Systemic sclerosis is characterized by debilitating fibrosis and vascular dysfunction; however, little is known about the circulatory response to exercise in this population. This study reveals attenuated brachial artery blood flow and arterial vasodilatory dysfunction during handgrip exercise in SSc and suggests elevated oxidative stress may play a role.

Keywords: handgrip, oxidative stress

Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by debilitating fibrosis and vascular dysfunction; however, little is known about the circulatory response to exercise in this population. Therefore, we examined the peripheral hemodynamic and vasodilatory responses to handgrip exercise in 10 patients with SSc (61 ± 4 yr) and 15 age-matched healthy controls (56 ± 5 yr). Brachial artery diameter, blood flow, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were determined at rest and during progressive static-intermittent handgrip exercise. Patients with SSc and controls were similar in body stature, handgrip strength, and MAP; however, brachial artery blood flow at rest was nearly twofold lower in patients with SSc compared with controls (22 ± 4 vs. 42 ± 5 ml/min, respectively; P < 0.05). Additionally, SSc patients had an ∼18% smaller brachial artery lumen diameter with an ∼28% thicker arterial wall at rest (P < 0.05). Although, during handgrip exercise, there were no differences in MAP between the groups, exercise-induced hyperemia and therefore vascular conductance were ∼35% lower at all exercise workloads in patients with SSc (P < 0.05). Brachial artery vasodilation, as assessed by the relationship between Δbrachial artery diameter and Δshear rate, was significantly attenuated in the patients with SSc (P < 0.05). Finally, vascular dysfunction in the patients with SSc was accompanied by elevated blood markers of oxidative stress and attenuated endogenous antioxidant activity (P < 0.05). Together, these findings reveal attenuated exercise-induced brachial artery blood flow and conduit arterial vasodilatory dysfunction during handgrip exercise in SSc and suggest that elevated oxidative stress may play a role.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Systemic sclerosis is characterized by debilitating fibrosis and vascular dysfunction; however, little is known about the circulatory response to exercise in this population. This study reveals attenuated brachial artery blood flow and arterial vasodilatory dysfunction during handgrip exercise in SSc and suggests elevated oxidative stress may play a role.

systemic sclerosis [scleroderma (SSc)] is a rare autoimmune disease that results in debilitating fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, and a median survival of ∼11 years postdiagnosis (33). Although there is heterogeneity in the extent to which organs are involved, vascular dysfunction is present in nearly all patients (20, 26). Recently, we have identified impaired brachial arterial reactive hyperemia and flow-mediated vasodilation in patients with SSc (19). These results indicate that peripheral vascular dysfunction in patients with SSc is present in both the microcirculation (i.e., impaired reactive hyperemia) and conduit arteries (i.e., impaired brachial artery vasodilation). Whether blood flow and vascular function are also compromised in this population during exercise is unknown.

Progressive handgrip exercise is a common exercise model that incorporates a small muscle mass and, therefore, requires a fraction of maximal cardiac output, limiting the impact of central hemodynamic factors (50). This model also allows stepwise increases in exercise workload, providing the opportunity to assess exercise-induced blood flow and, in combination with mean arterial pressure (MAP) measurements, vascular conductance at several exercise intensities. Additionally, because each progressive increase in exercise workload results in a proportional increase in steady-state brachial artery blood flow, the handgrip model allows conduit artery function (i.e., brachial artery vasodilation) to be assessed in response to sustained elevations in shear rate. Using this model, our group has studied the peripheral hemodynamic response to exercise and identified exercise-induced vascular dysfunction in aging (17, 42, 43) and heart failure (3).

Because little is known about the circulatory response to exercise in patients with SSc, using the handgrip exercise model, we sought to examine the exercise-induced hemodynamic and vasodilatory response in this population compared with well-matched healthy controls. We hypothesized that, compared with age- and sex-matched healthy controls, patients with SSc would exhibit attenuated exercise-induced brachial artery blood flow and vascular conductance in addition to brachial artery vascular dysfunction.

METHODS

Subjects.

Ten patients with SSc were recruited from the University of Utah SSc Clinic. Patients had either a diagnosis of SSc as accepted by the American College of Rheumatology or early SSc as described by Leroy and Medsger (2, 28). Fifteen age- and sex-matched healthy controls were recruited from the general population. The controls were recruited based upon no evidence of vascular disease or chronic medical conditions and were not taking any medications that would impact vascular function. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah and Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The nature, benefits, and risks of the study were explained to the subjects, and their written informed consent was obtained before participation. All subjects were nonsmokers and were asked to refrain from alcohol and/or caffeine consumption within 12 h of testing. Additionally, vasodilatory medications were discontinued 12 h before the study visit. In premenopausal women, measurements were performed during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

Subject characteristics.

For all subjects body mass index was calculated from body mass and height, and maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) for the handgrip exercise was measured, as described previously (50). For patients with SSc, clinical features were measured/recorded, including disease duration, medical history (digital ulcers, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and scleroderma renal crisis), and SSc-antibodies status.

