Significance

How bacteria regulate cell division to achieve cell size homeostasis, with concomitant coordination of DNA replication, is a fundamental question. Currently, there exist several competing models for cell cycle regulation in Escherichia coli. We performed experiments where we systematically perturbed cell dimensions and found that average cell volume scales exponentially with the product of the growth rate and the time from initiation of DNA replication to the corresponding cell division. Our data support a model in which cells initiate replication on average at a constant volume per origin and divide a constant time thereafter.

Keywords: cell cycle, cell growth, E. coli, DNA replication, cell dimension

Abstract

Bacteria tightly regulate and coordinate the various events in their cell cycles to duplicate themselves accurately and to control their cell sizes. Growth of Escherichia coli, in particular, follows a relation known as Schaechter’s growth law. This law says that the average cell volume scales exponentially with growth rate, with a scaling exponent equal to the time from initiation of a round of DNA replication to the cell division at which the corresponding sister chromosomes segregate. Here, we sought to test the robustness of the growth law to systematic perturbations in cell dimensions achieved by varying the expression levels of mreB and ftsZ. We found that decreasing the mreB level resulted in increased cell width, with little change in cell length, whereas decreasing the ftsZ level resulted in increased cell length. Furthermore, the time from replication termination to cell division increased with the perturbed dimension in both cases. Moreover, the growth law remained valid over a range of growth conditions and dimension perturbations. The growth law can be quantitatively interpreted as a consequence of a tight coupling of cell division to replication initiation. Thus, its robustness to perturbations in cell dimensions strongly supports models in which the timing of replication initiation governs that of cell division, and cell volume is the key phenomenological variable governing the timing of replication initiation. These conclusions are discussed in the context of our recently proposed “adder-per-origin” model, in which cells add a constant volume per origin between initiations and divide a constant time after initiation.

Bacteria can regulate tightly and coordinate the various events in their cell cycles to accurately duplicate their genomes and to homeostatically regulate their cell sizes. This is a particular challenge under fast growth conditions where cells are undergoing multiple concurrent rounds of DNA replication. Despite much progress, we still have an incomplete understanding of the processes that coordinate DNA replication, cell growth, and cell division. This lack of understanding is manifested, for instance, in discrepancies among various recent studies that propose different models for control of cell division in the bacterium Escherichia coli.

One class of models suggests that cell division is triggered by the accumulation of a constant size (e.g., volume, length, or surface area) between birth and division (1–3). Such models are supported by experiments measuring correlations between cell size at birth and cell size at division, which showed that, when averaged over all cells of a given birth size , cell size at division approximately follows

| [1] |

where the constant sets the average cell size at birth. This is known as the “incremental” or “adder” model, and cells following this behavior are said to exhibit “adder correlations” (1–7). Importantly, these models postulate that cell division is governed by a phenomenological size variable, with no explicit reference to DNA replication.

A second class of models for control of cell division postulates that cell division is governed by the process of DNA replication, which can be described as follows. The time from a replication initiation event to the cell division that segregates the corresponding sister chromosomes can be split into the period, from initiation to termination of replication, and the period, from termination of replication to cell division (8, 9). Both the and periods remain constant at ∼40 min and 20 min, respectively, for cells grown in various growth media supporting a range of doubling times between 20 min and 60 min (10, 11). We refer to growth rates within this range as fast. All experiments described here are carried out under such fast growth conditions. Note that is ∼60 min and larger than the time between divisions at fast growth. This situation is achieved by the occurrence of multiple ongoing rounds of replication. That is, under these conditions, a cell initiates a round of replication simultaneously at multiple origins that ultimately give rise to the chromosomes of their granddaughters or even great-granddaughters (12). Extending the basic definition of the and periods, Cooper and Helmstetter specifically proposed that an initiation event triggers a division after a time , thereby ensuring that cells divide only after the completion of a round of DNA replication (8, 10). This Cooper–Helmstetter (CH) formulation, hereafter the CH model, belongs to the second class of models for control of cell division.

The CH model is supported by the phenomenon of rate maintenance (13): After a change from one growth medium to a richer one (a shift up), cells continue to divide at the rate associated with the poorer medium for a period of 60 min. According to the CH model, in which division is triggered by initiation, all cells that have already initiated replication before a shift up will have also already committed to their ensuing divisions, and thus the rate of division will remain unchanged for a time following a shift up.

The same value of 60 min also emerged in a seemingly different context a decade earlier, in the seminal study of Schaechter et al. (14). In their work, cell volumes, averaged over an exponentially growing population, were measured for culture growing under dozens of different growth media supporting fast growth. It was found that average cell volume was well described by an exponential relation with growth rate , where is the average cell volume, is a constant with dimensions of volume, is the growth rate, is the doubling time, and min.

Donachie (15) showed that this exponential scaling of average cell volume with growth rate can also be explained by the CH model if it is further assumed that cells initiate replication on average at a constant volume per origin of replication at initiation. Because cells grow exponentially at the single-cell level (16), cells will then divide on average at a volume per origin times a scaling factor . The average cell volume then follows

| [2] |

with , because the cell volume averaged over an exponentially growing population is the average cell volume at birth times (17). In Schaechter’s experiments, the and periods were approximately constant, giving rise to the exponential scaling observed. However, the derivation for Eq. 2 holds regardless of the values of the and periods, and in cases where they are not constant, average cell volume is not expected to scale exponentially with growth rate. Eq. 2 is known as Schaechter’s growth law, but is referred to simply as the growth law for the rest of this paper.

Recent single-cell analyses found that cells indeed initiate replication on average at a constant volume per origin or per some locus close to the origin (11). Although further experiments are required, the fact that introduction of an origin onto a plasmid does not affect cell cycle timings or cell size suggests that the latter possibility is correct (11, 18, 19) (SI Text, Average Cell Volume at Initiation Is Constant per Some Locus Close to the Origin). Below, for simplicity, we use the phrase “per origin,” while keeping this complexity in mind.

Clearly, the two classes of models for control of cell division differ fundamentally. In the first class, division depends only on the accumulation of size from birth, and DNA replication plays no explicit role. In the second class, division is downstream of the preceding initiation of DNA replication. Importantly, also, the experiments leading to the first class of models defined cell size differences by measuring cell length. Because for a constant growth environment the widths of bacterial cells are very narrowly distributed with a coefficient of variation (CV) less than (2), these analyses cannot distinguish whether cell size in a given environment is set by a constant volume, surface area, or length. This ambiguity raises the question of what is the key phenomenological variable governing cell cycle progression.

Here, we sought to test these models by perturbing cell dimensions in E. coli and assaying the effects of those perturbations on both replication events and cell division. In our study, shape perturbations were achieved by systematically varying expression levels of the protein MreB, an actin homologue involved in cell wall synthesis, and the protein FtsZ, a tubulin homologue involved in the formation of the division septum (20, 21). Our approach is indicated schematically in Fig. 1A. It extends and complements Schaechter’s experiments, in which growth rate was perturbed, and is reminiscent of the work of Harris et al. (3), in which cell dimensions were perturbed, but with the important addition to both studies that we also measured the cell cycle periods and because they play an important role in the CH model. For this paper, we define division as completion of septation.

