Abstract

Boerhaave syndrome describes a transmural oesophageal rupture that develops following a spontaneous, sudden intraluminal pressure increase (i.e. vomiting, cough). It has a high rate of mortality and morbidity because of its proximity to the mediastinum and pleura. Perforation localisation and treatment initiation time affect the morbidity and mortality. In this article, we aim to present our successful laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery in a 59-year-old female who was referred to our clinic with a diagnosis of spontaneous lower oesophageal perforation. Laparoscopy and a simultaneous oesophageal stent application may be assumed as an effective alternative to conventional surgical approaches in cases of spontaneous lower oesophageal perforation.

Key words: Boerhaave, laparoscopy, oesophageal perforation, stent

INTRODUCTION

A spontaneous oesophageal rupture is the corruption of the transmural integrity of the oesophagus, following a sudden increase in intraluminal pressure and the lack of relaxation in the cricopharyngeus muscle as a result of severe vomiting, without any underlying oesophageal pathology. Perforation is usually located in the distal oesophagus, and due to its proximity to the mediastinum and pleura, a rapid mediastinitis may develop which may cause a mortality rate of up to between 14% and 40%.[1] The duration of time between perforation and treatment determines the morbidity and mortality.[2] Cases diagnosed in the first 24 h are described as ‘early’, and those diagnosed between 24 and 48 h are described as ‘delayed perforation’.[3] While surgical repair and drainage are adequate in cases with an early diagnosis, discussion about the treatment options in the presence of delayed perforation continues.[4] In our article, we aimed to present simultaneous laparoscopic drainage and a covered self-expandable stent treatment modality that we implemented at an early stage in our case of a spontaneous lower oesophageal perforation.

CASE REPORT

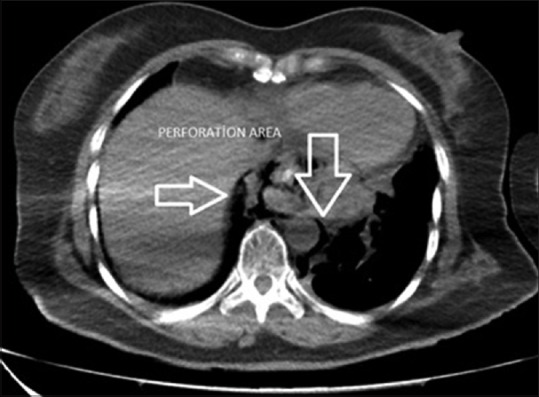

A 59-year-old female was referred to our centre with the pre-diagnosis of spontaneous oesophageal perforation following her admission to an external centre due to postprandial severe vomiting and chest pain complaints. The vital signs of the patient on admission (9 h after perforation) were as follows: Blood pressure, 90/50 mmHg; pulse rate, 120 beats/min; respiratory tachypnoea and oxygen saturation, 90%; leucocyte number, 10.1 10≥/µL and sub-febrile fever of 37.8°C. There was no obvious abdominal finding during the physical examination. No gross pathology was found in the lung X-ray of the patient who was administered aggressive fluid replacement and broad spectrum antibiotics. In the triphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and thorax, free air was determined. It started from the supraclavicular area level and extended towards the para-aortic and peri-hepatic area in the inferior, and it was in the neighbourhood of the oesophagus trace in the mediastinum; a bilateral pleural effusion reaching 3 cm was also observed [Figure 1]. In the upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy, a left-sided transmural rupture of approximately 2–3 cm from the Z-line in the oesophagus distal to the 35–37 cm level was observed; level food wastes in this field were also observed. We planned an operation and a simultaneous self-expandable stent implementation.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography image after perforation

