Significance

Current histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have shown mixed results in the treatment of many cancer types. Our study has demonstrated significant antitumor phenotypes resulting from targeted disruption of HDAC3 and the NCOR complex with genome engineering technology. Our findings provide compelling evidence that the HDACs and their essential interacting factors remain key cancer therapeutic targets and that the next generation of selective HDAC inhibitors may improve survival of cancer patients.

Keywords: histone deacetylase, HDAC3, NCOR, rhabdomyosarcoma, CRISPR

Abstract

Dysregulated gene expression resulting from abnormal epigenetic alterations including histone acetylation and deacetylation has been demonstrated to play an important role in driving tumor growth and progression. However, the mechanisms by which specific histone deacetylases (HDACs) regulate differentiation in solid tumors remains unclear. Using pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) as a paradigm to elucidate the mechanism blocking differentiation in solid tumors, we identified HDAC3 as a major suppressor of myogenic differentiation from a high-efficiency Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based phenotypic screen of class I and II HDAC genes. Detailed characterization of the HDAC3-knockout phenotype in vitro and in vivo using a tamoxifen-inducible CRISPR targeting strategy demonstrated that HDAC3 deacetylase activity and the formation of a functional complex with nuclear receptor corepressors (NCORs) were critical in restricting differentiation in RMS. The NCOR/HDAC3 complex specifically functions by blocking myoblast determination protein 1 (MYOD1)-mediated activation of myogenic differentiation. Interestingly, there was also a transient up-regulation of growth-promoting genes upon initial HDAC3 targeting, revealing a unique cancer-specific response to the forced transition from a neoplastic state to terminal differentiation. Our study applied modifications of CRISPR/CRISPR-associated endonuclease 9 (Cas9) technology to interrogate the function of essential cancer genes and pathways and has provided insights into cancer cell adaptation in response to altered differentiation status. Because current pan-HDAC inhibitors have shown disappointing results in clinical trials of solid tumors, therapeutic targets specific to HDAC3 function represent a promising option for differentiation therapy in malignant tumors with dysregulated HDAC3 activity.

Abnormal epigenetic alterations play an important role in driving tumor growth and progression (1, 2). Histone deacetylases (HDACs), which are major epigenetic modifiers, are dysregulated in a significant subset of cancers (3, 4). Although pan-HDAC inhibitors have elicited promising therapeutic responses in some hematologic malignancies (1, 2, 5), limited therapeutic benefits have been reported in clinical trials for most solid tumors, including sarcomas (6). The inefficacy of HDAC inhibitors in solid tumors most likely results in part from their broad and unknown substrate range and their pleiotropic effects. Despite these early clinical failures, HDACs remain prominent therapeutic targets in cancers because of their ability to reprogram gene-expression networks. Improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying specific HDAC function will lead to more effective drug and therapy designs.

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), which consists of two major subtypes, embryonal (ERMS) and alveolar (ARMS), is the most common pediatric soft tissue malignancy. Although the two major subtypes are driven by distinct genetic alterations, both are characterized by a block in the myogenic differentiation program (7, 8). We have previously shown that treatment of RMS cells with HDAC inhibitors results in the suppression of tumor growth through the induction of myogenic differentiation (9). However, the mechanism by which aberrant activity of specific HDAC(s) represses differentiation and contributes to the malignant transformation of RMS remains unclear.

Although recent advances in Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated endonuclease 9 (Cas9) genome-editing technology have facilitated the identification of essential tumor genes, detailed phenotypic and functional characterization of essential cancer genes with the current technology is limited by the inability to expand mutant tumor clones harboring essential gene mutations and by poor CRISPR targeting efficiency in pooled cells. In this study, we used modifications of CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing technology, including high-efficiency phenotypic screens and inducible gene targeting, to interrogate the functions of essential cancer genes. These genomic tools were used to identify the underlying HDAC-mediated epigenetic mechanisms blocking differentiation of RMS tumor cells, which are essential for tumor progression.

Results

CRISPR-Mediated Knockout of HDAC3 Induces Myogenic Differentiation in RMS.

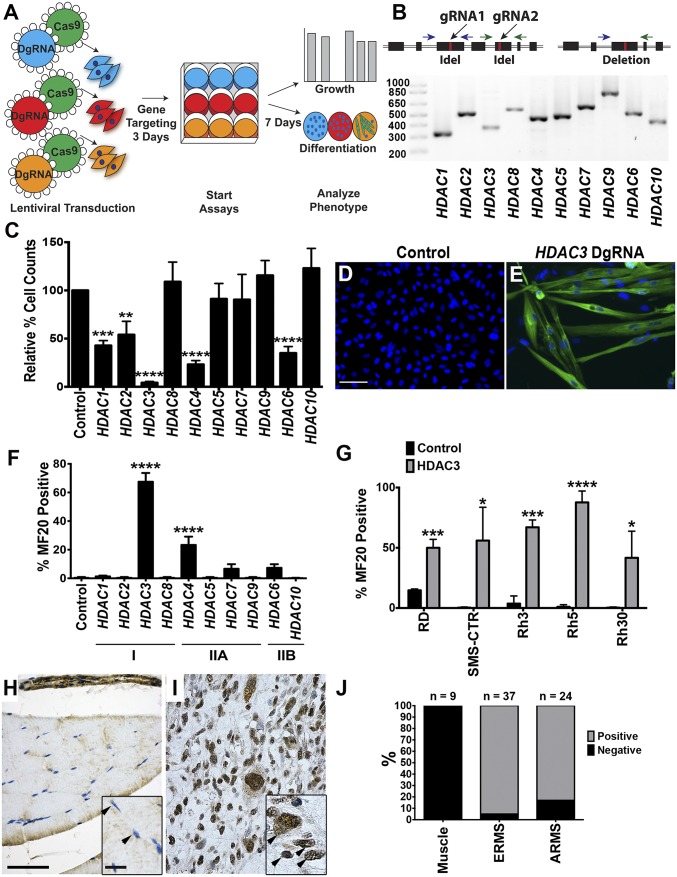

To characterize the role of specific HDACs in regulating RMS tumor growth, we performed a CRISPR/Cas9-based phenotypic screen of class I and class II HDAC genes using human 381T ERMS cells (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A). In contrast to single guide RNA (gRNA) CRISPR screens, the lentiviral phenotypic screen used dual gRNAs (DgRNA) targeted to each HDAC gene to increase overall targeting efficiency to 50–80% (Fig. 1B and Table S1). This strategy enabled direct analysis of phenotypic effects of pooled tumor cells without the need for stable selection or isolation of mutant clones.

Fig. 1.

CRISPR-based phenotypic screen of class I and II HDAC genes. (A) Schematics of the CRISPR phenotypic screen. (B, Upper) Depiction of the PCR-based method for detecting genomic DNA deletions between gRNAs as indicated by black arrows. Blue and green arrows represent primer pairs spanning each gRNA target site. (Lower) Evidence of HDAC class I and II gene targeting by PCR amplification of gDNA deletions in HDAC targeted cells. (C) Cell growth change by cell counts in 381T cells with CRISPR targeting of each class I and II HDAC gene, normalized to cells with safe-harbor control targeting 10 d after lentiviral transduction. (D and E) Immunofluorescence (IF) of MF20 in 381T cells with control safe-harbor (D) or HDAC3 CRISPR (E) targeting. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (F) Quantification of MF20 IF from targeted deletion of HDAC class I and II genes. (G) Quantification of MF20 IF in ERMS (RD and SMS-CTR) and ARMS (Rh3, Rh5, and Rh30) cell lines with HDAC3 CRISPR targeting. (H and I) IHC for HDAC3 in primary human skeletal muscle (H) and a representative RMS tumor section (I) (IHC magnification: 400×.) (Scale bar: 500 μm.) (Insets) Arrowheads point to nuclei. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (J) Summary of HDAC3 IHC from human RMS tumor samples. Error bars in C, F and G represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

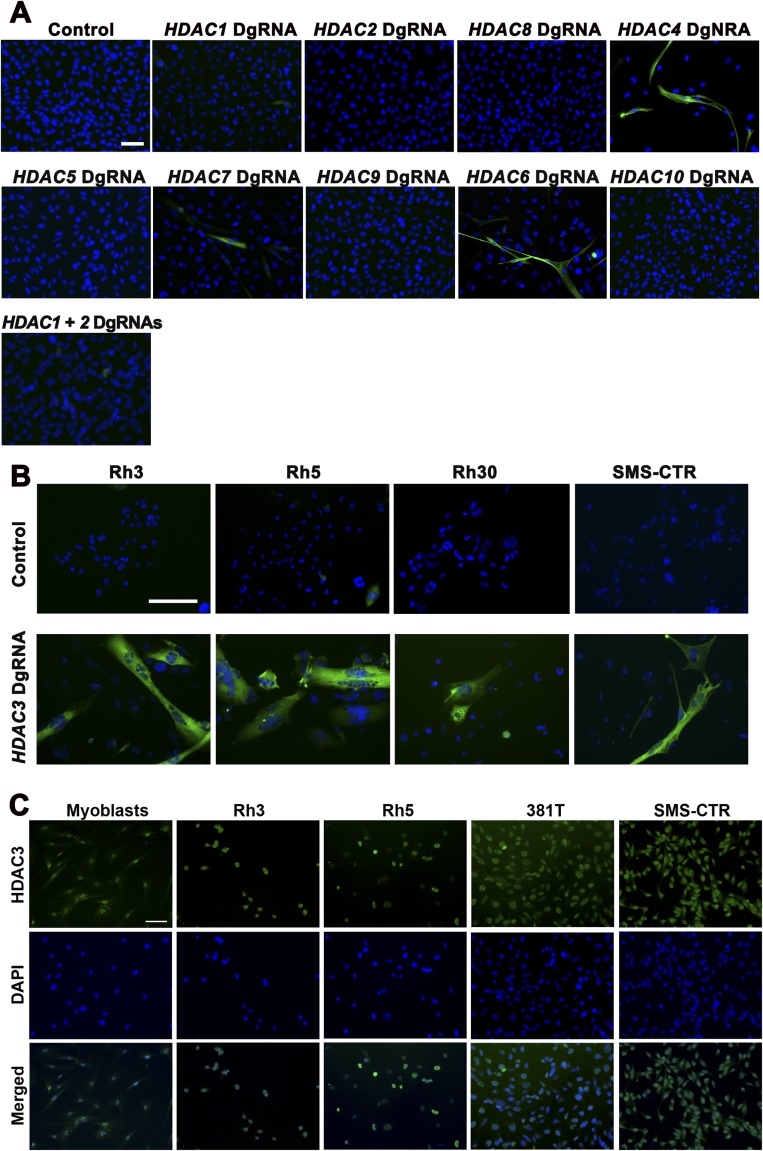

Fig. S1.

HDAC targeting in RMS cell lines and nuclear expression of HDAC3 in myoblasts and RMS cell lines. (A) Representative images of MF20 IF in 381T RMS cells with CRISPR targeting of class I and class II HDAC genes. The MF20 IF image for HDAC3 targeting is shown in Fig. 1E. (B) Representative images of MF20 IF in selected RMS cell lines (Rh3, Rh5, Rh30, and SMS-CTR) with control safe-harbor or HDAC3 CRISPR targeting. (C) Representative images of HDAC3 IF in myoblasts and in Rh3, Rh5, 381T, and SMS-CTR cell lines. (Scale bars: 25 μm in all panels.)

Table S1.

Targeting efficiency and gRNA sequences of class I and II HDAC genes

| Gene | Efficiency, % | gRNA1 | gRNA2 | gRNA3 |

| HDAC1 | 79 | GGACTGTCCAGTATTCGA | GCCTTCTACACCACGGAC | |

| HDAC2 | 78 | GTTTTGTCAGCTCTCAAC | GGAATACTTTCCTGGCAC | |

| HDAC3* | 77 | GTTCTGCTCGCGTTACAC | GAAGCCTTGCATATTGGT | GGGTCAATGCCAGGCGAT |

| HDAC4 | 87 | GCAGCTCTCCCGGCAGCACG | GTCGACACTCCGCTCTGGGG | |

| HDAC5 | 73 | GTTGCTGCTCCCGCAGTGTG | GAAGCTGTCGACACAGCAGG | |

| HDAC6 | 51 | GCTTCCCGGAAGGCCCTGAG | GCTGGTGGATGCGGTCCTGG | |

| HDAC7 | 71 | GAAGAATCCACTGCTCCGAA | GGCTGCGGCAGATACCCT | |

| HDAC8 | 54 | GAGGAACCGGCGGACAGT | GGAATATTACGATTGCGA | |

| HDAC9 | 72 | GGAGATGTTCCACTAAGGGG | GTCTGTGACGGGGCAATTTG | |

| HDAC10 | 52 | GCTCCTCTTCCGAGGCCTCG | GCTGCTCCCACTGGCCTTTG |

Three separate gRNAs were used for HDAC3 throughout the study: gRNA1&2 for tamoxifen inducible cells and gRNA1&3 for the lentiviral phenotypic screen; all gRNA combinations produced identical results. HDAC3 CRISPR mutants have mutations in the seed region of gRNAs 1&2.

