Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax account for more than 95% of all human malaria infections, and thus pose a serious public health challenge. To control and potentially eliminate these pathogens, it is important to understand their origins and evolutionary history. Until recently, it was widely believed that P. falciparum had co-evolved with humans (and our ancestors) over millions of years, while P. vivax was assumed to have emerged in southeastern Asia following the cross-species transmission of a parasite from a macaque. However, the discovery of a multitude of Plasmodium spp. in chimpanzees and gorillas has refuted these theories and instead revealed that both P. falciparum and P. vivax evolved from parasites infecting wild-living African apes. It is now clear that P. falciparum resulted from a recent cross-species transmission of a parasite from a gorilla, while P. vivax emerged from an ancestral stock of parasites that infected chimpanzees, gorillas and humans in Africa, until the spread of the protective Duffy-negative mutation eliminated P. vivax from human populations there. Although many questions remain concerning the biology and zoonotic potential of the P. falciparum- and P. vivax-like parasites infecting apes, comparative genomics, coupled with functional parasite and vector studies, are likely to yield new insights into ape Plasmodium transmission and pathogenesis that are relevant to the treatment and prevention of human malaria.

Keywords: Malaria, African apes, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Laverania, Zoonotic transmission, Evolution

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Of the Plasmodium spp. known to commonly infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax cause the vast majority of malaria morbidity and mortality, and are the principal targets of malaria prevention and eradication efforts. Plasmodium falciparum is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa where it is responsible for nearly 200 million clinical cases (Bhatt et al., 2015) and over 300,000 malaria-related deaths annually, predominantly in children under 5 years of age (World Health Organization, 2015). Plasmodium vivax is rare in sub-Saharan Africa, but endemic in many parts of Asia, Oceania, as well as Central and South America where it causes an estimated 16 million cases of clinical malaria, which represents approximately half of all malaria cases outside Africa (www.who.int/malaria).

Given the devastating effects of malaria, the origins of the Plasmodium parasites infecting humans have long been a subject of interest. Descriptions of malaria-like illness can be found in ancient texts from China, India, the Middle East, Africa and Europe, indicating that humans have been combatting Plasmodium infections throughout much of our recorded history (Carter and Mendis, 2002). Indeed, variants in the human genome that are associated with resistance to Plasmodium infection and malaria-associated disease are estimated to be thousands of years old (Hedrick, 2011). One such variant is the sickle cell trait, which is common in African populations and protects against fatal P. falciparum malaria (Taylor et al., 2012). Similarly, a mutation that abolishes the expression of the Duffy antigen receptor of chemokines on the surface of red blood cells (the so-called “Duffy-negative phenotype”) approaches fixation in western and central Africa, and confers almost complete protection from P. vivax parasitemia (Miller et al., 1976; Howes et al., 2011). Together, these findings indicate that Plasmodium infections have impacted human health for millennia, but the prevailing view has been that this history goes back much further.

One long-standing hypothesis suggested that humans and chimpanzees each inherited P. falciparum-like infections from their common ancestor, and that these parasites co-evolved with their respective host species for millions of years (Escalante and Ayala, 1994). In contrast, P. vivax was believed to have arisen several hundred thousand years ago, following the cross-species transmission of a parasite from a macaque in southeastern Asia (Escalante et al., 2005; Jongwutiwes et al., 2005; Mu et al., 2005; Neafsey et al., 2012). However, both of these theories have recently been refuted following the characterization of a large number of additional Plasmodium parasites from African apes. Specifically, it is now clear that P. falciparum infection is relatively new for humans, which arose after the acquisition of a parasite from a gorilla, likely within the past 10,000 years (Liu et al., 2010a; Sundararaman et al., 2016). Similarly, P. vivax did not emerge in Asia, but represents a bottlenecked lineage that escaped out of Africa before the spread of Duffy negativity rendered African humans resistant to P. vivax (Liu et al., 2014). In this review, we describe the findings that led to this new understanding and summarize what is known about the epidemiology, vector tropism, zoonotic potential and pathogenicity of the ape precursors of the human parasites.

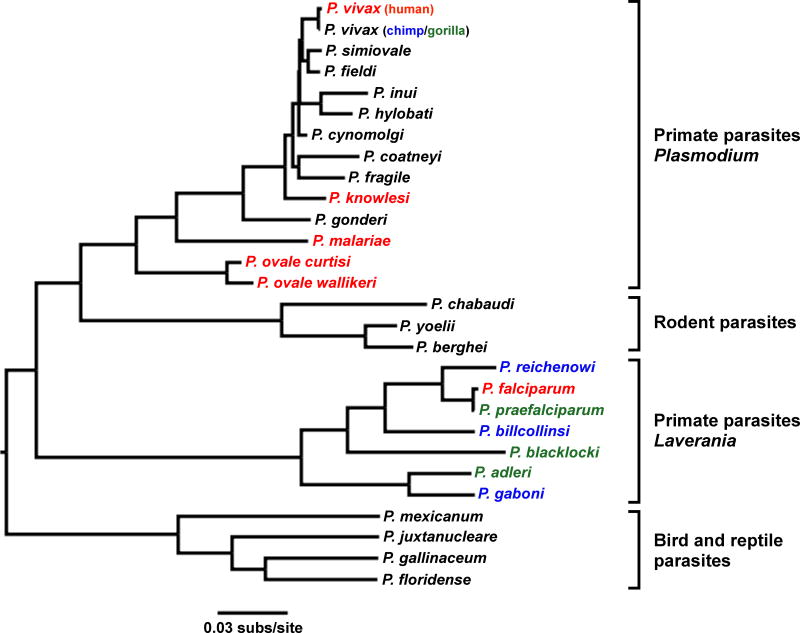

2. Early studies of ape Plasmodium infections

The first indication that African apes harbor Plasmodium infections was the finding of three morphologically distinct forms of parasites in the blood of wild-caught chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) in Cameroon (Reichenow, 1920). Microscopic characterization identified parasites from apes that resembled P. falciparum, Plasmodium malariae, and either Plasmodium ovale or (the similar) P. vivax in humans, suggesting the existence of distinct Plasmodium spp. which were classified as Plasmodium reichenowi, Plasmodium rhodaini and Plasmodium schwetzi, respectively (Sluiter et al., 1922; Brumpt, 1939). Moreover, P. falciparum and P. reichenowi were found to differ substantially from the other Plasmodium spp. in both life cycle and gametocyte morphology, prompting their placement in a separate subgenus, termed Laverania (Bray, 1958; Coatney et al., 1971). The existence of two divergent clades of malaria parasites infecting primates was subsequently confirmed when the various Plasmodium spp. were first molecularly characterized (Fig. 1). Comparing rRNA small subunit gene sequences, Escalante and Ayala (1994) showed that among the known species, P. falciparum and P. reichenowi were the closest relatives of each other, and that both were only distantly related to other Plasmodium spp. Assuming that rRNA gene sequences in Plasmodium spp. evolved at the same rate as had been estimated for some bacteria, it was inferred that P. falciparum and P. reichenowi had diverged ~10 million years ago, close to the time of the human-chimpanzee common ancestor. This led to the conclusion that parasites infecting humans and chimpanzees had co-diverged with their respective hosts (Escalante and Ayala, 1994). Due to a lack of preserved material, gene sequences from P. schwetzi and P. rhodaini were never determined, thus leaving their relationship to other malaria parasites open to question.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary relationships of Plasmodium spp. Colors highlight Plasmodium spp. that infect humans (red), chimpanzees (blue) and gorillas (green). Four groups of Plasmodium spp. are shown, with subgenus designations indicated for primate parasites. The phylogeny was estimated by maximum likelihood analysis of 2.4 kb of the mitochondrial genome; the scale bar indicates 0.03 substitutions per site.

