Abstract

Background

Heavy episodic drinking is developmentally normative among adolescents and young adults, but is linked to adverse consequences in later life, such as drug and alcohol dependence. Genetic and peer influences are robust predictors of heavy episodic drinking in youth, but little is known about the interplay between polygenic risk and peer influences as they impact developmental patterns of heavy episodic drinking.

Methods

Data were from a multisite prospective study of alcohol use among adolescents and young adults with genome-wide association data (n=412). Generalized linear mixed models were used to characterize the initial status and slopes of heavy episodic drinking between age 15 and 28. Polygenic risk scores were derived from a separate genome-wide association study for alcohol dependence and examined for their interaction with substance use among the adolescents’ closest friends in predicting the initial status and slopes of heavy episodic drinking.

Results

Close friend substance use was a robust predictor of adolescent heavy episodic drinking, even after controlling for parental knowledge and peer substance use in the school. Polygenic risk scores were predictive of the initial status and early patterns of heavy episodic drinking in males, but not females. No interaction was detected between polygenic risk scores and close friend substance use for heavy episodic drinking trajectories in either males or females.

Conclusions

Although substance use among close friends and genetic influences play an important role in predicting heavy episodic drinking trajectories, particularly during the late adolescent to early adult years, we found no evidence of interaction between these influences after controlling for other social processes, such as parental knowledge and broader substance use among other peers outside of close friends. The use of longitudinal models and accounting for multiple social influences may be crucial for future studies focused on uncovering gene-environment interplay. Clinical implications are also discussed.

Keywords: Heavy episodic drinking, peer influences, development, polygenic risk score, gene-environment interaction

Introduction

Heavy episodic drinking behaviors, defined as the consumption of large volumes of alcohol (e.g., five or more standard drinks) within a set period of time (Gmel et al., 2011; Murgraff et al., 1999), are common among adolescents and young adults. In the United States, approximately 20% of high school seniors reported engaging in heavy episodic drinking and nearly 11% reported extreme heavy episodic drinking (i.e., 10 or more drinks on a single occasion) in the past two weeks (Patrick et al., 2013). Compared to adolescents who abstain from heavy episodic drinking, adolescents who engage in heavy episodic drinking earlier in life and with high frequency are elevated for multiple risk factors (e.g., parental psychopathology, family conflict and stress; Chassin et al., 2002) and are at the highest risk for developing negative outcomes in later life, including a higher incidence of adult drug and alcohol dependence (Chassin et al., 2002; Schulenberg et al., 1996) and health and medical problems (Oesterle et al., 2004). Since the initiation and progression in heavy episodic drinking coincides with several hallmarks of normative adolescent development (e.g. puberty, autonomy from adults, increased impulsivity; Chassin et al., 2002), understanding its etiology requires a developmental perspective that accounts for individual, family, and peer influences (Shin et al., 2009). The current investigation focused on understanding how genetic and environmental influences impact developmental patterns of heavy episodic drinking during this critical developmental period.

The importance of genetic factors for alcohol-related phenotypes has been well-established through twin studies (Prescott and Kendler, 1999; Knopik et al., 2004) and more recently through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). For instance, twin studies have shown that additive genetic influences account for 18–30% of the variance in alcohol-related phenotypes (i.e., heavy episodic drinking) for young adult females and 39–57% for young adult males (King et al., 2005), while GWAS have identified several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that may contribute to this variance, including those involved in the transcription of enzymes responsible for alcohol metabolism (Bierut et al., 2012; Gelernter et al., 2014). However, genetically associated markers identified through GWAS only account for a fraction of the total genetic variance. Using a method called genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA; Yang et al., 2011) and data from Netherlands Twin Register, one study estimated that the total variance explained by common SNPs for adult alcohol use problems was 33%, suggesting that a large portion of the heritability can be explained by variations in common SNPs in aggregate, rather than in isolation (Mbarek et al., 2015). These findings reinforce the idea that complex traits are largely influenced by polygenic variation, rather than one or a few SNPs (Plomin et al., 2009; Purcell et al., 2009). Researchers can index the composite effects of common SNPs by computing polygenic risk scores (PRS), which represent a quantitative distribution of aggregate genetic liability to predict the phenotypic variance in one sample using genome-wide information from a separate, independent sample. The PRS approach was first applied to predict the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Purcell et al., 2009) but has since been applied to predict risk for alcohol-related phenotypes (Kos et al., 2013; Salvatore et al., 2014a; Vink et al., 2014), explaining about .63–1.1% of variation in alcohol use behaviors. Although this is a relatively small amount of the total variance, it still constitutes a larger effect than single SNPs confer independently (Plomin et al., 2009).

Furthermore, genetic influences are known to interact with the environment (gene-environment interaction; GxE; Dick and Kendler, 2012). Twin studies have provided evidence of these effects with respect to peer substance use and genetic risk for adolescent alcohol use behaviors. Adolescents with high genetic liability for alcohol and other substance use were more vulnerable to the adverse influences of their best friends’ substance use than adolescents with low genetic liability (Harden et al., 2008). The interplay between genetic and peer influences for adolescent alcohol use behaviors are also evidenced by genetic association studies, where for example, adults carrying at least one copy of the long allele of the dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) were more influenced by their close friends’ alcohol use in the development of their own heavy episodic drinking than those without the long allele (Mrug and Windle, 2014), although this study was limited by a relatively small sample size and focused on only a single polymorphism in DRD4. Investigations with respect to PRS in the context of GxE have recently emerged as well, as high PRS for alcohol problems was recently shown to be more robust in predicting alcohol problems in an adolescent twin sample (i.e., Finnish Twin Study) under conditions of high peer deviance and low parental knowledge (Salvatore et al., 2014a), although the magnitude of these interactive effects were small (~.30% of the variance in alcohol problems). Collectively, the evidence suggests that genetic risk may be moderated by peer influences in predicting more broadly defined alcohol-related phenotypes in adolescents.