CRISPR-mediated targeting of HDAC1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 significantly decreased tumor cell growth (Fig. 1C). Knockout of either HDAC3 or HDAC4 also resulted in distinct myogenic differentiation, as shown by the presence of morphologically multinucleated myotubes highlighted by myosin heavy chain (MF20)-positive immunostaining. However, the effect of HDAC4 knockout was limited compared with the suppression of tumor cell growth (>90% reduction in growth) and the extent of differentiation (60–80% differentiated) exhibited by HDAC3 knockout (Fig. 1 D–F and Fig. S1A). HDAC3 targeting also induced myogenic differentiation to varying degrees in a panel of five additional RMS cells lines (RD, SMS-CTR, Rh3, Rh5, and Rh30) derived from both ERMS and ARMS subtypes (Fig. 1G and Fig. S1B). In addition to single HDAC gene knockout, we targeted HDAC1 and HDAC2 simultaneously because they are known to have redundant functions (10). Double knockout of HDAC1 and HDAC2 resulted in no evidence of myogenic differentiation (Fig. S1A), suggesting that HDAC1 and 2 have a role in regulating ERMS proliferation but not myogenic differentiation pathways.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that normal skeletal muscle lacked nuclear HDAC3 expression. By contrast, 22 of 23 primary ERMS samples and 20 of 24 primary ARMS samples exhibited distinct nuclear expression of HDAC3 (Fig. 1 H–J). Proliferating human myoblasts as well as all analyzed RMS cell lines also exhibited nuclear HDAC3 expression, suggesting that HDAC3 likely has important functions in undifferentiated myoblast-like cells (Fig. S1C).

The level of myogenic differentiation observed with HDAC3 targeting was substantially higher than has been previously reported for treatment of RMS cells with pan-HDAC inhibitors (9). Because pan-HDAC inhibitors are unable to induce large-scale differentiation in RMS, we treated RMS cells with the HDAC3-selective inhibitor RGFP966 (Selleck Chemicals LLC) to determine if direct HDAC3 inhibition can induce the extent of myogenic differentiation observed with HDAC3 knockout. Surprisingly, the treatment of RMS cells with RGFP966 resulted in only modest growth suppression (Fig. S2 A–C) and myogenic differentiation (30–35%) (Fig. S2 D–F), suggesting that current HDAC inhibitors lack the potency necessary to suppress growth and induce differentiation of RMS as a single agent.

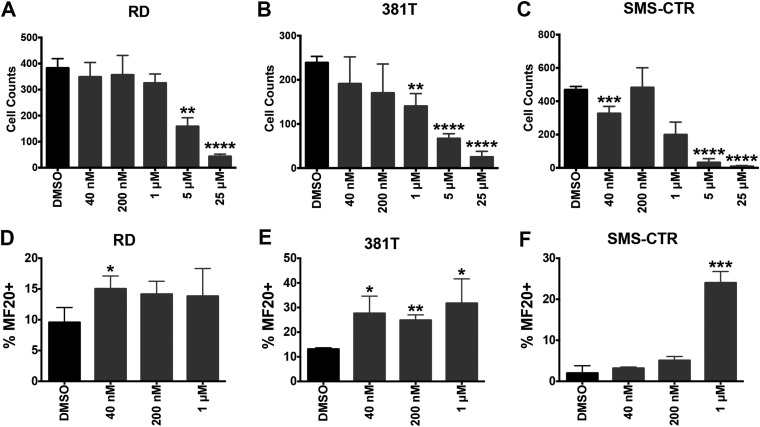

Fig. S2.

Treatment of RMS (RD, 318T, and SMS-CTR) cells with the HDAC3-selective HDAC inhibitor RGFP966. (A–C) Summary of changes in cell growth of RMS cell lines treated with five concentrations of RGFP966 or control (DMSO) showing an IC50 of 0.08 μM in the cell-free assay and >200-fold selectivity over other HDACs. (D–F) Summary of MF20 IF quantifications of RMS cell lines treated with three concentrations of RGFP966 or control (DMSO). Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Conditional HDAC3 Knockout Arrests Tumor Growth and Induces Myogenic Differentiation of RMS Tumors in Vivo.

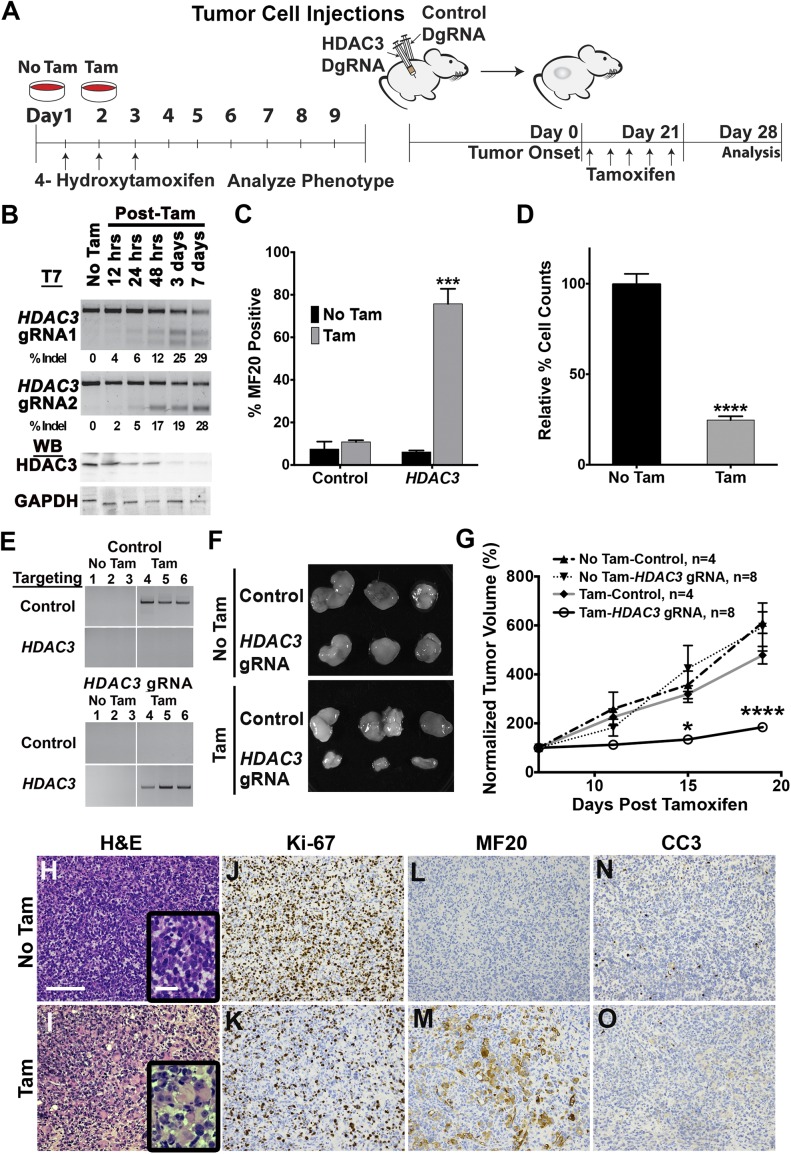

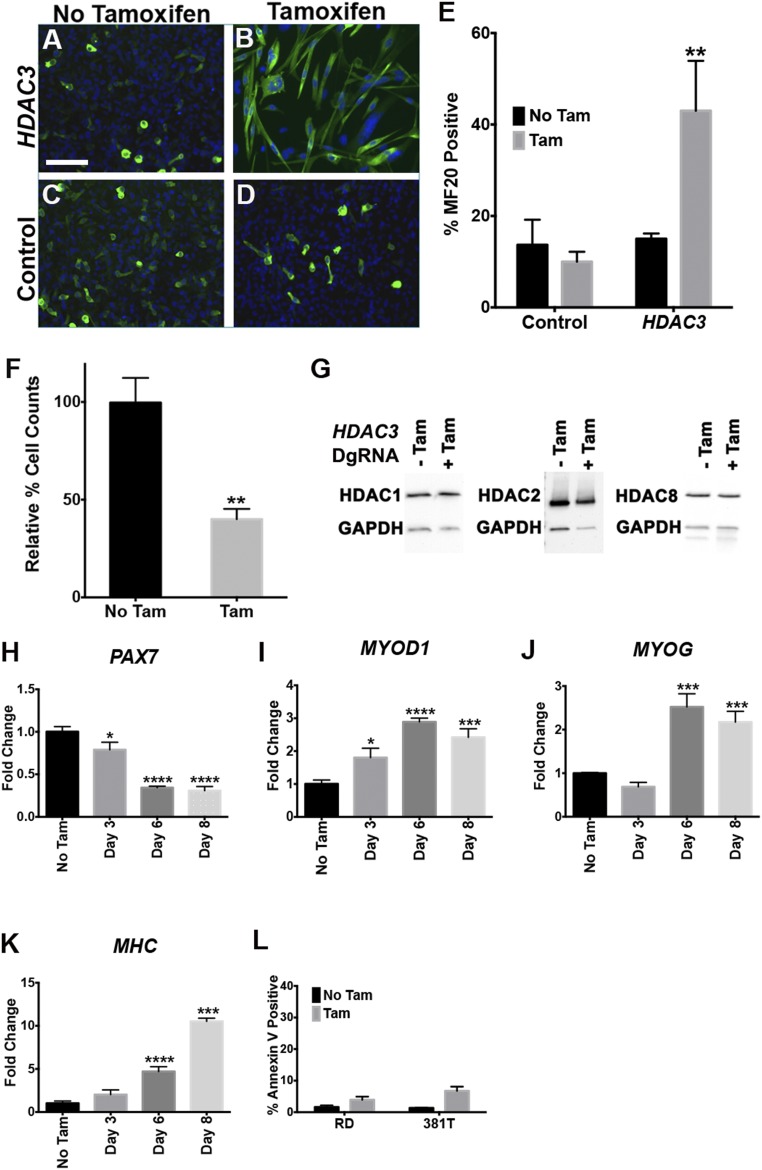

To investigate the function of HDAC3 in RMS, we developed a tamoxifen-inducible Cas9-ERT2 PiggyBac transposon to control gene targeting temporally both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2A). Tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 gene knockout in ERMS cells (Fig. 2B) validated the results from the CRISPR phenotypic screen by inducing growth arrest and concomitant myogenic differentiation in more than 75% of the treated cells (Fig. 2 C and D and Fig. S3 A–F). This high-efficiency inducible gene targeting of pooled RMS tumor cells significantly reduced overall HDAC3 protein levels without affecting the levels of other class I HDAC proteins (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3G). HDAC3-knockout cells exhibited up-regulated expression of key myogenic regulatory genes (Fig. S3 H–K) with no increase in apoptosis (Fig. S3L), suggesting that the decrease in tumor cell growth was predominantly caused by terminal myogenic differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Tamoxifen-inducible CRISPR targeting of HDAC3 in vitro and in vivo. (A) Tamoxifen (Tam)-inducible CRISPR/Cas9 experimental design. (B) T7 endonuclease assay assessing targeting efficiency of each HDAC3-specific gRNA (Upper) and Western blot of HDAC3 protein after tamoxifen induction (Lower). (C and D) Quantification of MF20 IF and cell growth by cell counts (C) and normalized to no TAM control (D) in HDAC3-targeted 381T cells with tamoxifen (10 d posttreatment) or without tamoxifen. Error bars the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (E) PCR-based detection of targeted genomic deletions in three tumor xenografts per treatment group. (F) 381T xenograft tumors isolated from the safe-harbor control or HDAC3-inducible treatment groups. (G) Tumor growth change, normalized to day 0 of tamoxifen treatment. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. (H–O) Histology of xenograft tumors by H&E (H and I) and IHC for Ki-67 (J and K), MF20 (L and M), and cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) (N and O). (Magnification for H&E and IHC: 200×.) (Scale bar: 500 μm; Inset: 20 μm.) ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. S3.

Tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 targeting in ERMS cells induces myogenic differentiation. (A–D) Representative MF20 IF images of 381T ERMS cells with induced HDAC3 targeting 10 d after tamoxifen (Tam) treatment along with no-Tam control. (E and F) Summary of MF20 IF (E) and cell growth by cell counts (F) of RD ERMS cells with induced HDAC3 CRISPR targeting. (G) Western blots assessing protein expression levels of HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC8 in 381T ERMS cells with HDAC3 CRISPR targeting. (H–K) RT-qPCR assessing the expression of PAX7 (H), MYOD1 (I), MYOG (J), and MHC (MYH14) (K) in 381T ERMS cells without or 3, 6, and 8 d after tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 targeting. (L) Summary of Annexin V flow cytometry-based assays in RD and 381T ERMS cells with or without tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 targeting. Error bars in E, F, and H–L represent the mean ± SD of three biological or technical replicates, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

We validated the HDAC3 loss-of-function effects in vivo by inducing HDAC3 targeting in ERMS tumor xenografts. Immunocompromised NOD-SCID Il2rg−/− (NSG) mice were injected on bilateral flanks with tamoxifen-inducible 381T ERMS cells targeting either HDAC3 or a safe-harbor region of the genome (Chr 4: 58,110,237–58,110,808; GRCH38.p2) (Fig. 2A). After tumor development, the mice were treated with tamoxifen to induce targeted gene knockout in the respective tumors (Fig. 2E). In contrast to safe-harbor control xenografts, HDAC3-targeted xenografts showed at least 50% reduction in tumor growth 2 weeks after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 2 F and G). Histological analysis of HDAC3-knockout tumors revealed an increase in the presence of multinucleated cells resembling myotubes (Fig. 2 H and I). Similarly, HDAC3-targeted xenografts demonstrated a significant decrease in the proliferation index (Ki67) (Fig. 2 J and K) and an increased number of MF20+ differentiated cells (Fig. 2 L and M) but no increase in apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3) (Fig. 2 N and O).

