Significance

Political polarization on important issues can have dire consequences for society, and divisions regarding the issue of climate change could be particularly catastrophic. Building on research in social cognition and psychology, we show that temporal comparison processes largely explain the political gap in respondents’ attitudes towards and behaviors regarding climate change. We found that conservatives’ proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors improved consistently and drastically when we presented messages that compared the environment today with that of the past. This research shows how ideological differences can arise from basic psychological processes, demonstrates how such differences can be overcome by framing a message consistent with these basic processes, and provides a way to market the science behind climate change more effectively.

Keywords: climate change, temporal comparison, political ideology, attitudes, framing

Abstract

Conservatives appear more skeptical about climate change and global warming and less willing to act against it than liberals. We propose that this unwillingness could result from fundamental differences in conservatives’ and liberals’ temporal focus. Conservatives tend to focus more on the past than do liberals. Across six studies, we rely on this notion to demonstrate that conservatives are positively affected by past- but not by future-focused environmental comparisons. Past comparisons largely eliminated the political divide that separated liberal and conservative respondents’ attitudes toward and behavior regarding climate change, so that across these studies conservatives and liberals were nearly equally likely to fight climate change. This research demonstrates how psychological processes, such as temporal comparison, underlie the prevalent ideological gap in addressing climate change. It opens up a promising avenue to convince conservatives effectively of the need to address climate change and global warming.

A spirit of innovation is generally the result of a selfish temper and confined views. People will not look forward to posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors.

—Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790

Despite strong evidence that humans are causing global warming (1), there is continuing debate surrounding the issue. Political ideology has been shown to be the strongest predictor of politicians’ beliefs regarding climate change (2), and political polarization of beliefs regarding climate change in the United States has increased in recent years (3). Generally, these trends are characterized by relatively low and decreasing support from conservatives (2–4). The link between conservatism and low support for action addressing climate change can have negative social and economic consequences. For instance, simply labeling an energy-efficient product with a message mentioning climate change can reduce the likelihood that politically conservative individuals will purchase the product (5). What explains this stark divide characterized by conservatives’ relatively unfavorable attitudes and behaviors, and how can it be overcome?

We address this question using insights from research in psychology and propose that the divide can be explained, in part, by different tendencies in temporal comparisons made by liberals and conservatives. In particular, conservatives tend to evaluate the present relative to the way things were in the past. The tendency for conservatives to be past-focused can be traced to the origins of conservatism. Attitudes such as those expressed in the introductory quotation from Edmund Burke, widely regarded as the philosophical founder of political conservatism, emerged as a reaction to revolutionary movements that sought to break radically with tradition (6–8). Thus, conservative ideology can be traced to the desire to defend the status quo against progressive change, preferring regressive change instead, whereas liberals seek to replace present society with a newer system (9).

Research has shown that conservatives more strongly endorse tradition and conformity and prefer the certainty of the past to the uncertainty of tomorrow (10). These tendencies play out in the political arena as well: Republican presidents refer to the past to a greater extent than Democratic ones in their State of the Union addresses (11). Moreover, conservatives are said to feel a romantic or nostalgic longing for the way society was (12, 13), suggesting that conservatives view progressive policies and ideas as pushing society further away from the cherished past. Indeed, in public opinion surveys in the United States conservatives consistently show stronger beliefs that the state of society is in decline (14, 15).

Against this backdrop, a potential problem becomes clear: Appeals for addressing climate change often adopt a future-focused temporal perspective. Consider an example from United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon: “The clear and present danger of climate change means we cannot burn our way to prosperity …We need to find a new, sustainable path to the future we want” (16). Similar future-focused messages appear in Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth, which presents viewers with images of a scorched and dry future earth (17). What these messages have in common is that they compare the current state of the Earth against a possible future. Simply put, these appeals aim to convince the audience that drastic action against climate change must be taken to create a better future (or to avoid a worse future).

These future comparisons are speculative and often are accompanied by propositions to change the socioeconomic status quo. Conservatives may find such propositions aversive because they violate the tenants of conservative ideology. Furthermore, if conservatives associate progressive change with decline (14, 15), these future-focused messages are unlikely to be convincing. It follows then that conservatives’ relatively low support for action addressing climate change may not result from an inherent disbelief in scientific evidence (18) but could be attributed to a lack of fit between future-focused environmentalist appeals and conservatives’ dominant past-focused temporal orientation.

Reframing the appeals for addressing climate change to fit conservatives’ ideology has proven successful in changing conservatives’ attitudes and behaviors. For instance, conservatives expressed more proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors when doing so was framed as an obligation to one’s nation (19) or when climate change was described in terms of “contamination” and “purity” as opposed to “harm” and “care” (20). Conservatives’ skepticism about climate change science decreased if the solution to climate change was described as supporting capitalism (21). In other words, conservatives can become more proenvironmental when being so aligns with morals and values that are consistent with their world view.

Our approach is similar: Conservatives can become more proenvironmental when appeals to address climate change are framed with a past-focused comparison. Conservatives view the past as better than the present, so an argument that encourages returning to the past will be appealing. Furthermore, any proposed changes to society that are rooted in past comparisons should not be hindered by the uncertainty and decline that conservatives associate with progressive, or future-focused, changes. Altogether, a past-focused framing may encourage conservatives to estimate a greater risk of climate change because the evidence for climate change provided by a past-focused comparison fits with their predominant cultural outlook. On the other hand, future-focused messages may lead conservatives to underestimate the risk of climate change because of a misfit between the framing of evidence and their typical cultural outlook (22).

To test these hypotheses, we recruited participants online via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a web-based tool for recruiting and paying participants to perform tasks. MTurk samples tend to produce results that are as valid and reliable as laboratory-based samples (23) and have been shown to be as representative of the United States population as other sampling methods used in political science research (24–26). To avoid the most critical problem with Mturk samples—nonnaiveté (27)—participants were barred from taking part in more than one of our studies. We predicted that past-focused climate messages would be effective in promoting proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors among conservatives. All studies were covered under Institutional Review Board approval from the Social Cognition Center Cologne, and participants provided consent by clicking a box on the first page of each study.

Methods and Results

Study 1.

Method.

In study 1, participants were randomly assigned to read a message about climate change that drew a comparison either between the present and the future (future-focused, e.g., “Looking forward to our nation’s future … there is increasing traffic on the road”) or between the present and the past (past-focused; e.g., “Looking back to our nation’s past … there was less traffic on the road”). Participants were told that a previous participant wrote the message in response to a prompt asking the participant to describe a current social issue. We also randomly varied whether the ostensible participant self-reported as a liberal or conservative and treated this variable as a between-subjects factor in our analyses. After reading the message, participants evaluated the message and reported their attitudes about the environment and climate change.

Results.

