Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Laparoscopic surgery has been a frequently performed method for inguinal hernia repair. Studies have demonstrated that the laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach is an appropriate choice for inguinal hernia repair. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) was developed to improve the cosmetic effects of conventional laparoscopy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of SILS-TAPP compared with TAPP technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A total of 148 patients who underwent TAPP or SILS-TAPP in our surgery clinic between December 2012 and January 2015 were enrolled. Data including patient demographics, hernia characteristics, operative time, intraoperative and postoperative complications, length of hospital stay and recurrence rate were retrospectively collected.

RESULTS:

In total, 60 SILS-TAPP and 88 TAPP procedures were performed in the study period. The two groups were similar in terms of gender, type of hernia, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score. The patients in the SILS-TAPP group were younger when compared the TAPP group. Port site hernia (PSH) rate was significantly high in the SILS-TAPP group, and all PSHs were recorded in patients with severe comorbidities. The mean operative time has no significant difference in two groups. All SILS procedures were completed successfully without conversion to conventional laparoscopy or open repair. No intraoperative complication was recorded. There was no recurrence during the mean follow-up period of 15.2 ± 3.8 months.

CONCLUSION:

SILS TAPP for inguinal hernia repair seems to be a feasible, safe method, and is comparable with TAPP technique. However, randomized trials are required to evaluate long-term clinical outcomes.

Key words: Inguinal hernia repair, laparoscopy, single-incision laparoscopic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Inguinal hernia repair is the most frequently performed surgical procedure worldwide.[1] Many different surgical procedures have been described, and tension-free repair using a prosthetic mesh became the mainstay of herniorrhaphy. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair has a number of advantages over conventional open repair. Therefore, laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) techniques are frequently preferred.[2,3,4] When comparing the two techniques, TAPP is easier to learn and may be associated with a shorter learning curve.[5] This is related to the large working space in TAPP repair. Recent studies have been focused to minimise further the invasiveness of laparoscopy by reducing the number of incisions and the port size. In this way, pain and complications associated with incisions were decreased. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) was developed with the aim of reducing the invasiveness of conventional laparoscopy, and has been successfully performed by many surgeons.[6,7,8] The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of a single-incision approach for laparoscopic TAPP repair of the inguinal hernia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients older than 18 years of age who underwent TAPP or SILS-TAPP between December 2012 and January 2015 in the department of surgery of a university research hospital were included in this retrospective study. The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. After the patients were informed about the surgical procedure and potential complications of the surgery, written informed consents were obtained from all the participants. Surgical techniques were selected based on the patient's request only. The data included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), operative time (placement of ports to skin closure), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score, length of hospital stay (defined as operation day to discharge day from the hospital), visual analogue scale (VAS) score 24 h after the surgery, operative complications, and short-term and long-term outcomes that were obtained from hospital charts and office records. Patients with complicating diseases resulting in ASA classification score IV, contraindications to laparoscopic surgery such as previous laparotomy or huge chronic scrotal hernia were also excluded from the study.

All operations were performed by the same surgeon (H.Y.) who had experience in single-port surgery. After standard preoperative preparation, a single intravenous dose of antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin 1 g) was administered before induction, and all the patients underwent surgery under general anaesthesia. A similar surgical technique through a single umbilical port with conventional instruments was followed to perform SILS-TAPP repair.

A standard postoperative analgesic protocol was followed with intravenous petidine hydrochloride 50 mg after operation, intravenous paracetamol 500 mg every 6 h and tenoxicam 20 mg twice a day. Postoperative pain scores were determined on a visual analogue scale 24 h after surgery. Patients were asked to rate their pain in the range of 0 (no pain) to 10 (most pain) that most closely expressed their level of postoperative pain.