The Nuclear Receptor Corepressor/HDAC3 Complex Blocks Myogenic Differentiation in RMS.

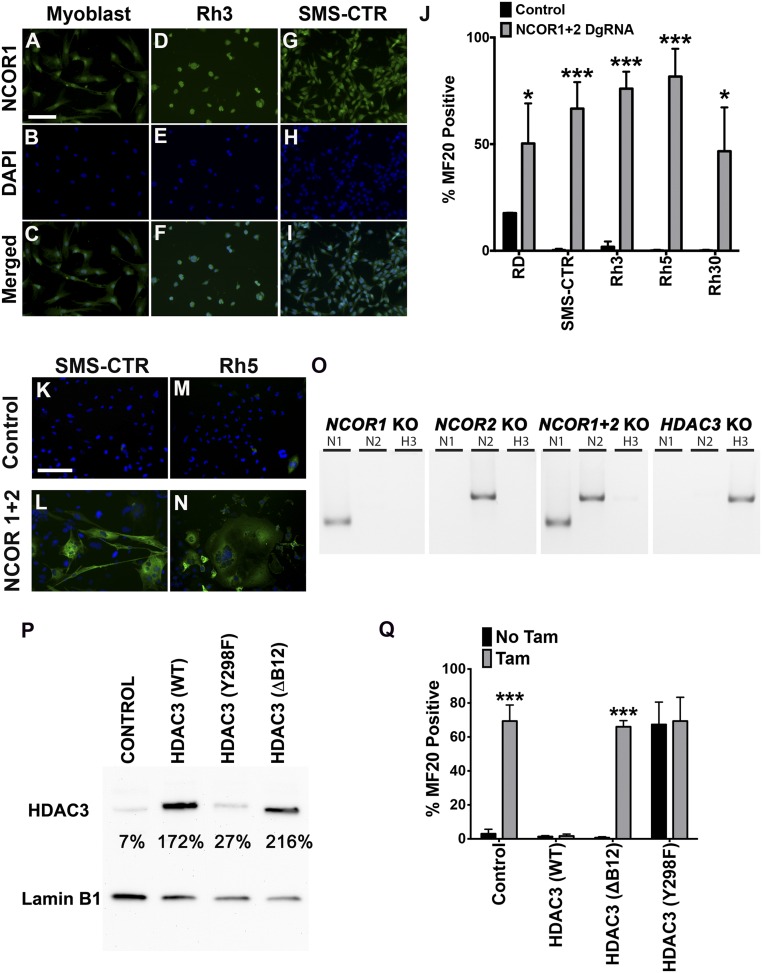

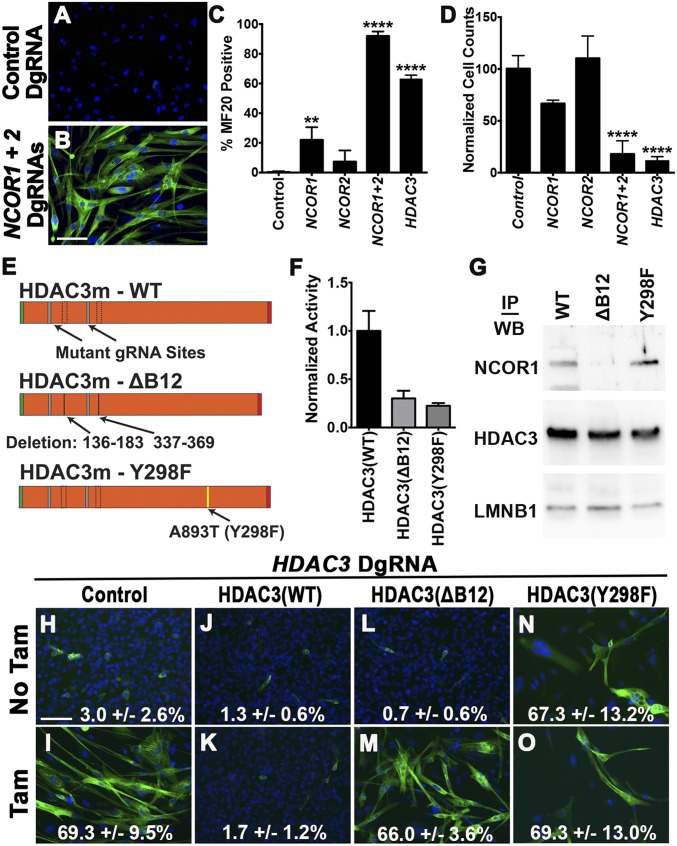

Using mass spectrometry and coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays on 381T ERMS cells, we identified nuclear receptor corepressors 1 (NCOR1) and 2 (NCOR2) as the top HDAC3-interacting factors with transcription factor-binding activity (Fig. S4). Nuclear expression of NCOR1 was also detected in myoblasts and all analyzed RMS cell lines (Fig. S5 A–I). Although individual knockout of NCOR1 and NCOR2 resulted in limited myogenic differentiation, likely because of functional redundancy, double knockout of NCOR1 and NCOR2 in a panel of six RMS cell lines (RD, 381T, SMS-CTR, Rh3, Rh5, and Rh30) resulted in large-scale myogenic differentiation and reduction in cell growth, similar to that seen with HDAC3 knockout (Fig. 3 A–D and Fig. S5 J–O). These results suggest that the NCOR/HDAC3 transcriptional repressor complex, not an alternative HDAC3-mediated process, is primarily responsible for restricting myogenic differentiation in RMS.

Fig. S4.

Protein profiling of HDAC3-interacting factors in ERMS cells. (A) GO analysis of co-IP products using HDAC3 antibody in nuclear extract of 381T ERMS cells. (B) Top protein candidates with transcription factor-binding activity from HDAC3 co-IP mass spectrometry. NCOR1 and NCOR2 (highlighted) are among the top candidates. (C) Western blot analysis of HDAC3, NCOR1, and NCOR2 protein expression of HDAC3 co-IP products. The panels in C are derived from the same blot with the same exposure.

Fig. S5.

The NCOR complex is required for HDAC3-mediated repression of myogenic differentiation in RMS. (A–I) Representative images of NCOR1 IF in human myoblasts and Rh3 and SMS-CTR cell lines. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (J) Summary of MF20 IF in ERMS (RD, SMS-CTR) and ARMS (Rh3, Rh5, Rh30) cell lines with CRISPR-mediated NCOR1 and NCOR2 double-gene targeting. (K–N) Select MF20 IF images of NCOR1 and NCOR2 double-knockouts in SMS-CTR and Rh5 cells. (O) Agarose gel image of deletion PCR products from amplification of targeted genomic regions by DgRNAs. (P) Western blot of total cell lysate extracted from parental 381T cells (control) and cells overexpressing WT or mutant (Y298F or ΔB12) HDAC3 proteins. Quantification of each band intensity normalized to Lamin B1 as loading control is indicated. (Q) Summary of MF20 IF in HDAC3 mutants with or without tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 knockout. Error bars in J and Q represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

The NCOR complex interacts with HDAC3 to suppress myogenic differentiation in ERMS. (A and B) MF20 IF images of 381T cells with safe-harbor control CRISPR targeting (A) and NCOR1 and NCOR2 double-gene targeting (B). (C) Summary of MF20 IF in 381T cells with HDAC3, NCOR1, and NCOR2 CRISPR targeting. (D) Cell growth by cell counts normalized to cells with safe-harbor control targeting. (E) Schematics of CRISPR mutant HDAC3 (HDAC3m) expression constructs. (F) Assay of HDAC deacetylase activity in HDAC3m mutants at day 4 after HDAC3 knockout. (G) Western blot/co-IP assays assessing the interaction of HDAC3m mutants. (H–O) MF20 IF images and quantification data of HDAC3 CRISPR-inducible 381T cells transduced with empty-vector control (H and I), WT HDAC3m (J and K), or HDAC3m mutants (L–O) with or without tamoxifen (Tam) treatment. Error bars in C and D represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. All cell-culture experiments (viral transduction or tamoxifen treatment) were analyzed 10 d posttreatment. (Scale bars in B and H: 50 μm.) **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

We next performed structure–function analysis to determine whether the NCOR-interaction domain and/or the enzymatic activity of HDAC3 were required for its function in RMS. Site-directed mutagenesis of HDAC3 was used to produce two mutant proteins, one lacking two distinct NCOR-binding sites in the N terminus (ΔB12) (11) and the second with a Y298F point mutation in the catalytic site (Fig. 3E) (11). These mutant HDAC3 overexpression constructs were made CRISPR/Cas9 resistant by introducing silent mutations in the two HDAC3 gRNA target sites (Fig. 3E). Both HDAC3 mutants exhibited loss of deacetylase activity (Fig. 3F) when overexpressed in HDAC3-knockout ERMS cells, as is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that the NCOR/HDAC3 complex is required for HDAC3 deacetylase activity (11, 12). However, only the ΔB12 HDAC3 mutant failed to interact with the NCOR complex (Fig. 3G). Myogenic differentiation in HDAC3-targeted ERMS cells was fully rescued by the overexpression of CRISPR/Cas9-resistant WT HDAC3 (Fig. 3 H–K and Fig. S5P). In contrast, overexpression of either the ΔB12 or the Y298F HDAC3 mutant failed to restrict differentiation after HDAC3 knockout, suggesting that both the NCOR/HDAC3 complex and HDAC3 deacetylase activity were critical for suppressing differentiation in RMS (Fig. 3 L–O and Fig. S5P). Interestingly, the Y298F HDAC3 mutant was also able to induce myogenic differentiation independently in ERMS cells, likely through dominant-negative competition with endogenous HDAC3 (Fig. 3 N and O and Fig. S5P).

The NCOR/HDAC3 Complex Blocks Myoblast Determination Protein 1-Mediated Myogenic Differentiation in ERMS.

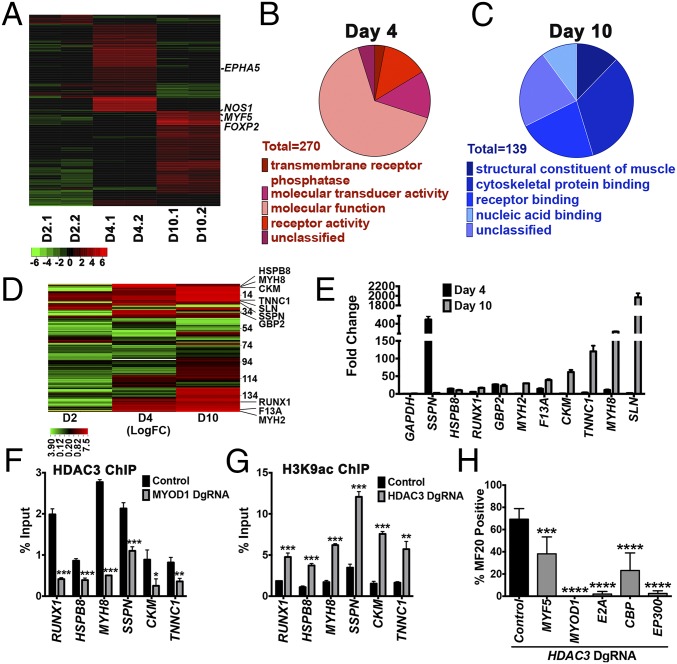

To identify essential genes and pathways regulated by the NCOR/HDAC3 complex, RNA sequencing was performed on ERMS cells 2, 4, and 10 d after tamoxifen-induced CRISPR-mediated HDAC3 targeting. Based on Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, differentially expressed genes immediately after HDAC3 knockout (day 4; 414 genes, P < 0.05) were enriched for receptor and signal transduction functions, whereas late-stage differentially expressed genes (day 10; 199 genes, P < 0.05) were enriched for cytoskeletal protein binding and striated muscle structural and contraction functions (Fig. 4 A–C and Table S2). This global gene-expression profile induced by HDAC3 knockout in ERMS cells highlighted the clear transition from a neoplastic to fully differentiated muscle state.

Fig. 4.

HDAC3 suppresses MYOD1/E2A-mediated myogenic differentiation in ERMS. (A) Heatmap analysis showing expression levels of differentially expressed genes 2, 4, and 10 d after tamoxifen-induced CRISPR HDAC3 targeting. Expression values are derived from RNA sequencing analysis of two biological replicates. (B and C) GO analysis of top differentially expressed genes (P < 0.05) at days 4 (B) and 10 (C). (D) Heatmap showing expression patterns of the MYOD1-target gene set (137 genes) in 381T cells with HDAC3 targeting at days 2, 4, and 10 after tamoxifen induction. RT-qPCR–validated genes are identified. (E) Expression of MYOD1 target genes (RT-qPCR) at days 4 and 10 normalized to day 2 after HDAC3 gene targeting. (F and G) ChIP using antibody against HDAC3 in control and MYOD1-targeted cells (F) or antibody against acetylated H3K9 in control and HDAC3-targeted cells (G) 4 d after transduction. (H) Summary of MF20 IF in 381T cells with dual CRISPR targeting of MYF5, MYOD1, E2A, CBP, or EP300 before HDAC3 targeting. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Table S2.