Interest in ape Laverania infections was rekindled in 2009 when Ollomo and colleagues found parasites morphologically similar to P. reichenowi in the blood of two pet chimpanzees from Gabon (Ollomo et al., 2009). Analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences revealed that these parasites were related to, but divergent from, P. falciparum and P. reichenowi, suggesting the existence of a third Laverania sp. which they named Plasmodium gaboni (Ollomo et al., 2009). Follow-up studies of additional captive and wild apes confirmed a greater diversity of Laverania parasites, but interpretations differed as to the number of species and their host associations. Amplifying mtDNA and nuclear gene sequences of parasites from members of two chimpanzee subspecies, Rich and colleagues (2009) identified several distinct Laverania lineages, but chose to consider all of them as “P. reichenowi”, even though one of these new lineages corresponded to P. gaboni (Rich et al., 2009). In contrast, Krief and colleagues (2010) classified a similar diversity of chimpanzee parasites into three species, termed P. reichenowi, Plasmodium billcollinsi and Plasmodium billbrayi, where the latter corresponded to P. gaboni (Krief et al., 2010). These investigators also amplified P. falciparum mtDNA from the blood of captive bonobos (Pan paniscus), concluding that this ape species represents the likely source of the human infection (Krief et al., 2010). Finally, Prugnolle and colleagues developed non-invasive methods that permitted parasite detection in ape fecal samples, which identified diverse Laverania lineages not only in chimpanzees but also in western gorillas (Prugnolle et al., 2010). However, these investigators classified all chimpanzee parasites as either P. reichenowi or P. gaboni, and concluded that P. falciparum-like sequences found in fecal samples of wild-living western gorillas indicated ongoing transmission from humans to gorillas (Prugnolle et al., 2010). The consensus of these studies was that wild-living apes harbor a much greater diversity of Laverania parasites than previously recognized. However, there was disagreement concerning the number of ape Laverania spp. as well as the origin of P. falciparum, with some investigators implicating chimpanzees (Rich et al., 2009; Duval et al., 2010; Prugnolle et al., 2010) and others bonobos (Krief et al., 2010) as the likely original source of the parasites now infecting humans.

3. Six Laverania spp. in wild-living chimpanzees and gorillas

The seemingly discrepant results from these early studies were reconciled by comprehensive studies of Laverania infections in wild-living apes, which employed improved feces-based detection methods and targeted different regions of both organelle and nuclear parasite genomes (Liu et al., 2010a). One technical advance was the use of limiting dilution PCR (termed single genome amplification or SGA), which in contrast to standard (bulk) PCR precludes the generation of in vitro recombinants that confound phylogenetic analyses (Liu et al., 2010b). Using this approach to characterize the molecular epidemiology of ape malaria, Plasmodium infections were found to be widespread in both chimpanzees and western gorillas, including parasites that were closely related to human P. malariae, P. ovale and P. vivax (Liu et al., 2010a). However, the great majority of parasite sequences grouped within one of three chimpanzee-specific or three gorilla-specific parasite lineages, with each clade being well supported and quite distinct from the others, pointing to the existence of six ape Laverania spp. (Fig. 1). Subsequent surveys of wild-living apes in Gabon (Boundenga et al., 2015) and Cote d’Ivoire (Kaiser et al., 2010) confirmed these findings, demonstrating that chimpanzees and western gorillas represent a substantial Laverania reservoir.

Fig. 2A summarizes the current knowledge concerning the geographic distribution and host species association of ape Laverania infections at over 100 field sites across sub-Saharan Africa (Kaiser et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a; De Nys et al., 2013; Boundenga et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). All chimpanzee subspecies, including western (Pan troglodytes verus), Nigeria-Cameroon (Pan troglodytes ellioti), central (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) and eastern (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) chimpanzees, as well as western lowland gorillas (G. g. gorilla) are endemically infected with Laverania parasites, with fecal detection rates ranging from 24% to 40% (Table 1). The true prevalence rates are likely to be considerably higher, since the amount of Laverania DNA that is shed in fecal samples is substantially less than that from replicating parasites in the blood (Liu et al., 2010a; Sundararaman et al., 2016). Although Cross River gorillas (Gorilla gorilla diehli), eastern lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri), and bonobos (in the wild) have appeared to be free of Laverania infections, the numbers of individuals tested from these potential hosts are still too small to draw definitive conclusions (Liu et al., 2010a).

Fig. 2.

Geographic distribution of (A) Laverania and (B) Plasmodium vivax infections in wild-living apes. Field sites are shown in relation to the ranges of the four subspecies of the common chimpanzee (inset: Pan troglodytes verus, black; Pan troglodytes ellioti, purple; Pan troglodytes troglodytes, magenta; Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, blue), the Cross River (Gorilla gorilla diehli, yellow stripe), western lowland (Gorilla gorilla gorilla, red stripe), and eastern lowland (Gorilla beringei graueri, cyan stripe) gorilla, as well as the bonobo (Pan paniscus, orange) in sub-Saharan Africa (Caldecott and Miles, 2005). Field sites are labeled by a two-letter code as previously reported (Liu et al., 2010a, 2014) or numbers (Boundenga et al., 2015), and those where ape malaria was detected are highlighted in yellow, with black, green or red lettering indicating that chimpanzees, gorillas, or both were infected. Triangles denote ape rescue centers and asterisks mosquito collection sites. Circles, squares and hexagons identify locations where fecal samples were collected from chimpanzees, gorillas or both species, respectively. Ovals indicate bonobo sites. At the TA and KB sites, blood and tissue samples were obtained from injured or deceased habituated chimpanzees (Kaiser et al., 2010; Krief et al., 2010; De Nys et al., 2013). Diamonds in (B) indicate the capture sites of ape P. vivax infected sanctuary chimpanzees (black border) and gorillas (green border), respectively, and a star denotes the location where a European forester became infected with ape P. vivax (Prugnolle et al., 2013). Data were compiled from published (Kaiser et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a, 2014, 2016; De Nys et al., 2013; Paupy et al., 2013; Prugnolle et al., 2013; Boundenga et al., 2015) and unpublished studies (Table 1). The full names and locations of all sites are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Feces-based prevalence estimates of Laverania and Plasmodium vivax infections in wild-living African apes.

| Species/subspecies |

Laveraniaa

|

P. vivaxb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field sites testedc |

Field sites positive |

Fecal samples tested |

Fecal samples positive |

% Infection rate (CI)d |

Field sites testedc |

Field sites positive |

Fecal samples tested |

Fecal samples positive |

% Infection rate (CI)d |

|

| Western chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus)e | 1 | 1 | 171 | 34 | 40 (31–50) | 1 | 1 | 171 | 2 | 4 (2–11) |

| Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti) | 15 | 7 | 148 | 21 | 29 (20–39) | 15 | 0 | 149 | 0 | 0 (0–4) |

| Central chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) | 47 | 31 | 1412 | 271 | 39 (36–42) | 25 | 11 | 1130 | 25 | 8 (6–10) |

| Eastern chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) | 33 | 17 | 1676 | 199 | 24 (20–28) | 34 | 10 | 1784 | 20 | 4 (3–6) |

| Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 (0–53) | 2 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 (0–8) |

| Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) | 49 | 38 | 1584 | 256 | 33 (30–36) | 22 | 13 | 1575 | 30 | 7 (5–9) |

| Eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) | 3 | 0 | 146 | 0 | 0 (0–4) | 4 | 1 | 189 | 2 | 4 (1–9) |

| Bonobo (Pan paniscus) | 4 | 0 | 161 | 0 | 0 (0–4) | 8 | 0 | 754 | 0 | 0 (0–1) |

Laverania infection results were compiled from five studies (Kaiser et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; De Nys et al., 2013; Boundenga et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016) as well as recently obtained unpublished data from additional field sites, including BJ, BK, DJ, GA, GI, GM, GO, IK, KB, KY, MD, MG, MH, MK, MP, NY, SL, TK, UG (the full names and locations of these sites are provided in Supplementary Table S1).

