Abstract

Insulin, a protein critical for metabolic homeostasis, provides a classical model for protein design with application to human health. Recent efforts to improve its pharmaceutical formulation demonstrated that iodination of a conserved tyrosine (TyrB26) enhances key properties of a rapid-acting clinical analog. Moreover, the broad utility of halogens in medicinal chemistry has motivated the use of hybrid quantum- and molecular-mechanical methods to study proteins. Here, we (i) undertook quantitative atomistic simulations of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin to predict its structural features, and (ii) tested these predictions by X-ray crystallography. Using an electrostatic model of the modified aromatic ring based on quantum chemistry, the calculations suggested that the analog, as a dimer and hexamer, exhibits subtle differences in aromatic-aromatic interactions at the dimer interface. Aromatic rings (TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, 3-I-TyrB26, and their symmetry-related mates) at this interface adjust to enable packing of the hydrophobic iodine atoms within the core of each monomer. Strikingly, these features were observed in the crystal structure of a 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin analog (determined as an R6 zinc hexamer). Given that residues B24–B30 detach from the core on receptor binding, the environment of 3-I-TyrB26 in a receptor complex must differ from that in the free hormone. Based on the recent structure of a “micro-receptor” complex, we predict that 3-I-TyrB26 engages the receptor via directional halogen bonding and halogen-directed hydrogen bonding as follows: favorable electrostatic interactions exploiting, respectively, the halogen's electron-deficient σ-hole and electronegative equatorial band. Inspired by quantum chemistry and molecular dynamics, such “halogen engineering” promises to extend principles of medicinal chemistry to proteins.

Keywords: diabetes, hormone, molecular dynamics, non-standard mutagenesis, quantum chemistry, diabetes mellitus, quantum mechanics, weakly polar

Introduction

Insulin, a small protein critical to metabolic homeostasis (1), provides a model for studies of protein folding and design (2) with long-standing application to human therapeutics (3). The hormone contains two chains, A and B (Fig. 1A), linked by two disulfide bridges (cystines A7–B7 and A20–B19); the A chain is further stabilized by cystine A6–A11. In pancreatic β-cells, insulin is stored within the secretory granules as zinc-coordinated hexamers. This study has exploited insulin semi-synthesis (4) (simplified through the use of norleucine (Nle)9 at position B29; arrow in Fig. 1A (5)) to investigate a site-specific modification of an aromatic ring by a single halogen atom (6). The modification, 3-iodo-Tyr at position B26 (3-I-TyrB26), is associated with enhanced binding to the insulin receptor (IR) (7–9). The general class of halo-aromatic modifications defines a key frontier of medicinal chemistry (10) and holds promise in the non-standard engineering of proteins through manipulation of π systems and weakly polar interactions (11, 12). In addition, the σ-hole of larger halogens can anchor interactions with surrounding polar groups and water molecules (13–19). 3-[iodo-TyrB26]Insulin thus provides a model for studies of engineered proteins at the border of molecular mechanics and quantum chemistry.

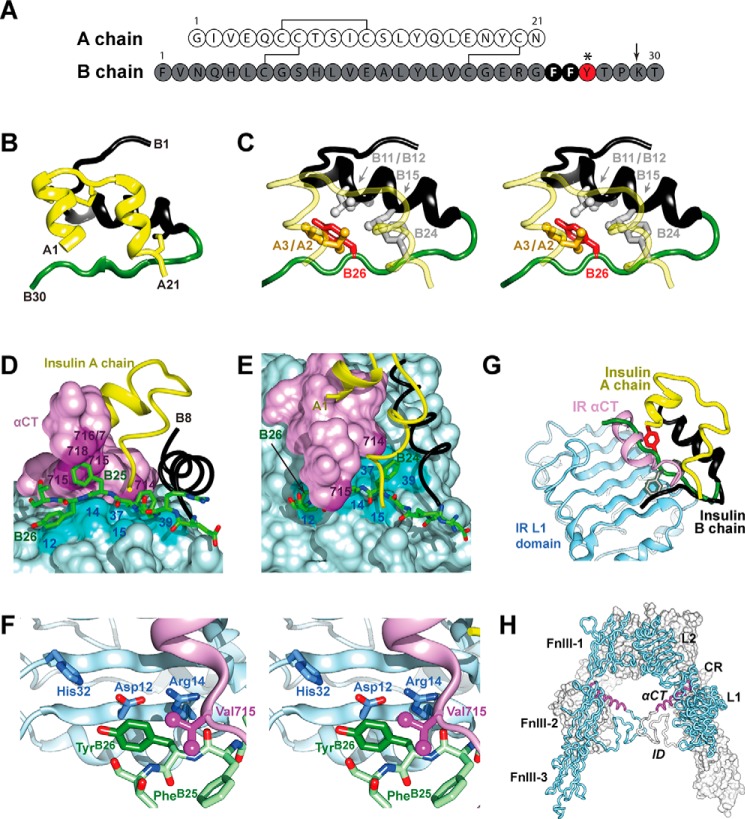

FIGURE 1.

Insulin sequence and structure. A, sequence of WT insulin and modification sites. A and B chains are shown in white and gray. Conserved aromatic residues PheB24 and PheB25 are highlighted as black circles. This study focused on substitutions of TyrB26 (red circle); additional substitutions were made at position B29 (Nle; arrow) to facilitate semi-synthesis. B, ribbon model of insulin monomer (T state extracted from T6 zinc hexamer) (2). The A chain is shown in yellow and the B chain in black (B1–B19) and green (B20-B30). C, environment of TyrB26 (stereo). The side chain of TyrB26 is highlighted in red; IleA2, ValA3, ValB12, LeuB15, and PheB24 are as labeled. D, stick representation of residues B20–B27 (carbon atoms (green), nitrogen atoms (blue) and oxygen atoms (red)) packed between αCT and the L1-β2 sheet. B chain residues B8–B19 are shown as a black ribbon and the A chain as a yellow ribbon; residues A1–A3 are concealed behind the surface of αCT. Key contact surfaces of αCT with B24–B26 are highlighted in magenta, and L1 with B24–B26 are highlighted in cyan; L1 and αCT surfaces not in interaction with B24–B26 are shown in lighter shades. E, orthogonal view to D, showing interaction of the side chain of PheB24 with the nonpolar surface of the L1-β2 sheet. TyrB26 is hidden below the surface of αCT. Engagement of conserved residues A1–A3 against the nonpolar surface of αCT is shown at top. F, environment of TyrB26 within site 1 complex (stereo). Neighboring side chains in L1 and αCT are as labeled. Coordinates were obtained from PDB code 4OGA (39). G, model of wild-type insulin in its receptor-free conformation overlaid onto the structure of the insulin-bound μIR (71). The L1 domain and part of CR domain are shown in powder blue; αCT is shown in purple. Residues PheB24 and TyrB26 are as in A. The B chain of μIR-bound insulin is shown in dark gray (B6–B19); the brown tube indicates classical location within the overlay of residues B20–B30 of insulin in its receptor-free conformation, highlighting steric clash of B26–B30 with αCT. In the μIR co-crystal structure, insertion of the insulin B20–B27 segment between L1 and αCT peptide is associated with a small rotation of the B20–B23 β-turn and changes in main-chain dihedral angles flanking PheB24 (39). H, inverted V-shaped assembly of IR ectodomain homodimer. One monomer is in ribbon representation (labeled), the second in surface representation. Domains are labeled as follows: L1, first leucine-rich repeat domain; CR, cysteine-rich domain; L2, second leucine-rich repeat domain; FnIII-1, -2, and -3, first, second, and third fibronectin type III domains, respectively; ID, insert domain; and αCT, α-chain C-terminal segment. Coordinates were obtained from PDB code 4ZXB (42).

Crystal structures of insulin (as zinc-free dimers (20) or zinc-stabilized hexamers (21–23)) provide a foundation for its therapeutic formulation (24) and analysis of structure-activity relationships (2, 25, 26). The structure of a monomer in solution (27–30) resembles a crystallographic protomer (as in zinc-free T2 dimers or T6 zinc hexamers) (Fig. 1B); this “closed” conformation contains an α-helical globular subdomain and tethered C-terminal B-chain β-strand (residues B24–B28). TyrB26 (red in Fig. 1A, asterisk) provides a key contact between the β-strand and the α-helical subdomain (Fig. 1C). The contribution of this side chain to the stability of the insulin monomer has recently been investigated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (31) and mutagenesis (32).

Insulin undergoes a change in conformation to “open” on receptor binding (33–37). A recent structural advance exploited domain-minimized models of the α-subunit of the insulin receptor (IR) (38) containing the primary insulin-binding elements (leucine-rich domain 1 (L1) and the C-terminal segment of the α-subunit (αCT)) (39). A co-crystal structure has been determined at 3.5 Å resolution of a ternary complex involving insulin, an L1-CR fragment, and a synthetic αCT peptide (residues 704–719 of receptor isoform A (IR-A)) (39).10 In this structure (designated the micro-receptor (μIR) complex), the C-terminal segment of the insulin B chain is detached from the hormone's α-helical core; such detachment enables its insertion between L1 and αCT (Fig. 1D). The inserted segment includes a conserved triplet of aromatic residues (PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26) that lie at the μIR interface (39). Whereas PheB24 packs within a classical nonpolar pocket, TyrB26 lies at one edge (Fig. 1D and 90° rotated view in Fig. 1E). An expanded view of the TyrB26 environment in the μIR (Fig. 1F) highlights contacts to conserved residues within L1 (Asp-12, Arg-14, and His-32) and αCT (Val-715). These contacts require repositioning of the C-terminal segment of the insulin B chain from its unbound conformation (green in Fig. 1G) in the μIR complex (black), thereby avoiding a clash between B25–B30 and αCT (purple). The L1 and αCT elements of the ectodomain belong to different α-subunits within the multidomain (αβ)2 IR dimer (Fig. 1H). Binding of insulin in trans to these elements may alter the orientation between the αβ-subunits as the first step in signal propagation (40–42).11

