Abstract

Nurse residency programs are designed to increase competence and skill, and ease the transition from student to new graduate nurse. These programs also offer the possibility to positively influence the job satisfaction of new graduate nurses, which could decrease poor nursing outcomes. However, little is known about the impact of participation in a nurse residency program on new graduate nurses’ satisfaction. This review examines factors that influence job satisfaction of nurse residency program participants. Eleven studies were selected for inclusion, and seven domains influencing new graduate nurses’ satisfaction during participation in nurse residency programs were identified: extrinsic rewards, scheduling, interactions and support, praise and recognition, professional opportunities, work environment, and hospital system. Within these domains, the evidence for improved satisfaction with nurse residency program participation was mixed. Further research is necessary to understand how nurse residency programs can be designed to improve satisfaction and increase positive nurse outcomes.

The transition from student to new graduate nurse is marked by both opportunity for professional growth and risk for burnout and job dissatisfaction. The frequency of job turnover among newly hired nurse graduates is concerning, with 30% to 69% reporting that they voluntarily left their positions within a year of employment (Beecroft, Kunzman, & Krozek, 2001; Bowles & Candela 2005; Kells & Koerner, 2000; Winfield, Melo, & Myrick, 2009). Recognizing the difficulties associated with the transition from nursing student to new graduate nurse, the Institute of Medicine’s report, The Future of Nursing: Focus on Education (IOM, 2010), recommended the formation of nurse residency programs with the support of state boards of nursing, accrediting bodies, the federal government, and health care organizations as a means to address high turnover rates and improve quality of care.

Nurse residency programs help new graduate nurses transition from advanced beginners to competent professionals and focus on areas critical to new graduate success including communication, safety, clinical decision making and critical thinking, organizing and prioritizing, evidence-based practice, role socialization, and delegating and supervising (Spector, 2009). In addition to improving the quality of patient care, research suggests that these programs may address increased levels of stress, burnout (Laschinger, 2012; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2007), and job dissatisfaction that are associated with decreased staff productivity, turnover (Hinshaw & Atwood, 1983; Lu, While, & Barriball, 2005; Lucas, Atwood, & Hagaman, 1993), and hospital costs of up to $88,000 per nurse (Duffield, Roche, O’Brien-Pallas, & Catling-Paull, 2009; Jones, 2008). Estimates suggest the monetary return on investment of a 1-year nurse residency program may be as high as 884.75% (Beecroft et al., 2001; Pine & Tart, 2007). However, it is difficult to quantify the far-reaching effects of these programs, such as increases in new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. This systematic review explores the relationship between nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

In this review, nurse residency programs were defined as programs that enhance traditional hospital orientation and are composed of structured experiences that facilitate the obtainment of clinical and professional skills and knowledge necessary for new graduate nurses to provide safe and quality care (Goode & Williams, 2004; Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes, 2012). The following inclusion criteria were used:

New graduate nurses’ job satisfaction measured (quantitative or qualitative assessments).

Nurse residency program intervention and program techniques clearly defined.

Information regarding sample size provided.

Nurse residency program implemented in a U.S. hospital.

Article written in English.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

Electronic databases that were used included EMBASE™, PubMed® Plus, and Ovid® MEDLINE®. To find studies that explored factors relating to nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses’ perceptions of job satisfaction, key search terms used included nurse residency* or RN residency* and job satisfaction*.

Specific journals such as Journal of Nursing Management, The Journal of Nursing Administration, The Leadership Quarterly, Journal of Nursing Education, The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, and Nursing Management were also examined manually to ensure thoroughness. In addition to databases, select websites were explored for pertinent reports, including the American Organization of Nurse Executives (http://www.aone.org), Initiative on the Future of Nursing (http://www.thefutureofhursing.org), Institute of Medicine (http://www.iom.edu), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (http://www.rwjf.org), Sigma Theta Tau International (http://www.nursingsociety.org), University HealthSystem Consortium (http://www.uhc.edu), and Versant (http://www.versant.org). Website and manual searches produced a total of 17 titles and abstracts after removal of duplicates. A manual search of the reference lists found in the retrieved articles was performed to assure comprehensiveness.

Screening

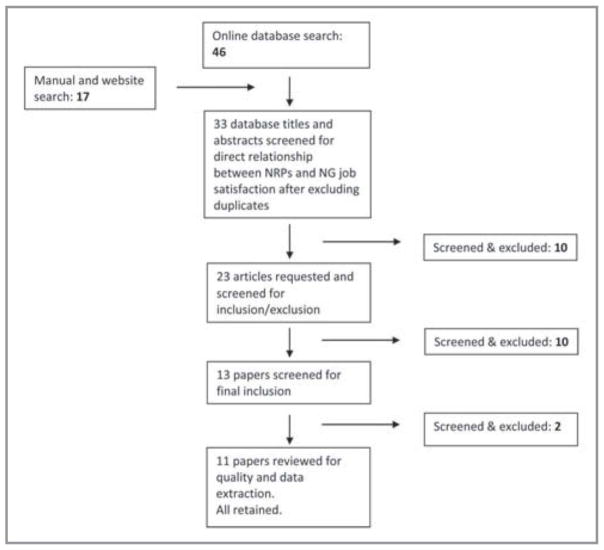

The titles and abstracts of 33 articles were reviewed (Figure 1). Of these, 23 were identified that specifically measured new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction in relation to nurse residency program participation. Thirteen of these articles met the remaining inclusion criteria. After removing one article that did not report a sample size and one article that was rated as “low validity” (Figure 2), 11 articles remained. These articles were retrieved for final screening, and all of these articles were retained for this review.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the search and retrieval process.

Note. NRPs = nurse residency programs; NG = new graduate nurses.

