Abstract

Purpose

Religion and/or spirituality (R/S) have increasingly been recognized as key elements in patients' experience of advanced illness. This study examines the relationship of spiritual concerns (SCs) to quality of life (QOL) in patients with advanced cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients were recruited between March 3, 2006 and April 14, 2008 as part of a survey-based study of 69 cancer patients receiving palliative radiotherapy. Sixteen SCs were assessed, including 11 items assessing spiritual struggles (e.g., feeling abandoned by God) and 5 items assessing spiritual seeking (e.g., seeking forgiveness, thinking about what gives meaning in life). The relationship of SCs to patient QOL domains was examined using univariable and multivariable regression analysis.

Results

Most patients (86%) endorsed one or more SCs, with a median of 4 per patient. Younger age was associated with a greater burden of SCs (β = −0.01, p = 0.006). Total spiritual struggles, spiritual seeking, and SCs were each associated with worse psychological QOL (β = −1.11, p = 0.01; β = −1.67, p < 0.05; and β = −1.06, p < 0.001). One of the most common forms of spiritual seeking (endorsed by 54%)—thinking about what gives meaning to life—was associated with worse psychological and overall QOL (β = − 5.75, p = 0.02; β = −12.94, p = 0.02). Most patients (86%) believed it was important for health care professionals to consider patient SCs within the medical setting.

Conclusions

SCs are associated with poorer QOL among advanced cancer patients. Furthermore, most patients view attention to SCs as an important part of medical care. These findings underscore the important role of spiritual care in palliative cancer management.

Introduction

Religion and/or spirituality (R/S) have increasingly been recognized as key elements shaping many patients' experiences of advanced illness. For example, the majority of patients with advanced illness view R/S as both personally important1–3 and a significant component of their illness experience. Patients also frequently rely upon their R/S beliefs to cope with the stress of advanced illness (i.e., religious coping).2,4 Furthermore, spiritual well-being and religious coping are associated with better patient quality of life (QOL) in the setting of life-threatening illness,5–7 and mitigate the impact of physical symptoms on overall QOL.5 In the context of advanced illness, most patients experience spiritual concerns (SCs).8,9 The high rates of SCs among patients with advanced illness are compelling considering patients rate R/S peace, together with being free from pain, as the most important factors impacting their well-being as they face death.10

Because of these data, national7 and international11 palliative care guidelines include spiritual care recognition of the role of patients' R/S in illness and attention to R/S needs—as a key component of end-of-life (EOL) care. However, there is little guidance to clinicians regarding the provision of spiritual care, a factor likely contributing to the relative absence of spiritual care.1,12 For example, little is known about the relationship of SCs to patient well-being in the context of advanced illness, and more specifically, how the burden of particular types of SCs relates to patients' QOL. Therefore, improved characterization of these relationships is warranted and may assist clinicians in addressing patients' SCs.

The Religion and Spirituality in Cancer Care (RSCC) study is a multi-site study of advanced cancer patients that aims to empirically guide the role of spiritual care in the advanced cancer care setting. The goal of this investigation is to examine the relationship between SCs and patient well-being.

Methods

Study sample

Patients were recruited between March 3, 2006 and April 14, 2008 as part of a survey-based study of incurable cancer patients receiving palliative radiotherapy (RT). Eligibility criteria included: (1) diagnosis of advanced, incurable cancer at least one month prior to enrollment; (2) active receipt of palliative RT; (3) adequate stamina to undergo the 45-minute questionnaire; and (4) age 21 years or greater. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete the interview in English or Spanish, or evidence of dementia/delirium as assessed by neurocognitive examination using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.13

Study protocol

All research staff underwent a one-day training session in the study protocol and the interviewer-administered questionnaire. Patients were recruited from four Boston, MA hospitals: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Patients were randomly selected from RT schedules; all eligible patients were approached for participation. To mitigate selection bias, study staff informed all potential participants, “You do not have to be religious or spiritual to answer these questions. We want to hear from people with all types of points of view.” Participants provided written, informed consent according to protocols approved by each site's human subjects committee. Definitions for R/S grounded the study's design and were provided to participants at the beginning of the interview. Spirituality was defined as “a search for or a connection to what is divine or sacred” and religion was defined as “a tradition of spiritual beliefs and practices shared by a group of people.” Of 103 patients approached, 75 (73%) participated. Six patients had missing data, 5 due to being too ill/fatigued to complete the interview, consistent with their lower average Karnofsky performance scores (37.5 versus 68.2, p = 0.02), yielding a total of 69 eligible patients.

