Abstract

Background

The endometrium prepares for implantation under the control of steroid hormones. It has been suggested that there are complicated interactions between the epithelium and stroma in the endometrium during menstrual cycle. In this study, we demonstrate a difference in gene expression between the epithelial and stromal areas of the secretory human endometrium using microdissection and macroarray technique.

Methods

The epithelial and stromal areas were microdissected from the human endometrium during the secretory phase. RNA was extracted and amplified by PCR. Macroarray analysis of nearly 1000 human genes was carried out in this study. Some genes identified by macroarray analysis were verified using real-time PCR.

Results

In this study, changes in expression <2.5-fold in three samples were excluded. A total of 28 genes displayed changes in expression from array data. Fifteen genes were strongly expressed in the epithelial areas, while 13 genes were strongly expressed in the stromal areas. The strongly expressed genes in the epithelial areas with a changes >5-fold were WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 (44.1 fold), matrix metalloproteinase 7 (40.1 fold), homeo box B5 (19.8 fold), msh homeo box homolog (18.8 fold), homeo box B7 (12.7 fold) and protein kinase C, theta (6.4 fold). On the other hand, decorin (55.6 fold), discoidin domain receptor member 2 (17.3 fold), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (9 fold), ribosomal protein S3A (6.3 fold), and tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor homology domains (5.2 fold) were strongly expressed in the stromal areas. WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 (19.4 fold), matrix metalloproteinase 7 (9.7-fold), decorin (16.3-fold) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (7.2-fold) were verified by real-time PCR.

Conclusions

Some of the genes we identified with differential expression are related to the immune system. These results are telling us the new information for understanding the secretory human endometrium.

Introduction

Many studies have sought to understand the mechanism of implantation. Recently, the rate of pregnancy in the in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) cycle has declined, and this has been attributed to a decrease in the rate of implantation.

The recently developed laser microdissection method has gained widespread use throughout the research field. Information about cells can be determined without contamination by using this method. Moreover, with the macroarray technique, which was already widely used for this purpose, the profiling of the gene expression of specific cells types has become possible. Torres et al. have already reported differences in gene expression between cell types or regions within the monkey endometrium using laser microdissection and differential display [1,2].

Identification of cell-specific proteins, which are expressed in the endometrium during the secretory phase, has been performed using a multi-disciplinary approach in the same trial. IGF-II mRNA is expressed in the mid-to-late secretory phase and in early pregnancy [3]. During decidualization, interstitial collagen in the mouse endometrium increases [4]. Collagen IV and laminin reactivity increased in the basal lamina and underlying subepithelial stroma as pregnancy proceeds [5]. The most abundant expression of IL-15 mRNA during the menstrual cycle is observed in the midsecretory phase [6]. Leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) is known as an indispensable factor for implantation and is expressed in the glandular epithelium at the time of implantation in human endometrium [7-9].

In this study, we demonstrate differential in gene expression between the epithelial and stromal areas obtained from secretory human endometrium using laser microdissection and the macroarray method. Confirmation of differential expression of candidate genes was performed by real-time PCR.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Human endometrium was obtained from 8 patients (25–38 years old) with normal menstrual cycles (28~30 days) during the mid secretory phase. These patients had had at least one intrauterine pregnancy in the past (3 patients for Microarray analysis, 5 patients for real-time PCR). Part of the endometrial biopsy was obtained with a curetting technique. The day of the menstrual cycle was determined by the patient's history, plasma progesterone levels (9.8~17.3 ng/ml) and the histological criteria of Noyes et al [10]. These patients did not receive any hormonal therapy. Informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in this study. The Institutional Review Boards of Showa University approved the use of human subjects and the procedures.