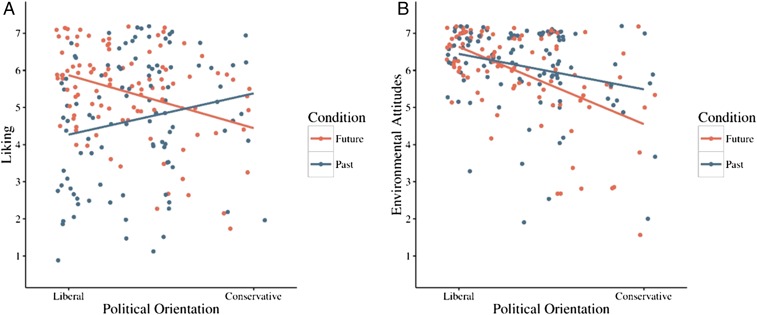

As expected, conservatives evaluated the future-focused climate change message less positively (b = −0.24, P = 0.003), whereas the opposite was true for the past-focused message (b = 0.19, P = 0.026; interaction b = 0.42, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). Reading a past-focused message also increased conservatives’ proenvironmental attitudes. The association between conservatism and less favorable environmental attitudes was reduced by almost half in the past-focused condition (b = −0.16, P = 0.009) compared with the future-focused condition (b = −0.35, P < 0.0001; interaction b = 0.19, P < 0.03) (Fig. 1B). There was no moderating effect of the ostensible participant’s political orientation on these findings (P > 0.47), suggesting that the temporal framing was effective even when the source of the message was a member of a political out-group (detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 1).

Fig. 1.

Study 1. (A) Conservatives dislike the future-focused but not past-focused environmental message. (B) Conservatives report more favorable environmental attitudes after reading a past-focused message (blue line) than after reading a future-focused message (red line).

Study 2.

Method.

To isolate further the effect of temporal comparison on conservatives’ attitudes, study 2 exposed participants to the past and future comparisons from study 1 or to a nonenvironmental control message about the ISIS terrorist organization. Again the message was communicated by a participant ostensibly from a previous study, but in this study all messages were from a self-reported political moderate. After reading the message, participants completed the environmental attitude measure from study 1.

Results.

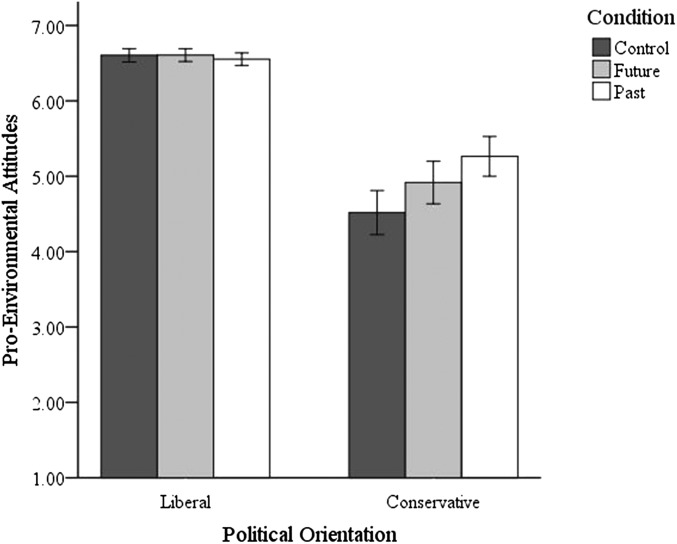

As predicted, and in accordance with study 1, we found that conservatives expressed more favorable attitudes in the past-focused condition than in the control condition (P = 0.007, d = 0.44) or in the future-focused condition although the effect was not statistically significant (P = 0.21). Conservatives’ attitudes were more favorable in the future-focused condition than in the control condition, but this simple effect also was not significant (P = 0.14). However, conservatives’ attitudes increased linearly across the control, future, and past-focused conditions (b = 0.37, SE = 0.14, P = 0.007); the past-focused condition was most effective in bolstering conservatives’ proenvironmental attitudes (Fig. 2). Liberals’ attitudes did not differ as a function of temporal comparison (P = 0.97). Detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 2).

Fig. 2.

Study 2. A past-focused message (white bars) is most effective in improving conservatives’ proenvironmental attitudes. Temporal focus does not affect liberals’ attitudes. Error bars represent SEs.

Study 3.

Method.

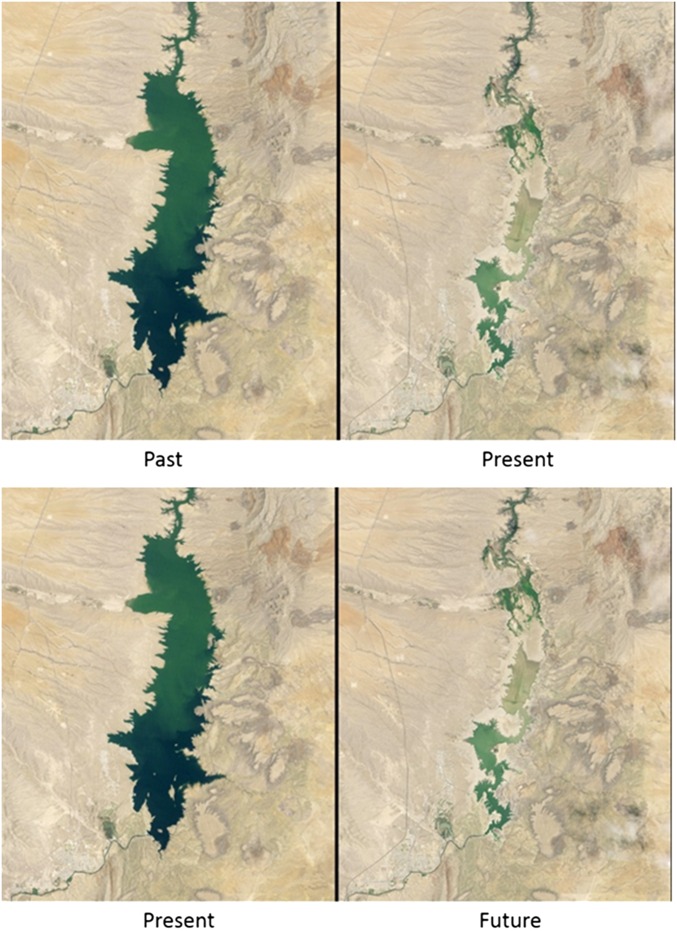

In study 3 we used a more controlled manipulation of temporal comparisons by presenting participants with 14 pairs of photographs said to demonstrate the influence of climate change on the earth. For example, one set of pictures showed a satellite image of a river basin either full of water or dried up (Fig. S1). We manipulated temporal comparisons by describing the photographs as reflecting changes in the environment from the past to the present (past-focused condition) or reflecting expected changes in the environment from the present to the future (future-focused condition). Participants then reported their proenvironmental attitudes.

Fig. S1.

