Abstract

Enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EHEC and EPEC, respectively) strains are closely related human pathogens that are responsible for food-borne epidemics in many countries. Integration host factor (IHF) and the locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded regulator (Ler) are needed for the expression of virulence genes in EHEC and EPEC, including the elicitation of actin rearrangements for attaching and effacing lesions. We applied a proteomic approach, using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in combination with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and a protein database search, to analyze the extracellular protein profiles of EHEC EDL933, EPEC E2348/69, and their ihf and ler mutants. Fifty-nine major protein spots from the extracellular proteomes were identified, including six proteins of unknown function. Twenty-six of them were conserved between EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, while some of them were strain-specific proteins. Four common extracellular proteins (EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir) were regulated by both IHF and Ler in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69. TagA in EHEC EDL933 and EspC and EspF in EPEC E2348/69 were present in the wild-type strains but absent from their respective ler and ihf mutants, while FliC was overexpressed in the ihf mutant of EPEC E2348/69. Two dominant forms of EspB were found in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, but the significance of this is unknown. These results show that proteomics is a powerful platform technology for accelerating the understanding of EPEC and EHEC pathogenesis and identifying markers for laboratory diagnoses of these pathogens.

Enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EHEC and EPEC, respectively) strains are closely related human pathogens (7). EHEC strains, especially those of serotype O157:H7, which produce Shiga-like toxin (Stx), are a common cause of diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and hemolytic uremic syndrome, while EPEC is the most common bacterial cause of infant diarrhea (29). Both have been implicated in food-borne outbreaks in many countries and cause diarrhea by colonizing the intestinal mucosa (29, 30). EHEC and EPEC strains are distinguished from other pathogenic E. coli strains by their ability to produce a characteristic histopathological feature known as attaching and effacing (AE) lesions on the mucosa (12, 29). AE lesions are characterized by the destruction of the microvilli and the induction of actin-based pedestal formation underneath the eukaryotic membrane at the site of attachment (6). EHEC and EPEC secrete many extracellular proteins (ECPs), and the type III secretion system (TTSS) is a major secretion apparatus for secreting virulence factors which interact directly with the host (20, 25). The TTSS is located within a chromosomal pathogenicity island designated the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) which is necessary for the formation of AE lesions (18, 19). The LEE-encoded regulator (Ler) activates most of the genes within the LEE region and is central to the process of AE lesion formation (26). Integration host factor (IHF) is a histone-like protein which can bind to specific DNA consensus sites and bend the DNA to form a nucleoprotein complex (28, 34). IHF is involved in a wide variety of cellular processes, including directly activating expression of the ler transcriptional unit, and Ler in turn mediates the expression of the other LEE genes (13, 14). The expression of both IHF and Ler is needed to elicit the actin rearrangement associated with AE lesions.

Proteomics offers a powerful platform technology for the study of protein expression and identification. It is a useful tool for analyses of the disease process and of bacterium-host interactions at the protein level. The DNA sequences of two EHEC genomes were determined recently (15, 32), and the EPEC genome sequence will be completed soon (see the Sanger Institute web site for details [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/Microbes]). Therefore, EHEC and EPEC are ideal organisms for proteomic analysis.

For this study, we used a proteomic approach to analyze the extracellular proteomes of EHEC and EPEC in order to give further insight into the pathogenesis and divergence of these two emerging pathogens. A comparative proteomic analysis among the wild-type strains and the ler and ihf mutants revealed an integrated view of ECPs of EHEC and EPEC and also identified various virulence factors that are regulated by IHF and Ler. These proteomes are useful references for comparative analysis, laboratory diagnosis, and further molecular and functional studies, which will lead to a better understanding of EHEC and EPEC pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The wild-type strains of EHEC and EPEC and the mutants that were used for this study are listed in Table 1. EHEC ler and ihf mutants were constructed with the Lambda Rad system as described earlier (13, 44). E. coli strains were routinely cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth without shaking. When required, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used for this study

Protein isolation and assay.

For the preparation of ECPs of EHEC and EPEC, overnight cultures in Luria-Bertani broth were diluted 1:50 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and were incubated for 9 and 6 h, respectively, at 37°C in a 5% (vol/vol) CO2 atmosphere. Bacterial cells were removed from the culture by centrifugation (5,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size small-protein binding filter (Millex; Millipore). The ECP fraction was isolated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation (38), and the protein pellet was washed thrice with −20°C acetone and then air dried. The protein pellet was solubilized in ReadyPrep reagent 3 (5 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% [wt/vol] CHAPS, 2% [wt/vol] SB 3-10, 40 mM Tris, and 0.2% [wt/vol] Bio-Lyte 3/10 ampholyte; Bio-Rad) and was stored at −20°C until analysis. The protein concentration was determined by use of a Bio-Rad protein assay kit, with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

1- and 2-DE.