Progressive handgrip exercise.

Subjects reported to the laboratory >5 h postprandial. Static intermittent handgrip exercise was then performed at 1 Hz, as described previously (50). Subjects were encouraged to perform rapid contractions with the goal of limiting contraction time to <25% of the duty cycle. Subjects exercised at 15, 30, and 45% of their MVC. Each exercise stage was performed for 3 min with a 2-min break allotted between each workload.

Measurements.

Heart rate (HR) was monitored with a three-lead ECG. Mean arterial blood pressure was measured on the contralateral arm by auscultation of the brachial artery (Tango+; SunTech, Morrisville, NC). Simultaneous measurements of brachial artery blood velocity and vessel diameter were performed using a linear array transducer operating in duplex mode, with imaging frequency of 14 MHz and Doppler frequency of 5 MHz (Logic 7; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). All measurements were obtained with the probe appropriately positioned to maintain an insonation angle of ≤60°. The sample volume was maximized according to vessel size and was centered within the vessel on the basis of real-time ultrasound visualization. Brachial artery wall thickness was assessed as the distance between the intima and media. The brachial artery was insonated approximately midway between the antecubital and axillary regions at rest and during the final minute of each exercise workload. Shear rate was calculated according to the equation: shear rate (s−1) = blood velocity × 4/vessel diameter. Brachial artery blood flow was calculated as per the equation: blood flow (ml/min) = [blood velocity × π × (vessel diameter/2)2 × 60]. Brachial artery vascular conductance was calculated according to the equation: blood flow/MAP.

Oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, and inflammation assays.

Blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein in a subset of both controls (n = 6) and patients with SSc (n = 6). Serum and plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Oxidative stress was assessed by quantifying plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) (Oxis Research/Percipio Bioscience, Foster City, CA) and protein carbonyl levels (Northwest Life Science Specialties, Vancouver, WA). Endogenous antioxidant capacity, assessed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activity, were assayed in the plasma (47) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Additionally, total antioxidant capacity was assessed by measuring the ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP), using the method described by Benzie and Strain (5). Systemic inflammation was assessed by determining TNF-α (12) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in serum (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistics.

Statistics were performed using SPSS software (IBM, Chicago, IL). Unpaired t-tests were used to compare differences in subject characteristics, cardiovascular variables at rest, blood assays, and the slope of the relationship of Δbrachial artery diameter to Δshear rate between SSc and controls. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations between blood markers and functional outcomes. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to evaluate differences between SSc and controls during exercise, and a least-significant-difference unpaired t-test identified the means that were significantly different. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Patients with SSc and controls were well-matched for age, sex, body stature, and handgrip MVC (P > 0.05; Table 1). Among patients with SSc, the duration of SSc ranged from 1 to 14 years.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Controls | Systemic Sclerosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Women/men | 10/5 | 7/3 |

| Age, yr | 56 ± 5 | 61 ± 4 |

| Height, cm | 169 ± 3 | 170 ± 3 |

| Weight, kg | 68.6 ± 3.0 | 69.4 ± 3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.0 ± 0.7 | 24.0 ± 0.9 |

| MVC, kg | 19.1 ± 1.1 | 17.3 ± 2.0 |

| Disease duration, yr | 5 ± 1 | |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 7 (70) | |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 0 (0) | |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | 0 (0) | |

| Immunosuppression | 4 (40) | |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||

| Digital ulcer | 6 (60) | |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1 (10) | |

| Scleroderma renal crisis | 1 (10) | |

| Antibody presence, n (%) | ||

| Antinuclear antibody | 10 (100) | |

| Centromere | 5 (50) | |

| RNA polymerase III | 1 (10) | |

| SCL70 | 2 (20) | |

| Fibrillin | 2 (20) | |

| Th/To | 0 (0) | |

| RNP | 1 (10) |

Values are presented as means ± SE.

BMI, body mass index; MVC, maximal voluntary contraction.

Oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, and inflammation.

Lipid peroxidation, as measured by plasma MDA levels, was significantly higher in patients with SSc compared with controls (P < 0.05; Table 2). Likewise, there was a trend for higher plasma protein carbonyl levels in patients with SSc (P = 0.06). Additionally, endogenous antioxidant activity, as measured by plasma CAT levels, was significantly lower in patients with SSc (P < 0.05). There were no differences in plasma FRAP or SOD levels between groups (P > 0.05). There was a trend for higher serum TNF-α and CRP levels in patients with SSc (P = 0.08–0.11). There were no significant correlations between any blood marker and functional outcome (all P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Blood oxidative stress, antioxidant status, and inflammatory markers

| Controls | Systemic Sclerosis | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDA, μM | 1.27 ± 0.26 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | <0.05 |

| Protein carbonyl, nM/mg | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.06 |

| CAT, nM·min−1·ml−1 | 117 ± 17 | 76 ± 8 | <0.05 |

| FRAP, nM/l | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | |

| SOD, U/ml | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.6 | |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.08 |

| CRP, mg/l | 1.62 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.11 |

Values are presented as means ± SE.

