Abstract

This study investigated the effects of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, on T lymphocyte subsets in 16 healthy subjects. Lymphocyte subset proportions and absolute numbers were determined at baseline and on Day 10, after once-daily administration of ponesimod (10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg each consecutively for 3 days) or placebo (ratio 3:1). The overall change from baseline in lymphocyte count was −1,292±340×106 cells/L and 275±486×106 cells/L in ponesimod- and placebo-treated subjects, respectively. This included a decrease in both T and B lymphocytes following ponesimod treatment. A decrease in naïve CD4+ T cells (CD45RA+CCR7+) from baseline was observed only after ponesimod treatment (−113±98×106 cells/L, placebo: 0±18×106 cells/L). The number of T-cytotoxic (CD3+CD8+) and T-helper (CD3+CD4+) cells was significantly altered following ponesimod treatment compared with placebo. Furthermore, ponesimod treatment resulted in marked decreases in CD4+ T-central memory (CD45RA−CCR7+) cells (−437±164×106 cells/L) and CD4+ T-effector memory (CD45RA−CCR7−) cells (−131±57×106 cells/L). In addition, ponesimod treatment led to a decrease of −228±90×106 cells/L of gut-homing T cells (CLA−integrin β7+). In contrast, when compared with placebo, CD8+ T-effector memory and natural killer (NK) cells were not significantly reduced following multiple-dose administration of ponesimod. In summary, ponesimod treatment led to a marked reduction in overall T and B cells. Further investigations revealed that the number of CD4+ cells was dramatically reduced, whereas CD8+ and NK cells were less affected, allowing the body to preserve critical viral-clearing functions.

Keywords: ponesimod, multiple dose, S1P1 receptor, lymphocyte subsets, CD45RA/CCR7

Introduction

The adaptive immune system is responsible for maintaining immune competence, and it relies on the constant circulation of lymphocytes between lymphoid organs and other tissues in the body. In order to fulfill their function as surveyors of cognate antigen, mature lymphocytes leave the thymus and bone marrow to enter the circulation and lymphatic system and reach secondary lymphoid organs.1 Lysophospholipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), via the S1P1 receptor, has been shown to play a central role in the transit or egress of T lymphocytes out of the thymus as well as their movement between blood, lymphatics, and non-lymphoid tissues.2–5 S1P1 receptor modulators bind to the receptor resulting in its internalization, degradation, and down-regulation (ie, functional antagonism). In this way, lymphocytes cannot respond to the S1P signal in the blood and remain in the secondary lymphoid system and the thymus.6 This mechanism was foreseen as a possible therapeutic strategy in order to divert lymphocytes from sites of inflammation. Lymphocytes return to the blood and lymphatic circulation from their sites of sequestration following withdrawal of an S1P1 receptor modulator.3 On this basis, selective (eg, ponesimod) and non-selective (eg, fingolimod [Gilenya®]) S1P1 receptor modulators have been developed for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS).7–9 These immunomodulators affect different subpopulations of lymphocytes.10,11 In this study, we have extended the investigation of the lymphocyte subsets to include T-central memory (TCM) and T-effector memory (TEM) subpopulations. These subpopulations are defined by the expression of surface markers CD45RA and CCR7.12 As TCM and TEM cells and their CD4+ (helper T cells) and CD8+ (cytotoxic T cells) subtypes are thought to play distinct roles in immunopathology and protection against viral infections, the effects of multiple-dose treatment with ponesimod on these T cell subsets could elucidate the therapeutic mechanisms associated with selective S1P1 receptor modulation.

Methods

Subjects and study design

The details (ie, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design, and demographics) of this double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, randomized, up-titration study have been previously described.13 Briefly, 16 subjects received either ponesimod or placebo (ratio 3:1) with an up-titration scheme from 10 mg to 100 mg. The up-titration scheme was used since in previous studies this was found to diminish the effects on heart rate observed with administration of ponesimod.14,15

Subjects were administered the following ascending doses of ponesimod/placebo for 3 days each: 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg, 80 mg, and 100 mg. The study drug was administered once daily (o.d.) in the morning (fasted conditions) for a total of 18 days. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Flow cytometry analysis

