Abstract

Preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is important in the therapeutic effect of antidepressants. A previous study demonstrated that the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline induces Gαi/o activation, which leads to GDNF expression in astrocytes. However, the specific target expressed in astrocytes that mediates antidepressant-evoked Gαi/o activation has yet to be identified. Thus, the current study explored the possibility that antidepressant-induced Gαi/o activation depends on lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (LPAR1), a Gαi/o-coupled receptor. GDNF mRNA expression was examined using real-time PCR and Gαi/o activation was examined using the cell-based receptor assay system CellKeyTM in rat C6 astroglial cells and rat primary cultured astrocytes. LPAR1 antagonists blocked GDNF mRNA expression and Gαi/o activation evoked by various classes of antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline, mianserin, and fluoxetine). In addition, deletion of LPAR1 by RNAi suppressed amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA expression. Treatment of astroglial cells with the endogenous LPAR agonist LPA increased GDNF mRNA expression through LPAR1, whereas treatment of primary cultured neurons with LPA failed to affect GDNF mRNA expression. Astrocytic GDNF expression evoked by either amitriptyline or LPA utilized, in part, transactivation of fibroblast growth factor receptor and a subsequent ERK cascade. The current results suggest that LPAR1 is a novel, specific target of antidepressants that leads to GDNF expression in astrocytes.

Keywords: astrocyte, depression, drug action, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), lipid signaling, lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1, antidepressants, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, transactivation

Introduction

In the central nervous system, glial cells, especially astrocytes, are believed to play a critical role in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder and possible targets of clinically used antidepressant medications (1). One of the major roles of astrocytes is the production of neurotrophic/growth factors, which are crucial in the process of neural plasticity (2). Recently, both clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that increased production of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)2 upon treatment of antidepressants is believed to play an important role in the therapeutic effect of antidepressants (3–5).

Previous studies have demonstrated that several different classes of antidepressants increase GDNF mRNA expression and release in rat C6 astroglial cells (C6 cells) and rat primary cultured astrocytes (primary astrocytes), but not in primary neurons (6, 7). Furthermore, the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline induced the Gαi/o activation in astroglial cells, leading to GDNF expression through a monoamine-independent mechanism, possibly via a transactivation-like cascade of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)/FGFR substrate 2α (FRS2α)/ERK (8, 9). These results suggest the possibility that astrocytes have a unique Gαi/o activation site that is responsive to antidepressants. However, the specific target expressed in astrocytes that mediates the amitriptyline-evoked Gαi/o activation has yet to be identified.

Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (LPAR1), a Gαi/o-coupled receptor abundantly expressed in the brain, has been shown to be involved in neurological and psychiatric disorders (10–12). In CHO-K1 fibroblasts, antidepressants induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 through LPAR1 (13). However, whether LPAR1 is involved in antidepressant-evoked signaling in cells of the central nervous system is unknown. Therefore, the current study examined the possibility that LPAR1 expressed on astrocytes is the Gαi/o-coupled receptor that mediates GDNF expression following antidepressant treatment.

Results

Several Different Classes of Antidepressants Increase the GDNF mRNA Expression and Gαi/o Activation through LPAR1 in C6 Cells