Importantly, GxE studies as they relate to peer influences on adolescent alcohol use behaviors have not widely controlled for concomitant processes that may confound their effects. For instance, adolescents and their closest friends strongly model and influence each other’s attitudes and perceptions towards drinking (i.e., socialization effects; Jaccard et al., 2005; Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). Close friends are typically embedded within a broader peer group (e.g., school settings) and this broader peer context influences the magnitude of socialization effects from close friends (Urberg et al., 1995; Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). Furthermore, socialization effects are also influenced by parental factors; the negative effects of close friends’ substance use are amplified when the quality of the parent-child relationship is strained (Jaccard et al., 2005). Thus, without accounting for concomitant processes (e.g., broader peer group and parental relationship), previous findings in the peer substance use literature more generally may have overestimated the effects of peer influences (Jaccard et al., 2005).

The goal of the current study was to use a developmental framework to investigate the relationship between polygenic influences, close friend substance use, and their interaction on heavy episodic drinking patterns during the period from adolescence to young adulthood, while simultaneously controlling for other social processes (i.e., parental knowledge, broader peer group substance use) that may confound close peer effects. Generalized linear mixed models were used to account for age-related variability in heavy episodic drinking patterns (Chassin et al., 2002), as well as to examine genetic and environmental influences on the initial status and subsequent trajectories. In line with previous GxE investigations on adolescent substance use (e.g., Harden et al., 2008; Mrug and Windle, 2014; Salvatore et al., 2014a), it is hypothesized that individuals with high PRS for alcohol dependence will have a more rapid escalation of heavy episodic drinking over time compared to individuals with low PRS, and that close friend substance use will moderate this association such that the increased prevalence of substance use among close friends will accelerate heavy episodic drinking trajectories among these individuals.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The original Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) study recruited probands through inpatient or outpatient substance-use treatment programs at seven sites across the United States and were included in the study if they met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) as well as criteria for alcoholism specified by Feighner and colleagues (1972). Control families (two parents and three or more offspring over the age of 14) were also selected from the community. All participants were interviewed across various psychiatric domains using the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA-IV) (Bucholz et al., 1994). Adolescents (younger than 18 years of age) were interviewed with a modified version of the SSAGA-IV that incorporated age-appropriate wording. A more detailed description of the COGA study is included elsewhere (Begleiter et al., 1995). The institutional review boards for all seven data collection sites, and additional data analysis sites, approved the study.

The current study uses data from the Prospective Study of COGA, which consists of 3,444 offspring or relatives of the probands and control families from the original COGA study, followed biennially since 2004. Data collection is on-going, although 33% of the study sample had been assessed 4 or more times as of 2013 (63% had >3 assessments). Of those 3,444 individuals, only a subset had GWAS data (n=412). Furthermore, only participants of European descent were initially genotyped in order to avoid confounds due to population stratification. See Table 1 for demographic information of the Prospective Study GWAS subsample.

Table 1.

Prospective Study (GWAS subsample) demographic information

| Baseline (n=412) |

2-year FU (n=387) |

3-year FU (n=321) |

6-year FU (n=241) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Males | 50.23 | 48.18 | 47.66 | 42.74 |

| Age (S.D.) | ||||

| Male | 16.72 (2.98) | 18.88 (3.32) | 20.78 (3.22) | 22.44 (3.13) |

| Female | 17.10 (3.12) | 19.17 (3.27) | 21.14 (3.28) | 22.85 (3.25) |

| % 18 years of age and older | ||||

| Male | 44.24 | 66.49 | 78.81 | 98.04 |

| Female | 49.30 | 65.33 | 83.23 | 97.08 |

| % Parent DSM-IV Alcohol Dep. | ||||

| Male | 46.08 | – | – | – |

| Female | 47.44 | – | – | – |

| % DSM-IV Alcohol Dep. | ||||

| Male | 3.68 | 11.24 | 9.92 | 11.11 |

| Female | 7.44 | 8.56 | 8.28 | 10.53 |

| % DSM-IV Marijuana Dep. | ||||

| Male | 7.58 | 10.99 | 10.07 | 15.15 |

| Female | 7.44 | 7.65 | 8.43 | 12.78 |

| % DSM-IV Tobacco Dep. | ||||

| Male | 8.76 | 11.89 | 17.88 | 24.00 |

| Female | 7.44 | 14.57 | 16.17 | 15.56 |

| % DSM-IV Other Drug Dep. | ||||

| Male | 2.76 | 6.01 | 5.33 | 9.09 |

| Female | 6.51 | 6.06 | 4.79 | 10.37 |

| Frequency of heavy episodic drinking means (S.D.) | ||||

| Male | 2.43 (2.64) | 3.78 (3.32) | 4.36 (3.30) | 4.49 (3.25) |

| Female | 2.00 (2.28) | 2.93 (2.84) | 3.25 (2.83) | 3.31 (2.77) |

| School substance use means (S.D.) | ||||

| Male | 7.72 (2.40) | 8.36 (2.00) | 8.59 (1.76) | 8.10 (1.87) |

| Female | 7.86 (2.44) | 8.52 (2.07) | 8.55 (1.83) | 8.27 (1.70) |

| Close friend substance use means (S.D.) | ||||

| Male | 9.22 (2.33) | 9.27 (2.32) | 9.06 (2.36) | 8.84 (2.47) |

| Female | 9.84 (2.25) | 9.79 (2.28) | 9.70 (2.26) | 9.69 (2.30) |

| Parental knowledge means (S.D.) | ||||

| Male | 12.10 (2.56) | 12.28 (2.38) | 12.41 (2.40) | 12.30 (2.18) |

| Female | 14.73 (2.48) | 12.97 (2.39) | 12.54 (2.71) | 12.85 (2.74) |

| Highest level of education (n) | ||||

| Less than high school | 52 | – | – | – |

| High school/GED | 132 | – | – | – |

| Tech school/one-year college | 54 | – | – | – |

| Two years of college | 56 | – | – | – |

| Three years of college | 17 | – | – | – |

| College degree | 64 | – | – | – |

| Graduate degree | 17 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 20 | – | – | – |

| Gross household income (n) | ||||

| $1–$9,999/year | 33 | – | – | – |

| $10,000–$19,999/year | 46 | – | – | – |

| $20,000–$29,999/year | 53 | – | – | – |

| $30,000–$39,999/year | 78 | – | – | – |

| $40,000–$49,999/year | 64 | – | – | – |

| $50,000–$74,999/year | 76 | – | – | – |

| $75,000–$99,999/year | 22 | – | – | – |

| $100,000–$149,999/year | 10 | – | – | – |

| $150,000 or more/year | 7 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 23 | – | – | – |

Note. FU = follow up; baseline data for parental knowledge, school substance use and close friend substance use were used in the current analysis (see Method section for explanation); DSM-IV Other Drug Dep. = if DSM-IV criteria for Stimulant, Sedative, Opiate, or Other Drug Dependence were met; Italicized figures represent significant (p<.05) mean differences between sexes.

