This is the first study to investigate the role of FOXO3a in cardiac stress, with focus on its role in modulating mitochondrial function and cardiac energetics and function. The gene delivery of dominant-negative FOXO3a in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction improved mitochondrial ultrastructure and function as well as myocardial and, particularly, diastolic function.

Keywords: heart failure, calcium regulation, apoptosis, FOXO3a, BNIP3

Abstract

The forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a) transcription factor has been shown to regulate glucose metabolism, muscle atrophy, and cell death in postmitotic cells. Its role in regulation of mitochondrial and myocardial function is not well studied. Based on previous work, we hypothesized that FOXO3a, through BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), modulates mitochondrial morphology and function in heart failure (HF). We modulated the FOXO3a-BNIP3 pathway in normal and phenylephrine (PE)-stressed adult cardiomyocytes (ACM) in vitro and developed a cardiotropic adeno-associated virus serotype 9 encoding dominant-negative FOXO3a (AAV9.dn-FX3a) for gene delivery in a rat model of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). We found that FOXO3a upregulates BNIP3 expression in normal and PE-stressed ACM, with subsequent increases in mitochondrial Ca2+, leading to decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial fragmentation, and apoptosis. Whereas dn-FX3a attenuated the increase in BNIP3 expression and its consequences in PE-stressed ACM, AAV9.dn-FX3a delivery in an experimental model of HFpEF decreased BNIP3 expression, reversed adverse left ventricular remodeling, and improved left ventricular systolic and, particularly, diastolic function, with improvements in mitochondrial structure and function. Moreover, AAV9.dn-FX3a restored phospholamban phosphorylation at S16 and enhanced dynamin-related protein 1 phosphorylation at S637. Furthermore, FOXO3a upregulates maladaptive genes involved in mitochondrial apoptosis, autophagy, and cardiac atrophy. We conclude that FOXO3a activation in cardiac stress is maladaptive, in that it modulates Ca2+ cycling, Ca2+ homeostasis, and mitochondrial dynamics and function. Our results suggest an important role of FOXO3a in HF, making it an attractive potential therapeutic target.

Listen to this article's corresponding podcast at http://ajpheart.podbean.com/e/role-of-foxo3a-in-heart-failure/.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This is the first study to investigate the role of FOXO3a in cardiac stress, with focus on its role in modulating mitochondrial function and cardiac energetics and function. The gene delivery of dominant-negative FOXO3a in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction improved mitochondrial ultrastructure and function as well as myocardial and, particularly, diastolic function.

the four mammalian forkhead transcription factors of the O class (FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4, and FOXO6) transcriptionally activate or inhibit a number of target genes and play an important role in proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, inflammation, differentiation, and stress resistance (41). FOXO activity is modulated by posttranslational modifications (31, 41), and regulation of gene expression varies among FOXO members and by cell type (14, 19, 29). Under growth-promoting stimuli, AKT phosphorylates and inhibits FOXO by relocalizing it to the cytoplasm. In the absence of growth factors, FOXO proteins translocate to the nucleus and regulate a series of target genes that promote cell cycle arrest, stress resistance, or apoptosis (17). However, other stress stimuli allow relocalization of FOXO factors to the nucleus, where they modulate expression of genes involved in stress responses (8, 16, 17, 33).

In skeletal muscle, FOXO3a induces the transcription of atrophy- and autophagy-related genes and, thus, controls two major systems of protein breakdown, the autophagic-lysosomal and ubiquitin-proteasomal pathways, independently (24). In the murine heart, FOXO3a overexpression induces cardiac atrophy (37). In rodent pressure overload (POL)-induced and human heart failure (HF), FOXO3a activation and expression of its downstream targets are increased and in proportion to HF severity (8, 15). Our previous studies in experimental POL and HF implicated JNK in activation of the FOXO3a-BCL/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) pathway in HF and established that, in POL-induced HF, the increase in BNIP3 expression induced mitochondrial Ca2+ overload via oligomerization of the voltage-dependent anion channels, mitochondrial fragmentation, and apoptosis, as well as left ventricular (LV) systolic and, particularly, LV diastolic dysfunction (7, 8). A role for BNIP3 in mediating mitochondrial and LV diastolic dysfunction is particularly noteworthy, as impaired energetic reserve, stress responses, and diastolic dysfunction are key features of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a common form of HF for which no effective therapy exists (5).

Although BNIP3 is one key downstream target of FOXO3a, FOXO3a regulates the expression of other genes in HF (15, 37), and other transcription factor(s) may regulate BNIP3 expression in HF (43). Accordingly, here in normal and stressed adult cardiomyocytes (ACM) and in experimental HFpEF, a model of cardiac oxidative stress, we use gene delivery strategies to specifically target FOXO3a and define its effects on BNIP3 expression, mitochondrial structure and function, cardiomyocyte Ca2+ cycling and homeostasis, and myocardial structure and function. We hypothesized that FOXO3a, through BNIP3, adversely affects mitochondrial morphology and function, as well as Ca2+ cycling and homeostasis, in cardiac oxidative stress and that opposing FOXO3a improves cardiac structure and function in experimental HFpEF. This hypothesis acknowledges proximity of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and neighboring intermyofibrillar mitochondria, both considered organelles of the high-Ca2+ microdomain (4, 18), which communicate via Ca2+ signaling (23, 39). Moreover, Ca2+ regulation and signaling within the ER-mitochondrial interphase regulate cell metabolism and, ultimately, promote survival or cell death (25, 28).

To test our hypotheses, we used adenoviruses encoding dominant-negative (Ad.dn-FX3a) and constitutively active (Ad.ca-FX3a) FOXO3a, as well as BNIP3 (Ad.BNIP3) and BNIP3 shRNA (Ad.Sh BNIP3), to modulate the FOXO3a-BNIP3 pathway in ACM in vitro. We then tested the effect of cardiac-targeted FOXO3a antagonism on HF progression in vivo via cardiotropic gene delivery of adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 encoding dn-FX3a (AAV9.dn-FX3a) in an established rat POL HFpEF model with prominent diastolic dysfunction and subtle, less obvious, systolic dysfunction. The dn-FX3a is mutated at the AKT phosphorylation sites and deleted at the DNA binding site (nucleotides 446–689), eliminating its ability to bind and regulate expression of its downstream effector genes. The gene delivery of dn-FX3a in cardiac stress acts as a competitive antagonist to endogenously activated native FOXO3a and provides a potential therapeutic strategy.

METHODS

Isolation and Culture of ACM and Design of In Vitro Experiments

The procedure for isolation of ACM was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health. In male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g body wt), anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of sodium heparin (100 U) and sodium pentobarbital (15 mg). Reagents used to prepare the Krebs-Henseleit isolation buffer were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All solutions were prepared with deionized water. The hearts were immediately removed and placed into an ice-cold isolation medium. The hearts were cannulated as quickly as possible and perfused using Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing (in mmol/l) 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4) for 4 min at 35°C. The buffer was pumped through the heart by means of a peristaltic pump at a rate of 10 ml/min. Then the heart was perfused for 15–20 min with collagenase (2 mg/ml)-containing low-Ca2+ (<0.25 mmol/l) Krebs-Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ). After 15 min, the heart was removed from the apparatus, and the ventricles were separated below the atrioventricular junction; then the heart was cut into 1- to 2-mm2 fragments and carefully resuspended for 1 min with a large automated pipette. The cells were filtered through a nylon mesh (100 μm-pore size) cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and allowed to settle by gravity for 5 min. The cell pellet was suspended in an incubation buffer [118 mmol/l NaCl, 25 mmol/l NaHCO3, 4.7 mmol/l KCl, 1.2 mmol/l KH2PO4, 1.2 mmol/l MgSO4, 10 mmol/l glucose, 30 mmol/l HEPES, 60 mmol/l taurine, 20 mmol/l creatine, 1% bovine serum albumin, vitamins, and amino acids (pH 7.4); Sigma] at 37°C. Ca2+ concentration was gradually (over 20 min) increased to 1.2 mmol/l. ACM were resuspended in M199 medium containing 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, 5% bovine serum albumin, and 100 nmol/l insulin (Sigma). Each heart yielded 6–7 × 106 rod-shaped ACM with >80% viability. ACM were placed on laminin-coated culture dishes in full nutrient M199 medium as mentioned above and allowed to attach for 1 h in humidified 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C and then washed once to remove unattached cells. All reagents, including phenylephrine (PE), were purchased from Sigma. The final PE dose was 10 μmol/l. After ACM isolation, the following experiments were performed.

Mitochondrial Ca2+.

ACM were loaded with the low-affinity Ca2+ dye rhodamine 2-AM (2 μmol/l; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 20 min. Images were acquired at ×40 magnification and analyzed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). At least nine fields were analyzed from each condition, and data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Mitochondrial membrane potential.

ACM were incubated in 50 nmol/l tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate for 30 min (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Images were acquired at ×40 magnification using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss). At least nine fields were analyzed from each condition, and data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence staining.

ACM were placed on laminin-precoated coverslips, washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Thereafter, ACM were exposed to blocking solution (10% goat serum in Dako blocking solution) for 1 h and incubated overnight with a rabbit monoclonal anti-FOXO3a primary antibody at 4°C (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; 1:200 dilution). ACM were then rinsed three times with PBS and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides, and images were acquired and analyzed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss). At least nine fields were analyzed, and data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Cell viability.

Cell viability was determined using the vital dyes calcein-AM (green fluorescence, 2 μmol/l) and ethidium homodimer-1 (red fluorescence, 4 μmol/l) to determine the number of live and dead cells, respectively (Molecular Probes). Images were obtained at ×10 magnification using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss). At least nine fields were analyzed from each condition, and data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Autophagosome formation.

For assessment of autophagosome formation, ACM were transfected with adenovirus containing enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP)-labeled microtubule-associated light chain 3 (eGFP-LC3), along with the adenovirus of interest to modulate the FOXO3a-BNIP3 pathway for 36 h. Images were acquired at ×40 magnification and analyzed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss). At least nine fields were analyzed from each condition, and data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with random oligo(dT) priming according to the manufacturer's protocols. PCR was performed using a sequence detection system (ABI PRISM 7500, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as the fluorescent marker and ROX (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) as a passive reference dye. PCR primers were as follows: BNIP3 [5′-AGCATGAATCTGGACGAAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AACATTTTCTGGCCGACTTG-3′ (reverse)], atrogin-1 [5′-gaagaccggctactgtggaa-3′ (forward) and 5′-atcaatcgcttgcggatct-3′ (reverse)], muscle RING-finger protein 1 [Murf1; 5′-aggactcctgccgagtgac-3′ (forward) and 5′-ttgtggctcagttcctcctt-3′ (reverse)], p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis [Puma; 5′-catgggactcctccccttac-3′ (forward) and 5′-cacctagttgggctccattt-3′ (reverse)], LC3-1 [5′-catgagcgagttggtcaaga-3′ (forward) and 5′-ccatgctgtgctggttca-3′ (reverse)], lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 [Lamp2; 5′-ctcctctctccggttacgg-3′ (forward) and 5′-catcggaccgaactgctc-3′ (reverse)], and superoxide dismutase 2 [SOD2; 5′-ctcctctctccggttacgg-3′ (forward) and 5′-catcggaccgaactgctc-3′ (reverse)]; 18S [5′-tgcggaaggatcattaacgga-3′ (forward) and 5′-agtaggagaggagcgagcgacc-3′ (reverse)] was used as an endogenous loading control.

Western Blotting

Protein was extracted by lysing cells and 20 mg of mechanically crushed tissue in a RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein extracts for Western blotting were obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and aspiration of the supernatant. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). For cytoplasmic/nuclear extraction, a cytoplasmic/nuclear extraction kit was used (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Twenty micrograms of proteins from each sample were loaded and electrophoresed using SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked for 1 h using blocking solution containing 0.15 mol/l NaCl, 3 mmol/l KCl, 25 mmol/l Tris base, 5% skim milk, and 0.05% Tween 20. Blots were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: GAPDH (Sigma; 1:10,000 dilution), BNIP3, FOXO3a, caspase-3/cleaved caspase-3, AKT, phosphorylated (S473) AKT, lamin B1, mitofusin 2, optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), and phosphorylated (S637) DRP1 (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000 dilution), Na+/Ca2+ exchanger 1 (NCX-1) and electron transport chain (ETC) complex cocktail (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:1,000 and 4:1,000 dilution, respectively), sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a), phospholamban (PLN), and phosphorylated (S16) PLN (Badrilla, Leeds, UK; 1:3,000 dilution). On the following day, after the blot was washed three times with TBS-0.05% Tween 20, it was incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Thermo Scientific, Barrington, IL; 1:10,000 dilution) for 45 min. Thereafter, the blot was washed three times with TBS-0.05% Tween 20, and a Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific, Barrington, IL) was used for the detection of protein bands using the film method. Band densities were quantified using Photoshop and normalized to GAPDH to correct for variations in protein loading. In Fig. 9B, mitofusin 2 and OPA1 share the same GAPDH.

