Abstract

The hypothesis that proximity to the Sun causes variation of decay constants at permille level has been tested and disproved. Repeated activity measurements of mono-radionuclide sources were performed over periods from 200 days up to four decades at 14 laboratories across the globe. Residuals from the exponential nuclear decay curves were inspected for annual oscillations. Systematic deviations from a purely exponential decay curve differ from one data set to another and are attributable to instabilities in the instrumentation and measurement conditions. The most stable activity measurements of alpha, beta-minus, electron capture, and beta-plus decaying sources set an upper limit of 0.0006% to 0.008% to the amplitude of annual oscillations in the decay rate. Oscillations in phase with Earth’s orbital distance to the Sun could not be observed within a 10−6 to 10−5 range of precision. There are also no apparent modulations over periods of weeks or months. Consequently, there is no indication of a natural impediment against sub-permille accuracy in half-life determinations, renormalisation of activity to a distant reference date, application of nuclear dating for archaeology, geo- and cosmochronology, nor in establishing the SI unit becquerel and seeking international equivalence of activity standards.

Keywords: Half-life, Decay constant, Uncertainty, Radioactivity, Sun, Neutrino

1. Introduction

The exponential-decay law is one of the most famous laws of physics, already carved in stone since the pioneering work of Ernest Rutherford [1], Maria Skłodowska-Curie [2] and others. It has withstood numerous tests [3–5] demonstrating that the decay of a radionuclide can be characterised solely by a single decay constant – or equivalently by the half-life – which is invariable in space and time. However, observations of periodic oscillations in measured decay rates of radioactive sources [6–13] have been heavily debated in the last decade [6–25]. Controversy arose at two levels: (i) at the observational level, with experimental data sets showing significant differences in stability of decay rates with time, and (ii) at the interpretational level, either ascribing the observed modulations to instabilities in the detection system, or advocating new physics to explain variability in the decay constants.

As much as the instability claims attract interest as inspiration for new physical theories and applications [14,15], if true they would have major implications on traceability and equivalence in the common measurement system of radioactive substances. Variability of decay constants at permille level would limit the precision by which a half-life value could be assigned to a radionuclide, as well as the accuracy by which the SI-unit becquerel could be established through primary standardisation [26] and international equivalence demonstrated through key comparisons and the Système International de Référence (SIR) [27]. The implications at metrological level would eventually affect science built on the decay laws, from renormalisation of activity to a reference date for nuclear dosimetry to precise nuclear dating for geo- and cosmochronology.

At the heart of this controversy are the metrological difficulties inherent to the measurement of half-lives [28–30]. From a metrological point of view, it is obvious that instruments, electronics, geometry and background may vary due to external influences such as temperature, pressure, humidity and natural or man-made sources of radioactivity. Claims of variability of half-lives on the basis of deviations from an exponential decay curve can only be considered when the instrumental effects have been fully compensated and/or accounted for in the uncertainty budget. Jenkins et al. [9] claim to have done so before proposing their hypothesis that permille sized seasonal variations of decay rates of 226Ra and 36Cl are caused by solar influences on their decay constants [6–8]. Evidence has been collected to demonstrate instabilities in the decay of other radionuclides [10,11] and by means of time-frequency analysis periodicity at shorter and longer term than 1 year have been claimed [11–13]. However, this interpretation is being challenged by the publication of data sets confirming a close adherence to exponential decay with residuals in the 10−5 range [16,18,20,21,23].

Authors of both convictions expressed the need for collecting evidence for different radionuclides measured with different detection techniques [7,11,13,18,23]. At national metrology institutes (NMIs) taking responsibility for establishing the unit becquerel, mono-radionuclide sources are kept and regularly measured for standardisation purposes as well as for determining half-lives. In addition, gamma-ray spectrometry laboratories keep records of quality control measurements on their spectrometers which provide useful information on long-term trends in activity measurements of a reference source. In this work, the hypothesis that decay constants vary through solar influence in phase with Earth–Sun orbital distance has been tested through the analysis of a unique collection of activity measurements repeated over periods of 200 days up to four decades at 14 laboratories distributed across the globe.

