Abstract

Objective

Despite evidence for the validity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and its recent inclusion in DSM-5, variable diagnostic practices compromise the construct validity of the diagnosis and threaten the clarity of efforts to understand and treat its underlying pathophysiology. In an effort to hasten and streamline the translation of the new DSM-5 criteria for PMDD into terms compatible with existing research practices, we present the development and initial validation of the Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS). The C-PASS is a standardized scoring system for making DSM-5 PMDD diagnoses using 2 or more menstrual cycles of daily symptom ratings using the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP).

Method

Two hundred women recruited for retrospectively-reported premenstrual emotional symptoms provided 2–4 menstrual cycles of daily symptom ratings on the DRSP. Diagnoses were made by expert clinician and the C-PASS.

Results

Agreement of C-PASS diagnosis with expert clinical diagnosis was excellent; overall correct classification by the C-PASS was estimated at 98%. Consistent with previous evidence, retrospective reports of premenstrual symptom increases were a poor predictor of prospective C-PASS diagnosis.

Conclusions

The C-PASS (available as a worksheet, Excel macro, and SAS macro) is a reliable and valid companion protocol to the DRSP that standardizes and streamlines the complex, multilevel diagnosis of DSM-5 PMDD. Consistent use of this robust diagnostic method would result in more clearly-defined, homogeneous samples of women with PMDD, thereby improving the clarity of studies seeking to characterize or treat the underlying pathophysiology of the disorder.

Keywords: Premenstrual Syndrome, Diagnosis and Classification, Computers, Psychometrics

Introduction

Diagnostic Issues in Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

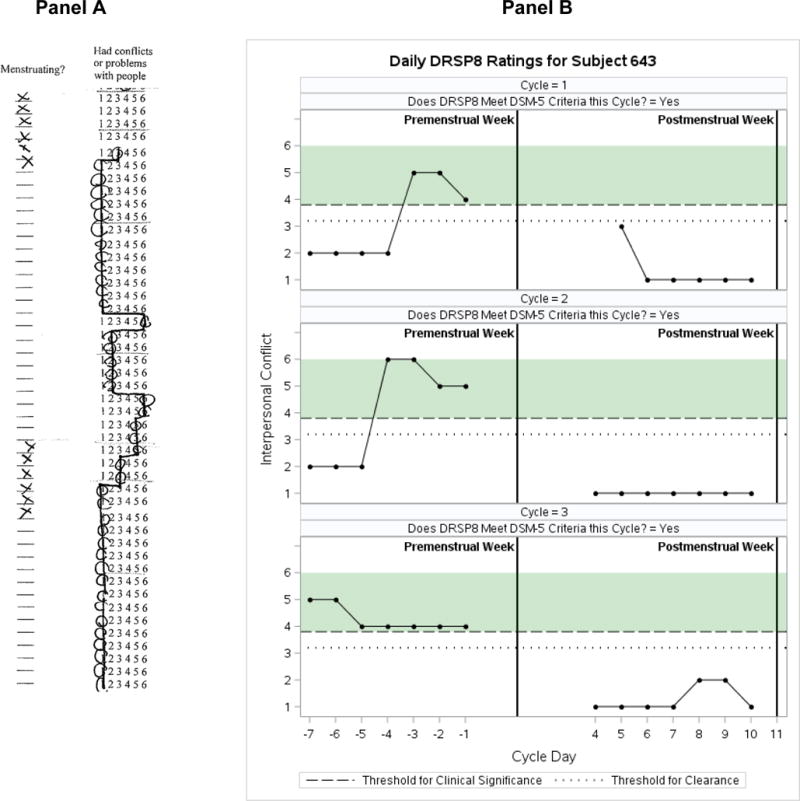

Characterized by the emergence of emotional symptoms in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) causes severe distress and impairment among the estimated 3–8% of women meeting DSM-5 criteria1,2. Another 10–11% of women show evidence of a menstrually-related mood disorder (MRMD) causing distress and impairment sufficient to warrant treatment despite failure to meet full DSM-5 criteria2. Due to the poor prospective validity of retrospectively-reported premenstrual symptoms, valid diagnosis requires evaluation of prospective daily symptom ratings3. In research settings, diagnosis is often made by visual inspection of daily symptom ratings7 (see Figure 1, Panel A). However, laboratories differ in the specific manner that daily ratings are translated into diagnostic decisions8,9, and the complex, multilevel nature of the diagnosis suggests high risk of diagnostician error. These issues motivated development of the Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS), a standardized, computerized procedure for the reliable prospective diagnosis of DSM-5 PMDD.

Figure 1.