Fig. 9.

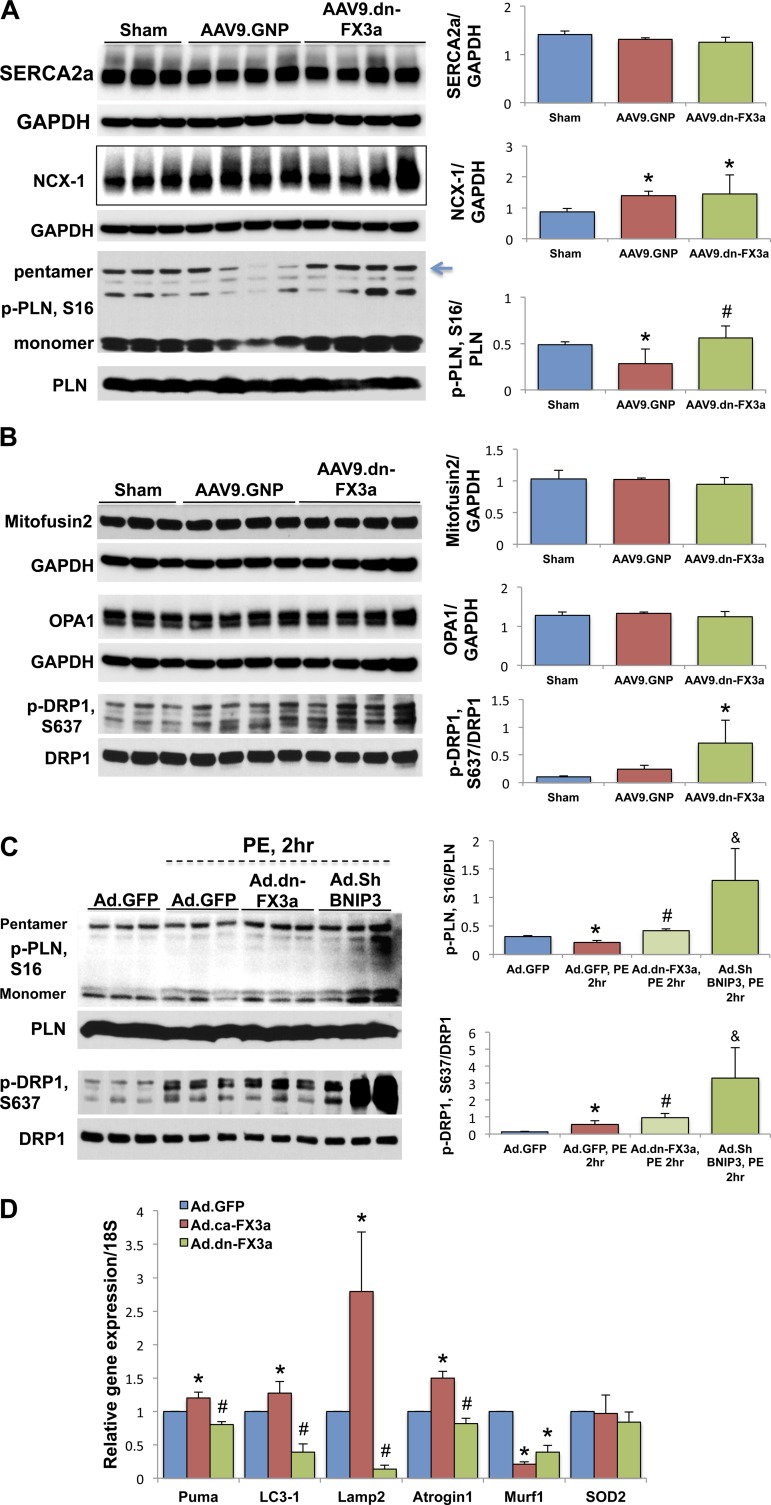

Gene delivery of AAV9.dn-FX3a restores S16 phosphorylation of PLN (p-PLN) and enhances S637 phosphorylation of DRP1 (p-DRP1) at the ER-mitochondrial interphase. A: immunoblot analysis of LV tissue lysates showing no significant change in sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) expression and increased Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX)-1 expression. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham and significant decrease in p-PLN, S16. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. Gene delivery of dn-FX3a restored PLN phosphorylation at S16. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. B: immunoblot analysis of LV tissue lysates shows no significant change in mitofusin 2 and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) expression between the 3 groups, whereas AAV9.dn-FX3a enhanced S637 phosphorylation of DRP1. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham and AAV9.GNP. C: expression of dn-FX3a prevented S16 and S637 dephosphorylation of PLN and DRP1, respectively, in PE-stressed ACM, whereas BNIP3 knockdown resulted in robust increases in PLN and DRP1 phosphorylation at these sites in PE-stressed ACM. &Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.dn-FX3a, PE,2hr. If the Ad.Sh BNIP3, PE,2hr group is eliminated, there is significant increase in p-PLN, S16 and p-DRP1, S637 in the Ad.dn-FX3a, PE,2hr group by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's correction. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP, PE,2hr. D: results from RT-PCR show significant increases in relative mRNA expression of the mitochondrial apoptosis marker p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (Puma), the autophagy-lysosomal markers microtubule-associated light chain 3 (LC3)-1 and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (Lamp2), and the atrophy marker atrogin-1 in the ca-FX3a-expressing ACM and significant decreases in dn-FX3a-expressing ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP and Ad.ca-FX3a. There were no significant differences in relative mRNA expression of muscle RING-finger protein 1 (Murf1) and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) between Ad.ca-FX3a and Ad.dn-FX3a groups. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cells and fractions (1 mm3) from fresh ventricles were prefixed in a solution of Trump's fixative overnight at 4°C, postfixed in 1% OsO4, dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohols, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were viewed with a transmission electron microscope (model 1400, JEOL, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), and images were obtained at ×5,000, ×12,000, ×20,000, and ×40,000 magnification.

Measurement of Citrate Synthase and Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit IV Activity

Citrate synthase activity was measured from LV tissue lysate according to Srere (2) by use of spectrophotometric analysis, absorbance at 412 nm, as previously described (32). Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV activity was measured using a Complex IV Rodent Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit (Abcam) by spectrophotometric analysis, absorbance at 550 nm. Kinetics of the enzyme activity were measured every minute at 30°C for 2 h. Protein concentrations in the LV tissue lysate were measured using a commercial kit (Detergent Compatible Protein Assay, Bio-Rad).

Picro Sirius Red Staining

LV cryosections (7 μm) were stained using the Picro Sirius red staining kit (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Briefly, slides were fixed in 100% ethanol for 2 min then in 50% ethanol for 2 min. After they were washed three times for 3 min in deionized water, the slides were stained with Picro Sirius red for 1 h and then washed twice in 0.5% acetic acid solution for 2 min. Slides were dehydrated in ethanol baths: 2 min in 95% ethanol and 2 min in 100% ethanol. After they were bathed twice in xylene, the slides were mounted with Cytoseal 60 (Thermo Scientific). Images were acquired at ×4 and ×10 magnification by light microscopy, and LV interstitial fibrosis was quantified from the ×10-magnified images using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). At least 10 fields per animal were quantified from ≥4 animals per group. Also, corresponding ×4-magnified images were obtained by polarized microscopy to assess collagen type: collagen I (yellow) and collagen III (green).

Image Analysis

Mitochondrial area and fluorescence intensity were analyzed using ImageJ, a public domain Java image-processing program inspired by the National Institutes of Health. Scale setting and calibration were done using the “Set Scale and Calibration Menu,” and measurement parameters were selected.

Measurements of Intracellular Ca2+ Kinetics and ER Ca2+ Content

ACM were placed on laminin-coated coverslips (Deckgläser) and loaded with fura 2-AM (Molecular Probes; 1 μmol/l) to detect intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). After cells were loaded for 10 min, they were washed twice with HEPES buffer containing 1 mmol/l Ca2+, and coverslips were placed into the bottom of a perfusion chamber connected with a cell stimulator (MyoPacer, IonOptix, Westwood, MA). The cells were perfused with HEPES buffer containing 0.6 mmol/l Ca2+ and paced at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. Fura 2 fluorescence was recorded with a dual-excitation fluorescence photomultiplier system (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) with an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope, a Fluor ×40 oil objective, and a CCD camera. ACM were exposed to light emitted by a 75-W lamp and passed through a 340- or 380-nm filter during stimulation to contract at 0.5 Hz. Changes in [Ca2+]i were monitored by fura 2 excitation at 340 and 380 nm and emission at 510 nm at baseline conditions and during rapid application of 10 mmol/l caffeine (Sigma). Data are expressed as the ratio of emission at 340 nm to emission at 380 nm following subtraction of background fluorescence. After a steady Ca2+ transient was obtained (after ∼2 min of pacing), cell pacing was stopped. After 30 s, caffeine (10 mmol/l) was added rapidly to the chamber for the release and assessment of ER Ca2+ content. At least eight cells were analyzed in each group, and data were obtained from three independent experiments.

Production of Recombinant Adenoviruses and AAV

Recombinant adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP) was prepared as previously described (21). Briefly, the AdEasy adenoviral vector system (Stratagene) was used to generate recombinant adenoviruses. Full-length eGFP gene was subcloned into the pShuttle vector (containing the cDNA for eGFP) under control of the CMV promoter. Viral titers were determined by the plaque assay, and the absence of replication-competent adenovirus was confirmed by PCR to assess for the wild-type (WT) E1 region. Ad.dn-FX3a and Ad.ca-FX3a were purchased from Vector BioLabs. Ad.eGFP-LC3, Ad.BNIP3, and Ad.Sh BNIP3 were produced at Vector BioLabs. A multiplicity of infection of 100 has been used in all infection experiments in vitro, and cardiomyocytes were transfected for 36 h to allow for adequate expression of the plasmid of interest before experiments shown in Figs. 1 and 3 were performed.

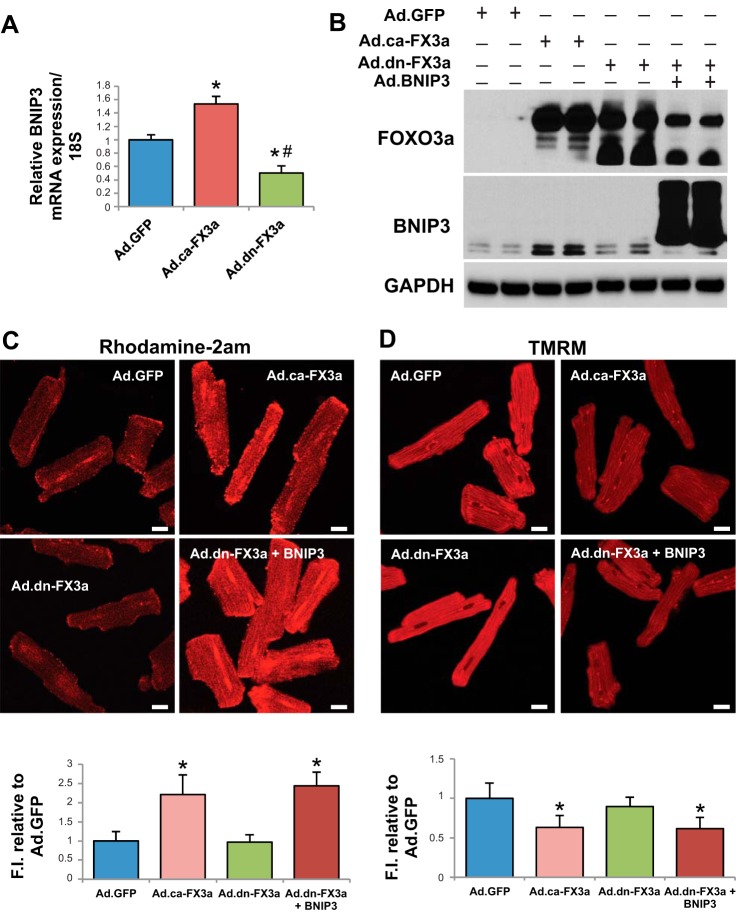

Fig. 1.

Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a) regulates BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) gene expression and, through BNIP3, induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondrial Ca2+ shift, mitochondrial autophagy, and apoptosis. A and B: constitutively active FOXO3a (ca-FX3a) induces BNIP3, mRNA and protein, gene expression in adult cardiomyocytes (ACM). *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP). #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. adenovirus encoding constitutively active FOXO3a (Ad.ca-FX3a). C and D: significant increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ and significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in ACM expressing ca-FX3a and dominant-negative FOXO3a (dn-FX3a) + BNIP3. FI, fluorescence intensity. TMRM, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP and Ad.dn-FX3a. Scale bars = 20 μm. E: significant decrease in ER Ca2+ content in ACM expressing ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3. F1/F0, fluorescence intensity relative to baseline. F–H: significant increases in cell death, cleaved caspase-3, and autophagosomes (green dots) in ca-FX3a- and dn-FX3a + BNIP3-expressing ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP and Ad.dn-FX3a. Scale bars = 100 μm (F) and 20 μm (G). Dividing lines in H show where the lane was rearranged in the initial captured image of the blot. Black contour shows that the 2 cleaved caspase-3 bands were cropped separately owing to the different exposure times needed to detect the lower cleaved caspase-3 band. Results are from ≥3 independent experiments.

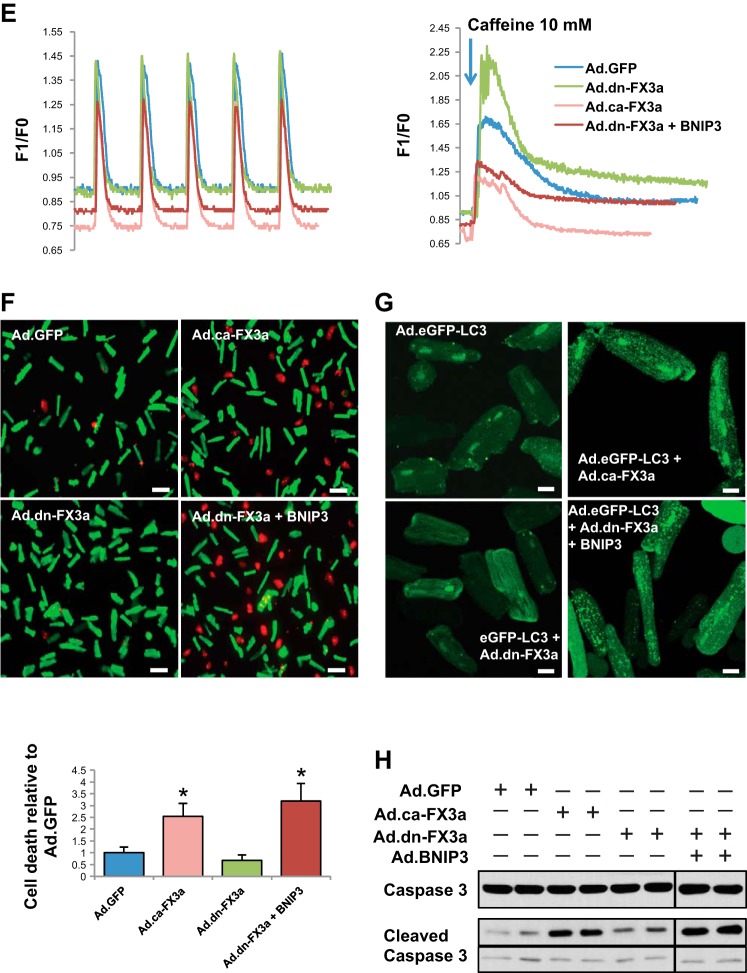

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of FOXO3a cellular compartmentalization, BNIP3 gene expression, and apoptosis in phenylephrine (PE)-stimulated ACM in vitro. A and B: significant FOXO3a nuclear compartmentalization in ACM 30 min after PE stimulation. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. CTL [control (unstimulated)]. Scale bars = 20 μm. FOXO3a cytoplasmic vs. nuclear expression result was obtained from the same blot, but different exposure time [30 vs. 60 min (PE,30′ and PE,60′)]. C: AKT activity significantly increased at 15 min (PE,15′) and significantly decreased 30 min after PE stimulation of ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. PE,0′. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. PE,0′ and PE,15′. D: peak in BNIP3 expression 2–4 h after PE stimulation of ACM and decline thereafter. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. CTL, PE,6hr, and PE,10hr. E: exponential increase in cell death of ACM 6 h after PE stimulation. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. CTL and PE,2hr. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. PE,6hr. Note significant difference between CTL and PE at 2 h by t-test; however, this significance is lost when 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons is used. Scale bars = 100 μm. F: exponential increase in cleaved caspase-3 (C3) in ACM 6 h after PE stimulation. *P < 0.05 vs. CTL, PE,2hr and PE,4hr. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. PE,6hr. Black contour highlighting shows that the 2 cleaved caspase-3 bands were cropped separately owing to the different exposure times needed to detect the lower cleaved caspase-3 band. PE final concentration is 10 μmol/l for all experiments. Results are from ≥3 independent experiments.

We generated a recombinant cardiotropic AAV9 allowing for cardiomyocyte-targeted expression of dn-FX3a (AAV9.dn-FX3a) under control of the CMV promoter. An AAV9-containing GFP plasmid with no promoter (AAV9.GNP) served as a negative control. HA-FOXO3a TM-ER-delta DB was a gift from Michael Greenberg (40) (plasmid 8354, Addgene, Cambridge, MA). The tamoxifen-inducible estrogen receptor (TM-ER) was removed from the original plasmid before it was cloned into the AAV backbone (PTR.dn-FX3a). AAV was produced by the method described by Rapti et al. (30), except the polyethylene glycol precipitation step was omitted. Also, after the first iodixanol gradient, modified second and third gradient steps were performed to concentrate the virus prior to dialysis. The modified gradient contained, from bottom to top, 4 ml of 60% iodixanol, 4 ml of 40% iodixanol, and 22 ml of AAV collected from the previous gradient diluted to 20% iodixanol content.

Experimental Model of Ascending Aortic Banding and Study Design

All procedures involving handling of the animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. The aortic banding model was used to generate a POL-induced hypertrophy model with LV remodeling but relatively preserved ejection fraction (EF). Sprague-Dawley rats (180–200 g body wt) underwent ascending aortic banding (AAB), as previously described in detail (12). Briefly, animals were sedated by intraperitoneal administration of ketamine (65 mg/kg) plus xylazine (5 mg/kg) and intubated using a 16-gauge catheter and mechanically ventilated with tidal volume of 2 ml at 50 cycles/min and fraction of inspired O2 of 21%. A 1-cm incision was made in the right axilla, and the thoracic cage was approached at the level of the second intercostal space. The thymus gland was dissected, the underlying ascending aorta was separated from the superior vena cava, and a 1-mm (2-mm2 area) vascular clip was placed around the ascending aorta, just before the right brachiocephalic artery. Buprenorphine SR (0.6 mg/kg) was administered as a single dose subcutaneously for analgesia after the surgery. POL developed upon placement of the vascular clip. The size of the vascular clip allowed for generation of a compensated POL model with preserved EF. At 8 wk after AAB, animals were included if there was evidence of increased LV volumes [LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) ≥600 μl, LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) ≥120 μl, and LVEF ∼80%] compared with 3 wk after AAB and were randomized to receive AAV9.dn-FX3a (n = 8) vs. AAV9.GNP (n = 8) for 6 wk. Age-matched sham-operated (sham) animals were used as control (n = 5). Echocardiography parameters at 3 and 8 wk after AAB (time of AAV9 injection) for the AAV9.GNP-injected rats are presented in Table 2. Note significant increases in LVEDV and LVESV at 8 wk vs. 3 wk post-AAB with a ∼10% decrease in LVEF.

Table 2.

Echocardiography parameters of AAV9.GNP-injected animals at 3 and 8 wk after AAB

| AAB |

||

|---|---|---|

| Group | 3 wk | 8 wk |

| BW, g | 314 ± 25.09 | 475.86 ± 55.30* |

| IVSd, mm | 2.78 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| LVPWd, mm | 2.77 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| LVIDd, mm | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 0.25* |

| LVIDs, mm | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3* |

| LVFS, % | 77.88 ± 4.29 | 66.25 ± 4.33* |

| LVEDV, μl | 334.36 ± 28.4 | 638.02 ± 25.90* |

| LVESV, μl | 28.64 ± 8.4 | 131.36 ± 14.17* |

| LVEF, % | 91.38 ± 2.68 | 79.43 ± 1.75* |

Values are means ± SD of 8 rats in the AAV9.GNP group. AAV9.GNP, adeno-associated virus serotype 9 containing GFP plasmid with no promoter; AAB, ascending aortic banding; BW, body weight; IVSd, interventricular septal thickness at diastole; LVPWd, left ventricular (LV) posterior wall diameter; LVIDd and LVIDs, LV internal diameter at end diastole and end systole; LVFS, LV fractional shortening; LVEDV and LVESV, LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume; LVEF, LV ejection fraction.

P < 0.05 vs. 3 wk.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using an echocardiography apparatus (Vivid 7) with a 14-MHz probe (model i13L, General Electric, New York, NY). Animals were sedated with ketamine (80–100 mg/kg ip). Long-axis parasternal views and short-axis parasternal two-dimensional views, at the mid-papillary level, of the LV were obtained to calculate LVEDV and LVESV, as well as LVEF. Volumes were calculated using the formula of the area-length method: V = 5/6 × A × L, where V is volume (in ml), A is cross-sectional area of the LV cavity (in cm2) obtained from the midpapillary parasternal short-axis image in diastole and systole, and L is length of the LV cavity (in cm) measured from the parasternal long-axis image as the distance from the endocardial LV apex to the mitral-aortic junction in diastole and systole. M-mode images were obtained by two-dimensional guidance from the parasternal short-axis view, at the level of the midpapillary muscle, to measure LV wall thickness of the septum and posterior wall (mm) and LV end-diastolic and LV end-systolic diameters (mm) and to calculate LV fractional shortening (%).

Invasive Pressure-Volume Loop Measurements of the LV

At 6 wk after AAV9 injection, LV pressure-volume (P-V) loop measurements were obtained as previously described (27). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with inhaled 5% (vol/vol) isoflurane for induction, intubated, and mechanically ventilated (see Experimental Model of Ascending Aortic Banding and Study Design). Isoflurane was lowered to 2–3% (vol/vol) for surgical incision. The chest was opened through a median sternotomy. A 1.9F rat P-V catheter (Scisense, London, ON, Canada) was inserted into the LV apex through an apical stab with a 25-gauge needle. Anesthesia was then decreased to 0.5% isoflurane to maintain sedation and a stable heart rate at ∼350 beats/min. Hemodynamic recordings were performed 5 min after stable heart rate using a P-V control unit (model FY097B, Scisense). The intrathoracic inferior vena cava was transiently occluded to decrease venous return during the recording to obtain load-independent P-V relationships. Linear fits were obtained for end-systolic P-V relationships and exponential fits for end-diastolic P-V relationships to derive the LV stiffness constant (β). To adjust for the degree of LV hypertrophy, we calculated the dimensionless chamber stiffness index by multiplying the end-diastolic P-V relationship by the LV mass. Blood resistivity was measured using a special probe (Scisense). Volume measurements were calculated using Wei's method from the admittance-acquired data, and pressure sensors were calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Values are means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni's correction. P < 0.05 was considered significant. For the pre-AAV9 injection and 6 wk postinjection echocardiography data, two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni's correction was used. Correlation analysis was done using Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients (r) to assess for linear and nonlinear correlation between two variables, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prism software was used to perform the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

