Abstract

Effectively utilizing incomplete multi-modality data for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is still an area of active research. Several multi-view learning methods have recently been developed to deal with missing data, with each view corresponding to a specific modality or a combination of several modalities. However, existing methods usually ignore the underlying coherence among views, which may lead to suboptimal learning performance. In this paper, we propose a view-aligned hypergraph learning (VAHL) method to explicitly model the coherence among the views. Specifically, we first divide the original data into several views based on possible combinations of modalities, followed by a sparse representation based hypergraph construction process in each view. A view-aligned hypergraph classification (VAHC) model is then proposed, by using a view-aligned regularizer to model the view coherence. We further assemble the class probability scores generated from VAHC via a multi-view label fusion method to make a final classification decision. We evaluate our method on the baseline ADNI-1 database having 807 subjects and three modalities (i.e., MRI, PET, and CSF). Our method achieves at least a 4.6% improvement in classification accuracy compared with state-of-the-art methods for AD/MCI diagnosis.

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that continues to pose major challenges to global health care systems [1]. Studies have shown that multi-modality data (e.g., structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)) provide complementary information that can be harnessed for improving diagnosis of AD and its prodrome, known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [2–5]. However, collecting data with multi-modalities is challenging and the data are often incomplete due to patient dropouts. In the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database, for instance, while baseline MRI data were collected for all subjects, only approximately half of the subjects have baseline PET data and half of the subjects have baseline CSF data.

Various approaches have been developed to deal with the problem of incomplete multi-modality data. A straightforward method is to remove subjects with missing data. This approach, however, significantly reduces the sample size. An alternative way is to impute the missing data using techniques such as expectation maximization (EM) [6], singular value decomposition (SVD) [7], and matrix completion [5]. However, the effectiveness of this method can be affected by imputation artifacts. Several recently introduced multi-view learning based methods circumvent the need for imputation [3,4]. These methods generally apply specific learning algorithms to different views of the data, comprising the combinations of available data from different modalities. However, the coherence among views is not explicitly considered in these methods. Intuitively, integrating these views coherently can lead to better diagnostic performance. On the other hand, hypergraph learning [8] has attracted increasing attention in neuroimaging analysis, where complex relationships among vertices can be modeled via hyperedges [9].

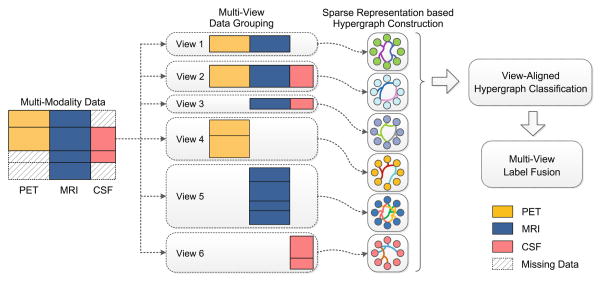

In this paper, we propose a view-aligned hypergraph learning (VAHL) method with incomplete multi-modality data for AD/MCI diagnosis. Different from conventional multi-view based learning methods, VAHL explicitly incorporates the coherence among views into the learning model, where the optimal weights for different views are automatically learned from the data. Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram of our method. We first divide the whole dataset into M views (M = 6 in Fig. 1) according to the data availability in association with different combinations of modalities, followed by a sparse representation based hypergraph construction process in each view space. We then develop a view-aligned hypergraph classification (VAHC) model to explicitly capture the coherence among views. To arrive at a final classification decision, we agglomerate the class probability scores via a multi-view label fusion method.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the proposed view-aligned hypergraph learning method.

2 Method

Data and Pre-processing

A total of 807 subjects in the baseline ADNI-1 database [10] with MRI, PET and CSF modalities are used in this study, which include 186 AD subjects, 226 NCs, and 395 MCI subjects. According to whether MCI would convert to AD within 24 months, the MCI subjects are further divided into two categories: (1) stable MCI (sMCI), if diagnosis was MCI at all available time points (0–96 months); (2) progressive MCI (pMCI), if diagnosis was MCI at baseline but conversion to AD occurred after baseline within 24 months. The 395 MCI subjects are separated into 169 pMCI and 226 sMCI subjects.