Typical Visualization of DRSP Daily Symptom Ratings Across Two Cycles (Panel A) vs. C-PASS Visualization of DRSP Daily Symptom Ratings Across Three Cycles (produced by the SAS C-PASS Macro; Panel B)

The Complex, Multilevel Diagnosis of PMDD

DSM-5 PMDD is multifaceted and multilevel, requiring many conditions to be met (i.e., content, cyclicity, severity, and chronicity) at various levels (i.e., symptoms, cycles, women). DSM-5 symptoms and their overlap with the items of the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP)4, the most widely used daily symptom scale, are listed in Table 1. Table 2 outlines our conceptualization of DSM-5 diagnostic dimensions, including: (1) the content dimension, referring to the nature and number of symptoms; five symptoms must be present, of which one must be a core emotional symptom, (2) the cyclicity dimension, referring to both relative premenstrual elevation (“premenstrual change”) and absolute postmenstrual clearance of symptoms, describes the premenstrual onset and postmenstrual offset of symptoms in the perimenstrual timeframe5, (3) the clinical significance dimension, dictating that symptoms must be of sufficient absolute premenstrual severity and premenstrual duration as to cause clinically significant distress or impairment, and (4) the chronicity dimension, requiring symptoms to be present in the majority of months.

Table 1.

Mapping the Items of the DRSP onto DSM-5 Diagnostic Content

| DRSP ITEMS | DSM-5 PMDD CONTENT |

|---|---|

| CORE SYMPTOMS/CRITERION B | |

| DRSP 5. Had mood swings (e.g. suddenly felt sad or tearful) | 1. Marked affective lability (e.g., mood swings; feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection) |

| DRSP 6. Was more sensitive to rejection or my feelings were easily hurt | |

| DRSP 7. Felt angry, irritable | 2. Marked irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts |

| DRSP 8. Had conflicts or problems with people | |

| DRSP 1. Felt depressed, sad, “down” or blue | 3. Marked depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts |

| DRSP 2. Felt hopeless | |

| DRSP 3. Felt worthless or guilty | |

| DRSP 4. Felt anxious, “keyed up”, or “on edge” | 4. Marked anxiety, tension, and/or feelings of being keyed up or on edge |

| ADDITIONAL SYMPTOMS/CRITERION C | |

| DRSP 9. Had less interest in usual activities (e.g. work, school, friends, hobbies) | 1. Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g. work, school, friends, hobbies) |

| DRSP 10. Had difficulty concentrating | 2. Subjective difficulty in concentration |

| DRSP 11. Felt lethargic tired, fatigued, or had a lack of energy | 3. Lethargy, easy fatigability, or marked lack of energy |

| DRSP 12. Had increased appetite or overate | 4. Marked change in appetite; overeating; or specific food cravings |

| DRSP 13. Had specific food cravings | |

| DRSP 14. Slept more, took naps, found it hard to get up | 5. Hypersomnia or Insomnia |

| DRSP 15. Had trouble getting to sleep, staying asleep | |

| DRSP 16. Felt overwhelmed, that I couldn’t cope | 6. A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control |

| DRSP 17. Felt out of control | |

| DRSP 18. Had breast tenderness | 7. Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, sensation of “bloating”, or weight gain |

| DRSP 19. Had breast swelling, felt bloated, or had weight gain | |

| DRSP 21. Had Joint or muscle pain | |

| DRSP 20. Had headache | |

Table 2.

Diagnostic Dimensions of DSM-5 Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

| DIAGNOSTIC DIMENSIONS | Diagnosis Based on DRSP | DSM-5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Symptoms |

Core symptoms: felt depressed/sad/down/blue, felt hopeless, felt worthless/guilty, felt anxious/keyed up/on edge, had mood swings, was more sensitive to rejection/feelings were easily hurt, felt angry/irritable, had conflicts/problems with other people Secondary symptoms: less interest in usual activities, difficulty concentrating, lethargic/fatigue/tired/lack of energy, increased appetite/overate, specific food cravings, slept more/took naps/hard to get up, trouble getting to sleep/staying asleep, felt overwhelmed/couldn’t cope, felt out of control, breast tenderness, breast swelling/felt bloated/weight gain, headache, joint or muscle pain Impairment symptoms: “Less productivity at work, school, home or in daily routine” “Interference with hobbies or social activities (avoid, do less)” “Interference with relationships” |

Criterion B: affective lability, irritability/anger/increased interpersonal conflicts, depressed mood/feelings of hopelessness/self-deprecating thoughts, anxiety/tension/feelings of being keyed up/on edge Criterion C: decreased interest, difficulty in concentration, lethargy/easy fatigability/lack of energy, change in appetite, hypersomnia/insomnia, overwhelmed/out of control, physical symptoms (breast tenderness, muscle pain, bloating, weight gain) |

|

| Number | NON-PMDD MRMD ≥ 1 core symptom |

PMDD ≥ 1 core symptom ≥ 5 total symptoms |

Criterion A: A total of 5 [at least (one or more) of each subgroup] |

|

| Cyclicity | Relative Premenstrual Elevation | 30% (relative to range of scale used) decrease from pre-menstrual week (days −7 → −1) to postmenstrual week (days 4 → 10) where −1 is the day prior to menstrual onse and 1 is menstrual onset |