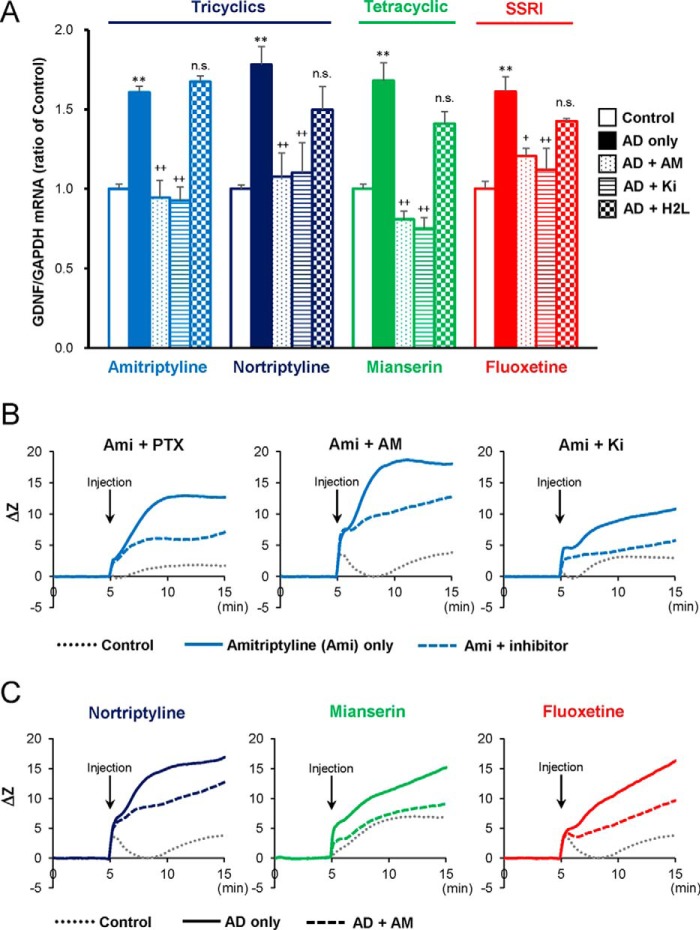

To test whether LPAR1 is involved in antidepressant-evoked GDNF expression, C6 cells were incubated with LPAR antagonists. Treatment with the various antidepressants, including tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline and nortriptyline), a tetracyclic antidepressant (mianserin), and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine), significantly increased GDNF mRNA expression (Fig. 1A). The antidepressant-evoked increases of GDNF mRNA expression were significantly blocked by AM966 (a selective LPAR1 antagonist) and Ki16425 (a selective LPAR1/3 antagonist), but not H2L5186303 (a selective LPAR2 antagonist) (Fig. 1A). Incubation of C6 cells with LPAR antagonists alone did not significantly affect GDNF mRNA expression (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

The effect of LPAR antagonists on the antidepressant (AD)-evoked GDNF mRNA expression and impedance (ΔZ) in C6 cells. A, effect of LPAR antagonists on AD-evoked GDNF mRNA expression. Cells were pretreated with AM966 (AM), Ki16425 (Ki), or H2L5186303 (H2L) for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with 25 μm amitriptyline, nortriptyline, mianserin, or fluoxetine for 3 h. **, p < 0.01 versus each control; and +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.01 versus each AD alone. n.s., no significant difference compared with “AD alone” (Bonferroni's test; n = 3–10). B, effect of PTX, AM, and Ki on amitriptyline-evoked ΔZ. Cells were pretreated with either PTX for 3 h, or AM or Ki for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with 25 μm amitriptyline for 10 min. The traces shown are representative data, which express the mean impedance of the cell layer (ΔZ) within the same experimental day. Results were obtained with at least three independent experiments. C, effect of AM on AD-evoked ΔZ. Cells were pretreated with either vehicle or AM for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with 25 μm nortriptyline, mianserin, or fluoxetine for 10 min. The representative traces shown are expressed as mean ΔZ within the same experimental day.

An electrical impedance-based biosensor (CellKeyTM assay) is specifically tailored to G protein-coupled receptor detection and can distinguish signals between the Gαs, Gαi/o, and Gαq subfamilies measured by cell layer impedance (ΔZ) (8, 14). Amitriptyline increased ΔZ, indicative of Gαi/o activation. This increase of ΔZ was reduced by pertussis toxin (PTX, a specific Gαi/o inhibitor) (Fig. 1B), which confirms a previous finding (8). Addition of LPAR1 antagonists, either AM966 or Ki16425, also reduced the amitriptyline-induced increase of ΔZ (Fig. 1B). The effects of blocking LPAR1 and LPAR1/3 were comparable with that obtained with PTX. The effect of the inhibitors on the increase of ΔZ evoked by amitriptyline was statistically significant (PTX, p < 0.01; AM966, p < 0.01; and Ki16425, p < 0.05). Other antidepressants (nortriptyline, mianserin, and fluoxetine) also increased ΔZ, which was attenuated by AM966 (Fig. 1C). The inhibitory effects of AM966 were significant (nortriptyline, p < 0.05; mianserin, p < 0.01; and fluoxetine, p < 0.05). By contrast, non-antidepressant drugs, haloperidol and diazepam, did not affect either GDNF expression (7, 15) or ΔZ (data not shown) in C6 cells.