Examples of stimuli from the past-focused (Upper) and future-focused (Lower) conditions in study 3, Elephant Butte Reservoir, NM. Image courtesy of NASA.

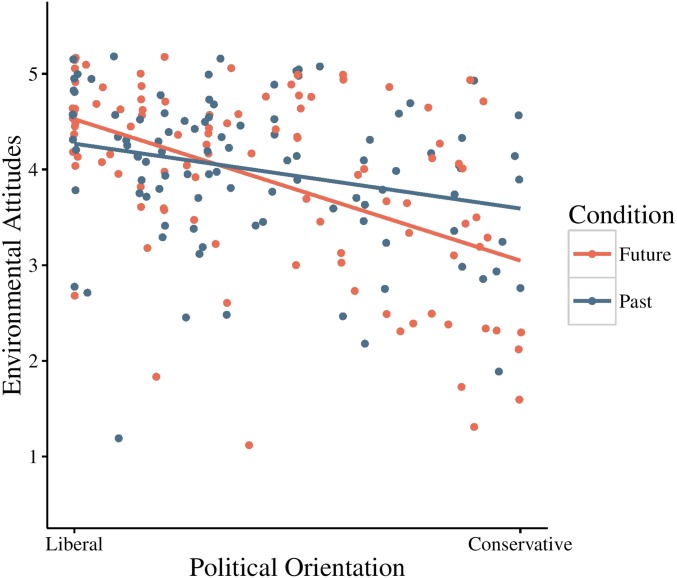

Results.

As expected, conservatives expressed less favorable attitudes in the future-focused comparison (b = −0.015, P < 0.0001), but this association was greatly attenuated in the past-focused comparison (b = −0.007, P = 0.011; interaction b = 0.008, P = 0.03) (Fig. 3). Importantly, these results remained significant when controlling for feelings of uncertainty and personal need for closure (e.g., intolerance of ambiguity) measured after the manipulation. Neither of these variables moderated the effect of condition on environmental attitudes over and above political orientation. Our findings are not likely explained by any uncertainty caused by the speculative future-focused images or an aversion to such speculation. Detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 3.

Fig. 3.

Study 3. Conservatives report more positive environmental attitudes after viewing past-focused environmental comparisons (blue line) than after viewing future-focused environmental comparisons (red line).

SI Methods and Results

The patterns of predicted results were not affected when age, race (non-White = 0, White = 1), sex (female = 0, male = 1), and income (measured in studies 3, 4b, 5, and 6) were included as covariates, so these variables are not discussed further.

Study 1.

Participants were 203 United States adults, age (mean ± SD) 31.84 ± 8.86 y, who participated for $1.00 compensation on Amazon’s MTurk. After providing consent, participants completed a demographics questionnaire including a seven-point measure of political orientation (1 = liberal, 7 = conservative; M = 3.06, SD = 1.75). Participants were predominately White (74%) and male (61%). Most participants identified as liberal (58%), 25% identified as moderate, and 17% identified as conservative.

Participants then read a proenvironmental message ostensibly written by a participant in an earlier study. Participants were shown a screen shot from the earlier study that contained some brief information about the participant as well as the proenvironmental message. Participants were randomly assigned to read a message that compared the present with the past or one that compared the present with the future. We also randomly assigned participants to read a message from a self-reported liberal or conservative. However, this factor did not qualify the interaction between temporal focus and participants’ political orientation in our primary analyses (Ps > 0.469), so it is not discussed further. In the past-focused comparison condition participants read:

Looking back to our nation’s past, I think that our society has gone too far in its desire for material wealth (among other things). It seems like life in the past was simpler and people were happy with the little that they had. There was less traffic on the road, the air was clean, and there was plenty of land. I sort of feel like we have changed the world that our forefathers lived in … would they be happy with what we’ve done to it? I want to make our founding fathers proud, and if we do not make changes to the way we treat the environment now, it will continue to get worse. I think we need to undo what we’ve done so that the world can go back to how it was supposed to be back then.

In the future comparison condition participants read:

Looking forward to our nation’s future, I think that our society has gone too far in its desire for material wealth (among other things). It seems like life in the future is getting too complex and people will never be happy with all they have. There is increasing traffic on the road, the air is becoming polluted, and land is disappearing. I sort of feel like we are changing the world that future generations will live in … will they be happy with what we are doing to it? I want to make future generations proud, and if we do not make changes to the way we treat the environment now, it will continue to get worse. I think we need to stop what we are doing so that the world can be what it’s supposed to be in the future.

Both messages expressed the need to make changes in society and hinted at an obligation to curb climate change for the sake of others (either past or future generations, depending on condition). Except for the temporal focus, the messages were identical. Thus, any effects of condition can be attributed to temporal framing and not to an aversion to change, alignment with the attitudes of a member of the participant’s own political ideology, or the obligation to protect or care for other generations of people.

Then participants indicated how much they liked the statement (e.g., “I like the statement I just read;” α = 0.94) and indicated their environmental attitudes (e.g., “We should change how we interact with the environment;” α = 0.96). Finally, participants completed a manipulation check (“What was the main temporal focus of the statement?”: 1 = mainly focused on the past, 7 = mainly focused on the future) and read a debriefing statement before closing the browser.

First we checked that our temporal comparison manipulation was effective. Indeed, the past comparison was rated as significantly more past-focused than the future comparison [mean = 3.18, SD = 1.46 vs. mean = 6.41, SD = 0.80; t(198) = 19.42; P < 0.0001]. Next we conducted separate regression analyses in which liking and attitudes were regressed on participants’ political orientation, temporal comparison condition (coded 0 = future; 1 = past), and the political orientation × condition interaction. With regard to liking, the political orientation × condition interaction was significant [b = 0.42, SE = 0.11, t(199) = 3.71, P < 0.001] (Fig. 1A). We probed this interaction by exploring the simple slope of political orientation on liking within each temporal comparison condition. The more conservative the participants were, the less positively they rated the future-focused message [b = −0.24, SE = 0.08, t(199) = 3.01, P = 0.003], whereas the opposite was true for the past-focused message [b = 0.19, SE = 0.08, t(199) = 2.25, P = 0.03]. We also examined temporal comparison effects as a function of political orientation by obtaining Johnson–Neyman values, which identify the level(s) of political orientation at which the effect of condition on liking becomes significant at P = 0.05. [The Johnson–Neyman technique, or the regions of significance approach, seeks the values of the moderator variable for which the slope of X on Y is significant. The result of this technique is a range of moderator values in which the simple slope is significantly different from zero (34).] The temporal comparison effect was significant and negative for participants scoring at 3.78 (neutral) or lower (liberal) on the political orientation scale, suggesting that liberals expressed less favorable attitudes about the past-focused (vs. the future-focused) message.

