Abstract

Comorbid obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and bipolar disorder (BD) have long been an intractable problem in clinical practice. The increased risk of manic/hypomanic switch hinders the use of antidepressants for managing coexisting OCD symptoms in BD patients. We herein present a case of a patient with BD–OCD comorbidity, who was successfully treated with mood stabilizers and aripiprazole augmentation. The young female patient reported recurrent depressive episodes and aggravating compulsive behaviors before hospitalization. Of note, the patient repetitively attempted suicide and reported dangerous driving because of intolerable mental sufferings. The preexisting depressive episode and OCD symptoms prompted the use of paroxetine, which consequently triggered the manic switching. Her diagnosis was revised into bipolar I disorder. Minimal response with mood stabilizers prompted the addition of aripiprazole (a daily dose of 10 mg), which helped to achieve significant remission in emotional and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. This case highlights the appealing efficacy of a small dose of aripiprazole augmentation for treating BD–OCD comorbidity. Well-designed clinical trials are warranted to verify the current findings.

Keywords: aripiprazole, bipolar disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, suicide

Introduction

Although the phenomenology of coexisting obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and bipolar disorder (BD) has been identified for more than 100 years,1 the etiological and nosological aspects of this medical issue remain largely unknown. Symptoms of OCD may occur before, during, or after the first mood episode and, in most cases, fluctuate with mood swings.2 In this regard, the majority of BD–OCD comorbidities are considered to be a subtype of BD, rather than two separate diseases.3

To date, no standard pharmacotherapy for cooccurring BD–OCD has been established. Antidepressants, especially for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are first-line options for OCD treatment, are strictly restricted for BD–OCD individuals because of the potential to elicit manic/hypomanic switching.4 In majority of the cases, a combination of multiple mood stabilizers or augmentative antipsychotics to mood stabilizers constitute the routine medication regimens.5 However, due to the lack of well-designed clinical trials, case reports of successful treatment in patients with comorbid BD–OCD are of important reference value for clinical practice.

We herein present a case of a young female patient who suffered from recurrent mood episodes and symptoms of OCD. This patient reported repetitive suicidal ideations and behaviors. A combination of quetiapine and valproate stabilized her mood; however, it did not lead to apparent improvement of her OCD symptoms. Therefore, a small dose of aripiprazole was added to the mood stabilizers, which consequently achieved significant remission in her obsessive–compulsive symptoms. This case report favors the use of augmentative aripiprazole in patients with comorbid BD–OCD who respond poorly to mood stabilizers.

Case presentation

Very briefly, we would like to introduce our case report as follows. Mrs A, a 28-year-old woman, was admitted to the Department of Psychiatry in our hospital because of recurrent depressive episodes and aggravating compulsive behaviors. Two years prior to admission, this patient developed her first depressive episode after breaking up with her ex-boyfriend. Thereafter, this patient became depressed and had insomnia, loss of appetite, and loss of interest. Meanwhile, she began to repetitively tidy up her belongings and check whether the windows and doors were closed. There was no suicidal ideation reported at that moment and she could still adhere to the work as a bank staff. However, pressure at work made her situation worse. Her obsessive behaviors gradually aggravated, with repetition rate remarkably increasing from several times per day to dozens of times per day. The obsessive behaviors always worsen when her mood became labile. This patient became easily upset and agitated when being persuaded by her family members. About half a year prior to admission, this patient reported the first suicidal attempt after fighting with her parents. She went into emotional outburst, stood at the window, and claimed to end her own life. Her parents even kneeled on the floor to take her out of committing suicide. Since then, she had reported repetitive suicidal attempts. She would rush to the balcony or windows and would attempt to commit suicide by jumping down from the building, while she was also reported with dangerous driving behaviors. Consequently, her daily life and job were seriously disrupted.

The patient was then sent to our hospital by her parents. A primary diagnosis of OCD was made, and paroxetine was prescribed at a daily dose of 40 mg. About a week later, the patient became extremely excited, talkative, and vigorous. Although paroxetine was discontinued soon afterward and quetiapine was initiated, her manic state lasted for nearly 3 weeks. Therefore, hospitalization was suggested by her doctor.

