Abstract

We cloned the carB and carRA genes involved in β-carotene biosynthesis from overproducing and wild-type strains of Blakeslea trispora. The carB gene has a length of 1,955 bp, including two introns of 141 and 68 bp, and encodes a protein of 66.4 kDa with phytoene dehydrogenase activity. The carRA gene contains 1,894 bp, with a single intron of 70 bp, and encodes a protein of 69.6 kDa with separate domains for lycopene cyclase and phytoene synthase. The estimated transcript sizes for carB and carRA were 1.8 and 1.9 kb, respectively. CarB from the β-carotene-overproducing strain B. trispora F-744 had an S528R mutation and a TAG instead of a TAA stop codon. The overproducing strain also had a P143S mutation in CarRA. Both B. trispora genes could complement mutations in orthologous genes in Mucor circinelloides and could be used to construct transformed strains of M. circinelloides that produced higher levels of β-carotene than did the nontransformed parent. The results show that these genes are conserved across the zygomycetes and that the B. trispora carB and carRA genes are functional and potentially useable to increase carotenoid production.

Carotenoids are a family of yellow to orange-red terpenoid pigments synthesized by photosynthetic organisms and by many bacteria and fungi (10). They have beneficial health effects, including protecting against oxidative damage, and may be responsible for the appearance of these colors in plants and animals (9). Carotenoids are also desirable commercial products used as additives and colorants in the food industry (7). Traditionally, carotenoids were obtained by extraction from plants or by direct chemical synthesis. Only a few of the more than 600 identified carotenoids are produced industrially, with β-carotene (a popular additive for butter, ice cream, orange juice, candies, etc.) the most prominent (7; U. Marz, The Global Market for Carotenoids, Business Communication Co., Norwalk, Conn.). Due to the increasing importance of β-carotene, biotechnological methods of production have been sought, with the green alga Dunaliella salina and the fungus Blakeslea trispora the microorganisms of choice for industrial production of this molecule (Marz, The Global Market for Carotenoids).

The biosynthetic pathway for β-carotene has been determined for fungi such as Phycomyces blakesleeanus and Neurospora crassa (12, 21). It contains three enzymatic activities: (i) phytoene synthase, which links two molecules of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate to form phytoene; (ii) phytoene dehydrogenase, which introduces four double bonds in the phytoene molecule to yield lycopene; and (iii) lycopene cyclase, which sequentially converts the ψ acyclic ends of lycopene to β rings to form γ-carotene and β-carotene. A similar biosynthetic pathway is known in all carotenogenic organisms (20). The accumulation of β-carotene in B. trispora is associated with sexual interaction (18). Mating of two sexually compatible strains increases mycelial β-carotene accumulation 5- to 15-fold, as does the addition of trisporic acids, compounds with hormonal activity formed upon mating (25, 35).

The carB and carRA (or carRP) genes, encoding phytoene dehydrogenase and lycopene cyclase/phytoene synthase, have been cloned from the zygomycetes P. blakesleeanus (3, 29) and Mucor circinelloides (36, 37), but there is no information on the β-carotene biosynthetic genes of the commercially important B. trispora. The carRA genes have two domains: (i) the R domain, located near the 5′ end, which encodes lycopene cyclase activity, and (ii) the A (or P) domain, which is downstream of the R domain and encodes phytoene synthase. The carB and carRA genes of M. circinelloides and P. blakesleeanus are closely linked, divergently transcribed, and coordinately induced by blue light, with a bidirectional promoter between them (3, 36).

The objectives of this study were to clone and characterize the β-carotene biosynthetic genes of B. trispora and to determine whether these sequences were functional in M. circinelloides and could be used to increase the amount of β-carotene it synthesizes. This report is the first description of β-carotene biosynthetic genes of B. trispora, a fungus used industrially to produce β-carotene and lycopene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms, culture conditions, and cloning vectors.

