Abstract

Introduction

To characterize the contents of choline (Cho), creatine (Cr) and N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAA) in the hippocampus of healthy volunteers, we investigated the contents and their correlationship with age, gender and laterality.

Material and methods

Volunteers were grouped into a young, a middle and an old age. The Cho, Cr and NAA contents were determined with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS), and the correlationship was analyzed with Pearson correlation

Results

The concentration of NAA in the bilateral hippocampi was markedly lower in the old than in the young and the middle (LSD test, all p < 0.025). Furthermore, NAA/Cr in the bilateral hippocampi head (left: 1.10 ±0.40 vs. 1.54 ±0.49 or 1.43 ±0.49; right: 1.04 ±0.42 vs. 1.35 ±0.40 or 1.30 ±0.42), region 1 of the bilateral hippocampal body (left: 1.24 ±0.53 vs. 1.58 ±0.58 or 1.35 ±0.44; right: 1.30 ±0.43 vs. 1.54 ±0.51 or 1.35 ±0.51) and region 2 of the left hippocampal body (1.21 ±0.32 vs. 1.46 ±0.36 or 1.36 ±0.44) and the left hippocampal tail (1.11 ±0.40 vs. 1.36 ±0.47 or 1.15 ±0.32) was significantly higher in the old than in the young and the middle, respectively (all p < 0.026). The NAA content in the bilateral hippocampal head, body and tail negatively correlated with age. Moreover, the NAA, Cho and Cr contents in the hippocampal body and the tail were higher in the right than the left.

Conclusions

The NAA content of the hippocampal head, body and tail were significantly decreased in the old compared with younger persons, and it negatively correlates with age. The NAA, Cho and Cr contents exhibit laterality in the hippocampal body and tail.

Keywords: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, hippocampus, aging, N-acetylaspartylglutamate, choline

Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that aging is associated with a decline in cognitive function, with impaired attention span, memory deficit, poor executive function and judgment, while language ability is spared [1]. The hippocampus is intimately associated with cognitive function and is also important in memory and emotion [2, 3].

Changes in metabolites precede neuron loss and neural dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cause changes in the peaks of metabolites and the area under the peak in magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), which has better sensitivity than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in delineating changes in metabolites, allowing early detection of diseases [4, 5]. Aging is typically associated with a series of morphological changes in the brain such as cortical thinning and narrowing of the sulci [6], but the aging person exhibits no or mild changes in cognitive function. Several investigators have documented changes in the contents of metabolites such as N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAA) in the hypothalamus [7–9]. However, these studies typically involved very few subjects and have so far yielded conflicting results. Reyngoudt et al. [10] demonstrated that the NAA content of the hypothalamus did not change with age, while Chiu et al. [11] found that the NAA content of the left hippocampus positively correlated with age.

In the current investigation, we aimed to characterize the contents of certain metabolites including choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), and total NAA in the head, body and tail of the hippocampus in healthy volunteers by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) and study whether the contents of these metabolites and the ratio of NAA to Cho (NAA/Cho) and Cho to Cr (Cho/Cr) in the hippocampus correlated with age, gender and laterality.

Material and methods

Subjects

We recruited 121 healthy volunteers between October 2013 and December 2013, including 62 males and 59 females, aged between 20 and 89 years (mean age: 48.7 ±16.5 years) (Table I). The subjects were categorized into the young age group (20–39 years), the middle age group (40–59 years), and the old age group (60–89 years). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the authors’ affiliated institution. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) right handedness, (2) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score > 27, (3) no nervous system disease or mental illness such as headache, dizziness, lethargy, seizure, or emotional disturbance, (4) no previous cerebral surgery or trauma, no hypertension (> 140/90 mm Hg in those aged 60 years and above), diabetes, heart diseases or other chronic diseases, (5) no alcoholism, smoking, long-term medication, or drug addiction, (6) no contraindication for MRI, such as cardiac pacemaker, nerve stimulator, metal artery clip, or metal false tooth, (7) no history of seizure, convulsion, cerebritis or meningitis, (8) no history of cerebral hypoxia, carbon monoxide or other toxin poisoning, (9) no abnormality on conventional cerebral MRI, and no vacuolation or abnormal signal in the hippocampus, and (10) no severe artifacts or unsatisfactory imaging after data processing.

Table I.

Demographic data of study subjects

| Parameter | Young age | Middle age | Old age |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 41 | 40 | 40 |

| Age [years]: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.2 (4.6) | 49.3 (5.4) | 67.5 (4.9) |

| Range | 20–39 | 40–59 | 60–79 |

| Gender: | |||

| Male, n (%) | 22 (53.7) | 20 (50) | 20 (50) |

Cerebral MRI

All subjects received conventional cerebral T1WI/T2WI/FLAIR and the hippocampus received long axis T2WI and 2D-point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS)-144. Conventional MRI was performed with the Achieva 3.0T system (Philippe) using an 8-channel head coil and included axial T1WI, axial and sagittal T2WI, and axial T2FLAIR. The main parameters were as follows: axial T1WI: TSE sequence: TR, 3056 ms; TE, 7.6 ms; TI, 860 ms; axial T2WI: TSE sequence: TR, 2000 ms; TE, 80 ms; axial T2FLAIR: TR, 10002 ms; TE, 130.4 ms; TI, 2400 ms. For the above sequences, the slice thickness was 6.0 mm, slice interval 1.0 mm, matrix 512 × 256, FOV 240 × 240 × 120 mm (AP × RL × FH), and the number of signals averaged (NSA) 1. The parameters for sagittal T2WI were as follows: TSE sequence: TR, 2000 ms; TE, 80 ms; slice thickness, 6.0 mm; slice interval, 1.0 mm; matrix, 260 × 234, FOV, 240 × 240 × 143 mm (AP × RL × FH), and NSA, 1.