ECPs in amounts of 10 to 30 μg that gave similar profiles to those of the background proteins were used to generate the extracellular proteomes of different strains for a comparative analysis. One-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1-DE) was performed according to a standard protocol (36). 2-DE was performed by use of the Ettan IPGphor isoelectric focusing system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Dry gel strips were rehydrated for 12 h at room temperature with a mixture containing 8 M urea, 2% (wt/vol) CHAPS, 0.5% immobilized pH gradient (IPG) buffer, 50 mM dithiothreitol, and a trace amount of bromophenol blue. For the first dimension, the ECP samples were separated on 18-cm-long rehydrated Immobiline DryStrips with a nonlinear gradient from pH 3 to 10 (Amersham) by use of a cup-loading system and were focused at 500 V for 1.5 h, 4,000 V for 2 h, and 8,000 V for 40,000 Vh. After isoelectric focusing, the IPG strips were reduced, alkylated, and exchanged with detergent. 2-DE was carried out in sodium dodecyl sulfate-12.5% polyacrylamide gels (20 by 20 cm), and the proteins were visualized by silver staining. Computer-assisted gel analysis with PD-QUEST, version 7.1.0 (Bio-Rad), was performed on images captured with a Molecular Dynamics personal densitometer (Bio-Rad). ECP samples were isolated from at least three independent cultures. More than three separate gels were analyzed for each sample. Protein spots that displayed dominant and consistent patterns were selected for further identification.

Tryptic in-gel digestion and MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

The protein spots of interest were excised from the 2-DE gels and digested with porcine sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) according to a procedure described by Shevchenko and coworkers (37). The extracted peptides were resuspended in 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid and 50% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. The peptide mixture (0.5 μl) was spotted onto a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) target plate simultaneously with 0.5 μl of matrix solution (a saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in 0.1% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid and 50% [vol/vol] acetonitrile). Peptide mass fingerprint maps of tryptic peptides were generated by MALDI-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) with a Voyager DE-STR Biospectrometry work station mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). All of the spectra were obtained in reflectron mode, with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a delayed extraction of 150 ns. Mass calibration was performed with a peptide mixture (angiotensin I) (1,296.6853 [M + H]+) and adrenocorticotropin (18-39 clip) (2,465.1989 [M + H]+) as an external standard. Internal calibration with two peptides arising from trypsin autoproteolysis of 842.51[M + H]+ and 2,211.10 [M + H]+ was performed whenever possible. Peptide masses were searched against the NCBInr database by use of the MS-Fit program (http://prospector.ucsf.edu) and Mascot software (Matrix Science), with the mass tolerance set to 50 ppm (internal calibration) or 200 ppm (external calibration). Proteins with a minimum of four matching peptides and with sequence coverage exceeding 20% with the matched proteins were considered positive.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ECP production.

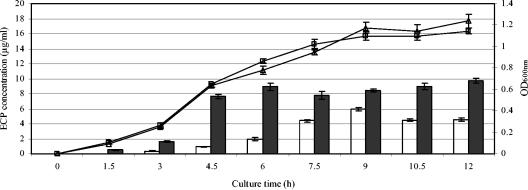

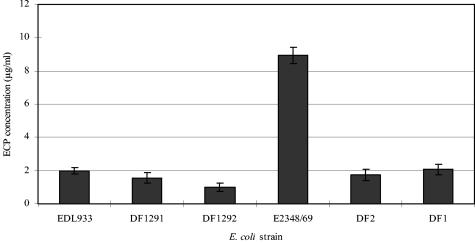

The wild-type strains EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 and their respective ler mutants (DF1291 for EHEC and DF2 for EPEC) and ihf mutants (DF1292 for EHEC and DF1 for EPEC) were grown in DMEM for the production of ECPs. EPEC E2348/69 grew slightly faster during the early log phase and produced larger amounts of ECPs in DMEM than EHEC EDL933 (Fig. 1). The ECP production of the wild-type strains EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 at 6 h was higher than that of their respective ihf and ler mutants (Fig. 2), suggesting that the wild-type strains produced more ECPs in the supernatants. Nine-hour cultures for EHEC strains and 6-h cultures for EPEC strains were used for the optimum production of ECPs for the construction of extracellular proteomes.

FIG. 1.

Growth and protein secretion of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 in DMEM at 37°C with 5% (vol/vol) CO2. The growth of EHEC EDL933 (▵) and EPEC E2348/69 (□) was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). White bars, ECP production of EHEC EDL933; black bars, ECP production of EPEC E2348/69. The results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of ECP production among EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 wild-type strains and their ler mutants (DF1291 for EHEC and DF2 for EPEC) and ihf mutants (DF1292 for EHEC and DF1 for EPEC). EHEC and EPEC strains were cultured in DMEM at 37°C with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 for 6 h. The results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments.

Extracellular proteomes of EHEC and EPEC.

