Summary

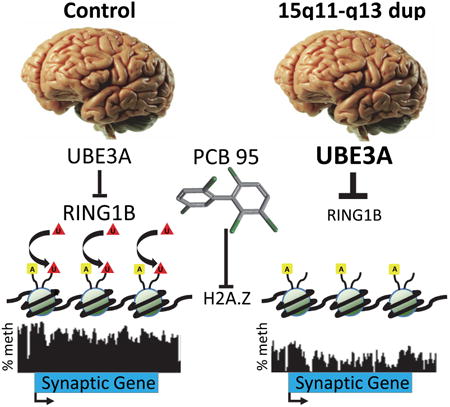

Rare variants enriched for functions in chromatin regulation and neuronal synapses have been linked to autism. How chromatin and DNA methylation interact with environmental exposures at synaptic genes in autism etiologies is currently unclear. Using whole genome bisulfite sequencing in brain tissue and a neuronal cell culture model carrying a 15q11.2-q13.3 maternal duplication, we find significant global DNA hypomethylation that is enriched over autism candidate genes and impacts gene expression. The cumulative effect of multiple chromosomal duplications and exposure to the pervasive persistent organic pollutant PCB 95 altered methylation of >1,000 genes. Hypomethylated genes were enriched for H2A.Z, increased maternal UBE3A in Dup15q corresponded to reduced levels of RING1B, and bivalently modified H2A.Z was altered by PCB 95 and duplication. These results demonstrate the compounding effects of genetic and environmental insults on the neuronal methylome that converge upon dysregulation of chromatin and synaptic genes.

Keywords: autism, copy number variants, persistent organic pollutants, epigenetic, DNA methylation, chromatin, gene x environment interaction

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Characterized by reduced social interaction, impaired communication, and repetitive behaviors, autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are currently estimated to affect 1 in 68 children (2014). The etiology of ASD is complex, involving interactions between multiple genetic and environmental risk factors (Bourgeron, 2015; Hallmayer et al., 2011; Krumm et al., 2014). While there is a strong genetic component to ASD risk, any single copy number variant (CNV) or gene mutation is observed in at most 1% of ASD. Recent combined CNV and exome sequencing identified single causative mutations in only 11% of simplex ASD cases (Sanders et al., 2015). Over eight hundred autism candidate genes have been curated based on mutation, CNV, or genome-wide association evidence (https://gene.sfari.org/autdb/HG_Statistics.do). Genes with de novo variants in ASD are enriched in pathways involved in chromatin modification, developmental transcription factors, and signal transduction pathways including Wnt, Notch, and TGFβ (De Rubeis et al., 2014; Hormozdiari et al., 2015; Iossifov et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2015). Genes implicated in ASD also overlap with those in cancer in pathways related to cell differentiation, chromatin, and DNA repair functions (Crawley et al., 2016).

Similar to cancer, the etiology of ASD is expected to be complex, and may arise from different combinations of multiple common and rare genetic hits combined with exposure to environmental risk factors. Several in utero environmental exposures, including air pollution, pesticides, and infection, have been shown to modestly increase risk for ASDs (Fang et al., 2015; Kalkbrenner et al., 2014; Keil et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Shelton et al., 2014), but the interaction with genetic risk factors has not been previously explored. Epigenetics is defined as modifications to nucleotides or chromatin that can modify phenotype without changing DNA sequence. Epigenetic marks such as DNA methylation (Lister et al., 2013) and histone modifications (Fagiolini et al., 2009) are at the interface of genetic and environmental interactions during the dynamic process of human brain development and are implicated in the etiology of ASD (Ladd-Acosta et al., 2014; Nardone et al., 2014; Vogel Ciernia and LaSalle, 2016). Interestingly, folate is a major dietary methyl donor for DNA and histone methylation reactions, and use of folic acid-containing prenatal vitamins at conception was protective for ASD, particularly in mothers with the MTHFR TT genotype (Schmidt et al., 2011; Schmidt et al., 2012).

The landscape of DNA methylation is especially dynamic in the earliest stages following fertilization through implantation in mammals. In oocytes, preimplantation embryos, and placenta, the genome-wide methylation landscape is characterized by the presence of partially methylated domains (PMDs), which are large-scale (>100 kb) regions with <70% CpG methylation (Guo et al., 2014; Schroeder et al., 2013; Schroeder et al., 2011; Schultz et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). PMDs are also observed in all transformed human cell lines that have been examined by whole genome methylation and span genes that are transcriptionally silent in that cell type or tissue (Schroeder and LaSalle, 2013). The occurrence of global hypomethylation over PMDs in placenta and preimplantation embryos compared to brain is conserved across mammals (Schroeder et al., 2015). Whether hypomethylation may also occur over early life PMDs in brain as a result of genetic or environmental risk factors has not been previously explored.

The 15q11.2-q12 locus contains genes regulated by parental imprinting, which when deleted on the paternal or maternal allele are responsible for the reciprocal disorders of Prader-Willi (PWS) or Angelman (AS) syndromes, respectively (LaSalle et al., 2015). The reciprocal 15q11.2-q13.3 maternal duplication (Dup15q) is one of the most common CNVs observed in ASD (Chaste et al., 2014; Hogart et al., 2008). Dup15q brain is characterized by increased expression of maternally expressed UBE3A, encoding an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Scoles et al., 2011). How UBE3A overexpression may cause the cognitive, seizure, and ASD phenotypes of Dup15q syndrome is currently unknown.

We previously observed significantly reduced methylation in Dup15q brain samples by analysis of LINE-1 repeats and pyrosequencing. However, the Dup15q postmortem brains also showed a significant association with measured levels of the non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB 95) compared to controls (Mitchell et al., 2012). PCBs are identified as probable environmental risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders, and remain a significant children's health concern because of their inadvertent production by various industrial processes and contamination of indoor air, especially in schools across the United States (Grimm et al., 2015; Herrick et al., 2016; Landrigan et al., 2012; Pessah et al., 2010; Stamou et al., 2013). Additionally, PCB exposures have recently been linked to autistic mannerisms in humans (Nowack et al., 2015).

In this study, we hypothesized a “multi-hit model” of cumulative genetic and environmental impacts on DNA methylation, chromatin, and expression of synaptic genes. Through the use of whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) analysis of human brain complemented with experimental neuronal cell culture models, we identify specific genes with altered methylation in brain and neurons by the cumulative impact of Dup15q, a second chromosomal duplication of 22q arising in hypomethylated Dup15q neurons, and PCB 95 exposure.

Results

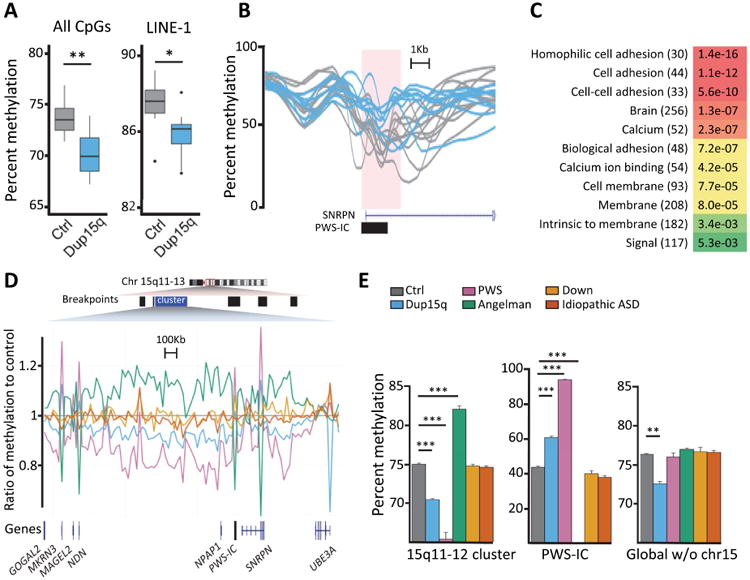

To understand the epigenetic impact of the large CNV in Dup15q syndrome on the brain methylome genome-wide, we performed DNA methylation analysis by WGBS on 41 postmortem human cortical samples including Dup15q, age and sex-matched controls, as well as additional neurodevelopmental disorders as specificity controls (Supp Data 1, Table S1). We found Dup15q samples to be globally hypomethylated compared to controls in both the average methylation across the mappable genome and in LINE-1 repeats (Fig 1A).

Figure 1. Dup15q-specific global DNA hypomethylation and maternal-specific hypomethylation over the imprinted 15q11.2-q12 locus.