1H-MRS imaging

The patient was placed in the supine and lateral position and kept immobile. For sagittal T2W, a long axial scan was carried out by the long axis of the hippocampus with the following parameters: T2WI: TSE sequence: TR, 2000 ms; TE, 80 ms; slice interval, 0 mm; slice thickness, 3 mm. Multi-voxel 2D-PRESS-144 sequence was used. Axial images of the head, body, and tail of the hippocampus were obtained as described by Malykhin et al. [12], and a modified segmentation method was used to obtain the best visualization plane with the coronal oblique plane perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampus, and MRS of the left and right hippocampus was performed (Figure 1). Interfering tissues such as the skull, blood vessels, fat, dura matter and the cerebrospinal fluid were avoided. Scan parameters: TR 2000 ms, TE 144 ms, voxel size: 10 × 10 mm, slice thickness: 10 mm, matrix: 2 × 4, and FOV: 20 × 40 mm. The receiver/transmitter gain adjustment, voxel shimming, water suppression, water non-suppression and fat suppression image scans were completed automatically. The shimming effect reached a full width at half maximum < 15 Hz and a water suppression level of 99%. Total scan time was 15 min for the left and right hippocampus.

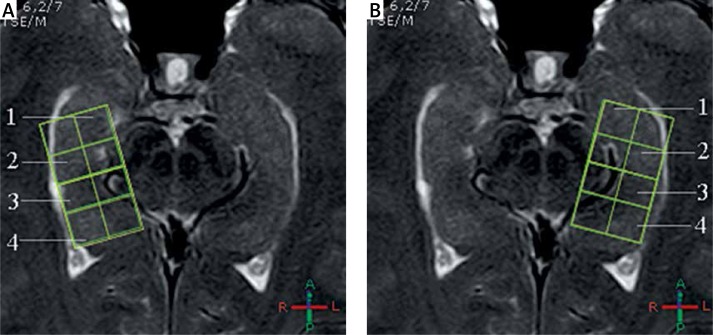

Figure 1.

Delineation of the hippocampus by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in the current study. A – Left hippocampus, B – right hippocampus

1 – hippocampal head, 2 – hippocampal body region 1, 3 – hippocampal body region 2, 4 – hippocampal tail.

Image processing

Raw MRS data were entered into the EWS workstation (Philippe) and analyzed using the unsuppressed water as an internal reference to calculate the concentrations of metabolites. The raw spectra underwent Gauss exponential multiplication, zero fill, Fourier transformation, frequency correction, phase correction, and baseline correction to obtain the corresponding MRS spectra (Figure 2). Single peak analysis was carried out, and the area under the peak for each metabolite was recorded, and the concentrations of Cho, Cr, and total NAA and NAA/Cho and Cho/Cr were calculated for analysis.

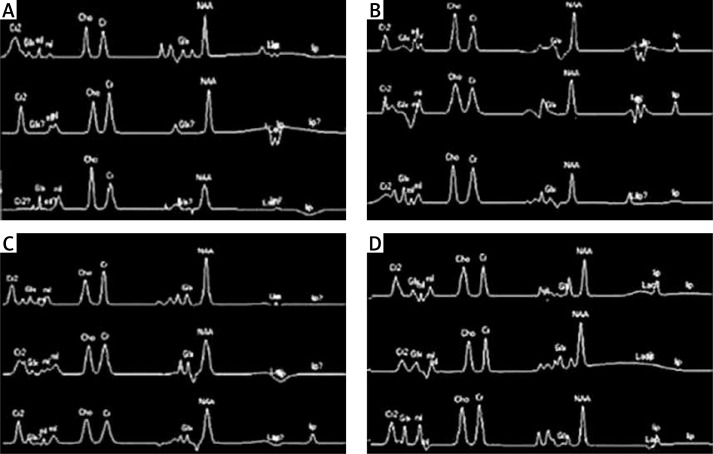

Figure 2.

Representative MRS spectra of the hippocampus: A – hippocampal head, B – hippocampal body region 1, C – hippocampal body region 2, D – hippocampal tail

Statistical analysis

All data were normally distributed and expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 13.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Parameters included NAA, Cho, Cr, and the ratio of NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr. To compare all metabolites in the hippocampal regions among the young age group, middle age group and the old age group, an ANOVA with planned comparisons was performed. The nature of this study is exploratory, and therefore in order to prevent inflation of type II errors and avoid important results going unreported, no correction for multiple testing was performed, as is accepted practice in such types of study. We used the least significant difference (LSD) t test to compare all metabolites in the hippocampal regions between two groups. A group t test was used to compare differences in metabolites in the same region of the hippocampus between male and female subjects, and a paired t test was used to compare differences in metabolites due to laterality of the hippocampal region, with post hoc testing. We performed Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relationship between metabolite concentrations and age. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Elderly subjects exhibit significant decline in NAA content in the bilateral hippocampi

We examined the function of the bilateral hippocampi by 1H-MRS imaging. The concentration of NAA in the bilateral hippocampal head, regions 1 and 2 of the hippocampal body and the hippocampal tail was markedly lower in the old age group than in the young age group and the middle age group (LSD test: p < 0.05 in all) (Table II). By contrast, no significant difference was noted in NAA content in these hippocampal regions between the young age group and the middle age group (LSD test: p > 0.05). Furthermore, the concentration of Cho and Cr in the bilateral hippocampal head, regions 1 and 2 of the hippocampal body and the hippocampal tail was comparable among the old age group, the young age group and the middle age group (LSD test: p > 0.05 in all) (Table II). We further examined the ratio of NAA to Cr of the bilateral hippocampi. We found that NAA/Cr in the bilateral hippocampi head, region 1 of the bilateral hippocampal body and region 2 of the left hippocampal body and the left hippocampal tail in the old age group was significantly higher than in the young and middle age group (p < 0.05 in all), while NAA/Cr in the bilateral hippocampi head, region 2 of the right hippocampal body, and the right hippocampal tail was comparable among the old age group, the young age group and the middle age group (p > 0.05 in all). Moreover, Cho/Cr was comparable in all the regions of the bilateral hippocampi examined among the old age group, the young age group and the middle age group (p > 0.05 in all).