Methods

Laser Microdissection and RNA extraction

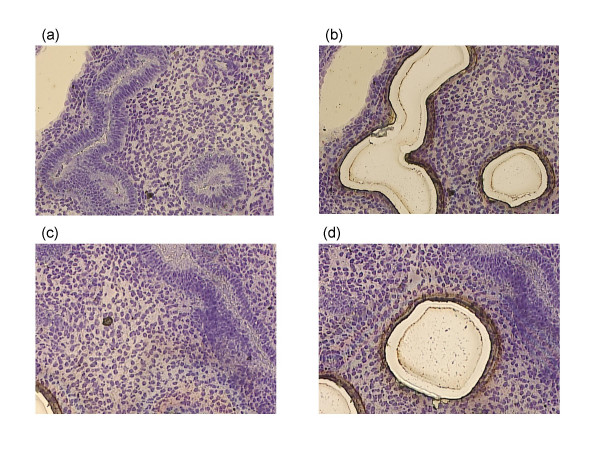

The endometrium was embedded in OCT compound and frozen immediately in isopentane that had been cooled in the liquid nitrogen. This freezing block was sliced by a cryomicrotome at 8 μm thickness. Frozen sections were fixed in 100% methanol for 3 min and stained with 1% toluidine blue. The section was laser-microdissected by the PALM MicroBeam system (PALM Microlaser. Technologies A.G.) for epithelial and stromal areas and collected in a small tube (Fig 1a,1b,1c,1d). Approximately 30–50 sections were laser-microdissected. Contamination with non-target components was monitored morphologically. Total RNA was extracted from the tissue section using the acid guanidinium-phenol-chloroform method [11].

Figure 1.

Human endometrial epithelial areas (a-b) and stromal areas (c-d) were laser-microdissected. (200×)

Macroarray

The RNAs obtained were synthesized from cDNA using a modified oligo (dT) primer and the BD SMART™ PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). cDNA was PCR amplified for 24–29 cycles according to the user manual. (BD Atlas™ SMART™ Probe amplification Kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA)). 550 ng of cDNA sample was labeled with α-32P dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) using a randam primer. Labeled probes were hybridized to a nylon array (BD Atlas™ Nylon cDNA Expression Arrays, Human 1.2 Array (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA)) in ExpressHyb solution at 68°C overnight. After hybridization, the nylon membrane was washed with 2 × standard saline citrate (SSC) + 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (WAKO Pure Chemical Ltd, Japan) once, twice with 1.0 × SSC + 0.5% SDS at 68°C [12,13]. The membrane was exposed to a phosphor screen (Fujifilm, Japan) for 24 hours and scanned using a STORM 830 Scanner and IMAGEQUANT 4.1-J (Molecular Dynamics). Hybridization signal intensities for individual genes were a subtracted from the background and normalized to the signals for GAPDH and the beta-actin gene, respectively, using AIS (Analytical Imaging Station) Array™ (IMAGING Research INC.). Each normalized a gene expression signal the epithelial and stromal areas was compared, and was automatically calculated as a ratio [14,15]. In this study, a change in expression <2.5-fold in all three samples was excluded.

Real-time PCR

RNA was reverse transcribed using oligo (dT) primers by TaKaRa RNA PCR Kit (AMV) Ver 2.1 (TAKARA BIO INC, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System. TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix and Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression probes (Applied Biosystems) were used for the PCR step (Assay ID for MMP7; Hs00159163 m1, WFDC2; Hs00707910 s1, TIMP1; Hs00171558 m1 Decorin; Hs00370385 m1). Primer sequences are not publicly available, although their validity has been established by the manufacturer. The expression values obtained were normalized against those from the control human GAPDH [16]. Statistical significance was determined by the Wilcoxon test and defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Microdissection and Microarray

Secretory endometrium was collected from 8 patients (3 patients for Microarray, 5 patients for real-time PCR). Each sample was carefully dissected by laser microdissection for epithelial and stromal areas (Fig 1a to 1d).