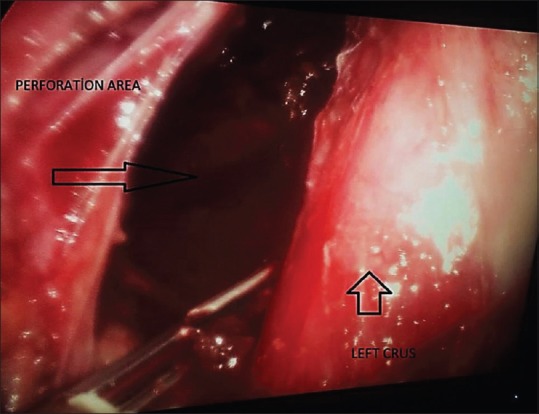

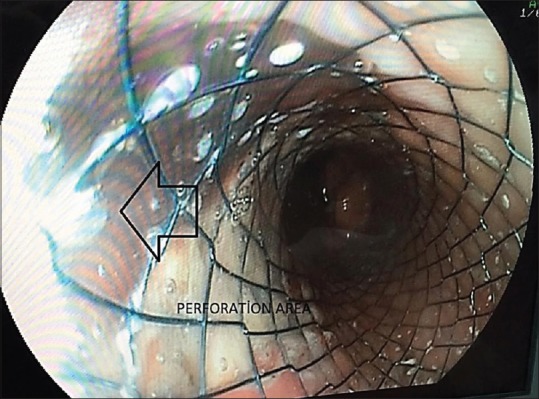

Twenty hours after the perforation, the patient was put in the Lloyd Davis position under general anaesthesia, and a 10-mm camera port was placed in the upper left portion of the hub. Two 10-mm ports were also placed on the right and left of the mid-clavicular line, and a 5-mm port was placed on the right anterior axillary line for the liver retractor. There were no findings in the abdomen during exploration. By putting out the left and right crura, the oesophagus was suspended. The left crus was separated, and we entered the mediastinal area. An inflamed perforation area of approximately 3–4 cm in size with solid food waste was observed in the distal oesophagus, which is in the upper part of the gastro-oesophageal combination on the left side [Figure 2]. Food particles in the operation area were collected in a tissue bag (Endobag™, Covidien), and the contents were washed with 0.9% saline. No additional process was performed on the ruptured area due of tissue friability and oedema. A simultaneous upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed on the patient, and a silicon coated self-expandable stent (Hanaro Stent, MI Tech, Seoul, South Korea) was installed to cover the perforation area [Figure 3]. Following a test with an orogastric tube that looked for leaks using methylene blue, the operation was completed by placing two silicon drains in the ruptured intra-abdominal area.

Figure 2.

Perforation area determined during laparoscopy

Figure 3.

Closure of the perforated area with a coated oesophageal stent

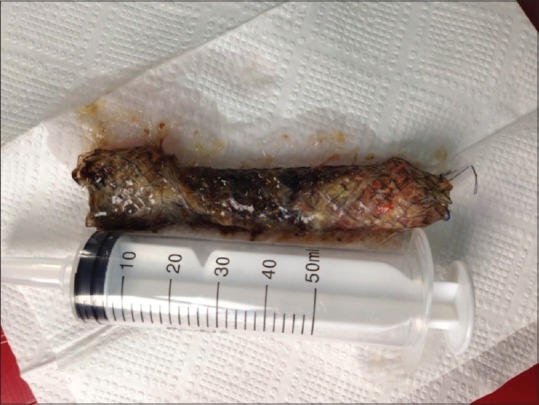

The patient on whom no extravasation was detected by contrast radiography 3 days post-operative was initiated with clear liquid. In the clinical follow-up, bilateral effusion developed in the patient. As a consequence, drainage was made with bilateral pleural catheterisation (Pleurocan, 8-10F, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany). Due to the regression of the effusion, the catheters were withdrawn on the post-operative 7th day. A 50 cc/day sero-purulent content was discharged from the intra-abdominal drain. There was no drainage during the follow-up period or following triphasic contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and thorax on the post-operative 15th day. Consequently, the drains were withdrawn, and the patient was discharged. At the end of the post-operative period of 8 weeks, the stent was removed [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Image of the removed oesophageal stent