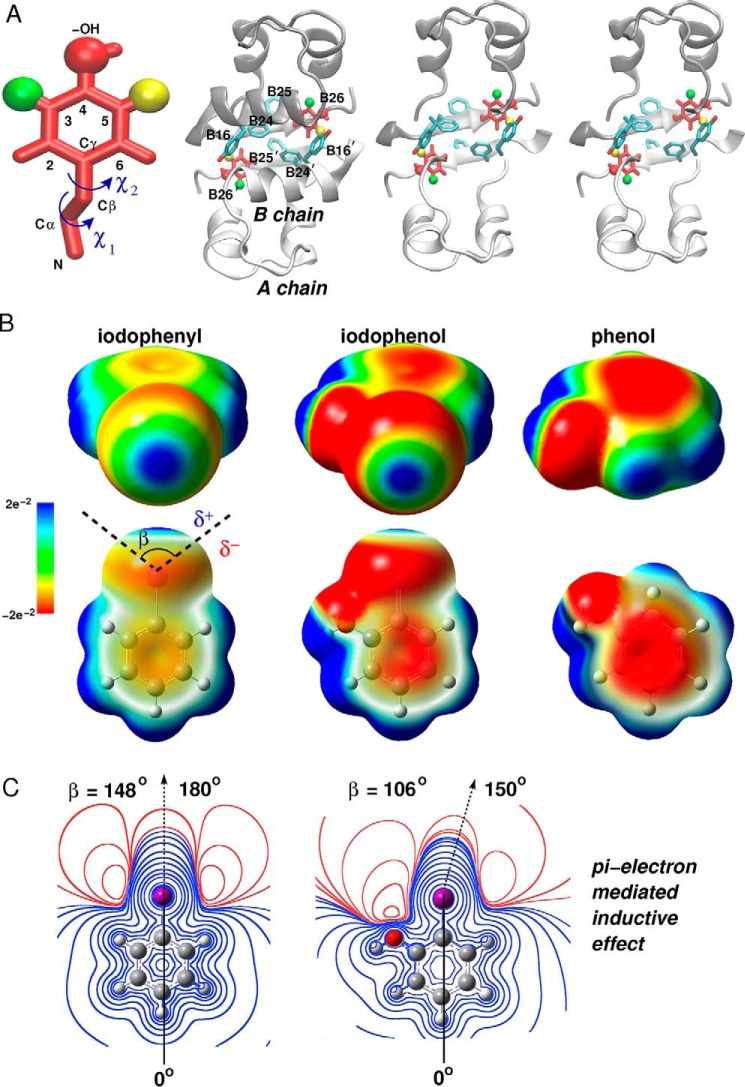

Insulin's dimer interface is remarkable for aromatic-aromatic interactions across eight aromatic side chains (TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, TyrB26, and their symmetry-related mates (2, 43)). In this cluster, the side chain of TyrB26 packs against PheB24 and the dimer-related side chains of TyrB16′ and PheB24′ (where ′ indicates that the residue belongs to the alternate monomer within the dimer; Fig. 2A), giving rise to complex and asymmetric electrostatic environments (44). Halogen substitutions within these rings would be expected to alter the distribution of π electrons and so modulate such interactions (Fig. 2B). In addition, the tyrosine's para-OH group would be expected to cause subtle differences in iodine's inductive effects (Fig. 2C). Given these features, the present study focused on the effects of iodination of TyrB26, long known to enhance the affinity of insulin for the IR (7–9) and recently shown to enhance the pharmaceutical properties of a rapid-acting clinical analog, including its stability and resistance to physical degradation (45).12 Such findings raise salient questions regarding the role of the iodo-aromatic modification on the structure of the free hormone and its potential role at the hormone-receptor interface.

FIGURE 2.

Quantum chemistry of iodo-aromatic system. A, Tyr side chain with iodine in its 3- or 5-ring position (green and yellow, in and out, respectively) with carbon-atom positions labeled. Rotation angles for rigid-body modeling involve rotations around the Cα–Cβ bond (χ1) and Cβ–Cγ bond (χ2). The insulin dimer with B26 side chains (red) and side chains of TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, and their dimer-related mates (blue). The right-hand side provides a cross-eyed stereo view of the modified dimer with the B chain helix removed for clarity. B, electrostatic potential (ESP) surface maps of phenol, iodophenol, and iodophenyl at the 0.001 e bohr−3 isodensity. The color scale of the surface potential ranges from −2.12 e−2 (red) through 0 (green) to 2.12 e−2 (blue). In the upper row the iodine (facing the viewer) exhibits the effect of the electron-donating –OH on the σ-hole. The lower row shows effects of iodine on the π-system of the phenol ring. In the 1st row the surface is opaque, and in the 2nd row the surface is transparent. Angle β represents the σ-hole size as delimited by black dashed lines. δ+ and δ− represent respective regions of positive and negative charge around the iodine. C, ESP contours of iodophenyl (left) and 2-iodophenol (right), at different isovalues, calculated in the plane of the aromatic ring. The halogen boundary represents a region of an electron isodensity of 10−3 e bohr−3 (111). Isocontours in the left and right panels are at the same heights but in uneven separations. The σ-hole size, defined by an angle β (B), was calculated from the angular profile of the ESP on the intersection line of the 2D grid and halogen boundary where the ESP changes its sign (55); positive ESP and negative ESP regions are shown in blue and red, respectively. The black dashed arrow indicates directionality of the C–I bond.

How might iodination of an aromatic residue affect its electrostatic properties and in turn its conformation? What would be the preferred molecular environment of the iodine, and how might its quantum-chemical features be exploited? In particular, how might the asymmetric electronic distribution of the iodo-substituent, in principle capable of halogen bonding (46, 47) and/or halogen-directed hydrogen bonding (18, 48, 49), affect weakly polar interactions within the protein (44)? To what extent might these chemical features underlie the improved biochemical or biophysical properties of such a modified protein? We addressed these questions in three parts. Our study began with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin with multipolar parameters derived from quantum-mechanical (QM) modeling of the halogenated side chain. We next verified predicted features of such models by determining the crystal structure of a 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin analog, herein described as an R6 zinc insulin hexamer. The final part of this study sought insight into potential mechanisms by which 3-I-TyrB26 enhances IR binding (7–9). Together, our results highlight the promise of non-standard protein engineering guided by molecular mechanics at the interface of quantum chemistry.

Results

Rigid-body Modeling Distinguished Opposite Edges of the B26 Aromatic Ring

Past 1H NMR studies of insulin as an R6 zinc hexamer (50, 51) or engineered T2 dimer (52) demonstrated that all Phe and Tyr side chains exhibit equivalent meta resonances (ring positions 3 and 5 as defined in Fig. 2A, left) and likewise equivalent ortho resonances (positions 2 and 6). These observations indicated that the aromatic rings either freely rotate (as do PheB1 and TyrA14) or undergo rapid 180° “flips” about the Cβ–Cγ bond axis (<1 ms on the NMR time scale; TyrA19, TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26). Because within the native state the latter rotations would incur steric clashes, such 1H NMR features reflect the flexibility of the surrounding protein framework (50).

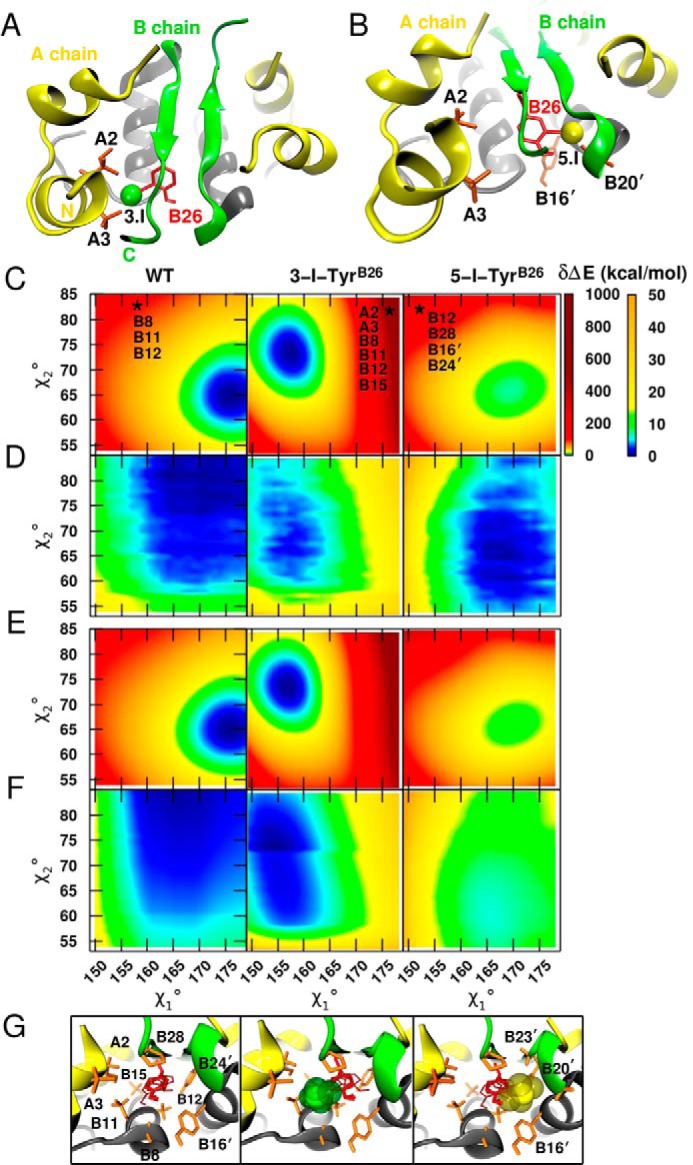

Respective ortho and meta positions of 3-I-Tyr are in principle not equivalent. Accordingly, which of the two B26 conformations, i.e. with the iodine “in” or “out” with respect to the core of a monomer, is preferred? In either orientation, the iodine atom would be inaccessible to solvent within a nonpolar environment. Naive modeling of the insulin dimer suggested that either conformation would encounter marked steric occlusion as follows: at the 3-position (in), an iodine would overlap with the γ-CH3 of IleA2 and one γ-CH3 of ValA3 (Fig. 3A), whereas at the 5-position (out) it would encounter the side chain of dimer-related TyrB16 and carbonyl oxygen of GlyB20 (Fig. 3B). The seeming steric incompatibility of either 3-I-TyrB26 or 5-I-TyrB26 in naive models (akin to seeming steric barriers to ring rotation) stood in contrast to its observed stabilization of an insulin analog (5), suggesting that structural accommodation at one or the other sites is feasible and without free-energy penalty.

FIGURE 3.

Rigid-body modeling of 3- and 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin analogs. A, naive model of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin highlights overlap of the iodine with the side chains of IleA2 and ValA3. B, analogous model of 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin exhibits clash with TyrB16′ and the backbone oxygen atom of GlyB20′. This view is slightly tilted relative to that in A to better illustrate the unfavorable contacts. C, conformational rotational maps for a PC representation of the B26 side chain around dihedral angles χ1 and χ2 for WT (left), 3-I-TyrB26 (middle), and 5-I-TyrB26 (right). The two energy scales highlight large (0–1000 kcal/mol) and finer energy differences (0–50 kcal/mol) relative to the global minimum. The zero of energy for WT and 3-I-TyrB26 is at 0 kcal/mol, whereas the minimum for 5-I-TyrB26 is relative to that of 3-I-TyrB26. The stars indicate one of the (χ1,χ2) conformations leading to severe steric clashes with neighboring residues. The geometries are at 〈157°, 84°〉, 〈176°, 83°〉, and 〈151°, 84°〉 for WT, 3-I, and 5-I, respectively, and the clashing residues are listed. D is as in C but for a relaxed scan over the (χ1,χ2) grid. The panels show only energies covering χ1 and χ2 intervals common to the three dimers as follows: [149°, 180°] for χ1 and [53°, 85°] for χ2. E and F contain respective rigid and relaxed conformational rotational maps for an MTP representation of the B26 side chain. G, corresponding structures in the neighborhoods of residue B26 (transparent red) highlighting residues affected by dihedral rotations of B26 (orange): left to right, WT insulin, 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin model, and 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin model.

To evaluate the two competing modes of iodo-Tyr packing, we first explored potential local accommodation by considering B26 (χ1,χ2) energy maps in the neighborhood of the native structure. Insight was obtained through the use of increasingly realistic models as follows: first, a conventional point charge (PC (53)) model, and second, an improved representation based on electrostatic multipoles (MTP (54)) as parameterized by ab initio quantum-chemical calculations (see “Experimental Procedures”). We then explored potential interplay of local and non-local mechanisms using MD simulations based on MTPs for the modified side chain. The latter captured essential aspects of quantum chemistry without incurring the computational burden of explicit mixed quantum mechanical/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations. These results are described in turn.