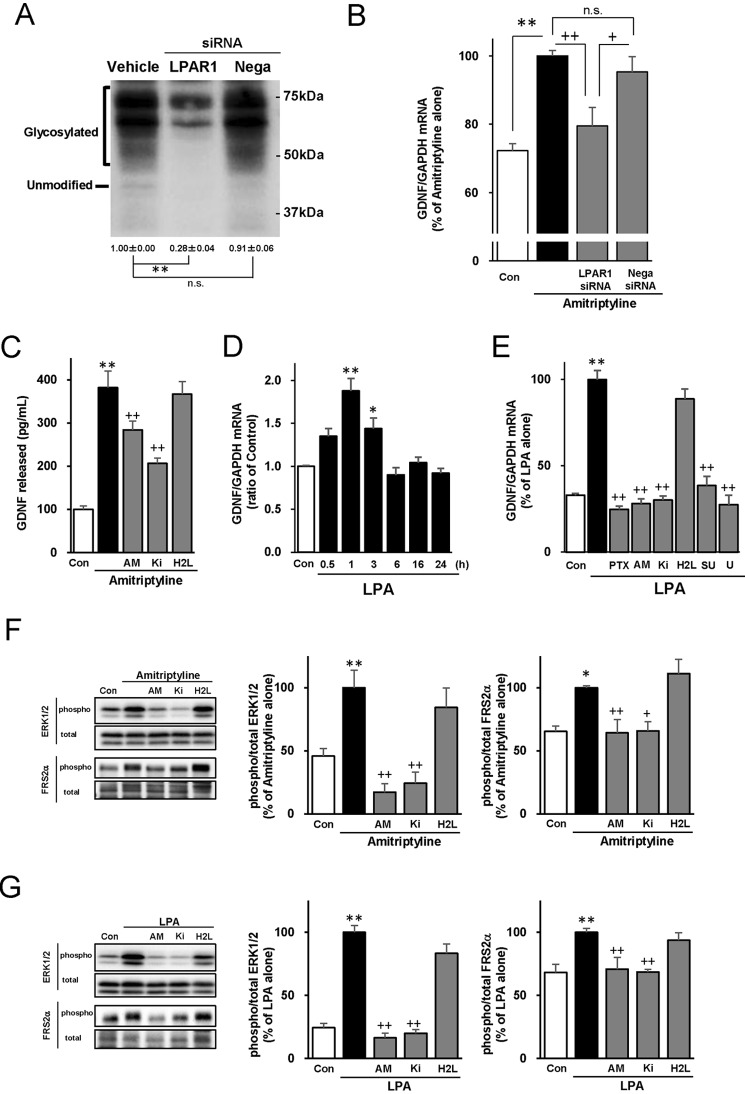

Knockdown of LPAR1 Decreases the Amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA Expression in C6 Cells

To further demonstrate that LPAR1 is involved in GDNF expression induced by antidepressants, C6 cells were transfected with LPAR siRNA. LPAR1 consists of an unmodified form (41 kDa) and a glycosylated form (50–75 kDa) (16). Transfection with LPAR1 siRNA, but not negative control siRNA, significantly decreased protein levels of LPAR1 to less than one-third of vehicle (Fig. 2A). Amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA expression was significantly suppressed by LPAR1 siRNA transfection, whereas transfection with negative control siRNA did not significantly affect the amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA expression (Fig. 2B). Transfection with LPAR1 siRNA or negative control siRNA alone did not significantly affect GDNF mRNA expression (data not shown). By contrast, transfection of C6 cells with either LPAR2 or LPAR3 siRNA, which showed specific knockdown of the expression of their respective receptors, did not affect amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA expression (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 2.