Measures

Heavy episodic drinking

The frequency of heavy episodic drinking was assessed via the item “How often did you have 5 or more [standard] drinks in a 24-hour period in the last 12 months?” in the Alcohol Use Disorder Section of the SSAGA-IV. Participants were first queried as to whether or not they ever consumed any alcoholic drinks (e.g., beer, wine, liquor, etc.) in their lifetime. A positive response was followed by additional queries regarding their alcohol use, otherwise, the interviewer skipped to the next section of the SSAGA-IV. Participants who stated they had “never had even one full drink of alcohol” at the time of the assessment were included in the analyses so that the sample more fully captured the diversity of drinking patterns and did not reflect an exclusively high-risk group. Participants were then given a card with definitions for a standard drink and asked to recall the number of days they consumed 5 or more standard drinks in a 24-hour period in the last 12-months. Their response was then converted onto a 13-point quasi-continuous scale, where higher numbers corresponded to greater frequency of heavy episodic drinking (e.g., “never” = 1, “1 day per week” = 6, and “every day” = 13). Data from baseline and three follow-up assessments were used in the longitudinal analysis (see Statistical analysis section for coding procedures).

Close friend substance use

Close friend substance use was assessed from the Home Environment section of SSAGA-IV. Four items, adapted from the FinnTwin studies (Rose and Dick, 2004), were queried to participants pertaining to the prevalence of 1) cigarette smoking, 2) alcohol use, 3) marijuana use, and 4) other illicit drug use among the participants’ best friends. For instance, participants were asked “how many of your best friends smoke?” and responded to the question on a four-point scale: “none of them” (1), a few of them (2), most of them (3), and “all of them” (4). If participants were over the age of 18, they were instead asked to report on the prevalence of substance use among their close friends retrospectively, between the ages of 12–17. Since data from adults were retrospective, specifying close friend substance use as a time-varying covariate would not have been appropriate for the full sample. Hence, only the data from baseline assessment were used for the analysis. A composite score was used.

Close friend substance use was additionally assessed from the Important People and Activities (IPA) questionnaire (Longabaugh et al., 1995). Since the IPA was administered to a subset of the COGA Prospective Study sample (210 out of 412 in the genotypic sample), analyses involving the IPA were included as secondary analyses. Participants were asked to name at least four “important people” in their lives (excluding relatives, but including siblings), and then rate the frequency of that person’s alcohol use on a 0 to 7 scale. A score was computed by the average of the frequency of alcohol use among each of the important individuals listed by the participant. Baseline data were used.

Covariates

Parental knowledge was assessed in the Home Environment section of the SSAGA-IV (4 items; “how many of your friends do you parent figures know?” “my parent figures know about my plans,” “my parent figures have a pretty good idea of my interests, activities, and whereabouts” and “my parent figures know where I am and who I am with when I am not at home”). Parental knowledge items were rated on a four-point ordinal scale: “always” (4), “usually” (3), “sometimes” (2) and “rarely” (1). School substance use also measured from the Home Environment section of the SSAGA-IV and was the composite of responses to four items pertaining to the perceived prevalence of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, and other illicit drug use among the “kids you go to school with.” These items were virtually analogous to the close friend substance use variables in that participants responded to each question on a four-point scale: “none of them” (1), a few of them (2), most of them (3), and “all of them” (4). If participants were over the age of 18, they were instead asked to report on the prevalence of substance use among their peers retrospectively, between the ages of 12–17. Baseline data were used.