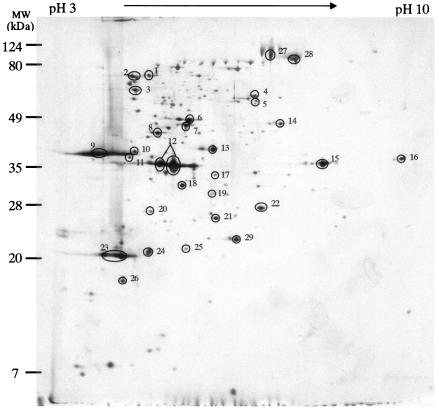

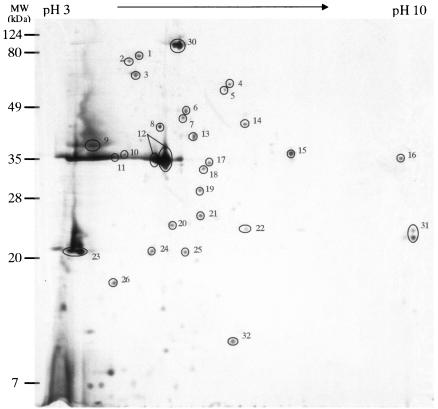

ECPs from EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 were subjected to 2-DE, and consistent and dominant ECP spots were excised for tryptic in-gel digestion, MALDI-TOF MS analysis, and a protein database search. Fifty-nine spots were identified (Tables 2 and 3), which covered most of the prominent proteins. A total of 29 and 30 proteins were identified for EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, respectively (Fig. 3 and 4). Peptide mass fingerprints generated from the EHEC EDL933 protein spots were assigned to the complete genome database of EHEC EDL933 for protein identification. Since the genome sequence of EPEC E2348/69 is not available, peptide mass fingerprints generated from the EPEC E2348/69 protein spots were then compared to a limited library of open reading frames of EPEC E2348/69 and other E. coli genome databases, such as those for EHEC EDL933, K-12, and CFT073 (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Summary of common extracellular proteins of EHEC and EPEC identified by MALDI-TOF MS

| Spot no. (EHEC or EPEC) | Sequence coverage (%) | Protein size (Da)/pI (calculated) | Matched E. coli stain | NCB1 accession no. | Matched protein name in EHEC and other E. coli databases | ler/ihf regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-EHEC | 45 | 58,022.5/5.01 | EDL933 | 15804222 | Translocated intimin receptor Tir | +/+ |

| 1-EPEC | 27 | 56,843.5/5.16 | E2348/69 | 2665524 | +/+ | |

| 2-EHEC | 44 | 69,115.0/4.83 | EDL933 | 15799694 | Hsp70 (DnaK) | −/− |

| 2-EPEC | 39 | 69,115.0/4.83 | EDL933 | 15799694 | −/− | |

| 3-EHEC | 30 | 57,319.6/4.81 | EDL933 | 15804735 | Hsp60 (GroEL) | −/− |

| 3-EPEC | 27 | 57,319.6/4.81 | EDL933 | 15804735 | −/− | |

| 4-EHEC | 31 | 61,046.4/5.95 | EDL933 | 15801469 | Oligopeptide transport periplasmic binding protein | −/− |

| 4-EPEC | 38 | 61,046.4/5.95 | EDL933 | 15801469 | −/− | |

| 5-EHEC | 33 | 60,331.5/6.21 | EDL933 | 15804087 | Dipetide transport periplasmic binding protein | −/− |

| 5-EPEC | 35 | 60,331.5/6.21 | EDL933 | 15804087 | −/− | |

| 6-EHEC | 47 | 45,610.7/5.32 | EDL933 | 15803300 | Enolase | −/− |

| 6-EPEC | 42 | 45,610.7/5.32 | EDL933 | 15803300 | −/− | |

| 7-EHEC | 43 | 43,232.1/5.24 | EDL933 | 15804570 | Protein chain elongation factor EF-Tu | −/− |

| 7-EPEC | 54 | 43,232.1/5.24 | EDL933 | 15804570 | −/− | |

| 8-EHEC | 45 | 41,130.3/5.08 | EDL933 | 15803460 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | −/− |

| 8-EPEC | 20 | 41,118.2/5.08 | K12 | 16130827 | −/− | |

| 9-EHEC | 26 | 39,083.2/5.32 | EDL933 | 15804216 | EspD | +/+ |

| 9-EPEC | 37 | 39,473.4/5.13 | E2348/69 | 1668720 | +/+ | |

| 10-EHEC | 24 | 41,123.6/4.97 | EDL933 | 15801009 | Hypothetical protein | −/− |

| 10-EPEC | 21 | 41,123.6/4.97 | EDL933 | 15801009 | −/− | |

| 11-EHEC | 27 | 38,791.0/5.24 | EDL933 | 15801238 | Spermidine/putrescine periplasmic transport protein | −/− |