The involvement of LPAR1 in amitriptyline- and LPA-evoked GDNF expression, ERK1/2, and FRS2α in C6 cells. A, effect of LPAR1 siRNA on LPAR1 protein levels. Cells were transfected with vehicle, LPAR1 siRNA, or negative control (Nega) siRNA for 48 h. LPAR1 proteins were quantified by immunoblotting. Immunoblots from a representative experiment are shown. The numbers under the immunoblots indicate mean ± S.E. relative-fold change in expression compared with vehicle. **, p < 0.01; n.s., not statistically significant (Bonferroni's test; n = 4–5). B, effect of LPAR1 siRNA on amitriptyline-evoked GDNF mRNA expression. Cells were transfected with vehicle, LPAR1 siRNA, or Nega siRNA for 48 h and subsequently treated with 25 μm amitriptyline for 3 h. **, p < 0.01; +, p < 0.05; n.s., not statistically significant (Bonferroni's test; n = 6–16). C, the effect of LPAR antagonists on the amitriptyline-GDNF release. C6 cells were pretreatment with either AM966 (AM), Ki16425 (Ki), or H2L5186303 (H2L) for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with 50 μm amitriptyline for 24 h. **, p < 0.01; +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.01; n.s., not statistically significant (Bonferroni's test; n = 8–10). D, time-dependent effect of LPA on GDNF mRNA expression. Cells were treated with 100 nm LPA for the indicated period in hours. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control (Bonferroni's test; n = 3–7). E, effect of LPAR-related inhibitors on LPA-evoked GDNF mRNA expression. Cells were pretreated with either PTX for 3 h, or AM, Ki, H2L, SU5402 (SU), or U0126 (U) for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with 100 nm LPA for 1 h. **, p < 0.01 versus control, and ++, p < 0.01 versus LPA alone (Bonferroni's test; n = 3–4). F and G, effect of LPAR antagonists on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and FRS2α phosphorylation evoked by either amitriptyline (F) or LPA (G). Cells were pretreated with AM, Ki, or H2L for 0.5 h and subsequently treated with either 25 μm amitriptyline for 5 min or 100 nm LPA for 2 min. Phosphorylated/total ERK1/2 and phosphorylated/total FRS2α were quantified by immunoblotting. Immunoblots from a representative experiment are shown on the left and quantitative data are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control; and +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.01 versus amitriptyline or LPA alone (Bonferroni's test; n = 3–8).

Amitriptyline Increases GDNF Protein Release through LPAR1 in C6 Cells

Significant GDNF protein release from C6 cells was observed 48 h after amitriptyline treatment (15). However, because 48 h treatment with LPAR antagonists causes a nonspecific toxic effect in C6 cells, the effect of LPAR antagonists on the amitriptyline-induced GDNF release at a shorter treatment time (24 h) was examined. Twenty-four h treatment of C6 cells with 25 μm amitriptyline did not significantly increase GDNF release (15), whereas 50 μm amitriptyline significantly increased GDNF release (Fig. 2C). This amitriptyline-induced GDNF release was significantly inhibited by AM966 and Ki16425, but not H2L5186303 (Fig. 2C).

Treatment with LPA Increases GDNF mRNA Expression through LPAR1 in Astroglial Cells but Not in Neurons

C6 cells were treated with LPA (100 nm), an endogenous LPAR ligand, and GDNF mRNA expression was quantified. Significant GDNF mRNA expression was observed 1 h after LPA treatment and returned to basal levels 6 h after the beginning of treatment (Fig. 2D) in a concentration-dependent manner (EC50 = 61.99 nm). Significant GDNF protein release was also observed with 24 h treatment of LPA in C6 cells (control, 59.3 ± 8.0; 100 nm, 83.2 ± 4.2; 1 μm, 100.1 ± 5.2 pg/ml, respectively; n = 4), which was comparable with the increase observed with 48 h incubation of 25 μm amitriptyline (8). Furthermore, pre-treatment with PTX, AM966, or Ki16425, but not H2L5186303, significantly blocked the GDNF mRNA expression evoked by LPA (Fig. 2E).

Amitriptyline treatment increases GDNF mRNA expression in primary astrocytes as well as C6 cells but not in primary neurons (6). Thus, the effect of LPA on GDNF mRNA expression in primary astrocytes and neurons were examined. Treatment of primary astrocytes with LPA significantly increased GDNF mRNA expression, which was significantly attenuated with PTX, AM966, or Ki16425, but not H2L5186303 (supplemental Fig. S2 A). However, treatment of primary neurons with LPA (1 μm) failed to affect the GDNF mRNA expression (supplemental Fig. S2 B).

