Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study is to describe the demographics and duration of symptoms of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome who present with muscle atrophy. Methods: We identified 146 patients who presented to the hand surgery clinic at a single institution over a 5-year period with an initial diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome based on history and physical examination. Medical records were retrospectively reviewed to determine if there was a difference in demographic data, physical examination findings, and duration of symptoms in patients who presented with muscle atrophy from those with sensory complaints alone. Results: A total of 17/146 (11.6%) of patients presented with muscle atrophy, all of which were men. In all, 17.2% of men presented with atrophy. Age by itself was not a predictor of presentation with atrophy; however, younger patients with atrophy presented with significantly shorter duration of symptoms. Patients under the age of 29 years presenting with muscle atrophy on average had symptoms for 2.4 months compared with 16.2 months of symptoms for those over 55 years of age. Conclusions: Men with cubital tunnel syndrome are more likely to present with muscle atrophy than women. Age is not necessarily a predictor of presentation with atrophy. There is a subset population of younger patients who presents with extremely short duration of symptoms that rapidly develops muscle atrophy.

Keywords: cubital tunnel syndrome, elbow, muscle atrophy, neuropathy, ulnar nerve

Introduction

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common compressive neuropathy of the upper extremity after carpal tunnel syndrome.6 The entity is defined by compression of the ulnar nerve at several potential sites about the elbow. Patients frequently present with complaints of paresthesia in the distribution of the ulnar nerve and hand clumsiness or weakness. Prior studies have suggested that muscle atrophy at presentation of cubital tunnel syndrome is 4 times more common than in carpal tunnel syndrome7 and that in the setting of positive electrodiagnostic studies, weakness is found 82% of the time.1 Patients who develop intrinsic muscle atrophy are thought to have a worse prognosis,3,9 and surgical treatment is recommended before the onset of muscle atrophy.8,12

In the current study, we seek to determine the presenting features and characteristics of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome and determine any correlations with atrophy at initial presentation. We hypothesized there was a subset of younger patients who present with the rapid onset of muscle atrophy. After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval, we tested this hypothesis by reviewing medical records of patients in a single tertiary level medical center over a 5-year period who presented with a diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a query of the electronic medical records for ulnar neuropathy over a 5-year period (2007-2011). Inclusion criteria were age greater than 18 years and documented initial diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome seen in the orthopedic surgery clinic. Patients with cervical nerve root compression, traumatic ulnar nerve injuries, brachial plexus injuries, systemic diseases known to affect peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junction disorders, or fracture malunion about the elbow were excluded. We collected demographic data, presenting complaints, physical exam findings, and ultimate treatment course.

The diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome was established based on patient complaints of numbness and tingling into the ring and small finger or hand weakness in conjunction with physical exam findings suggestive of compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Electrodiagnostic studies were obtained for patients with atypical presentation for cubital tunnel syndrome and in those instances in which the presence of exclusion criteria were suspected. If there was a visible side to side difference in intrinsic muscle bulk, atrophy was noted in the record.

Statistical analysis was performed to determine significant demographic or physical exam findings that correlated with atrophy at presentation. Fisher’s exact tests and chi-square tests were used for categorical analyses and a t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were done to compare symptom duration for atrophy at time of presentation by age. Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) was used to determine significance of post hoc comparisons between age categories. The symptom duration data were logged for analysis to enhance normality. All analyses were done in SAS v. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A significance level of P < .05 was used for all analyses.