| 11-EPEC | 22 | 38,791.0/5.24 | EDL933 | 15801238 | −/− | |

| 12-EHEC | 46 | 32,630.6/5.33 | EDL933 | 15804215 | EspB | +/+ |

| 12-EPEC | 68 | 33,140.8/5.24 | E2348/69 | 1169453 | +/+ | |

| 13-EHEC | 40 | 42,383.9/6.02 | EDL933 | 15803459 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase class II | −/− |

| 13-EPEC | 27 | 42,383.9/6.02 | EDL933 | 15803459 | −/− | |

| 14-EHEC | 21 | 45,344.7/6.03 | EDL933 | 15803076 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | −/− |

| 14-EPEC | 20 | 45,344.7/6.03 | EDL933 | 15803076 | −/− | |

| 15-EHEC | 45 | 35,532.5/6.61 | EDL933 | 15802193 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A | −/− |

| 15-EPEC | 45 | 35,532.5/6.61 | EDL933 | 15802193 | −/− | |

| 16-EHEC | 41 | 38,668.1/9.30 | EDL933 | 15801691 | Putative receptor | −/− |

| 16-EPEC | 39 | 38,686.1/9.30 | EDL933 | 15801691 | −/− | |

| 17-EHEC | 29 | 37,200.8/5.99 | EDL933 | 15800816 | Outer membrane protein 3a | −/− |

| 17-EPEC | 36 | 37,200.8/5.99 | EDL933 | 15800816 | −/− | |

| 18-EHEC | 34 | 36,030.3/5.64 | EDL933 | 15802270 | Putative adhesin | −/− |

| 18-EPEC | 28 | 36,030.3/5.64 | EDL933 | 15802270 | −/− | |

| 19-EHEC | 22 | 34,905.8/5.89 | EDL933 | 15800491 | Unknown protein encoded by prophage CP-933K | −/− |

| 19-EPEC | 26 | 34,905.8/5.89 | EDL933 | 15800491 | −/− | |

| 20-EHEC | 38 | 26,995.0/5.07 | EDL933 | 15802999 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthetase | −/− |

| 20-EPEC | 35 | 26,995.0/5.07 | EDL933 | 15802999 | −/− | |

| 21-EHEC | 50 | 26,971.8/5.64 | EDL933 | 15804508 | Triosephosphate isomerase | −/− |

| 21-EPEC | 32 | 26,971.8/5.64 | EDL933 | 15804508 | −/− | |

| 22-EHEC | 41 | 28,556.4/5.85 | EDL933 | 15800464 | Phosphoglyceromutase 1 | −/− |

| 22-EPEC | 53 | 28,556.4/5.85 | EDL933 | 15800464 | −/− | |

| 23-EHEC | 44 | 20,574.1/4.78 | EDL933 | 15804217 | EspA | +/+ |

| 23-EPEC | 35 | 20,468.9/4.52 | E2348/69 | 1018995 | +/+ | |

| 24-EHEC | 34 | 20,761.4/5.03 | EDL933 | 15800320 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase C22 protein | −/− |

| 24-EPEC | 54 | 20,761.4/5.03 | EDL933 | 15800320 | −/− | |

| 25-EHEC | 51 | 23,104.6/5.95 | EDL933 | 15804445 | Protein disulfide isomerase 1 (thiol-disulfide interchange protein dsbA precursor) | −/− |

| 25-EPEC | 41 | 23,118.6/5.95 | CFT073 | 26250621 | −/− | |

| 26-EHEC | 47 | 18,266.0/4.73 | EDL933 | 15802950 | PTS system, glucose-specific IIA component | −/− |

| 26-EPEC | 33 | 18,266.0/4.73 | EDL933 | 15802950 | −/− |

TABLE 3.

Summary of specific extracellular proteins of EHEC and EPEC identified by MALDI-TOF MS

| Spot no. (EHEC or EPEC) | Sequence coverage (%) | Protein size (Da)/pI (calculated) | Matched E. coli strain | NCBI accession no. | Matched protein name in EHEC and other E. coli databases | ler/ihf regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27-EHEC | 30 | 141,758.4/6.36 | EDL933 | 3822134 | EspP | −/− |

| 28-EHEC | 28 | 99,548.5/6.39 | EDL933 | 10955349 | TagA | +/+ |

| 29-EHEC | 43 | 24,691.8/6.11 | EDL933 | 15802406 | Hypothetical protein | −/− |

| 30-EPEC | 30 | 140,860.9/5.61 | E2348/69 | 1764164 | EspC | +/+ |

| 31-EPEC | 27 | 20,977.7/10.61 | E2348/69 | 2865308 | EspF | +/+ |

| 32-EPEC | 24 | 17,879.9/6.96 | EDL933 | 15802663 | Putative superinfection exclusion protein B of prophage CP-933V | −/− |

| 33-EPEC | 23 | 52,982.7/4.51 | E2348/69 | 5107855 | FliC | −/+ |

FIG. 3.

