Abstract

Juvenile sex ratios are often assumed to be equal for many species with genetic sex determination, but this has rarely been tested in fish embryos due to their small size and absence of sex-specific markers. We artificially crossed three populations of brown trout and used a recently developed genetic marker for sexing the offspring of both pure and hybrid crosses. Sex ratios (SR = proportion of males) varied widely one month after hatching ranging from 0.15 to 0.90 (mean = 0.39 ± 0.03). Families with high survival tended to produce balanced or male-biased sex ratios, but SR was significantly female-biased when survival was low, suggesting that males sustain higher mortality during development. No difference in SR was found between pure and hybrid families, but the existence of sire × dam interactions suggests that genetic incompatibility may play a role in determining sex ratios. Our findings have implications for animal breeding and conservation because skewed sex ratios will tend to reduce effective population size and bias selection estimates.

Keywords: embryo development, sex-specific mortality, sex ratio, genetic incompatibility, genetic conflict, sex determination

1. Introduction

The extent to which parents can control the sex of their offspring has long been the subject of much debate [1]. Fisher’s principle of equal sex allocation [2] posits that sex ratios should be roughly equal at birth because any large deviation from 1 : 1 will be quickly selected against, i.e. producing the same number of sons and daughters is an evolutionary stable strategy [3]. However, this assumes that sex allocation has no costs, which may not be the case [4]. For example, in species where maternal effects determine embryo survival and males vary more in reproductive success than females (as is typical of salmonids and many other fish [5]), mothers in good condition may be expected to produce an excess of sons, whereas mothers in poor condition should produce an excess of daughters [6]. Yet, theories of sex allocation have rarely been tested in highly fecund fishes, due to the difficulty of sexing small embryos and the absence of sex-specific markers. The recent description of the master sex-determining gene sdY in rainbow trout [7] has made it possible for the first time to sex salmonid fishes at an early stage [8]. This presents an unprecedented opportunity in evolutionary ecology because skewed sex ratios are typical of many exploited fish populations [9], and these may vary widely from year to year [10]. Testing predictions of optimal sex allocation is typically confounded by sex differences in life-history traits [11]. For example, females are generally more common among migratory fish [12] than among resident fish, which tend to be sexually balanced [13] or be male-biased [14].

At the molecular level, there is evidence that both intragenomic and intergenomic ‘genetic conflict’ can affect sex ratios, particularly when recombination patterns differ widely between the sexes [15]. Recombination rates in salmonids tend to be higher in females than in males—and perhaps most importantly—tend to occur in different chromosome regions, crossovers between homeologous chromosomes having being observed only in the telomeric regions of males [16]. Consequently, the Y-chromosome tends to accumulate more deleterious mutations, which may have consequences for embryo survival. This would present opportunities for any effects of genetic incompatibility to differ between the sexes.

We artificially crossed three hatchery populations of brown trout, a species with genome duplication and an unusually high number of chromosomes (2n = 80; NF = 100 [17]) in order to examine the influence of outcrossing and parental identity on sex ratios. Our expectation was that hybrid and pure crosses might differ in sex ratios due to differences in pairing and recombination between homeologous chromosomes, and that males might suffer increased embryo mortality due to their lower recombination rates and greater interference at telomeric regions.

2. Material and methods

We employed a partial factorial mating design [18] to cross 15 males with 15 females from three domesticated brown trout populations (F = Hardy, S = Hardy-Prosper, G = Gournay) on 5 December 2014, so that one clutch from each female was crossed with three males (one from each population). This was repeated five times to produce 15 pure and 30 hybrid families (electronic supplementary material, table S1), which were distributed in duplicate over 95 egg boxes along three tanks (mean egg density/box = 117 ± 1.6 s.e.) at the PEIMA hatchery (France). The three populations have been maintained under culture since 1986, and differ with respect to domestication selection (S, selected for growth; F and G, unselected) and genetic structure (F and S, single origin populations; G, multiple origins population [19]). Embryo mortalities were removed daily, and alevins were reared at 11.4–12.1°C for 51 days until the ‘swim up’ stage (i.e. before the onset of external feeding), at which point they were humanely euthanized (Ethical approval B2977702, 07/2013) and stored in ethanol for genetic analysis. Sex was determined using primers SdYE1S1 and SS sdYE2AS4 [7], identification being resolved by the presence of PCR product around 600–700 bp in males and its absence in females. To verify the accuracy of this method, 30 male parents from each stock, and all the female parents, were genetically sexed, and one male which failed the PCR amplification was discarded and not used in the crosses. For quality control, approximately 200 PCRs were randomly repeated and 30 embryos were sexed twice in a double blind fashion.

