Abstract

Three series (6, 13, and 14) of new diarylaniline (DAAN) analogues were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for anti-HIV potency, especially against the E138K viral strain with a major mutation conferring resistance to the new-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor drug rilpivirine (1b). Promising new compounds were then assessed for physicochemical and associated pharmaceutical properties, including aqueous solubility, log P value, and metabolic stability, as well as predicted lipophilic parameters of ligand efficiency, ligand lipophilic efficiency, and ligand efficiency-dependent lipophilicity indices, which are associated with ADME property profiles. Compounds 6a, 14c, and 14d showed high potency against the 1b-resistant E138K mutated viral strain as well as good balance between anti-HIV-1 activity and desirable druglike properties. From the perspective of optimizing future NNRTI compounds as clinical trial candidates, computational modeling results provided valuable information about how the R1 group might provide greater efficacy against the E138K mutant.

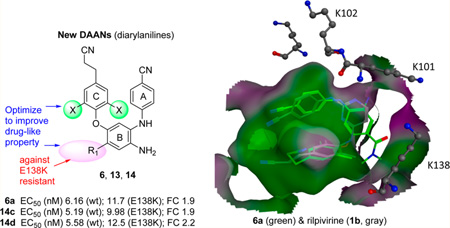

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

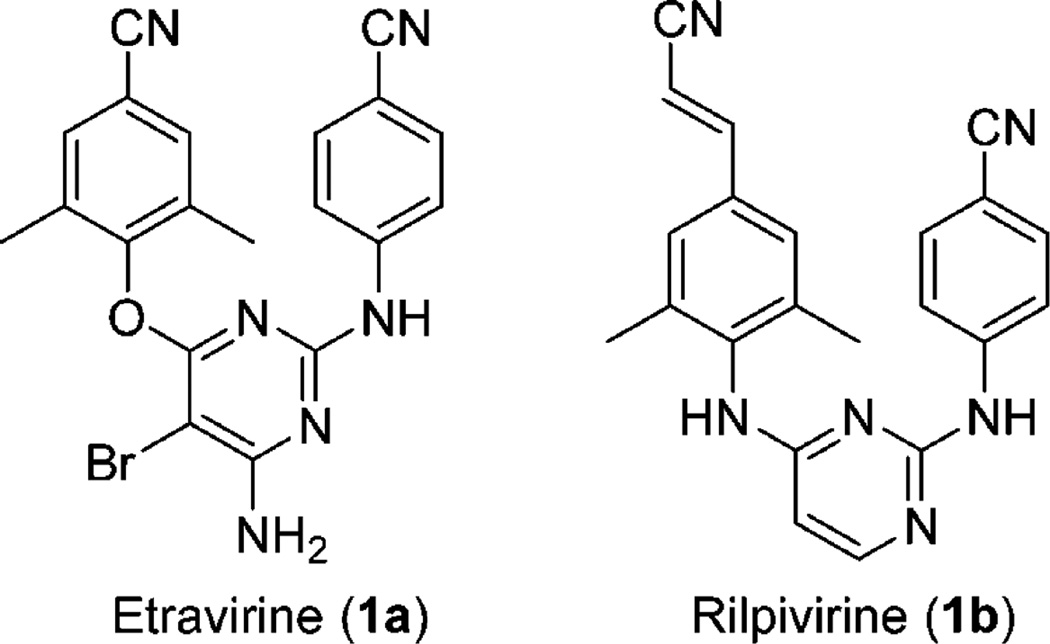

Because of their high potency and low toxicity, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) are used as key drugs in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)1 for the treatment of HIV infection and AIDS. However, resistance to some drugs, especially to the early NNRTI drugs nevirapine, delavirdine, and efavirenz, has occurred as a result of rapidly developing mutations of the viral NNRTI binding site. To address this major problem, two next-generation NNRTI drugs, etravirine (TMC125, 1a)2 and rilpivirine (TMC278, 1b)3 (Figure 1), were successfully developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 and 2011, respectively. Compounds 1a and 1b belong to the same diarylpyrimidine (DAPY) family, possess extremely high potency against the wild type and a broad spectrum of mutated NNRTI strains resistant to early NNRTI drugs,4 and also present a higher genetic barrier against HIV-1 resistance,5, 6 most likely resulting from their molecular flexibility. However, because of the high mutation rate of HIV-1 RT and the lack of intrinsic exonucleolytic proofreading activity, new resistance profiles associated with 1a and 1b are also being observed in patients.7, 8 These viral mutations are distinct from each other9 as well as distinct from those seen with the early NNRTI drugs. Consequently, novel NNRTI drugs with high potency and different molecular scaffolds are still needed to overcome new drug resistance regimes associated with the new-generation NNRTI anti-HIV drugs 1a and 1b and to provide more efficacious therapies and treatment options.

Figure 1.

New-generation HIV-1 NNRTI drugs approved by the U.S. FDA.

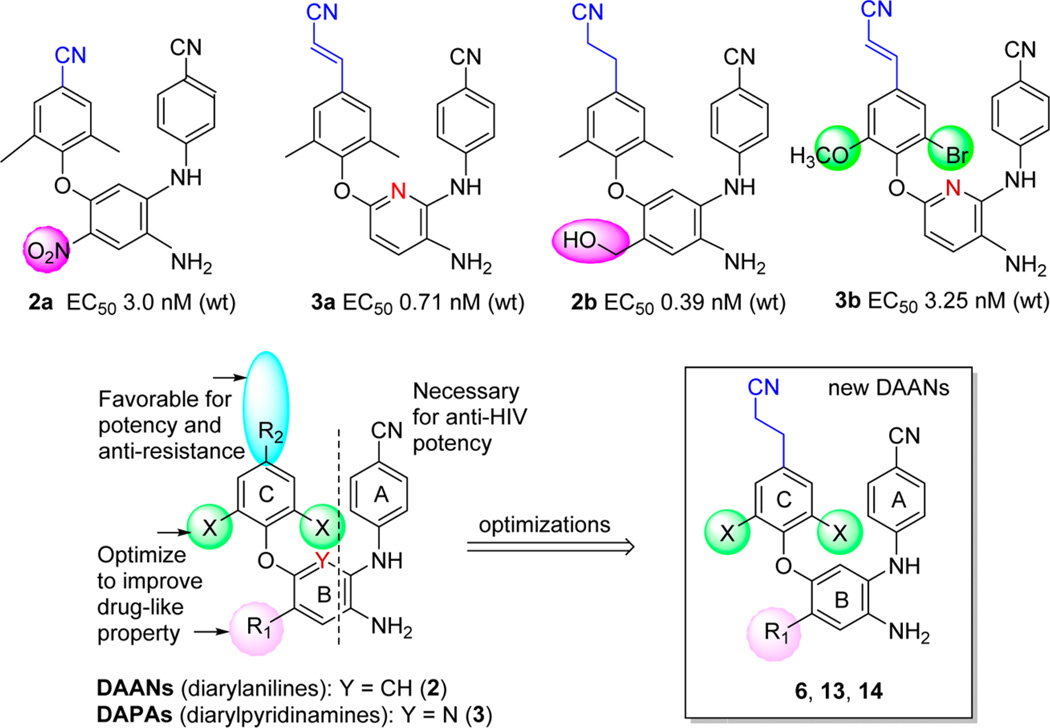

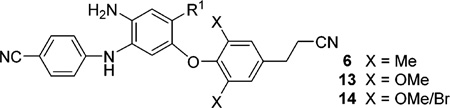

In our prior studies of novel HIV-1 NNRTI agents, we discovered two series of extremely potent anti-HIV NNRTI agents, diarylanilines (DAANs, 2)10 and diarylpyridiamines (DAPAs, 3),11, 12 as shown in Figure 2. The new chemo-type scaffolds have topologic shape and molecular flexibility similar to those of new-generation NNRTI drugs 1a and 1b. The initial leads 2a and 3a exhibited high anti-HIV potency against wild-type HIV-1 replication with low to subnanomolar EC50 values of 3.0 and 0.71 nM, respectively, comparable to those of 1a (EC50 = 1.5 nM) and 1b (EC50 = 0.51 nM) in the same assays.10, 12 However, very low bioavailability (F% < 3) in rats impeded their further development. Subsequently, multiple structural modifications were introduced to identify structure-activity relationship (SAR) and structure-property relationship (SPR) correlations for DAANs and DAPAs as new HIV-1 NNRTI agents. The subsequent leads 2b13 (DAAN) and 3b14 (DAPA) exhibited not only extremely high potency against both wild-type (EC50 values of 0.39 and 3.25 nM, respectively) and drug-resistant (EC50 values of 1.8–3.4 and 3.5–6.9 nM, respectively) viral replication but also improved druglike properties. Lead 2b had a desirable log P value of 3.68 and a high water solubility of 90 µg/mL at pH 2.0, but its higher metabolism and instability in various solvents prompted continued structural optimization. On the other hand, lead 3b had high antiresistance potency, with especially low resistance fold changes (FC = 1.1–2.1) for K101E and E138K viral strains resistant to new drugs 1a and 1b, respectively, compared with that for wild-type NL4-3 virus. This interesting advantage provided the opportunity to explore compounds capable of overcoming the drug resistance associated with 1a and 1b. Therefore, current optimization efforts have been aimed at discovering new DAANs as potential drug candidates with high antiresistance potency and good balance between antiviral activity and multiple druglike properties. Guided by the prior SAR results, we designed and synthesized three new series (6, 13, and 14) of DAAN derivatives and evaluated them against HIV-1 wild-type virus and the E138K variant, which contains the most frequent mutation conferring resistance to 1b,15 as well as other resistant viral strains. Meanwhile, essential druglike properties and parameters were also assessed and predicted. Herein, we reported our new results and further discussion of SAR and SPR correlations for DAANs and DAPAs.

Figure 2.

Prior leads 2 and 3, known SARs, and the current lead optimization strategy.

DESIGN

As demonstrated in Figure 2, while potent NNRTI DAANs and DAPAs differ by having a benzene and pyridine ring, respectively, as the central ring (B-ring), they also have three of the same known pharmacophores, a p-cyanoaniline moiety (A-ring), the NH2 group on the central B-ring ortho to the A-ring, and a 2,4,6-trisubstituted phenoxy ring (C-ring). With good molecular flexibility and a topologic shape similar to that of 1b, these compounds can adjust their binding conformations to fit the binding site within both wild-type and mutated NNRTI binding pockets. Previous SARs revealed that a linear hydrophobic para-R2 substituent on the C-ring is favorable for potency with the following rank order: cyanoethyl > cyanovinyl > cyano. On the other hand, the R1 substituent on the central B-ring and X substituents on the C-ring can be modified to improve molecular properties without a loss of potency. Importantly, on the basis of prior molecular docking results,12 the R1 substituent on the B-ring is outside of the main NNRTI binding pocket and close to susceptible amino acid E138 on the p51 subdomain of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Thus, modification of this R1 group could provide an interaction between it and the mutated K138, or other preserved amino acid(s) nearby or on the interface between p66 and p51 subdomains, to possibly overcome mutated E138K resistance. Therefore, in the newly designed DAAN analogues (6, 13, and 14 series), continued optimizations addressed modifications of the R1 and X sub-stituents, while the p-cyanoethyl substituent (R2) on the phenoxy ring (C-ring)16 and p-cyanoaniline (A-ring) were maintained (see the formula in Figure 2). Because the R1 substituent is also associated with molecular physicochemical properties, the current optimization strategy should result in a balance between antiviral potency and multiple drug-likeness profiles, which are criteria for advancing a potential drug candidate to the clinic. Additionally, a suitable R1 side chain oriented toward the interface between the HIV-1 RT p66 and p51 subdomains could overcome the drug resistance of E138 K. The series 6 DAAN compounds incorporated various R1 groups with different shapes, volumes, and flexibilities, including amides (6a–d), alkylamines (6e–g), esters (6h,i), carbamates (6j), alkoxyethers (6k,m), and halogens (6n,p), to investigate the effects of these groups on potency, antiresistance, and druglike properties. Hetero atoms, such as O or N, in certain R1 substituents could provide additional interactions with the amino acids on interfaces between p66 and p51 subdomains of the RT enzyme via H-bonds or other forces to increase potency against the E138K mutation and improve molecular physicochemical properties, as well as related druglike properties. In addition, the X groups on the C-ring were modified for antiresistance and metabolic stability,17, 18 resulting in two small sets of new DAANs, the dimethoxy-13 series and the methoxy/bromo-14 series, with either an N-methyl carboxamide or a methyl carboxylate as the R1 substituent. These limited structural optimizations should provide a better understanding of how structure affects potency against HIV-1 wild-type and resistant viral strains, especially for the E138K mutation, as well as other drug properties, with the aim of discovering and developing potential new NNRTI drug candidates.