Extracellular proteins from EHEC EDL933. The proteins were separated by 2-DE using IPG at pHs 3 to 10. The circled proteins were identified by peptide mass mapping by MALDI-TOF MS. Numbers represent the spot identification numbers listed in Tables 2 and 3.

FIG. 4.

Extracellular proteins from EPEC E2348/69. The proteins were separated by 2-DE using IPG at pHs 3 to 10. The circled proteins were identified by peptide mass mapping by MALDI-TOF MS. Numbers represent the spot identification numbers listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Of these 59 proteins in the EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 extracellular proteomes, 26 were produced in both strains (Table 2). Three of the Esp proteins (EspA, EspB, and EspD) appeared as the most prominent protein spots distributed from the acidic to the neutral pH range (pH 3 to 6) in both the EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 extracellular proteomes. EspB and EspD are components of the TTSS translocon and are required for the delivery of the translocated intimin receptor (Tir) via the TTSS needle complex with a filamentous extension formed by EspA (9, 21, 22, 42). The high-molecular-weight heat shock proteins Hsp60 (GroEL) and Hsp70 (DnaK), which may function as chaperons in the type II and type IV secretion systems with less specificity for the target preprotein (4), accumulated in the acidic region in the EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 extracellular proteomes. For Legionella pneumophila and Helicobacter pylori, Hsp60 and Hsp70 were reported to be involved in colonization, attachment, and invasion (17). The identification of similar heat shock proteins in the extracellular proteomes of EHEC and EPEC may suggest their participation in pathogenesis. One protein from EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, with a high level of similarity to an unknown protein encoded by prophage CP-933K in EHEC, and another protein from EPEC E2348/69 which is homologous to the putative superinfection exclusion protein B of prophage CP-933V in EHEC were identified in the respective proteomes. Many phage proteins have been reported to be virulence factors (2), which implicates that these two putative prophage-encoded proteins may play important roles in EHEC and EPEC pathogenesis.

Several enzymes that are involved in different metabolic processes were found in the extracellular proteomes of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69. These were nucleotide metabolic enzymes such as phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthase; enzymes in the glycolytic pathway such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, triosephosphate isomerase, phosphoglycerate mutase, and enolase; some amino acid metabolism enzymes such as serine hydroxymethyltransferase; and one detoxification enzyme, alkyl hydroperoxide reductase C22. Furthermore, some outer membrane, periplasmic, and cytosolic proteins were also detected in the extracellular proteomes.

The uncommon ECPs EspP and TagA (also called StcE [24]) and a hypothetical protein were found only in EHEC EDL933. EspP is a secreted serine protease that cleaves pepsin and human coagulation factor V and was proposed to be a contributing factor in mucosal hemorrhaging in patients (3). TagA is an extracellular metalloprotease and was recently reported to be a protease that specifically cleaves the C1 esterase inhibitor (24). These two proteases are encoded by the EHEC large plasmid pO157 and are regarded as the virulence factors of EHEC. EspC, EspF, a hypothetical protein, and the putative superinfection exclusion protein B of prophage CP-933V were found in EPEC E2348/69. EspC is a secreted immunoglobulin A protease-like protein encoded within a second pathogenicity island in the EPEC chromosome and is regarded as an enterotoxin (27). For EPEC E2348/69, we also identified EspF, which induces epithelial cell death but whose mechanism remains unknown (5). The genome of EHEC EDL933 also contains the espF gene, and the encoded protein shares 93.4% identity at the amino acid level with EspF of EPEC E2348/69. The reason that we did not detect EspF in the ECPs of EHEC EDL933 may be due to the low level of secretion of EspF and its extremely basic pI.

EHEC and EPEC are very similar pathogens. They colonize the intestinal mucosa, subvert intestinal epithelial cell function, and produce the characteristic AE lesion via their secreted and membrane proteins (18, 19). From the ECP proteomic profiles, 26 of these proteins, or 90 and 87%, respectively, of the total identified proteins, are common in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, which demonstrates the close relationship between these two pathogens. At the same time, there are several proteins (such as TagA, EspP, and EspC) that are exclusively produced by EHEC EDL933 or by EPEC E2348/69. This shows that there are variations between these two E. coli strains. Our proteome profiles of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 have demonstrated both the similarity and the divergence of these two pathogens. The variability in proteins that may interact with the host suggests that these variable proteins may be subject to natural selection for evasion of the host immune system or may serve to spread a particular strain in a given population (7).