Study measures

Participant religiousness and spirituality

Two items from the Fetzer Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality were used to assess patient religiousness and spirituality.10 Patients indicated their religious traditions as “Catholic,” “Protestant,” “Jewish,” “Muslim,” “Buddhist,” “Hindu,” “No Religious Tradition,” and “Other.” Patients indicated how often they attended organized religious activity according to 5 categories: “1 time per year or less,” “2–5 times per year,” “6–11 times per year,” “1–3 times per month,” or “1 time per week or more.”

Spiritual concerns

Patients were asked, “What spiritual issues have you had as you have been dealing with your illness?” Response options were consistent with prior studies of SCs in the setting of advanced illness8,14,15 and with the study's R/S definitions, including: “seeking a closer connection with God or your faith,” “doubting your belief in God or your faith,” “finding meaning in the experience of your cancer,” “being angry with God,” “wondering why God has allowed this to happen,” “thinking about forgiveness (being forgiving toward others or being forgiven by others),” and “thinking about what gives meaning to life.” Items were developed by the study authors, with face validity, piloted among advanced cancer patients, and sampled to redundancy. Pargament's validated negative religious coping items16 were also utilized as they assess R/S struggles, including feeling abandoned by God, feeling abandoned by R/S communities, questioning God's love, questioning God's power, thinking the devil caused the cancer, and feeling punished by God. Response options were “not at all,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” and “a great deal,” with the spiritual issue considered present when patients answered “somewhat” or greater. Patients were also asked in an open-ended manner, “What other spiritual issues have you experienced?” Responses were transcribed verbatim. All SCs were categorized as either indicating disharmony in one's relationship to one's faith (e.g., feeling abandoned by God), termed “spiritual struggle” (11 items), or indicating a process of seeking a greater connection with, or understanding of one's faith (e.g., seeking forgiveness, or thinking about what gives meaning to life), termed “spiritual seeking” (5 items). This categorization was performed to assess how differing forms of SCs—spiritual struggles and spiritual seeking—relate to patient QOL. Total spiritual seeking, spiritual struggle, and overall SC scores were created by summing the total number of each endorsed (possible scores: spiritual seeking 0–5, spiritual struggle 0–11, and total SCs 0–16).

Quality of life

Patient QOL was assessed with the McGill QOL Questionnaire, which has been validated for use in all stages of advanced cancer.17,18 The instrument assesses 4 QOL domains: physical, psychological, existential, and social support. Each of the 16 items has an 11-point response scale (possible scores 0–10). The psychological QOL domain is measured with 4 items (possible scores 0–40, Cronbach's α = 0.81); the physical domain is measured with 3 items (possible scores 0–30, Cronbach's α = 0.62); the existential well-being domain is measured with 6 items (possible scores 0–60, Cronbach's α = 0.79); and the social support domain is measured with 2 items (possible scores 0–20, Cronbach's α = 0.74). Overall QOL is the sum total of each of the domains, with an additional item (scored 0–10) assessing overall QOL to yield total possible QOL scores of 0–160 (Cronbach's α = 0.83).

Other variables

Patients reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity (dichotomized to white versus nonwhite because of limited sample size), years of education, income, and marital status. Karnofsky performance status was obtained by physician assessment.

Disease and survival variables were obtained from patients' medical records.