Genotyping and PRS computation

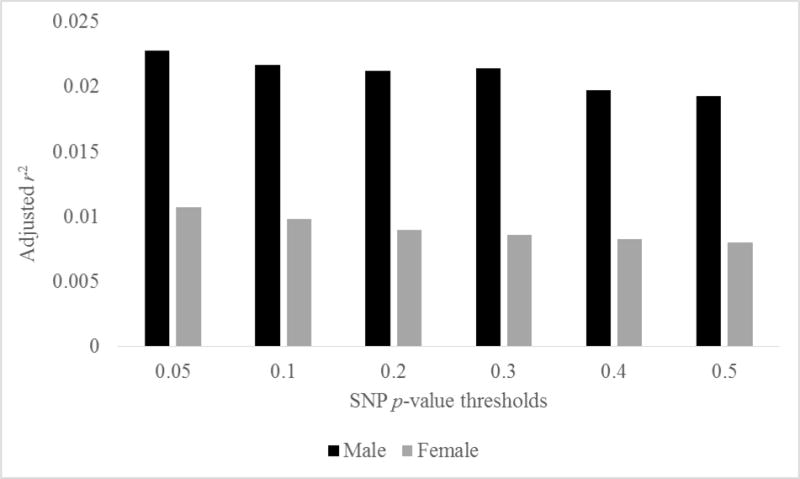

A GWAS on DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms was first conducted in the adult European-American subsample (age 29–88; n=1,249; 45% male) of the original COGA study (see Wang et al., 2013 for a similar analysis using this sample). This sample was genotyped on the Illumina Human OmniExpress array 12.VI. 587,378 SNPs with minor allele frequency >5% were analyzed. Covariates included sex, age at interview, and cohort. Manhattan and Q-Q plots from the GWAS are provided in the Appendix section (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2, respectively). From this GWAS, “weights” were derived from t-scores of the most significant SNPs based on various p-value thresholds, from p-values .05 to .50, which were then used to calculate a PRS for participants in the Prospective Study using PLINK software (Purcell et al., 2007). For each SNP, the GWAS-derived t-scores of the associated allele were multiplied by 0, 1 or 2 (depending on the number of risk alleles that individual carried). The final PRS was the sum of the weighted SNPs. Figure 1 shows the proportion of variance explained (in sample size adjusted r2) in the initial status of heavy episodic drinking by PRS at each p-value threshold. Adjusted r2 values ranged between 1.9–2.3% for males and .8–1.1% for females, which is about what was expected based on previous findings (Salvatore et al., 2014a; Vink et al., 2014). SNPs below the p<.05 threshold were used for the subsequent GxE analyses, as they explained the highest proportion of variance in initial status of heavy episodic drinking.

Figure 1.

Variance in heavy episodic drinking (initial status) explained by PRS at each p-value threshold

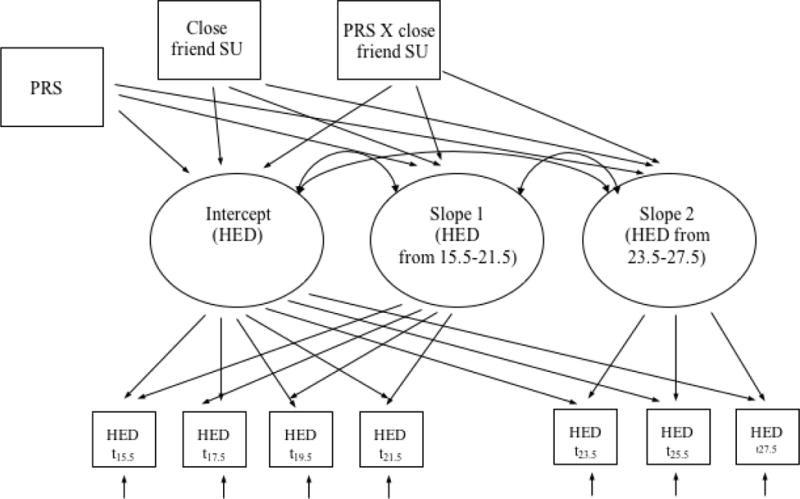

Statistical analysis

Heavy episodic drinking data were first grouped by age, resulting in 14 separate points of measurement from age 15 to 28. However, given the wide age range in the sample and the fairly restricted sample size, this approach resulted in a large amount of missing data for certain ages. To partially alleviate this concern, and given that assessments were conducted biennially, data were combined into two-year intervals to create 7 separate points of measurement (ages 15.5, 17.5, 19.5, 21.5, 23.5, 25.5 and 27.5). A generalized linear mixed model with log link and Poisson distribution was used to model the trajectory of heavy episodic drinking (Figure 2). Linear, quadratic, and linear piecewise growth parameters were estimated and compared, in order to determine an optimal model based on information criteria fit statistics (i.e., AIC and BIC). The piecewise model was specified as followed: the first portion of the slope reflected the change in heavy episodic drinking from adolescence (age 15.5) to early adulthood (age 21.5), and the second portion of the slope reflects adult trajectories of heavy episodic drinking, from age 23.5 to age 27.5. The intercept was set at age 15.5. Given the possibility of sex differences in genetic heritability estimates for alcohol use problems (King et al., 2005), analytic models were tested separately for males and females, resulting in six total models tested. Hence, direct statistical comparisons (e.g., mean differences) between males and females were not directly tested in the current study. Upon selection of the best fitting model, covariates were included into a hierarchical poisson regression model. In the initial model step, intercept and slopes were estimated. In the second model, covariates (i.e., school substance use, parental knowledge), close friend substance use and PRS were added. In the final (fully saturated) model, cross-products between PRS and close friend substance use variables were included.

Figure 2. Longitudinal gene-environment interaction model.

Note. HED = heavy episodic drinking; PRS = polygenic risk scores; SU = substance use

Results

Model fit

Comparisons of model fit were evaluated for linear, quadratic, and linear piecewise growth models, separately for males and females (see Supplemental Table 1). Similar to previously published findings using the same data (i.e., Dick et al., 2013), the piecewise models were marginally superior to the linear model and quadratic models in males and females. The piecewise growth model was selected for subsequent analyses for a more straightforward interpretation of covariate effects on heavy episodic drinking trajectories across two separate development epochs: (1) adolescence (age 15.5) to early adulthood (age 21.5) and (2) older adult (age 23.5 to age 27.5).

Regression

In the base model, only intercepts and slopes terms were estimated, separately for males and females. The mean initial heavy episodic drinking status (i.e., at age 15.5) significantly differed from zero for both males (b = 1.83, S.E. = .02, p < .0001) and for females (b = 1.52, S.E. = .02, p < .0001). For both sexes, heavy episodic drinking exhibited a positive trajectory from age 15.5 to 21.5 (males: b = .20, S.E. = .01, p < .0001, females: b = .18, S.E. = .01, p < .0001) and a slight negative trajectory from age 23.5 to 27.5 (males: b = −.08, S.E. = .01, p < .0001, females: b = .10, S.E. = .01, p < .0001). In the second model, parental knowledge and school substance use prevalence were included as covariates while close friend substance use and PRS were included as main effects to predict intercepts and slopes for male and female heavy episodic drinking (Table 2). For both sexes, close friend substance use prevalence strongly predicted a higher initial status of heavy episodic drinking and a greater rate of change in heavy episodic drinking between ages 15.5 to 21.5. For males specifically, PRS predicted a higher initial status of heavy episodic drinking and a greater rate of change in heavy episodic drinking between ages 15.5 to 21.5. The third and final model (Table 3) included the cross product between PRS and close friend substance use prevalence, while also accounting for their main effects and controlling for parental knowledge and school substance use prevalence. No significant interactions emerged between close friend substance use prevalence and PRS for either males or females for the heavy episodic drinking intercept and slopes.