The most prominent proteins in the EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 extracellular proteomes are mainly secreted proteins, such as EspA, EspB, EspC, EspD, EspF, EspP, TagA, and Tir. The heat shock proteins (such as Hsp60 and Hsp70), which help with protein refolding and prevent protein degradation, were reported earlier to be released into the extracellular fraction (33). Though some outer membrane, periplasmic, and cytosolic proteins were detected in our extracellular proteome profiles, this was probably due to lysis of the bacteria in the culture or to the formation of blebs (43). Some protein spots could not be identified, possibly due to their low molecular weights, which would not produce enough peptides for fingerprint analysis. Despite these limitations, our results show that the coupling of silver staining and MALDI-TOF analysis is a sensitive method for protein detection, and the extracellular proteomes that we generated are reliable and reproducible.

Identification of Ler- and IHF-regulated proteins.

The extracellular proteomes of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 give an integrated overview of their ECP profiles and can be used as a reference for global analyses of protein expression in pathogenic E. coli strains (such as EHEC and EPEC) under various culture conditions and for comparisons between wild types and mutant strains. A comparison of the extracellular proteomes of the wild-type strains and their ler and ihf mutants revealed that four common protein spots, namely, EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir, were present only in the wild-type strains of both EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 and were absent from the ler and ihf mutants (Fig. 5 and 6). These four proteins are TTSS secretion proteins that are highly conserved in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, with a small degree of divergence, as follows: espB (74.01% identity), espA (84.63% identity), espD (80.36% identity), and tir (66.48% identity) (31). They are regulated by Ler and IHF at the transcription level (1, 13, 26), and their expression is dependent upon culture conditions, the growth phase, and host contact (8, 16, 35). EspF is also cotranscribed with espADB and regulated by Ler (10). However, EspF was identified only in EPEC E2348/69, not in EHEC EDL933.

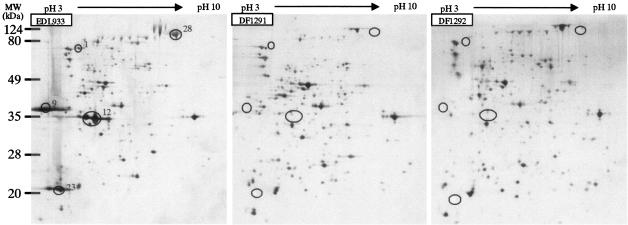

FIG. 5.

Comparative proteome analysis of the EHEC EDL933 wild-type strain and its ler mutant (DF1291) and ihf mutant (DF1292). The proteins were separated by 2-DE using IPG at pHs 3 to 10. The circled proteins were detected only in the wild-type strain and were missing in the ler and ihf mutants. Numbers represent the spot identifications listed in Tables 2 and 3.

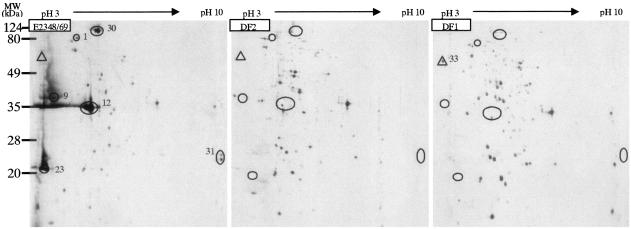

FIG. 6.

Comparative proteome analysis of the EPEC E2348/69 wild-type strain and its ler mutant (DF2) and ihf mutant (DF1). The proteins were separated by 2-DE using IPG at pHs 3 to 10. The circled proteins were detected only in the wild-type strain and were missing in the ler and ihf mutants. The protein indicated with a triangle was present only in the ihf mutant. Numbers represent the spot identifications listed in Tables 2 and 3.

The differences in the protein profiles of the wild-type strains and the ler and ihf mutants could be attributed to the lost functions of Ler and IHF, which resulted in decreased protein secretion by the ler and ihf mutants. On the other hand, there are other Ler- and IHF-regulated TTSS proteins that have not been identified here. This may be due to their higher translocation levels than secretion levels, such as the case for EspH (41), or to their extreme acidic or basic isoelectric points, which would allow them to migrate beyond the normal IPG gel strip range and thus not be visualized by 2-DE.

We also identified one flagellar component protein, FliC, that is solely present in EPEC 2348/69 ihf mutants (Fig. 6). This proteomic result indicates that ihf depresses the expression of FliC, which is consistent with a report that IHF mediates the repression of flagella in EPEC (44).

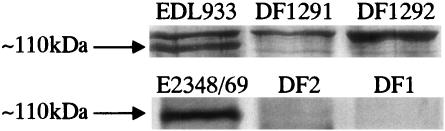

A comparison of 1-DE profiles of ECPs of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 and their ler and ihf mutants showed that a protein band of about 110 kDa was regulated by Ler and IHF (Fig. 7). Elliott and coworkers (10) also reported that Ler regulated a 110-kDa protein in both EPEC E2348/69 and EHEC EDL933. This protein was identified as EspC in EPEC by use of an anti-EspC antibody, while the identity of the equivalent 110-kDa protein in EHEC remained unclear. In the extracellular proteome of EHEC EDL933, TagA, which has a similar molecular weight but a different isoelectric point than EspC (ca. 110 kDa), was found to be regulated by Ler (Fig. 5 and 7). The expression level of TagA was much lower in the ler mutant than in the wild type, indicating that TagA was regulated by Ler. By using a proteomic approach, we have identified the cryptic 110-kDa protein in EHEC EDL933, which could not be identified by Elliott and coworkers by use of an anti-EspC antibody (10), as TagA.