On Day 1 pre-dose (baseline) and on Day 10 (prior to the first administration of 60 mg ponesimod), 1.5 mL of blood was collected into ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes and analyzed within 24 hours for lymphocyte subsets using four-color flow cytometry. The number of circulating T lymphocytes (CD3+), helper T cells (CD3+CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD3+CD8+), TCM cells (CD45RA−CCR7+), TEM cells (CD45RA−CCR7−), effector T cells (CD45RA+CCR7−), natural killer (NK) cells (CD3−CD56+), natural killer T (NKT) cells (CD3+CD56+), regulatory T cells (CD25+FoxP3+), and B cells (CD19+) was determined using flow cytometry. Monoclonal antibodies for specific cell markers were conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), allophycocyanin (APC), or peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP). More specifically, CD3–APC/CD4–PE/CD45RA–FITC/CCR7–phycoerythrin-cyanine dye (PECy7) antibodies were used to determine percent (%) of CD3+CD4+CD45RA±CCR7± cells, CD3–APC/CD8–PE/CD45RA–FITC/CCR7–PECy7 to determine % of CD3+CD8+CD45RA±CCR7± cells, CD45–PE/CD3–APC/CD19–FITC to determine % of CD3+ and CD3−CD19+ cells, CD45–PE/CD3–APC/CD56–AlexaFluor488 to determine % of CD3±CD56+ cells, CD4–FITC/CD25–PE/Foxp3–APC to determine % of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells, and CD3–APC/CD4–PECy7/CLA–FITC integrin to determine % of gut-homing T cells (CLA−integrin β7+) and skin-homing T cells (CLA+integrin β7−). Antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA), eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA), and Insight Biotechnology (Middlesex, UK). Cells were analyzed using the Dako Cyan flow cytometer and Summit software. The instrument was calibrated using FluoroSpheres calibration beads (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), and set-up tubes incorporating each individual antibody and unstained cells were run before each set of samples was analyzed in order to eliminate spectral overlap. The gating was determined using distinct forward and side scatter properties of the lymphocyte population. Furthermore, the gating was confirmed by staining with a lymphocyte-specific antibody CD3. The isotype controls for antibody staining were analyzed during the assay validation procedure.

Statistical methods

Absolute count (expressed as number of cells/L) and percentage change from baseline in lymphocyte count are presented as mean (±standard deviation [SD]). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Lymphocyte counts were compared by treatment group using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by Wandsworth Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Effects on T and B lymphocytes

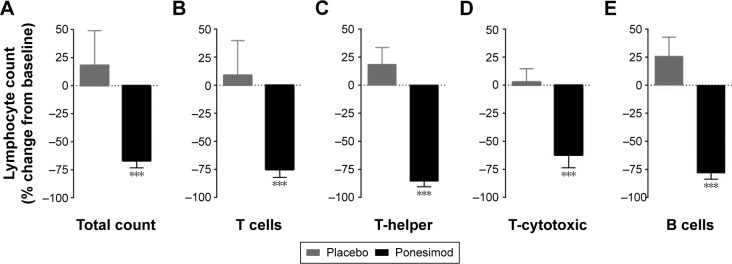

The overall mean lymphocyte count showed a marked decrease from baseline in ponesimod-treated subjects.13 At baseline, the mean (±SD) lymphocyte count was 1,908±387×106 cells/L and 1,825±287×106 cells/L in the ponesimod and placebo groups, respectively. On Day 10 before administration of the first dose of 60 mg ponesimod, the mean total lymphocyte count was 617±112×106 cells/L in ponesimod-treated subjects (P<0.001 vs baseline), whereas an increase was observed in placebo-treated subjects to reach 2,100±258×106 cells/L (P>0.05 vs baseline; P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod on Day 10). The percentage change from baseline is depicted in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Effect of placebo and ponesimod on total T and B cells count.

Notes: Reduction of (A) total lymphocytes, (B) CD3+ T cells, (C) CD4+ T-helper cells, (D) CD8+ T-cytotoxic cells, and (E) CD3−CD19+ B cells. Histograms represent the mean and SD of the percentage change from baseline (ie, Day 1 pre-dose) after 9 days of treatment with either placebo (gray bars) or ponesimod (black bars). Significance code: ***P<0.001 Student’s t-test placebo vs ponesimod.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

A minimum mean lymphocyte count of 400×106 cells/L was reached on Day 10, 4 hours after the subjects received their first daily dose of 60 mg ponesimod.13 The mean count did not decrease further during the study with up-titration of the ponesimod dose to 80 mg and 100 mg daily. Importantly, the mean lymphocyte count was quickly reversible upon discontinuation of ponesimod; by Day 29 (10 days after discontinuation of treatment), the mean lymphocyte count was 1,600±228×106 cells/L compared to a mean baseline count of 1,908±387×106 cells/L.