Table II.

Comparison of function of the bilateral hippocampal regions

| Variables | Young | Middle aged | Old | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 24.40 ±6.42 | 24.44 ±9.41 | 16.23 ±7.44 | < 0.001 |

| Right | 23.24 ±6.56 | 21.94 ±7.30 | 15.63 ±6.85 | < 0.001 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 36.25 ±9.00 | 35.05 ±10.84 | 30.55 ±7.89 | 0.024 |

| Right | 38.90 ±10.52 | 38.36 ±7.67 | 33.68 ±9.54 | < 0.001 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 42.81 ±7.6 | 39.53 ±9.90 | 33.13 ±7.99 | < 0.001 |

| Right | 48.23 ±8.3 | 44.89 ±7.45 | 38.75 ±7.58 | < 0.001 |

| Hippocampal tail | ||||

| Left | 33.63 ±8.42 | 30.00 ±7.96 | 24.79 ±7.94 | < 0.001 |

| Right | 36.96 ±8.01 | 35.16 ±7.55 | 31.30 ±7.79 | 0.005 |

| Cho: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 18.55 ±7.89 | 22.05 ±8.20 | 20.24 ±8.26 | 0.214 |

| Right | 17.72 ±7.24 | 19.54 ±9.94 | 18.54 ±6.67 | 0.883 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 28.48 ±6.80 | 31.07 ±8.52 | 30.85 ±5.91 | 0.399 |

| Right | 30.85 ±9.86 | 31.4 ±10.04 | 32.4 ±10.42 | 0.397 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 30.92 ±6.71 | 31.2 ±10.91 | 30.87 ±7.28 | 0.808 |

| Right | 33.46 ±10.17 | 31.87 ±7.62 | 34.38 ±8.20 | 0.383 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 27.12 ±6.80 | 28.65 ±9.12 | 25.08 ±8.73 | 0.319 |

| Right | 29.69 ±10.53 | 28.68 ±8.97 | 29.74 ±6.81 | 0.834 |

| Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 16.93 ±6.17 | 17.86 ±7.64 | 16.38 ±5.93 | 0.604 |

| Right | 17.60 ±6.60 | 18.30 ±7.85 | 14.95 ±4.94 | 0.194 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 24.79 ±8.06 | 26.43 ±8.63 | 27.14 ±7.97 | 0.419 |

| Right | 26.97 ±8.57 | 29.89 ±9.63 | 27.39 ±7.91 | 0.551 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 30.68 ±7.08 | 30.84 ±8.56 | 28.35 ±7.30 | 0.283 |

| Right | 33.26 ±8.37 | 32.22 ±9.35 | 31.39 ±5.03 | 0.641 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 26.03 ±9.50 | 26.88 ±6.78 | 24.02 ±7.40 | 0.224 |

| Right | 30.03 ±9.73 | 30.8 ±10.10 | 26.63 ±5.93 | 0.240 |

| NAA/Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 1.54 ±0.492 | 1.43 ±0.494 | 1.10 ±0.404 | < 0.001 |

| Right | 1.35 ±0.396 | 1.30 ±0.423 | 1.04 ±0.417 | 0.002 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 1.58 ±0.576 | 1.35 ±0.441 | 1.24 ±0.526 | 0.021 |

| Right | 1.54 ±0.514 | 1.35 ±0.507 | 1.30 ±0.426 | 0.023 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 1.46 ±0.395 | 1.36 ±0.438 | 1.21 ±0.323 | 0.025 |

| Right | 1.42 ±0.412 | 1.47 ±0.592 | 1.33 ±0.320 | 0.058 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 1.36 ±0.469 | 1.15 ±0.320 | 1.11 ±0.400 | 0.017 |

| Right | 1.40 ±0.596 | 1.19 ±0.518 | 1.21 ±0.317 | 0.181 |

| Cho/Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 1.12 ±0.478 | 1.35 ±0.510 | 1.23 ±0.493 | 0.148 |

| Right | 1.10 ±0.421 | 1.10 ±0.460 | 1.20 ±0.329 | 0.490 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 1.26 ±0.523 | 1.32 ±0.611 | 1.28 ±0.476 | 0.799 |

| Right | 1.21 ±0.408 | 1.12 ±0.387 | 1.24 ±0.402 | 0.331 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 1.04 ±0.275 | 1.06 ±0.420 | 1.12 ±0.404 | 0.421 |

| Right | 1.04 ±0.445 | 1.05 ±0.355 | 1.19 ±0.361 | 0.151 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 1.11 ±0.403 | 1.12 ±0.349 | 1.01 ±0.407 | 0.410 |

