Abstract

The chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its chemokine ligand CXCL12 mediate directed cell migration during organogenesis, immune responses, and metastatic disease. However, the mechanisms governing CXCL12/CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis remain poorly understood. Here, we show that the β-arrestin1·signal-transducing adaptor molecule 1 (STAM1) complex, initially identified to govern lysosomal trafficking of CXCR4, also mediates CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis. Expression of minigene fragments from β-arrestin1 or STAM1, known to disrupt the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex, and RNAi against β-arrestin1 or STAM1, attenuates CXCL12-induced chemotaxis. The β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is necessary for promoting autophosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK). FAK is necessary for CXCL12-induced chemotaxis and associates with and localizes with β-arrestin1 and STAM1 in a CXCL12-dependent manner. Our data reveal previously unknown roles in CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis for β-arrestin1 and STAM1, which we propose act in concert to regulate FAK signaling. The β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is a promising target for blocking CXCR4-promoted FAK autophosphorylation and chemotaxis.

Keywords: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR-4), chemokine, chemotaxis, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), PTK2 protein tyrosine kinase 2 (PTK2) (focal adhesion kinase) (FAK), CXCL12, STAM, β-arrestin

Introduction

Chemotaxis is a process by which cells move toward or away from a chemical signal in a directed manner (1). The chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 mediate chemotaxis of many cell types, and in this way this ligand/receptor pair is important during organ development, immune responses, and stem cell mobilization among other processes (2–5). CXCL12/CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis is also involved in several pathologies, in particular cancer (6, 7). CXCR4 is up-regulated in several solid and hematological tumors and together with CXCL12 plays an important role in metastatic disease (8). Metastases are formed by several sequential steps that enable cancer cells from the primary tumor to disseminate to new organ sites through the vascular system (9). This has been linked in part to migration of CXCR4-expressing cancer cells to organs that express CXCL12 (6, 10). Despite the role of CXCR4-dependent cell migration in health and disease, the mechanisms remain poorly understood.

CXCR4 belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)2 family, and typically CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis occurs via G protein-dependent signaling pathways (11). However, β-arrestin-dependent signaling also contributes to CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis (12). CXCL12-promoted migration of T cells and B cells isolated from the spleen of β-arrestin2 knock-out mice is attenuated compared with cells isolated from matched wild-type mice (12). In HEK293 cells, β-arrestin-promoted migration induced by CXCL12 occurs via a p38-dependent pathway (13). β-Arrestins interact with several proteins that regulate the actin cytoskeleton, which undergoes reorganization in response to chemotactic signals acting on other GPCRs (14–16). These studies highlight the fact that β-arrestins regulate cell migration via multiple mechanisms, but detailed insight is lacking.

β-Arrestins also negatively regulate CXCR4 signaling (11). CXCR4 is phosphorylated by G protein-coupled receptor kinases, leading to β-arrestin binding and desensitization of signaling (11, 17). To fully terminate signaling, CXCR4 is rapidly internalized and mainly sorted for lysosomal degradation (18). CXCR4 is ubiquitinated on carboxyl-terminal lysine residues in a CXCL12-dependent manner. The attached ubiquitin moieties target CXCR4 into the lumen of multivesicular bodies by the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) pathway (19, 20). Multivesicular bodies eventually mature and fuse with lysosomes where luminal contents are degraded (21). β-Arrestin1 has a non-canonical role in CXCR4 trafficking in that it directly regulates endosomal sorting of CXCR4 into the ESCRT pathway (22, 23). β-Arrestin1 localizes to endosomes with CXCR4 and interacts with the E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 and ESCRT-0 subunit signal-transducing adaptor molecule 1 (STAM1) (22, 23). β-Arrestin is predicted to act as an adaptor for AIP4-dependent ubiquitination of STAM1 at endosomes (23). Consistent with this, disruption of the interaction between STAM1 and β-arrestin1 by expression of dominant negative fragments from either β-arrestin1 or STAM1 attenuates STAM1 ubiquitination instigated by CXCR4 signaling (23). When STAM1 ubiquitination is attenuated, CXCR4 degradation is accelerated following agonist treatment (23). Thus, the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is an important regulator of CXCR4 trafficking to lysosomes, but its role in CXCR4 signaling and functional responses remains to be determined.

In this study, we explored whether targeting the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex impacts CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis. Our findings reveal that expression of fragments from either β-arrestin1 (βArr1(25–161)) or STAM1 (STAM1(296–380)), which we have previously shown to disrupt the interaction between β-arrestin1 and STAM1 (23), attenuates CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis of HeLa cells. Unexpectedly, this cannot be explained due to changes in CXCR4 cell surface levels or altered CXCR4 signaling because of poor G protein coupling. Instead, disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex selectively attenuates CXCL12-induced autophosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which is required for CXCR4-promoted chemotaxis. β-Arrestin1 and STAM1 interact with and colocalize with FAK in a CXCL12-dependent manner. Our data indicate that β-arrestin1 and STAM1 cooperate to promote CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis, which we propose occurs by regulating FAK activity.

Results

Disruption of the β-Arrestin1·STAM1 Complex Attenuates CXCR4-promoted Chemotaxis

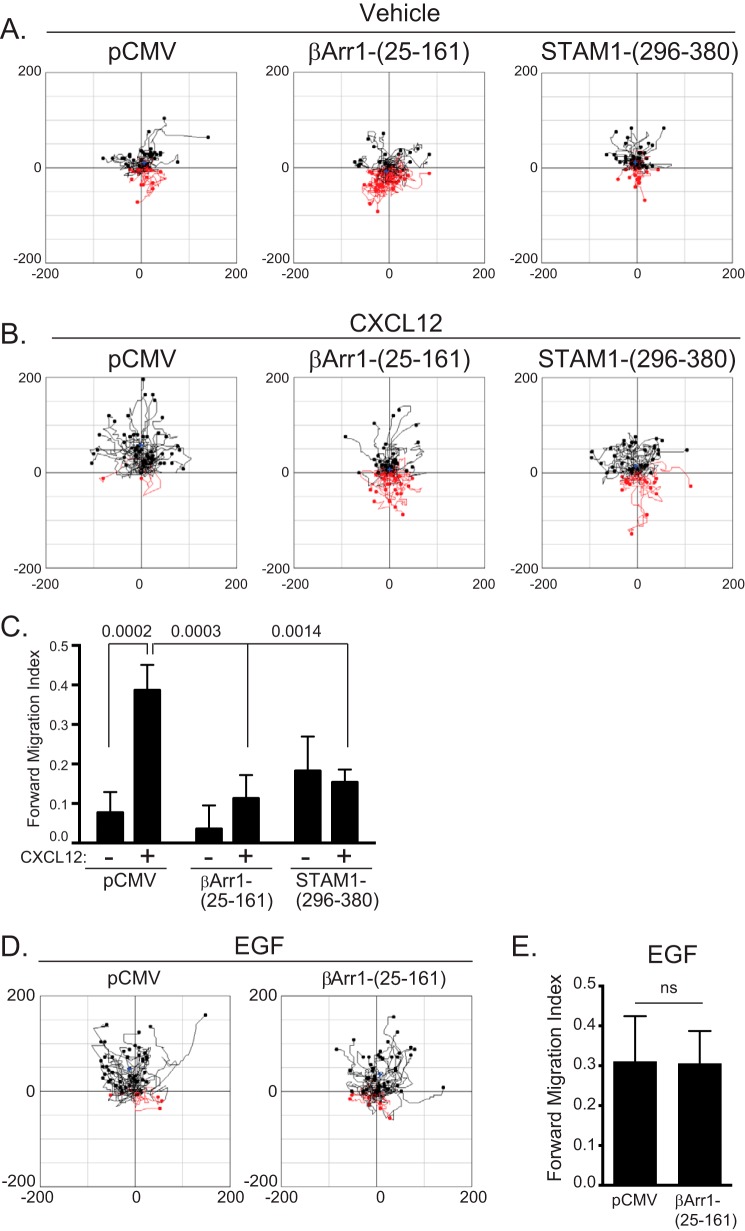

We initially determined whether disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex by expression of βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380) in HeLa cells has an impact on CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis. This was examined using μ-Slide chemotaxis chambers (Ibidi, Germany), which can maintain a stable gradient of CXCL12 up to 16–24 h (24, 25). When CXCL12 is only present in the upper chamber, HeLa cells move in this direction, indicating chemotaxis, which does not occur when it is present in both chambers (data not shown). HeLa cells transfected with either empty vector (pCMV) or FLAG-tagged βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380) showed similar random motility in the absence of a gradient (vehicle) (Fig. 1A). In the presence of a CXCL12 gradient, HeLa cells transfected with empty vector (pCMV) migrated up the gradient (Fig. 1B). In contrast, HeLa cells transfected with βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380) showed reduced migration up the CXCL12 gradient (Fig. 1B). Analysis of migration revealed a significantly reduced forward migration index in both groups compared with control (Fig. 1C). The effect on chemotaxis was likely not due to a global effect on the motility machinery because expression of βArr1(25–161) did not impact chemotaxis of HeLa cells up a gradient of epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Fig. 1D). The forward migration index was similar in cells transfected with pCMV or βArr1(25–161) (Fig. 1E). Together, these data suggest that disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex impacts CXCL12-dependent chemotaxis.

FIGURE 1.

Disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex attenuates CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis. HeLa cells transiently transfected with empty vector (pCMV), FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161), or FLAG-STAM1(296–380) were passaged onto μ-Slide chemotaxis chambers and analyzed by time lapse microscopy for 18 h in the absence (vehicle) or presence of a gradient of CXCL12 (50 nm at its source). A and B, aggregated trajectories of individual cells in the presence of vehicle (A) or CXCL12 (B) from a representative experiment. Trajectories in black and red represent cells that migrated toward or away from the chemoattractant gradient, respectively. C, the graph represents the mean forward migration index in the absence or presence of CXCL12 from tracking 150 cells from three (vehicle) or 200 cells from four (CXCL12) independent experiments. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. p values are provided. D, aggregated trajectories of individual cells in the presence of EGF (200 ng/ml at its source) from a representative experiment. E, the forward migration index is shown from tracking 100 cells from two independent experiments. The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed by Student's t test and are not significant (ns).

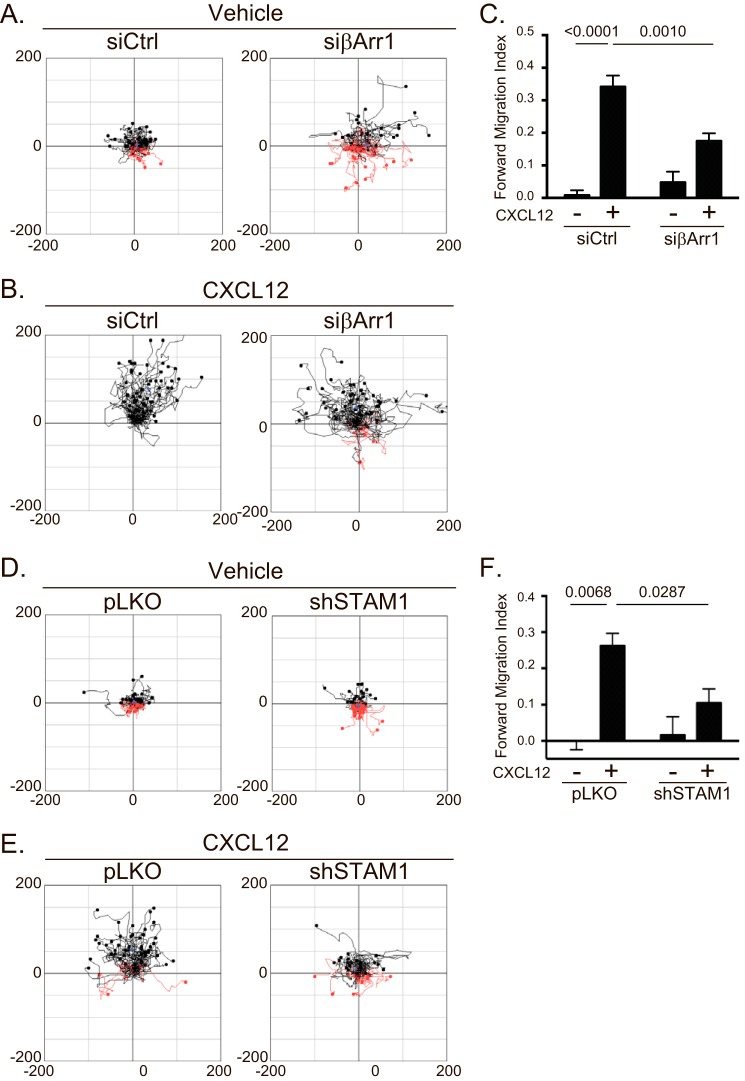

β-Arrestin1 and STAM1 Are Involved in CXCR4-dependent Chemotaxis

β-Arrestins have been previously shown to be involved in CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis (13), but whether STAM1 plays a role remains unknown. To explore this, we examined CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis in HeLa cells depleted of β-arrestin1 or STAM1 by RNAi. Cells treated with β-arrestin1 siRNA showed similar random motility compared with control cells in the absence of a gradient (vehicle) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, chemotaxis up a gradient of CXCL12 was attenuated in cells treated with β-arrestin1 siRNA compared with control (Fig. 2B). The forward migration index was significantly reduced compared with control (Fig. 2C). Similarly, HeLa cells treated with shSTAM1 showed similar random motility compared with control in the absence of a gradient (vehicle) (Fig. 2D) and showed attenuated chemotaxis up a gradient of CXCL12 compared with control (Fig. 2E). The forward migration index was significantly reduced compared with control (Fig. 2F). The depletion of β-arrestin1 or STAM1 from each experiment was confirmed by immunoblotting (data not shown). These data indicate that β-arrestin1 and STAM1 are required for CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis.

FIGURE 2.

Depletion of β-arrestin1 or STAM1 attenuates CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis. HeLa cells transiently transfected with siRNA against β-arrestin1 or shRNA against STAM1 were passaged onto μ-Slide chemotaxis chambers and analyzed by time lapse microscopy for 18 h in the absence (vehicle) or presence of a gradient of CXCL12 (50 nm at its source). A, B, D, and E, aggregated trajectories of individual cells transfected with either βArr1 siRNA (A and B) or STAM1 shRNA (D and E) in the presence of vehicle (A and D) or CXCL12 gradient (B and E). C and F, the forward migration index was calculated from 100 control siRNA (siCtrl) (two experiments)-, 200 βArr1 siRNA (four experiments)-, 150 pLKO (three experiments)-, or 150 STAM shRNA (three experiments)-transfected cells. The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. p values are provided.

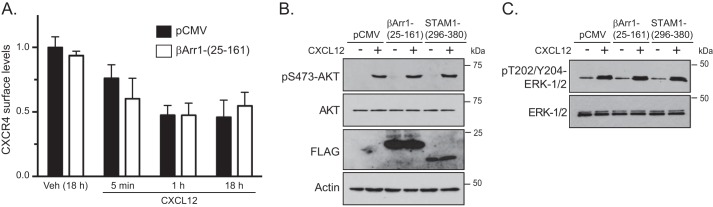

The β-Arrestin1·STAM1 Complex Does Not Regulate CXCR4 Surface Levels or G Protein Coupling

Because disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex leads to accelerated CXCL12-dependent degradation of CXCR4 (23), attenuated chemotaxis in response to CXCL12 may be due to a loss in the total cellular complement of CXCR4, leading to reduced cell surface expression (26, 27). To explore this, we examined CXCR4 surface expression by flow cytometry in HeLa cells transfected with βArr1(25–161) or vector control (pCMV). Basal CXCR4 cell surface levels were similar in cells transfected with βArr1(25–161) compared with control (data not shown). Stimulation of control-transfected cells (pCMV) with CXCL12 for 18 h, which is the time that cells were exposed to the CXCL12 gradient in the chemotaxis assay, reduced the cell surface expression of CXCR4 by up to 50% when compared with vehicle, consistent with receptor internalization and lysosomal degradation (Fig. 3A). However, there was no difference between control- and βArr1(25–161)-transfected cells (Fig. 3A). Similarly, there was no difference in CXCR4 surface expression between control- and βArr1(25–161)-expressing cells following stimulation with CXCL12 for 5 or 60 min (Fig. 3A). Although the rate of CXCR4 degradation is increased by disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex, it does not have an impact on CXCR4 cell surface levels. This was surprising, but it is possible that receptor degradation is matched by de novo synthesis when this complex is disrupted. Nevertheless, these data imply that surface availability cannot explain the reduced chemotaxis observed in cells expressing βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380).

FIGURE 3.

Disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex does not alter CXCR4 cell surface expression or CXCR4-promoted Akt or ERK-1/2 activation. A, surface expression of CXCR4 was analyzed by flow cytometry in cells transfected with empty vector (pCMV-10) or FLAG-βArr1(25–161). Cells were serum-starved for 1 h and then treated with vehicle (18 h) or 30 nm CXCL12 for 18 h, 1 h, or 5 min. Cells were fixed and stained with a phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody against CXCR4 or IgG2a (isotype control) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean of the florescence intensity relative to vehicle-treated cells transfected with empty vector. The error bars represent the S.D. from two independent experiments. B and C, HeLa cells transiently transfected with FLAG-βArr1(25–161), FLAG-STAM1(296–380), or empty vector (pCMV-10) were serum-starved for 3 h and treated with 10 nm CXCL12 or vehicle (PBS with 0.1% BSA) for 5 min. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown.

We next explored whether expression of βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380) has an impact on G protein coupling by examining ERK-1/2 and Akt signaling, which are activated via G protein-dependent pathways by CXCR4 in HeLa cells (28, 29) and are also required for CXCR4-promoted chemotaxis (30, 31). Expression of βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380) did not impact CXCL12-promoted activation of Akt (Fig. 3B) or ERK-1/2 (Fig. 3C) signaling as determined by immunoblotting for the phosphorylated and active forms of these kinases. FLAG-tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is not involved in G protein coupling or activation of Akt or ERK-1/2 signaling.