2. Measurements & analysis

Precise activity measurement series were performed for alpha decay (209Po, 226Ra series, 228Th, 230U, 241Am), beta minus decay (3H, 14C, 60Co, 85Kr, 90Sr, 124Sb, 134Cs, 137Cs), electron capture (54Mn, 55Fe, 57Co, 82,85Sr, 109Cd, 133Ba), a mixture of electron capture and positron decay (22Na, 65Zn, 207Bi), and a mixture of electron capture and beta minus/plus decay (152Eu). More than 60 data sets were collected, some of which were performed over several decades. Some data sets excel in precision, others reveal vulnerability of different measurement techniques to external conditions. Characteristics of the data sets are summarised in Table 1.

Table1.

Characteristics of the decay rate measurement sets analysed. The method acronyms are explained in the text. The period indicates the first and last year in which data were collected. The standard deviation is an indication of the uncertainty on the annual averaged data (maximum 46 data, covering 8-day periods), derived from the spread of the input data and the inverse square root of the number of values in each data group. The amplitude and phase are the result of the fit of a sinusoidal function to the averaged data. In bold are the amplitudes at 10−6–10−5 level. The estimated standard uncertainty on the amplitude is indicated between parentheses, its order of magnitude corresponding to that of the last digit of the value of A.

| Decay mode(s) |

Nuclide | Laboratory | Method | Period (year) |

#Data | Rel. std dev in % |

Amplitude A in % |

Phase shift α in days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 209Po | JRC | PIPS | 2013–2016 | 1539 | 0.024 | 0.006 (5) | 6 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | PTB | IC | 1983–1998 | 1973 | 0.011 | 0.083 (2) | 59 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | PTB | IC | 1999–2016 | 2184 | 0.005 | 0.016 (1) | 194 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | ENEA | IC | 1992–2015 | 161 | 0.025 | 0.043 (5) | 324 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | NIST | IC #1 | 2008–2016 | 99 | 0.016 | 0.015 (3) | 255 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | NIST | IC #2 | 2012–2016 | 272 | 0.036 | 0.002 (8) | 8 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | BIPM | IC | 2001–2015 | 136 | 0.015 | 0.004 (3) | 4 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | JRC | IC | 2005–2015 | 1737 | 0.005 | 0.003 (2) | 363 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | NPL | IC #1 | 1993–2016 | 4055 | 0.014 | 0.0025 (18) | 60 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | NPL | IC #2 | 1993–2016 | 3996 | 0.005 | 0.005 (1) | 73 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | NMISA | IC | 1992–2015 | 276 | 0.343 | 0.106 (60) | 67 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | ANSTO | IC | 2012–2015 | 700 | 0.015 | 0.005 (3) | 256 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | ANSTO | HIC | 2008–2014 | 1749 | 0.077 | 0.009 (18) | 82 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | LNHB | IC #1 | 1998–2016 | 455 | 0.026 | 0.026 (6) | 328 |

| α + β− | 226Ra | LNHB | IC #2 | 1998–2016 | 498 | 0.028 | 0.042 (7) | 294 |

| α | 228Th | NIST | IC | 1968–1978 | 70 | 0.107 | 0.031 (22) | 327 |

| α | 230U | JRC | αDSA, PIPS, CsI, LSC, HPGe | 2010–2011 | 5451 | 0.083 | 0.007 (7) | 173 |

| α | 241Am | JRC | PC | 2004–2008 | 245 | 0.022 | 0.101 (16) | 104 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #8 | 2008–2016 | 430 | 0.13 | 0.024 (28) | 55 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #26 | 2013–2016 | 166 | 0.12 | 0.002 (23) | 304 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #11 | 2008–2016 | 402 | 0.12 | 0.055 (22) | 242 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #16 | 2008–2016 | 382 | 0.13 | 0.079 (26) | 290 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #25 | 2011–2016 | 245 | 0.12 | 0.079 (22) | 236 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #10 | 2008–2016 | 466 | 0.14 | 0.115 (27) | 259 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #27 | 2011–2015 | 238 | 0.45 | 0.095 (91) | 280 |

