Abstract

Fluorescent proteins, such as green fluorescent protein and red fluorescent protein (DsRED), have become frequently used reporters in plant biology. However, their potential to monitor dynamic gene regulation is limited by their high stability. The recently made DsRED-E5 variant overcame this problem. DsRED-E5 changes its emission spectrum over time from green to red in a concentration independent manner. Therefore, the green to red fluorescence ratio indicates the age of the protein and can be used as a fluorescent timer to monitor dynamics of gene expression. Here, we analyzed the potential of DsRED-E5 as reporter in plant cells. We showed that in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) mesophyll protoplasts, DsRED-E5 changes its fluorescence in a way similar to animal cells. Moreover, the timing of this shift is suitable to study developmental processes in plants. To test whether DsRed-E5 can be used to monitor gene regulation in plant organs, we placed DsRED-E5 under the control of promoters that are either up- or down-regulated (MtACT4 and LeEXT1 promoters) or constitutively expressed (MtACT2 promoter) during root hair development in Medicago truncatula. Analysis of the fluorescence ratios clearly provided more accurate insight into the timing of promoter activity.

Reporter genes are useful tools to study gene expression in transformed organisms. The most widely used reporters in plants are uidA (β-glucuronidase [GUS]; Jefferson et al., 1987), luciferase (Ow et al., 1986), and genes encoding fluorescent proteins including green fluorescent protein (GFP), yellow fluorescent protein, cyan fluorescent protein, and red fluorescent protein (DsRED; Chalfie et al., 1994; Chalfie, 1995; Cubitt et al., 1995; Matz et al., 1999). Compared to GUS and luciferase, which require the addition of specific substrates to monitor reporter activity, fluorescent proteins, due to their intrinsic fluorescence, allow noninvasive detection in living cells without the addition of substrates. This enables, for example, real time visualization of gene expression or analysis of transformants in the first generation.

Derivatives of the Aequorea victoria GFP (e.g. eGFP, RS-smGFP; Cormack et al., 1996; Davis and Vierstra, 1998) are the most commonly used fluorescent reporters. They are attractive because of their high quantum yield (0.60 and 0.67, respectively, for eGFP and RS-smGFP; Tsien, 1998) and stability (estimated half life of approximately 1 d; Verkhusha et al., 2003). In addition to GFP, DsRED has been isolated from a coral of the genus Discosoma (Matz et al., 1999). DsRED has an excitation and emission maximum shifted to the red when compared to GFP (excitation/emission maximum of GFPs 488–495 nm/507–510 nm versus 558 nm/583 nm for DsRED). Moreover DsRED and GFP fluorescence can be easily discriminated using appropriate filter settings, allowing simultaneous multicolor imaging of different genes (Jach et al., 2001).

Although GFP and DsRED are very useful reporter genes in living cells, their high stability (half life of GFP approximately 1 d and of DsRED1 approximately 4.6 d; Verkhusha et al., 2003) makes them less useful for monitoring dynamic processes such as transient changes in gene expression. Recently the DsRED-E5 variant was isolated that might be used to circumvent this problem (Terskikh et al., 2000). Both DsRED and DsRED-E5 form a green fluorescent intermediate before maturing to the red fluorescent configuration (Baird et al., 2000; Terskikh et al., 2000). Compared to DsRED, the DsRED-E5 green fluorescent configuration has a higher intensity and, therefore, can be easily detected. As a consequence, DsRED-E5 fluorescence shifts from green to red during maturation of the protein, with yellow and orange intermediate fluorescence, due to the presence of both green and red fluorophores. The maturation from green to red fluorescence occurs, in vitro, in about 18 h and is rather unaffected by pH, ionic strength, or protein concentration. These properties indicate that the ratio of green to red fluorescence can be used to determine the age of DsRED-E5 protein, which could facilitate the visualization of dynamics in gene regulation (Terskikh et al., 2000).

Here we studied the potential of DsRED-E5 as a reporter gene in plants. We used a transient expression system, cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) mesophyll protoplasts, to determine its fluorescent properties (e.g. color conversion over time) in plant cells. Further, we investigated whether DsRED-E5 can visualize dynamics of promoter activity in Medicago truncatula root hairs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of DsRED-E5 Fluorescence in Cowpea Mesophyll Protoplasts

To characterize the fluorescent properties of DsRED-E5 in plant cells, we cloned the DsRED-E5 coding region in the vector pMon999e35S, carrying the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. The resulting 35S::DsRED-E5 transgene was transiently expressed in cowpea mesophyll protoplasts isolated from leaf tissue. After transfection, protoplasts were analyzed for green and red fluorescence over time by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM; see “Materials and Methods” and below for more details).

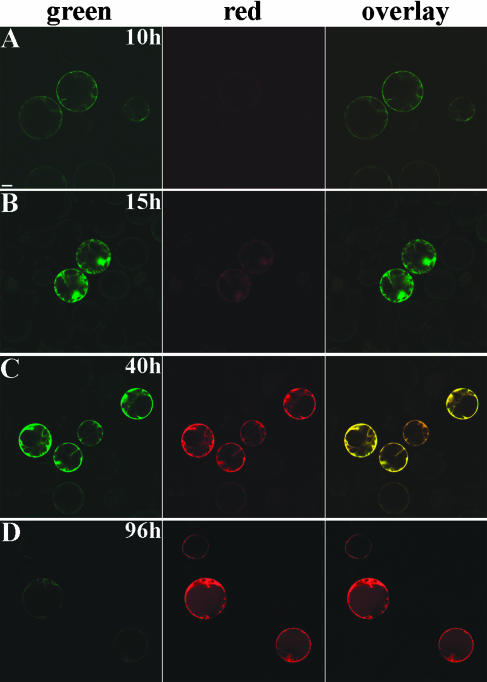

Protoplasts carrying the 35S::DsRED-E5 construct became fluorescent 9 to 10 h after transfection (Fig. 1A). At this time point, only green fluorescence was detectable (Fig. 1A). Red fluorescence appeared in these protoplasts 14 to 15 h after transfection (Fig. 1B) and increased in intensity over time (Fig. 1, C and D). These data show that DsRED-E5 shifts its fluorescence from green to red over time in plant cells also, suggesting that DsRED-E5 is suitable to study dynamic processes in plants.