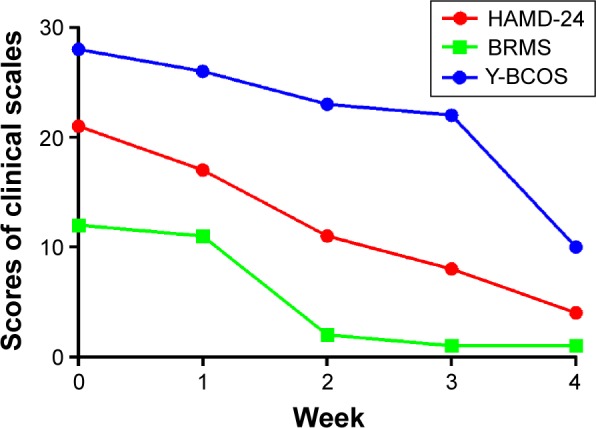

After admission, a comprehensive physical and laboratory examinations were performed to exclude unknown underlying physical diseases. Besides, cranial magnetic resonance imaging scan was also normal. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, this patient was dually diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and OCD. Quetiapine was gradually titrated up to 700 mg per day with concomitant valproate at 1,000 mg per day. Although her emotion became stable with these mood stabilizers, the patient reported an inadequate response in symptoms of OCD. A small dose of atypical antipsychotics was considered to enhance the treatment efficacy. Fascinatingly, an add-on therapy of aripiprazole 10 mg per day promoted accelerating alleviation of her obsessive behaviors. Meanwhile, no severe adverse events were observed. Her remission in emotional and OCD symptoms was well maintained in the follow-up visits. No suicidal attempt was reported after hospital discharge. A detailed rating of clinical scales is recorded in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Detailed record of the scores of clinical scales during in-patient treatment.

Notes: As quetiapine was already initiated before hospitalization, it was continued at a dose of 400 mg/day after admission and gradually titrated up to 700 mg/d in 2 weeks. Valproate was initiated in the second week and titrated up to 1,000 mg/d in 1 week. Aripiprazole was added 3 weeks after admission at an initial dose of 5 mg/d and increased to 10 mg/d 3 days later.

Abbreviations: HAMD-24, Hamilton depression rating scale (24 items); BRMS, Beth–Rafaelsen mania scale; Y-BOCS, Yale–Brown obsessive–compulsive scale.

This work was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her guardians.

Discussion

The condition of BD–OCD comorbidity has always been common in clinical practice. However, “spurious” OCD comorbidity in BD should be carefully differentiated from the “true” comorbidity. In most cases of comorbid subjects, the OCD symptoms appear to be closely linked to affective symptoms, manifesting dominantly an episodic and mood-dependent course.6 In other words, the OCD symptoms in these individuals were part of BD rather than a separate disease. To date, the optimal treatment protocols for BD–OCD comorbidity were not sufficiently elucidated. Our study indicates that low-dose augmentation with aripiprazole may help to relieve the accompanying symptoms of OCD in BD patients. Although a combination of mood stabilizers effectively alleviated the emotional symptoms, additional aripiprazole may be necessary to address the remaining symptoms of OCD. To our knowledge, the dose of aripiprazole (10 mg per day) in our patient was lower than other documented cases (15–25 mg per day).7,8 Moreover, no published literature has ever discussed the impact of augmentative medications on suicidal risk in BD–OCD patients.

Aripiprazole, an atypical antipsychotic, acts as a partial agonist at the D2 and 5-HT1A receptors, as well as an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptor.9 Aripiprazole monotherapy, or as an adjuvant to mood stabilizers, is efficacious in managing acute mania and stabilization phases of BD, but not bipolar depression.10 Besides, recent evidence favors the use of augmentative aripiprazole for SSRIs-refractory OCD.11,12 However, long-term use of aripiprazole is associated with increased risk of extrapyramidal syndromes (EPSs).10 Therefore, defining the minimum effective dose of aripiprazole is essential for preventing EPSs. In our patient, a low-dose of aripiprazole augmentation exhibited remarkable anti-OCD effect. Of note, the add-on therapy to mood stabilizers was initiated after partial remission in emotional symptoms. The aforementioned information implies a promising two-step strategy for BD–OCD treatment. That is, first to attenuate the mood problem with mood stabilizers and then, if necessary, deal with the obsessive behaviors with an adjuvant, such as the employment of aripiprazole indicated in our study. This two-step strategy not only helps avoid the unnecessary add-on medications if adequate response was observed with mood stabilizers but also facilitates the determination of minimum effective dose of the adjuvant.