| α | 241Am | SCK | HPGe #13 | 2008–2016 | 434 | 0.12 | 0.167 (26) | 235 |

| α | 241Am | PTB | LSC | 2014–2016 | 574 | 0.004 | 0.0006 (7) | 260 |

| β− | 3H | JRC | LSC | 2002–2014 | 706 | 0.112 | 0.048 (24) | 197 |

| β− | 3H | NIST | IGC | 1961–1999 | 21 | 0.75 | 0.18 (20) | 149 |

| β− | 14C | JRC | LSC | 2002–2014 | 706 | 0.075 | 0.013 (16) | 92 |

| β− | 14C | NMISA | TDCR | 1994–2014 | 32 | 0.250 | 0.067 (80) | 59 |

| β− | 60Co | NIST | IC | 1968–2007 | 250 | 0.050 | 0.007 (7) | 0 |

| β− | 60Co | NIST | LTAC + IC | 2006–2014 | 26 + 7 | 0.036 | 0.007 (9) | 18 |

| β− | 60Co | JSI | HPGe #1–6 | 1998–2016 | 15254 | 0.079 | 0.041 (14) | 161 |

| β− | 85Kr | NIST | IC | 1980–2007 | 98 | 0.035 | 0.036 (15) | 153 |

| β− | 90Sr | PTB | TDCR | 2013–2014 | 4493 | 0.009 | 0.004 (2) | 362 |

| β− | 90Sr | PTB | IC | 1989–2016 | 2207 | 0.009 | 0.018 (2) | 26 |

| β− | 124Sb | JRC | IC | 2007 | 59 | 0.005 | 0.003 (2) | 241 |

| β− | 134Cs | JRC | IC | 2010–2015 | 1065 | 0.002 | 0.0051 (5) | 48 |

| β− | 137Cs | IRA | IC | 1984–2012 | 276 | 0.043 | 0.018 (9) | 342 |

| β− | 137Cs | NRC | IC #1–3 | 1995–2009 | 62 | 0.074 | 0.006 (22) | 147 |

| β− | 137Cs | PTB | IC | 1997–2016 | 2149 | 0.005 | 0.014 (1) | 29 |

| β− | 137Cs | NIST | IC | 1968–2011 | 254 | 0.034 | 0.004 (6) | 33 |

| β+, EC | 22Na | JRC | IC | 2010–2016 | 443 | 0.003 | 0.0047 (6) | 53 |

| EC | 54Mn | JRC | IC | 2006–2009 | 156 | 0.007 | 0.005 (1) | 28 |

| EC | 54Mn | PTB | IC | 2010–2016 | 716 | 0.011 | 0.014 (2) | 78 |

| EC | 55Fe | JRC | IC | 2004–2005 | 595 | 0.007 | 0.004 (3) | 187 |

| EC | 57Co | NIST | IC | 1962–1966 | 97 | 0.089 | 0.055 (22) | 324 |

| EC, β+ | 65Zn | JRC | IC | 2002–2003 | 140 | 0.026 | 0.008 (4) | 163 |

| EC(, β+) | 82Sr/82Rb + 85Sr | NIST | IC | 2007–2008 | 158 | 0.011 | 0.0006 (27) | 240 |

| EC(, β+) | 82Sr/82Rb | NIST | HPGe | 2007–2008 | 23 | 0.46 | 0.073 (75) | 255 |

| EC | 109Cd | JRC | IC | 2006–2010 | 125 | 0.017 | 0.015 (4) | 18 |

| EC | 109Cd | JSI | HPGe #3, 4 | 1998–2016 | 5414 | 0.139 | 0.035 (24) | 346 |

| EC | 109Cd | NIST | IC | 1976–1981 | 167 | 0.058 | 0.013 (15) | 220 |

| EC | 133Ba | NIST | IC | 1979–2012 | 131 | 0.042 | 0.028 (8) | 74 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | IAEA | HPGe #1, 2 | 2010–2016 | 143 | 0.113 | 0.020 (24) | 162 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #8 | 2008–2016 | 1228 | 0.10 | 0.006 (19) | 242 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #26 | 2013–2016 | 499 | 0.10 | 0.027 (23) | 178 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #11 | 2008–2016 | 1168 | 0.10 | 0.048 (21) | 280 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #16 | 2008–2016 | 1260 | 0.08 | 0.062 (18) | 285 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #25 | 2011–2016 | 723 | 0.10 | 0.080 (23) | 213 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #10 | 2008–2016 | 1374 | 0.08 | 0.094 (16) | 206 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #27 | 2011–2015 | 698 | 0.16 | 0.155 (34) | 228 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | SCK | HPGe #13 | 2008–2016 | 1249 | 0.11 | 0.161 (24) | 214 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | NIST | IC | 1976–2011 | 96 | 0.040 | 0.021 (9) | 214 |

