Abstract

Small-molecule CD4 mimics (SMCM’s) bind to the gp120 subunit of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) and have been optimized to block cell infection in vitro. The lack of the V1/2 and V3 loops and the presence of the β2/3 and β20/21 strands (bridging sheet) in the available structures of the monomeric gp120 core may limit its applicability as a target for further synthetic optimization of SMCM potency and/or breadth. Here, we employ a combination of binding-site search, docking, estimation of protein–ligand interaction energy, all-atom molecular dynamics, and ELISA-based CD4-binding competition assays to create, characterize, and rationalize models of first- and second-generation of SMCM’s bound to the distinct, trimeric BG505 SOSIP.664 structures 4NCO and 4TVP containing V1/2 and V3 loops with no bridging sheet. We demonstrate that the in silico neutralization of the highly conserved D368 is necessary to obtain the correct orientation of SMCM in their binding site when docking against the monomeric gp120 core. The computational results correlate with IC50’s measured in CD4 binding competition ELISA and with KD’s measured on gp120 core monomer. This supports the hypothesis that the 4NCO trimeric structure represents a viable target for further SMCM’s optimization with advantages over both the 4TVP trimer and gp120 core monomer. Finally, the docking protocol has been optimized to screen compounds that can clearly interact with the highly conserved residue D368, increasing the likelihood of future optimizations to arrive at SMCM’s with a broader spectrum of activity.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

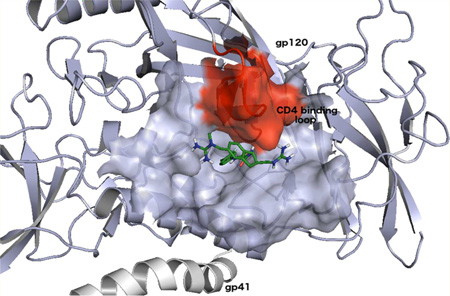

AIDS, caused by the type-1 Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1), remains a serious health concern worldwide. Virus entry into a target cell is mediated by the viral envelope glycoprotein spike (Env), which is a trimer of gp120/gp41 heterodimers. The entry mechanism begins with binding of cellular CD4 to gp120, which conformationally decrypts a binding site on gp120, at least partially made up by the so-called bridging sheet, that engages a coreceptor (CCR5 or CXCR4). Co-receptor binding triggers a further conformational cascade that separates gp120 from gp41, permitting gp41 to insert the N-terminal fusion peptide into the target cell membrane, followed by a refolding event that brings the viral and cell membranes into close proximity to promote fusion.1 Molecules designed to interfere with any one of these steps are collectively referred to as entry inhibitors.

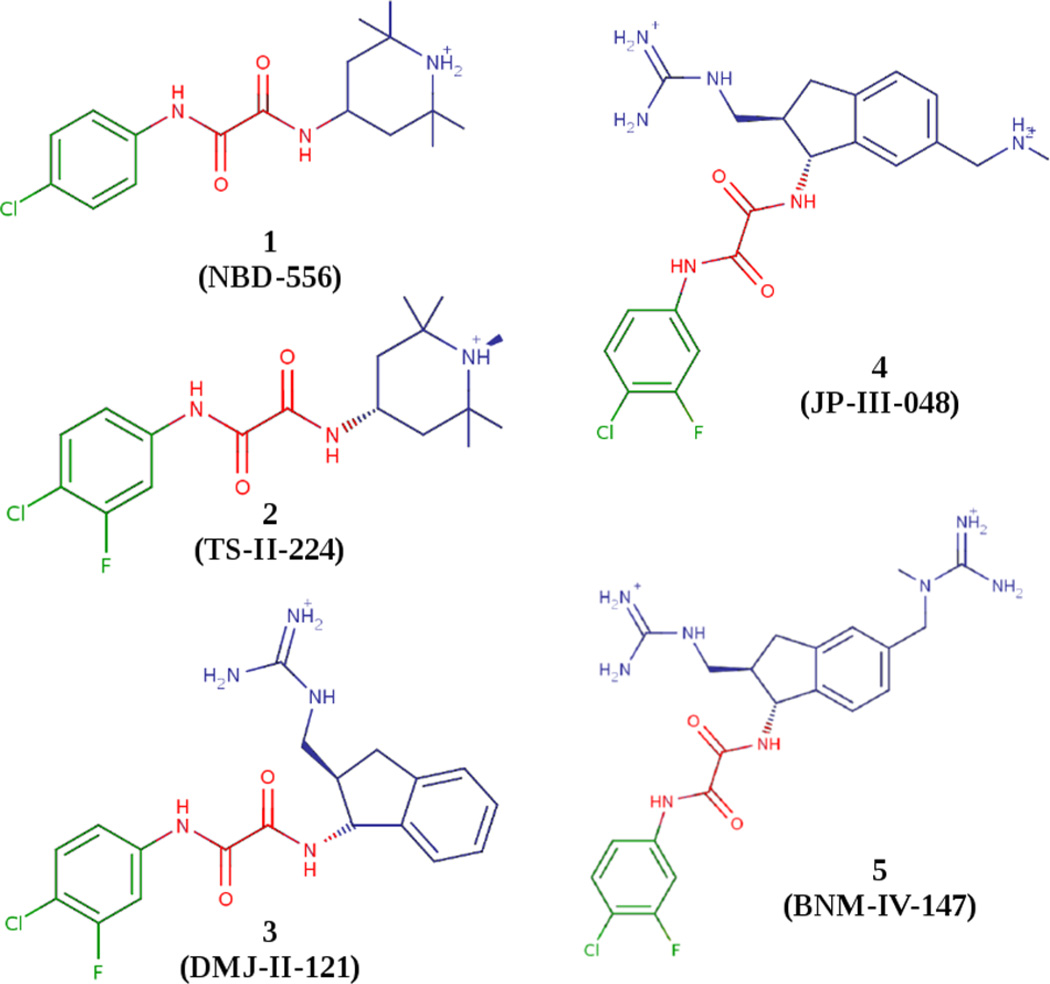

Small-molecule CD4 mimics (SMCM’s) comprise one promising class of entry inhibitors currently in preclinical development.2–5 Originally based on the CD4-competitive gp120-binding agents NBD-556 and -557,6 SMCM’s are characterized by three regions: region I, a halogenated phenyl ring; region II, an oxalamide linker; and region III, an aliphatic/aromatic ring system variously decorated with functional groups intended to interact with gp120 surface residues.7,8 The five representative SMCM’s considered here are the parent compound 1 (NBD-556), the second-generation compound 2 (TS-II-224), and the third-generation authentic viral entry antagonist compounds 3, 4, and 5 (DMJ-II-121, JP-III-048, and BNM-IV-147, respectively) all shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of SMCM’s 1–5 with region I shown in green, region II in red, and region III in blue.7

Based on several X-ray crystal structures using monomeric core gp120,9–12 it is known that region I inserts deeply into the so-called Phe43 cavity (which is observed to be partially occupied by Phe43 of CD4 in gp120-CD4 complexes),13 while region III makes a variety of contacts with surface residues surrounding the cavity opening, or vestibule. Importantly, there has never been an X-ray structure of an SMCM-bound gp120 that shows a direct interaction between any SMCM and the highly conserved residue D368, known to be crucially important for CD4 binding, and a major target for SMCM optimization.11,12 Unfortunately, recent computational work on 3-, 4- and 5-gp120 complexes predicted an H-bond at D368 engaged by the region III guanidinium moiety of these compounds.11,12 The disagreement between docking predictions and X-ray structures regarding interaction with D368 indicate that it is important to investigate and eliminate the root of this particular false positive if one wishes to continue using the core monomeric gp120 as a target.