Figure 1.

Confocal fluorescence images of cowpea protoplasts transiently expressing DsRED-E5 under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter, 10 h (A), 15 h (B), 40 h (C), and 96 h (D) after transfection. Bar represents 10 μm.

To obtain a better idea of the timing of DsRED-E5 fluorescence maturation in plants, we determined the ratio between the green and the red fluorescence intensities in the DsRED-E5 expressing protoplasts at different time points after transfection. This ratio will be defined as G/R.

The optimal wavelengths to excite the green and the red form of dsRED-E5 are 488 nm and 558 nm, respectively. Alternatively, a single excitation wavelength can be used to excite both forms due to the overlap of their excitation spectra. The use of two different wavelengths to excite dsRED-E5 (488 nm and 543 nm) has major disadvantages. A pronounced photobleaching of DsRED-E5 was observed, especially at the high laser power required to excite DsRED-E5 in root hairs (see below). This photobleaching would affect the fluorescence intensity measured after excitation with the second laser, and therefore the data would be unreliable. Further, the use of two lasers to excite DsRED-E5 could lead to variations in the fluorescence intensities due to laser instability over time. The use of a single excitation wavelength for both emitting forms will overcome these problems. Therefore, we decided to use a single argon laser (488 nm) to excite both the green and the red emitting form of DsRED-E5.

The green emitting form of DsRED-E5 has a broad emission spectrum that extends from 475 to 625 nm and is similar to that of GFP (Tsien, 1998; Terskikh et al., 2000). Using the 488 nm laser to excite DsRED-E5, this broad spectrum causes a bleed-through in the red channel (emission, band pass 565–595 nm) by the green fluorescent form. To quantify this, we measured the fluorescence intensity in the red channel of protoplasts expressing GFP. As expected from the emission spectrum, a signal was detected in the red channel, which was significantly higher than the background level (autofluorescence) of nontransfected protoplasts. After subtracting the background level, the fluorescence detected in the red channel was 15% of the fluorescence intensity measured in the green channel. Moreover, by analyzing several protoplasts (n = 20) we observed that this relative value was independent of the absolute fluorescence intensity (data not shown). Based on these data we concluded that the intensity of the red channel had to be reduced by 15% of the intensity detected in the green channel. In contrast, the red fluorescent form does not cause any bleed-through in the green channel.

To determine G/R in the DsRED-E5 expressing protoplasts, approximately 20 protoplasts for each time point were analyzed by CLSM. Within a transfection experiment, protoplasts show a high heterogeneity of signal intensity. To determine G/R, protoplasts were randomly selected and therefore they express DsRED-E5 at different levels. The green and red fluorescences were corrected for the background signal observed in nontransfected protoplasts as well as for the above described bleed-through in the red channel. About 10 h after transfection, G/R was between 15 and 10 (12 ± 2.3 [sd]; n = 20; Fig. 1A) and subsequently decreased in time reaching a value of 1 (1 ± 0.6; n = 22) at approximately 40 h after transfection (Fig. 1C). From this time point on, G/R was lower than 1 and reached the lowest value of 0.17 (0.17 ± 0.02; n = 20) 95 to 105 h after transfection (Fig. 1D). The differences in G/R over time corresponded to clear differences in the hue color of the protoplasts (Fig. 1, overlay). The protoplasts in fact shifted from a bright green fluorescence, observed in the first hours after transfection, to yellow-orange, and finally to a red fluorescence, when the red emitting form was predominantly present (Fig. 1, overlay). Moreover, at a specific time point, G/R was similar in the different protoplasts although fluorescence intensities varied. For instance, the values of the G/R measured in protoplasts 25 and 90 h after transfection were of 2.73 ± 0.40 (n = 105) and 0.20 ± 0.02 (n = 62), respectively. The low sd values show that the rate of green to red conversion is independent of DsRED-E5 concentration and therefore from the level of gene expression within a cell (Terskikh et al., 2000). This means that when DsRED-E5 is continuously expressed, a steady-state value of the G/R will be reached that is independent of the promoter strength. Perturbations in the steady-state G/R value can be used to detect changes in promoter activity, for example during development or after application of a stimulus. A G/R higher than the steady-state value will indicate a recent induction of the promoter activity, whereas a lower value of the G/R will mean that the promoter activity has ceased. The loss of green fluorescence in the transfected protoplasts is most likely due to decreasing translation efficiency over time (Rottier, 1980).