A Average methylation of all alignable CpGs (left) and those found in LINE-1 repeats (right) for 11 controls (grey) and 9 Dup15q (blue). B. DMR identified at the PWS-IC showing 9 Dup15q (blue) are hypermethylated compared to 11 controls (grey). C. Gene ontology keyword analysis results of genes associated with DMRs hypomethylated in Dup15q brains compared to controls. Bonferroni corrected p-values with gene numbers in parentheses, colors are determined by p values as shown in the legend to Fig 2D. D. Average methylation of 20 kb windows across hypomethylated cluster. 9 Dup15q (blue), 5 PWS (pink), 3 Angelman (green), 4 Down (gold), and 6 idiopathic ASD (orange) were normalized to 11 control (grey). Parent-of-origin effects on the methylation levels were opposite to the known effects on the smaller loci at the PWS-IC and NDN/MRKN3 promoters (pink/green spikes). Across gene body and intragenic regions, the paternal allele (Angelman has paternal only) was hypermethylated, while the maternal allele (PWS has maternal only, Dup15q has excess maternal) was hypomethylated compared to control. E. Bar graph and statistical analyses of the data shown in D for the 3 Mb 15q11.2-q12 cluster (left), the 4.2kb PWS-IC (middle) and the entire mappable genome excluding chromosome 15 (right). Separate from the parental methylation effects within 15q11.2-q12, global hypomethylation was specifically observed in Dup15q syndrome. Results from 11 control, 9 Dup15q, 5 PWS, 3 Angelman, 4 Down, 6 idiopathic ASD brain samples (details in Supp Data 1, Table S1). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by two-way ANOVA, only showing statistical comparisons to control brain. See also Fig S1 and statistics for multiple comparisons in Supp Data 1, Table S5.

Imprinted gene expression within 15q11.2-13.3 is controlled by the PWS imprinting control region (PWS-IC) (Sutcliffe et al., 1994). A search for small (<3 kb) differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between Dup15q and control brain samples identified 2,575 loci associating with 975 genes (Supp Data 1, Tables S2-S3), including a hypermethylated PWS-IC in Dup15q samples with maternal copy bias, as expected (Fig 1B). A gene ontology (GO) search of the 628 genes within 5 kb of hypomethylated DMRs revealed enrichment for brain, cell adhesion, and calcium binding (Fig 1C and Supp Data 1, Table S4). A second bioinformatic analysis of large 20 kb windows revealed a significant cluster of hypomethylated windows spanning 15q11-12 in Dup15q samples (Fig 1D). Prader-Willi (PWS) samples were included from individuals with maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) or paternal 15q11.2-q13.3 deletion, while Angelman (AS) samples have maternal 15q11.2-q13.3 deletions. Interestingly, methylation levels over the entire 3 Mb 15q11-q12 imprinted locus were directionally opposite from the PWS-IC. PWS brains with only maternal copies of the locus showed the lowest levels of methylation, followed by Dup15q samples with one paternal and 2-5 maternal copies. This is an unexpected result for an imprinted locus in brain but similar to what has been observed on the inactive X chromosome, where only promoter CpG islands are hypermethylated within the hypomethylated and heterochromatic state of the Barr body (Hellman and Chess, 2007), as well as the pattern observed from methylation array data in blood (Joshi et al., 2016). The maternally expressed gene UBE3A escapes this regional hypomethylation, as the UBE3A gene body showed high methylation and low CpG island promoter methylation in all brain samples (Fig S1A).

We then investigated if the hypomethylation observed in Dup15q brain samples was dependent on the chromosome 15 imprinting effects and specific to Dup15q compared to related neurodevelopmental disorders. As a control for any supernumerary chromosome of similar size as the isodicentric chromosome 15, Down (DS) syndrome samples containing trisomy 21 were included. As a control for ASD without detectable CNVs, “idiopathic” ASD samples were compared. When chromosome 15 was excluded from the calculation of average mappable genomic methylation levels, significant global DNA hypomethylation compared to controls was observed specifically in brain samples from Dup15q, but not AS, PWS, DS, or idiopathic ASD (Fig 1E and Supp Data 1, Table S5). Every chromosome (except Y) was significantly hypomethylated in Dup15q with more windows hypomethylated (5,488) than hypermethylated (3,662), a result not confounded by brain region or sex (Fig S1B-C and Supp Data 1, Tables S6-S7). These results demonstrate that the hypomethylation in Dup15q brain extends to thousands of genomic regions outside the duplicated imprinted locus.

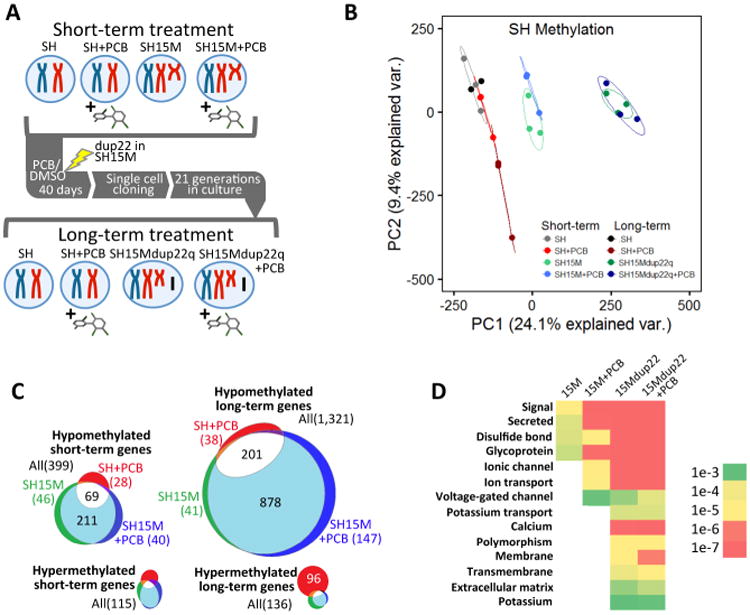

To experimentally test the relevance of a previously observed association between Dup15q and PCB 95 in brain (Mitchell et al., 2012), we cultured a human neuronal Dup15q cell model (SH15M) (Meguro-Horike et al., 2011) and the parental SH-SY5Y (SH) cell line in the presence and absence of PCB 95 for short and long-term periods (Fig 2A). Using read counts from WGBS DNA methylation analysis we confirmed the engineered duplication over 15q11-q14 in SH15M and discovered the de novo introduction of a second CNV at 22q12.3-q13.33 acquired in all long-term SH15M clones (SH15Mdup22q) (Fig 2A and Fig S2A-B). Long-term cultures exhibited significantly lower global DNA methylation levels associated with duplications (Fig S2C and Supp Data 1, Table S8). Principal components analysis (PCA) of 20 kb windows of percent methylation of each replicate and cell type demonstrated clear separations of SH methylomes by duplication genotype with a secondary more subtle separation by long-term PCB 95 effect (dark red) and SH cells (Fig 2B). A nonsignificant trend for hypomethylation with PCB 95 treatment (Fig S2C) was observed as expected, based on previous work in human exposures (Kim et al., 2010; Rusiecki et al., 2008).

Figure 2. Dup15q model reveals compounding multi-hit effects on DNA methylation levels over genes enriched for synaptic functions.

A Experimental design for multi-hit models, including exposure to PCB 95 for either short-term (1 μM for 10 days) or long-term (1 μM for 40 days, followed by single cell cloning) treatment. During the long-term culture of SH15M cells, a spontaneous new duplication arose at 22q12.3-q13.33 and was observed in all clones (SH15Mdup22q). B. Principal components analysis of DNA methylation levels over 20 kb windows for each of the replicate samples of each of the 8 culture conditions shown in A. n = 2 for long-term SH culture and n=3 for all other treatments. The highest two principal components (PC1 and PC2) serve as a proxy for how similar each point representing each replicate (same colors) or cell type or condition (different colors) is to each other. C. Venn diagrams of differentially methylated genes for culture conditions shown in A-B, normalized to parental SH. Significant overlap in genes hypomethylated independently by PCB 95 or 15M compared to SH controls was observed compared to random chance by Fisher's exact test (p<1e-10). D. Gene ontology keyword analysis of hypomethylated genes from C, ordered as “one-hit” (15M), “two-hit” (15M+PCB or 15Mdup22q), or “three-hit” (15Mdup22q+PCB), with heat map of Bonferroni corrected p values (color gradation as in Fig 1C). Keywords common to synaptic genes were observed for all SH15M treatments, but significance was enriched with PCB 95 exposure and compounded by second and third genetic and environmental hits. See also Fig S2.

