Abstract

Background

There is no definite consensus on the CV burden associated to Masked hypertension (MH) or White Coat Hypertension (WCH) — conditions that can be detected by out-of-office blood pressure measurements (24 hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring, 24 h ABPM).

Methods

We investigated the association of WCH and MH with arterial aging, indexed by a range of parameters of large artery structure and function in 2962 subjects, taking no antihypertensive medications, who are participating in a large community-based population of both men and women over a broad age range (14–102 years).

Results

The overall prevalence of WCH was 9.5% and was 5.0% for MH, with 54.9% of subjects classified as true normotensive and 30.6% as true hypertensive. Both WCH and MH were associated with a stiffer aorta, a less distensible and thicker common carotid artery, and greater central BP than true normotensive subjects. Notably, the profile of arterial alterations in WCH and MH did not significantly differ from what was observed in true hypertensive subjects. The arterial changes accompanying WCH and MH differed in men and women, with women showing a greater tendency towards concentric remodeling, greater parietal wall stress, and PWV than men.

Conclusion

Both WCH, and MH are associated with early arterial aging, and therefore, neither can be regarded as innocent conditions. Future studies are required to establish whether measurement of arterial aging parameters in subjects with WCH or MH will identify subjects at higher risk of CV events and cognitive impairment, who may require more clinical attention and pharmacological intervention.

Keywords: Arterial stiffness, Pulse wave velocity, Carotid thickness, Arterial aging, Masked hypertension, White coat hypertension, 24 hour blood pressure monitoring

1. Introduction

Arterial aging, characterized by aortic stiffening, thickening, and elongation [1], has been widely recognized as a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2–3] and cognitive impairment [4–8]. Greater stiffness of large arteries is also associated with development of future hypertension and augur metabolic alteration in relatives of diabetic patients [9]. Assessment of Early Vascular Aging (EVA) thus provides an innovative and promising approach to foster effective management of an individual's CVD risk throughout the course of life [10].

Established CVD risk factors are known determinants of arterial aging [11,12]. Blood pressure itself has a large effect [1], though recent results suggest that its role may change or even decrease at older ages [13–14]. Furthermore, the complex relationship between blood pressure and arterial aging is further complicated by two recently recognized blood pressure categories: masked hypertension (MH) and White Coat Hypertension (WCH). Both of these can be detected by out-of-office blood pressure measurements (24 hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring, 24 h ABPM): WCH is characterized by high office BP but normal BP at 24 h ABPM, MH is characterized by normal office BP but high BP at 24 h ABPM.

The burden of WCH and MH has long been debated. Both WCH and MH subjects show a detrimental metabolic profile and a greater prevalence of organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy [15–17]. Recently, arterial alterations of potential prognostic relevance have been reported in WCH subjects [18–19].

However, the long term CV seems to differ between these two conditions. WCH has not been associated with a significant increase in CV events [20–24], whereas prospective studies indicate that the risk for CV events in MH approaches that of subjects with true HT [24–25].

The present study aims to investigate the association of WCH and MH with arterial aging, indexed by a range of parameters of large artery structure and function, with covariates considered for anthropometric, lipid, and personality traits in a large community-based population of both men and women over a broad age range (14–102 years).

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The SardiNIA study was conceived as a study investigating the genetics of complex traits/phenotypes, including CV risk factors and arterial properties, in a Sardinian founder population [26]. It is a prospective population-based cohort study comprised of 6148 subjects (60% response rate) of all residents aged 14 years and older in 4 towns of the Sardinia Region of Italy.

Baseline data were collected between November 2001 and December 2004. The entire cohort was re-examined every 3 years. During the third exam (2007–2010), established CV risk factors and arterial properties were measured, again. The entire population was invited to undertake a 24 h ambulatory blood pressure recording. These data were used for the current analyses.

Traditional CV risk factors were measured as previously described [26].

2.2. Ambulatory BP monitoring

24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (24 h ABPM) was performed with an oscillometric device (Spacelabs 90207, SpaceLabs Inc., Wokingham, Berkshire, UK) with a cuff of the appropriate size. Readings were obtained automatically at 15-minute intervals throughout the day (defined as between 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM), and at 30-minute intervals throughout night (defined as between 10:00 PM and 7:00 AM). Total 24-hour ABPM recording of each subject lasted a minimum of 20 h. The accepted time-interval among recordings of each patient was less than 1 h. Subjects were instructed to engage in normal activities but to refrain from strenuous exercise, and to keep the arm extended and still at the time of cuff inflation. Subjects were instructed to keep the position they were when the measurement started.