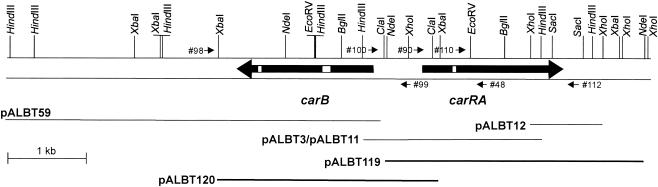

The fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. trispora (24) and M. circinelloides (28, 36) were cultured as previously described, with uridine (400 μg/ml) or leucine (200 μg/ml) supplements as necessary. Escherichia coli SURE (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and E. coli LE392 (30) were the hosts for λGEM12 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) phage derivatives. E. coli DH5α (30) was the recipient for high-frequency plasmid transformation. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels with the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) and subcloned in pBluescript I KS(+) (Stratagene) and pBC KS(+) (Stratagene). pALBT3, pALBT11, pALBT12, and pALBT59 were sequenced (Fig. 1). pLeu4 (2, 27) and pEPM9 (8) were used as M. circinelloides shuttle vectors. General procedures for plasmid DNA purification, cloning, and transformation of E. coli were those of Sambrook et al. (30).

TABLE 1.

Fungal strains used in this work

| Straina | Sexb | Genotypec | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRRL2457 | − | Wild type | Low producer of β-carotene | 24 |

| F-744 | − | Unknown | High producer of β-carotene | 13 |

| ATCC 1216a | + | Wild type | Low producer of β-carotene | 36 |

| ATCC 1216b | − | Wild type | Low producer of β-carotene | 36 |

| MS8 | − | leuA1 carRP5 | β-Carotene-deficient auxotroph | 36 |

| MS12 | − | leuA1 pyrG4 | Low producer of β-carotene auxotroph | 28 |

| MS23 | − | leuA1 pyrG4 carB11 | β-Carotene-deficient auxotroph | 28 |

The first two strains are B. trispora, and the remainder are M. circinelloides strains. NRRL2457, originally obtained from the Northern Regional Research Laboratory, Peoria, III., is the standard wild type. F-744 was from the Russian National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms, Moscow, Russia. Strains ATCC 1216a and ATCC 1216b (also named CBS276.49 and CBS277.49, respectively), originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va., are wild-type strains. Mutants MS8, MS12, and MS23 were all derived from ATCC 1216b and were provided by A. P. Eslava, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.

+ and − are the standard designations of the two sexes in Mucorales.

leuA1 causes leucine auxotrophy, pyrG4 causes uracil auxotrophy, carRP5 causes lycopene cyclase phytoene synthase deficiency, and carB11 causes phytoene dehydrogenase deficiency.

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the B. trispora genomic region containing the carB and carRA genes. The ORFs and the direction of transcription are shown by large arrows. White boxes inside the arrows represent introns. Small arrows indicate the primers used for PCR amplification. Plasmids described in the text appear below the arrows. The thick lines represent the plasmids used to transform M. circinelloides. The 8,788-bp sequenced region is represented by the entire map, and the 2,430-bp HindIII fragment found in all four positive phages is represented by pALBT3/pALBT11.

Construction and screening of B. trispora genomic library.

DNA from B. trispora F-744 was extracted as previously described (33). Fragments of genomic DNA (17 to 22 kb) were purified from DNA partially digested with Sau3AI, ligated to λGEM12, and packaged with the Gigapack II Gold kit (Stratagene) to yield approximately 5 × 104 PFU. The library was amplified in E. coli LE392, plated to obtain ∼4 × 104 PFU, and hybridized with a [32P]dCTP-labeled probe consisting of a 560-bp internal fragment from the carRP gene of M. circinelloides (30). Four recombinant phages were isolated and amplified in liquid medium to purify their DNA (30).

Nucleic acid hybridization and sequencing.

Southern hybridizations were made with digoxigenin-labeled probes (Non-radioactive labeling and immunological detection kit, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. A 778-bp BglII-NdeI fragment of the carB gene and a 526-bp BglII-SalI fragment of the carRA gene were used as probes. Clones to be sequenced were constructed with the Erase a base system (Promega) and sequenced with an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). DNA sequences were analyzed with the Dnastar and Winstar packages (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and compared to known sequences with the BLASTP and BLASTX programs (1). The codon-preference algorithm (16) was used to detect the presence of open reading frames (ORFs). Multiple protein alignments were made with the Clustal V algorithm, and pairwise alignments were made by the Lipman-Pearson method (MegAlign, Winstar). RNA secondary structures that can act as potential transcriptional terminators were predicted with the aid of the M-fold program (23).