These crystal structures also reveal that SMCM’s are able to bind to a gp120 conformation that in all major ways is identical to that induced by CD4 binding, with a fully formed Phe43 cavity and an intact bridging sheet. This is consistent with the observation that early SMCM’s, including the parent NBD compounds, enhanced viral entry into CD4-deficient T-cells in vitro. This fact importantly drove previous efforts to optimize SMCM’s region III, which has now led to a class of potent antagonists of viral entry.11,12 However, one potentially important barrier to the continued development of SMCM’s is the lack of structural understanding of how they interact with full-length gp120 when it is not in the CD4-bound conformation, as represented in the 4NCO and 4TVP crystal structures.14,15 Currently no crystal structures of such complexes are available.

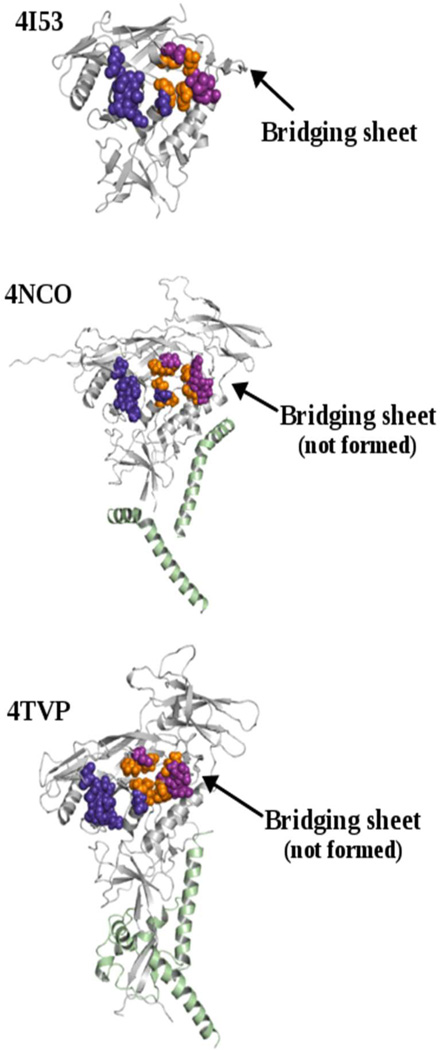

The purpose of this work is to evaluate the suitability of the existing structures of the soluble trimeric BG505 SOSIP.664 protein as targets for SMCM optimization beyond core monomeric gp120, all shown in Figure 2.14,15

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of core monomeric gp120 from PDB 4I53,11 full-length gp140 extracted from PDB 4NCO,14 and full-length gp140 extracted from PDB 4TVP.15 CD4-binding hotspot residues (VDW representation) highlight the CD4 binding site in each representation.16–18 Orange VDW represents high affinity and high allosteric effect hot-spot residues; purple VDW, high affinity and moderate allosteric effect hot-spot residues; deep purple VDW, only affinity hot-spot residues. In 4NCO and 4TVP the gp41 subunit is represented in a light green cartoon image.

Using a binding site search with an automated docking protocol calibrated against the X-ray structure of monomeric core gp120 in complex with a particular SMCM, we discovered favorable encounter complex structures of the three SMCM’s bound to the BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140 with PDB codes 4NCO and 4TVP.14,15 We found that the series of predicted protein–ligand interaction energies (PLIE’s) computed by means of SZYBKI on the 4NCO target, but not the 4TVP target, correlated well to the compounds’ KD values in binding thermodynamics studies on core monomeric gp120 done previously as well as to IC50’s in direct CD4-binding competition assays against authentic SOSIP protein performed in this study. In addition, we found that PLIE’s computed by means of the MM-GBSA method showed correlation with experimental KD’s and direct CD4 competition IC50’s on the 4NCO target. Using MD simulations initialized from our docked models, we present detailed interaction maps between the SMCM’s and the targets. This study thus lays important groundwork to further the development of SMCM’s on full-length, CD4-naïve targets and argues in particular for the viability of the 4NCO SOSIP target.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Target Preparation

All target structures were taken from the PDB, and pretreated using the Protein Preparation Wizard application of the Maestro 9.9 suite (Schrödinger),19 adding H atoms, filling in missing side chains and loops using Prime,20 assigning cocrystallized ligand ionization state at physiological pH (7 ± 2) using Epik,21–23 and checking amino acids protonation state using PROPKA at physiological pH (7 ± 2). Trimeric gp140 protein atoms were taken from the BG505 SOSIP.664 structures 4NCO and 4TVP.14,15 Unresolved side-chains in the gp120 protomer of each SOSIP structure were modeled. For the docking gp120 core monomer, protein atoms were taken from the cocrystal structure of 3 (PDB ID: 4I53).11 Three cases for each target were considered: (i) the wild-type (WT) protein; (ii) the protein with a protonated D368 (variant-2), and (iii) the D368N mutant (variant-3). These latter two variants were generated to assess the role of the negative charge at D368 on the docking pose predictions.

Docking and Rescoring Protocol

Docking calculations were performed using the Standard Precision (SP) scoring function of Glide 6.5 (Schrödinger).24–28 Glide performed a search of conformational, orientational, and positional spaces of the docked ligand, followed by torsionally flexible energy optimization using an OPLS-AA nonbonded potential for a few hundred surviving candidate poses. By default, the five best-scoring candidates were further refined via a Monte Carlo sampling of pose conformation. The selection of the best-docked pose used an energy function that combines empirical and force-field-based terms.28 Here, we chose the first 50 poses per ligand to undergo postdocking energy minimization, keeping the best 10 poses showing threshold energy lower than 0.50 kcal mol−1. All docking calculations were performed restraining the O═C─C═O torsional angle on the SMCM’s oxalamide moiety, in order to keep the carbonyl groups in dipole-minimizing trans conformation. Docking validation was performed on gp120 4I53 coordinates, via successful recapitulation of the cocrystal binding poses of all five SMCM’s on core monomeric gp120. The protein–ligand interaction energy (PLIE) was then computed through SZYBKI 1.8.0.1 (Openeye Scientific Software)29 according to the Poisson–Boltzmann solvation model, for all 10 saved docking poses for each compound, for a total of 150 PLIE calculations.

Preliminary Binding Site Search on SOSIP Targets

In WT 4NCO and 4TVP, a preliminary binding site search was performed on the overall protein surface. For each target, two grids were generated: (i) a front-side grid with an inner box of 30 Å × 30 Å × 30 Å and an outer box of 50 Å × 50 Å × 50 Å, centered on residue D368, encompassing all the surface atoms in the CD4-binding region; and (ii) a back-side grid with the same size as the front-side grid, encompassing all of the protein surface on the opposite side of the CD4 binding region. The PLIE was then computed on the top 10 saved docking poses (for a total of 200 PLIE calculations over five ligands, two binding sites, 10 poses per ligand per site), in order to check the formation of eventual favorable complexes outside the CD4 binding region.

Focused Docking

For the core monomeric gp120 target from 4I53, the center of the docking grid was set on the cocrystallized compound 3 with the default grid size. In 4NCO, the docking grid was defined based on the known SMCM binding site in monomeric core gp120 centering it on D368, with default grid size; in 4TVP, the docking grid was centered along the CD4 binding loop centering it again on D368, with default grid size. Here we used the following: (i) a comparison between docking best ranked poses to their respective orientation at the Phe43 cavity vestibule in WT, variant-2, and variant-3 targets to discriminate between the best target for future blind docking of SMCM’s (not discussed) and (ii) PLIE on the top 10 poses of each set (for a total of 300 PLIE calculations) info to check the correlation with experimental data.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations were performed using NAMD 2.1030 and the CHARMM 22 force field31 to assess the structural stability of the docked poses. A dimethyl-oxalamide moiety was parametrized according to the CHARMM general force field by means of Gaussian 09,32 with input files prepared using VMD 1.9.2,33 in order to transfer the oxalamide parameters to the SMCM’s region 2. The parametrization comprised five steps: (i) geometry optimization using the MP2 level of theory and 6–31G* as basis set; (ii) partial charge computation through single point energy calculations using TIP3P as the water model, the Hartree–Fock (HF) level of theory and 6–31G* as basis set; (iii) partial charges optimization by means of simulated annealing; (iv) bonds and angles optimization using MP2 level of theory and 6–31G* as basis set followed by simulated annealing; and (v) dihedral angle potential optimization using MP2/6–31G*. Our optimized parameter set is reported in the Supporting Information.