In accordance with previous reports from the PAMELA Study [27], White Coat Hypertension (WCH) was diagnosed when subjects had an office BP ≥140 mmHg for SBP systolic or 90 mmHg for DBP with a 24-hour average BP <125 mmHg systolic and <79 mmHg diastolic. Masked Hypertension (MH) was diagnosed when office BP was <140 mmHg for SBP and <90 mmHg for DBP, while the 24-hour average values were ≥125 mmHg for systolic or ≥79 mmHg for diastolic. The remaining subjects were classified as true normotensive (NT) or true hypertensive (HT) based on normality or elevation, respectively, of office and ambulatory BPs.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted adopting the threshold of 24 h ABPM ≥130 mmHg for systolic or ≥80 mmHg for diastolic [28].

2.3. Arterial structure and function

Aortic PWV was measured as previously described [12]. High-resolution B-mode carotid ultrasonography was performed by use of a linear-array 5- to 7.5-MHz transducer (HDI 3500-ATL Ultramark Inc) as previously described [12]. The subject lay in the supine position in a dark, quiet room. The stabilized BP after 15 min from the onset of testing was used for subsequent analyses. The right CCA was examined with the head tilted slightly upward in the midline position. The IMT measurement was obtained from 5 contiguous sites at 1-mm intervals, and the average of the 5 measurements was used for analyses. All the measurements were performed by a single reader (AS). CCA systolic and diastolic diameter (d and D, respectively) were identified via ECG gating and measured similarly to IMT.

CCA wall-to-lumen ratio (%) was calculated as:

CCA cross-sectional area (CSA) was calculated, as:

where ρ is the arterial wall density (ρ=1.06), Re=CCA IMT+CCA D.

CCA stiffness was evaluated by the stiffness index (no unit):

where SBP and DBP are systolic and diastolic BP, Δd is the difference between the systolic and diastolic right common carotid artery diameter, and D is the diastolic diameter.

Measurement of central pressures was determined from radial waveforms using the validated SphygmoCor device (AtCor Medical) [23]. Augmentation index (AIx) was calculated as Augmentation pressure (the difference between the second and first systolic peak of the arterial waveform) expressed as percentage of PP. AIx was normalized at the heart rate of 75 bpm (AIx@75), to overcome the impact of between subjects difference in heart rate.

All measurements were made in duplicate by a single operator.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SAS package for Windows (9.1 Version Cary, NC). Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Differences in mean values for each of the measured variables among groups were compared by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's test for multiple comparisons. ANCOVA analysis was adopted to compare means across Hypertension groups after controlling for age, sex, BMI, current smoking, and diabetes mellitus.

Univariate regression analysis was performed and Pearson's correlation coefficients are presented.

A two-sided p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

For the primary analysis, subjects taking antihypertensive medications were excluded (466 participants or 13.6% of the study population). Among 2962 subjects taking no antihypertensive medications, the overall prevalence of WCH was 9.5% and 5.0% for MH, with 54.9% of subjects classified as true NT and 30.6% as true HT. Subjects with WCH were older and tended to have greater BMI than all other groups of subjects (Table 1). Subjects with MH showed the greatest prevalence of diabetes mellitus (15.6% versus 3.5% in true NT, and 10% in WCH and true HT) and in the use of antidiabetic medications. Notably, WCH had higher 24 h SBP than true NT (and, by definition, lower than MH and true HT) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and metabolic profile of subjects not assuming antihypertensive therapy according to their office and 24 h ABPM BP profile.