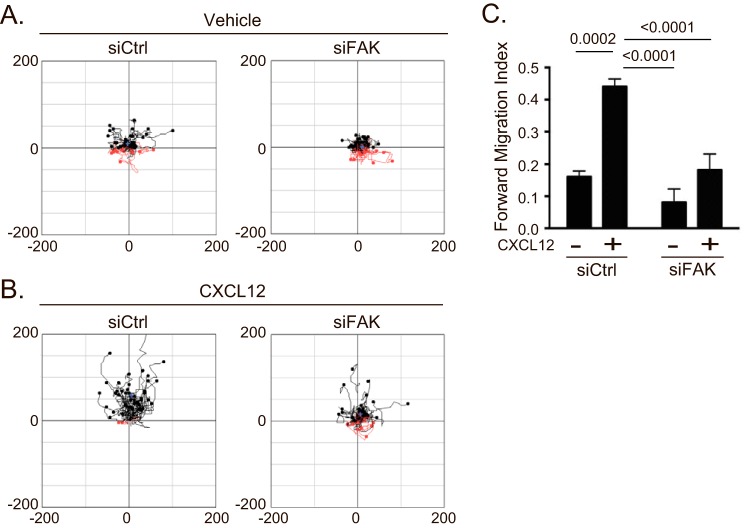

The β-Arrestin1·STAM1 Complex Regulates FAK Autophosphorylation

Next, we set out to identify the signaling pathway by which the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex mediates chemotaxis. We focused on FAK, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase involved in CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis of hematopoietic precursor cells (32, 33). First, we determined whether FAK is necessary for CXCR4-promoted chemotaxis of HeLa cells. Cells transfected with FAK siRNA showed attenuated chemotaxis toward a gradient of CXCL12 compared with control (Fig. 4, A and B). The forward migration index was significantly attenuated compared with control (Fig. 4C). The depletion of FAK was confirmed by immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Depletion of FAK attenuates CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis. A and B, chemotaxis of HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) or siRNA against FAK was analyzed as in Fig. 3. Aggregated trajectories of individual cells transfected with either control or FAK siRNA in the presence of vehicle (A) or CXCL12 gradient (B) are shown. C, the forward migration index was calculated from 200 vehicle (two experiments)- or CXCL12 (three experiments)-treated cells that were transfected with control siRNA and 300 vehicle (three experiments)- or 400 CXCL12 (four experiments)-treated cells that were transfected with FAK siRNA. The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. p values are provided.

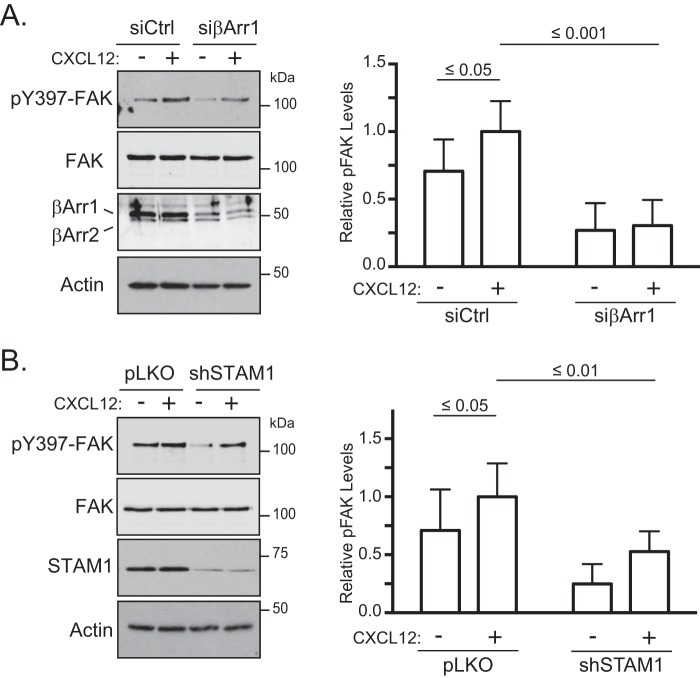

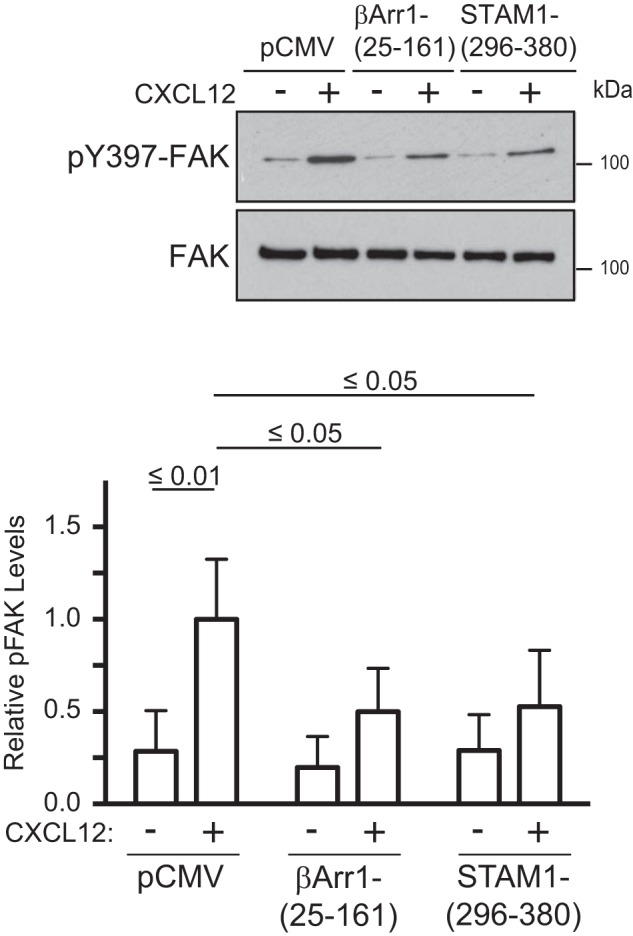

Next, we examined FAK activation by immunoblotting for the phosphorylation status of tyrosine residue 397 (Tyr-397), an amino acid residue that is triggered by several stimuli to be autophosphorylated (34, 35), including CXCL12 (32, 36). In cells expressing βArr1(25–161) or STAM1(296–380), CXCL12-induced phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397 was significantly attenuated compared with control (Fig. 5). We also examined FAK autophosphorylation in intact cells by fluorescence microscopy using an anti-phosphorylated FAK at Tyr-397 (Tyr(P)-397-FAK) antibody. First, we confirmed the specificity of the anti-Tyr(P)-397-FAK antibody. Staining with this antibody was significantly reduced in cells treated with two small molecule inhibitors of FAK, indicating antibody specificity toward Tyr(P)-397-FAK (Fig. 6A and quantified in Fig. 6B). Next, immunostaining of Tyr(P)-397-FAK was examined in cells transiently transfected with YFP-tagged βArr1(25–161) and stimulated with 30 nm CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min. In non-transfected cells, Tyr(P)-397-FAK fluorescence intensity levels were significantly higher in cells stimulated with CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min compared with vehicle control (Fig. 6C and quantified in Fig. 6D). In contrast, in cells transfected with YFP-βArr1(25–161), the intensity levels of Tyr(P)-397-FAK were unchanged in stimulated cells compared with vehicle control, providing further evidence that βArr1(25–161) inhibits CXCR4-promoted FAK autophosphorylation (Fig. 6C and quantified in Fig. 6D). We also examined the role of β-arrestin1 and STAM1 in CXCR4-promoted FAK autophosphorylation by RNAi. CXCL12-induced FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 was significantly attenuated by siRNA against β-arrestin1 (Fig. 7A) or shRNA against STAM1 (Fig. 7B). Together, these data imply that CXCR4-promoted FAK signaling is mediated by an assembled β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex.

FIGURE 5.

Disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex attenuates CXCR4-promoted autophosphorylation of FAK. A, HeLa cells transfected with the indicated DNA constructs were treated with CXCL12 for 5 min, and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for FAK or Tyr(P)-397-FAK. Representative immunoblots from four independent experiments are shown. Bottom, the graph represents the densitometric analyses showing the relative levels of Tyr(P)-397-FAK (pFAK) compared with the control pCMV-transfected cells treated with CXCL12 of four independent experiments. The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. p values between the indicated groups are shown.

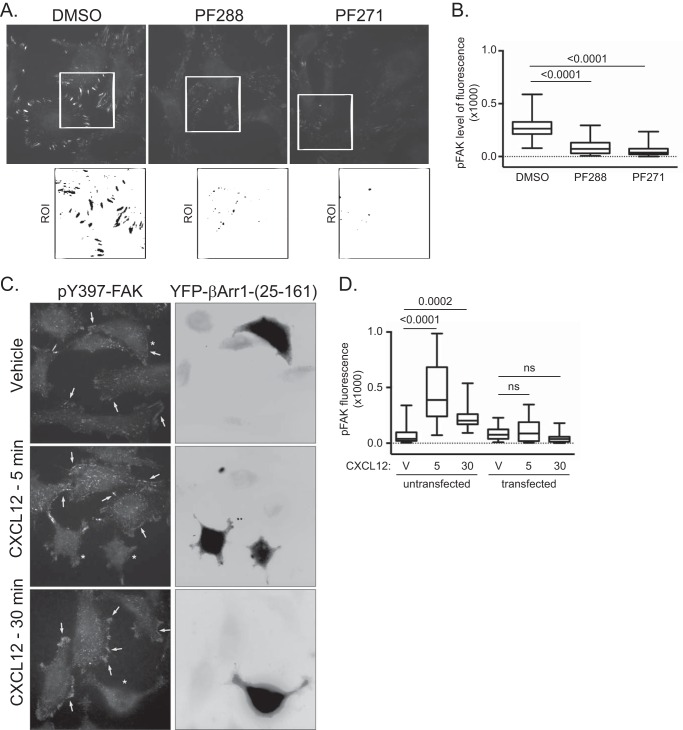

FIGURE 6.