PCR amplification.

Primers 61 (5′-CGCGCCGACTGCCATTGACT-3′) and 62 (5′-CACGCACGCCGCCTTGACA-3′) were designed to amplify a 560-bp internal fragment of the carRP gene of M. circinelloides (GenBank AJ238028). The carB gene of B. trispora NRRL2457 was amplified as a 2.6-kb fragment with primers 98 (5′-GGGTTTCTTTGTTTGAGCTGATTCTGATAC-3′) and 99 (5′-GATACTGTCATCTCGAGAGCGTTG-3′). The carRA gene of B. trispora NRRL2457 was amplified in two fragments (overlapping 187 bp): a 1.3-kb fragment including the 5′ region with primers 100 (5′-CATGCCTGACTTTCTTTTTCCATCG-3′) and 48 (5′-CAGGCATTCTTCTACAGG-3′) and a 1.5-kb fragment covering the 3′ region with primers 110 (5′-TCTTTGGCTGGGTGCTGGTGAA-3′) and 112 (5′-CCAGAAGCGGGGTGAACTCATTG-3′). Optimized amplification reaction mixtures (each 20 μl) were processed in a DNA Thermal Cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) and contained about 50 ng of genomic DNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg of nuclease-free bovine serum albumin/ml, 0.25 μM each primer, 1.0 U of Turbo Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The reaction mixtures were overlaid with mineral oil and subjected to 25 PCR cycles as follows: (i) for primers 61 and 62, 94°C for 30 s (120 s for the first cycle), 55°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s; (ii) for primers 98 and 99, 94°C for 60 s (120 s for the first cycle), 45°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 180 s; (iii) for primers 100 and 48, 94°C for 60 s (120 s for the first cycle), 41°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 180 s; and (iv) for primers 110 and 112, 94°C for 60 s (120 s for the first cycle), 57°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 240 s. Total RNA from B. trispora F-744 was subjected to 35 PCR cycles as follows: 94°C for 10 s, 41°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 45 s (extending 5 s per cycle after the 11th repeat) with primers 90 (5′-CTTTTTATTTTATCTCTATGTCAATACTCAC-3′) and 48, with the Titan One Tube RT-PCR system (Roche) used to amplify the cDNA from the 5′-region of the carRA gene as a 670-bp fragment. Amplified fragments were purified from agarose gels with the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) and subcloned into EcoRV-digested pBluescript I KS(+).

Transcriptional analysis of the carB and carRA genes.

A pilot-scale (800-liter) fed-batch fermentation was carried out by mating the two sexual forms (+ and −) of B. trispora to maximize β-carotene production (13). At 96 h, mycelium was frozen in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was recovered (4). RNA was resolved by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis and blotted onto Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) according to standard procedures (30). Two plasmids, pALBT132 (466-bp BglII-EcoRV of carRA) and pALBT133 (415-bp EcoRV-NdeI of carB) were constructed in pBluescript I KS(+) to be used as templates for the synthesis of an antisense digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe with the DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche). The filters were hybridized at 68°C overnight with DIG-Easy Hyb buffer (Roche) and subsequently washed for 15 min at room temperature in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, followed by two washes of 15 min each at 68°C in 0.1× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Immunological detection with CDP-Star chemiluminescent substrate (Roche) was carried out following the manufacturer's instructions.

Transformation of M. circinelloides.

Plasmids pLeu4 (2, 27), pEPM9 (8), pALBT119, and pALBT120 were used to transform M. circinelloides. pALBT119 (Fig. 1) was constructed by subcloning the carRA gene as a 3.6-kb NdeI fragment filled with Klenow into the SmaI site of pLeu4. Likewise, the introduction of a 3.0-kb XbaI fragment containing the carB gene in the XbaI site of pEPM9 generated pALBT120 (Fig. 1). M. circinelloides was transformed as previously described (28, 36) with a mixture of 1.5 mg of Caylase (Cayla, Toulouse, France)/ml and 4 to 12 U of Streptozyme/ml for protoplast preparation. Several transformants of each plasmid, prototrophic for leucine or uridine, were selected on yeast nitrogen base (YNB) minimal medium (19) osmotically stabilized with 0.55 M sorbitol.