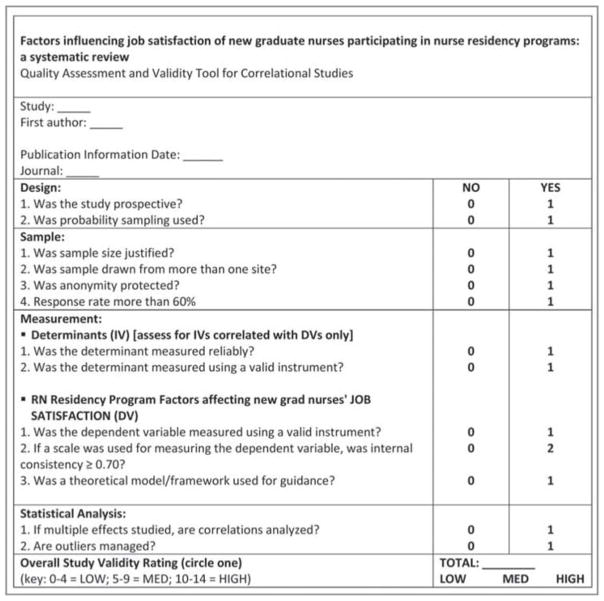

Figure 2.

Quality assessment and validity tool for correlational studies (adapted from Cummings & Estabrooks, 2003).

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from the final 11 studies:

Author.

Year.

Journal.

Objective of research.

Sample and sampling method.

Job satisfaction measurement instruments.

Measurement reliability and validity.

Nurse residency program components.

Study results.

Discussion.

Limitations.

Recommendations.

Quality Review

After considering all of the inclusion criteria, the remaining articles were reviewed for methodological quality using Cummings and Estabrooks’ quality rating tool (Figure 2), which has been used in many published systematic reviews (LaRocca, Yost, Dobbins, Ciliska, & Butt, 2012; Meijers et al., 2006; Van Lancker et al., 2012). Four themes were assessed in each of the 11 studies using this adopted tool: research design, sample, measurement, and statistical analysis. This measurement instrument included 13 items with a maximum of 14 possible points. Most items were assigned a score of 0 if the item was not met or a score of 1 if the item was met. Only the outcome measurement was scored using a score of up to 2 points. Studies were then placed into one of three categories using the following 14-point scale: strong (score = 10 to 14 points), moderate (score = 5 to 9 points), and weak (score = 0 to 4 points). Articles with weak validity were discarded.

Results

Summary of Quality Review

All 11 studies used predominantly quantitative instruments to measure job satisfaction and received quality scores of at least 5 points. The Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale and Halfer-Graf Job/Work Environment Nursing Satisfaction Survey included a few general open-ended questions about the new graduate nurse and nurse residency program experience (Casey, Fink, Krugman, & Propst, 2004; Halfer & Graf, 2006). Nine studies gathered data from more than one site, providing larger sample sizes and diversification. Job satisfaction instruments were either individually tested for reliability and validity by the authors within each article or extracted from published articles. Based on the established quality rating tool, alpha coefficients of at least 0.70 were considered favorable regarding reliability levels for new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction and were met in all 11 studies (Figure 2). Eight studies included nurse residency programs that referred to a theoretical model or framework on which to base the examined nurse residency program.

In the 11 studies, design, sampling, and analysis were the commonly identified weaknesses. All studies were nonexperimental in design, which limited analysis relating to causality. All but one study was prospective in design, and the lone retrospective study was one of two studies that had samples drawn from a single site (Setter, Walker, Connelly, & Peterman, 2011). Response rates were greater than 60% for three studies (Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs, 2009; Goode, Lynn, McElroy, Bednash, & Murray, 2013; Kowalski & Cross, 2010) and were not reported in two studies (Altier & Krsek, 2006; Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash, 2009). Few studies analyzed correlations to study multiple effects. Only two studies specifically mentioned anonymity of their sample (Altier & Krsek, 2006; Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode, 2008); however, Ulrich et al. (2010) mentioned confidentiality, and Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, and Lynn (2007) mentioned general identity protection. All of the studies used convenience sampling. Sample size rationale and management of outliers were not discussed explicitly. Table 1 summarizes the quality assessment of the 11 studies.

TABLE 1.

SUMMARY OF QUALITY ASSESSMENT

| Criteria | No. of Studies

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Design | ||

| Prospective studies | 10 | 1 |

| Used probability sampling | 0 | 11 |

| Sample | ||

| Appropriate or justified sample size | 10 | 1 |

| Sample drawn from more than one site | 9 | 2 |

| Anonymity protected | 2 | 9 |

| Response rate >60%a | 3 | 6 |

| Measurement | ||

| Reliable measure of determinant | 11 | 0 |

| Valid measure of determinant | 11 | 0 |

| Valid measure of job satisfaction | 11 | 0 |

| Job satisfaction internal consistency ≥0.70 | 11 | 0 |

| Theoretical model or framework used | 8 | 3 |

| Statistical analyses | ||

| Correlations analyzed when multiple effects studied | 4 | 7 |

| Management of outliers addressed | 0 | 11 |

Response rate was not available for two studies.

Characteristics of Studies Included

In-depth description and details of the included studies are provided in Table A (available in the online version of this article). The 11 studies were published between 2006 and 2013, and explored the perceptions of job satisfaction of new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs in various types of hospital settings, with study duration lasting from 1 to 10 years. Together, the studies included more than 9,000 nurses with either baccalaureate or associate degrees in nursing, with a mean age of 27.7 years (range = 18 to 59 years [age was reported in six studies only]), who were working in diverse clinical areas including women’s health, pediatrics, mental health, rehabilitation, oncology, critical care, perinatal nursing, perioperative services, and medical–surgical (Fink et al., 2008; Ulrich et al., 2010). Settings included university-affiliated medical centers and hospitals (Altier & Krsek, 2006; Fink et al., 2008; Goode et al., 2009, 2013; Krugman et al., 2006; Setter et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2007), hospitals in a midwestern health care system (Anderson et al., 2009), hospitals in Las Vegas (Kowalski & Cross, 2010), and Magnet-designated centers (Krugman et al., 2006; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012). Thus, a diverse range of geographic regions and locations were represented.