FOXO3a-BNIP3 Pathway Modulation in ACM

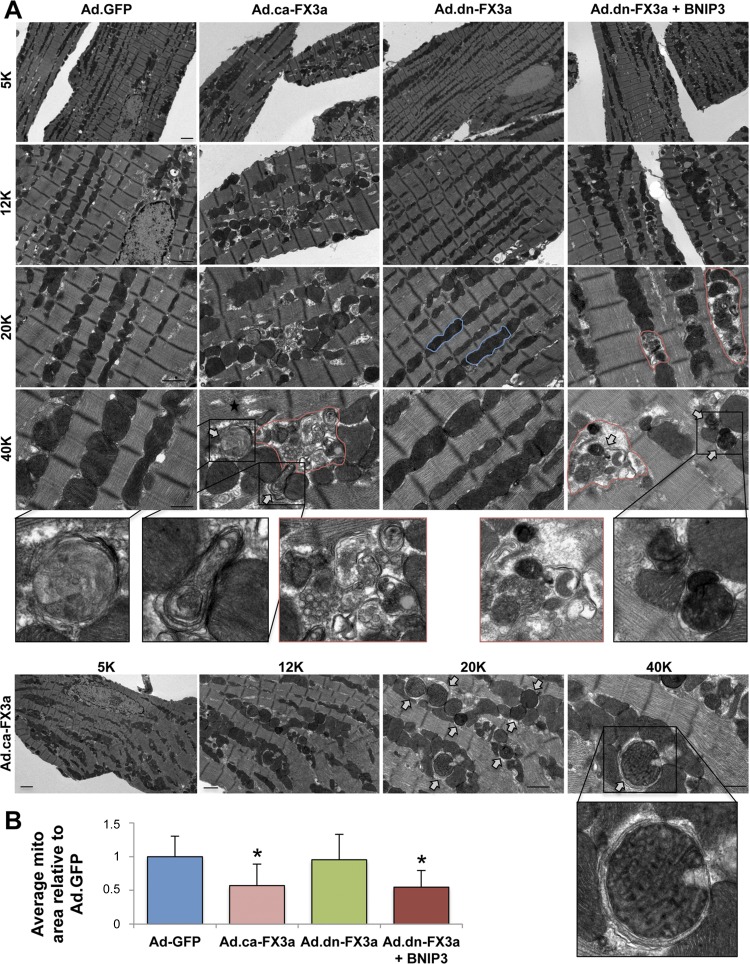

To assess whether FOXO3a modulates BNIP3 gene expression, we used adenoviruses encoding ca-FX3a (positive control) and dn-FX3a (negative control) in ACM in vitro. Ad.GFP was used as a control adenovirus. To further understand whether the downstream effect of FOXO3a on the mitochondria is through BNIP3, we simultaneously expressed dn-FX3a to silence FOXO3a activity and overexpressed BNIP3 (BNIP3 OE). Expression of ca-FX3a significantly increased BNIP3 mRNA and protein expression in ACM (Fig. 1, A and B). Rhodamine 2-AM staining showed a significant increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ in the ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3 OE ACM (Fig. 1C). This increase in BNIP3 expression and mitochondrial Ca2+ is associated with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (20, 22, 34) and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm; Fig. 1D). We then assessed if these changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ are associated with changes in Ca2+ cycling during the contraction-and-relaxation phase and changes in ER Ca2+ content. Ca2+ transients in single cardiomyocytes showed no significant changes on a beat-to-beat basis in the different groups (Fig. 1E, Table 1); however, when caffeine was administered to open the ryanodine receptors and release ER Ca2+, there was a significant decrease in ER Ca2+ content, as measured by the area under the curve, in the ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3 OE ACM, suggesting a shift in Ca2+ from the ER into the mitochondria (Fig. 1E, Table 1). Moreover, the caffeine-induced increase in ER Ca2+ release unraveled abnormalities in ER Ca2+ reuptake. There was a trend toward prolonged Ca2+ reuptake time (τ), and, when adjusted to the ER Ca2+ content of the Ad.GFP, a significant increase in this parameter in the ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3 OE ACM (Table 1). Subsequently, after this ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ shift and loss of Δψm, BNIP3 induces mitochondrial apoptosis, as evidenced by increased cell death and cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 1, F and H), as well as mitophagy with increased autophagosomes (Fig. 1G), in the ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3 OE ACM. Transmission electron microscopy showed areas with significant mitochondrial fragmentation and altered alignment of the intermyofibrillar mitochondria with the adjacent sarcomeres, as well as mitochondrial autophagolysis with loss of mitochondrial mass in the ca-FX3a and dn-FX3a + BNIP3 OE ACM. In contrast, there were areas of mitochondrial fusion in the dn-FX3a group (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Ca2+ transient parameters at baseline and at caffeine administration

| Baseline Parameters |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Baseline | Peak | Time to peak 90% | Time to baseline 90% | τ | Beat-to-beat Ca2+ release, AUC |

| Ad.GFP | 0.844 ± 0.073 | 1.19 ± 0.171 | 0.069 ± 0.011 | 0.49 ± 0.043 | 0.21 ± 0.023 | 0.098 ± 0.013 |

| Ad.ca-FX3a | 0.82 ± 0.026 | 1.25 ± 0.08 | 0.072 ± 0.005 | 0.5 ± 0.092 | 0.21 ± 0.037 | 0.107 ± 0.012 |

| Ad.dn-FX3a | 0.89 ± 0.022 | 1.17 ± 0.11 | 0.065 ± 0.005 | 0.48 ± 0.075 | 0.19 ± 0.032 | 0.101 ± 0.006 |

| Ad.dn-FX3a + BNIP3 | 0.83 ± 0.066 | 1.31 ± 0.19 | 0.065 ± 0.005 | 0.45 ± 0.066 | 0.19 ± 0.022 | 0.1 ± 0.013 |

| Caffeine Parameters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| ER Ca2+ content, AUC | τ | τ relative to and adjusted to Ad.GFP ER Ca2+ content | |

| Ad.GFP | 1.09 ± 0.35 | 2.05 ± 0.81 | 1 ± 0.39 |

| Ad.ca-FX3a | 0.58 ± 0.36* | 2.77 ± 1.42 | 3.39 ± 1.60* |

| Ad.dn-FX3a | 1.52 ± 0.48 | 1.59 ± 0.65 | 0.59 ± 0.30 |

| Ad.dn-FX3a + BNIP3 | 0.27 ± 0.1* | 2.25 ± 0.87 | 4.06 ± 2.06* |

Values are means ± SD. AUC, area under the curve; τ, Ca2+ reuptake time; Ad.GFP, adenovirus encoding GFP; Ad.ca-FX3a, adenovirus encoding constitutively active FOXO3a; Ad.dn-FX3a, adenovirus encoding dominant-negative FOXO3a; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP and Ad.dn-FX3a.

Fig. 2.

Expression of ca-FX3a in ACM in vitro induces mitochondrial fragmentation and autophagolysis. A: representative transmission electron microscopy images showing significant mitochondrial fragmentation and areas with significant autophagolysis of mitochondria (red lines) and an abundance of autophagolysosomes (white arrows) in ca-FX3a- and dn-FX3a + BNIP3-expressing ACM but a tendency toward mitochondrial fusion in dn-FX3a-expressing ACM (blue lines). B: decrease in average mitochondrial area in Ad.ca-FX3a and Ad.dn-FX3a + BNIP3 ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP and Ad.dn-FX3a. 5K, 12K, 20K, and 40K magnification represent scale bars = 2, 1, 1, and 0.5 μm, respectively.

Kinetics and Functional Assessment of the FOXO3a-BNIP3 Pathway in ACM

To assess the kinetics of the FOXO3a-BNIP3 pathway in ACM in vitro, we used PE (10 μmol/l) as a stressor and identified the time course of FOXO3a nuclear translocation, increases in BNIP3 expression, and apoptosis. Immunofluorescence staining, as well as immunoblotting, of cellular cytoplasmic/nuclear fractions showed significant FOXO3a nuclear compartmentalization 30 min after PE stimulation (Fig. 3, A and B). These changes in FOXO3a cellular compartmentalization coincided with a significant decrease in AKT activity. While in the first 15 min after PE exposure, there was a slight, but significant, increase in AKT activity, it declined thereafter (Fig. 3C). After FOXO3a nuclear translocation, BNIP3 expression increased at 1 h (data not shown), peaked 2–4 h after PE stimulation, and then declined (Fig. 3D). After the increase in BNIP3 expression, there was an exponential increase in apoptosis at 6 and 10 h, respectively (Fig. 3, E and F).

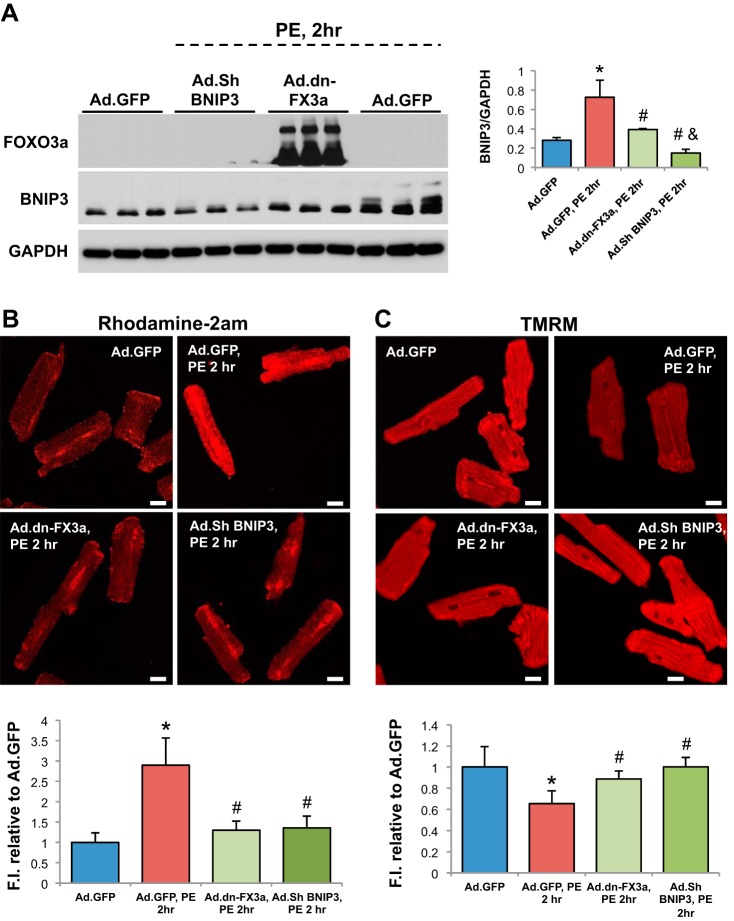

After determining the kinetics of the FOXO3a-BNIP3 pathway in PE-stressed ACM in vitro, we examined whether gene delivery of dn-FX3a can prevent the increase in BNIP3 expression and its consequences in PE-stressed ACM. Expression of dn-FX3a prevented the increase in BNIP3 expression and abrogated the subsequent increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ and loss of Δψm in PE-stressed ACM at 2 h. Similar results were seen with BNIP3 knockdown using BNIP3 shRNA (Fig. 4, A–C). Ultrastructurally, gene delivery of dn-FX3a, as well as BNIP3 knockdown, prevented mitochondrial fragmentation and loss of mitochondrial mass and preserved the normal alignment of the intermyofibrillar mitochondria with the adjacent sarcomeres in PE-stressed ACM (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Gene delivery of dn-FX3a prevents increase in BNIP3 expression and its consequences in PE-stimulated ACM. A: dn-FX3a prevented the increase in BNIP3 expression in PE-stressed ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP, PE,2hr. &Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.dn-FX3a, PE,2hr. B: dn-FX3a prevented the increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ in PE-stressed ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP, PE,2hr. C: dn-FX3a attenuated the loss of Δψm in PE-stressed ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP, PE,2hr. Scale bars = 20 μm. Results are from ≥3 independent experiments. D: representative transmission electron microscopy images showing areas with significant mitochondrial fragmentation and loss of mitochondrial mass (red lines), as well as abundance of autophagosomes (arrows), in Ad.GFP, PE,2hr group. E: expression of dn-FX3a, as well as BNIP3 shRNA, significantly attenuated mitochondrial fragmentation in PE-stressed ACM. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Ad.GFP, PE,2hr. 5K, 12K, 20K, and 40K magnification represent scale bars = 2, 1, 1, and 0.5 μm, respectively.