Total RNA was extracted and subjected to macroarray with nearly 1000 genes on the nylon membrane. Fifteen genes were strongly expressed in the epithelial areas (Table 1), while 13 genes were strongly expressed in the stromal areas (Table 2). Mean values are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Genes strongly expressed in the epithelial areas that increased >5-fold in expression included WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 (WFDC2), matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7), homeo box B5, msh homeo box homolog, homeo box B7 and protein kinase C, theta (PKC theta). On the other hand, decorin, discoidin domain receptor member 2 (DDR2), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), ribosomal protein S3A, and tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor homology domains (Tie1) were strongly expressed in the stromal areas.

Table 1.

Expressed gene list in epithelial areas.

| Ratio | GENE BANK | LOCUS LINK | Gene Name | Classifications |

| 44.1 | X63187 | 10406 | WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 | inhibitors of proteases |

| 40.1 | X07819 | 4316 | matrix metalloproteinase 7 | metalloproteinases |

| 19.8 | M92299 | 3215 | homeo box B5 | CDK inhibitors |

| 18.8 | M97676 | 4487 | msh homeo box homolog 1 (Drosophila) | transcription activators and repressors |

| 12.7 | M16937 | 3217 | homeo box B7 | transcription activators and repressors |

| 6.4 | L07032 | 5588 | protein kinase C, theta | intracellular kinase network members |

| 4.8 | X59798 | 595 | cyclin D1 | cyclins |

| 4.5 | M97796 | 3398 | inhibitor of DNA binding 2, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | transcription activators and repressors |

| 3.9 | X02920 | 5265 | serine proteinase inhibitor, clade A | inhibitors of proteases |

| 3.8 | D14520 | 688 | Kruppel-like factor 5 | basic transcription factors |

| 2.9 | U24166 | 22919 | microtubule-associated protein, RP/EB family, member 1 | adaptors and receptor-associated proteins |

| 2.9 | X67055 | 3699 | pre-alpha (globulin) inhibitor | inhibitors of proteases |

| 2.8 | U26710 | 868 | Cas-Br-M (murine) ectropic retroviral transforming sequence b | adaptors and receptor-associated proteins |

| 2.7 | D45132 | 7799 | PR domain containing 2, with ZNF domain | transcription activators and repressors |

| 2.5 | AF059244 | 10047 | cystatin 8 | inhibitors of proteases |

Ratio shows average of 3 samples

Table 2.

Expressed gene list in stromal areas

| Ratio | GENE BANK | LOCUS LINK | Gene Name | Classifications |

| 55.6 | M14219 | 1634 | decorin | cell surface antigens |

| 17.3 | X74764 | 4921 | discoidin domain receptor family, member 2 | intracellular transducers |

| 9 | X03124 | 7076 | tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 | extracellular secreted proteins |

| 6.3 | M77234 | 6189 | ribosomal protein S3A | ribosomal proteins |

| 5.2 | X60957 | 7075 | tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor homology domains | intracellular transducers |

| 4.9 | M57399 | 5764 | pleiotrophin (heparin binding growth factor 8) | growth factors |

| 4.8 | M62424 | 2149 | coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor | intracellular transducers |

| 3.5 | S40706 | 1649 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | other apoptosis-associated proteins |

| 3.3 | M81757 | 6223 | ribosomal protein S19 | other cell cycle proteins |

| 2.8 | J00123 | 5179 | proenkephalin | neuropeptides |

| 2.8 | M15395 | 3689 | integrin, beta 2 | major histocompatibility complex |

| 2.8 | U32944 | 8655 | dynein, cytoplasmic, light polypeptide | other apoptosis-associated proteins |

| 2.6 | D15057 | 1603 | defender against cell death 1 | other apoptosis-associated proteins |