Image features are extracted from the MR and PET images based on regions-of-interest (ROIs). Specifically, for each MR image, we perform anterior commissure (AC)-posterior commissure (PC) correction, resampling to size 256 × 256 × 256, and inhomogeneity correction using the N3 algorithm [11]. Skull stripping is then performed using BET [12], followed by manual editing to ensure that both skull and dura are cleanly removed. Next, we remove the cerebellum by warping a labeled template to each skull-stripped image. FAST [12] is applied to segment the human brain into three different tissue types, i.e., gray matter (GM), white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The anatomical automatic labeling (AAL) atlas, with 90 pre-defined ROIs in the cerebrum, is aligned to the native space of each subject using a deformable registration algorithm. Finally, for each subject, we extract the volumes of GM tissue inside the 90 ROIs as features, which are normalized by the total intracranial volume (estimated by the summation of GM, WM and CSF volumes from all ROIs). We align each PET image to its corresponding MR image via affine transformation and compute the mean PET intensity in each ROI as features. We also employ five CSF biomarkers, including amyloid β (Aβ42), CSF total tau (t-tau), CSF tau hyperphosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau), and two tau ratios with respect to Aβ42 (i.e., t-tau/Aβ42 and p-tau/Aβ42). Ultimately, we have a 185-dimensional feature vector for each subject with complete data modalities, including 90 MRI features, 90 PET features, and 5 CSF features.

Multi-view Data Grouping

We group the subjects into 6 views, including “PET+MRI”, “PET+MRI+CSF”, “MRI+CSF”, “PET”, “MRI”, and “CSF”. Here, each view denotes a specific modality or a possible combination of several modalities. As shown in Fig. 1, subjects in View 1 have PET and MRI data, while those in View 6 only have CSF data. This grouping allows us to make use of all data without discarding subjects or introducing imputation artifacts.

Sparse Representation Based Hypergraph Construction

In this study, we formulate the AD/MCI diagnosis as a multi-view hypergraph based classification problem, where one hypergraph is constructed in each view space. Let 𝒢m = (𝒱m, ℰm, wm) denote the hypergraph with Nm vertices corresponding to the m-th view, where 𝒱m is a vertex set with each vertex representing a subject, ℰm denotes a hyperedge set with hyperedges, and is the corresponding weight vector for hyperedges. Denote as the vertex-edge incidence matrix, with the (v, e)-entry indicating whether the vertex v is connected with other vertices in the hyperedge e.

In conventional hypergraph based methods [8], the Euclidean distance is typically used to evaluate similarity between pairs of vertices. We argue that the Euclidean distance can only model the local structure of data. To this end, we propose a sparse representation (SR) based hypergraph construction method to exploit the global structure of data. Specifically, we first select each vertex as a centroid, and then represent each centroid using the other vertices via a SR model [13]. A hyperedge can then be constructed by connecting each centroid to the other vertices, with global sparse representation coefficients as similarity measurements. Given Nm vertices, we can obtain hyperedges. A larger value for the l1 regularization parameter (i.e., ε) in SR will lead to more sparse coefficients. To capture richer data structure information, we employ multiple (e.g., q) parameters in SR to construct multiple sets of hyperedges, and finally have hyperedges for the hypergraph 𝒢m.