MDA, malondialdehyde; CAT, catalase; FRAP, ferric reducing ability of plasma; SOD superoxide dismutase, CRP, C-reactive protein.

P values are vs. controls.

Cardiovascular variables at rest.

Selected cardiovascular variables of patients with SSc and controls at rest are presented in Table 3. In SSc patients, HR was elevated at rest compared with controls (P < 0.05), but there were no differences in MAP between groups (P > 0.05). Resting brachial artery lumen diameter was significantly smaller in SSc compared with controls (P < 0.05), and patients with SSc had greater wall thickness and wall-to-lumen ratio than controls (P < 0.05). Resting brachial artery blood velocity, blood flow, and vascular conductance were all significantly lower in SSc compared with controls (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular variables at rest

| Controls | Systemic Sclerosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 54 ± 2 | 65 ± 3* |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 115 ± 3 | 113 ± 4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75 ± 2 | 71 ± 2 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 89 ± 2 | 85 ± 2 |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 3.72 ± 0.17 | 3.06 ± 0.16* |

| Wall thickness, mm | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.02* |

| Wall-to-lumen ratio, mm | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02* |

| Blood velocity, cm/s | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.4* |

| Shear rate, s−1 | 72 ± 9 | 62 ± 5 |

| Brachial artery blood flow, ml/min | 42 ± 5 | 22 ± 4* |

| Brachial artery vascular conductance, ml·min−1·mmHg−1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0* |

Values are presented as means ± SE.

P < 0.05 vs. controls.

Cardiovascular variables during handgrip exercise.