Activation of LPAR1 Evoked by Either Amitriptyline or LPA Induces the Phosphorylation of FRS2α and ERK1/2 in C6 Cells

The potential involvement of the transactivation cascade (FGFR, FRS2α, and ERK1/2) related to GDNF expression (8, 9) in LPAR1-mediated signaling was examined. Preincubation with either SU5402 (an FGFR inhibitor) or U0126 (a MEK/ERK inhibitor) completely blocked LPA-evoked GDNF mRNA expression in C6 cells (Fig. 2E). Amitriptyline-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and phosphorylation of FRS2α, a surrogate of FGFR activation (8), were significantly inhibited by AM966 and Ki16425, but not H2L5186303 (Fig. 2F). LPA-induced phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and FRS2α were also significantly inhibited by AM966 and Ki16425 (Fig. 2G).

Discussion

The current data are the first to clearly demonstrate that Gαi/o-coupled LPAR1 in astrocytes mediates GDNF mRNA expression evoked by various antidepressants. It has been previously suggested that the FGFR/FRS2α/ERK cascade mediates, in part, amitriptyline-induced GDNF expression (8, 9). The current results demonstrated that a transactivation cascade, FRS2α and ERK1/2, observed with amitriptyline treatment is mediated through LPAR1. Furthermore, the mechanism is unique to LPAR1 expressed on astrocytes as LPA treatment of neurons did not increase GDNF mRNA expression. The current findings suggest a novel non-neural, astrocytic target of antidepressants.

In the current study, PTX decreased the amitriptyline-evoked increase of ΔZ (the pattern of Gαi/o activation), indicating involvement of PTX-sensitive Gαi/o protein. Addition of LPAR1 antagonists, either AM966 or Ki16425, also reduced the amitriptyline-induced increase of ΔZ to the extent observed when PTX was added to amitriptyline. LPAR1 is coupled to a PTX-sensitive Gαi/o in astrocytes (17). Therefore, these findings suggest that amitriptyline could increase ΔZ through LPAR1 coupled to a PTX-sensitive Gαi/o protein. However, the inhibitory effect of PTX on the increase of ΔZ appears to be partial, suggesting the possibility that amitriptyline activates a signaling pathway that involves PTX-insensitive Gα proteins. In the Gαi/o subfamily, Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαo1, Gαo2, and Gαz subunits have been identified and share similar properties in signal transduction (18). Among these subunits, Gαz lacks the C-terminal cysteine residue and is not inactivated by PTX treatment (19, 20). C6 cells express Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαo1, Gαo2, and Gαz (8). On one hand, it is suggested that the amitriptyline-induced increase of ΔZ involves both PTX-sensitive Gα subunits, such as Gαi and Gαo, and PTX-insensitive subunits, such as Gαz. On the other hand, the contribution of PTX-insensitive subunits may not be significant, as amitriptyline-induced GDNF mRNA expression is completely suppressed by PTX (8). Therefore, amitriptyline-induced GDNF expression involves the activation of LPAR1 coupled to a PTX-sensitive Gαi/o in C6 cells.

LPAR1 inhibition significantly blocked both mRNA expression and protein release of GDNF evoked by amitriptyline in C6 cells. A partial inhibitory effect of LPAR1 antagonists on GDNF release evoked by amitriptyline was observed, suggesting the possibility that amitriptyline increases GDNF release via a LPAR1-dependent and -independent manner. A previous study showed a case that GDNF protein release was regulated by a mechanism that did not alter GDNF mRNA levels (21), suggesting a possible role of post-transcriptional regulation. Therefore, amitriptyline increases GDNF release through LPAR1-mediated GDNF mRNA induction and possibly through other post-transcriptional regulation pathways.

LPAR1 is expressed in several types of cells in the brain, especially glial cells, in various stages of the life cycle. LPAR1 is involved in myelination, proliferation, and maturation of neurons (11). Primary astrocytes used in the current study showed basal levels of LPAR1 mRNA that were 45 times higher than that of primary neurons.3 Thus, the lack of effects of amitriptyline and LPA on GDNF expression in primary neurons (6) could be due to their low level of LPAR1 expression. A previous study showed that factors released from astrocytes following LPA treatment, but not LPA itself, promoted neuronal differentiation (22). Therefore, it is possible that antidepressant treatment, through activation of astrocytic LPAR1, induces the release of a number of factors, including GDNF, which promote neural plasticity.

