MB, URSANO RJ. Response bias, weighting adjustments, and design effects in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013b;22:288–302. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, HEERINGA SG, STEIN MB, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, HWANG I, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, PETUKHOVA M, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, URSANO RJ, ARMY SC. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:504–13. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, SANTIAGO PN, COLPE LJ, DEMPSEY CL, FIRST MB, HEERINGA SG, STEIN MB, FULLERTON CS, GRUBER MJ, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, URSANO RJ. Clinical reappraisal of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013c;22:303–21. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, USTUN TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUO PH, GARDNER CO, KENDLER KS, PRESCOTT CA. The temporal relationship of the onsets of alcohol dependence and major depression: using a genetically informative study design. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1153–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUMLEY T. Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software. 2004;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- LUMLEY T. survey: analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 3. 2012:28–2. [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL BD, PRESCOTT MR, LIBERZON I, TAMBURRINO MB, CALABRESE JR, GALEA S. Coincident posttraumatic stress disorder and depression predict alcohol abuse during and after deployment among Army National Guard soldiers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASH HB, FULLERTON CS, RAMSAWH HJ, NG TH, WANG L, KESSLER RC, STEIN MB, URSANO RJ. Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with alcohol and energy drink use in the US Army. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1379–87. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTIKO MJ, OLMSTED KL, BROWN JM, BRAY RM. Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addict Behav. 2011;36:608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEADER N, KING K, MOE-BYRNE T, WRIGHT K, GRAHAM H, PETTICREW M, POWER C, WHITE M, SOWDEN AJ. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:657. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3373-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICKERSON A, BARNES JB, CREAMER M, FORBES D, MCFARLANE AC, O'DONNELL M, SILOVE D, STEEL Z, BRYANT RA. The temporal relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and problem alcohol use following traumatic injury. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:821–34. doi: 10.1037/a0037920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOCK MK, URSANO RJ, HEERINGA SG, STEIN MB, JAIN S, RAMAN R, SUN X, CHIU WT, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, GILMAN SE, HWANG I, NAIFEH JA, ROSELLINI AJ, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, KESSLER RC, THE ARMY SC. Mental Disorders, Comorbidity, and Pre-enlistment Suicidal Behavior Among New Soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON C, ZAMORSKI M, JANZ T. “Mental health of the Canadian Armed Forces” Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- POSNER K, BROWN GK, STANLEY B, BRENT DA, YERSHOVA KV, OQUENDO MA, CURRIER GW, MELVIN GA, GREENHILL L, SHEN S, MANN JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R CORE TEAM . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS NP, ROBERTS PA, JONES N, BISSON JI. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSELLINI AJ, HEERINGA SG, STEIN MB, URSANO RJ, CHIU WT, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, GILMAN SE, HWANG I, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, PETUKHOVA M, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, KESSLER RC. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:13–24. doi: 10.1002/da.22316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSU C, ZAMORSKI MA, BOULOS D, GARBER BG. Prevalence Comparison of Past-year Mental Disorders and Suicidal Behaviours in the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian General Population. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:46S–55S. doi: 10.1177/0706743716628856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON L, COHEN GH, CALABRESE JR, FINK DS, TAMBURRINO M, LIBERZON I, CHAN P, GALEA S. Mental Health Over Time in a Military Sample: The Impact of Alcohol Use Disorder on Trajectories of Psychopathology After Deployment. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:547–55. doi: 10.1002/jts.22055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGER JD, WILLETT JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis : modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH TC, LEARDMANN CA, SMITH B, JACOBSON IG, MILLER SC, WELLS TS, BOYKO EJ, RYAN MA. Longitudinal assessment of mental disorders, smoking, and hazardous drinking among a population-based cohort of US service members. J Addict Med. 2014;8:271–81. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN MB, KESSLER RC, HEERINGA SG, JAIN S, CAMPBELL-SILLS L, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, NOCK MK, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, SUN X, THOMAS ML, URSANO RJ, ARMY SC. Prospective longitudinal evaluation of the effect of deployment-acquired traumatic brain injury on posttraumatic stress and related disorders: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:1101–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION [September 12 2016];National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Table 5.8B—Substance dependence or abuse in the past year among persons aged 18 or older, by demographic characteristics: Percentages, 2013 and 2014. 2014 [Online]. Available: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2014/NSDUHDetTabs2014.htm#tab5-8b.

- TAYLOR JE, HADDOCK K, POSTON WS, TALCOTT WG. Relationship between patterns of alcohol use and negative alcohol-related outcomes among U.S. Air Force recruits. Mil Med. 2007;172:379–82. doi: 10.7205/milmed.172.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URSANO RJ, COLPE LJ, HEERINGA SG, KESSLER RC, SCHOENBAUM M, STEIN MB, ARMY SC. The Army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 2014;77:107–19. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URSANO RJ, HEERINGA SG, STEIN MB, JAIN S, RAMAN R, SUN X, CHIU WT, COLPE LJ, FULLERTON CS, GILMAN SE, HWANG I, NAIFEH JA, NOCK MK, ROSELLINI AJ, SAMPSON NA, SCHOENBAUM M, ZASLAVSKY AM, KESSLER RC. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:3–12. doi: 10.1002/da.22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLER M, MCGUIRE AC, DOBSON AJ. Alcohol use in the military: associations with health and wellbeing. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10:27. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITEFORD HA, DEGENHARDT L, REHM J, BAXTER AJ, FERRARI AJ, ERSKINE HE, CHARLSON FJ, NORMAN RE, FLAXMAN AD, JOHNS N, BURSTEIN R, MURRAY CJ, VOS T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.