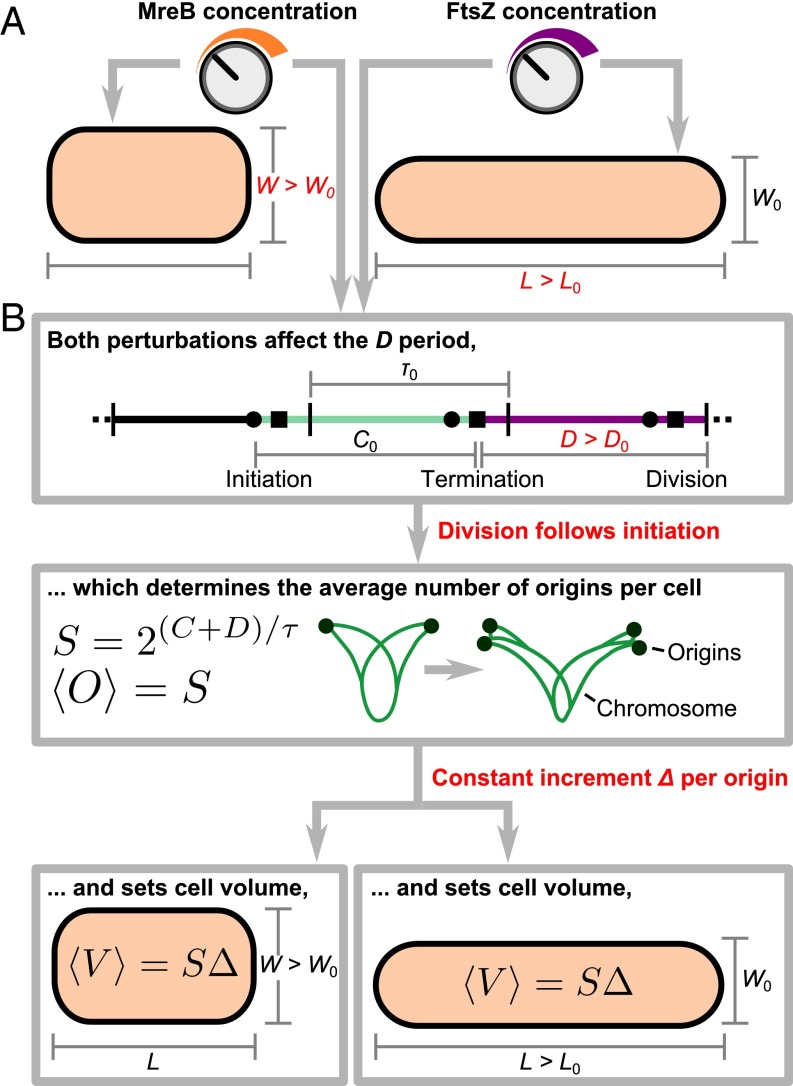

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the experiment. MreB and FtsZ are involved in cell wall synthesis and septum formation, respectively. Using mreB- or ftsZ-titratable strains, we are able to tune their expression levels continuously and perturb cell dimensions. In both experiments, the period increased with cell width and length. The period and doubling time remained constant. (B) Schematic illustration of our model. The perturbed period sets the average number of origins per cell, which is equal to the scaling factor because replication initiation triggers cell division. The average number of origins per cell then sets the average cell volume, following the growth law. For titrated mreB levels, cell volume changes manifested mostly as cell width changes. For titrated ftsZ levels, cell length changed instead, because FtsZ did not affect cell width.

Results

Decreased mreB Level Resulted in Increased Cell Width, with Little Change in Cell Length.

Cell length and cell width are two major characteristics of a rod-shaped cell. As a cell grows, cell length increases exponentially, whereas cell width remains constant. How cell width is determined and maintained is largely unknown. However, several mutations of mreB were reported to result in altered cell dimensions (20, 23, 24), thus raising the possibility that alterations in mreB expression level would alter cell width. To continuously and systematically vary cell width, we constructed a strain in which the level of mreB could be experimentally controlled. We used a system in which a -tetR feedback loop triggered mreB expression (Fig. 2A and SI Methods, Strain Construction). The modulated copy of mreB was the sole version of the gene in the genome as the native copy of mreB was replaced by a kanamycin-resistance gene (Table S1). In this construct, expression of mreB could be tightly controlled by adjusting the concentration of an appropriate inducer of -tetR, anhydrotetracycline (aTc).

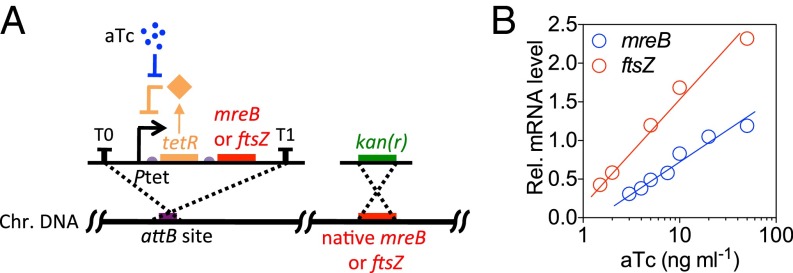

Fig. 2.

Titratable mreB or ftsZ expression. (A) The genetic circuit of the mreB- or ftsZ-titratable strains. The expression of mreB or ftsZ is under the control of a -tetR feedback loop and the native mreB or ftsZ was seamlessly replaced with a kanamycin resistance gene. (B) Relative mreB and ftsZ mRNA level in the titratable strains in bulk culture containing various concentrations of aTc (3–50 ngmL−1).

Table S1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains or plasmids | Genotype or description | Source |

| Strains | ||

| CL-M | A WT E. coli K12 strain AMB 1655 | Antonin Danchin, AMAbiotics |

| ZH1 | , bla:-tetR-mreB at attB site | This study |

| ZH2 | bla:Ptet-tetR at attB site | This study |

| ZH16 | , bla:Ptet-tetR-ftsZ at attB site | This study |

| ZH21 | motA | ZH1, this study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSim5 | Cmr, pSC101 ori, Red | (2) |

| plkml | Ampr, loxp-Kanr-loxp | This study |

| pMD19-T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR | Ampr, pUC ori, bla:Ptet-tetR | This study |

| pMD19-T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR-mreB | Ampr, pUC ori, bla:Ptet-tetR-mreB | This study |

| pMD19-T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR-ftsZ | Ampr, pUC ori, bla:Ptet-tetR-ftsZ | This study |

We found that cell size increased with decreasing inducer concentration until, at very low mreB levels, the cells eventually lysed [at an aTc concentration below 1 ng mL−1 in rich defined medium (RDM) + glucose]. Above this minimum threshold, the expression level of mreB varied linearly with the concentration of inducer (Fig. 2B). We also found that within a certain range of mreB expression levels, the volume growth rates, or OD600 doubling rates (Fig. S1), of the titratable strain remained approximately constant (CV of 0.03) (Fig. 3D). Together, these results suggest that the titratable system is suitable for characterizing the functions of MreB in a quantitative manner with no need to consider complications due to differing growth rates.

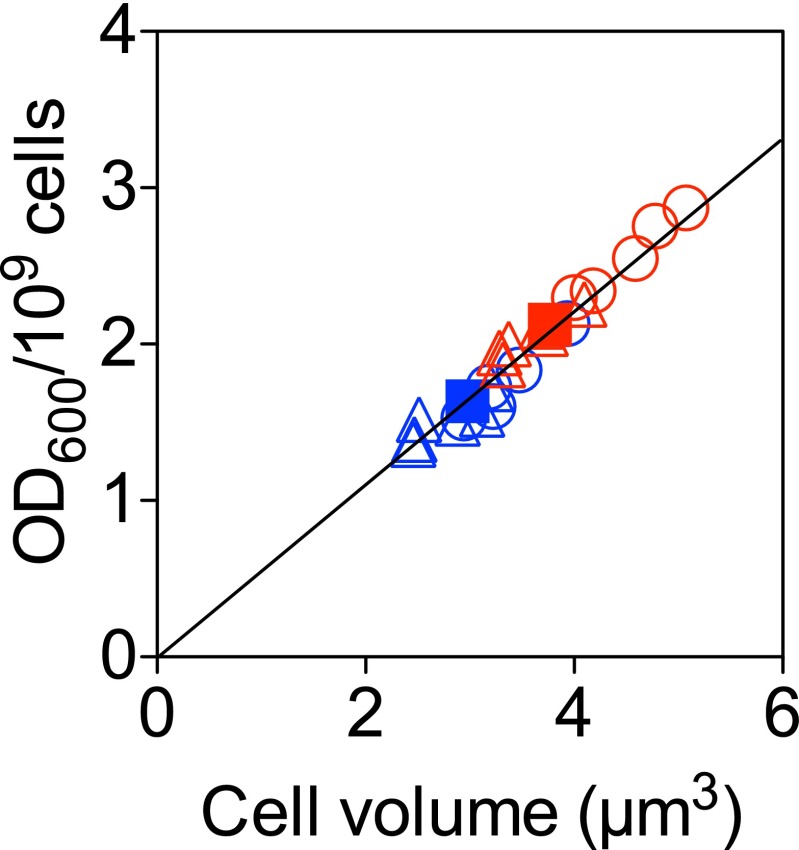

Fig. S1.