Table A.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author(s)/ Journal |

Framework (F) or Objective (O) |

Subjects | Intervention and Length/Program Techniques |

Times of Job Satisfaction Measurement |

Measurement Instrument for Job Satisfaction |

Scoring | Reliability | Validity | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altier & Krsek (2006). Journal for Nurses in Staff Development | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982), based on the theory of skill acquisition of Dreyfus (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1980) |

111 baccalaureate-prepared graduate nurses from six academic medical centers across the U.S. | 1-year program: pilot test of UHC/AACN residency program Curriculum themes:

Key elements:

|

Initially at hiring and on completion of program | McCloskey–Mueller Satisfaction Survey - 8 subscales, 31 items (Mueller & McCloskey, 1990) | 5-point Likert scale | α = 0.89 | Construct validity Criterion-related validity (r = .53 to .75) |

Paired t test, analysis of covariance |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009). The Journal of Nursing Administration | O: To measure job satisfaction and engagement perceptions of new nurses after completing interactive residency modules |

90 new graduate nurses in a midwestern health care system with 5 metropolitan hospitals | 1-year program: created and implemented within health care system Interactive session themes:

Key elements:

|

Before and after attending nurse residency education sessions | Halfer-Graf Job/Work Environment Nursing Satisfaction Survey - 21 items (Halfer& Graf, 2006) | 4-point Likert-type scale | Pearson-Brown split/half reliability = 0.8962 | Survey tool items validated by members of nursing recruitment and retention committee in the study setting | Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test, thematic analysis |

| Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode (2008). The Journal of Nursing Administration | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

434 graduate nurse residents from the first 12 academic hospital sites in the UHC/AACN residency program hired between May 2002 and September 2003 and had fully completed the 1-year residency program | 1-year program: UHC/AACN Nurse Residency Program (components not explicitly defined in study) | On hire, 6 months into program, and 12 months on completion of program | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale - 9 items pertaining to job satisfaction (Casey, Fink, Krugman, & Propst, 2004) | 4-point Likert-type items | α = 0.89 | Content validity | Focused on qualitative data outcomes from open-ended questions: findings compared, cover terms and common themes identified across institutions and periods |

| Goode, Lynn, McElroy, Bednash, & Murray (2013). The journal of Nursing Administration | F: AACN Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

1,016 new graduate residents who participated in the UHC/AACN Nursing residency from 2002 through 2012 | 1 year program: UHC/AACN residency program Core curriculum content:

Key elements:

|

At program start, 6 months into program, and 12 months on completion of program | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale | 4-point Likert-type items | α = 0.89 | Content validity | ANOVA, exploratory factor analysis (principal axis factoring with varimax rotation) |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009). Nursing Economic$ | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

655 residents who were hired by 26 academic medical center hospitals between September 15, 2004 and September 15, 2005 | 1-year program UHC/AACN residency program (*mentions that overview of program can be found in Krugman*) | On hire, 6 months into program, and 12 months on completion of program | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale McCloskey–Mueller RN Job Satisfaction Scale |

4-point Likert-type items 5-point Likert scale |

α = 0.89 α = 0.89 |

Content validity Construct validity |

ANOVA |

| Kowalski & Cross (2010). Journal of Nursing Management | O: To report preliminary findings regarding new graduate nurses participating in a year-long local residency program at two hospitals in Las Vegas |

55 BSN and ADN new graduate nurses participating in 1-year local residency program at two hospitals | 1-year program created and implemented within the two hospitals Educational modules:

Key elements:

|

During third and twelfth month of program | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale | 4-point Likert-type items | α = 0.71 to 0.90 | Content validity | Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test, Friedman’s test, exact P values based on permutation distribution |

| Krugman et al. (2006). Journal for Nurses in Staff Development | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

Participants from first year of program operation at first six pilot sites | 1-year program: UHC/AACN residency program Core curriculum content:

Key elements:

|

At program start, 6 months into program, and 12 months on completion of program | McCloskey–Mueller Satisfaction Survey Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale |

5-point Likert Scale 4-point Likert-type items |

α = 0.82 α = 0.89 |

Construct validity Content validity |

Mean score comparison over time |

| Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012). Journal for Nurses in Staff Development | O: To evaluate a year-long nurse residency program using a non-experimental, repeated measures design with qualitative questions |

31 new graduate nurses at a 507-bed Magnet-designated regional medical center | 1-year program created and implemented within medical center Key elements:

|

During sixth month and twelfth month after hire | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale | 4-point Likert-type items | α = 0.81 to 0.90 | Content validity | Wilcoxon signed-ranks; significant t test; qualitative descriptive naturalistic inquiry approach with constant comparison |

| Setter, Walker, Connelly, & Peterman (2011). Journal for Nurses in Staff Development | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

100 BSN nurses who had completed the NRP since its inception in 2003 and who were still employed at the University of Kansas Hospital in 2007 | 1-year program: UHC/AACN Nurse Residency Program Curriculum themes:

Key elements:

|

Varying period of time after completion of program | McCloskey–Mueller Satisfaction Survey | 5-point Likert scale | α = 0.922 | Construct validity | Regression analysis comparison to predictive model, content analysis |

| Ulrich et al. (2010). Nursing Economic$ | F: Benner’s Novice to Expert model (1982) |

Over 6,000 new graduate nurses who completed the RN residency over a 10-year period | Varies in length: Versant RN Residency Curriculum:

|

At end of program, month 12 after program completion, month 24 after program completion, and month 60 after program completion only for organizational job satisfaction | The Nurse Job Satisfaction Scale - 3 subscales The Work (Organizational Job) Satisfaction Scale - 5 subscales, 27 items |

Likert-type (Hinshaw & Atwood, 1983) 5-point Likert-type scale (Slavitt et al., 1979) |

α = 0.90 α = 0.87 |

Not reported Not reported |

Data reduction and multiple imputation, correlation matrix analysis, generation and inspection of descriptive statistics for demographic variables as well as each scale and subscale, and regression analysis |

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007). The Journal of Nursing Administration | F: Baccalaureate foundation as described in The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education, conceptual work of Dreyfus as described by Benner and the work of Benner et al. (1982) |

Data on 2 cohorts of residents (n = 679) in 12 sites across the country | 1-year program: UHC/AACN Nurse Residency Program Components of program:

Key elements:

|

At program start, 6 months into program, and 12 months on completion of program | Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Scale McCloskey–Mueller Satisfaction Survey |

4-point Likert-type items 5-point Likert scale |

α = 0.89 α = 0.58 to 0.82 for subscales in study |

Content validity Construct validity |

ANOVA, exploratory factor analysis (principal axis factoring with Varimax rotation) |

Note. UHC/AACN = University HealthSystem Consortium/American Association of Colleges of Nursing; ANOVA = analysis of variance; BSN = baccalaureate nursing degree; ADN = associate degree in nursing; NRP = nurse residency program.