Both T (CD3+) and B (CD3−CD19+) lymphocytes were affected by ponesimod treatment. The flow cytometry analysis results of the T and B cell subsets from a representative ponesimod-treated subject are shown in Figure S1.

In placebo-treated subjects, an increase in the mean count of T cells was observed (from 1,273±269×106 cells/L to 1,507±139×106 cells/L), whereas a significant decrease (from 1,399±311×106 cells/L to 334±86×106 cells/L; P<0.001; Figure 1B) was detected in ponesimod-treated subjects. Whereas the mean count of B cells (CD3−CD19+) slightly increased in the placebo group between Day 1 (186±49×106 cells/L) and Day 10 (234±65×106 cells/L), a significant decrease was observed in ponesimod-treated subjects (from 215±63×106 cells/L to 46±18×106 cells/L; P<0.001; Figure 1E).

The analysis of the T cell subsets in ponesimod-treated subjects showed marked decreases in the mean count of helper (CD3+CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD3+CD8+) T cells. Helper and cytotoxic T cells increased from 687±110×106 cells/L to 848±46×106 cells/L and from 476±167×106 cells/L to 554±135×106 cells/L, respectively, in the placebo group. In the ponesimod group, a significant decrease from 801±222×106 cells/L to 115±47×106 cells/L (P<0.001 Day 10 vs baseline; P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod) and from 484±117×106 cells/L to 172±45×106 cells/L (P<0.001 Day 10 vs baseline; P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod) was observed for helper (CD3+CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD3+CD8+) T cells, respectively. Percentage change from baseline is represented in Figure 1C and D.

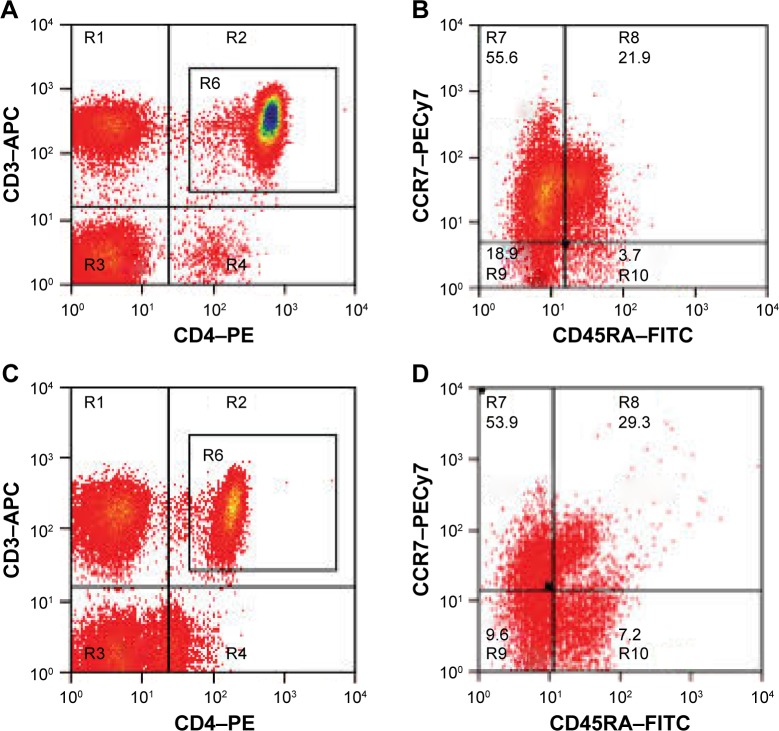

The effects of ponesimod on the subpopulations of CD4+

T-helper cells were further analyzed by using CD45RA and CCR7 surface markers. The flow cytometry analysis of a representative ponesimod-treated subject is shown in Figure 2. The initial lymphocyte gate (graph not shown) was followed by gating on CD3+CD4+ T cells (Figure 2A and C, gate R6). The gated CD3+CD4+ T cells were further analyzed for the expression of CD45RA (x axis) and CCR7 (y axis), as shown in Figure 2B and D. The relative decrease in the proportion of TEM cells (CD45RA−CCR7−) was prominent on flow cytometry graphs (Figure 2B and D), ie, from 18.9% at baseline to 9.6% on Day 10. In contrast, effector T cells (CD45RA+CCR7−) showed a relative proportional increase on Day 10 (7.2%) when compared to baseline (3.7%) (Figure 2B and D).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD3+CD4+ helper T cells expressing CD45RA and CCR7.