Operative techniques

The patient was placed in a supine position on the operating table and the surgeon stood on the opposite side of the hernia. The first 10-mm trocar (Versaport Plus, Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) was introduced through the umbilicus with open technique. Additionally, two 10-mm and 5-mm ports were placed on the right and left sides of the camera port. The 10-mm port was used to introduce the mesh and a 30-mm curved needle for peritoneal suturing. The peritoneal cavity was insufflated with CO2 to a pressure of 12 mmHg, and a 30° laparoscope (Karl Storz™, Germany) was inserted. The patient was placed in a Trendelenburg position with the hernia site rotated up to allow slipping of the bowel. The peritoneum was incised using hook electrocautery from the upper edge of the inguinal floor toward the median umblical ligament, and the preperitoneal plane was developed with sharp and blunt dissections. The hernia sac was carefully separated from the epigastric vessels and vas deferens. A 10 × 15 cm-sized polypropylene mesh (Surgipro mesh, Covidien, MA, USA) was introduced through the 10-mm trocar, placed over the inguinal floor. All potential hernia areas were covered with meshes such as Hesselbach's triangle, inguinal ring, and femoral ring. The mesh was tacked to the transversus abdominis, iliopubic tract, and Cooper ligament using absorbable tackers (AbsorbaTack, Covidien, USA). The peritoneal flap was then closed with running sutures or tackers. The pneumoperitoneum was released, and skin closure was performed with absorbable cutaneous sutures.

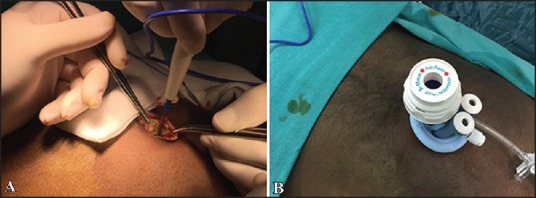

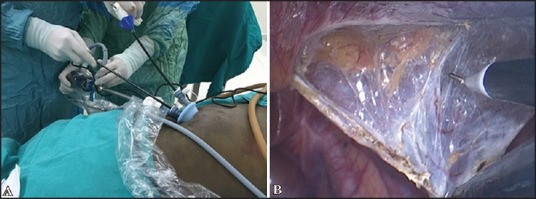

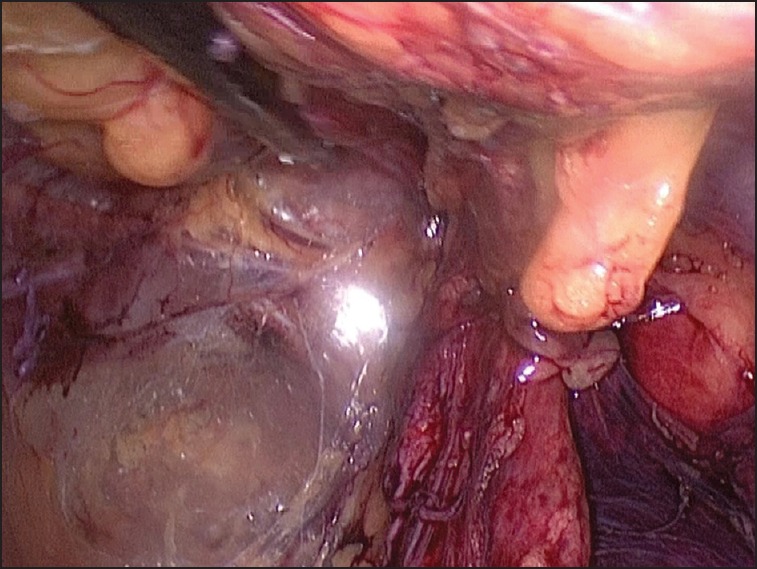

SILS-TAPP was performed with a similar technique to the standard TAPP repair through a single umbilical port. The SILS-Port (Covidien Corp, Mansfield, MA, USA) was introduced through a single 2.0-3.0 cm transverse transumbilical skin and facial incision [Figure 1]. After creation of pneumoperitoneum at pressure of 12 mmHg, two 5-mm working ports and a 10-mm camera port was inserted [Figure 2a]. The peritoneal flap was prepared [Figure 2b and 3]. A mesh was placed, and the peritoneum was closed with standard laparoscopic instruments or tackers. After releasing the pneumoperitoneum, the umbilical fascia was routinely closed with polypropylene loop suture (Surgipro II, Tyco, USA) and the skin was sutured with 4-0 absorbable intradermic sutures (Monocryl, Ethicon, USA).