Characterization of DsRED-E5 Maturation in Cowpea Mesophyll Protoplasts

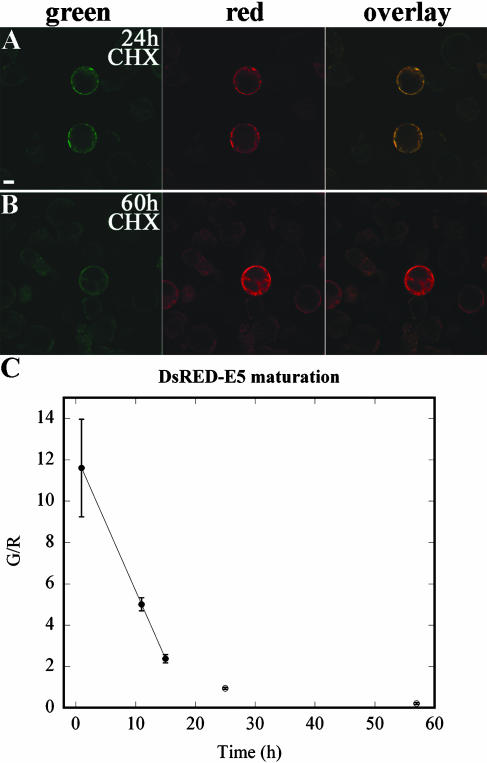

Next we determined the time required for the green form of DsRED-E5 to mature into the red form. From the experiment described above, it appeared that the rate of this maturation is in the order of 1 to 2 d. A more precise estimation could not be determined in this experiment since, under our experimental condition, the rate of protein synthesis changes over time (Rottier, 1980). As a consequence, the steady-state G/R was never reached in protoplasts. To determine the rate of DsRED-E5 maturation more accurately, we used an experimental set-up in which the green form of DsRED-E5 was first accumulated and subsequently protein synthesis was blocked by applying cycloheximide (CHX). CHX was applied 10 h after transfection, when G/R had the highest value (>10). Subsequently, G/R was followed in time.

After CHX application, the fluorescence intensity remained constant in the treated protoplasts, whereas it increased in the untreated sample (data not shown), indicating that the CHX treatment was effective. Moreover, G/R decreased rapidly and more or less in a linear manner within the first 14 h after CHX treatment from the initial value of 11.6 ± 2.36 (n = 23) to 2.37 ± 0.20 (n = 19) at 14 h (Fig. 2C). After this time point, a residual level of green fluorescent form remained in the protoplasts and G/R decreased slower (Fig. 2C), reaching a value of 0.93 ± 0.05 (n = 23; Fig. 2, A and C) and the lowest value of approximately 0.2 ± 0.05 (n = 21), respectively, approximately 24 and 55 to 60 h after CHX application (Fig. 2, B and C). These data show that once DsRED-E5 synthesis stopped, G/R decreased 10-fold in approximately 24 h, whereas under the same experimental condition, the intensity of GFP fluorescence remained about constant (data not shown). Therefore, DsRED-E5 is more suitable than other reporter genes to study regulation of gene activity during plant developmental processes.

Figure 2.

Confocal fluorescence images of cowpea protoplasts transiently expressing DsRED-E5 under CaMV 35S promoter 24 h (A) and 60 h (B) after 50 μg/mL CHX application. Bar represents 10 μm. C, Maturation rate of DsRED-E5 in cowpea protoplasts. G/R is depicted as function of time. Errors bar indicate sd. At least 20 protoplasts were analyzed for each time point.

DsRED-E5 as Reporter in M. truncatula Roots

To determine whether the fluorescent timer could be used as a reporter for studying promoter regulation in plant organs, we analyzed the potential of DsRED-E5 to reveal changes in promoter activity during a dynamic process such as root hair development. Root hairs were selected since they protrude from the epidermal cells, by which they are accessible for microscopic analysis. Root hair development has been investigated in detail in several plant species including M. truncatula (Sieberer and Emons, 2000). Due to the indeterminate growth of the root, root hairs of different ages are present along the root axis, with the youngest hairs near the root tip and the oldest near the hypocotyl. Root hair development starts with the formation of a bulge on the epidermal cells. These bulges are formed by isotropic growth and their cytoplasm is located at the periphery, whereas the vacuole is present in the bulge center (Sieberer and Emons, 2000). Subsequently, a root hair is formed from the bulge by tip growth. A cytoplasmic dense region, devoid of large organelles, at the tip characterizes growing root hairs. In mature (nongrowing) root hairs, this region has disappeared and the cellular volume is completely occupied by a large vacuole with a thin layer of cytoplasm located at the periphery (Sieberer and Emons, 2000). At the transition from a growing to a nongrowing phase (growth terminating hairs), the cytoplasmic dense region at the hair tip becomes smaller and the vacuole extends toward the hair tip. Under our experimental condition the development from a bulge to a mature root hair takes 20 to 24 h—a time span in which DsRED-E5 maturation could be used to monitor differences in promoter activity.