Gene Delivery of AAV9.dn-FX3a Improves Mitochondrial Structure and Function and Myocardial Diastolic and Systolic Function in Experimental HFpEF

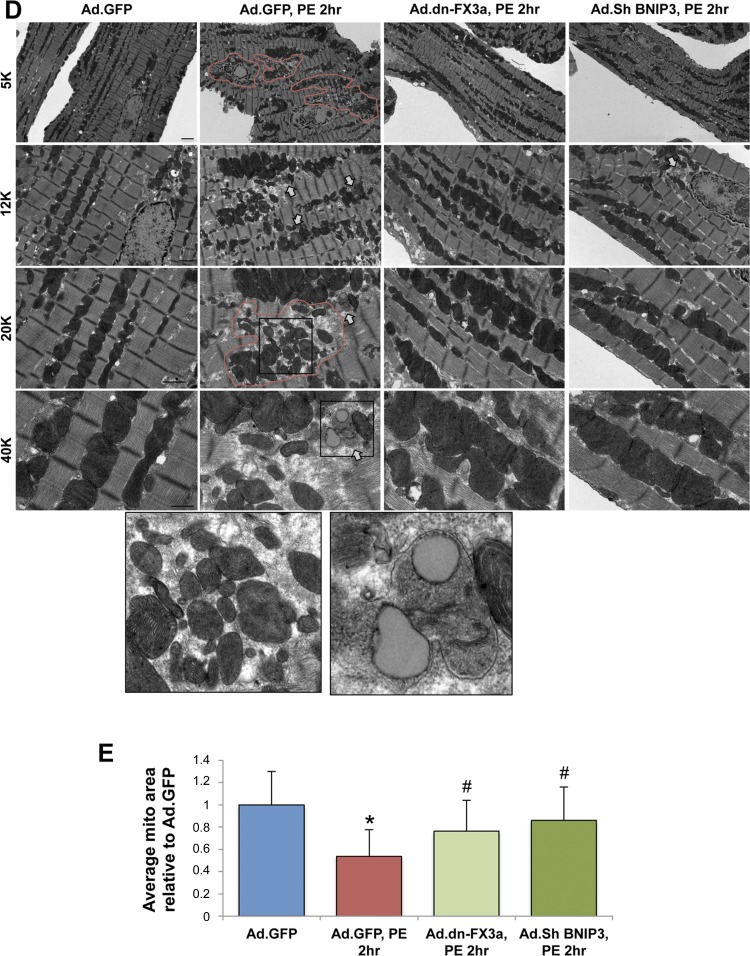

We used a rat POL model of HFpEF, with prominent diastolic dysfunction and subtle systolic dysfunction, to test the effect of AAV9.dn-FX3a on HF progression. AAB or the sham procedure was performed, and serial (3- and 8-wk post-AAB/sham) echocardiography was utilized to identify rats with POL hypertrophy and increased LV and left atrial volumes but preserved LVEF at 8 wk post-AAB (Tables 2 and 3). At 8 wk post-AAB, 5 × 1011 DNase-resistant particles of AAV9.dn-FX3a or control virus (AAV9.GNP) were administered to HFpEF rats by tail vein injection. Representative M-mode images of age-matched sham or AAV9.GNP- or AAV9.dn-FX3a-injected AAB rats at AAV9 injection (8 wk post-AAB) and 6 wk after injection (14 wk post-AAB) are shown in Fig. 5A. Complete echocardiographic parameters of the animals are shown in Table 3. At AAV9 injection (8 wk post-AAB), there was a trend toward higher LVEDV in the AAV9.GNP than sham animals (Fig. 5B). However, LVEDV was significantly higher in the AAV9.dn-FX3a than sham animals: three of the eight AAV9.dn-FX3a-treated animals were more remodeled and had significantly higher LVEDV than sham and AAV9.GNP animals at AAV9 injection (Fig. 5, B and F). At injection, LVESV was higher in AAV9.dn-FX3a and AAV9.GNP AAB than sham animals but LVEF was similar in all groups (Fig. 5, C and D).

Table 3.

Echocardiography parameters of sham, AAV9.GNP, and AVV9.dn-FX3a groups at AAV injection and 6 wk postinjection

| AAV Injection (8 wk post-AAB) |

6 wk Postinjection (14 wk Post-AAB) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 5) | AAV9.GNP (n = 8) | AAV9.dn-FX3a (n = 8) | Sham (n = 5) | AAV9.GNP (n = 8) | AAV9.dn-FX3a (n = 8) | |

| HW/BW, mg/g | 2.35 ± 0.13a | 3.86 ± 0.61 | 3.90 ± 0.61 | |||

| LVW/BW, mg/g | 1.66 ± 0.11a | 2.88 ± 0.37 | 2.89 ± 0.37 | |||

| BW, g | 472.8 ± 33.75 | 475.86 ± 55.30 | 464.16 ± 39.55 | 539.8 ± 36.94 | 560.38 ± 75.7 | 545.25 ± 61.26 |

| IVSd, mm | 1.8 ± 0.2a | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| LVPWd, mm | 2.0 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.16 | 2.0 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| LVIDd, mm | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 7.0 ± 0.25 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 7.1 ± 0.15 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.9 |

| LVIDs, mm | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5d |

| LVFS, % | 60.6 ± 1.52 | 66.25 ± 4.33 | 63.78 ± 3.49 | 61.8 ± 1.79 | 64.13 ± 5.69 | 73 ± 4.4d |

| LVEDV, μl | 546.19 ± 61.86 | 638.02 ± 25.90 | 730.64 ± 152.18b | 560.52 ± 25.84 | 700.34 ± 55.45 | 569.70 ± 145.60c |

| LVESV, μl | 96.88 ± 18.57 | 131.36 ± 14.17b | 144.07 ± 24.98b | 105.86 ± 8.89 | 150.33 ± 14.53b | 75.80 ± 33.17c,e |

| LVEF, % | 82.36 ± 1.52 | 79.43 ± 1.75 | 80.42 ± 1.32 | 81.12 ± 1.24 | 78.46 ± 2.26 | 87.05 ± 2.27d |

Values are means ± SD. HW, heart weight; LVW, LV weight.

P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP and AAV9.dn-FX3a. bP < 0.05 vs. sham. cP < 0.05 vs. AAV9.dn-FX3a at AAV injection. dP < 0.05 vs. all other groups at AAV injection and 6 wk postinjection. eP < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP at AAV injection and 6 wk postinjection.

Fig. 5.

Gene delivery of adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9).dn-FX3a significantly attenuated left ventricular (LV) end-systolic volume (LVESV) and improved LV ejection fraction (LVEF) in a rat model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). A: representative M-mode images at the papillary muscle level at AAV injection and at 6 wk (W6) postinjection. B: trend toward increased LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) in the AAV9.GNP vs. sham group at AAV injection. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. C: significant increase in LVESV in AAV-injected rats vs. sham at AAV injection. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. D: no significant difference in LVEF between groups. E: no significant difference in heart weight-to-body weight (HW/BW) and LV weght-to-body weight (LVW/BW) ratios between AAV9.GNP and AAV9.dn-FX3a groups. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. F–H: trend toward decreased LVEDV in AAV9.dn-FX3a vs. AAV9.GNP group at 6 wk postinjection. LVESV was significantly decreased and LVEF was significantly increased in AAV9.dn-FX3a group at 6 wk postinjection. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.dn-FX3a at AAV injection. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP at AAV injection and 6 wk postinjection.

At 6 wk after AAV9.GNP or AAV9.dn-FX3a injection, at euthanization, heart weight-to-body weight and LV weight-to-body weight ratios were significantly increased in both AAB groups compared with sham animals but were not different between AAB animals treated with AAV9.GNP and AAV9.dn-FX3a (Fig. 5E). At 6 wk after AAV9.dn-FX3a injection, LVEDV and LVESV were lower and LVEF was higher than at AAV9.dn-FX3a injection, and LVESV was lower and LVEF was higher than in AAV9.GNP-treated AAB animals at 6 wk postinjection (Fig. 5, F–H, Table 3). In AAV9.GNP-treated AAB animals, LVEDV, LVESV, and LVEF at 6 wk after injection were similar to values at AAV9.GNP injection.