Study Results

Theoretical Framework

Eight of the 11 studies involved nurse residency programs that were structured after a theoretical model. Seven of these studies involved participants in the national University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC)/American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) Nurse Residency Program, and one study involved participants in the Versant Residency Program. Both types of nurse residency programs involve a formal curriculum built on Benner’s novice to expert model (1982) that is derived from the theory of skill acquisition developed by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1980). In their model, Dreyfus and Dreyfus postulated that students must transition through five levels of proficiency: novice, beginner, competent, proficient, and expert; Benner modified and applied their model to nursing practice. The nurse residency programs in the studies were designed to accommodate “advanced beginners” lacking expertise and experience related to prioritization and confidence in caring for clinically complex patients (Benner, 1982; Goode et al., 2009).

Characteristics of Nurse Residency Programs

The goal of implementing nurse residency programs in the 11 studies was to facilitate the transition of new graduate nurses to professional nurses through guided clinical experiences with nurse preceptors, support from mentors and other staff members, various seminars and learning opportunities to increase competency and safe patient care that meet defined standards of practice, and other additional experiences with desired outcomes that included enhanced job satisfaction and reduction of new graduate nurse turnover (Altier & Krsek, 2006; Ulrich et al., 2010). With the exception of the Versant Residency Program, which varies in length, all of the nurse residency programs in the included studies lasted one year, which is the minimum length of time in an acute setting that new graduate nurses identified as necessary to be comfortable and confident in their new roles (Casey et al., 2004).

The UHC/AACN Nurse Residency Program, which has been implemented in 92 practice sites in 30 states, considers quantified areas of new graduate nurses satisfaction relating to 36 skills and involves a core curriculum that focuses on leadership, patient safety and outcome, and the professional nursing role in addition to providing other educational experiences through interprofessional exercises and simulations (AACN, 2014; Berkow, Virkstis, Stewart, & Conway, 2008; Goode et al., 2013; Krsek & McElroy, 2009). The Versant RN Residency Program, implemented in 82 sites, involves a structured curriculum aimed to facilitate the transition of new graduate nurses to professional nurses through clinical experience, preceptors, mentors, and debriefing and self-care sessions (Ulrich et al., 2010; Versant, 2013). Three of the 11 studies examined individualized residency programs similar to the two more widely implemented nurse residency programs, emphasizing support from nursing staff as well as educational experiences to promote clinical competency and safe transition into the professional nursing workforce (Anderson et al., 2009; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012).

Measure of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction

Five instruments were used for initial and repeat testing to specifically measure factors affecting new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction, with some studies using multiple instruments. The instruments included four that exclusively measured job satisfaction: the McCloskey-Mueller Satisfaction Survey (MMSS), the Halfer-Graf Job/Work Environment Nursing Satisfaction Survey, the Nurse Job Satisfaction Scale, and the Work (Organizational Job) Satisfaction Scale. The Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Survey also includes survey sections specifically measuring changes in confidence when communicating with others, which were included in this article because research suggests communication as assessed by “confident communicating” with physicians and patients, as well as interactions with physicians, affect job satisfaction (Goode et al., 2009, 2013; Halfer & Graf, 2006; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Mueller & McCloskey, 1990; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2007).

Analytical Findings: Determinants of Job Satisfaction

In total, 21 factors contributing to job satisfaction outcomes of new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs were identified and synthesized into seven broad categories (Table 2). The predictors, through the use of content analysis, were assembled into the following categories:

TABLE 2.

FACTORS OF NURSE RESIDENCY PROGRAMS INFLUENCING NEW GRADUATES’ JOB SATISFACTION

| Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction | Source | Findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic rewards | |||

| Vacation, salary, benefits | Altier & Krsek (2006) | NS | |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | V | Significant decrease from T1-T2, significant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012) | NS | ||

| Ulrich et al. (2010) | − | Satisfaction with pay | |

| Scheduling | |||

| Fairness | Altier & Krsek (2006) | NS | Significant decrease from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | V | Significant decline from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007) | V | Significant decline from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012) | NS | Perception that staffing schedules were managed fairly | |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009) | −− | ||

| Interactions and support | |||

| Professional RN Interactions, including support from RN peers, mentors, preceptors; teamwork; respect | Altier & Krsek (2006) | NS | |

| Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode (2008) | * | Satisfaction with support, camaraderie, and positive interactions; dissatisfaction with generational differences with RN team, lack of respect and recognition from coworkers, gossipy and grumpy staff, and lack of teamwork | |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | V | Significant decrease from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Krugman et al. (2006) | + | ||

| Ulrich et at. (2010) | + | Nursing personnel helping one another | |

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007) | V | Alpha sites: Insignificant decline from T1-T2, significant increase from T2-T3 | |

| +/++ | Beta sites: Insignificant increase from T1-T2, significant increase from T2-T3 | ||

| Kowalski & Cross (2010) | + | ||

| Goode, Lynn, McElroy, Bednash, & Murray (2013) | NS | Insignificant increase from T1-T2, insignificant decline from T2-T3 | |

| Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012) | ++ | Satisfaction with support from nurses on unit; support from and connection with peers | |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009) | + | Teamwork and support of tenured staff, availability of trusted preceptors and mentors; dissatisfaction with backstabbing, grumbling, and gossiping among staff | |