Residue-specific Energy Maps Suggest Local Accommodation Is Possible

For a given representation (PC or MTP) of the B26 side chain, its conformation-dependent empirical energy was first assessed within a rigid protein environment (“unrelaxed maps”). Subsequent energy minimization at each B26 (χ1,χ2) setting allowed local structural reorganization of neighboring side chains, yielding the corresponding “relaxed maps.” Comparison of unrelaxed (Fig. 3, C and E) and relaxed (Fig. 3, D and F) maps suggested that local steric clashes could be mitigated. Comparison of respective PC- and MTP-based maps informed the extent to which such mitigation is influenced by electrostatic features of the iodo-aromatic system.

Representation of Residue B26 by a PC Model

A first step toward distinguishing between “in” and “out” isomers was provided by rigid-body calculations assuming either 3-I-TyrB26 (green position in Fig. 2A) or 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin (yellow position in Fig. 2A); in the context of WT insulin, the 3-I and 5-I isomers, respectively, correspond to “iodo-in” and “iodo-out” conformations. To this end, unrelaxed (χ1,χ2) energy maps in the neighborhood of the WT structure (±15 in each dihedral angle in steps of 1°) were computed using a conventional PC representation for three B26 side chains (unmodified TyrB26, 3-I-TyrB26, and 5-I-TyrB26; left to right in Fig. 3C). This representation neglected known anisotropic electrostatic features around halogens (48) and their perturbation by the neighboring para-OH group (Fig. 2C) (18, 55). The shared energy scale of the 3-I and 5-I maps cannot be directly compared with that of WT.

Despite the PC approximation, comparison of qualitative features was informative. (a) Consistent with naive modeling, violations (red regions in Fig. 3C) are more severe for the iodinated residues than for the unmodified residue. (b) WT- and 5-I-TyrB26 maps are similar in overall topography; in each case a hydrogen atom at the 3-position points toward the crowded core of the same monomer. (c) Surprisingly, in this particular “frozen” protein environment, 3-I-TyrB26 appears to be energetically favored over 5-I-TyrB26. (d) Despite its lower minimum, the 3-I basin is considerably narrower, especially with respect to χ1 rotation, than is the 5-I basin (or that of the unmodified residue; Fig. 3C). The “walls” of this narrow basin were enforced largely by steric clashes with neighboring side chains (IleA2, ValA3, IleB11, ValB12, LeuB15, and ProB28; Fig. 3G).

To quantify the effects of relaxing the protein environment on the B26 energy maps, corresponding (χ1,χ2) scans were obtained in which the positions of surrounding side chains were energy-minimized (Fig. 3D). As in the unrelaxed calculations, the relaxed 5-I-TyrB26 energy map was similar to that of the unmodified residue. Although the severe clashes found for 3-I-TyrB26 were largely mitigated due to local adjustments, the relaxed PC-based maps predicted that in an insulin dimer the outward positioning of the iodine atom (5-I-TyrB26) would be preferred by 1.3 kcal/mol relative to the 3-I-TyrB26 isomer. Relaxation of neighboring side chains in the PC model thus reversed the predicted orientation of the iodinated ring from in to out. The 5-I basin also remained wider than that of 3-I.

Although the PC-predicted outward conformation of the iodine atom seemed intuitive given the narrow confines of the hydrophobic core and inferred flexibility of the dimer interface (56–59), we next sought to test whether this prediction remained valid using a more rigorous representation of the halogenated side chain.

Representation of Residue B26 by an MTP Model

Given the limitations of a PC-based force field, we employed an MTP representation of iodo-Tyr parameterized as follows. The electrostatic potential of ortho-iodophenol was mapped as a model compound (Fig. 2B). The electron-donating property of the para-hydroxyl group in iodophenol led to a partial attenuation of iodine's σ-hole together with an increase in its negative equatorial potential region (δ−; Fig. 2B) relative to phenol. The electron-attracting property of the iodine induces non-local decrease of the planar δ− π-system above and below the plane of the ring.

The unrelaxed MTP energy maps (Fig. 3E) validated aspects of the PC calculations (Fig. 3C). The WT and 5-I maps were similar to one another, and the 3-I minimum was again found to be more favorable than that of 5-I-TyrB26 but with a narrower basin. In striking contrast to the PC-based calculations, however, the relaxed MTP energy map (Fig. 3F) predicted the 3-I minimum remained lower than that of 5-I, in this case by 5 kcal/mol. Hence, the more accurate electrostatic model (MTP) led to a preferred position of the iodine in seeming contradiction to our initial intuition.

B26 Interaction Energy Analysis

To understand the physical origins of the MTP prediction, interaction energies between B26 and the neighboring dimer-related residues were analyzed for the most energetically favorable 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin and 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin dimer structures. Both PC and MTP electrostatic models were employed (supplemental Table S1). The results suggested that, relative to the 5-I orientation, the 3-I conformation provides both (i) favorable hydrophobic interactions with the side chains of IleA2, ValA3, LeuB11, ValB12, LeuB15, and ProB28; and (ii) favorable aromatic-aromatic interactions distant from the halogen (PheB16′ and PheB24′). Attractive, weakly polar interactions between 3-I-TyrB26 and GlyB8 are also possible. In contrast, 5-I-TyrB26 engages in favorable interactions only in the immediate neighborhood of the iodine, and only with the ends of a solvent-exposed and flexible β-turn (GlyB20′ and GlyB23′). These key differences rationalize why an inward conformation is preferred despite our initial expectation.

Multipole-based MD Simulations Predicted Structural Features of an Iodinated Insulin Analog

Side-chain conformations were further probed by analyzing 20 ns of four MTP-based MD simulations as follows: the WT and 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin dimers, each in R2 or T2 states (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2, respectively). Initial coordinates were obtained from PDB entries 1DPH (T2) and 1ZNJ (as extracted from a WT R6 zinc insulin hexamer). We first analyzed respective (χ1,χ2) occupancies, P(χ1,χ2), of residues TyrA19, TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26. Of these, A19 provided a probe of the α-helical core within component protomers, whereas B16 and B24–B26 provided probes of the asymmetric dimer interface. The resulting dihedral angle distributions P(χ1,χ2) demonstrated that these side chains each adopted conformations consistent with experiments (see symbols in supplemental Figs. S1 and S2) with the exception of PheB25 (whose variable conformation and asymmetry across the dimer interface have previously been noted (2)). P(χ1,χ2) plots were similar whether the MTP-based MD simulations used T2 or R2 starting structures, except for PheB25 (which agreed better with crystal structures when starting from the R2 dimer).

3-I-TyrB26 Trajectories

Each subunit exhibited similar features with optimal positioning of the iodine atom requiring a change in B26 side-chain conformation (Δχ1 = 10(±3°) and Δχ2 = 5(±8°); supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Despite this change, the aromatic face of 3-I-TyrB26 adjoined the side chain of ValB12 as in WT insulin (supplemental Fig. S3A). MTP-based MD simulations established that the 3-I-TyrB26 side chain could pack within a hydrophobic cavity formed by the side chains of IleA2, ValA3, LeuB11, and ValB12 (and the main chain of GlyB8) within the same protomer (supplemental Fig. S3B). The predicted environment of 3-I-TyrB26 and its range of conformational excursions were similar in R2- and T2-based MD simulations.

The modified aromatic ring of 3-I-TyrB26 represents a perturbation within an anti-parallel dimer-related β-sheet. The subtle changes in the side-chain dihedral angles of 3-I-TyrB26 and 3-I-TyrB26′ observed in the crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]insulin (see below; relative to TyrB26 and TyrB26′ in WT R6 hexamers) do not affect this sheet; its four dimer-related hydrogen bonds exhibit essentially native lengths and angles. Packing at the dimerization interface for the WT dimer (supplemental Fig. S4A) and comparison with the predicted 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin dimer show that the iodine within each protomeric core within the R6 hexamer would (a) provide an overall nonpolar environment and (b) enable formation of a novel and favorable electrostatic interaction (supplemental Fig. S4B) between the para-OH of TyrA19 and the equatorial belt surrounding the halogen (Fig. 2B). No halogen bonds were observed to the σ-hole of the iodine (supplemental Fig. S4B).

5-I-TyrB26 Trajectories

MTP simulations of the alternative 5-I-TyrB26 ring conformation suggested that it could achieve more compact packing at the dimer interface than was observed for WT or 3-I-TyrB26 simulations (supplemental Fig. S3C). The simulations further verified the implications of the MTP energy maps that unfavorable steric and electrostatic interactions across the dimer interface render unfavorable 5-I-positioning of the iodine atom. The clash between the 5-iodine and the dimer-related side chain of TyrB16 could not be relieved by displacement of B16 because it itself is constrained by ValB12′ and PheB25 (supplemental Fig. S3C). Although a clash between the 5-iodine and the dimer-related carbonyl oxygen of GlyB20 could readily be relieved by a change in B20 main-chain dihedral angles (supplemental Fig. S5), the resulting B20 conformations (with negative φ angles in the Ramachandran plane) are less favorable (60). Previous studies of synthetic insulin analogs have shown that reinforcement of the native positive φ angle by d-AlaB23 stabilizes insulin, whereas perturbation of the B23 conformation by l-Ala or l-Val (the latter associated with human diabetes) is associated with structural frustration and misfolding (60, 61).

The robustness of the MTP-MD simulations was probed through average r.m.s.d. on pairwise comparisons of the conformations sampled in the course of 20-ns trajectories. The values given in Table 1 pertain to side chains at the dimer interface (residues B24, B25, and B26) following alignment based on the main-chain atoms of residues B24–B28 and B24′–B28′. Baseline r.m.s.d. values in the WT T2 dimer (PDB code 1DPH) were calculated following a control MD simulation (i.e. in the absence of a modified B26). For residues in the WT anti-parallel β-sheet (residues B24–B28 and their dimer-related mates), the average main-chain r.m.s.d. was 0.1 Å, and the average side-chain r.m.s.d. was 0.3 Å relative to starting structure (Table 1). Corresponding values for the modified T2 dimer were 0.3 and 0.9 Å, also relative to the WT crystal structure; similar values were obtained on comparison of the modified R2 dimer. The larger r.m.s.d. values in the modified dimers reflected consistent conformational adjustments required to accommodate core packing of the iodine atom in the 3-I conformation.

TABLE 1.

Average r.m.s.d. across dimer interface

Average r.m.s.d. across the WT-T2, 3I-TyrB26 T2, and R2 dimer interface from 20 ns of MD simulation and from the three dimers (D1, D2, and D3) taken from the 3-I-TyrB26 R6 crystal structure, with respect to WT (PDB code 1DPH). All structures are aligned with respect to the backbone atoms of residues B24–B28 and B24′–B28′. Values reported are r.m.s.d. of the side chains of residues B24–B26 and B24′–B26′.

| Comparison | r.m.s.d. (Å) |

|---|---|

| WT1DPH/WT (20 ns MD) | 0.3 |

| WT1DPH/T2 3-I-TyrB26 (20 ns MD) | 0.9 |

| WT1DPH/R2 3-I-TyrB26 (20 ns MD) | 1.0 |

| WT1DPH/D1 of R6 3-I-TyrB26 X-ray | 0.7 |

| WT1DPH/D2 of R6 3-I-TyrB26 X-ray | 0.7 |

| WT1DPH/D3 of R63-I-TyrB26 X-ray | 0.7 |

Crystal Structure Verifies Essential Features of MTP Modeling

3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin exhibited an affinity (Kd) for the lectin-purified receptor (isoform IR-B) of 21 ± 5 pm under conditions in which WT insulin exhibits an affinity of 62(±8) pm. The analog's stability (ΔGu = 3.4(±0.1) kcal/mol at 4 °C) was indistinguishable from that of [NleB29]insulin as probed by guanidine denaturation (32).

