Abstract

Background

Prevention strategies for pressure ulcer formation remain critical in patients with an advanced illness. We analyzed factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers in patients hospitalized in a palliative care ward setting.

Patients and methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of 329 consecutive patients with a mean age (± standard deviation) of 70.4±11.8 years (range: 30–96 years, median 70.0 years; 55.3% women), who were admitted to the Palliative Care Department between July 2012 and May 2014.

Results

Patients were hospitalized for mean of 24.8±31.4 days (1–310 days, median 14 days). A total of 256 patients (77.8%) died in the ward and 73 patients (22.2%) were discharged. Two hundred and six patients (62.6%) did not develop pressure ulcers during their stay in the ward, 84 patients (25.5%) were admitted with pressure ulcers, and 39 patients (11.9%) developed pressure ulcers in the ward. Four factors assessed at admission appear to predict the development of pressure ulcers in the multivariate logistic regression model: Waterlow score (odds ratio [OR] =1.140, 95% confidence interval [CI] =1.057–1.229, P=0.001), transfer from other hospital wards (OR =2.938, 95% CI =1.339–6.448, P=0.007), hemoglobin level (OR =0.814, 95% CI =0.693–0.956, P=0.012), and systolic blood pressure (OR =0.976, 95% CI =0.955–0.997, P=0.023). Five other factors assessed during hospitalization appear to be associated with pressure ulcer development: mean evening body temperature (OR =3.830, 95% CI =1.729–8.486, P=0.001), mean Waterlow score (OR =1.194, 95% CI =1.092–1.306, P<0.001), the lowest recorded sodium concentration (OR =0.880, 95% CI =0.814–0.951, P=0.001), mean systolic blood pressure (OR =0.956, 95% CI =0.929–0.984, P=0.003), and the lowest recorded hemoglobin level (OR =0.803, 95% CI =0.672–0.960, P=0.016).

Conclusion

Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may contribute to the formation of pressure ulcers in patients with an advanced illness.

Keywords: pressure ulcers, palliative care, advanced illness, Waterlow score, hyponatremia, blood pressure

Introduction

Pressure ulcers represent a frequent and significant challenge for medical, nursing, and social care systems among the elderly, disabled, and other patient populations.1–6 Deterioration of physical, psychological, and social health due to pressure ulcers within susceptible patients is often devastating7,8 and increases the risk of death.9 While prolonged skin pressure, shear stress, and/or friction are primary causal factors leading to ulcer formation, variability of pressure ulcer risk factors, prevalence, incidence, and prognosis have been observed in different patient populations.1–3 Advanced chronic illness, defined as patients receiving supportive and palliative care,10 combined with nutritional deterioration, weakness, immobility, and skin alterations, is particularly associated with the risk of pressure ulcer development.1,3,10 Excessive skin moisture, urine or fecal incontinence, and urinary catheterization are other factors that have previously been shown to increase pressure ulcer incidence in terminally ill patients.3 Major surgery may contribute to increased formation of pressure ulcers in patients with colorectal cancer.11 Advanced age, alterations to sensory perception, body temperature alterations, as well as poor general and mental health are conditions that can augment the individual risk for pressure ulcer development.3 Pressure ulcerations may result from impaired tissue perfusion and oxygenation as sequelae of general health-related conditions12 or local factors (peripheral vascular disease, diminished skin vascular density).13 Ischemia-reperfusion injury is an additional major component that participates in cutaneous necrosis.14 Wound formation is followed by inflammation that may cause further perfusion deterioration15 and impair wound healing if uncontrolled.16 Infection is a common, potentially serious pressure ulcer complication with local and systemic effects.17 Nearly all individuals in palliative care are susceptible to pressure ulcer development; thus, risk assessment and prevention strategies are strongly recommended.3 Pressure ulcer prevention is an essential component of palliative care for maintaining patient quality of life.1 Prevention of pressure ulcer formation has been shown to be a cost-effective endeavor.18,19 Studies have shown that treatment costs of severe pressure ulcers are significantly higher than prevention strategy implementation.2,20 In addition, the lack of effective pressure ulcer formation prevention strategies may expose providers to financial liability.21 While there is an increased understanding of the conditions associated with pressure sore development among palliative care patients, the need for further investigations on this important topic has been raised.10 Many of the prevention strategies that have been previously described focus on outpatient and acute hospital settings. However, inpatient pressure ulcer prevention strategies remain critical for respite care among palliative patients.1 Our objective was to analyze factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients with advanced illness.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective analysis of factors that influence pressure ulcers in patients with an advanced illness based on medical records of the Palliative Care Unit of Independent Public Healthcare Railway Hospital in Wilkowice-Bystra, Poland.