Ape P. vivax infection results were compiled from four studies (Kaiser et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; De Nys et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014) as well as recently obtained unpublished data from additional field sites, including BG, GA, GI, KB, KY, MH, NY (the full names and locations of these sites are provided in Supplementary Table S1).

The location of field sites is shown in Fig. 2.

Infection rates were estimated for each ape species or subspecies based on the combined numbers of PCR-positive fecal samples per total number of fecal samples screened, but assuming similar levels of specimen degradation, redundant sampling and diagnostic test sensitivities across all studies (Liu et al., 2010, 2014). Since there is less Plasmodium DNA shed into fecal samples than can be detected in the blood, the values represent minimum estimates. Parentheses indicate 95% confidence intervals (CI). Results from chimpanzee blood samples collected in the Tai Forest (TA) and Kibale National Park (KB) are not included (Kaiser et al., 2010; Krief et al., 2010).

Fecal samples from P. t. verus were screened using pan-Plasmodium cytB primers, not Laverania- or P. vivax-specific PCR primers (Kaiser et al., 2010; De Nys et al., 2013).

Analyses of nearly 3,500 SGA-derived mt, apicoplast and nuclear DNA sequences from ape fecal and blood samples have confirmed the existence of six Laverania spp. (Figs. 1, 3). Of these, P. reichenowi, P. gaboni and P. billcollinsi have thus far only been identified in chimpanzees, while Plasmodium praefalciparum, Plasmodium blacklocki and Plasmodium adleri have only been found in western gorillas. All six Laverania spp. have been classified based on numerous SGA-derived organelle and nuclear gene sequences from many different field isolates (Liu et al., 2010a,, 2016). In addition, whole genome sequencing of P. reichenowi and P. gaboni parasites confirmed that they represent distinct species, with no evidence of interspecific hybridization (Otto et al., 2014; Sundararaman et al., 2016). While it has been argued that detection of parasite DNA in either feces or blood, in itself, is not proof of productive Plasmodium infection (Valkiunas et al., 2011), the high prevalence rates of Laverania infections (Table 1) and their widespread distribution (Fig. 2A) provide compelling evidence for significant ongoing transmission. Of note, Laverania parasites exhibit strict host specificity when infecting wild-living apes, including at field sites where all six species are co-circulating in sympatric chimpanzee and gorilla populations (octagons in Fig. 2A). SGA, which yields a proportional representation of all parasites present in a sample, failed to detect even minor fractions of parasites from the “wrong” species in more than 100 Laverania-infected apes (Liu et al., 2016). In contrast, host species specificity in captivity is not absolute (Duval et al., 2010; Pacheco et al., 2013), and so it will be of great interest to decipher to what extent host and/or vector biology contribute to host species restriction in the wild.

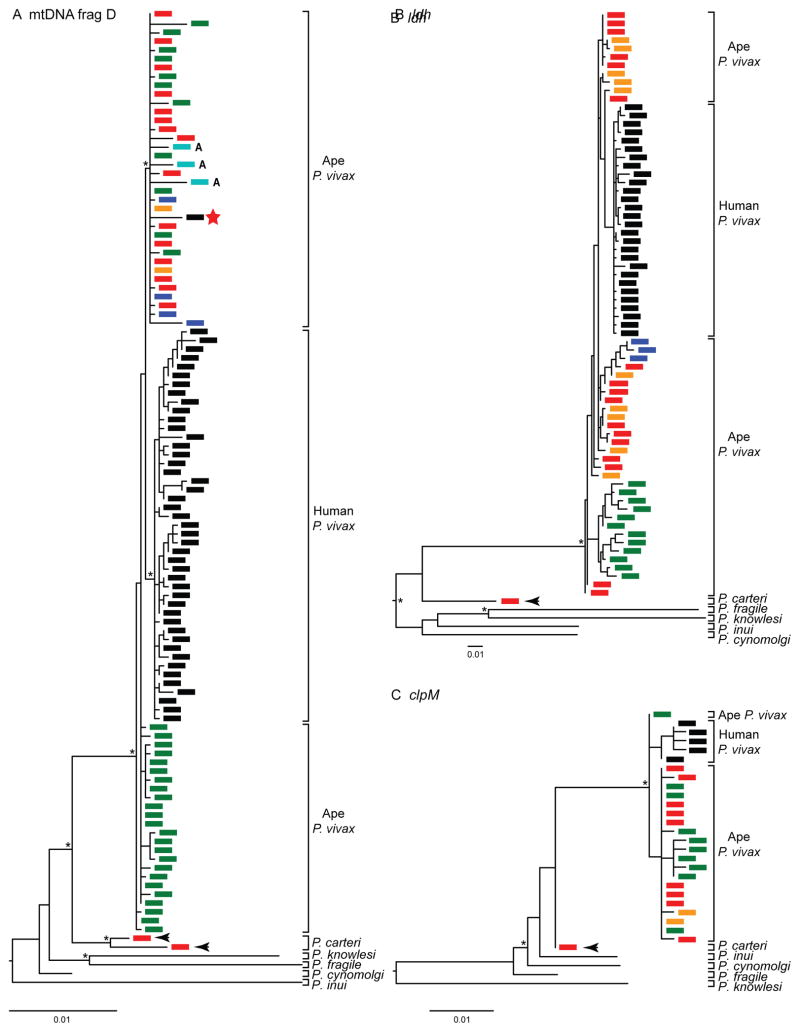

Fig. 3.

Evolutionary relationships of ape and human Laverania parasites. The phylogenetic relationships of (A) mitochondrial cytochrome B (cytB; 956 bp) and (B) nuclear lactate dehydrogenase (ldh; 772 bp) gene sequences, as well as (C) concatenated mitochondrial protein (CoxI/CoxIII/CytB; 981 amino acids) sequences are shown. Ape parasite sequences are colored according to their host species (Pan troglodytes verus, light blue; Pan troglodytes troglodytes, red; Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, dark blue; Pan troglodytes ellioti, orange; Gorilla gorilla gorilla, green), and human parasite reference sequences are shown in black. A black circle denotes the Plasmodium reichenowi PrCDC reference sequence (Otto et al., 2014) derived from a chimpanzee captured in the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) (Coatney et al., 1971). (C) Four Plasmodium falciparum sequences from captive bonobos (Krief et al., 2010) and one Plasmodium praefalciparum sequence from a captive greater spot-nosed monkey (Prugnolle et al., 2011) are shown in magenta and grey, respectively. Parentheses indicate Laverania spp. Phylogenies were generated using maximum likelihood methods. Asterisks at major nodes indicate bootstrap values ≥ 65%, and the scale bars represent (A, B) 0.01 nucleotide substitutions per site, or (C) 0.001 amino acid replacements per site, respectively. Sequences were combined from multiple studies (Kaiser et al., 2010; Krief et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a, 2016; Prugnolle et al., 2011).