Differentially expressed genes from the heatmap in Fig. 4A

| Gene | Chromosome number | Start | End | Strand | Day 2.1 | Day 2.2 | Day 4.1 | Day 4.2 | Day 10.1 | Day 10.2 |

| SCN4A | Chr17 | 63,938,554 | 639,72,918 | − | 0.35 | 0.34 | 6.70 | 6.65 | 5.20 | 4.87 |

| INHBE | Chr12 | 57,455,313 | 57,458,008 | + | 0.88 | 1.53 | 5.66 | 5.51 | 4.32 | 3.75 |

| FCRLA | Chr1 | 161,706,972 | 161,714,352 | + | 0.50 | 0.57 | 4.30 | 4.33 | 4.45 | 4.36 |

| ARHGAP9 | Chr12 | 57,472,255 | 57,479,850 | − | 0.35 | 1.14 | 3.80 | 3.69 | 4.65 | 3.72 |

| EXTL1 | Chr1 | 26,021,780 | 26,036,463 | + | 1.56 | 1.01 | 4.55 | 4.49 | 4.36 | 4.08 |

| GRAMD1B | Chr11 | 123,525,636 | 123,627,771 | + | 1.56 | 1.65 | 4.51 | 4.61 | 4.80 | 4.68 |

| EGR1 | Chr5 | 138,465,492 | 138,469,315 | + | 4.06 | 3.79 | 6.62 | 6.54 | 5.46 | 6.37 |

| FAM214A | Chr15 | 52,581,321 | 52,678,634 | − | 1.62 | 1.37 | 3.62 | 3.71 | 3.01 | 2.94 |

| TGFB2 | Chr1 | 218,345,334 | 218,444,619 | + | 2.18 | 1.75 | 4.10 | 4.01 | 3.15 | 3.38 |

| RNF180 | Chr5 | 64,165,844 | 64,372,869 | + | 1.86 | 1.35 | 3.99 | 4.01 | 3.62 | 2.93 |

| VASH2 | Chr1 | 212,950,520 | 212,991,585 | + | 6.02 | 5.85 | 8.29 | 8.27 | 7.82 | 7.53 |

| UGT3A1 | Chr5 | 35,953,089 | 36,001,028 | − | 0.27 | 0.65 | 3.99 | 3.88 | 2.19 | 2.69 |

| FAM178B | Chr2 | 96,875,882 | 96,986,564 | − | 0.31 | 0.84 | 3.28 | 3.34 | 2.97 | 2.21 |

| DRP2 | ChrX | 101,219,944 | 101,264,496 | + | 1.17 | 1.39 | 3.98 | 3.86 | 3.25 | 2.76 |

| SORBS1 | Chr10 | 95,311,773 | 95,561,420 | − | 1.84 | 2.07 | 4.82 | 4.83 | 4.16 | 3.57 |

| NFASC | Chr1 | 204,828,654 | 205,022,822 | + | 3.09 | 3.00 | 6.25 | 6.27 | 5.66 | 4.79 |

| SORCS1 | Chr10 | 106,573,663 | 107,164,708 | − | 3.84 | 3.42 | 6.60 | 6.62 | 5.66 | 5.64 |

| CD274 | Chr9 | 5,450,503 | 5,470,567 | + | 0.88 | 2.02 | 3.56 | 3.37 | 3.38 | 2.31 |

| LAMC2 | Chr1 | 183,186,039 | 183,245,127 | + | 0.23 | 1.12 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.45 | 2.10 |

| SSPN | Chr12 | 26,195,336 | 26,234,775 | + | 0.73 | 0.42 | 3.45 | 3.40 | 2.27 | 2.11 |

| EPHB1 | Chr3 | 134,795,257 | 135,260,465 | + | 1.03 | 1.24 | 3.88 | 3.89 | 2.67 | 2.15 |

| RYR3 | Chr15 | 33,310,962 | 33,866,103 | + | 1.32 | 1.49 | 3.78 | 3.96 | 2.95 | 2.36 |

| ADAMTS14 | Chr10 | 70,672,803 | 70,762,439 | + | 2.52 | 3.43 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 4.95 | 3.99 |

| DDIT3 | Chr12 | 57,516,588 | 57,520,517 | − | 1.67 | 2.58 | 4.81 | 4.89 | 3.69 | 3.24 |

| EVC2 | Chr4 | 5,562,419 | 5,709,548 | − | 0.35 | 0.90 | 2.67 | 2.48 | 1.81 | 1.37 |

| TRPM8 | Chr2 | 233,917,398 | 234,019,522 | + | 0.00 | 0.78 | 2.84 | 2.75 | 1.82 | 1.64 |

| SCN7A | Chr2 | 166,403,573 | 166,486,971 | − | 2.43 | 1.16 | 3.69 | 3.88 | 3.36 | 5.41 |

| FRY | Chr13 | 32,031,300 | 32,296,639 | + | 1.03 | 0.71 | 2.72 | 2.66 | 3.60 | 2.84 |

| PITPNM3 | Chr17 | 6,451,263 | 6,556,557 | − | 1.03 | 0.57 | 2.48 | 2.19 | 2.90 | 2.38 |

| DOK3 | Chr5 | 177,501,905 | 177,510,426 | − | 2.30 | 1.91 | 3.81 | 3.89 | 4.45 | 3.99 |

| PLCXD2 | Chr3 | 111,674,676 | 111,846,447 | + | 0.93 | 0.29 | 2.30 | 2.32 | 2.75 | 2.29 |

| YPEL2 | Chr17 | 59,331,692 | 59,401,734 | + | 1.03 | 0.87 | 3.26 | 3.33 | 3.17 | 2.97 |

| ACVR1C | Chr2 | 157,526,767 | 157,628,887 | − | 0.19 | 0.38 | 2.23 | 2.36 | 3.21 | 2.13 |

| NPNT | Chr4 | 10,895,440 | 105,971,671 | + | 4.96 | 5.06 | 7.23 | 7.37 | 7.87 | 7.02 |

| ZNF385B | Chr2 | 179,441,984 | 179,861,505 | − | 0.54 | 0.42 | 1.88 | 2.24 | 1.81 | 1.30 |

| SPON2 | Chr4 | 1,166,933 | 1,208,962 | − | 0.23 | 0.20 | 1.35 | 1.51 | 1.22 | 0.98 |

| ZBTB7C | Chr18 | 4,8027,268 | 48,137,309 | − | 0.39 | 0.34 | 1.29 | 1.61 | 1.56 | 1.19 |

| ABI3BP | Chr3 | 100,749,335 | 100,993,490 | − | 0.19 | 0.10 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

| TCP11L2 | Chr12 | 106,302,791 | 10,6347,014 | + | 0.67 | 0.42 | 1.88 | 1.92 | 1.36 | 1.55 |

| ARHGAP25 | Chr2 | 68,734,781 | 68,826,825 | + | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.63 | 1.51 | 1.03 | 0.50 |

| ANKRD44 | Chr2 | 196,986,662 | 197,310,797 | − | 0.73 | 0.71 | 2.05 | 2.33 | 1.54 | 1.45 |

| TEX29 | Chr13 | 111,316,185 | 111,344,247 | + | 0.27 | 0.25 | 1.73 | 1.53 | 1.18 | 0.96 |

| ADORA2A-AS1 | Chr22 | 24,429,206 | 24,495,074 | − | 0.27 | 0.10 | 1.18 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.12 |

| ATP2C2 | Chr16 | 84,368,523 | 84,464,187 | + | 0.39 | 0.42 | 1.33 | 1.37 | 1.78 | 1.56 |

| LOC101928075 | Chr14 | 70,608,798 | 70,641,298 | − | 0.47 | 0.34 | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.68 | 1.60 |

| LOC101927851 | Chr1 | 234,957,343 | 234,963,999 | − | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.78 | 1.02 | 1.42 | 1.39 |

| TP63 | Chr3 | 18,9631,427 | 189,897,279 | + | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.09 |

| EGR2 | Chr10 | 62,811,996 | 62,819,167 | − | 0.05 | 0.20 | 1.68 | 1.75 | 1.32 | 1.85 |

| ZNF366 | Chr5 | 72,439,899 | 72,507,422 | − | 0.70 | 0.38 | 2.00 | 2.14 | 1.89 | 2.21 |

| DENND2C | Chr1 | 114,584,575 | 114,670,111 | − | 0.57 | 0.29 | 2.11 | 1.75 | 1.62 | 1.58 |

| DOCK8 | Chr9 | 214,865 | 465,259 | + | 0.64 | 0.20 | 2.01 | 2.16 | 1.52 | 1.86 |

| MAT1A | Chr10 | 80,271,820 | 80,289,678 | − | 0.54 | 0.15 | 1.95 | 1.69 | 1.82 | 2.65 |

| SEMA3G | Chr3 | 52,433,252 | 52,445,027 | − | 0.54 | 0.38 | 1.47 | 1.61 | 1.27 | 2.32 |

| DNALI1 | Chr1 | 37,556,919 | 37,566,857 | + | 0.35 | 0.25 | 1.18 | 1.53 | 1.71 | 2.04 |

| ZSCAN10 | Chr16 | 3,088,891 | 3,099,317 | − | 0.79 | 0.54 | 1.68 | 1.65 | 2.15 | 2.43 |

| F13A1 | Chr6 | 6,144,078 | 6,320,691 | − | 0.64 | 3.03 | 4.01 | 3.90 | 5.85 | 4.80 |

| EGLN3 | Chr14 | 33,924,215 | 3,395,1078 | − | 3.30 | 4.16 | 5.74 | 5.67 | 6.97 | 6.81 |

| HRH1 | Chr3 | 11,137,093 | 11,263,253 | + | 1.73 | 2.41 | 3.56 | 3.87 | 4.53 | 5.07 |

| PTK6 | Chr20 | 63,528,423 | 63,537,370 | − | 0.50 | 0.81 | 2.37 | 2.39 | 4.19 | 2.87 |

| MAP1LC3C | Chr1 | 241,995,490 | 241,999,083 | − | 0.57 | 0.81 | 1.97 | 1.92 | 3.29 | 2.88 |

| MEG3 | Chr14 | 100,826,108 | 100,861,023 | + | 3.76 | 3.75 | 5.28 | 5.07 | 6.61 | 5.71 |

| SLC25A34 | Chr1 | 15,736,314 | 15,741,392 | + | 2.54 | 2.82 | 4.04 | 3.99 | 5.22 | 4.50 |

| MYBPC2 | Chr19 | 50,432,903 | 50,466,326 | + | 1.69 | 1.67 | 4.24 | 4.22 | 5.95 | 5.66 |

| TXLNB | Chr6 | 139,240,061 | 139,292,071 | − | 2.07 | 2.06 | 4.44 | 4.24 | 6.40 | 5.99 |

| APOBEC2 | Chr6 | 41,053,201 | 41,064,891 | + | 2.13 | 1.72 | 3.78 | 4.03 | 5.75 | 6.11 |

| IL34 | Chr16 | 70,579,895 | 70,660,682 | + | 0.70 | 0.93 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 4.54 | 4.47 |

| KIF19 | Chr17 | 74,326,212 | 74,355,820 | + | 0.98 | 0.90 | 2.64 | 2.82 | 4.46 | 4.20 |

| ABCG1 | Chr21 | 42,199,689 | 42,297,244 | + | 2.98 | 1.06 | 4.47 | 4.67 | 5.74 | 6.28 |

| PRUNE2 | Chr9 | 76,611,376 | 76,906,087 | − | 4.08 | 3.12 | 6.62 | 6.62 | 8.41 | 7.34 |

| ADGRV1 | Chr5 | 90,558,800 | 91,164,216 | + | 3.57 | 2.10 | 1.99 | 1.79 | 4.74 | 3.75 |

| UNC80 | Chr2 | 209,771,993 | 209,999,300 | + | 5.44 | 3.65 | 2.93 | 3.15 | 6.09 | 5.56 |

| CCDC102B | Chr18 | 68,715,254 | 69,055,189 | + | 3.57 | 3.64 | 2.15 | 2.12 | 4.79 | 4.32 |

| EGF | Chr4 | 109,912,884 | 110,012,962 | + | 2.08 | 1.93 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 4.18 | 2.82 |

| KCNB1 | Chr20 | 49,371,968 | 49,482,644 | − | 2.33 | 2.43 | 1.41 | 1.22 | 4.12 | 2.42 |

| CXCL8 | Chr4 | 73,740,506 | 73,743,716 | + | 2.76 | 5.34 | 1.73 | 1.84 | 5.51 | 4.56 |

| IL1B | Chr2 | 112,829,760 | 112,836,779 | − | 0.14 | 2.13 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 2.43 | 2.97 |

| MPP4 | Chr2 | 201,644,874 | 201,698,694 | − | 1.49 | 3.73 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 3.76 | 4.19 |

| GDF15 | Chr19 | 18,386,158 | 18,389,176 | + | 3.37 | 5.13 | 3.17 | 3.19 | 5.97 | 5.66 |

| NPAS2 | Chr2 | 100,820,151 | 100,996,825 | + | 4.85 | 5.81 | 4.32 | 4.24 | 6.87 | 6.83 |

| OXTR | Chr3 | 8,750,409 | 8,769,614 | − | 2.61 | 3.69 | 2.56 | 2.35 | 4.71 | 4.56 |