Ratio shows average of 3 samples

Real-time PCR

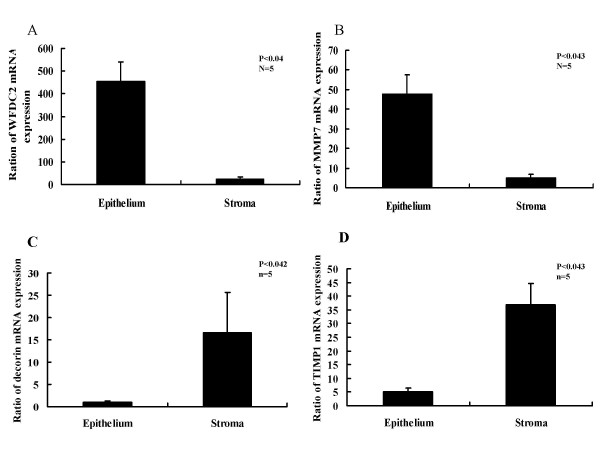

Real-time PCR (Taqman analysis) was used to verify the changes in expression of certain candidate genes that are highly expressed in the array. Five samples were used for this study. WFDC2 and MMP7, which are both strongly expressed in the epithelial areas and decorin and TIMP1, which are both strongly expressed in the stromal areas by the cDNA array were chosen for verification. Each value was corrected for differences in loading relative to GAPDH mRNA expression.

WFDC2 and MMP7 mRNA expression increased by 9.4- and 9.7-fold, respectively, compared to that of stromal cells. Decorin and TIMP1 mRNA expression increased by 16.3-and 7.2-fold, respectively, in stromal cells compared to that of epithelial cells. Statistically significant changes in expression of these genes were observed (p < 0.05) (Fig 2A,2B,2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

A: WFDC2 mRNA expression in the secretory phase of the endometrium was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5). Values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. Epithelial areas WFDC2 mRNA expression is shown relative to that of the stromal areas. The mean change is 19.4-fold. Statistical analysis was carried out using Wilcoxon test. B: MMP7 mRNA expression in the secretory phase of the endometrium was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5). Values are normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. Epithelial areas MMP7 mRNA expression is shown relative to that of the stromal areas. The mean change is 9.7-fold. Statistical analysis was carried out using Wilcoxon test. C: Decorin mRNA expression in the secretory phase of the endometrium was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5). Values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression for each sample. Stromal areas decorin mRNA expression is shown relative to that of the epithelial areas. The mean change is 16.3-fold. Statistical analysis was carried out using Wilcoxon test. D: TIMP1 mRNA expression in the secretory phase of the endometrium was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5). Values are normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression for each sample. Stromal areas TIMP1 mRNA expression is shown relative to that of the epithelial areas. The mean change is 7.2-fold. Statistical analysis was carried out using Wilcoxon test.

Discussion

To date, various methods have been used for understanding the function of the endometrium. It is a well-known fact that epithelial cells and stromal cells in the endometrium play specific roles and are influenced by steroid hormones. However, it is very difficult to understand the molecular composition of each cell type as a function of time during the menstrual cycle. One of the problems of a cell culture experiment is that separation cultivation makes changes the composition of the cells. This is especially true as these cells are influenced by neighboring cells in vivo. It has recently become possible to acquire the information about the cell by the microdissection method.

In this study, laser microdissection was used to isolate epithelial and stromal areas from the human endometrium. RNA was amplified by PCR and global gene expression was demonstrated by cDNA macroarray.

Twenty-eight genes were identified in this study. These constitute only 2.8% of the 1000 genes on the array. Although this seems to be a small number, these genes were expressed at least 2.5-fold greater in all three samples and normalized to two house keeping genes. A similar percentage (1.2–5.8%) of genes with differential expression were reported using array analysis [17-19]. However, included genes below the 2.5-fold that we established as a criterion for inclusion in this study should be considered.

Recently, some papers focused on endometrial gene expression have been reported. However, lots of them were compared between phases in the menstrual cycle. While Okulicz et al. demonstrated a difference in the gene expression between cell compartments in the monkey endometrium, the genes they identified are not the same as ours [1,2]. One of the reasons for this is because they tried to find new genes using differential display RT-PCR.