Results

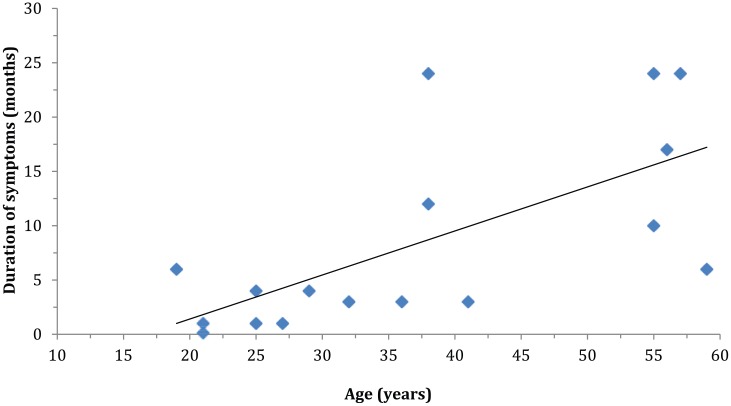

A total of 193 patients with ulnar neuropathy were identified. Twenty-three were excluded due to lack of documentation regarding atrophy, and 24 were excluded based on previously listed criteria. Hence, 146 patients were included in the data analysis. The mean age of included patients was 37.8 (SD = 11.6), with ages ranging from 19 to 63 (median = 37). There were 99 men (68%) and 47 women (32%). At the time of diagnosis, 11.6% of study patients presented with muscle atrophy. In all, 17.2% of men presented with atrophy, and no females were affected (P = .002; Table 1). Positive physical exam findings of Froment’s sign (P ≤ .001) and Wartenburg’s sign (P ≤ .001) correlated with the presence of atrophy, while Tinel’s signs (P = .362), elbow flexion test (P = .351), and numbness/tingling (P = 1.000) did not. The prevalence of atrophy did not differ by age (12% for patients <38 vs. 11% for patients 38 and older, P = 1.000; Table 2). When subgroup analysis was performed for those with atrophy, a distinct trend was found with regard to age and duration of symptoms. Among the 17 patients who presented with atrophy, younger patients had a significantly shorter duration of symptoms than older patients (2.4 months mean duration for patients 19-29 years vs. 9 months for patients 32-41 years vs. 16.2 months for patients 55-59 years, P = .012; Table 3 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Data.

| Overall | Male | Female | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 146 | 99 (68%) | 47 (32%) | |

| Age (years) | 37.8 (SD = 11.6) | 39.8 (SD = 11.9) | 33.7 (SD = 10.1) | .003 |

| Handedness | 91% RHD | 89% RHD | 95% RHD | .326 |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 20.1 | 21.7 | 16.7 | .848 |

| Muscle atrophy at presentation | 17 | 17 (100%) | 0 (0%) | .002 |

Note. Mean age at presentation was significantly different between males (39.8) and females (33.7). Significant difference was also noted between males (100%) and females (0%) with regard to muscle atrophy at presentation. No significant differences were noted between males and females with respect to handedness or duration of symptoms. RHD = right hand dominant.

Table 2.

Atrophy Correlated With Demographics and Physical Exam Findings.

| Value | Total patients | With atrophy (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 146 | 17 (11.6) | ||

| Age | 19-37 | 74 | 9 (12.2) | 1 |

| >38 | 72 | 8 (11.1) | ||

| Gender | Male | 99 | 17 (17.2) | .002 |

| Female | 47 | 0 (0) | ||

| Froment’s sign | Positive | 7 | 5 (71.4) | <.001 |

| Negative | 106 | 3 (2.8) | ||

| Wartenburg’s sign | Positive | 9 | 5 (55.6) | <.001 |

| Negative | 112 | 8 (7.1) | ||

| Tinel’s sign | Positive | 133 | 7 (5.3) | .362 |

| Negative | 11 | 0 (0) | ||

| Elbow Flexion Test | Positive | 93 | 9 (9.7) | .351 |

| Negative | 16 | 0 (0) | ||

| Numbness/tingling | Positive | 141 | 17 (12.1) | 1 |

| Negative | 5 | 0 (0) |

Note. The prevalence of muscle atrophy did not differ by age (12.2% for patients <38 vs. 11.1% for patients 38 and older). In all, 11.6% of patients presented with atrophy at the time of diagnosis. In all, 17.2% of men and no females presented with atrophy. Positive physical exam findings of Froment’s sign and Wartenburg’s sign correlated with the presence of muscle atrophy, while Tinel’s sign, elbow flexion test, and numbness/tingling did not.

Table 3.

Duration of Symptoms Versus Age for Patients Presenting With Atrophy.

| Age groups (years) | Number of patients | Mean duration of symptoms (months) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19-29 | 7 | 2.4 (SD = 2.2) | .012 (overall) |

| 32-41 | 5 | 9.0 (SD = 9.2) | .119 (19-29 vs. 32-41) |

| 55-59 | 5 | 16.2 (SD = 8.1) | .004 (19-29 vs. 55-59) |

| .113 (32-41 vs. 55-59) |

Note. Of the17 patients who presented with atrophy, younger patients had a significantly shorter duration of symptoms than older patients (2.4 months mean duration for patients 19-29 years vs. 9 months for patients 32-41 years vs. 16.2 months for patients 55-59 years, P = .012).