The cell volume measured based on the phase-contrast microscope photographs correlates well with OD600/109 cells. The circle, triangle, and square indicate mreB-titratable, ftsZ-titratable, and WT strains, respectively. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. Error bars represent the SEM from three independent experiments.

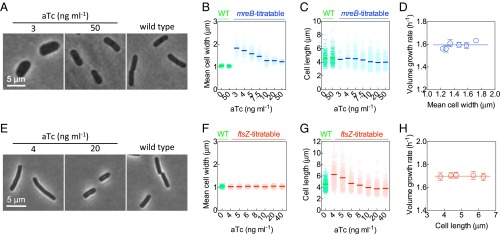

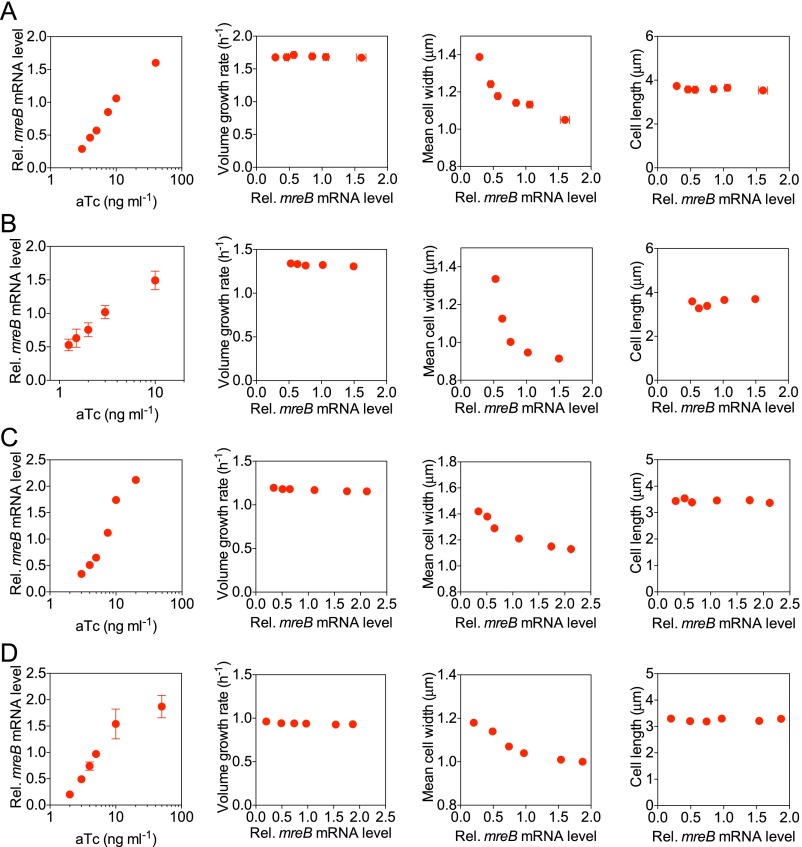

Fig. 3.

Titratable mreB or ftsZ expression to systematically perturb cell width or cell length, respectively, without affecting the volume growth rates. (A) Representative phase contrast images of the mreB-titratable and wild-type strains. (B and C) Scatter plot presents the average, mean cell width (averaged along the long axis of a cell) (B) or average cell length (C) of the individual wild-type (WT) or mreB-titratable cells. (D) Volume growth rates in bulk culture vs. mean cell width for mreB-titratable cells. (E–H) The same as (A–D) but for the ftsZ-titratable strain. Error bars represent the SEM of three replicates.

We next measured cell dimensions by phase contrast micros-copy (Fig. 3A) and found that with decreasing mreB expression level, the cell width increased (Fig. 3B). The cell length changed slightly, which we discuss below (Fig. 3C and SI Text, Cell Length Changes in mreB-Titratable Strains). Although the software used for image processing is designed to define bacterial cell dimensions to subpixel precision (25), we wanted to verify our results, using an independent method. We showed that the OD per cell is linearly correlated with the cell volume in cubic micrometers (Fig. S1). We also verified that neither the presence of inducer nor the presence of the genetic circuit construct has any effect on WT cells within the ranges of inducer concentrations studied here (Fig. 3 B and C and SI Methods, Volume Doubling-Rate Measurement). Similar results were obtained in all other growth media, supporting various fast growth rates, tested in this study (Fig. S2). All of our experiments, and thus the resultant conclusions, concern fast growth conditions as defined above.

Fig. S2.

Decreased mreB expression level results in increased cell width without affecting the volume doubling rate and cell length in various growth media. (A–D) The relative mreB mRNA level, volume doubling rate, mean cell width, and cell length of the mreB-titratable strain were characterized in RDM + glucose (A), RDM + glycerol (B), M9 + glucose + CAA (C), and M9 + glycerol + CAA (D), respectively. Error bars represent the SEM from three independent experiments.

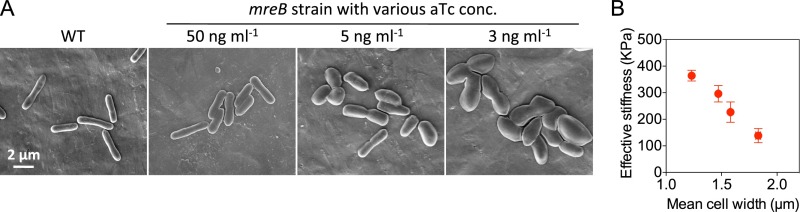

Cell Width Maintenance by Cell Wall Stiffness.

Finally, we characterized in detail the morphological properties of the mreB-titrated cells, using scanning electron microscopy. Here, wider cells showed a slightly flattened, dumpling-like morphology (Fig. S3A). It is known that MreB is involved in bacterial cell wall synthesis (20, 23, 24). Thus, it seemed possible that the cell wall might have become softer in cells expressing low levels of MreB. Due to the difficulty in directly measuring cell wall elasticity, we instead measured the effective cellular stiffness (ECS) of the mreB-titrated cells, using atomic force microscopy. As expected, the ECS significantly decreased as cell width increased (Fig. S3B). This result raises the possibility that increased cell width reflects the force balance between turgor pressure and the tensile resistance of the cell wall.

Fig. S3.

The cell width is maintained by the cell wall stiffness. (A) Representative SEM photographs of the mreB-titratable and WT strains. (B) The cell width is negatively related with the effective cellular stiffness. Error bars represent the SEM from three independent experiments.

Decreased ftsZ Level Resulted in Increased Cell Length and No Change in Cell Width.

We constructed and characterized, using the same method as above, an ftsZ-titratable strain to allow perturbation of cell length (SI Methods, Strain Construction). We found, in agreement with previous work (21), that cell length increased with decreased ftsZ expression levels, but that both cell width and growth rate remained relatively constant within the ranges of inducer concentration studied here (CV of 0.01 and 0.03, respectively, across different experiments, Fig. 3 E–H).

Correlations Between Perturbed Cell Dimensions and Cell Cycle Timings.

We next investigated how the mreB and ftsZ expression levels affect the and periods. For a bulk culture in steady-state exponential growth, the CH model predicts that the average number of origins per cell, , scales exponentially with growth rate (22, 26). This is because in steady-state exponential growth, the number of cells and the total number of origins in the population must both grow exponentially at the same rate. However, because the CH model postulates that division occurs only after a time following the corresponding initiation, the total number of origins will be larger than the number of cells by the scaling factor , defined above. Therefore, . This relation holds regardless of the value of .