| IL6R | Chr1 | 154,405,193 | 154,469,450 | + | 1.03 | 2.34 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 2.73 | 2.49 |

| MYL9 | Chr20 | 36,541,484 | 36,549,823 | + | 4.88 | 6.22 | 4.74 | 4.61 | 7.42 | 6.44 |

| SGIP1 | Chr1 | 66,533,569 | 66,751,139 | + | 2.53 | 3.16 | 2.02 | 1.94 | 4.35 | 3.78 |

| LINC00472 | Chr6 | 71,407,865 | 71,420,745 | − | 2.59 | 2.02 | 3.08 | 3.25 | 4.78 | 4.15 |

| MIR133B | Chr6 | 52,148,923 | 52,149,041 | + | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.77 | 1.84 | 3.45 | 2.84 |

| CFAP44 | Chr3 | 113,286,930 | 113,441,514 | − | 1.38 | 1.04 | 1.85 | 1.87 | 3.16 | 2.87 |

| PLEKHM1P | Chr17 | 64,784,841 | 64,837,184 | − | 1.47 | 0.90 | 1.92 | 1.82 | 3.29 | 3.08 |

| SLC7A4 | Chr22 | 21,028,718 | 21,032,558 | − | 1.85 | 0.96 | 2.46 | 2.37 | 3.79 | 3.43 |

| HAP1 | Chr17 | 41,722,639 | 41,734,646 | − | 1.85 | 1.12 | 2.35 | 2.54 | 3.73 | 3.74 |

| SPAG6 | Chr10 | 22,345,445 | 22,417,610 | + | 0.98 | 0.38 | 1.68 | 1.51 | 2.86 | 3.06 |

| TEX14 | Chr17 | 58,556,677 | 58,692,055 | − | 0.70 | 0.50 | 1.60 | 1.75 | 3.26 | 3.13 |

| CYSRT1 | Chr9 | 137,224,635 | 13,722,6311 | + | 2.02 | 2.21 | 2.98 | 2.99 | 4.75 | 4.43 |

| HHATL | Chr3 | 42,692,663 | 42,702,827 | − | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 2.61 | 2.40 |

| HIST2H2BE | Chr1 | 14,9884,460 | 149,886,682 | − | 2.40 | 2.30 | 3.10 | 3.15 | 4.73 | 4.31 |

| C10orf10 | Chr10 | 44,976,261 | 44,978,882 | − | 2.16 | 2.19 | 3.27 | 3.06 | 4.31 | 4.70 |

| FBXO32 | Chr8 | 123,497,887 | 123,541,253 | − | 1.45 | 1.86 | 2.24 | 2.47 | 3.83 | 3.90 |

| SBK2 | Chr19 | 55,529,733 | 55,536,294 | − | 2.87 | 3.40 | 4.00 | 4.23 | 6.07 | 5.45 |

| CEACAM19 | Chr19 | 44,671,452 | 44,684,355 | + | 1.17 | 1.26 | 1.85 | 1.97 | 3.88 | 3.13 |

| CASC18 | Chr12 | 105,704,203 | 105,744,063 | + | 0.50 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 1.37 | 3.48 | 2.87 |

| FBXL22 | Chr15 | 63,597,353 | 63,602,421 | + | 0.14 | 0.54 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 3.11 | 2.47 |

| SBK3 | Chr19 | 55,540,656 | 55,545,543 | − | 0.70 | 0.90 | 1.53 | 1.77 | 3.70 | 3.05 |

| CACNB1 | Chr17 | 39,173,456 | 39,197,703 | − | 2.93 | 2.81 | 3.83 | 3.63 | 5.58 | 5.00 |

| MFSD7 | Chr4 | 681,824 | 689,441 | − | 1.01 | 0.75 | 1.74 | 1.47 | 3.42 | 2.72 |

| FAM78A | Chr9 | 131,258,078 | 131,276,519 | − | 2.37 | 2.03 | 3.57 | 3.13 | 5.26 | 4.50 |

| SYNPO2L | Chr10 | 73,644,881 | 73,656,105 | − | 6.00 | 5.93 | 7.24 | 6.89 | 8.74 | 8.25 |

| KLHL40 | Chr3 | 42,685,519 | 42,692,446 | + | 2.23 | 1.99 | 3.59 | 3.18 | 5.83 | 5.34 |

| DLG2 | Chr11 | 83,455,013 | 85,627,270 | − | 1.56 | 1.01 | 2.58 | 2.52 | 4.72 | 4.54 |

| SMYD1 | Chr2 | 88,067,780 | 88,113,383 | + | 5.57 | 4.78 | 6.50 | 6.36 | 8.77 | 8.57 |

| COL20A1 | Chr20 | 63,293,186 | 63,330,933 | + | 2.86 | 1.83 | 3.79 | 3.90 | 6.06 | 5.49 |

| PGM5P2 | Chr9 | 41,007,015 | 41,074,625 | − | 1.42 | 1.06 | 2.55 | 2.61 | 4.90 | 4.36 |

| PRR32 | ChrX | 126,819,764 | 126,821,785 | + | 3.07 | 2.67 | 4.20 | 4.34 | 6.24 | 5.97 |

| KY | Chr3 | 134,599,923 | 134,651,022 | − | 1.32 | 1.12 | 2.43 | 2.79 | 4.33 | 4.52 |

| HSPB7 | Chr1 | 16,014,028 | 16,018,790 | − | 1.13 | 0.57 | 2.41 | 2.18 | 4.22 | 3.52 |

| RNF224 | Chr9 | 137,227,566 | 137,229,638 | + | 2.02 | 1.16 | 2.86 | 3.02 | 4.77 | 4.37 |

| SLC34A3 | Chr9 | 137,230,757 | 137,236,554 | + | 2.53 | 1.45 | 3.46 | 3.43 | 5.25 | 4.80 |

| RYR1 | Chr19 | 38,433,700 | 38,587,564 | + | 6.87 | 6.08 | 7.42 | 7.49 | 9.80 | 8.62 |

| CHRNG | Chr2 | 232,539,727 | 232,546,328 | + | 5.77 | 4.62 | 6.33 | 6.37 | 8.64 | 7.91 |

| ZNF106 | Chr15 | 42,412,437 | 42,491,197 | − | 9.46 | 8.28 | 9.98 | 9.99 | 12.03 | 11.58 |

| PGAM2 | Chr7 | 44,062,727 | 44,065,587 | − | 2.19 | 1.14 | 2.56 | 2.18 | 4.62 | 4.01 |

| LINCMD1 | Chr6 | 52,146,814 | 52,151,023 | − | 2.07 | 1.51 | 2.44 | 2.23 | 4.44 | 3.88 |

| HRC | Chr19 | 49,151,199 | 49,155,424 | − | 5.34 | 4.54 | 5.65 | 5.60 | 7.73 | 7.18 |

| PKHD1 | Chr6 | 51,615,347 | 52,087,625 | − | 1.21 | 0.61 | 1.61 | 1.69 | 3.93 | 3.07 |

| TRIM63 | Chr1 | 26,051,305 | 26,067,634 | − | 2.36 | 1.01 | 2.62 | 2.60 | 4.39 | 4.33 |

| TAGLN3 | Chr3 | 111,998,739 | 112,013,888 | + | 2.70 | 2.30 | 3.60 | 3.46 | 5.39 | 5.39 |

| MYPN | Chr10 | 68,106,117 | 68,212,016 | + | 4.87 | 4.33 | 5.52 | 5.34 | 7.39 | 7.11 |

| PPFIA4 | Chr1 | 203,026,521 | 203,078,736 | + | 4.97 | 4.26 | 5.62 | 5.48 | 7.60 | 7.09 |

| BCAS1 | Chr20 | 53,943,540 | 54,070,765 | − | 1.72 | 0.57 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 3.30 | 3.33 |

| CILP | Chr15 | 65,195,999 | 65,211,502 | − | 1.90 | 0.84 | 1.71 | 2.00 | 3.88 | 3.59 |

| PRKG1 | Chr10 | 50,991,151 | 52,298,350 | + | 6.08 | 4.72 | 5.89 | 5.80 | 8.12 | 7.84 |

| SSPO | Chr7 | 149,776,042 | 149,833,964 | + | 2.56 | 1.14 | 2.18 | 2.55 | 5.01 | 4.03 |

| TBC1D10C | Chr11 | 67,403,913 | 67,410,090 | + | 1.03 | 0.34 | 1.01 | 1.40 | 3.80 | 2.56 |

| CACNA1E | Chr1 | 181,483,550 | 181,806,784 | + | 2.14 | 1.43 | 2.17 | 2.26 | 4.66 | 3.80 |

| FLJ16779 | Chr20 | 63,253,978 | 63,261,615 | + | 5.26 | 4.64 | 5.42 | 5.50 | 7.75 | 6.93 |

| LRRN4CL | Chr11 | 62,686,402 | 62,689,899 | − | 0.14 | 0.84 | 1.71 | 1.57 | 2.61 | 2.13 |

| CARD14 | Chr17 | 80,169,992 | 80,209,331 | + | 0.64 | 0.87 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 2.51 | 1.92 |

| PGA5 | Chr11 | 61,241,176 | 61,251,443 | + | 0.10 | 0.20 | 1.25 | 1.14 | 2.02 | 1.37 |

| ATP8A2 | Chr13 | 25,372,071 | 26,021,282 | + | 0.95 | 0.93 | 2.05 | 1.84 | 2.71 | 2.58 |

| LINC00930 | Chr15 | 92,567,818 | 92,572,263 | − | 1.26 | 1.45 | 2.41 | 2.61 | 3.46 | 3.10 |

| ABLIM3 | Chr5 | 149,141,483 | 149,260,438 | + | 0.79 | 1.30 | 1.58 | 1.71 | 3.24 | 2.32 |

| MYL5 | Chr4 | 677,922 | 682,028 | + | 0.57 | 0.98 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 2.64 | 2.15 |

| LOC102723330 | Chr11 | 17,695,267 | 17,696,939 | − | 0.54 | 0.68 | 1.47 | 1.61 | 2.94 | 2.51 |

| N4BP2L1 | Chr13 | 32,400,723 | 32,428,178 | − | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.92 | 1.71 | 2.92 | 2.77 |

| LINC00951 | Chr6 | 40,344,345 | 40,356,006 | − | 0.19 | 0.29 | 1.03 | 0.79 | 2.02 | 2.04 |

| SLC38A5 | ChrX | 48,458,537 | 48,470,256 | − | 0.43 | 0.54 | 1.13 | 1.32 | 2.33 | 1.96 |

| CCR7 | Chr17 | 40,553,770 | 40,565,484 | − | 0.61 | 0.50 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 2.45 | 2.18 |

| SRMS | Chr20 | 63,539,924 | 63,547,504 | − | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 2.12 | 1.75 |

| LOC100652768 | Chr11 | 117,195,613 | 117,201,914 | − | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.18 | 1.35 | 2.25 | 2.10 |

| TMEM178B | Chr7 | 141,074,232 | 141,480,379 | + | 0.39 | 0.10 | 1.03 | 0.89 | 2.00 | 1.89 |

| CACNA2D4 | Chr12 | 1,791,957 | 1,918,704 | − | 1.88 | 0.84 | 2.81 | 2.79 | 3.42 | 3.40 |

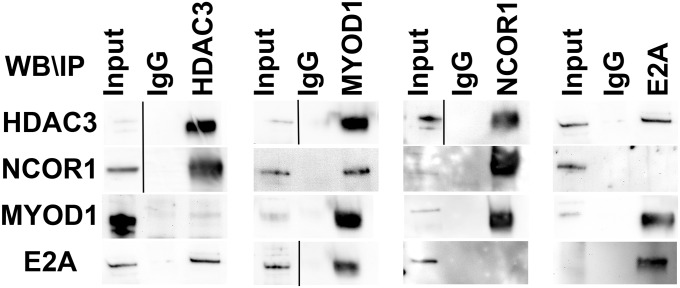

Previous studies have shown that repression of myoblast determination protein 1 (MYOD1)-driven differentiation pathways results in a characteristic arrest of RMS cells in a myoblast-like proliferative phase of development, regardless of subtype or initiating genetic events (8, 13, 14). However, even though MYOD1 dysfunction was implicated in RMS more than two decades ago (15), the precise mechanism of MYOD1 transcriptional repression remains unclear. To determine whether the NCOR/HDAC3 complex is involved in the repression of MYOD1 target genes in ERMS, we first analyzed the promoter motif of the top 500 differentially expressed genes 4 days after HDAC3 gene targeting and identified an enrichment for the E-box motif, the binding site for MYOD1, and the interacting factor T-cell factor 3 (TCF3) (also known as “E2A”) [P < 9.00E-20, false discovery rate (FDR) q <1.32E-17]. By comparing the expression levels of 137 known MYOD1 target genes (14) at 2, 4, and 10 d after HDAC3 targeting, we observed enrichment for select downstream MYOD1 target genes (P < 0.0001) 4 d and 10 d after HDAC3 knockout (Fig. 4 D and E). Using ChIP studies, we further demonstrated binding of HDAC3 to the E-box–containing regulatory regions of MYOD1 target genes, but this interaction was abrogated upon MYOD1 knockout (Fig. 4F). The same E-box regulatory regions showed increased binding for acetylated H3K9, a histone mark for transcriptionally active promoters, upon HDAC3 targeting (Fig. 4G). MYOD1 also was shown by co-IP to interact directly with E2A and the NCOR/HDAC3 complex in ERMS cells (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

MYOD1 interacts with the NCOR/HDAC3 complex. Western blot/co-IP of HDAC3, NCOR1, MYOD1, and E2A. Black line demarcates input sample from IP samples due to image realignment for data presentation. Image realignment was used for input samples that were run on separate lanes, as well as for differences in protein size between input and IP samples.

