Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the major causes of cancer death in women. Many studies have sought to identify specific molecules involved in breast cancer and understand their characteristics. Many biomarkers which are easily measurable, dependable, and inexpensive, with a high sensitivity and specificity have been identified. The rapidly increasing technology development and availability of epigenetic informations play critical roles in cancer. The accumulated data have been collected, stored, and analyzed in various types of databases. It is important to acknowledge useful and available data and retrieve them from databases. Nowadays, many researches utilize the databases, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), and Embase, to find useful informations on biomarkers for breast cancer. This review summarizes the current databases which have been utilized for identification of biomarkers for breast cancer. The information provided by this review would be beneficial to seeking appropriate strategies for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Breast cancer, Database

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer represents one of the most important health problems worldwide among women.1 A number of studies have shown the primary causes of breast cancer and specific molecules involved in breast cancer. Technologies have been developed to improve early detection of breast cancer. Nowadays, therapeutic compounds, synthetic or natural, that can effectively inhibit or control potential molecular targets are available to increase the survival rate of patients suffering from breast cancer.2–5 However, mortality figures remain high and thus researchers continue to seek new therapies against breast cancer.

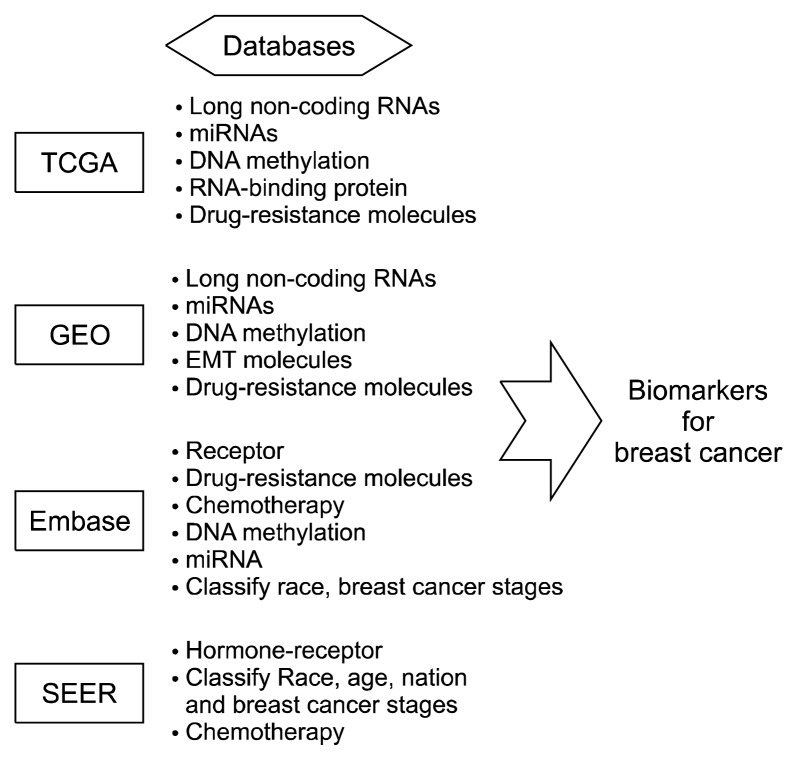

Identification of novel biomarkers would be one of the promising approaches for developing new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Many biomarkers are used to diagnose and to deeply understand diseases. These are easily measurable, dependable, and inexpensive, with a high sensitivity and specificity. These help not only in screening but also in recurrence detection, as they vary with different stages of disease and have diagnostic and predictive value.6 Diverse techniques have been developed for identifying novel biomarkers in many diseases. One of these techniques is biological information indexing and database provision, which helps to find biomarkers and to better understand biological reactions including invasion, metastasis, and proliferation. Different technologies and techniques have been introduced to find biomarkers and to contribute to diseases characterization. Bioinformation is recently growing in the field of cancer biology. The present review summarizes the current meta-data including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), Embase, and Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A scheme for identification of biomarkers for breast cancer using databases including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genome Expression Omnibus (GEO), Embase, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER).

THE CANCER GENOME ATLAS

TCGA is a pilot project started in 2006, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute. The aim of TCGA is to accelerate understanding of diseases by collecting high-dimensional and overall genomic changes in 33 types of cancer such as ovarian, brain, and breast cancer. The TCGA improves prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer via the application of genome analysis and characterization technologies. Tumor DNA and RNA were characterized through a number of approaches in the epigenetic level. The TCGA database has tumor and normal tissues from over 11,000 patients. Researchers who find biomarkers of breast cancer can use TCGA data because it provides accesses without limitation.