Fifteen of 1000 genes were strongly expressed in the epithelial areas compared to the stromal areas. Of these, WFDC2 and MMP 7 were strongly expressed in the epithelial areas as confirmed by real-time PCR. WFDC2 was originally described as an epididymis-specific protein is expressed in a number of normal human tissues. A possible role for this gene in sperm maturation is indicated by amino acid similarities to extracellular proteinase inhibitors of genital tract mucous secretions [20]. Although WFDC2 has been recently reported in the secretory endometrium of monkey, this is the first report of its localization in the epithelium of the human endometrium [21]. However, the physiological role of this gene in the endometrium is presently unknown. Baboon endometrial epithelia express MMP 7 was reported by Cox et al [22]. The highest expression of MMP 7 occurred on day 7 of pregnancy in the rat uterus [23,24] and has been reported to have close associations with tumor invasion and metastasis [25,26].

HOXB gene induction is related to the immune system, and is specifically associated with IL-2-induced NK cell proliferation [27,28]. Although Hox-7 is reported to be in human cervical tumor tissue [29], this is the first report or its localization in human endometrium. Msh genes play a role in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion [30]. Friedmann et al. reported that regulated expression of homeobox genes Msx-1 and Msx-2 in mouse mammary gland development suggests a role in hormone action and epithelial-stromal interactions [31]. PKC theta cooperates with Vav1 to induce JNK activity in T-cells [32,33]. Take Catalano et al. report that JNK pathways are altered by RU486 which is an antiprogestins. PKC therefore seems to be important factor for control secretory endometrium [17].

Of the strongly expressed genes in the stromal aeas, decorin and TIMP1 gene expression were verified by real-time PCR. San Martin et al. reported the expression of decorin which is a leucine-rich proteoglycan in the mouse uterine and suggested it localized in the undifferentiated interimplantation site stroma [34]. Some reports also demonstrated its presence in the human uterin cervix and myometrium, but not in human endometrium [35,36]. DDR2 is a new type of receptor tyrosine kinases, and is thought to be involved in the metastasis of some tumors. Its ligand is fibrillar collagen, which suggests a role in controlling celluar responses to the extracellular matrix [37]. The changes in the extracellular matrix may play an important role in implantation, in invasion of trophoblastic cells and in the maintenance of pregnancy [38]. Decidualized stromal cells stained strongly positive for TIMP-1 [39]. Matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors, tissue-specific inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases, play key roles in the cyclic remodeling events that occur in the human endometrium in preparation for pregnancy [40]. Ribosomal protein S3A is through direct or indirect actions on B and T cells and cytokine secretion, could participate in the immunoregulatory processes that play a role in the balance of the Th1 and Th2 immune response [41]. It has been recently said that the ratio of Th1 to Th2 influences pregnancy. Ribosomal protein S3A may be an interesting factor for stromal cell research. In this study, these results show the fact that many of the genes, which are related to the immune system, are expressed in the endometrium during the mid secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. This time, however, differences in gene expression between cell compartments of the endometrium were considered. Interactions among cells are key factors in understanding endometrial function.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Takumi Yanaihara, Professor Emeritus of Showa University, Tokyo, Japan for advice. We also wish to thank Miss. Momoko Negishi Miss. Kaori Mitukawa and Mr. Hiroshi Chiba for their technical assistance.This study was supported by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants.

Contributor Information

Atsushi Yanaihara, Email: atsushi-y@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Yukiko Otsuka, Email: yukiccccc@yahoo.co.jp.

Shinji Iwasaki, Email: shinji-i@gb3.so-net.ne.jp.

Keiko Koide, Email: atsushi-y@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Tadateru Aida, Email: aida@dent.showa-u.ac.jp.