The analog was crystallized under conditions that ordinarily facilitate crystallization of WT insulin as a phenol-stabilized R6 hexamer (23). A monoclinic lattice was observed in which one R6 hexamer defined the asymmetric unit (for refinement statistics, see Table 2). In this crystal form, each protomer in the hexamer is crystallographically independent (and so may in principle exhibit subtle structural differences). A ribbon model (Fig. 4A) highlights the positions of the iodine atoms (green spheres) relative to the six R state-specific B1-B19 α-helices (green) and A chains (black). We first describe the structure and then compare it to the predicted models.

TABLE 2.

X-ray data processing and refinement statistics

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5478 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.85–2.30 (2.40–2.30)a |

| Space group | P21 |

| a (Å), b (Å), c (Å), β (°) | 46.43, 61.63, 58.58, 111.38 |

| Redundancy | 4.76 (2.55) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.6 (80.4) |

| Rmerge | 0.054 (0.227) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 18.2 (3.9) |

| CC1/2b | 0.999 (0.934) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.85–2.30 |

| No. of reflections | 13,255 |

| Rwork/Rfreec | 0.163/0.228 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2305 |

| No. of non-protein atoms | 121 |

| 〈Biso〉 protein atoms (Å2) | 41.6 |

| 〈Biso〉 non-protein atoms (Å2) | 34.0 |

| σbonds (Å)/σangles (°) | 0.008/1.12 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 100 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 |

a Numbers in parentheses refer to the outer resolution shell.

b Pearson correlation coefficient between merged intensities of two random halves of the diffraction data set (112).

c Free set contained 10% of total observed reflections.

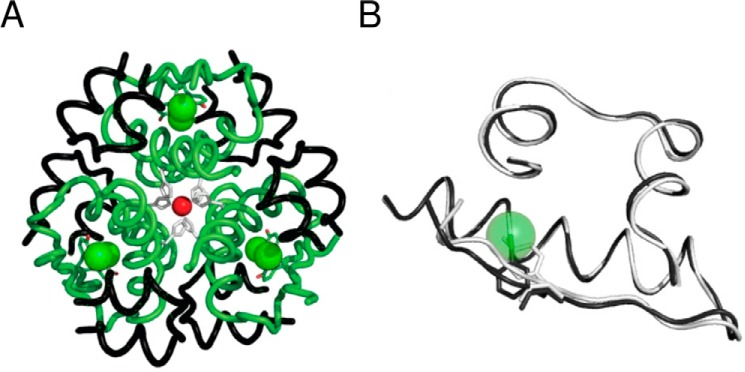

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin. A, R6 hexamer with A and B chains (black and green ribbons, respectively). Iodine atoms (green spheres) and the two axial zinc ions (red spheres) are aligned at center, each coordinated by 3-fold-related HisB10 side chains (light gray). B, superposition of WT protomer (light gray) and 3-I-TyrB26 analog (dark gray). Side chains of TyrB26 and 3-I-TyrB26 are shown as sticks. For clarity, the iodine atom is shown as a transparent sphere; NleB29 is not shown.

Crystal Structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin Resembles the WT Hormone

No significant differences were observed between the modified hexamer and the corresponding WT R6 hexamer with respect to secondary structure, chain orientation, mode of assembly, or structures of the Zn2+- and phenol-binding sites. The six independent R state protomers exhibited essentially identical conformations (average pairwise main-chain r.m.s.d. of 0.42 Å and average side-chain r.m.s.d. of 1.43 Å). Tetrahedral coordination of the two axial zinc ions (overlying red spheres at center in Fig. 4A) by the side chains of HisB10 (three per R3 trimer; light gray side chains) is essentially identical to that in WT R6 hexamers (62); the fourth coordination sites contain a presumed chloride anion. In each protomer, the B26 iodine atom is positioned within the α-helical core in accordance with the 3-I-conformational isomer. No excess electron density was observed at ring position 5, providing evidence of a single predominant conformation.

Superposition of a representative analog protomer and WT protomer (dark and light gray ribbons, respectively, in Fig. 4B) yielded the following average pairwise differences between a representative protomer of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin and the WT R state: main-chain r.m.s.d. = 0.55(±0.08) Å and side-chain r.m.s.d. = 1.94(±0.23) Å. These values are similar to those observed among a collection of independent WT R state protomers13 (main-chain r.m.s.d. 0.68(±0.26) Å; side-chain r.m.s.d. 1.14(±0.34) Å). Within the crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin, no polypeptide-like (2Fobs − Fcalc) electron density (continuous at >1σ) was observed C-terminal to B28 in any of the modified B chains.

The similarity of the variant and WT structures suggests that the essential features required for dimer formation are not altered by the asymmetric distribution of partial charges in the aromatic ring of 3-I-TyrB26 and its associated pattern of aromatic-aromatic interactions (supplemental Fig. S4C). The six independent side chains of 3-I-TyrB26 nonetheless exhibit consistent differences in conformation relative to WT TyrB26 (supplemental Fig. S4D). The modified side chain (dark gray in supplemental Fig. S4D) is rotated by ∼12° about the Cα–Cβ bond with respect to its WT counterpart (light gray in supplemental Fig. S4 D). As predicted by the MTP-based calculations, this rotation positions the iodo-group within a non-polar pocket formed by the side chains of residues IleA2, ValA3, LeuB11, and ValB12, residues conserved among vertebrate insulins and essential for biological activity (2). In the WT structure, the pocket is occupied by the phenolic hydroxyl group of TyrB26, although its packing within the pocket is less intimate than that of the iodine atom of 3-I-TyrB26. The consequent displacement of the para-hydroxyl group of 3-I-TyrB26 from the pocket results in its greater solvent exposure. Side-chain dihedral angles of three aromatic side chains at or near the dimer interface (B16, B24, and B26) are given in Table 3 in relation to a reference WT R6 structure.

TABLE 3.

Side-chain dihedral angles of aromatic side chains near dimer interface

PheB25 has been excluded due to poor side-chain density found in the crystal structure.

| Residue | 3-I-TyrB26 |

WT insulina |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ1 (°) | χ2 (°) | χ1 (°) | χ2 (°) | |

| TyrB16 | 172.4 | 78.8 | 174.7 | 77.6 |

| 176.9 | 83.1 | 179.6 | 80.8 | |

| 175.4 | 82.9 | 172.9 | 84.3 | |

| 174.5 | 81.1 | 177.6 | 84.6 | |

| 177.0 | 79.2 | 175.9 | 75.5 | |

| 178.0 | 79.6 | 175.3 | 66.2 | |

| PheB24 | 63.2 | −87.6 | 62.5 | 89.1 |

| 69.9 | 88.4 | 69.3 | 83.2 | |

| 60.0 | −85.3 | 59.3 | 83.4 | |

| 63.0 | −86.9 | 55.2 | −85.0 | |

| 60.1 | −89.0 | 56.7 | −87.9 | |

| 61.0 | −87.5 | 68.8 | 87.5 | |

| TyrB26 | 167.8 | 74.1 | −173.9 | 82.7 |

| 166.6 | 81.0 | 168.9 | −90.5 | |

| 161.4 | 72.6 | −176.7 | 69.8 | |

| 167.7 | 75.3 | 176.5 | 74.7 | |

| 168.1 | 75.7 | −173.9 | 80.1 | |

| 165.3 | 78.0 | 175.4 | 72.4 | |

a Molecular coordinates were obtained from PDB code 1ZNJ.

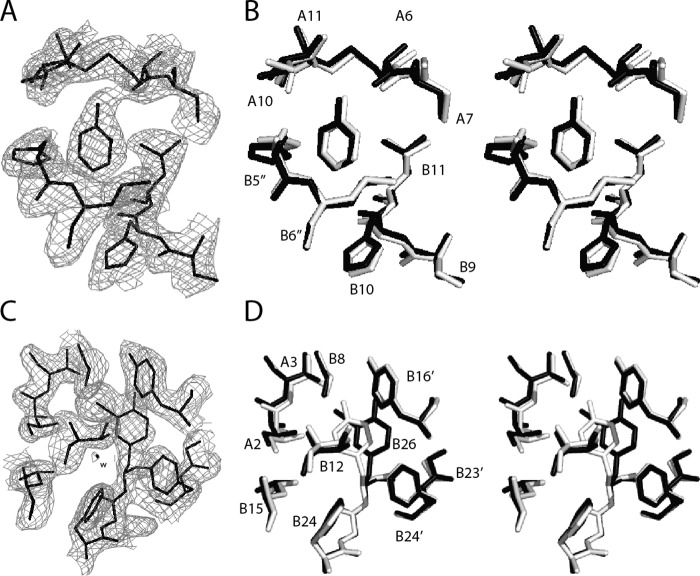

As expected, the 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin hexamer contains six bound phenol molecules, located at an interface between dimers as in the WT R6 hexamer (23). The phenol-binding sites are essentially identical. The electron density (2Fobs − Fcalc) associated with one such phenol is shown in relation to a superposition of variant and WT structures (dark and light gray in Fig. 5, A and B). In each case, a characteristic pair of hydrogen bonds from the phenolic –OH group engages the main-chain carbonyl oxygen (acceptor) and amide group (donor) of CysA6 and CysA11, respectively. A corresponding depiction of B26 side chain environments highlights the asymmetry in density between the 3- and 5-ring positions (Fig. 5, C and D). Accommodation of the modified side chain does not alter the canonical hydrogen-bonding pattern of the dimer-related anti-parallel β-strands (B24–B26 and B26′–B24′ segments) (Fig. 6A). Although differences in side-chain conformation (relative to WT) were observed at B25, its side-chain density was poor, suggesting dynamic disorder (Fig. 6B). We speculate that these differences reflect slight alterations in backbone geometry; variation in the crystallization milieu cannot be excluded.

FIGURE 5.

Crystallographic features of R6 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin hexamer. A, (2Fobs − Fcalc) difference σA-weighted electron density contoured at the 1σ level of a representative bound phenol molecule. Its para-OH group participates in hydrogen bonding with the carbonyl oxygen of CysA6 and amide proton of CysA11 (cystine A6–A11). An edge-to-face interaction occurs with the imidazole ring of HisB5 from another dimer. B, stereo view as in A aligning the structure of the analog (dark gray) with that of WT insulin as an R6 hexamer (light gray). C, electron density of 3-I-TyrB26 and surrounding residues. D, stereo view of residues seen in C (stick representation) superposed as in B. WT coordinates for B and D were obtained from PDB code 1ZNJ.