To validate the MD protocol, 50 ns MD simulation was run on the cocrystal coordinates of 3, 4, and 5 in gp120 core monomer (PDB ID’s: 4I53, 5F4L, 5F4R, respectively). Then, a 50 ns MD simulation was performed on the apo coordinates of SOSIP 4NCO WT and on the first best-ranked docking pose of 3, 4, and 5 in the 4NCO WT coordinates. To set up the system for the MD runs, a first minimization in vacuo (only H atoms and then the whole protein/ligand complex for a total of 1100 minimization steps) was performed, followed by solvation of the minimized complex in a TIP3P water box 10 Å longer than the protein in all six directions. For the validation MD simulations neutralizing 4 Na+ ions for 3/gp120, and 5 Na+ ions for 4/gp120 and 5/gp120 cocrystals were added. For the MD simulations on the 4NCO target neutralizing 5 Cl− ions for 3/4NCO, and 8 Cl− atoms for 4/4NCO and 5/4NCO encounter complexes were added. During production MD, the temperature was kept constant at 310 K by coupling all non-hydrogen atoms to a Langevin thermostat with a friction coefficient of 5 ps−1. Nonbonded interactions were cut off above 10 Å and smoothed to zero beginning from 9 Å. PME long-range electrostatics with a grid spacing of 2 Å were used, and all bond lengths were constrained using RATTLE.34 Production runs were performed at a constant pressure of 1 bar using a Langevin thermostat35 with an oscillation period of 200 fs and an oscillation decay time of 100 fs. The pressure was calculated using a hydrogen-group based pseudomolecular virial kinetic energy.

MM-GBSA on SMCM/gp120 WT and SMCM/4NCO WT Complexes

To estimate the relative binding free energy of the SMCM/gp120 v-2 pose 1 in gp120 WT and of the SMCM/4NCO WT complexes the MM-GBSA (molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area) method has been employed. The relative binding energy was estimated on a 10 ns MD trajectory for all the 5 SMCM’s discussed here, after removing explicit water and ions. The MM-GBSA energy was computed three subsets for each system: the protein alone, the SMCM alone, and the complex. For each of these subsets, the average GBSA energy was extracted over the simulation that has been performed using the generalized implicit solvent module of NAMD 2.10, setting the dielectric constant for the solvent at 78.5. The binding free energy for each gp120/SMCM and SMCM/SOSIP complex has been calculated as follows:

where G is the average potential energy over the simulation.

Competition ELISA

The ability of SMCMs to inhibit binding of BG505 SOSIP.664 to CD4IgG2 was measured using competition ELISA. Recombinant-purified BG505 SOSIP.664 (100 ng) was immobilized on a 96-well microtiter plate for 2 h at 25 °C. After washing the plate twice with PBS buffer, the plate was blocked with 3% BSA in 1XPBS for 90 min at 25 °C. For the CD4 competition experiments 100 µl of CD4IgG2 (50 ng) was added to each well in the presence of increasing concentrations of SMCMs in 10% DMSO for 1 h at 25 °C. After washing three times with PBST, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated antihuman antibody was added at a 1:5000 dilution and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C. The extent of HRP conjugate binding was detected by adding 200 µL of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and measuring optical density at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

RESULTS

Docking Against Core Monomeric gp120

The design of potent SMCM’s that establish hydrogen bonds with D368, a highly conserved residue located on the vestibule of the Phe43 cavity, has so far proven difficult. While docking studies previously performed on this class of compounds from compound 3 on always reveal such an interaction, their respective X-ray structures did not. Possible reasons for this specific docking “false positive” (hereafter called the “D368-false positive”) can be ascribed to the position of D368 at the cavity vestibule, to the fact that docking is performed in a vacuum environment, both factors logically resulting in the overestimation of protein–ligand interactions when, as is the case here, the relevant part of the ligand is solvent exposed, and to the addition of a degree of freedom at SMCM region III by a CH2 linker between the indane ring at the guanidinium moiety. We therefore developed a modified blind docking procedure that avoids the D368-false positive on core monomeric gp120. Reasoning that the charge on D368 was playing too large a role in determining compound poses, we investigated the WT and two docking target variants (variant-2 and variant-3) of the core monomeric gp120 from the cocrystal structure of compound 3 (PDB ID: 4I53), as described in the Material and Methods section. In order to choose the best target among the three considered cases to use for future SMCM docking/optimization, we determined which reproduced the experimental crystallographic binding pose without showing the D368-false positive in any of the 10 best ranked docking poses. This established a viable procedure for blind SMCM’s docking that correctly orients their positively charged region III.

As expected, the best ranked poses of compounds 1 and 2 into the 4I53 gp120 coordinates were not deeply affected by neutralization of D368. Indeed, both in the WT and variant-2 targets, the first docking pose reproduced fairly well their respective X-ray poses (RMSD = 1.42 and 2.88 Å for 1 X-ray pose/first docking pose in WT and in variant-2, respectively; RMSD = 1.69 and 1.21 Å for 2 X-ray pose/first docking pose in WT and in variant-2, respectively). Figure 3 shows an X-ray pose/first docking pose overlap in variant-2 for the three most potent SMCM’s considered here.

Figure 3.

Overlap of cocrystal poses (cyan sticks) and variant-2 first-rank docking poses in 4I53 coordinates for the SMCM’s (A) 5 (deep teal stick); (B) 4 (yellow stick); (C) 3 (green stick). The protein and hot-spot residue color code is the same as that used in Figure 2.

For compound 3, the H-bond with D368 in the WT target is seen three times in the first ten best-ranked poses. However, in variant-2 and variant-3 no such H-bond is seen. Considering all 10 best ranked poses, the X-ray poses of 3, 4, and 5 were predicted in variant-2 the most. The D368N mutation (variant-3), yielded poses that did not match X-ray poses as well as in variant-2. In order to see if our docking predictions revealed any correlation with experimental infectivity IC50 (previously measured in HIV-1YU2 strain) or KD binding on core monomer,8,9 we computed the SZYBKI-PLIE. We saw that only in variant-2 the first docking pose for all the compounds had a PLIE that follows the same trend as the KD, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Experimental and Computational Data on Binding and Inhibition of CD4 Binding of SMCM’sa

| gp120 4I53 (variant-2) | SOSIP 4NCO (WT) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMCM | IC50 µM (HIV-1YU2)10–12 |

KD µM10–12 |

GlideScore (pose 1) |

SZYBKI PLIE (kcal mol−1) |

MM-GBSA PLIE (kcal mol−1) |

ELISA (IC50 µM sCD4 inhibition) |

GlideScore (pose 1) |

SZYBKI PLIE (kcal mol−1) |

MM-GBSA PLIE (kcal mol−1) |

| 1 | >100 | 3.70 | −8.896 | −14.346 | −26.88 | >100 | −7.143 | −7.971 | −22.95 |

| 2 | 48.8 ± 3.6 | 0.30 | −8.122 | −15.241 | −29.87 | >100b | −5.936 | −11.831 | −24.79 |

| 3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.11 | −9.827 | −18.648 | −32.32 | 9 ± 1.4 | −7.471 | −21.335 | −28.51 |

| 4 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 0.02 | −9.237 | −21.708 | −41.48 | 3 ± 0.42 | −6.799 | −21.925 | −35.37 |

| 5 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.10 | −9.719 | −18.225 | −38.45 | 2.02 ± 0.78 | −8.429 | −22.706 | −32.81 |

SZYBKI and MM-GBSA energy values are computed on the first docking pose for each SMCM in gp120 variant-2 and 4NCO WT targets. The protein targets used to compute the both biding affinities are gp120 WT and 4NCO WT. In bold are highlighted viral infectivity IC50 and sCD4 inhibition IC50 that correlate with SZYBKI-PILE computed on SOSIP 4NCO. In italic are highlighted experimental KD values for binding affinity on gp120 that correlates with SZYBKI-PLIE values on gp120. MM-GBSA in both gp120 and 4NCO follow KD trend.