DISCUSSION

Treatment of a spontaneous oesophageal transmural rupture that develops after a sudden increase in intraluminal pressure still has challenges. Factors such as perforation area, degree of contamination, time after perforation and presence of comorbidity have prognostic values in these patients whose morbidity and mortality is high.[5] Symptoms may be atypical in terms of the localisation of the oesophagus perforation, or they may imitate other diseases (including myocardial infarction, spontaneous pneumothorax or aortic dissection); furthermore, there may be a delay in diagnosis.[6] It has been shown that misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis rate may be >50%.[7] Dysphagia, sub-cutaneous emphysema, tachycardia and tachypnoea may be frequently detected in the patient. The Mackler triad of severe vomiting history, sub-xiphoid chest pain and sub-cutaneous emphysema may not be observed routinely in every patient.[8] Oesophageal contrast serial radiography, endoscopy and CT may be used in the diagnosis, but tomography is quite effective in the evaluation of the perforation localisation and the surrounding tissues.[6] The diagnosis of our patient was made using CT of the ruptured area, and the food waste inside the patient was observed via an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

The aim of the treatment of oesophageal perforation is the prevention of the development of infection, re-establishment of gastrointestinal integrity and provision of sufficient nutrition to the patient. In the presence of a perforation, attempts to repair it with abdominal or thoracic surgical approaches according to the localisation should be made. Prevention of the possible development of mediastinitis via drainage of the area around the rupture should be considered.

Currently, surgical repair and drainage seem to be the most effective treatment modality.[9,10] Conventional surgical treatments usually involve a thoracotomy or laparotomy. However, it should not be omitted that a thoracotomy may increase the morbidity and mortality in critical and old patients with serious comorbidities. Conservative approaches are suggested for patients without micro-perforations or a significant leakage.[11] As in the other surgical fields, minimally invasive methods (laparoscopy or thoracoscopy) have begun to be used in the treatment of oesophageal perforation.[12] Depending on the perforation area, laparoscopy may be used effectively in the distal oesophagus, and thoracoscopy can be effectively utilised in other localisations. While feeding, the jejunostomy may be opened via laparoscopic gastrostomy, but repair and drainage on a larger field in the oesophagus may be performed via thoracoscopy.[13,14] Tissues such as the intercostal muscles, pleura, omentum and pericardium pedicle flaps may be used to strengthen the repair line in the perforated area, but discussions about their efficacy remain.[15,16] The sternothyroid and sternocleidomastoid muscles may also be used in cervical oesophagus perforation.[17]

It has been suggested that primary suture and sufficient drainage be made in both early and late oesophageal perforation.[9,18] However, only using primary suture in an oedematous and weak area may not achieve satisfactory success, especially in delayed events. Studies have reported that primary oesophagus repair and drainage applied in the first 24 h after the perforation are more successful than in events longer than 24 h.[10] While the mortality rate in events treated within the first 24 h is between 10% and 25%, after 24 h, this rate may increase to 66%.[19,20] In parallel with the development of mediastinitis, the septic table develops rapidly and mortality increases. Although our event had an early perforation, the tissue friability and inflammation inhibited primary repair. In our treatment, there was no need for a thoracotomy because we simultaneously performed laparoscopic drainage and self-expandable stent localisation; moreover, the ruptured area was successfully closed.

Because surgery may increase morbidity and mortality, a treatment alternative has been created by first using metallic and then plastic stents.[21,22] The perforation area is closed rapidly with the covered self-expandable stents localised in an early phase, which results in a decrease in contamination and morbidity. In a study of three patients, a metallic stent was used with the laparoscopic approach, and it was reported that this approach may be preferred in critical patients.[23] Favourable results were achieved with covered stents in benign perforations and anastomotic leakages.[24] For the choice of treatment, patient-specific planning should be made with a multidisciplinary approach. With our laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery approach, the case utilised a minimal invasive stent and surgical drainage and was protected against the need for laparotomy and thoracotomy. Any consequent morbidity that may occur would depend on these two procedures.