The suicidal risk in BD–OCD patients has not been fully elucidated, as well as drug-induced suicidal ideations. Patients with BD–OCD comorbidity reported more suicidal attempts than those without morbidity.13 Several antipsychotics, including risperidone,14 olanzapine,15 quetiapine,16 and aripiprazole,7,8 were suggested due to the benefits in relieving the OCD symptoms in BD patients. However, in these studies, little attention has been paid to the emergent suicidal ideations following the antipsychotic augmentation. A few case reports documented the possible link of using aripiprazole with suicidal ideation.17 However, epidemiological data in large sample revealed that consuming aripiprazole was not associated with more suicide events compared to other atypical antipsychotics.18 Moreover, aripiprazole users had reported significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality among various antipsychotics.19 Given the recurrent onset of suicidal attempts in our patient, special attention should be paid to the suicidal profiles of antipsychotic augmentation in BD–OCD patients.

To conclude, the present case study provides supporting evidence that aripiprazole augmentation to mood stabilizers was efficacious in patients with BD–OCD comorbidity. A brief two-step strategy for managing BD–OCD comorbidity was raised. Besides, paying special attention to suicidal risk surround antipsychotic augmentation was also suggested. In the future, well-designed studies are warranted to verify our findings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of National Clinical Research Center for Mental Health Disorders (2015BAI1-3B02). The authors appreciate the patient and her guardians for their understanding.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Morel BA. Traité des maladies mentales. 2nd ed. Paris, France: Masson; 1860. French. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonna M, Amerio A, Odone A, et al. Comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: which came first? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(7):695–698. doi: 10.1177/0004867415621395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amerio A, Tonna M, Odone A, Ghaemi SN. Comorbid Bipolar Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Old Debate Renewed. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(3):370–371. doi: 10.4306/pi.2016.13.3.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perugi G, Toni C, Frare F, Travierso MC, Hantouche E, Akiskal HS. Obsessive-compulsive-bipolar comorbidity: a systematic exploration of clinical features and treatment outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1129–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amerio A, Odone A, Marchesi C, Ghaemi SN. Treatment of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2014;166:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amerio A, Odone A, Liapis CC, Ghaemi SN. Diagnostic validity of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(5):343–358. doi: 10.1111/acps.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uguz F. Successful treatment of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder with aripiprazole in three patients with bipolar disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):556–558. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patra S. Treat the disease not the symptoms: successful management of obsessive compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder with aripiprazole augmentation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(8):809–810. doi: 10.1177/0004867416656262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies MA, Sheffler DJ, Roth BL. Aripiprazole: a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a uniquely robust pharmacology. CNS Drug Rev. 2004;10(4):317–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meduri M, Gregoraci G, Baglivo V, Balestrieri M, Isola M, Brambilla P. A meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in adult and pediatric bipolar disorder in randomized controlled trials and observational studies. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:187–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayyah M, Sayyah M, Boostani H, Ghaffari SM, Hoseini A. Effects of aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (a double blind clinical trial) Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):850–854. doi: 10.1002/da.21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: an update meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(9) doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv047. pii: pyv047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozdemiroglu F, Sevincok L, Sen G, et al. Comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder with bipolar disorder: a distinct form? Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(3):800–805. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raja M, Azzoni A. Clinical management of obsessive-compulsive-bipolar comorbidity: a case series. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(3):264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrikis P, Andreou C, Bozikas VP, Karavatos A. Effective use of olanzapine for obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a patient with bipolar disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(8):572–573. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratta P, de Cataldo S, Mancini G, Gianfelice D, Rinaldi O, Rossi A. Quetiapine as adjunctive treatment of a case of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder with comorbidity. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(7):559–560. doi: 10.1002/hup.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selvaraj V, Ramaswamy S, Sharma A, Wilson D. New-onset psychosis and emergence of suicidal ideation with aripiprazole. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1535–1536. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulcickas Yood M, Delorenze G, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Epidemiologic study of aripiprazole use and the incidence of suicide events. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(11):1124–1130. doi: 10.1002/pds.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ringbäck Weitoft G, Berglund M, Lindström EA, Nilsson M, Salmi P, Rosén M. Mortality, attempted suicide, re-hospitalisation and prescription refill for clozapine and other antipsychotics in Sweden-a register-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(3):290–298. doi: 10.1002/pds.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]