Solubility limit.

In contrast, the GlideScore did not correlate with the trend in IC50 nor in KD. To further validate our protocol, the MM-GBSA average energy (MM-GBSA-PLIE) on a 10 ns MD trajectory was computed on variant-2 pose 1 in gp120 WT coordinates for all of the five compounds investigated here. Also in this case, we could differentiate between compounds 1 and 2 and the most active second generation SMCM’s compounds 3, 4, and 5. We conclude that our new docking protocol, based on the usage of variant-2 as protein target, is necessary to avoid the D368-false positive when SMCM’s region III is characterized by a strong positive charge and a relatively high flexibility at region III. In addition, the correlation of experimental KD’s and PLIE values of the variant-2 first docking pose for all the compounds considered here support our new docking protocol to be viable for the further optimization of this class of compounds.

Binding Site Search on SOSIP Targets

The binding site searches revealed that SMCM’s recognize the CD4 binding region on SOSIP coordinates. Compound 1 showed all the poses with a negative SZYBKI-PLIE in the CD4 binding site with the first docking pose orienting region I in the Phe43-like cavity and region III at the cavity vestibule (SZYBKI-PLIE = −7.722 kcal mol−1). The 10 best-ranked poses of compound 2 in the CD4 binding site exhibited both favorable and nonfavorable SZYBKI-PLIE values. Docking pose-2 showed region I inside the Phe43-like cavity and region III at the cavity vestibule, with a SZYBKI-PLIE of −4.462 kcal mol−1. For compounds 3, 4, and 5 negative SZYBKI-PLIE poses were in the CD4 binding site, with the lowest energy pose orienting region I in the Phe43-like cavity and region III at the cavity vestibule. Interestingly, docking poses of the most potent compound 5 were already only in the Phe43-like cavity in this preliminary binding search, with region I inserted in the cavity and region III at the cavity vestibule. On the front-side of 4TVP, all five SMCM’s showed favorable SZYBKI-PLIE in complexes where the compounds bind externally along the CD4 binding loop. On the back-side of both 4NCO and 4TVP coordinates, favorable protein/ligand complexes were generated only for compound 1 in 4TVP and for compounds 4 and 5 in both targets. In 4TVP compound 1 is inserted into a small cavity decorated by P206, K207, V208, S209, F210, R304, G379, I439, and Q440, stabilized only by hydrophobic and van der Waals contacts. Interestingly, of the residues in this backside binding site, F210 forms a small hydrophobic accessory pocket in the CD4 bound conformation of gp120 where the BMS compounds should likely access when the gate-keeper residues W112 and F382 are open;36 R304 is part of the V3 loop and I439 and Q440 are part of the V5 loop. It is worth noting that for 2, which differs from the parent compound 1 only in (i) the addition of a fluorine ortho to the chlorine on the region I phenyl and (ii) an N-methyl group at region III, no docking poses on the 4TVP back-side were generated. The formation of favored encounter complexes on the 4NCO and 4TVP back-side can be ascribed to the high density of negatively charged residues at the protein surface for both proteins and the high positive charge density at compounds 4 and 5 region III. Indeed, while on the front-side we can find the energetically favored docking poses all in one area of the protein, namely in the CD4 binding site, and in agreement with each other in terms of orientation, on the back side all favored poses are not agreement between each other. It is likely that 1, 4, and 5 back-side sites on SOSIP are all false positives. This consideration notwithstanding, binding of the small molecule to the protein back-side would likely not affect CD4 binding. Given these results, subsequent and more precise docking calculations were focused on the CD4 binding region on both SOSIP coordinates 4NCO and 4TVP.

Focused Docking on SOSIP Targets

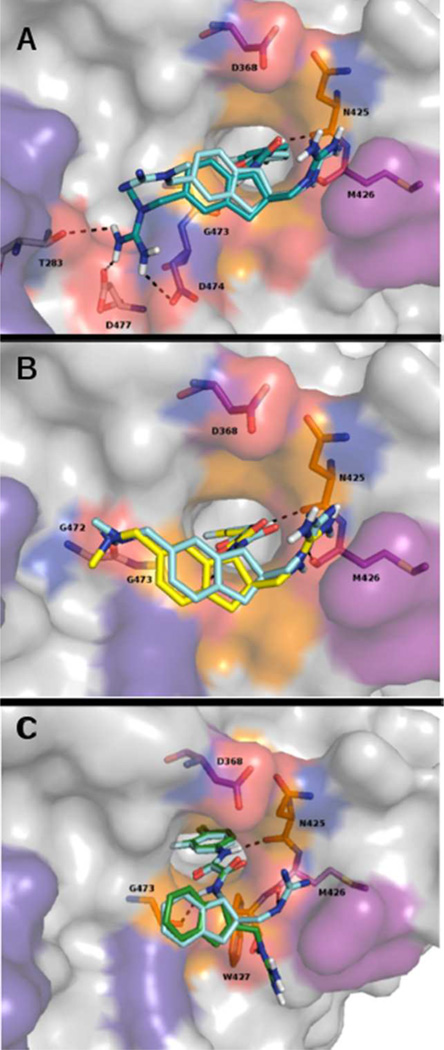

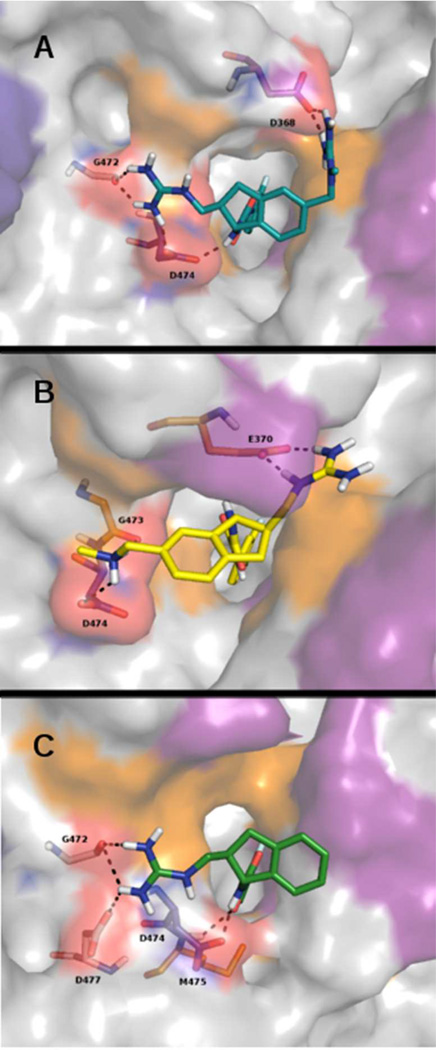

The WT target from the 4NCO SOSIP structure yielded first-ranked docking poses for all compounds with region I in the Phe43-like cavity and region III at the cavity vestibule. We report first-rank SZYBKI- and MM-GBSA-PLIE’s for docking against the WT 4NCO SOSIP target in Table 1 and depict first-rank docking poses for compounds 3, 4, and 5 in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

5 (A), 4 (B), and 3 (C) first-rank docking poses in 4NCO WT coordinates. The protein and hot-spot residue color code is the same as in Figure 2.