Validation of the Tyr(P)-397-FAK antibody for fluorescence microscopy. A, immunostaining of HeLa cells with an anti-Tyr(P)-397-FAK (BD Biosciences) antibody. HeLa cells grown on PLL-coated coverslips in serum-containing medium were treated with vehicle (DMSO) and FAK inhibitors PF573228 (PF288) (1 μm) and PF562271 (PF271) (1 μm) for 3 h. Shown are representative images. The white box indicates ROI, shown enlarged in the inset below, and is inverted. B, box plot of Tyr(P)-397-FAK intensity. The fluorescence intensity of Tyr(P)-397-FAK was determined from cells in 10 fields of view, and three to five regions of interests per field of view were analyzed. The fluorescence intensity per area of region of interest was calculated, and values are represented in a box plot. The upper limit of the box represents the 75th percentile, and the lower limit represents the 25th percentile. The horizontal line within the box represents the median. The whiskers represent the maxima and minima values. Values that exceeded two standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the analysis. p values from one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test are provided. C, representative images of anti-Tyr(P)-397-FAK immunostaining of HeLa cells transiently transfected with YFP-β-arrestin1(25–161) and treated with CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min and vehicle for 30 min. The arrows point to high Tyr(P)-397-FAK levels in cells stimulated with CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min. In vehicle-treated cells, arrows point to edges of cells. The asterisks mark cells that are transfected with YFP-β-arrestin1(25–161). Shown are the inverted images of YFP-β-arrestin1(25–161). D, the fluorescence intensity of Tyr(P)-397-FAK in YFP-β-arrestin1(25–161)-transfected and untransfected cells was determined from cells in 20–30 fields of view and 37 regions of interest per condition from two independent experiments. The fluorescence intensity per surface area of region of interest was calculated, and values are represented in a box plot. The upper limit of the box represents the 75th percentile, and the lower limit represents the 25th percentile. The horizontal line within the box represents the median. The whiskers represent the maxima and minima values. Values that exceeded two standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the analysis. Adjusted p values from one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test are provided. V, vehicle. 5 and 30 represent the time in minutes cells were treated with 10 nm CXCL12. ns, not significant.

FIGURE 7.

RNA interference against β-arrestin1 or STAM1 attenuates CXCR4-promoted autophosphorylation of FAK. HeLa cells transfected with β-arrestin1 siRNA (A) or STAM1 shRNA (B) were treated with 10 nm CXCL12 for 5 min and analyzed as in Fig. 5A. Representative immunoblots from five (A) or seven (B) independent experiments are shown. Graphs represent the densitometric analyses showing the relative levels of Tyr(P)-397-FAK (pFAK) compared with the control (siCtrl in A or pLKO in B)-transfected cells treated with CXCL12. The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. p values between the indicated groups are shown.

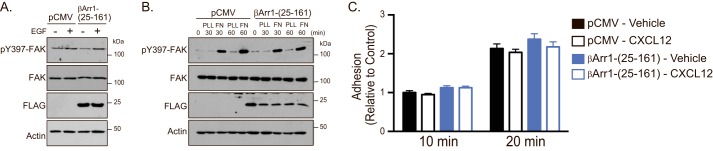

Because FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 is triggered by many stimuli, we examined whether this is broadly mediated by β-arrestin1·STAM1 (37). Expression of βArr1(25–161) did not impact EGF (Fig. 8A)- or fibronectin (Fig. 8B)-induced autophosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397, suggesting that EGF receptor- or adhesion-induced FAK signaling are not regulated by the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex. This is consistent with a lack of an effect of expression of βArr1(25–161) on EGF-induced chemotaxis (Fig. 1E) or on adhesion of cells to fibronectin (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

βArr1(25–161) selectively regulates CXCR4-promoted signaling. A, HeLa cells transfected with empty vector (pCMV) or FLAG-βArr1(25–161) were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml), and cell lysates were analyzed as in Fig. 5A. Immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated DNA constructs, serum-starved for 3 h, detached, and seeded onto 6-well dishes that were uncoated (UN) or coated with FN (10 μg/ml) or PLL (100 μg/ml) for 30 or 60 min. Equal amounts of lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. C, HeLa cells transfected with the indicated DNA constructs treated with vehicle or 10 nm CXCL12 for 5 min were plated onto fibronectin (10 μg/ml)-coated 96-well plates for 10 or 20 min. Cells were washed, and the number of attached cells was determined by crystal violet staining and spectrophotometrical analysis at 595 nm. Bars represent the average absorbance compared with control (pCMV-transfected cells treated with vehicle). The error bars represent the S.D. from three independent experiments.

FAK Interacts with and Colocalizes with β-Arrestin1 and STAM1

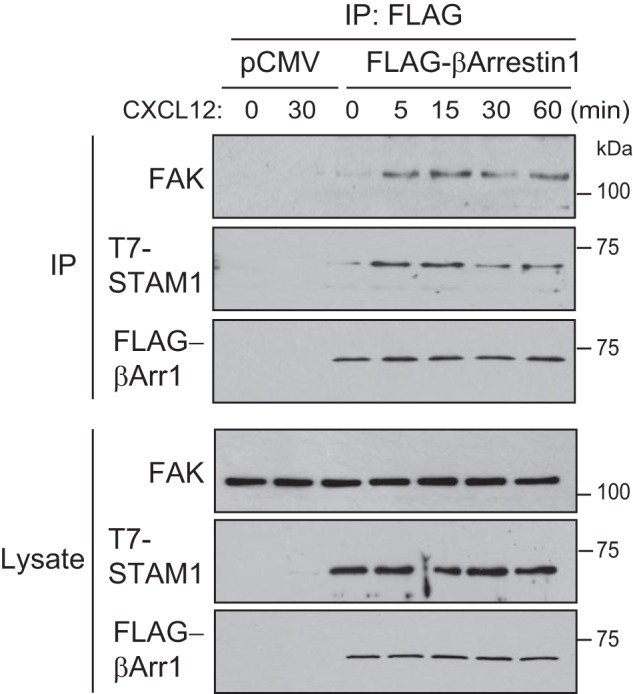

Next, we examined whether FAK interacts with the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex. To determine this, we performed immunoprecipitation of lysates prepared from cells transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged β-arrestin1 and T7-tagged STAM1 with an antibody to the FLAG epitope. The FLAG antibody co-immunoprecipitated T7-STAM1 in CXCL12-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 9) as expected based on our previous study (23). The amount co-immunoprecipitated was maximal at 5 min of CXCL12 treatment and persisted for up to 60 min (Fig. 9). Similarly, endogenous FAK co-immunoprecipitated with the FLAG antibody, but not from control lysates, with maximal association at 5 min of CXCL12 treatment that persisted for up to 60 min. These data indicate that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex associates with FAK in a CXCL12-dependent fashion.

FIGURE 9.

FAK exists in a CXCR4-promoted complex with β-arrestin1 and STAM1. HeLa cells transfected with β-arrestin1-FLAG and T7-STAM1 were treated with 10 nm CXCL12 for 5, 15, 30, or 60 min and vehicle for 60 min. For controls, HeLa cells transfected with pCMV (empty vector) were treated with vehicle or 10 nm CXCL12 for 30 min. Cleared lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitates and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown.

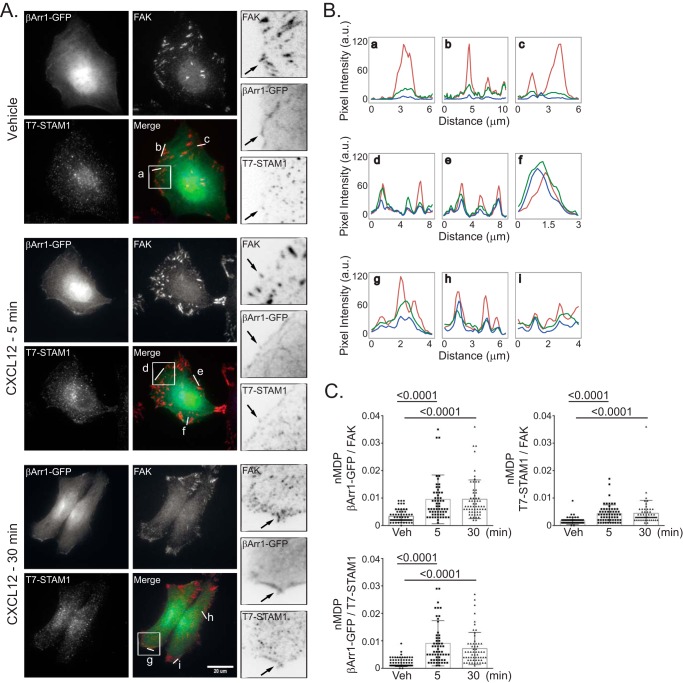

Next, we examined the cellular distribution of β-arrestin1, STAM1, and FAK by fluorescence microscopy. HeLa cells transiently transfected with T7-STAM1 and β-arrestin1-GFP were serum-starved for 3 h and then treated with vehicle for 30 min and CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min. In vehicle- or CXCL12-treated cells, β-arrestin1-GFP was mostly diffusely distributed within the cytoplasm (Fig. 10A), and some was also present in a dotlike pattern and was also localized to regions of the cell periphery, consistent with other reports (38). T7-STAM1 showed a dotlike pattern, consistent with its vesicular distribution, which is similar to what we have reported previously(23). FAK was found in patches at the cell edges, consistent with its localization to focal adhesions, and it was also present in a dotlike pattern. Focal adhesions were likely formed by secretion of extracellular matrix factors. Line scan analysis from several regions of vehicle-treated cells revealed some overlap among β-arrestin1, STAM1, and FAK (Fig. 10B, a–c), which was more noticeable in cells treated with CXCL12 for 5 (Fig. 10B, d–f) or 30 min (Fig. 10B, g–i). Colocalization was determined by calculating the normalized mean deviation product (nMDP) correlation, which revealed significant colocalization among β-arrestin1/FAK, STAM1/FAK, and β-arrestin1·STAM1 (Fig. 10C). Taken together, these data suggest that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is recruited to FAK-containing structures following CXCL12 stimulation.