| EC, β−, β+ | 152Eu | PTB | IC | 1989–2016 | 2199 | 0.007 | 0.018 (1) | 11 |

| EC(, β+) | 207Bi | NIST | IC | 1971–2011 | 152 | 0.05 | 0.004 (11) | 23 |

The measurement techniques employed are as follows: ionisation current measurements in a re-entrant ionisation chamber (IC) or a hospital calibrator (HIC) [31,32], net area analysis of full-energy γ-ray peaks (and integral spectrum counting) by γ-ray spectrometry with a HPGe detector (HPGe) [33], particle counting in a planar silicon detector in quasi-2πconfiguration (PIPS) [34], X-ray counting at a small defined solid angle with a gas-filled proportional counter (PC) [35,36], live-timed β–γ anti-coincidence counting (LTAC) [37], triple-to-double coincidence counting with a liquid scintillation vial and three photodetectors (TDCR) [38], liquid scintillation counting (LSC) [38], particle and photon counting in a sandwich CsI (Tl) spectrometer (CsI) [39], internal gas counting (IGC) [40], and α-particle counting at a small defined solid angle with a large planar silicon detector (αDSA) [35,36]. An overview of standardisation techniques and their sources of error can be found in the special issues 44(4) and 52(3) of Metrologia [41,42] and references in [25,28].

Exponential decay curves were fitted to the data and the residuals were inspected for annual modulations. The data sets were first compensated for (1) the presence of occasional outlier values, (2) abrupt systematic changes in the detector response, e.g. due to replacement of the electronics or recalibrations of the instrument, and (3) systematic drift extending over periods of more than 1 year, e.g. due to gas loss from an ionisation chamber, uncompensated count loss through pulse pileup in a spectrometer, activity build-up from decay products in a source, etc. The residuals were binned into 8-day periods of the year and averaged to obtain a reduced set of (maximum) 46 residuals evenly distributed over the calendar year. To the averaged residuals, a sinusoidal shape A sin(2π(t+a)/365) has been fitted in which A is the amplitude, t is the elapsed number of days since New Year, and a is the phase shift expressed in days. The fitted amplitude values can be considered insignificant if they are of comparable magnitude as their estimated standard uncertainty (see Table 1).