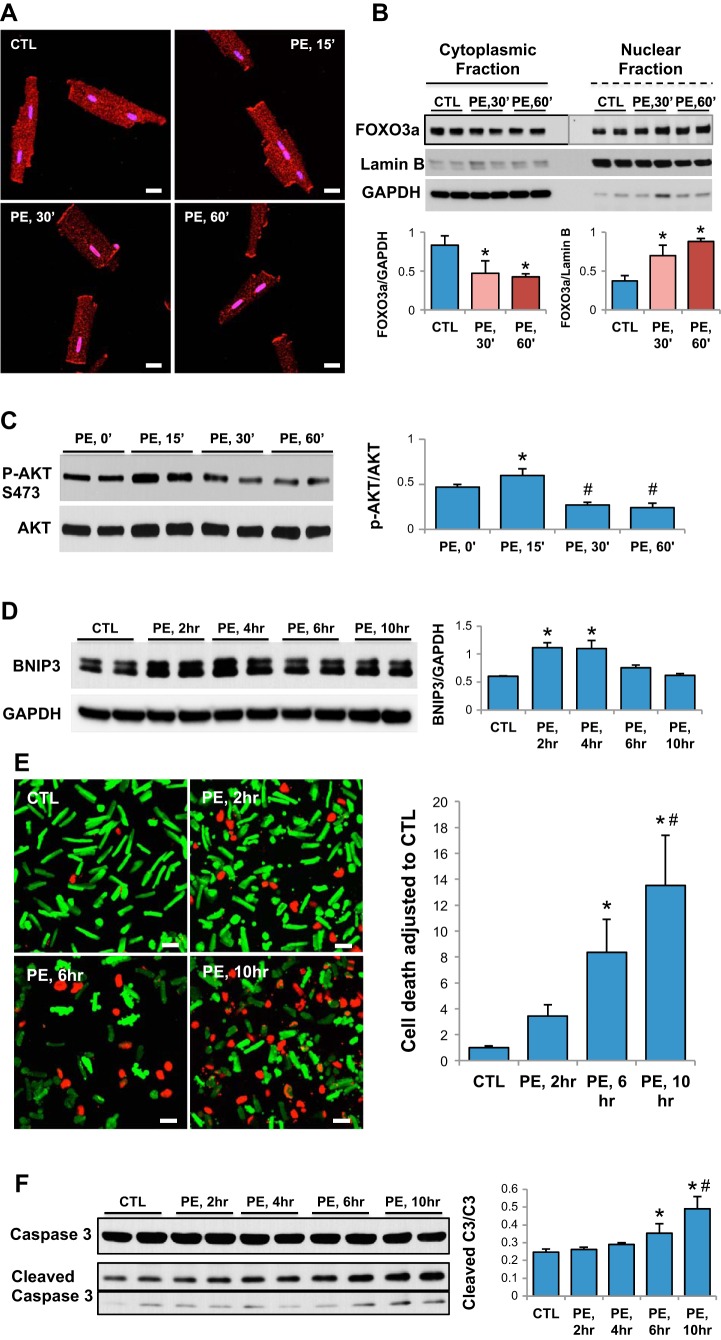

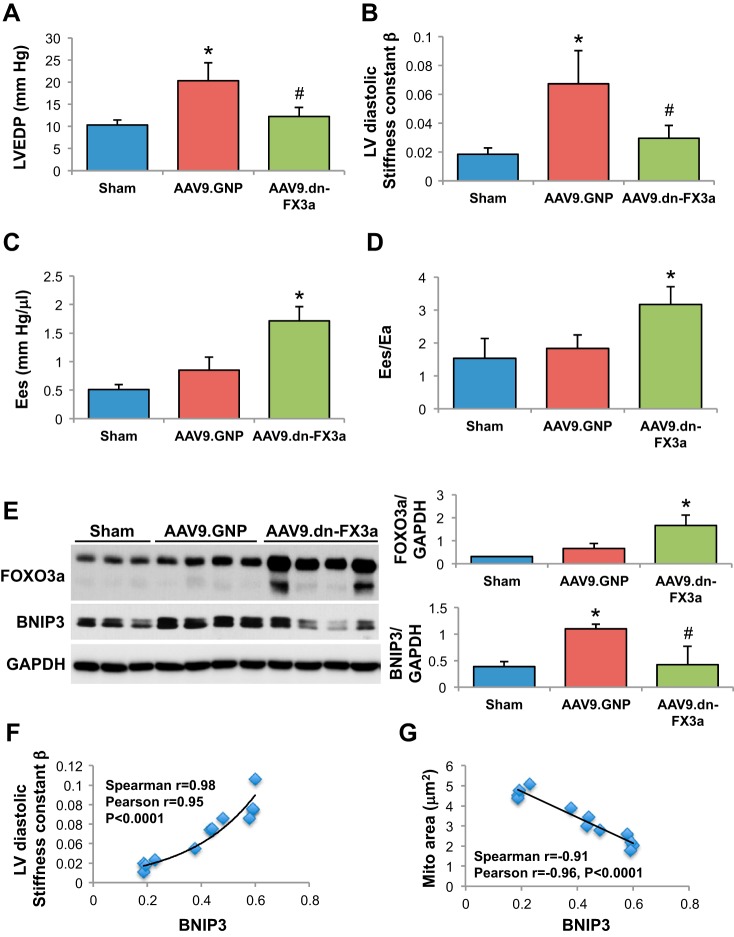

At preeuthanization catheterization, heart rate was similar between groups but LV maximal pressure was markedly elevated in both AAB groups compared with sham animals (Table 4). Hemodynamic parameters in the sham, AAV9.GNP, and AAV9.dn-FX3a groups are presented in Table 4. LV end-diastolic pressure (Fig. 6A) and LV diastolic stiffness [diastolic stiffness constant (β); Fig. 6B] were lower in AAV9.dn-FX3a- than AAV9.GNP-treated rats, myocardial contractility and efficiency were improved in AAV9.dn-FX3a- compared with AAV9.GNP-treated rats. End-systolic e lastance (Ees) was higher (Fig. 6C) and the ratio of Ees to arterial elastance (Ees/Ea) was higher in AAV9.dn-FX3a- than AAV9.GNP-treated rats (Fig. 6D). Myocardial contractility and efficiency were impaired in AAV9.GNP-treated animals, although their Ees and Ees/Ea values are similar to sham animals (pseudo-normal). This is because end-systolic pressure and, therefore, Ees slope, are significantly higher in AAV9.GNP-treated than sham animals at any given volume. This gives a false impression that these animals have normal myocardial contractility, when, in reality, it is impaired and has decreased from the level of what it was at 3 wk after AAB. Immunoblotting of LV tissue lysates confirmed a robust increase in FOXO3a expression (WT + dn-FX3a) compared with sham and AAV9.GNP groups (Fig. 6E). BNIP3 expression was lower in AAV9.dn-FX3a than AAV9.GNP rats, whereas BNIP3 expression was increased in AAV9.GNP compared with sham rats (Fig. 6E). LV diastolic stiffness (β) increased exponentially (Fig. 6F), while mitochondrial area decreased linearly with the intensity of BNIP3 expression in LV myocardium (Fig. 6G). There was no statistically significant correlation between the intensity of BNIP3 expression and LVEF (data not shown).

Table 4.

Hemodynamic parameters of sham, AAV9.GNP, and AAV9.dn-FX3a groups

| n | HR, beats/min | LV Pmax, mmHg | LVEDP, mmHg | LVEDV, μl | LVESV, μl | LVEF, % | Ees, mmHg/μl | EDPVR, mmHg/μl | Ees/Ea | DCSI Adjusted to Sham | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 5 | 352.45 ± 43.31 | 125.46 ± 20.18* | 10.35 ± 1.06 | 583.92 ± 23.17 | 220.92 ± 35.55 | 62.06 ± 6.13 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 1.54 ± 0.60 | 0.99 ± 0.23 |

| AAV9.GNP | 7 | 336.47 ± 47.56 | 233.32 ± 23.30 | 20.32 ± 4.056† | 591.80 ± 42.91 | 194.27 ± 23.05 | 67.13 ± 3.38 | 0.85 ± 0.23 | 0.067 ± 0.022† | 1.83 ± 0.41 | 6.49 ± 2.69† |

| AAV9.dn-FX3a | 7 | 377.26 ± 37.80 | 223.65 ± 18.31 | 12.24 ± 2.01‡ | 427.8 ± 93.76§ | 86.22 ± 36.94§ | 80.44 ± 4.60§ | 1.71 ± 0.25§ | 0.029 ± 0.009‡ | 3.17 ± 0.54§ | 2.75 ± 0.77‡ |

Values are means ± SD. HR, heart rate; Pmax, maximal pressure; Ees, end-systolic elastance; EDPVR, end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship; Ea, arterial elastance; DCSI, dimensionless chamber stiffness index.

P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP and AAV9.dn-FX3a. †P < 0.05 vs. sham. ‡P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. §P < 0.05 vs. sham and AAV9.GNP.

Fig. 6.

Gene delivery of AAV9.dn-FX3a significantly attenuated BNIP3 expression and improved myocardial relaxation and contraction in a rat model of HFpEF. A and B: AAV9.dn-FX3a significantly attenuated LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and myocardial stiffness. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. C and D: AAV9.dn-FX3a significantly enhanced myocardial contractility [end-systolic elastance (Ees)] and myocardial efficiency [ratio of Ees to arterial elastance (Ees/Ea)]. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. E: immunoblot of LV tissue lysate shows significant increase in FOXO3a expression in the AAV9.dn-FX3a group. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham and AAV9.GNP and significant decrease in BNIP3 expression. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. F and G: myocardial stiffness increased exponentially while mitochondrial area decreased linearly with intensity of BNIP3 expression in LV myocardium.

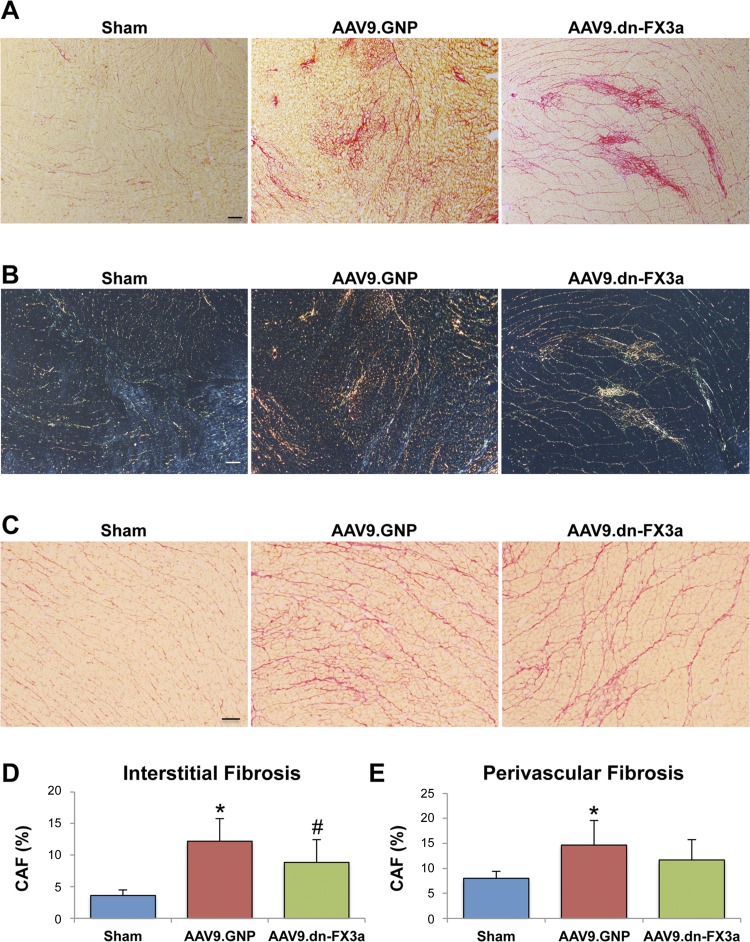

Histological analysis with Picro Sirius red staining showed increased LV interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in both AAB groups compared with sham animals, but interstitial fibrosis and perivascular fibrosis tended to be less severe in AAV9.dn-FX3a- than AAV9.GNP-treated rats (Fig. 7, A–E). Polarized microscopy images show higher collagen type I in AAV9.GNP than AAV9.dn-FX3a rats (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Gene delivery of AAV9.dn-FX3a attenuated LV interstitial fibrosis in experimental HFpEF. A, C, D and E: representative photomicrographs taken by light microscopy from the Picro Sirius red-stained slides (A and C) showing significant decrease in LV interstitial fibrosis and trend toward decreased perivascular fibrosis in the AAV9.dn-FX3a group (D and E). *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. Magnification ×4 (A) and ×10 (C). Scale bars = 200 and 100 μm, respectively. B: polarized light microscopy images corresponding to light microscopy images in A exhibit characteristic birefringence of Picro Sirius red-stained areas. Magnification ×4. Scale bar = 200 μm.