Table 2.

Hierarchical poisson regression: Main effects of PRS and close friend substance use on heavy episodic drinking intercepts and slopes

| Males

|

Females

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | s.e. | p | b | s.e. | p | ||

| Intercept | PRS | 6.76 | 2.18 | <.01 | −2.75 | 2.52 | .28 |

| Parental knowledge | .09 | .09 | .31 | −.12 | .14 | .37 | |

| School substance use | .01 | .12 | .96 | −.23 | .16 | .14 | |

| Close friend substance use | .63 | .09 | <.01 | .78 | .12 | <.01 | |

| Slope 1 | Parental knowledge | −.01 | .02 | .48 | .00 | .02 | .85 |

| (Age 15.5–21.5) | PRS | −.81 | .38 | .05 | .62 | .44 | .16 |

| School substance use | .01 | .02 | .70 | .02 | .03 | .40 | |

| Close friend substance use | −.06 | .02 | <.001 | −.09 | .02 | <.01 | |

| Slope 2 | Parental knowledge | .01 | .02 | .78 | .02 | .02 | .38 |

| (Age 23.5–27.5) | PRS | .49 | .44 | .27 | −.66 | .51 | .20 |

| School substance use | −.05 | .03 | .13 | .04 | .03 | .13 | |

| Close friend substance use | .01 | .02 | .76 | .03 | .02 | .23 | |

Table 3.

Hierarchical poisson regression: PRS × close friend substance use interaction on heavy episodic drinking intercepts and slopes

| Males

|

Females

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | s.e. | p | b | s.e. | p | ||

| Intercept | PRS | 7.54 | 2.21 | <.01 | −2.76 | 2.52 | .27 |

| Parental knowledge | .13 | .09 | .16 | −.10 | .14 | .45 | |

| School substance use | .01 | .12 | .93 | −.24 | .16 | .13 | |

| Close friend substance use | .69 | .10 | <.0001 | .81 | .15 | <.0001 | |

| PRS × close friend substance use | −3.22 | 2.46 | .19 | −.47 | 2.69 | .86 | |

| Slope 1 | Parental knowledge | −.01 | .02 | .45 | .00 | .02 | .83 |

| (Age 15.5–21.5) | PRS | −.82 | .38 | .03 | .77 | .44 | .08 |

| School substance use | .01 | .02 | .74 | .02 | .03 | .36 | |

| Close friend substance use | −.06 | .02 | <.01 | −.09 | .02 | <.01 | |

| PRS × close friend substance use | .00 | .43 | 1.00 | −.18 | .48 | .70 | |

| Slope 2 | Parental knowledge | .00 | .02 | .90 | .02 | .02 | .44 |

| (Age 23.5–27.5) | PRS | .41 | .45 | .37 | −1.06 | .56 | .06 |

| School substance use | −.05 | .03 | .11 | .05 | .03 | .10 | |

| Close friend substance use | .00 | .02 | .90 | .01 | .03 | .73 | |

| PRS × close friend substance use | .31 | .49 | .52 | .70 | .53 | .19 | |

Secondary analyses

First, we assessed whether GxE effects were attenuated due to having included school substance use and parental knowledge as covariates. After removing covariates from the model, results were entirely consistent with the primary models (Supplemental Table 2).

Second, to address the potential concern that the SSAGA-IV, which is a clinical interview, was not sensitive to adequately assessing environmental domains, we examined interactions between close friend substance use frequency measured from the IPA and PRS for heavy episodic drinking outcomes. Results of these regression models were somewhat consistent with the primary analyses (Supplemental Table 3), although PRS was not predictive of initial heavy episodic drinking status in these models. This may have been due to the limited power to detect effects (given the small sample size) as well as the possibility of cohort effects, as the smaller sample size was due to the fact that only certain COGA sites administered this instrument. Furthermore, the assessment of close friend substance use frequency was not completely analogous, as the IPA indexed the severity of close friend alcohol use whereas the SSAGA indexed the number of close friends who use substances.

Third, to account for the possibility of gene-environment correlation, which may confound the interpretation of potential GxE effects (Knafo and Jaffee, 2013) we examined correlations between PRS and each of the environmental variables assessed in the study. PRS was significantly associated with close friend substance use (r =.23, p < .01), parental knowledge (r =−.18, p < .01) and school substance use (r =.16, p < .01). To address concerns that the GxE results were impacted by the presence of G-E correlation, we used standardized residual values from a regression model where each environmental variable was separately regressed on PRS. The use of residualized variables statistically eliminates G-E correlation effects in the model because the genetic and environmental effects have been partialed from one another (Salvatore et al., 2014b). Parallel analyses (i.e., hierarchical poisson regressions) were conducted in which growth parameters (i.e., intercepts and slopes) were regressed on to the standardized residual values for close friend substance use, PRS and their interaction, controlling for the standardized residual values for parental knowledge and school substance use. Results from this analysis was consistent with fully saturated non-residual model (Supplemental Table 4). That is, the interaction between PRS and close friend substance remained non-significant, including after accounting for the presence of a gene-environment correlation.

Discussion

This investigation examined the interplay between polygenic influences underlying alcohol dependence (i.e., PRS) and the influence of close friends’ substance use on the development of heavy episodic drinking in adolescents and young adults. Controlling for parental knowledge and the broader network of peer substance use, close friend substance use predicted a higher initial status and a greater rate of increase in heavy episodic drinking between the ages of 15.5 and 21.5 for both males and females. Additionally, PRS predicted a higher initial status and a greater rate of increase in heavy episodic drinking between the ages of 15.5 to 21.5, but only among males. There was no evidence of interaction between PRS and close friend substance use on heavy episodic drinking outcomes.