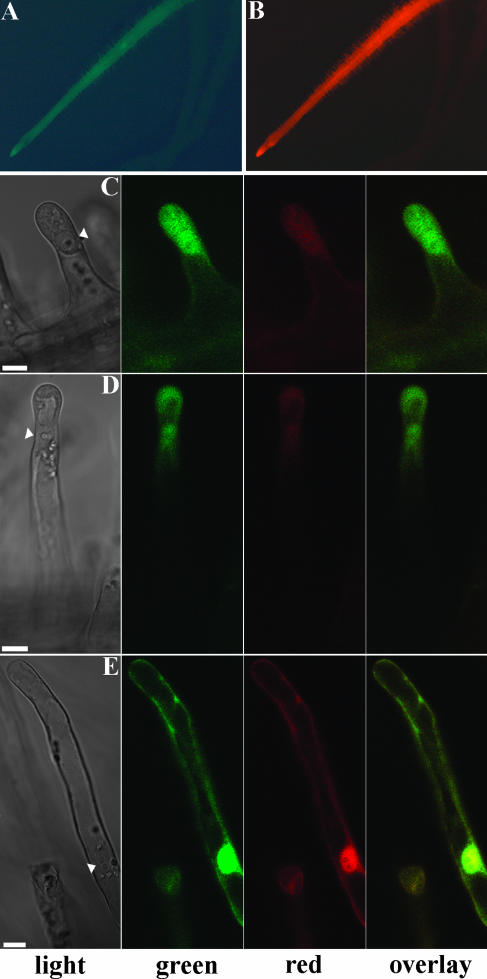

To test whether DsRED-E5 can be used as a reporter to study regulation of gene activity in root hairs, we used three different promoters, one of which is constitutively expressed in all cells of the root, including the epidermis, and the other two are induced during root epidermis development. As a constitutively expressed promoter, we selected the M. truncatula ACTIN2 (MtACT2) promoter (R. Mirabella, C. Franken, R. Geurts, and T. Bisseling, unpublished data). Such a constitutive promoter can be used to determine the steady-state value of the G/R in root hairs. Therefore we placed DsRED-E5 under the control of the MtACT2 promoter and introduced the MtACT2::DsRED-E5 fusion into M. truncatula roots by Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated root transformation. Transformed roots were identified scoring for DsRED-E5 fluorescence under a stereo fluorescence macroscope. The fluorescence pattern confirmed that the MtACT2 promoter is constitutively expressed in roots: the signal was visible in the root meristem, in the epidermis, and in root hairs in all stages of development (Fig. 3, A and B). MtACT2::DsRED-E5 expressing root hairs were further analyzed by CLSM, and G/R in root hairs at different developmental stages was measured. The background signal detected in nontransformed root hairs and the bleed-through of the green signal into the red channel were taken into account as described above. The data presented here come from the analysis of five roots independently transformed with the MtACT2::DsRED-E5 fusion (Table I). In bulges, growing hairs (Fig. 3C), growth terminating (Fig. 3D), and “young mature” hairs (Fig. 3E), in a region of 0.5 mm above the growth terminating hairs, G/R had a value of approximately 2.8 (respectively, 2.84 ± 0.33 [n = 33], 2.78 ± 0.18 [n = 22], and 2.66 ± 0.25 [n = 15]; Table I). This value was lower in “old mature” root hairs, closer to the hypocotyl (data not shown), probably due to an overall reduction of protein synthesis in old root hairs. These data show that the value of G/R is constant in the region between bulges and young mature root hairs, indicating that a steady-state G/R level of approximately 2.8 is reached at these stages. Moreover, the values of the G/R were similar in independently transformed roots (Table I), confirming that also in M. truncatula root hairs G/R is independent of the expression level of the transgene. Further, the G/R value was uniform within one root hair (data not shown).

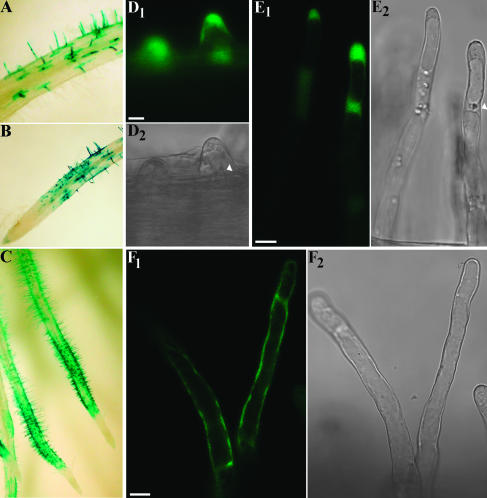

Figure 3.

Expression pattern of the MtACT2 promoter in M. truncatula roots transformed with the MtACT2::DsRED-E5 fusion. A and B, MtACT2 promoter expression pattern in roots. Images were collected with the Leica stereo fluorescence macroscope using GFP (A) and DsRED (B) filter sets, respectively. C to E, Confocal fluorescence images of growing (C), growth terminating (D), and young mature (E) root hairs transformed with MtACT2::DsRED-E5. Nucleus is indicated by the arrowhead. Bars represent 10 μm.

Table I.

G/R in root hairs expressing different promoter::DsRED-E5 transgenes

| Root | Growing Root Hairs | Growth Terminating Root Hairs | Young Mature Root Hairs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgene | MtACT2::DsRED-E5 | ||

| Root 1 | 2.93 ± 0.34 (n = 6) | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 5) | 2.86 ± 0.17 (n = 4) |

| Root 2 | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 6) | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 5) | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 2) |

| Root 3 | 2.75 ± 0.22 (n = 10) | 2.66 ± 0.19 (n = 5) | 2.51 ± 0.23 (n = 3) |

| Root 4 | 2.96 ± 0.58 (n = 5) | 2.86 ± 0.17 (n = 4) | 2.75 ± 0.12 (n = 2) |

| Root 5 | 2.76 ± 0.43 (n = 6) | 2.6 ± 0.31 (n = 3) | 2.45 ± 0.23 (n = 4) |

| Total | 2.84 ± 0.33 (n = 33) | 2.78 ± 0.18 (n = 22) | 2.66 ± 0.25 (n = 15) |

| Transgene | MtACT4::DsRED-E5 | ||

| Root 1 | 8.55 ± 1.39 (n = 7) | 7.95 ± 1.5 (n = 6) | nd |

| Root 2 | 11.95 ± 2.4 (n = 4) | 11.79 ± 2.48 (n = 5) | 2.87 ± 0.62 (n = 3) |

| Root 3 | 9.9 ± 2.19 (n = 9) | 9.42 ± 1.3 (n = 10) | 3.03 ± 0.55 (n = 8) |

| Total | 9.84 ± 2.26 (n = 20) | 9.56 ± 2.14 (n = 21) | 2.99 ± 0.54 (n = 11) |

| Transgene | LeEXT::DsRED-E5 | ||

| Root 1 | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 3) | 1.58 ± 0.14 (n = 4) | 0.64 ± 0.02 (n = 4) |