With regard to proenvironmental attitudes, the political orientation × condition interaction was significant [b = 0.19, SE = 0.08, t(199) = 2.25, P = 0.03] (Fig. 1B). Once again, we probed this interaction by exploring the simple slopes of political orientation on attitudes within each temporal comparison condition. Conservatives expressed less favorable attitudes than liberals in the future-focused condition [b = −0.35, SE = 0.06, t(199) = 6.01, P < 0.0001] and also in the past-focused condition, but the effect in the latter was almost half as large [b = −0.16, SE = 0.06, t(199) = 2.64, P = 0.009]. We also examined Johnson–Neyman values for the effect of condition on attitudes. The effect of temporal comparison was significant and positive for participants scoring 3.62 (neutral) or higher (conservative) on the political orientation scale, suggesting that conservatives expressed higher proenvironmental attitudes in the past-focused condition.

Study 2.

In study 2, we treated political orientation as a dichotomous between-subjects variable and recruited participants who previously had identified as liberal or conservative. A total of 153 liberals and 109 conservatives were recruited; 10 participants indicated that they were politically moderate and therefore were excluded from the final dataset. Thus, participants were 262 United States adults, age (mean ±SD) 37.63 ± 11.56 y, who participated for $1.00 compensation on MTurk. Participants were predominately White (86%) and female (57%). After providing consent, participants were randomly assigned to a past-focused, future-focused, or nonenvironmental control condition. The past- and future-focused conditions were identical to those in study 1, except that the words “forefathers” and “founding fathers” used in the past-focused message from study 1 were replaced with “those before us” and “ancestors,” respectively. In the control condition, participants read:

One issue in the world today is ISIS (among other things). It seems like there is not a lot that we can do about this threat. Maybe the answer is war, or teaching people over there how to fight, or maybe we shouldn’t be involved at all. I sort of feel like America hasn’t figured out what to do yet … will we be able to work with other nations to stop ISIS? I’m not sure I want America to get involved, but if we don’t do something, the world could change forever. I am not saying anything against a certain religion or type of person. We need to figure out how to stop the threat without causing harm to the people in the Middle East and around the world who do not subscribe to the terrorist’s version of religion.

Then participants indicated their environmental attitudes using the scale in study 1 (α = 0.96) and completed a demographics questionnaire. Finally, participants read a debriefing statement before closing their browser.

We conducted a two-way ANOVA with political orientation (liberal vs. conservative) and condition (control vs. future-focused vs. past-focused) as between-subjects variables and environmental attitudes as the dependent variable. A main effect of political orientation emerged such that conservatives expressed less favorable attitudes than liberals [mean = 4.90, SD = 1.70 vs. mean = 6.59, SD = 0.61, F(1, 256) = 129.92, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.34]. The main effect of condition was not statistically significant (P = 0.16).

Although the overall interaction did not reach conventional levels of significance [F(2, 256) = 2.38, P = 0.09, η2 = 0.02] (Fig. 2), the expected pattern of effects emerged. A main effect of condition was significant for conservatives [F(2, 256) = 3.65, P = 0.03, η2 = 0.03], such that they expressed more favorable attitudes in the past-focused condition than in the control condition (mean = 5.26, SD = 1.58 vs. mean = 4.52, SD = 1.78, P = 0.007, d = 0.44) or in the future-focused condition, although this simple effect did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.21). Conservatives’ attitudes were more favorable in the future-focused condition than in the control condition, but this simple effect also was not significant (P = 0.14). The linear effect of condition from the control condition to the past-focused condition (1 = control, 2 = future-focused, 3 = past-focused) was significant for conservatives [b = 0.37, SE = 0.14, t(258) = 2.71, P = 0.007]. Liberals’ attitudes did not differ across conditions (P = 0.97).

Comparing liberals and conservatives within the framing conditions revealed that, although conservatives expressed less favorable attitudes in all three conditions, the effect became increasingly smaller from the control condition (mean difference = −2.07, SE = 0.26, P < 0.001, d = 1.66) to the future-focused (mean difference = −1.69, SE = 0.26, P < 0.001, d = 1.44) and past-focused conditions (mean difference = −1.29, SE = 0.26, P < 0.001, d = 1.16).

Inspection of standardized residuals obtained from the ANOVA revealed that data from one participant was extreme (standardized residual = −3.61). This participant was a highly identified conservative in the past-focused condition who expressed very low proenvironmental attitudes (z = −3.38). The participant did not spend much time reading the manipulation (20 s) and therefore may not have been exposed to the crux of the past-focused message that appeared at the very end (“I think we need to undo what we’ve done so that the world can go back to how it was supposed to be back then”). After excluding this single participant, the condition × political identification interaction became statistically significant [F(2, 255) = 3.32, P = 0.04, η2 = 0.03]. The primary pattern of simple effects remained the same, although environmental attitudes became slightly more positive for conservatives in the past-focused condition. Thus, simple effects including the past-focused condition increased in magnitude and therefore offered even stronger support for our hypotheses.

Study 3.

Participants were recruited on Mturk. To recruit approximately equal numbers of liberals (or Democrats) and conservatives (or Republicans), we targeted participants based on self-identified political preference. The final sample was 200 United States adults, age (mean ± SD) 34.23 ± 0.22 y, who participated for $1.00 compensation. After providing consent, participants completed a demographics questionnaire in which they indicated their political orientation on a sliding scale (0 = extremely liberal; 100 = extremely conservative). Participants were predominately White (82%) and male (56%). Sixty percent of the sample self-identified as liberal; 5% of participants indicated that they were moderate, and the remaining 35% were conservative (mean = 41.23, SD = 31.29).

Participants then were told that they would be rating pairs of images demonstrating the effects of climate change on the earth (14 total). In the past-focused condition, participants were shown images described as showing how the present has changed from the past, whereas in the future-focused condition they were shown the same images described as showing how the present is likely to change in the future (Fig. S1). After viewing all 14 images, participants indicated how uncertain (e.g., unsure, restless) they felt using a 19-item scale (1 = not at all, 5 = a great deal; α = 0.96) (35), reported their environmental attitudes using the eight-item New Ecological Paradigm scale (e.g., “Humans are seriously abusing the environment;” α = 0.90) (36), and completed the 15-item Need for Closure Scale (e.g., “I dislike unpredictable situations;” α = 0.90) (37).

Primary analyses.

We conducted a regression analysis in which participants’ environmental attitudes were regressed on political orientation, temporal comparison condition (0 = future-focused, 1 = past-focused), and the political orientation × condition interaction. The political orientation × condition interaction was significant [b = 0.008, SE = 0.004, t(196) = 2.22, P = 0.03] (Fig. 3). Conservatives expressed less favorable attitudes in both the future-focused condition [b = −0.015, SE = 0.003, t(196) = 6.02, P < 0.0001] and the past-focused condition, but the effect in the latter was approximately half as large [b = −0.007, SE = 0.003, t(196) = 2.57, P = 0.01]. Using the Johnson–Neyman technique, we found that the effect of temporal comparison was significant and positive for the more conservative participants scoring above 69.25 on the political orientation scale, suggesting that conservatives expressed more favorable environmental attitudes in the past-focused than in the future-focused condition.