Researchers have sought many gene targets from TCGA data, which has been used to find many biomarkers in breast cancer. For example, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) were identified as biomarkers in human breast cancer. A study using 1,000 cases of TCGA data found that LINC00657 plays a crucial role in tumor cell growth and proliferation.7 In addition, FGF 14 antisense RNA2, a novel lncRNA, might act as a tumor suppressor gene and the slow progress of breast cancer.8 The Piwi-interacting RNAs, that play germline maintenance, have been established, and PIWI proteins are potential biomarkers for cancer. Using TCGA dataset, a study found PIWIL3 and PIWIL4 genes using related prognostic relevance.9 MiRNA molecules include many potential biomarkers. MiR-660-5p and miR-574-3p are candidates in breast cancer related to overall survival and recurrence-free survival. BRCA1 expression is regulated by miR-10b, miR-26a, miR-146a, and miR-153 in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC).10,11

Various DNA molecules have been identified as biomarkers for breast cancer. Through TCGA data and patients in the Breast Cancer Care in Chicago, high levels of promoter methylation were found to be strongly associated with hormone-receptor-positive status of breast tumors.12 Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7 expression is related with methylation and it was confirmed from TCGA that hypomethylation of MMP-7 promoter is a prognosis marker.13 Methylation state of DSC2, KCNK4, GSTM1, AXL, DNAJC15, HBII-52, TUSC3, and TES genes may be correlated with worse breast cancer survival in African American.14

RNA-protein complex can be identified as markers. Musashi RNA-binding protein 2 is upstream of ER1 and associated with clinical outcomes.15 The RNA-binging protein Tristetraprolin (TTP, ZFP36) functions as a tumor suppressor, and is related to cAMP response element-binding protein activity regulation. Reduced TTP indicated a poor prognosis in breast cancer.16

Researchers have studied proteins in terms of resistance of anti-cancer drug and ligand. Overexpression of programmed cell death ligand 1 in cell surface generated by phosphatase and tensin homolog loss reduced T-cell proliferation and increased apoptosis, and agents targeting the PI3K pathway might increase the antitumor adaptive immune response.17 Overexpression of pSTAT3 is associated with trastuzumab-resistance in HER2-positive primary breast cancer.18 KLK10 expression was found to contribution to trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. KLK10 and pSTAT3, associtated with trastuzumab resistance molecules, make them potential marker for diagnosis in breast cancer. The triple-negative breast cancer subtype has a poor survival and high resistance to chemotherapy.19

Taken together, the comprehensive molecular analyses of breast cancer by TCGA Network have significantly broadened our knowledge, which may result in improved therapeutic strategies.20 Additional data and analyses are expected from the breast cancer TCGA studies.21 TCGA is coming to a close in early 2017. New NCI genomics initiatives, which run through the Center for Cancer Genomics, will continue to build upon the success of TCGA by using the same model of collaboration for large-scale genomic analysis.22

GENE EXPRESSION OMNIBUS

GEO is a worldwide data repository that distributes next-generation sequencing, microarray, and other forms of high-throughput functional genomics data. Approximately 90% of the data in GEO are gene expression studies in a broad range of biological themes including ecology, disease, metabolism, toxicology, development, evolution, and immunity. The non-expression data in GEO represent other categories of functional genomic and epigenomic studies, including those that examine chromatin structure, genome copy number variations, genome-protein interactions, and genome methylation. The large volume of data may be effectively explored, queried, and visualized using user-friendly Web-based tools. GEO currently stores approximately a billion individual gene expression measurements, derived from over 100 organisms.23

Several studies have identified novel markers using GEO. Several lncRNAs have shown to be good markers. For example, four lncRNAs genes (U79277, AK024118, BC040204, and Ak000974) have been found by random survival forest algorithm on expression signature, indicating that lncRNAs is involved in breast cancer pathogenesis.24 Several lncRNA signatures can be effective biomarkers for metastatic risk in breast cancer patients, improving our understanding of molecular mechanisms in breast cancer invasion.25 Overexpression of cancer-secreted-miR-105, found in metastasis cancer, is related with metastatic progression in early-stage breast cancer. Down-regulated miR-126/miR-126(*) is correlated with poor metastasis-free survival of breast cancer patients.26,27 The DNA methylation pattern is also a marker of breast cancer and breast cancer molecular subtype survival.28