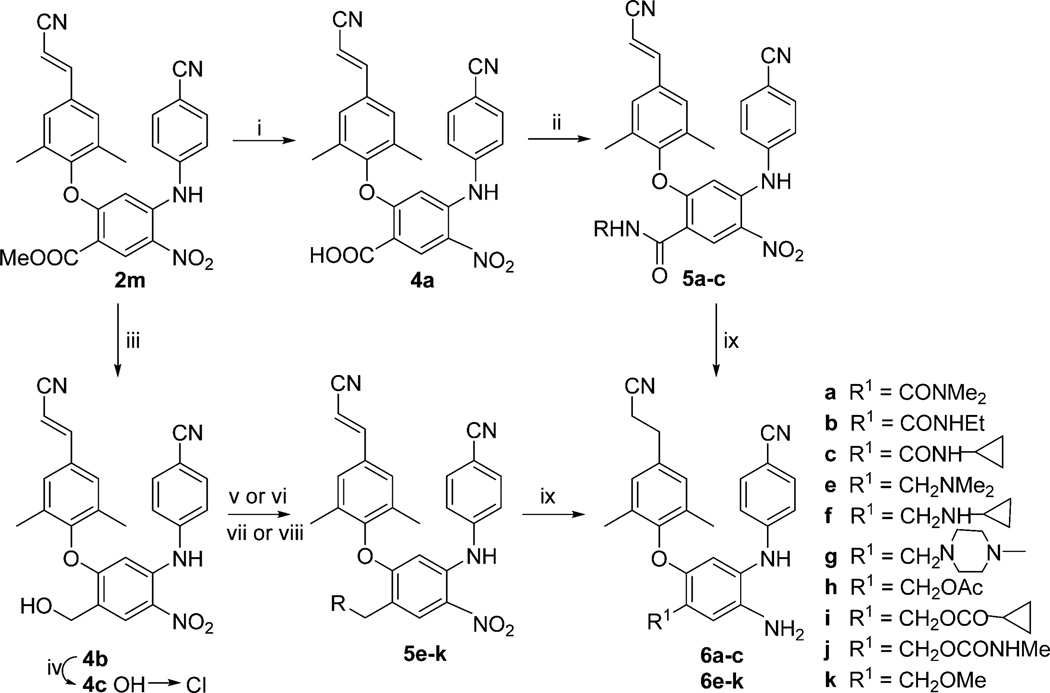

Chemistry

As shown in Scheme 1, new compounds 6a–c and 6h–n were synthesized from 2m, a prior intermediate in the synthesis of DAANs.13 The 4-ester group on the central phenyl ring in 2m was either hydrolyzed under basic conditions or reduced with LiBH4 to the corresponding carboxylic acid (4a) or hydroxymethyl (4b) derivative, respectively. Compound 4a was then treated with SOCl2 followed by amidation with different amines in THF at 0 °C to produce the 4-amido compounds 5a–c. On the other hand, treating 4b with 2,4,6-trichloro[1,3,5]triazine (TCT)19 produced the chloromethyl product 4c, which was reacted immediately with dimethylamine, cyclopropanamine, and 1-methylpiperazine to yield the corresponding 4-alkylaminomethyl compounds 5e–g, respectively. Alternatively, compound 4b was reacted with acetic anhydride, cyclopropanecarbonyl choloride, and methylcarbamic chloride to yield the corresponding reversed ester compounds 5h and 5i and carbamate compound 5j, respectively. Moreover, 4b was converted to methoxymethyl compound 5k by reaction with methanol in the presence of BiCl3 at room temperature. Next, the nitro group and the double bond of the p-cyanovinyl in intermediates 5a–c and 5e–k were reduced simultaneously by catalytic hydrogenation with Pd-C (10%) in anhydrous ethanol or EtOAc to produce the new DAAN compounds 6a–c and 6e–k, respectively.

Scheme 1a.

a(i) THF/MeOH, aq NaOH, rt, 10 h; (ii) (a) SOCl2, reflux, 4 h; (b) amine, THF, 0 °C, 0.5 h; (iii) LiBH4, THF/MeOH, 0 °C, 7 h; (iv) 2,4,6-trichloro[1,3,5]triazine, DMF/CH2Cl2, rt, 4 h; (v) amine, THF, 0 °C, for 5e–g; (vi) Ac2O, NaOH(s), 100 °C, microwave, 5 min for 5h; (vii) acylchloride, CH2Cl2/Py, for 5i and 5j; (viii) MeOH, BiCl3, in CH2Cl2, rt, 4 h, for 5k; (ix) H2/Pd-C, in EtOH or EtOAc.

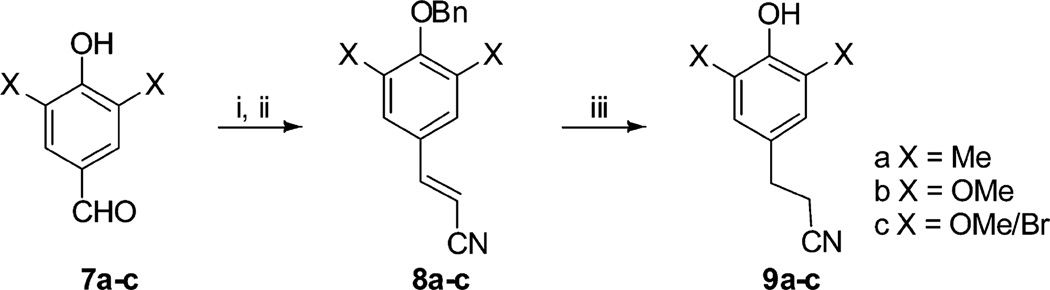

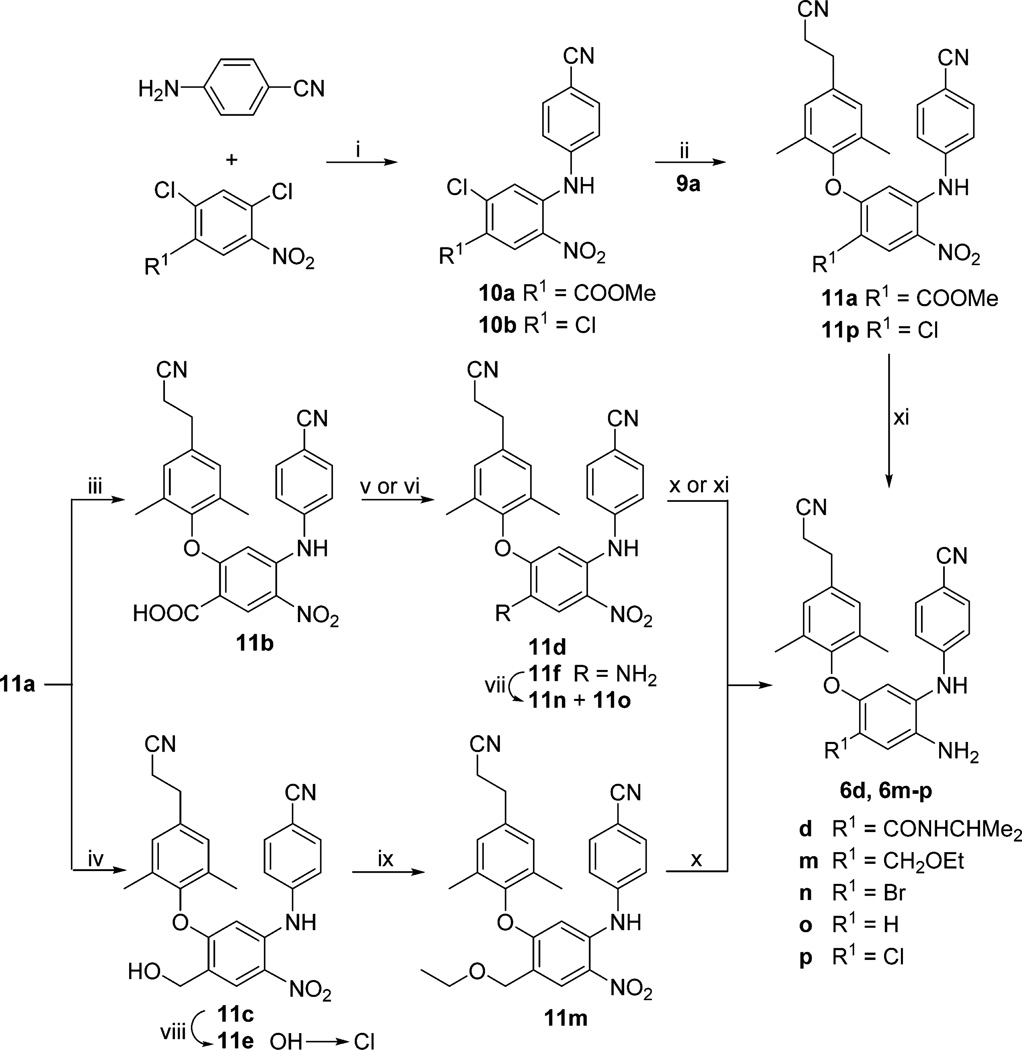

In addition, a new convergent synthetic route was explored to efficiently synthesize additional p-cyanoethylphenoxy-DAANs (Schemes 2 and 3). The C-ring building block 4-cyanoethyl-2,6- dimethyl phenol (9a) was prepared from commercial reagent 7a in three steps: benzoylation of the phenol, Wittig reaction of the aldehyde group with diethyl cyanomethylphosphonate, and deprotection by catalytic hydrogenation. Because an electrondonating p-cyanoethyl group was present, the coupling of 9a with10a, an intermediate synthesized and identified previously,10, 13 was performed easily to produce 2,4-diaryl nitrobenzene 11a in a high yield of 94%. By conversions similar to those shown in Scheme 1, 11a was converted to the carboxylic acid (11b) and hydroxymethyl (11c) compounds. Compound 11b was converted to the N-substituted carbamoyl product 11d, while 11c was modified successively to the chloromethyl (11e) and ethoxymethyl (11m) nitrodiarylanilines. By Curtius rearrangement,20 the 4-carboxylic acid group of 11b was converted to a 4-amino moiety in 11f, which underwent diazonization followed by reaction with cuprous bromide to produce the desired 4-bromo product 11n and the nonbrominated byproduct 11o. Alternatively, coupling of 9a with 10b was performed under microwave irradiation in DMF in the presence of K2CO3 at 110 °C for 10 min to produce 4-chloro compound 11p (R1 = Cl). Finally, nitro compounds 11d and 11m were reduced conveniently by catalytic hydrogenation to corresponding amino products 6d and 6m, respectively. However, halogenated nitro compounds 11n–p were reduced by using the mild reductive reagent Fe/NH4Cl to obtain corresponding amino compounds 6n–p, respectively. This reaction showed a clear color change from yellow to colorless to identify the reaction’s end.