Takashi Okai, Email: okai.t@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

References

- Torres MS, Ace CI, Okulicz WC. Assessment and application of laser microdissection for analysis of gene expression in the rhesus monkey endometrium. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:1067–1072. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okulicz WC, Ace CI, Torres MS. Gene expression in the rhesus monkey endometrium: differential display and laser capture microdissection. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d551–8. doi: 10.2741/1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice LC, Dsupin BA, Jin IH, Vu TH, Hoffman AR. Differential expression of messenger ribonucleic acids encoding insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in human uterine endometrium and decidua. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1115–1122. doi: 10.1210/jc.76.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro WR, Witzel SS, Velosa AP, Shimokomaki M, Abrahamsohn PA, Zorn TM. Increase of interstitial collagen in the mouse endometrium during decidualization. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre DM, Lim HC, Ryan K, Kimmins S, Small JA, MacLaren LA. Implantation-associated changes in bovine uterine expression of integrins and extracellular matrix. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1430–1436. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.5.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Okada H, Sanezumi M, Nakajima T, Yasuda K, Kanzaki H. Expression of interleukin-15 in human endometrium and decidua. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:75–80. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K, Kanzaki H, Iwai M, Hatayama H, Fujimoto M, Narukawa S, Higuchi T, Kaneko Y, Mori T, Fujita J. Expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) receptor in human placenta: a possible role for LIF in the growth and differentiation of trophoblasts. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM, Fenwick P, Smith SK. Leukaemia inhibitory factor mRNA concentration peaks in human endometrium at the time of implantation and the blastocyst contains mRNA for the receptor at this time. J Reprod Fertil. 1994;101:421–426. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1010421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanova L, Stavreus-Evers A, Nikas Y, Hovatta O, Landgren BM. Coexpression of pinopodes and leukemia inhibitory factor, as well as its receptor, in human endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2003;79 Suppl 1:808–814. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrial biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122:262–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Hatori M, Kinugasa Y, Irie T, Tachikawa T, Nagumo M. Comparison of the expression profile of metastasis-associated genes between primary and circulating cancer cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:1425–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M, Shalon D, Heller R, Chai A, Brown PO, Davis RW. Parallel human genome analysis: microarray-based expression monitoring of 1000 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10614–10619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endege WO, Steinmann KE, Boardman LA, Thibodeau SN, Schlegel R. Representative cDNA libraries and their utility in gene expression profiling. Biotechniques. 1999;26:542–8, 550. doi: 10.2144/99263cr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking C, Takemoto R, Schaider H, Showe L, Satyamoorthy K, Robbins P, Herlyn M. Transforming growth factor-beta1 increases survival of human melanoma through stroma remodeling. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8306–8316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehle MM, Bennett AF, Long AD. Genetic architecture of thermal adaptation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:525–530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021448998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett JN, Sanoudou D, Kho AT, Bennett RR, Greenberg SA, Kohane IS, Beggs AH, Kunkel LM. Gene expression comparison of biopsies from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and normal skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15000–15005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192571199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RD, Yanaihara A, Evans AL, Rocha D, Prentice A, Saidi S, Print CG, Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM, Smith SK. The effect of RU486 on the gene expression profile in an endometrial explant model. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:465–473. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DD, Lagow E, Thathiah A, Al-Shami R, Farach-Carson MC, Vernon M, Yuan L, Fritz MA, Lessey B. Changes in gene expression during the early to mid-luteal (receptive phase) transition in human endometrium detected by high-density microarray screening. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:871–879. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.9.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao LC, Tulac S, Lobo S, Imani B, Yang JP, Germeyer A, Osteen K, Taylor RN, Lessey BA, Giudice LC. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2119–2138. doi: 10.1210/en.143.6.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingle L, Singleton V, Bingle CD. The putative ovarian tumour marker gene HE4 (WFDC2), is expressed in normal tissues and undergoes complex alternative splicing to yield multiple protein isoforms. Oncogene. 2002;21:2768–2773. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ace CI, Okulicz WC. Microarray profiling of progesterone-regulated endometrial genes during the rhesus monkey secretory phase. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox KE, Sharpe-Timms KL, Kamiya N, Saraf M, Donnelly KM, Fazleabas AT. Differential regulation of stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3) and matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) in baboon endometrium. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2000;7:242–248. doi: 10.1016/S1071-5576(00)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtman MP, Zhang J, Salamonsen LA. Effect of inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases on endometrial decidualization and implantation in mated rats. J Reprod Fertil. 1999;117:169–177. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1170169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Woessner J. F., Jr., Zhu C. Matrilysin activity in the rat uterus during the oestrous cycle and implantation. J Reprod Fertil. 1998;114:347–350. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1140347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanioka Y, Yoshida T, Yagawa T, Saiki Y, Takeo S, Harada T, Okazawa T, Yanai H, Okita K. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 are associated with unfavourable prognosis in superficial oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2116–2121. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huachuan Z, Xiaohan L, Jinmin S, Qian C, Yan X, Yinchang Z. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 involving in growth, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of gastric cancer. Chin Med Sci J. 2003;18:80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta MT, Petrini M, Tritarelli E, Samoggia P, Care A, Bottero L, Testa U, Peschle C. HOXB cluster genes in activated natural killer lymphocytes: expression from 3'-->5' cluster side and proliferative function. J Immunol. 1996;157:2462–2469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care A, Testa U, Bassani A, Tritarelli E, Montesoro E, Samoggia P, Cianetti L, Peschle C. Coordinate expression and proliferative role of HOXB genes in activated adult T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4872–4877. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim C, Zhang W, Rhee CH, Lee JH. Profiling of differentially expressed genes in human primary cervical cancer by complementary DNA expression array. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:3045–3050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincecum JM, Fannon A, Song K, Wang Y, Sassoon DA. Msh homeobox genes regulate cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and cell-cell sorting. J Cell Biochem. 1998;70:22–28. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19980701)70:1<22::AID-JCB3>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann Y, Daniel CW. Regulated expression of homeobox genes Msx-1 and Msx-2 in mouse mammary gland development suggests a role in hormone action and epithelial-stromal interactions. Dev Biol. 1996;177:347–355. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller A, Dienz O, Hehner SP, Droge W, Schmitz ML. Protein kinase C theta cooperates with Vav1 to induce JNK activity in T-cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20022–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakov N, Altman A. Protein kinase C(theta) in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:761–794. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin S, Soto-Suazo M, De Oliveira SF, Aplin JD, Abrahamsohn P, Zorn TM. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) in uterine tissues during pregnancy in mice. Reproduction. 2003;125:585–595. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berto AG, Sampaio LO, Franco CR, Cesar R. M., Jr., Michelacci YM. A comparative analysis of structure and spatial distribution of decorin in human leiomyoma and normal myometrium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619:98–112. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludmir J, Sehdev HM. Anatomy and physiology of the uterine cervix. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:433–439. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel W, Gish GD, Alves F, Pawson T. The discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by collagen. Mol Cell. 1997;1:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi M, Muragaki Y, Ooshima A, Yamoto M, Nakano R. Alterations in distribution and composition of the extracellular matrix during decidualization of the human endometrium. J Reprod Fertil. 1996;108:147–155. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Salamonsen LA. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1, -2 and -3 in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:735–741. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.9.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CS, Tai CJ, MacCalman CD, Leung PC. Dose-dependent effects of gonadotropin releasing hormone on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and MMP-9 and tissue specific inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 messenger ribonucleic acid levels in human decidual Stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:680–688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro-Da-Silva A, Borges MC, Guilvard E, Ouaissi A. Dual role of the Leishmania major ribosomal protein S3a homologue in regulation of T- and B-cell activation. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6588–6596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6588-6596.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]