GEO database has been used to identify EMT and metastasis molecules. Polyomavirus enhancer activator 3 protein (Pea3), a member of the Ets-transcription factor family, is elevated in metastatic progression in various type of solid cancer. Overexpression of Pea3 enhances EMT in human breast epithelial cells via transactivation of Snail, an EMT activator.29 WNT5A and B were found to be overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells, compared to those in MCF-7 ER-positive breast cancer cells. WNT5B destruction by WNT and Jun-N-terminal kinase antagonists enhanced MCF-7 invasion. Using GEO, the same study found alternative WNT receptors ROR1 and 2. In MDA-MB-231 cells, WNT signaling is highly related to breast cancer metastasis to brain and ROR1-2 β-catenin-independent WNT signaling showed WNT5A/B expression.30

GEO dataset is used to identify biomarkers in specific drugs-resistance breast cancer. One of these is Lapatinib, a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor that interferes with epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2/neu pathways by treating HER2-positive breast cancer. A study presented a novel strategy for researching the mechanism of laptinib-resistance breast cancers.31 The oncogenic isoform of HER2, HER2Δ16, is expressed with HER2 in nearly 50% of HER2 positive breast tumors, and HER2Δ16 drives metastasis and resistance to drugs including tamoxifen and trastuzumab.32 Other molecules such as thyroid hormone receptor-interacting protein 13, DLDN11, CD44, and midkine protein in breast cancer may be potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.33–36

GEO database contributed to development of technologies and provided information on specific disease characteristics. The aim is enhancing, indexing, linking, searching and displaying capacity in order to permit more data mining.37 The search engine enlarges the data and it can lead to understanding of unidentified relationships between variety of data types, facilitating novel hypothesis generation, or assisting in the analysis of available information.37–39

SURVEILLANCE, EPIDEMIOLOGY AND END RESULTS

SEER is an authoritative source of information on cancer incidence and survival in the United States. SEER currently collects and publishes cancer incidence and survival data from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 28% of the US population. These SEER data, combined with Medicare data, are used to evaluate the prospect of surviving or dying from cancer or from other reason based on a given set of patient and tumor characteristics.40 SEER data is annually updated and provided as a public service in print and electronic formats. These are used by thousands of community groups, researchers, clinicians, policymakers, public health officials, legislators, and the public.

Several studies focused on receptors to identify biomarkers using SEER data. To evaluate the association between tumor’s estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2-neu (HER2) expression and risk of contralateral breast cancer (CBC), SEER datasets were used, including 482 cases diagnosed with a first primary breast cancer (FBC) and a CBC and control women. The TNBC patients increased risk of CBC development compared to patients with HER-2 overexpressing first cancers. HER2-positive breast cancer patients showed a high prevalence of brain invasion and a poor prognosis.41,42 Loss of androgen receptor (AR) expression caused hypermethylation of the AR promoter and AR-negative patients had worse survival.43 However, metaplastic breast cancer was showed no difference survival between hormone-positive and hormone-negative tumors. This data showed that hormone receptors do not improve diagnosis in metaplastic breast cancer.44

Some of studies are analyzed characteristics of diagnosis, survival, and recurrence through age, drug, race, nation, and breast cancer stages. They addressed that these biomarkers, found through differences characteristic, are useful for better treatment, and surgical or radio or hormone therapy.45–48

Proteins biomarkers have been identified as effective therapeutic or prognosis targets. KU70/KU80, DNA damage repair protein, shows higher expression in the BRCA-1 proficient cell line, compared to BRCA-1 deficient cell line.49 Ki-67, a marker for proliferating cells and overexpression in many breast cancers, is a time-varying biomarker of breast cancer in women with atypical hyperplasia.50 High expression of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E is associated with an increased risk for systemic metastasis in node-positive breast cancer patients.51 SEER dataset is used to classify patient survival, status and cancer stage between tumor tissue, positive or negative. Further SEER data may be used to observe clinical outcomes in many cancers with different molecules.