Residue contacts in all first-rank poses are reported in Table 2. The data in Table 2 are arranged according to the known “hot-spot” residues implicated in the binding of CD4 to gp120, in which three types of hot-spot residues are delineated: high affinity and allosteric effect (I371, G473, M475, E370, W427, N425); high affinity and moderately allosteric effect (D368, M426, V430, E429); and only affinity (N280, N279, K282, D457, A281, T455, D474) as defined by Freire et al.16–18 Compounds 3, 4, and 5 showed the most favorable PLIE (−21.335; −21.925; −22.706 kcal mol−1, respectively), followed by 2 (−11.831 kcal mol−1) and 1 (−7.971 kcal mol−1). From these data, it is evident that SMCM’s engage more hot-spot residues in the 4NCO complexes than in the 4TVP complexes. In addition, although D368 was negatively charged in the WT target, no H-bond from 3 and 4 engages this residue in the first-rank pose. The D368-H bond is only seen when region III is decorated by two guanidinium moieties, as in compound 5. Even though the 4TVP WT target yielded first-rank poses for all compounds along the CD4 binding loop, with 3, 4, and 5 participating in an H-bond with D368, the SZYBKY-PLIE’s for all compounds showed no correlation with experimental IC50 nor KD values or inhibition of sCD4 binding. Hence, we did not compute also the MM-GBSA PLIE on this target and we conclude that 4TVP is unlikely to be useful for future SMCM’s docking/optimization.

Table 2.

gp120-CD4 Hot-Spot Residues16–18 in Contact with SMCM’s in Observed (“X-ray”) and Predicted (“4NCO”) Binding Posesa

| SMCM (−TΔSkcal mol−1) |

X-ray | 4NCO | gp120-CD4 hot-spot type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N425, W427, G473, M475 |

G473, N425 | allosteric |

| 17.110 | M426, E429, V430 |

allosteric/ affinity |

|

| D474b | D474b | affinity | |

| 2 | G473, N425, W427 |

N425, G473, E470 | allosteric |

| 10.910 | M426 | allosteric/ affinity |

|

| N474b | D474b | affinity | |

| 3 | N425, W427, E370 |

N425, M475, G473, V371, E370, W427 |

allosteric |

| 8.411 | M426, E429 | M426 | allosteric/ affinity |

| D474b | D474b | affinity | |

| 4 | G473, N425, W427 |

N425, E370, V371, G473, M475 |

allosteric |

| 17.812 | M426, E429 | M426 | allosteric/ affinity |

| D474b | D474b | affinity | |

| 5 | N425, W427 | N425, E370, V371, G473, M475 |

allosteric |

| 5.812 | M426, E429 | D368, M426 | allosteric/ affinity |

| D474b | affinity |

For each compound, the first row indicates residues in the allosteric hot-spot, the second row the combined allosteric/affinity hot-spot, and the third row the affinity hot-spot.

MD Simulations

The MD protocol was validated on the cocrystal coordinates of compounds 3, 4, and 5 in gp120 core monomer (PDB ID’s: 4I53, 5F4L, and 5F4R, respectively). During the 50 ns simulation, all compounds remain tightly bound to the protein maintaining the most important interactions shown in their respective cocrystal binding pose. The validated MD protocol was then applied to the apo 4NCO coordinates and on the 3/4NCO, 4/4NCO, and 5/4NCO encounter complexes. The encounter complex 3/4NCO is characterized by high flexibility and a major conformational change during the 50 ns MD simulation where residues 53–79 and residues 202–215, which are adjacent to α1 and β2, rearrange to turn the 4NCO Phe43-like cavity into a deep tunnel. Even binding in the same area of the protein, the initial binding mode similarity shared between 3/4NCO encounter complex and the cocrystal coordinates observed in the docking study is lost. Indeed, the major H-bonds that stabilize compound 3 in the cocrystal coordinates are mostly lost during the MD simulation in 4NCO coordinates, as can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Conserved H-Bonds between SMCM Cocrystal Coordinates and SMCM/4NCO Encounter Complexes over the 50 ns MD simulation for the most active compounds 3, 4 and 5

| SMCM | H-bond | cocrystal | 4NCO occupancy % (50 ns MD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | N425-region II | yes | 0 |