View-Aligned Hypergraph Classification

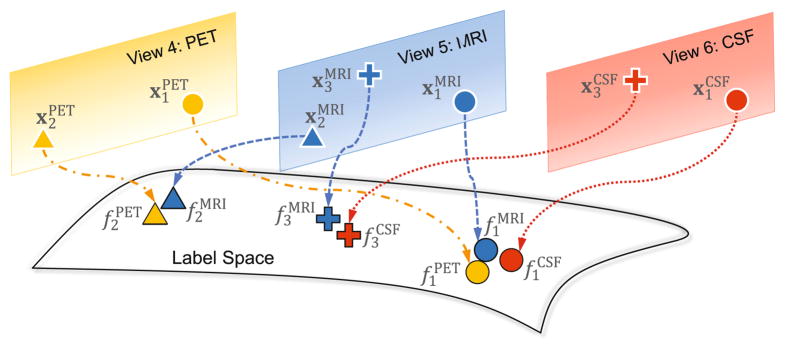

Denote fm as the class probability score vector for N subjects in the m-th view, and F = [f1, ···, fm, ···, fM] ∈ ℝN×M. To model the coherence among different views, we propose a view-aligned regularizer, as illustrated in Fig. 2. For instance, the circles indicate the subject 1 with PET, MRI and CSF features (i.e., and ), respectively. Intuitively, their class probability scores (i.e., and ) should be close to one another, because they represent the same subject. Let Ωm ∈ ℝN×N be a diagonal matrix with the diagonal element if the n-th subject has missing values in the m-th view, and , otherwise. The view-aligned regularizer is then defined as

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the view-aligned regularizer with PET, MRI, and CSF data.

| (1) |

Using the hypergraph constructed in the m-th view, the objective of hypergraph based semi-supervised learning is formulated as [8] min

| (2) |

where the first term is the empirical loss, and the second term is a hypergraph regularizer [8] defined as

| (3) |

where the hypergraph Laplacian matrix is defined as Łm = I − Θm. Here, , where is the diagonal vertex degree matrix and denote the diagonal hyperedge degree matrix. Note that vertex degree for v is defined as , and the hyperedge degree for e is defined as .

Let , where yla represents the label information for labeled data and yun is the label information for the unlabeled data. For the i-th sample, yi = 1 if it is associated with the positive class (e.g., AD), yi = −1 if it belongs to the negative class (e.g., NC), and yi = 0 if its category is unknown. Since different views and hyperedges may play different roles in classification, we learn the weights associated with different views and hyperedges from data. Denote α ∈ ℛM as a weight vector, with the element αm representing the weight for the m-th view. For the m-th hypergraph, we denote as the diagonal matrix of hyperedge weights. Our view-aligned hypergraph classification (VAHC) model is formulated as follows:

| (4) |

where the first term is the square loss, and the second one is the hypergraph Laplacian regularizer. The regularization coefficient (αm)2 is to prevent the degenerate solution of α. The last term and those constraints in Eq. (4) are used to penalize the complexity of the weights (i.e., α) for views and the weights (i.e., Wm) for hyperedges. It is worth noting that the third term in Eq. (4) is the proposed view-aligned regularizer, which encourages that the estimated labels of one subject represented in different views to be similar. Using Eq. (4), we can jointly learn the class probability scores F, the optimal weights for views (i.e., α), and the optimal weights for hyperedges (i.e., ) from data.

Since the problem in Eq. (4) is not jointly convex w.r.t. F, α and , we adopt an alternating optimization method to solve the objective function. First, we optimize F with fixed α and . Given fixed F and α, we optimize in the second step. In the third step, we optimize α with fixed F and . Such alternating optimization process is repeated until convergence. The overall computational complexity of our method is 𝒪(N2).

Multi-view Label Fusion

For a new testing subject z, we now compute the weighted mean of its class probability scores for making a final classification decision. Specifically, its class label can be obtained via , where and αm is the learned weight of the m-th view via VAHL. Note that if z has missing values in a specific modality, the weights for corresponding views associated with this modality will be 0.

3 Experiments

Experimental Settings

We performed three classification tasks, including AD vs. NC, MCI vs. NC, and pMCI vs. sMCI classification. The classification performance was evaluated by accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), and area under the ROC curve (AUC). We compared VAHL with 4 baseline methods, including Zero (with missing values as zeros), KNN, EM [6], and SVD [7]. VAHL was further compared with 4 state-of-the-art methods, including an ensemble-based method [2] with weighted mean (Ensemble-1) and mean (Ensemble-2) strategies, iMSF [3] with square loss (iMSF-1) and logistic loss (iMSF-2), iSFS [4], and matrix shrinkage and completion (MSC) [5].