Patients

The analysis included 329 consecutive patients admitted to the Palliative Care Department between July 2012 and May 2014, with a mean age (± standard deviation) of 70.4±11.8 years (range: 30–96 years, median 70.0). Of the patients admitted, 55.3% were women and 44.7% were men.

Procedures

Patient diagnosis, treatment, and care were in accordance with hospice care standards of the Ministry of Health and the National Health Fund of Poland. Prevention strategies were applied uniformly and consistently to all patients (Table 1). As part of standard operating procedures, patient admissions were subject to standardized history taking, physical examination, functional assessment, and laboratory tests. In addition, assessment of nutritional status and acute and chronic pain with emphasis on cancer pain was applied. Functional assessment included the Barthel index.22 Blood tests included complete blood count, electrolytes, uric acid concentration, and arterial blood gas analysis. The patients were evaluated daily, and blood tests were repeated according to clinical indications. Sodium and potassium were assessed several times during hospitalization. Within 2 hours of admission, the risk of decubitus pressure ulcer formation was assessed using the Waterlow scale,23 assessed daily and the mean calculated. Waterlow scale is scored from 0 to 64. Waterlow scores ≥10 indicate increased risk of pressure ulcer development, ≥15 a high risk, and ≥20 a very high risk.

Table 1.

Pressure ulcer prevention strategies applied in the Palliative Care Unit at Independent Public Healthcare Railway Hospital in Wilkowice–Bystra, Poland

| I. Risk assessment and management of pressure ulcers |

| 1. Comprehensive medical and nursing assessment (including patient mobility, nutritional status, edema, inspection for skin lesions especially in areas of bony prominences) with pressure ulcer risk evaluation (Waterlow scale23) at admission for all patients using a standardized individual patient questionnaire |

| 2. Regular pressure ulcer risk reassessment once a week or more frequently if patient state deteriorates |

| 3. Collaboration with the therapeutic team to determine the optimal management of each patient |

| 4. Additional pressure ulcer prevention strategies applied if the Waterlow scale score ≥10 points |

| 5. Yearly analysis and review of pressure ulcer development statistics and assessment of prevention strategy effectiveness |

| 6. Regular staff training focused on pressure ulcer risk assessment and pressure ulcer prevention and treatment |

| 7. Patient and caregiver education (including adequate hydration, feeding, dressing, and physical activity maintenance) |

| II. Management of increased pressure ulcer risk |

| 1. Patient mobility and frequent body position adjustment is encouraged |

| 2. Proper body positioning and turning at least every 2 hours if patient mobility is impaired |

| 3. Appropriately lifting and moving patients with sufficient personnel to avoid injury |

| 4. Utilization of pressure-reducing or pressure-relieving devices (eg, alternating pressure mattress) |

| 5. Instructing and assisting patients to shift their weight at least every 30 minutes when using a wheel chair |

| 6. Skin inspection during assisted body positioning and bathing |

| 7. Gentle skin bathing (once a day and when needed, mild hypoallergenic soap, skin folds, and opposing skin surfaces; thorough drying of skin with special attention given to skin folds; application of moisturizing lotion or emollient) |

| 8. Patients given soft cotton or linen underwear and clean, dry, wrinkle-free bed linen, which is replaced when necessary |

| 9. Effective skin protection from contact with urine and feces |

| 10. Adequate hydration and feeding (with a focus on proper protein intake) |

| 11. Individualized rehabilitation programs, including physiotherapy, for maintenance of mobility |

| 12. Continued patient and caregiver education aimed at patient mobility and cooperation |