Analytical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographic, disease/survival, and R/S variables. The relationships among spiritual seeking, spiritual struggle, and total SCs to QOL (total QOL and the 4 QOL domains) were assessed using univariate linear regression. Other potential predictors of patient QOL assessed included patient demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race, age, income), R/S variables (e.g., religiousness, spirituality, religious tradition), and disease/survival variables (e.g., cancer type, Karnofsky performance status, time from interview to death). Multivariable regression models were used with adjustment for all significant confounding factors. Potential confounders included all demographic, R/S, and disease variables; these were entered into the model when marginally associated with patient QOL (p < 0.10) and retained when the variable remained significantly associated (p < 0.05) after controlling for other variables. Univariate regression was used to examine predictors of total SCs and of patients' desires for health care professionals to consider their R/S needs. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R 2.10.1 (R Development Core Team, 2009). All reported p values are two-sided and considered significant when less than 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics and survival data

The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most patients reported themselves to be at least slightly religious (81%) or at least slightly spiritual (93%), and almost half of patients (49%) reported being moderately or very religious and spiritual. Consistent with the nature of this advanced cancer population, patients died a median of 180 days (interquartile range 62–485 days) after the baseline interview.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample (n = 69)

| Age, years, M (SD) | 60.7 (11.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (54) |

| Married, n (%)a | 40 (58) |

| Nonwhite race, n (%) | 12 (17) |

| Education, years, M (SD) | 15.3 (3.4) |

| Income, greater than $50,000, n (%)b | 32 (46) |

| Karnofsky performance status, M (SD)c | 68.2 (19.7) |

| Cancer Type | |

| Lung, n (%) | 23 (33) |

| Prostate, n (%) | 5 (7) |

| Breast, n (%) | 11 (16) |

| Colorectal, n (%) | 6 (9) |

| Heme/Lymphoma, n (%) | 11 (16) |

| Ovary, n (%) | 1 (1) |

| Other, n (%) | 12 (17) |

| Overall McGill Quality of Life (QOL), M (SD)d | 104.9 (25.1) |

| Physical QOL, M (SD)d | 10.07 (4.1) |

| Psychological QOL, M (SD)d | 28.72 (9.6) |

| Existential QOL, M (SD)d | 42.97 (11.4) |

| Support QOL, M (SD)d | 16.82 (3.5) |

| Religious Tradition | |

| Catholic, n (%) | 32 (46) |

| Protestante, n (%) | 22 (32) |

| Jewish, n (%) | 5 (7) |

| Other, n (%)f | 10 (15) |

| Religiousness | |

| Very religious, n (%) | 14 (20) |

| Moderately religious, n (%) | 25 (36) |

| Slightly religious, n (%) | 17 (25) |

| Not at all religious, n (%) | 13 (19) |

| Spirituality | |

| Very spiritual, n (%) | 26 (38) |

| Moderately spiritual, n (%) | 24 (35) |

| Slightly spiritual, n (%) | 14 (20) |

| Not at all spiritual, n (%) | 5 (7) |

| Frequency of organized religious activity | |

| At least once a month, n (%) | 25 (36) |

Married patients include only patients who are currently married and excludes patients who are divorced or widowed.

Three patients (4%) refused to answer information about their income and 2 patients (3%) did not know their income.

A measure of functional status that is predictive of survival, where 0 is dead and 100 is perfect health. A score of 70 is “caring for self, not capable of performing normal activity or work.”

A validated measure of quality of life with 4 domains: physical well-being, psychological, existential, and social support. Overall McGill quality of life possible scores 0 to 160. Physical QOL possible scores 0 to 20, psychological QOL possible scores 0 to 40, existential QOL possible scores 0 to 60, and support QOL possible scores 0 to 20. The overall QOL includes additional items that are not included in any of the 4 listed subdomains.

Protestant includes all other non-Catholic Christian denominations.

Of the patients with other religious traditions, 1 (1%) was Muslim, 3 (4%) were Buddhist, 2 (3%) professed no religious tradition, and 4 (6%) responded “other.”