| Root 2 | 2.74 ± 0.24 (n = 3) | 1.43 ± 0.06 (n = 5) | 0.58 ± 0.02 (n = 2) |

| Root 3 | 3.08 ± 0.45 (n = 4) | 1.48 ± 0.23 (n = 9) | 0.58 ± 0.07 (n = 3) |

| Root 4 | 3.21 ± 0.89 (n = 21) | 1.45 ± 0.21 (n = 9) | 0.65 ± 0.05 (n = 6) |

| Root 5 | 2.86 ± 0 (n = 5) | 1.39 ± 0.24 (n = 6) | 0.54 ± 0 (n = 4) |

| Root 6 | 3 ± 0.19 (n = 5) | 1.71 ± 0.05 (n = 8) | nd |

| Total | 3.05 ± 0.67 (n = 41) | 1.51 ± 0.22 (n = 41) | 0.61 ± 0.09 (n = 19) |

G/R measured in bulges, growing, growth terminating, and young mature M. truncatula root hairs transformed with MtACT2::DsRED-E5, MtACT4::DsRED-E5, and LeEXT1::DsRED-E5 fusions, respectively. The data presented for each fusion were obtained from 3 to 6 independently transformed roots. G/R are indicated as mean value ± sd. The number of root hairs analyzed per root for each stage of development is indicated between brackets. nd, Not done.

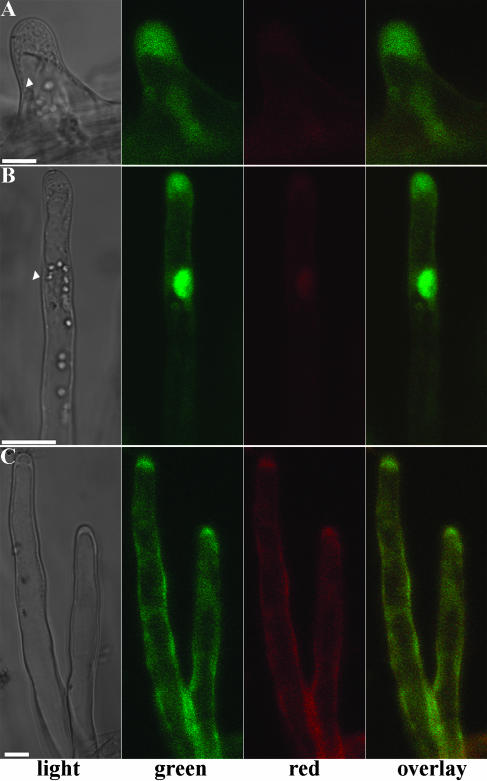

Next we determined whether the induction of promoters in root hairs could be studied using DsRED-E5 as reporter. For this purpose, we chose the ACTIN4 (MtACT4) promoter of M. truncatula, which is induced during root epidermis development (R. Mirabella, C. Franken, R. Geurts, and T. Bisseling, unpublished data). Therefore, we fused DsRED-E5 to the MtACT4 promoter. MtACT4::DsRED-E5 transformed roots were analyzed and G/R was quantified in root hairs of different ages in the region of the root encompassing bulges, growing, growth terminating, and young mature root hairs, in which the steady-state G/R occurred in the MtACT2::DsRED-E5 expressing root hairs. Considering that the steady-state value of the G/R in root hairs is approximately 2.8, values higher than 2.8 indicate recent promoter induction, whereas values below 2.8 indicate down-regulation of the promoter activity. In growing and growth terminating root hairs of MtACT4::DsRED-E5 transformed roots, G/R was 9.84 ± 2.26 (n = 20) and 9.56 ± 2.14 (n = 21), respectively (Fig. 4; Table I). These values being markedly higher than the steady-state value indicates that the MtACT4 promoter is induced in these hairs. Young mature hairs had a value of the G/R of 2.99 ± 0.54 (n = 11), indicating that G/R has almost reached the steady-state level (Fig. 4C; Table I).