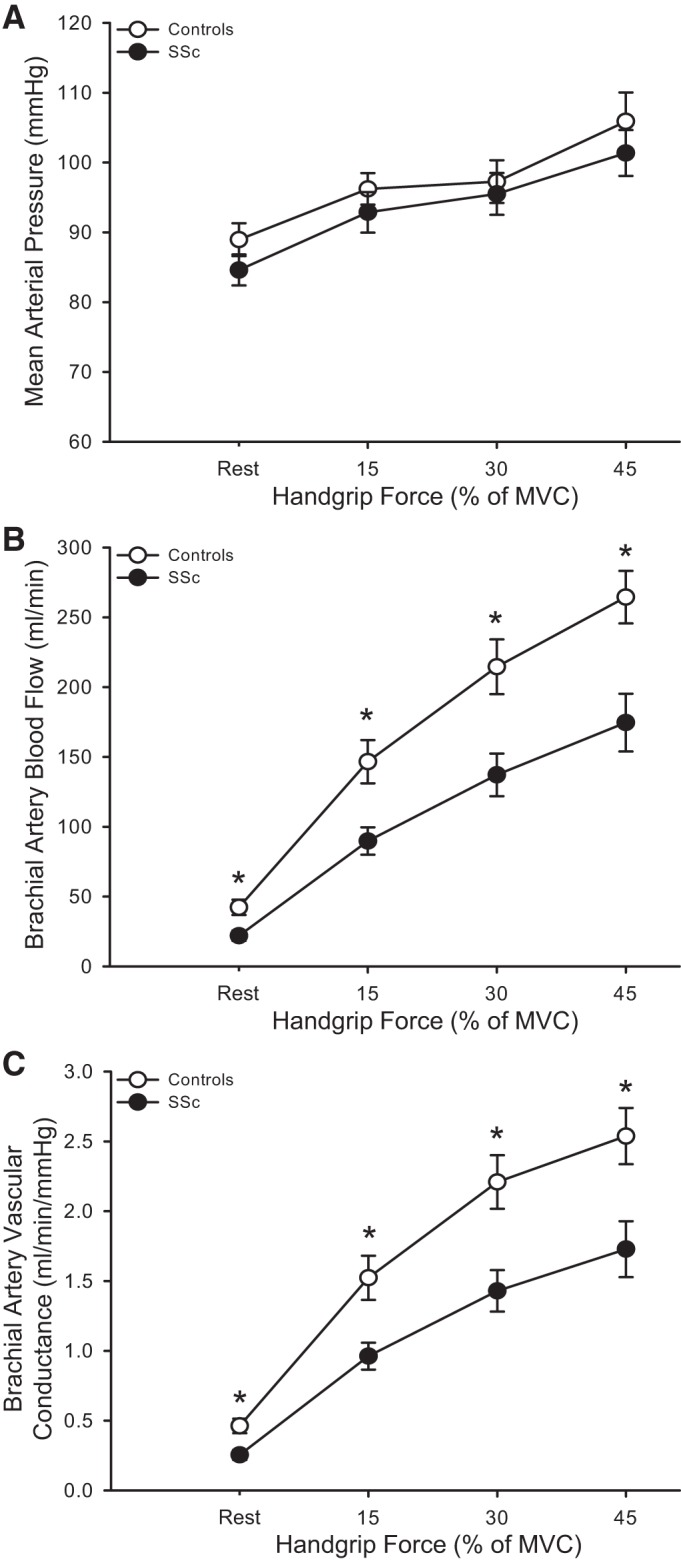

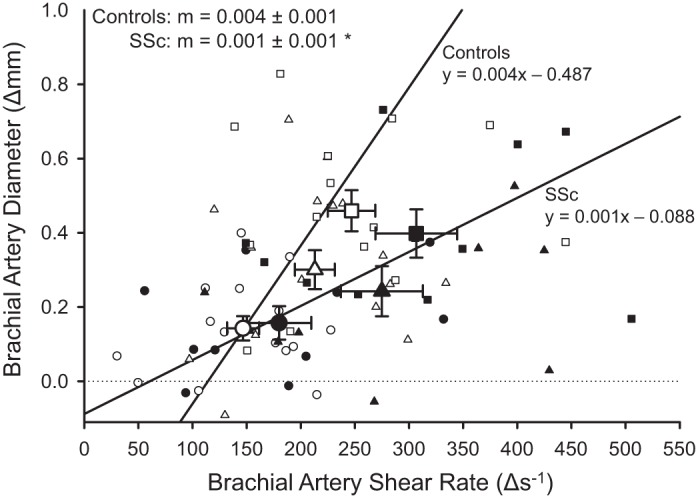

Exercise-induced blood flow was ∼36% lower at each handgrip workload in patients with SSc compared with controls (P < 0.05, Fig. 1B). When expressed as a change from baseline, exercise-induced blood flow was lower at each handgrip workload in patients with SSc compared with controls (15% MVC: 68 ± 9 vs. 104 ± 13; 30% MVC: 115 ± 15 vs. 172 ± 17; 45% MVC: 153 ± 20 vs. 222 ± 16 ml/min, respectively; P < 0.05). Because there was no difference in MAP between the patients with SSC and controls, there was an ∼35% reduction in vascular conductance at each workload in SSc (P < 0.05, Fig. 1C). When expressed as a change from baseline, exercise-induced vascular conductance was lower at each handgrip workload in patients with SSc compared with controls (15% MVC: 0.7 ± 0.1 vs. 1.1 ± 0.1; 30% MVC: 1.2 ± 0.1 vs. 1.7 ± 0.2; 45% MVC: 1.5 ± 0.2 vs. 2.1 ± 0.2 ml·min−1·mmHg−1, respectively; P < 0.05). Similar to rest, at all exercise workloads lumen diameter was significantly smaller in SSc compared with controls (P < 0.05, Table 4). There were no differences in brachial artery vasodilation or blood velocity during exercise between groups (P > 0.05). Although shear rate tended to be higher during exercise in patients with SSc, these differences did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05). However, the relationship between Δbrachial artery diameter and Δshear rate exhibited a significant downward shift in patients with SSc (P < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial pressure (A), brachial artery blood flow (B), and brachial artery vascular conductance (C) at rest and during progressive handgrip exercise in healthy controls and patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). *P < 0.05, significant difference between controls and SSc. All data are presented as means ± SE.

Table 4.

Cardiovascular variables during exercise

| Exercise Intensity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative %MVC: | 15 | 30 | 45 |

| Controls | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 63 ± 2 | 62 ± 3 | 66 ± 3 |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 3.86 ± 0.16 | 4.02 ± 0.15 | 4.18 ± 0.14 |

| Vasodilation, % | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 13.3 ± 2.0 |

| Blood velocity, cm/s | 20.5 ± 1.4 | 28.0 ± 1.7 | 32.4 ± 1.7 |

| Shear rate, s−1 | 219 ± 17 | 285 ± 20 | 319 ± 24 |

| Systemic sclerosis | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 69 ± 3* | 71 ± 3* | 73 ± 3† |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 3.22 ± 0.15* | 3.31 ± 0.16* | 3.46 ± 0.17* |

| Vasodilation, % | 5.5 ± 1.7 | 8.4 ± 2.5 | 13.4 ± 2.5 |

| Blood velocity, cm/s | 18.8 ± 2.0 | 26.9 ± 2.4 | 30.9 ± 2.5 |

| Shear rate, s−1 | 242 ± 32 | 337 ± 39 | 369 ± 38 |

Values are presented as means ± SE.

P < 0.05 vs. controls.

P = 0.07.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the changes in brachial artery shear rate and the associated change in brachial artery vasodilation during each handgrip exercise stage [15% (circles), 30% (triangles), and 45% (squares) of maximum voluntary contraction] in healthy controls (white symbols) and patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc; black symbols). Large symbols are means ± SE, and small symbols indicate individual data. Patients with SSc had a significantly lower slope (m) compared with controls. *P < 0.05, significantly different from controls.