Peer influences are central to developmental models of substance use. The findings suggest that close friends who use substances may have a particularly strong influence on heavy episodic drinking behaviors during adolescence and young adulthood, even after controlling for the perception of substance use among the larger peer group and self-rated parental knowledge. The increased autonomy this developmental period may afford greater opportunity to engage in drinking behaviors, especially when close friends model and reciprocate such behaviors via socialization effects (Shanahan and Hofer, 2005). Proximal social structures may also be more salient predictors of heavy episodic drinking than distal ones, as individuals are more pressured to support, provide, and appease in closer relationships (Brown et al., 1997). Other studies found that different peer contexts (i.e., close friends, peer groups, and social crowds) demonstrate separable effects on adolescent substance use, and that the association between substance use among close friends and the adolescents’ own substance use was moderated by their peer group status (Hussong, 2002), although our own data did not reveal three-way interactive effects1. The absence of a main effect for close friend substance use on the later stages heavy episodic drinking trajectories during young adulthood (i.e., slope 2) may reflect the attenuated influence that high school peers have on the later young adult years in terms of heavy episodic drinking. However, it is possible that substance use among current (i.e., adult) peers also play an influential role on drinking behaviors during the later young adult years (Mrug and Windle, 2014); these data were not available for the current study, unfortunately. It is noted that an important limitation was that peer influences were modeled as unidirectional effects, in which close friends were assumed to predict adolescent heavy episodic drinking and not conversely. Adolescents at high genetic risk for alcohol use problems are perhaps even more influential to the peers around them, as early substance use is often associated with greater popularity and social influence (Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). Future studies of adolescent peer influences should feature more rigorous investigations of peer influences (e.g., direct observations, prospective data from a young age) in order to better characterize bidirectional peer effects.

PRS predicted a higher initial status and a greater rate of change in heavy episodic drinking during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood (age 15.5 to 21.5) for males, but not for females. Furthermore, there was no main effect for PRS on heavy episodic drinking trajectories from young adulthood to later young adulthood (age 23.5 to 27.5). First, research on sex differences in genetic influences for alcohol-related phenotypes have been mixed, as some studies have reported no differences in the degree of genetic influences (Prescott et al., 1999; Agrawal et al., 2008) or stronger genetic effects for one sex over the other (Perry et al., 2013; Dick et al., 2007). Crucially, earlier patterns of drinking (i.e., age-of-onset) are not typically accounted for in these studies, and some evidence suggests that genetic influences are stronger among earlier onset male drinkers than female drinkers (McGue et al., 1992, although see Dick et al., 2007 for an exception). It is speculated that the more robust association between PRS for alcohol dependence and early patterns of heavy episodic drinking in males may be developmentally-driven, and that discrepancies in the literature regarding sex differences in genetic influences for alcohol-related phenotypes may be addressed by controlling for age-of-onset in cross-sectional designs, or by adopting a more developmental approach that accounts for the transition from adolescence into adulthood.

Regarding GxE, previous studies reported interactive effects between genetic and peer influences on the development of alcohol use behaviors in adolescents (Mrug and Windle, 2014; Salvatore et al., 2014a). The current study found no evidence of interaction between close friend substance use and PRS in predicting either initial levels of heavy episodic drinking (intercepts) or the rate of change of heavy episodic drinking from adolescence to early adulthood (slope 1) and from early adulthood to later adulthood (slope 2). It is possible that study-related differences between the current study and others may partially account for the absence of GxE effect in the current study. For instance, Mrug and Windle (2014) used a candidate gene approach to testing GxE and focused on a single (albeit well-characterized) DRD4 polymorphism in relation to peer substance use effects on trajectories of alcohol use. Salvatore et al. (2014a) found a significant GxE effect involving PRS and low parental knowledge and high peer deviance on age 14 alcohol problems, but they used cross-sectional moderation analyses on a twin sample (FinnTwin12). The failure to replicate previous findings does not necessarily indicate the absence of a GxE effect, but reflects the well-known challenges of uncovering small GxE effects within a limited study sample size for complex phenotypes (see Manuck and McCaffery, 2014 for relevant review on this topic). Studies should continue to prioritize analytic rigor (e.g., longitudinal modeling, multiple measures of the environment) and cutting-edge genotyping assays to more precisely characterize the extent to which genes and environments interact as they relate to complex phenotypes.

The absence of interactive effects between PRS and close friend substance use on heavy episodic drinking outcomes may also be due to the stringent test of GxE that were conducted in the current study, where parental knowledge and school substance use effects were statistically controlled within a rigorous development framework. Few studies have accounted for concomitant social processes (i.e., familial, school and peer influences) in the study of GxE, and it is speculated that the effects of specific environmental influences on adolescent behavior may be overestimated without considering multiple social influences simultaneously (Jaccard et al., 2005), particularly in the context of GxE. Furthermore, the presence of gene-environment correlations may confound the study of GxE effects (Knafo and Jaffee, 2013). For instance, adolescents with a genetic propensity for alcohol use problems and behaviors may select (or attract) peers who also engage in substance use behaviors, suggesting that the same genes responsible for conferring risk for alcohol use problems may be simultaneously influencing environmental exposure as well. One safeguard against confounds driven by multiple social influences involved in GxE and gene-environment correlations are studies of experimentally manipulated environmental exposures, such as those involving randomized clinical trials or lab experiments (Manuck and McCaffery, 2014), but these studies have only recently emerged (see van Ijzendoor et al., 2011 for an example).

Another possibility for these divergent results is that utilizing a GWAS approach to characterize genetic risk for alcohol problems may preclude identification of genetic effects that may be contingent upon exposure to environmental conditions (Caspi et al., 2010). For example, rs1229984 (Arg48His) on ADH1B has been identified and subsequently replicated in GWAS for its association with alcohol dependence across different populations (Bierut et al., 2012; Gelernter et al., 2014). Despite a robust main effect of rs1229984 on alcohol-related outcomes across samples, GxE studies involving this variant have so far produced inconsistent results (e.g., Olfson et al., 2014; Meyers et al., 2013; Sartor et al., 2014). Although this is partly attributable to differences in how studies measure the environment, robust genotype-to-phenotype associations detected in GWAS may not guarantee robust GxE findings. One possible direction for future studies is to characterize genetic variation in phenotypes that are plausibly related to how an individual reacts to environmental factors (e.g., stress sensitivity, social vulnerability) (Caspi et al., 2010).