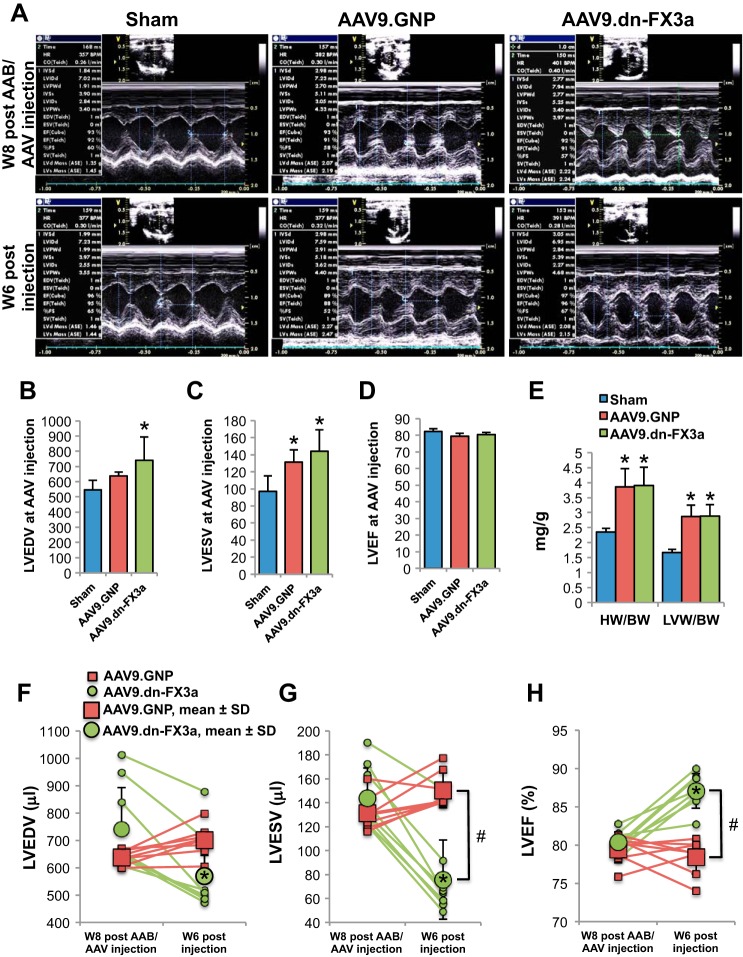

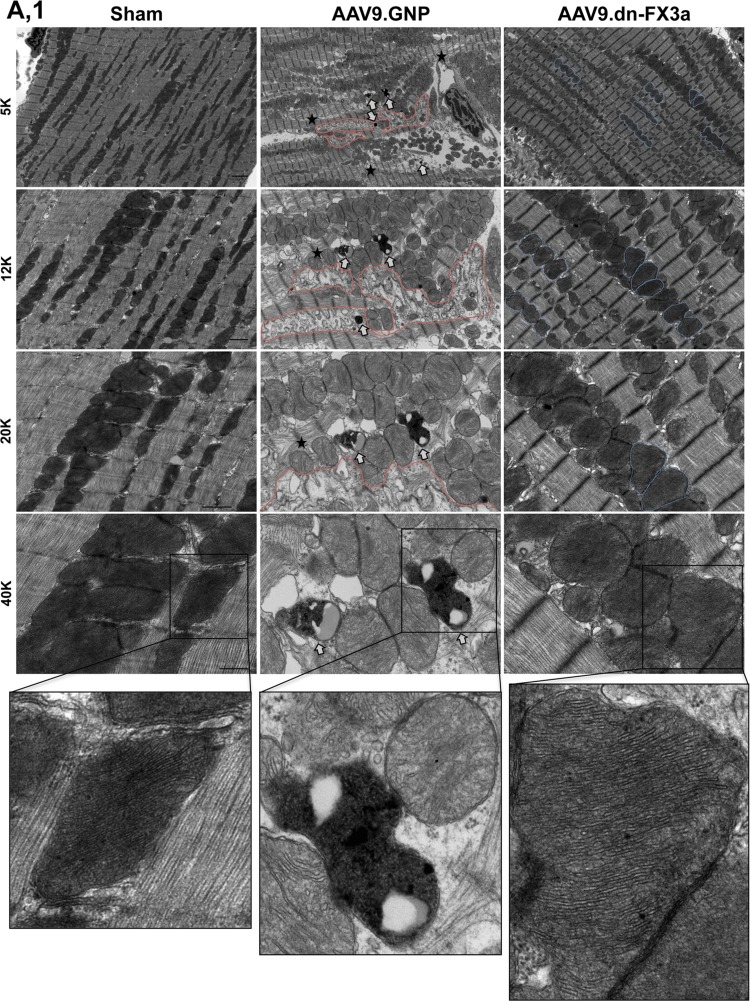

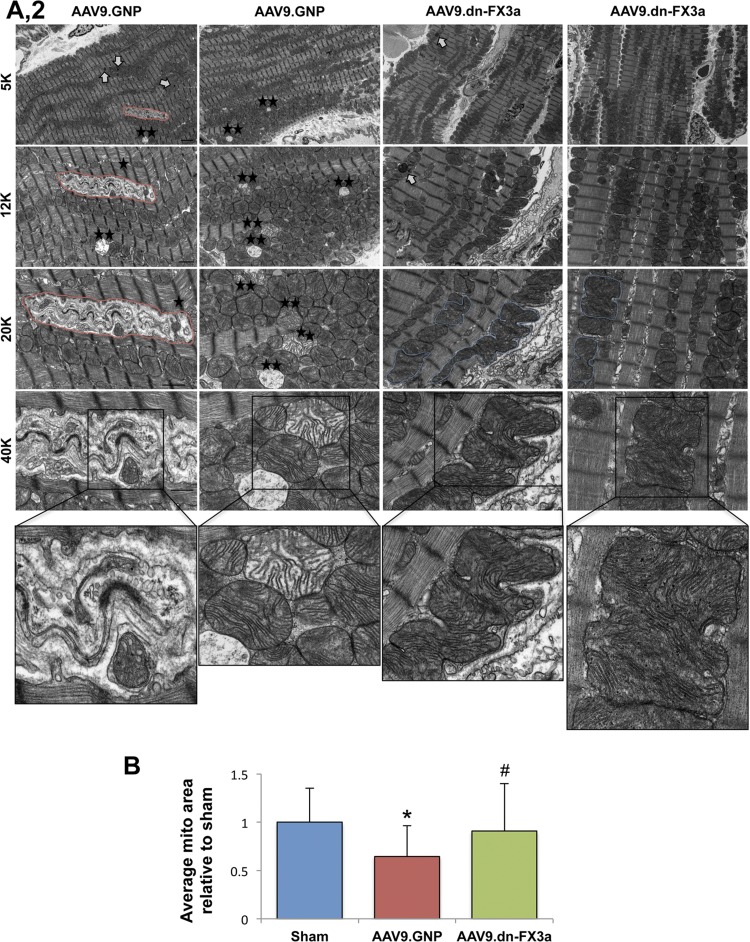

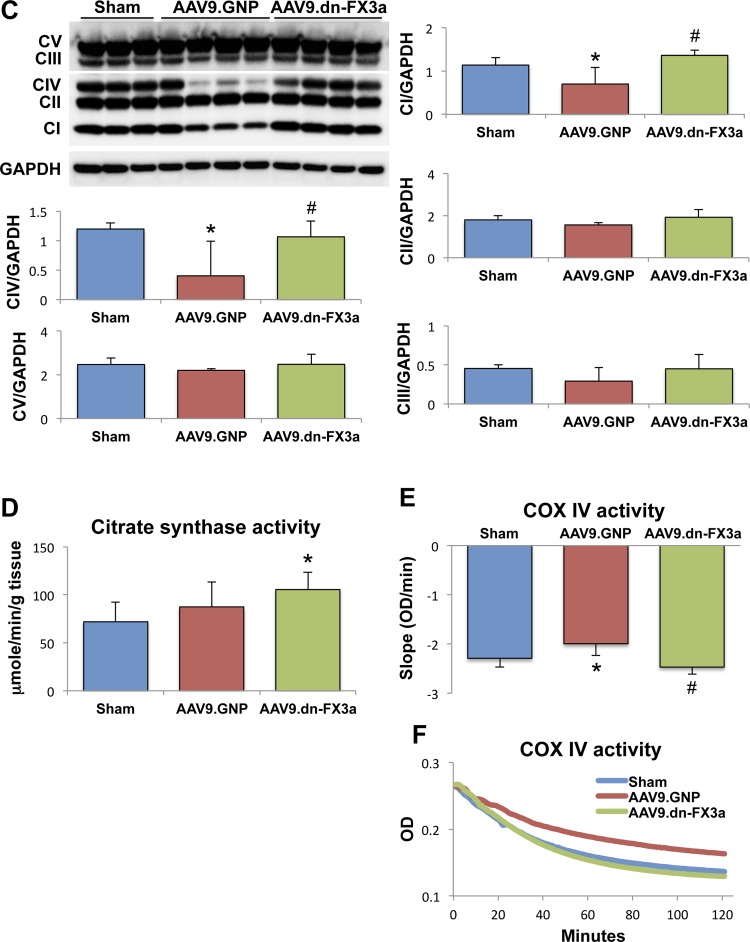

Transmission electron microscopy shows areas with significant mitochondrial fragmentation and cristae destruction, with some mitochondria undergoing vacuolar degeneration in the AAV9.GNP group compared with sham animals (Fig. 8, A1 and A2). The intermyofibrillar mitochondria in those areas were abnormally aligned with the adjacent sarcomeres, which were often disrupted. Moreover, areas with significant autophagolysis and loss of mitochondrial mass were noted. The average mitochondrial area was significantly decreased in AAV9.GNP compared with sham animals (Fig. 8B). In contrast, the AAV9.dn-FX3a-treated group exhibited more normal alignment of intermyofibrillar mitochondria with the adjacent sarcomeres. Moreover, there were areas where the neighboring intermyofibrillar mitochondria were fusing with each other (Fig. 8, A1 and A2), and the average mitochondrial area was increased compared with the AAV9.GNP group (Fig. 8B). Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation revealed that expression of ETC complexes I and IV, as well as complex IV activity, was significantly decreased in the AAV9.GNP compared with the sham group but was preserved in the AAV9.dn-FX3a group (Fig. 8, C, E, and F). Citrate synthase activity was not impaired relative to the sham group in AAV9.GNP rats but was increased in AAV9.dn-FX3a-treated rats (Fig. 8D). Together, these data suggest uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation between the tricarboxylic acid (Krebs) cycle and the ETC, suggesting decreased and inefficient ATP production in the AAV9.GNP group in cardiac oxidative stress, which is restored with AAV9.dn-FX3a therapy.

Fig. 8.

AAV9.dn-FX3a reverses mitochondrial fragmentation and cristae destruction and restores mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation coupling in cardiac stress. A1 and A2: representative transmission electron microscopy images showing areas with significant mitochondrial fragmentation and cristae destruction, areas with significant autophagolysis, and loss of mitochondrial mass (red lines) and autophagolysosomes (white arrows) in the AAV9.GNP group. Some mitochondria were at different stages of vacuolar degeneration (⋆★). ⋆, Areas with disrupted sarcomeres. There was evidence of mitochondrial fusion in the AAV9.dn-FX3a group (blue lines). B: data obtained from A1 and A2. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. 5K, 12K, 20K, and 40K magnification represent scale bars = 2, 1, 1, and 0.5 μm, respectively. C: immunoblot of LV tissue lysate shows significant decreases in electron transport chain (ETC) complexes I (CI) and IV (CIV). *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. Sham. Expression of these complexes was unchanged in AAV9.dn-FX3a compared with sham group. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. D: trend toward increased citrate synthase activity in the AAV9.GNP group and further increase in the AAV9.dn-FX3a group. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. sham. E: significant decrease in ETC complex IV activity in the AAV9.GNP group. *Adjusted P < 0.05 vs Sham. Cytochrome c oxidase (COX) IV activity was unchanged in AAV9.dn-FX3a compared with sham group. #Adjusted P < 0.05 vs. AAV9.GNP. F: representative traces of COX IV activity kinetics. OD, optical density.

Gene Delivery of AAV9.dn-FX3a Restores Protein Phosphorylation at the ER-Mitochondrial Interphase

Given that the gene delivery of dn-FX3a improved myocardial function and mitochondrial dynamics, we tested whether there was a change in expression of Ca2+ cycling proteins and proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics. We found reduced S16 phosphorylation of PLN at the ER level in AAV9.GNP-treated animals, which was restored with AAV9.dn-FX3a treatment. There was no difference in expression of SERCA2a and NCX-1 between AAV9.GNP and AAV9.dn-FX3a groups; however, NCX-1 expression in both groups was significantly increased compared with sham animals (Fig. 9A). At the mitochondrial level, AAV9.dn-FX3a attenuated mitochondrial fission by enhancing S637 phosphorylation of DRP1 but did not affect expression of the fusion proteins mitofusin 2 and OPA1 (Fig. 9B). To examine whether these effects of FOXO3a are mediated by BNIP3, we knocked down BNIP3 in PE-stressed ACM and found more dramatic increases in phosphorylation of PLN and DRP1 at S16 and S637, respectively (Fig. 9C).

Moreover, we found that FOXO3a upregulates mRNA expression of the mitochondrial apoptotic marker Puma, the autophagy-related genes LC3-1 and Lamp2, and the atrophy gene atrogin-1, but not Murf1 or SOD2, in ACM (Fig. 9D).