| True NT (n = 1721) (group 0) |

WCHT (n = 187) (group 1) |

MH (n = 147) (group 2) |

True HT (n = 907) (group 3) |

ANOVA P value |

Post-hoc Bonferroni (p < 0.05) |

ANCOVA P valuea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.9 ± 14.0 | 58.8 ± 12.5 | 55.3 ± 17.9 | 53.5 ± 14.1 | .0001 | 0 < all | |

| Women (%) | 70.0 | 54.0 | 45.6 | 45.0 | 0 > all | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 3.5 | 10.2 | 15.6 | 10.0 | 0 < all | ||

| Current smoking (%) | 19.5 | 8.6 | 19.0 | 19.0 | .01 | 1 < all | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 4.1 | 29.1 ± 4.6 | 26.8 ± 4.6 | 26.9 ± 4.3 | .0001 | 1 > 2,3 > 0 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 82.9 ± 11.1 | 94.0 ± 11.8 | 89.6 ± 11.1 | 90.3 ± 12.0 | .0001 | 1 > 2,3 > 0 | 0.48 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 93.2 ± 18.4 | 101.6 ± 21.8 | 105.0 ± 29.7 | 102.4 ± 26.2 | .0001 | 0 < all | .05 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 214.3 ± 38.9 | 230.2 ± 37.5 | 215.4 ± 43.9 | 224.3 ± 39.4 | .0001 | 1,3 > 0 | .001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 135.5 ± 33.8 | 148.6 ± 30.5 | 136.2 ± 37.2 | 144.0 ± 33.9 | .0001 | 1,3 > 0 | .05 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 58.8 ± 14.4 | 56.9 ± 14.4 | 56.1 ± 16.5 | 55.5 ± 13.3 | .0001 | 3 < 0 | 0.37 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 100.9 ± 56.1 | 122.6 ± 62.6 | 116.6 ± 67.2 | 126.5 ± 85.6 | .0001 | 0 < all | .001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/ml) | 0.84 ± 0.16 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 0.89 ± 0.18 | .0001 | 1,3 > 0 | 0.17 |

| Uric acid (mg/ml) | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 4.8 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | .0001 | 0 < all | 0.22 |

BMI= Body Mass Index.

LDL= Low Density Lipoprotein.

HDL= High Density Lipoprotein.

After controlling for age, sex, BMI, smoking, and diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Office, central, and ABPM blood pressures and medication use in subjects not assuming antihypertensive therapy according to their office and 24 h ABPM BP profile.

| True NT (n = 1721) (group 0) |

WCHT (n = 187) (group 1) |

MH (n = 147) (group 2) |

True HT (n = 907) (group 3) |

ANOVA P value |

Post-hoc Bonferroni (p < 0.05) |

ANCOVA P valuea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office SBP (mmHg) | 115.5 ± 10.9 | 145.0 ± 10.9 | 126.6 ± 9.1 | 136.5 ± 17.9 | .0001 | 1 > 3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| Office DBP (mmHg) | 72.7 ± 7.2 | 88.1 ± 7.2 | 75.2 ± 6.3 | 84.0 ± 9.8 | .0001 | 1 > 3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| Office MBP (mmHg) | 86.8 ± 7.6 | 106.9 ± 5.8 | 92.1 ± 6.1 | 101.3 ± 11.3 | .0001 | 1 > 3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| Office PP (mmHg) | 42.8 ± 8.2 | 56.9 ± 13.5 | 51.5 ± 8.6 | 52.5 ± 13.9 | .0001 | 1 > 2,3 > 0 | .0001 |

| HR (bpm) | 68.6 ± 10.8 | 68.7 ± 11.1 | 66.7 ± 9.9 | 69.7 ± 11.3 | .01 | 3 > all | .0001 |

| 24 h SBP (mmHg) | 112.5 ± 6.4 | 117.2 ± 5.1 | 129.3 ± 3.9 | 130.8 ± 9.6 | .0001 | 2,3 > 1 > 0 | .0001 |

| 24 h DBP (mmHg) | 70.5 ± 4.9 | 72.1 ± 4.8 | 74.5 ± 4.2 | 82.9 ± 6.4 | .0001 | 2,3 > 1 > 0 | .0001 |

| Central SBP (mmHg) | 102.7 ± 11.8 | 131.2 ± 11.9 | 113.3 ± 11.3 | 124.3 ± 18.3 | .0001 | 1 > 3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| Central ESP (mmHg) | 94.0 ± 10.9 | 119.1 ± 9.8 | 102.6 ± 10.8 | 113.6 ± 15.7 | .0001 | 1 > 3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs (%) | 1.9 | 3.7 | 8.2 | 3.5 | .0001 | 2 > all | 0.19 |

| Antiplatelet (%) | 2.5 | 9.1 | 8.2 | 4.6 | .0001 | 0.13 | |

| Statin (%) | 2.3 | 6.4 | 8.9 | 5.1 | .0001 | 2 > all | 0.44 |

| Nitrates (%) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.29 | 0.11 |

SBP = Systolic Blood Pressure.