EMBASE

Embase is a biomedical and pharmacological database from biomedical journals. It is special strong in its coverage of drug and pharmaceutical research. There are various studies identifying markers using Embase. Most studies focused on HER-2-positive breast cancer. HER-2-positive metastatic breast cancer is less susceptible to endocrine treatment. The interaction between the response to endocrine treatment and the overexpression of HER-2 was demonstrated in metastatic breast cancer.52 Blocked HER2 was not associated with risk of treatment-related mortality.53

Other studies using Embase show relations between drugs and breast cancer. There are many factors in treating metastatic breast cancer. COX-inhibiting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug has protective effects on breast cancer risk and disease progression. COX-2 is expressed in normal breast epithelium, ductal carcinoma in situ of breast (DCIS), and in invasive breast cancer. COX-2 expressions are comparable to DCIS and invasive breast cancer.54 Analysis of Embase data showed that mixed chemotherapy can give a better prognosis than mono-therapy.55–58 Meta-analysis was conducted to find relationships between positive survivin expression and poor overall survival in breast cancer and lymph node metastasis patients. Overexpression of survivin indicated a significantly higher risk of recurrence and reduced overall survival.59,60

Up-regulated enhancer of zeste homologue 2, epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes in cancer, might be associated with pathological types, histological grade, ER negativity, PR negativity, HER-2 positivity, and high expression of p53 in breast cancer.61 Methylation of adenomatous polyposis coli, is known as an antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway via the inactivation of β-catenin, was higher in breast cancer than controls and significantly reduced in early-stage compared to late-stage breast cancer patients.62

Several microRNAs are clinically proven targets. MiRNA-21, overexpressed in breast cancer, has been found to be a novel biomarker, while some studies demonstrate that miR-21 has a poor prognosis.63–67 Overexpression of miR-155 was found in HER-2- positive or lymph node metastasis-positive, or p53 mutant-type of breast cancer.68

The expression levels of B-cell-specific moloney leukemia virus insertion site (Bmi)-1 differ by race. Increased Bmi-1 expression was a negative predictor for overall survival in Asian patients, whereas overexpressed Bmi-1 was correlated with better overall survival in Caucasian patients.69

Embase data provide wide-ranging information about drug-cancer relationships, molecular expression between races, stages of breast cancer and characteristics of breast cancer. Further studies would be required to investigate more accurate and crucial evidence for prognostic and therapeutic targets using Embase data.

OTHERS

Ovid provides more than 100 core and niche databases to support the breadth of research needed in a wide range of disciplines including clinical medicine and pharmacology. The powerful combination of Ovid’s rich database implementation with Ovid’s advanced search features, sophisticated linking technology, customizable display options, and natural language processing, offers a unique, integrated database solution that is effective for a wide range of users.70 The examples are as follows. HER2 overexpression shows a worse diagnosis and adjuvant therapy in patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma.71 Positive MMP-9 expression represents a higher risk of recurrence and a worse survival in breast cancer patients.72 Sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1) is important in the pathological cancer genesis, progression, and metastasis processes. SK1 mRNA and protein expression levels were increased in cancer tissues and related to shorter and overall survival.73 Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin plays a crucial function in cell proliferation, survival, and morphogenesis in breast cancer, and Decoy receptor 3 is involved in development and prognosis of women reproductive cancers, tumorigenesis and progression.74,75

Gene Expression-Based Outcome (GOBO) is a multifunctional online tool that can use a 181-sample breast cancer dataset and 51-sample breast cancer cell line set. GOBO data can be applied to gene expression level, identification of co-expressed genes of potential metagenes, and relation with outcome for gene expression level.76 Transcriptional regulator megakaryoblastic leukemia-1-induced tenascin-C and SAP domain are key players for breast cancer progression and migration.77 The association between let-7c, miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-21-5p and breast cancer was revealed.78 E26 transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor regulate the expression of genes involved in biological processes. Friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI1) is an ETS protein aberrantly expressed in retrovirus-induced hematological tumors. Down-regulated FLI1 in breast cancer may enhance tumor progression and is related with poor survival and more aggressive phenotypes of breast cancers.79

Small molecule-miRNA Network-Based Inference (SMiR-NBI) is used for predicting new cancer pharmacogenomics mechanisms for small molecules as well as miRNAs. This model was built using a network-based inference algorithm, based on a comprehensive reported dataset. Eleven onco-miRNAs (e.g., miR-20a-5p, miR-27a-3p, miR-29a-3p, and miR-146a-5p) from the top 20 predicted miRNAs provided in the SIiR-NBI model, were down-regulated after metformin in MDA-MB-231 cells. The SMiR-NBi model can be a powerful tool to find potential biomarkers characterized by miRNAs in the emerging field of cancer medicine.80

The Georgetown database of cancer (G-DOC) is a precision medicine platform containing molecular and clinical data from thousands of patients and cell lines, along with tools for analysis and data visualization. The platform enables the integrative analysis of multiple data types to understand disease mechanisms. It integrates molecular and clinical data with patient data and outcomes with patient as the central focus. Increased expression of Ly6 family members was observed in several cancer types such as breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, and it is related with poor outcomes for patient survival using G-DOC and GEO.81