3. Discussion

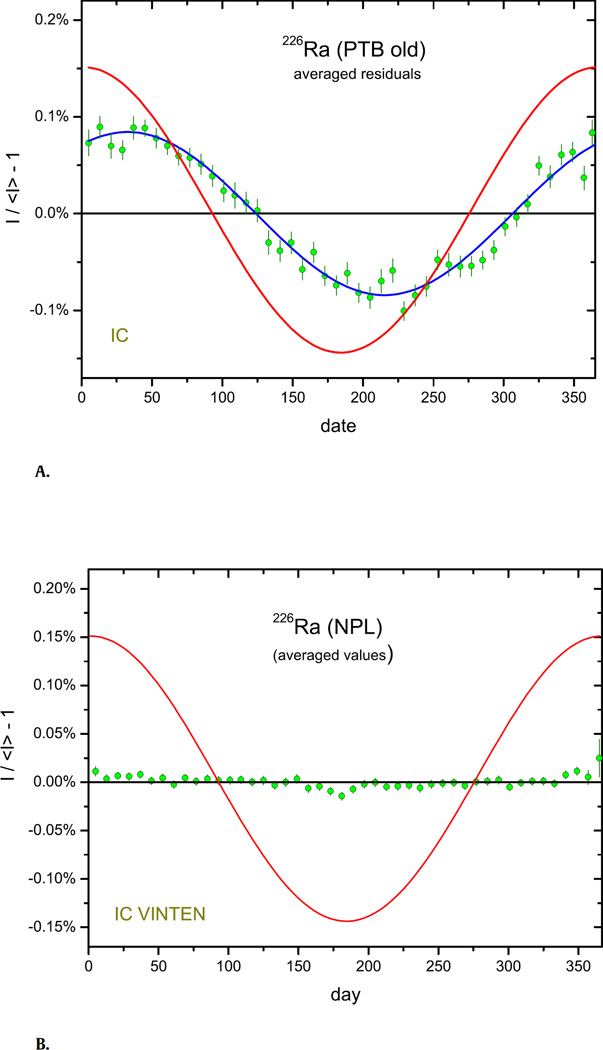

The controversy started with the interpretation [7,8] of A ≈ 0.15% modulations in the decay rate measurements of a sealed 226Ra reference source in an IC at the PTB between 1983 and 1998. The averaged residuals, shown in Fig. 1A, have a sinusoidal shape with amplitude A = 0.083 (2)% and phase a = 59 days. An explanation through solar influence on the alpha or beta decay constants of nuclides in the 226Ra decay series seems unlikely, since the residuals are out of phase with the annual variation of the inverse square of the Sun–Earth distance, 1/R2 (renormalised to 0.15% amplitude in the Figs. 1–2 of this work). The real cause is of instrumental nature, since the modulations were significantly reduced after changing the electrometer of the IC [22,25]. There is a remarkable correlation with average seasonal changes of radon concentration in air (A = 16 (2)%, a = 57 days) measured inside the laboratory from 2010 to 2016, but causality has not been proven.

Fig. 1.

A. Annual average residuals from exponential decay for 226Ra activity measurements with an IC at PTB from 1983 to 1998. The line represents relative changes in the inverse square 1/R2 of the Earth–Sun distance, normalised to an amplitude of 0.15%.

B. Same for 226Ra activity measurements with the Vinten IC of NPL from 1993 to 2016, after renormalisation per calendar year.

At other institutes, annual modulations of smaller amplitude and different phase have been observed, which demonstrates the local character of the non-exponential behaviour. The data sets for 226Ra show a different level of instrumental instability, but the most stable 226Ra measurements prove invariability of its decay constant against annual modulations within 0.0025% to 0.005%. An example is shown in Fig. 1B, comprising 4000 226Ra ionisation current measurements over a period of 22 years at the NPL.

Stability is best achieved where the detector efficiency is least influenced by geometrical and environmental variations and where the signal of the radiation is easily separated from interfering signals and electronic noise. For example, measuring 241Am decay through alpha-particle detection with close to 100% detection efficiency would typically be more stable than through fractional detection of its low-energy photon emissions in a gas-filled pro-portional counter. For the alpha emitters, 209Po, 226Ra, 230U, and 241Am, the invariability of the decay constants was confirmed within the 10−5 level.

Comparably lower stability could be anticipated for beta-minus decay. Parkhomov [10] found 7 data sets of beta-decaying radionuclides exhibiting periodic variations of 0.1% to 0.3% amplitude with a period of 1 year. Fischbach et al. [8,14,15] suggested new theories in which the variable flux of anti-neutrinos from the Sun would significantly modulate the probability for β− emission. From metrological point of view, instability in the detection efficiency for a pure beta emitter can be expected due to the continuous energy distribution of the beta particle which makes the count rate subject to threshold variations at the low-energy side and possibly incomplete detection probability at the high-energy side. However, measurements based on γ-ray emission subsequent to the β− emission – possibly through the decay of a short-lived daughter nuclide – can be made more robust.