FIG. 7.

1-DE of ECPs from EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 wild-type strains, their ler mutants (DF1291 for EHEC and DF2 for EPEC), and their ihf mutants (DF1292 for EHEC and DF1 for EPEC). Only the high-molecular-mass bands are shown. The ca. 110-kDa protein bands were present in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, but not in their respective ler and ihf mutants.

Using the proteomic approach, we found two dominant EspB spots in both the EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 extracellular proteomes (Fig. 3 and 4). N-terminal sequencing of these two EspB proteins revealed that the first 10 residues of their N-terminal sequences were intact and identical (data not shown). EspB is one of the dominant proteins in the ECPs of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 and is central to EPEC and EHEC interactions with host cells in vitro (11, 23, 39, 40). In addition to being translocated, EspB is needed to facilitate translocation (21, 42). Thus, it is possible that EspB exists in different forms via modifications for different functions. EspB has serine- and threonine-rich domains, which may be phosphorylated to produce two forms in the supernatant. However, an alkaline phosphatase analysis showed no detectable phosphorylation (data not shown). Further characterization of EspB to determine the possible functions of these two EspB proteins is ongoing.

Applications and conclusions.

The ability of pathogenic bacteria to cause disease in a susceptible host is determined by multiple factors acting individually or together at different stages of infection. Proteomics can provide an integrated view of the gene products of certain bacteria for global analyses. The secretion of virulence factors is a common feature of many pathogenic bacteria, and thus it is important to generate extracellular proteomes to facilitate studies of bacterial pathogenesis. For the first time, we have provided the extracellular proteomes of EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69 and used a proteomic approach to analyze the ECPs of these two closely related human pathogens. These proteome profiles can help us to link virulence determinants in an integrated manner and also can facilitate the characterization of changes in mutants. In this study, we confirmed several virulence proteins that are regulated by Ler and IHF and also found some interesting features for further investigation.

EHEC serotypes other than O157:H7 and EPEC are not routinely identified in most clinical microbiology laboratories. Thus, the characteristic proteins of EHEC and EPEC, as identified in their extracellular proteomes, could also be used as new diagnostic markers of these pathogens. For example, EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir are common in EHEC EDL933 and EPEC E2348/69, while EspP and TagA are specific to EHEC EDL933 and EspC is specific to EPEC E2348/69. In addition, many other diarrhea-causing strains of E. coli cannot be easily isolated in the clinical microbiology laboratory, and a proteomic analysis of these strains may reveal biomarkers that could be used for their diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National University of Singapore for providing a research grant for this work.