We employed generalized linear mixed modelling (GLMM) to analyse sex ratios using the glmer function in the lme4 package of R 3.3.2. We used type of cross (pure versus hybrid), relative fecundity (egg mass/body mass) and embryo mortality (no. dead embryos/total no. eggs) as fixed factors, and dam, sire, sire nested within dam, and egg box nested within tank as random factors. We sexed 20 fish per replicate for 69% of the families; samples with less than 12 fish per replicate were excluded, which reduced the sample size to 34 families distributed over 66 egg boxes. To determine the most plausible model, we employed a hierarchical approach based on AIC changes and backward selection using the drop1 function in lme4 based on the likelihood ratio test, LRT [20].

3. Results

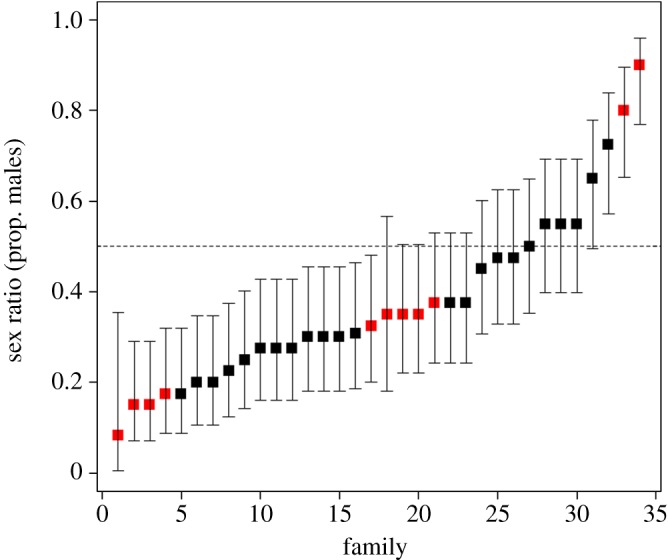

There was 100% agreement between phenotypic and genetic sex determination for all the parents used in the crosses, as well as for the duplicated sexing of the same embryos. We are thus confident genetic sexing was reliable. The sex ratio of 1311 embryos was significantly biased towards females (males = 501, females = 810, Fisher's Exact test p < 0.001). However, SR varied widely among crosses (figure 1, mean = 0.39 ± 0.03 s.e.) and 60% of families yielded significantly skewed sex ratios, these being over four times more likely to be female-biased (n = 17 families) than male-biased (n = 4 families). Family replicates (from different egg boxes) produced very similar SR (IC correlation coefficient = 0.96) and were dropped from the final model (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Hybrid crosses produced more females than pure crosses (65% versus 56%, Fisher exact test p < 0.001), but this was partially the result of differential mortality and could be removed from the final model (LRT = 1.813, d.f. = 1, p = 0.178). The most plausible SR model (table 1) included embryo mortality (estimate = −0.30, s.e. = 0.12, p = 0.01) and relative fecundity (estimate = −0.28, s.e. = 0.13, p = 0.04) as significant predictors, and sire nested within dam as a random factor (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Figure 1.

Variation in family sex ratios (proportion of males ±95 CI) for pure (red squares) and hybrid (black squares) crosses.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of SR (proportion of males) by GLMM obtained by backward selection. Mortality and relative fecundity were scaled prior to analysis. (Significant p-values are shown in bold.)

| variable | d.f. | LRT | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| embryo mortality (M) | 1 | 5.95 | 0.015 |