Criterion A: “…present in the week before menses…improve within a few days after the onset of menses” |

|

| Absolute Postmenstrual Clearance | Symptoms must not exceed a value of 3 on any day during days 4 → 10 |

Criterion A: “minimal or absent in the week postmenses” Postmenses = following menstrual onset |

||

| Clinical Significance | Absolute Premenstrual Severity | 4 or more (on a Likert-scale from 1 to 6) |

Criterion D: “symptoms are associated with clinically significant distress OR interference with work, school, usual social activities, or relationships with others” |

|

| Premenstrual Duration | At least 2 days (doesn’t have to be consecutive) |

Criterion D: “in the final week before the onset of menses” |

||

| Not Simply Cyclicity of Other Disorder | Rule out dysmenorrhea using prospective ratings. Rule out mood and anxiety disorder with SCID-1. Rule out Borderline Personality Disorder with SCID-2. |

Criterion E: “not merely an exacerbation of the symptoms of another disorder.” “Key differential diagnoses: dysmenorrhea, bipolar disorder, MDD, dysthymia, and BPD.” |

||

| Chronicity | ≥ 2 symptomatic months |

Criterion A and F: “In the majority of menstrual cycles…” “…should be confirmed by prospective daily ratings during at least two symptomatic cycles.” |

||

Translating DSM-5 Dimensions into Standardized Thresholds for the DRSP

The DRSP4 measures all 11 DSM-5 PMDD symptoms. Women rate daily symptoms on a 6-point scale from 1–Not at all to 6–Extreme. This allows for evaluation of symptom dimensions described above; however, DSM-5 does not give numeric thresholds for most dimensions, leading to variability in thresholds used across laboratories. Although the field has made some strides in standardizing diagnosis6, at least two key inconsistencies remain. First, the DSM-5 requirement of “severe” premenstrual symptoms (absolute severity) and “minimal or absent” postmenstrual symptoms (absolute clearance) is subjective, and different studies set this threshold for clinical significance of symptoms at different ratings on the DRSP7. The developers of the DRSP suggest that the most liberal acceptable delineation of “clinically significant” symptoms would be at greater than or equal to 4 (“moderate”)4. In order to reduce the risk of diagnosing normal affective experiences as a mental disorder8–10, we recommend that this cutoff of “4-moderate” be implemented consistently as the threshold for absolute severity (premenstrual symptoms must reach 4) and absolute symptom clearance (postmenstrual symptoms must not exceed 3). Second, although 30% premenstrual elevation (or premenstrual “change”) is generally used5,11 as the elevation threshold, at least five different methods have been used to calculate this premenstrual change variable (listed in Table 3 note)18,19,20,7,12,13. Therefore, the present study begins by examining the interactive effects of both differing calculation methods and differing thresholds on diagnostic prevalence.

Table 3.

Comparing the Prevalence Impact of Various Methods and Thresholds for Determining Significant Premenstrual Symptom Elevations

| Frequency of C-PASS Diagnosis by Cyclicity Calculation Method (N=200) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% Threshold |

50% Threshold |

75% Threshold |

1 SD Threshold |

|||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||

| Method 11: Relative to a Woman’s Postmenstrual Average for this Symptom in this Cycle | ||||||||||||

| No Diagnosis | 93 | 46% | 96 | 48% | 105 | 53% | N/A | |||||

| NON-PMDD MRMD | 54 | 27% | 53 | 27% | 47 | 23% | N/A | |||||

| DSM-5 PMDD | 53 | 27% | 51 | 25% | 48 | 24% | N/A | |||||

| Method 22: Relative to a Woman’s Range of Scale Used Across All Symptoms and Cycles | ||||||||||||

| No Diagnosis | 116 | 58% | 164 | 82% | 193 | 97% | N/A | |||||

| NON-PMDD MRMD | 46 | 23% | 21 | 11% | 5 | 2% | N/A | |||||

| DSM-5 PMDD | 38 | 19% | 15 | 7% | 2 | 1% | N/A | |||||

| Method 33: Relative to Full Range of Scale (fixed at 5) | ||||||||||||

| No Diagnosis | 120 | 60% | 170 | 85% | 193 | 97% | N/A | |||||

| NON-PMDD MRMD | 44 | 22% | 16 | 8% | 5 | 2% | N/A | |||||

| DSM-5 PMDD | 36 | 18% | 14 | 7% | 2 | 1% | N/A | |||||

| Method 44: Relative to a Woman’s Premenstrual Average for this Symptom in this Cycle | ||||||||||||

| No Diagnosis | 95 | 48% | 111 | 56% | 189 | 95% | N/A | |||||

| NON-PMDD MRMD | 54 | 27% | 46 | 23% | 4 | 2% | N/A | |||||

| DSM-5 PMDD | 51 | 25% | 43 | 21% | 7 | 3% | N/A | |||||

| Method 55: Relative to a Woman’s Standard Deviation for this Symptom in this Cycle | ||||||||||||

| No Diagnosis | N/A | N/A | N/A | 105 | 54% | |||||||

| NON-PMDD MRMD | N/A | N/A | N/A | 50 | 25% | |||||||

| DSM-5 PMDD | N/A | N/A | N/A | 41 | 21% | |||||||

(Premenstrual Mean − Postmenstrual Mean)/Postmenstrual Mean (this symptom, this cycle)

(Premenstrual Mean − Postmenstrual Mean)/(Person’s Maximum Rating Ever Used − 1).