DBP = Diastolic Blood Pressure.

MBP = Mean Blood Pressure.

PP= Pulse Pressure.

HR = Heart Rate.

ESP = End-Systolic Pressure.

After controlling for age, sex, BMI, smoking, and diabetes mellitus.

Both WCH and MH (Table 3) were associated with stiffer aorta, less distensible and thicker CCA, and greater central BP than true NT. Additionally, both WCH and MH presented arterial alterations similar to that observed in true HT.

Table 3.

Arterial properties in subjects not assuming antihypertensive therapy according to their office and 24 h ABPM BP profile.

| True NT (n = 1721) (group 0) |

WCHT (n = 187) (group 1) |

MH (n = 147) (group 2) |

True HT (n = 907) (group 3) |

ANOVA P value |

Post-hoc Bonferroni (p < 0.05) |

ANCOVA P valuea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWV (m/s) | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 3.2 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | .0001 | 0 < all | .0001 |

| PWV/MBP | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 8.3 ± 2.7 | 7.8 ± 2.3 | .02 | 2,3 > 0,1 | .0001 |

| AI@75 (%) | 18.6 ± 14.2 | 28.4 ± 12.1 | 20.7 ± 16.4 | 25.4 ± 12.1 | .0001 | 1,3 > 2 > 0 | .0001 |

| CCA IMT (mm) | 0.53 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.14 | 0.62 ± 0.16 | 0.60 ± 0.14 | .0001 | 0 < all | .0001 |

| CCA diameter (mm) | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | .0001 | 0 < all | .0001 |

| CCA W/L ratio | 20.6 ± 3.7 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 22.6 ± 5.3 | 21.4 ± 4.5 | .01 | 0 < all | 0.22 |

| CCA CSA | 19.4 ± 5.3 | 23.9 ± 6.7 | 25.7 ± 10.0 | 24.5 ± 8.3 | .0001 | 0 < all | .0001 |

| CCA circumferential stress | 17.8 ± 3.8 | 22.9 ± 6.0 | 20.6 ± 5.2 | 21.7 ± 5.5 | .0001 | 1 > 2,3 > 0 | .0001 |

| CCA strain (%) | 8.8 ± 3.1 | 8.2 ± 3.5 | 8.6 ± 3.1 | 7.8 ± 3.2 | .0001 | 3 < 0 | .05 |

| CCA stiffness | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 7.5 ± 4.5 | 6.8 ± 3.3 | 7.6 ± 4.7 | .0001 | 1,3 > 0 | 0.09 |

PWV = Pulse Wave Velocity.

PWV/MBP = Pulse Wave Velocity/Mean Blood Pressure.

AI@75 = Augmentation Index normalized for heart rate if 75 bpm.

CCA = Common Carotid Artery.

IMT = Intima-; Media Thickness.

W/L= Wall-to-lumen ratio.

CSA = Cross Sectional Area.

After controlling for age, sex, BMI, smoking, and diabetes mellitus.

More specifically, PWV, CCA IMT, and arterial distensibility, evaluated as strain and as stiffness index, did not differ between subject with either WCH or MH and subjects with true HT. Conversely, AIx@75 was greater in WCH and smaller in MH than in true HT.

Sensitivity analyses, conducted adopting the threshold of 24 h ABPM ≥130 mmHg for systolic or ≥80 mmHg for diastolic recommended by current Guidelines [27], yielded similar results (Supplemental Tables 1–4).

Secondary analyses were carried out after inclusion of subjects consuming antihypertensive medications. As illustrated in Supplemental Tables 4A–4B, results are similar to those found in the untreated group.