4. Origin of P. falciparum in western gorillas

Characterization of the various ape Laverania spp. identified one lineage in western gorillas that was comprised of parasites that were nearly identical to P. falciparum (Liu et al., 2010a; Prugnolle et al., 2010). This was initially interpreted as indicating that human parasites can infect gorillas (Prugnolle et al., 2010). However, with the characterization of mtDNA sequences from large numbers of additional wild-living gorillas, it became apparent that all extant P. falciparum strains from humans fall within the radiation of these gorilla parasites (Liu et al., 2010a). Analyses of both mt (Fig. 3A) and nuclear (Fig. 3B) sequences confirmed these relationships, indicating that human P. falciparum resulted from the cross-species transmission of a parasite that had previously diversified in gorillas. This gorilla parasite lineage has been named P. praefalciparum to indicate its role in the origin of P. falciparum. To investigate how often P. praefalciparum crossed the species barrier to humans, we constructed a phylogenetic tree from concatenated mt protein sequences of these and closely related P. reichenowi parasites, which yielded evidence for only a single transmission event (Fig. 3C). These findings are consistent with results from epidemiological surveys in Cameroon and Gabon, which demonstrated that humans living in the immediate vicinity of wild-living chimpanzees and gorillas do not harbor ape Laverania parasites (Sundararaman et al., 2013; Delicat-Loembet et al., 2015). Thus, P. praefalciparum parasites appear incapable of infecting humans, suggesting that the particular gorilla parasite strain that was able to cross the host species barrier must have carried one or more highly unusual mutations that conferred an ability to colonize humans.

Although alternative hypotheses concerning the origin of P. falciparum have been proposed, none has stood the test of time. For example, the finding of a P. praefalciparum infection in a greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans) (Fig. 3C) was taken to indicate that P. falciparum could have originated in monkeys (Prugnolle et al., 2011). However, this theory ignored the fact that P. praefalciparum sequences had been amplified from numerous wild-living gorillas at 11 different field sites up to 750 km apart, whereas only a single captive infected monkey was reported (Sharp et al., 2011). Indeed, subsequent testing of nearly 300 wild-caught greater spot-nosed monkeys failed to identify a single P. praefalciparum infection, indicating that this monkey species is not a natural reservoir for this parasite (Ayouba et al., 2012). Similarly, amplification of P. falciparum sequences from captive bonobos was taken to indicate that the human malaria parasite originated in this ape species (Krief et al., 2010). However, phylogenetic analysis of these sequences revealed that they were completely interspersed with human P. falciparum (Fig. 3C), which together with the finding of drug resistance mutations in the bonobo parasites (Krief et al., 2010), indicated that these apes had acquired parasites from the local human population. This is not without precedent, since human P. falciparum has on occasion been found to infect chimpanzees in captivity (Duval et al., 2010; Pacheco et al., 2013).

5. Emergence of P. falciparum in humans

Plasmodium falciparum has long been suspected to exhibit unusually low levels of genetic diversity (Rich et al., 1998), but the underlying causes have remained unclear. Recent genome-wide comparisons of the chimpanzee parasites P. gaboni and P. reichenowi have shown that their within-species genetic diversity is approximately 10-fold higher than that seen in P. falciparum (Sundararaman et al., 2016). Thus, the extremely low diversity among extant P. falciparum strains is not a general characteristic of Laverania parasites. Recent selective sweeps of drug resistance mutations have reduced levels of polymorphism in P. falciparum, but because resistant and sensitive strains continue to recombine in mosquitoes, diversity has only been reduced in the immediate vicinity of the selected loci (Nair et al., 2003; Volkman et al., 2007). Instead, the greatly reduced level of diversity across the entire P. falciparum genome most likely resulted from a recent severe population bottleneck, which is most plausibly explained by the gorilla-to-human cross-species transmission event.

Previous attempts to date the last common ancestor of P. falciparum strains have yielded estimates of up to several hundred thousand years ago (Hughes and Verra, 2001; Pacheco et al., 2011; Neafsey et al., 2012), but all made assumptions concerning the Plasmodium molecular clock that are difficult to justify. In contrast, others have proposed a much shorter time scale, arguing that the low probability of maintaining endemic P. falciparum infections in human hunter-gatherer populations (Livingstone, 1958), together with estimates of the age of P. falciparum resistance mutations in Africa (Hedrick, 2011), favor a much more recent emergence (Carter and Mendis, 2002). From a comparison of 12 strains from different countries in Africa and Asia, the average diversity of P. falciparum at four-fold degenerate sites (which should be neutral and thus reflect mutation rates) was estimated to be 8 × 10−4 per site (Sundararaman et al., 2016). Published mutation rates for P. falciparum are in the range 1–10 × 10−9 mutations per site per replication cycle (Paget-McNicol and Saul, 2001; Lynch, 2010; Bopp et al., 2013), and it can be deduced from the P. falciparum life cycle that parasites are likely to undergo at least 200 replication cycles per year, even assuming varying lengths of time that the parasites spend in either the vector or the mammalian host. This suggests that the observed level of genetic diversity in P. falciparum could have readily accumulated within the past 10,000 years.

6. Allelic dimorphism in ape Laverania spp

Nearly 30 years ago, it was recognized that a gene (now called msp-1) encoding a merozoite surface protein exists as two highly divergent alleles in P. falciparum, with recombination suppressed over much of the length of the gene (Tanabe et al., 1987). Similar allelic dimorphism was subsequently found for other genes encoding merozoite surface proteins including msp-2, msp-3 and msp-6 (Roy et al., 2008). The extent of divergence is extreme: for example, large regions of the two msp-1 alleles in P. falciparum are more different from each other than one of those alleles is from the one msp-1 allele so far found in P. gaboni, suggesting that the P. falciparum alleles diverged prior to the last common ancestor of extant Laverania spp. (Roy, 2015). This suggests some form of selection that maintains divergent allelic types over very long periods of time, analogous, for example, to the trans-specific polymorphism of self-incompatibility alleles in a family of flowering plants (Solanaceae), which may date to more than 30 million years (Myr) ago (Ioerger et al., 1990). Although the mechanism(s) that maintain the dimorphic msp alleles in P. falciparum remain largely unknown (Roy and Ferreira, 2015), some genes appear to be under balancing selection (Ochola et al., 2010; Amambua-Ngwa et al., 2012) and represent targets of allele type-specific antibody responses that confer protective immunity against malaria (Polley et al., 2007; Tetteh et al., 2013).

For msp-1, msp-3 and msp-6, we have found evidence for both allelic types in P. praefalciparum (Liu, W., Sundararaman, S.A., Loy, D.E., Learn, G.H., Li, Y., Plenderleith, L.J., Ndjango, J.B., Speede, S., Rayner, J.C., Peeters, M., Hahn, B.H., Sharp, P.M. 2015. On the origins of allelic dimorphism of the Plasmodium falciparum msp-1 and msp-6 genes. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. (ASTMH), 64th Annual Meeting (Philadelphia, PA, USA). However, it is unclear how two highly divergent alleles, at a number of different loci, survived the genetic bottleneck at the origin of P. falciparum. Sporozoites, which are injected into the human host by the mosquito, are haploid. Transmission from gorilla to human of two dimorphic alleles could occur in a single event, if heterozygous oocytes in the mosquito generated two types of sporozoites present in the same inoculum. However, the transmission of divergent alleles of multiple genes would require that oocytes were simultaneously heterozygous at all loci that are now dimorphic in P. falciparum. Alternatively, backcrossing of human parasites to gorilla parasites, in the immediate aftermath of the initial cross-species transmission event, but before they became isolated, could lead to the transfer of additional alleles to humans. Regardless of the mechanism, however, any proposed scenario involving the transfer of multiple alleles at multiple msp loci must at the same time explain the paucity of genetic variation seen elsewhere in the genome (Sundararaman et al., 2016). It would require there to have been very strong selection retaining both dimorphic alleles at the various loci, in the face of extreme random genetic drift (perhaps due to a very small number of initial human hosts) affecting all other loci. Characterization of the extent of allelic dimorphism across other Laverania spp., together with the corresponding host immune responses, may shed more light on this puzzle.