Notes: (A) The CD3+CD4+ T cells at baseline (Day 1) are gated (R6) and further analyzed for the expression of (B) CD45RA and CCR7 (R8 and R10). The same subject is analyzed after ponesimod treatment on Day 10. (C) The CD3+CD4+ T cells are gated (R6) and further analyzed for the expression of (D) CD45RA and CCR7. The relative decrease of T effector memory cells (percentage of CD45RA−/CCR7− cells counted in gate R6) is shown in the lower left quadrant (9.6% on Day 10 vs 18.9% at Day 1 baseline). In contrast, effector T cells (percentage of CD45RA+CCR7− cells counted in gate R6), lower right quadrant, show a relative increase on Day 10 (7.2% vs 3.7% at baseline). The increased number of cells in dot plots is reflected in the change in color from red to yellow, followed by green and blue for the highest number of cells.

Abbreviations: APC, allophycocyanin; PE, phycoerythrin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

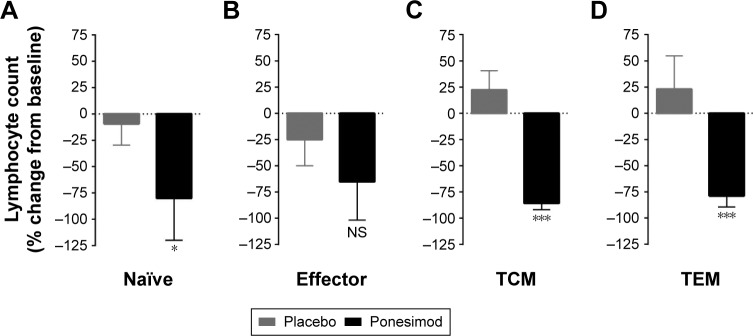

The relative changes in the proportion of T cell subsets were used to calculate absolute cell numbers based on the measurements of lymphocyte counts and appropriate flow cytometry gating. As shown in Figure 3A, the mean number of naïve CD4+ T cells (CD45RA+CCR7+) remained stable following placebo administration but fell sharply (from 143±121×106 cells/L to 12±12×106 cells/L; P<0.05 vs baseline; P<0.05 placebo vs ponesimod) after o.d. administration of ponesimod for 10 days. No significant change in the absolute number of effector CD4+ T cells was observed. This corresponds to the changes in relative proportion of these cells in flow cytometry graphs (Figure 2B and D); however, this might be related to the high variability observed at baseline in the ponesimod group. Mean percentage change from baseline revealed a slight difference between both groups (P>0.05; Figure 3B). In the placebo group, CD4+ TCM (CD45RA−CCR7+) and CD4+ TEM cells remained stable between Day 1 (TCM: 463±60×106 cells/L; TEM: 118±57×106 cells/L) and Day 10 (TCM: 596±147×106 cells/L; TEM: 119±48×106 cells/L). Following treatment with ponesimod, CD4+ TCM and TEM cells significantly fell from 492±175×106 cells/L to 70±34×106 cells/L (P<0.001 Day 1 vs Day 10 and P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod) and from 157±57×106 cells/L to 31±16×106 cells/L (P<0.001 Day 1 vs Day 10 and P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod), respectively (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Effect of placebo and ponesimod on CD4+ T cell subsets.

Notes: Percentage change from baseline (Day 1 pre-dose) in (A) peripheral blood naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+), (B) effector (CD45RA+CCR7−), (C) TCM (CD45RA−CCR7+), and (D) TEM (CD45RA−CCR7−) CD4+ T cells on Day 10 post-dose with placebo or ponesimod. Data are presented as mean with SD. Significance code: *P<0.05, ***P<0.001; t-test placebo vs ponesimod.

Abbreviations: TCM, T-central memory; TEM, T-effector memory; SD, standard deviation; NS, not significant.