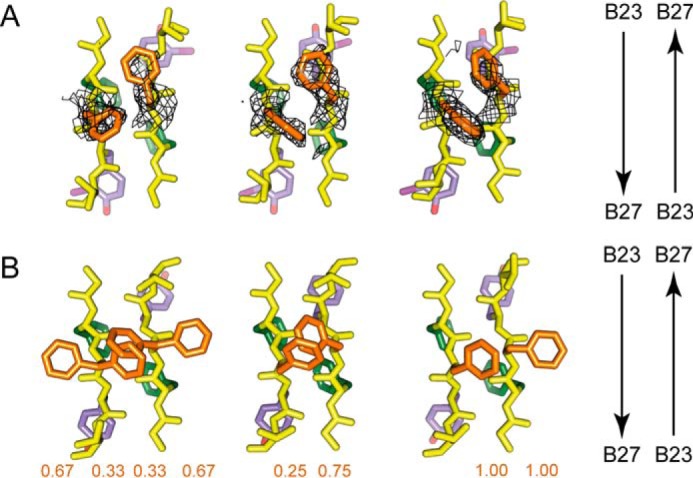

FIGURE 6.

Side-chain arrangements within dimer interfaces. Residues B23–B26 are shown within respective crystal structures of the 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]insulin hexamer (A) and WT insulin R6 zinc hexamer (PDB code 1ZNJ) (B). The three subpanels within A and B correspond to the respective three copies of the dimer interface within the crystallographic asymmetric units of the two structures. Within each subpanel, the side-chain carbon atoms of PheB24 and its non-crystallographic symmetry equivalents are shown in green, of PheB25 and its non-crystallographic symmetry equivalents in orange, and of 3-I-TyrB26 or TyrB26 and their non-crystallographic symmetry equivalents in light purple, whereas all backbone atoms are in yellow, as are the side-chain atoms of ThrB27 and its non-crystallographic symmetry equivalents. The arrows on the right assist in identifying the direction of the respective polypeptides within each subpanel. Chains within each subpanel correspond (from left to right) to chains B, D, F, H, J, and L (respectively) within each structure. Overlaid on the three subpanels in A is σA-weighted (2Fobs − Fcalc) difference electron density contoured at the 0.75 σ level and masked to within 2.5 Å of the side-chain atoms of PheB25 and its symmetry-related equivalents. The values displayed under the respective chains within the subpanels of B correspond to the side-chain occupancies of the PheB25 and its respective non-crystallographic symmetry equivalents within PDB code 1ZNJ. The side chain of NleB29 is not shown.

Comparison of Observed and Predicted Conformations of 3-I-TyrB26

The average r.m.s.d. across the dimer interface was calculated for the three 3-I-TyrB26 insulin R2 dimers with respect to WT R2 dimers (PDB code 1ZNJ; Table 1). The deviation in the 3-I-TyrB26 R2 dimers (0.7 and 0.9 Å) arises from the packing of iodine in the hydrophobic pocket. The average r.m.s.d. across the dimer interface was also calculated with respect to the crystal structure of the WT T2 dimer (PDB code 1DPH). Because in the T state GlyB8 lies within a β-turn (with positive φ angle) whereas the R state has B8 in an α-helix (negative ϕ angle), the T2-related r.m.s.d. was calculated only for backbone atoms of the β-sheets at the dimer interface (β/β′).

The χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles of selected side chains in the three dimers in the crystallographic hexamer were compared with the predicted dimer dihedral angle distribution from WT- and 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin T2 dimers (black stars for dimer 1, black squares for dimer 2, and black circles for dimer 3; see supplemental Fig. S2). In the crystallographic hexamer, the aromatic residues locally re-organize such that B24 and B24′ always have opposite χ2 angles (this is observed for all the dimers in the crystal); in contrast, the B25 side chains are disordered. Simulations, 20 ns in length, based on the R2 structure (PDB code 1ZNJ) established that the R2 dimer samples all experimentally observed states. As a control to test whether such consistency would be affected by the TR transition, corresponding trajectories based on a crystallographic T2 dimer (PDB code 1DPH) were undertaken (supplemental Fig. S2). Although sampling of B25 side-chain conformations (and to some extent that of PheB24) differed in the T2 trajectory (supplemental Fig. S2), the results were in good overall agreement with the R2-based simulations (supplemental Fig. S1).

Molecular Modeling of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]Insulin at the μIR Interface

How might iodo-TyrB26 enhance the binding of insulin to the receptor? The environment (and conformation) of iodo-TyrB26 in the variant hormone-IR complex is likely to differ from its internal environment in the modified zinc hexamer, given that in the co-crystal structure of the WT μIR complex the B23–B27 segment is displaced from its location in the free hormone (Fig. 1C) (39). Such displacement permits the aromatic rings of PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26 to contact the receptor (Fig. 7). The open receptor-bound conformation of the hormone is thus predicted to expose the side chain of 3-I-TyrB26 and in particular enable its engagement at the L1-αCT surface.

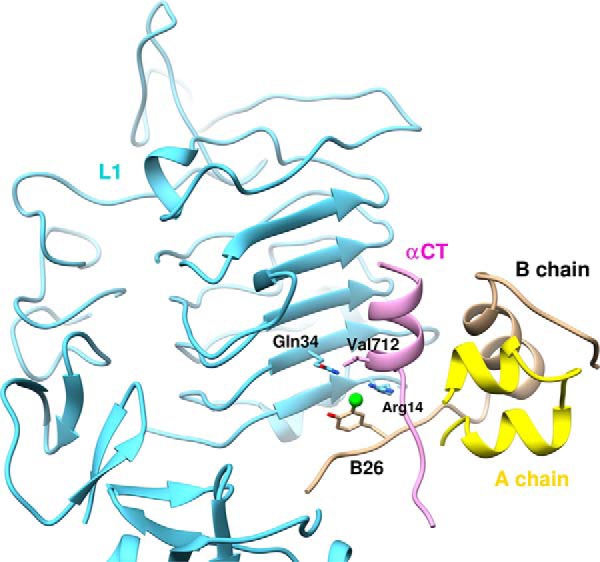

FIGURE 7.

Homology model of μIR/insulin interface. Docked structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin bound to L1 (Arg-14 and Gln-34) and αCT (Val-712) of the μIR. 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin has the iodine away from the interface (through rotation around the Cβ–Cγ axis (χ2 180°); see Fig. 2A) and is expected to interact less favorably with the μIR.

We hypothesized that the enhanced affinity of this and related iodo-TyrB26 analogs (7, 63, 64) might be due to a novel interaction between the halogen atom and the IR. MD simulation of 3-I-TyrB26 and 5-I-TyrB26 at the μIR interface (using PDB code 4OGA as starting structure) supported the plausibility of this model (Fig. 7). An iodine at either the 3- or 5-positions (Fig. 7) of TyrB26 could readily be accommodated within the receptor-binding cleft (i.e. with the iodo group directed either toward or away from the μIR interface). Whereas the 5-I-TyrB26 conformation did not appear to offer new favorable interactions, our modeling revealed that a 3-iodo-substituent could participate in three novel contacts (Fig. 8A) as follows: (i) a halogen bond between its δ+ region and the backbone oxygen atom of Val-712, and (ii and iii) favorable electrostatic interactions between its δ− equatorial belt (Fig. 2B) and one hydrogen from the ϵ-NH2 of Gln-34 and one hydrogen from the ϵ-NH2 of Arg-14. Details are as follows.

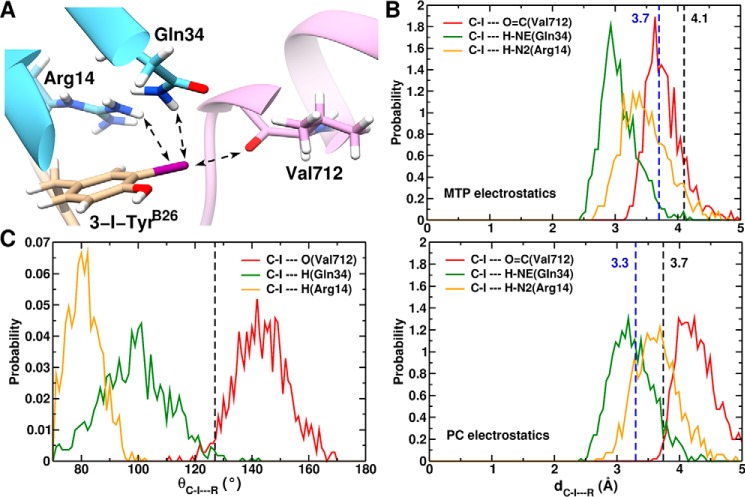

FIGURE 8.

MD-based model of μIR/3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin interface. A, structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin bound to the μIR. Only μIR residues interacting with 3-I-TyrB26 are illustrated. Potential hydrogen/halogen bonds with iodine are shown as dashed arrows. B, probability distribution along the C-I···R distance, where R is (O=C(Val-365)) (red line); R is (H-Nϵ(Gln-81)) (green line); or R is (N2(Arg-61)) (dashed orange line). The upper panel is from simulations with MTP electrostatics, whereas the lower panel uses point charges. The black dashed lines at 4.1 Å (3.7 Å, lower panel) represents the C-I···O(Val-365) interaction limit using optimized van der Waals radii for the iodine and oxygen atoms. Dashed lines at 3.7 Å (3.3 Å, lower panel) indicate the C-I···H (Gln-34 and Arg-14) distance using optimized van der Waals radii for iodine and polar H-atoms. C, probability distribution of the halogen/hydrogen bond angular variation θC-·R from 1 ns of MD simulation. The black dashed line at 127° represents the boundary between the negative (δ− < 127°) and positive electrostatic region (127° 〈δ+〉 233°) for I.

The predicted halogen bond at the variant μIR interface represents a “gain of function” by a nonstandard side chain (65). In the predicted halogen bond, the average distance between the iodine and the carbonyl oxygen of Val-712 is 3.6 Å, which is less than the sum of their van der Waals radii (4.1 Å) (Fig. 8B, upper panel). However, the estimated σ-hole size of iodine bound to a phenol, and so ortho to its hydroxyl group, is smaller due to the latter's electron-donating properties (see Fig. 2B). The σ-hole size is represented by angle β (Fig. 2C), typically 148° for iodine bound to phenyl; the directionality of the halogen bond is along the C–I bond axis (55). For 2-iodophenol, this angle is smaller (∼106°), and the halogen-bond direction shifted from the C–I bond by ∼30° (Fig. 2C). Thus, the σ-hole bond angle θ is within the δ+ region that ranges from 127° 〈θC-I·O〉 to 233° (Fig. 2C). The σ-hole bond angle distribution θC-I·O, of the iodine atom (I) with the backbone O of Val-162 from 1-ns MD, ranges from ∼127 to 170° and peaks at 145°, whereas the θC-I·H distributions are within the δ− region (Fig. 8C). The I···O distance of 3.6 Å and the C-I···O angle of ∼145° favor formation of a strong halogen bond in the complex as suggested by previous quantum-chemical calculations (66) and MD studies of other systems (55, 67, 68).