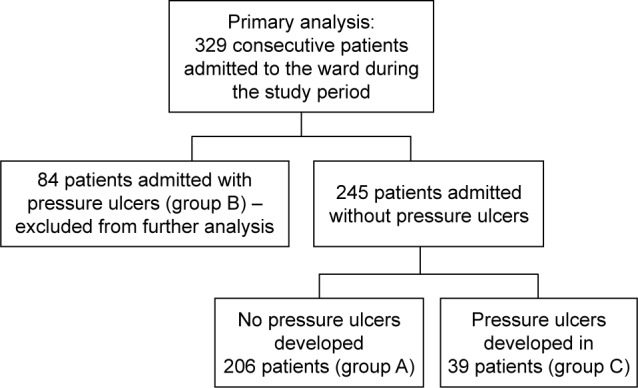

Patients were classified according to decubitus pressure ulcer development: group A included patients who avoided pressure ulcer development, group B included patients admitted to the ward with pressure ulcers, and group C included patients who developed pressure ulcers in the ward.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistica version 10 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Chi-square test, V-square test, and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables and nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for quantitative variables to compare patients who developed decubitus pressure ulcers during hospitalization with those who did not. Multivariate binary logistic regression was performed to assess measures associated with decubitus pressure ulcer development: separately for parameters assessed at admission and for mean values of parameters measured serially during hospitalization. The variables were adjusted for clinical, functional, and laboratory factors. Multivariate analysis with backward elimination included variables that yielded P-values of 0.1 or lower in the initial univariate analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate probability of pressure ulcer-free hospitalization in subgroups of patients in respect to selected variables, while differences between these subgroups were assessed with the Gehan’s Generalized Wilcoxon statistic. Variables were tested to define the value corresponding with the lowest P-level. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study protocol was registered with and approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Bielsko–Biala (Komisja Bioetyczna Beskidzkiej Izby Lekarskiej w Bielsku-Bialej, Letter No 2014/07/17/7 July 17th 2014). Since our study is a retrospective analysis, patient consent for medical record review was not required by the Bioethical Committee.