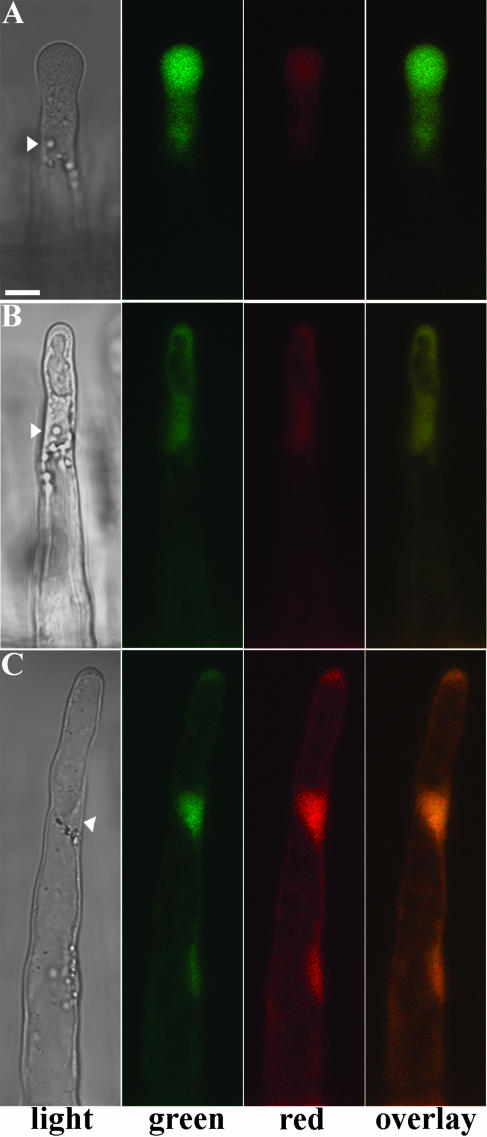

Figure 4.

Expression pattern of the MtACT4 promoter in M. truncatula root hairs transformed with MtACT4::DsRED-E5. Confocal fluorescence images of growing (A), growth terminating (B), and mature old (C) root hairs. Nucleus is indicated by the arrow head. Bars represent 10 μm.

These data clearly indicate that DsRED-E5 can be successfully used to detect the induction of the MtACT4 promoter in root hairs. To determine whether DsRED-E5 is also a useful marker to study repression of gene activity during development, we used the EXTENSIN1 promoter of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill LeEXT1promoter). A LeEXT1::GUS transgene has been shown to be active exclusively in root hairs, both in potato and tobacco (Bucher et al., 2002). The same transgene was introduced into M. truncatula roots and showed that also in M. truncatula the LeExt1 promoter is only active in epidermal cells with a hair (Fig. 5A). GUS activity could be detected as soon as a bulge started to emerge (Fig. 5B), was retained in growing root hairs (Fig. 5B), and became weaker in old mature hairs (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Expression pattern of the LeEXT1 promoter in M. truncatula roots. A to C, Light microscope images of roots transformed with a LeEXT1::GUS fusion. D1–2, E1–2, and F1–2, confocal images of a bulge (D1–2), growth terminating (E1–2), and young mature hairs transformed with a LeEXT1::GFP fusion. D1, E1, and F1, Bright field. D2, E2, and F2, Fluorescence images. Nucleus is indicated by the arrow head. Bars represent 10 μm.

A LeEXT1::DsRED-E5 fusion was introduced in M. truncatula roots. In all the six independent LeEXT1::DsRED-E5 roots analyzed by CLSM, a clear fluorescence was visible only in growing root hairs (Fig. 6A). These growing hairs displayed a G/R of approximately 3 (3.05 ± 0.67 [n = 41]; Table I), which is close to the steady-state level. At an earlier stage of development (bulges), fluorescence was too low to quantify. Growth terminating (Fig. 6B) and young mature hairs (Fig. 6C) had a G/R of approximately 1.5 (1.51 ± 0.22 [n = 41]) and approximately 0.6 (0.61 ± 0.09 [n = 19]), respectively (Table I). The decrease in G/R value was accompanied by a clear shift in the root hair color, from green in growing hairs to orange-red in young mature root hairs (Fig. 6 overlay).

Figure 6.

Expression of the LeEXT1 promoter in M. truncatula root hairs transformed with LeEXT1::DsRED-E5. Confocal fluorescence images of growing (A), growth terminating (B), and young mature (C) root hairs. Nucleus is indicated by the arrow head. Bars represent 10 μm.

In parallel, a LeEXT1::GFP (RS-smGFP) fusion was also introduced into M. truncatula and transformed roots were analyzed by CLSM. The fluorescence could be detected starting from the bulge stage (Fig. 5D) and was present in tip growing, growth terminating, and mature root hairs (Fig. 5, E and F), with a pattern similar to that obtained using GUS as reporter. Moreover the intensity of the GFP fluorescence increased moving from the bulge stage to young mature hairs (data not shown).

In young mature hairs expressing LeEXT1::DsRED-E5, a value of the G/R lower (approximately 0.6) than the steady-state value (approximately 2.8) was reached. This indicates that in these hairs the LeEXT1 promoter activity has been decreased. The down-regulation of the LeEXT1 promoter already occurs in the growth terminating hairs, as indicated by a G/R value already markedly lower than the steady-state value. In contrast, when the LeEXT1::GFP fusion was used, no reduction of the fluorescence intensity was detected in root hairs at these developmental stages (Fig. 5). In these roots, as well as in roots transformed with a LeEXT1::GUS fusion, a decrease of the reporter product could first be observed in the region of the roots with old mature hairs at a distance of about 1.5 to 2 mm from the growth terminating hairs. The time span between the growth terminating stage and the stage where the decrease of GUS or GFP is detected is approximately 24 to 30 h. Therefore, compared to GUS or GFP, DsRED-E5 allows a markedly more precise detection of the timing of LeEXT1 promoter down-regulation. Compared to the MtACT2 promoter, the LeEXT1 promoter is active at a lower level. As a consequence, we did not detect any fluorescence in bulges and the fluorescence signal could be detected for the first time in growing hairs. In these hairs, the value of the G/R had almost reached the steady-state. The observation that as soon as the fluorescence can be detected in growing hairs, G/R is already at the steady-state indicates that the activation of the LeExt1 promoter must have occurred at an earlier stage than growing hairs. This conclusion is in agreement with the expression pattern observed in the LeEXTt1::GUS or the LeEXT1::GFP roots, in which the promoter activity could be detected at earlier stages, namely as soon as the bulges started to emerge from the epidermal cells.