SH cells have been previously described to contain large genomic regions of hypomethylation called partially methylated domains (PMDs), that cover 20% of the genome and are distinct from PMDs in fibroblasts and placenta (Schroeder et al., 2013; Schroeder et al., 2011). We therefore used a hidden Markov model (HMM) previously described to map PMDs in WGBS data and compared the eight conditions for effects due to maternal 15q duplication, PCB 95 exposure, and/or 22q duplication. We observed a significant increase of PMD coverage in SH15M and SH15Mdup22q compared to parental SH cells, consistent with hypomethylation across every autosome (Fig S2D-E). We then identified the PMDs that were either gained (hypomethylated) or lost (hypermethylated) when compared to the parental SH PMDs (Supp Data 1, Table S9). Genes within the hypomethylated PMDs outnumbered those in hypermethylated PMDs for all conditions, especially for cumulative chromosomal duplications in long-term cultures (Fig 2C). Interestingly, 65% of the genes hypomethylated with PCB 95 exposure alone were in common with those hypomethylated with 15M duplication alone, and 15% of genes hypomethylated with the combination of PCB 95 and 15M duplication were unique to this compounding effect. Gene ontology analysis of genes hypomethylated in SH15M revealed significant enrichment for functions at the synapse membrane, post-synaptic membrane, and secreted factors (Fig 2D and Supp Data 1, Table S10). These categories persisted and increased in significance for functions in ion transport categories with each cumulative effect of 15M, dup22q, and PCB 95 and include two GO categories also observed in brain DMR analyses, “calcium” and “membrane”.

A subset of 83 genes significantly overlapped with the 942 genes identified from Dup15q brain by DMR analysis and the 1605 identified by PMD analysis in neuronal culture models (Pearson's χ2 test for independency with Yates' continuity correction, χ2=35.131, df=1, p= 3.082e-09 for all genes identified from neuronal culture PMDs, separate category comparisons analyzed by Fisher's exact test are in Supp Data 1, Table S11). Table 1 describes the differentially methylated genes that replicated in both systems and approaches, organized by functional categories, including voltage-gated ion channels, modulators of developmental signal transduction pathways, transmembrane proteins involved in ion transport or cell adhesion, transcription factors, regulators on neuronal migration and synapses, as well as others. In addition, 19 of the 83 common differentially methylated genes overlapped noncoding RNAs of unknown function (Table 1).

Table 1. Differentially methylated genes in common between Dup15q brain (DMR) and cell culture models of Dup15q (PMD).

| Gene | Described functions of genes overlapping between brain and neuronal culture differentially methylated |

|---|---|

| Voltage-gated ion channels | |

| CACNA2D3 | Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Auxiliary Subunit Alpha2delta 3; regulates calcium current density and activation/inactivation kinetics of the calcium channel |

| SCN2B | Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Beta Subunit 2; beta 2 subunit of the type II voltage-gated sodium channel; responsible for action potential initiation and propagation in neurons and other excitable cells |

| KCNA2 | Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily A Member 2; voltage-gated ion channel that mediates transmembrane potassium transport to regulate neuronal excitability; mutations cause early-onset epileptic encephalopathy |

| KCNJ9 | Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily J Member 9; G-protein activated inward rectifier potassium channel activity |

| Modulators of developmental signal transduction pathways | |

| ANGPT4 | Angiopoietin 4; promotes endothelial cell survival, migration, and angiogenesis through receptor tyrosine kinase binding |

| C8orf4 | Chromosome 8 Open Reading Frame 4; small monomeric protein and positive regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and beta-catenin mediated transcription at nuclear speckles |

| EVC | EvC Ciliary Complex Subunit 1, acts as a positive modulator of Hedgehog signaling, mutated in Ellis-Van Creveld syndrome |

| NBEA | Neurobeachin; binds to type II regulatory subunits of protein kinase A and targets or anchors them to the membrane |

| PEBP4 | Phosphatidylethanolamine Binding Protein 4; promotes cellular resistance to TNF-induced apoptosis by inhibiting Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway |

| Transmembrane transporters and exchange factors | |

| KNDC1 | Kinase Non-Catalytic C-Lobe Domain (KIND) Containing 1; putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| SLC24A3 | Solute Carrier Family 24 (Sodium/Potassium/Calcium Exchanger), Member 3; transmembrane sodium/calcium exchanger important in maintaining intracellular calcium homeostasis and electrical conduction |

| SLC37A1 | Solute Carrier Family 37 (Glucose-6-Phosphate Transporter), Member 1; endoplasmic reticulum membrane prtotein that translocates glucose-6-phosphate from the cytoplasm to lumen of the ER for hydrolysis into glucose |

| SLC9A3R1 | Solute Carrier Family 9, Subfamily A (NHE3, Cation Proton Antiporter 3), Member 3 Regulator 1; sodium/hydrogen exchanger regulatory cofactor; interacts with and regulates G-protein couple receptors such as beta2-adrenergic receptor |

| ATP10A | ATPase Phospholipid Transporting 10A; P-type cation transport ATPase in Angelman syndrome locus, variably imprinted gene from 15q11-13 locus |

| Cell adhesion, cell-cell junctions | |

| CTNNA3 | Catenin Alpha 3; a member of the vinculin/alpha-catenin family of cell adhesion molecules |

| FRMPD2 | FERM And PDZ Domain Containing 2; membrane protein with putative functions in cell polarization and the regulation of tight junction formation |

| GPA33 | Glycoprotein A33; transmembrane glycoprotein with putative functions in cell-cell recognition and signaling |

| NTM | Neurotrimin; Ig domain-containing GPI-anchored cell adhesion molecule; may promote neurite outgrowth and adhesion; closely related to OPCML |

| OPCML | Opioid Binding Protein/Cell Adhesion Molecule-Like; Ig domain-containing GPI-anchored cell adhesion molecule |

| THBS2 | Thrombospondin 2; glycoprotein mediating cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions; predicted functions in angiogenesis and cell migration |

| Other G-protein coupled receptors | |

| GPR149 | G Protein-Coupled Receptor 149; predicted G-protein coupled receptor activity and neuropeptide binding |

| HRH2 | Histamine Receptor H2; G-protein coupled receptor involved in the suppressive activities of histamines, expressed in both the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system |

| PROKR2 | Prokineticin Receptor 2; integral membrane protein and G-protein coupled receptor for prokineticin; activation leads to calcium mobilization, phosphoinositide turnover, and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| Other transmembrane receptors | |

| SNTG2 | Syntrophin Gamma 2; cytoplasmic peripheral membrane protein that binds to components of mechanosensitive sodium channels and the extreme carboxy-terminal domain of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins. Associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. |

| SORCS2 | Sortilin Related VPS10 Domain Containing Receptor 2; transmembrane protein strongly expressed in the CNS; putative neuropeptide receptor activity |

| Transcription factors | |

| HSF5 | Heat Shock Transcription Factor 5; putative transcription factor activity |

| NPAS1 | Neuronal PAS Domain Protein 1; bHLH-PAS transcription factor with neuronal functions in late central nervous system development |

| MNT | MAX Network Transcriptional Repressor; bHLHzip transcription factor which binds to E box following heterodimerization with Max proteins; putative transcriptional repressor and antagonist of Myc-dependent activation and cell growth |

| PKNOX2 | PBX/Knotted 1 Homeobox 2; homeodomain protein and transcription factor |

| RUNX1 | Runt Related Transcription Factor 1; encodes the alpha subunit of the core binding factor (CBF) heterodimeric transcription factor involved in hematopoesis |

| Protein degradation | |

| HTRA1 | High-Temperature Requirement A Serine Peptidase 1; serine protein protease with a variety of targets, including TSC2 and IGF-binding proteins, putative function in regulating cell growth |

| ASB18 | Ankyrin Repeat and SOCS Box Containing 18; putative substrate-recognition component of a Elongin-Cullin-SOCS-box E3 ubiquitin ligase complex which mediates protein degradation |

| PREP | Prolyl Endopeptidase; cytosolic protein that cleaves prolyl residues; involved in the maturation and degradation of petide hormones and neuropeptides |

| Regulation of neuronal synapses and/or neuronal migration | |

| C1QL2 | Complement Component 1, Q Subcomponent-Like 2; may regulate number of excitatory synapses formed on hippocampal neurons |

| NAV2 | Neuron Navigator 2; helicase and endonuclease involved in neuronal development, may play a role in cellular growth and neuronal migration |

| NTN1 | Netrin 1; laminin-related secreted protein with predicted functions in axon guidance and cell migration in development |

| RIMS1 | Regulating Synaptic Membrane Exocytosis 1; RAS superfamily member and Rab effector that regulates synaptic vesicle exocytosis; essential for maintaining normal probability of neurotransmitter release |

| SYNDIG1 | Synapse Differentiation Inducing 1; transmembrane protein with predicted function in regulating AMPA receptor content at nascent synapses; involved in postsynaptic development and maturation |

| SEMA6B | Semaphorin 6B; transmembrane protein involved in axon guidance in peripheral and central nervous system development |

| SHANK2 | SH3 And Multiple Ankyrin Repeat Domains 2; synaptic protein that may function as molecular scaffolds in the postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses; putative function in structural and functional organization of the dendritic spine and synaptic junction |