Figure 1.

Duration of symptoms versus age for patients presenting with atrophy.

Note. Scatter plot demonstrating that among the patients who presented with atrophy at initial evaluation, there was a distinct trend toward decreased duration of symptoms with decreasing patient age.

Discussion

This study reports the presenting characteristics of a large group of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome. Our study population provides insight into the presentation of cubital tunnel syndrome in a younger group, which may be different from prior studies with average age greater than 45 years.2,3,4,12 Mallet et al12 demonstrated that age was significantly predictive of atrophy while gender was not, in a study group with average age of 54 years and 59% men. Naran et al10 also found that age was a significant predictor of atrophy at presentation within a group of average age of 55 years with 77% women. We found in our younger population, gender was highly predictive of atrophy, while age was not. This difference may be due to the possibility that cubital tunnel syndrome is not a homogeneous entity and has variable presentations relating to the age group involved.

Among patients presenting with atrophy, duration of symptoms correlated with age. We are unaware of prior reports in which young patients presented with such a rapid development of atrophy after the onset of sensory symptoms. Stutz et al11 reported on a series of pediatric and adolescent patients with cubital tunnel syndrome. They found nonsurgical management of cubital tunnel syndrome to be less successful in this age group, with an average of 7 months of conservative measures before proceeding to surgery. We found a subgroup of young males with cubital tunnel syndrome that rapidly progress to muscle atrophy. This is relevant in that surgical outcomes are inferior in patients who already demonstrate intrinsic muscle atrophy.1,2,4 This would argue against a long period of nonoperative management in these patients at risk for rapid development of atrophy.

This study has potential limitations. The nature of retrospective chart reviews is that a full set of data is often not available for all eligible patients. The study can also be criticized for lack of objective electrodiagnostic testing to establish the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome in all patients. However, Greenwald demonstrated that excellent surgical outcomes can be obtained without electrodiagnostics.5 Therefore, clinical examination alone is likely sufficient to establish the diagnosis. Finally, patient’s reporting of duration of symptoms prior to initial presentation is potentially subject to recall bias.

Our data suggest that in younger patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, consideration should be given to earlier surgical treatment due to the concern for more rapid onset of muscle atrophy, which may not be reversible.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This was a retrospective review of existing data. Identifying information was not utilized.

Statement of Informed Consent: Written informed consent was not obtained from patients prior to being included in this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bushbacher R. Side-to-side confrontational strength-testing for weakness of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79A:401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dellon AL, Henk JC. Results of the musculofascial lengthening technique for submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85A:1314-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foster RJ, Edshage S. Factors related to the outcome of surgically managed compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow level. J Hand Surg Am. 1981;6:181-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldberg BJ, Light TR, Blair SJ. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: Results of medial epicondylectomy. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14A:182-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenwald D, Blum LC, Adams D, Mercantonio C, Moffit M, Cooper B. Effective surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome based on provocative clinical testing without electrodiagnostics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Latinovic R, Gulliford MC, Hughes RAC. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:263-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mallete P, Zhao M, Zurakowski D, Ring D. Muscle atrophy at diagnosis of carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32A:855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsuzaki H, Yoshizu T, Maki Y, Tsubokawa N, Yamamoto Y, Toishi S. Long-term clinical and neurologic recovery in the hand after surgery for severe cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29A:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mowlavi AM, Andrews K, Lille S, Verhulst S, Zook EG, Milner S. The management of cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naran S, Imbriglia JE, Bilonick RA, Taieb A, Wollstein R. A demographic analysis of cubital tunnel syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:177-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stutz C, Calfee R, Steffen J, Goldfarb C. Surgical and nonsurgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome in pediatric and adolescent patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:657-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomaino MM, Brach PJ, Vansickle DP. The rationale for and efficacy of surgical intervention for electrodiagnostic-negative cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26A:1077-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]