3.1. Gender differences in the impact of WCH and MH on arterial structure and function

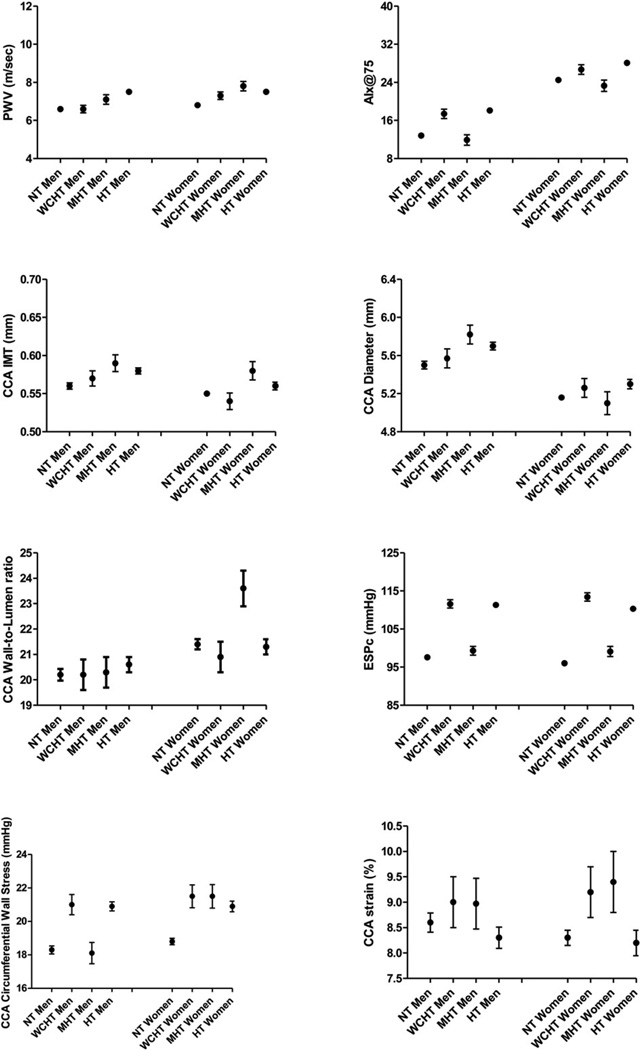

ANCOVA analysis revealed that several arterial parameters (PWV, CCA IMT, CCA circumferential stress, etc.) differed between men and women (Sex effect column in Table 4). Additionally, the impact of WCH and MH on arteries was gender-specific (significant interaction term Sex*Hypertension category column in Table 4). Therefore, Fig. 1 illustrates least square mean values form easures of arterial structure and function in different Hypertension groups after adjustment for diabetes mellitus, smoking status, and BMI, respectively in men and women.

Table 4.

Arterial properties of subjects not assuming antihypertensive medications according to their office and 24 h ABPM BP profile in men and women.

| Men | Women | ANCOVA analysis (p <) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True NT (n = 518) |

WCHT (n = 86) |

MH (n = 80) |

True HT (n = 499) |

True NT (n = 1203) |

WCHT (n = 101) |

MH (n = 67) |

True HT (n = 408) |

Sex-effect | BP category effect |

Interaction term |

|

| PWV (m/s) | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 2.9 | 8.0 ± 2.9 | 6.3 ± 1.6 | 8.3 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 3.3 | 7.8 ± 2.5 | .0001 | .0001 | .001 |

| PWV/MBP | 7.2 ± 1.8 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 2.1 | 7.7 ± 2.5 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 7.8 ± 2.0 | 9.1 ± 3.0 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | .0001 | .0001 | 0.01 |

| AI@75 (%) | 10.6 ± 13.1 | 22.0 ± 12.5 | 13.8 ± 16.1 | 21.1 ± 11.7 | 22.0 ± 13.2 | 34.0 ± 8.4 | 29.7 ± 11.9 | 30.5 ± 10.7 | .0001 | .0001 | .01 |

| Office PP (mmHg) | 43.3 ± 8.4 | 58.0 ± 14.0 | 51.6 ± 8.9 | 54.4 ± 15.0 | 42.5 ± 8.4 | 58.8 ± 13.5 | 51.5 ± 9.0 | 54.1 ± 15.5 | 0.59 | .0001 | 0.05 |

| CCA IMT (mm) | 0.54 ± 0.13 | 0.62 ± 0.16 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.64 ± 0.16 | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 0.60 | .001 | 0.05 |

| CCA diameter (mm) | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | .0001 | .0001 | 0.24 |

| CCA W/L ratio | 19.9 ± 4.0 | 20.7 ± 6.0 | 20.8 ± 4.9 | 21.1 ± 4.7 | 20.9 ± 3.5 | 22.0 ± 4.4 | 25.0 ± 5.0 | 21.8 ± 4.4 | .01 | .0001 | .01 |