Results

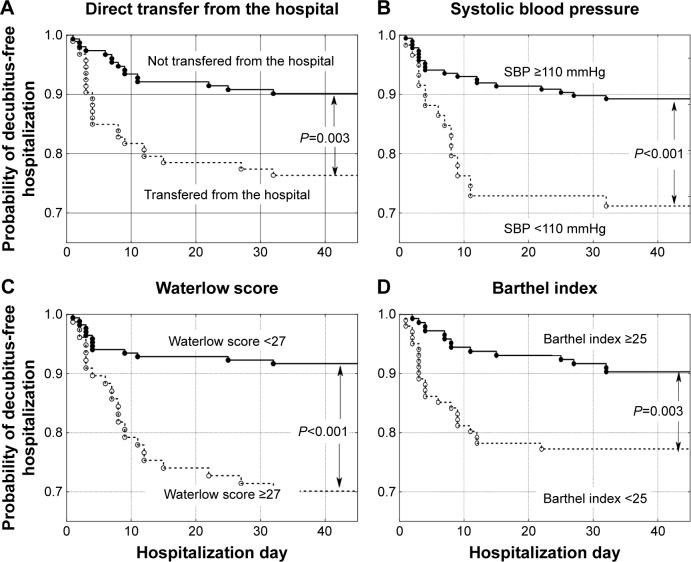

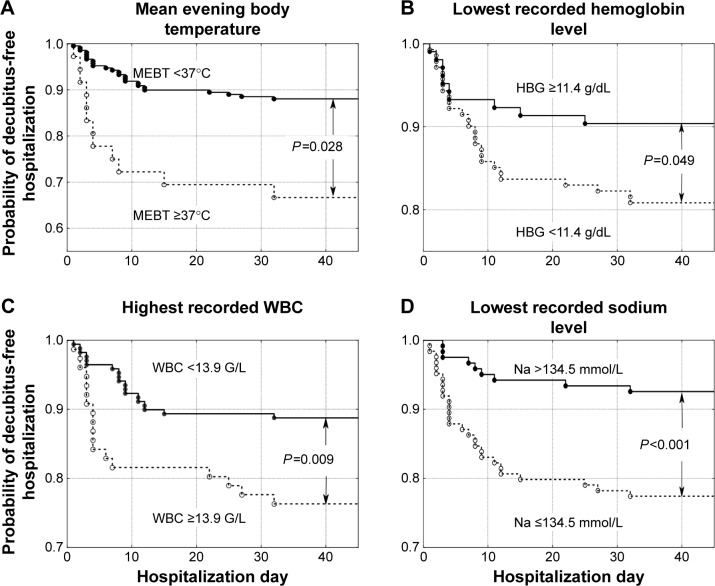

Patients were hospitalized for a mean of 24.8±31.4 days, ranging from 1–310 days (median 14 days). A total of 256 patients (77.8%) died in the ward, while 73 (22.2%) were discharged. In total, 313 patients (95.1%) suffered from cancer: lung cancer (21.3%), colorectal cancer (11.6%), breast cancer (6.1%), brain cancer (5.8%), stomach cancer (5.8%), and other cancer (44.5%). Sixteen patients (4.9%) were admitted because of non-oncological diseases, mostly (13 patients, 4.0%) because of severe chronic heart failure. Two hundred and six patients (62.6%) did not develop pressure ulcers during their stay in the ward (group A), 84 patients (25.5%) were admitted to the ward with pressure ulcers (group B), and 39 patients (11.9%,) developed pressure ulcers while in the ward (group C). Group C and group A (as a control) were included in further analysis (Figure 1). Compared to patients who did not develop pressure ulcers during hospitalization (group A), patients who developed pressure ulcers (group C) presented more frequently with colorectal cancer, higher body mass reduction within 6 months, a longer period of physical deterioration, longer pre-admission nursing home residency, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lower hemoglobin level, and higher white blood cell count at admission, as well as lower Barthel index and Waterlow scores at admission (Table 2). Patients directly transferred from other hospital wards presented with lower Barthel index scores (29.8±24.8 vs 40.0±25.6 points, P=0.001). Individuals who were not transferred directly from other hospital wards had higher probability of decubitus pressure ulcer-free hospitalization (P=0.003) as did those with systolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg (P<0.001), Waterlow scores <27 points (P<0.001), and Barthel index scores ≥25 points (P=0.003) (Figure 2), as well as those with a mean evening body temperature <37°C, lowest recorded hemoglobin level ≥11.4 g/dL, highest recorded white blood cells <13.9 G/L, and lowest recorded sodium level >134.5 mmol/L (Figure 3). Four factors assessed at admission appear predictive for pressure ulcer development in a multivariate logistic regression model: Waterlow score (odds ratio [OR] =1.140, 95% CI =1.057–1.229, P=0.001), patients admitted from other hospital wards (OR =2.938, 95% CI =1.339–6.448, P=0.007), hemoglobin level (OR =0.814, 95% CI =0.693–0.956, P=0.012), and systolic blood pressure (OR =0.976, 95% CI =0.955–0.997, P=0.023). Five factors assessed during hospitalization appear to be associated with decubitus pressure ulcer development: mean evening body temperature (OR =3.830, 95% CI =1.729–8.486, P=0.001), mean Waterlow score (OR =1.194, 95% CI =1.092–1.306, P<0.001), the lowest recorded sodium concentration (OR =0.880, 95% CI =0.814–0.951, P=0.001), mean systolic blood pressure (OR =0.956, 95% CI =0.929–0.984, P=0.003), and the lowest recorded hemoglobin level (OR =0.803, 95% CI =0.672–0.960, P=0.016).

Figure 1.

Study population inclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic, clinical, and functional characteristics of hospice patients who developed (group C) and did not develop (group A) pressure ulcers while hospitalized

| Variable | Group C n=39 |

Group A n=206 |

Group C vs group A |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Mean ± SD or % | P-value | ||

| Age, years | 71.5±11.4 | 69.8±11.9 | 0.534 |

| Sex, proportion of women, % | 56.4 | 55.3 | 0.948 |

| Lung cancer patients, % | 15.4 | 22.3 | 0.425 |

| Colorectal cancer patients, % | 28.2 | 11.2 | 0.011 |

| Breast cancer patients, % | 5.1 | 6.3 | 0.922 |

| Brain tumor patients, % | 0.0 | 6.8 | 0.217 |

| Stomach cancer patients, % | 10.3 | 6.3 | 0.631 |

| Disseminated cancer of unknown origin patients, % | 2.6 | 5.3 | 0.764 |

| Nononcological patients with advanced heart failure, % | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.406 |