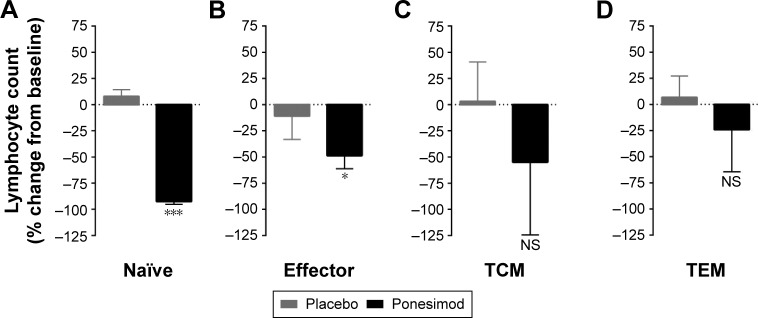

Effects on CD8+ T cell subpopulations

The cytotoxic CD8+ T cell subpopulations were also further analyzed using surface expression of CD45RA and CCR7 markers. A similar baseline for the placebo (190±92×106 cells/L) and ponesimod (188±99×106 cells/L) groups was observed for the mean number of circulating naïve CD8+ cells. A slight increase was observed in the placebo group on Day 10 (235±78×106 cells/L), whereas a significant decrease was observed (12±5×106 cells/L on Day 10; P<0.0001; Figure 4A) in the ponesimod group. Despite a small decrease in the number of CD8+ effector T cells in the placebo group (from 64±27×106 cells/L to 50±17×106 cells/L), a significant drop was observed in ponesimod-treated subjects (from 113±69×106 cells/L to 54±24×106 cells/L; P<0.05; Figure 4B). Ponesimod led to a significant decrease in CD8+ TCM cells count (Day 1: 32±17×106 cells/L, Day 10: 8±4×106 cells/L; P<0.01), whereas this count was not affected by placebo treatment (Day 1: 50±25×106 cells/L, Day 10: 63±29×106 cells/L; P<0.001 placebo vs ponesimod). Interestingly, no significant differences were observed when analyzing the percentage change from baseline in TCM cells between the treatments (Figure 4C). Similarly, although a trend was observed, the change in the number of CD8+ TEM cells was not significantly different between placebo- (from 172±94×106 cells/L to 205±74×106 cells/L) and ponesimod-treated subjects (from 151±68×106 cells/L to 98±43×106 cells/L; Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of placebo and ponesimod on CD8+ T cell subsets.

Notes: Percentage change from baseline (Day 1 pre-dose) in (A) peripheral blood naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+), (B) effector (CD45RA+CCR7−), (C) TCM (CD45RA−CCR7+), and (D) TEM (CD45RA−CCR7−) CD8+ T cells on Day 10 post-dose with placebo or ponesimod. Data are presented as mean with SD. Significance code: *P<0.05, ***P<0.001; t-test placebo vs ponesimod.

Abbreviations: TCM, T-central memory; TEM, T-effector memory; SD, standard deviation; NS, not significant.

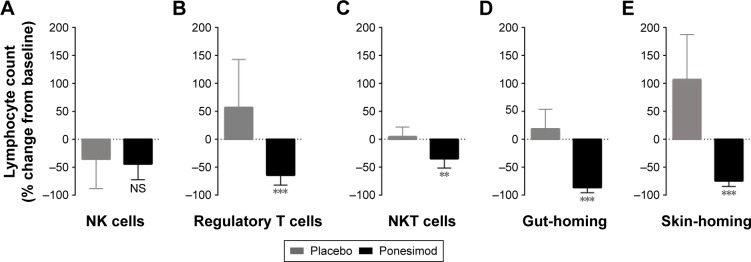

Effects on NK cells

The absolute number of NK cells (CD3−CD56+) was higher at baseline (211±109×106 cells/L and 268±65×106 cells/L in the placebo and ponesimod groups, respectively) than after placebo (142±81×106 cells/L; P>0.05) or ponesimod (100±35×106 cells/L; P<0.05) dosing. Comparison of percentage change from baseline revealed a similar decrease in placebo- (−44%±28%) and ponesimod-treated subjects (−36%±53%; P>0.05 placebo vs ponesimod; Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of placebo and ponesimod on NK cells, regulatory T cells, NKT cells, gut-homing T cells, and skin-homing T cells.

Notes: Percentage change from baseline (Day 1 pre-dose) in (A) peripheral NK cells (CD3−CD56+), (B) regulatory T cells (CD25+Foxp3+), (C) NKT cells (CD3+CD56+), (D) gut-homing (CLA−integrin β7+), and (E) skin-homing (CLA+integrin β7−) T cells on Day 10 post-dose with placebo or ponesimod. Data are presented as mean with SD. Significance code: **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; t-test placebo vs ponesimod.

Abbreviations: NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T memory; SD, standard deviation; NS, not significant.