Figure 1.

A 3-cm skin and facial incision was performed (A) to insert the SILS port (B)

Figure 2.

Two working ports and a camera port were inserted to the abdomen (a), the peritoneum incised from the upper edge of the inguinal floor (b)

Figure 3.

The peritoneum was separated from epigastric vessels and the vas deferens

Statistical analysis

The evaluation of patient data was performed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0 program (SSPS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as the number (%). Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. A P level of <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

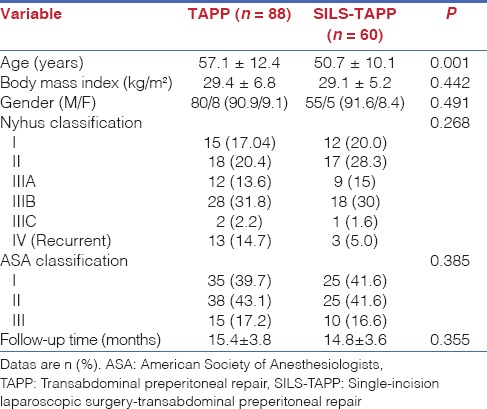

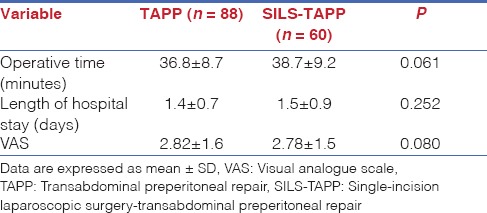

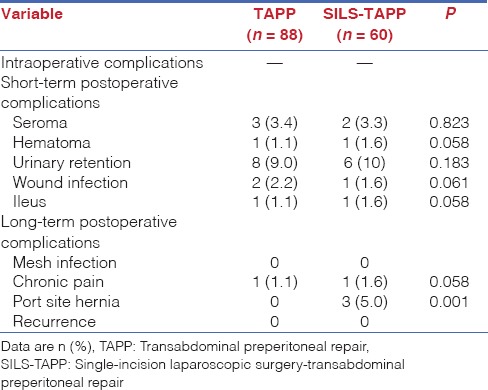

In total, 148 patients underwent laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Of the 148 patients, 88 underwent TAPP repair and 60 underwent SILS-TAPP repair. The mean follow-up period was 15.4 ± 3.8 months for patients who underwent TAPP and 14.8 ± 3.6 months for patients who underwent SILS-TAPP. Table 1 presents the preoperative characteristics of the patients. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age: The mean age of the patients was 57.1 ± 12.4 years in the TAPP group and 50.7 ± 10.1 years in the SILS-TAPP group. The groups were also similar in terms of gender, Nyhus classification, ASA classification, and follow-up time. The operative features of the groups are shown in Table 2. All SILS-TAPP procedures were completed successfully without conversion to TAPP or open repair, and no additional port was required in both groups. There were no differences in operative time, length of hospital stay and VAS scores of patients 24 h after the operation. The mean operative time was 36.8 ± 8.7 min in the TAPP group and 38.7 ± 9.2 min in the SILS-TAPP group. No intraoperative major complications were observed such as vessel, intestine, or bladder injury. The first control examination was performed 2 weeks after the operation to record the short-term complications for all patients. Every 2 months, telephone surveys were conducted to investigate the patients' complaints related to surgery. One patient in each group had a complaint of pain for longer than 3 months. Short-term complication rates were similar in each groups [Table 3]. Several small seroma and hematomas were reported in both groups, and all of them were resolved with conservative treatment. Also, three patients treated with oral antibiotics for port site infection. Long-term complications such as mesh infection and recurrence were not detected in both the groups. Three patients (5.0%) in the SILS-TAPP group experienced port site hernia (PSH). Two of the patients were obese (BMI: 33.7 kg/m2 and 34.1 kg/m2), diabetic, and male. The other PSH had occured in 52-year-old female patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All of the PSHs were confirmed by ultrasound, and elective mesh hernioplasty was performed.