An expression for the average number of copies of a gene per cell as a function of the location of the gene along the chromosome ( for oriC and for terC) can be derived similarly. Under the assumption that replication forks travel at a constant speed, the expression is (26). We used this relation to extract the lengths of the and periods from quantitative PCR (qPCR) data of the copy numbers of different chromosome loci (including oriC, terC, and a series of different loci between them; SI Methods, Characterization of the C and D Periods by qPCR and Table S2). The period was also measured independently by the methods in refs. 27 and 28, which gave values consistent with those obtained by the qPCR method (SI Methods, Characterization of the C and D Periods by qPCR). We also measured , using replication run-out experiments (SI Methods, Cellular oriC Characterization).

Table S2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence | Use |

| P102 | ctgactcgagtccctatcagtgatagagattg | Amplify -tetR |

| P103 | ctgaggatccgagctcctgcagttaagacccactttcacatttaag | Amplify -tetR |

| P114 | ctgagagctcggattttcttttccgcc | Amplify mreB |

| P115 | ctgaggatccttactcttcgctgaacaggtc | Amplify mreB |

| P177 | gtcactgcagaaagaggagaaatactagatgtttgaaccaatggaacttacc | Amplify ftsZ |

| P178 | cagtggatccttaatcagcttgcttacgcag | Amplify ftsZ |

| P85 | Gcctcgattactgcgatgtt | Confirmation |

| P145 | Gccttcttattcggccttga | Confirmation |

| PR29 | ttaaaggtattaaaaacaactttttgtctttttaccttcccgtttcgctccaggaaacagctatgaccatg | Recombineering at attB site |

| PR30 | cacaggttgctccgggctatgaaatagaaaaatgaatccgttgaagcctgtgtaaaacgacggccagt | Recombineering at attB site |

| PR31 | gtcgctgctgcgtgtggttggtaaagtaagcggattttcttttccgcccctcgacaaagaggagaaatactagatg | Recombineering at mreB site |

| PR32 | tcgtatcagaccaggcagggtaaacagacacttcccctgcctgcatccgatcagaagaactcgtcaagaagg | Recombineering at mreB site |

| PR66 | ccgacgatgattacggcctcaggcgacaggcacaaatcggagagaaactatgattgaacaagatggattgca | Recombineering at ftsZ site |

| PR67 | gcgggccagtttagcacaaagagcctcgaaacccaaattccagtcaattctcagaagaactcgtcaagaagg | Recombineering at ftsZ site |

| P16 | Gctacaatggcgcatacaaa | RT-qPCR primer for 16S rRNA |

| P17 | Ttcatggagtcgagttgcag | RT-qPCR primer for 16S rRNA |

| P6 | Aatgaaatcctcgaagcact | RT-qPCR primer for mreB |

| P7 | Ccattaacaaacggtcaagg | RT-qPCR primer for mreB |

| P8 | Cttctcttgacccggatatg | RT-qPCR primer for ftsZ |

| P9 | Cattcacgactttagcaacc | RT-qPCR primer for ftsZ |

| L oriC-F | Gagaatatggcgtaccagca | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L oriC-R | Aagacgcaggtatttcgctt | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L oriC-probe | Caacctgacttcggtccgcg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.1-F | Gttcgtagtcagcgatatc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.1-R | Tcacccaaccgaaattac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.1-probe | Aacaggcgttcacttccacca | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.1-F | Ttcccacttactgttctc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.1-R | Tgcagctttcgataatattc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.1-probe | Cgcagaacaatctcgctcagg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.2-F | Tggtcagttccaatagtag | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.2-R | Tgaggatctgcttaataaac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.2-probe | Attcatcaggccgacggtca | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.2-F | Gcctccaccattaataaac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.2-R | Acgcatattccagatgaa | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.2-probe | Tgctgcttctctgtgccgat | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.3-F | Gttgcaaataatccacctg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.3-R | Gcgaatgtcatcaacaac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.3-probe | Atcaccagcaaacgcagttcc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.3-F | Cggtattatcgttgtttca | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.3-R | Ccctttatatatttactgtatttcc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.3-probe | caaggaagataacaataccgccgac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.4-F | Cgcataaaatgtaattctctc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.4-R | Gcaacgatttaatttattatttcc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.4-probe | ccacatacaatcgccgttaccac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.5-F | Taccgtttacctgtatcg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.5-R | Tggtcatatcctttccag | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.5-probe | ctaatgtaacaggttcgccgtcac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.5-F | Gatcgtcaagtactcaag | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.5-R | Ggacatcgttcagaattc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.5-probe | cctctgtgacgatggagtacctac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.6-F | Ccgtcatgatcatctgata | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.6-R | Tgtcgagttgcttgataa | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.6-probe | Aggacgttccatccttgcgt | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.6-F | ccttctgtatatagatatgctaaa | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.6-R | Cctgtccttaactgtatga | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.6-probe | ccttacttccgcatattctctgagc | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.7-F | Tacgcataaagccaacta | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.7-R | Cgatgtgatggaagagaa | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.7-probe | Tgccgacgccatacagtgac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.8-F | Gcacttataacatcacga | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.8-R | Gaacggaatgtcagaatg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L +0.8-probe | ccaatggttactcactggttcagg | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.8-F | Ctcagacacagctttcta | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.8-R | Tccgcatggttatttaac | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L − 0.8-probe | agcaccactaatgatcctgagca | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L terC-F | Tcctcgctgtttgtcatctt | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L terC-R | Ggtcttgctcgaatccctt | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

| L terC-probe | Catcagcacccacgcagcaa | qPCR primer to quantify C and D |

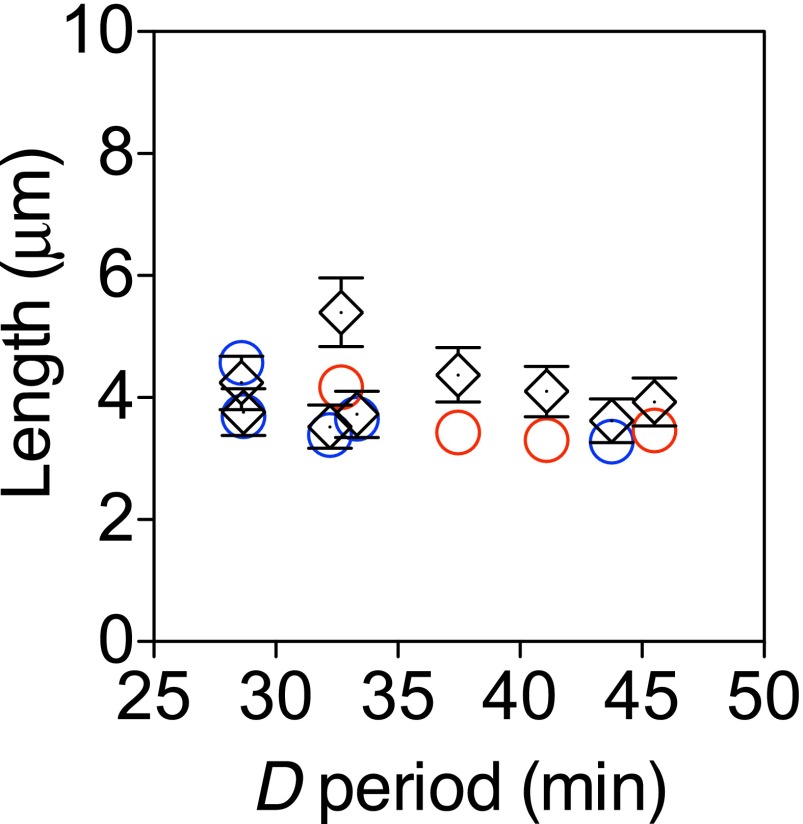

These analyses revealed that, over the analyzed ranges in the levels of both mreB and ftsZ expression, the period remained unchanged (CV of 0.09 and 0.05 for mreB- and ftsZ-titratable strains, respectively), whereas the period increased with increasing cell width or length, respectively (Fig. 4). Note that the relation between the period and cell length predicted by our model below is not linear, but appears approximately linear given the particular values of the relevant parameters under the conditions of these experiments.