| Patients with coexisting dementia, % | 17.9 | 7.8 | 0.078 |

| Patients with coexisting hypertension, % | 46.2 | 45.1 | 0.943 |

| Patients with coexisting diabetes, % | 20.5 | 24.3 | 0.680 |

| Direct transfer from the hospital, % | 56.4 | 34.5 | 0.099 |

| Preadmission nursing home residency, days | 13.1±32.2 | 7.8±20.3 | 0.049 |

| Systolic blood pressure at admission, mmHg | 111.2±16.4 | 120.9±19.5 | 0.003 |

| Mean systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 106.1±13.1 | 118.3±16.2 | >0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at admission, mmHg | 66.8±11.5 | 71.9±13.5 | 0.018 |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 64.0±9.0 | 70.6±11.1 | >0.001 |

| Mean evening body temperature, °C | 36.9±0.5 | 36.7±0.4 | 0.014 |

| Hemoglobin level at admission, g/dL | 10.4±2.4 | 11.3±2.6 | 0.037 |

| Lowest recorded hemoglobin level, g/dL | 9.8±2.4 | 11.1±2.5 | 0.005 |

| Highest recorded hemoglobin level, g/dL | 10.6±2.4 | 11.5±2.4 | 0.026 |

| Lowest recorded erythrocyte count, g/L | 3.4±0.8 | 3.7±0.8 | 0.033 |

| White blood cell count at admission, g/L | 12.9±6.2 | 11.0±6.6 | 0.019 |

| Highest recorded white blood cell count, g/L | 14.0±7.0 | 11.8±7.2 | 0.027 |

| Sodium serum concentration at admission, mmol/L | 135.4±7.4 | 135.9±5.8 | 0.456 |

| Lowest recorded sodium concentration, mmol/L | 131.3±5.6 | 135.0±6.0 | >0.001 |

| Breakthrough pain attacks, per day | 0.8±0.8 | 0.6±0.9 | 0.019 |

| Body mass reduction during last 6 months, kg | 8.1±10.8 | 5.0±7.7 | 0.040 |

| Onset of physical deterioration, number of weeks | 3.1±5.0 | 1.6±2.7 | 0.002 |

| Waterlow score at admission, points | 27.4±6.0 | 23.6±5.0 | >0.001 |

| Mean Waterlow score, points | 28.6±4.9 | 24.2±4.8 | >0.001 |

| Barthel index at admission, points | 23.2±16.5 | 38.6±26.4 | 0.001 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Probability of decubitus-free hospitalization in palliative care ward patients according to (A) transfer from home or nursing care settings versus direct transfer from other hospital wards, (B) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥110 mmHg versus lower values, (C) Waterlow scores <27 points versus higher values, and (D) Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living (Barthel index) ≥25 points versus lower values.

Figure 3.

Probability of decubitus-free hospitalization in palliative care ward patients according to (A) mean evening body temperature (MEBT) <37°C versus higher values, (B) lowest recorded hemoglobin level (HBG) ≥11.4 g/dL versus lower values, (C) highest recorded white blood cells (WBC) <13.9 G/L versus higher values, and (D) lowest recorded sodium level >134.5 mmol/L versus lower values.

Discussion

Our study analyzed the risk factors of pressure ulcer formation in a heterogeneous group of patients with an advanced illness, with a mean age of 70.4 years and a median age of 70.0 years, hospitalized at a palliative care unit. Most patients passed away in the unit and only a fifth of the patients were discharged. A majority of the patients suffered from advanced cancer and a minority from other advanced illnesses, mainly chronic heart failure. These conditions are associated with a risk of pressure ulcer formation.10 The Waterlow scale23 was used to assess the risk of pressure ulcer development. Although its predictive value was found to be limited,24,25 it is still recommended for pressure ulcer risk assessment.26 We observed greater pressure ulcer incidence with colorectal cancer, accelerated body mass reduction during the last 6 months, longer periods of physical deterioration, and longer pre-admission nursing home residency. Further multivariate logistic regression analysis identified four independent factors predictive of pressure ulcer formation at admission: direct transfer from hospital ward, high Waterlow score, low hemoglobin level, and low systolic blood pressure at admission. Pressure ulcer development and the association with direct transfer from other hospital wards may be due to the poorer general health status of such patients, who were most likely referred to the Palliative Care Department because of an advanced illness. Low hemoglobin levels may be both a symptom of more advanced disease and a cause of diminished tissue oxygenation. Similarly, blood pressure tends to decrease with chronic disease progression,16 and hypotension may be associated with decreased peripheral tissue perfusion. It is worth noting that hypertensive patients suffering from comorbid chronic diseases are often treated with antihypertensive agents despite very low blood pressure in the context of advanced chronic diseases. Multivariate logistic regression analysis also allowed identification of five other factors assessed during hospitalization and associated with the pressure ulcer formation. We observed that elevated mean evening temperature was a measure associated with pressure ulcer formation. Hyponatremia was not previously considered a factor associated with pressure ulcer formation in patients with advanced diseases. However, there is increasing evidence that the lowest recorded serum sodium level, or hyponatremia, is associated with poorer prognosis in different groups of patients irrespective of underlying disease. Decreased sodium levels, within the normal sodium range, were associated with increased major cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly men without previously diagnosed cardiovascular disease.27 Hyponatremia in patients after acute myocardial infarction was shown to be an independent predictive factor for increased long-term mortality.28 Among internal medicine department inpatients, hyponatremia was associated with increased 30-day and 1-year mortality, regardless of underlying disease. In addition, a decrease of serum sodium from 139 to 132 mmol/L was shown to correlate with an increased risk of death.29 Hyponatremia was also found to increase the risk of falls30 and fractures.8 Our observations suggest that decreased serum sodium is a factor in increased pressure ulcer development risk. It could be assumed that hyponatremia is an index of progressive deterioration in patients with advanced illnesses, which also lowers blood pressure, skin turgor, and peripheral tissue perfusion. This finding needs further study as it may have important implications for the care of patients with advanced illness.