In conclusion, these data show that the fluorescent timer, DsRED-E5, can be used as a marker to monitor both promoter activation and down-regulation in plants, and by determining its G/R a more accurate timing can be obtained. In principal DsRED-E5 is equally suitable as GFP/GUS to determine when a gene is first induced during development, although due to its low quantum yield it is less sensitive than GFP/GUS. On the other hand, DsRED-E5 is most useful to reveal promoter down-regulation, which is hampered by the high stability of conventional reporters like GFP and GUS. In addition, DsRED-E5 can be useful to study increase or decrease of gene activity in cells that already express this gene. For example an external signal might alter the expression level of a certain gene in cells where this gene is already active. In such a case, the timing of this alteration can also be more accurately determined by analyzing the G/R value of DsRED-E5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Manipulation and Plasmid Construction

Molecular biology protocols were conducted according to standard procedures (Sambrook and Russel, 2001), and all fragments generated by PCR were sequenced. To study the expression of DsRED-E5 in protoplasts we used the plant expression vector pMon999e35S (Monsanto, St. Louis). For this purpose, the DsRED-E5 coding region was excised from the vector pTimer (CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA) as an EcoRI-BamHI fragment and subcloned in the same sites of the pMon999e35S vector.

The isolation of the MtACT2 and MtACT4 will be described elsewhere (R. Mirabella, C. Franken, R. Geurts, and T. Bisseling, unpublished data). In short, a 2.8-kb 5′ promoter region of MtACT2 and 2.9-kb region of MtACT4 were PCR amplified using the following primers (with restriction sites used for cloning underlined): 5′ MtACT2p-H, CCCAAGCTTGGATGTGGTTTGGTTAATAG; 3′ MtACT2p-K, GGGGTACCTTGACCATTCCAGTTCC; MtACT4p-S, ACATGCATGCAATTTAGTATATATTTTGGGATGAG; and 3′ MtACT4p-K, GGGGTACCTTGACCATGCCGGTTCC. The amplified fragments contain the putative promoter, the 5′ untranslated region, the first intron, and the coding region of the first 19 amino acids, as used for the analysis of the Arabidopsis ACTIN genes (An et al., 1996). MtACT2 and MtACT4 promoters were fused in-frame to the DsRED-E5 and subsequently cloned in binary vector pBinplus (Van Engelen et al., 1995) containing the NOS terminator. As LeEXT1 promoter, a 1.1-kb fragment of the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) EXTENSIN1 5′ region was used (designated as Δ1.1 in Bucher et al., 2002). This region was amplified by PCR, using the following primers (with restriction sites used for cloning underlined): 5′ EXT1p-H CACAAGCTTTAAGTATGAAT and 3′ EXT1p-XK GCGGTACCTCTAGAAGAAGAATTGGATTCTAAGGC. The amplified fragment was cloned to generate LeEXT1::GUS, LeEXT1::DsRED-E5, and LeEXT1::GFP in the binary vectors pBI101.3 (GUS) or pBinplus containing a NOS terminator (DsRED-E5 and GFP), respectively.

Protoplast Transfection

Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata) protoplasts were prepared and transfected using the polyethylene glycol method as described (van Bokhoven et al., 1993) with 30 μg of plasmid DNA. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated under constant environmental conditions (25°C, light, protoplast medium: 0.6 m mannitol, 10 mm CaCl2, 0.2 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm KNO3, 1 mm MgSO4, 1 μm KI, 0.01 mm CuSO4, 1 μg/mL 2.4 dichloro phenoxy acetic acid, 25 μg/mL gentamycine, pH 5.4) as described by van Bokhoven et al. (1993). To perform the protein synthesis inhibition test, CHX (Sigma, St. Louis) was added to the protoplast medium at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. For microscope analysis, protoplasts were mounted in 8-chambered cover slides (Nalge; Nunc International, Rochester, NY).

Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Transformation

Medicago truncatula (Jemalong A17) root transformation was performed as previously reported (Limpens et al., 2004). Transgenic roots were selected based on green or red fluorescence, using a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) MZFLIII stereo fluorescence macroscope and further analyzed by CLSM. For this purpose, roots were mounted in liquid emergence medium under a glass coverslip (emergence medium containing [g L−1]: KNO3 [2.5], MgSO4 × 7H2O [0.4], NH4H2PO4 [0.3], CaCl2 × 2H2O [0.2], MnSO4 × 4H2O [0.01], H3BO3 [5 × 10−3], ZnSO4 × 7H2O [1 × 10−3], KI [1 × 10−3], CuSO4 × 5H2O [2 × 10−4], NaMoO4 × 2H2O [1 × 10−4], CoCl2 × 6H2O [1 × 10−4], FeSO4 × 7H2O [0.015], and Na2EDTA [0.02]; 1× UM-C vitamins; [Diaz et al., 1989; mg L−1] myoinositol [100] , nicotinic acid [5] , pyriodoxine-HCl [10] , thiamine-HCl [10], Gly [2] ; 1% Suc, and 3 mm MES, pH 5.8). Roots carrying the LeEXT1::DsRED-E5 transgene could not be selected using a stereo fluorescence macroscope because of a low fluorescence intensity. Therefore, CLSM had to be used for the selection, and only those roots with the highest expression level (approximately 5% of the total LeEXT1::DsRED-E5 roots analyzed) could be used to determine the G/R.