Fig. 4.

Changes in the cell cycle parameters as cell dimensions are perturbed. (A) The period increased monotonically with cell width in mreB-titratable strains. The line is the best linear fit. (B) The period remained approximately constant as cell width changed in response to titrated mreB expression levels. The line is the mean value of averaged over mreB expression levels. (C) The period increased monotonically with cell length in ftsZ-titratable strains. (D) The period remained approximately constant as cell length changed in response to titrated ftsZ expression levels. The circle, triangle, and square indicate mreB-titratable, ftsZ-titratable, and WT strains, respectively. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. The SEMs of three replicates were smaller than the size of the symbols.

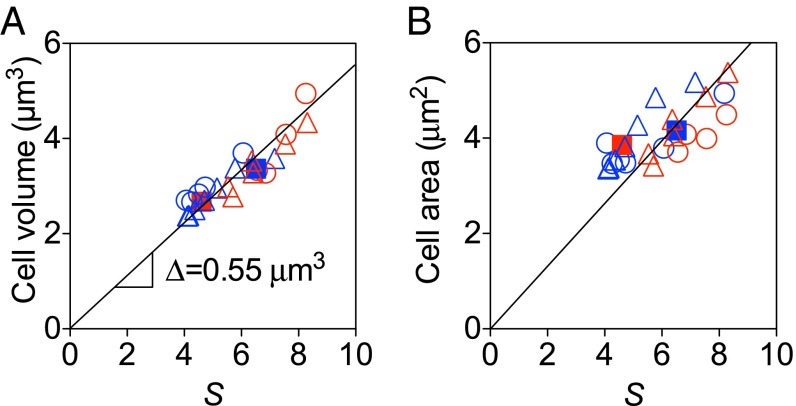

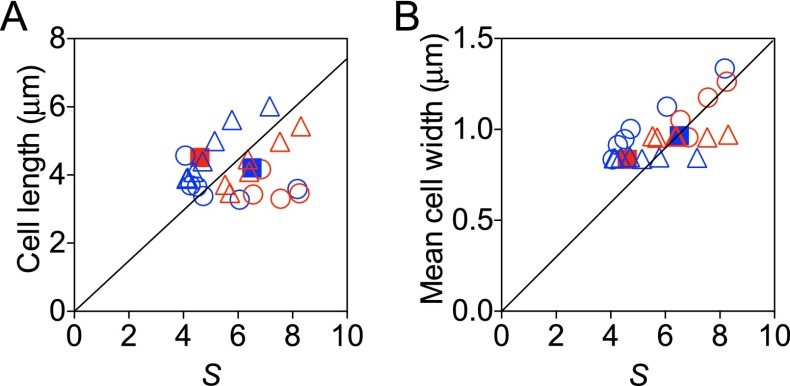

The Growth Law Holds in the Face of Perturbations to Cell Dimensions.

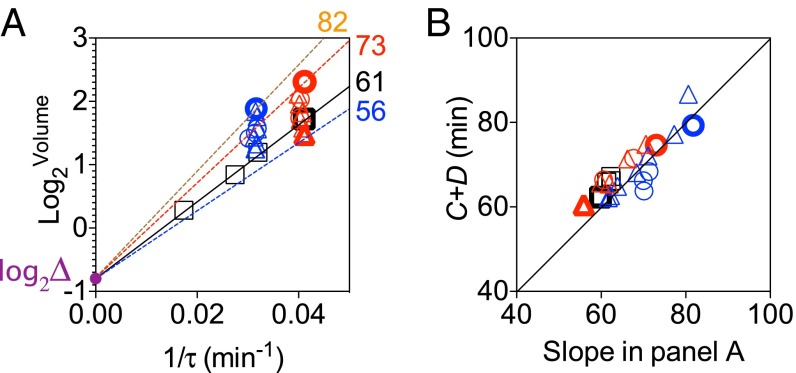

We find that the growth law, Eq. 2, holds in our experiments, both across a range of growth media (Fig. 4) and across the two titratable perturbations that drastically affected cell width and cell length (Fig. 5A). The best-fit proportionality constant is . The plus-or-minus symbol indicates the confidence interval of the fit. From the derivation of the growth law in the Introduction, we find the average cell size per origin at initiation to be . In contrast, the average cell area, cell length, and cell width are not proportional to the scaling factor (Fig. 5B and Fig. S4).

Fig. 5.

The growth law holds in the face of perturbation to cell dimensions. (A) The average cell volume is proportional to the scaling factor . The black line shows the growth law for the best-fit proportionality constant m3. The plus-or-minus symbol indicates the confidence interval of the fit. The coefficient of determination of the fit is . (B) The average cell area is not proportional to the scaling factor. The black line shows the best fit with intercept forced to zero. The of the fit is . The circle, triangle, and square indicate mreB-titratable, ftsZ-titratable, and WT strains, respectively. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. The SEMs of three replicates were smaller than the size of the symbols.

Fig. S4.

The growth law does not apply for cell length or cell width. The average cell length (A) and average cell width (B) were not proportional to the scaling factor. The black line shows the best fit with intercept forced to zero. The coefficients of determination of the fits are −0.62 and −1.09, respectively. A negative coefficient of determination implies that the mean is a better predictor than the fit. The circle, triangle, and square indicate mreB-titratable, ftsZ-titratable, and WT strains, respectively. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. The SEMs of three replicates were smaller than the size of the symbols.

We further tested the validity of a constant by fixing to and calculating the ratio of and , which is equal to according to Eq. 2 (Fig. 6A). We found that the values of obtained in this way agree well with independent measurements in both the titratable and the WT strains (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The average cell volume per origin at initiation is constant in the face of perturbations in cell dimensions. (A) Colored lines connect to symbols in boldface type as examples. The respective slopes of the lines are computed as the ratio of over and shown as numbers (minutes). (B) Measured values are plotted against the ratios calculated in A. The circle, triangle, and square indicate mreB-titratable, ftsZ-titratable, and WT strains, respectively. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. The SEMs of three replicates were smaller than the size of the symbols.

Discussion

Here, we perturbed cell dimensions and then observed the effects of these perturbations on the cell cycle to interrogate the mechanism of cell cycle regulation in E. coli. The most important finding of this work is that the growth law, that average cell volume is proportional to the scaling factor , remained valid across large perturbations in cell dimensions. As discussed in the Introduction, the growth law can be quantitatively derived under two assumptions: (i) the CH model, that replication initiation triggers cell division after a constant time , and (ii) that the average cell volume at initiation of DNA replication is proportional to the number of origins at initiation. The robustness of the growth law documented above suggests that both assumptions hold in face of the perturbations studied here.

Correspondingly, given the first assumption, the presented results support the second class of models for control of cell division (Introduction), in which the timing of initiation governs that of division, and oppose the first class of models in which the timing of division is governed by the accumulation of cell size with no explicit reference to DNA replication. The presented findings do not rule out models in which, opposite to the CH model, division triggers initiation. However, these models are heavily challenged by the finding that is essentially constant (CV of ∼0.1) on the single-cell level at fast growth (11). To be consistent with this finding, these models must somehow coordinate the triggered initiation event with the division event in the next generation. Further studies will be required to investigate this possibility.

Our findings also provide information about the question of what key phenomenological variable governs cell cycle progression. We find that only cell volume, and not surface area, length, or width, is proportional to the scaling factor (Fig. 5 and Fig. S4). Together with the second assumption (above), the robustness of the growth law then supports the hypothesis that volume per origin, rather than other geometric features, is the key phenomenological variable that is invariant at initiation. Hence, cell volume governs the timing of initiation and, by the CH model, the timing of division.