| Communication and inter actions with non-RN team members, including with physicians and with patients and families | Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012) | ++ | |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | ++ | ||

| Kowalski & Cross (2010) | ++ | ||

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007) | ++ | ||

| Goode, Lynn, McElroy, Bednash, & Murray (2013) | ++ | ||

| Ulrich et al. (2010) | + | Mingling with others of different professions | |

| Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode (2008) | * | Satisfaction with caring and connecting with patients | |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009) | + | Satisfaction with decrease in physician disrespect later in the patient care experience, acceptance by interdisciplinary team members and having professional contributions valued | |

| * | Helping patients and watching them get better, and patient satisfaction | ||

| Praise and recognition | |||

| Praise and recognition from staff, including from supervisors, superiors, and peers | Altier & Krsek (2006) | −− | |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | V | Significant overall decrease from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007) | V | Significant overall decrease from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Professional opportunities | |||

| Opportunities for advance ment such as through interactions with faculty, participation in research | Altier & Krsek (2006) | −− | |

| Goode, Lynn, Krsek, & Bednash (2009) | V | Significant decrease from T1-T2, significant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Williams, Goode, Krsek, Bednash, & Lynn (2007) | V | Significant decrease from T1-T2, insignificant increase from T2-T3 | |

| Olson-Sitki, Wendler, & Forbes (2012) | NS | Opportunities for advancement | |

| Ulrich et al. (2010) | + | ||

| Work environment | |||

| Ratios, futility of care, workload, voice in planning policies, staffing plans | Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode (2008) | * | Dissatisfaction with impractical nurse-to-patient ratios, tough schedules, futility of care in particular patient care situations, perceived increased workload with decreased support from ancillary personnel |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009) | * | Dissatisfaction with staffing plans and ratios | |

| Hospital system | |||

| Outdated facilities and equipment, unfamiliarity with unit and departments, electronic medical records | Fink, Krugman, Casey, & Goode (2008) | * | Dissatisfaction with outdated facilities and equipment, unfamiliarity with unit and departments, electronic medical records |

| Anderson, Linden, Allen, & Gibbs (2009) | * | Technological advances to improve efficiency of delivery of care (e.g., medication bar coding, electronic nurse-to-nurse handoff technology) were implemented in response to RN satisfaction surveys | |

Note. T1 = time 1; T2 = time 2; T3 = time 3; NS = not statistically significant; V = decrease followed by increase; + = increase but significance not reported in study; − = decrease but significance not reported in study; ++ = significant increase: −− = significant decrease;* = quantitative data.

Extrinsic rewards.

Scheduling.

Interactions and support.

Praise and recognition.

Professional opportunities.

Work environment.

Hospital system.

Not all of the studies examined all of the predictors.

Extrinsic Rewards

Four studies explored the influence of extrinsic rewards on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction, although none mentioned whether these awards, including vacation, salary, or benefits, varied during the course of the residency program, which may influence perceptions of job satisfaction over time. Two studies examined extrinsic rewards by considering vacation, salary, and benefits in the overall score for extrinsic rewards satisfaction. Of these, one study found that there was no significant change in job satisfaction before and after completion of the nurse residency program (Altier & Krsek, 2006). In the second study, a significant decrease in satisfaction was noted at 6 months, followed by a significant increase at nurse residency program completion (Goode et al., 2009). A third study revealed no differences between 6 and 12 months for the three items under this category (Olson-Sitki et al., 2012). The lone longitudinal study in this review showed a continual decrease in pay satisfaction from the end of the nurse residency program to 60 months after nurse residency program completion but did not report measures of significance (Ulrich et al., 2010). These findings suggest that satisfaction with extrinsic rewards does not change significantly during the course of a nurse residency program.

Scheduling

The process of scheduling shifts was examined as a basis for job satisfaction of new graduate nurses in five studies. This category’s results were inconclusive, as two studies revealed no significant changes throughout the time periods measured (Altier & Krsek, 2006; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012). However, two other studies revealed a “V” pattern, in which there was a significant decline in scheduling satisfaction from the time of program entry to 6 months, followed by an increase in the second half of the program (Goode et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007). The final study found a significant decrease in satisfaction, which was attributed to declining perception of fair staffing schedule management (Anderson et al., 2009). This suggests that new graduate nurses’ satisfaction with scheduling decreases or stays the same during the residency period.

Interactions and Support

Two kinds of interactions identified by nurse residency program participants were studied to determine their relationships with new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. All 11 studies examined the effect of interactions with other nursing professionals, including receiving support and feedback from nursing peers, mentors, and preceptors. Qualitative findings revealed that support, camaraderie, and positive interactions with staff led to satisfaction, whereas “gossipy and grumpy staff” and lack of teamwork, respect, and recognition from coworkers were factors causing dissatisfaction (Anderson et al., 2009; Fink et al., 2008). Quantitative findings on the impact of interactions with nurse and nurse-support staff on new graduate nurses’ satisfaction varied. However, interactions with physicians, patients, and families were identified as positively and more often significantly related to new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction in quantitative and qualitative data. These findings suggest that interactions with nursing and non-nursing staff have an impact on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction, with non-nursing interactions having a larger impact.

Praise and Recognition

The impact of praise and recognition on new graduate nurses’ satisfaction was mixed. Two studies revealed a “V” pattern in which satisfaction with praise and recognition initially significantly declined, but insignificantly increased from 6 months to program completion (Goode et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007). A third study revealed a significant decrease in satisfaction with praise and recognition over the course of the nurse residency program (Altier & Krsek, 2006). More information is needed to understand the satisfaction of new graduate nurses with the praise and recognition received over the course of the program.

Professional Opportunities

Five studies examined the effect of professional opportunities on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. The findings of Ulrich et al. (2010) suggested an increase in satisfaction, but statistical significance was not reported. Two studies revealed a “V” pattern (Goode et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007), with initially decreasing satisfaction, followed by an increase by program termination. A third study found no significant changes during the course of the program (Olson-Sitki et al., 2012). The final study revealed a significant decline in satisfaction with professional opportunities (Altier & Krsek, 2006). These results do not show a clear pattern of satisfaction with professional opportunities associated with a nurse residency program.