7. A sylvatic reservoir of P. vivax

Although early studies of ape blood and fecal samples indicated that chimpanzees and gorillas harbor P. vivax-like parasites, the number of sequences recovered was too limited to draw definitive conclusions (Kaiser et al., 2010; Krief et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a; Prugnolle et al., 2013). As for Laverania parasites, elucidation of the molecular epidemiology of P. vivax in apes required a comprehensive analysis of wild-living populations across central Africa (Liu et al., 2014). Table 1 and Fig. 2B summarize available data from 97 field sites, showing that P. vivax is relatively common among central and eastern chimpanzees as well as western lowland gorillas, which together represent a considerable sylvatic P. vivax reservoir (Kaiser et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a, 2014; De Nys et al., 2013). However, amplification of P. vivax DNA sequences from fecal samples was considerably less efficient than from blood samples, most likely reflecting much lower parasite loads in fecal samples compared with blood (Liu et al., 2014). Thus, the observed feces-based infection rates, which ranged from 4% to 8% for the various ape species and subspecies (Table 1), are expected to greatly underestimate the actual prevalence rates, perhaps by as much as an order of magnitude. The low sensitivity of fecal parasite detection may also explain why P. vivax has not yet been detected in wild-living Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees, Cross River gorillas or bonobos. Indeed, P. vivax-like sequences were readily amplified from the blood of captive Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees, indicating that this subspecies is susceptible to P. vivax infection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evolutionary relationships of ape and human Plasmodium vivax parasites. Phylogenies were derived from (A) mitochondrial (mt)DNA fragment D (2,539 bp), (B) nuclear DNA (ldh gene; 711 bp), and (C) apicoplast DNA (clpM gene; 574 bp). Parasite sequences are colored according to their host species (Pan troglodytes troglodytes, red; Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, dark blue; Pan troglodytes ellioti, orange; Gorilla gorilla gorilla, green; human, black); the red star denotes a parasite from a European person who worked in an African forest. Mosquito (Anopheles moucheti) derived sequences are shown in cyan (and denoted with ‘A’). Reference sequences for Plasmodium cynomolgi, Plasmodium inui, Plasmodium fragile and Plasmodium knowlesi are indicated. A lineage of parasite sequences from wild chimpanzees, which is related to ape and human P. vivax, likely represents a new Plasmodium sp. which has been designated Plasmodium carteri (black arrows). Phylogenies were generated using maximum likelihood methods. Asterisks at major nodes indicate bootstrap values ≥ 65%, and the scale bars represent 0.01 nucleotide substitutions per site. Sequences were combined from multiple studies (Krief et al., 2010; Paupy et al., 2013; Prugnolle et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014).

Phylogenetic analyses of SGA-derived sequences showed that ape and human P. vivax were very closely related. However, chimpanzee- and gorilla-derived parasites exhibited greater genetic diversity than even the most geographically diverse human P. vivax strains. In phylogenetic trees of mt (Fig. 4A), nuclear (Fig. 4B), and apicoplast (Fig. 4C) sequences, human P. vivax sequences formed a single lineage within the radiation of the ape parasites. In contrast, parasite sequences derived from chimpanzee and gorilla samples were interspersed, suggesting that P. vivax circulates freely between these two ape species. Of note, analysis of nearly 1,000 bushmeat samples failed to identify related sequences in samples from any of 16 different monkey species, strongly suggesting that P. vivax is restricted to African apes (Liu et al., 2014).

8. African origin of human P. vivax

Until recently, the closest known relative of P. vivax was a parasite, Plasmodium cynomolgi, which infects macaques in Asia (Tachibana et al., 2012). In phylogenetic trees, P. vivax and P. cynomolgi fall within a clade of parasites that includes at least eight other Plasmodium spp. infecting southeast Asian primates (Fig. 1). The consensus view has thus been that P. vivax emerged in southeastern Asia following the cross-species transmission of a macaque parasite (Escalante et al., 2005; Jongwutiwes et al., 2005; Mu et al., 2005; Neafsey et al., 2012). However, this hypothesis has always been at odds with two other observations. First, the high prevalence of the Duffy-negative phenotype in sub-Saharan Africans, which suggested that this mutation arose in response to prolonged selection pressure from P. vivax (Carter, 2003) rather than another unidentified pathogen (Livingstone, 1984). Second, modern humans did not arrive in Asia until approximately 60,000 years ago (Mellars, 2006); yet, P. vivax has likely diverged from macaque parasites much earlier than this (Escalante et al., 2005; Jongwutiwes et al., 2005; Mu et al., 2005; Neafsey et al., 2012). Thus, P. vivax would have had a rather convoluted history, requiring transmission from macaques to an earlier hominin such as Homo erectus, followed by its diversification in that host before numerous lineages were transmitted to modern humans after they emerged from Africa. The discovery of P. vivax in large numbers of chimpanzees and gorillas now resolves these inconsistencies, providing compelling evidence for an African, rather than an Asian, origin of human P. vivax.

The phylogenetic relationships of organelle as well as nuclear gene sequences indicate that all extant human P. vivax strains form a monophyletic clade within the radiation of ape parasites (Fig. 4). This could be interpreted to mean that P. vivax originated in humans following a single transmission event. However, the lack of host specificity of ape P. vivax in natural settings (Liu et al., 2014), together with the finding of a human infection with ape P. vivax (Prugnolle et al., 2013), argues against this theory. Instead, it is much more likely that extant human P. vivax represents a lineage that survived after spreading out of Africa. This scenario explains the reduced diversity of the human parasites as resulting from an out-of-Africa bottleneck, as seen in P. falciparum (Conway et al., 2000; Tanabe et al., 2010) and in humans themselves (Ramachandran et al., 2005). Human P. vivax strains that are currently found in Madagascar and parts of Africa are likely the result of a reintroduction of this parasite from Asia (Culleton and Carter, 2012).

While it could be argued that the ape P. vivax was brought to Africa by humans who migrated from Asia (Prugnolle et al., 2013), this hypothesis has been refuted by sequences indicating the existence of a related, but distinct, Plasmodium sp. that also infects African apes. This Plasmodium sp. which is apparent in trees of mt, nuclear and apicoplast sequences (Fig. 4), has been found in chimpanzees from two different locations in Cameroon (the BQ and DG field sites in Fig. 2) and represents the closest known relative of P. vivax. The most parsimonious interpretation of this finding is that the common ancestor of these two species was in Africa, indicating that the lineage existed there for a long time before P. vivax arose as a distinct species (Fig. 4). We propose to designate this newly described species Plasmodium carteri, in honor of Richard Carter, who has long championed the hypothesis that P. vivax originated in Africa (Carter, 2003; Culleton and Carter, 2012).

9. Mosquito vectors of ape Plasmodium spp

Identifying the mosquito vectors that transmit ape Plasmodium parasites is critical for understanding their host specificity and zoonotic potential. Initial studies of whole mosquito DNA identified P. praefalciparum in Anopheles moucheti, while ape P. vivax was found in both A. moucheti and Anopheles vinckei, although these mosquitoes were analyzed with molecular tools that were unsuitable to differentiate between parasite stages (Paupy et al., 2013; Prugnolle et al., 2013). A subsequent study screened dissected salivary glands for parasites, and demonstrated that A. vinckei, A. moucheti and Anopheles marshallii are transmitting vectors of ape Plasmodium species (Makanga et al., 2016). Anopheles vinckei was found to be most frequently infected, harboring P. vivax-like, P. malariae-like, and Laverania spp., and carried gorilla as well as chimpanzee parasites (Makanga et al., 2016). Moreover, human landing catches showed that all three Anopheles spp. had the propensity to bite humans, indicating that they could serve as bridge vectors for human infection (Makanga et al., 2016). Although these three Anopheles spp. may not represent the entirety of vectors capable of transmitting ape Plasmodium parasites, it seems clear that the strict host specificity of Laverania spp. in wild-living ape populations cannot be explained by mosquitoes that exclusively feed on chimpanzees or gorillas. It is likely that P. praefalciparum was first transmitted to humans by one of these sylvatic vectors, but the subsequent dispersal of the newly created P. falciparum required adaptation to Anopheles gambiae, which is the main human transmission vector (Molina-Cruz and Barillas-Mury, 2016). It will thus be important to determine to what extent ape Laverania parasites can productively infect Anopheles spp. that are more domesticated (Molina-Cruz and Barillas-Mury, 2016).