Some study limitations are noteworthy. First, young adult participants were asked to recall their parenting and peer influences retrospectively, whereas adolescents reported on these effects concurrently. Although participants were followed longitudinally, they did not contribute to data across the entire age range in the study (age 15 to 28). To characterize the heterogeneity of heavy episodic drinking, a growth mixture model would have been preferred. Limited data precluded this analysis, although data collection in the Prospective Study is on-going and we anticipate on having enough data with which to perform more rigorous examinations of growth mixture models that extend beyond age 28 in future investigations. Second, the participants in the Prospective Study were genetically related to the participants of the original COGA study, which was a case-control designed study (proband status of the relatives was not controlled for in the current analyses). Thus, the derivation of PRS did not involve a completely independent discovery and target dataset. As an overlap between these datasets may potentially lead to an overestimation of the prediction accuracy for the PRS (Wray et al., 2013), interpretations regarding the main effect of the PRS on heavy episodic drinking outcomes should be made with some caution. On the other hand, it is possible that this estimation may simply reflect the enrichment of genes for alcohol use in both samples. In other words, given that alcohol use disorders are known be influenced by many genes of small effect, using genetically-related case-control samples that are likely enriched for the same small-effect genes associated with alcohol use may lead to more robust characterizations of risk. Although this is beyond the scope of the current study, future studies should examine whether PRS effects significantly differ between discovery samples with related versus and non-related individuals to the target sample. Third, heavy episodic drinking was defined as having five or more alcoholic drinks within a 24-hour period, which is a more stringent threshold for females where four drinks are considered the typical threshold. Hence, sex differences regarding genetic and environmental influences on trajectories of heavy episodic drinking could not be explicitly tested in the current analyses, although separate analytic models were conducted for males and females. Using sex-specific cutoffs (i.e., according the standard definitions of binge drinking) may potentially lead to a more consistent pattern of results for males and females. Additionally, given sex differences in heritability estimates for alcohol use problems (King et al., 2005), it is possible that different genes may be involved for alcohol-related phenotypes in males and females. Future studies may consider conducting GWAS separately for males and females, so that PRS are sex-specific. Finally, the findings may not be generalizable as the analyses were limited to European-Americans. Recent evidence suggests that the association of alcohol dependence and specific genetic variants may differ between racial-ethnic groups (Gelernter et al., 2014).

The current study is innovative for investigating GxE effects using a polygenic approach within a developmentally-sensitive design. Including those that have already been mentioned, there are several additional implications for future research. Different phenotypic targets for PRS may be warranted for researchers who are primarily interested in GxE (e.g., stress sensitivity). Alternatively, researchers can focus on testing GxE using genes that have already been (or will be) identified through GWAS, although having “high quality” environment measures will be important for these types of studies (Caspi et al., 2010). From a clinical perspective, PRS has the potential to explain a significant amount of the variation in psychiatric disorders as sample sizes increase but the current findings fall well short of being able to make any clinically meaningful predictions. Investigating environmental influences simultaneously with genetic information may be crucial for enhancing our abilities to make accurate diagnostic predictions down the line.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA), Principal Investigators B. Porjesz, V. Hesselbrock, H. Edenberg, L. Bierut, includes ten different centers: University of Connecticut (V. Hesselbrock); Indiana University (H.J. Edenberg, J. Nurnberger Jr., T. Foroud); University of Iowa (S. Kuperman, J. Kramer); SUNY Downstate (B. Porjesz); Washington University in St. Louis (L. Bierut, A. Goate, J. Rice, K. Bucholz); University of California at San Diego (M. Schuckit); Rutgers University (J. Tischfield); Texas Biomedical Research Institute (L. Almasy), Howard University (R. Taylor) and Virginia Commonwealth University (D. Dick). Other COGA collaborators include: L. Bauer (University of Connecticut); D. Koller, S. O’Connor, L. Wetherill, X. Xuei (Indiana University); Grace Chan (University of Connecticut); S. Kang, N. Manz, (SUNY Downstate); J-C Wang (Washington University in St. Louis); A. Brooks (Rutgers University); and F. Aliev (Virginia Commonwealth University). A. Parsian and M. Reilly are the NIAAA Staff Collaborators. We continue to be inspired by our memories of Henri Begleiter and Theodore Reich, founding PI and Co-PI of COGA, and also owe a debt of gratitude to other past organizers of COGA, including Ting-Kai Li, currently a consultant with COGA, P. Michael Conneally, Raymond Crowe, and Wendy Reich, for their critical contributions.

Support

COGA is supported by NIH Grant U10AA008401 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). We thank the Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine for help with genomic analysis. The Center is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and by ICTS/CTSA Grant# UL1RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Funding support for GWAS genotyping, which was performed at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research, was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the NIH GEI (U01HG004438), and the NIH contract “High throughput genotyping for studying the genetic contributions to human disease” (HHSN268200782096C).

The authors were supported by individual grants from NIAAA (K02AA018755; DMD and F32AA02269 and K01AA024152; JES) and a core grant to the Waisman Center from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (P30-HD03352; JJL). The authors thank Kim Doheny and Elizabeth Pugh from CIDR and Justin Paschall from the NCBI dbGaP staff for valuable assistance with genotyping and quality control in developing the dataset available at dbGaP. This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Results available upon request.