Figs. 5 and 6 also show that the proportionality constant , which links average cell volume to the scaling factor in the growth law (Eq. 2), remained constant across the perturbations studied here. In the derivation of the growth law, is proportional to or the average volume per origin required for initiation. The constancy of therefore suggests that none of the perturbations studied (MreB, FtsZ, and various growth media) affected the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of initiation. Despite drastic changes in cell shape, the titratable strains still initiated replication on average at a constant per origin just as in WT. This value for the average cell volume per origin at initiation is similar to the recently reported value of (11).

Although the present study examined altered genetic conditions that result in altered cell length and cell width, our analysis implies that these changes in cell length and cell width did not affect cell volume directly. Rather—because neither genetic perturbation affected growth rate, the period, or —changes in the period alone were responsible for the observed changes in cell volume, which in turn are manifested as changes in cell length and cell width.

Fig. 1B illustrates schematically how the two genetic perturbations might exert their effects. In one case, reduced ftsZ expression increases the period. Because FtsZ is a direct mediator of septum formation, this effect could result directly from a prolongation of the septation process. The increased period dictates an increased average cell volume, which, in this situation, happens to manifest as an increase in length alone, with no change in width. This asymmetric change in length, vs. width, matches the fact that cell width is maintained normally even in filamentous cells where septation is completely eliminated (21, 29).

Reduced mreB expression also increases the period. In one possibility, MreB would have two direct roles: both in septation via local effects at the division site (30) and in determining cell width. Here, at reduced MreB levels, delayed septation would increase the period. Due to the second role of MreB, the corresponding increase in cell volume in this case is implemented mostly by the increase in cell width. Alternatively, MreB might play only the role of determining cell width. In this scenario, the increased cell width then results in a prolonged septation process and thus a longer period. In both scenarios, however, given experimentally determined values for the period and cell width, the cell volume predicted by the growth law also dictates small changes in cell length. The magnitudes of these predicted changes are just at the level of detection of the current study but are consistent with observed values (Fig. S5).

Fig. S5.

Cell length changes in mreB-titratable strains are small but consistent with the predictions by the growth law. Circles plot the same data as Fig. 4C for mreB-titratable strains. Different colors denote growth media: Red is RDM + glucose, and blue is RDM + glycerol. Black symbols plot predictions of the growth law given cell width and the D period. Error bars represent 10% propagated errors estimated from uncertainties in cell width, the C and D periods, the doubling time , and the proportionality constant .

In general, the growth law specifies cell volume without reference to the aspect ratio of the rod-shape morphology. As a result, a given change in cell volume due to a change in the parameters of the growth law can be manifested as diverse combinations of changes in cell length and cell width.

Our analysis has shown that, in analyzing size-related measurements, the growth law and its underlying tenets imply that any perturbations to the or periods or growth rate will affect cell volume—even if the perturbations are not affecting the core mechanism of size regulation that determines the value of the invariant average cell volume per origin at initiation. Thus, with respect to determining cell size, an important distinction can be made between “primary” and “secondary” regulators, as highlighted in ref. 31. In the context of the above analysis, MreB and FtsZ appear to be secondary regulators in E. coli because remained constant across titrated mreB and ftsZ levels.

All of the considerations above build on the classical works of Schaechter et al. (14), Cooper–Helmstetter (8, 10), and Donachie (15), which consider population average behaviors. Donachie further proposed a single-cell interpretation of his idea in which initiation occurs in a cell when the cell reaches a constant volume per origin (15). However, the proposal is not compatible with experimental single-cell measurements showing adder correlations between cell sizes at births and at divisions (Introduction) because it predicts no such correlations under conditions where growth rate is essentially constant (2, 16, 22).

As a resolution to this conflict, some of us have recently proposed a phenomenological adder-per-origin model in which a constant volume is added between two rounds of initiations, rather than between two rounds of divisions (4, 22). We have shown that this adder-per-origin model leads both to adder correlations and to a constant average cell volume per origin at initiation. Furthermore, adder per origin can also explain rate maintenance and the growth law.

We conclude by discussing several unsolved questions. First, we have ignored single-cell fluctuations in the and periods in our discussion, but recent works show that they are important to understanding single-cell correlations (22, 32). We have also not discussed E. coli in slow growth conditions, but several works raise the possibility that E. coli might behave qualitatively differently there. For instance, previous works suggested that average cell volume per origin at initiation is not constant in such conditions (33, 34). Recent works also suggested that at slow growth, E. coli does not show adder correlations (11). In light of these observations, it will be important to further study the single-cell physiology of E. coli under cell dimension perturbations at slow growth.

There has recently been much interest in the question of cell size homeostasis across all domains of life (35), and we note that adder per origin may be applicable to other organisms as well. For example, it is known that the bacterium Bacillus subtilis also exhibits the growth law and adder correlations. Repeating the experiment here in B. subtilis may help probe the relations between cell dimensions and cell cycle timings in a Gram-positive bacterium. Adder correlations in cell volume were also found recently in budding yeast diploid daughter cells (6). Given the different morphology of these cells, which changes dramatically throughout the cell cycle and particularly at budding, it is plausible that cell volume, and not cell shape, is the key phenomenological variable governing cell cycle regulation also in this case.

Importantly, although our study here has suggested a coarse-grained, phenomenological model on the level of cell dimensions, it has not alluded to the molecular players involved. Several hypothetical molecular mechanisms, such as the accumulation of a threshold amount of an initiator protein per origin (36) or the dilution of an inhibitor protein (37), were previously shown to implement molecularly the phenomenological model discussed here (6, 22). However, despite decades of work, the molecular mechanism for cell cycle regulation in bacteria remains a fundamental unresolved question.

SI Text

Average Cell Volume at Initiation Is Constant per Some Locus Close to the Origin.

As discussed in the Introduction, the growth law follows from (i) the CH model and (ii) the constancy of average cell volume per origin at initiation. The second assumption says that the average volume at initiation is , where is the number of origins in a cell at the time of initiation (e.g., 1 at slow growth and higher powers of 2 at fast growth) (26). The floor operator finds the greatest integer less than or equal to . The first assumption then specifies a division at total cell volume (summed over all offspring of the mother cell corresponding to this initiation) . Immediately after the specified round of division, there will have been a total of rounds of divisions since the original initiation. Hence, the average cell volume at birth is . Then in terms of the cell volume averaged over an exponentially growing population, .

A similar reasoning follows if the second assumption is modified from “per origin” to “per some locus” a distance away from the origin ( is the origin, and is the terminus). In this case, the modified second assumption gives , where is the number of the locus in a cell immediately following initiation. Following the same reasoning, we find that the growth law becomes . However, this expression cannot in general explain the constancy of across our experiments because the quantity explicitly depends on the growth rate. The supposed locus must therefore be close enough to the origin such that remains approximately constant at fast growth.

Cell Length Changes in mreB-Titratable Strains.

Under the assumption that mreB expression level specifies both cell width and the D period, average cell volume is determined by the growth law, , with , the C period, and all relatively constant across mreB expression levels. The cell volume of a rod-shaped bacterium can be approximated as the volume of a cylinder with hemispherical caps, . The growth law therefore specifies cell length to be . The cell lengths calculated in this way compare favorably to those measured via phase contrast microscopy (Fig. S4). Importantly, although the variations in cell length are small, they are consistent with the predictions by the growth law.

SI Methods

Strain Construction.

All strains used in this study are derived from the E. coli K12 AMB1655 strain, which was kindly provided by Antoine Danchin of AMAbiotics, Evry, France. Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. Oligonucleotides used are listed in Table S2.