10. Zoonotic potential of ape parasites

Despite the identification of suitable bridge vectors, both experimental transmission and molecular epidemiological studies indicate that ape Laverania parasites do not normally cause blood stage infections in humans. Attempts to inoculate humans with a parasite identified as “P. reichenowi” over 100 years ago did not result in parasitemia (Blacklock and Adler, 1922). More importantly, two recent field studies conducted in rural Cameroon and Gabon failed to identify ape Laverania parasites in the blood of humans living in close proximity to infected chimpanzees and gorillas (Sundararaman et al., 2013; Delicat-Loembet et al., 2015). In contrast, ape P. vivax has been shown to cause clinical malaria in Duffy-positive humans, as exemplified by the case of a Caucasian male who acquired this infection after working for 18 days in a forest in the Central African Republic (Fig. 2B). Parasite sequences amplified from this individual’s blood did not fall within the human P. vivax lineage, but instead clustered with parasites obtained from wild-living chimpanzees and gorillas (Fig. 4A), confirming acquisition by cross-species transmission from a wild ape (Prugnolle et al., 2013). Similarly, “P. schwetzi” was experimentally transmitted from apes to humans and must have represented ape P. vivax in at least some cases, since only Caucasians, but not Africans, became blood-stage infected, likely because the latter were Duffy-negative (Contacos et al., 1970). Together, these data indicate that ape Laverania parasites do not switch between host species, except under highly unusual circumstances, while ape P. vivax is much less host-specific and has the potential to infect Duffy-positive humans, suggesting that human and ape P. vivax parasites represent a single species. Although P. praefalciparum apparently crossed the species barrier to humans only once, it will be important to elucidate the host, vector and/or ecological barriers that have prevented additional ape Laverania transmissions. Since ape P. vivax is substantially more diverse than human P. vivax, it will be important to determine whether ape parasites are biologically more versatile. Moreover, emergence of ape P. vivax should be monitored in areas of Africa where an influx of Duffy-positive humans through commerce and travel coincides with forest encroachment and ape habitat destruction.

11. Natural history of ape Plasmodium infections

Although P. falciparum and P. vivax are highly pathogenic in humans, the disease causing potential of their ape relatives remains largely unknown. Given the high prevalence (Table 1) and wide distribution of both Laverania and P. vivax infections among chimpanzees and gorillas (Fig. 2), it is highly unlikely that they cause severe disease and malaria-related deaths in many animals. However, studies of habituated chimpanzees in the Tai National Forest in Cote d’Ivoire revealed higher fecal parasite burdens in both young (De Nys et al., 2013) and pregnant (De Nys et al., 2014) animals, similar to what has been described in humans in malaria endemic regions. Moreover, a recent report of an initially Plasmodium naive chimpanzee, who was introduced into a sanctuary where ape Laverania infections were endemic, showed that P. reichenowi can cause high parasitemia associated with fever and anemia (Herbert et al., 2015). In contrast, other captive chimpanzees in African sanctuaries that tested positive for Laverania or P. vivax sequences in their blood or fecal samples, were asymptomatic and blood smear negative (Herbert et al., 2015; Sundararaman et al., 2016). Thus, it seems clear that Plasmodium infections can be pathogenic in apes; however, like humans, apes seem to develop resistance to life threatening malaria in areas of intense parasite transmission.

12. Conclusions and perspectives

Although ape Plasmodium parasites were first identified nearly 100 years ago, it is only very recently that the complexities of their evolutionary relationships, geographic distribution, prevalence rates, and mammalian host and vector associations have been elucidated. While the evolutionary origins of human P. falciparum and P. vivax have now been clarified, nothing is known about the mechanistic processes that led to their emergence; yet, such information is critical to understanding how ape parasites crossed the species barrier and whether such events are likely to occur again. The lack of in vitro culture systems poses a significant challenge to the functional analysis of ape Plasmodium parasites, but whole genome sequencing, even from suboptimal specimens such as subpatently infected unprocessed blood, represents a critical first step towards understanding their biology (Otto et al., 2014; Sundararaman et al., 2016). Such analyses have already revealed a number of unexpected findings such as horizontal transfer of invasion genes among ape Laverania parasite species (Sundararaman et al., 2016). The genome sequences of additional parasites, in particular P. praefalciparum and ape P. vivax, will provide templates for mechanistic studies and in vitro genome manipulations to compare the function of key proteins among the various ape and human Plasmodium spp. Population genomic studies of ape Laverania parasites may also inform ongoing malaria vaccine development efforts by identifying antigens that are under strong immune selection pressure in apes as well as humans (Ochola et al., 2010; Amambua-Ngwa et al., 2012; Tetteh et al., 2013). In this context, it will be important to further characterize the transmitting vectors of ape Plasmodium parasites and assess to what extent humans are exposed to these parasites through the bites of infected mosquitoes. A careful analysis of antibody responses to preerythrocytic parasite stages could address this question. Finally, P. ovale- and P. malariae-like sequences have been detected in African great apes (Duval et al., 2010; Kaiser et al., 2010; Krief et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a; Boundenga et al., 2015), and additional work is required to ascertain the relationship of these parasites to their human counterparts. In general, knowledge gained from comparative population and genomic studies of ape parasites will provide new insight into the biology and pathogenesis of human P. falciparum and P. vivax, and will inform malaria eradication efforts by identifying potential zoonotic threats.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Chimpanzees and gorillas harbor six Laverania spp. as well as Plasmodium vivax

Plasmodium falciparum arose in humans after the acquisition of the parasite from a gorilla

Plasmodium vivax is a bottlenecked parasite lineage that originated in African apes