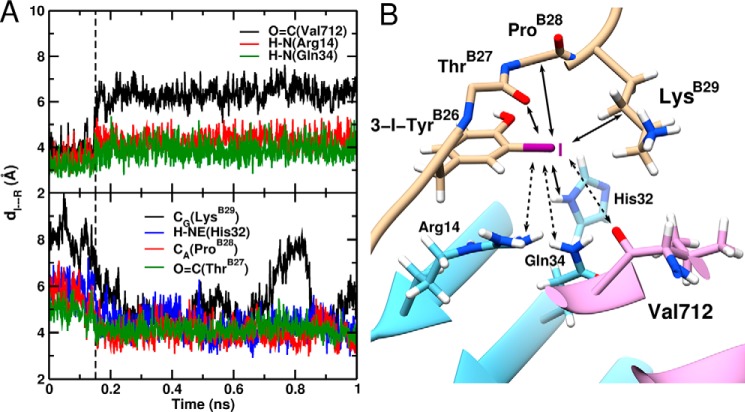

In essence, our modeling suggested that 3-I-TyrB26 leads to an increased number of local interactions at the μIR interface with retention of native contacts. All-atom simulations thus rationalized the increased affinity of such insulin analogs for the intact receptor. As a further control to test whether such increased affinity is electrostatic or nonpolar (van der Waals) in nature, we undertook additional simulations with an atom-centered PC force field and with a simplified force field in which the iodine only engaged in van der Waals interactions. In contrast to the MTP electrostatic model (upper panel in Fig. 8B), the PC model exhibited only one of the above three contacts: that to Gln-34 (lower panel). Moreover, a “neutral” iodine (q = 0) led to detachment of TyrB26 from the μIR surface after 150 ps (Fig. 9A). These control simulations suggest that the increased receptor-binding affinity of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin is driven by electrostatics at the level of quantum chemistry rather than a consequence of the hydrophobicity of iodine (Fig. 9B). The potential role of water molecules at the modified interface is discussed below.

FIGURE 9.

MD-based model of μIR/3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin interface assuming neutral iodine. A, time evolution of the I···R distance (distance of TyrB26-I to the interacting insulin/μIR residues). The upper and lower panels show the increase of the I···O=C(Val-365), I···H-N(Arg-61), and I···H-N(Gln-81) bond lengths, respectively, and the decrease of the I···Cγ(LysB29), I···H-NE(His-79), I···Cα(ProB28), and I···O=C(ThrB27) bond lengths in the course of the MD simulation. The black dashed line at 150 ps represents the point when the electrostatically driven interactions dissociate and the van der Waal-driven interactions form. B, snapshot structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin bound to the μIR. Only the residues interacting with 3-I-TyrB26 are illustrated. Bond formation/dissociation with the iodine atom are shown as full and dashed line arrows, respectively.

Discussion

This study has focused on position B26, broadly conserved as Tyr among vertebrate insulins and as Phe among insulin-like growth factors (69). Although non-polar and charged side chains at B26 are compatible with high affinity for the IR, such insulin analogs are unstable and prone to fibrillation (32). Of the natural amino acids at B26, Tyr thus appears to offer the best combination of activity and stability. How might the expanded chemical space of unnatural mutagenesis (70) be exploited to enhance the biophysical properties of an active insulin molecule? We approached this question in three parts. We first simulated the structure of [iodo-TyrB26]insulin (as a dimer) to predict how the iodine atoms could be accommodated. This simulation, critically dependent on the quantum-chemical properties of an iodo-aromatic group, suggested that the iodine might enhance (rather than perturb) native packing interactions within the core of the free hormone. We next verified the predicted conformational preference for the 3-I-TyrB26 state through crystallographic studies. Finally, we investigated possible mechanisms by which 3-I-TyrB26 enhances IR binding (7–9). Such enhancement posed a seeming paradox as a modification that “closes” the free conformation of insulin (45) might have been expected to impair its ability to open on receptor binding (39, 71).

The structure and properties of 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin reflect general physico-chemical principles. Packing of an iodo-aromatic modification within the core of a globular protein in principle reflects its overall hydrophobicity (72) and stereo-electronic properties (18). Indeed, modification of one edge of an aromatic system both introduces a unique local electronic distribution (i.e. at the halogen) and alters the overall electron density of the π-electronic cloud, including at the opposite edge. These features are exemplified by crystal structures of thyroid hormone bound to its nuclear receptor (73) or carrier proteins (74). Because thyroid hormone may have evolved from an ancestral iodo-Tyr (as in its route of biosynthesis (75)), we may regard iodinated derivatives of insulin as models for iodo-aromatic chemistries related to this evolutionary innovation. The present structure and MD simulations highlight that aromatic-rich protein interfaces are not classical ball-and-stick objects.

Modification of Residue B26 Enhances Packing Efficiency

3-I-TyrB26 represents an apparent perturbation within an anti-parallel dimer-related β-sheet. The subtle changes in the side-chain dihedral angles of 3-I-TyrB26 and 3-I-TyrB26′ observed in the crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29] Insulin (relative to TyrB26 and TyrB26′ in WT R6 hexamers) do not affect this sheet; its four dimer-related hydrogen bonds exhibit essentially native lengths and angles. Side-chain packing schemes in the WT insulin dimer within the R6 hexamer (Fig. 4A) and its comparison with the 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin dimer demonstrate that the iodine atoms both (a) reside within an overall nonpolar environment within each protomeric core, and (b) enable formation of a novel and favorable electrostatic interaction (supplemental Fig. S4B), i.e. between the para-OH of TyrA19 and the equatorial belt surrounding the halogen (Fig. 2B). The latter contact is analogous to weakly polar interactions between hydrogen-bond donors (such as the carboxamide NH2 of Asn or Gln) and the planar π cloud of aromatic rings (44). No halogen bonds were observed (supplemental Fig. S4, B and D).

Despite the larger size of iodine relative to hydrogen, only a slight re-arrangement occurs within the modified hormone core. Indeed, the internal location of the iodine atom in the crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin highlights a potential packing “defect” in WT insulin. Such gaps are in general widespread among crystal structures of globular proteins, as reflected by mean side-chain packing efficiencies of 70–80% (76). Perfect packing efficiency is not attainable given the distinct sizes, shapes, and preferred dihedral angles of amino acids. The existence and ubiquity of such cavities was highlighted in seminal studies of xenon-saturated cores (77). The packing of 3-I-TyrB26 near the side chains of A2, A3, and A19 in the present structure is thus reminiscent of the accommodation of large xenon atoms within the core of myoglobin (77).

3-I-TyrB26 Modulates Aromatic-Aromatic Interactions

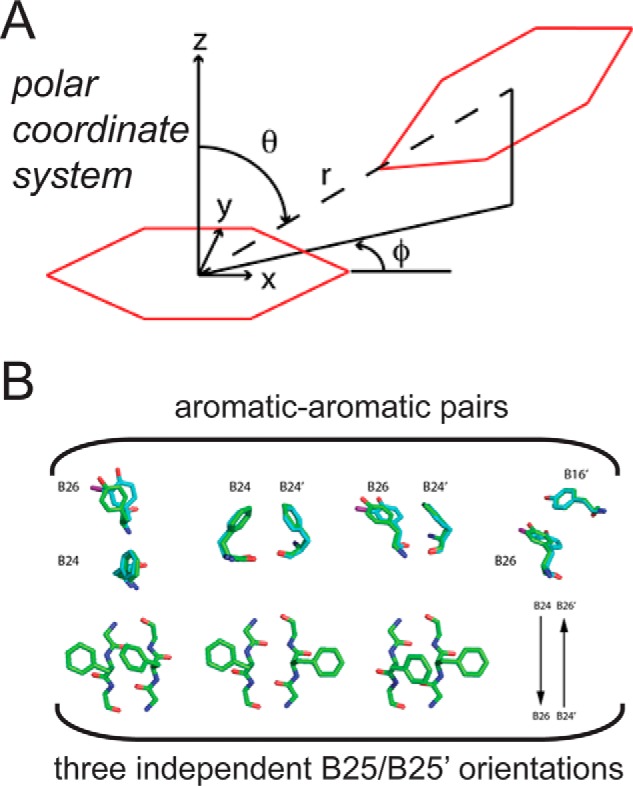

The dimer interface of insulin exhibits successive aromatic-aromatic interactions involving eight residues: TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, TyrB26, and their dimer-related mates (2). Whereas the two B25 side chains lie at the periphery of this interface (and exhibit alternative or multiple conformations among WT crystal structures (2)), the remaining six aromatic rings conform to favorable pairwise edge-to-face orientations (44). Respective aromatic-aromatic interactions at the dimer interface of WT insulin and 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin are shown in Fig. 10B. Inter-ring centroid distances and orientations are defined as illustrated in Fig. 10A (44). In a representative WT R6 structure (determined at a resolution of 2.0 Å with one hexamer in the asymmetric unit such that the three dimer interfaces are crystallographically independent; PDB code 1ZNJ), the dimer interface contains the following structural relationships.

FIGURE 10.

Aromatic-aromatic interactions. A, axes and definition of polar coordinates (r, φ, and θ) as originally defined by Burley and Petsko (44). Ψ provides the dihedral angle between the two planes formed by each of the aromatic rings. The two interacting aromatic rings are shown in red. B, interacting pairs of aromatic rings at the dimer interface of WT insulin and the 3-I-TyrB26 analog. Upper panel, PheB24/TyrB26, PheB24/PheB24′, PheB24/TyrB26, and TyrB26/TyrB16′; primed residue numbers indicate the dimer-related residue A representative WT structure (green) is overlaid in comparison with the side chains of the 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]insulin structure (cyan). Lower panel, PheB25/PheB25 interaction pair and its three possible conformations. Images of representative PheB25 side chains from the crystal structure of 3-I-TyrB26; the side chains of [NleB29]insulin are not shown due to dynamic disorder. WT coordinates were obtained from PDB code 1ZNJ.

Dimer-related Neighbors

The nearest pairs of rings in the WT R6 hexamer are across the dimer interface as follows: B16–B26′ and B26–B16′ (5.8/5.7, 5.8/5.5, and 5.7/5.5 Å in respective interfaces BD, FH, and JL as defined in the PDB); B24–B24′ (5.8, 5.7, and 5.9 Å), B24–B26′ and B26–B24′ (6.2/6.2, 5.9/5.8, and 5.8/6.1 Å). Detailed differences pertaining to B16–B26′/B16′–B26 and to B24–B26′/B24′–B26 distances reflect subtle asymmetries at each interface. Structural relationships between B16–B26′ and between B16′–B26 closely conform, in each of these six pairs, to the canonical edge-to-face packing of benzene rings (44) with mean polar angles θ = 136(±4) and φ = 49(±4)° and mean inter-plane dihedral angle ψ = 136(±4)° using polar coordinates as defined in Fig. 10A. The three B24–B24′ pairs exhibit displaced edge-to-face packing.

Intra-chain Relationships

Within each WT B chain, the side chains of PheB24 and TyrB26 project from the same side of a β-strand but (due to their respective χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles) exhibit edge-to-face interactions rather than π stacking (Fig. 10B). Their mean centroid distance is (r) 7.5(±0.1) Å with average θ values of 116(±2) and φ = 54(±3)° and with inter-plane dihedral angle 62(±8)°. Corresponding intra-chain centroid distances between TyrB16 and TyrB26 are more distant (r = 13.4(±0.1) Å), beyond the range of a favorable weakly polar interaction (44).

Alternative Occupancies of PheB25

Although the side chains of PheB25 in the WT crystal form can adopt two conformations, one mode corresponds to displaced π stacking (B25–B25′) with a centroid distance of 5.6 Å. This mode represents a distinct motif of aromatic-aromatic interaction from a quantum-chemical perspective (44). It is also possible for the two B25/B25′ aromatic rings to each point inward (i.e. toward TyrA19 in its own protomer), attenuating their aromatic-aromatic interaction.