| Right | 1.05 ±0.473 | 1.04 ±0.458 | 1.14 ±0.276 | 0.491 |

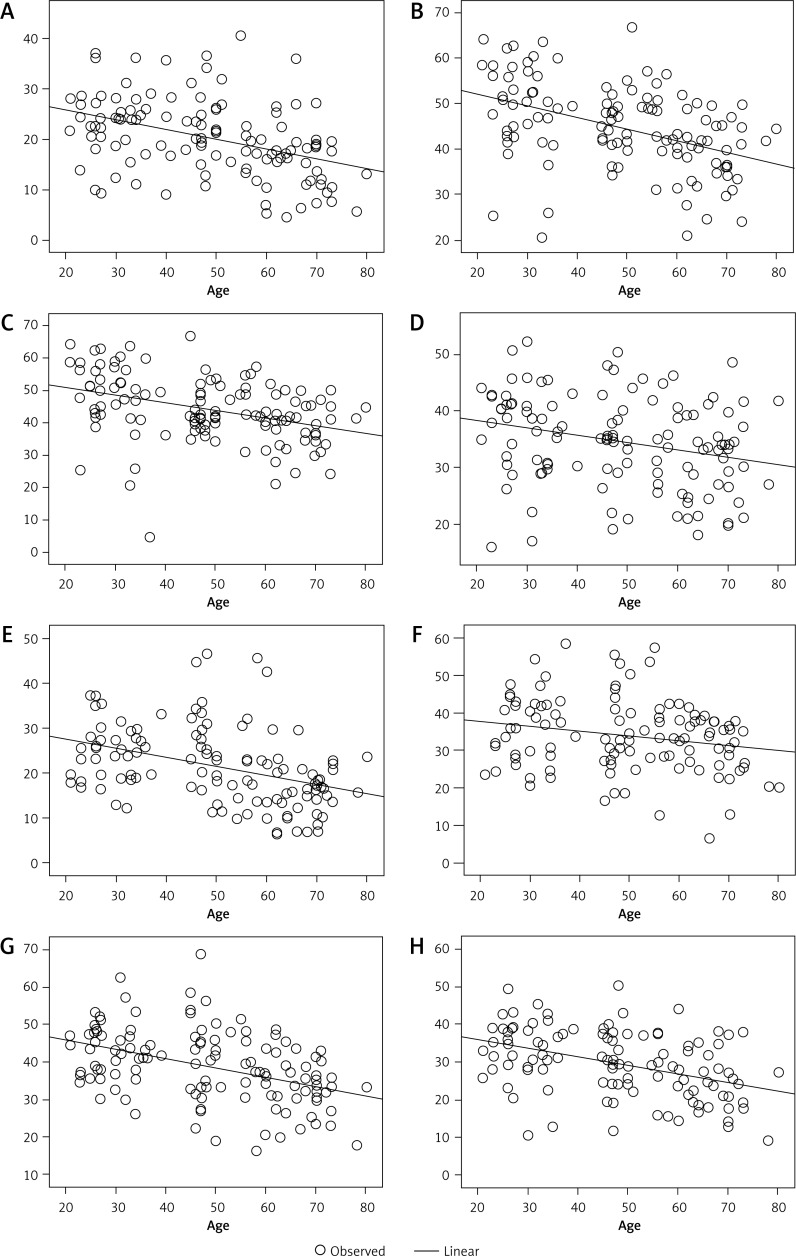

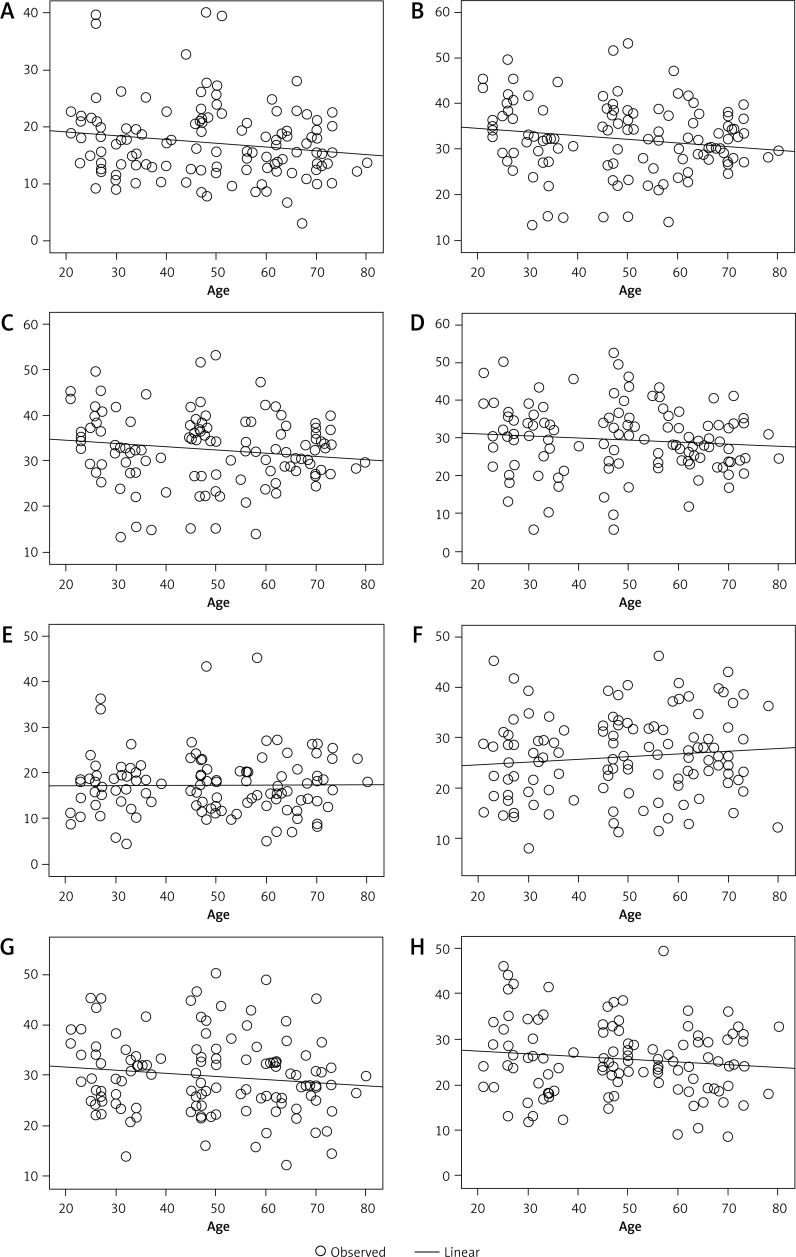

NAA content in the hippocampus negatively correlates with age

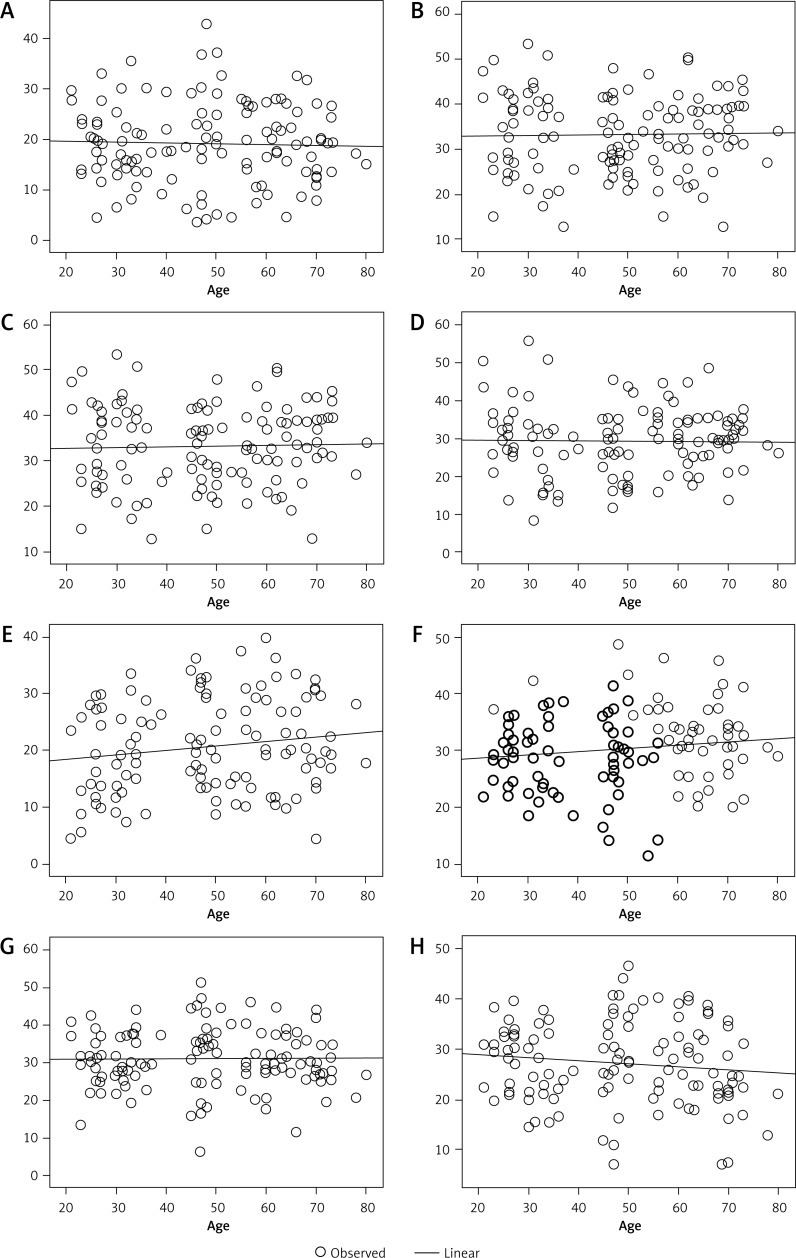

Pearson correlation analysis showed that the NAA content in the bilateral hippocampal head, body (regions 1 and 2), and tail negatively correlated with age (Figure 3). By contrast, the Cho and Cr content in the bilateral hippocampal head, body (regions 1 and 2), and tail showed no correlation with age (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

NAA level negatively correlates with age in the right hippocampal head (A), regions 1 (B) and 2 (C) of the right hippocampal body, the right hippocampal tail (D), the left hippocampal head (E) and regions 1 (F) and 2 (G) of the left hippocampal body, and the hippocampal tail (H)

Figure 4.

Cho level does not correlate with age in the right hippocampal head (A), regions 1 (B) and 2 (C) of the right hippocampal body, the right hippocampal tail (D), the left hippocampal head (E) and regions 1 (F) and 2 (G) of the left hippocampal body, and the hippocampal tail (H)

Figure 5.

Cr level does not correlate with age in the right hippocampal head (A), regions 1 (B) and 2 (C) of the right hippocampal body, the right hippocampal tail (D), the left hippocampal head (E) and regions 1 (F) and 2 (G) of the left hippocampal body, and the hippocampal tail (H)

NAA, Cho and Cr contents exhibit laterality in the hippocampal body and tail

We further examined whether the NAA, Cho and Cr contents in the bilateral hippocampi exhibited laterality. The paired t test showed no statistically significant difference in the contents of NAA, Cho, and Cr, and NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr in the left and right hippocampal head (p > 0.05 in all) (Table III). On the other hand, the NAA, Cho and Cr contents in regions 1 and 2 of the hippocampal body and the hippocampal tail were significantly higher in the right hippocampal body than the left hippocampal body (p < 0.05 in all) even though no laterality was demonstrated in NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr in the hippocampal body and tail (p > 0.05).