Scheme 2a.

a(i) BnCl, K2CO3 or Et3N, in CH3CN, reflux, 3 h; (ii) (EtO)2PCO-(CH2CN), t-BuOK/THF, 0 °C, 1 h; (iii) H2/Pd-C in EtOAc or EtOH.

Scheme 3a.

a(i) Cs2CO3/DMF, 80 °C, microwave, 20 min; (ii) K2CO3/DMF, 110 °C, heating for 4 h or microwave, 20 min; (iii) aq NaOH, THF/MeOH, rt, 8 h; (iv) LiBH4, THF/MeOH, 0 °C, 7 h; (v) (a) SOCl2, reflux, 3 h; (b) amine/THF, 0 °C, 0.5–1 h; (vi) (a) DPPA/Et3N/THF, rt, 3 h; (b) H2O, reflux, 3 h; (vii) (a) HBr/NaNO3/H2O, 5 °C, 1 h; (b) CuBr/HBr, 5 °C, 3 h; (viii) 2,4,6-trichloro[1,3,5]triazine, DMF, CH2Cl2, rt, 4 h; (ix) EtOH, microwave at 100 °C, 20 min; (x) H2/Pd-C in EtOAc, 2–3 h, rt; (xi) Fe/NH4Cl, THF/MeOH/H2O, reflux, 3 h.

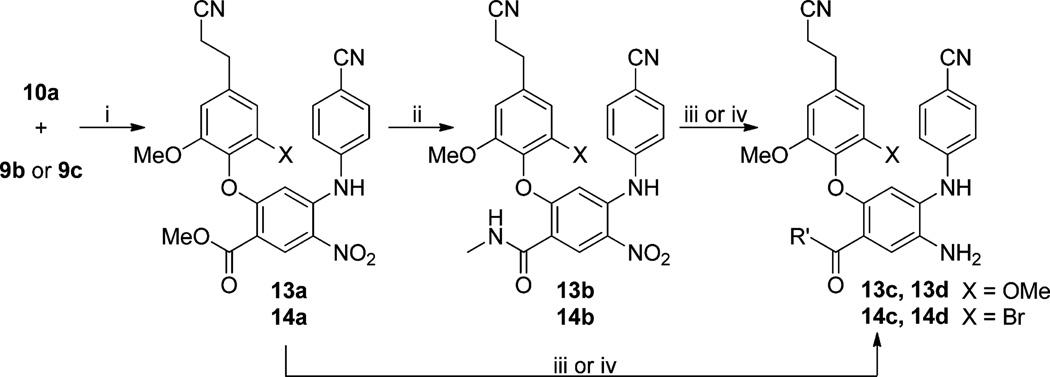

With the same method that was used for the preparation of 9a, building blocks 4-cyanoethyl-2,6-dimethoxy phenol (9b) and 2-bromo-4-cyanoethyl-6-methoxyphenol (9c) were synthesized from commercially available 7b and 7c, respectively. As described in Scheme 4, compounds 13 (X = OMe) and 14 (X = OMe/Br) were synthesized from compound 10a by coupling with 9b or 9c to produce corresponding esters 13a and 14a followed by amidation with methylamine to yield 13b and 14b, respectively. Similar to previous reductions, the 4-nitro in compounds 13a and 13b was reduced by catalytic hydrogenation, whereas halogenated compounds 14a and 14b were reduced with Fe/NH4Cl to generate corresponding DAANs 13c, 13d, 14c, and 14d, respectively. All new target compounds in the 6, 13, and 14 series were identified by 1H NMR and mass spectrometry data.

Scheme 4a.

a(i) K2CO3/DMF, 120 °C, 4 h; (ii) aq CH3NH2/THF, 40 °C, 4 h; (iii) H2/Pd-C in EtOAc for 13; (iv) Fe/NH4Cl, THF/MeOH/H2O, reflux, for 14.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Antiviral Activity and SAR Analysis

All new DAAN compounds (6, 13, and 14 series) were evaluated against wild-type HIV-1 (NL4-3 and IIIB) and resistant viral strain (E138K, A17, and K101E) replication in TZM-bl (NL4-3 and E138K) and MT-2 (IIIB) cell lines, respectively. Their anti-HIV potency (EC50, as measured by a luciferase gene expression assay29) and cytotoxicity (CC50) as well as selective index (SI) data are summarized in Table 1. As expected, with the exception of 6d and 6g, most of the 6 series compounds with various R1 substituents exhibited extremely high potency against wild-type HIV-1 NL4-3 replication in TZM-bl cell lines with low nanomolar EC50 values ranging from 0.53 to 16.0 nM. These results were consistent with our previous findings, which indicated that the R1 group can be modified without loss of anti-HIV potency. However, the presence of very bulky R1 groups, e.g., 4-(N-isopropyl)carbamoyl in 6d and 4-(N-methylpiperazine)-carbamoyl in 6g, impeded molecular antiviral potency, resulting in EC50 values of 72 and 115 nM, respectively. We supposed that steric conflict between the bulky R1 groups and the viral amino acid residues within a limited space between the p51 and p66 domains might affect intermolecular affinity and binding, leading to reduced potency. Interestingly, the three most potent compounds, 6c (EC50 = 2.00 nM), 6f (EC50 = 0.53 nM), and 6i (EC50 = 1.63 nM), all contain a cyclopropyl moiety at the end of their R1 side chains; this moiety might have a suitable shape and volume to insert into a cleft between the p66 and p51 subdomains, thereby increasing molecular affinity. When the two X groups on the C-ring were changed, the dimethoxy-DAANs [13c (R = COOCH3) and 13d (R = CONHCH3)] were at least 20-fold less potent than the corresponding bromo/ methoxy-DAANs (14c and 14d). Indeed, compounds 14c and 14d exhibited similar high potency (EC50 values of 5.19 and 5.58 nM, respectively) against wild-type NL4-3 virus replication and were almost as potent as the prior corresponding dimethyl-DAANs 2c (EC50 = 4.32 nM) and 2d (EC50 = 2.73 nM).13 Therefore, molecular potency could be maintained by replacing the two methyl groups (X) on the C-ring with methoxy and bromo groups, but not with two methoxy groups. Thus, appropriate X groups are needed to achieve a favorable binding conformation of the C-ring moiety.

Table 1.

Anti-HIV Activity Data of 6, 13, and 14 Series against Wild-Type HIV-1 and Mutated Strains

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | EC50 (nM)a |

FCe [K101Ed]f |

EC50(nM)b |

FCe | CC50b, g (MM) |

SIh | |||

| NL4-3c | E138Kd | IIIBc | A17d | ||||||

| 6a | 6.16 ±1.45 | 11.7±3.74 | 1.9 | 1.59 ±0.55 | 72.2 ± 14.9 | 45 | 38.2 ±7.52 | 24,025 | |

| 6b | 4.63 ±1.39 | 8.59 ±2.64 | 1.9[4] | 17.1 ±5.47 | ND | 105 ±33.6 | 6,140 | ||

| 6c | 2.00 ± 0.60 | 22.1 ±0.00 | 11 | 9.58 ± 0.40 | ND | 121 ±36.9 | 12,630 | ||

| 6d | 72.6 ±14.3 | ND1 | — | 47.7 ±2.32 | ND | 184 ±0.61 | 3,857 | ||

| 6e | 2.73 ± 0.70 | 23.4±6.11 | 8.6 | 2.16 ± 1.17 | 2.46 ±0.19 | 1.1 | 23.8 ± 6.67 | 11,019 | |

| 6f | 0.53 ±0.13 | 25.7 ±0.00 | 48 | 6.25 ±0.13 | ND | 25.5 ±11.4 | 4,080 | ||

| 6g | 115 ±38.4 | ND | — | ND | ND | ND | — | ||

| 6h | 3.30± 1.01 | 39.1±8.60 | 12 | 0.96 ±0.12 | 4.92 ±0.12 | 3.4 | 44.8 ± 2.47 | 46,667 | |

| 6i | 1.63 ±0.44 | 23.3 ±0.00 | 14 | 23.2 ±9.73 | ND | 42.2 ±3.17 | 1,818 | ||

| 6j | 16.0 ±3.41 | 93.8 ±32.0 | 5.8 | 8.32±0.12 | ND | 46.8 ± 1.40 | 5,625 | ||

| 6k | 1.45 ±0.44 | 13.3 ±0.00 | 9.2 | 3.25 ±0.23 | 2.95 ±0.50 | 0.9 | >200 | >61,538 | |

| 6m | 14.3 ±3.17 | 88.4 ±21.1 | 6.2 | 3.76 ±0.37 | 46.6 ±1.93 | 12 | 194 ±4.80 | 51,596 | |

| 6n | Br | 3.26 ±0.94 | 65.2 ±24.1 | 20 | 0.49 ±0.17 | 13.9 ±2.34 | 26 | 84.8 ±16.9 | 160,000 |

| 6o | H | 16.0 ±4.71 | 113 ±23.0 | 7.1 | 11.6 ±0.58 | ND | >200 | >17,241 | |

| 6p | Cl | 11.3 ±3.36 | 19.7 ±5.53 | 1.7[3.3] | 1.65 ±0.03 | 4.49 ±0.14 | 2.7 | 10.4 ±0.63 | 6,303 |

| 13c | 102 ±25.4 | ND | — | 329 ±91.2 | ND | 128 ±2.91 | 389 | ||

| 13d | 178 ±38.1 | ND | — | 137 ±8.46 | ND | 42.6 ±0.58 | 311 | ||

| 14c | 5.19±1.33 | 9.98 ±3.07 | 1.9 | <0.122 | ND | 10.1 ±0.20 | >82,787 | ||

| 14d | 5.58± 1.13 | 12.5 ±4.04 | 2.2 | 2.10 ±0.80 | 29.3 ±0.3 | 14 | 52.4 ±2.30 | 24,952 | |

| 2ci | 4.32 ± 1.54 | 7.52 ±2.71 | 1.7 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 2.8 ±1.3 | 14 | 85.5 ±14.7 | 427,500 | |

| 2dj | 2.73 ± 0.44 | 10.2 ±3.90 | 3.7[3.8] | 1.39 ±0.39 | 4.20 ±0.38 | 3.0 | >200 | >143,885 | |

| 1b | 0.52 ±0.14 | 5.20 ±1.60 | 10[6.5] | 0.49 ±0.17 | 9.03 ± 0.74 | 18 | >30 | >61,224 | |

Concentration of compound that causes 50% inhibition of viral infection, presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and determined in at least triplicate against HIV-1 virus in TZM-bl cell lines.

Against HIV-1 virus in MT-2 cells.

NL4-3 and IIIB are wild-type HIV-1 viral strains.

Resistant viral strains E138K and K101E mutated in the HIV-1 RT non-nucleoside inhibitor binding pocket (NNBP). A17 from NIH is the multi-NRTI-resistant strain with mutations K103N and Y181C and is highly resistant to NRTIs.

Resistance fold change (FC) is the EC50(E138K)/ EC50(NL4-3), EC50(K101E)/EC50(NL4-3), or EC50(A17)/EC50(IIIB) ratio.