Table 1.

Preoperative patients' characteristics

Table 2.

Comparison of the operative time, length of hospital stay and VAS scores

Table 3.

Comparison of the intraoperative, short-term and long-term postoperative complications

DISCUSSION

SILS is developed in an attempt to minimize the abdominal wall trauma by reducing the number of ports. Several comparative studies have been performed for conventional laparoscopy and SILS.[9,10] The most important advantage of SILS has been reported as the improvement in cosmetic results.[11] Pain scores vary from lower to higher scores when compared to conventional laparoscopy. One of the important results of this study is that the SILS-TAPP is associated with high PSH rate when compared with TAPP. However, in the short-term and long-term complication rates, and pain scores showed no difference with surgical technique.

In this study, we have evaluated conventional three-port TAPP and single-incision TAPP repair with respect to perioperative events and postoperative outcomes. But there was a limitation of this study, namely, the choice of surgical technique to be used was based on patients' demands. The study was also retrospective, and the groups were not randomized. These limitations should be kept in mind while evaluating the study results.

Laparoscopic surgery is considered to be a safe surgery by most of the authors.[12,13,14] However, the bigger umbilical incision to accommodate the SILS port should not be underestimated. Essentially, a larger transumbilical incision carries an increased risk of incisional hernia.[15,16] Several studies have very low incidence of PSH but the current follow-up period of patients who underwent SILS is limited. Agaba et al. reported a PSH rate of 2.9% in a study of 211 patients that included appendectomy, cholecystectomy, Nissen fundoplication, sleeve gastrectomy, gastric banding, colectomy and gastrojejunostomy.[17] Higher incisional hernia rates were also reported in other studies.[18] Authors were recommended to extend the duration of the follow-up period to 2-3 years to determine the “true” risk of incisional hernias.[19] The prospective study of Christoffersen et al. demontrated the incisional hernia rate to be similar with a long-term follow-up period of median 4 years.[20] It is known that the incisional hernia rate is significantly higher in patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In our SILS-TAPP group, all patients who had PSH had one or more comorbidities. Therefore, the bigger umbilical incision is not a single factor for incisional hernia; the patient selection seems to be a cornerstone of decreasing the risk of PSH.

In a majority of the studies, SILS groups have a longer operative time because of the proximity of the instruments with limited triangulation and limited motion of the laparoscope.[21,22] The problem of clashing of instruments was partially offset by using articulating dissector, grasper and shear.[23] However, these instruments may increase the operative costs. The learning curve with conventional instruments is not very long, and after the first 10-20 cases the training process was almost completed.[24,25] The surgeons who are at the learning curve period for SILS should select uncomplicated patients with lower BMI. In fact, obesity is not a contraindication for SILS technique.[26,27] Patients with BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher underwent SILS procedures in our clinic without any major complication. The experience of the surgeon is very important in this situation. Our study surgeon and camera assistant were experienced in SILS with 500+ cases. Therefore, the operative time of the groups were found to be similar in our study.

The analysis of patient demographics demonstrated that patients undergoing SILS-TAPP were significantly younger than patients undergoing TAPP. Among younger people, patients may demand single-incision surgery because of cosmetic results.