DISCUSSION

There are several novel observations from this study. First, we have documented attenuated resting exercise-induced brachial artery blood flow in patients with SSc. Second, we have documented that brachial artery vasodilation, in response to sustained exercise-induced increases in shear rate, is also attenuated in patients with SSc compared with controls, suggestive of a dysfunctional endothelium. Additionally, we observed structural differences in the brachial artery, such as a smaller lumen diameter and a thicker arterial wall, which may impact vasodilation. Finally, the SSc patients exhibited evidence of elevated oxidative stress and attenuated antioxidant capacity in the blood. Therefore, in combination, these data reveal that exercise-induced blood flow and conduit artery vascular function are impaired in SSc, and, although there are several potential mechanisms that may be responsible for these findings, it appears likely that increased oxidative stress may play a role.

Resting hemodynamics and arterial structure.

Dysfunctional vasoconstrictor and vasodilator signaling in digital resistance arteries is well established in patients with SSc (28). While others have observed impairments in digital blood flow at rest in SSc (22, 48), the results of the present study extend those findings and are the first to identify impaired resting brachial artery blood flow and vascular conductance in patients with SSc (Table 3 and Fig. 1, B and C). With the reasonable assumption that forearm oxygen demand was similar in both patients and controls, which alone can dictate blood flow, these findings imply that vasoconstriction of resistance arteries downstream from the brachial artery limit peripheral blood flow and vascular conductance in this population.

We also report structural abnormalities in the brachial arteries of patients with SSc. In our previous study (19), we found that SSc patients had smaller brachial artery lumen diameters than controls. The current results extend those findings by presenting that, in addition to a smaller brachial artery lumen diameter, SSc patients exhibit a greater brachial wall thickness and wall-to-lumen ratio. These findings are suggestive of inward remodeling of the brachial artery, which may be a structural adaptation to reduced brachial artery blood flow by way of downstream resistance arterial vasoconstriction (27). We should note that other possibilities for inward remodeling exist, such as muscle sympathetic nerve activity (16), which is elevated in SSc (10). Hand stiffness and skin tightening that limit the use of the hands in SSc patients (4) could lead to inward remodeling and wall thickening similar to models of inactivity like bed rest (45) or spinal cord injury (39). Given the multitude of physiological complexities associated with bed rest and spinal cord injury (40), this comparison is merely speculative. Nevertheless, the current findings suggest that increased resistance artery vasoconstrictor tone impairs brachial artery blood flow at rest and is accompanied by alterations in the structural characteristics of the brachial artery in patients with SSc. Whether inward remodeling occurs with SSc and through which mechanism warrant further investigation.

Role of resistance arterial dysfunction on exercise hyperemia.

Previously we have observed impaired reactive hyperemia in SSc (19). In the current study, to further evaluate peripheral resistance arterial vasodilatory function, we measured exercise hyperemia in response to progressive handgrip exercise. In patients with SSc, impaired exercise hyperemia was present at all workloads (Fig. 1B). Because this exercise model incorporates a small amount of muscle mass and requires a minimal fraction of maximal cardiac output, impairments in exercise hyperemia are likely due to resistance artery vasoconstriction downstream of the brachial artery. In support of this, we also observed an impaired ability to increase brachial artery vascular conductance in response to handgrip exercise (Fig. 1C). Indeed, assuming a similar metabolic demand, increases in vascular conductance in response to exercise reflect the ability of resistance arteries to vasodilate (24); thus, these data further support the idea that resistance artery vasodilatory function is impaired in SSc. It is likely that dysfunctional vasodilation of resistance arteries initially impairs blood flow at rest and then continues to limit the appropriate increase in vascular conductance during exercise, impairing exercise-induced hyperemia.

Brachial artery vascular function assessed during handgrip exercise.

During handgrip exercise, there is a proportional increase in steady-state brachial artery blood flow at each successive exercise workload, resulting in a sustained elevation in shear rate, at the level of the brachial artery, which provokes endothelium-dependent dilation (17, 43, 50). At first glance, exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation, expressed simply as percent change in diameter across exercise intensities, appeared to be preserved in patients with SSc (Table 4); however, when vasodilation was viewed in relation to shear rate, the vasodilatory response was significantly attenuated in the patients with SSc compared with controls (Fig. 2). Brachial artery vasodilation, in response to an increase in shear rate during handgrip exercise, has been documented to be mediated by nitric oxide (NO) (42, 50). Thus, an impaired vasodilatory response to an increased shear rate is indicative of brachial artery endothelial dysfunction (42, 50).