The FC of an NL4-3 mutant with the K101E mutation in HIV-1 RT.

Concentrations that cause cytotoxicity to 50% of cells; CytoTox-Glo cytotoxicity assays (Promega) were used, and values were averaged from two independent tests.

The selective index (SI) is the CC50/EC50(IIIB) ratio.

Not determined.

Prior compounds published. See ref 13.

The active DAANs described above (6, 13, and 14 series) were also tested in the MT-2 cell line for inhibition of wild-type HIV-1 IIIB, as well as the multiple-resistant A17 viral strain, replication, and cytotoxicity. The EC50 values against two wild-type viruses (NL4-3 and IIIB) in different cellular assays showed some fluctuation, but similar potency and activity patterns were observed as shown in Table 1. Meanwhile, the low cytotoxicity (CC50 > 10 µM) of the compounds resulted in extremely high selective index values ranging from 103 to 105 (Table 1).

To evaluate our hypothesis concerning a possible link between the R1 substituent of a compound and its effectiveness against NNRTI-resistant virus, active DAAN compounds were tested against the E138K mutated viral strain, which has a major mutation conferring resistance to 1b, and the data are summarized in Table 1. Comparison of the results in the wild-type NL4-3 and drug-resistant E138K assays identified the most promising compounds as 6a, 6b, 14c, and 14d, as indicated by low resistance FCs of 1.9–2.2, which were much better than that of 1b (FC = 10), lower than those of the other new DAANs, and comparable with those of the prior 2c (FC = 1.7) and 2d (FC = 3.7) in the same assay. Notably, 6a, 6b, 14c, and 14d, as well as 2c and 2d, all contain a carbonyl (C═O) group conjugated with the B-ring, regardless of whether the R1 group is an amide or ester. Thus, this carbonyl group might be important for inhibiting the E138K mutation, possibly because it could interact with the mutated K138 or nearby amino acid(s). Support for this postulate was found from the results for 6e, 6f, 6h, 6i, and 6k, in which the carbonyl group was changed to a methylene (−CH2-). Despite their high potency (EC50 = 0.53–3.3 nM) against wild-type NL4-3 virus, these compounds were much less potent against the E138K viral strain (EC50 > 13.3–39 nM), leading to poorer resistance FC values of 9–48 compared with those of 6a, 6b, 14c, and 14d. Thus, the presence of a conjugated carbonyl group in R1 on the B-ring is favorable against the E138K drug 1b resistance. In addition, representative compounds 6b, 6p, and 2d, which had markedly improved drug-resistant profiles for the E138K mutant, were tested against another 1b–resistant viral strain, K101E. Again, improved drug-resistant profiles with low FC values of 3–4 were seen (Table 1). Moreover, eight active compounds (EC50 < 5 nM against IIIB) were further tested in the MT-2 cell line against the multi-NRTI-resistant A17 viral strain with mutants K103N and Y181C, the two major mutants from the first-generation NNRTI drugs. Except 6a and 6p, most of them showed high potency against the drug-resistant A17 viral strain with low nanomolar EC50 values and low FC values ranging from 0.9 to 14 [lower than that of 1b (FC = 18)] compared with wild-type IIIB virus in the same cellular assay, indicating that these compounds are also effective against multidrug resistance to the first-generation NNRTI drugs. Therefore, these results demonstrate that the R1 substituent is the key modification point for overcoming the 1b drug resistances and other multi-NRTI-resistant strains.

Molecular Modeling

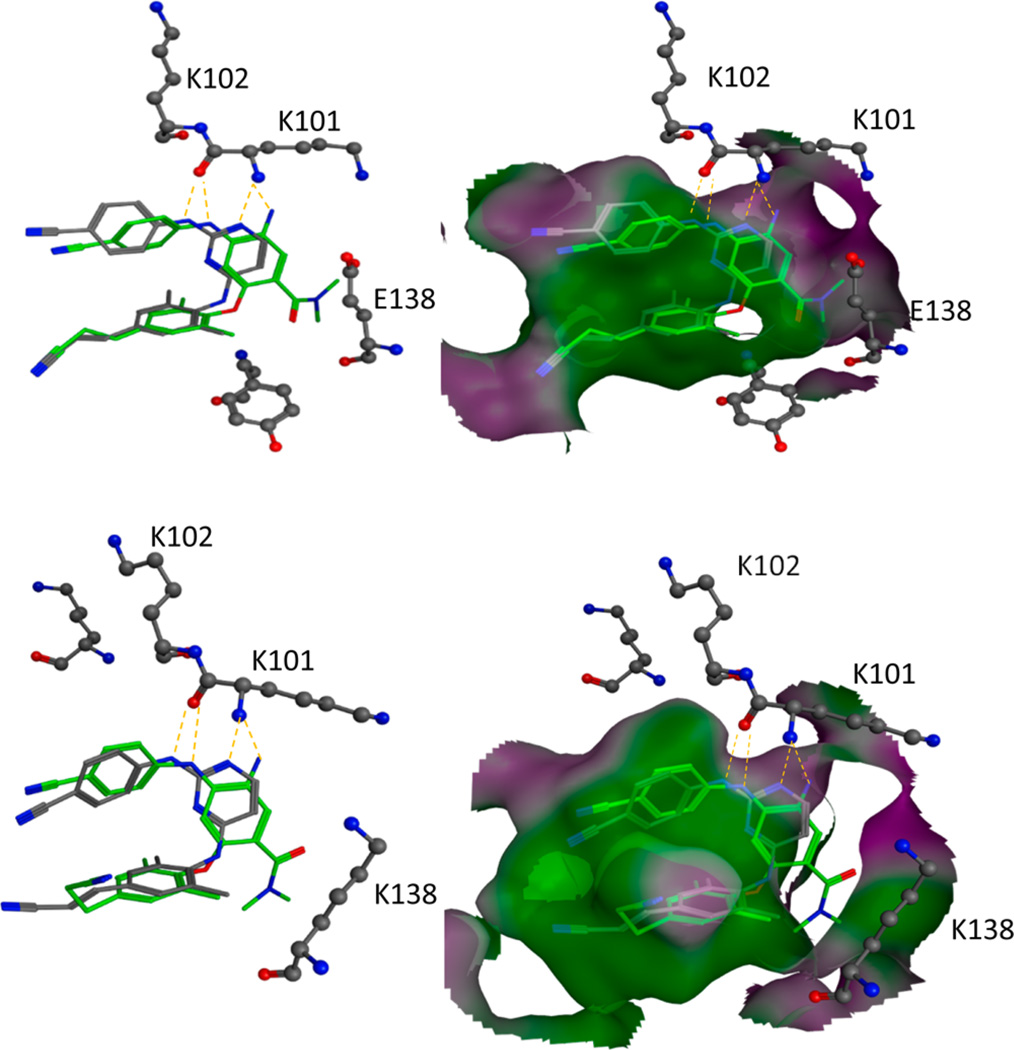

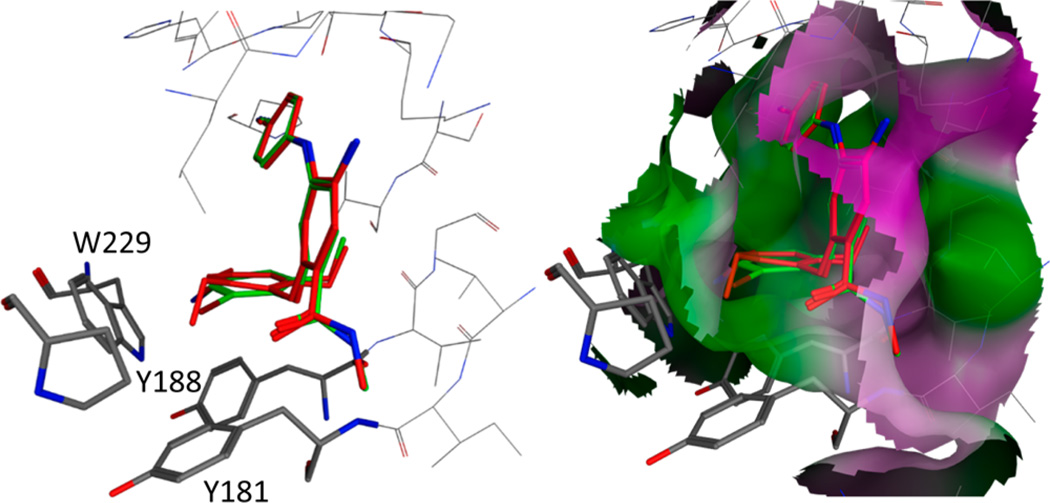

A computational study was performed to demonstrate how the introduction or modification of a R1 substituent could contribute to overcoming E138K-induced drug resistance to 1b. If DAANs bind to both wild-type and mutant viruses such that the R1 group is oriented toward virus residue 138, then modification of its size, shape, and other properties could afford compounds that would interact with the mutant virus better than drug 1b, which could be measured analytically in terms of lowered FC values. Because of their high wild-type potency (single-digit nanomolar levels) with good FC values (2-fold), compounds 6a and 14d were selected as representatives for the computational study. Again, the latter result is highly desirable for combating resistance in the E138K mutant virus. The compounds were docked computationally to both wild-type RT/1b [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 3MEC]21 and mutated E138K RT/nevirapine (PDB entry 2HNY)22 complex crystal structures. For comparison, drug 1b was also docked to both the wild-type and mutant structures. The docking protocol is described in the computational section.

As shown in Figure 3, the docking poses of 6a (green) and 1b (gray) in both 3MEC (wild-type) and 2HNY (E138K mutant) structures, respectively, displayed similar binding orientations with “U”-like conformational shapes and two characteristic hydrogen bonds formed with the key amino acid K101, consistent with prior results and literature reports on 1b. In both cases, the R1 side chain of 6a pointed toward the domain space containing viral residue 138. The greater flexibility of K138 could make the mutant virus more tolerant than the wild-type virus toward various R1 side chain substitutions, as reflected by better FC values. Ten of the 14 docking cases were consistent with this observation. Moreover, as seen in the bottom half of Figure 3, the carbonyl group in the R1 substituent of 6a was oriented toward the amino group in the side chain of K138. Even though a clear interaction between the carbonyl in R1 and the amino group of K138 was not observed in the current models, additional H-bond(s) with a bridging water molecule could be formed to reach high affinity with the mutant target. The second representative compound 14d provided similar results, and its docking figures can be found in the Supporting Information. Therefore, the current modeling results supported our hypothesis that the R1 substituent is associated with the potency of the NNRTIs against viral mutants with resistance to NNRTIs and should, therefore, help in the further optimization of new drug candidates that can overcome the drug resistance to current NNRTI drugs.

Figure 3.

Predicted binding modes of 6a (green sticks) and ligand 1b (gray sticks) with the HIV-1 RT wild-type crystal structure (3MEC) (top) and with the E138K mutant crystal structure (2HNY) (bottom), respectively, and overlapped. Both molecules 1b and 6a form two characteristic hydrogen bonds with K101 in both situations. Surrounding key amino acid side chains are shown in gray ball-and-stick format and labeled. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines, and the distance between ligands and protein is <3 Å.