(Premenstrual Mean − Postmenstrual Mean)/5.

(Premenstrual Mean − Postmenstrual Mean)/Premenstrual Mean (this symptom, this cycle)

(Premenstrual Mean − Postmenstrual Mean)/Standard Deviation (this symptom, this cycle)

The Benefits of Computerizing Diagnosis

Even with validated numeric thresholds, many factors may limit the reliability of PMDD diagnoses made using visual inspection, making computerized diagnosis preferable. First, although it is possible to evaluate many of the diagnostic dimensions by simple visual inspection of daily ratings, premenstrual symptom elevation relative to one’s postmenstrual (follicular) symptoms—the most discriminating feature of PMDD11—must be calculated for each symptom in each cycle. Second, validated numeric criteria have limited clinical utility if a clinician must calculate and concatenate the diagnostic dimensions “by hand” at symptom, cycle, and person levels across 1700 daily ratings (i.e., 3 months). Third, visual inspection of ratings across the entire cycle requires that the diagnostician ignore a great deal of distracting information that is not central to the diagnosis of PMDD. Finally, common errors of clinical judgment such as the tendency to ignore base rates (which in this case are low; 3–8% with PMDD and an additional 10–11% with non-PMDD MRMD2,14) or assign too much importance to easily accessible information (e.g., absolute premenstrual symptom severity vs. the more complicated relative premenstrual symptom elevation) may introduce diagnostic error10–12. Therefore, although valid diagnosis of PMDD is possible using simple visual inspection4, poor reliability of such visual diagnosis is likely due to busy clinician schedules and sources of unconscious error. It is this state of affairs that motivated our development of a computerized approach13 to making the complex diagnosis of PMDD.

Goals of the Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS)

This paper describes development of the C-PASS in a sample of 200 women seeking diagnosis with PMDD. We had four goals. First, by providing this standardized scoring system, we aim to promote the reliability—and, by extension, the construct validity—of the PMDD diagnosis by eliminating diagnostician variability and error. Given the important sociocultural considerations raised around the DSM-5 diagnosis, we feel that a move toward diagnostic specificity and reliability is critical8–10. Second, C-PASS data output provides dimensional variables for each woman, with the goal of promoting the dimensional (vs. categorical) study of premenstrual dysphoria. Third, C-PASS visual output maximizes attention to central diagnostic information (see Figure 1, Panel B), with the goal of integrating the benefits of visual inspection with the reliability of computerization. Fourth, the C-PASS aims to improve the clarity of pathophysiological studies of PMDD by permitting more homogeneous clinical samples.

Methods

Description of the C-PASS Diagnostic Method

The C-PASS SAS Macro, Excel Macro, and worksheet are available at http://www.toryeisenlohrmoul.com/cpass. The macro code was developed using a double-coding technique by authors TAEM and JJ. The diagnostic process begins by characterizing each DRSP item in each cycle (where a cycle is defined as a set of contiguous premenstrual and postmenstrual weeks from consecutive cycles) using the four diagnostic dimensions as described in Table 2 (relative symptom elevation: percent symptom elevation during premenstrual week relative to the postmenstrual week >=30%; see Table 3, Method 2; absolute clearance: postmenstrual week maximum <=3; absolute severity: premenstrual week maximum >=4; and duration: severe premenstrual week days >=2). Because DSM-5 PMDD is defined as a marked on-off pattern occurring in the perimenstrual timeframe, the C-PASS utilizes the premenstrual week (defined as days −7 to −1, where −1 is the day prior to menstrual onset) and the postmenstrual week (defined as the 7 days following average menstrual offset: days 4 to 10, where day 1 represents menstrual onset). That is, the rationale for comparing the premenstrual week of one menstrual cycle to the contiguous postmenstrual week of the next cycle is to establish the “switch off” of symptoms, as it is critical to demonstrate that the cyclical symptoms do not persist into the follicular phase. Further, the C-PASS requires that at least 3 out of 7 ratings be present in each of the two weeks, and requires two cycles (i.e., perimenstrual frames).

While the DSM-IV research diagnosis of PMDD required premenstrual impairment, the DSM-5 no longer does. Therefore, the interference items on the DRSP are not included in the C-PASS, although information about the cyclicity and clinical significance of life interference items from the DRSP can be examined as secondary outcomes.