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Spiritual concerns

The frequency with which patients endorsed SCs, categorized as either spiritual struggle or spiritual seeking, is described in Table 2. Most patients (86%) endorsed one or more SCs, with a median of 4 SCs per patient. The majority (58%) experienced one or more forms of spiritual struggle, and most (82%) experienced one or more forms of spiritual seeking. The most common spiritual struggle items were “wondering why God has allowed this to happen” (30%) and “wondering whether God has abandoned me” (29%). The most common spiritual seeking items were “seeking a closer connection to God” (54%) and “thinking about what gives meaning to life” (54%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Spiritual Struggles, Spiritual Seeking, and Total Spiritual Concerns among Advanced Cancer Patients (n = 69)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Spiritual strugglea | 40 (58) |

| Doubting your belief in God or in your faith | 14 (20) |

| Being angry with God | 17 (25) |

| Wondering why God has allowed this to happen | 21 (30) |

| Wondering whether God has abandoned me | 20 (29) |

| Feeling that cancer is God's way of punishing me for my sins and lack of devotion | 15 (22) |

| Questioning God's love for me | 17 (25) |

| Wondering what I did for God to punish me like this | 15 (22) |

| Wondering whether my church has abandoned me | 8 (12) |

| I've been thinking that the devil made this happen | 9 (13) |

| Questioning the power of God | 17 (25) |

| Other spiritual strugglesb | 2 (3) |

| Spiritual seekingc | 57 (83) |

| Seeking a closer connection with God or with your faith | 37 (54) |

| Finding meaning in the experience of your cancer | 35 (51) |

| Thinking about forgiveness (being forgiven or forgiving others) | 33 (48) |

| Thinking about what gives meaning to life | 37 (54) |

| Other spiritual seekingd | 11 (16) |

| Any spiritual concernse | 59 (86) |

This includes all patients who reported at least one spiritual struggle item.

Two patients expressed spiritual struggles other than the choices offered, including anger at God for loss of control and asking “why.”

This includes all patients who reported at least one spiritual seeking item.

Eleven patients expressed other forms of spiritual seeking. These included: seeking greater religious practice (2), reflection on spiritual beliefs (3), seeking to live life to the fullest despite cancer (1), desiring to give to others less fortunate (1), praying for the well-being of oneself or others (2), and finding meaning and peace (2).

This includes all patients who reported at least one spiritual seeking or at least one spiritual struggle item.

The relationship of spiritual concerns to patient quality of life

Total spiritual struggle, spiritual seeking, and SCs were each associated with worse psychological well-being (Table 3). The relationships of each SC to patient psychological well-being are also shown in Table 3, with the majority of concerns associated with worse patient psychological well-being. Doubting one's belief in God was one of the strongest predictors of poor psychological QOL (β = −7.55, p = 0.01 in both the adjusted and unadjusted models) and was also a common struggle for patients.

Table 3.

Associations of Advanced Cancer Patient Spiritual Concerns with Psychological Quality of Life (n = 69)

| Univariate Model | Model adjusted for Karnofsky performance status | Model adjusted for Karnofsky performance status and spirituality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual concerns | β | P | β | P | β | P |

| Total spiritual struggles | −1.2 | <0.001 | −1.13 | 0.01 | −1.11 | 0.01 |

| Doubting your belief in God or in your faith | −7.55 | 0.01 | −7.04 | 0.02 | −7.55 | 0.01 |

| Being angry with God | −6.83 | 0.01 | −6.32 | 0.02 | −6.44 | 0.02 |

| Wondering why God has allowed this to happen | −4.92 | 0.05 | −4.27 | 0.1 | −4.64 | 0.07 |

| Wondering whether God has abandoned me | −6.19 | 0.02 | −6.06 | 0.02 | −5.99 | 0.02 |

| Feeling that the cancer is God's punishment for sins and lack of devotion | −4.78 | 0.1 | −4.39 | 0.13 | −3.79 | 0.02 |

| Questioning God's love for me | −6.34 | 0.02 | −5.93 | 0.03 | −5.90 | 0.03 |

| Wondering what I did for God to punish me like this | −4.96 | 0.09 | −4.50 | 0.12 | −4.25 | 0.14 |