| population type (T) | 1 | 1.81 | 0.178 |

| relative fecundity (F) | 1 | 4.26 | 0.039 |

| M × T interaction | 1 | 2.50 | 0.114 |

| M × F interaction | 1 | 0.59 | 0.443 |

| T × F interaction | 1 | 0.15 | 0.701 |

| M × T × F interaction | 1 | 1.66 | 0.198 |

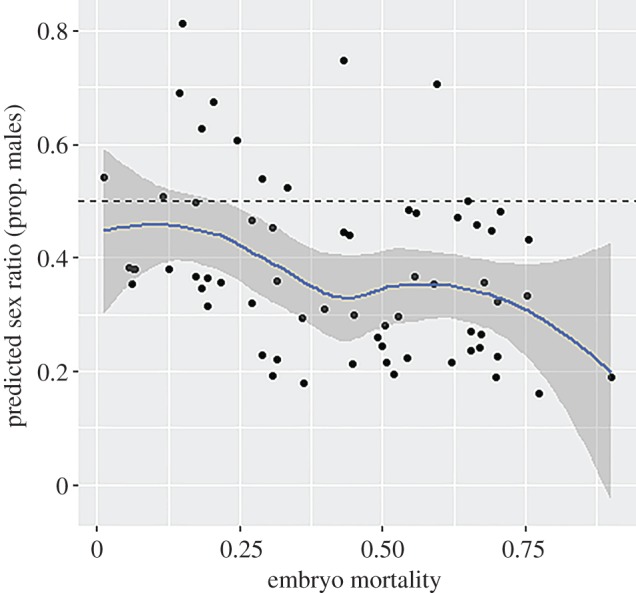

Mean embryo mortality was 56.5% but this varied widely among families (range = 5–100%) and was particularly high 25–35 days post-fertilization, when 47% of mortalities occurred. Crosses with high embryo mortality were more female-biased (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between embryo mortality and predicted SR (proportion of males) for each experimental egg box. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

Our study suggests that the assumption of equal sex ratios at one month post-hatching does not hold true for brown trout embryos. Instead, sex ratios were commonly skewed, these being typically female-biased, though an overrepresentation of males was also observed in some families. In common with other studies [21], our SR estimates were obtained sometime after hatching. This makes it problematic to distinguish between variation in sex allocation and sex-biased mortality. Yet, we detected significantly skewed sex ratios even in families that had sustained relatively low mortalities (13–17%), suggesting that there is scope for both. In this sense, it would be most fruitful to compare the sex ratios of live and dead embryos, though this was not possible in our study due to degraded DNA.

Skewed sex ratios appeared to be largely the consequence of high male mortality, most of which occurred during a 10-day period, corresponding to 300–450 temperature units, the stage when the teleost immune system is differentiating and salmonid embryos are most sensitive to stress [22]. This is consistent with disruption during embryo development, rather than with low fertilization success. The sex-determining locus in brown trout is located very close to the telomere of a small chromosome [23], where it may experience anomalous segregation during meiosis, result in genome imbalance [16] and impact on male survival, which is consistent with our results, though other explanations cannot be ruled out. For example, it is possible that sex ratios at birth are also skewed due to genetic conflict [15].

Contrary to our expectations, hybrid crosses did not produce offspring with more skewed sex ratios, though we found some evidence for sire × dam interactions (electronic supplementary material, table S2) and a role for maternal investment. Female-biased sex ratios were more likely among the offspring of mothers with high relative fecundity, i.e. when maternal investment was high. This suggests that parents may play a role in determining the sex ratio of their offspring, possibly through genetic incompatibility and by impacting disproportionately in the viability of male embryos, as seen in other species [24]. For example, in some birds, mating between genetically incompatible parents results in an excess of sons, thereby protecting mothers from investing in inviable daughters [25]. Likewise, some lizards sire a disproportionally high proportion of sons while others sire a large proportion of daughters [26], apparently depending on male body size.

Our findings have implications for demographic studies because survival and selection estimates that assume balanced juvenile sex ratios [27] will tend to be biased if, as our results indicate, skewed sex ratios are common early in life. Skewed sex ratios will tend to reduce effective population size [28], but the existence of sire × dam interactions means that by mating with multiple males, females may produce broods with varying sex ratios, which may represent an adaptive bet-hedging strategy [21].

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Consuegra, E. Quillet and three reviewers for useful comments, and Lise-Anne Leven for help with the hatchery trials.

Ethics

Fish used in this study were reared under standard hatchery conditions and were humanely euthanized under PEIMA Ethical approval No. B2977702, 07/2013.

Data accessibility

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.3h45m [29].

Authors' contributions

P.M. and C.G.L. designed the study; P.M. carried out the genetic sexing; C.G.L. carried out the statistical analyses; C.G.L. and P.M. wrote the manuscript with input from L.L.; P.M. and L.L. collected the data. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

Access to the PEIMA facility was funded by FP7 AQUAEXCEL 0114/08/01/10, 262336.