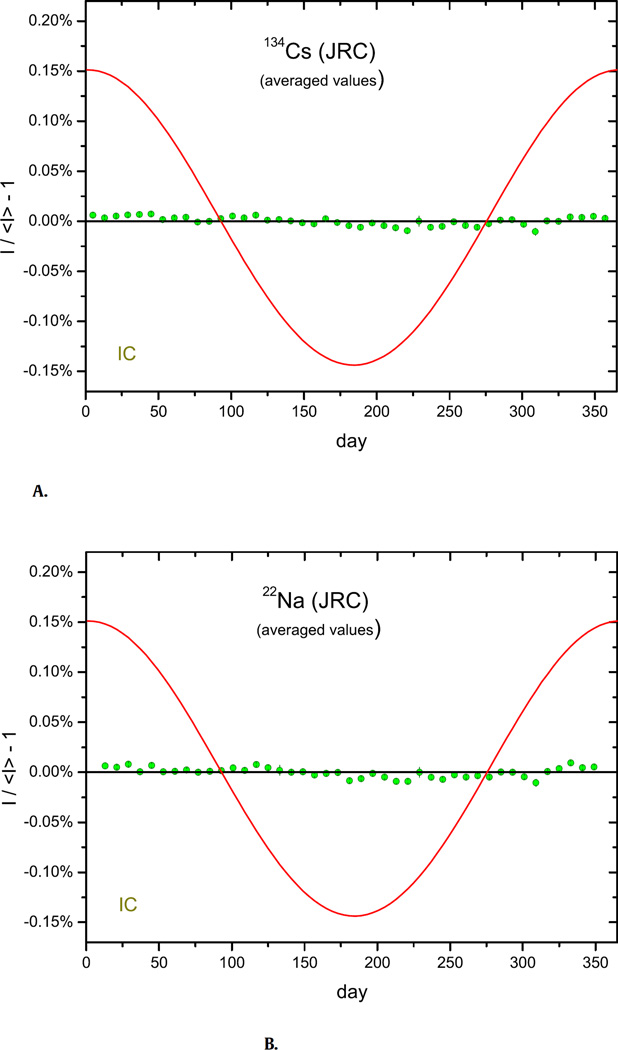

High-quality measurement data were collected for β− emitters in Table 1, mostly obtained by IC but also with primary activity measurement techniques such as the triple-to-double coincidence ratio (TDCR) method and live-timed 4π β–γ anti-coincidence counting (LTAC). It was demonstrated for 36Cl [20], 60Co (Table 1) and 90Sr/90Y [23] that primary standardisation techniques like TDCR and LTAC are more stable than routine counting techniques, because each measurement provides information about the detection efficiency and automatically corrects for its fluctuations. Some IC measurements show remarkable stability, too, and refute the conclusions made about variability of the decay constants as well as the hypothesis of a significant solar influence on the decay rate. In Fig. 2A, averaged residuals for 134Cs in an IC demonstrate stability within the 10−5 range. Evidence of stability down to the 10−5 level was found for the beta minus emitters 60Co, 90Sr, 124Sb, 134Cs and 137Cs, and down to the 10−4 level for 3H, 14C, and 85Kr. These results are in direct contradiction with the permille level oscillations for 3H, 60Co, 90Sr, and 137Cs reported by Parkhomov [10] and Jenkins et al. [11].

Fig. 2.

A. Annual average residuals from exponential decay for 134Cs activity measurements with the IG12 IC at the JRC from 2010 to 2016.