CONCLUSION

This review provides information about biomarkers in breast cancer using databases (Table 1). Most databases offer new comprehensive information on the molecular biology of cancer. The application of updated technology and bioinformatics tools contributes to identification and differentiation of molecules and genome structures, expression levels, and responses to drugs in cancers. Most of the databases provided large volumes of information to researchers without any limitations. The researchers have used the databases to develop candidate breast cancer biomarkers, drug and therapeutic targets, to analyze overall survival and recurrence-free survival and to understand cancer genetic and epigenetic profiles. The targets identified through analysis of the databases undergo clinical trials, and are subsequently used of treatment, prognosis and breast cancer prevention, leading to improvements in personal therapy. In this review, we summarized several databases that are utilized for curing breast cancer patients in various clinical settings, which would be beneficial to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

Table 1.

Classification of biomarkers and their functions by utilizing databases

| Database | Biomarkers | Functions | References No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | LIC00657, FGF14-AS2 | Growth, proliferation | 7, 8 |

| PIWIL3, PIWIL4 | Related with overall survival, recurrence-free survival | 9 | |

| miR-574-3p, miR-660-5p | Related with overall survival, recurrence-free survival | 10 | |

| miR-10b, miR-26a, miR-146a, miR-153 | Regulation BRCA1 expression in triple negative breast cancer | 11 | |

| DNA methylation | High expression in breast cancer | 12–14 | |

| RNA-protein complex (MSI2, TTP) | Related with clinical outcome | 15, 16 | |

| PD-L1 | Increased the antitumor adaptive immune response | 17 | |

| pSTS3, KLK10 | Association with trastuzumab-resistance in breast cancer | 18, 19 | |

| Genome Expression Omnibus (GEO) | U79277, AK024118, BC040204, Ak000974 | Metastasis, breast cancer pathogenesis | 24, 25 |

| miR-105, miR126/miR-126(*) | Metastasis | 26, 27 | |

| Pea3, WNT5A/B | EMT | 29, 30 | |

| HER2Δ16 | Resistance-tamoxifen and trastzumab | 32 | |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) | ER, PR, HER2-neu | Development, invasion, metastasis, worse survival | 42 |

| DNA damage repair protein (KU70/80) | High expression of BRCA-1 proficient cell line | 49 | |

| Ki-67 | Proliferation | 50 | |

| eIF4E | Metastasis | 51 | |

| Embase | HER2 | Metastasis | 53 |

| COX-2 | Expression in invasive breast cancer | 54 | |

| Survivin | Overexpression in breast cancer | 59, 60 | |

| EZH2 | High expression of p53 | 61 | |

| APC | Low expression in early-stage breast cancer patients | 62 | |

| miR-21, miR-155 | Over expression in breast cancer | 63–68 | |

| Bmi-1 | High expression in Caucasian patients | 69 | |

| Ovid | MMP-9 | Invasion, metastasis | 72 |

| SK1 | Cancer genesis, progression, metastasis | 73 | |

| NGAL | Proliferation, survival, morphogenesis | 74 | |

| DcR3 | Tumorigenesis, progression | 75 | |

| Gene Expression-Based Outcome (GOBO) | MKl1 | Progression, migration | 77 |

| FLI1 | Aggressive phenotype in breast cancer | 79 | |

| Small Molecule-miRNA Network-Based Inference (SMiR-NBI) | 11 onco-miRNAs | Up-regulated in MDA-MB-231 | 80 |

| Georgetown Database of Cancer (G-DOC) | Ly6 family members | Poor outcome | 81 |