To construct the mreB-titratable strain, the DNA cassette of the -tetR-mreB feedback loop was amplified and inserted into the chromosomal attB site by recombineering with the aid of pSIM5 (38). Subsequently, the coding sequence (CDS) of mreB at its native locus was replaced with a kanamycin-resistance gene (aph). Briefly, an ampicillin-resistant gene (bla) with a terminator at each end (T0-Amp-T1) was synthesized (BGI) and cloned into the linearized pMD19, obtaining plasmid pMD19-T0-Amp-T1. The -tetR feedback loop was amplified from CL2 (39) by PCR and inserted into pMD19-T0-Amp-T1, which was digested with BamHI and XhoI, generating plasmid pMD19-T0-Amp-T1--tetR. The mreB was amplified from the genomic DNA of strain AMB1655 with primers P114 and P115. The fragment was inserted into pMD19-T0-Amp-T1--tetR digested with SacI and BamHI, resulting in pMD19-T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR-mreB, from which the T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR-mreB cassette was PCR amplified with primers PR29 and PR30 (Table S2), each composed of a 50-bp sequence at the 5’ end homologous to the attB locus region. The PCR products were treated with DpnI (NEB), gel purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and then electroporated into AMB1655 cells containing pSIM5 that encodes Red proteins. Ampicillin-resistant colonies were verified by using colony PCR with primers P85 and P145, followed by direct sequencing. After that, the CDS of the kanamycin resistance gene (aph) was amplified from plkml with primers PR31 and PR32. The mreB gene at the native locus was seamlessly replaced with the aph gene by using the same recombineering protocol. The final mutant was designated as ZH1. To prevent the cell lysis caused by the lack of the mreB expression, 50 ngmL−1 inducer aTc (Clontech) was applied throughout the recombineering experiment and the following cultures unless otherwise stated.

The ftsZ-titratable strain was constructed by using the same protocol. Briefly, the coding sequence of ftsZ was amplified from the genomic DNA of strain AMB1655 and inserted into pMD19-T0-Amp-T1--tetR to generate pMD19-T0-Amp-T1--tetR-ftsZ. Then the T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR-ftsZ cassette was PCR amplified with primers PR29 and PR30 and inserted into the attB site by recombineering. Subsequently, the ftsZ gene at its native site was replaced by aph gene. The final mutant was designated as ZH16.

To construct a reference strain, the T0-Amp-T1--tetR cassette was PCR amplified from pMD19-T0-Amp-T1-Ptet-tetR with primers PR29 and PR30; the cassette was inserted into the chromosomal attB site using the same recombineering protocol, resulting in strain ZH2. To construct an immobilized mreB-titratable strain for the atomic force microscope (AFM) characterization, the motA was seamlessly removed from the chromosome of strain ZH1, designated as ZH21. All mutants were confirmed by sequencing.

Culture Medium and Cell Growth.

Unless otherwise stated, the cells were cultured in Luria–Bertani medium (LB). Plasmids were maintained with 100 mL−1 ampicillin, 25 mL−1 kanamycin, or 25 mL−1 chloramphenicol. For RDM (40), glucose or glycerol was added at 0.4% (wt/vol) as the carbon source. For M9 medium (openwetware.org), 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose or glycerol and 0.2% (wt/vol) casamino acid (CAA) were added. Unless otherwise stated, all other reagents were from Sigma. All experiments were carried out at 37 °C. Cells were grown as described previously (39).

Volume Doubling-Rate Measurement.

As shown in Fig. S1, the OD600 per cell is linearly correlated with the cell volume, so we refereed the OD600 doubling rate as the volume doubling rate. During the experimental culture, the OD600 of the culture was measured every 10 min (20 min for M9-based media). The doubling time (, in minutes) was calculated by fitting the data to an exponential growth curve.

Cell Imaging and Cell Size Parameters Measurement.

Cells were imaged by using a Nikon Ti-E microscope equipped with a 100× phase-contrast objective (N.A. = 1.45) and an Andor Zyla 4.2s CMOS camera. A 1% agarose pad with 0.9% NaCl was used to immobilize the cells. After cell immobilization, images were acquired within 5 min at room temperature (RT).

A customized MATLAB (MathWorks)-based image-processing package, MicrobeTracker (25), was used to contour the cells and calculate the cell size parameters, including the mean cell width, maximal cell width, cell length, cell area, and cell volume according to the phase-contrast microscopic photographs. One pixel on the picture equals 0.065 , which was validated by a graticule.

OD per Cell Measurement.

To characterize the OD per cell, after the OD measurement, 200 L of the cell suspension was immediately diluted 10 times with precooled cell count buffer (0.9% NaCl with 0.12% formaldehyde) and kept in an ice-water bath until cell count.

Bacterial cell counting was performed with a flow cytometer (Beckman; Cyto-FLEX). Samples were diluted as necessary with the straining buffer (cell count buffer supplemented with 1 mgmL−1 DAPI) before the flow cytometer analysis. The flow rate and running time were 60 Lmin−1 and 100 s, respectively. The DAPI-stained particles were deemed the bacterial cells. The OD600 per cell was then calculated by dividing the value of OD600 by the corresponding cell number.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR.

One milliliter of the experimental culture (OD600 ∼ 0.3) was immediately mixed with RNA Bacteria Protect Reagent (Qiagen). Total bacterial RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA yield and purity were estimated using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The absence of the genomic DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR. About 600 ng RNA was reverse transcribed, using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reactions without reverse transcriptase were conducted as controls for the following qPCR reactions. The cDNA samples were further diluted 1:25 with PCR grade water and stored at −20 °C until use. SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH plus) (Takara) was used for qPCR amplification of the amplified cDNA. Each reaction consisted of 5 L diluted cDNA sample, 200 nM forward and reverse qPCR primers, 10 L SYBR Premix Ex Taq, and up to 20 L with PCR grade water. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. The qPCR reactions were performed using a LightCycler 480 System (Roche) with the following program: 30 s at 95 °C and 40 cycles of denaturation (5 s at 95 °C), annealing, and elongation (30 s at 60 °C). Data were acquired at the end of the elongation step. A melting curve was run at the end of the 40 cycles to test for the presence of a unique PCR. To calculate the PCR efficiency, standard curves were made for each gene of target by using serially diluted cDNA samples as the templates. The 16S rRNA was used as the reference gene to normalize the expression level. For each RNA preparation, at least three independent real-time PCR measurements were performed.

Effective Stiffness Measurement.

The immobilized mreB-titrated cells were used for the effective stiffness measurement. Cells were harvested at OD600 ∼ 0.3, centrifuged, and washed for twice with PBS. To immobilize the cells for AFM measurement, the Petri dish was precoated with poly-l-lysine (PLL) (Sigma). The cell suspension was added into the precoated Petri dish and kept at RT for 30 min to immobilize the cells, and then the suspension was removed by careful pipetting. The Petri dish was washed twice with PBS to remove the unbound cells. PBS was then added into the Petri dish for AFM measurements in liquid. AFM measurements were conducted by using Nanowizard II (JPK Instrument). The force–distance and force–time curves were acquired by using a commercial AFM tip with a spring constant Nm−1 (MLCT, Tip D; Bruker). The spring constant of the specific tip was determined by thermonoise methods. Three locations along the vertical axis of a single bacterial cell were selected for data acquisition. The data were processed on the manufacturer’s software; the data were used to fit with the Hertz model to calculate the effective stiffness of the cells.

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with precooled PBS buffer, and then treated with precooled 2% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde and kept at 4 °C for 2 h to fix the cells. Fixed cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with precooled PBS buffer, and then treated with a gradient ethanol for dehydration. Dehydrated cells were resuspended with tertiary butyl alcohol and kept at RT for 30 min; this step was repeated two more times to allow fully replacing the ethanol. A drop of the cell suspension was spread on foil paper and kept at RT to air dry. The samples were then analyzed on a Nova NanoSEM 450 at 5,000× magnification.

Cellular oriC Characterization.