Previous in vivo studies have shown that behavioral response to antidepressants involves increasing GDNF expression and PTX-sensitive signaling in the brain. Chronic stress in mice led to depressed-like behavior and decreased brain expression of GDNF, both of which were reversed with antidepressant treatment (5). Administration of PTX completely blocked the pharmacological effect of amitriptyline in mice as assessed in the forced swim test (23). In vivo studies will be needed to verify if astrocytic LPAR1 is involved in the behavioral response to antidepressant.

It is currently unclear whether antidepressants directly or indirectly induce LPAR1 activation. The CellKeyTM assay showed that antidepressants rapidly induced Gαi/o activation, indicating that antidepressants directly activate LPAR1 in astroglial cells. A previous study reported that several classes of antidepressants accumulate in the lipid rafts formed on the plasma membrane (24). Lipid rafts serve as a signaling platform for G protein-coupled receptor clustering, including LPAR1 (25, 26). Thus, it is a possibility that antidepressants interact with LPAR1 in the lipid raft microdomains of cells. Identifying LPAR1 as an antidepressant binding site could be the next step to lead to the development of novel antidepressants based on LPAR1 activation.

Experimental Procedures

All experimental procedures were performed according to the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hiroshima University, and followed the Guideline for Animal Experiments for National Hospital Organization Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center.

Reagents

Reagents were obtained from the following sources: amitriptyline and mianserin (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan); SU5402 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany); fluoxetine and nortriptyline (Sigma); PTX and U0126 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA); 1-oleoyl LPA and Ki16425 (Cayman, MI); AM966 (Medchem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ), and H2L5186303 (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN).

Cell Culture and Drug Treatment

Preparation of C6 cells has been described previously (8). Primary astrocytes and neurons were prepared from 1-day-old neonatal Wistar rats, as described previously (27). Primary astrocytes in culture for 3 weeks were used. Primary neurons in culture for 2 weeks were used and were considered well differentiated, mature neurons (27).

The concentrations of amitriptyline (25 and 50 μm) used in this report are not toxic to C6 cells/primary astrocytes (7, 27). Antidepressants accumulate in the brain at concentrations severalfold higher than that in plasma, because of their high lipophilic properties (28, 29). In the current study, to replicate clinical brain concentrations and to standardize across antidepressants, all antidepressants were applied to the cells at a concentration of 25 μm.

To determine whether LPAR1 is involved in antidepressant-evoked GDNF expression and to characterize the transactivation pathway, cells were incubated with AM966 (1 μm), Ki16425 (1 μm), H2L5186303 (1 μm), PTX (100 ng/ml), SU5402 (25 μm), or U0126 (10 μm). Concentrations of these inhibitors were based on previous reports (8, 30), which were selective for their respective targets.

RNA Extraction and Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. First strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bioscience, Shiga, Japan). Real-time PCR was performed with the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System II (Takara Bioscience), using TaqMan probes and primers for rat GDNF and GAPDH (Rn00569510_m1 and Rn99999916_s1, respectively; Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA).

CellKeyTM Assay

The CellKeyTM assay, a label-free cell-based assay that detects G-protein activation, has been described previously (8). Briefly, C6 cells were cultured on a standard CellKeyTM 96-well microplate. Just before assay, cells were washed with assay buffer (Hanks' balanced salt solution with 20 mm HEPES and 0.1% BSA) and allowed to equilibrate in the assay buffer for 30 min at 29 °C. The CellKeyTM instrument applied small voltages every 10 s and measured the impedance of the cell layer (ΔZ). In this study, a 5-min baseline was recorded, drugs were added, and then ΔZ was measured for 10 min. The data were quantified using ΔZ at 10 min after drug injection.

Immunoblotting Analysis

The following antibodies were used: phospho-FRS2α (Tyr-196) (number 3864), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (number 9101), and phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (number 4370) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); FRS2α (SNT1), (Sigma); EDG2 (LPAR1) (ab23698) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); LPAR2 (sc25490) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); and LPAR3 (ALR-033) (Alomone Labs., Jerusalem, Israel). Briefly, the proteins (20 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transblotted to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the respective antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescent detection was performed using Immun-StarTM WesternCTM Kit (Bio-Rad), and the net intensities of each band were quantified using ChemiDocTM XRS+ (Bio-Rad) (27).