Table III.

Comparison of function of the bilateral hippocampi according to laterality

| Variable | Left | Right | t | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head: | ||||

| NAA | 21.73 ±8.61 | 20.24 ±7.63 | –1.619 | 0.108 |

| Cho | 20.64 ±8.21 | 18.90 ±7.94 | –1.759 | 0.081 |

| Cr | 17.05 ±6.58 | 17.02 ±6.35 | –0.042 | 0.967 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.31 ±0.46 | 1.24 ±0.43 | –1.358 | 0.177 |

| Cho/Cr | 1.26 ±0.51 | 1.14 ±0.43 | –1.942 | 0.055 |

| Body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| NAA | 34.23 ±9.42 | 37.00 ±9.72 | 2.384 | 0.019 |

| Cho | 26.11 ±8.21 | 31.28 ±9.47 | 4.408 | < 0.001 |

| Cr | 26.11 ±8.21 | 28.02 ±8.77 | 2.436 | 0.016 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.45 ±0.62 | 1.40 ±0.46 | –1.924 | 0.486 |

| Cho/Cr | 1.29 ±0.52 | 1.17 ±0.36 | –0.699 | 0.057 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| NAA | 38.56 ±9.47 | 43.71 ±10.17 | 4.593 | < 0.001 |

| Cho | 30.98 ±8.45 | 33.16 ±8.70 | 2.173 | 0.032 |

| Cr | 29.87 ±7.72 | 32.36 ±7.86 | 2.658 | 0.009 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.35 ±0.40 | 1.40 ±0.44 | 0.915 | 0.362 |

| Cho/Cr | 1.08 ±0.37 | 1.10 ±0.40 | 0.284 | 0.777 |

| Tail: | ||||

| NAA | 29.46 ±8.72 | 34.48 ±8.12 | 5.648 | < 0.001 |

| Cho | 26.94 ±8.32 | 29.45 ±8.85 | 2.343 | 0.021 |

| Cr | 25.73 ±7.80 | 29.16 ±8.95 | 3.466 | 0.001 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.18 ±0.37 | 1.28 ±0.50 | 1.964 | 0.052 |

| Cho/Cr | 1.08 ±0.39 | 1.08 ±0.41 | 0.002 | 0.999 |

NAA, Cho and Cr contents in the hippocampus do not correlate with gender

We additionally investigated whether the NAA, Cho and Cr contents of the bilateral hippocampi correlated with gender of the study subjects. The paired t test revealed that the NAA, Cho and Cr contents of the bilateral hippocampi showed no statistically significant difference in the study participants of different genders (Table IV) (p > 0.05).

Table IV.

Comparison of function of the bilateral hippocampi according to gender

| Variables | Male | Female | t | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 21.16 ±8.23 | 22.33 ±9.02 | –0.743 | 0.459 |

| Right | 19.21 ±6.08 | 21.44 ±6.98 | 1.620 | 0.108 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 33.65 ±8.18 | 34.82 ±8.62 | –0.628 | 0.497 |

| Right | 35.69 ±9.89 | 38.37 ±9.34 | 1.533 | 0.128 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 39.28 ±8.93 | 37.79 ±9.95 | 0.857 | 0.393 |

| Right | 43.15 ±8.54 | 44.91 ±8.43 | 0.962 | 0.338 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 29.07 ±8.61 | 29.78 ±8.85 | –0.448 | 0.655 |

| Right | 33.59 ±7.44 | 35.46 ±8.68 | 1.271 | 0.206 |

| Cho: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 20.27 ±7.63 | 21.03 ±8.82 | –0.509 | 0.611 |

| Right | 18.97 ±7.44 | 19.07 ±8.63 | 0.067 | 0.947 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 30.17 ±6.98 | 30.53 ±6.92 | –0.291 | 0.772 |

| Right | 30.79 ±9.58 | 31.64 ±9.31 | 0.500 | 0.618 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 31.70 ±8.47 | 30.25 ±8.36 | 0.937 | 0.351 |

| Right | 32.12 ±9.20 | 34.42 ±7.44 | 1.461 | 0.147 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 26.79 ±8.41 | 27.09 ±8.29 | –0.195 | 0.845 |

| Right | 29.38 ±9.44 | 29.37 ±8.28 | –0.006 | 0.996 |

| Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 16.29 ±5.36 | 17.84 ±7.62 | –1.299 | 0.196 |

| Right | 17.22 ±7.83 | 17.18 ±5.18 | –0.034 | 0.973 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 25.50 ±7.56 | 26.74 ±8.85 | –0.826 | 0.410 |

| Right | 26.58 ±8.67 | 29.64 ±8.64 | 1.942 | 0.054 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 29.63 ±7.65 | 30.22 ±7.82 | –0.414 | 0.680 |

| Right | 32.18 ±8.18 | 32.42 ±7.44 | 0.167 | 0.867 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 24.95 ±8.24 | 26.55 ±7.28 | –1.123 | 0.264 |

| Right | 28.70 ±9.00 | 29.69 ±8.87 | 0.612 | 0.541 |

| NAA/Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 1.33 ±0.50 | 1.28 ±0.42 | 0.593 | 0.555 |

| Right | 1.16 ±0.45 | 1.31 ±0.40 | 1.913 | 0.058 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 1.46 ±0.69 | 1.44 ±0.54 | 0.227 | 0.821 |

| Right | 1.41 ±0.48 | 1.39 ±0.43 | –0.216 | 0.830 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 1.38 ±0.38 | 1.32 ±0.41 | 0.856 | 0.393 |