| RNA splicing and processing | |

| RBFOX3 | RNA Binding Protein, Fox-1 Homolog 3; also NeuN; neuron-specific RNA-binding protein that regulates alternative splicing events |

| SNRNP48 | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U11/U12 Subunit 48; splicing factor with putative function in U12-type 5′ splice site recognition |

| SSU72 | SSU72 Homolog, RNA Polymerase II CTD Phosphatase; catalyzes the dephosphorylation of RNA polymerase II: plays a role in RNA processing and termination |

| DNA repair | |

| CXXC5 | CXXC Finger Protein 5; retinoid-inducible nuclear protein involved in myocyte differentiation and DNA damage-induced p53 activation; mediator of BMP4-mediated modulation of canonical Wnt signalling |

| METTL22 | Methyltransferase Like 22; a non-histone N-lysine methyltransferase; interacts with its substrate Kin17, a protein involved in DNA repair and mRNA processing |

| Mitochondrial | |

| MRPS6 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein S6; nuclear encoded mitochondrial ribosomal protein, aids in protein synthesis with the mitochondria |

| Keratin and keratinocyte functions | |

| KRT81 | Keratin 81; basic protein which heterodimerizes with type 1 keratins to form hair and nails |

| PADI1 | Peptidyl Arginine Deiminase 1, catalyzes the post-translational deamination of proteins such as keratin in the presence of calcium ions |

| PPL | Periplakin; component of epidermal cornified envelope in keratinocytes; interacts with AKT1/PKB protein kinase as putative localization signal |

| FRMD4A | FERM Domain Containing 4A; FERM-domain containing protein involved in epithelial cell polarity |

| Other human disease genes | |

| SH3TC2 | SH3 Domain And Tetratricopeptide Repeats 2; small protein with predicted functions as an adapter or docking factor; mutations cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome |

| VWF | Von Willebrand Factor; promotes adhesion of platelets to sites of vascular injury by forming a molecular bridge; acts as a chaperone for coagulation factor VIII |

| Additional protein coding genes with poorly described functions | |

| ABRACL, ANKRD26P1, CCDC155, CFAP45, CFAP61, FAM189A2, FGD5P1, LINC01552, SEC14L5, TCERG1L, TMEM200C, ZSCAN1 | |

| Additional noncoding genes with poorly described functions | |

| LEF1-AS1, LINC00461, LINC00504, LIPE-AS1, LOC101928295, LOC101928882, LOC101929413, LOC101929488, LOC102724084, LOC255187, LOC283177, LOC285696, LOC389332, LOC399886, LOC646522, LOC729506, MIR4458HG, MIR548AI, PP12613 | |

To determine if the differentially methylated genes overlap with ASD candidate genes, a similar analysis was performed for genes identified in each category of brain or culture system compared to a curated list of 826 ASD genes (Table 2). Significant over-representation of ASD genes was observed in both hypo- and hyper methylated DMR gene lists from brain, as well as hypomethylated PMD gene lists from short-term SH15M and SH15M+PCB cultures as well as long-term PCB and SH15Mdup22q cultures with and without PCB. Genes hypomethylated in short-term SH15M, SH15M+PCB, and all three long-term conditions were also significantly enriched for targets of FDA-approved drugs, including serotonin receptor HTR2A, six GABA receptors, and five glutamate receptors (Supp Data 1, Table S12).

Table 2. Overlap of genes identified by brain DMRs or cell model PMDs with SFARI ASD candidate gene list.

| Tissue | Genotype or treatment | Method | Diff. meth. direction | Total Genes | # Overlap with SFARI (expected) | χ2 p value | SFARI Autism Candidate Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | Dup15q | DMR | Hypo | 628 | 40 (14.3) | 2.59E-10 | ACTN4, ALOX5AP, ASTN2, ATP10A, CACNA2D31*, CNTNAP3*, CTNNA3*, DLGAP3*, DPP4, EP400, FAM92B, GNAS, GPC6, GRID1*, GRIK5*, HDAC4, JARID2, KDM4B, MNT, NAV2*, NBEA, NLGN2*, OXTR, PCDHA2*, PCDHA3*, PCDHA4*, PCDHA5*, PCDHA7*, PCDHA8*, PCDHA9*, PXDN, RAI1, RIMS1*, SHANK21*, SNTG2, ST8SIA2, STYK1, TBR1, THRA |

| Brain | Dup15q | DMR | Hyper | 347 | 23 (7.9) | 6.80E-07 | ACE, ATP10A, CAMTA1, CHRM3*, CSMD1, DAB1, EHMT1, HDAC4, KDM5B1, LAMA1, LZTS2, MAGEL21 MCPH1, MFRP, NCKAP5L, PREX1, PRUNE2, SDC2, SDK1*, SEMA5A, SHANK21*, SNRPN, UBE3C |

| SH, short | PCB | PMD | Hypo | 102 | 6 (2.3) | 0.04381 | ANKS1B, CACNA1E*, HTR2A*, MNT, NPAS2, RIMS1* |

| SH, short | PCB | PMD | Hyper | 40 | 5 (0.9) | 0.000417 | AGMO, CBS, HYDIN, PRODH, TYR |

| SH, short | 15M | PMD | Hypo | 328 | 20 (7.45) | 2.36E-05 | ADAMTS18, ANKS1B, ATP10A, BZRAP1, CACNA1E*, DLGAP1*, DPP6, GABRB3*, GRIN2A*, HTR2A*, HYDIN, NUAK1, PTPRT, SLC25A27, SLCO1B3, SLITRK5, SYNE1*, UBE3A, UTRN, WNT2 |

| SH, short | 15M | PMD | Hyper | 72 | 2 (1.6) | 1 | CBS, NBEA |

| SH, short | 15M+PCB | PMD | Hypo | 323 | 23 (7.3) | 9.91E-08 | ADAMTS18, AGMO, ANKS1B, ATP10A, BZRAP1, CACNA1E*, DPP6, GABRB3*, GRIN2A*, HTR2A*, HYDIN, KCNJ10, NPAS2, NUAK1, PTPRT, RBFOX1, SLC25A27, SLCO1B3, SLITRK5 SYNE1*, UBE3A, UTRN*, WNT2 |

| SH, short | 15M+PCB | PMD | Hyper | 80 | 3 (1.8) | 0.6265 | CBS, NBEA, TYR |

| SH, long | PCB | PMD | Hypo | 255 | 22 (5.8) | 6.67E-10 | ADAMTS18, CACNA1E*, CNR1*, CNTNAP21*, CYP11B1, DSCAM1, GABRB3*, GRIK3*, HTR2A*, KCNQ3*, LRBA, NRXN3, PAH, PTPRT, PVALB, RBFOX1, SLC24A2, SLC25A27, SLITRK5, SNTG2, SRRM4, VIP |

| SH, long | PCB | PMD | Hyper | 105 | 8 (2.4) | 0.001533 | AGMO, CTNNA3, DLGAP1*, FLT1, GRM5*, GUCY1A2, NPAS2, NUAK1 |

| SH, long | 15M, dup22q | PMD | Hypo | 1127 | 63 (25.6) | 8.12E-12 | ABCA10, ADAMTS18, ADRB2, AGMO, ATP10A, BZRAP1, CACNA1E*, CDH8*, CNR1*, CTNNA3*, CYP11B1, DLGAP1*, DNER*, DPP10, DSCAM 1, ERG, FAM135B, GABRB3*, GALNT14, GRIK3*, GRIP11*, GRM1*, HTR2A*, HTR3A*, IL17A, KCNJ10, KCNQ3*, KIRREL3, KIT, LPL, LRP2, MNT, MYO16, NAV2*, NOS1*, NPAS2, NRXN3*, NTRK3, NUAK1, PAH, PLAUR, PRICKLE2*, PRSS38, PTPRT, PVALB, RBFOX1, SHANK21 *, SLC1A2*, SLC24A2, SLC25A27, SLCO1B3, SLITRK5, SNTG2, SNX19*, SRRM4, SYN3*, TGM3, TPH2, TPO, UBE3A, UTRN*, WNT2, ZBTB16 |

| SH, long | 15M, dup22q | PMD | Hyper | 37 | 0 (0.8) | 0.7198 | |

| SH, long | 15M, dup22q+PCB | PMD | Hypo | 1235 | 66 (28.1) | 3.50E-11 | ABCA10, ADAMTS18, ADRB2, AGMO, ATP10A, BZRAP1, CACNA1E*, CACNA2D31*, CDH8*, CNR1*, CTNNA3*, CYP11B1, DLGAP1*, DNER*, DPP10, DSCAM1, ERG, ESRRB, FAM135B, GABRA4*, GABRB1*, GABRB3*, GALNT14, GRIK3*, GRIP11*, GRM1*, HTR2A*, HTR3A*, IL17A, KCNJ10, KCNQ3*, KIRREL3, KIT, LPL, LRP2, MNT, MYO16, NAV2*, NOS1*, NPAS2, NRXN3*, NTRK3, NUAK1, PAH, PLAUR, PRSS38PTPRT, PVALB, RBFOX1, SHANK21*, SLC1A2*, SLC24A2, SLC25A27, SLCO1B3, SLITRK5, SNTG2, SRRM4, SUCLG2, SYN3*, TGM3, TPH2, TPO, UBE3A, UTRN*, WNT2, ZBTB16 |

| SH, long | 15M, dup22q +PCB | PMD | Hyper | 26 | 0 (0.6) | 0.918 |

Underlined genes are common to ASD genes from 823 SFARI curated genes (June 2016update) identified in both brain DMR and SH culture PMDs.