Histochemical GUS Analysis

GUS staining was performed according to Jefferson et al. (1987) with few modifications. Plant material was incubated in 0.05% (w/v) 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronic acid (Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) with 3% Suc, 5 μm potassium-ferrocyadine, and 5 μm potassium-ferricyanide. Vacuum was applied for 1 h, and the samples were incubated at 37°C. For imaging, a Nikon (Tokyo) SMZ-U stereomicroscope and a Nikon optiphot-2 bright field microscope were used. Photographs were made using a Nikon coolpix990 digital camera.

Microscopy and G/R Quantification

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss (Jena, Germany) LSM 510 CLSM implemented on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100). Excitation was provided by the 488 nm Ar laser line, controlled by an acousto optical tuneable filter. To separate excitation from emission and to divide the fluorescence emission into the green and red channels, two dichroic beam splitters were used. The HFT 488 dichroic beam splitter was used to reflect excitation and transmit fluorescence emission. A mirror was used to reflect the emitted fluorescence to the NFT 545 secondary beam splitter. Fluorescence reflected by the NFT 545 splitter was filtered through a 505 to 530 nm band pass filter, resulting in the green channel, whereas fluorescence transmitted by the NFT 545 splitter was filtered through a 565 to 590 nm band pass filter, resulting in the red channel. A Zeiss plan-neofluar 40× (N.A. 1.3) oil immersion objective lens was used for scanning. For detection of green and red fluorescence, equal detection settings were used. For imaging root hairs, the pinhole was fully open. To determine G/R, time series images were acquired. To quantify the fluorescence intensities, equally sized regions of interest were drawn in cytoplasmic rich regions of protoplasts/root hairs and the pixel intensities in these regions were determined using the Zeiss LSM 510 software.

Distribution of Materials

Upon request, all new materials described in this publication will be available and will be distributed in a timely manner.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers AJ809891 and AJ809892.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Pouwels and Dr. M. Bucher for providing us the pMon999e35S vector and the LeEXTENSIN1 promoter, respectively. We are grateful to Dr. M. Hink for the help with CLSM and to J. Vermeer for the helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the European Community Training and Mobility of Researchers program FMRX CT 980239 (grant to R.M.).

References

- An Y-Q, Mc Dowell JM, Huang S, Mc Kinney EC, Meagher RB (1996) Strong, constitutive expression of the Arabidopsis ACT2/ACT8 actin subclass in vegetative tissues. Plant J 10: 107–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY (2000) Biochemistry, mutagenesis, and oligomerization of DsRED, a red fluorescent protein from coral. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11984–11989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher M, Brunner S, Zimmermann P, Zardi GI, Amrhein N, Willmitzer L, Riesmeier JW (2002) The expression of an extensin-like protein correlates with cellular tip growth in tomato. Plant Physiol 128: 911–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M (1995) Green fluorescent protein. Photochem Photobiol 62: 651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC (1994) Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science 263: 802–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S (1996) FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173: 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt AB, Heim R, Adams SR, Boyd AE, Gross LA, Tsien RY (1995) Understanding, improving and using green fluorescent proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SJ, Vierstra RD (1998) Soluble, highly fluorescent variants of green fluorescent protein (GFP) for use in higher plants. Plant Mol Biol 36: 521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz CL, Melchers LS, Hooykaas PJJ, Lugtenberg BJJ, Kijne KW (1989) Root lectin as a determinant of host-plant specificity in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Nature 338: 579–581 [Google Scholar]

- Jach G, Binot E, Frings S, Luxa K, Schell J (2001) Use of red fluorescent protein from Discosoma sp. (dsRED) as a reporter for plant gene expression. Plant J 28: 483–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AR, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW (1987) Gus fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J 6: 3901–3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Ramos J, Franken C, Raz V, Compaan B, Franssen H, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2004) RNA interference in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot 55: 983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz MV, Fradkov AF, Labas YA, Savitsky AP, Zaraisky AG, Markelov ML, Lukyanov SA (1999) Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nat Biotechnol 17: 969–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow DV, Wood KV, DeLuca M, De Wet JR, Helinski DR, Howell SH (1986) Transient and stable expression of the firefly luciferase gene in plant cells and transgenic plants. Science 234: 856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottier P (1980) Viral protein synthesis in cowpea mosaic virus infected protoplasts. PhD thesis. University of Wageningen, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Sambrook J, Russel DW (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Sieberer B, Emons AMC (2000) Cytoarchitecture and pattern of cytoplasmic streaming in root hairs of Medicago truncatula during development and deformation by nodulation factors. Protoplasma 214: 118–127 [Google Scholar]

- Terskikh A, Fradkov A, Ermakova G, Zaraisky A, Tan P, Kajava AV, Zhao X, Lukyanov S, Matz M, Kim S, et al (2000) “Fluorescent timer”: protein that changes color with time. Science 290: 1585–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY (1998) The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 509–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bokhoven H, Verver J, Wellink J, Kammen A (1993) Protoplasts transiently expressing the 200K coding sequence of cowpea mosaic virus B-RNA support replication of M-RNA. J Gen Virol 74: 2233–2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Engelen FA, Molthoff JW, Conner AJ, Nap J-P, Pereira A, Stiekema WJ (1995) pBINPLUS: an improved plant transformation vector based on pBIN19. Transgenic Res 4: 288–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhusha VV, Kuznetsova IM, Stepanenko OV, Zaraisky AG, Shavlovsky MM, Turoverov KK, Uversky VN (2003) High stability of Discosoma DsRed as compared to Aequorea EGFP. Biochemistry 42: 7879–7884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]