Next, cycle-level diagnosis of PMDD is made by counting DSM-5 symptoms meeting criteria on all four dimensions (Table 2; Total Symptoms: 1–4 for MRMD and >=5 for PMDD) and whether a core symptom meets criteria (number of core symptoms >=1). Next, MRMD or PMDD diagnosis is made at the person level by counting the number of cycles meeting MRMD and PMDD criteria (cycles meeting criteria >=2). Finally, the C-PASS creates a visual representation of relevant information for each DRSP item across as many cycles as provided (see Figure 1, Panel B), along with a determination of cycle-level diagnosis for that symptom in each cycle. The system also outputs a dataset with person-level summary variables for each symptom on each diagnostic dimension. In the present study, the more common research diagnosis of MRMD5 (i.e., 1–4 symptoms met for at least 2 cycles, of which one must be a core emotional symptom) was also calculated. Although the C-PASS diagnosis is designed to be made by a computer, a worksheet in the supplemental materials allows for manual replication of C-PASS diagnoses.

Participants, Procedure, and Materials

Between 2009–2015, naturally cycling women aged 18–47 (M = 32.70, SD = 8.21) with regular cycles (21–35 days) were recruited through flyers and emails seeking women with premenstrual emotional symptoms. Women were excluded for chronic medical disorders; histories of mania, substance dependence, or psychosis; any current SCID-I diagnosis; and certain medications (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, or hormonal preparations). Participants were not paid. At a baseline visit, participants reported their medical and medication history and completed the SCID-I15. Participants retrospectively reported the degree of premenstrual increase in each of 21 symptoms16 on a 4-point Likert scale from 1–No change to 4–Severe change (α = .91). Two hundred sixty-seven eligible women completed prospective assessment.

Prospective assessment included 2–4 cycles of daily DRSP ratings. Participants noted daily events they believed to have impacted daily mood; days in which participants reported the occurrence of a severe stressor not caused by symptoms were coded as missing. Participants mailed in forms weekly. In the final sample, 200 women provided at least two cycles. Eighty-five percent of women who dropped out after 1 cycle had not met C-PASS PMDD criteria in the first cycle. In women with >= 2 cycles, missing days were minimal (3.4%); just 1% of daily data were missing due to external events. Expert diagnoses (coauthor DR) of MRMD made prior to the development of the C-PASS (on the basis of identical data) were available for the majority of our sample (193 women; 96.5%). Because the DRSP summed total score demonstrates inadequate reliability of change17, descriptive statistics for single items are considered.

Results

At least five equations are used in the existing literature to calculate relative premenstrual symptom elevation, and several thresholds for diagnosis are proposed (30%, 50%, and 75%). With [pre-menstrual week average – post-menstrual week average] as the constant numerator, the five calculation methods differ in the denominator used: (1) post-menstrual average (denominator: postmenstrual week average), varying by cycle, (2), range of scale used across all ratings (denominator: woman’s maximum rating-1), varying by woman, (3) full scale range (fixed denominator: 5), (4) premenstrual average (denominator: premenstrual week average), varying by cycle, and (5) standard deviation (denominator: standard deviation of this symptom in this cycle for this woman), varying by symptom and cycle. Of note, the standard deviation method utilizes a constant one-standard-deviation threshold. In Table 3, we examine the combined impact of these five calculation methods and three thresholds on diagnostic prevalence.

Calculation method and threshold used to define significant relative symptom elevation had a large impact on diagnostic prevalence (see Table 3). The follicular mean method consistently proved to be the most liberal, resulting in much higher average relative premenstrual elevation values (p < .0001 for all method-wise comparisons) and the highest prevalence rates. The premenstrual mean and standard deviation methods appeared slightly more conservative, while the range of scale used and full scale methods appeared most conservative. Increasing % thresholds reduced diagnostic prevalence, particularly when using full range and range of scale used methods. For the C-PASS protocol, we selected the range of scale used method paired with a 30% threshold. This method produced prevalence rates consistent with previous epidemiological studies18 assuming that rates of diagnosis should be higher in this sample of women seeking to participate in a study of premenstrual affective symptoms. Additionally, this method maximizes generalizability of results to women who may not use the full DRSP response scale. In the context of the range of scale used method, a threshold of 30% was selected on the basis of highest agreement with expert diagnosis (94.3% agreement using the 30% threshold; 34% agreement using 50% threshold, 12% agreement using the 75% threshold).

Once the protocol was finalized, we used the C-PASS to identify three diagnostic groups (No Diagnosis: n=116, 58%; Non-PMDD MRMD: n=46, 23%; DSM-5 PMDD: n=38, 19%). Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for diagnostic dimensions by group.

Table 4.