| Right | 1.35 ±0.44 | 1.47 ±0.43 | 1.452 | 0.149 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 1.20 ±0.37 | 1.16 ±0.36 | 0.560 | 0.576 |

| Right | 1.29 ±0.53 | 1.28 ±0.45 | –0.092 | 0.927 |

| Cho/Cr: | ||||

| Hippocampal head: | ||||

| Left | 1.27 ±0.50 | 1.26 ±0.53 | 0.184 | 0.854 |

| Right | 1.14 ±0.44 | 1.13 ±0.41 | –0.208 | 0.836 |

| Hippocampal body: | ||||

| Region 1: | ||||

| Left | 1.29 ±0.54 | 1.26 ±0.51 | 0.329 | 0.743 |

| Right | 1.21 ±0.38 | 1.13 ±0.34 | –1.232 | 0.220 |

| Region 2: | ||||

| Left | 1.09 ±0.32 | 1.07 ±0.42 | 0.261 | 0.794 |

| Right | 1.05 ±0.39 | 1.15 ±0.40 | 1.422 | 0.158 |

| Hippocampal tail: | ||||

| Left | 1.13 ±0.40 | 1.03 ±0.36 | 1.425 | 0.157 |

| Right | 1.09 ±0.41 | 1.06 ±0.41 | –0.458 | 0.648 |

Discussion

The hippocampus plays a critical role in cognitive function and memory [13], and impairment of the hippocampus leads to cognitive function decline and memory deficits, especially in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. 1H-MRS is a sensitive method in detecting early signs of functional changes of the brain by measuring changes in certain metabolites. Here, we demonstrated that elderly subjects exhibited significant decline in the NAA content in the bilateral hippocampi compared with younger persons. We further found that the NAA content in the head, body and tail of the bilateral hippocampi negatively correlated with age, showing a significant decline with increased age, which is consistent with the findings of others [7–9].

Previous studies have shown that memory is intimately associated with the plasticity of neuronal synapses in the hippocampus and decline in cognitive function directly correlates with loss of synapses [14, 15], which has been well documented in the aging hippocampus. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques are present in the aging hippocampus [6, 13]. Neurofibrillary tangles are most noticeable in the frontal lobe and the hippocampal body, especially the CAI region. In patients with AD, neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques are more apparent in the hippocampus. Senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles cause destruction of synapses, leading to a decline in cognitive function. NAA is mainly present in neurons, and its content correlates with neuron maturation and number. Though aging has been found to be associated with neuron loss, it remains inconclusive whether aging leads to a decline in NAA contents on MRS. Reyngoudt et al. [10] found that the NAA content did not change with age, while Chiu et al. [11] showed that the NAA content of the left hippocampus positively correlated with age. The current study, on the other hand, demonstrated a significant decline in the NAA content in the bilateral hippocampi of elderly subjects compared with younger persons. Our study enrolled a much larger number of subjects than the studies by Reyngoudt et al. and Chiu et al. and therefore should carry more weight. The significant decline in the NAA content of the bilateral hippocampal head, body and tail in elderly subjects suggests a marked reduction in the number of neurons or synapses in the hippocampus of these aging persons.

Cho is present in neurons and glial cells. Cho content can reflect membrane stability and glial proliferation. We found that the Cho content of the hippocampus did not change with age, which is consistent with those findings reported by other investigators [10, 16, 17], indicating that there is no apparent proliferation or degradation of glial cells in the hippocampus as a person ages. Cr is mainly present in glial cells and reflects the sum of creatine and phosphocreatine in the brain. Previous studies have shown that Cr levels remain steady under different metabolic conditions of the brain. We also found that the Cr content in the bilateral hippocampus did not change with age, suggesting that there was no significant glial cell proliferation during aging. However, some recent studies indicate [18, 19] that the Cr content in the cortex of the frontal lobe and parietal lobe increases with age; therefore, one should be cautious when using Cr as an internal reference for NMR study. Furthermore, we found that NAA/Cr of the bilateral hippocampal head was significantly lower in the old age group than the young and middle age group. A statistically significant difference was also observed in NAA/Cr in the bilateral hippocampal body (region 1), left hippocampal body (region 2), and left hippocampus tail between the old age group and young age group, which is partially consistent with MRS studies on the whole hippocampus by other investigators [20, 21].