We next investigated the importance of MYOD1 in regulating myogenesis in ERMS using a dual gene-targeting strategy to disrupt MYOD1 function in HDAC3-knockout ERMS cells. 381T ERMS cells were transduced with Cas9- and MYOD1-targeting DgRNA lentivirus to establish MYOD1-knockout cells. Three days later, the MYOD1-targeted cells were transduced with HDAC3-targeting DgRNA lentivirus to produce dual MYOD1/HDAC3-knockout cells. MYOD1 targeting completely blocked the ability of ERMS cells to differentiate after HDAC3 knockout (Fig. 4H). Similar HDAC3 dual gene targeting of E2A and of the known MYOD1 coactivators CREB-binding protein (CBP) and E1A binding protein p300 (EP300) also limited the ability of HDAC3-deficient RMS cells to undergo myogenic differentiation (Fig. 4H). Taken together, these findings show that the NCOR/HDAC3 complex interacts with MYOD1/E2A and associated cofactors to repress transcriptional activation of myogenic genes.

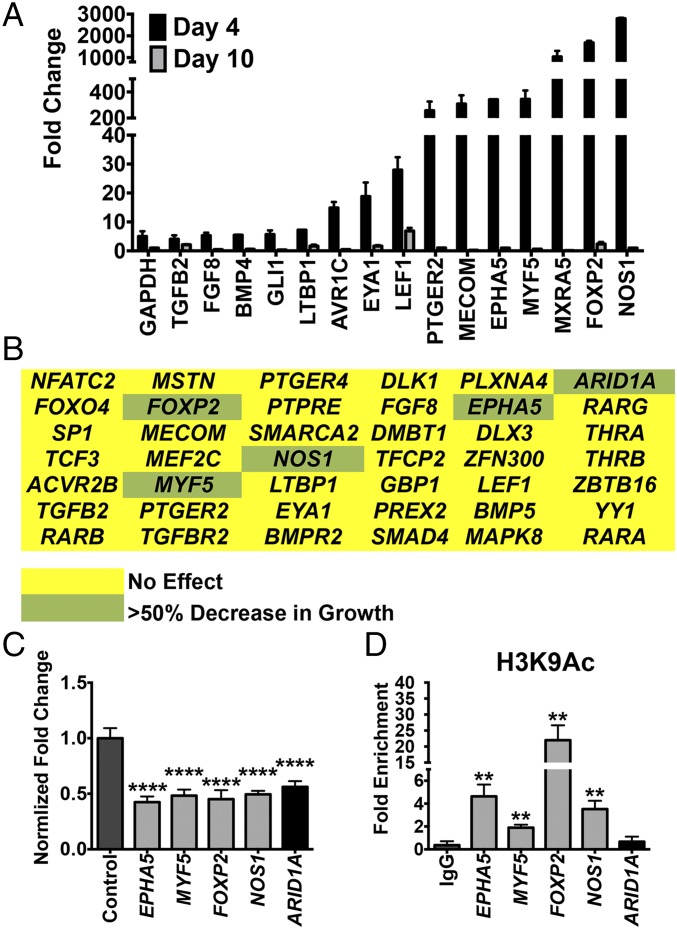

Loss of the Differentiation Block in ERMS Causes Transient Up-Regulation of Cell Growth Pathways.

In addition to the enrichment for MYOD1 target genes, pathway analysis of gene-expression changes in the early stage of HDAC3 knockout (i.e., day 4) revealed a transient up-regulation of tumor growth-promoting signaling pathways, most of which were down-regulated upon myogenic differentiation by day 10. This cellular proliferation response was mediated by growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and TGFβ, as well as epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis pathways (Fig. 5A and Table S3). We therefore performed a second CRISPR phenotypic screen in 381T ERMS cells to determine the function of 42 candidate genes with signaling or transcriptional activity linked to HDAC3 through expression-profiling or mass spectrometry studies (Fig. 5B). None of the candidate genes was able to prevent myogenic differentiation when targeted with HDAC3 in a dual gene-targeting phenotypic screen. However, independent disruption of five of the genes [ephrin type-A receptor 5 (EPHA5), myogenic factor 5 (MYF5), forkhead box P2 (FOXP2), nitric oxide synthase 1 (NOS1), and AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1 (ARID1A)] significantly decreased tumor cell growth without inducing myogenic differentiation (Fig. 5C). ChIP assays demonstrated enrichment of the acetylated histone mark H3K9ac in the promoters of MYF5, FOXP2, NOS1, and EPHA5 (Fig. 5D), suggesting that up-regulation of these genes was likely caused by altered histone landscapes in the regulatory regions.

Fig. 5.

HDAC3 targeting in ERMS cells results in transient up-regulation of growth-promoting genes. (A) Changes in gene expression of selected top differentially expressed genes at day 4 and 10 normalized to day 2 after tamoxifen-induced HDAC3 targeting. (B) Heatmap summarizing the cell growth from a CRISPR phenotypic screen targeting 42 candidate genes. Yellow: no effect; green: >50% decrease in cell growth. (C) Summary of cell growth by cell counts in RMS cells with targeted disruption of top candidate genes. Cell counts were normalized to control. Gray bars: genes identified through RNA-seq; black bars: control and ARID1A identified from mass spectrophotometry. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (D) Summary of ChIP assays showing fold enrichment of the acetyl histone mark (H3K9Ac) in the promoter region of each gene. Error bars in A, C, and D represent the mean ± SD of three technical replicates. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Table S3.

Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes (P < 0.05) in HDAC3-knockout ERMS cells

| Day 4 | Day 10 | ||

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | −log (P value) | Ingenuity canonical pathways | −log (P value) |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 3.76E00 | Calcium signaling | 7.92E00 |

| Colorectal cancer metastasis signaling | 2.85E00 | Cell Cycle Control of Chromosomal Replication | 7.04E00 |

| Bladder cancer signaling | 2.68E00 | Hepatic fibrosis/hepatic stellate cell activation | 6.22E00 |

| IGF1 signaling | 2.66E00 | Protein kinase A signaling | 6.03E00 |

| HIF1α signaling | 2.44E00 | Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling | 3.57E00 |

| HER-2 signaling in breast cancer | 2.31E00 | RhoA signaling | 3.47E00 |

| Regulation of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition pathway | 2.16E00 | nNOS signaling in neurons | 3.45E00 |

| HGF signaling | 1.94E00 | Cardiac β-adrenergic signaling | 3.16E00 |

| Mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 1.93E00 | Epithelial adherens junction signaling | 2.78E00 |

| IL-6 signaling | 1.93E00 | Gluconeogenesis I | 2.68E00 |

| TGF-β signaling | 1.84E00 | Signaling by Rho family GTPases | 2.56E00 |

| ERK/MAPK signaling | 1.8E00 | Integrin signaling | 2.35E00 |

| NF-κB signaling | 1.61E00 | Cell cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 2.27E00 |

| UVB-induced MAPK signaling | 1.59E00 | Tight junction signaling | 2.14E00 |

| BMP signaling pathway | 1.49E00 | Glycolysis I | 2.08E00 |

| Protein kinase A signaling | 1.48E00 | Salvage pathways of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotides | 1.97E00 |

| G protein-coupled receptor signaling | 1.37E00 | RhoGDI signaling | 1.91E00 |

| Basal cell carcinoma signaling | 1.27E00 | FAK signaling | 1.74E00 |

| JAK/Stat signaling | 1.27E00 | PAK signaling | 1.64E00 |

| PTEN signaling | 1.24E00 | Regulation of actin-based motility by Rho | 1.55E00 |

Discussion

In this study, we have identified HDAC3 as a major suppressor of myogenic differentiation in RMS from a high-efficiency CRISPR phenotypic screen of class I and class II HDAC genes and further characterized the HDAC3 loss-of-function phenotype in vitro and in vivo using a tamoxifen-inducible CRISPR gene-targeting strategy. HDAC3 knockout in RMS cells resulted in significant suppression of tumor growth through the activation of terminal myogenic differentiation. Interestingly, HDAC4 knockout also increased myogenic differentiation in RMS cells to a limited extent, supporting the current model that class IIa HDACs, including HDAC4, function as scaffolding molecules to recruit HDAC3 to transcriptional target sites (16). Although HDAC1 and HDAC2 have been shown to have redundant functions in muscle development (10), disruption of HDAC1 and HDAC2 did not induce any significant effect on RMS cell differentiation. However, targeting either gene did reduce overall cell proliferation to a limited extent. Our findings indicate that abnormal HDAC3 activity, rather than HDACs 1 and 2, is essential for the repression of terminal myogenic differentiation in RMS cells.

The HDAC3-knockout phenotype was recapitulated by double targeting of both NCOR1 and NCOR2, demonstrating that HDAC3 blocks myogenic differentiation in RMS through the NCOR/HDAC3 transcriptional repressor complex. The NCOR complex was originally identified as transcriptional corepressors of nuclear receptors, e.g., thyroid hormone receptor and retinoid acid receptor (17). The association of HDAC3 and the NCOR complex has been shown to be essential for the regulation of circadian and metabolic physiology, muscle physiology, and genomic stability (3, 18, 19). HDAC3 binds to the NCOR complex through the deacetylase-activating domain (DAD), which activates HDAC3 deacetylase activity (11, 12). In agreement with these findings, we demonstrated through structure function analysis that the interaction of HDAC3 with the NCOR complex is required for functional deacetylase activity and NCOR/HDAC3-mediated repression of myogenic differentiation in RMS. Of note, the antitumor effects elicited by the treatment of RMS cells with the HDAC3-selective inhibitor RGFP966 were not as robust as the loss-of-function phenotype generated by CRISPR-mediated HDAC3 knockout. Although RGFP966 inhibits histone deacetylase activity, the substrate range and mechanism of action underlying RGFP966 remain unclear. Our findings suggest that screening drug candidates for NCOR/HDAC3 complex specificity rather than for deacetylase activity may improve the therapeutic efficacy of HDAC inhibitors for RMS and other solid tumors with dysregulated HDAC3 activity.

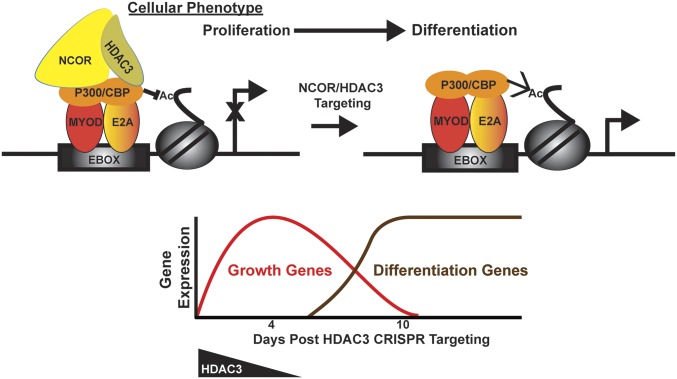

ERMS and ARMS share pathologic features of myogenic differentiation arrest characterized by defects in the MYOD1-mediated transcriptional program (8, 13–15). Previous studies in the ERMS RD cell line have shown that competitive binding of MYOD1 by inhibitory factors such as musculin and other altered E-box transcription factors, as well as repression of transcription by the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), can contribute to blocking the differentiation of tumor cells (20, 21). However, the common mechanism blocking the differentiation in RMS remains unknown. Here we demonstrate that both ERMS and ARMS subtypes undergo extensive myogenic differentiation from CRISPR targeting of either HDAC3 or combined NCOR1 and NCOR2 knockout. Nuclear HDAC3 is present in proliferating myoblasts as well as in RMS cells but is down-regulated in differentiated skeletal muscle, supporting a role for HDAC3 in undifferentiated myogenic cells. Furthermore, the NCOR/HDAC3 complex interacts with MYOD1 and associated cofactors to repress the transcriptional activation of myogenic genes. Although the initiating genetic events in ERMS and ARMS are unique, our findings suggest that the driving mechanisms of both RMS subtypes converge on the NCOR/HDAC3 complex as one of the common mechanisms for repressing MYOD1-mediated myogenic differentiation, in turn promoting uncontrolled proliferation of myoblast-like cells (Fig. 6). Although our data suggest that the NCOR/HDAC3 complex is critical to suppressing myogenic differentiation in RMS, the molecular pathways or genetic alterations leading to dysregulation of NCOR/HDAC3 activity in RMS remain to be elucidated.

Fig. 6.

(Upper) Proposed mechanism of NCOR/HDAC3-mediated transcriptional repression of myogenic differentiation in RMS. The NCOR/HDAC3 complex represses MYOD1/E2A-mediated transcription in RMS to block myogenic differentiation. Upon HDAC3 targeting, the MYOD1/E2A transcriptional-activating complex including CBP and P300 can initiate the myogenic program. (Lower) A transient up-regulation of tumor-promoting genes occurs before RMS tumor cells are completely switched to a terminal differentiation state.