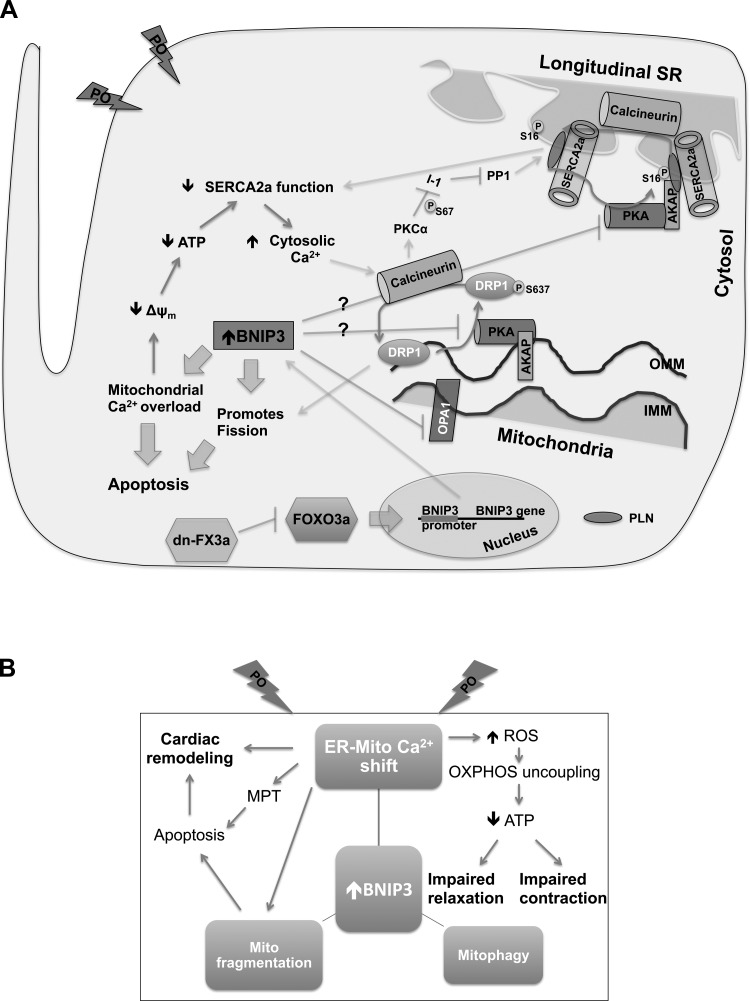

DISCUSSION

While previous studies have supported a role for FOXO3a regulation of BNIP3, here we establish that FOXO3a modulates expression of BNIP3 in cardiac stress. Specifically, we show that expression of ca-FX3a in ACM in vitro upregulates BNIP3 gene expression, whereas gene delivery of dn-FX3a prevents the increase in BNIP3 expression in stressed ACM in vitro and attenuates BNIP3 expression in cardiac stress in vivo. Most (3, 35, 43), but not all (26), studies have shown that hypoxia-inducible factor 1α regulates BNIP3 gene expression in hypoxia. Whether regulation of the BNIP3 gene in ischemia differs from that in POL or whether FOXO3a also regulates BNIP3 gene expression in ischemia is uncertain. To our knowledge, this is the first study to define the role of FOXO3a in cardiac oxidative stress by direct modulation of FOXO3a activity, with particular focus on mitochondrial function and Ca2+ regulation within the ER-mitochondrial interphase. Our results suggest that activation of FOXO3a in PE-stressed ACM in vitro, as well as in cardiac oxidative stress and experimental HFpEF, is maladaptive and that, through BNIP3, it induces an ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ shift, leading to mitochondrial and myocardial diastolic (primarily) and systolic dysfunction. In contrast, gene delivery of dn-FX3a, as well as BNIP3 knockdown, prevented mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial fragmentation in PE-stressed ACM in vitro and improved mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by restoring mitochondrial coupling and efficiency in cardiac stress. Furthermore, we show for the first time that FOXO3a through BNIP3 modulates phosphorylation of PLN and DRP1 at the ER-mitochondrial compartment and, therefore, plays a role in Ca2+ cycling and mitochondrial dynamics. The gene delivery of dn-FX3a restored phosphorylation of PLN at S16 and enhanced phosphorylation of DRP1 at S637, two proteins that are dephosphorylated by calcineurin and phosphorylated by PKA, as previously described (6, 9, 11, 36). Similarly, BNIP3 knockdown robustly increased phosphorylation of PLN at S16 and phosphorylation of DRP1 at S637 in PE-stressed ACM in vitro. It remains unclear whether this effect of FOXO3a-BNIP3 is mediated through the increase in [Ca2+]i and activation of calcineurin or whether it is a direct effect on protein kinases, such as PKA. The proposed sequence of events following the increase in BNIP3 expression in the myocardium is summarized in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Schematic drawing summarizing sequence of events associated with increased BNIP3 expression in cardiac stress. A: FOXO3a is activated under stress condition, such as pressure overload (PO), and contributes to the increase in BNIP3 expression. Subsequently, BNIP3 induced ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ shift, mitochondrial fragmentation/fission (because of mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, BNIP3 mediated inhibition of OPA1 and recruitment of DRP1 to the mitochondria), and apoptosis and mitophagy. Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of Δψm, and decrease in ATP production, which contributes to a decline in SERCA2a activity and, consequently, an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ and decreases in ER Ca2+. We hypothesize that increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ led to activation of calcineurin, a phosphatase that has been shown to dephosphorylate PLN at S16 and DRP1 at S637. It remains unclear whether BNIP3 directly affects activity of PKA, which has been shown to phosphorylate PLN at S16 and DRP1 at S637. BNIP3 knockdown, as well as delivery of dn-FX3a, reverses this pathological signaling and restores ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and phosphorylation of PLN and DRP1 at S16 and S637, respectively, at the ER-mitochondrial interphase. B: a more simplified schematic drawing. MPT, mitochondrial permeability transition; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation. AKAP, A kinase-anchoring protein; IMM and OMM, inner and outer mitochondrial membrane; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

These effects of dn-FX3a on cardiac stress and, therefore, the attenuation of BNIP3 expression and improvement of mitochondrial structure and function as well as Ca2+ cycling were associated with improvement of LV systolic function and, particularly, LV diastolic function in experimental HFpEF. Moreover, there was a decrease in LV interstitial fibrosis. Given the significant improvement of mitochondrial structure and function and myocardial diastolic function and the mild decrease in LV interstitial fibrosis, we believe that the effect on LV interstitial fibrosis is due to the decreased mitochondrial apoptosis, rather than a direct antifibrotic effect.

Beyond regulation of the BNIP3 gene, FOXO3a regulates expression of the mitochondrial proapoptotic gene Puma, the autophagy genes LC3-1 and Lamp2, and the atrophy gene atrogin-1 in ACM. These effects of FOXO3a, beyond BNIP3 gene regulation, contribute to worsening of myocardial function in HF by promoting and amplifying mitochondrial apoptosis and autophagy as well as cardiac atrophy. For this reason, FOXO3a is a more attractive target than BNIP3 alone for treating HF. These findings are consistent with previous findings in lymphoid cells (42) and neurons (1) for Puma, in skeletal muscle (24) for LC3-1, BNIP3, and atrogin-1, and in neonatal cardiomyocytes (37) for atrogin-1. We show for the first time that FOXO3a regulates expression of the lysosomal marker Lamp2, which plays a role in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy (13). Contrary to previous findings in cardiac fibroblasts (10) and neonatal cardiomyocytes (38), we did not find FOXO3a to regulate the expression of the mitochondrial antioxidant marker SOD2 in ACM. Sundaresan et al. (38) showed that overexpression of sirtuin-3 in neonatal cardiomyocytes blunts PE-induced hypertrophy through upregulation of SOD2 expression and attenuation of ROS-induced Ras activation. They propose that the increase in SOD2 expression is FOXO3a-dependent; however, experiments assessing the effect of WT or ca-FX3a expression on SOD2 expression were not performed. Moreover, they show that FOXO3a is inactive (cytoplasmic compartmentalization) in PE-stressed neonatal cardiomyocytes, in contrast with our finding. It remains unclear whether activation of FOXO3a and its associated gene regulation differ in neonatal vs. adult cardiomyocytes. Similarly, we did not find FOXO3a to regulate expression of the Murf1 gene in ACM, in contrast to previous findings in neonatal cardiomyocytes (37).

In conclusion, our results suggest that FOXO3a activation in cardiac stress is maladaptive, and through BNIP3, it mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and Ca2+ cycling dysregulation. Targeting of FOXO3a using dn-FX3a, as opposed to FOXO3a or BNIP3 knockdown, is more physiological; it has the advantage that it bypasses upstream FOXO3a inhibition while it simultaneously acts as a competitor antagonist to WT FOXO3a and has the potential for drug development in the future.

GRANTS

This work is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL-105418-01A1-4, HL-76611-10CB, and HL-7661-10P1 to (M. M. Redfield).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.H.C., K.S.N., and R.J.H. developed the concept and designed the research; A.H.C., E.K., S.I.G., A.J.G., K.A.K., and A.U.F. performed the experiments; A.H.C. analyzed the data; A.H.C., K.S.N., and R.J.H. interpreted the results of the experiments; A.H.C. prepared the figures; A.H.C. drafted the manuscript; A.H.C., R.J.H., and M.M.R. edited and revised the manuscript; M.M.R. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhter R, Sanphui P, Biswas SC. The essential role of p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (Puma) and its regulation by FoxO3a transcription factor in β-amyloid-induced neuron death. J Biol Chem 289: 10812–10822, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alp PR, Newsholme EA, Zammit VA. Activities of citrate synthase and NAD+-linked and NADP+-linked isocitrate dehydrogenase in muscle from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem J 154: 689–700, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2570–2581, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boncompagni S, Rossi AE, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Polishchuk RS, Dirksen RT, Protasi F. Mitochondria are linked to calcium stores in striated muscle by developmentally regulated tethering structures. Mol Biol Cell 20: 1058–1067, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol 11: 507–515, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15803–15808, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaanine AH, Gordon RE, Kohlbrenner E, Benard L, Jeong D, Hajjar RJ. Potential role of BNIP3 in cardiac remodeling, myocardial stiffness, and endoplasmic reticulum: mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in diastolic and systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 6: 572–583, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaanine AH, Jeong D, Liang L, Chemaly ER, Fish K, Gordon RE, Hajjar RJ. JNK modulates FOXO3a for the expression of the mitochondrial death and mitophagy marker BNIP3 in pathological hypertrophy and in heart failure. Cell Death Dis 3: 265, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang CR, Blackstone C. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Drp1 regulates its GTPase activity and mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem 282: 21583–21587, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiribau CB, Cheng L, Cucoranu IC, Yu YS, Clempus RE, Sorescu D. FOXO3A regulates peroxiredoxin III expression in human cardiac fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 283: 8211–8217, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagda RK, Gusdon AM, Pien I, Strack S, Green S, Li C, Van Houten B, Cherra SJ 3rd, Chu CT. Mitochondrially localized PKA reverses mitochondrial pathology and dysfunction in a cellular model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Differ 18: 1914–1923, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Monte F, Butler K, Boecker W, Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ. Novel technique of aortic banding followed by gene transfer during hypertrophy and heart failure. Physiol Genomics 9: 49–56, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eskelinen EL, Illert AL, Tanaka Y, Schwarzmann G, Blanz J, Von Figura K, Saftig P. Role of LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3355–3368, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuyama T, Kitayama K, Shimoda Y, Ogawa M, Sone K, Yoshida-Araki K, Hisatsune H, Nishikawa S, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Ikeda K, Motoyama N, Mori N. Abnormal angiogenesis in Foxo1 (Fkhr)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 279: 34741–34749, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galasso G, De Rosa R, Piscione F, Iaccarino G, Vosa C, Sorriento D, Piccolo R, Rapacciuolo A, Walsh K, Chiariello M. Myocardial expression of FOXO3a-Atrogin-1 pathway in human heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 12: 1290–1296, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J. FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol 162: 613–622, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene 24: 7410–7425, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi T, Martone ME, Yu Z, Thor A, Doi M, Holst MJ, Ellisman MH, Hoshijima M. Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J Cell Sci 122: 1005–1013, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosaka T, Biggs WH 3rd, Tieu D, Boyer AD, Varki NM, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. Disruption of forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family members in mice reveals their functional diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 2975–2980, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JS, Wang JH, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in rat hepatocytes after anoxia/reoxygenation: role of Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G723–G731, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim M, Oh JK, Sakata S, Liang I, Park W, Hajjar RJ, Lebeche D. Role of resistin in cardiac contractility and hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 270–280, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemasters JJ, Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Nieminen AL. Mitochondrial calcium and the permeability transition in cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 1395–1401, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukyanenko V, Chikando A, Lederer WJ. Mitochondria in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1957–1971, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, Burden SJ, Di Lisi R, Sandri C, Zhao J, Goldberg AL, Schiaffino S, Sandri M. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab 6: 458–471, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murgia M, Giorgi C, Pinton P, Rizzuto R. Controlling metabolism and cell death: at the heart of mitochondrial calcium signalling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 781–788, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Namas RA, Metukuri MR, Dhupar R, Velosa C, Jefferson BS, Myer E, Constantine GM, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y, Zamora R. Hypoxia-induced overexpression of BNIP3 is not dependent on hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in mouse hepatocytes. Shock 36: 196–202, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 3: 1422–1434, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene 27: 6407–6418, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pramod S, Shivakumar K. Mechanisms in cardiac fibroblast growth: an obligate role for Skp2 and FOXO3a in ERK1/2 MAPK-dependent regulation of p27kip1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H844–H855, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapti K, Louis-Jeune V, Kohlbrenner E, Ishikawa K, Ladage D, Zolotukhin S, Hajjar RJ, Weber T. Neutralizing antibodies against AAV serotypes 1, 2, 6, and 9 in sera of commonly used animal models. Mol Ther 20: 73–83, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronnebaum SM, Patterson C. The FoxO family in cardiac function and dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 81–94, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rooyackers OE, Senden JM, Soeters PB, Saris WH, Wagenmakers AJ. Prolonged activation of the branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex in muscle of zymosan treated rats. Eur J Clin Invest 25: 548–552, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanphui P, Biswas SC. FoxO3a is activated and executes neuron death via Bim in response to β-amyloid. Cell Death Dis 4: e625, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santulli G, Xie W, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 11389–11394, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaida N, Launchbury R, Boddy JL, Jones C, Campo L, Turley H, Kanga S, Banham AH, Malone PR, Harris AL, Fox SB. Expression of BNIP3 correlates with hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, HIF-2α and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer and is regulated directly by hypoxia but not androgens in cell lines. Prostate 68: 336–343, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shintani-Ishida K, Yoshida K. Ischemia induces phospholamban dephosphorylation via activation of calcineurin, PKCα, and protein phosphatase 1, thereby inducing calcium overload in reperfusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 743–751, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skurk C, Izumiya Y, Maatz H, Razeghi P, Shiojima I, Sandri M, Sato K, Zeng L, Schiekofer S, Pimentel D, Lecker S, Taegtmeyer H, Goldberg AL, Walsh K. The FOXO3a transcription factor regulates cardiac myocyte size downstream of AKT signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 20814–20823, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundaresan NR, Gupta M, Kim G, Rajamohan SB, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 2758–2771, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabadkai G, Duchen MR. Mitochondria: the hub of cellular Ca2+ signaling. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 84–94, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran H, Brunet A, Grenier JM, Datta SR, Fornace AJ Jr, DiStefano PS, Chiang LW, Greenberg ME. DNA repair pathway stimulated by the forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a through the Gadd45 protein. Science 296: 530–534, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Zhou Y, Graves DT. FOXO transcription factors: their clinical significance and regulation. Biomed Res Int 2014: 925350, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You H, Pellegrini M, Tsuchihara K, Yamamoto K, Hacker G, Erlacher M, Villunger A, Mak TW. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. J Exp Med 203: 1657–1663, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou YF, Zheng XW, Zhang GH, Zong ZH, Qi GX. The effect of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α on hypoxia-induced apoptosis in primary neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc J Afr 21: 37–41, 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]