Supplementary analyses.

To rule out alternative explanations for these findings, we also examined whether feelings of uncertainty differed across conditions or varied as a function of condition and political orientation. The political orientation × condition interaction on perceived uncertainty was marginally significant [b = 0.006, SE = 0.003, t(196) = 1.76, P = 0.08], with liberals feeling less uncertain in the future-focused condition [b = −0.16, SE = 0.15, t(196) = 1.09, P = 0.28] and conservatives feeling more uncertain in the future-focused condition [b = 0.21, SE = 0.15, t(196) = 1.40, P = 0.16]. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, given that the simple effects were not statistically significant. Importantly, uncertainty was not associated with environmental attitudes (r = −0.07, P = 0.34), and controlling for uncertainty in the primary analyses did not influence the results. Additionally, when including political orientation and uncertainty moderator variables in the primary analyses, the uncertainty × condition interaction was not significant (P = 0.47), but the political orientation × condition interaction was (P = 0.02).

We conducted the same analyses with need for closure as the dependent variable. The political orientation × condition interaction was not significant (P = 0.38). Although conservatism was associated with higher need for closure (r = 0.27, P < 0.001), need for closure was not associated with environmental attitudes (r = −0.04, P = 0.56), so controlling for this variable had no affect on the pattern of results. Additionally, when including political orientation and need for closure as moderator variables in the primary analyses, the need for closure × condition interaction was not significant (P = 0.97), but the political orientation × condition interaction was (P = 0.04). Taken together, these analyses suggest that our findings cannot be explained by general feelings of uncertainty or chronic need for closure and that political orientation specifically drives the effects.

Study 4a.

We conducted an internet search for environmental organizations and charities and created an initial list of 56 websites. We retained a total of 46 websites after excluding organizations that did not have a clear connection to climate change. We recruited 237 United States adults, age (mean ± SD) 35.16 ± 9.36 y, on MTurk to rate the organizations. Participants were predominately White (77%) and male (65%) and completed the study for $2 compensation. After providing consent and completing a demographics questionnaire, including a measure of political orientation (0 = extremely liberal; 100 = extremely conservative; mean = 39.82, SD = 27.35), participants were told they would rate five different environmental organizations. We asked participants to provide their “first impressions of these organizations based on a quick scan of the webpage” and to focus specifically on whether the organization is past- or future-focused. Before rating the organizations, participants were given a brief description of a past-focused organization (“A past focused organization might make more references to the past, restoring the planet, conserving the original state of the Earth, or might suggest that we get back to how things used to be”) and a future-focused organization (“A future focused organization might make more mention of the future, would be more focused on creating a new kind of lifestyle, and might suggest a path to achieve certain goals for the future”).

Participants then were presented with links to five websites at random from the list of 46. Each link appeared on a separate page, and participants were instructed to click the link and spend a few minutes browsing the website before rating the temporal focus of the organization (1 = very past-focused; 7 = very future-focused). After completing their ratings, they read a debriefing statement. We transposed the data into a long format by aggregating participants’ data within each organization. Doing so allowed us to conduct analyses at the level of the organizations (vs. participants). Average ratings for each organization were computed with data from 18–27 participants. A one-sample t test was conducted to test whether on average the organizations were rated as more past- or future-focused (i.e., average rating ≠ 4). Overall, the organizations were rated as significantly more future-focused [mean = 5.00, SD = 0.78), t(45) = 8.67, P < 0.0001, d = 2.58].

Study 4b.

As in study 3, we targeted participants based on self-identified political preference. Four participants indicated that they were politically moderate and therefore were excluded from analyses. Thus, the final sample comprised of 159 United States adults, age (mean ± SD) 34.91 ± 0.37 y, who participated on MTurk for $1 compensation. Participants were predominately White (82%) and male (66%). The sample was approximately equal with regard to political orientation (liberal = 55%, conservative = 45%; mean = 39.82, SD = 27.35). After providing consent and completing a demographics questionnaire, participants were told that they were being offered an extra $2 to make a donation of their choosing to two environmental charities.

Participants then were presented with a link to the two most past- and future-focused charities from study 4. Links were presented on separate pages, and participants were instructed to learn about each organization before rating the temporal focus of the organization (1 = very past focused; 7 = very future focused). Next, participants were asked to indicate how much they would like to donate to each group by typing a value between 0 and 2 in a text box which appeared next to the organization’s logo. They also could choose to keep money for themselves by typing that amount into a third text box. The page kept a running total, which had to equal $2 before participants could continue. Finally, participants read a debriefing statement.

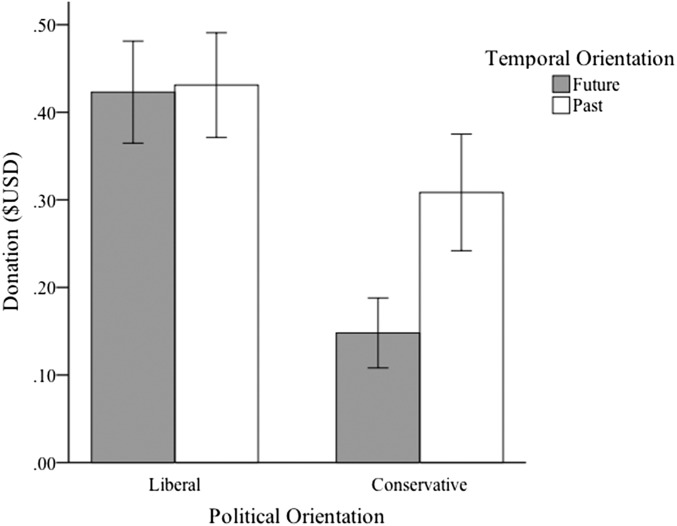

The past-focused charity was rated as more past-focused (or less future-focused) than the future-focused charity [mean = 4.66, SD = 1.65 vs. mean = 5.53, SD = 1.14, F(1, 157) = 38.74, P < 0.0001], confirming that the two charities could be differentiated on this temporal dimension. Fewer than half of the participants donated money (43%, χ2 = 2.77, P = 0.10), and more liberals than conservatives donated (67 vs. 33%, χ2 = 7.67, P = 0.006). Nevertheless, a repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that conservatives gave more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.31, SD = 0.57 vs. mean = 0.15, SD = 0.34, P = 0.03, d = 0.31), whereas liberals gave equally to each charity (P = 0.90) (Fig. 4). Conservatives gave less than liberals to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.42, SD = 0.54 vs. mean = 0.15, SD = 0.34, P < 0.001, d = 0.60) but did not differ significantly from liberals in giving to the past-focused charity (P = 0.17). The temporal focus × political ideology interaction was F(1, 157) = 2.51, P = 0.12, η2 = 0.02.