CONCLUSION

In the experienced laparoscopic surgery centers, SILS-TAPP inguinal hernia repair is a feasible and safe technique with remarkable cosmesis, and comparable postoperative pain scores although the single umbilical incision may also lead to an incisional hernia risk to patients. With careful patient selection, SILS-TAPP should be applied to patients with cosmetic concerns. Prospective randomized studies with long-term follow-up are necessary to evaluate the true PSH rates, and potential benefits associated with these approaches.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:1045. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takata MC, Duh QY. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:157–78, x. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormack K, Scott N, Go PM, Ross SJ, Grant A. EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001785. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memon MA, Cooper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR. Metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1479–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen MJ. Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2006;8:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishikawa N, Kawaguchi M, Shimizu S, Matsunoki A, Inaki N, Watanabe G. Single-incision laparoscopic hernioplasty with the assistance of the Radius Surgical System. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:730–1. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0633-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menenakos C, Kilian M, Hartmann J. Single-port access in laparoscopic bilateral inguinal hernia repair:First clinical report of a novel technique. Hernia. 2010;14:309–12. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0534-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz H, Alptekin H. Single-incision laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal herniorrhaphy for bilateral inguinal hernias using conventional instruments. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:320–3. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828f6ba8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye G, Qin Y, Xu S, Wu C, Wang S, Pan D, et al. Comparison of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy and fourth-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:7746–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yilmaz H, Arun O, Apiliogullari S, Acar F, Alptekin H, Calisir A, et al. Effect of laparoscopic cholecystectomy techniques on postoperative pain: A prospective randomized study. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:149–53. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.85.4.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang GP, Tung KL. A comparative study of single incision versus conventional laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2015;19:401–5. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu XZ, Fan J, Zhang YQ, Xu MJ, Zhao DB. Single-incision or conventional laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A systematic review. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2005:1–8. doi: 10.3109/13645706.2015.1096288. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelaziz Hassan AM, Elsebae MM, Nasr MM, Nafeh AI. Single institution experience of single incision trans-umbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy using conventional laparoscopic instruments. Int J Surg. 2012;10:514–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang SK, Tay CW, Bicol RA, Lee YY, Madhavan K. A case-control study of single-incision versus standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35:289–93. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0842-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulu B, Yildiz BD, Ilingi ED, Gunerhan Y, Cakmur H, Anuk T, et al. Single port vs. four port cholecystectomy-randomized trial on quality of life. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24:469–73. doi: 10.17219/acem/43713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tranchart H, Ketoff S, Lainas P, Pourcher G, Di Giuro G, Tzanis D, et al. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: For what benefit? HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:433–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agaba EA, Rainville H, Ikedilo O, Vemulapali P. Incidence of port-site incisional hernia after single-incision laparoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2014;18:204–10. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13693422518317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alptekin H, Yilmaz H, Acar F, Kafali ME, Sahin M. Incisional hernia rate may increase after single-port cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:731–7. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flum DR, Horvath K, Koepsell T. Have outcomes of incisional hernia repair improved with time? A population-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2003;237:129–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christoffersen MW, Brandt E, Oehlenschläger J, Rosenberg J, Helgstrand F, Jørgensen LN, et al. No difference in incidence of port-site hernia and chronic pain after single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A nationwide prospective, matched cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3239–45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Hondt M, Pottel H, Devriendt D, Van Rooy F, Vansteenkiste F, Van Ooteghem B, et al. SILS sigmoidectomy versus multiport laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis. JSLS. 2014:18. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khambaty F, Brody F, Vaziri K, Edwards C. Laparoscopic versus single-incision cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35:967–72. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0998-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroh M, Rosenblath S. Single-port, laparoscopic cholecystectomy and inguinal hernia repair:First clinical report of a new device. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:215–7. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon D, Bell RL, Duffy AJ, Roberts KE. Single-port cholecystectomy: Small scar, short learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2954–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu Z, Sun J, Pu Y, Jiang T, Cao J, Wu W. Learning curve of transumbilical single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILS): A preliminary study of 80 selected patients with benign gallbladder diseases. World J Surg. 2011;35:2092–101. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rink AD, Vestweber B, Hahn J, Alfes A, Paul C, Vestweber KH. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for diverticulitis in overweight patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:797–804. doi: 10.1007/s00423-015-1333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakdawala M, Agarwal A, Dhar S, Dhulla N, Remedios C, Bhasker AG. Single-incision sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. A 2-year comparative analysis of 600 patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25:607–14. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]