| CCA CSA | 20.9 ± 6.5 | 24.0 ± 6.4 | 26.1 ± 10.2 | 25.9 ± 8.7 | 18.6 ± 4.4 | 23.9 ± 7.1 | 25.1 ± 9.9 | 22.5 ± 7.3 | .01 | .0001 | 0.16 |

| CCA circumferential stress |

17.8 ± 4.1 | 22.4 ± 6.9 | 18.9 ± 4.7 | 21.9 ± 5.5 | 17.8 ± 3.7 | 23.5 ± 4.8 | 22.9 ± 4.9 | 21.5 ± 5.5 | .01 | .0001 | .01 |

| CCA strain (%) | 8.8 ± 3.2 | 8.2 ± 3.8 | 8.5 ± 3.2 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | 8.7 ± 3.1 | 8.3 ± 3.1 | 8.8 ± 3.1 | 8.0 ± 3.3 | 0.64 | .001 | 0.87 |

| CCA stiffness | 6.2 ± 3.0 | 7.9 ± 5.7 | 6.9 ± 3.1 | 7.8 ± 4.8 | 6.2 ± 3.7 | 7.0 ± 2.9 | 6.8 ± 3.7 | 7.3 ± 4.6 | 0.37 | .0001 | 0.72 |

PWV = Pulse Wave Velocity.

PWV/MBP = Pulse Wave Velocity/Mean Blood Pressure.

AI@75 = Augmentation Index normalized for heart rate if 75 bpm.

CCA = Common Carotid Artery.

IMT = Intima-; Media Thickness.

W/L= Wall-to-lumen ratio.

CSA = Cross Sectional Area.

Fig. 1.

Least square means (± SEM) form easures of arterial structure and function according to different 24 h ABPM groups in men and women, after adjustment for, diabetes mellitus, and BMI.

In men, as compared to true NT, WCH was characterized by a greater parietal arterial stress (p < 0.01) in the absence of changes in arterial geometry (CCA wall-to-lumen ratio). An increased reflected wave, as estimated by AIx@75 (p < 0.01), and a not-significant more distensible artery (CCA Strain) was accompanied by similar PWV and CCA IMT. In men, MH was characterized by circumferential wall stress that did not differ from true NT (but was significantly lower than in WCH or in true HT, p < 0.001). The net effect on arterial wall stress may be the result of the opposing effects of greater CCA IMT – which would increase vessel wall stress – and a compensatory dilation (greater diameter) in a still distensible artery (similar CCA strain as compared to true NT) – which would decrease vessel wall stress. No hypertrophic remodeling was observable (wall-to-lumen ratio super-imposable to that observed in true NT subjects), though arteries tended to be stiffer (marginally significant greater PWV).

In women, as compared to true NT, WCH was characterized by a greater parietal arterial stress (p < 0.001) in the absence of changes in arterial geometry (CCA wall-to-lumen ratio). An increased reflected wave (p < 0.001), as estimated by AIx@75, resulted in a significantly stiffer artery (greater PWV, p < 0.05). As compared to true NT, MH was characterized by higher circumferential wall stress (comparable to values observed in WCH and true HT) reflecting a significant tendency towards concentric remodeling (greater CCA wall-to-lumen ratio) (p < 0.001). The maintained distensibility of the arterial wall (CCA strain marginally greater than in true NT) was not sufficient to protect the artery from thickening (greater CCA IMT, p < 0.001) and stiffening (greater PWV, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The diffusion of 24 hour blood pressure monitoring has led to the identification of two novel categories, WCH and MH, characterized by a great discordance between office BP and BP profile over 24 h [27].

A previous study investigated the relevance of WCH and MH as risk factors for the development of true HT) and identified aging and metabolic alterations as predictors of the greater risk of true HT attributable to WCH and MH [27]. The progression to true HT, observed in subjects with WCH or MH was faster than previously reported [26], which may be a consequence of the arterial alterations observed — primarily in arterial stiffening [9,29].