The goal of differentiation therapy in cancer is to reactivate the endogenous differentiation program with concomitant loss of tumor cell phenotypes (22). We have demonstrated by phenotypic characterization and expression-profiling studies that targeted disruption of the NCOR/HDAC3 complex by CRISPR is sufficient to switch RMS cells from a neoplastic state to a terminally differentiated muscle state, indicating the feasibility and potential efficacy of differentiation therapy in RMS. Surprisingly, targeting HDAC3 in ERMS cells also resulted in a transient but robust up-regulation of oncogenic genes and pathways including IGF, HGF, and MAPK signaling pathways before the completion of terminal differentiation (Fig. 6). In our CRISPR screen of 42 additional candidate genes linked to HDAC3 function, we have identified FOXP2, EPHA5, NOS1, or ARID1A as essential genes for RMS tumor growth. Recurrent mutations in FOXP2 and ARID1A and a differential methylation pattern of NOS1 have been shown in RMS (8, 23). These studies along with our loss-of-function studies indicate the important roles of these genes in RMS pathogenesis. Based on the hyperacetylated status of histone H3 in the promoter regions of MYF5, FOXP2, EPHA5, and NOS1, a subset of genes with oncogenic function likely undergoes transient activation upon HDAC3 loss of function. The transient up-regulation of tumor-promoting genes could represent either direct de-repression of the transcription block by the HDAC3 repressor complex or a secondary adaptive response as tumor cells transition from a neoplastic state to a terminally differentiated state. The implication of our findings for differentiation therapy is that incomplete induction of differentiation may not be sufficient to counteract continued growth of tumor cells because of the transient up-regulation of oncogenic genes and pathways (Fig. 6).

Our study demonstrated that genome-engineering technology could be used to induce large-scale differentiation of cancer cells where direct chemical inhibitors have proven ineffective. Knockout of the NCOR/HDAC3 complex revealed a significant vulnerability of RMS cells to targeted disruption of factors blocking differentiation. This effect was observed in both RMS subtypes (ARMS and ERMS), suggesting that there are common pathways restricting differentiation of tumor cells with similar tissue lineage regardless of initiating oncogenic events. Because pan-HDAC inhibitors have shown disappointing results in clinical trials of solid tumors, the development of new targeted therapies with increased selectivity to specific HDACs or interacting repressor complexes may improve treatment of certain cancer types in which current pan-HDAC inhibitors have previously failed.

Methods

Animal studies were approved by the University of Washington Subcommittee on Research Animal Care under protocol no. 4330-01_SC_v19. Archived paraffin tissue blocks for human RMS tumor samples were obtained under an approved human Internal Review Board protocol 14988 at Seattle Children’s Hospital/University of Washington. Additional RMS tissue microarrays were obtained from US Biomax, Inc.

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Targeting.

Rapid single and multiplex gene knockout was accomplished by treating RMS cells with multiple lentiviral particles containing separate DgRNA-targeting and Cas9-expressing viruses. Lentiviral-transduced RMS cells were split into specific experiments 3 d postinfection and were analyzed 7 d later without antibiotic selection or isolation of clonal cells. Each DgRNA-targeting viral vector contained dual gRNAs targeting conserved exons of each gene. All DgRNAs were cloned into the CRISPR plasmids using a one-step Gibson reaction.

CRISPR/Cas9-inducible cells were created using PiggyBac transposition. Stable cell lines were integrated with an all-in-one construct containing DgRNAs and expressing an ERT2-Cas9-ERT2 fusion protein for tamoxifen-inducible gene targeting. Inducible gene targeting in vitro was accomplished by treating ERMS cells for 3 d with 2 µM 4-hydroxytamoxifen. For structure–function studies, HDAC3-inducible cells were transduced with constructs overexpressing either WT or mutant CRISPR/Cas9-resistant HDAC3 linked to a T2A-GFP cassette. Cells were sorted for GFP fluorescence, and then endogenous HDAC3 was targeted with tamoxifen treatment.

In vivo CRISPR-inducible tumor xenografts were created by injecting NSG immunocompromised mice with tamoxifen-inducible cells targeting either a safe-harbor region of the genome or HDAC3. After tumor development, the mice were treated with five injections of 100 mg/kg tamoxifen to induce in vivo gene targeting. Targeting efficiency was validated from both in vitro and in vivo experiments using either a T7 endonuclease assay to examine targeting efficiency at individual gRNA target sites or PCR to look for genomic deletions between both gRNAs.

Cellular Assays.

RMS cell growth was quantified by direct cell counting. Analysis of RMS differentiation was determined with IHC by fixing treated cells with 2% paraformaldehyde followed by MF20 immunostaining. Stained cultures were imaged and quantified for the percent of MF20+ cells. An annexin V flow cytometry-based assay was used to analyze apoptosis. To assess HDAC3 deacetylase activity, a nuclear extract kit (Active Motif, catalog no. 40010) was used to obtain nuclear extracts from HDAC3-knockout 381T cells overexpressing the CRISPR-resistant HDAC3 mutants at 4 d post targeting. HDAC3 (WT or mutant) was immunoprecipitated from nuclear extracts, and HDAC deacetylase activity was quantified using a fluorescent HDAC activity assay kit (Active Motif, catalog no. 56200), which uses a short peptide substrate that contains an acetylated lysine residue that can be deacetylated by class I, IIB, and IV HDAC enzymes.

Co-IP.

Co-IP of HDAC3 or NCOR1 was performed using the nuclear complex co-IP kit (Active Motif, catalog no. 54001). Two hundred micrograms of extract and 2 μg of antibody were used. Dynabead protein G (Life Technologies, catalog no. 10003D) was used to capture the protein/antibody complex.

All quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) primer pairs and ChIP primer pairs are listed in Table S4.

Table S4.

Primers used in qPCR and ChIP PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| Primers used in qPCR | ||

| AVR1C | TAGCATGACTGATGCCCAAC | CAGGCTCTCCTGCTGCTC |

| BMP4 | GCATTCGGTTACCAGGAATC | TGAGCCTTTCCAGCAAGTTT |

| CKM | TACTTCCCTTTGAACTCGCC | AGCATCAAGGGCTACACGTT |

| EPHA5 | TGTGAGGTGGACATTTGCC | CATGTGCAAGGCAGGATATG |

| EYA1 | ATGTGCTTAGGTCCTGTCCG | GACTGCGAATGGAAGAAATGA |

| F13A1 | CCCCCACTTTCCACTTTGTA | CGTCCATATGACCCCAGAAG |

| FGF8 | CTCTGCTTCCAAAGGTGTCC | TACCAACTCTACAGCCGCAC |

| FOXP2 | AGTTGTCTTGCTGCCTGGAG | GCAGCAGAGATGGAAGATCA |

| FST | ACTCCTCCTTGCTCAGTTCG | TCTGCCAGTTCATGGAGGAC |

| GBP1 | GCAGAACTAGGATGTGGCCT | AACAAGCTGGCTGGAAAGAA |

| GBP2 | GCAAGTTGATCTCTGGAGCC | GCCAAACTCGGAAGAAAAGA |

| HSPB8 | TGCAGGAAGCTGGATTTTCT | AGCCAGAGGAGTTGATGGTG |

| LEF1 | CACTGTAAGTGATGAGGGGG | TGGATCTCTTTCTCCACCCA |

| LTBP1 | GCTCTCCTGAAATCCCCTTC | CTCCCCCAGCAGATACATTC |

| MECOM | AAACTCGAAAGCGAGAATGATCT | TGGTGGCGAATTAAATTGGACTT |

| MXRA5 | CCTTGTGCCTGCTACGTCC | TTGGTCAGTCCTGCAAATGAG |

| MYF5 | TCAGGACAGTAGATGCTGTCAAA | CACCTCCAACTGCTCTGATG |

| MYH2 | GGTTCGTGGTAATCAGAAGCA | TCCAGCTTAAGGCTGAGAGAA |

| MYH8 | GTGTTCACAGTCTTTCCGGC | CCCCACATCTTCTCCATCTC |

| NOS1 | ACCATATTCCCCCAGAGGAC | GAAGAGCTCAGGGTCATTGC |

| PTGER2 | AAGAGCTTGGAGGTCCCATT | CAGGCTCTCCTGCTGCTC |

| RUNX1 | CAATGGATCCCAGGTATTGG | CACTGCCTTTAACCCTCAGC |

| RUNX2 | CCTAAATCACTGAGGCGGTC | CAGTAGATGGACCTCGGGAA |

| SLN | ATTTCTGAGGGCACACCAAG | GGAGGGAGAAGGAGTTGGAG |

| SSPN | TACATGTCCGTTCGTCAACC | TCAGCTCCTCCCTGCTAGTC |

| TGFB2 | CTCCATTGCTGAGACGTCAA | ATAGACATGCCGCCCTTCTT |

| TNNC1 | CAGCTCCTTGGTGCTGATG | GGATGACATCTACAAGGCTGC |

| Primers used in ChIP PCR | ||

| CKM | CGCCGGGAAAGGAGTTATTT | CCGAGACGCCCGGTTATAAT |

| RUNX1 | TTGCCCTTTGTCCTCTCTGT | CTGGATGAGGACTGAGGCTG |

| HSPB8 | TAGCAACCACCCATCTTCGA | AGTCCAGGAGTCAGAGGGAT |

| SSPN | GAGCAGGAGAAAGAGAGGGG | TGCCTCACCAAGTTCAGGAA |

| MYH8 | CGGCAACATACTGTCCAGGT | GGCAAGTCAAATCCAACAACG |

| TNNC1 | CTGGAGGAGGCAGGCTATTT | GTTTCATCAGGGGCCGAAAG |

| MYH2 | GGAGGTTGCAGTGAACCAAG | TGAAACGTCAGTCTCCCCTC |

| GBP1 | GGTTCATTTGGTTTGCAGGC | CCAGCTGAATCACTGAATCCC |

Detailed experimental procedures are described in SI Methods.

SI Methods

CRISPR Phenotypic Screen.

The CRISPR/Cas9+ phenotypic screens used in this study used two lentiviral constructs, one containing the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) nuclease and the other driving expression of DgRNAs targeting conserved exons of each target gene. The 18- to 20-bp gRNAs were designed using online CRISPR gRNA design tools (Zfit or ChopChop). Cultured RMS cells were treated with equal portions of Cas9 and DgRNA lentiviral supernatants in medium containing 30 ng/mL Polybrene (Thermo Fisher Scientific). High lentiviral transduction efficiency was validated visually with RFP fluorescence expressed by the DgRNA viral construct. Targeting was allowed to proceed for 3 d; then transduced RMS cells were plated for biological assays including cell counts, MF20, IF, and Annexin V assays (see below) without stable selection. Multiple genes (e.g., NCOR1 and NCOR2) were targeted simultaneously by transducing the cells with an additional viral supernatant. For all experiments involving the sequential targeting of both target genes and HDAC3, the cells were first transduced with Cas9 and gene-specific DgRNA lentiviruses followed by a second transduction 3 d later with an HDAC3 DgRNA lentivirus. All experimental screens were carried out over 10 d to allow enough time for the full manifestation of any phenotype without clonal expansion of the small numbers of nontargeted cells.

DNA Constructs.

Lentiviral DgRNA constructs derived from the plentiCRISPR-v1 plasmid (Addgene no. 49535) were created by removing the SpCas9 coding sequence (CDS) and replacing it with the TagRFPt CDS (plenti-US-TagRFPt). The Cas9 lentiviral construct was similarly produced from plentiCRISPR-v1 plasmid by removing the U6-single guide RNA (sgRNA) cassette.

The HDAC3 overexpression constructs were created by cloning the full-length HDAC3 CDS amplified from 381T ERMS cells into a T2A-emGFP–linked lentiviral construct. Silent mutations then were introduced into the seed region of each of the HDAC3 gRNA target sites using site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 3G) to produce a CRISPR/Cas9-resistant HDAC3 (HDAC3m) CDS. The HDAC3 ΔB12 and Y298F mutants were created similarly using Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs) or site-directed mutagenesis to introduce deletions (base pairs 136–183 and 337–369, amino acids 46–61 and 113–123) or a point mutation (A893T) into the HDAC3 CDS.

To clone the tamoxifen-inducible Cas9-ERT2 construct, the U6-sgRNA cassette (derived from pX459, Addgene catalog no. 48139) was first inserted into a plasmid backbone containing PiggyBac transposon terminal repeats (System Biosciences). PCR-amplified cloning fragments coding for the elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1a) promoter, two mutant estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains (ERT2), and the SpCas9 nuclease were subsequently inserted into the sgRNA-PiggyBac plasmid using Gibson assembly with the two ERT2 domains flanking the SpCas9 CDS to create an ERT2-Cas9-ERT2 fusion protein. A T2A-puromycin selection cassette was inserted downstream of the ERT2-Cas9-ERT2 fusion gene to enable stable selection.

Gibson assembly was used to insert both gRNAs into each CRISPR targeting construct simultaneously. We did so by first cloning two U6-sgRNA cassettes in tandem to use as the template for PCR amplification of each DgRNA fragment. This DgRNA template plasmid was then amplified from the first scaffold through the second U6 promoter using unique primers containing both target gRNA sequences flanked on the 5′ end by 13-bp Gibson homology arms (HA) matching either the U6 (forward primer) or scaffold (reverse primer) sequences (PCR product: U6HA-gRNA1-scaffold-U6-gRNA2-ScaffoldHA). The DgRNA amplicon specific to each target gene then was gel purified and cloned directly into the U6-sgRNA cassette of the desired CRISPR construct.