Strong autism candidate gene at SFARI Gene, June 2016 update

genes with localization and/or known functions at neuronal synapses

Significant chi-square p values without warnings for low counts are in italics

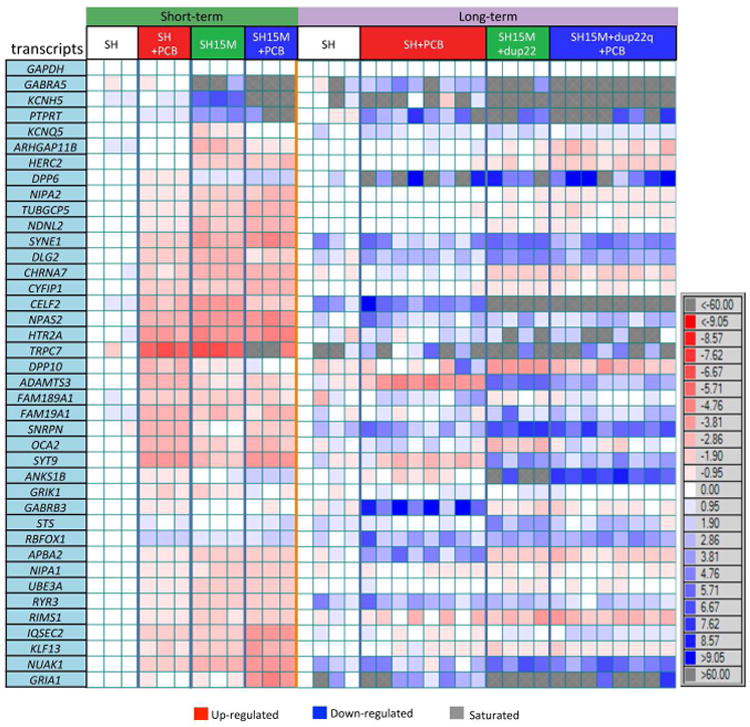

In order to understand the impact of these large-scale methylation changes on expression of genes within the differentially methylated PMDs, we selected 40 hypomethylated genes based on their known roles in ASD, neurotransmission, or location within 15q11-q14 for high-throughput analysis of transcript levels on a Fluidigm BioMark microfluidic qPCR chip (Fig 3). In the short-term cultures, most hypomethylated genes exhibited increased transcript levels in SH+PCB, SH15M, and SH15M+PCB compared to SH, with overlapping effects of either PCB 95 or 15M. In contrast, most transcript levels were reduced or variably expressed in long-term clonal cultures, similar to the variable transcript levels in Dup15q brain samples (Fig S3A) and previously observed (Hogart et al., 2009; Scoles et al., 2011). We validated our expression and methylation results for a subset of genes using qRT-PCR and pyrosequencing (Fig S3B-D). Together these results demonstrate that the hypomethylation and transcriptional instability observed in the SH15M model recapitulate similar observations in postmortem brain and suggest that multiple genetic and environmental hits impact the epigenetic plasticity of synaptic genes enriched for drug targets (Supp Data 1, Table S13).

Figure 3. Short-term increase and long-term decrease of transcript levels in hypomethylated genes observed by multiplex nanofluidic analysis.

Fluidigm Biomark quantitative RT-PCR analysis of 40 transcripts in RNA samples from both short-term and long-term cultures, shown as a heat map for direction and fold-change differences in expression. Each horizontal row reflects a single transcript level relative to GAPDH and each vertical column reflects each individual culture relative to a single SH control culture. Most transcripts of hypomethylated genes were upregulated from control (red) in short-term cultures while downregulated in long-term cultures. Grey boxes reflect fold changes that were saturated (>60.0 or <-60.0 fold change) according to Biomark output that registered CT values as 999.99. See also Fig S3.

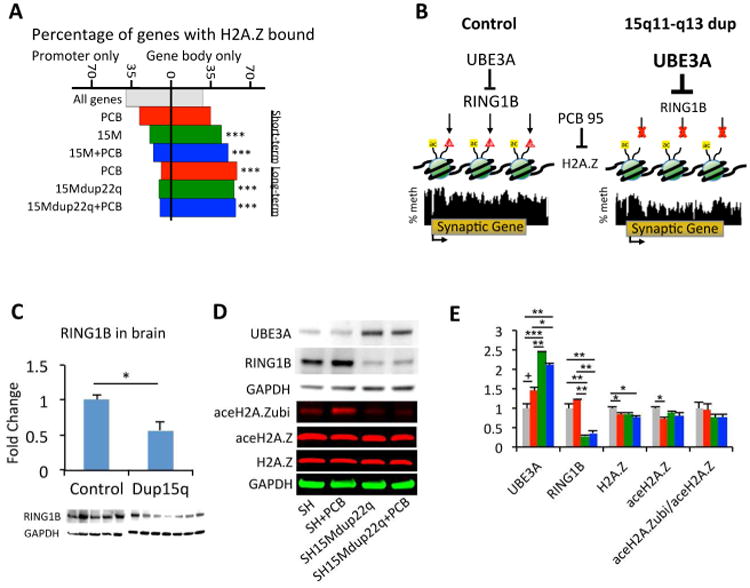

To explore the mechanism by which maternal 15q duplication leads to hypomethylation and transcriptional instability of synaptic genes, we investigated a potential role for the histone variant H2A.Z over gene bodies of synaptic genes, a mark which is both anti-correlated with DNA methylation and associated with inducible gene expression (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). In support of this described relationship between H2A.Z and DNA methylation, the genes identified as hypomethylated in Dup15q and long-term PCB models were significantly enriched for H2A.Z bound at gene body versus promoter locations in neural precursors (Fig 4A and S4A). We then investigated a functional association between the E3 ubiquitin ligase UBE3A and its nuclear target RING1B (Zaaroor-Regev et al., 2010), a component of the PRC1 complex which monoubiquitinates H2A.Z (Ku et al., 2012) (Fig 4B). Bivalent H2A.Z (aceH2A.Zubi) is a mark of destabilized nucleosomes in a repressed but poised transcriptional state, so reduction of H2A.Z monoubiquitin would be consistent with the transcriptional and methylation changes observed in Dup15q brain and multi-hit models (Ku et al., 2012). We show that RING1B protein levels were significantly reduced in Dup15q compared to control brain (Fig 4C). Furthermore, UBE3A levels were significantly higher while RING1B levels were significantly lower in SH15Mdup22q compared to parental SH cells (Fig 4D-E). H2A.Z levels were significantly lower with PCB 95 exposure in both SH and SH15Mdup22q cells, while acetylated H2A.Z levels were reduced with PCB 95 exposure only in parental SH cells (Fig 4E). In contrast, the bivalent form of H2A.Z (aceH2A.Zubi) was not significantly reduced in UBE3A overexpressing cells, although the trend for lower aceH2A.Zubi bivalency associated with higher UBE3A was consistent across experiments and genotypes (Fig 4E and Fig S4B-D, Supp Data 1, Table S14). Together, these results indicate that there are independent and compounding effects on H2A.Z and its posttranslational modifications by three multiple hits of PCB 95 exposure, 15q duplication, and 22q duplication.

Figure 4. . Genes hypomethylated in Dup15q and long-term PCB 95 models are enriched for gene-body H2A.Z, a histone variant which is independently affected by UBE3A and PCB-95.