On the other hand, to understand why a small structural change made a significant reduction in potency, we compared the docked models of both less active 13d (X = MeO/MeO) and the corresponding active 14d (X = MeO/Br) into the wild-type structure (3MEC). As shown in Figure 4, the A-ring and B-ring in both molecules superimposed well, but the C-ring was tilted upward in 13d because of the steric effect of the bulkier methoxy group (outside) on this ring. We suppose that the C-ring in 13d is thus forced away from the Y181 or Y188 residue, reducing the molecular affinity for the viral target and then decreasing the potency. However, the C-ring in 14d superimposed completely with that of active compound 6f [X = Me/Me (data not shown)], as the bromine atom in 14d is similar in size to the methyl (X) in series 6. Furthermore, less active 6g and active 6f were docked in the wild-type RT crystal structure (3MEC) following the same docking protocol. The bulkier group on R1 in 6g pushed more against E138, resulting in a minor shift in 6g’s binding mode compared with that of 6f (Figure in the Supporting Information). This shift may affect the critical interaction between the C-ring and residues W229, Y181, and Y188, thus providing support for our previous supposition for why 6g was less potent than 6f.

Figure 4.

Predicted and overlapped binding modes of 14d (green sticks) and 13d (red sticks) with the HIV-1 RT wild-type crystal structure (3MEC). The key amino acid side chains surrounding the C-ring are shown in gray stick format and labeled. The distance between ligands and protein is <3 Å.

Druglike Properties and Parameters

Active DAANs 6a–c, 6e, 6f, 6h, 6i, 6k, 6n, 14c, and 14d (EC50 < 10 nM) were further assessed for certain physicochemical properties required for potential drug candidates to attain a critical balance between potency and druglike properties. According to methods described previously,13, 23 aqueous solubility at pH 7.4 and 2.0, log P values, and in vitro metabolic stability were measured, and the results are summarized in Table 2. Compounds 6e and 6f with an alkylamine-R1 side chain displayed good molecular solubility at both pH 2.0 (260 and 276 µg/mL, respectively) and pH 7.4 (23.4 and 13.6 µg/mL, respectively), typical physiological environments encountered by a drug in stomach and plasma, respectively. However, the carbamoyl-DAANs 6a, 6b, 6c, and 14d showed reasonable aqueous solubility (25.8–141 µg/mL) only at pH 2.0, regardless of whether X is Me/Me or MeO/Br. These results indicated that the increased molecular alkalescence afforded by the N atom in the R1 substituent of 6e and 6f led to improved molecular aqueous solubility, especially in an acidic medium. In contrast, the compounds with oxygen (O) or halogen atoms in the R1 side chain [see 6h and 6i (R1 = CH2OCOR′), 6k (R1 = CH2OMe), 6n (R1 = Br), and 14c (R1 = COOMe, and X = Br/OMe)] exhibited lower aqueous solubility ranging from 0.12 to 2.63 µg/mL at both pH 2.0 and 7.4. In total, the current results indicated the following rank order of aqueous solubility based on R1 side chain: alkylamine > amide > ester and ether groups. Improved molecular aqueous solubility under acidic conditions should enhance oral drug absorbability in the stomach. Along with aqueous solubility, lipophilicity is another important druglike property related to molecular biological potency, as well as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles and toxicity risk. As shown in Table 2, except for 6n (log P > 5), all of the active compounds tested had desirable log P values within a range of 2.51–3.69 at pH 7.4. Therefore, insertion of hetero atoms into the R1 substituent served as an effective strategy for decreasing lipophilicity, while maintaining high potency, improving aqueous solubility, and decreasing the high risk of unwanted pharmacology.

Table 2.

Physicochemical Parameters of New Active DAAN Compounds

| aqueous solubility (µg/mL)a |

HLMc |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 2.0 | pH 7.4 | log Pa at pH 7.4 | t-PSAb (Å2) | LEd | LLEe | LELPf | maint. % (30 min) | t1/2 (min)h | |

| 6a | 65.1 | 1.08 | 2.86 | 115 | 0.33 | 5.35 | 8.67 | 72.2 | 99 |

| 6b | 69.4 | 1.08 | 3.63 | 124 | 0.34 | 4.70 | 10.7 | 85.2 | 173 |

| 6c | 141 | 1.94 | 2.61 | 124 | 0.34 | 6.09 | 7.68 | 63.2 | 63 |

| 6e | 260 | 23.4 | 2.52 | 98.1 | 0.36 | 6.04 | 7.00 | 93.3 | 231 |

| 6f | 276 | 13.6 | 3.69 | 107 | 0.37 | 5.59 | 9.97 | 78.4 | 99 |

| 6h | 2.63 | 1.86 | 2.84 | 121 | 0.34 | 5.64 | 8.35 | 3.00 | 10.2 |

| 6i | 1.24 | 1.64 | 2.51 | 121 | 0.33 | 6.28 | 7.61 | 4.18 | 11.7 |

| 6k | 1.82 | 0.66 | 3.25 | 104 | 0.38 | 5.59 | 8.55 | 90.8 | 231 |

| 6n | 0.25 | 0.12 | >5 | 94.9 | 0.39 | <3.49 | >12.8 | 58.3 | 50 |

| 14c | 1.73 | 0.20 | 2.85 | 140 | 0.33 | 5.43 | 8.64 | 81.5 | 139 |

| 14d | 25.8 | 3.38 | 3.16 | 133 | 0.33 | 5.09 | 9.57 | 75.7 | 139 |

| 1b | 74.1 | 0.24 | >5 | 97.4 | 0.46 | 5.69h | 7.87h | 80.2 | 116 |

| propranololg | 89.1 | 182 | |||||||

Measured by HPLC in triplicate.

Topological polar surface area predicted by ChemDraw Ultra 12.0.

Human liver microsome assay.

Calculated by the formula −ΔG/HA(non-hydrogen atom), in which normalizing binding energy ΔG = −RT ln Kd, presuming Kd ≈ EC50; negative logarithm values of potency (pEC50) converted from experimental data against wild-type virus IIIB listed in Table 1.

Calculated by the formula pEC50 – log P.

Defined as a ratio of measured log P and LE.

A reference compound with moderate metabolic stability with a t1/2 of 3–5 h in vivo.

Calculated with five time points as 0, 5, 15, 30, and 45 min.

Most recently, concepts such as ligand efficiency (LE),24 ligand lipophilic efficiency (LLE),25 and ligand efficiency-dependent lipophilicity (LELP)26 have been proposed and are being applied increasingly in many medicinal chemistry programs to usefully direct optimization away from highly lipophilic compounds. Defined as the difference between the negative logarithm of the measured potency (pEC50) and log P, the LLE value is a simple but important index combining in vitro potency and lipophilicity, whereas LELP correlates with ADME properties. Accordingly, lipophilic parameters of the active DAANs were calculated by using experimental EC50 and log P values with the formulas cited at the bottom of Table 2. Fortunately, most compounds, including 6a, 6c, 6e, 6f, 6h, 6i, 6k, 14c, and 4d, met acceptable levels for all three ligand lipophilic efficiency indices (LE > 0.3, LLE > 5, LELP < 10),27 while the remaining compounds in Table 2 did not. The compounds with a low LELP value would most likely have the greatest chance of passing all ADME and safety criteria. Additionally, topological polar surface area (t-PSA) parameters of active compounds were calculated with ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 and met the criterion28 of <140 Å2. These property assessment results indicated the postulate that optimization of optimized R1 and X substituents could satisfy the dual goals of maintaining high antiviral potency and improving druglike properties at the same time by adjusting molecular lipophilicity.

Furthermore, the metabolic stability of active compounds was evaluated in a human liver microsome (HLM) assay; 1b and propranolol were also tested for comparison. As shown in Table 2, 6h and 6i were metabolized quite quickly, maintaining only 3.0 and 4.18%, respectively, of the parent compound after incubation for 30 min, with short t1/2 values of 10.2 and 11.7 min, respectively. It is likely that the benzyl ester in the R1 side chain of both compounds is easily metabolized by enzymatic catalysis. In contrast, the remaining tested compounds maintained >50% of the original compound after incubation for 30 min. Among them, compounds 6e and 6k showed greater metabolic stability than propranolol, a common reference compound with moderate metabolic stability. Compounds 6b, 14c, and 14d were less stable than propranolol but more stable than 1b (t1/2 = 116 min). Compounds 6a and 6f (t1/2 = 99 min) had stability similar to that of 1b. Compounds 6c and 6n (R1 = Br) (t1/2 values of 63 and 50 min, respectively) were less stable than 1b. Notably, both bromo compounds 14c and 14d (X = Br/OMe) showed reasonable metabolic stability (t1/2 = 139 min) in the HLM assay, indicating that the halogen Br is acceptable at the X position on the C-ring instead of a methyl group. We further postulate that series 14 might have improved drug absorption leading to better oral bioavailability, because the high electronegativity of the introduced bromo atom (Br) could the balance molecular aqueous solubility and lipophilicity.

CONCLUSIONS

Current structural modification studies of DAANs showed that optimization of the R1 and X substituent on the central phenyl ring (B-ring) and phenoxy ring (C-ring), respectively, could enhance, or maintain, high potency against wild-type and E138K mutant HIV-1 replication and improve molecular aqueous solubility, lipophilicity, and metabolic stability, thus reaching a good balance between high antiviral potency and multiple druglike properties. On this basis, compounds 6a, 14c, and 14d might be potential drug candidates for further development to address new drug resistance deficiencies. Current SAR study further revealed that (1) a carbonyl group in the R1 substituent conjugated with the central phenyl ring (B-ring) is necessary to combat drug resistance from the E138K mutant, (2) hetero atoms (O, N, or Br) in the R1 substituent favor improved druglike ADME properties, (3) bulky R1 groups should be avoided, and (4) Br and OMe could replace the two original methyl groups in DAANs, but two methoxy groups (X) on the C-ring led to reduced potency, because a steric effect altered the favorable conformation of the C-ring. Most interestingly, we found that the introduced R1 side chain provided a possibility for overcoming the new drug resistance from E138K, a major HIV-1 viral mutant with resistance to the NNRTI drug 1b. For instance, compounds 6a, 6b, 14c, and 14d exhibited high potency against the wild type as well as E138K mutant (low nanomolar EC50 values) with low resistance FC values of 1.9–2.2, which are much lower than that of 1b (FC = 10). The modeling study with representative compounds 6a and 14d provided a rationale supporting the role of an optimized R1 group promoting greater efficacy against the E138K mutant, as well as demonstrating possible modification space between subdomains p66 and p51.

The structural design of these compounds was aimed at overcoming the E138K drug-resistant variants, and the current results should help in the development of new NNRTI candidates that can overcome the major drug resistance conferred to the new-generation HIV-1 NNRTI drug 1b, as well as other RT-mutated drug resistances. It is likely that additional structural optimizations may be needed to obtain compounds effective against other less prevalent 1b–resistant variants. Nevertheless, the approach and the results of this study are expected to provide a useful blueprint for further structural optimization against the drug-resistant mutants.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry

Melting points were measured with an RY-1 melting apparatus without correction. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were measured on a JNM-ECA-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. The solvent used was CDCl3 unless otherwise indicated. Mass spectra were recorded on an ABI PerkinElmer Sciex API-150 mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization, and the relative intensity of each ion peak is presented as percent. The purities of target compounds were ≥95%, as measured by HPLC analyses, which were performed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC system with a UV detector and an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), eluting with a mixture of solvents A and B under two conditions (acetonitrile/water or MeOH/water). The microwave reactions were performed on a microwave reactor from Biotage, Inc. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and preparative TLC plates used silica gel GF254 (200–300 mesh) purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co. Medium-pressure column chromatography was performed using a CombiFlash companion purification system. All chemical reagents, NADPH, and solvents were obtained from Beijing Chemical Works or Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. Pooled human liver microsomes (lot no. 20150323H) (protein content of 20 mg/mL, 0.5 mL) were purchased from iPhase Biosciences Ltd. (Beijing, China). HLM assay data analysis was conducted on an LC-MS system with an ABI PerkinElmer Sciex API-3000 mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization.