All constructs were sequenced in detail (Genewiz) before use, and all relevant plasmids can be found on Addgene for open distribution.

Validation of CRISPR Targeting.

Gene targeting was validated using either a T7 endonuclease assay to visualize targeting efficiency at each gRNA target site or by detecting genomic DNA deletions between each of the DgRNAs. T7 endonuclease assays were performed on PCR amplicons from each gRNA target site using the manufacturer’s protocols (New England BioLabs). Endonuclease digests were quantified from digital images by analyzing the band strength of each of the digested products to determine the frequency of indel occurrence.

Deletion mutations were analyzed by PCR amplifying the region of the genome that spanned the DgRNA target sites. Because most gRNAs targeted genomic regions that were between 5 and 7 kb apart, the PCR deletion products form only in the presence of genomic DNA deletions. Deletion PCR products were semiquantified by comparing the band intensity of the deleted PCR product with that of a loading PCR control from an intact portion of the genome:

Because deletion products occurred at high efficiency (∼40–50%), were unambiguous, and were simple to analyze, they were used to confirm CRISPR targeting for many experiments in which exact targeting efficiency was irrelevant to the results.

Cell Culture.

The ERMS cell line 381T [a derivative of the RD RMS cell line; TE 381.T (RD114-B), ATCC CRL-7763] was used as the primary cell-culture model in this study and was validated by direct sequencing of the NRAS A183T (Q61H) mutation characteristic to this specific cell line. Each RMS cell line was validated to be free from mycoplasma contamination before experimentation. The myogenic differentiation of RMS cells resulting from HDAC3 knockout was independent of serum level; therefore most experiments cultured RMS cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (37 °C with 5% CO2).

Tamoxifen-inducible Cas9-ERT2 cells were produced by transfecting 381T ERMS cells with both a gene targeting Cas9-ERT2-Puro PiggyBac transposon plasmid and a PiggyBac transposase plasmid (System Biosciences) at a ratio of 2.5:1. The cells were transfected with a total of 7 µg of DNA (5 µg transposon and 2 µg transposase) using the Neon electroporation system (Life Technologies) with two 30-ms pulses at 1,150 V. Three days after transfection, the cells were placed under puromycin selection, and all resulting colonies were pooled to maintain cell line heterogeneity. HDAC3 or the safe-harbor control knockout was induced by treating the cells daily for 3 d with 2 µM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) and then switching the cells to low-serum medium (2% horse serum) 1 d after tamoxifen treatment. Overexpression of the HDAC3 mutant (ΔB12 and Y298F) proteins was achieved by transducing inducible HDAC3-knockout cells with lentiviral expression constructs. Transduced cells then were sorted for GFP expression by FACS before tamoxifen-induced gene targeting.

Cellular Assays.

Cell counts were used to quantify cell growth accurately in differentiating myogenic RMS cells. Briefly, targeted cells were plated at equal density in replicate wells and were allowed to grow for a total of 7 d. Then each well was trypsinized and counted on a Cellometer Mini (Nexcelom Biosciences). Apoptosis was assessed using an Annexin V flow cytometry-based assay according to manufacturer’s protocols (Annexin V, Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate; Thermo Fisher Scientific). A stable 381T cell line harboring tamoxifen-inducible HDAC3 CRISPR/Cas9 was transduced with a lentiviral expression vector with an EF1α promoter driving constitutive overexpression of Cas9-resistant modified WT HDAC3, mutant HDAC3 (ΔB12), or mutant HDAC3 (Y298F) with GFP as the selectable marker. Four days after transduction, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS. To assess HDAC activity, nuclear extract was prepared using the Active Motif’s Nuclear Extract Kit (catalog no. 40010). HDAC3 (WT or mutant) was immunoprecipitated from nuclear extracts, and HDAC deacetylase activity was quantified using a fluorescent HDAC activity assay kit (Active Motif, catalog no. 56200), which uses a short peptide substrate that contains an acetylated lysine residue that can be deacetylated by Class I, IIB and IV HDAC enzymes.

Human Xenografts.

Animal studies were approved by the University of Washington Subcommittee on Research Animal Care under protocol no. 4330-01_SC_v19. To establish xenografts in immunocompromised NSG mice, ∼5 × 106 tamoxifen-inducible (Cas9-ERT2) 381T cells from either the safe-harbor or HDAC3-targeting cell line were resuspended in Matrigel and injected s.c. into the flanks of each 6- to 7-wk-old anesthetized mouse. Each mouse received bilateral xenografts (HDAC3 and control) to ensure that all xenografts underwent the same experimental conditions. After injection of the cells, animals were monitored every 3–4 d to detect tumor formation (∼3–4 wk postinjection). At tumor onset, five i.p. tamoxifen injections (100 mg/kg per mouse) were administered over 10 d to induce gene targeting in vivo. Tumor size was measured by caliper every 3–4 d at tumor onset until 3 wk after tamoxifen induction. At the end of the experiment, all mice were humanely killed for tumor tissue harvesting.

Histology, IHC, and Immunocytochemistry.

Archived paraffin tissue blocks for human RMS tumor samples were obtained under approved human Internal Review Board protocol 14988 at Seattle Children’s Hospital/University of Washington. Additional RMS tissue microarrays were obtained from US Biomax, Inc. H&E staining and IHC for paraffin tissue sections were performed at the Histology and Imaging Core Facility at University of Washington. The following antibodies including dilutions were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-human cleaved caspase 3 (1:100; Biocare Medical, catalog no. CP229B), mouse monoclonal anti-human Ki-67 (1:100; clone: MIB1, Dako, catalog no. M7240), mouse monoclonal anti-human myosin heavy chain (1:100; clone: MF20, catalog no. MAB4470, R&D Systems), and rabbit polyclonal anti-human HDAC3 (1:100; Abcam, catalog no. ab7030).

For HDAC3 (1:500; Abcam), NCOR1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500; Abcam, catalog number ab24552), and MF20 (1:200; R&D) immunofluorescent staining, cultured cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The cells then were washed in PBS, permeabilized (0.2% TritonX-100, 5 min), blocked (5% BSA, 0.001% TritonX-100, 1 h), and incubated with primary (1 h) and secondary antibodies (1:2,000; 1 h). Cell nuclei were subsequently stained with DAPI (10 µg/mL), and the cells were imaged on an EVOS FL digital inverted fluorescence microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Co-IP and Western Blots.

Co-IP was performed using the nuclear complex co-IP kit (Active Motif). A total of 200–300 μg of nuclear extract was used for co-IP using 1–2 µg of mouse monoclonal HDAC3 (Active Motif), rabbit polyclonal NCOR1 (Abcam), rabbit polyclonal MYOD1 (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse monoclonal antibody against TCF3 (G9, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Coimmunoprecipitated products were detected using Western blots with antibodies against HDAC3 (1:1,000), NCOR1 (1:1,000), NCOR2 (1:1,000; rabbit polyclonal, Abcam, ab24551), and TCF3 (1:200).

Mass Spectrometry.

The HDAC3 coimmunoprecipitated products (see above) were run on an SDS/PAGE gel and stained with PageBlue (Thermo Scientific). Visible bands were cut out and sent for tandem mass spectrometry for protein identification at the Proteomics Core Facility at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Briefly, desalted peptide samples were brought up in 2% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid (20 µL) and analyzed (18 µL) by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization MS/MS with a Thermo Scientific Easy-nLC II (Thermo Scientific) nano HPLC system coupled to a hybrid Orbitrap Elite ETD (Thermo Scientific) mass spectrometer. Data analysis was performed using Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (Thermo Scientific). The data were searched against a UniProt Human database that included common contaminants. The searches were performed corresponding to the proteolytic enzyme trypsin. The maximum missed cleavages setting was set to 2. The precursor ion tolerance was set to 10 ppm, and the fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.8 Da. Variable modifications included oxidation on methionine (+15.995 Da) and carbamidomethyl (57.021). Sequest HT was used for database searching and Percolator was used for scoring.

Gene Expression and RNA Profiling.

For RNA profiling, total RNA was harvested from the 381T stable cell line harboring either the tamoxifen-inducible CRISPR HDAC3 DgRNA or a safe-harbor control DgRNA expression construct treated with or without tamoxifen at day 2, 4, and 10 after tamoxifen induction. Two biological replicates for each time point were obtained. The total RNA was prepared using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 with poly-A selection. All libraries were individually barcoded, pooled, and sequenced over three lanes of a Rapid Run 50PE. The final fragment size was ∼420 bp; insert size was then ∼300 bp after subtracting the 120-bp adapters. Reads failing the Illumina base-call quality assessment were removed. Reads then were aligned with the GSNAP software to the hg38 reference, and mapped reads were counted at the gene level with the htseq-count application. The Bioconductor/R package edgeR was used to estimate differential expression between no-tamoxifen and tamoxifen-treated samples at each time point and to calculate P values for assessment of statistical significance between groups. Heatmaps and dendrograms comparing expression across time points were generated using the R gplots package. Pathway analysis was performed using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. Select differentially expressed genes were validated using RT-qPCR as previously described (9). All RT-qPCR primer pairs are listed in Table S4.

ChIP.

ChIP was performed as previously described (9). One microgram of antibody against H3K9 acetylated histone (Active Motif) or against HDAC3 (Abcam) was used for chromatin extracted per million cells harvested. All ChIP primer pairs are listed in Table S4.

Statistics and Data Reporting.

Statistical differences between treatment groups were analyzed with either t tests or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests and correction to the P value depending on the number of statistical comparisons (Prism 6, GraphPad). The numbers of biological or technical replicates are reported in the figure legends. Data are presented as mean ± SD with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Histology and Imaging Core at University of Washington and the Genomics Resource at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in particular Jerry Davison; Jessica Gianopulos (an undergraduate research assistant at University of Washington) for her valuable work validating CRISPR targeting efficiency; and Dr. Michael Dyer (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital) and Dr. Myron Ignatius (Massachusetts General Hospital) for comments and suggestions for the manuscript. The laboratory of Dr. Ray Monnat (University of Washington) identified and characterized the safe-harbor genomic locus used for control CRISPR-targeting constructs. This work was supported by NIH Grants K08AR063165 and R01CA196882 (to E.Y.C.), a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Scholar Award (to E.Y.C.), the Rally Foundation (E.Y.C.), and the Sarcoma Foundation of America (E.Y.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1610270114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Piekarz RL, Bates SE. Epigenetic modifiers: Basic understanding and clinical development. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(12):3918–3926. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West AC, Johnstone RW. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):30–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI69738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhaskara S, et al. Hdac3 is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santoro F, et al. A dual role for Hdac1: Oncosuppressor in tumorigenesis, oncogene in tumor maintenance. Blood. 2013;121(17):3459–3468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-461988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen EA, et al. Phase IIb multicenter trial of vorinostat in patients with persistent, progressive, or treatment refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3109–3115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cote GM, Choy E. Role of epigenetic modulation for the treatment of sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14(3):454–464. doi: 10.1007/s11864-013-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller C, Guttridge DC. Mechanisms of impaired differentiation in rhabdomyosarcoma. FEBS J. 2013;280(17):4323–4334. doi: 10.1111/febs.12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shern JF, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(2):216–231. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vleeshouwer-Neumann T, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors antagonize distinct pathways to suppress tumorigenesis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery RL, et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes Dev. 2007;21(14):1790–1802. doi: 10.1101/gad.1563807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Z, et al. Deacetylase-independent function of HDAC3 in transcription and metabolism requires nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2013;52(6):769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You S-H, et al. Nuclear receptor co-repressors are required for the histone-deacetylase activity of HDAC3 in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):182–187. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao L, et al. Genome-wide identification of PAX3-FKHR binding sites in rhabdomyosarcoma reveals candidate target genes important for development and cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(16):6497–6508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacQuarrie KL, et al. Comparison of genome-wide binding of MyoD in normal human myogenic cells and rhabdomyosarcomas identifies regional and local suppression of promyogenic transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(4):773–784. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00916-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tapscott SJ, Thayer MJ, Weintraub H. Deficiency in rhabdomyosarcomas of a factor required for MyoD activity and myogenesis. Science. 1993;259(5100):1450–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.8383879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischle W, et al. Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol Cell. 2002;9(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baniahmad A, Tsai SY, O’Malley BW, Tsai MJ. Kindred S thyroid hormone receptor is an active and constitutive silencer and a repressor for thyroid hormone and retinoic acid responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(22):10633–10637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alenghat T, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature. 2008;456(7224):997–1000. doi: 10.1038/nature07541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto H, et al. NCoR1 is a conserved physiological modulator of muscle mass and oxidative function. Cell. 2011;147(4):827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchesi I, Fiorentino FP, Rizzolio F, Giordano A, Bagella L. The ablation of EZH2 uncovers its crucial role in rhabdomyosarcoma formation. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(20):3828–3836. doi: 10.4161/cc.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, et al. MyoD and E-protein heterodimers switch rhabdomyosarcoma cells from an arrested myoblast phase to a differentiated state. Genes Dev. 2009;23(6):694–707. doi: 10.1101/gad.1765109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz FD, Matushansky I. Solid tumor differentiation therapy - is it possible? Oncotarget. 2012;3(5):559–567. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]