FGF14-AS2, FGF 14 antisense RNA2; MSI2, Musashi RNA-binding protein 2; TTP, Tristetraprolin; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; Pea3, polyomavirus enhancer activator 3 protein; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, HER2-neu; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homologue 2; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; Bmi, B-cell-specific moloney leukemia virus insertion site; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; SK1, sphingosine kinase 1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; DcR3, Decoy receptor 3; Mkl1, megakaryoblastic leukemia-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present study was supported by the Duksung Women’s University Research Grant 2015.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong M, Park N, Chun YJ. Role of annexin a5 on mitochondria-dependent apoptosis induced by tetramethoxystilbene in human breast cancer cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2014;22:519–24. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung J. Human tumor xenograft models for preclinical assessment of anticancer drug development. Toxicol Res. 2014;30:1–5. doi: 10.5487/TR.2014.30.1.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko EY, Moon A. Natural products for chemoprevention of breast cancer. J Cancer Prev. 2015;20:223–31. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2015.20.4.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DE, Kim Y, Cho DH, Jeong SY, Kim SB, Suh N, et al. Raloxifene induces autophagy-dependent cell death in breast cancer cells via the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Cells. 2015;38:138–44. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malati T. Tumour markers: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2007;22:17–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02913308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, Li J, Koirala P, Ding X, Chen B, Wang Y, et al. Long non-coding RNAs as prognostic markers in human breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:20584–96. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang F, Liu YH, Dong SY, Ma RM, Bhandari A, Zhang XH, et al. A novel long non-coding RNA FGF14-AS2 is correlated with progression and prognosis in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;470:479–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan P, Ghosh S, Graham K, Mackey JR, Kovalchuk O, Damaraju S. Piwi-interacting RNAs and PIWI genes as novel prognostic markers for breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37944–56. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan P, Ghosh S, Wang B, Li D, Narasimhan A, Berendt R, et al. Next generation sequencing profiling identifies miR-574-3p and miR-660-5p as potential novel prognostic markers for breast cancer. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:735. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fkih M’hamed I, Privat M, Ponelle F, Penault-Llorca F, Kenani A, Bignon YJ. Identification of miR-10b, miR-26a, miR-146a and miR-153 as potential triple-negative breast cancer biomarkers. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2015;38:433–42. doi: 10.1007/s13402-015-0239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benevolenskaya EV, Islam AB, Ahsan H, Kibriya MG, Jasmine F, Wolff B, et al. DNA methylation and hormone receptor status in breast cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:17. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0184-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sizemore ST, Sizemore GM, Booth CN, Thompson CL, Silverman P, Bebek G, et al. Hypomethylation of the MMP7 promoter and increased expression of MMP7 distinguishes the basal-like breast cancer subtype from other triple-negative tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:25–40. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2989-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway K, Edmiston SN, Tse CK, Bryant C, Kuan PF, Hair BY, et al. Racial variation in breast tumor promoter methylation in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:921–30. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang MH, Jeong KJ, Kim WY, Lee HJ, Gong G, Suh N, et al. Musashi RNA-binding protein 2 regulates estrogen receptor 1 function in breast cancer [published online ahead of print September 5, 2016] Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallahi M, Amelio AL, Cleveland JL, Rounbehler RJ. CREB targets define the gene expression signature of malignancies having reduced levels of the tumor suppressor tristetraprolin. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittendorf EA, Philips AV, Meric-Bernstam F, Qiao N, Wu Y, Harrington S, et al. PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:361–70. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonnenblick A, Brohée S, Fumagalli D, Vincent D, Venet D, Ignatiadis M, et al. Constitutive phosphorylated STAT3-associated gene signature is predictive for trastuzumab resistance in primary HER2-positive breast cancer. BMC Med. 2015;13:177. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0416-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Ruan B, Jin Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhu L, et al. Identification of KLK10 as a therapeutic target to reverse trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer [published online ahead of print November 4, 2016] Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19:A68–77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Nayak S, Jankowitz R, Davidson NE, Oesterreich S. Epigenetics in breast cancer: what’s new? Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:225. doi: 10.1186/bcr2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [Accessed November 30, 2016];Program overview [Internet] https://cancergenome.nih.gov/abouttcga/overview.

- 23.Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [Accessed November 30, 2016];The NCBI Handbook [Internet] (2nd ed). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK159736/