Effects on regulatory T cells, NKT cells, gut-homing T cells, and skin-homing T cells

The number of regulatory T cells (CD25+Foxp3+) increased from 15±9×106 cells/L to 23±20×106 cells/L following treatment with placebo but decreased (from 12±6×106 cells/L to 5±3×106 cells/L; P>0.05 baseline vs Day 10) following o.d. administration of ponesimod for 10 days. A significant difference between placebo and ponesimod treatment on Day 10 was observed (P<0.001; Figure 5B), although a large variability was observed in both groups.

Although analysis of the absolute number of NKT cells (CD3+CD56+) revealed that neither placebo nor ponesimod affected NKT cells count (P>0.05, baseline vs Day 10 for both), comparison of percentage change from baseline revealed a statistically significant difference between placebo and ponesimod treatment (P<0.001; Figure 5C).

Mean count of gut-homing T cells (CLA−integrin β7+) was significantly decreased after 10 days of ponesimod treatment (from 258±80×106 cells/L to 32±17×106 cells/L; P<0.001), whereas there was no placebo effect (from 267±114×106 cells/L to 364±186×106 cells/L; P>0.05). On Day 10, the number of gut-homing T cells was significantly lower in ponesimod- when compared to placebo-treated subjects (P<0.001; Figure 5D). The number of skin-homing T cells (CLA+integrin β7−) increased following placebo (from 26±22×106 cells/L to 36±39×106 cells/L) but markedly decreased after treatment with ponesimod (from 33±15×106 cells/L to 7±3×106 cells/L; P<0.01). Using percentage change from baseline, the change from baseline was significantly different between placebo and ponesimod treatment (P<0.001; Figure 5E).

Discussion

In this study, the effects of multiple-dose administration of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, on lymphocyte subsets were investigated. In a previous study, we showed that single-dose administration of ponesimod leads to a higher reduction of naïve T cells and CD4+ T cells compared to memory T cells and CD8+ T cells.10 The pharmacokinetics and safety and tolerability of the up-titration regimen employed in this study have been published previously13 and revealed that on Day 10, when blood was sampled to further decipher the effects on lymphocyte subpopulations, the concentration of ponesimod in plasma was virtually at steady state.

The homeostasis of the immune system and outcome of inflammatory reactions depend on the compartmentalization of lymphocyte subsets and their ability to differentiate into pro-inflammatory and regulatory cells. The action of S1P1 receptor modulators impedes the homing of these cells to sites of inflammation and alters the delicate balance between lymphocyte retention and egress.

In this study, retention of CD4+ cells was more prominent compared to CD8+ cells. This is in agreement with previous studies with single-dose administration of ponesimod10 and fingolimod.16 This might be related to the recruitment and priming of CD8+ cells that may occur in non-lymphoid organs.17

In addition to their immunological properties (eg, homing capacity or effector function), memory T cells can be differentiated using the expression of two markers: CD45RA and CCR7.12 It has been shown that the expression of these markers and the number of cells in each phenotype remain fairly stable in the same individual but phenotypic distribution varies considerably between individuals.18 This variation is most notable in the CD8+ lymphocyte subsets and could help to explain the large variation in the expression of these markers observed in the placebo group.

It is known that chemokine receptor CCR7 is necessary for lymph node homing leading to the retention of CCR7+ cells (TCM and naïve cells) in secondary lymphoid organs.17 TEM cells that do not express CCR7 are thought to migrate directly into target tissues where they can act as effector immune cells. In addition, an increase in the S1P1 receptor expression could influence the conversion of naïve T cells into effector and effector memory cells (CD45RA−) by down-regulation of CCR7.4 In addition, S1P1 receptor expression is high in naïve T cells and low in effector and memory cells.19 Taken together, this fully supports the present data and is in agreement with previous studies with fingolimod16 in which naïve T cells and TCM cells are more affected by selective and non-selective S1P receptor modulators compared to TEM cells and effector T cells that both continue to reside outside secondary lymphoid tissues. Although ponesimod effects on T cell subpopulations reported in this study follow these general principles, as illustrated by the selective sparing of the CD8+ TEM cells, it is important to note that ponesimod treatment results in a distinct, significant decrease in CD4+ TEM cells. This differential effect on CD4+ TEM challenges the assumption that CD4+ and CD8+ TEM cells share similar migration mechanisms. Indeed, a recent study on the distribution of the human T cell subpopulations has reported that CD4+ TEM cells are primarily resting and compartmentalized, whereas CD8+ TEM cells show increased circulation through tissues.20 Furthermore, the lack of CCR7 expression did not result in the exclusion of T cells from lymphoid organs, as 20%–50% of the total T cells found in human lymph nodes were CCR7− TEM cells. Thus, CD4+ TEM cells despite being CCR7− may enter the lymph nodes and their exit could be prevented by ponesimod. Indeed, a recent study in a mouse model has confirmed that the entry of CD4+ TEM cells into lymph nodes is independent of CCR7 expression.21 Therefore, ponesimod treatment could reduce the number of CD4+ TEM cells in the blood, as these cells appear to be able to enter lymph nodes despite the lack of CCR7 expression and may require S1P1 receptor signal to exit into the circulation.