4-Carboxy-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-2-nitroaniline (4a)

To a solution of N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-methoxycarbonyl-2-nitroaniline (2m) (234 mg, 0.50 mmol) in a THF/MeOH solvent (6:1, v/v) was added a few drops of aq NaOH (1 N), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the pH was adjusted to 2 with aq HCl (2 N). The precipitated solid was collected, washed with water, and dried to afford 204 mg of 4a: 90% yield; yellow solid; mp 260–262 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.06 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 5.95 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.44 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 7.22 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.47 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.58 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.72 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.79 (1H, s, NH), 13.21 (1H, s, COOH); MS m/z (%) 453.3 (M - 1, 45), 409.0 (M - 44, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-hydroxymethyl-2-nitroaniline (4b)

To a solution of 3 (234 mg, 0.50 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added LiBH4 (36 mg, 0.16 mmol) at 0 °C while the mixture was being stirred over 30 min. After MeOH (13 drops) was added dropwise, the mixture was being stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the pH was adjusted to 2–3 with aq HCl (5%). The solid crude product was filtered out and purified by CombiFlash column chromatography (gradient elution, EtOAc/CH2Cl2, 0 to 3%) to produce 200 mg of 4b: 91% yield; yellow solid; mp 232–234 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.15 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 4.89 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.85 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.05 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.70 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 439.3 (M - 1, 100).

4-Chloromethyl-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-2-nitroaniline (4c)

2,4,6-Trichloro [ 1,3,5] triazine (TCT, 627 mg, 3.41 mmol), soluble in DMF (4 mL), was stirred at room temperature for a few minutes, and a white solid appeared. The mixture was stirred for 1 – 2 h and added to a solution of 4b (1 g, 2.27 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) while the mixture was being stirred at room temperature for 4 h by TLC and was monitored until the reaction reached completion. The organic phase was washed with water, a saturated NaHCO3 solution, water, and brine, successively, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (elution, CH2Cl2) to afford 800 mg of 4c: 77% yield; yellow solid; mp 237–239 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.17 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 4.77 (2H, s, CH2Cl), 5.85 (2H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.22 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.77 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 481.3 (M + Na, 100).

General Amidation Procedure for the Preparation of 5a–c

A solution of carboxylic acid compound 4a in SOCl2 (10 mL) was heated to reflux for 4 h and then poured into petroleum ether while the mixture was being stirred. The precipitated solid was collected by filter. The crude aryl chloride was redissolved in THF and an amine reagent (excess) added at 0 °C while the mixture was being stirred over 30 min. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient elution, CH2Cl2/petroleum ether, 70 to 100%) to obtain the amide product.

4-Carboxy-N1 -(4′ -cyanophenyl)-5-(4″ -cyanovinyl-2″,6″ -dimethyl-phenoxy)-2-nitroaniline (4a)

To a solution of N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-methoxycarbonyl-2-nitroaniline (2m) (234 mg, 0.50 mmol) in a THF/MeOH solvent (6:1, v/v) was added a few drops of aq NaOH (1 N), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the pH was adjusted to 2 with aq HCl (2 N). The precipitated solid was collected, washed with water, and dried to afford 204 mg of 4a: 90% yield; yellow solid; mp 260–262 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.06 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 5.95 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.44 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 7.22 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.47 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.58 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.72 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.79 (1H, s, NH), 13.21 (1H, s, COOH); MS m/z (%) 453.3 (M - 1, 45), 409.0 (M - 44, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-hydroxymethyl-2-nitroaniline (4b)

To a solution of 3 (234 mg, 0.50 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added LiBH4 (36 mg, 0.16 mmol) at 0 °C while the mixture was being stirred over 30 min. After MeOH (13 drops) was added dropwise, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the pH was adjusted to 2–3 with aq HCl (5%). The solid crude product was filtered out and purified by CombiFlash column chromatography (gradient elution, EtOAc/CH2Cl2, 0 to 3%) to produce 200 mg of 4b: 91% yield; yellow solid; mp 232–234 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.15 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 4.89 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.85 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.05 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.70 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 439.3 (M - 1, 100).

4-Chloromethyl-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-2-nitroaniline (4c)

2,4,6-Trichloro[ 1,3,5]triazine (TCT, 627 mg, 3.41 mmol), soluble in DMF (4 mL), was stirred at room temperature for a few minutes, and a white solid appeared. The mixture was stirred for 1–2 h and added to a solution of 4b (1 g, 2.27 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) while the mixture was being stirred at room temperature for 4 h, monitored by TLC until the reaction reached completion. The organic phase was washed with water, a saturated NaHCO3 solution, water, and brine, successively, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the cure product was purified by flash column chromatography (elution, CH2Cl2) to afford 800 mg of 4c: 77% yield; yellow solid; mp 237–239 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.17 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 4.77 (2H, s, CH2Cl), 5.85 (2H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.22 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.77 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 481.3 (M + Na, 100).

General Amidation Procedure for Preparation of 5a–c

A solution of carboxylic acid compound 4a in SOCl2 (10 mL) was heated to reflux for 4 h and then poured into petroleum ether while the mixture was being stirred. The precipitated solid was collected by filter. The crude aryl chloride was redissolved in THF and an amine reagent added (excess) at 0 °C while the mixture was being stirred over 30 min. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient elution, CH2Cl2/petroleum ether, 70 to 100%) to obtain the amide product.

N1-(4″ -Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N,N-dimethyl)carbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (5a)

Starting with 4a (300 mg, 0.66 mmol) and aqueous dimethylamine (33%, 5 drops) to afford 249 mg of 5a: 79% yield; mp 122.0–124.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.20 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 3.11 (3H, s, CH3N), 3.20 (3H, s, CH3N), 5.84 (2H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, ═CH), 6.29 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.08 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.20 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.31 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.34 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.75 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 482.4 (M + 1, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N-ethyl)carbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (5b)

Starting with 4a (300 mg, 0.66 mmol), and aqueous ethylamine (65–67%, 3 drops) to afford 130 mg of 5b: 41% yield; yellow solid; mp 208.3–210.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.26 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 2.17 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 3.56 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2), 5.98 (2H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.28 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.27 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 9.28 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.77 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 482.3 (M + 1, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N-cyclopropyl)carbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (5c)

Starting with 4a (250 mg, 0.55 mmol) and cyclopropanamine (114 µL) to afford 170 mg of 5c: 63% yield; yellow solid; mp 234–236 °C; 1H NMR δ 0.60 (2H, m, CH2), 0.91 (2H, m, CH2), 2.16 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.98 (1H, m, NCH), 5.84 (2H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.07 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.25 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 7.59 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, CONH), 9.27 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.77 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 494.3 (M + 1, 80), 437.3 (M - 56, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N,N-dimethylamino)methyl-2-nitroaniline (5e)

A mixture of 4c (200 mg, 0.44 mmol) and aqueous dimethylamine (33%, 5 drops, excess) in THF (5 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield the crude product, which was purified by CombiFlash column chromatography (gradient elution, MeOH/CH2Cl2 0 to 3%) to afford 110 mg of 5e: 54% yield; yellow solid; mp 200–202 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.14 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.36 (6H, s, 2 × NCH3), 3.62 (2H, s, CH2N), 5.85 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.03 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz), 7.45 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.40 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.63 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 423.2 (M - 44, 100), 468.4 (M + 1, 6.2).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N-cyclopropylamino)methyl-2-nitroaniline (5f)

Preparation is the same as that of 5e. Starting with 4c (200 mg, 0.44 mmol) and cyclopropanamine (2 drops, excess) to produce 130 mg of 5f: 62% yield; yellow solid; mp 102–104 °C; 1H NMR δ 0.65 (4H, m, 2 × CH2), 2.18 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.40 (1H, m, CH), 4.22 (2H, s, CH2N), 5.85 (2H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.31 (2H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.52 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.67 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 480.2 (M + 1, 4.8), 423.2 (M - 56, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-(N-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl-2-nitroaniline (5g)

Preparation is the same as that of 5e. Starting with 4c (70 mg, 0.15 mmol) and N-methylpiperazine (2 drops, excess) to afford 58 mg of 5g: 73% yield; yellow solid; mp 194.2–195.3 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.14 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.32 (3H, s, NCH3), 2.62 (8H, m, 4 × CH2), 3.68 (2H, s, CH2N), 5.84 (2H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.03 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.35 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.64 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 423.3 (M - 99, 100), 523.3 (M + 1, 83).

4-Acetoxymethyl-N1 -(4′ -cyanophenyl)-5-(4″ -cyanovinyl-2″ ,6″ -dimethylphenoxy)-2-nitroaniline (5h)

A mixture of 4b (93 mg, 0.21 mmol) and NaOH (30 mg, 0.75 mmol) in acetic anhydride (5 mL) was heated at 100 °C under microwave irradiation while the mixture was being stirred for 5 min. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the precipitated yellow solid was collected and dried to yield 93 mg of 5h: 95% yield; mp 229–231 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.08 (9H, s, 2 × CH3 and CH3C═O), 5.26 (2H, s, CH2O), 6.04 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.43 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, ═CH), 7.15 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.49 (2H, s, ArH-3″, 5″), 7.58 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 7.61 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.33 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.57 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 483.4 (M + 1, 47.4), 505.2 (M + Na, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-[(cyclopropane carbonyl)oxy]methyl 2-nitroaniline (5i)

A mixture of 4b (80 mg, 0.18 mmol) and cyclopropanecarbonyl chloride (28.6 mg 0.27 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) in the presence of pyridine (1 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, washed with aqueous HCl (5%), water, and brine, successively, and dried over MgSO4. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the residue was purified with PTLC [30:70:0.8 (v/v/v) cyclohexane/CH2Cl2/acetone] to afford 74 mg of 5i: 80% yield; yellow solid; mp 190–191 °C; 1H NMR δ 0.94 (2H, m, CH2), 1.06 (2H, m, CH2), 1.70 (1H, m, CH), 2.15 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 5.29 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.85 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, ═CH), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.48 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.40 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.74 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 533.5 (M + 23, 100).

N1 (4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-[(N-methylcarbamyl)oxy]methyl-2-nitroaniline (5j)

A mixture of 4b (150 mg, 0.34 mmol) and methylcarbamic chloride (320 mg, 3.4 mmol) in pyridine (4.5 mL) was heated at 120 °C under microwave irradiation while the mixture was being stirred for 30 min. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the precipitated yellow solid was collected, washed with water, and dried to produce 157 mg of 5j: 93% yield; mp 210–211 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.14 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.86 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, NCH3), 5.29 (2H, s, ArCH2O), 5.84 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.05 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.21 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.32 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.39 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.71 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 514.9 (M + NH3, 100).

N1-(4′-Cyanophenyl)-5-(4″-cyanovinyl-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy)-4-methoxymethyl-2-nitroaniline (5k)

A mixture of BiCl3 (98 mg, 0.31 mmol) and MeOH (15 µL) in CCl4 (2 mL) was first stirred at rt for 20 min, followed by the addition of 4b (110 mg, 0.25 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The solid was filtered out, and the filtrate was condensed under reduced pressure to gain crude product. It was purified by a flash column to produce 80 mg of pure 5k in 71% yield: yellow solid; mp 205–207 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.13 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 3.52 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.62 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.84 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, ═CH), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.20 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.32 (1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, CH═), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3’,5’), 8.39 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.68 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 455.4 (M + 1, 100).