Fig. 4.

Study 4b. Conservatives donate more to the past-focused charity than the future-focused charity, while this is not the case for liberals. Error bars represent SEs.

Study 5.

As in previous studies, study 5 targeted participants based on self-identified political preference. Four participants who indicated that they were politically moderate and one who did not indicate a political orientation were excluded from analyses. Thus, the final sample comprised of 401 United States adults, age (mean ± SD) 34.74 ± 10.33 y, who participated on MTurk for $1 compensation. Participants were predominately White (82%) and split equally between males and females. The sample was approximately equal with regard to political orientation (liberal = 53%, conservative = 47%; mean = 46.28, SD = 32.70). After providing consent and completing a demographics questionnaire, participants were told that they were being offered an extra $2 to make a donation of their choosing to an environmental charity. They then were presented with a link to the past- or future-focused charity from study 5 or to a cancer research charity. After spending some time learning about the charity, participants indicated how much of the $2 they would like to donate by typing a number into a text box. Finally, participants read a debriefing statement.

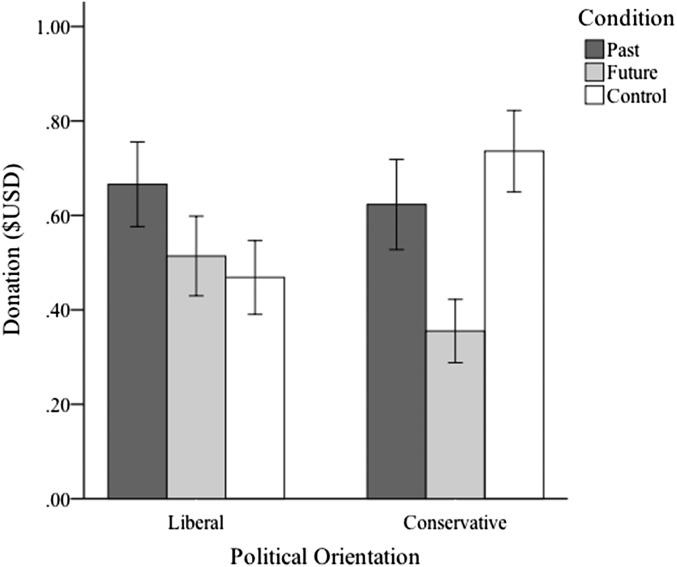

A two-way ANOVA testing the effects of political orientation and charity on donations revealed a main effect of charity [F(2, 395) = 3.44, P = 0.03, η2 = 0.02]. Donations to the past-focused charity were higher than donations to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.63, SD = 0.74 vs. mean = 0.43, SD = 0.63, P = 0.05, d = 0.29). Donations to the cancer research charity were marginally higher than donations to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.61, SD = 0.70 vs. mean = 0.43, SD = 0.63, P = 0.08, d = 0.27). Donations did not differ between the past-focused and cancer research charities (P = 0.97).

This main effect was qualified by a significant political orientation × charity interaction [F(2, 395) = 3.40, P = 0.03, η2 = 0.02] (Fig. S2). Conservatives gave more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.62, SD = 0.79 vs. mean = 0.36, SD = 0.59, P = 0.03, d = 0.38). Conservatives also gave more to the cancer research charity than to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.75, SD = 0.72 vs. mean = 0.36, SD = 0.59, P = 0.03, d = 0.60).

Fig. S2.

Liberals donate equally to the past-focused, future-focused, and cancer research (Control) charities, whereas conservatives donate equally to the past-focused and cancer research charities and donate less to the future-focused charity. Error bars represent SEs.

Conservatives did not differ in their donations to the past-focused and cancer research charities (P = 0.34). Liberals’ donations to each of the charities did not differ significantly (past-focused vs. future-focused, P = 0.20; past-focused vs. cancer, P = 0.10; future-focused vs. cancer, P = 0.70). Conservatives gave more than liberals to the cancer research charity (mean = 0.75, SD = 0.72 vs. mean = 0.48, SD = 0.65, P = 0.02, d = 0.40). Conservatives gave less than liberals to the future-focused charity, although this difference failed to reach significance (mean = 0.36, SD = 0.59 vs. mean = 0.51, SD = 0.67, P = 0.18, d = 0.40). Importantly, conservatives and liberals did not differ in their donations to the past-focused charity (P = 0.72).

Study 6.

Participants were 201 adults recruited on MTurk for $1 compensation. Seven participants indicated that they were politically moderate and therefore were excluded from analyses. Thus, the final sample was 194 adults, age (mean ± SD) 37.77 ± 12.17 y, who were predominately White (84%) and male (58%). The sample was approximately equal with regard to political orientation (55% liberal, 45% conservative; mean = 3.70, SD = 2.07). After providing consent, participants were told that they would be helping determine how $0.50 would be donated to two nonprofit environmental groups that were working to become charities. Participants were told that their input was to ensure that a democratic process with actual citizens determined how the money was donated. Then participants were shown two ostensible charities, one that communicated a past-focused mission and the other that communicated a future-focused mission (Fig. S3). We counterbalanced the names and temporal focus of the charities to ensure that each was equally likely to be past- or future-focused. Next to each charity was a text box in which participants could indicate their donation preference. Participants could not continue until the boxes totaled $0.50.

Fig. S3.

Future-focused (Upper) and past-focused (Lower) environmental charities from study 6.

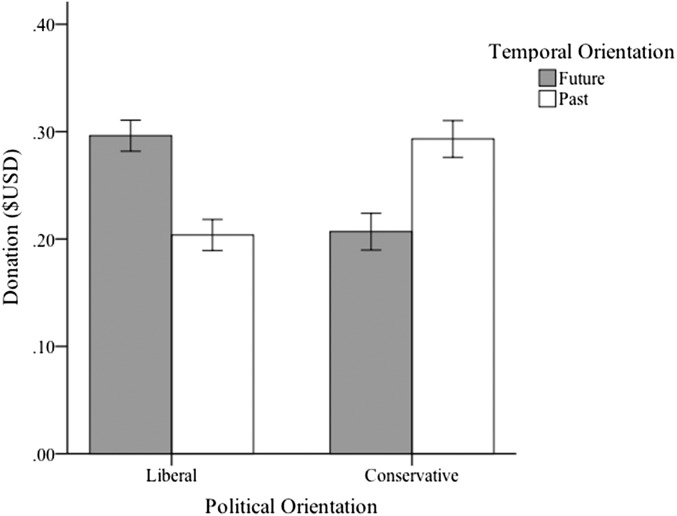

The counterbalancing order did not moderate the effects of political orientation and temporal focus on donations (P = 0.85), so this factor is not discussed further. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant political orientation × temporal focus interaction on donations [F(1, 192) = 16.13, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.08]. Conservatives donated more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (mean = 0.29, SD = 0.16 vs. mean = 0.21, SD = 0.16, P = 0.009, d = 0.27). Conversely, liberals donated more to the future-focused charity than to the past-focused charity (mean = 0.30, SD = 0.15 vs. mean = 0.20, SD = 0.15, P = 0.002, d = 0.31). Conservatives donated more than liberals to the past-focused charity (mean = 0.29, SD = 0.15 vs. mean = 0.20, SD = 0.16, P < 0.0001, d = 0.58). Conversely, liberals donated more than conservatives to the future-focused charity compared (mean = 0.30, SD = 0.15 vs. mean = 0.21, SD = 0.16, P < 0.0001, d = 0.58).