- 24.Meng J, Li P, Zhang Q, Yang Z, Fu S. A four-long non-coding RNA signature in predicting breast cancer survival. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:84. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun J, Chen X, Wang Z, Guo M, Shi H, Wang X, et al. A potential prognostic long non-coding RNA signature to predict metastasis-free survival of breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16553. doi: 10.1038/srep16553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Yang P, Sun T, Li D, Xu X, Rui Y, et al. miR-126 and miR-126* repress recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and inflammatory monocytes to inhibit breast cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:284–94. doi: 10.1038/ncb2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou W, Fong MY, Min Y, Somlo G, Liu L, Palomares MR, et al. Cancer-secreted miR-105 destroys vascular endothelial barriers to promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:501–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang M, Zhang S, Wen Y, Wang Y, Wei Y, Liu H, et al. DNA Methylation patterns can estimate nonequivalent outcomes of breast cancer with the same receptor subtypes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen HF, Chan YK, Grills C, McCrudden CM, Gunasekharan V, Shi Z, et al. Polyomavirus enhancer activator 3 protein promotes breast cancer metastatic progression through Snail-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Pathol. 2011;224:78–89. doi: 10.1002/path.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klemm F, Bleckmann A, Siam L, Chuang HN, Rietkötter E, Behme D, et al. β-catenin-independent WNT signaling in basal-like breast cancer and brain metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:434–42. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhuo WL, Zhang L, Xie QC, Zhu B, Chen ZT. Identifying differentially expressed genes and screening small molecule drugs for lapatinib-resistance of breast cancer by a bioinformatics strategy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:10847–53. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.24.10847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huynh FC, Jones FE. MicroRNA-7 inhibits multiple oncogenic pathways to suppress HER2Δ16 mediated breast tumorigenesis and reverse trastuzumab resistance. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Tian P, Zhang J, Kou C. The clinical and prognostic significance of midkine in breast cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9789–94. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dazhi W, Mengxi Z, Fufeng C, Meixing Y. Elevated expression of thyroid hormone receptor-interacting protein 13 drives tumorigenesis and affects clinical outcome. Biomark Med. 2017;11:19–31. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng L, Xu Y, Xu C, Zhang W. Biomarker discovery to improve prediction of breast cancer survival: using gene expression profiling, meta-analysis, and tissue validation. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6177–85. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S113855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H, Tian Y, Yuan X, Liu Y, Wu H, Liu Q, et al. Enrichment of CD44 in basal-type breast cancer correlates with EMT, cancer stem cell gene profile, and prognosis. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:431–44. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S97192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett T, Edgar R. Mining microarray data at NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Methods Mol Biol. 2006;338:175–90. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-097-9:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett T, Edgar R. Gene expression omnibus: microarray data storage, submission, retrieval, and analysis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:352–69. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) [Accessed November 30, 2016];Overview of the SEER Program [Internet] https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html.

- 41.Feuer EJ, Rabin BA, Zou Z, Wang Z, Xiong X, Ellis JL, et al. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results cancer survival calculator SEER*CSC: validation in a managed care setting. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:265–74. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saltzman BS, Malone KE, McDougall JA, Daling JR, Li CI. Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2-neu expression in first primary breast cancers and risk of second primary contralateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:849–55. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters KM, Edwards SL, Nair SS, French JD, Bailey PJ, Salkield K, et al. Androgen receptor expression predicts breast cancer survival: the role of genetic and epigenetic events. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul Wright G, Davis AT, Koehler TJ, Melnik MK, Chung MH. Hormone receptor status does not affect prognosis in metaplastic breast cancer: a population-based analysis with comparison to infiltrating ductal and lobular carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3497–503. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hensley Alford S, Schwartz K, Soliman A, Johnson CC, Gruber SB, Merajver SD. Breast cancer characteristics at diagnosis and survival among Arab-American women compared to European- and African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:339–46. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9999-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cappellani A, Di Vita M, Zanghì A, Cavallaro A, Piccolo G, Majorana M, et al. Prognostic factors in elderly patients with breast cancer. BMC Surg. 2013;13( Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsey SD, Henry NL, Gralow JR, Mirick DK, Barlow W, Etzioni R, et al. Tumor marker usage and medical care costs among older early-stage breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:149–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calip GS, Law EH, Ko NY. Racial and ethnic differences in risk of second primary cancers among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151:687–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3439-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alshareeda AT, Negm OH, Albarakati N, Green AR, Nolan C, Sultana R, et al. Clinicopathological significance of KU70/KU80, a key DNA damage repair protein in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:301–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santisteban M, Reynolds C, Barr Fritcher EG, Frost MH, Vierkant RA, Anderson SS, et al. Ki67: a time-varying biomarker of risk of breast cancer in atypical hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:431–7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin X, Kim RH, Sun G, Miller JK, Li BD. Overexpression of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E is correlated with increased risk for systemic dissemination in node-positive breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Laurentiis M, Arpino G, Massarelli E, Ruggiero A, Carlomagno C, Ciardiello F, et al. A meta-analysis on the interaction between HER-2 expression and response to endocrine treatment in advanced breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4741–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu J, Qiu K, Zhu J, Li J, Lin Y, He Z, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for the incidence and risk of treatment-related mortality in patients with breast cancer treated with HER2 blockade. Breast. 2015;24:699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glover JA, Hughes CM, Cantwell MM, Murray LJ. A systematic review to establish the frequency of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in normal breast epithelium, ductal carcinoma in situ, microinvasive carcinoma of the breast and invasive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:13–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan PS, Haaland B, Montero AJ, Lopes G. A meta-analysis of anastrozole in combination with fulvestrant in the first line treatment of hormone receptor positive advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:961–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao L, Yao GY, Liu MF, Chen LJ, Hu XL, Ye CS. Neoadjuvant bevacizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone to treat non-metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fang Y, Qu X, Cheng B, Chen Y, Wang Z, Chen F, et al. The efficacy and safety of bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy in treatment of HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis based on published phase III trials. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1933–41. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Q, Yan H, Zhao P, Yang Y, Cao B. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for managing metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15746. doi: 10.1038/srep15746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song J, Su H, Zhou YY, Guo LL. Prognostic value of survivin expression in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2053–62. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y, Ma X, Wu X, Liu X, Liu L. Prognostic significance of survivin in breast cancer: meta-analysis. Breast J. 2014;20:514–24. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang T, Wang Y, Zhou F, Gao G, Ren S, Zhou C. Prognostic value of high EZH2 expression in patients with different types of cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4584–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou D, Tang W, Wang W, Pan X, An HX, Zhang Y. Association between aberrant APC promoter methylation and breast cancer pathogenesis: a meta-analysis of 35 observational studies. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2203. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan F, Mao H, Deng L, Li G, Geng P. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of microRNA-21 overexpression in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5622–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen L, Wan Z, Ma Y, Wu L, Liu F, Zang H, et al. The clinical utility of microRNA-21 as novel biomarker for diagnosing human cancers. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1993–2005. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2806-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang Y, Zhou X, Ji J, Chen L, Cao J, Luo J, et al. High expression levels of miR-21 and miR-210 predict unfavorable survival in breast cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biol Markers. 2015;30:e347–58. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y, Zhang Y, Pan C, Ma F, Zhang S. Prediction of poor prognosis in breast cancer patients based on microRNA-21 expression: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li S, Yang X, Yang J, Zhen J, Zhang D. Serum microRNA-21 as a potential diagnostic biomarker for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s10238-014-0332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeng H, Fang C, Nam S, Cai Q, Long X. The clinicopathological significance of microRNA-155 in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:724209. doi: 10.1155/2014/724209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shao Y, Geng Y, Gu W, Ning Z, Jiang J, Pei H. Prognostic role of high Bmi-1 expression in Asian and Caucasian patients with solid tumors: a meta-analysis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68:969–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ovid. [Accessed November 30, 2016];Databases on Ovid. http://www.ovid.com/site/catalog/databases/index.jsp.