We propose to evaluate their potential association with central arterial structure and function, known risk factors for CVD [2–4] and cognitive impairment [5–7]. A recent population study in Taiwan reported that WCH was associated with arterial aging [19]. Specifically, carotid IMT, aorta PWV, and augmentation index were greater in WCH than in true NT, and all these arterial measurements were similar to levels observed in true HT [19]. Our study confirmed that WCH is associated greater arterial stiffness, thickness, and parietal stress than in true NT. Novel observations are represented by the finding that MH also was accompanied by alterations in arterial properties that were mostly similar to those in WCH, except for wave reflection in which MH was not associated with increased augmentation index. In general, the association of WCH and MH with arterial parameters was similar to what was observed in true HT.

The cross-sectional and observational design of the present population study does not allow insight into the mechanisms leading to WCH or MH, but suggest some possible factors. We previously noted one contributing factor, the relevance of personality in WCH and MH [30]. Specifically, anxious individuals were more likely to have WCH, and those who were less conscientious had an increased risk of masked uncontrolled hypertension [30].

On a merely speculative basis, we may hypothesize that WCH and MH may represent different “stages” in the vicious cycle between elevated blood pressure and arterial stiffness. These “stages” reflect the active remodeling to which arteries continuously undergo in response to (hemodynamic) stimuli inducing further hemodynamic alterations.

True NT subjects are characterized by low arterial wall stress and low distending pressure with great arterial distensibility and lower reflected wave and arterial stiffness. In WCH, the higher arterial wall stress associated with higher pressure and arterial thickness is associated with higher arterial distensibility, likely because the arterial wall composition (extracellular matrix) is still characterized by components with higher intrinsic distensibility.

Whatever the biochemical basis, the physiological consequences are that subjects with MH are able to maintain a considerable arterial strain in the presence of higher arterial wall stress at the cost of concentric remodeling (greater wall-to-lumen ratio) of large arteries. When the arterial wall is exposed to these factors for longer time and the arteries thus encounter substantial structural change, the higher parietal stress is accompanied by lower arterial strain with thicker and larger arteries.

Gender affects such a process. For instance, in women with MH the greater arterial stress parallels the increase in central pressure (as compared to true NT) with less arterial thickening. In men with MH, the arterial thickening triggered by higher wall stress is partly compensated for by arterial dilation (and maintenance of a sort of “eutrophic remodeling”).

Notably, subjects with MH – in the whole population as well as in men and women – showed higher prevalence of diabetes and use of antidiabetic drugs (that should make artery stiffer and thicker) and a greater use of statin and nitrates (that should improve arterial properties). Nonetheless, subjects with MH had a stiffer aorta (PWV/MBP), while carotid artery was thicker (greater CSA) but more distensible (greater strain and lower stiffness).

Clearly these notions are speculative. However, given that none of the arterial changes occurring with WCH, MH, or true HT are benign and all have been associated with greater risk of CV events and cognitive impairment [2–7], routine assessment of arterial properties should be encouraged to better manage subjects potentially at higher CV risk. Whether a single arterial measurement (such as arterial stiffness, indexed as PWV) or a set of these parameters should be adopted is beyond the goals of the present study.

The central BP values observed in different 24 h ABPM profiles merit comment. A large difference between central and peripheral systolic and pulse pressure exists: it decreases with age, but remains substantial even in octogenarians [31]. Central aortic pressure is thought to more accurately reflect the cardiac afterload and, thus, may better correlate with target organ damage and with the risk for CV events. Indeed, studies employing a generalized transfer function as a means to estimate central pressure have shown that central pressure is more strongly related to target organ damage and cardiovascular events than is brachial blood pressure [32]. We observed that central systolic and end-systolic BP values in subjects with WCH were greater, not only than in true NT, but also than in true HT. Thus, we should start considering that, regardless of the accuracy of the generalized transfer function adopted to calculate central BP, the latter largely reflects brachial BP values.

5. Perspectives

The present study showed that neither WCH nor MH can be regarded as innocent conditions. In fact, both conditions are associated with early arterial aging [1,10,25] and thus with considerably higher CVD risk. Thus, measurement of arterial aging parameters in subjects with WCH or MH may be helpful to identify and follow-up subjects at higher risk of CV events and cognitive impairment that may require more clinical attention and pharmacological intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of funding

The SardiNIA team was supported by Contract NO1-AG-1-2109 from the NIA. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, U.S. National Institute on Aging.