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Carter for helpful discussions and Shivani Sethi for artwork and manuscript preparation. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, USA, R01 AI 091595, R01 AI 058715, R01 AI 120810, R37 AI 050529, T32 AI 007532, P30 AI 045008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amambua-Ngwa A, Tetteh KK, Manske M, Gomez-Escobar N, Stewart LB, Deerhake ME, Cheeseman IH, Newbold CI, Holder AA, Knuepfer E, Janha O, Jallow M, Campino S, Macinnis B, Kwiatkowski DP, Conway DJ. Population genomic scan for candidate signatures of balancing selection to guide antigen characterization in malaria parasites. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayouba A, Mouacha F, Learn GH, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Rayner JC, Sharp PM, Hahn BH, Delaporte E, Peeters M. Ubiquitous Hepatocystis infections, but no evidence of Plasmodium falciparum-like malaria parasites in wild greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, Battle KE, Moyes CL, Henry A, Eckhoff PA, Wenger EA, Briet O, Penny MA, Smith TA, Bennett A, Yukich J, Eisele TP, Griffin JT, Fergus CA, Lynch M, Lindgren F, Cohen JM, Murray CL, Smith DL, Hay SI, Cibulskis RE, Gething PW. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature15535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklock B, Adler S. A parasite resembling Plasmodium falciparum in a chimpanzee. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1922;XVI:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bopp SER, Manary MJ, Bright AT, Johnston GL, Dharia NV, Luna FL, McCormack S, Plouffe D, McNamara CW, Walker JR, Fidock DA, Denchi EL, Winzeler EA. Mitotic evolution of Plasmodium falciparum shows a stable core genome but recombination in antigen families. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boundenga L, Ollomo B, Rougeron V, Mouele LY, Mve-Ondo B, Delicat-Loembet LM, Moukodoum ND, Okouga AP, Arnathau C, Elguero E, Durand P, Liegeois F, Boue V, Motsch P, Le Flohic G, Ndoungouet A, Paupy C, Ba CT, Renaud F, Prugnolle F. Diversity of malaria parasites in great apes in Gabon. Malar J. 2015;14:111. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0622-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RS. Studies on malaria in chimpanzees VI. Laverania falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:20–24. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumpt E. Les parasites du paludisme des chimpanzes. C R Soc Bio. 1939;130:837–840. [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott JO, Miles L. World Atlas of Great Apes and their Conservation. University of California Press; Berkley, California, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. Speculations on the origins of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:214–219. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Mendis KN. Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:564–594. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.564-594.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatney GR, Collins WE, Warren M, Contacos PG. The Primate Malarias. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1971. http://phsource.us/PH/PARA/Book/primate_24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Contacos PG, Coatney GR, Orihel TC, Collins WE, Chin W, Jeter MH. Transmission of Plasmodium schwetzi from the chimpanzee to man by mosquito bite. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:190–195. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway DJ, Fanello C, Lloyd JM, Al-Joubori BM, Baloch AH, Somanath SD, Roper C, Oduola AM, Mulder B, Povoa MM, Singh B, Thomas AW. Origin of Plasmodium falciparum malaria is traced by mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culleton R, Carter R. African Plasmodium vivax: distribution and origins. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nys HM, Calvignac-Spencer S, Boesch C, Dorny P, Wittig RM, Mundry R, Leendertz FH. Malaria parasite detection increases during pregnancy in wild chimpanzees. Malar J. 2014;13:413. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nys HM, Calvignac-Spencer S, Thiesen U, Boesch C, Wittig RM, Mundry R, Leendertz FH. Age-related effects on malaria parasite infection in wild chimpanzees. Biol Lett. 2013;9:20121160. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delicat-Loembet L, Rougeron V, Ollomo B, Arnathau C, Roche B, Elguero E, Moukodoum ND, Okougha AP, Mve Ondo B, Boundenga L, Houze S, Galan M, Nkoghe D, Leroy EM, Durand P, Paupy C, Renaud F, Prugnolle F. No evidence for ape Plasmodium infections in humans in Gabon. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval L, Fourment M, Nerrienet E, Rousset D, Sadeuh SA, Goodman SM, Andriaholinirina NV, Randrianarivelojosia M, Paul RE, Robert V, Ayala FJ, Ariey F. African apes as reservoirs of Plasmodium falciparum and the origin and diversification of the Laverania subgenus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10561–10566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Ayala FJ. Phylogeny of the malarial genus Plasmodium, derived from rRNA gene sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11373–11377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Freeland DE, Poe AC, Durrego E, Collins WE, Lal AA. A monkey’s tale: The origin of Plasmodium vivax as a human malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1980–1985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409652102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. Population genetics of malaria resistance in humans. Heredity (Edinb) 2011;107:283–304. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A, Boundenga L, Meyer A, Moukodoum DN, Okouga AP, Arnathau C, Durand P, Magnus J, Ngoubangoye B, Willaume E, Ba CT, Rougeron V, Renaud F, Ollomo B, Prugnolle F. Malaria-like symptoms associated with a natural Plasmodium reichenowi infection in a chimpanzee. Malar J. 2015;14:220. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes RE, Patil AP, Piel FB, Nyangiri OA, Kabaria CW, Gething PW, Zimmerman PA, Barnadas C, Beall CM, Gebremedhin A, Menard D, Williams TN, Weatherall DJ, Hay SI. The global distribution of the Duffy blood group. Nat Commun. 2011;2:266. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Verra F. Very large long-term effective population size in the virulent human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Biol Sci. 2001;268:1855–1860. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioerger TR, Clark AG, Kao TH. Polymorphism at the self-incompatibility locus in Solanaceae predates speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9732–9735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongwutiwes S, Putaporntip C, Iwasaki T, Ferreira MU, Kanbara H, Hughes AL. Mitochondrial genome sequences support ancient population expansion in Plasmodium vivax. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1733–1739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser M, Lowa A, Ulrich M, Ellerbrok H, Goffe AS, Blasse A, Zommers Z, Couacy-Hymann E, Babweteera F, Zuberbuhler K, Metzger S, Geidel S, Boesch C, Gillespie TR, Leendertz FH. Wild chimpanzees infected with 5 Plasmodium species. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1956–1959. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krief S, Escalante AA, Pacheco MA, Mugisha L, Andre C, Halbwax M, Fischer A, Krief JM, Kasenene JM, Crandfield M, Cornejo OE, Chavatte JM, Lin C, Letourneur F, Gruner AC, McCutchan TF, Renia L, Snounou G. On the diversity of malaria parasites in African apes and the origin of Plasmodium falciparum from bonobos. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000765. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, Ndjango JB, Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Locatelli S, Gonder MK, Kranzusch PJ, Walsh PD, Delaporte E, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Georgiev AV, Muller MN, Shaw GM, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Rayner JC, Hahn BH. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature. 2010a;467:420–425. doi: 10.1038/nature09442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Li Y, Peeters M, Rayner JC, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. Single genome amplification and direct amplicon sequencing of Plasmodium spp. DNA from ape fecal specimens. Protocol Exchange. 2010b doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Li Y, Shaw KS, Learn GH, Plenderleith LJ, Malenke JA, Sundararaman SA, Ramirez MA, Crystal PA, Smith AG, Bibollet-Ruche F, Ayouba A, Locatelli S, Esteban A, Mouacha F, Guichet E, Butel C, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Inogwabini BI, Ndjango JB, Speede S, Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Gonder MK, Kranzusch PJ, Walsh PD, Georgiev AV, Muller MN, Piel AK, Stewart FA, Wilson ML, Pusey AE, Cui L, Wang Z, Farnert A, Sutherland CJ, Nolder D, Hart JA, Hart TB, Bertolani P, Gillis A, LeBreton M, Tafon B, Kiyang J, Djoko CF, Schneider BS, Wolfe ND, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Delaporte E, Carter R, Culleton RL, Shaw GM, Rayner JC, Peeters M, Hahn BH, Sharp PM. African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3346. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Sundararaman SA, Loy DE, Learn GH, Li Y, Plenderleith LJ, Ndjango J-BN, Speede S, Atencia R, Cox D, Shaw GM, Ayouba A, Peeters M, Rayner JC, Hahn BH, Sharp PM. Multigenomic delineation of Plasmodium species of Laverania subgenus infecting wild-living chimpanzees and gorillas. Genome Biol Evol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone FB. Anthropological implications of sickle cell gene distribution in west Africa Am. Anthropol. 1958;60:533–562. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone FB. The Duffy blood groups, vivax malaria, and malaria selection in human populations: a review. Hum Biol. 1984;56:413–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 2010;26:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanga B, Yangari P, Rahola N, Rougeron V, Elguero E, Boundenga L, Moukodoum ND, Okouga AP, Arnathau C, Durand P, Willaume E, Ayala D, Fontenille D, Ayala FJ, Renaud F, Ollomo B, Prugnolle F, Paupy C. Ape malaria transmission and potential for ape-to-human transfers in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603008113. 201603008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellars P. Going east: new genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia. Science. 