Nevertheless, the mechanisms that could explain the lack of similar effects on CD4+ TEM cells by non-selective S1P receptor modulators such as fingolimod remain to be clarified. The differential effects between ponesimod and fingolimod are likely due to the binding of the latter to S1P3–5 receptors. As S1P4 is expressed on immune cells, it is feasible that fingolimod binding to S1P4 could modulate S1P1 signaling22 or may act indirectly by affecting T cell interaction with dendritic cells.23

Calculation of absolute numbers of T regulatory cells (CD25+Foxp3+) demonstrated a moderate non-significant decrease in the number of these cells circulating during ponesimod treatment. A study in chronic plaque psoriasis patients revealed that the effect of ponesimod on CD4+ T regulatory cells is low relative to the effect on conventional CD4+ T cells.9 Interestingly, a recent clinical study showed that MS patients have a decreased number of T regulatory cells and that fingolimod did not significantly change T regulatory cells count in MS patients.24 NKT cells (CD3+CD56+) do not require S1P1 receptor expression for development in the thymus, but the receptor is necessary for these cells to emerge into peripheral tissues. Once established, S1P1 receptor expression does not appear to alter the distribution of these cells.25 This observation is supported by data in a mouse model in which fingolimod did not alter the distribution of NKT cells within peripheral tissues.26 The absolute number of NKT cells on Day 10 was similar in the active and placebo groups, suggesting that these cells are largely unaffected by ponesimod. This could in part be due to the low rate of entry of NKT cells into lymph nodes due to their low expression of CCR7 and CD62L.25 Although NKT cells are a variable population with low numbers in peripheral blood, rendering their analysis difficult, the data in this study support previous observations in animal studies that absolute numbers or tissue distribution of NKT cells are largely unaffected by administration of an S1P1 receptor modulator.26

The effects of ponesimod on T cell subsets show considerable overlap with the effects of the non-selective S1P receptor modulator fingolimod. However, our data provide clear evidence that the effects of ponesimod on T cell subsets are complex with distinct effects on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that do not conform to the mode of action of fingolimod. Here, we report that in contrast to fingolimod,27 ponesimod treatment results in a significant reduction in CD4+ TEM cells. This effect could be important in MS and other autoimmune diseases, as CD4+ TEM cells potentially contribute to immunopathology.28,29

Supplementary material

Flow cytometry graphs showing reduction in the percentages of T and B cells after multiple-dose administration of ponesimod (Day 10).

Notes: (A) Baseline dot plot of whole blood stained with anti-CD45-PE, CD3-APC, and CD19-FITC. CD45+ lymphocytes were gated (R1) using a CD45-PE/SSC plot. (B) CD19-FITC/CD3-APC plot was generated when gated on R1. The percentage (%) of CD19+ B cells is shown in lower right quadrant and % CD3+ T cells in the upper left quadrant. (C) Day 10 dot plot of whole blood similarly stained. Flow cytometry profile shown is from a representative ponesimod-treated subject. (D) CD19-FITC/CD3-APC plot was generated when gated on R6.

Abbreviations: PE, phycoerythrin; APC, allophycocyanin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; SSC, side scatter; lin, linear; log, logarithmic.