Descriptive Information for C-PASS Diagnostic Groups on Dimensions of DSM-5 PMDD

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Dimensions | Outcome | C-PASS Diagnosis

|

||||||

| No Dx (n = 116) |

NON-PMDD MRMD (n = 46) |

PMDD (n = 38) |

||||||

|

| ||||||||

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |||

| Content | Number of Symptoms Meeting Criteria | Avg Total # of DSM-5 Sx | .68 | (.72) | 2.24 | (.92) | 4.60 | (1.07) |

| Avg # of Psychological DRSP Items | 1.24 | (2.04) | 2.78 | (1.54) | 7.09 | (2.59) | ||

| Avg # of Somatic DRSP Items | .99 | (1.35) | 1.76 | (1.37) | 4.53 | (1.98) | ||

| Cyclicity Dimensions | Relative Pre-menstrual Symptom Elevation | Avg % Elevation – Depression | 10% | (18) | 21% | (13) | 40% | (19) |

| Avg % Elevation – Anxiety | 13% | (20) | 30% | (17) | 48% | (20) | ||

| Avg % Elevation – Anger | 18% | (20) | 34% | (17) | 53% | (16) | ||

| Avg % Elevation – Mood Lability | 15% | (20) | 29% | (18) | 48% | (18) | ||

| Avg % Elevation – Somatic Sx | 17% | (22) | 27% | (21) | 50% | (24) | ||

| Avg % Elevation – Relationship Int. | 12% | (19) | 23% | (17) | 43% | (18) | ||

| Avg % Elevation – Work Int. | 9% | (21) | 21% | (18) | 41% | (22) | ||

| Absolute Post-menstrual Symptom Clearance | Avg Postmenstrual Max – Depression | 2.38 | (1.33) | 2.24 | (1.10) | 2.21 | (.84) | |

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Anxiety | 2.60 | (1.31) | 2.43 | (1.05) | 2.24 | (.77) | ||

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Anger | 2.62 | (1.35) | 2.44 | (1.04) | 2.20 | (.84) | ||

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Mood Lab. | 2.44 | (1.38) | 2.42 | (1.19) | 2.10 | (.90) | ||

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Somatic Sx | 2.13 | (1.34) | 2.04 | (1.03) | 1.74 | (.86) | ||

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Rel. Int. | 2.08 | (1.36) | 2.08 | (1.18) | 1.79 | (.88) | ||

| Avg Postmenstrual Max – Work Int. | 2.32 | (1.38) | 2.30 | (1.21) | 1.78 | (.72) | ||

| Clinical Significance Dimensions | Absolute Pre-menstrual Severity | Avg Premenstrual Max – Depression | 3.11 | (1.37) | 3.63 | (1.24) | 4.67 | (1.05) |

| Avg Premenstrual Max – Anxiety | 3.45 | (1.39) | 4.11 | (1.17) | 4.92 | (1.03) | ||

| Avg Premenstrual Max – Anger | 3.80 | (1.38) | 4.34 | (.98) | 5.36 | (.69) | ||

| Avg Premenstrual Max – Mood Lab. | 3.48 | (1.40) | 4.28 | (1.03) | 5.10 | (.75) | ||

| Avg Premenstrual – Somatic Sx | 3.13 | (1.50) | 3.60 | (1.33) | 4.60 | (1.37) | ||

| Avg Premenstrual Max – Rel. Int. | 3.01 | (1.58) | 3.70 | (1.48) | 4.72 | (1.09) | ||

| Avg Premenstrual Max – Work Int. | 2.95 | (1.42) | 3.69 | (1.27) | 4.43 | (1.22) | ||

| Pre-menstrual Duration | Avg Severe Days – Depression | .94 | (1.28) | 1.43 | (1.55) | 3.36 | (1.95) | |

| Avg Severe Days – Anxiety | 1.44 | (1.40) | 2.32 | (1.61) | 4.23 | (1.91) | ||

| Avg Severe Days – Anger | 1.59 | (1.50) | 2.77 | (1.62) | 4.52 | (1.56) | ||

| Avg Severe Days – Mood Lability | 1.24 | (1.30) | 2.33 | (1.55) | 4.06 | (1.81) | ||

| Avg Severe Days – Somatic Sx | 1.89 | (1.55) | 2.00 | (1.89) | 3.99 | (2.36) | ||

| Avg Severe Days – Relationship Int. | 1.53 | (1.37) | 1.59 | (1.51) | 3.23 | (1.79) | ||

| Avg Severe Days – Work Int. | 1.67 | (1.16) | 1.59 | (1.55) | 3.00 | (2.06) | ||

Note. Depression was measured using DRSP item 1. Anxiety was measured using DRSP item 4. Mood Lability was measured using DRSP item 5. Somatic Symptoms were measured using the average of DRSP items 18, 19, and 21. Relationship Interference was measured using DRSP item 24. Work Interference was measured using DRSP item 22.

Criterion Validity: Comparing C-PASS Diagnosis to Expert Diagnosis

Comparison of CPASS decisions (MRMD vs. no MRMD) to expert diagnosis revealed 94.3% agreement (11 disagreements). Inspection of ratings and clinical notes revealed three reasons for disagreement, each of which are instructive as to either the usefulness of the C-PASS or ways to improve the C-PASS moving forward.