2006;313:796–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1128402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Cruz A, Barillas-Mury C. Mosquito vectors of ape malarias: another piece of the puzzle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:5153–5154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604913113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu J, Joy DA, Duan J, Huang Y, Carlton J, Walker J, Barnwell J, Beerli P, Charleston MA, Pybus OG, Su XZ. Host switch leads to emergence of Plasmodium vivax malaria in humans. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1686–1693. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S, Williams JT, Brockman A, Paiphun L, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Guthmann JP, Smithuis FM, Hien TT, White NJ, Nosten F, Anderson TJ. A selective sweep driven by pyrimethamine treatment in southeast asian malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1526–1536. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neafsey DE, Galinsky K, Jiang RH, Young L, Sykes SM, Saif S, Gujja S, Goldberg JM, Young S, Zeng Q, Chapman SB, Dash AP, Anvikar AR, Sutton PL, Birren BW, Escalante AA, Barnwell JW, Carlton JM. The malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax exhibits greater genetic diversity than Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1046–1050. doi: 10.1038/ng.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochola LI, Tetteh KK, Stewart LB, Riitho V, Marsh K, Conway DJ. Allele frequency-based and polymorphism-versus-divergence indices of balancing selection in a new filtered set of polymorphic genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:2344–2351. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollomo B, Durand P, Prugnolle F, Douzery E, Arnathau C, Nkoghe D, Leroy E, Renaud F. A new malaria agent in African hominids. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000446. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto TD, Rayner JC, Bohme U, Pain A, Spottiswoode N, Sanders M, Quail M, Ollomo B, Renaud F, Thomas AW, Prugnolle F, Conway DJ, Newbold C, Berriman M. Genome sequencing of chimpanzee malaria parasites reveals possible pathways of adaptation to human hosts. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4754. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Battistuzzi FU, Junge RE, Cornejo OE, Williams CV, Landau I, Rabetafika L, Snounou G, Jones-Engel L, Escalante AA. Timing the origin of human malarias: the lemur puzzle. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Cranfield M, Cameron K, Escalante AA. Malarial parasite diversity in chimpanzees: the value of comparative approaches to ascertain the evolution of Plasmodium falciparum antigens. Malar J. 2013;12:238. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paget-McNicol S, Saul A. Mutation rates in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 2001;122:497–505. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001007739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupy C, Makanga B, Ollomo B, Rahola N, Durand P, Magnus J, Willaume E, Renaud F, Fontenille D, Prugnolle F. Anopheles moucheti and Anopheles vinckei are candidate vectors of ape Plasmodium parasites, including Plasmodium praefalciparum in Gabon. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley SD, Tetteh KK, Lloyd JM, Akpogheneta OJ, Greenwood BM, Bojang KA, Conway DJ. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 3 is a target of allele-specific immunity and alleles are maintained by natural selection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:279–287. doi: 10.1086/509806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prugnolle F, Durand P, Neel C, Ollomo B, Ayala FJ, Arnathau C, Etienne L, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Nkoghe D, Leroy E, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Renaud F. African great apes are natural hosts of multiple related malaria species, including Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1458–1463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914440107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prugnolle F, Ollomo B, Durand P, Yalcindag E, Arathau C, Elguero E, Berry A, Pourrut X, Gonzalez JP, Nkoghe D, Akiana J, Verrier D, Leroy E, Ayala FJ, Renaud F. African monkeys are infected by Plasmodium falciparum nonhuman primate-specific strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11948–11953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109368108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prugnolle F, Rougeron V, Becquart P, Berry A, Makanga B, Rahola N, Arnathau C, Ngoubangoye B, Menard S, Willaume E, Ayala FJ, Fontenille D, Ollomo B, Durand P, Paupy C, Renaud F. Diversity, host switching and evolution of Plasmodium vivax infecting African great apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8123–8128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306004110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Deshpande O, Roseman CC, Rosenberg NA, Feldman MW, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Support from the relationship of genetic and geographic distance in human populations for a serial founder effect originating in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15942–15947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507611102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenow E. Über das Vorkommen der Malariaparasiten des Menschen bei den Afrikanischen Menschenaffen. Centralbl f Bakt I Abt Orig. 1920;85:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rich SM, Leendertz FH, Xu G, LeBreton M, Djoko CF, Aminake MN, Takang EE, Diffo JLD, Pike BL, Rosenthal BM, Formenty P, Boesch C, Ayala FJ, Wolfe FD. The origin of malignant malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14902–14907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907740106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich SM, Licht MC, Hudson RR, Ayala FJ. Malaria’s Eve: evidence of a recent population bottleneck throughout the world populations of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4425–4430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW. The Plasmodium gaboni genome illuminates allelic dimorphism of immunologically important surface antigens in P. falciparum. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Ferreira MU. A new model for the origins of allelic dimorphism in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Ferreira MU, Hartl DL. Evolution of allelic dimorphism in malarial surface antigens. Heredity (Edinb) 2008;100:103–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PM, Liu W, Learn GH, Rayner JC, Peeters M, Hahn BH. Source of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E744–745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112134108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter CP, Swellengrebel NH, Ihle JE. De dierlijke parasieten van den mensch en van onze huisdieren. 3. Scheltema and Holkema’s Boekhandel; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman SA, Liu W, Keele BF, Learn GH, Bittinger K, Mouacha F, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Manske M, Sherrill-Mix S, Li Y, Malenke JA, Delaporte E, Laurent C, Mpoudi Ngole E, Kwiatkowski DP, Shaw GM, Rayner JC, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Bushman FD, Hahn BH. Plasmodium falciparum-like parasites infecting wild apes in southern Cameroon do not represent a recurrent source of human malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7020–7025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman SA, Plenderleith LJ, Liu W, Loy DE, Learn GH, Li Y, Shaw KS, Ayouba A, Peeters M, Speede S, Shaw GM, Bushman FD, Brisson D, Rayner JC, Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Genomes of cryptic chimpanzee Plasmodium species reveal key evolutionary events leading to human malaria. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11078. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana S, Sullivan SA, Kawai S, Nakamura S, Kim HR, Goto N, Arisue N, Palacpac NM, Honma H, Yagi M, Tougan T, Katakai Y, Kaneko O, Mita T, Kita K, Yasutomi Y, Sutton PL, Shakhbatyan R, Horii T, Yasunaga T, Barnwell JW, Escalante AA, Carlton JM, Tanabe K. Plasmodium cynomolgi genome sequences provide insight into Plasmodium vivax and the monkey malaria clade. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1051–1055. doi: 10.1038/ng.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Mackay M, Goman M, Scaife JG. Allelic dimorphism in a surface antigen gene of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:273–287. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Mita T, Jombart T, Eriksson A, Horibe S, Palacpac N, Ranford-Cartwright L, Sawai H, Sakihama N, Ohmae H, Nakamura M, Ferreira MU, Escalante AA, Prugnolle F, Bjorkman A, Farnert A, Kaneko A, Horii T, Manica A, Kishino H, Balloux F. Plasmodium falciparum accompanied the human expansion out of Africa. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Parobek CM, Fairhurst RM. Haemoglobinopathies and the clinical epidemiology of malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:457–468. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh KK, Osier FH, Salanti A, Kamuyu G, Drought L, Failly M, Martin C, Marsh K, Conway DJ. Analysis of antibodies to newly described Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens supports MSPDBL2 as a predicted target of naturally acquired immunity. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3835–3842. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00301-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkiunas G, Ashford RW, Bensch S, Killick-Kendrick R, Perkins S. A cautionary note concerning Plasmodium in apes. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:231–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman SK, Sabeti PC, DeCaprio D, Neafsey DE, Schaffner SF, Milner DA, Jr, Daily JP, Sarr O, Ndiaye D, Ndir O, Mboup S, Duraisingh MT, Lukens A, Derr A, Stange-Thomann N, Waggoner S, Onofrio R, Ziaugra L, Mauceli E, Gnerre S, Jaffe DB, Zainoun J, Wiegand RC, Birren BW, Hartl DL, Galagan JE, Lander ES, Wirth DF. A genome-wide map of diversity in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet. 2007;39:113–119. doi: 10.1038/ng1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.