| Wondering whether my church has abandoned me | −5.58 | 0.15 | −5.29 | 0.16 | −4.85 | 0.20 |

| I've been thinking that the devil made this happen | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 0.95 |

| Questioning the power of God | −7.64 | <0.001 | −7.20 | 0.01 | −6.87 | 0.01 |

| Other spiritual strugglesa | −27.12 | <0.001 | −25.73 | 0.01 | −27.94 | <0.001 |

| Total spiritual seeking | −0.79 | 0.3 | −9.10 | 0.24 | −1.67 | <0.05 |

| Seeking a closer connection with God (or your faith) | −1.41 | 0.55 | −0.82 | 0.73 | −1.93 | 0.44 |

| Finding meaning in the experience of cancer | −0.38 | 0.87 | −0.75 | 0.75 | −2.10 | 0.41 |

| Thinking about forgiveness (being forgiven or forgiving others) | −1.72 | 0.47 | −1.53 | 0.51 | −2.66 | 0.28 |

| Thinking about what gives meaning to life | −3.42 | 0.14 | −4.17 | 0.07 | −5.75 | 0.02 |

| Other spiritual seekingb | −0.75 | 0.81 | −2.42 | 0.46 | −2.67 | 0.42 |

| Total spiritual concerns | −1.04 | <0.001 | −1.00 | <0.001 | −1.06 | <0.001 |

Two patients expressed spiritual struggles other than the choices offered, including anger at God for loss of control and asking “why.”

Eleven patients expressed other forms of spiritual seeking. These included: seeking greater religious practice (2), reflection on spiritual beliefs (3), seeking to live life to the fullest despite cancer (1), desiring to give to others less fortunate (1), praying for the well-being of oneself or others (2), and finding meaning and peace (2).

B, β coefficient.

In adjusted models, total spiritual struggle, spiritual seeking, and SCs were not found to be a predictors of existential QOL (β = −0.25, p = 0.56; β = −0.18, p = 0.85; and β = −0.21, p = 0.58, respectively), physical QOL (β = 0.11, p = 0.59; β = −0.52, p = 0.20; and β = −0.01, p = 0.95, respectively), or social support (β = 0.14, p = 0.31; β = −0.05, p = 0.86; and β = −0.1, p = 0.42, respectively). Total spiritual struggles and spiritual seeking were not predictive of overall QOL scores in adjusted models (β = −1.13, p = 0.24; β = −2.72, p = 0.17), although in the adjusted model there was a trend toward worse overall QOL with greater total SCs (β = −1.24, p = 0.13).

Analyses of the relationships of individual SCs to overall QOL showed two notable associations. First, the spiritual seeking item “seeking what gives meaning to life” was significantly associated with worse overall QOL in adjusted analyses (β = −12.94, p = 0.02). Second, in adjusted analyses there was a trend toward worse overall QOL among patients who reported that they felt abandoned by God (β = −10.63, p = 0.07).

Predictors of spiritual needs and patients' desires for spiritual care

Univariate predictors found that younger age was the only statistically significant predictor of total SCs (p = 0.006). Notably, patient religiosity, spirituality, and proximity to death from the time of the interview were not significantly associated with a greater patient burden of SCs.