- 71.Guo H, Wei B, Zhang HY, Liu GJ, Bu H, Lang ZQ, et al. HER2 expression and its prognostic implication in lymph node negative breast carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2005;34:140–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Song J, Su H, Zhou YY, Guo LL. Prognostic value of matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1615–21. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.3.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wan Z, Liu S, Cao Y, Zeng Z. Sphingosine kinase 1 and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Y, Zeng T. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin protein as a biomarker in the diagnosis of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:479–83. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang M, Lin X, He R, Lin X, Liang L, Tang R, et al. Decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) as a biomarker of tumor deterioration in female reproductive cancers: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:1850–7. doi: 10.12659/MSM.896226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ringnér M, Fredlund E, Häkkinen J, Borg Å, Staaf J. GOBO: gene expression-based outcome for breast cancer online. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gurbuz I, Ferralli J, Roloff T, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Asparuhova MB. SAP domain-dependent Mkl1 signaling stimulates proliferation and cell migration by induction of a distinct gene set indicative of poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee CH, Kuo WH, Lin CC, Oyang YJ, Huang HC, Juan HF. MicroRNA-regulated protein-protein interaction networks and their functions in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:11560–606. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scheiber MN, Watson PM, Rumboldt T, Stanley C, Wilson RC, Findlay VJ, et al. FLI1 expression is correlated with breast cancer cellular growth, migration, and invasion and altered gene expression. Neoplasia. 2014;16:801–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li J, Lei K, Wu Z, Li W, Liu G, Liu J, et al. Network-based identification of microRNAs as potential pharmacogenomic biomarkers for anticancer drugs. Oncotarget. 2016;7:45584–45596. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luo L, McGarvey P, Madhavan S, Kumar R, Gusev Y, Upadhyay G. Distinct lymphocyte antigens 6 (Ly6) family members Ly6D, Ly6E, Ly6K and Ly6H drive tumorigenesis and clinical outcome. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11165–93. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]