B. Same for 22Na.

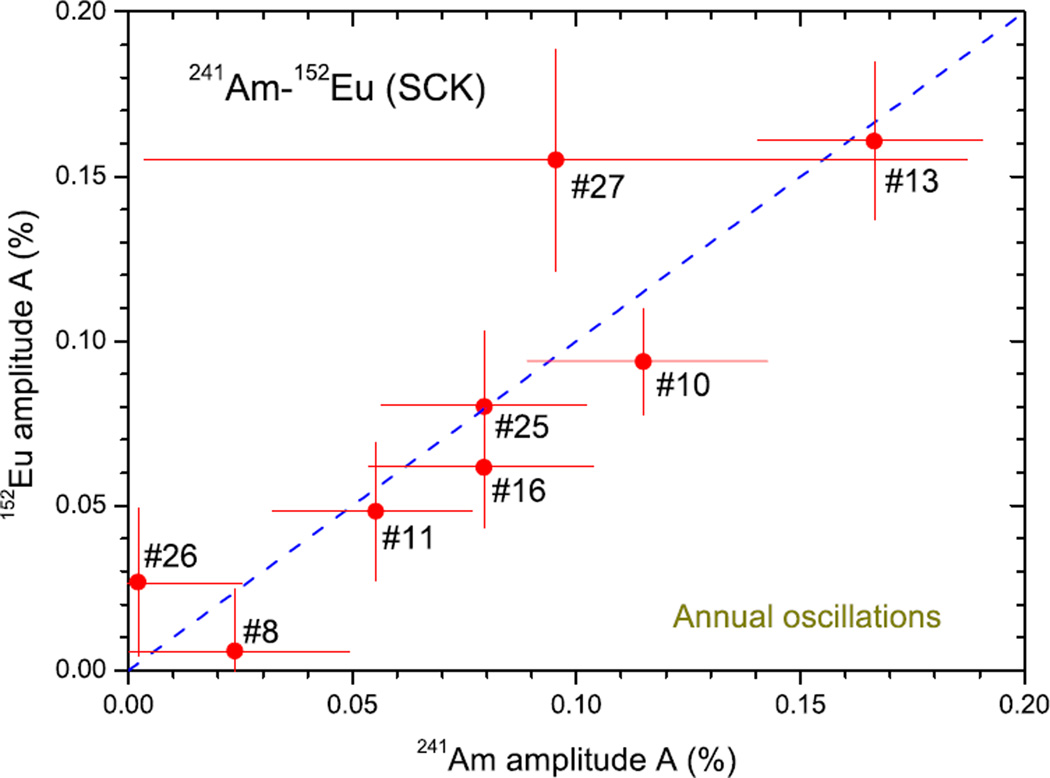

Radionuclides disintegrating by electron capture (EC) and β+ decay – 22Na, 54Mn, 55Fe, 57Co, 65Zn, 82Sr/82Rb+85Sr, 109Cd, 133Ba, 152Eu, and 207Bi – were investigated by the same techniques as α and β− emission and, also here, stability within the 10−5 to 10−4 range was observed in most cases. An example is shown in Fig. 2B for 22Na measured in the same period with the same IC as 134Cs in Fig. 2A. The tiny modulations in the residuals for both nuclides are highly correlated, which is most likely a seasonal effect of instrumental origin. Clear evidence of annual modulations being of instrumental origin has been found in thousands of γ-ray spectrometry measurements with 8 HPGe detectors at the SCK, as shown in Fig. 3: the modulations in measured decay rates for the alpha decay of 241Am and mixed EC, β−, and β+ decay of 152Eu are highly correlated but the amplitude differs from one detector to another. In other words, the modulations are linked to the instrument, not to the type of decay.

Fig. 3.

Amplitude of average annual oscillations in the decay rates of 241Am and 152Eu measured by γ-ray spectrometry with 8 HPGe detectors at SCK between 2008 and 2016. The index refers to the detector number. A mixed 241Am– 152Eu point source was measured 166–466 times in a fixed geometry at about 11 cm from the endcap using the 59 keV line of 241Am and the 122 keV, 779 keV and 1408 keV lines of 152Eu.

4. Conclusions

The experimental data in this work are typically 50 times more stable than the measurements on which recent claims for solar influence on the decay constants were based. The observed seasonal modulations can be ascribed to instrumental instability, since they vary from one instrument to another and show no communality in amplitude or phase among – or even within – the laboratories. The exponential decay law is immune to changes in Earth–Sun distance within 0.008% for most of the investigated α, β−, β+ and EC decaying nuclides alike.

Owing to the invariability of decay constants, there is no impediment to the establishment of the becquerel through primary standardisation at 0.1% range accuracy nor to the demonstration of equivalence of activity at international level over a time span of decades. It is normal for repeated activity measurements to show varying degrees of instability of instrumental and environ-mental origin and such auto-correlated variability should be taken into account next to statistical variations when setting alarm levels in quality control charts. Taking into account such instabilities and adhering to proper uncertainty propagation, no fundamental objections need to be made against half-life measurement with sub-permille uncertainties, nor against applying exponential decay formulas to calculate activity at a future or past reference time or to perform accurate nuclear dating.

Acknowledgments

Funded by SCOAP3.

The authors thank all past and present colleagues who contributed directly or indirectly to the vast data collection over different periods spanning six decades.