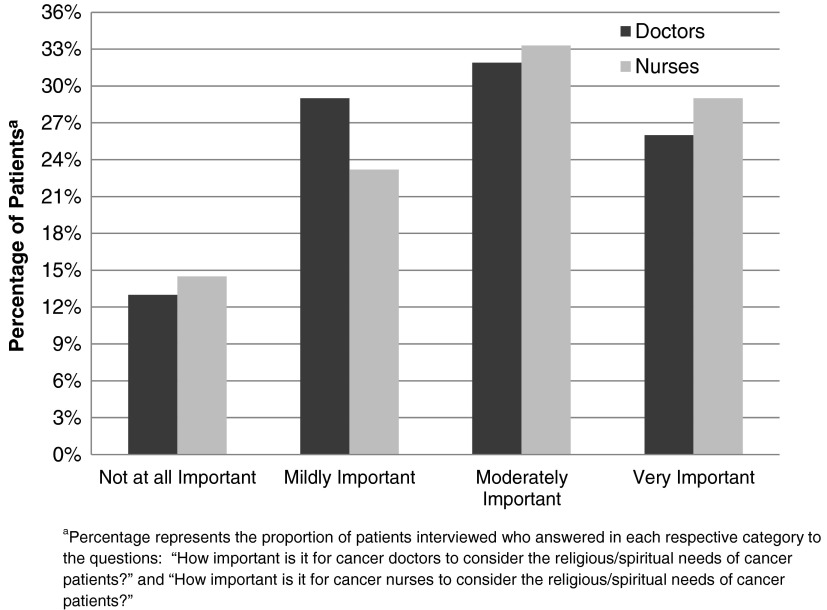

Most patients considered attention to SCs to be an important part of cancer care (Fig. 1), with 58% indicating that it is moderately or very important for doctors and 62% indicating that it is moderately or very important for nurses to consider the SCs of cancer patients. A minority of patients thought that it was not important for doctors (13%) or nurses (15%) to consider the SCs of cancer patients.

FIG. 1.

Advanced cancer patients' perceptions of the importance of health care providers considerations of patient religious/spiritual needs as part of cancer care (n = 69).

Univariate predictors of patients' desires for health care providers to consider SCs as part of cancer care are shown in Table 4. High spirituality (patients considering themselves moderately or very spiritual) followed by high religiousness (patients categorized as moderately or very religious) were the strongest predictors of patients' desires for health care professionals to consider their SCs. Additionally, female gender, greater education, and higher income levels were significant univariate predictors of patients' desires for health care providers to consider SCs as part of cancer care. Although patients endorsing more spiritual seeking items reported greater perceived importance of attention to SCs in the medical setting, spiritual struggle items and total SCs were not associated with patients' desires for spiritual care.

Table 4.

Univariate Predictors of Advanced Cancer Patients' Perceptions of the Importance of Health Care Providers' Considerations of Patient Religious/Spiritual Needs As Part of Cancer Care (n = 69)a

| Importance of physicians considering patient religious/spiritual needs as part of cancer care | β Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Male | −1.37 | 0.01 |

| Education, years | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| Income, greater than $50,000b | 1.04 | <0.05 |

| Moderately or very spiritualc | 2.72 | <0.001 |

| Moderately or very religiousd | 1.61 | 0.002 |

| Number of spiritual seeking items endorsed | 0.48 | 0.002 |

| Importance of nurses considering patient religious/spiritual needs as part of cancer care | β Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Male | −1.63 | 0.001 |

| Education, years | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| Income, greater than $50,000b | 0.94 | 0.08 |

| Moderately or very spiritualc | 2.59 | <.001 |

| Moderately or very religiousd | 1.47 | 0.005 |

| Number of spiritual seeking items endorsed | 0.41 | 0.007 |

Importance of physicians' and nurses' considerations of patient religious/spiritual needs as part of cancer care scored (0–3) as not at all, mildly, moderately, or very important. All continuous predictors were dichotomized by a median split. This figure includes only those variables that were found to be significant or approaching significance in univariate analysis (p < 0.10). Other variables tested but not meeting these criteria included: race, marital status, education, Karnofsky performance status, time between interview and death, religious tradition, religious activities, total spiritual concerns, and total spiritual struggle items endorsed.

Three patients (4%) refused to answer information about their income and 2 patients (3%) did not know their income. Reference group are patients who reported earning less than $50,000 a year.

Spirituality dichotomized (median split) to moderately or very spiritual versus not at all or slightly spiritual.

Religiousness dichotomized (median split) to moderately or very religious versus not at all or slightly religious.