Study 7: Meta-Analysis.

Effect sizes reflecting the association between political orientation and proenvironmental outcomes were coded to indicate the framing condition from which they came (0 = future-focused or control, 1 = past-focused). All effects were computed as Cohen’s d, defined as the standardized difference between two means, and were calculated from means and SDs or from t and P values. In study 1 we averaged the effect sizes for liking and proenvironmental attitudes to create a single effect size (38). Analyses were carried out using the Metafor package for R (39) and followed conventional methods (38, 40).

First, we tested a random-effects model of the effect of political orientation on proenvironmental outcomes collapsing across condition (model 1). Next we included a temporal comparison dummy code as a modifier of the effect sizes in a mixed-effects meta-regression model (model 2). [Much like linear regression, a meta-regression tests whether the observed effect sizes are a function of one or more explanatory variables called “effect modifiers” (38). The analysis tests whether these variables can explain any heterogeneity of effects between studies. In a random effects model, as is used here, residual variance not explained by the effect modifier is accounted for as well.] We expected a significant degree of variability in effect sizes in model 1 because of differing effect sizes across comparison conditions. Thus, we expected that the model including condition as a modifier of effect sizes (model 2) would fit the data better than the model without the modifier (model 1). A nested model comparison was conducted to test this hypothesis.

The estimated average effect size across all of the studies was negative [d = −0.54, SE = 0.17, P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.85, −0.23], indicating that conservatives tended to display lower proenvironmental outcomes. However, there was significant variability in individual effect sizes [Q (df = 12) = 126.18, P < 0.0001], and so we proceeded to test whether the temporal comparison condition could account for this variability. Supporting predictions, temporal comparison was a significant modifier of the effect sizes (β = 0.64, SE = 0.26, z = 2.47, P = 0.01, 95% CI = 0.13, 1.15) and accounted for a significant portion of the variance in effect sizes over model 1 [37.11%; likelihood ratio test (df = 1) = 4.96, P = 0.03]. The overall effect of political orientation was significantly negative in the future-focused/control conditions (d = −0.82, SE = 0.17, z = 4.96, P < 0.0001, 95% CI = −1.15, −0.50), whereas the overall effect was smaller and nonsignificant in the past-focused condition (d = −0.19, SE = 0.20, z = 0.94, P = 0.35, 95% CI = −0.58, 0.21). Thus, the past-focused framing bridged 77% of the political divide in proenvironmental outcomes that was prevalent in the future-focused/control conditions. [A P-curve analysis (41) indicated the presence of evidential value in our significant interaction effects (z = −4.44, P < 0.0001), which was not determined to be inadequate (z = 2.69, P = 1). The estimated power to detect the included interaction effects was 90% (95% CI = 62%, 98%).

Proenvironmental Behaviors

Study 4a.

Method.

Study 4a was a pilot test that aimed to determine whether real environmental charities tend to make past- or future-focused comparisons, on average. Based on these data, we also aimed to use some of the charities as stimuli in subsequent studies. We collected links to websites for 46 existing environmental charities and asked participants to rate the extent to which a random set of five charities were past- or future-focused.

Results.

Overall, the environmental charities were rated as significantly future-focused (P < 0.0001, d = 2.58), underscoring our general claim that conservatives’ lack of support for action addressing climate change could be caused by real-world trends in the temporal framing of the appeals to address climate change. Detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 4a.

Study 4b.

Method.

In study 4b we used two charities from study 4a as stimuli to demonstrate that temporal focus can influence liberals’ and conservatives’ donation behaviors. Participants were offered $2 windfall money and were provided with links to the most past-focused and most future-focused charities from study 4a. They were asked to visit the two websites and decide how much of the money to donate to those charities and how much to keep for themselves.

Results.

As expected, conservatives gave less than liberals to the future-focused charity (P = 0.0002, d = 0.60) (Fig. 4). However, this difference was attenuated and was not statistically significant for the past-focused charity (P = 0.17). Moreover, conservatives gave more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (P = 0.03, d = 0.31) whereas liberals gave equally to each charity [P = 0.90; interaction F(1, 157) = 2.51, P = 0.12]; detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 4b).

Study 5.

Method.

The aim of study 5 was to isolate further the effects of temporal comparisons on donation behavior by using the procedure in study 5 but randomly presenting participants with only one website, either the past-focused charity or the future-focused charity from study 4b or a nonenvironmental control charity (cancer research). Participants were given $2 windfall money and were asked to donate as much or as little to the charity as they chose, while keeping the rest for themselves.

Results.

When comparing donations among conservatives and liberals separately, we found that conservatives gave more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (P = 0.03, d = 0.38) and more to the cancer research charity than to the future-focused charity (P = 0.03, d = 0.60) (Fig. S2). Conservatives did not differ in their donations to the past-focused and cancer research charities (P = 0.34). Liberals’ donations to each of the three charities did not differ significantly (past- vs. future-focused, P = 0.20; past-focused vs. cancer, P = 0.10; future-focused vs. cancer, P = 0.70).

When comparing conservatives and liberals within each charity condition, we found that conservatives donated more than liberals to the cancer charity (P = 0.02, d = 0.40) but less than liberals to the future-focused charity (P = 0.18, d = 0.40), although this effect did not reach conventional levels of significance. Conservatives and liberals donated equally to the past-focused charity [P = 0.72; interaction F(2, 395) = 3.40, P = 0.03]. Detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 5.

Study 6.

Method.

To increase experimental control and overcome the issue that the charities used in studies 4b and 5 inevitably differed in ways other than their temporal focus, we created two ostensible charities in study 6 and experimentally manipulated the temporal comparison. One charity communicated a past comparison (“Restoring the planet to its original state”), and the other communicated a future comparison (“Creating a new earth for the future”) (Fig. S3). Participants were shown the logos and mission statements of each charity and then were asked to allocate $0.50 to the charities.

Results.

When comparing monetary allocations among conservatives and liberals separately, we found that conservatives distributed more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity (P = 0.009, d = 0.27). Conversely, liberals distributed more to the future-focused charity than to the past-focused charity (P = 0.002, d = 0.31). When comparing conservatives and liberals’ allocation tendencies, we found that conservatives distributed more than liberals to the past-focused charity (P < 0.0001, d = 0.58). Conversely, liberals distributed more than conservatives to the future-focused charity [P < 0.0001, d = 0.58; interaction F(1, 192) = 16.13, P < 0.0001] (Fig. 5). Detailed methods and results can be found in SI Methods and Results, Study 6.