References

- 1.Rutherford E. A radio-active substance emitted from thorium compounds. Philos. Mag. Ser. 1900;5 49(296):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curie M, Kamerling Onnes H. Sur le rayonnement du radium à la température de l’hydrogène liquide. Radium. 1913;10(6):181–186. (English version: The radiation of Radium at the temperature of liquid hydrogen. KNAW Proceedings 15 II, 1912–1913, Amsterdam, (1913) 1430–1441) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery GT. Perturbation of nuclear decay rates. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Sci. 1972;22:165–202. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn H-P, Born H-J, Kim J. Survey on the rate perturbation of nuclear decay. Radiochim. Acta. 1976;23:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenland PT. Seeking non-exponential decay. Nature. 1988;335:298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins JH, Fischbach E. Perturbation of nuclear decay rates during the solar flare of 2006 December 13. Astropart. Phys. 2009;31:407–411. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins JH, et al. Evidence of correlations between nuclear decay rates and Earth–Sun distance. Astropart. Phys. 2009;32:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischbach E, et al. Time-dependent nuclear decay parameters: new evidence for new forces? Space Sci. Rev. 2009;145:285–335. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins JH, Mundy DW, Fischbach E. Analysis of environmental influences in nuclear half-life measurements exhibiting time-dependent decay rates. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A. 2010;620:332–342. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkhomov AG. Deviations from beta radioactivity exponential drop. J. Mod. Phys. 2011;2:1310–1317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins JH, Fischbach E, Javorsek D, Lee RH, Sturrock PA. Concerning the time dependence of the decay rate of 137Cs. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2013;74:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturrock PA, et al. Comparative study of beta-decay data for eight nuclides measured at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt. Astropart. Phys. 2014;59:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javorsek D, et al. Power spectrum analyses of nuclear decay rates. Astropart. Phys. 2010;34:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullins J. Is the sun reaching into earthly atoms? New Sci. 2009;202(2714):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark S. Half-life heresy: strange goings on at the heart of the atom. New Sci. 2012;216(2891):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman EB, Browne E, Shugart HA, Joshi TH, Firestone RB. Evidence against correlations between nuclear decay rates and Earth–Sun distance. Astropart. Phys. 2009;31:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semkow TM, et al. Oscillations in radioactive exponential decay. Phys. Lett. B. 2009;675:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellotti E, Broggini C, Di Carlo G, Laubenstein M, Menegazzo R. Search for time dependence of the 137Cs decay constant. Phys. Lett. B. 2012;710:114–117. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy JC, Goodwin JR, Iacob VE. Do radioactive half-lives vary with the Earth-to-Sun distance? Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012;70:1931–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kossert K, Nähle O. Long-term measurements of 36Cl to investigate potential solar influence on the decay rate. Astropart. Phys. 2014;55:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellotti E, et al. Search for time modulations in the decay rate of 40K and 232Th. Astropart. Phys. 2015;61:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nähle O, Kossert K. Comment on “Comparative study of beta-decay data for eight nuclides measured at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt” [Astropart. Phys.. 59 (2014) 47–58] Astropart. Phys. 2015;66:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kossert K, Nähle O. Disproof of solar influence on the decay rates of 90Sr/90Y. Astropart. Phys. 2015;69:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellotti E, Broggini C, Di Carlo G, Laubenstein M, Menegazzo R. Precise measurement of the 222Rn half-life: a probe to monitor the stability of radioactivity. Phys. Lett. B. 2015;743:526–530. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrader H. Seasonal variations of decay rate measurement data and their in-terpretation. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016;114:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pommé S. Methods for primary standardization of activity. Metrologia. 2007;44:S17–S26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratel G. The Système International de Référence and its application in key comparisons. Metrologia. 2007;44:S7–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pommé S. The uncertainty of the half-life. Metrologia. 2015;52:S51–S65. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pommé S. When the model doesn’t cover reality: examples from radionuclide metrology. Metrologia. 2016;53:S55–S64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindstrom RM. Believable statements of uncertainty and believable science. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10967-016-4912-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10967-016-4912-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrader H. Ionization chambers. Metrologia. 2007;44:S53–S66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amiot MN, et al. Uncertainty evaluation in activity measurements using ionization chambers. Metrologia. 2015;52:S108–S122. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lépy M-C, Pearce A, Sima O. Uncertainties in gamma-ray spectrometry. Metrologia. 2015;52:S123–S145. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pommé S. Typical uncertainties in alpha-particle spectrometry. Metrologia. 2015;52:S146–S155. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pommé S, Sibbens G. Alpha-particle counting and spectrometry in a primary standardisation laboratory. Acta Chim. Slov. 2008;55:111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pommé S. The uncertainty of counting at a defined solid angle. Metrologia. 2015;52:S73–S85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzgerald R, Bailat C, Bobin C, Keightley JD. Uncertainties in 4π β–γ coincidence counting. Metrologia. 2015;52:S86–S96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kossert K, Broda R, Cassette P, Ratel G, Zimmerman B. Uncertainty determination for activity measurements by means of the TDCR method and the CIEMAT/NIST efficiency tracing technique. Metrologia. 2015;52:S172–S190. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiam C, Bobin C, Maringer FJ, Peyres V, Pommé S. Assessment of the uncertainty budget associated with 4π γ counting. Metrologia. 2015;52:S97–S107. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unterweger M, Johansson L, Karam L, Rodrigues M, Yunoki A. Uncertainties in internal gas counting. Metrologia. 2015;52:S156–S164. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson B, Judge S. Special issue on radionuclide metrology. Metrologia. 2007;44:S1–S152. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karam L, Keightley J, Los Arcos JM. Uncertainties in radionuclide metrology. Metrologia. 2015;52:S1–S212. [Google Scholar]