| G473-region II | yes | 9.44 | |

| G472-region III | no | 0.10 | |

| M426-region III | yes | 0 | |

| 4 | N425-region II | yes | 2.35 |

| G473-region II | yes | 12.68 | |

| G472-region III | yes | 0.28 | |

| M426-region III | yes | 0 | |

| 5 | N425-region II | yes | 4.08 |

| G473-region II | yes | 0 | |

| G472-region III | no | 0.17 | |

| M426-region III | yes | 0 |

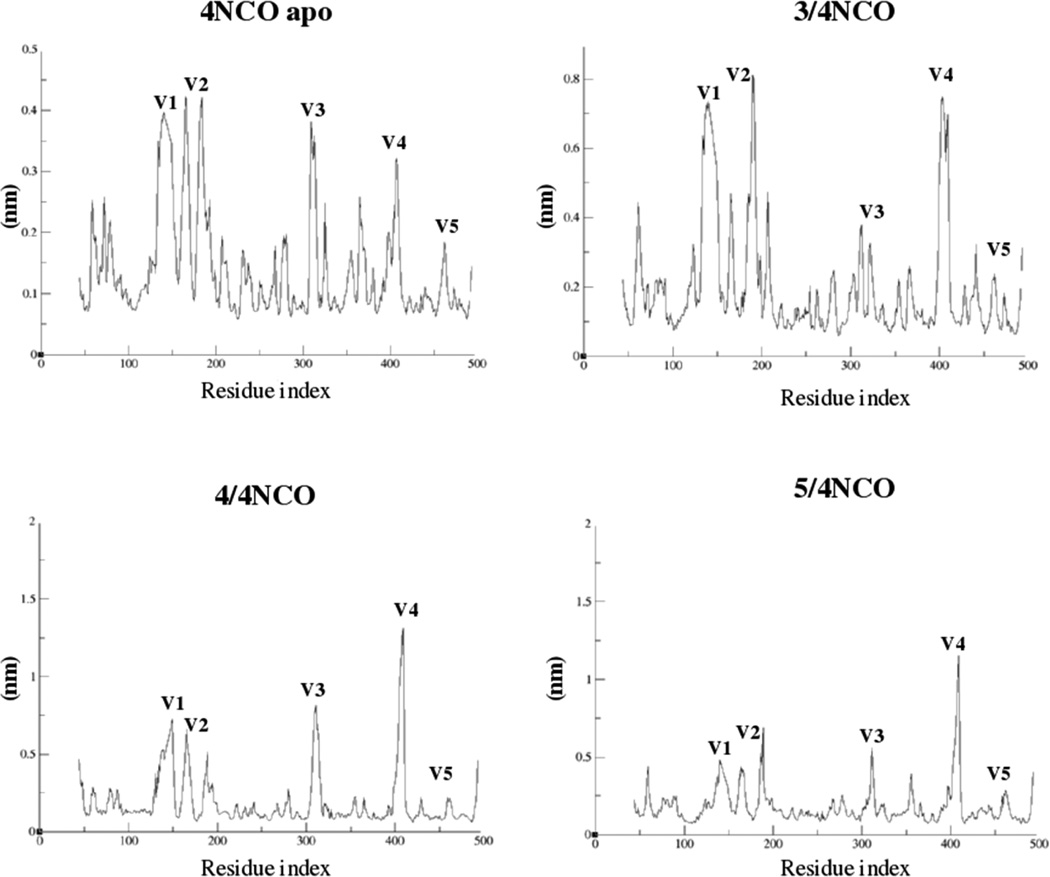

The interactions that stabilize compound 3 in the newly formed encounter complex are between region III guanidinium moiety and the conserved residue D474 (occupancy = 22.76%); π-stacking interactions between region I and the two gatekeeper residues F210–W11236 and W427; and hydrophobic contacts between region I and G473. Other H-bonds observed over the 50 ns MD trajectory are between region II oxygen and M475 (high affinity and allosteric effect hot-spot region, with an occupancy of 6.17%); and between region II nitrogen and G473 (occupancy of 8.97%). In addition, compound 3 initial docking pose rotates about 45° during the MD simulation, orienting the phenyl ring toward D368. This pose is very similar to the first docking pose shown by compound 4 in 4NCO WT coordinates. Compounds 4 and 5 remain tightly bound in their binding site over the 50 ns MD simulation, also stabilizing the protein as can be seen if comparing the root-mean-square fluctuation (rmsf) plot of the apo 4NCO with the rmsf plot of the encounter complexes in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Root-mean-squared fluctuation (nm) vs residue index plot for apo 4NCO and the most active compounds 3, 4, and 5 in SOSIP 4NCO coordinates.

Even if the H-bonds between their region II and N425 and G473 are not characterized by a high occupancy (Table 3), the compounds remain well-inserted in the Phe43-like cavity over the MD simulation. At the Phe43-like cavity vestibule, the guanidinium side chain is the major anchor point to the protein for both compounds, as demonstrated by the high occupancy of H-bonds over the 50 ns MD simulation. Compound 4’s guanidinium side chain donates an H-bond to E370 with an overall occupancy of 79.71%. Compound 5’s guanidinium side chain donates an H-bond to D474 with an overall occupancy of 39.86%. The highest degree of flexibility in the binding of compounds 4 and 5 is the methylamino side chain for compound 4 and the methyl-guanidinium side chain for compound 5, both linked to region III phenyl ring. Hence, for both compounds this should be the part of the structure that requires further optimization in the perspective of improving their binding to 4NCO coordinates. In particular, we propose decreasing flexibility in the phenyl-side chain rotation by removing the methyl linker and attaching the methylamino chain for compound 4 and methyl-guanidinium chain for compound 5 directly to the region III phenyl ring. We reason that this would allow compound 4 to reach more easily the D474 side chain (9.15% H-bond occupancy during the 50 ns MD); and compound 5, R429 and G472 backbone (21.39% and 9.37% H-bond occupancy during the 50 ns MD, respectively). It is also worth noting that, while compound 5 immediately loses the guanidinium-D368 H-bond when subjected to MD simulation (occupancy = 0.82%), compound 4 immediately reaches this residue, making a H-bond with an occupancy of 30.43%.

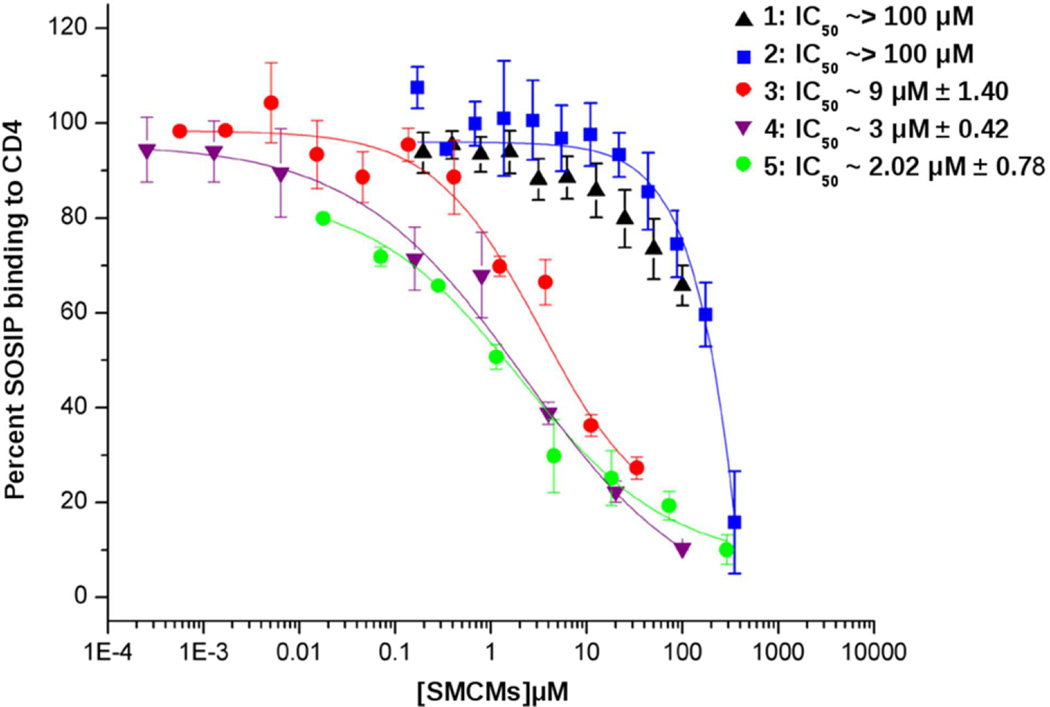

Competition with sCD4 via ELISA

All five SMCM’s considered here are known to inhibit binding of soluble CD4 (sCD4) to core monomeric gp120.9–11 However, although our computational studies predict high-affinity binding to at least the 4NCO target, until this study, it was not known whether or not SMCM’s inhibit binding of sCD4 to authentic SOSIP soluble trimers. To settle this question, we used ELISA to measure the ability of the three SMCM’s to inhibit sCD4 binding in BG505 SOSIP.664 (as described in the Material and Methods section). The data are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Competition of SOSIP trimer binding to CD4IgG2 in the presence of SMCMs. Shown are the dose response curves determined from the effect on BG505 SOSIP.664 interaction with CD4IgG2 via ELISA (n = 3).

Of particular note, 3, 4, and 5 competed most potently for binding of SOSIP to sCD4, with an IC50 value of 9 µM, 3 µM and 2.02 µM, respectively. In contrast, weaker inhibition of SOSIP trimer protein binding to sCD4 was observed with both 1 and 2. A full dose response could not be achieved in these latter two cases owing to solubility limits. Hence, possible differences between 1 and 2 competition potencies could not be properly differentiated.

DISCUSSION

Neutralized D368 is Necessary for Blind Docking to Predict Crystallographic Poses

Because D368 is so highly conserved, it is reasonable to try to optimize gp120 binders to interact with it. Indeed, much of the motivation toward the design of SMCM’s was to that end, and it was somewhat surprising to see that the cocrystal structure from compounds 3 on did not show this interaction while previously docking studies did.11,12 Indeed, in the current work, docking models of 3, 4, and 5 on WT core monomeric gp120 continue to predict the D368-false positive interaction with their region III. With our new docking protocol based on the neutralization of D368, we were finally able to recapitulate the correct crystallographic orientation at the cavity vestibule of 3, 4, and 5 on core monomeric gp120. In addition, on 4NCO and 4TVP targets that are not in the gp120-activated state, SMCM’s bind in the CD4 binding-site region with negative SZYBKI-PLIE values only when D368 is charged. This observation suggests that D368 is likely to be more important on the kinetic path to SMCM’s interaction before gp120 acquisition of the CD4-bond state, rather than stabilization of the final complex.