As a result, in events with spontaneous perforation localised to the lower oesophagus, intra-abdominal organs may be evaluated by laparoscopy, without a need for thoracotomy. The mediastinum and pleura may be viewed by opening the crus, and food particles in the ruptured area may be cleaned, and sufficient drainage may be provided. Furthermore, extra-luminal leakage may be prevented by the localisation of an intraluminal silicon-coated self-expandable stent in the oesophagus via an endoscopy during the operation. The sufficiency of the process may be assessed with contrast agents accompanied with methylene blue or fluoroscopy given through the oesophagus during laparoscopy. Simultaneous laparoscopy and stent application in events with spontaneous lower oesophageal perforation should be considered as an effective treatment choice alternative to conventional treatment methods.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatia P, Fortin D, Inculet RI, Malthaner RA. Current concepts in the management of esophageal perforations: A twenty-seven-year Canadian experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez FF, Richter A, Freudenberg S, Wendl K, Manegold BC. Treatment of endoscopic esophageal perforation. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:962–6. doi: 10.1007/s004649901147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson JD. Management of esophageal perforations: The value of aggressive surgical treatment. Am J Surg. 2005;190:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulpice L, Dileon S, Rayar M, Badic B, Boudjema K, Bail JP, et al. Conservative surgical management of Boerhaave's syndrome: Experience of two tertiary referral centers. Int J Surg. 2013;11:64–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung HY, Kim JI, Cheung DY, Cho SH, Park SH, Han JY, et al. Successful endoscopic hemoclipping of an esophageal perforation. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:449–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eroglu A, Can Kürkçüogu I, Karaoganogu N, Tekinbas C, Yimaz O, Basog M. Esophageal perforation: The importance of early diagnosis and primary repair. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:91–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pate JW, Walker WA, Cole FH, Jr, Owen EW, Johnson WH. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: A 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47:689–92. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han SY, McElvein RB, Aldrete JS, Tishler JM. Perforation of the esophagus: Correlation of site and cause with plain film findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:537–40. doi: 10.2214/ajr.145.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AZ, Strauss D, Mason RC. Boerhaave's syndrome: Diagnosis and surgical management. Surgeon. 2007;5:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lázár G, Jr, Paszt A, Simonka Z, Bársony A, Abrahám S, Horváth G. A successful strategy for surgical treatment of Boerhaave's syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3613–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiernan PD, Sheridan MJ, Elster E, Rhee J, Collazo L, Byrne WD, et al. Thoracic esophageal perforations. South Med J. 2003;96:158–63. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000054566.43066.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaidya S, Prabhudessai S, Jhawar N, Patankar RV. Boerhaave's syndrome: Thoracolaparoscopic approach. J Minim Access Surg. 2010;6:76–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.68585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toelen C, Hendrickx L, Van Hee R. Laparoscopic treatment of Boerhaave's syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Acta Chir Belg. 2007;107:402–4. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2007.11680082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan AZ, Forshaw MJ, Davies AR, Youngstein T, Mason RC, Botha AJ. Transabdominal approach for management of Boerhaave's syndrome. Am Surg. 2007;73:511–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita S, Takeno S, Moroga T, Kamei M, Ono K, Takahashi Y, et al. Successful treatment of esophageal repair with omentum for the spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Boerhaave's syndrome) Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:745–6. doi: 10.5754/hge10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuhashi N, Nagao N, Tanaka C, Nishina T, Kawai M, Kunieda K, et al. A patient with spontaneous rupture of the esophagus and concomitant gastric cancer whose life was saved: Case of report and review of the literature in Japan. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:161. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erol MM, Ural A, Melek H, Bayram AS, Tekinbas C, Gebitekin C. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: Increased mortality due to delayed presentation. Turk J Med Sci. 2012;42:1437–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill AG, Tiu AT, Martin IG. Boerhaave's syndrome: 10 years experience and review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:1008–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.t01-14-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason GR. Esophageal perforations, anastomotic leaks, and strictures: The role of prostheses. Am J Surg. 2001;181:195–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta NM, Kaman L. Personal management of 57 consecutive patients with esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2004;187:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2002.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eubanks PJ, Hu E, Nguyen D, Procaccino F, Eysselein VE, Klein SR. Case of Boerhaave's syndrome successfully treated with a self-expandable metallic stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:780–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-David K, Lopes J, Hochwald S, Draganov P, Forsmark C, Collins D, et al. Minimally invasive treatment of esophageal perforation using a multidisciplinary treatment algorithm: A case series. Endoscopy. 2011;43:160–2. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landen S, El Nakadi I. Minimally invasive approach to Boerhaave's syndrome: A pilot study of three cases. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1354–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Boeckel PG, Sijbring A, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD. Systematic review: Temporary stent placement for benign rupture or anastomotic leak of the oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]