Work Environment

Two studies explored the effects of the working environment on job satisfaction of new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs using qualitative results, which revealed dissatisfaction with the work environment. Perceptions of unrealistic patient assignments, tough schedules, futility of patient care, and increase in workload with limited assistance from support staff were determinants of new graduate nurses’ dissatisfaction in one study (Fink et al., 2008). Anderson et al. (2009) also revealed consistent suggestions for job satisfaction improvement regarding staffing plans and ratios throughout program participation. These studies suggest that new graduate nurses’ perceptions of job satisfaction relating to the work environment persist during the course of a nurse residency program.

Hospital System

Through the use of qualitative data, two studies found dissatisfaction with aspects of the hospital system. One study found outdated facilities and equipment, unfamiliarity with the unit and hospital departments, and electronic medical records as factors related to new graduate nurses’ dissatisfaction that persisted throughout the nurse residency program (Fink et al., 2008). In response to new graduate nurse satisfaction surveys, a second study implemented technological advances such as medication bar coding and electronic nurse-to-nurse handoff to improve care delivery efficiencies (Anderson et al., 2009). These findings suggest that nurse residency programs do not alleviate dissatisfaction with aspects of the hospital system.

Discussion

This study identified evidence of varying strength, which suggests that the seven categories composed of 21 factors associated with nurse residency programs (Table 2) have some influence on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. Evidence shows that job dissatisfaction negatively affects new graduate nurse retention rates (Setter et al., 2011), yet understanding of the role of various factors is incomplete.

Organizational and administrative factors had varying impact on new graduate nurses’ satisfaction. Although there were no significant changes regarding extrinsic rewards, satisfaction with scheduling decreased during the course of the nurse residency program. The work environment and hospital system were factors that resulted in persistent new graduate nurses’ job dissatisfaction over time (Table 2). Although these findings may not be a direct cause of nurse residency program participation based on published nurse residency program curricula and the foci of these programs, these findings are worth noting, as job dissatisfaction negatively affects new graduate nurse retention rates (Setter et al., 2011).

Positive interpersonal relationships and interactions affected satisfaction throughout the nurse residency program. Building relationships and experiencing effective communication with nursing staff as well as with physicians, patients, and families improved satisfaction and increased a sense of belonging (Fink et al., 2008; Goode et al., 2009, 2013; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2007). Perceptions of support and strong nursing leadership as well as perceived respect from physicians also increased satisfaction (Anderson et al., 2009; Kowalski & Cross, 2010).

Along with administrative and interpersonal factors, new graduate nurses’ changing self-perception impacted satisfaction during the nurse residency program. During the first 6 months, many new graduate nurses participate in specialty classes that require learning a potentially overwhelming amount of new information (Williams et al., 2007). This may explain the observed decline and rebound of satisfaction as new graduate nurses adjust their views on the nursing profession and their own self-confidence through real work experience. Kramer (1974) describes a “reality shock” with a transition from the academic setting to a professional setting, accompanied by the realization of the different priorities and pressures that the two entail. More recently, Boychuk Duchscher (2009) presents a theory of “transition shock” with engagement in a new professional practice role that requires a broad range of physical, emotional, developmental, intellectual, and sociocultural adjustments. Bolstered by experience and confidence, new graduate nurses may require less praise and recognition for perceived job satisfaction, and also explore opportunities for advancement and take on new roles.

Implications for Nurse and Health Leaders

This analysis provides information that can be used to minimize new graduate nurses’ dissatisfaction and increase future new graduate nurse retention, as called for in the IOM (2010) report. First, these findings strongly support the need to engage capable facilitators, mentors, and preceptors in nurse residency programs. The effectiveness of preceptor programs has been widely recognized in the literature (Santucci, 2004), and the importance of careful selection of mentors has been discussed elsewhere (Eby et al., 2013). Second, the evidence presented in this article shows that opportunities for interaction with other new graduate nurses provide a sense of belonging and support that improves new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction (Fink et al., 2008; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012), suggesting that opportunities for peer engagement are an important component of programs designed to improve satisfaction and retention. Third, new graduate nurses’ increased confidence in communicating with physicians, as well as improved satisfaction relating to praise and recognition, may be related to increased feelings of competence. This emphasizes the importance of continuing strong educational opportunities to strengthen new graduate nurses’ skills and to promote seamless academic progression as emphasized in the IOM report. These recommendations can be implemented immediately by hospital leaders.

The need for support by new graduate nurses in the 11 studies is a global one, as structured nurse graduate programs to support both clinical and social new graduate nurses’ needs were identified as necessary in a rural setting in Australia (Bennett, Barlow, Brown, & Jones, 2012), as well as in a hospital in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Fielden, 2012). Aiken et al. (2001) found that job dissatisfaction among nurses was highest in the United States (41%), followed by Scotland (38%), England (36%), Canada (33%), and Germany (17%). As health leaders in other nations are also addressing similar concerns as those suggested in the IOM (2010) report, including the need for nursing support, lifelong learning, and professional development, these leaders are encouraged to turn to their global peers and learn from and work with one another to identify bright spots that may be transferable to any health care setting.

Limitations

This review is based on findings from 11 studies that evaluated several different models of nurse residency programs. Each study evaluated in this article used convenience sampling, and the nurses surveyed may be significantly different than the general population. In each study, participants were aware that they were participating in a nurse residency program, and repeat testing may have simulated intervention effects by making participants more aware of and consequently report superficially increased changes in satisfaction over time. The variability in satisfaction measurements as well as time periods may decrease the validity and generalizability of the findings of this study. Many factors extrinsic to the nurse residency program, including the economic climate, longevity of leadership, quality outcomes within the health care organizations, and patient population, may influence experiences of new graduate nurses. The limitations in these studies affect the findings of this article.