A 10-fold cross-validation (CV) strategy was used for performance evaluation. To optimize parameters, we performed an inner 10-fold CV using training data. The parameters μ and λ in Eq. (4) were chosen from {10−3, 10−2, ···, 104}, while the iteration number in the alternating optimization algorithm for Eq. (4) was empirically set to 20. Multiple parameter values for ε in the SR model [13] were set to [10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 100] to construct multiple sets of hyperedges in each hypergraph of VAHL. The parameter k for KNN was chosen from {3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 15, 20}. The rank parameter was chosen from {5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30} for SVD, and the parameter λ for iMSF was chosen from {10−5, 10−4, ···, 101}. Results of iSFS [4] and MSC [5] were taken directly from the authors.

Results

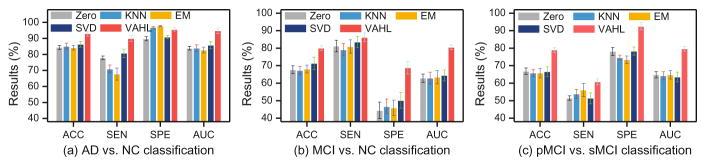

Experimental results achieved by our method and those baseline methods are given in Fig. 3. As can be seen from Fig. 3, our method consistently achieves the best performance in terms of ACC, SEN and AUC in three classification tasks. We further report the comparison between our method and state-of-the-art methods in Table 1, with results demonstrating that our method outperforms those competing methods. For instance, the ACC values achieved by our method are 93.10% and 80.00% in AD vs. NC and MCI vs. NC classification, respectively, which are significantly better than the second best results (i.e., 88.50% and 71.61 %, respectively). Similarly, the results in pMCI vs. sMCI classification show that our method can identify progressive MCI patients from the whole population more accurately than the state-of-the-art methods.

Fig. 3.

Performance of VAHL and baseline methods in three classification tasks.

Table 1.

Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods

| Method | AD vs. NC | MCI vs. NC | pMCI vs. sMCI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC (%) | SEN (%) | SPE (%) | AUC (%) | ACC (%) | SEN (%) | SPE (%) | AUC (%) | ACC (%) | SEN (%) | SPE (%) | AUC (%) | |

| Ensemble-1 [2] | 83.03 | 78.54 | 86.72 | 89.82 | 62.58 | 65.42 | 57.73 | 64.40 | 68.10 | 55.44 | 77.77 | 64.60 |

| Ensemble-2 [2] | 81.07 | 76.37 | 84.94 | 87.39 | 61.61 | 64.16 | 57.28 | 62.07 | 65.56 | 51.15 | 75.41 | 61.78 |

| iMSF-1 [3] | 86.41 | 76.91 | 94.24 | 85.57 | 70.64 | 81.62 | 54.42 | 63.02 | 65.82 | 56.90 | 72.38 | 68.20 |

| iMSF-2 [3] | 86.97 | 75.78 | 93.90 | 86.34 | 71.61 | 82.83 | 54.73 | 63.78 | 64.55 | 56.85 | 70.22 | 66.00 |

| iSFS [4] | 88.48 | 88.95 | 88.16 | 88.56 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| MSC [5] | 88.50 | 83.70 | 92.70 | 94.40 | 71.50 | 75.30 | 64.90 | 77.30 | - | - | - | - |

| VAHL (ours) | 93.10 | 90.00 | 95.65 | 94.83 | 80.00 | 86.19 | 68.78 | 80.49 | 79.00 | 60.80 | 92.53 | 79.66 |

We also conduct experiments using VAHL based on complete data (with PET, MRI and CSF modalities), and achieved the accuracies of 89.23 %, 78.50% and 78.00% in AD vs. NC, MCI vs. NC, and pMCI vs. sMCI classification, respectively. These results are worse than the results of using all subjects with incomplete data, implying that subjects with missing data can provide useful information. Then, we compare VAHL with its variant named VAHL-1 (without the view-aligned regularizer), and the accuracies achieved by VAHL-1 are 85.24 %, 75.16% and 75.25% in the three classification tasks, respectively. Such results imply that our view-aligned regularizer plays an important role in VAHL.