Discussion

This preliminary study has demonstrated that SCs are common in the setting of advanced cancer. Furthermore, patients experiencing SCs, whether spiritual struggles (e.g., feeling abandoned by God) or spiritual seeking (e.g., thinking about what gives meaning to life) experience poorer psychological QOL. Individual SCs, including the spiritual seeking item “thinking about what gives meaning to life” endorsed by 54% of patients was significantly associated with worse overall QOL. Similarly, the spiritual struggle item “feeling abandoned by God” endorsed by 29% of patients demonstrated a trend toward being associated with worse overall QOL. These findings suggest that SCs have important associations with advanced cancer patient QOL, in particular for younger patients. This study also demonstrates that most patients consider attention to SCs to be an important part of cancer care, with greater spirituality or religiousness being the strongest predictors of patients' desires for health care professionals to consider their SCs in the advanced cancer setting.

Previous studies of SCs in cancer patient populations have shown similar rates of SCs.8,12 For example, Moadel et al.8 demonstrated that among cancer patients, SCs are present in 75%, with a median of two SCs per patient. Astrow and colleagues12 noted a similar proportion of reported SCs (73%) in a cancer patient population. These slightly lower rates of reported SCs may in part be due to differing assessment tools as well as differing patient populations, with the present study examining incurable cancer patients actively requiring palliative therapy as compared with these prior studies of patients with all stages of cancer. In addition, previous studies have similarly demonstrated that spiritual struggles, as defined by Pargament's negative religious coping items,16 negatively impact QOL.6,19,20 However, our study additionally shows that forms of spiritual seeking are likewise associated with worse patient QOL. The association of spiritual seeking as well as spiritual struggle with decrements in patient QOL can be interpreted in a variety of ways, particularly given the cross-sectional nature of the analysis. For example, SCs of any type may reflect an underlying lack of spiritual peace that negatively impacts patient overall QOL, a hypothesis supported by a study reported by Steinhauser et al.10 This study showed that among 44 aspects of QOL at the end of life (EOL), being at peace with God and being free from pain together ranked highest in importance by patients. Furthermore, a meaning-centered psychotherapy intervention at the EOL developed by Breitbart et al. has been shown to prospectively improve advanced cancer patient psychological well-being,21 suggesting that need for meaning-making may directly impact patient psychological QOL. In contrast, the associations noted between SCs and QOL may be due to the fact that SCs—for example, seeking meaning, feeling abandoned—are markers of diminished psychological and overall well-being. For example, meaninglessness and feelings of abandonment are common in depression. However, future prospective studies measuring specific forms of psychological distress (e.g., depression) are needed to further define these relationships.

Other studies have demonstrated that in the EOL setting a majority of patients desire attention to R/S issues as part of medical care because R/S plays an important and positive role for many in the cancer experience.9 For example, in a study of ambulatory pulmonary outpatients, 66% stated that they would want their physician to inquire about their R/S beliefs if they became gravely ill.22 King et al., in a study of hospitalized patients demonstrated that 77% desired attention to SCs as part of care.23 Although a majority of patients desire incorporation of spiritual care into medical care, it is important to also recognize a notable minority who do not consider spiritual care from physicians and nurses as having a role in medical care, seen both in the present sample and other studies.12,22 Our analyses of predictors of desires for spiritual care from physicians and nurses confirm that knowing patients' degree of R/S and inquiring about the presence of SCs are key to guiding spiritual care provision. Hence, a simple spiritual screening—such as Puchalski's FICA spiritual screening tool24—included as part of an initial comprehensive medical assessment, can provide key information to guide spiritual care, by characterizing patient R/S and assessing SCs to inform patient preferences for spiritual care.