FIGURE 10.

Localization of FAK, β-arrestin1-GFP, and T7-STAM1 by fluorescence microscopy. A, HeLa cells transfected with β-arrestin1-GFP and T7-STAM1 seeded onto coverslips were treated with 10 nm CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min or for 30 min with vehicle. Images were acquired for β-arrestin1-GFP (green), FAK (red), and T7-STAM1 (blue) using identical acquisition settings for parallel samples in each channel. B, the fluorescence intensity profiles of the indicated lines (a–i) within the merged images are shown. C, colocalization analysis among the indicated proteins is shown as nMDP values for 60 ROIs (three independent experiments, five cells per experiment, four ROIs per cell). The error bars represent the S.D. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. p values are provided. Distance per pixel was calibrated to equal 0.156 μm. Scale bar, 20 μm. a.u., arbitrary units.

Discussion

The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine/chemokine receptor pair plays an important role in mediating chemotaxis during normal and pathophysiological conditions (2–5); however, the molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Our data establish previously unknown roles for β-arrestin1 and STAM1 in CXCR4-promoted FAK and chemotactic signaling. We provide evidence that an assembled complex of β-arrestin1 and STAM1 is required to stimulate autophosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397. β-Arrestin1 and STAM1 interact with and partially colocalize with FAK following CXCL12 stimulation. We propose that this is linked to the ability of CXCR4 to drive directed cell migration in response to a gradient of its ligand CXCL12. FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 generates a high affinity binding site for Src homology 2 (SH2)-containing proteins, including the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src (35). Src phosphorylates residues within the FAK kinase domain activation loop (Tyr-576 and Tyr-577), leading to a fully activated Src·FAK complex, which acts on several aspects of the cell motility machinery (35). Together, our data suggest that an assembled β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex may spatially regulate FAK activity to promote CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis.

Previously, we showed that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex regulates lysosomal trafficking of CXCR4 (23). Our results here show that this complex also regulates CXCR4-promoted FAK autophosphorylation. Therefore, the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex may serve a dual function in CXCR4 trafficking and signaling. To traffic to lysosomes, CXCR4 is ubiquitinated and targeted via the ESCRT pathway from the limiting membrane of maturing endosomes into intraluminal vesicles (39). Our published data suggest that β-arrestin1 binding to STAM1 delays targeting into intraluminal vesicles, thereby increasing the residency time of CXCR4 on the limiting membrane of endosomes (23). In this way, it is possible that this may facilitate interactions with CXCR4, via β-arrestin1·STAM1, and signaling molecules such as FAK. Consistent with this, β-arrestin1, STAM1, and FAK colocalize and exist as a complex in cells (Figs. 9 and 10). We propose that expression of the minigenes disrupts the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex and its interaction with FAK, culminating in accelerated CXCR4 degradation (23). Further investigation is required to precisely define the mechanism by which this occurs.

We provide evidence that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is selective toward FAK signaling. Expression of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 disrupting minigenes impacts FAK signaling but not ERK-1/2 or Akt signaling (Fig. 3C). Previously, we showed that STAM1, but not β-arrestin1, is involved in CXCR4-promoted ERK-1/2 activation (28). We believe that a discrete pool of STAM1 is involved in ERK-1/2 signaling; this pool is separate from the pool that assembles with β-arrestin1 to promote FAK signaling, which is not impacted by expression of the minigenes (Fig. 3C). STAM1 is also involved in CXCR4-promoted Akt signaling, but this also likely does not involve the pool that is involved in ERK-1/2 signaling (Fig. 3B), although we have yet to investigate whether β-arrestin1 has a role (29). It is still possible that the minigenes may impact ERK-1/2 or Akt signaling via other GPCRs as β-arrestins scaffold several proteins involved in these pathways (40, 41). For example, the STAM1 binding site on β-arrestin1 partially overlaps with the binding site of MEK1, which is involved in ERK-1/2 signaling (42).

The functional consequence of the interaction between β-arrestin1 and STAM1 is to promote CXCR4-dependent cell migration. This is likely mediated by an interaction between β-arrestin1 and STAM1 because expression of the minigenes attenuates chemotaxis (Fig. 1). Our data are also consistent with other studies that have shown that β-arrestins (12, 13) and FAK (32) are involved in CXCR4-promoted cell migration. Here, we establish that STAM1 is also required. We focused on β-arrestin1 in our studies because β-arrestin2 does not interact with STAM1 or regulate CXCR4 trafficking as efficiently as β-arrestin1 (22, 23). Interestingly, β-arrestin2, but not β-arrestin1, is necessary for CXCL12-promoted migration of T cells and B cells (12). In HEK293 cells, CXCR4-promoted migration is mediated by β-arrestin2 (13). It is possible that β-arrestin1 regulates CXCR4-promoted cell migration via STAM1 and FAK, whereas for β-arrestin2 it occurs via a distinct mechanism. Although the minigenes attenuate chemotaxis and FAK autophosphorylation, we cannot exclude the possibility that the minigenes impact other interactions with β-arrestin1 that may affect chemotaxis (43). It is also important to note that although others (13) and the present study have shown that β-arrestins are involved in CXCR4-promoted migration of HeLa cells, this seems to be completely dependent upon pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins (25). How this reconciles with our results remains to be investigated.

It will be important to determine how broadly the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex regulates GPCR-promoted FAK signaling. To date, to the best of our knowledge, this complex has only been linked to CXCR4 trafficking (23). β-Arrestin2 has been previously linked to FAK signaling via the GPCR for luteinizing hormone whereby β-arrestin2 promotes FAK activation through scaffolding Fyn, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase (44). Whether STAM1 plays a role is unknown. Future studies will be directed toward understanding how broadly β-arrestin1·STAM1 is involved in GPCR trafficking and/or FAK signaling.

In addition to CXCR4, CXCL12 is also a ligand for CXCR7, which is also expressed in HeLa cells (45). Although CXCR7 (also known as ACKR3) binds to CXCL12 with high affinity, it acts mainly as a scavenger receptor, not a signaling receptor (46). However, some evidence suggests it may signal via β-arrestins (47) or G proteins (48) in certain cell types. CXCR4 may also heterodimerize with CXCR7, which somehow promotes CXCL12-dependent β-arrestin signaling via CXCR7 and impacts chemotaxis (49). We observed that siRNA against CXCR7 leads to a modest enhancement of signaling in response to CXCL12 in HeLa cells (data not shown), consistent with its role as a scavenger receptor and with the idea that CXCR7 has minimal impact on CXCL12 signaling in HeLa cells.

Our data suggest that an assembled β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex is required for FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 following stimulation with CXCL12. The reason for this remains unclear. FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 is triggered by stimulation of many cell signaling receptors (37), and in the context of integrin signaling FAK dimerization may facilitate autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 (50). In an analogous manner, each subunit in an assembled β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex may bind to FAK in a way that would facilitate FAK dimerization and/or phosphorylation of Tyr-397. Other mechanisms are also possible (51), but rigorous biochemical and structural studies are required to delineate the precise mechanism by which the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex stimulates FAK autophosphorylation.

FAK is typically activated by integrin receptor signaling and is linked to focal adhesion turnover, a process that is necessary for chemotaxis (52). Previously, STAM was localized to focal adhesions, although to the best of our knowledge its role there remains unknown (53). β-Arrestins have been linked to focal adhesion turnover in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells, but this occurs in a GPCR-independent manner that may be linked to a role in integrin internalization (54). Expression of βArr1(25–161) did not impact integrin-mediated FAK autophosphorylation or cell adhesion (Fig. 8, B and C, respectively), suggesting that cross-talk to integrin receptors may not be connected to the role that the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex has in CXCR4-promoted chemotaxis.

STAM1 is a subunit of ESCRT-0, which comprises a heterodimer of STAM and HRS (55). Previous studies have shown that HRS can be detected in immunoprecipitates of β-arrestin1 along with STAM1, suggesting that β-arrestin1 associates with an intact ESCRT-0 (23). The related STAM2 isoform interacts weakly with β-arrestin1 (23), suggesting that STAM2 is likely not involved in FAK signaling. The role of HRS or an intact ESCRT-0 in FAK signaling remains to be addressed. However, because ESCRT-0 plays a broad role in down-regulation of cell signaling receptors, it is possible that disruption of the β-arrestin1·STAM1 complex deleteriously impacts the activity of ESCRT-0 or the ESCRT pathway in general. This is unlikely because EGF receptor lysosomal degradation (23), EGF-promoted FAK signaling (Fig. 7A), and chemotaxis (Fig. 1, D and E) are not impacted by expression of the minigenes. In addition, the ESCRT pathway has been shown to target integrin receptors for lysosomal degradation (56), but integrin signaling and cell adhesion (Fig. 8, B and C) are not impacted by expression of the minigenes.