Acknowledgments

Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd provided funding for this clinical trial.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Pierre-Eric Juif, Daniele D’Ambrosio, and Jasper Dingemanse are full time employees of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.von Andrian UH, Mackay CR. T-cell function and migration. Two sides of the same coin. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):1020–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkmann V. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in health and disease: mechanistic insights from gene deletion studies and reverse pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115(1):84–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Finding a way out: lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwab SR, Pereira JP, Matloubian M, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309(5741):1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1113640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiba K, Matsuyuki H, Maeda Y, Sugahara K. Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor type 1 in lymphocyte egress from secondary lymphoid tissues and thymus. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3(1):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun J, Brinkmann V. A mechanistically novel, first oral therapy for multiple sclerosis: the development of fingolimod (FTY720, Gilenya) Discov Med. 2011;12(64):213–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsson T, Boster A, Fernandez O, et al. Oral ponesimod in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised phase II trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(11):1198–1208. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaclavkova A, Chimenti S, Arenberger P, et al. Oral ponesimod in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2036–2045. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Ambrosio D, Steinmann J, Brossard P, Dingemanse J. Differential effects of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, on blood-circulating human T cell subpopulations. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2015;37(1):103–109. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2014.993084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song ZY, Yamasaki R, Kawano Y, et al. Peripheral blood T cell dynamics predict relapse in multiple sclerosis patients on fingolimod. PLoS One. 2014;10(4):e0124923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoch M, D’Ambrosio D, Wilbraham D, Brossard P, Dingemanse J. Clinical pharmacology of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, after uptitration to supratherapeutic doses in healthy subjects. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;63C:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brossard P, Scherz M, Halabi A, Maatouk H, Krause A, Dingemanse J. Multiple-dose tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of ponesimod, an S1P1 receptor modulator: favorable impact of dose up-titration. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(2):179–188. doi: 10.1002/jcph.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scherz MW, Brossard P, D’Ambrosio D, Ipek M, Dingemanse J. Three different up-titration regimens of ponesimod, an S1P1 receptor modulator, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(6):688–697. doi: 10.1002/jcph.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinkmann V, Billich A, Baumruker T, et al. Fingolimod (FTY720): discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(11):883–897. doi: 10.1038/nrd3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis M, Tarlton JF, Cose S. Memory versus naive T-cell migration. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86(3):226–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401(6754):708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garris CS, Blaho VA, Hla T, Han MH. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 signalling in T cells: trafficking and beyond. Immunology. 2014;142(3):347–353. doi: 10.1111/imm.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thome JJ, Yudanin N, Ohmura Y, et al. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell. 2014;159(4):814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vander Lugt B, Tubo NJ, Nizza ST, et al. CCR7 plays no appreciable role in trafficking of central memory CD4 T cells to lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2013;191(6):3119–3127. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sic H, Kraus H, Madl J, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors control B-cell migration through signaling components associated with primary immunodeficiencies, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple sclerosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(2):420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulze T, Golfier S, Tabeling C, et al. Sphingosine-1-phospate receptor 4 (S1P(4)) deficiency profoundly affects dendritic cell function and TH17-cell differentiation in a murine model. FASEB J. 2011;25(11):4024–4036. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venken K, Hellings N, Broekmans T, Hensen K, Rummens JL, Stinissen P. Natural naive CD4+CD25+CD127low regulatory T cell (Treg) development and function are disturbed in multiple sclerosis patients: recovery of memory Treg homeostasis during disease progression. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6411–6420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allende ML, Zhou D, Kalkofen DN, et al. S1P1 receptor expression regulates emergence of NKT cells in peripheral tissues. FASEB J. 2008;22(1):307–315. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9087com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang SJ, Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim S, Chung DH. FTY720, a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, inhibits CD1d-restricted NKT cells by suppressing cytokine production but not migration. Lab Invest. 2010;90(1):9–19. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishihara H, Shimizu F, Sano Y, et al. Fingolimod prevents blood-brain barrier disruption induced by the sera from patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamanaka M, Huber S, Zenewicz LA, et al. Memory/effector (CD45RB(lo)) CD4 T cells are controlled directly by IL-10 and cause IL-22-dependent intestinal pathology. J Exp Med. 2011;208(5):1027–1040. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaigirdar SA, MacLeod MK. Development and function of protective and pathologic memory CD4 T cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:456. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flow cytometry graphs showing reduction in the percentages of T and B cells after multiple-dose administration of ponesimod (Day 10).

Notes: (A) Baseline dot plot of whole blood stained with anti-CD45-PE, CD3-APC, and CD19-FITC. CD45+ lymphocytes were gated (R1) using a CD45-PE/SSC plot. (B) CD19-FITC/CD3-APC plot was generated when gated on R1. The percentage (%) of CD19+ B cells is shown in lower right quadrant and % CD3+ T cells in the upper left quadrant. (C) Day 10 dot plot of whole blood similarly stained. Flow cytometry profile shown is from a representative ponesimod-treated subject. (D) CD19-FITC/CD3-APC plot was generated when gated on R6.

Abbreviations: PE, phycoerythrin; APC, allophycocyanin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; SSC, side scatter; lin, linear; log, logarithmic.