References

- Agrawal A, Hinrichs AL, Dunn G, Bertelsen S, Dick DM, Saccone SF, Saccone NL, Grucza RA, Wang JC, Cloninger CR, Edenberg HJ. Linkage scan for quantitative traits identifies new regions of interest for substance dependence in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Reich T, Hesselbrock V, Porjesz B, Ting-Kai L, Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Rice JP. The collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Alcohol Research and Health. 1995;19:228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Goate AM, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Bertelsen S, Fox L, Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Grucza R, Hesselbrock V, Kramer J. ADH1B is associated with alcohol dependence and alcohol consumption in populations of European and African ancestry. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17:445–450. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Dolcini MM, Leventhal A. Transformations in peer relationships at adolescence: Implications for health-related behavior. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1997. pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Focus. 2010;8:398–416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Cho SB, Latendresse SJ, Aliev F, Nurnberger JI, Edenberg HJ, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock VM, Porjesz B, Bucholz K, Wang JC. Genetic influences on alcohol use across stages of development: GABRA2 and longitudinal trajectories of drunkenness from adolescence to young adulthood. Addiction Biology. 2014;19:1055–1064. doi: 10.1111/adb.12066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Kendler KS. The impact of gene–environment interaction on alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2012;34:318–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Pagan JL, Holliday C, Viken R, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Gender differences in friends’ influences on adolescent drinking: A genetic epidemiological study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:2012–2019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Almasy L, Koesterer R, Smith AH, Anton R, Preuss UW, Ridinger M, Rujescu D, Wodarz N. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence: significant findings in African-and European-Americans including novel risk loci. Molecular Psychiatry. 2014;19:41–49. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Almasy L, Koesterer R, Smith AH, Anton R, Preuss UW, Ridinger M, Rujescu D, Wodarz N. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence: significant findings in African-and European-Americans including novel risk loci. Molecular Psychiatry. 2014;19:41–49. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Kuntsche E, Rehm J. Risky single-occasion drinking: bingeing is not bingeing. Addiction. 2011;106:1037–1045. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Elder GH, Cai T, Hamilton N. Gene–environment interactions: Peers’ alcohol use moderates genetic contribution to adolescent drinking behavior. Social Science Research. 2009;38:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Hill JE, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Gene-environment correlation and interaction in peer effects on adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner C, Dick DM. Predicting alcohol consumption in adolescence from alcohol-specific and general externalizing genetic risk factors, key environmental exposures and their interaction. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1507–1516. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000190X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Burt SA, Malone SM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Etiological contributions to heavy drinking from late adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:587–598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafo A, Jaffee SR. Gene–environment correlation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopik VS, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Nelson EC, Statham D, Whitfield JB, Martin NG. Genetic effects on alcohol dependence risk: re-evaluating the importance of psychiatric and other heritable risk factors. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1519–1530. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB, McCaffery JM. Gene-environment interaction. Annual Review of Psychology. 2014;65:41–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbarek H, Milaneschi Y, Fedko IO, Hottenga JJ, de Moor MH, Jansen R, Gelernter J, Sherva R, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Penninx BW. The genetics of alcohol dependence: Twin and SNP‐based heritability, and genome‐wide association study based on AUDIT scores. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2015;168:739–748. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Pickens RW, Svikis DS. Sex and age effects on the inheritance of alcohol problems: a twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:3–17. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JL, Shmulewitz D, Wall MM, Keyes KM, Aharonovich E, Spivak B, Weizman A, Frisch A, Edenberg HJ, Gelernter J, Grant BF. Childhood adversity moderates the effect of ADH1B on risk for alcohol‐related phenotypes in Jewish Israeli drinkers. Addiction Biology. 2015;20:205–214. doi: 10.1111/adb.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Windle M. DRD4 and susceptibility to peer influence on alcohol use from adolescence to adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;145:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgraff V, Parrott A, Bennett P. Risky single-occasion drinking amongst young people–definition, correlates, policy, and intervention: a broad overview of research findings. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34:3–14. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:204–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson E, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger JI, Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Almasy LA, Chorlian D, Dick DM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, Kuperman S. An ADH1B Variant and Peer Drinking in Progression to Adolescent Drinking Milestones: Evidence of a Gene‐by‐Environment Interaction. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:2541–2549. doi: 10.1111/acer.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, Maggs JL, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:1019–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, Bucholz K, Edenberg H, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, Nurnberger JI. Gender-specific gene–environment interaction in alcohol dependence: the impact of daily life events and GABRA2. Behavior Genetics. 2013;43:402–414. doi: 10.1007/s10519-013-9607-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Haworth CM, Davis OS. Common disorders are quantitative traits. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:872–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Sex differences in the sources of genetic liability to alcohol abuse and dependence in a Population‐Based sample of US twins. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1136–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of male twins. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:34–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, Ruderfer DM, McQuillin A, Morris DW, O’Dushlaine CT. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Dick DM. Gene-environment interplay in adolescent drinking behavior. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004;28:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore JE, Aliev F, Bucholz K, Agrawal A, Hesselbrock V, Hesselbrock M, Bauer L, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, Kramer JR, Edenberg HJ. Polygenic risk for externalizing disorders gene-by-development and gene-by-environment effects in adolescents and young adults. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014b doi: 10.1177/2167702614534211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore JE, Aliev F, Edwards AC, Evans DM, Macleod J, Hickman M, Lewis G, Kendler KS, Loukola A, Korhonen T, Latvala A. Polygenic scores predict alcohol problems in an independent sample and show moderation by the environment. Genes. 2014a;5:330–346. doi: 10.3390/genes5020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Wang Z, Xu K, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. The Joint Effects of ADH1B Variants and Childhood Adversity on Alcohol Related Phenotypes in African‐American and European‐American Women and Men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;3:2907–2914. doi: 10.1111/acer.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context in gene–environment interactions: Retrospect and prospect. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Edwards EM, Heeren T. Child abuse and neglect: relations to adolescent binge drinking in the national longitudinal study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) Study. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Değirmencioğlu SM, Tolson JM, Halliday-Scher K. The structure of adolescent peer networks. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Foroud T, Hinrichs AL, Le NX, Bertelsen S, Budde JP, Harari O, Koller DL, Wetherill L, Agrawal A, Almasy L. A genome-wide association study of alcohol-dependence symptom counts in extended pedigrees identifies C15orf53. Molecular Psychiatry. 2013;18:1218–1224. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray NR, Yang J, Hayes BJ, Price AL, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Pitfalls of predicting complex traits from SNPs. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2013;14:507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrg3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.