A Genes identified as hypomethylated in the multi-hit cellular models (gene lists from Supp Data 1, Table S9) were compared by H2A.Z ChIP-seq from human neural precursor cells (GSM807391) for location of H2A.Z binding (Fig S4A). Significant enrichment for gene body H2A.Z was determined by comparing each gene list to all genes by χ2 test of independence, ***p<0.001. B. A proposed functional association between UBE3A, its nuclear target for ubiquitination and degradation RING1B, and monoubiquitination of histone H2A.Z was investigated. Methylation tracks represent merged data from SH and SH15M for SYT9, encoding synaptotagmin IX. C. Quantitation of Western blot of RING1B levels in human brain samples. n=5 control; 7 Dup15q,. *p<0.05 by unpaired t-test. D. Representative Western blots of UBE3A (100 kDa) and RING1B (38 kDa) and 2-color Western blots for bivalent acetylation and ubiquitination of H2A.Z (23 kDa) in SH and SH15M cells with and without short-term PCB 95. The bivalent ubiquitinated and acetylated H2A.Z band (aceH2A.Zubi) was confirmed by an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Fig S4D). E. Quantification of Western blot analyses for protein levels in D in triplicate cultures of cell lines and treatments according to the color code in A (grey SH, red SH+PCB, green SH15M, blue SH15M+PCB). The ratio of bivalent H2A.Z (aceH2A.Zubi) to acetylated H2A.Z was also calculated in triplicate cultures. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by 2-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons, +marginally significant (0.06>p>0.05). Results shown are from short-term culture of the SH15Mdup22q cell line, but similar results were obtained in a short-term SH15M culture without the 22q duplication (Fig S4B-D). See also Figure S4 and statistical tests in Supp Data 1, Table S14

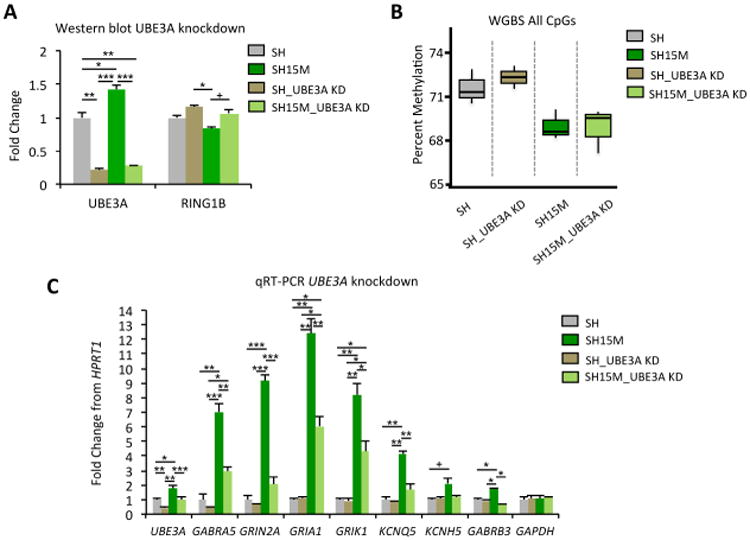

Knockdown of UBE3A protein levels by siRNA corresponded to increased RING1B levels that mirrored similar trend in global DNA methylation levels in SH15M cells (no dup22) to those of parental SH cells, although these trends were not significant (Fig 5A-B). UBE3A siRNA knockdown significantly decreased UBE3A transcript levels in both SH and SH15M cells, as expected, but SH15M cells additionally showed reduced the transcript levels of several synaptic genes (GRIA1, GRIK1, GRIN2A, GABRA5, GABRB3, KCNH5) but not a control gene, GAPDH (Fig 5C). Together these results demonstrate that the increased UBE3A levels in SH15M cells may explain the increased transcriptional plasticity observed for synaptic genes in the SH15M cell culture model and Dup15q syndrome brain through a RING1B and H2A.Z mediated mechanism. Interestingly, correcting UBE3A levels in SH15M cells in the short-term (7 day culture in low serum conditions for siRNA uptake, see extended methods) corrected some synaptic gene transcript levels to parental SH levels (GRIN2A, KCNQ5, GABRB3) without significantly affecting global methylation levels, suggesting that transcriptional changes are more directly affected by UBE3A overexpression than methylation levels, consistent with the model in Fig 4B.

Figure 5. Reduction of UBE3A levels in SH15M cells by siRNA knockdown alters transcriptional levels of synaptic genes.

A. Quantitation of Western blot analysis for UBE3A and RING1B protein levels following siRNA knockdown (KD) of UBE3A levels in SH or SH15M cells (no dup22q), in triplicate. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by 2-way RM ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons, +marginally significant (0.06>p>0.05). B. WGBS global analysis of percent DNA methylation levels (all mappable CpG sites) from cells analyzed in A, in triplicate. C. qRT-PCR analysis using cDNA isolated from the siRNA knockdown experiment in A-B and primers to UBE3A, several synaptic genes, and another housekeeping control (GAPDH). Results are expressed as mean fold-change from HPRT1 housekeeping control of triplicates, error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, +marginally significant (0.06>p>0.05) by 2-way RM ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical tests are shown in Supp Data 1, Table S17.

Discussion

Our analyses of both human brain and experimental models constitutes the largest WGBS study of ASD to date, providing over 5 billion uniquely alignable reads across 41 brain and 23 cell culture samples, analyzed by complementary bioinformatics approaches for identifying differential methylation (summarized in Supp Data 1, Table S15). As a focused investigation on the brain and neuronal DNA methylome, this study provides several important insights into genes, gene pathways, genome stability, and chromatin modulation in the complex etiology of ASD. First, by investigating an interaction between Dup15q syndrome and PCB 95 exposures, we identify differentially methylated genes in common between brain and different experimental models, as well as with genes in common with rare genetic variants observed in ASD. Second, through long-term cloning of Dup15q neuronal cell lines with PCB 95 exposure, we investigated the impact of global hypomethylation on genome instability in the acquisition of a second genetic hit of chromosome 22q duplication on the epigenome. Third, we explore a possible mechanistic connection for maternal UBE3A overexpression and PCB 95 on RING1B and histone H2A.Z epigenetic modifications. Together, these results demonstrate a cumulative effect of large chromosome duplications and PCB 95 exposure on genes with functions at neuronal synapses, transcriptional regulation, and signal transduction pathways.

Both 15q duplication and PCB 95 exposure affected the methylation and transcription of an overlapping set of genes, with a stronger genetic than environmental effect on DNA methylation. However, multiple genes, such as those encoding GABAA receptor subunit GABRB3 and the calcium voltage-gated channel CACNA1E were in common between the independent genetic and environmental effects. Mechanistically, PCB 95 acts to enhance the calcium ryanodine receptors and Wnt pathway signaling, thus promoting dendritic branching in hippocampal neurons (Wayman et al., 2012a; Wayman et al., 2012b). RYR3, a 15q13-14 gene encoding ryanodine receptor 3, was epigenetically and transcriptionally altered by both Dup15q and PCB 95. In addition, our identification of many differentially methylated and expressed genes with functions in voltage-gated ion channels, cell adhesion, signal transduction, and transcriptional regulation and the changes to H2A.Z are relevant to understanding the long-term impacts of PCB exposures on transcriptional stability in neurons. While global DNA hypomethylation associated with PCB exposures has been reported previously in both human samples and animal models (Desaulniers et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010; Rusiecki et al., 2008), ours is unique in performing a genome-wide identification of PCB 95 associated methylation changes and to investigate a genetic interaction.

Multiple hits in the etiology of ASDs may be due to independent or interactive events (Girirajan et al., 2011; Leblond et al., 2012; Pessah et al., 2010; Zuk et al., 2012). Interestingly, DNA hypomethylation has long been implicated in the genome instability observed in tumors and cancer cell lines (Li et al., 2012). Therefore, hypomethylation in the SH15M cells may have contributed to a new CNV on 22q that further compounded the hypomethylation phenotype. This 17.5 Mb 22q duplication contains 295 genes that include the SHANK3 high confidence ASD gene and a cluster of 7 APOBEC3 genes previously implicated in demethylation (Guo et al., 2011). CNVs observed in ASD include smaller 22q duplications generally spanning SHANK3 and ∼20 genes but not the APOBEC3 gene cluster (Han et al., 2013). While this exceptionally large second duplication was likely a result of long-term culture of the hypomethylated SH15M cell line, this event could serve as a model for how somatic gains or losses of copy number may occur in individual neurons within ASD brain (Iourov et al., 2012). The absence of significant global hypomethylation in DS (trisomy 21) observed here is consistent with recent studies showing more subtle methylation changes in the genome (Hatt et al., 2016; Mendioroz et al., 2015) and suggests that not all large CNVs may significantly impact the global methylome. However, due to the large number of genes within the genome that regulate epigenetic mechanisms, the chances of a CNV impacting a regulator of DNA methylation are likely to increase with increased number or size of chromosome duplications. The “idiopathic” ASD brains included for comparison in this study showed no detectable CNVs, but a WGBS study powered with increased sample size in the future could reveal gene locus specific methylation differences in common to ASD even in the absence of global methylation differences such as those observed in Dup15q syndrome.