SMCM’s Specifically Recognize the CD4 Binding Site Region on Non-Activated gp120

Our results clearly predict that SMCM’s interact preferentially with the CD4 binding site region of both SOSIP targets, irrespective of the disposition of the Phe43 cavity region and the bridging sheet (or lack thereof). On the 4NCO target, the existence of a cavity similar to the Phe43 cavity of core monomeric gp120 in complex with CD4 evidently allowed for binding of SMCM’s in poses very similar to those displayed in core monomeric gp120. Importantly, however, the 4NCO structure lacks the bridging sheet seen in all core monomeric gp120 crystal structures with bound SMCM’s. Because our computational rank-ordering of compounds and their respective PLIE values on the 4NCO SOSIP target correlates to both the KD’s in binding thermodynamics studies as well as to their ability to inhibit sCD4 binding to SOSIP proteins, we conclude that there is a very high likelihood that SMCM’s bind to SOSIP in ways that are functionally relevant for their anti-HIV activity. This is also supported by the detailed list of residue contacts observed in the 4NCO target complexes. Even the 4TVP structure, which lacks a recognizable Phe43 cavity, is predicted to bind SMCM’s with moderately high affinity only along the CD4 loop. The fact that the PLIE’s of these complexes do not yield a consistent trend with respect to anti-infectivity IC50’s or sCD4 competition leads to the possibility that these predicted states represent possible encounter complexes that can mature into high-affinity complexes upon a fortuitous fluctuation of the protein that opens the Phe43-like cavity.

Protein–Ligand Interaction Energies of First-Rank Poses on WT 4NCO SOSIP Correlate to Both Viral Infectivity IC50 and Inhibition of sCD4 Binding to Authentic BG505 SOSIP.664 Trimers

As illustrated in Table 1, our predicted binding poses of 3, 4, and 5 yielded the most favorable PLIE, followed in order by 1 and 2. Previous binding thermodynamics studies on core monomeric gp120 yielded the same ordering of these compounds according to KD.9–11 Here, we also demonstrated from ELISA assays using authentic BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer that 3, 4, and 5 are the most effective in inhibiting sCD4 binding. The correlation of 3, 4, and 5 favorability in ELISA and computation suggests that (i) the 4NCO SOSIP structure is a viable target for de novo docking and optimization of SMCM’s despite the somewhat low resolution and (ii) the BG505 SOSIP.664 protein can be a useful tool in rationalizing links between protein structure and HIV infectivity, at least in regards to SMCM activity. The lack of such binding in the 4TVP structure is likely due to the fact that this structure does not display any Phe43-like cavity. It is possible that the secondary antibody used in the crystallization of 4TVP (which was not present for 4NCO), stabilized a gp120 conformation lacking this pocket, which is otherwise transiently accessible. In addition, it is interesting that the previously identified SAR for the SMCM’s on core momeric gp120 can be translated also to the SOSIP 4NCO coordinates, where there is no bridging sheet. Also in the 4NCO target, SMCM’s scaffold can be divided into the three well-known regions: region I is inserted in the Phe43-like cavity; region II occupies the same area as the CD4 Phe43 residue if superimposing the coordinates of 4NCO and gp120 bound to CD4; and region III is at the Phe43-like cavity vestibule. This correspondence in the pharmacophore position among all SMCM’s and between both core monomer gp120 and SOSIP gp140, which we demonstrate here, is important because it means we can continue to use SOSIP coordinates to pursue further structure-based optimization of SMCM’s.

Possible Optimization of SMCM’s in the SOSIP 4NCO Coordinates Aiming at Preventing Bridging Sheet Formation

The gp120 monomer extracted from the 4NCO SOSIP model is conformationally distinct from the activated (CD4-bound) conformation of core monomeric gp120, in particular in the lack of the bridging sheet and the lack of a fully formed Phe43 cavity. The first docking pose of compounds 3 and 5 in the 4NCO coordinates show the same orientation at the CD4-binding site region as in the gp120 CD4-bound state, while compound 4 shows region III rotated of about 45°, with the methylamino side chain oriented toward D368, but H-bonding with it only upon MD simulation. As can be seen from the rmsf plot (Figure 5), compound 3 is the one inducing the least degree of stabilization in the protein upon MD simulation. In addition, the 3/4NCO encounter complex loses the initial similarity between the Phe43 cavity in gp120-CD4 bound state and the Phe43-like cavity. Compounds 4 and 5 induce a high stabilization in the protein as can be seen by the rmsf plot in Figure 5, suggesting that they are a good starting point for future optimization of SMCM’s using SOSIP 4NCO as a de novo target. From this study it is evident that the addition of the second side chain at the region III phenyl ring, as in compounds 4 and 5, is key for stabilizing SMCM’s in gp120 nonactivated state. Indeed, compound 3 forms a favorable encounter complex with SOSIP 4NCO but is characterized by high flexibility in MD simulation, and compounds 1 and 2 lacking any anchor point to the protein coming off their region III do not form highly favored encounter complexes and do not compete with sCD4 in the ELISA assays. Taken together, these observations lead us to argue that two side chains on the region III indane ring are very important for stabilizing SMCM’s in the 4NCO coordinates, while this is not necessary in core monomeric gp120, since compound 3 with even its single guanidinium side chain in region III is already highly stable in the gp120-CD4 bound state. In addition, we hypothesize that the newest SMCM’s can be optimized in the 4NCO coordinates with the future aim of designing compounds that specifically inhibit bridging sheet formation, blocking HIV infection at an earlier stage than do the current-generation SMCM’s.

CONCLUSIONS

We have employed a multipronged computational analysis combined with experiments to evaluate the suitability of two BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer coordinates as targets for de novo docking of SMCM entry inhibitors. First, we found that recapitulation of crystallographic poses of SMCM’s on core monomeric gp120 using docking requires neutralization of D368. However, D368 in the ionic form at physiological pH is necessary for identifying the CD4-binding-site region using SMCM’s via large-scale binding site search on SOSIP coordinates, suggesting a kinetic role of D368 in the acquisition of a high-affinity bound state of SMCM’s. Second, ELISA assays revealed that compounds 3, 4, and 5 yielded the largest degree of competition with sCD4 for binding to authentic BG505 SOSIP.664 protein, with 2 and 1 displaying finite but smaller effects. The computational prediction that compounds 3, 4, and 5 more favorably bind to SOSIP based on both SZYBKI- and MM-GBSA-PLIE magnitudes than do compounds 1 and 2 correlates well with these assay results. MD simulation results gave us a more complete view of the binding of the most active compounds 4 and 5 in SOSIP coordinates, driving us toward a possible optimization of those compounds in gp120 non-activated state and in particular supporting region III analogs with at least two indane side chains. These results lead us to hypothesize that the most potent SMCM’s bind gp120 before the acquisition of the optimal conformation for CD4 binding. This observation opens up a new perspective to optimize SMCM’s and use them in combination with compounds preventing the formation of the bridging sheet that do not have affinity for the Phe43 cavity, potentially representing a new way to block HIV-1 entry at the very earliest steps.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged (P01 GM-056550). Simulations reported in this work were run in part on hardware supported by the Drexel University Research Computing Facility and by the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE),38 which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1053575.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SMCM

small molecules CD4 mimics

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- CCR5

C–C chemokine receptor type 5

- CXCR4

C–X–C chemokine receptor type 4

- Env

envelope

- MD

molecular dynamics

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

- (i) Parameters for SMCM’s oxalamide linker; (ii) compounds 1 and 2 binding poses in gp120 WT, SOSIP 4NCO WT and SOSIP 4TVP WT; (iii) compounds 3, 4, and 5 binding poses in gp120 WT, gp120 variant-3 and SOSIP 4TVP WT; (iv) PLIE values of the five SMCM’s in gp120 core monomer coordinates WT and variant-3 and SOSIP 4TVP WT along with experimentally determined KD on monomeric gp120, antiviral IC50, and ELISA-based CD4 competition (PDF) All pdb files corresponding to the docking poses reported in Table S3 (ZIP)