Future Research

More research is needed to determine whether nurse residency programs can increase retention rates, given that the IOM report on The Future of Nursing (2010) encourages health care organizations to evaluate the effectiveness of nurse residency programs in improving the retention rates of nurses. Longitudinal studies such as the study by Ulrich et al. (2010) should be more widely used to determine short-term and long-term retention rates of the same new graduate nurse sample, which many of the 11 studies were unable to do without follow-up surveys months and years after program completion. Whether economic recessions and temporary surpluses of new graduate nurses in different areas throughout the United States artificially support retention of each sample also should be considered.

Although it is promising that many nurse residency programs were influenced by a conceptual framework, Benner’s (1982) novice to expert model does not specifically mention variables potentially affecting new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction as they transition from novice to expert. Further usage of models should consider how theoretical approaches to the many aspects of nurse residency programs may specifically affect new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. In addition, only two of the studies used qualitative methods to elicit responses about new graduate nurses’ satisfaction (Anderson et al., 2009; Fink et al., 2008). As this is a relatively new area of inquiry, and factors affecting new graduate nurses’ satisfaction may differ markedly from those of more experienced nurses, future qualitative studies could enhance clarity and depth of understanding of the influence of nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction.

The reoccurring “V” pattern findings may indicate an opportunity for program design evaluation, as new graduate nurses’ needs may differ during the course of their first year as practicing nurses. Nurse residency program creators and implementers could assess potential changes in needs to determine what changes can improve perceptions of new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction during the first half of the nurse residency program. As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services funds nationally accredited nurse residency programs (AACN, 2009), nurse and health leaders can implement already accredited nurse residency programs or apply for their own nurse residency program accreditation; awarded resources can then be allocated accordingly to address the findings from this analysis and further support the IOM’s (2010) recommendations.

Finally, future studies should investigate specific interventions both individually and jointly to advance knowledge of the influences among nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. The relationships among and between the various components of nurse residency programs that are each recognized as influencers of new graduate nurses’ perceptions of job satisfaction are multifaceted. Additional studies may help determine the inter-relationship of factors and themes by analyzing alongside one another the aspects identified by new graduate nurses as important determinants of their job satisfaction.

Because all 11 of the studies included in this article used nonexperimental designs, further studies should involve randomized clinical trials to investigate whether changes in new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction perceptions have a direct causal relationship with nurse residency programs, as job satisfaction with the identified categories in this article may similarly affect perceptions of job satisfaction for any new nurse regardless of nurse residency program participation. For more conclusive findings, future studies should thus observe changes in job satisfaction for the same categories during the same period of time for two different samples: new graduate nurses not participating in nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs. This will further help health care leaders determine how best to allocate resources and monies to align with the IOM’s (2010) recommendations in The Future of Nursing report.

Conclusion

Through this systematic review, an overall positive relationship between interactions and support and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction was identified; however, new graduate nurses reported consistent dissatisfaction with their work environment and the hospital system, as well as declining satisfaction with fair staff scheduling. The relationships between the remaining categories with new graduate nurses’ satisfaction did not reveal conclusive findings over the course of the nurse residency program. Providing new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs with more control over scheduling, being mindful of when increased praise and recognition may be needed by new graduate nurses, and creating more opportunities for new graduate nurses to develop as health care professionals may help to more conclusively determine the effects of specific aspects of nurse residency programs on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. The IOM (2010) recommended that health care organizations, the Health Resources and Services Administration, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and philanthropic organizations help finance the formation and application of nurse residency programs. It is thus crucial that nursing scholars and health care organizations have a clear understanding of which nurse residency program components influence new graduate nurses’ perceptions of job satisfaction to make policy and nurse residency program recommendations. Ultimately, these efforts strive to support and retain new graduate nurses not only to promote both high-quality and efficient care, but also to ensure the consequent positive patient and nurse outcomes.

HOW TO OBTAIN CONTACT HOURS BY READING THIS ISSUE.

Instructions

1.3 contact hours will be awarded by Villanova University College of Nursing upon successful completion of this activity. A contact hour is a unit of measurement that denotes 60 minutes of an organized learning activity. This is a learner-based activity. Villanova University College of Nursing does not require submission of your answers to the quiz.A contact hour certificate will be awarded once you register, pay the registration fee, and complete the evaluation form online at https://villanova.gosignmeup.com/dev_students.asp?action=browse&main=Nursing+Journals&misc=564. In order to obtain contact hours you must:

Read the article, “Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction of New Graduate Nurses Participating in Nurse Residency Programs: A Systematic Review,” found on pages 439–450, carefully noting any tables and other illustrative materials that are included to enhance your knowledge and understanding of the content. Be sure to keep track of the amount of time (number of minutes) you spend reading the article and completing the quiz.

Read and answer each question on the quiz. After completing all of the questions, compare your answers to those provided within this issue. If you have incorrect answers, return to the article for further study.

Go to the Villanova website to register for contact hour credit. You will be asked to provide your name, contact information, and a VISA, MasterCard, or Discover card number for payment of the $20.00 fee. Once you complete the online evaluation, a certificate will be automatically generated.

This activity is valid for continuing education credit until September 30,2016.

CONTACT HOURS

This activity is co-provided by Villanova University College of Nursing and SLACK Incorporated.

Villanova University College of Nursing is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation.

OBJECTIVES

Describe the various determinants of job satisfaction.

Identify areas for future research of nurse residency programs and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction and retention.

KEY POINTS.

New Graduate Nurses’ Job Satisfaction

Lin, P.S., Viscardi, M.K. & McHugh, M.D. (2014). Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction of New Graduate Nurses Participating in Nurse Residency Programs: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 45(10), 439–450.

Research suggests that nurse residency programs may address job dissatisfaction associated with decreased staff productivity, turnover, and hospital costs.

Extrinsic rewards, scheduling, interactions and support, praise and recognition, professional opportunities, work environment, and hospital system were predictors found to contribute to perceived job satisfaction of new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs.

Significant gaps exist in determining the direct relationship between nurse residency program participation and new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction, thus creating room for further research that can consequently influence nurse residency program design, policy changes, and health care resource allocation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Neither the planners nor the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Ms. Patrice S. Lin, Clinical Nurse, Stanford Hospital and Clinics, Stanford, California.