The crystal structure of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]Insulin exhibits only subtle differences relative to the above. The altered χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles of 3-I-TyrB26 and 3-I-TyrB26′ (χ1 = 166(±2.5) and χ2 = 76(±3)°) enable packing of the iodine atom in a gap bounded by conserved side chains in both chains (IleA2, ValA3, TyrA19, LeuB11, ValB12, LeuB7, and cystine A7–B7; see supplemental Fig. S4D). Respective side-chain conformations of residues B26 and B26′ across each of the three (crystallographically independent) dimer interfaces are similar but not identical (Table 3). Repositioning of the B26/B26′ side chains is in turn associated with subtle changes in geometric parameters describing B26–B16′ (and likewise B26′–B16), B26–B24′ (also B26′–B24), and B26–B24 (Fig. 10B and Table 3). Of these, the most distinct pairwise orientations (relative to the WT reference structure) are exhibited by B26–B16′ and B24–B26′. These in turn necessitate a small change in the relative B24–B24′ positions.

Of future interest would be comparison of iodo-TyrB26 with iodo-PheB26 as a test of the predicted effect of the former's para-OH group on the position and intensity of iodine's σ-hole. Comparison of such modifications with smaller halo-aromatic substitutions would likewise enable local effects of the halogen's electronic distribution to be distinguished from general long range effects on the overall dipole moment of the modified aromatic system.

Application of MTP Modeling to the Variant Hormone-Receptor Complex

Our efforts to apply MM methods to the modified insulin dimer highlighted the importance of accurate representations of the iodo-aromatic ring and its interactions. Indeed, a PC-based model of the iodo-Tyr predicted (incorrectly) an outward orientation of the iodine atom (5-I-TyrB26), whereas an MTP-based model favored the observed inward orientation (3-I-TyrB26). These findings are in accordance with previous simulations of small molecules wherein halogenated compounds required an MTP treatment, although electronically less demanding building blocks (such as N-methylacetamide) did not (67, 78). Experimental verification of MTP-based predictions in the case of the insulin hexamer encouraged us to simulate the possible function of iodo-TyrB26 at the surface of the μIR complex (39, 71).

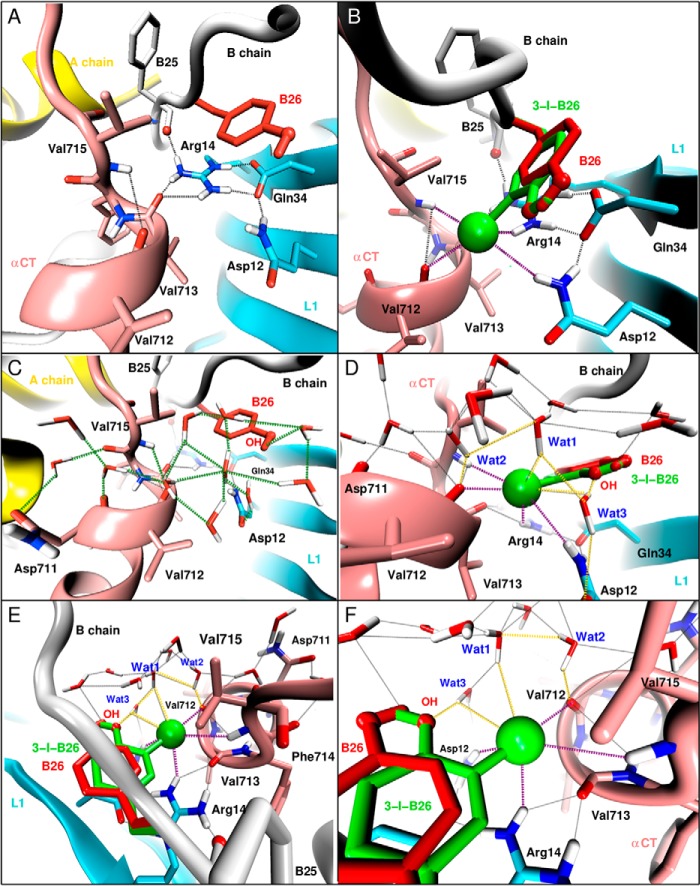

In the WT insulin-μIR complex, invariant L1 residues Arg-14 and Gln-34 are of special interest (39, 71). The side chain of Arg-14 contacts the main chain of PheB25 and defines one edge of the crevice (together with Asp-12) in which the main chain and side chain of TyrB26 loosely pack. The side-chain carboxamide of Gln-34 forms a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate of Asp-12, which in turn forms bidentate charge-stabilized hydrogen bonds to an ϵ-NH2 and δ-NH of Arg-14 below an aromatic ring of TyrB26 (Fig. 11A). This canonical Asp-Arg motif appears to be critical as Ala substitution of either residue markedly impairs the binding of insulin (71, 79, 80). In the predicted structure of the 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin/μIR interface, these native-like contacts are retained and extended by favorable electrostatic interactions with the equatorial belt of the halogen (Fig. 11B). In particular, one hydrogen in the key Arg14ϵ-NH2 group hydrogen-bonds with Asp-12, whereas the other hydrogen engages the δ−-equatorial zone of the iodine. Both hydrogens of the second ϵ-NH2 group of Arg-14 interact with the carbonyl oxygen of Val-713 in αCT; this bifurcated pair of hydrogen bonds has lengths of 1.8 and 2.3 Å with an acute angle (∼60°) between the two hydrogen bonds. Our model thus integrates the asymmetric electronic distribution around the iodine atom within a pre-existing charge-stabilized hydrogen-bond network inferred to exist in the WT complex. The conformationally averaged I···H distances to the respective side chains of Gln-34 and Arg-14 are 2.9 and 3.2 Å.

FIGURE 11.

Predicted water network at the μIR/insulin interface. A and B, local interaction at the interface around TyrB26 in WT insulin (A and C) and 3-I-TyrB26 insulin (B and D–F). The interactions involve Asp-12, Arg-14, and Gln-34 of L1; Val-712, Val-713, and Val-715 of αCT; and with PheB25 and TyrB26 of insulin. Naive WT interactions are shown as black dashed lines, and the newly introduced hydrogen-halogen interactions through the 3-I-TyrB26 mutation are shown as dashed purple lines. C–F, predicted water network at the μIR/insulin interface around TyrB26. C, formation of a water network anchored by the para-OH of TyrB26 and the carbonyl oxygens of Asn-711, Val-712, and Phe-714 (highlighted by green dashed lines) in WT. D–F, reinforcement of the pre-existing water network by interactions (yellow dashed lines) between the iodine and hydrogen atoms of three water molecules labeled Wat1, Wat2, and Wat3; Wat3 bridges the iodine and para-OH of the modified TyrB26 and the carboxyl oxygen of Asp-12 of the L1 domain (D); and Wat1 and Wat2 bridge the iodine atom to the carbonyl oxygen of Val-712 (E and F).

Water Molecules Are Integral to the Predicted Hormone-Receptor Interface

In the WT-μIR complex Val-712 lies at the C terminus of the αCT α-helix, and its carbonyl oxygen participates only in a weak-capping (i,i + 3) hydrogen bond to the main-chain NH of non-helical residue Val-715 (distance 3.6 Å and angle 113°; Fig. 11A). In the predicted structure of the [iodo-TyrB26]insulin complex, the carbonyl oxygen of Val-712 forms bifurcating interactions, the native hydrogen bond to Val-715, and the novel halogen bond to the σ-hole of the iodine. The angle between the hydrogen bond and halogen bond is ∼75°. This interface is thus remarkable for the large number of stabilizing electrostatic interactions (Fig. 11B). Although the μIR co-crystal structure was of insufficient resolution to define the bound structure in detail, the B26-related crevice is exposed to solvent, and our MD simulations predicted formation of a bound water network anchored by the para-OH of TyrB26 and the carbonyl oxygens of Asn-711, Val-712, and Phe-714 (Fig. 11C). In the [iodo-TyrB26]insulin complex, this network is retained and reinforced by interactions between the iodine and hydrogen atoms of three water molecules (Fig. 11D); one of these water molecules bridges the neighboring iodine and para-OH of the modified TyrB26 (Wat3 in Fig. 11, E and F).

Together, the δ−-equatorial zone of the iodine atom is thus predicted to engage five hydrogen atoms, three from water molecules and two from L1 side chains Arg-14 and Gln-34 (as above; Fig. 11, E and F). Given the atomic radius of iodine (2.4 Å), its circumference may be estimated as ∼30 Å, sufficient to accommodate these five contacts. One of the above three water molecules (Wat1) also contacts the water molecule (Wat2) anchored by the carbonyl oxygen of Val-712 (Fig. 11F) and in turn a hydrogen-bonded network involving Val-712(C=O)···H(W2)···O(W1)···I(TyrB26). A striking prediction of this model is thus that a water-αCT network bridges the δ−-equatorial zone of the iodine atom with its δ+ σ-hole.

Might the predicted iodine-anchored network of interfacial water molecules be observable in future co-crystal structures? To address this issue, we computed thermal B-factors from the fluctuation around average positions. We first focused on the three putative water molecules (Wat1, Wat2, and Wat3) involved in hydrogen bonds with (or bridging between) the iodine atom, the para-OH of TyrB26, and the carbonyl oxygen of Val-712. Each of these H2O oxygen atoms was predicted to exhibit a B-factor ∼40 Å2, significantly lower than that of other water molecules at this interface (>100 Å2) and similar to the B-factors of the Cγ atoms of Val-712, Arg-14, and Gln-34 (i.e. ∼30 Å2). Moreover, the number of water molecules within 4 Å of the iodine atom at the 3-I-TyrB26/μIR/water interface ranging from 1 to 5 with an average of 3 during 1 ns of equilibrium MD simulation (supplemental Fig. S6). A similar analysis of the WT insulin/μIR/water interface also found strongly interacting water molecules, albeit with increased B-factors (∼50 Å2). We therefore anticipate that the three predicted iodine-anchored structural water molecules should be observable by crystallography in a sufficiently well ordered crystal.

Concluding Remarks

The promise of non-standard insulin analogs to enhance the treatment of diabetes mellitus represents an important frontier of molecular pharmacology (81). Indeed, substitution of TyrB26 by 3-I-Tyr in the rapid-acting analog insulin lispro enhances its stability and resistance to fibrillation while maintaining its biological activity (45). The present crystal structure has demonstrated how the modified side chain pivots to enable burial of the iodine atom in the hydrophobic core. Despite such apparent optimization of the free state (45), 3-I-TyrB26 also enhances receptor binding (7–9). Our MD simulations suggest that enhancement is mediated by quantum chemistry: direct electrostatic effects of the iodine exploiting its δ+ σ-hole and δ− equatorial belt (46). This mechanism envisions that 3-I-TyrB26 switches from an iodo-in conformation (free) to an iodo-out conformation (IR bound). Testing this proposal will require higher resolution structures of WT- and iodo-modified hormone-receptor complexes.

Experimental Procedures

Preparation of Insulin Analogs

Analogs were made by trypsin-catalyzed semi-synthesis using insulin fragment des-octapeptide(B23–B30)-insulin and modified octapeptides (4). The fragment was generated via cleavage of human insulin with trypsin and purified by reverse-phase HPLC; octapeptides were synthesized by solid-phase synthesis (82). Formation of a peptide bond between ArgB22 and the synthetic octapeptide was mediated by trypsin (in a mixed solvent system containing 1,4-butanediol and dimethylacetamide) (83). Insulin analogs were purified by preparative reverse-phase C4 HPLC (Higgins Analytical Inc., Proto 300 C4 10 μm, 250 × 20 mm), and their purity assessed by analytical rp-C4 HPLC (Higgins C4 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm). Molecular masses were verified using an Applied Biosystems 4700 proteomics analyzer (matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry).