Hyponatremia in terminal patients has been associated with a wide range of detrimental symptoms and signs.31 Establishing the etiology of hyponatremia is essential for treatment. Serum sodium levels are dependent on fluid balance. Low serum sodium levels may be caused by inadequately low sodium intake (dietary restrictions, low sodium content in intravenous fluids), excessive sodium wasting (vomitus, diarrhea, cerebral salt-wasting syndrome [CSWS]), and excessive water retention (syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone [SIADH], heart, or renal failure).32,33 Both diagnosis and treatment of disorders responsible for hyponatremia may be difficult in a palliative patient. A majority of palliative patients suffer from cancer with comorbid conditions. Consequently, hyponatremia in terminal patients is frequently of complex multi-factorial and multi-etiological origin.34,35 If hypothyroidism or adrenal insufficiency is diagnosed, hormone replacement therapy is indicated. Cancer (especially of the lung, breast, head, and neck) is frequently associated with SIADH or (less frequently) CSWS. Hyponatremia secondary to congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, or liver cirrhosis may be resistant to treatment.32 Importantly, a review of pharmacological agents, in terms of potential adverse drug reactions, is warranted. Modification of medications should be implemented where appropriate and feasible. Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may be induced by multiple drugs used frequently in palliative patients, including diuretics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opioids, antiepileptic drugs, neuroleptics, and sulfonylurea derivatives.36 Clinicians must practice vigilance when determining appropriate pharmacological and fluid therapy for terminal patients with multiple conditions in order to avoid the development of hyponatremia. As such, introduction of early medication and dietary (sodium intake) review should be initiated for terminal patients. Such consideration may prove helpful in avoiding serious complications caused by hyponatremia in palliative care patients.

The retrospective nature of this study limited the range of collected data and lacked predefined regular procedures in patient monitoring. In addition, bacteriological cultures were not taken in the patient population studied. Despite these limitations, it seems that our study added new information of potential significance for the prevention of pressure ulcer development in hospitalized patients with advanced illness.

Conclusion

Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may contribute to pressure ulcer formation in patients with advanced illness.