(E)-3-[4-(Benzyloxy)-3,5-dimethylphenyl]acrylonitrile (8a)

A mixture of 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethylbenzaldehyde (7a) (4 g, 26.7 mmol) and 1-(chloromethyl)benzene (4.1 g, 32.0 mmol) in CH3CN (70 mL) in the presence of K2CO3 (7.4 g, 53.6 mmol, excess) was refluxed for 3 h. The solid K2CO3 was filtered out and washed with EtOAc several times. After removal of the organic solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was dissolved in THF (15 mL) and then slowly added to a mixture of (EtO)2P(O)CH2CN (7.1 g, 40 mmol) and t-BuOK (6 g, 53.6 mmol) in THF (10 mL) at 0 °C (ice-water bath) while the mixture was being stirred for 1 h. The mixture was then stirred for an additional 1 h and monitored by TLC until the reaction reached completion. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the solid product was collected, washed with water to neutral, and dried to afford 6.45 g of 8a (92% yield, white solid), which was ready for the next reaction directly without further purification.

(E)-3-[(4-Benzyloxy)-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]acrylonitrile (8b)

The preparation was same as that of 8a. 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzal-dehyde (7b, 2.41 g, 13.2 mmol) was first reacted with 1-(chloromethyl)-benzene (2.02 g, 15.9 mmol) in the presence of K2CO3 (3.64 g, 26.4 mmol), following condensation with (EtO)2P(O)CH2CN (3.6 g, 20.4 mmol) to afford 1.4 g of 8b (36% yield, colorless oil), which was purified on a flash column chromatograph (gradient elution, EtOAc/ petroleum ether, 0 to 10%).

(E)-3-[4-(Benzyloxy)-3-bromo-5-methoxyphenyl]acrylonitrile (8c)

The preparation was the same as that of 8a. Starting with 3-bromo-4-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (7c, 2.0 g, 8.66 mmol), 1-(chloromethyl)benzene (1.3 g, 10.4 mmol), and K2CO3 (2.4 g, 17.3 mmol), followed by condensation with (EtO)2P(O)CH2CN (1.1 g, 8.9 mmol) in the presence of t-BuOK (1.0 g, 8.9 mmol) to afford 1.3 g of 8c, which was purified by a flash column chromatograph (gradient elution, EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0 to 10%): 44% yield; white solid; mp 102.4–103.8 °C; 1H NMR δ 3.90 (3H, s, OMe), 5.08 (2H, s, ArCH2O), 5.79 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, =CN), 6.89 (1H, s, ArH-5), 7.26 (1H, d, J = 16.4 Hz, CH═), 7.27 (1H, s, ArH-2), 7.36 (3H, m, ArH-3′,4′,5′), 7.51 (2H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, ArH-2′,6′); MS m/z (%) 365.9 (M + NH3, 100), 368.1 (80).

4-Cyanoethyl-2,6-dimethylphenol (9a)

The mixture of 8a (6.4 g, 24.3 mmol) in EtOH (50 mL) with H2 gas in the presence of excess Pd-C (10%) under a pressure of 30 psi was shaken for 2 h to yield 9a. After removal of Pd-C and solvent, the residue was purified by a flash column chromatograph (gradient elution, EtOAc/petroleum ether, 10 to 0%) to produce pure 3.89 g of 9a: 90% yield; white solid; mp 135.1 – 136.2 °C; 1H NMR 2.22 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.56 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.82 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 6.83 (2H, s, ArH-2,6); MS m/z (%) 193.2 (M + NH3, 100).

4-Cyanoethyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenol (9b)

The preparation was the same as that of 9a. Starting with 8b (1.4 g, 4.7 mmol) in EtOAc (25 mL) to afford 920 mg of 9b in 94% yield, which was ready for the next reaction without further purification.

2-Bromo-4-cyanoethyl-6-methoxyphenol (9c)

The mixture of 8c (800 mg, 2.33 mmol), Pd-C (5%, 50 mg), and ZnCl2 (300 mg, 2.20 mmol) in EtOAc (25 mL) with H2 gas under a pressure of 40 psi was shaken for 1.5 h to afford 500 mg of 9c: 74% yield; white solid; mp 85.2–87.1 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.60 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, ArCH2), 3.92 (1H, s, OCH3), 5.88 (1H, s, OH), 6.71 (1H, d, J = 1.2 Hz, ArH-6), 6.96 (1H, d, J = 1.2 Hz, ArH-2); MS m/z (%) 273.2 (M + NH3, 100), 275.2 (100).

N1-(4-Cyanophenyl)-4,5-dichloro-2-nitroanilines (10b)

A mixture of 2,4,5-trichloronitrobenzene (200 mg, 0.89 mmol), 4-aminobenzonitrile (126 mg, 1.08 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (580 mg, 1.77 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was heated at 80 °C under microwave irradiation while the mixture was being stirred for 20 min. The mixture was poured into ice-water and adjusted to pH 3; then precipitated solid product was collected by filtration and purified by a silica column with the CombiFlash chromatography system (gradient elution, CH2C2/ petroleum ether, 0 to 70%) to give 31 mg of 10b: 13% yield; orange solid; mp 180–182 °C; 1H NMR δ 7.34 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.50 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.32 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.36 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.42 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 308.1 (M + 1, 100), 310.3 (M + 3, 25).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphe-noxy]-4-methylcarbonyl-2-nitroaniline (11a)

A mixture of 10a (6 g, 18.1 mmol), which was prepared according to the method described in ref 11, and 9a (3.29 g, 19.0 mmol) in 60 mL of DMF in the presence of K2CO3 (4.50 g, 32.6 mmol) was heated at 110 °C while the mixture was being stirred for 4 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and precipitated yellow solid was collected to produce 8.0 g of pure 11a: 94% yield; mp 179–181 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, ArCH2), 3.96 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.97 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.07 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.99 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.85 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 439.2 (M - 31, 100), 471.2 (M + 1, 66).

4-Carboxy-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2-nitroaniline (11b)

The preparation was the same as that of 4a. Starting with 11a (2.5 g, 5.3 mmol) for 8 h to give 2.42 g of pure 11b: 99% yield; yellow solid; mp 220.0–222.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.13 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.62 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 6.26 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.00 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.10 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.70 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 9.17 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.90 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 479.1 (M + Na, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-hydroxymethyl-2-nitroaniline (11c)

The preparation was the same as that of 4b. Starting with 11a (500 mg, 1.06 mmol) with LiBH4 (70 mg, 3.18 mmoL) in THF (15 mL) containing MeOH (13 drops) at 0 °C for 6 h to afford 400 mg of 11c: yellow solid; 85% yield; mp 152–154 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 4.88 (2H, m, CH2O), 6.27 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.99 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.35 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.72 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 465.1 (M + Na, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-isopropylcarbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (11d)

The preparation is the same as that of 5a–c. Starting with carboxylic acid compound 11b (250 mg, 0.55 mmol) and isopropylamine (4 drops, excess) to afford 220 mg of 11d: 81% yield; mp 180.0–181.6 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.27 (6H, d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2 × CH3), 2.13 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.90 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 4.35 (1H, m, CH), 6.28 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.03 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, CONH), 7.53 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 9.27 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.76 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 498.2 (M + 1, 100).

4-Chloromethyl-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2-nitroaniline (11e)

The preparation was the same as that of 4c. Starting with 11c (613 mg, 1.39 mmol) with 2,4,6-trichloro[1,3,5]triazine (306 mg, 1.66 mmol) to afford 500 mg of pure 11e: 86% yield; yellow solid; mp 196–197 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.13 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2Ar), 4.77 (2H, s, CH2Cl), 6.25 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.99 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.07 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.52 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.40 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.78 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 461.3 (M + 1, 100), 463.3 (M + 3, 10).

4-Amino-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2-nitroaniline (11f)

A mixture of 11b (200 mg, 0.44 mmol) and diphenylphosphorylazide (DPPA, 112 µL) in THF (8 mL) in the presence of Et3N (400 µL) was stirred at 25 °C for 3 h. Water (5 mL) was added, and then the reaction mixture was refluxed for an additional 5 h. The solvent was diluted with H2O and extracted with EtOAc several times. The combined organic filtrate was washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After removal of solvent, the residue was purified by flash chromatography (gradient elution, MeOH/petroleum ether, 10 to 60%) to afford 78 mg of 11f: 42% yield; mp 211–212 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.07 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 3.79 (4H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, CH2CH2CN), 5.66 (2H, s, NH2) 6.06 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.82 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.10 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.52 (1H, s, ArH-3), 8.84 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 428.3 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-ethoxymethyl-2-nitroaniline (11m)

Compound 11e (238 mg, 0.52 mmol) in EtOH (25 mL) was heated at 100 °C under microwave irradiation for 20 min. The precipitated solid was collected and dried to produce 203 mg of 11m: 84% yield; yellow solid; mp 136.3–137.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.34 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3), 2.09 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.63 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.90 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, ArCH2), 3.71 (2H, q, J = 6.8 Hz, OCH2), 4.71 (2H, s, ArCH2O), 6.28 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.00 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.51 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.73 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 471.2 (M + 1, 100).

4-Bromo-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2-nitroaniline (11n) and a Byproduct without a 4-Substituent (11o)

A mixture of 11f (27 mg, 0.06 mmol), aq HBr (105 µL, 40%), and aq NaNO3 (55 µL, 27%) in 0.5 mL of THF was stirred at 5 °C for 1 h, and then CuBr (16 mg, 0.11 mmol) and HBr (58 µL, 40%) were added successively while the mixture was being stirred at 5 °C for an additional 3 h. The solid was removed by filtration and washed with EtOAc several times. The organic phase was separated, and the water phase was extracted with EtOAc. The solvent of the combined organic phase was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue crude product was separated by a flash column chromatograph (gradual elution, CH2Cl2/petroleum ether, 0 to 80%) to produce pure 11n (7 mg) and 11o (9 mg) in 23 and 35% yields, respectively. 11n: mp 180.0–182.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.10 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 6.30 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.98 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.99 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.52 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 8.58 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.63 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 513.5 (M + Na, 50), 515.1 (M + 2 + Na, 100). 11o: mp 171.3–173.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.11 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.90 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 6.30 (1H, dd, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH-4), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH-6), 6.98 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.28 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.63 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.20 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3), 9.76 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 413.2 (M + 1, 100).

4-Chloro-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-2-nitroaniline (11p)

A mixture of 10b (166 mg, 0.50 mmol), 9a (90 mg, 0.60 mmol), and K2CO3 (138 mg, 1.0 mmol) in DMF (3 mL) was heated at 110 °C under microwave irradiation while the mixture was being stirred for 20 min. The reaction was monitored by TLC until it reached completion. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the solid product was filtered. The product was purified by CombiFlash column chromatography (gradient elution, CH2Cl2/petroleum ether, 0 to 75%) to give 215 mg of 11p: 55% yield; orange solid; mp 178–180 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 6.32 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.99 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.52 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.41 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.62 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 447.3 (M + 1, 50), 449.3 (M + 3, 24), 469.3 (M + Na, 100).

Catalytic Hydrogenation To Prepare 4-Substituted 1,5-Diarylbenzene-1,2-diamines (6 series)

A 4-substituted 1,5-diaryl-4-nitrobenzene (5 or 11) in EtOH or EtOAc (∼20 mL) in the presence of Pd-C (5–10%, excess) was shaken with H2 under a pressure of 50–55 psi, monitored by TLC for a period of 4–10 h. The solid catalyst was removed by filtration and washed with EtOAc. The solvent of the combined filtrate was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradual elution, MeOH/CH2Cl2, 0 to 5%) to produce corresponding pure 6 series compounds.