CXCR4 is overexpressed in over 20 solid tumors as well as several hematological cancers and has been linked to cancer metastasis (57). FAK is up-regulated in many cancers and is involved in many aspects of cancer progression and along with CXCR4 may contribute to the metastatic potential of certain cancers (58, 59). For example, FAK is overexpressed along with CXCR4 in acute myelogenous leukemia, which when taken together is associated with overall poor survival (58, 59). Here, we used HeLa cells, a cell line derived from cervical cancer, which we have previously used to study CXCR4 trafficking and signaling mechanisms (22, 23, 28, 60, 61). CXCR4 expression is up-regulated in cervical cancer (62, 63), which likely contributes to its metastatic potential (25, 64). FAK is also up-regulated in cervical cancer, although β-arrestin1 and STAM1 expression appears to be unchanged (63). Our contribution here defines a novel mechanism by which CXCR4 activates FAK and chemotactic signaling, which may be relevant to the role CXCR4 plays in cancer.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture, Antibodies, DNA Constructs, and RNAi

HeLa cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in DMEM (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone Laboratories). The mouse monoclonal anti-Tyr(P)-397-FAK antibodies were from Invitrogen (catalog number 44-625G) and BD Biosciences (catalog number 611722). The anti-STAM1 (catalog number 12434-1-AP), anti-FAK rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog number 12636-1-AP) and anti-FAK mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog number 66258-1-Ig) were from ProteinTech Group (Chicago, IL). The anti-FLAG (catalog number F3165) and anti-ERK-1/2 (catalog number M8159) rabbit polyclonal antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich. The anti-Akt (catalog number 2967) and anti-Ser(P)-473-Akt (catalog number 9271) rabbit polyclonal antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Alexa Fluor-conjugated goat anti-mouse 635 (catalog number A31575) and goat anti-rabbit 594 (catalog number A11072) secondary antibodies were from Life Technologies. The anti-β-arrestin1/2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (178) was kindly provided by Jeffrey L. Benovic (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA). Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (also known as CXCL12) and EGF were from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and Protein Foundry (Milwaukee, WI). FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161) and FLAG-STAM1(296–380) were described previously (23). β-Arrestin1-GFP was kindly provided by JoAnn Trejo (University of California, San Diego). YFP-tagged β-arrestin1(25–161) was made by amplifying β-arrestin1 cDNA encoding amino acid residues 25–161 by PCR using the following primers harboring EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites, respectively: 5′-ATATGAATTCACGGGACTTTGTGGACCAC-3′ and 5′-ATATGGATCCCTACCGCTTGTGGATCTTCTCCTCCA-3′. The PCR product was digested and ligated into EcoRI and BamHI sites of pEYFP-C1 (Clontech) and transformed into competent Escherichia coli. Predesigned dicer substrate duplex siRNA against β-arrestin1 (ARRB1; catalog number HSC.RNAI.N020251.12.5) and FAK (PTK2; catalog number HSC.RNAI_N153831.12.1) were from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Negative control duplex siRNA against luciferase was from GE Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO; catalog number P-002099-01). The target sequence selected for design of the short hairpin STAM1 (shSTAM1) construct was based on the following siRNA against STAM1 from GE Dharmacon (siGENOME siRNA catalog number D-011423-01-0010), which we have used previously (23): 5′-GAACGAAGAUCCGAUGUAUUC-3′. This sequence corresponds to nucleotides 1340–1360 of STAM1 based on the cDNA sequence deposited in GenBank (accession number NM_003473). To make the shSTAM1 construct, forward and reverse DNA oligonucleotides, containing sense and antisense target sequences, separated by a 6-base pair linker sequence, were purchased from Fisher Scientific. The forward oligonucleotide sequence, with the sense and antisense regions underlined, was 5′-CCGGGAACGAAGATCCGATGTATTCCTCGAGGAATACATCGATCTTCGTTCTTTTTG-3′, harboring AgeI- and EcoRI-compatible restriction endonuclease sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The oligonucleotides were resuspended in sterile water to a final concentration of 20 μm. For annealing, 5 μl of each oligonucleotide was mixed in 1× reaction buffer (NEB-2, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and incubated at 95 °C for 4 min followed by 70 °C for 10 min and gradual cooling to room temperature spanning 3 h in a thermocycler. The annealed product was ligated into pLKO.1-TRC cloning vector (GE Dharmacon) digested with AgeI and EcoRI and transformed into competent E. coli. All DNA constructs were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing.

Chemotaxis Assay

To observe chemotactical responses in real time, we used μ-Slide chemotaxis 2D or 3D slides and time lapse microscopy. For DNA transfections, HeLa cells grown on 6-cm cell culture dishes were transiently transfected with 3 μg of empty vector (pCMV-10), FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161), FLAG-STAM1(296–380), empty shRNA vector (pLKO), or shSTAM1 using polyethylenimine (PEI; catalog number 23966, Polysciences, Warrington, PA) similarly to what we have described previously (29). For siRNA transfections, HeLa cells were grown on 6-cm cell culture dishes and transfected with siRNA (50 nm final concentration) against luciferase, β-arrestin1, or FAK using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours later, cells were trypsinized, counted, and diluted to 3 × 106 cells/ml in DMEM containing 1% FBS and 20 mm HEPES. Six microliters of cell suspension was applied to each of the three μ-slide cross channels following the manufacturer's instructions. The surface of the μ-slides (idiTreat) is comparable with a standard cell culture dish surface. The μ-slide was placed in a 10-cm dish with wet tissue placed around the slide to minimize evaporation and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 5 h to allow cells to attach. For the 2D chemotaxis μ-slides, the applied chemoattractant concentration at the source for CXCL12 was 50 nm, and for EGF it was 250 ng/ml. For the 3D chemotaxis μ-slides, the applied chemoattractant concentration at the source for CXCL12 was 40 nm, and for EGF it was 200 ng/ml. Chemotaxis was recorded by mounting the μ-slides onto an xy motorized microscope stage (Prior Scientific, Rockland, MD) attached to an IX83 inverted microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA) equipped with an incubation system (Tokai Hit, Japan) set to 37 °C and 5% CO2. Phase-contrast images of the three reservoirs were acquired every 30 min for 18 h using an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Hammamatsu, Japan) and 4×/0.13 NA (Olympus) objective lens driven by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Analysis of Chemotaxis

Movies were made from the images acquired in the chemotaxis assays and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Single cells were tracked by selecting the center of mass in each frame using the manual tracking and chemotaxis and migration plug-in tools from Ibidi for ImageJ. The manual tracking plug-in tracks single cell movement from frame to frame, whereas the chemotaxis and migration plug-in plots the track for each cell. A total of 50–100 cells were analyzed for each treatment condition. Cell movement was characterized by the forward migration index of single cells. The forward migration index was calculated as forward progress over the total path length parallel to the chemoattractant gradient. Forward migration index for the axis perpendicular to the gradient was also calculated, and it was close to zero (data not shown).

Signaling Experiments

HeLa cells grown on 10-cm cell culture dishes were transiently transfected with 10 μg of empty vector (pCMV-10 or pLKO), FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161), FLAG-STAM1(296–380), or shSTAM1 using PEI as described above. Transfections with siRNA targeting luciferase or β-arrestin-1 using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent were as described above. The next day, cells were trypsinized and counted, and 300,000 cells/well were seeded onto 6-well tissue culture plates. The following day, cells were serum-starved in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm HEPES for 4 h. Medium was aspirated and replaced with the same medium containing either vehicle (PBS with 0.1% BSA), 10 nm CXCL12, or 100 ng/ml EGF for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed once on ice with cold PBS and lysed in 300 μl of 2× sample buffer. Samples were sonicated, and equal amounts of lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Stimulation with Fibronectin and Poly-l-lysine

Stimulation with fibronectin (FN) and poly-l-lysine (PLL) was performed essentially as described by others previously (66). HeLa cells grown on 10-cm tissue culture dishes and transfected with empty vector (pCMV) or FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161) were serum-starved in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm HEPES for 3 h. Cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin, and the trypsin was inactivated with DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were washed once with DMEM containing 0.1% BSA and resuspended in the same medium. The cell suspension was kept at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were then seeded (1 × 106 cells) onto tissue culture dishes (6-well plates) that were left uncoated or coated with FN (10 μg/ml; catalog number F2006, Sigma) or PLL (100 μg/ml; catalog number P1399, Sigma) and incubated for 30 or 60 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and collected in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml pepstatin A). Equal amounts of cleared lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Cell Adhesion Assay

The cell adhesion assay was performed essentially as described by others previously (67). Tissue culture dishes (96-well plates) were coated with FN (10 μg/ml) for 10 min. The solution was aspirated, and wells were allowed to dry for 1 h. This was followed by adding 200 μl of 5% (w/v) heat-denatured BSA solution to each well for 2 h at room temperature. The solution was aspirated, and each well was washed once with 100 μl of PBS. HeLa cells transfected with pCMV-10 or FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161) were serum-starved for 3 h in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm HEPES and then stimulated with vehicle (PBS containing 0.1% BSA) or 10 nm CXCL12 for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin, washed, and seeded (4 × 105 cells/well) onto the FN-coated 96-well plate in triplicate and incubated for 10 or 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed three times in ice-cold PBS to remove non-adherent cells and then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde diluted in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed, and stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet solution made in 20% methanol for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS and solubilized in 100 μl of 20% (v/v) acetic acid. The absorbance was measured at 595 nm. Absorbance was normalized to the control group, pCMV-10-transfected group treated with vehicle and incubated on FN-coated wells for 10 min from three independent experiments.

Immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells transiently transfected with pCMV-10 or FLAG-β-arrestin1 and T7-STAM1 were serum-starved in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm HEPES for 3 h and stimulated with 30 nm CXCL12 for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and scraped into co-immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm NaF, 1 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml pepstatin A). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant (200 μg of total protein) was incubated with a polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody (1:200; Sigma) overnight at 4 °C while rocking. A 20-μl slurry of equilibrated protein A beads was added to each sample followed by incubation at 4 °C for 1 h while rocking. Proteins were eluted in 2× sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed essentially as described previously (68). HeLa cells were transfected with 5 μg each of β-arrestin1-GFP and T7-STAM1. The next day, cells were plated onto PLL (100 μg/ml)-coated glass coverslips (number 1.5) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Coating with PLL was necessary to ensure that cells were not displaced during the subsequent washing steps and because it did not have an impact on adhesion signaling (see Fig. 8B). The following day, cells were serum-starved in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm HEPES for 3 h. Medium was aspirated and replaced with the same medium containing either vehicle (PBS with 0.1% BSA) for 30 min or 10 nm CXCL12 for 30 or 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde diluted in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST). Cells were incubated in blocking buffer (5% goat serum in PBST) for 1 h at 37 °C. Following antibody titration experiments, cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-FAK and rabbit polyclonal anti-STAM1 (1:200 dilutions) antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C. After several washes, cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 or 635 (1:500 dilution) for 30 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were mounted onto slides using gold antifade reagent (catalog number 336939, Invitrogen). Images were acquired with a disc spinning unit confocal system configured with an IX83 inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Hammamatsu) and oil immersion 100×/1.40 NA (Olympus) objective lens driven by MetaMorph software. Image acquisition of parallel samples was performed under identical settings. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ. Merged RGB images were subjected to line scan analysis using the graphics/profile plug-in tool. For fluorescent image analysis, regions of interest (ROIs) from the FAK staining were selected. The colocalization between two different fluorescence signals was quantified using the nMDP (69). nMDP values were analyzed using the colocalization color map ImageJ plug-in, which is based on pixel to pixel analysis of two different fluorescence channels. Sixty selected ROIs throughout the entire cell were measured, and the results were normalized to the mean deviation of each pixel within each ROI.

FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 was examined by fluorescence microscopy. HeLa cells transfected with YFP-β-arrestin1(25–161) were plated onto PLL-coated glass coverslips. The next day, cells were serum-starved in DMEM containing 20 mm HEPES for 3 h followed by treatment with 30 nm CXCL12 for 5 or 30 min and vehicle for 30 min. For the FAK inhibitor experiment, HeLa cells grown on PLL-coated glass coverslips in serum-containing medium were treated with vehicle (DMSO), 1 μm PF573228 (catalog number sc-204179, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), or 1 μm PF562271 (catalog number sc-478488, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) for 3 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol for 10 min on ice, washed, and permeabilized with PBST for 7 min. To block nonspecific binding, cells were incubated with 5% BSA in PBST for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with a mouse monoclonal anti-Tyr(P)-397-FAK (BD Biosciences) antibody (1:1000 dilution) for 30 min at room temperature. After several washes, cells were incubated with an Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500 dilution) secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Images were acquired using an oil immersion 60×/1.35 NA (Olympus) objective. Image acquisition of parallel samples was performed under identical settings. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ. Intensity measurements were made in each field of view (FOV) by subtracting the background and autothresholding using the intermode method. ROI was selected, and the mean gray value was determined and normalized to the area (65). ROIs included whole cells or partial cells present in a FOV. Approximately 37 ROIs were analyzed from 20–30 FOVs per condition from two independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA).

Flow Cytometry Analysis of CXCR4 Surface Expression

CXCR4 surface expression was examined by flow cytometry as we have described previously (28). HeLa cells grown on 10-cm tissue culture dishes were transiently transfected using PEI with 10 μg of empty vector (pCMV-10) or FLAG-β-arrestin1(25–161) as described above. Twenty-four hours later, cells were detached from the dish surface with HyQTase (HyClone), seeded (1 × 106 cells) onto 6-cm tissue culture dishes, and incubated at 37 °C for ∼5 h to allow cells to adhere to the surface of the dish. Cells were then washed once with PBS and serum-starved in DMEM containing 20 mm HEPES for 1 h. Cells were treated with vehicle or 30 nm CXCL12 for 18 h, 1 h, or 5 min in the same medium. Cells were processed in parallel by detaching with HyQTase, washed once with PBS containing 0.1% BSA, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. After washing, cells were stained with a 1:100 dilution of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CXCR4 (catalog number 306506, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) or IgG2a κ-isotype (catalog number 400212, BioLegend) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS CANTO II, BD Biosciences). Mean fluorescence intensity was determined using FlowJo version 8 software (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA) and analyzed using GraphPad Prism.

Author Contributions

O. A. designed, performed, analyzed the experiments; prepared the figures; and wrote the paper. A. M. conceived and coordinated the study, analyzed the experiments, and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM106727 and GM106727-S1 (to A. M.). The authors declare the following patent (US8691188B2): Methods of Utilizing the Arrestin-2/STAM-1 Complex as a Therapeutic Target (to A. M.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- STAM

- signal-transducing adaptor molecule

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- ESCRT

- endosomal sorting complexes required for transport

- βArr1

- β-arrestin1

- nMDP

- normalized mean deviation product

- FN

- fibronectin

- PLL

- poly-l-lysine

- ROI

- region of interest

- NA

- numerical aperture

- FOV

- field of view

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- HRS

- HGF-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate.