While the DNA methylome from brain tissue does not exhibit PMDs, the observation that genes identified from brain DMRs significantly overlapped with those found in SH-SY5Y neuronal PMDs and those enriched for gene body H2A.Z suggests that genes in transcriptionally poised states in early life may characterize those that are the most susceptible to methylation and transcriptional instability in response to multiple genetic and environmental factors. In cancer, genes within PMDs are more variable in their expression (Hansen et al., 2011), consistent with the increased variability and plasticity of gene expression observed in our study. UBE3A is also known as human papilloma virus E6-associated protein (E6-AP) that targets p53 for degradation in cervical cancer, and siRNA knockdown of UBE3A in a cancer cell line inhibited proliferation and invasion, and induced apoptosis (Zhou et al., 2015). Similarly, in our UBE3A siRNA knockdown experiments, transcriptional corrections were observed in the SH15M UBE3A overexpressing cells for several synaptic genes without a detectable change in global DNA methylation levels, suggesting that the transcriptional changes may precede hypomethylation changes to the DNA. Together, these results suggest that PMD locations over synaptic genes confer an epigenetic vulnerability to genetic and environmental multi-hits that will be important in interpreting the multiple etiologies implicated in ASD and in identifying existing drugs that could be utilized in therapies for treatment of ASD.

Experimental Procedures

Sample acquisition, DNA isolation, and WGBS library preparation

Human cerebral cortex samples were obtained from the NICHD Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD. SH-SH5Y and SH-SY5Y-15M cells were grown as described (Meguro-Horike et al., 2011) with the addition of 1 μM PCB 95 or DMSO for 10 days (short-term) or 40 days (long term), followed by limited dilution single cell cloning and expansion for 21 generations. DNA was isolated using the Qiagen Puregene kit and WGBS libraries prepared as described (Schroeder et al., 2011). Additional sample preparation methods are in Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Supp Data 1, Table S1.

Bioinformatics

Raw FASTQ files were filtered and trimmed to remove the adapters and 10 bases before the adapters to remove biased hypomethylation contamination at 3′ adapter ends (Hansen et al., 2012). Reads were then aligned to the human genome (hg38) using BS-Seeker2 (Guo et al., 2013). Conversion efficiency was determined by mitochondria DNA (Hong et al., 2013). DMRs were called using the R packages DSS and bsseq and custom R commands (Feng et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2014). Additional bioinformatics methods are in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Molecular methods

Transcript levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR, performed in 48.48 Dynamic Array Integrated Fluidic Circuits (IFC), with EvaGreen detection on the Biomark HD system. Western blots were performed using antibodies and conditions described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. siRNA-mediated knockdown of UBE3A protein was carried out using the Accell SMARTpool (Dharmacon) mixture of four siRNAs according to the manufacturer's protocols. Pyrosequencing analysis of genomic DNA (500 ng) bisulfite converted using Zymo's EZ DNA Methylation-Direct kit ona Pyromark Q24 Pyrosequencer (Qiagen) was performed using the manufacturers recommended protocol and software analysis. Primers used for qRT-PCR and pyrosequencing are in Supp Data 1, Table S16.

Statistical methods

Statistical tests are described in detail in each figure legend, Supp table legends, and supplemental methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01ES021707, NIH R01ES014901, NIH P01ES011269, and EPA 83543201. KD was supported by a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences funded training program in Environmental Health Sciences (T32 ES007059). Some tissue, other biological specimens or data used in this research was obtained from Autism BrainNet that is sponsored by the Simons Foundation and Autism Speaks. The authors also acknowledge the Autism Tissue Program that was the predecessor to Autism BrainNet. This work utilized data from the Epigenomics Roadmap: http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/epigenomics/. This work used the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at UC Berkeley, supported by NIH S10 Instrumentation Grants S10RR029668 and S10RR027303 and Dr. Kyoungmi Kim for statistical assistance through the UC Davis MIND Institute Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center [U54 HD079125].