Interestingly, using the postcuff occlusion brachial artery flow-mediated dilation technique, an assessment of endothelial function, we have previously observed an impaired response in patients with SSc, both in absolute terms and when normalized for shear rate (19). With regard to the lack of a difference in percent change in brachial artery diameter across exercise intensities between SSc and controls, it should be noted that the patients with SSc had significantly smaller brachial arteries, which, mathematically, augments the apparent vasodilation when expressed as percent change (11). Additionally, the brachial arteries of the patients with SSc had thicker walls (Table 3). Greater wall thickness is indicative of increased vascular tone and may represent another barrier to vasodilation, since wall thickness is also inversely related to vasodilation (41). Taken together, these findings indicate that functional and structural abnormalities of the brachial artery may impair vasodilation in patients with SSc and are indicative of poor vascular health. However, it is noteworthy that dysfunction of the brachial artery is unlikely to impact exercise hyperemia, since it is the vasodilation of resistance arteries of the forearm and hand that govern the increase in brachial artery blood flow in response to exercise and not the conduit itself (35).

Role of oxidative stress and inflammation.

The vascular dysfunction of the patients with SSc was accompanied by bloodborne evidence of oxidative stress and attenuated antioxidant capacity, as well as a trend for elevated inflammation (Table 2). Whereas the functional consequences of oxidative stress are widespread, the vascular endothelium is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage from reactive oxygen species (7). Indeed, elevations in oxidative stress have been implicated in abnormal NO metabolism and the upregulation of vasoconstrictors, including endothelin-1 and asymmetric dimethylarginine, in patients with SSc (18, 34, 37). Interestingly, in healthy young subjects an unbalanced redox state, in favor of oxidative stress, has been recognized to contribute to brachial artery blood flow and brachial artery vasodilation during handgrip exercise (17, 44), but there is also clearly a point at which oxidative stress and inflammation impair the vascular response to exercise (43). Although it is beyond the scope of the present study to determine the mechanisms responsible for this potential oxidative stress-induced vascular dysfunction and remodeling in SSc, it is likely that these mechanisms play a major role in SSc-related vascular dysfunction at rest and during exercise, and are deserving of further study. For example, oxidative stress can result in or be a consequence of insufficient endothelial tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4 is an essential cofactor for endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) (13) and is critical for maintaining NO bioavailability in the vascular endothelium (31). When the concentration of BH4 is insufficient in the endothelial cell, eNOS becomes “uncoupled” and no longer produces NO, but rather produces superoxide (46). Restoring BH4 concentrations has been reported to recouple eNOS, lower oxidative stress, and ultimately improve endothelial function in rats (38). Oral BH4 supplementation improves brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (29), an autoimmune disease that, similar to SSc, is characterized by oxidative stress and inflammation (36). Further investigation into whether BH4 administration would ameliorate vascular dysfunction in patients with SSc is warranted.

Implications.

In addition to vascular dysfunction, patients with SSc have an attenuated exercise capacity (6). Of importance, exercise capacity is inversely related to mortality rate in healthy men and women (23, 32), and this relationship also appears to be evident in patients with SSc (9, 49). Previous studies have implicated central mechanisms (i.e., cardiopulmonary abnormalities) in this diminished exercise tolerance with SSc (1, 8, 14, 25); however, others have found that exercise capacity can be attenuated independently from central impairments (15). Although this study did not assess whole body exercise capacity, considering the prevalence of peripheral perfusion abnormalities in SSc (22, 48), as well as the current findings, it is reasonable to speculate that peripheral vascular dysfunction may play a role in the attenuated exercise capacity associated with SSc. Surprisingly, no other studies have examined whether peripheral mechanisms (i.e., limb blood flow) limit exercise capacity in SSc. Although the effects of cardiopulmonary abnormalities on exercise capacity are undeniable, clearly peripheral mechanisms should not be overlooked and instead could be targeted by adjuvant therapies.

Experimental considerations.

This study is not without limitations. We did not measure forearm muscle mass of controls or patients with SSc. We have previously shown that exercise-induced hyperemia is unrelated to muscle mass and that normalizing blood flow to muscle mass actually increases variance; however, blood flow at rest is dependent on muscle mass (21). Although we did not measure muscle mass, we observed similar MVC and body stature between SSc and healthy subjects. Therefore, it is unlikely that forearm muscle mass was markedly different between groups, however, the possibility exists. We observed an impairment in brachial artery vasodilation to increased shear rate in SSc; however, we did not measure vasodilation to a NO donor (e.g., sublingual nitroglycerin). Although it is possible that impaired brachial artery vasodilation was the result of impaired smooth muscle vasoreactivity, a recently published meta-analysis has indicated that smooth muscle vasoreactivity is preserved in SSc (30). Therefore, it is unlikely that impaired brachial artery vasodilation to increases in shear rate is because of smooth muscle vasodilatory dysfunction.

In conclusion, exercise-induced blood flow and vascular conductance are attenuated in patients with SSc compared with healthy age-matched controls, which appears to be mediated by an inability to appropriately increase vascular conductance. Additionally, brachial artery vasodilation in response to the sustained increases in shear rate that occur during handgrip exercise is impaired. Furthermore, brachial artery structural abnormalities, such as a smaller lumen diameter and a thicker arterial wall, and elevated blood markers of oxidative stress and attenuated antioxidant capacity were evident in the patients with SSc. Therefore, in combination, these data reveal that exercise-induced blood flow and conduit artery vascular function are impaired in SSc, and, although there are several potential mechanisms that may be responsible for these findings, it appears likely that increased oxidative stress may play a role.