References

- 1.Andersson M, Simmons LW. 2006. Sexual selection and mate choice. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 296–302. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RA. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford, UK: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maynard-Smith J. 1978. The evolution of sex. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pen I, Weissing FJ. 2002. Optimal sex allocation: steps towards a mechanistic theory. In Sex ratios: concepts and research methods (ed. Hardy ICW.), pp. 26–46. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming IA, Reynolds JD. 2004. Salmonid breeding systems. In Evolution illuminated. salmon and their relatives (eds Hendry AP, Stearns SC), pp. 264–294. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trivers RL, Willard DE. 1973. Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring. Science 179, 90–92. ( 10.1126/science.179.4068.90) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano A, et al. 2012. An immune-related gene evolved into the master sex-determining gene in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Curr. Biol. 22, 1423–1428. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quéméré E, Perrier C, Besnard A-L, Evanno G, Baglinière J-L, Guiguen Y, Launey S. 2014. An improved PCR-based method for faster sex determination in brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Conserv. Genet. Res. 6, 825–827. ( 10.1007/s12686-014-0259-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan M, Trippel E. 1996. Skewed sex ratios in spawning shoals of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 53, 820–826. ( 10.1006/jmsc.1996.0103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Consuegra S, García de Leániz C. 2007. Fluctuating sex ratios, but no sex-biased dispersal, in a promiscuous fish. Evol. Ecol. 21, 229–245. ( 10.1007/s10682-006-9001-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schindler S, Gaillard J-M, Grüning A, Neuhaus P, Traill LW, Tuljapurkar S, Coulson T. 2015. Sex-specific demography and generalization of the Trivers-Willard theory. Nature 526, 249–252. ( 10.1038/nature14968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson B. 1985. Life history patterns of freshwater resident and sea-run migrant brown trout in Norway. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 114, 182–194. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pompini M, Buser AM, Thali MR, Von Siebenthal BA, Nusslé S, Guduff S, Wedekind C. 2013. Temperature-induced sex reversal is not responsible for sex-ratio distortions in grayling Thymallus thymallus or brown trout Salmo trutta. J. Fish Biol. 83, 404–411. ( 10.1111/jfb.12174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rundio DE, Williams TH, Pearse DE, Lindley ST. 2012. Male-biased sex ratio of nonanadromous Oncorhynchus mykiss in a partially migratory population in California. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 21, 293–299. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0633.2011.00547.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werren JH, Beukeboom LW. 1998. Sex determination, sex ratios, and genetic conflict. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29, 233–261. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.233) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allendorf FW, Bassham S, Cresko WA, Limborg MT, Seeb LW, Seeb JE. 2015. Effects of crossovers between homeologs on inheritance and population genomics in polyploid-derived salmonid fishes. J. Hered. 106, 217–227. ( 10.1093/jhered/esv015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartley SE. 1987. The chromosomes of salmonid fishes. Biol. Rev. 62, 197–214. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1987.tb00663.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupont-Nivet M, Vandeputte M, Haffray P, Chevassus B. 2006. Effect of different mating designs on inbreeding, genetic variance and response to selection when applying individual selection in fish breeding programs. Aquaculture 252, 161–170. ( 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.07.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chevassus B, Quillet E, Krieg F, Hollebecq M-G, Mambrini M, Fauré A, Labbé L, Hiseux J-P, Vandeputte M. 2004. Enhanced individual selection for selecting fast growing fish: the ‘PROSPER’ method, with application on brown trout (Salmo trutta fario). Genet. Select. Evol. 36, 643–661. ( 10.1186/1297-9686-36-6-643) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker N, Saveliev AA, Smith GM. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn AT, Kokko H, Jennions MD. 2013. Adaptive sex allocation in anticipation of changes in offspring mating opportunities. Nat. Commun. 4, 1603 ( 10.1038/ncomms2634) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feist G, Schreck CB. 2001. Ontogeny of the stress response in chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 25, 31–40. ( 10.1023/A:1019709323520) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Phillips RB, Harwood AS, Koop BF, Davidson WS. 2010. Identification of the sex chromosomes of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and their comparison with the corresponding chromosomes in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 133, 25–33. ( 10.1159/000323410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birkhead TR, Pizzari T. 2002. Postcopulatory sexual selection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 262–273. ( 10.1038/nrg774) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pryke SR, Griffith SC. 2009. Genetic incompatibility drives sex allocation and maternal investment in a polymorphic finch. Science 323, 1605–1607. ( 10.1126/science.1168928) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calsbeek R, Sinervo B. 2004. Within-clutch variation in offspring sex determined by differences in sire body size: cryptic mate choice in the wild. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 464–470. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00665.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott JM. 1994. Quantitative ecology and the brown trout. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frankham R. 2007. Effective population size/adult population size ratios in wildlife: a review. Genet. Res. 89, 491–503. ( 10.1017/S0016672308009695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morán P, Labbé L, Garcia de Leaniz C.2016. Data from: Male-biased mortality results in skewed sex ratios in brown trout embryos. Dryad Digital Repository. ( ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.3h45m [29].