In four cases, women were diagnosed by the C-PASS that were not diagnosed by expert clinician due to persistent background symptoms. Upon inspection of the raw data, the C-PASS had identified repeating cyclical patterns of anxiety (in 2 women) or interpersonal rejection sensitivity and anger (in 2 women). Of note, the DSM-5 does allow PMDD diagnosis to be made in such a case, so long as this pattern of symptoms does not represent an exacerbation of an underlying mood disorder, which were exclusionary in this study. Given (1) the clear evidence of repeating premenstrual elevations and postmenstrual declines on these symptoms and (2) the absence of Axis 1 disorder, we believe that the C-PASS decision for these women is accurate.

In three additional cases, women with insufficient premenstrual symptom severity (symptoms failed to reach a rating of “4–Moderate” in the premenstrual phase) or duration (less than two premenstrual days of at least moderate symptoms) were diagnosed with MRMD by the visual inspection that were not diagnosed by the C-PASS. Although these women showed genuine symptom cyclicity, they fail to meet the a priori definition of a mental disorder, and we feel that the C-PASS decision is accurate.

In the remaining four cases, women with “late” menstrual clearance of symptoms (symptoms persisting through the end of menses) were accurately diagnosed by expert clinician, whereas the C-PASS, which evaluates symptom clearance during days 4 to 10, failed to diagnose these women because it judged that symptoms had not cleared adequately. We feel that the expert clinician was correct in these cases, and this provides an important area for improving the C-PASS. In a future study (for which data collection is underway), we will evaluate differences between (1) diagnosis made based on standardized days 4 to 10, and (2) diagnosis made based on an individualized last day of menses +7 days. Although the latter may seem the intuitive choice, the former may have the benefit of greater biological validity, as the start of menstrual bleeding is a less ambiguous stimulus to self-report than the end of menses. In sum, we feel that the C-PASS mistakenly failed to diagnose just 4 women (2% of sample).

Comparison of Retrospective Premenstrual Symptoms to C-PASS Diagnosis

Consistent with previous reports16, logistic regression revealed that retrospectively-reported premenstrual symptom change was a very poor predictor of both C-PASS MRMD diagnosis (Standardized B = .038, SE = .011, X2 = 11.46, p = .0007, OR for a 1 SD increase in retrospective symptoms = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.06) and C-PASS PMDD diagnosis (Standardized B = .061, SE = .016, X2 = 14.01, p = .0002, OR for a 1 SD increase in retrospective symptoms = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.09). Given this poor predictive validity of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms, attempts to identify a reasonably sensitive and specific cutoff value for the prediction of C-PASS diagnoses were unsuccessful (AUC for MRMD Diagnosis= .63, 95% CI: .56 to .70; AUC for PMDD Diagnosis = .70, 95% CI: .62 to .78).

Discussion

Despite evidence for the existence and burden of PMDD6, inconsistent diagnostic practices compromise the construct validity of PMDD10, undermine accurate clinical diagnosis19, and threaten the clarity of efforts to characterize the pathophysiology of the disorder. In an effort to hasten and standardize the translation of the DSM-5 PMDD criteria into terms compatible with existing research practices, the present paper presents the Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS), a scoring system for prospective ratings on the DRSP that can be used either manually or with macro programs for SAS and Excel.

The present paper also draws attention to and resolves an egregious mathematical inconsistency in the existing literature: the use of at least five different equations for calculating the degree of premenstrual symptom elevation relative to baseline (also referred to as “premenstrual change”) has likely introduced unacceptable between-laboratory variability in the meaning of MRMD/PMDD across laboratories. In light of the present findings, we recommend that the range of scale used method (Table 3) be utilized in combination with a 30% threshold. Regardless of methods used, both calculation equations and thresholds should always be explicitly described. This represents a crucial step toward replicability of findings.

The present work holds the potential to increase the reliability of PMDD diagnosis; however, additional work should further examine the validity of the diagnostic thresholds used in the C-PASS, especially the number of symptoms per cycle that best defines a group of women in need of diagnosis and treatment. Of note, the dimensions of PMDD diagnosis were normally distributed; ultimately, PMDD may be best conceptualized in a continuous, dimensional manner that could be described more precisely in future iterations of the DSM (“unisymptom” vs. “multisymptom”; or “with rapid offset” vs. “with gradual offset”). Relatedly, future research must determine whether MRMD and PMDD arise from normally-distributed risk processes related to those described in the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDoC)20,21 framework, or whether there are more categorical pathophysiological processes at play.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study are noteworthy: First, because the C-PASS is designed to identify premenstrual symptoms of a clinically significant nature, it may therefore fail to identify women who demonstrate significant menstrual-cycle entrainment of symptoms that are not premenstrual (e.g., at midcycle), or those who do not show sufficient absolute severity or clearance. Second, because the C-PASS seeks to balance efficiency with reliability, it does not consider mid-cycle symptoms; if significant late follicular symptoms are present, this may signal the need for differential diagnosis. Third, the C-PASS is developed for the DRSP, given that this scale assesses all DSM-5 content; however, other useful rating scales for PMDD exist (e.g., the Daily Symptom Record24). Limitations of the DRSP, such as scale sensitivity (i.e., relative to a 100mm scale) and unbalanced content coverage should be addressed. Fourth, the C-PASS may fail to accurately diagnose some women with late symptom clearance; future work should determine whether self-reported menstrual offset is sufficiently accurate to permit the use of personalized postmenstrual weeks for each woman. Additional validation work must demonstrate that the methods and thresholds selected here are calibrated to ensure only the diagnosis of women who need treatment. Finally, women seeking treatment for PMDD in clinical settings may prove to be qualitatively different from women in research settings.