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JML conceived the study. KD, MSI, DHY, DIS, INP, and JML designed the study. KD, MSI, JL acquired the data. KD, RGC, RLC, AVC, and JML analyzed the data. SH15M cells provided by MH and SH. KD, CM, PL, and IK contributed expertise or analysis tools. KD, MSI, and JML wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Data Access: All sequencing data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession number GSE81541. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries. 2014;63:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T. From the genetic architecture to synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorder. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2015;16:551–563. doi: 10.1038/nrn3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaste P, Sanders SJ, Mohan KN, Klei L, Song Y, Murtha MT, Hus V, Lowe JK, Willsey AJ, Moreno-De-Luca D, et al. Modest impact on risk for autism spectrum disorder of rare copy number variants at 15q11.2, specifically breakpoints 1 to 2. Autism Res. 2014;7:355–362. doi: 10.1002/aur.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Derr D, Zilberman D. DNA methylation, H2A.Z, and the regulation of constitutive expression. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2012;77:147–154. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.77.014944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Heyer WD, LaSalle JM. Autism and Cancer Share Risk Genes, Pathways, and Drug Targets. Trends Genet. 2016;32:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, Kou Y, Liu L, Fromer M, Walker S, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaulniers D, Xiao GH, Lian H, Feng YL, Zhu J, Nakai J, Bowers WJ. Effects of mixtures of polychlorinated biphenyls, methylmercury, and organochlorine pesticides on hepatic DNA methylation in prepubertal female Sprague-Dawley rats. Int J Toxicol. 2009;28:294–307. doi: 10.1177/1091581809337918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Jensen CL, Champagne FA. Epigenetic influences on brain development and plasticity. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2009;19:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SY, Wang S, Huang N, Yeh HH, Chen CY. Prenatal Infection and Autism Spectrum Disorders in Childhood: A Population-Based Case-Control Study in Taiwan. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29:307–316. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Conneely KN, Wu H. A Bayesian hierarchical model to detect differentially methylated loci from single nucleotide resolution sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girirajan S, Brkanac Z, Coe BP, Baker C, Vives L, Vu TH, Shafer N, Bernier R, Ferrero GB, Silengo M, et al. Relative burden of large CNVs on a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm FA, Hu D, Kania-Korwel I, Lehmler HJ, Ludewig G, Hornbuckle KC, Duffel MW, Bergman A, Robertson LW. Metabolism and metabolites of polychlorinated biphenyls. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2015;45:245–272. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2014.999365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Zhu P, Yan L, Li R, Hu B, Lian Y, Yan J, Ren X, Lin S, Li J, et al. The DNA methylation landscape of human early embryos. Nature. 2014;511:606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature13544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Su Y, Zhong C, Ming GL, Song H. Hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine by TET1 promotes active DNA demethylation in the adult brain. Cell. 2011;145:423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Fiziev P, Yan W, Cokus S, Sun X, Zhang MQ, Chen PY, Pellegrini M. BS-Seeker2: a versatile aligning pipeline for bisulfite sequencing data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:774. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, Miller J, Fedele A, Collins J, Smith K, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68:1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K, Holder JL, Jr, Schaaf CP, Lu H, Chen H, Kang H, Tang J, Wu Z, Hao S, Cheung SW, et al. SHANK3 overexpression causes manic-like behaviour with unique pharmacogenetic properties. Nature. 2013;503:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KD, Langmead B, Irizarry RA. BSmooth: from whole genome bisulfite sequencing reads to differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R83. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KD, Sabunciyan S, Langmead B, Nagy N, Curley R, Klein G, Klein E, Salamon D, Feinberg AP. Large-scale hypomethylated blocks associated with Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell immortalization. Genome Research. 2014;24:177–184. doi: 10.1101/gr.157743.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KD, Timp W, Bravo HC, Sabunciyan S, Langmead B, McDonald OG, Wen B, Wu H, Liu Y, Diep D, et al. Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:768–775. doi: 10.1038/ng.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatt L, Aagaard MM, Bach C, Graakjaer J, Sommer S, Agerholm IE, Kolvraa S, Bojesen A. Microarray-Based Analysis of Methylation of 1st Trimester Trisomic Placentas from Down Syndrome, Edwards Syndrome and Patau Syndrome. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman A, Chess A. Gene body-specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science. 2007;315:1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1136352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick RF, Stewart JH, Allen JG. Review of PCBs in US schools: a brief history, an estimate of the number of impacted schools, and an approach for evaluating indoor air samples. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:1975–1985. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogart A, Leung KN, Wang NJ, Wu DJ, Driscoll J, Vallero RO, Schanen NC, LaSalle JM. Chromosome 15q11-13 duplication syndrome brain reveals epigenetic alterations in gene expression not predicted from copy number. J Med Genet. 2009;46:86–93. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogart A, Wu D, Lasalle JM, Schanen NC. The comorbidity of autism with the genomic disorders of chromosome 15q11.2-q13. Neurobiol Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EE, Okitsu CY, Smith AD, Hsieh CL. Regionally specific and genome-wide analyses conclusively demonstrate the absence of CpG methylation in human mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2683–2690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00220-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormozdiari F, Penn O, Borenstein E, Eichler EE. The discovery of integrated gene networks for autism and related disorders. Genome Research. 2015;25:142–154. doi: 10.1101/gr.178855.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov I, O'Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, Stessman HA, Witherspoon KT, Vives L, Patterson KE, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Single cell genomics of the brain: focus on neuronal diversity and neuropsychiatric diseases. Curr Genomics. 2012;13:477–488. doi: 10.2174/138920212802510439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi RS, Garg P, Zaitlen N, Lappalainen T, Watson CT, Azam N, Ho D, Li X, Antonarakis SE, Brunner HG, et al. DNA Methylation Profiling of Uniparental Disomy Subjects Provides a Map of Parental Epigenetic Bias in the Human Genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner AE, Schmidt RJ, Penlesky AC. Environmental chemical exposures and autism spectrum disorders: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44:277–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil AP, Daniels JL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Autism spectrum disorder, flea and tick medication, and adjustments for exposure misclassification: the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) case-control study. Environmental health : a global access science source. 2014;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, Kim DS, Lee SK, Lee IK, Kang JH, Chang YS, Jacobs DR, Steffes M, Lee DH. Association of low-dose exposure to persistent organic pollutants with global DNA hypomethylation in healthy Koreans. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:370–374. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N, O'Roak BJ, Shendure J, Eichler EE. A de novo convergence of autism genetics and molecular neuroscience. Trends in neurosciences. 2014;37:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku M, Jaffe JD, Koche RP, Rheinbay E, Endoh M, Koseki H, Carr SA, Bernstein BE. H2A.Z landscapes and dual modifications in pluripotent and multipotent stem cells underlie complex genome regulatory functions. Genome biology. 2012;13:R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd-Acosta C, Hansen KD, Briem E, Fallin MD, Kaufmann WE, Feinberg AP. Common DNA methylation alterations in multiple brain regions in autism. Molecular psychiatry. 2014;19:862–871. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan PJ, Lambertini L, Birnbaum LS. A research strategy to discover the environmental causes of autism and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Environmental health perspectives. 2012;120:a258–260. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSalle JM, Reiter LT, Chamberlain SJ. Epigenetic regulation of UBE3A and roles in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics. 2015 doi: 10.2217/epi.15.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond CS, Heinrich J, Delorme R, Proepper C, Betancur C, Huguet G, Konyukh M, Chaste P, Ey E, Rastam M, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8:e1002521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BK, Magnusson C, Gardner RM, Blomstrom A, Newschaffer CJ, Burstyn I, Karlsson H, Dalman C. Maternal hospitalization with infection during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;44:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Harris RA, Cheung SW, Coarfa C, Jeong M, Goodell MA, White LD, Patel A, Kang SH, Shaw C, et al. Genomic hypomethylation in the human germline associates with selective structural mutability in the human genome. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, Urich M, Puddifoot CA, Johnson ND, Lucero J, Huang Y, Dwork AJ, Schultz MD, et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science. 2013;341:1237905. doi: 10.1126/science.1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro-Horike M, Yasui DH, Powell W, Schroeder DI, Oshimura M, Lasalle JM, Horike S. Neuron-specific impairment of inter-chromosomal pairing and transcription in a novel model of human 15q-duplication syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20:3798–3810. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendioroz M, Do C, Jiang X, Liu C, Darbary HK, Lang CF, Lin J, Thomas A, Abu-Amero S, Stanier P, et al. Trans effects of chromosome aneuploidies on DNA methylation patterns in human Down syndrome and mouse models. Genome Biol. 2015;16:263. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0827-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MM, Woods R, Chi LH, Schmidt RJ, Pessah IN, Kostyniak PJ, LaSalle JM. Levels of select PCB and PBDE congeners in human postmortem brain reveal possible environmental involvement in 15q11-q13 duplication autism spectrum disorder. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 2012;53:589–598. doi: 10.1002/em.21722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardone S, Sams DS, Reuveni E, Getselter D, Oron O, Karpuj M, Elliott E. DNA methylation analysis of the autistic brain reveals multiple dysregulated biological pathways. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e433. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack N, Wittsiepe J, Kasper-Sonnenberg M, Wilhelm M, Scholmerich A. Influence of Low-Level Prenatal Exposure to PCDD/Fs and PCBs on Empathizing, Systemizing and Autistic Traits: Results from the Duisburg Birth Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah IN, Cherednichenko G, Lein PJ. Minding the calcium store: Ryanodine receptor activation as a convergent mechanism of PCB toxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:260–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusiecki JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V, Tarantini L, Moore LE, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC. Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with high serum-persistent organic pollutants in Greenlandic Inuit. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1547–1552. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SJ, He X, Willsey AJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Samocha KE, Cicek AE, Murtha MT, Bal VH, Bishop SL, Dong S, et al. Insights into Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Architecture and Biology from 71 Risk Loci. Neuron. 2015;87:1215–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RJ, Hansen RL, Hartiala J, Allayee H, Schmidt LC, Tancredi DJ, Tassone F, Hertz-Picciotto I. Prenatal vitamins, one-carbon metabolism gene variants, and risk for autism. Epidemiology. 2011;22:476–485. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821d0e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RJ, Tancredi DJ, Ozonoff S, Hansen RL, Hartiala J, Allayee H, Schmidt LC, Tassone F, Hertz-Picciotto I. Maternal periconceptional folic acid intake and risk of autism spectrum disorders and developmental delay in the CHARGE (CHildhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) case-control study. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;96:80–89. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder DI, Blair JD, Lott P, Yu HO, Hong D, Crary F, Ashwood P, Walker C, Korf I, Robinson WP, et al. The human placenta methylome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:6037–6042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215145110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder DI, Jayashankar K, Douglas KC, Thirkill TL, York D, Dickinson PJ, Williams LE, Samollow PB, Ross PJ, Bannasch DL, et al. Early Developmental and Evolutionary Origins of Gene Body DNA Methylation Patterns in Mammalian Placentas. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder DI, LaSalle JM. How has the study of the human placenta aided our understanding of partially methylated genes? Epigenomics. 2013;5:645–654. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder DI, Lott P, Korf I, LaSalle JM. Large-scale methylation domains mark a functional subset of neuronally expressed genes. Genome Research. 2011;21:1583–1591. doi: 10.1101/gr.119131.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz MD, He Y, Whitaker JW, Hariharan M, Mukamel EA, Leung D, Rajagopal N, Nery JR, Urich MA, Chen H, et al. Human body epigenome maps reveal noncanonical DNA methylation variation. Nature. 2015;523:212–216. doi: 10.1038/nature14465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles HA, Urraca N, Chadwick SW, Reiter LT, Lasalle JM. Increased copy number for methylated maternal 15q duplications leads to changes in gene and protein expression in human cortical samples. Mol Autism. 2011;2:19. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, Delwiche LD, Schmidt RJ, Ritz B, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environmental health perspectives. 2014;122:1103–1109. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamou M, Streifel KM, Goines PE, Lein PJ. Neuronal connectivity as a convergent target of gene x environment interactions that confer risk for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013;36:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe JS, Nakao M, Christian S, Orstavik KH, Tommerup N, Ledbetter DH, Beaudet AL. Deletions of a differentially methylated CpG island at the SNRPN gene define a putative imprinting control region. Nat Genet. 1994;8:52–58. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Ciernia A, LaSalle JM. The landscape of DNA methylation amid a perfect storm of autism aetiologies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:411–423. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman GA, Bose DD, Yang D, Lesiak A, Bruun D, Impey S, Ledoux V, Pessah IN, Lein PJ. PCB-95 modulates the calcium-dependent signaling pathway responsible for activity-dependent dendritic growth. Environ Health Perspect. 2012a;120:1003–1009. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman GA, Yang D, Bose DD, Lesiak A, Ledoux V, Bruun D, Pessah IN, Lein PJ. PCB-95 promotes dendritic growth via ryanodine receptor-dependent mechanisms. Environ Health Perspect. 2012b;120:997–1002. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaroor-Regev D, de Bie P, Scheffner M, Noy T, Shemer R, Heled M, Stein I, Pikarsky E, Ciechanover A. Regulation of the polycomb protein Ring1B by self-ubiquitination or by E6-AP may have implications to the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003108107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Zheng H, Huang B, Li W, Xiang Y, Peng X, Ming J, Wu X, Zhang Y, Xu Q, et al. Allelic reprogramming of the histone modification H3K4me3 in early mammalian development. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature19361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Deng S, Liu H, Liu Y, Yang Z, Xing T, Jing B, Zhang X. Knockdown of ubiquitin protein ligase E3A affects proliferation and invasion, and induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells through regulation of annexin A2. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:1107–1113. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk O, Hechter E, Sunyaev SR, Lander ES. The mystery of missing heritability: Genetic interactions create phantom heritability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1193–1198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119675109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.