The cellular oriC number was characterized by run-out experiments (41). Briefly, exponentially growing cells (OD600 ∼ 0.2) were treated with 300 mL−1 rifampicin and 30 mL−1 cephalexin for three to four generations. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with TE buffer (20 mM TrisHCl, PH 8.0, 130 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), and fixed in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol at 4 °C overnight. Fixed cells were washed twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (20 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.0, 130 mM NaCl) and resuspended and diluted as necessary with the staining buffer (TBS with 10 ngmL−1 DAPI).

Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a Cyto-FLEX (Beckman) equipped with a 405-nm laser, and the intensity of DAPI signaling was gathered at FL-3 (PB450 channel). The averaged cellular oriC number was calculated based on the distribution of the DAPI signaling of the run-out sample.

Characterization of the C and D Periods by qPCR.

To characterize the C and D periods with a higher accuracy, instead of characterizing the ratio of oriC/terC (21), we quantified the copy number of the 16 different genetic loci () and fitted the with m’ (defined as the reference, e.g., the oriC locus equals 0 and terC locus equals 1) as a straight line, with the slope of the line equaling C and the intercept of the y axis equaling C + D. Briefly, the cells were harvested at OD600 ∼ 0.2, and the cellular DNA was extracted by using the genomic DNA purification kit (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative abundances of different chromosome loci were quantified by qPCR, using hydrolysis probes methods (primer sequences are available in Table S2).

To confirm the C period measured by qPCR, a DNA increment method was applied as described in ref. 42. Chloramphenicol (200 mL−1) was used to inhibit initiation of new rounds of replication, cells were collected by filtration, and the DNA amount was measured by using the diphenylamine colorimetric method. The measured DNA amount after inhibiting the replication initiation was analyzed as described in ref. 28 to get the C period.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the reviewers, Terry Hwa and Arieh Zaritsky, for insightful discussions. This work was financially supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China Grant 31471270, 973 Program Grant 2014CB745202, 863 Program Grant SS2015AA020936, the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar Grant S2013050016987, Shenzhen Peacock Team Plan Grant KQTD2015033ll7210153 (to C.L.), and National Institutes of Health Grant NIH R01 GM025326 (to N.E.K.). A.A. acknowledges support from the A. P. Sloan Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617932114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Campos M, et al. A constant size extension drives bacterial cell size homeostasis. Cell. 2014;159(6):1433–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taheri-Araghi S, et al. Cell-size control and homeostasis in bacteria. Curr Biol. 2015;25(3):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris LK, Theriot JA. Relative rates of surface and volume synthesis set bacterial cell size. Cell. 2016;165(6):1479–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir A. Cell size regulation in bacteria. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;112(20):208102. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deforet M, van Ditmarsch D, Xavier JB. Cell-size homeostasis and the incremental rule in a bacterial pathogen. Biophys J. 2015;109(3):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soifer I, Robert L, Amir A. Single-cell analysis of growth in budding yeast and bacteria reveals a common size regulation strategy. Curr Biol. 2016;26(3):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennard AS, et al. Individuality and universality in the growth-division laws of single E. coli cells. Phys Rev E. 2016;93(1):012408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.012408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmstetter C, Cooper S, Pierucci O, Revelas E. On the bacterial life sequence. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1968;33:809–822. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1968.033.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien AC, Hill NS, Levin PA. Cell size control in bacteria. Curr Biol. 2012;22(9):R340–R349. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper S, Helmstetter CE. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol. 1968;31(3):519–540. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallden M, Fange D, Lundius EG, Baltekin O, Elf J. The synchronization of replication and division cycles in individual E. coli cells. Cell. 2016;166(3):729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skarstad K, Boye E, Steen HB. Timing of initiation of chromosome replication in individual Escherichia coli cells. EMBO J. 1986;5(7):1711–1717. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper S. Cell division and DNA replication following a shift to a richer medium. J Mol Biol. 1969;43(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaechter M, Maaloe O, Kjeldgaard NO. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;19(3):592–606. doi: 10.1099/00221287-19-3-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donachie WD. Relationship between cell size and time of initiation of DNA replication. Nature. 1968;219(5158):1077–1079. doi: 10.1038/2191077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godin M, et al. Using buoyant mass to measure the growth of single cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):387–390. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell EO. Growth rate and generation time of bacteria, with special reference to continuous culture. J Gen Microbiol. 1956;15:491–511. doi: 10.1099/00221287-15-3-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helmstetter CE, Leonard AC. Coordinate initiation of chromosome and minichromosome replication in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(8):3489–3494. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3489-3494.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Lesterlin C, Reyes-Lamothe R, Ball G, Sherratt DJ. Replication and segregation of an Escherichia coli chromosome with two replication origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(26):E243–E250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100874108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner EC, et al. Coupled, circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science. 2011;333(6039):222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1203285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill NS, Kadoya R, Chattoraj DK, Levin PA. Cell size and the initiation of DNA replication in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho PY, Amir A. Simultaneous regulation of cell size and chromosome replication in bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:662. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Arellano-Santoyo H, Combs PA, Shaevitz JW. Actin-like cytoskeleton filaments contribute to cell mechanics in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(20):9182–9185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911517107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Teeffelen S, et al. The bacterial actin MreB rotates, and rotation depends on cell-wall assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(38):15822–15827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sliusarenko O, Heinritz J, Emonet T, Jacobs-Wagner C. High-throughput, subpixel-precision analysis of bacterial morphogenesis and intracellular spatio-temporal dynamics. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(3):612–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bremer H, Dennis P. 1996. Escherichia coli and Salmonella, ed Neidhardt F (ASM, Washington DC), pp 1553–1569.

- 27.Bremer H, Churchward G. Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis after inhibition of initiation of rounds of replication in Escherichia coli B/r. J Bacteriol. 1977;130(2):692–697. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.692-697.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bipatnath M, Dennis PP, Bremer H. Initiation and velocity of chromosome replication in Escherichia coli B/r and K-12. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(2):265–273. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.265-273.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amir A, Babaeipour F, McIntosh DB, Nelson DR, Jun S. Bending forces plastically deform growing bacterial cell walls. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(16):5778–5783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317497111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenton AK, Gerdes K. Direction interaction of FtsZ and MreB is required for septum synthesis and cell division in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2013;32(13):1953–1965. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boye E, Nordström K. Coupling the cell cycle to cell growth. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(8):757–760. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adiciptaningrum A, Osella M, Moolman MC, Lagomarsino MC, Tans SJ. Stochasticity and homeostasis in the E. coli replication and division cycle. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18261. doi: 10.1038/srep18261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bates D, Kleckner N. Chromosome and replisome dynamics in E. coli: Loss of sister cohesion triggers global chromosome movement and mediates chromosome segregation. Cell. 2005;121(6):899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wold S, Skarstad K, Steen HB, Stokke T, Boye E. The initiation mass for DNA replication in Escherichia coli K-12 is dependent on growth rate. EMBO J. 1994;13(9):2097–2102. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginzberg MB, Kafri R, Kirschner M. On being the right (cell) size. Science. 2015;348(6236):1245075. doi: 10.1126/science.1245075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sompayrac L, Maaloe O. Autorepressor model for control of DNA replication. Nat New Biol. 1973;241(109):133–135. doi: 10.1038/newbio241133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fantes PA, Grant WD, Pritchard RH, Sudbery PE, Wheals AE. The regulation of cell size and the control of mitosis. J Theor Biol. 1975;50:213–244. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(75)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta S, Costantino N, Court DL. A set of recombineering plasmids for gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 2006;379:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, et al. Sequential establishment of stripe patterns in an expanding cell population. Science. 2011;334(6053):238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1209042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neidhardt FC, Bloch PL, Smith DF. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119(3):736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lobner-Olesen A, Skarstad K, Hansen FG, von Meyenburg K, Boye E. The DnaA protein determines the initiation mass of Escherichia coli K-12. Cell. 1989;57(5):881–889. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Churchward G, Bremer H. Determination of deoxyribonucleic acid replication time in exponentially growing Escherichia coli B/r. J Bacteriol. 1977;130(3):1206–1213. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.3.1206-1213.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]