Dr. Molly Kreider Viscardi, predoctoral fellow, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing.

Dr. Matthew D. McHugh, Rosemarie Greco Term Endowed Associate Professor in Advocacy, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

References

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clark H, Shamian J. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier ME, Krsek CA. Effects of a 1-year residency program on job satisfaction and retention of new graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2006;22:70–77. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Background of CCNE’s accreditation of post-baccalaureate nurse residency programs. 2009 Retrieved from http://apps.aacn.nche.edu/Accreditation/nrpbackground.htm.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nurse residency program. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/nurse-residency-program.

- Anderson T, Linden L, Allen M, Gibbs E. New graduate RN work satisfaction after completing an interactive nurse residency. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2009;39:165–169. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31819c9cac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft PC, Kunzman L, Krozek C. RN internship: Outcomes of a one-year pilot program. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2001;31:575–582. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. From novice to expert. American Journal of Nursing. 1982;82:402–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett P, Barlow V, Brown J, Jones D. What do graduate registered nurses want from jobs in rural/remote Australian communities? Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;20:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkow S, Virkstis K, Stewart J, Conway L. Assessing new graduate nurse performance. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008;38:468–474. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000339477.50219.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles C, Candela L. First job experiences of recent RN graduates: Improving the work environment. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35:130–137. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boychuk Duchscher JE. Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:1103–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey K, Fink R, Krugman M, Propst J. The graduate nurse experience. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2004;34:303–311. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings GG, Estabrooks CA. The effects of hospital restructuring that included layoffs on individual nurses who remained employed: A systematic review. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2003;23(8/9):8–53. doi: 10.1108/01443330310790633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus SE, Dreyfus HL. A five stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. California University Berkeley Operations Research Center; 1980. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a084551.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield C, Roche M, O’Brien-Pallas L, Catling-Paull C. Implications of staff ‘churn’ for nurse managers, staff, and patients. Nursing Economic. 2009;27:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby LT, Allen TD, Hoffman BJ, Baranik LE, Sauer JB, Baldwin S, Evans SC. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:441–476. doi: 10.1037/a0029279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielden JM. Managing the transition of Saudi new graduate nurses into clinical practice in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;20:28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink R, Krugman M, Casey F, Goode C. The graduate nurse experience: Qualitative residency program outcomes. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008;38:341–348. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000323943.82016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode CJ, Lynn MR, Krsek C, Bednash GD. Nurse residency programs: An essential requirement for nursing. Nursing Economic. 2009;27:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode CJ, Lynn MR, McElroy D, Bednash GD, Murray B. Lessons learned from 10 years of research on a post-baccalaureate nurse residency program. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2013;43:73–79. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31827f205c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode CJ, Williams CA. Post-baccalaureate nurse residency program. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2004;34:71–77. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfer D, Graf E. Graduate nurse perceptions of the work experience. Nursing Economic. 2006;24:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw AS, Atwood JR. Nursing staff turnover, stress, and satisfaction: Models, measures, and management. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 1983;1:133–153. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-40453-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Focus on education. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CB. Revisiting nurse turnover costs: Adjusting for inflation. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008;38:11–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000295636.03216.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kells K, Koerner DK. Supporting the new graduate nurse in practice. Kansas Nurse. 2000;75(7):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski S, Cross CL. Preliminary outcomes of a local residency programme for new graduate registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2010;18:96–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. Reality shock: Why nurses leave nursing. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Krsek C, McElroy D. A solution to the problem of first-year nurse turnover. Oak Brook, IL: University HealthSystem Consortium; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman M, Bretschneider J, Horn PB, Krsek CA, Moutafis RA, Smith MO. The national post-baccalaureate graduate nurse residency program: A model for excellence in transition to practice. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2006;22:196–205. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Butt M. The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:751. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS. Job and career satisfaction and turnover intentions of newly graduated nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;20:472–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, While AE, Barriball L. Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas MD, Atwood JR, Hagaman R. Replication and validation of anticipated turnover model for urban registered nurses. Nursing Research. 1993;42:29–35. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijers JM, Janssen MA, Cummings GG, Wallin L, Estabrooks CA, Halfens RYG. Assessing the relationships between contextual factors and research utilization in nursing: Systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;55:622–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CW, McCloskey JC. Nurses’ job satisfaction: A proposed measure. Nursing Research. 1990;39:113–117. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson-Sitki K, Wendler MC, Forbes G. Evaluating the impact of a nurse residency program for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2012;28:156–162. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e31825dfb4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine R, Tart K. Return on investment: Benefits and challenges of a baccalaureate nurse residency program. Nursing Economic. 2007;25:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute. What works: Healing the healthcare staffing shortage. New York, NY: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Santucci J. Facilitating the transition into nursing practice: Concepts and strategies for mentoring new graduates. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2004;20:274–284. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setter R, Walker M, Connelly LM, Peterman T. Nurse residency graduates’ commitment to their first positions. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2011;27:58–64. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e31820eee49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavitt D, Stamps P, Piedmont E, Maase AM. Measuring nurses’ job satisfaction. Hospital & Health Services Administration. 1979;24(3):62–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector N. Description of NCSBN’s transition to practice model. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nursing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich B, Korzek C, Early S, Ashlock CH, Africa L, Carman ML. Improving retention, confidence, and competence of new graduate nurses: Results from a 10-year longitudinal database. Nursing Economic$ 2010;28:363–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lancker A, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Goossens J, Beeckman D. The association between malnutrition and oral health status in elderly in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2012;49:1568–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versant. Current Versant client list. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.versant.org/about/client-map.html#!/catid=1.

- Williams CA, Goode CJ, Krsek C, Bednash GD, Lynn MR. Postbaccalaureate nurse residency 1-year outcomes. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2007;37:357–365. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000285112.14948.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield C, Melo K, Myrick F. Meeting the challenge of new graduate role transition: Clinical educators leading the change. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2009;25(2):E7–E13. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e31819c76a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]