Small Interfering RNA

Small interfering RNA (8) were used to suppress expression of LPAR1, LPAR2, and LPAR3 in C6 cells. The cells were transfected with either 20 nm siRNA targeting rat LPAR1, LPAR2, LPAR3, or non-targeting siRNA (siGENOME, GE Healthcare) by using RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

GDNF release assay has been described previously (8). Briefly, C6 cells were cultured on 12-well plates. After drug treatment, the concentrations of GDNF protein in cell-conditioned media were determined using a GDNF Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences among the means were determined using one-way analysis of variance with pairwise comparison carried out by Bonferroni's method. Differences between two groups were statistically analyzed with Student's t test. p values at less than 0.05 were taken as statistically significant.

Author Contributions

N. K., K. M., and M. O. T. conducted the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. H. A. and K. I. performed the experimental support, analyzed the data, and prepared the figures. K. H. N. and N. M. prepared rat primary cultured astrocytes and neurons and conducted the experiments (supplemental Fig. S2). Y. U. and M. T. designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Aldric T. Hama for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grants 25860199, 15K09819, 15K08686, 16K08568, 16K19796, and 16K18883 and a grant from SENSHIN Medical Research. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

N. Kajitani, K. Miyano, M. Okada-Tsuchioka, H. Abe, K. Itagaki, K. Hisaoka-Nakashima, N. Morioka, Y. Uezono, and M. Takebayashi, unpublished data.

- GDNF

- glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- LPAR1

- lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1

- PTX

- pertussis toxin

- FGFR

- fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FRS2α

- FGFR substrate 2α.