References

- 1. Ridley A. J. (2011) Life at the leading edge. Cell 145, 1012–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peled A., Petit I., Kollet O., Magid M., Ponomaryov T., Byk T., Nagler A., Ben-Hur H., Many A., Shultz L., Lider O., Alon R., Zipori D., and Lapidot T. (1999) Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science 283, 845–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tachibana K., Hirota S., Iizasa H., Yoshida H., Kawabata K., Kataoka Y., Kitamura Y., Matsushima K., Yoshida N., Nishikawa S., Kishimoto T., and Nagasawa T. (1998) The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature 393, 591–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagasawa T., Hirota S., Tachibana K., Takakura N., Nishikawa S., Kitamura Y., Yoshida N., Kikutani H., and Kishimoto T. (1996) Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature 382, 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zou Y. R., Kottmann A. H., Kuroda M., Taniuchi I., and Littman D. R. (1998) Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature 393, 595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Müller A., Homey B., Soto H., Ge N., Catron D., Buchanan M. E., McClanahan T., Murphy E., Yuan W., Wagner S. N., Barrera J. L., Mohar A., Verástegui E., and Zlotnik A. (2001) Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature 410, 50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurley J. H., and Stenmark H. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of ubiquitin-dependent membrane traffic. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40, 119–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balkwill F. (2004) The significance of cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Semin. Cancer Biol. 14, 171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguyen D. X., Bos P. D., and Massagué J. (2009) Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 274–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith M. C., Luker K. E., Garbow J. R., Prior J. L., Jackson E., Piwnica-Worms D., and Luker G. D. (2004) CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 8604–8612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Busillo J. M., and Benovic J. L. (2007) Regulation of CXCR4 signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 952–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fong A. M., Premont R. T., Richardson R. M., Yu Y. R., Lefkowitz R. J., and Patel D. D. (2002) Defective lymphocyte chemotaxis in β-arrestin2- and GRK6-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7478–7483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun Y., Cheng Z., Ma L., and Pei G. (2002) Beta-arrestin2 is critically involved in CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis, and this is mediated by its enhancement of p38 MAPK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49212–49219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao K., McClatchy D. B., Shukla A. K., Zhao Y., Chen M., Shenoy S. K., Yates J. R. 3rd, and Lefkowitz R. J. (2007) Functional specialization of β-arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12011–12016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeFea K. A. (2013) Arrestins in actin reorganization and cell migration. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 118, 205–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma X., Espana-Serrano L., Kim W. J., Thayele Purayil H., Nie Z., and Daaka Y. (2014) β-Arrestin1 regulates the guanine nucleotide exchange factor RasGRF2 expression and the small GTPase Rac-mediated formation of membrane protrusion and cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13638–13650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Busillo J. M., Armando S., Sengupta R., Meucci O., Bouvier M., and Benovic J. L. (2010) Site-specific phosphorylation of CXCR4 is dynamically regulated by multiple kinases and results in differential modulation of CXCR4 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7805–7817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marchese A. (2014) Endocytic trafficking of chemokine receptors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 27, 72–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marchese A., Raiborg C., Santini F., Keen J. H., Stenmark H., and Benovic J. L. (2003) The E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 mediates ubiquitination and sorting of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4. Dev. Cell 5, 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marchese A., and Benovic J. L. (2001) Agonist-promoted ubiquitination of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 mediates lysosomal sorting. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45509–45512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henne W. M., Buchkovich N. J., and Emr S. D. (2011) The ESCRT pathway. Dev. Cell 21, 77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bhandari D., Trejo J., Benovic J. L., and Marchese A. (2007) Arrestin-2 interacts with the ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase atrophin-interacting protein 4 and mediates endosomal sorting of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36971–36979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malik R., and Marchese A. (2010) Arrestin-2 interacts with the endosomal sorting complex required for transport machinery to modulate endosomal sorting of CXCR4. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2529–2541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Asano S., Kitatani K., Taniguchi M., Hashimoto M., Zama K., Mitsutake S., Igarashi Y., Takeya H., Kigawa J., Hayashi A., Umehara H., and Okazaki T. (2012) Regulation of cell migration by sphingomyelin synthases: sphingomyelin in lipid rafts decreases responsiveness to signaling by the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 3242–3252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dillenburg-Pilla P., Patel V., Mikelis C. M., Zárate-Bladés C. R., Doçi C. L., Amornphimoltham P., Wang Z., Martin D., Leelahavanichkul K., Dorsam R. T., Masedunskas A., Weigert R., Molinolo A. A., and Gutkind J. S. (2015) SDF-1/CXCL12 induces directional cell migration and spontaneous metastasis via a CXCR4/Gαi/mTORC1 axis. FASEB J. 29, 1056–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sengupta R., Dubuc A., Ward S., Yang L., Northcott P., Woerner B. M., Kroll K., Luo J., Taylor M. D., Wechsler-Reya R. J., and Rubin J. B. (2012) CXCR4 activation defines a new subgroup of Sonic hedgehog-driven medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 72, 122–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paradis J. S., Ly S., Blondel-Tepaz É., Galan J. A., Beautrait A., Scott M. G., Enslen H., Marullo S., Roux P. P., and Bouvier M. (2015) Receptor sequestration in response to β-arrestin-2 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 governs steady-state levels of GPCR cell-surface expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E5160–E5168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malik R., Soh U. J., Trejo J., and Marchese A. (2012) Novel roles for the E3 ubiquitin ligase atrophin-interacting protein 4 and signal transduction adaptor molecule 1 in G protein-coupled receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9013–9027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Verma R., and Marchese A. (2015) The endosomal sorting complex required for transport pathway mediates chemokine receptor CXCR4-promoted lysosomal degradation of the mammalian target of rapamycin antagonist DEPTOR. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6810–6824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peng S. B., Peek V., Zhai Y., Paul D. C., Lou Q., Xia X., Eessalu T., Kohn W., and Tang S. (2005) Akt activation, but not extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation, is required for SDF-1α/CXCR4-mediated migration of epitheloid carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 3, 227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ryu C. H., Park S. A., Kim S. M., Lim J. Y., Jeong C. H., Jun J. A., Oh J. H., Park S. H., Oh W. I., and Jeun S. S. (2010) Migration of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells mediated by stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis via Akt, ERK, and p38 signal transduction pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 398, 105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Glodek A. M., Le Y., Dykxhoorn D. M., Park S. Y., Mostoslavsky G., Mulligan R., Lieberman J., Beggs H. E., Honczarenko M., and Silberstein L. E. (2007) Focal adhesion kinase is required for CXCL12-induced chemotactic and pro-adhesive responses in hematopoietic precursor cells. Leukemia 21, 1723–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le Y., Honczarenko M., Glodek A. M., Ho D. K., and Silberstein L. E. (2005) CXC chemokine ligand 12-induced focal adhesion kinase activation and segregation into membrane domains is modulated by regulator of G protein signaling 1 in pro-B cells. J. Immunol. 174, 2582–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schaller M. D., Hildebrand J. D., Shannon J. D., Fox J. W., Vines R. R., and Parsons J. T. (1994) Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2-dependent binding of pp60src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1680–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mitra S. K., Hanson D. A., and Schlaepfer D. D. (2005) Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 56–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fernandis A. Z., Prasad A., Band H., Klösel R., and Ganju R. K. (2004) Regulation of CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis and chemoinvasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 23, 157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schlaepfer D. D., Hauck C. R., and Sieg D. J. (1999) Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 71, 435–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barak L. S., Ferguson S. S., Zhang J., and Caron M. G. (1997) A β-arrestin/green fluorescent protein biosensor for detecting G protein-coupled receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27497–27500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kennedy J. E., and Marchese A. (2015) Regulation of GPCR trafficking by ubiquitin. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 132, 15–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeFea K. A. (2011) β-Arrestins as regulators of signal termination and transduction: how do they determine what to scaffold? Cell. Signal. 23, 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gurevich V. V., and Gurevich E. V. (2015) Analyzing the roles of multi-functional proteins in cells: the case of arrestins and GRKs. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50, 440–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meng D., Lynch M. J., Huston E., Beyermann M., Eichhorst J., Adams D. R., Klusmann E., Houslay M. D., and Baillie G. S. (2009) MEK1 binds directly to betaarrestin1, influencing both its phosphorylation by ERK and the timing of its isoprenaline-stimulated internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11425–11435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anthony D. F., Sin Y. Y., Vadrevu S., Advant N., Day J. P., Byrne A. M., Lynch M. J., Milligan G., Houslay M. D., and Baillie G. S. (2011) β-Arrestin 1 inhibits the GTPase-activating protein function of ARHGAP21, promoting activation of RhoA following angiotensin II type 1A receptor stimulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1066–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galet C., and Ascoli M. (2008) Arrestin-3 is essential for the activation of Fyn by the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells. Cell. Signal. 20, 1822–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nagaraj N., Wisniewski J. R., Geiger T., Cox J., Kircher M., Kelso J., Pääbo S., and Mann M. (2011) Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Naumann U., Cameroni E., Pruenster M., Mahabaleshwar H., Raz E., Zerwes H. G., Rot A., and Thelen M. (2010) CXCR7 functions as a scavenger for CXCL12 and CXCL11. PLoS One 5, e9175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rajagopal S., Kim J., Ahn S., Craig S., Lam C. M., Gerard N. P., Gerard C., and Lefkowitz R. J. (2010) β-Arrestin- but not G protein-mediated signaling by the “decoy” receptor CXCR7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 628–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Odemis V., Lipfert J., Kraft R., Hajek P., Abraham G., Hattermann K., Mentlein R., and Engele J. (2012) The presumed atypical chemokine receptor CXCR7 signals through G(i/o) proteins in primary rodent astrocytes and human glioma cells. Glia 60, 372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levoye A., Balabanian K., Baleux F., Bachelerie F., and Lagane B. (2009) CXCR7 heterodimerizes with CXCR4 and regulates CXCL12-mediated G protein signaling. Blood 113, 6085–6093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brami-Cherrier K., Gervasi N., Arsenieva D., Walkiewicz K., Boutterin M. C., Ortega A., Leonard P. G., Seantier B., Gasmi L., Bouceba T., Kadaré G., Girault J. A., and Arold S. T. (2014) FAK dimerization controls its kinase-dependent functions at focal adhesions. EMBO J. 33, 356–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jung O., Choi S., Jang S. B., Lee S. A., Lim S. T., Choi Y. J., Kim H. J., Kim D. H., Kwak T. K., Kim H., Kang M., Lee M. S., Park S. Y., Ryu J., Jeong D., et al. (2012) Tetraspan TM4SF5-dependent direct activation of FAK and metastatic potential of hepatocarcinoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 125, 5960–5973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brunton V. G., MacPherson I. R., and Frame M. C. (2004) Cell adhesion receptors, tyrosine kinases and actin modulators: a complex three-way circuitry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1692, 121–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lohi O., and Lehto V. P. (1998) EAST, a novel EGF receptor substrate, associates with focal adhesions and actin fibers. FEBS Lett. 436, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cleghorn W. M., Branch K. M., Kook S., Arnette C., Bulus N., Zent R., Kaverina I., Gurevich E. V., Weaver A. M., and Gurevich V. V. (2015) Arrestins regulate cell spreading and motility via focal adhesion dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 622–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ren X., Kloer D. P., Kim Y. C., Ghirlando R., Saidi L. F., Hummer G., and Hurley J. H. (2009) Hybrid structural model of the complete human ESCRT-0 complex. Structure 17, 406–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lobert V. H., Brech A., Pedersen N. M., Wesche J., Oppelt A., Malerød L., and Stenmark H. (2010) Ubiquitination of α5β1 integrin controls fibroblast migration through lysosomal degradation of fibronectin-integrin complexes. Dev. Cell 19, 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Balkwill F. R. (2012) The chemokine system and cancer. J. Pathol. 226, 148–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tavernier-Tardy E., Cornillon J., Campos L., Flandrin P., Duval A., Nadal N., and Guyotat D. (2009) Prognostic value of CXCR4 and FAK expression in acute myelogenous leukemia. Leuk. Res. 33, 764–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Siesser P. M., and Hanks S. K. (2006) The signaling and biological implications of FAK overexpression in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 3233–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Holleman J., and Marchese A. (2014) The ubiquitin ligase Deltex-3L regulates endosomal sorting of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 (1066.18). Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1892–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Slagsvold T., Marchese A., Brech A., and Stenmark H. (2006) CISK attenuates degradation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 via the ubiquitin ligase AIP4. EMBO J. 25, 3738–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fischer T., Nagel F., Jacobs S., Stumm R., and Schulz S. (2008) Reassessment of CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-2. PLoS One 3, e4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scotto L., Narayan G., Nandula S. V., Arias-Pulido H., Subramaniyam S., Schneider A., Kaufmann A. M., Wright J. D., Pothuri B., Mansukhani M., and Murty V. V. (2008) Identification of copy number gain and overexpressed genes on chromosome arm 20q by an integrative genomic approach in cervical cancer: potential role in progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47, 755–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang J. P., Lu W. G., Ye F., Chen H. Z., Zhou C. Y., and Xie X. (2007) Study on CXCR4/SDF-1α axis in lymph node metastasis of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 17, 478–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jensen E. C. (2013) Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat. Rec. 296, 378–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schlaepfer D. D., Jones K. C., and Hunter T. (1998) Multiple Grb2-mediated integrin-stimulated signaling pathways to ERK2/mitogen-activated protein kinase: summation of both c-Src- and focal adhesion kinase-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2571–2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Humphries M. J. (2001) Cell-substrate adhesion assays. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter9, Unit 9.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Marchese A. (2016) Monitoring chemokine receptor trafficking by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 570, 281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jaskolski F., Mulle C., and Manzoni O. J. (2005) An automated method to quantify and visualize colocalized fluorescent signals. J. Neurosci. Methods 146, 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]