We thank Monsignore Piseddu, Bishop of Ogliastra, the Mayors of Lanusei, Ilbono, Arzana, and Elini, the head of the local Public Health Unit ASL4, and the residents of the towns, for their volunteerism and cooperation. In addition we are also grateful to the Mayor and the administration in Lanusei for providing and furnishing the clinic site.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No author has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.172.

References

- 1.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor? Hypertension. 2005;46:454–462. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000177474.06749.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. NEJM. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: an individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scuteri A, Nilsson PM, Tzourio C, Redon J, Laurent S. Microvascular brain damage with aging and hypertension: pathophysiological consideration and clinical implications. J. Hypertens. 2011;29:1469–1477. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328347cc17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scuteri A, Wang H. Pulse wave velocity as a marker of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl. 4):S401–S410. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scuteri A, Tesauro M, Guglini L, et al. Aortic stiffness and hypotension episodes are associated with impaired cognitive function in older subjects with subjective complaints of memory loss. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;169:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scuteri A, Di Daniele N. Are hemodynamic factors involved in cognitive impairment? Hypertension. 2016;67:34–35. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Shetty V, et al. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilsson PM, Boutouyrie P, Cunha P, et al. Early vascular ageing in translation: from laboratory investigations to clinical applications in cardiovascular prevention. J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1517–1526. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328361e4bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scuteri A, Cunha PG, Agabiti Rosei E, et al. for the MARE consortium. Arterial stiffness and influences of the metabolic syndrome: a cross-countries study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru' M, et al. The central arterial burden of the metabolic syndrome is similar in men and women: the SardiNIA study. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:602–613. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alghatrif M, Strait JB, Morrell CH, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of arterial stiffness and the role of blood pressure: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Hypertension. 2013;62:934–941. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Orru' M, et al. A longitudinal perspective on the conundrum of central arterial stiffness, blood pressure and aging. Hypertension. 2014;64:1219–1227. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancia G, Bombelli M, Facchetti R, et al. Long-term risk of sustained hypertension in white-coat or masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54:226–232. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuspidi C, Rescaldani M, Tadic M, et al. White-coat hypertension, as defined by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, and subclinical cardiac organ damage: a meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2015;33:24–32. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trachsel LD, Carlen F, Brugger N, et al. Masked hypertension and cardiac remodeling in middle-aged endurance athletes. J. Hypertens. 2015;33:1276–1283. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancia G, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, et al. Long-term risk of mortality associated with selective and combined elevation in office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:846–853. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215363.69793.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung SH, Cheng HM, Wang KL, et al. White coat hypertension is more risky than prehypertension: important role of arterial wave reflections. Hypertension. 2013;61:1346–1353. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–2198. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verdecchia P, Reboldi GP, Angeli F, et al. Short- and long-term incidence of stroke in white-coat hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:203–208. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000151623.49780.89. (Epub 2004 Dec 13) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, et al. Prognostic significance of masked and white-coat hypertension in the general population: the Finn-Home study. J. Hypertens. 2012;30:705–712. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350a69b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cacciolati C, Hanon O, Dufouil C, et al. Categories of hypertension in the elderly and their 1-year evolution. The Three-City study. J. Hypertens. 2013;31:680–689. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835ee0ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierdomenico SD, Cuccurullo F. Prognostic value of white-coat and masked hypertension diagnosed by ambulatory monitoring in initially untreated subjects: an updated meta analysis. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011;24:52–58. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bobrie G, Clerson P, Menard J, et al. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J. Hypertens. 2008;26:1715–1725. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282fbcedf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru' M, et al. Age- and gender-specific awareness, treatment, and control of cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical vascular lesions in a founder population: the SardiNIA study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009;18:532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friz HF, Grassi G, Sega R, et al. Long-term risk of sustained hypertension in white-coat or masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54:226–232. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension, Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2013;31(2013):1925–1938. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328364ca4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Toumanidis S, Papamichael 2C, Lekakis J, Germanidis G, Hatzitolios A, Rizos Z, Sion M, Zakopoulos N. Target organ damage in “white coat hypertension” and “masked hypertension”. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008;21:393–399. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terracciano A, Scuteri A, Strait J, et al. Are personality traits associated with white coat and masked hypertension? J. Hypertens. 2014;32:1987–1992. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pauca AL, O'Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.