Brain asymmetry exists both anatomically and functionally [22–24]. Few studies have addressed the issue whether the left hippocampus is dominant over the right hippocampus or vice versa. Klur et al. [25] demonstrated that the left hippocampus is dominant in coding and information transmission while the right hippocampus is dominant in memory compensation. Kessels et al. [26] reported that patients who received frontal or temporal lobectomy and sustained injury to the right hippocampus exhibited poorer spatial memory compared with those who sustained injury to the left hippocampus. Recently, several investigators [27–32] have reported that seizure patients who received temporal lobectomy exhibited lateralization of function of the hippocampus such as spatial memory. However, it remains unknown whether laterality of the hippocampal function is associated with changes in metabolite contents. In the current study, we demonstrated lateralization in NAA, Cho and Cr contents in the hippocampal body and tail while no difference was noted in NAA/Cr and Cho/Cr. The higher NAA content in the right hippocampal body and tail suggests a higher number of neurons or synapses in the right hippocampal body and tail than their left counterparts, which may contribute to lateralization of function of the hippocampus. Our findings also suggest that when we evaluate the metabolite contents of the hippocampus, we should take laterality into consideration.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates by MRS a significant decline in the NAA content of the hippocampal head, body and tail of elderly subjects compared with younger persons, and the NAA content of the hippocampus negatively correlates with age. Furthermore, the NAA, Cho and Cr contents exhibit laterality in the hippocampal body and tail. Our findings provide insight into changes in certain metabolites in the hippocampus during aging, and future studies should be carried out to further delineate changes in metabolites during aging and development of neurodegenerative diseases in order to provide useful data for making informed therapeutic decisions for patients with neurodegenerative diseases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Qiang J, Geng Y, Wang M. Normal brain aging nerve pathological changes and cognitive decline. J Int Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;39:464–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrak RE, Griffin ST, Graham DI. Aging-associated changes in human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1269–75. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199712000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peelle JE, Cusack R, Henson RN. Adjusting for global effects in voxel-based morphometry: gray matter decline in normal aging. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1503–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Q, Wang Y, You M, Liao G, Pu J, Cheng H. Diagnosis value of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the primary epilepsy patients with hippocampal lesions. J Clin Neurol. 2012;25:325–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y, Liu W, Mei G, Ma Q, Li H, Chen N. Study of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in hippocampus of senile depressive patients. J Clin Psych. 2009;19:227–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Li D. Research and development of the aging brain. Nature Magazine. 1996;l8:286–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sailasuta N, Ernst T, Chang L. Regional variations and the effects of age and gender on glutamate concentrations in the human brain. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:667–775. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang L, Jiang CS, Ernst T. Effects of age and sex on brain glutamate and other metabolites. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:142–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raininko R, Mattson P. Metabolite concentrations in supraventricular white matter from teenage to early old age: a short echo time 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) study. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:309–15. doi: 10.3109/02841850903476564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyngoudt H, Claeys T, Vlerick L, et al. Age-related differences in metabolites in the posterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus of normal ageing brain: a 1H-MRS study. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu PW, Mak HK, Yau KK, Chan Q, Chang RC, Chu LW. Metabolic changes in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortices of the normal aging brain: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 3 T. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:251–64. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malykhin NV, Bouchard TP, Ogilvie CJ, Coupland NJ, Seres P, Camicioli R. Three-dimensional volumetric analysis and reconstruction of amygdala and hippocampal head, body and tail. Psychiatry Res. 2007;155:155–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sexton CE, Mackay CE, Lonie JA, et al. MRI correlate sofepisodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging. Psychiatry Res. 2010;184:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong TP, Marchese G, Casu MA, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Cuello AC, De Koninck Y. Loss of presynaptic and postsynaptic structures is accompanied by compensatory increase in action potential dependent synaptic input to layer V neocortical pyramidal neurons in aged rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8596–606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08596.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman P, Federoff H, Kurlan R. A focus on the synapse for neuroprotection in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2004;63:1155–62. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140626.48118.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlton RA, McIntyre DJ, Howe FA, Morris RG, Markus HS. The relationship between white matter brain metabolites and cognition in normal aging: the GENIE study. Brain Res. 2007;1164:108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders DE, Howe FA, van den Boogaart A, Griffiths JR, Brown MM. Aging of the adult human brain: in vivo quantitation of metabolite content with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:711–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199905)9:5<711::aid-jmri14>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruber S, Pinker K, Riederer F, et al. Metabolic changes in the normal ageing brain: consistent findings from short and long echo time proton spectroscopy. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raininko R, Mattsson P. Metabolite concentrations in supraventricular white matter from teenage to early old age: a short echo time 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) study. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:309–15. doi: 10.3109/02841850903476564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma X, Wang G, Wang Y, Cheng K. Clinical research on the changes of different age hippocampus-1H-MRS of normal people. Mod J Integ Trad Chin West Med. 2010;19:1965–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang H, Gu J, Yang C. Normal hippocampus proton magnetic resonance spectrum. Sichuan Med. 2008;29:774–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bethmann A, Tempelmann C, De Bleser R, Scheich H, Brechmann A. Determining language laterality by fMRI and dichotic listening. Brain Res. 2007;1133:145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ocklenburg S, Güntürkün O, Beste C. Lateralized neural mechanisms underlying the modulationg of response inhibition processes. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1771–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogel JJ, Bowers CA, Vogel DS. Cerebral lateralization of spatial abilities: a meta-analysis. Brain Cogn. 2003;52:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klur S, Muller C, Pereira de Vasconcelos A, et al. Hippocampal-dependent spatial memory functions might be lateralized in rats: an approach combining gene expression profiling and reversible inactivation. Hippocampus. 2009;19:800–16. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessels RP, de Haan EH, Kappelle LJ, Postma A. Varieties of human spatial memory: a meta-analysis on the effects of hippocampal lesions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vannest J, Szaflarski JP, Privitera MD, Schefft BK, Holland SK. Medial temporal fMRI activation reflects memory lateralization and memory performance in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner DD, Sziklas V, Garver KE, Jones-Gotman M. Material-specific lateralization of working memory in the medial temporal lobe. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner K, Frings L, Spreer J, et al. Differential effect of side of temporal lobe epilepsy on lateralization of hippocampal, temporolateral, and inferior frontal activation patterns during a verbal episodic memory task. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:382–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perek B, Malińska A, Nowicki M, Misterski M, Ostalska-Nowicka D, Jemielity M. Histological evaluation of age-related variations in saphenous vein grafts used for coronary artery bypass grafting. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:1041–7. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.32412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panahi N, Mahmoudian M, Mortazavi P, Hashjin GS. Effects of berberine on beta-secretase activity in a rabbit model of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:146–50. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.33354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun C, Zhang H, Xu J, Gao J, Qi X, Li Z. Improved methodology to obtain large quantities of correctly folded recombinant N-terminal extracellular domain of the human muscle acetylcholine receptor for inducing experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in rats. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:389–95. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.36921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]