GRANTS

This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG-040297, R01-HL-118313, P01-HL-091830, R21-AG-043952, and K02-AG-045339) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (I01 RX001697 and I01 CX001183).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.R., D.W.W., T.M.F., and A.J.D. conception and design of research; D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.G., J.R.G., and T.M.F. performed experiments; D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.G., J.R.G., D.W.W., T.M.F., and A.J.D. analyzed data; D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.R., D.W.W., T.M.F., and A.J.D. interpreted results of experiments; D.R.M. prepared figures; D.R.M., H.L.C., D.W.W., and A.J.D. drafted manuscript; D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.G., J.R.G., R.S.R., D.W.W., T.M.F., and A.J.D. edited and revised manuscript; D.R.M., H.L.C., R.S.G., J.R.G., R.S.R., D.W.W., T.M.F., and A.J.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkotob ML, Soltani P, Sheatt MA, Katsetos MC, Rothfield N, Hager WD, Foley RJ, Silverman DI. Reduced exercise capacity and stress-induced pulmonary hypertension in patients with scleroderma. Chest 130: 176–181, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Arthritis Rheum 23: 581–590, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Lee JF, Berbert A, Witman MA, Nativi-Nicolau J, Stehlik J, Richardson RS, Wray DW. Hemodynamic responses to small muscle mass exercise in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1512–H1520, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer SS, Schieir O, Baron M, Thombs BD. Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology 50: 762–767, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem 239: 70–76, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blom-Bülow B, Jonson B, Brauer K. Factors limiting exercise performance in progressive systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 13: 174–181, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 87: 840–844, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callejas-Rubio JL, Moreno-Escobar E, de la Fuente PM, Perez LL, Fernandez RR, Sanchez-Cano D, Mora JP, Ortego-Centeno N. Prevalence of exercise pulmonary arterial hypertension in scleroderma. J Rheumatol 35: 1812–1816, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campo A, Mathai SC, Le Pavec J, Zaiman AL, Hummers LK, Boyce D, Housten T, Champion HC, Lechtzin N, Wigley FM. Hemodynamic predictors of survival in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 252–260, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casale R, Generini S, Luppi F, Pignone A, Matucci-Cerinic M. Pulse cyclophosphamide decreases sympathetic postganglionic activity, controls alveolitis, and normalizes vascular tone dysfunction (Raynaud's phenomenon) in a case of early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 51: 665–669, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 340: 1111–1115, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Xun K, Chen L, Wang Y. TNF-alpha, a potent lipid metabolism regulator. Cell Biochem Funct 27: 407–416, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosentino F, Luscher TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin and endothelial function. Eur Heart J 19, Suppl G: G3–G8, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Alto M, Ghio S, D'Andrea A, Pazzano AS, Argiento P, Camporotondo R, Allocca F, Scelsi L, Cuomo G, Caporali R. Inappropriate exercise-induced increase in pulmonary artery pressure in patients with systemic sclerosis. Heart 97: 112–117, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Oliveira NC, dos Santos Sabbag LM, Ueno LM, de Souza RB, Borges CL, de Sa Pinto AL, Lima FR. Reduced exercise capacity in systemic sclerosis patients without pulmonary involvement. Scand J Rheumatol 36: 458–461, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinenno FA, Jones PP, Seals DR, Tanaka H. Age-associated arterial wall thickening is related to elevations in sympathetic activity in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1205–H1210, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Bailey DM, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: effects of antioxidants and exercise training in elderly men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H671–H678, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooley A, Gao B, Bradley N, Abraham DJ, Black CM, Jacobs M, Bruckdorfer KR. Abnormal nitric oxide metabolism in systemic sclerosis: increased levels of nitrated proteins and asymmetric dimethylarginine. Rheumatology 45: 676–684, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frech T, Walker AE, Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Hopkins PN, Richardson RS, Wray DW, Donato AJ. Systemic sclerosis induces pronounced peripheral vascular dysfunction characterized by blunted peripheral vasoreactivity and endothelial dysfunction. Clin Rheumatol 34: 905–913, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frech TM, Revelo MP, Drakos SG, Murtaugh MA, Markewitz BA, Sawitzke AD, Li DY. Vascular leak is a central feature in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 39: 1385–1391, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garten RS, Groot HJ, Rossman MJ, Gifford JR, Richardson RS. The role of muscle mass in exercise-induced hyperemia. J Appl Physiol 116: 1204–1209, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodfield MJ, Hume A, Rowell NR. The effect of simple warming procedures on finger blood flow in systemic sclerosis. Br J Dermatol 118: 661–668, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulati M, Pandey DK, Arnsdorf MF, Lauderdale DS, Thisted RA, Wicklund RH, Al-Hani AJ, Black HR. Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women the St James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation 108: 1554–1559, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz SD, Yuen J, Bijou R, LeJemtel TH. Training improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in resistance vessels of patients with heart failure. J Appl Physiol 82: 1488–1492, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovacs G, Maier R, Aberer E, Brodmann M, Scheidl S, Trö ster N, Hesse C, Salmhofer W, Graninger W, Gruenig E. Borderline pulmonary arterial pressure is associated with decreased exercise capacity in scleroderma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 881–886, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwana M, Okazaki Y, Yasuoka H, Kawakami Y, Ikeda Y. Defective vasculogenesis in systemic sclerosis. Lancet 364: 603–610, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langille BL, O'Donnell F. Reductions in arterial diameter produced by chronic decreases in blood flow are endothelium-dependent. Science 231: 405–407, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 28: 1573–1576, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maki-Petaja KM, Day L, Cheriyan J, Hall FC, Ostor AJ, Shenker N, Wilkinson IB. Tetrahydrobiopterin supplementation improves endothelial function but does not alter aortic stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Heart Assoc 5: >2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meiszterics Z, Timar O, Gaszner B, Faludi R, Kehl D, Czirjak L, Szucs G, Komocsi A. Early morphologic and functional changes of atherosclerosis in systemic sclerosis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 43: 109–142, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 346: 793–801, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nietert PJ, Silverstein MD, Silver RM. Hospital admissions, length of stay, charges, and in-hospital death among patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 28: 2031–2037, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pu Q, Neves MF, Virdis A, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Endothelin antagonism on aldosterone-induced oxidative stress and vascular remodeling. Hypertension 42: 49–55, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowell LB. Human Cardiovascular Control. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, McInnes IB. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 108: 2957–2963, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu K, Ogawa F, Muroi E, Hara T, Komura K, Bae SJ, Sato S. Increased serum levels of nitrotyrosine, a marker for peroxynitrite production, in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 25: 281–286, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinozaki K, Nishio Y, Okamura T, Yoshida Y, Maegawa H, Kojima H, Masada M, Toda N, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A. Oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin prevents endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress in the aortas of insulin-resistant rats. Circ Res 87: 566–573, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thijssen DH, De Groot PC, van den Bogerd A, Veltmeijer M, Cable NT, Green DJ, Hopman MT. Time course of arterial remodelling in diameter and wall thickness above and below the lesion after a spinal cord injury. Eur J Appl Physiol 112: 4103–4109, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thijssen DH, Maiorana AJ, O'Driscoll G, Cable NT, Hopman MT, Green DJ. Impact of inactivity and exercise on the vasculature in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 108: 845–875, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thijssen DH, Willems L, van den Munckhof I, Scholten R, Hopman MT, Dawson EA, Atkinson G, Cable NT, Green DJ. Impact of wall thickness on conduit artery function in humans: is there a “Folkow” effect? Atherosclerosis 217: 415–419, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trinity JD, Wray DW, Witman MA, Layec G, Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Ives SJ, Conklin JD, Reese V, Richardson RS. Contribution of nitric oxide to brachial artery vasodilation during progressive handgrip exercise in the elderly. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R893–R899, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinity JD, Wray DW, Witman MA, Layec G, Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Ives SJ, Conklin JD, Reese V, Zhao J, Richardson RS. Ascorbic acid improves brachial artery vasodilation during progressive handgrip exercise in the elderly through a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H765–H774, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trinity JD, Wray DW, Witman MA, Layec G, Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Ives SJ, Conklin JD, Reese VR, Zhao J, Richardson RS. Ascorbic acid improves brachial artery vasodilation during progressive handgrip exercise in the elderly through a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H764–H774, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Duijnhoven NT, Green DJ, Felsenberg D, Belavy DL, Hopman MT, Thijssen DH. Impact of bed rest on conduit artery remodeling: effect of exercise countermeasures. Hypertension 56: 240–246, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wever RM, van Dam T, van Rijn HJ, de Groot F, Rabelink TJ. Tetrahydrobiopterin regulates superoxide and nitric oxide generation by recombinant endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237: 340–344, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wheeler CR, Salzman JA, Elsayed NM, Omaye ST, Korte DW Jr. Automated assays for superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase activity. Anal Biochem 184: 193–199, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wigley FM, Wise RA, Mikdashi J, Schaefer S, Spence RJ. The post-occlusive hyperemic response in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 33: 1620–1625, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams MH, Das C, Handler CE, Akram MR, Davar J, Denton CP, Smith CJ, Black CM, Coghlan JG. Systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary hypertension: improved survival in the current era. Heart 92: 926–932, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wray DW, Witman MA, Ives SJ, McDaniel J, Fjeldstad AS, Trinity JD, Conklin JD, Supiano MA, Richardson RS. Progressive handgrip exercise: evidence of nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation and blood flow regulation in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1101–H1107, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]