Acknowledgments

The funding for the study was supported by University of Bielsko-Biala, Poland. However, the funding body played no role in the formulation of the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this paper.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Danuta Sternal was involved in study conception and design; evaluation of the subjects; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting the article, and revising drafts. Jan Szewieczek was responsible for study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising drafts. Krzysztof Wilczyński was involved in analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising drafts. All the authors approved the final paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chaplin J. Pressure sore risk assessment in palliative care. J Tissue Viability. 2000;10:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0965-206x(00)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demarré L, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, et al. The cost of prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1754–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langemo D, Haesler E, Naylor W, Tippett A, Young T. Evidence-based guidelines for pressure ulcer management at the end of life. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21:225–232. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.5.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garber SL, Rintala DH. Pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: a retrospective study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:433–441. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.09.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petzold T, Eberlein-Gonska M, Schmitt J. Which factors predict incident pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients? A prospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1285–1290. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coomer NM, Kandilov AM. Impact of hospital-acquired conditions on financial liabilities for Medicare patients. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians Treatment of pressure ulcers: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:370–379. doi: 10.7326/M14-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chrisman CA. Care of chronic wounds in palliative care and end-of-life patients. Int Wound J. 2010;7:214–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khor HM, Tan J, Saedon NI, et al. Determinants of mortality among older adults with pressure ulcers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White-Chu EF, Reddy M. Pressure ulcer prevention in patients with advanced illness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7:111–115. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835bd622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez-Boussard TM, McDonald KM, Morrison DE, Rhoads KF. Risks of adverse events in colorectal patients: population-based study. J Surg Res. 2016;202:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schubert V. Hypotension as a risk factor for the development of pressure sores in elderly subjects. Age Ageing. 1991;20:255–261. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenwood C, McGinnis E. A retrospective analysis of the findings of pressure ulcer investigations in an acute trust in the UK. J Tissue Viability. 2016;25:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong M, Tuk B, Hekking IM, et al. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan mimetic improves pressure ulcer healing in a rat model of cutaneous ischemia-reperfusion injury. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cushing CA, Phillips LG. Evidence-based medicine: pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1720–1732. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a808ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang L, Dai Y, Cui F, et al. Expression of cytokines, growth factors and apoptosis-related signal molecules in chronic pressure ulcer wounds healing. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:145–151. doi: 10.1038/sc.2013.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn SD, Barrett RS, Fife CE, Thomson B. A predictive model for pressure ulcer outcome: the Wound Healing Index. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28:560–572. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000473131.10948.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padula WV, Mishra MK, Makic MB, Sullivan PW. Improving the quality of pressure ulcer care with prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care. 2011;49:385–392. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820292b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham B, Teague L, Mahoney J, et al. Early prevention of pressure ulcers among elderly patients admitted through emergency departments: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:468–478.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dealey C, Posnett J, Walker A. The cost of pressure ulcers in the United Kingdom. J Wound Care. 2012;21:261–262. 264, 266. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.6.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett RG, O’Sullivan J, DeVito EM, Remsburg R. The increasing medical malpractice risk related to pressure ulcers in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waterlow J. Pressure sores: a risk assessment card. Nurs Times. 1985;81:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoonhoven L, Haalboom JR, Bousema MT, et al. The prevention and pressure ulcer risk score evaluation study. Prospective cohort study of routine use of risk assessment scales for prediction of pressure ulcers. BMJ. 2002;325:797. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anthony D, Parboteeah S, Saleh M, Papanikolaou P. Norton, Waterlow and Braden scores: a review of the literature and a comparison between the scores and clinical judgement. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:646–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Pressure ulcers: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG179] [Accessed June 28, 2016]. Published: April 23, 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg179.

- 27.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Papacosta O, Whincup P. Mild hyponatremia, hypernatremia and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older men: a population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkhardt K, Kirchberger I, Heier M, et al. Hyponatraemia on admission to hospital is associated with increased long-term risk of mortality in survivors of myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1419–1426. doi: 10.1177/2047487314557963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holland-Bill L, Christiansen CF, Heide-Jørgensen U, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality risk: a Danish cohort study of 279 508 acutely hospitalized patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:71–81. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tachi T, Yokoi T, Goto C, et al. Hyponatremia and hypokalemia as risk factors for falls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:205–210. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drake-Holland AJ, Noble MI. The hyponatremia epidemic: a frontier too far? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:35. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2016.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGreal K, Budhiraja P, Jain N, Yu AS. Current challenges in the evaluation and management of hyponatremia. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2016;2:56–63. doi: 10.1159/000446267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weismann D, Schneider A, Höybye C. Clinical aspects of symptomatic hyponatremia. Endocr Connect. 2016 Sep 8; doi: 10.1530/EC-16-0046. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon J, Ahn SH, Lee YJ, Kim CM. Hyponatremia as an independent prognostic factor in patients with terminal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1735–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair S, Mary TR, Tarey SD, Daniel SP, Austine J. Prevalence of hyponatremia in palliative care patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:33–37. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.173954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liamis G, Milionis H, Elisaf M. A review of drug-induced hyponatremia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:144–153. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]