This study highlights the importance of spiritual care as a core component of palliative care as outlined by both national7 and international11 guidelines. Spiritual care includes initial and ongoing spiritual assessments of patients with advanced illness, attention to SCs, and other interventions such as promoting opportunities for life review and life completion tasks.7 Further study is needed to understand when and how spiritual assessment and attention to patients' SCs and goals should be offered by an interdisciplinary health care team that has adequate training in assessing and addressing SCs of patients faced with life-threatening illness.25

A major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which made it difficult to fully understand the associations among SCs and dimensions of patient QOL and did not provide information about how SCs might evolve through the EOL experience. Additionally, the developed SCs scale was not validated. Furthermore, the generalizability of the findings was limited by the fact that the study sample comprised advanced cancer patients from a single, U.S. region who were primarily Caucasian and Judeo-Christian in orientation. Future studies are required to delineate the relationships among SCs, psychological states such as depression, and patient well-being, as well as to characterize how SCs may evolve. Furthermore, prospective assessment of spiritual care interventions is required to determine their impact in addressing SCs on patient QOL.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that SCs are common among advanced cancer patients, and that they are associated with poorer psychological well-being. Furthermore, most advanced cancer patients believe that spiritual needs should be addressed as part of cancer care. These findings underscore the important role of spiritual care in palliative care, as outlined in current national7 and international11 palliative care guidelines. Given the diverse expertise required to provide spiritual care, these findings highlight the need for the development of interdisciplinary teams—for example, physicians, nurses, chaplains, and mental health clinicians.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award to Dr. Tracy Balboni.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Balboni TA. Vanderwerker LC. Block SD. Paulk ME. Lathan CS. Peteet JR. Prigerson HG. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig HG. Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:213–224. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199804)13:4<213::aid-gps755>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts JA. Brown D. Elkins T. Larson DB. Factors influencing views of patients with gynecologic cancer about end-of-life decisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:166–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phelps AC. Maciejewski PK. Nilsson M. Balboni TA. Wright AA. Paulk ME. Trice E. Schrag D. Peteet JR. Block SD. Prigerson HG. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady MJ. Peterman AH. Fitchett G. Mo M. Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-oncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman AC. Simonton S. Latif U. Spohn R. Tricot G. Religious struggle and religious comfort in response to illness: Health outcomes among stem cell transplant patients. J Behav Med. 2005;28:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson CJ. Rosenfeld B. Breitbart W. Galietta M. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:213–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moadel A. Morgan C. Fatone A. Grennan J. Carter J. Laruffa G. Skummy A. Dutcher J. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psycho-oncology. 1999;8:378–385. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alcorn SR. Balboni MJ. Prigerson HG. Reynolds A. Phelps AC. Wright AA. Block SD. Peteet JR. Kachnic LA. Balboni TA. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn't be here today”: Religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinhauser KE. Christakis NA. Clipp EC. McNeilly M. McIntyre L. Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Palliative Care: Symptom Management and End of Life Care IMoAaAIWHO. 2004. http://who.int/hiv/pub/imai/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf. [May 15;2009 ]. http://who.int/hiv/pub/imai/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf

- 12.Astrow AB. Wexler A. Texeira K. He MK. Sulmasy DP. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients' perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5753–5757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The George H Gallup International Institute. Conducted for the Nathan Cummings Foundation and the Fetzer Institute. Princeton: 1997. Spiritual beliefs, the dying process, a report of a national survey. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religion and Coping : Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pargament KI. Koenig HG. Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SR. Mount BM. Bruera E. Provost M. Rowe J. Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: A multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SR. Mount BM. Strobel MG. Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9:207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarakeshwar N. Vanderwerker LC. Paulk E. Pearce MJ. Kasl SV. Prigerson HG. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:646–657. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gall TL. Guirguis-Younger M. Charbonneau C. Florack P. The trajectory of religious coping across time in response to the diagnosis of breast cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18:1165–1178. doi: 10.1002/pon.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitbart W. Rosenfeld B. Gibson C. Pessin H. Poppito S. Nelson C. Tomarken A. Timm AK. Berg A. Jacobson C. Sorger B. Abbey J. Olden M. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehman JW. Ott BB. Short TH. Ciampa RC. Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1803–1806. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King DE. Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puchalski C. Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:129–137. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puchalski C. Ferrell B. Virani R. Otis-Green S. Baird P. Bull J. Chochinov H. Handzo G. Nelson-Becker H. Prince-Paul M. Pugliese K. Sulmasy D. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]