Research Applications

The C-PASS has myriad applications in research. In the context of clinical research, the use of a standardized, reliable system of diagnosis would ensure shared diagnostic meaning across laboratories, and would ensure homogenous samples. The C-PASS also allows for dimensional characterization of symptoms across samples, individuals, and cycles according to four central dimensions of PMDD diagnosis (see Table 2), which may allow for the eventual identification of meaningful differences, if any, between women with PMDD and other MRMDs. Further development of this system may allow for the identification of distinct subgroups with differing pathophysiology22. Finally, it should be noted that the C-PASS can also be used to identify cycles meeting criteria for PMDD, a feature that could be useful for defining treatment response.

Clinical Implications

There are currently no reliable and valid diagnostic procedures for PMDD that are feasible for widespread clinical application. Given the time involved in prospective assessment, nearly 90% of clinicians who treat PMDD rely on patient retrospective self-report, which we know to be prone to false positives, to make diagnoses19. This is troubling when considered in tandem with the present evidence that (1) there is a relatively low prevalence of true PMDD even among women seeking assessment for premenstrual symptoms, and (2) variability on retrospective self-report of premenstrual symptoms does not provide information about whether a standardized, prospective diagnosis of PMDD is present. Rigorous experimental23 and longitudinal14 studies have established the biological validity of PMDD, and treatments are available; however, assessments that combine validity, reliability, and efficiency need to be developed so that women with the disorder can receive treatment, and women without the disorder can search for alternative causes of their symptoms. Standardization of research diagnoses through the C-PASS represents an initial step toward development of efficient and reliable clinical tools. The current C-PASS materials may be immediately useful clinically; however, additional development is needed to digitize data collection and streamline the diagnostic process for clinical application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH099076, R01MH081837, and T32MH093315).

Footnotes

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Pearlstein T, Steiner M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: burden of illness and treatment update. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(4):291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Otto MW, Sweeney BH, Liberman RF, Harlow BL. Prevalence and predictors of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) in older premenopausal women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;70(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00458-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(1):41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbreich U, Bäckström T, Eriksson E, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome and guidelines for their quantification for research studies. 2009;23(3):123–130. doi: 10.1080/09513590601167969. http://dxdoiorgezproxyukyedu/101080/09513590601167969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean BB, Borenstein JE, Knight K, Yonkers K. Evaluating the Criteria Used for Identification of PMS. 2006;15(5):546–555. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.546. http://dxdoiorg/101089/jwh200615546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pugliesi K. Premenstrual syndrome: The medicalization of emotion related to conflict and chronic role strain. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDaniel SH. The interpersonal politics of premenstrual syndrome. Family Systems Medicine. 1988;6(2):134. [Google Scholar]

- 10.SA H, CA B, KA Y. Addressing concerns about the inclusion of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in DSM-5. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2014;75(1):70–76. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13cs08368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MJ, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Operationalizing DSM-IV criteria for PMDD: selecting symptomatic and asymptomatic cycles for research. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartlage SA, Freels S, Gotman N, Yonkers K. Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Secondary Analyses of Relevant Data Sets. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurt SW, Schnurr PP, Severino SK, et al. Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in 670 women evaluated for premenstrual complaints. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):525–530. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittchen HU, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med. 2002;32(1):119–132. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID-I. American Psychiatric; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endicott J, Halbreich U. Retrospective Report of Premenstrual Depressive Changes: Factors Affecting Confirmation by Daily Ratings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Rubinow DR, Schiller CE. Histories of abuse predict stronger within-person covariation of ovarian steroids and mood symptoms in women with menstrually related mood disorder. Psychoneuroendocinology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.026. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Evidence for a New Category for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craner JR, Sigmon ST, McGillicuddy ML. Does a disconnect occur between research and practice for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) diagnostic procedures? Women & Health. 2014;54(3):232–244. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.883658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etkin A, Cuthbert B. Beyond the DSM: Development of a Transdiagnostic Psychiatric Neuroscience Course. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(2):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s40596-013-0032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuthbert B, Insel T. Classification issues in women’s mental health: clinical utility and etiological mechanisms. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(1):57–59. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:55–99. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, Rubinow DR. Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;338(4):209–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.