Author Contributions

F.M. performed the computational studies. K.A. performed the ELISA assays. B.M. synthesized the SMCM compounds used in the assays. F.M., A.B.S., I.C., and C.F.A. wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to writing and gave approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herschhorn A, Gu C, Espy N, Richard J, Finzi A, Sodroski JG. A Broad HIV-1 Inhibitor Blocks Envelope Glycoprotein Transitions Critical for Entry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:845–852. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada Y, Ochiai C, Yoshimura K, Tanaka T, Ohashi N, Narumi T, Nomura W, Harada S, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. CD4 Mimics Targeting the Mechanism of HIV. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:354–358. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narumi T, Arai H, Yoshimura K, Harada S, Hirota Y, Ohashi N, Hashimoto C, Nomura W, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. CD4 Mimics as HIV Entry Inhibitors: Lead Optimization Studies of the Aromatic Substituents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohashi Y, Harada S, Mizuguchi T, Irahara Y, Yamada Y, Kotani M, Nomura W, Matsushita S, Yoshimura K, Tamamura H. Small-Molecule CD4 Mimics Containing Mono-cyclohexyl Moieties as HIV Entry Inhibitors. Chem Med Chem. 2016;11:940–946. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courter JR, Madani N, Sodroski JG, Schön A, Freire E, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Chaiken IM, LaLonde JM, Smith AB., III Structure-Based Design, Synthesis and Validation of CD4-Mimic Small Molecule Inhibitors of HIV-1 Entry: Conversion of a Viral Entry Agonist to an Antagonist. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:1228–1237. doi: 10.1021/ar4002735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Q, Ma L, Jiang S, Lu H, He Y, Strick N, Neamati N, Debnath AK, Liu S. Identification of N-phenyl-N′-(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidin-4-yl)-oxalamides as a New Class of HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors that Prevent gp120 Binding to CD4. Virology. 2005;339:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madani N, Schön A, Princiotto AM, Lalonde JM, Courter JR, Soeta T, Ng D, Wang L, Brower ET, Xiang SH, Kwon YD, Huang CC, Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Freire E, Smith AB, III, Sodroski J. Small-Molecule CD4 Mimics Interact With a Highly Conserved Pocket on HIV-1 gp120. Structure. 2008;16:1689–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curreli F, Kwon YD, Zhang H, Yang Y, Scacalossi D, Kwong PD, Debnath AK. Binding Mode Characterization of NBD Series CD4-Mimic HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors by X-Ray Structure and Resistance Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5478–5491. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03339-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon YD, Finzi A, Wu X, Dogo-Isonagie C, Lee LK, Moore LR, Schmidt SD, Stuckey J, Yang Y, Zhou T, Zhu J, Vicic DA, Debnath AK, Shapiro L, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Sodroski JG, Kwong PD. Unliganded HIV-1 gp120 Core Structures Assume the CD4-Bound Conformation with Regulation by Quaternary Interactions and Variable Loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:5663–5668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112391109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaLonde JM, Kwon YD, Jones DM, Sun AW, Courter JR, Soeta TK, Kobayashi T, Princiotto AM, Wu X, Schon A, Freire E, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Sodroski JG, Madani N, Smith AB., III Structure-Based Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of Dual Hotspot Small-Molecule HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:4382–4396. doi: 10.1021/jm300265j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaLonde JM, Le-Khac M, Jones DM, Courter JR, Park J, Schon A, Princiotto AM, Wu X, Mascola JR, Freire E, Sodroski JG, Madani N, Hendrickson WA, Smith AB., III Structure-Based Design and Synthesis of an HIV-1 Entry Inhibitor Exploiting X-Ray and Thermodynamic Characterization. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:338–343. doi: 10.1021/ml300407y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melillo B, Liang S, Park J, Schön A, Courter J, LaLonde JM, Wendler DJ, Princiotto AM, Seaman MS, Freire E, Sodroski JG, Madani N, Hendrickson WA, Smith AB., III Small Molecule CD4-Mimics: Structure-Based Optimization of HIV-1 Entry Inhibition. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:330–334. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrickson WA, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski JG, Kwong PD. Structure of an HIV gp120 Envelope Glycoprotein in Complex with the CD4 Receptor and a Neutralizing Human Antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA. Crystal Structure of a Soluble Cleaved HIV-1 Envelope Trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, Stewart-Jones GB, Stuckey J, Bailer RT, Joyce MG, Louder MK, Tumba N, Yang Y, Zhang B, Cohen MS, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Morris L, Munro JB, Blanchard SC, Mothes W, Connors M, Kwong PD. Structure and Immune Recognition of Trimeric Pre-Fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014;514:455–4561. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Schön A, Freire E. Optimization of CD4/gp120 Inhibitors by Thermodynamic-Guided Alanine-Scanning Mutagenesis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013;81:72–78. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schön A, Lam SY, Freire E. Thermodinamics-Based Drug Design: Strategies for Inhibiting Protein-Proteon Interactions. Future Med. Chem. 2011;3:1129–1137. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schön A, Madani N, Smith AB, III, LaLonde JM, Freire E. Some Binding-Related Drug Properties are Dependent on Thermodynamic Signature. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2011;77:161–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.01075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maestro, version 9.8. New York, NY: Schrödinger, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prime, version 3.6. New York, NY: Schrödinger, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epik, version 2.8. New York, NY: Schrödinger, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelley JC, Cholleti A, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Timlin MR, Uchimaya M. Epik: a Software Program for pKa Prediction and Protonation State Generation for Drug-Like Molecules. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2007;21:681–691. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenwood JR, Calkins D, Sullivan AP, Shelley JC. Towards the Comprehensive, Rapid, and Accurate Prediction of the Favorable Tautomeric States of Drug-Like Molecules in Aqueous Solution. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2010;24:591–604. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glide, version 6.3. New York, NY: Schrödinger, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shaw DE, Shelley M, Perry JK, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, Beard HS, Frye LL, Pollard WT, Banks JL. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein-Ligand Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wlodek S, Skillman AG, Nicholls A. Ligand Entropy in Gas-Phase, Upon Solvation and Protein Complexation. Fast Estimation with Quasi-Newton Hessian. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:2140–2152. doi: 10.1021/ct100095p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. revision D.01. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen HC. Rattle: A Velocity Version of the Shake Algorithm for Molecular-Dynamics Calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 1983;52:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brünger A, Brooks CB, Karplus M. Stochatsic Boundary Conditions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations of ST2 Water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1984;105:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker CG, Dahlgren MK, Tao RN, Li DT, Douglass EF, Jr, Shoda T, Jawanda N, Spasov KA, Lee S, Zhou N, Domaoal RA, Sutton RE, Anderson KS, Krystal M, Jorgensen WL, Spiegel DA. Illuminating HIV gp120-ligand Recognition through Computationally-Driven Optimization of Antibody-Recruiting Molecules. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:2311–2317. doi: 10.1039/C4SC00484A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schön A, Brown RK, Hutchins BM, Freire E. Ligand Binding Analysis and Screening by Chemical Denaturation Shift. Anal. Biochem. 2013;443:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Towns J, Cockerill T, Dahan M, Foster I, Gaither K, Grimshaw A, Hazlewood V, Lathrop S, Lifka D, Peterson GD, Roskies R, Scott JR, Wilkens-Diehr H. XSEDE: Accelerating Scientific Discovery. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2014;16:62–74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.