We acknowledge Y. Yamada, S. Joshi, and Q. Lin for their technical assistance with running 2-DE gels and their suggestions for the proteomic work. We thank P. Tang for a critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beltrametti, F., A. U. Kresse, and C. A. Guzman. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the esp genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3409-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd, E. F., and H. Brussow. 2002. Common themes among bacteriophage-encoded virulence factors and diversity among the bacteriophages involved. Trends Microbiol. 10:521-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunder, W., H. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 1997. EspP, a novel extracellular serine protease of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 cleaves human coagulation factor V. Mol. Microbiol. 24:767-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.China, B., and F. Goffaux. 1999. Secretion of virulence factors by Escherichia coli. Vet. Res. 30:181-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crane, J. K., B. P. McNamara, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2001. Role of EspF in host cell death induced by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:197-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnenberg, M. S., J. B. Kaper, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and host epithelial cells. Trends Microbiol. 5:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg, M. S., and T. S. Whittam. 2001. Pathogenesis and evolution of virulence in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 107:539-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebel, F., C. Deibel, A. U. Kresse, C. A. Guzman, and T. Chakraborty. 1996. Temperature- and medium-dependent secretion of proteins by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:4472-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebel, F., T. Podzadel, M. Rohde, A. U. Kresse, S. Kramer, C. Deibel, C. A. Guzman, and T. Chakraborty. 1998. Initial binding of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli to host cells and subsequent induction of actin rearrangements depend on filamentous EspA-containing surface appendages. Mol. Microbiol. 30:147-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott, S. J., V. Sperandio, J. A. Giron, S. Shin, J. L. Mellies, L. Wainwright, S. W. Hutcheson, T. K. McDaniel, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator controls expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:6115-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foubister, V., I. Rosenshine, M. S. Donnenberg, and B. B. Finlay. 1994. The eaeB gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is necessary for signal transduction in epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 62:3038-3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, I. Rosenshine, G. Dougan, J. B. Kaper, and S. Knutton. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30:911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedberg, D., T. Umanski, Y. Fang, and I. Rosenshine. 1999. Hierarchy in the expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 34:941-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goosen, N., and P. van de Putte. 1995. The regulation of transcription initiation by integration host factor. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi, T., K. Makino, M. Ohnishi, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, K. Yokoyama, C. G. Han, E. Ohtsubo, K. Nakayama, T. Murata, M. Tanaka, T. Tobe, T. Iida, H. Takami, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, N. Ogasawara, T. Yasunaga, S. Kuhara, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, and H. Shinagawa. 2001. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 8:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiroyuki, A., T. Ichiro, T. Toru, O. Akiko, and S. Chihiro. 2002. Bicarbonate ion stimulates the expression of locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded genes in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 70:3500-3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman, P. S., and R. A. Garduno. 1999. Surface-associated heat shock proteins of Legionella pneumophila and Helicobacter pylori: roles in pathogenesis and immunity. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 7:58-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis, K. G., J. A. Giron, A. E. Jerse, T. K. McDaniel, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7996-8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvis, K. G., and J. B. Kaper. 1996. Secretion of extracellular proteins by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli via a putative type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 64:4826-4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny, B., and B. B. Finlay. 1995. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7991-7995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenny, B., R. DeVinney, M. Stein, D. J. Reinscheid, E. A. Frey, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell 91:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutton, S., I. Rosenshine, M. J. Pallen, I. Nisan, B. C. Neves, C. Bain, C. Wolff, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 1998. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 17:2166-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kodama, T., Y. Akeda, G. Kono, A. Takahashi, K. Imura, T. Iida, and T. Honda. 2002. The EspB protein of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli interacts directly with α-catenin. Cell. Microbiol. 4:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lathem, W. W., T. E. Grys, S. E. Witowski, A. G. Torres, J. B. Kaper, P. I. Tarr, and R. A. Welch. 2002. StcE, a metalloprotease secreted by Escherichia coli O157:H7, specifically cleaves C1 esterase inhibitor. Mol. Microbiol. 45:277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaniel, T. K., K. G. Jarvis, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1664-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellies, J. L., S. J. Elliott, V. Sperandio, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler). Mol. Microbiol. 33:296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellies, J. L., F. Navarro-Garcia, I. Okeke, J. Frederickson, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. espC pathogenicity island of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes an enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 69:315-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nash, H. A. 1996. The HU and IHF proteins: accessory factors for complex protein-DNA assemblies, p. 149-179. In E. C. C. Lin and A. C. Lynch (ed.), Regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Chapman Hall, Austin, Tex.

- 29.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paton, J. C., and A. W. Paton. 1998. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:450-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perna, N. T., G. F. Mayhew, G. Posfai, S. J. Elliott, M. S. Donnenberg, J. B. Kaper, and F. R. Blattner. 1998. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 66:3810-3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugsley, A. P. 1993. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:50-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice, P. A., S. W. Yang, K. Mizuuchi, and H. A. Nash. 1996. Crystal structure of an IHF-DNA complex: a protein induced DNA U-turn. Cell 87:1295-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenshine, I., S. Ruschkowski, and B. B. Finlay. 1996. Expression of attaching/effacing activity by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on growth phase, temperature, and protein synthesis upon contact with epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:966-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu, T., K. Shima, K. Yoshino, K. Yonezawa, T. Shimizu, and H. Hayashi. 2002. Proteome and transcriptome analysis of the virulence genes regulated by the VirR/VirS system in Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 184:2587-2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacket, C. O., M. B. Sztein, G. Losonsky, A. Abe, B. B. Finlay, B. P. McNamara, G. T. Fantry, S. P. James, J. P. Nataro, M. M. Levine, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2000. Role of EspB in experimental human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Infect. Immun. 68:3689-3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor, K. A., C. B. O'Connell, P. W. Luther, and M. S. Donnenberg. 1998. The EspB protein of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is targeted to the cytoplasm of infected HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 66:5501-5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tu, X., I. Nisan, C. Yona, E. Hanski, and I. Rosenshine. 2003. EspH, a new cytoskeleton-modulating effector of enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 47:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolff, C., I. Nisan, E. Hanski, G. Frankel, and I. Rosenshine. 1998. Protein translocation into host epithelial cells by infecting enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 28:143-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaron, S., G. L. Kolling, L. Simon, and K. R. Matthews. 2000. Vesicle-mediated transfer of virulence genes from Escherichia coli O157:H7 to other enteric bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4414-4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yona-Nadler, C., T. Umanski, S. Aizawa, D. Friedberg, and I. Rosenshine. 2003. Integration host factor (IHF) mediates repression of flagella in enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 149:877-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]