Circular Dichroism

Far-ultraviolet CD spectra were obtained on an AVIV spectropolarimeter equipped with an automated syringe-driven titration unit. The proteins were made 50 μm in 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and 50 mm KCl. Spectra were obtained from 190–250 nm as described (84). Thermodynamic stabilities were probed by guanidine hydrochloride-induced denaturation monitored by CD at 222 nm. Data were fit by non-linear least squares to a two-state model (85) as described (86).

Receptor Binding Assays

Affinities for IR-B were measured by a competitive-displacement scintillation proximity assay. This assay employed solubilized receptor with C-terminal streptavidin-binding protein tags purified by sequential wheat germ agglutinin and StrepTactin-affinity chromatography from detergent lysates of polyclonal stably transfected 293PEAK cell lines expressing each receptor. The details of this assay were recently described (32). To obtain analog dissociation constants, competitive binding data were analyzed by non-linear regression (87).

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals of HPLC-purified 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]insulin were obtained via hanging-drop vapor diffusion at 25 °C. 1-μl drops containing the protein at 10 mg/ml in 0.02 n HCl were mixed with a 1-μl drop of reservoir buffer containing 0.1 m sodium citrate, 0.08% zinc acetate, and 2% phenol. Drops were suspended over 1 ml of reservoir buffer. A single crystal was transferred to a solution containing 30% glycerol in the mother liquor for flash freezing. Diffraction data were obtained using an in-house X-ray source consisting of a Rigaku rotating-anode X-ray generator (MicroMaxTM 007HF) with VariMax confocal optics, a Saturn 944+ CCD X-ray detector, and an X-Stream 2000 cryogenic crystal cooling system (located at Case Western Reserve University). Data analysis employed XDS (88). The structure was determined by molecular replacement using PDB code 1ZNJ as a search model, followed by iterative refinement and model building using PHENIX (89) and COOT (90), respectively. The refinement strategy included both TLS refinement (translation, libration, and screw rotation) and torsional non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraints between related chains. Coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 5EMS).

QM-parameterized MM Calculations

MD simulations employed CHARMM version c40a1 (91) with the “all-atom” force field CHARMM22 (53) using the correction map (CMAP) potential for the backbone dihedral (φ,ψ) to correct for the α-helical bias. To account for electronic anisotropy of ortho-iodophenol (employed as a model compound for purposes of MM parametrization), an electrostatic multipole model (MTP) (54) was obtained for the phenolic ring of TyrB26 and iodophenolic ring of I-TyrB26. The MTP implementation used in this work is that of Bereau et al. (54), which uses up to quadrupolar moments on each interaction site (87). Atomic multipoles are assigned to all heavy atoms (but not the hydrogens). The parametrization protocol followed a recently developed strategy that includes optimization of multipole moments to best represent the electrostatic potential and van der Waals parameters to correctly describe experimental solution phase data, including the hydration free energy of iodophenol (92). MTPs were derived from ab initio calculations at the MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ (93) level of theory using GAUSSIAN09 (94). The iodine atom was treated by the aug-cc-pVDZ-PP basis set with an effective core potential (95). For the rest of the system, a point-charge (PC) model was used; water molecules were treated with the TIP3P model (96).

Starting coordinates of the insulin dimers were first taken from the T2 zinc-free structure of WT insulin (PDB code 1DPH, resolution 1.9 Å (97)) and extracted from the R6 structure of the WT zinc hexamer (PDB 1ZNJ, resolution 2.0 Å), respectively, and subsequently extended to the present crystal structure of a 3-I-TyrB26 insulin analog. For corresponding simulations of the variant μIR-insulin complex, starting coordinates were obtained from the lowest energy initial model (see below). The systems were first minimized by steepest descent for 5 × 104 steps. The proteins were solvated in TIP3P water molecules (96) equilibrated at 300 K and 1 atm (within a 52.77Å cubic box for the dimers and a 93 Å cubic box for the μIR-insulin with sodium and chloride ions added to neutralize the system). The box was heated from 0 to 300 K for 30 ps, equilibrated for 500 ps, and then subjected to 10 ns of production MD with periodic boundary conditions. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method (98) was used for PC-PC interactions, with grid spacing of 1 Å, a relative tolerance of 10−6, an interpolation order of 4 for long-range electrostatics, and a cutoff of 14 Å together with a 12-Å switching threshold for L-J interactions. Bonds involving hydrogen were constrained by SHAKE (99).

Because of aromatic ring rotation about the Cβ–Cγ bond axis, the mono-iodo derivative of [TyrB26]insulin may in principle form either 3-I-TyrB26 or 5-I-TyrB26 conformational isomers (with the iodine atom at ring positions 3 or 5; i.e. ortho to the phenolic hydroxyl group and meta to Cγ). Hence, depending on the B26 χ2 angle, isomerization of 3-I-TyrB26 to 5-I-TyrB26, and vice versa, is possible during the dynamics. Because the relative stabilities of these conformational isomers were not known a priori, two independent MD dimer simulations of 20 ns each were carried out starting from initial 3-I or 5-I B26 conformations, respectively. These simulations began from a T state crystallographic protomer (PDB code 1DPH (97)) because the conformation of an insulin monomer in solution resembles the T state (28, 29).

Rigid-body Calculations

Naive replacement of B26's H atoms (atomic radius 1.20 Å and CH bond length 1.08 Å) by iodine (atomic radius 2.40 Å and CI bond length 2.08 Å) in positions 3 and 5 was carried out, starting from the coordinates of T2 zinc-free structure of WT insulin (PDB code 1DPH, resolution 1.9 Å (97)). First, the three systems (WT, 3-I, and 5-I) were energy-minimized by steepest descent for 5 × 104 steps using an optimized GBSW (generalized Born with a smoothed switching function (100, 101)) implicit solvent force field (78). In a next step, energies from two scans around χ1–χ2 dihedral angles (±20° in each dihedral angle in steps of 1°) were computed, using a PC and an MTP representation for the TyrB26 side chain as follows: (i) a rigid scan, where single point energies are calculated upon χ1–χ2 rotations, and (ii) a relaxed scan, where the protein side chains were energy-minimized for 100 steps of steepest descent after each χ1–χ2 rotations.

Quantum-Chemical Calculations

The molecular electrostatic potential (incorporated electron density) from the same electronic structure calculations was employed for the MTP parameter fitting as mapped at the 10−3 e atomic units−3 isodensity surface using Gaussview5 (102). All ab initio calculations were carried out with Gaussian09 (94), and optimized structures were used. The size of the iodine σ-hole size was measured as the angular profile of the ESP intersection line of the grid and the halogen boundary (defined as a surface of electron isodensity of 10−3 e atomic units−3) (55). Such ab initio calculations were undertaken solely for the purpose of parameterizing an MM model of the modified insulin. Explicit QM/MM simulations were not performed.

Modeling of the Variant Hormone-Receptor Complex

To explore how iodo-TyrB26 might pack within the insulin-IR complex, the potential environment of the modified ring was considered in the context of the WT insulin-μIR complex (PDB code 4OGA (39)). Several subsets of residues disordered in the crystal structure (IR residues Cys-159–Asn-168 and Lys-265–Gln-276 and insulin residues B28–B30) were included, as were N-linked N-acetylglucosamine modifications at sites Asn-16, Asn-25, Asn-111, Asn-215, and Asn-255 (103). An initial set of 50 models was created, and the structure with lowest empirical energy was selected for MD simulations. A model of the variant μIR complex was constructed in two stages. Preliminary MD studies of the variant hormone-μIR complex were first performed using a coarse model of the modified side chain within the GROMACS package (version 4.6.1 (104)) with OPLS-all atom force field (96, 105) as described below. The lowest energy model emerging from this simulation then provided a starting point for QM-parameterized MD as outlined above. Initial MD simulations of the variant μIR complex exploited an approximate model of 3-I-Tyr in which a virtual site was placed near the iodine atom to mimic the σ-hole. This site's position was determined by minimizing the error of the fit of the atom-centered charges to the molecular electrostatic potential for 2-iodo-4-methylphenol, calculated at the HF/6–311G(d,p) level; the optimal position of the virtual site was 1.5 Å from the iodine, co-linear with the C–I bond. Respective partial charges on the virtual site, iodine and carbon attached to iodine, were 0.115e, −0.322e, and 0.207e; charges on all other atoms were adopted from the OPLS-aa parameters for Tyr. Proteins were solvated in a cubic box of TIP4P water molecules (96); the box extended 10 Å beyond any protein atom. Ionizable residues and protein termini were set in their charged states. Sodium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the system at a final ionic strength of 0.10 m. Protein and solvent (including ions) were coupled separately to a thermal bath at 300 K employing velocity rescaling (106) with coupling time 1.0 ps. Pressure was maintained at 1 bar using a Berendsen barostat (107) with coupling constant 5.0 ps and compressibility 4.5 × 10−5 bar. The time step was 2 fs. Simulations were performed with a single non-bonded cutoff of 10 Å and neighbor-list update frequency of 10 steps (20 fs). The PME method modeled long-range electrostatics (108); the grid width was 1.2 Å with fourth-order spline interpolation. Bond lengths were constrained using LINCS (109). The MD protocol consisted of an initial minimization of water molecules, followed by 100 ps of MD with the protein restrained to permit equilibration of the solvent. Calculations were continued for 200 ns from the geometries obtained after initial positionally restrained MD at a temperature of 300 K.

Database Deposition

Atomic coordinates of the crystal of 3-[iodo-TyrB26,NleB29]insulin have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 5EMS).

Supplemental Information

The supplemental Table S1 provides interaction energies contributing to dimerization. The supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 provide side-chain dihedral-angle distributions (χ1,χ2). The supplemental Fig. S3 illustrates predicted packing schemes at the variant dimer interfaces. The supplemental Fig. S4 illustrates predicted and observed structural relationships in 3-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin. The supplemental Fig. S5 provides details concerning the alternative (and less favorable) 5-[iodo-TyrB26]insulin dimer interface. The supplemental Fig. S6 depicts water molecules at the variant μIR interface.

Author Contributions

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed by K. E. H., B. J. S., and M. M. The de novo quantum simulations and electrostatic multipole parametrization was done by K. E. H. and M. M. Biochemical and biophysical assays were performed by V. P., N. B. P., and J. W. Insulin analogs were prepared by V. P. and N. B. P. Crystallization trials and structure determination were undertaken by V. P. Refinement was performed by V. P., J. G. M., and M. L. C. Molecular modeling of the variant hormone-μIR interface was undertaken by K. E. H., B. J. S., and M. M., with the assistance of J. G. M., M. L. C., and M. A. W. The overall program of research was guided by M. M. and M. A. W. Each of the authors contributed to the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Q.-X. Hua, W. Jia, L. Whittaker, S. H. Nakagawa, and Z.-L. Wan for advice regarding experimental procedures. We thank N. Rege for assistance with manuscript preparation and journal editors C. Goodman and M. Spiering for helpful suggestions. We also thank Profs. P. Arvan, T. L. Blundell, F. Ismail-Beigi, M. Karplus, P. G. Katsoyannis, and M. Liu for general discussion.