References

- 1. Sanacora G., and Banasr M. (2013) From pathophysiology to novel antidepressant drugs: glial contributions to the pathology and treatment of mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 1172–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen N. J., and Barres B. A. (2009) Neuroscience: Glia-more than just brain glue. Nature 457, 675–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin P. Y., and Tseng P. T. (2015) Decreased glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with depression: a meta-analytic study. J. Psychiatr Res. 63, 20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang X., Zhang Z., Xie C., Xi G., Zhou H., Zhang Y., and Sha W. (2008) Effect of treatment on serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in depressed patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32, 886–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uchida S., Hara K., Kobayashi A., Otsuki K., Yamagata H., Hobara T., Suzuki T., Miyata N., and Watanabe Y. (2011) Epigenetic status of Gdnf in the ventral striatum determines susceptibility and adaptation to daily stressful events. Neuron 69, 359–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kajitani N., Hisaoka-Nakashima K., Morioka N., Okada-Tsuchioka M., Kaneko M., Kasai M., Shibasaki C., Nakata Y., and Takebayashi M. (2012) Antidepressant acts on astrocytes leading to an increase in the expression of neurotrophic/growth factors: differential regulation of FGF-2 by noradrenaline. PLoS ONE 7, e51197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hisaoka K., Takebayashi M., Tsuchioka M., Maeda N., Nakata Y., and Yamawaki S. (2007) Antidepressants increase glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor production through monoamine-independent activation of protein tyrosine kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in glial cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 321, 148–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hisaoka-Nakashima K., Miyano K., Matsumoto C., Kajitani N., Abe H., Okada-Tsuchioka M., Yokoyama A., Uezono Y., Morioka N., Nakata Y., and Takebayashi M. (2015) Tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline-induced glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor production involves pertussis toxin-sensitive Gαi/o activation in astroglial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 13678–13691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hisaoka K., Tsuchioka M., Yano R., Maeda N., Kajitani N., Morioka N., Nakata Y., and Takebayashi M. (2011) Tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline activates fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in glial cells: involvement in glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor production. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21118–21128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin M. E., Herr D. R., and Chun J. (2010) Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptors: signaling properties and disease relevance. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 91, 130–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yung Y. C., Stoddard N. C., Mirendil H., and Chun J. (2015) Lysophosphatidic acid signaling in the nervous system. Neuron 85, 669–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santin L. J., Bilbao A., Pedraza C., Matas-Rico E., López-Barroso D., Castilla-Ortega E., Sánchez-López J., Riquelme R., Varela-Nieto I., de la Villa P., Suardíaz M., Chun J., De Fonseca F. R., and Estivill-Torrús G. (2009) Behavioral phenotype of maLPA1-null mice: increased anxiety-like behavior and spatial memory deficits. Genes Brain Behav. 8, 772–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olianas M. C., Dedoni S., and Onali P. (2015) Antidepressants activate the lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA(1) to induce insulin-like growth factor-I receptor transactivation, stimulation of ERK1/2 signaling and cell proliferation in CHO-K1 fibroblasts. Biochem. Pharmacol. 95, 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miyano K., Sudo Y., Yokoyama A., Hisaoka-Nakashima K., Morioka N., Takebayashi M., Nakata Y., Higami Y., and Uezono Y. (2014) History of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) assays from traditional to a state-of-the-art biosensor assay. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 126, 302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hisaoka K., Nishida A., Koda T., Miyata M., Zensho H., Morinobu S., Ohta M., and Yamawaki S. (2001) Antidepressant drug treatments induce glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) synthesis and release in rat C6 glioblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 79, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao J., Wei J., Bowser R. K., Dong S., Xiao S., and Zhao Y. (2014) Molecular regulation of lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 trafficking to the cell surface. Cell Signal. 26, 2406–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sato K., Horiuchi Y., Jin Y., Malchinkhuu E., Komachi M., Kondo T., and Okajima F. (2011) Unmasking of LPA1 receptor-mediated migration response to lysophosphatidic acid by interleukin-1β-induced attenuation of Rho signaling pathways in rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 117, 164–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kowal D., Zhang J., Nawoschik S., Ochalski R., Vlattas A., Shan Q., Schechter L., and Dunlop J. (2002) The C-terminus of Gi family G-proteins as a determinant of 5-HT(1A) receptor coupling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fong H. K., Yoshimoto K. K., Eversole-Cire P., and Simon M. I. (1988) Identification of a GTP-binding protein α subunit that lacks an apparent ADP-ribosylation site for pertussis toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3066–3070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuoka M., Itoh H., Kozasa T., and Kaziro Y. (1988) Sequence analysis of cDNA and genomic DNA for a putative pertussis toxin-insensitive guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein α subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 5384–5388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McAlhany R. E. Jr., Miranda R. C., Finnell R. H., and West J. R. (1999) Ethanol decreases Glial-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF) protein release but not mRNA expression and increases GDNF-stimulated Shc phosphorylation in the developing cerebellum. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 23, 1691–1697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Sampaio E Spohr T. C., Choi J. W., Gardell S. E., Herr D. R., Rehen S. K., Gomes F. C., and Chun J. (2008) Lysophosphatidic acid receptor-dependent secondary effects via astrocytes promote neuronal differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7470–7479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galeotti N., Bartolini A., and Ghelardini C. (2002) Role of Gi proteins in the antidepressant-like effect of amitriptyline and clomipramine. Neuropsychopharmacology 27, 554–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Erb S. J., Schappi J. M., and Rasenick M. M. (2016) Antidepressants accumulate in lipid rafts independent of monoamine transporters to modulate redistribution of the G protein, Gαs. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 19725–19733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Allen J. A., Halverson-Tamboli R. A., and Rasenick M. M. (2007) Lipid raft microdomains and neurotransmitter signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 128–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Urs N. M., Jones K. T., Salo P. D., Severin J. E., Trejo J., and Radhakrishna H. (2005) A requirement for membrane cholesterol in the β-arrestin- and clathrin-dependent endocytosis of LPA1 lysophosphatidic acid receptors. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5291–5304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kajitani N., Hisaoka-Nakashima K., Okada-Tsuchioka M., Hosoi M., Yokoe T., Morioka N., Nakata Y., and Takebayashi M. (2015) Fibroblast growth factor 2 mRNA expression evoked by amitriptyline involves extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent early growth response 1 production in rat primary cultured astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 135, 27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyake K., Fukuchi H., Kitaura T., Kimura M., Sarai K., and Nakahara T. (1990) Pharmacokinetics of amitriptyline and its demethylated metabolite in serum and specific brain regions of rats after acute and chronic administration of amitriptyline. J. Pharm. Sci. 79, 288–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glotzbach R. K., and Preskorn S. H. (1982) Brain concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants: single-dose kinetics and relationship to plasma concentrations in chronically dosed rats. Psychopharmacology 78, 25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rancoule C., Pradère J. P., Gonzalez J., Klein J., Valet P., Bascands J. L., Schanstra J. P., and Saulnier-Blache J. S. (2011) Lysophosphatidic acid-1-receptor targeting agents for fibrosis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 20, 657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.