Fig. 5.

Study 6. Conservatives donate more to the past-focused charity than to the future-focused charity, while the opposite is the case for liberals. Error bars represent SEs.

Study 7: Meta-Analysis.

We were interested in quantifying the size of the effect of political orientation on proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors as a function of temporal comparison across our studies. To this end, we submitted effect sizes from all studies (with the exception of 4a) to a mixed-effects meta-analysis. Although conservatives were less proenvironmental than liberals overall (d = −0.54, P < 0.001), this difference was modified by temporal comparison (β = 0.64, P = 0.01). Conservatives were less proenvironmental than liberals in the future-focused and control conditions (d = −0.82, P < 0.0001), but this difference was attenuated and was no longer statistically significant in the past-focused conditions (d = −0.19, P = 0.35). Past comparisons largely bridged the political divide in addressing global warming and climate change observed in the future-focused and control conditions.

Discussion

Conservative ideology emerged from a resistance to progressive change, and thus a central feature of conservatives’ psychology is a preference for the past over the future. On this basis, we predicted and found that past-focused environmental comparisons are more effective in convincing conservatives of the need to act against climate change. In fact, the meta-analysis showed that past comparisons bridged the political gap in our studies by 77% on average. In some cases, the political divide was even reversed—conservatives liked past-focused environmental appeals more than liberals did (study 1) and allocated more money than liberals to past-focused environmental charities (study 6). One limitation of this research is that we relied on relatively small samples drawn from Amazon MTurk. We welcome research to replicate these findings in a large-scale, nationally representative sample. Doing so also would be helpful in determining how large an impact a temporal-framing intervention could have in a naturalistic setting.

Our findings align with a strong tradition in social psychology and social cognition demonstrating the influence of framing on attitudes. Even subtle differences in framing can mean the difference between acceptance and rejection of a message (28). Messages that are supported by scientific evidence are especially effective when acceptance of the message also means that one’s personal values can be upheld (29, 30). Messages concerning global warming and climate change are no exception: They need to be tailored with great care (31–33). Indeed, over the last several years the message of climate change has been framed in many ways—from fatalistic predictions about the future to calls for social progress (33). However, our research suggests that these messages will not be as effective in bridging the political divide if they continue to make future-focused comparisons. Paradoxically, it is the past that may be critical in saving the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Social Cognition Center Cologne and in particular the Mussweiler laboratory for feedback on this research. This research was funded by a Junior Start-Up Grant awarded by the Center for Social and Economic Behavior, University of Cologne.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1610834113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anderegg WR, Prall JW, Harold J, Schneider SH. Expert credibility in climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(27):12107–12109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Liere KD, Dunlap RE. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public Opin Q. 1980;44(2):181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCright AM, Dunlap RE. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Public Opin Q. 2011;52(2):155–194. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fielding KS, Head BW, Laffan W, Western M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Australian politicians’ beliefs about climate change: Political partisanship and political ideology. Env Polit. 2012;21(5):712–733. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gromet DM, Kunreuther H, Larrick RP. Political ideology affects energy-efficiency attitudes and choices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(23):9314–9319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218453110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huntington S. Conservatism as an ideology. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1957;51(2):454–473. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirk R. The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot. Regnery Publishing; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke E. Reflections on the Revolution in France. James Dodsley; London: 1790. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller JZ. Conservatism: An Anthology of Social and Political Thought from David Hume to the Present. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jost JT, Glaser J, Kruglanski AW, Sulloway FJ. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(3):339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson MD, Cassidy DM, Boyd RL, Fetterman AK. The politics of time: Conservatives differentially reference the past and liberals differentially reference the future. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2015;45(7):391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern BB. Historical and personal nostalgia in advertising text: The fin de siecle effect. J Advert. 1992;21(4):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson JL. Nostalgia: Sanctuary of Meaning. Bucknell Univ Press; Lewisburg, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pew Research Center 2016 Campaign exposes fissures over issues, values and how life has changed in the U.S. Available at www.people-press.org/2016/03/31/campaign-exposes-fissures-over-issues-values-and-how-life-has-changed-in-the-u-s/. Accessed November 21, 2016.

- 15. Gallup J 2015, Majority say moral values getting worse. Available at www.gallup.com/poll/183467/majority-say-moral-values-getting-worse.aspx. Accessed November 21, 2016.

- 16. United Nations (2011) Press Release: Secretary-General Urges Governments to Take Long-term View on Renewable Energy, Spelling Out Priorities at ‘Clean Industrial Revolution’ Event in Durban. Available at https://www.un.org/press/en/2011/sgsm13998.doc.htm. Accessed May 4, 2016.

- 17.Guggenheim D. 2006. An inconvenient truth: A global warning [DVD]. (Paramount, Hollywood, CA)

- 18.Gauchat G. Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(2):167–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolsko C, Ariceaga H, Seiden J. Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2016;65:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinberg M, Willer R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(1):56–62. doi: 10.1177/0956797612449177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell TH, Kay AC. Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;107(5):809–824. doi: 10.1037/a0037963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahan DM, Jenkins‐Smith H, Braman D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J Risk Res. 2011;14(2):147–174. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clifford S, Jewell RM, Waggoner PD. Are samples drawn from Mechanical Turk valid for research on political ideology? Research & Politics. 2015;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huff C, Tingley D. “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research & Politics. 2015;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit Anal. 2012;20:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandler J, Paolacci G, Peer E, Mueller P, Ratliff KA. Using nonnaive participants can reduce effect sizes. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(7):1131–1139. doi: 10.1177/0956797615585115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen GL, Aronson J, Steele CM. When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2000;26(9):1151–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakoff G. Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. Univ of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowson J. December 2013 A new agenda on climate change. J R Soc Arts. Available at https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/a-new-agenda-on-climate-change. Accessed November 21 2016.

- 32.Schuldt JP, Konrath SH, Schwarz N. “Global warming” or “climate change”? Whether the planet is warming depends on question wording. Public Opin Q. 2011;75:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisbet MC. Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Env: Sci and Pol for Sus Dev. 2009;51(2):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGregor I, Zanna MP, Holmes JG, Spencer SJ. Compensatory conviction in the face of personal uncertainty: going to extremes and being oneself. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(3):472–488. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunlap RE, Van Liere KD, Mertig AG, Jones RE. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J Soc Issues. 2000;56(3):425–442. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roets A, Van Hiel A. Item selection and validation of a brief, 15-item version of the need for closure scale. Per and Ind Diff. 2011;50(1):90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simonsohn U, Nelson LD, Simmons JP. P-curve: A key to the file-drawer. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(2):534–547. doi: 10.1037/a0033242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]