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6a)

Starting with 5a (227 mg, 0.47 mmol) to afford 156 mg of 6a: 78% yield; white solid; mp 232.6–233.3 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.10 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.60 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.86 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.10 (3H, s, CH3), 3.16 (3H, s, CH3), 3.60 (2H, s, NH2), 5.77 (1H, s, NH), 6.12 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.60 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.84 (1H, s, ArH-3), 6.92 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.39 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 454.4 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6b)

Starting with 5b (120 mg, 0.25 mmol) to afford 68 mg of 6b: 60% yield; white solid; mp 192.1–193.1 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.24 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 2.13 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.60 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.89 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.55 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, NHCH2), 5.88 (1H, s, NH), 6.21 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.70 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.84 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.00 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.82 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.98 (1H, br, CONH); MS m/z (%) 454.4 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(N-cyclopropylcarbamoyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6c)

Starting with 5c (150 mg, 0.30 mmol) to afford 115 mg of 6c: 82% yield; white solid; mp 221.0–222.7 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.42 (4H, 2 × CH2), 2.08 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.17 (1H, m, CH), 2.60 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.86 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 4.66 (2H, s, NH2), 5.53 (1H, s, NH), 6.02 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.91 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.97 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.39 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 466.4 (M + 1, 88), 409.3 (M - 56, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(isopropylcarbamoyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6d)

Starting with 11d (200 mg, 0.40) in EtOAc (25 mL) for 4 h to afford 150 mg of 6d: 80% yield; mp 216.0–218.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.27 (6H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 × CH3), 2.16 (6H, s, 2 × ArCH3), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.90 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 4.35 (1H, m, CH), 5.85 (1H, s, NH), 6.20 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.66 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.93 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.42 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.80 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.85 (1H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, NH); MS m/z (%) 468.3 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(N,N-dimethylamino)methylbenzene-1,2-diamine (6e)

Starting with 5e (100 mg, 0.21 mmol) to afford 70 mg of 6e: 75% yield; white solid; mp 142.4–143.9 °C; 1H NMR δ 2. 08 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.39 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.67 (2H, s, ArCH2), 5.51 (1H, s, NH), 6.02 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.94 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.01 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.40 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 454.2 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(cyclopropylamino)methylbenzene-1,2-diamine (6f)

Starting with 5f (110 mg, 0.23 mmol) to afford 60 mg of 6f: 58% yield; white solid; mp 106.2–108.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 0.48 (4H, m, 2 × CH2), 2.10 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.23 (1H, m, CH), 2.14 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2CN), 2.88 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArCH2), 3.53 (2H, s, NH2), 3.99 (2H, s, ArCH2), 5.51 (1H, s, NH), 6.02 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.86 (1H, s, ArH-3), 6.94 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.40 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 354.1 (M - 98, 100), 474.0 (M + Na, 10).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methylbenzene-1,2-diamine (6g)

Starting with 5g (110 mg, 0.21 mmol) to afford 30 mg of 6g: 29% yield; white solid; mp 90.9–92.6 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.15 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.33 (3H, s, NCH3), 2.60 (10H, 5 × CH2), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.74 (2H, s, CH2N), 5.52 (1H, s, NH), 6.02 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.55 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.91 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.97 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.40 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 495.6 (M + 1, 4.9), 395 (M - 99, 100).

4-Acetoxymethyl-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6h)

Starting with 5h (80 mg, 0.17 mmol) to afford 30 mg of 6h: 40% yield; white solid; mp 164.1–165.7 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.04 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.09 (3H, s, COCH3), 2.78 (4H, s, 2 × CH2), 4.58 (2H, s, NH2), 5.19 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.90 (1H, s, NH), 6.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.87 (1H, s, ArH-6), 7.04 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.45 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.08 (1H, s, ArH-3); MS m/z (%) 455.3 (M + 1, 17), 395.2 (M - 59, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-[(cyclopropylcarbonyl)oxy]methylbenzene-1,2-diamine (6i)

Starting with 5i (180 mg, 0.35 mmol) to afford 35 mg of 6i: 21% yield; white solid; mp 188.2–189.6 °C; 1H NMR δ 0.90 (2H, m, CH2), 1.06 (2H, m, CH2), 1.70 (1H, m, CH), 2.10 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, ArCH2), 3.48 (2H, s, NH2), 5.31 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.56 (1H, s, NH), 6.06 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.58 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (3H, s, ArH-3,3″,5″), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 481.5 (M + 1, 33), 395.2 (M - 85, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4″-cyanophenyl)-4-(N-methyl carbamate)methyl-2-nitroaniline (6j)

Starting with 5j (150 mg, 0.30 mmol) to afford 67 mg of 6j: 48% yield; white solid; mp 203–204 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.09 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.86 (5H, m, ArCH2 and NCH3), 3.48 (2H, s, NH2), 4.71 (1H, s, CONH), 5.31 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.56 (1H, s, NH), 6.05 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.56 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (3H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.93 (1H, s, ArH-3) 7.40 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 470.1 (M + 1, 22), 395.2 (M - 74, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-methoxymethylbenzene-1,2-diamine (6k)

Starting with 5k (150 mg, 0.33 mmol) to afford 110 mg of 6k: 79% yield; white solid; mp 103.6–104.8 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.09 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.52 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.67 (2H, s, CH2O), 5.56 (1H, s, NH), 6.03 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.55 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.99 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.39 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 427.3 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-(ethoxymethyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6m)

Starting with 11e (180 mg, 0.38 mmol) in EtOAc (20 mL) for 4 h to afford 97 mg of 6m: 58% yield; white solid; mp 135.9–137.2 °C; 1H NMR δ 1.32 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 2.09 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.70 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, OCH2), 4.71 (2H, s, ArCH2O), 5.54 (1H, s, NH), 6.02 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.00 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.39 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 441.4 (M + 1, 100).

4-Bromo-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6n) and 5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6o)

The mixture of 11n and 11o (60 mg), Fe powder (22 mg, 0.39 mmol), and NH4Cl (70 mg, 1.3 mmol) in a mixed solvent of THF, MeOH, and H2O [24 mL, 1:1:1 (v/v/v)] was heated to reflux for 3 h. The solid was filtered out and washed with EtOAc. The filtrate was extracted with EtOAc several times. After removal of organic solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was separated by preparative HPLC using a C18 column chromatograph (gradient elution, methanol/water, 55 to 75%) to produce pure 6n (17 mg) and 6o (18 mg). 6n: white solid; mp 199.5–201.3 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.54 (2H, s, NH2), 5.65 (1H, s, NH), 6.12 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.56 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.93 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.12 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.42 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 461.0 (M + 1, 100), 463.0 (M + 3, 100). 6o: white solid; mp 174.5–176.3 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.63 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.89 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 5.65 (1H, s, NH), 6.53 (1H, dd, J = 8.8 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, ArH-4), 6.56 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, ArH-6), 6.69 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3), 6.93 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 383.3 (M + 1, 41.4), 209.0 (M - 173, 100).

4-Chloro-5-[4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethylphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6p)

Reduction followed the same preparation that was used for 6n. The mixture of 11p (115 mg, 0.26 mmol), iron powder (43 mg, 0.77 mmol), and NH4Cl (139 mg, 2.60 mmol) in a mixed solvent of THF, MeOH, and H2O [24 mL, 1:1:1 (v/v/v)] was heated to reflux for 3 h. After removal of the inorganic solid and organic solvent, the crude product was separated by preparative HPLC using a C18 column chromatograph (gradient elution, methanol/water, 55 to 75%) to afford 70 mg of 6p: white solid; mp 182.1–183.6 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.61 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.87 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.55 (2H, s, NH2), 5.50 (1H, s, NH), 6.14 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.55 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 6.95 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 417.2 (M + 1, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-methoxycarbonyl-2-nitroaniline (13a)

The preparation was the same as that of 11a. Starting with 10a (1 g, 3.00 mmol) and 9b (750 mg, 3.60 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) in the presence of K2CO3 (828 mg, 6.00 mmol) to afford 1.2 g of 13a: 80% yield; yellow solid; mp 172.3–174.0 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.92 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.80 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 3.94 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, OCH3), 6.47 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.51 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.15 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.54 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.98 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.80 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 503.1 (M + 1, 100).

5-[2″-Bromo-4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-6″-methoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cya-nophenyl)-4-methoxycarbonyl-2-nitroaniline (14a)

The preparation was the same as that of 11a. Starting with 10a (455 mg, 1.37 mmol), 9c (264 mg, 1.15 mmol), and K2CO3 (414 mg, 3 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) to afford 340 mg of 14a: 60% yield; yellow solid; mp 174.2–175.2 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.64 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.92 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, ArCH2), 3.80 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.96 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.35 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.89 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH-5″), 7.10 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH-3″), 7.20 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.57 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 9.00 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.81 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 551.0 (M + 1, 34), 553.0 (M + 3, 36), 440.2 (M - 110, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-methylcarbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (13b)

A mixture of 13a (100 mg, 0.20 mmol) and an aqueous CH3NH2 solution (25–30%, 1 mL, excess) in THF (3 mL) was stirred vigorously at 40 °C for 4 h. The mixture was poured into ice-water, and the pH was adjusted to 4 with aq HCl (5%). The precipitated yellow solid was collected and purified by CombiFlash column chromatography (gradient elution, EtOAc/petroleum ether, 60 to 100%) to produce 57 mg of 13b: 57% yield; yellow solid; mp 202–203 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.70 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.98 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.06 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, NCH3), 3.84 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 6.51 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.56 (2H, s, ArH-3″,5″), 7.17 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.56 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CONH), 9.19 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.76 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 502.1 (M + 1, 100).

5-[2″-Bromo-4″-(2-cyanoethyl)-6″-methoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cya-nophenyl)-4-methylcarbamoyl-2-nitroaniline (14b)

The preparation was the same as that of 13b. Starting with 14a (340 mg, 0.62 mmol) and an aqueous CH3NH2 solution (25–30%, excess) to afford 105 mg of 14b: 31% yield; yellow solid; mp 225–227 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.68 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2CN), 2.95 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, ArCH2), 3.06 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, NCH3), 3.83 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.38 (1H, s, ArH-6), 6.88 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH-5″), 7.13 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH-3″), 7.18 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.47 (1H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CONH), 7.56 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 9.21 (1H, s, ArH-3), 9.73 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 550.0 (M + 1, 78), 552.0 (M + 3, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-methoxycarbonylbenzene-1,2-diamine (13c)

The catalytic hydrogenation was the same as the preparation of 6a. Starting with 13a (200 mg, 0.40 mmol) in EtOAc (20 mL) for 4 h to produce 140 mg of 13c: 74% yield; white solid; mp 176.6–178.3 °C; 1H NMR δ 2.60 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CN), 2.90 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, ArCH2), 3.75 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 3.89 (3H, s, OCH3), 5.87 (1H, s, NH), 6.47 (3H, s, ArH-6,3′,5′), 6.73 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.40 (1H, s, ArH-3), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′); MS m/z (%) 473.2 (M + 1, 33.6), 441.3 (M - 31, 100).

5-[4″-(2-Cyanoethyl)-2″,6″-dimethoxyphenoxy]-N1-(4′-cyanophenyl)-4-methylcarbamoylbenzene-1,2-diamine (13d)