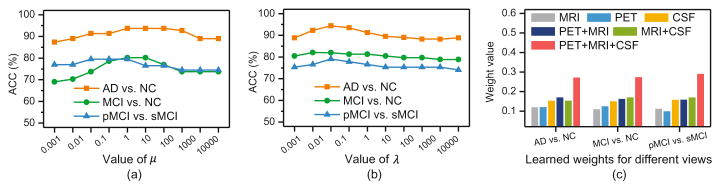

We further investigate the influence of parameters and the weights for different views learned from Eq. (4), with results shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4(a) indicates that the best results are achieved by VAHL when 0.1 ≤ μ ≤ 100 and 0.01 ≤ λ ≤ 10 in three tasks. From Fig. 4(c), we can observe that the learned weights for the “PET+MRI+CSF” view are much larger than those of the other five views, implying that this view contributes the most in three tasks.

Fig. 4.

Influence of parameters (a–b) and learned weights for different views (c).

4 Conclusion

We propose a view-aligned hypergraph learning (VAHL) method using incomplete multi-modality data for AD/MCI diagnosis. Specifically, we first group data into several views according to the availability of modalities, and construct one hypergraph in each view using a sparse representation based hypergraph construction method. We then develop a view-aligned hypergraph classification model to explicitly capture coherence among views, as well as to automatically learn the optimal weights of different views from data. A multi-view label fusion method is employed to arrive at a final classification decision. Results on the baseline ADNI-1 database (with MRI, PET, and CSF modalities) demonstrate the efficacy of our method in AD/MCI diagnosis with incomplete data.

Acknowledgments

D. Shen—This study was supported in part by NIH grants (EB006733, EB008374, EB009634, MH100217, AG041721, AG042599, AG010129, AG030514, and NS093842).

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2007;3(3):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingalhalikar M, Parker WA, Bloy L, Roberts TPL, Verma R. Using multiparametric data with missing features for learning patterns of pathology. In: Ayache N, Delingette H, Golland P, Mori K, editors. MICCAI 2012. LNCS. Vol. 7512. Springer; Heidelberg: 2012. pp. 468–475. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33454-2 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan L, Wang Y, Thompson PM, Narayan VA, Ye J. Multi-source feature learning for joint analysis of incomplete multiple heterogeneous neuroimaging data. Neuro Image. 2012;61(3):622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang S, Yuan L, Fan W, Wang Y, Thompson PM, Ye J. Bi-level multi-source learning for heterogeneous block-wise missing data. Neuro Image. 2014;102:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thung KH, Wee CY, Yap PT, Shen D. Neurodegenerative disease diagnosis using incomplete multi-modality data via matrix shrinkage and completion. Neuro Image. 2014;91:386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider T. Analysis of incomplete climate data: estimation of mean values and covariance matrices and imputation of missing values. J Clim. 2001;14(5):853–871. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golub GH, Reinsch C. Singular value decomposition and least squares solutions. Numer Math. 1970;14(5):403–420. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou D, Huang J, Schölkopf B. Learning with hypergraphs: Clustering, classification, and embedding. NIPS. 2006:1601–1608. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Wang M, Tao D, Ji R, Dai Q. 3-D object retrieval and recognition with hypergraph analysis. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2012;21(9):4290–4303. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2012.2199502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Fox NC, Thompson P, Alexander G, Harvey D, Borowski B, Britson PJ, Whitwell L, Ward C. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(4):685–691. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuro Image. 2012;62(2):782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright J, Yang AY, Ganesh A, Sastry SS, Ma Y. Robust face recognition via sparse representation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal. 2009;31(2):210–227. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2008.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]