Carotenoid analysis.

Carotenoid production was tested following growth on YNB plates for 4 days (36). Carotenoids were extracted with a mixture of methanol and dichloromethane (50/50 ratio) and redissolved in acetone. High-performance liquid chromatography analyses were performed with a Hypersil octyldecyl silane column (resin particle diameter, 5 μm; 100 by 4.6 mm) and acetonitrile-methanol-chloroform (47/47/6 ratio) with a flow rate of 1 ml/min as the mobile phase.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The carB-carRA DNA sequences of B. trispora NRRL2457 and B. trispora F-744 have been deposited as GenBank accession numbers AY176663 and AY176662, respectively.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of the carB and carRA genes from the β-carotene-overproducing strain B. trispora F-744 (GenBank AY176662).

An 8,788-bp DNA region (Fig. 1) contained two complete ORFs read in opposite directions corresponding to the carB and carRA genes (Table 2). Two introns were predicted in carB (intron 1 starts at bp 4485 and stops at bp 4345; intron 2 starts at bp 3495 and stops at bp 3428) (GenBank AY176662) and one in carRA (the intron starts at bp 6095 and stops at bp 6164) (5). Intron splicing in carRA was confirmed by cDNA sequence. General transcription signals were detected at the 5′-flanking region (TATA and CAAT boxes at bp 5147, 5294, 5459, and 5634) and 3′-flanking region (AATAAA polyadenylation signal at bp 3111 and 7619), as were poorly conserved APE-like elements (consensus sequence GAANNTTGCC at bp 5216, 5460, 5228, and 5424) involved in gene regulation in response to light. Three copies of the binding site (TTCTTTGTTY at bp 5341, 5358, and 5559) for the transcription factor Ste11 (a TR box) were found with minor changes in the carB-carRA promoter region of B. trispora. A conserved sequence (GCXTGTATXTTATAXAAAXAAXAA) including the TATA box is present upstream of the translation start codon of carB (position −78) and carRA (position −68) genes. RNA secondary structures that can act as potential transcriptional terminators were downstream of carB and carRA genes (23).

TABLE 2.

Features of carB and carRA genes and deduced proteins from zygomycetes

| Zygomycete | Intragenic region (bp) | Gene

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

carB

|

carRA

|

||||||

| Length (bp) | Intron(s) (bp) | Molecular mass (kDA) of deduced protein product (no. of aa) | Length (bp) | Intron (bp) | Molecular mass (kDA) of deduced protein product (no. of aa) | ||

| B. trisporaa | 611 | 1,955 | 141, 68 | 66.4 (582) | 1,894 | 70 | 69.6 (608) |

| M. circinelloidesb | 447 | 1,864 | 61, 63 | 65.6 (579) | 1,845 | 61 | 69.8 (614) |

| P. blakesleeanusc | 1,381 | 1,935 | 183 | 65.9 (583) | 1,806 | 265 | 68.6 (602) |

Deduced amino acid sequences encoded by the carB and carRA genes of B. trispora F-744.

The CarB deduced protein (Table 2) is similar in size, sequence, and signature pattern to other fungal phytoene dehydrogenases, with amino acid sequence similarity to phytoene dehydrogenases from M. circinelloides (81%) (37), P. blakesleeanus (72%) (29), Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (50%) (38), N. crassa (49%) (32), Fusarium fujikuroi (48%) (22), and Cercospora nicotianae (47%) (15). A consensus dinucleotide binding motif for the flavin adenine dinucleotide superfamily [U4G(G/A)GUXGLX2(A/S)X2LX6-12UX(L/V)UEX4UGGX9-13(G/V)X3(D/E)XG, where X stands for any residue and U stands for a hydrophobic residue] (14) was located at the N terminus (IVVIGAGIGGTATAARLAREGFRVTVVEKNDFSGGRCSFIHHDGHRFDQG), and a bacterial-type phytoene dehydrogenase signature sequence, (N/G)X(F/Y/W/V)(L/I/V/M/F)XG(A/G/C)(G/S)(T/A)(H/Q/T)PG(S/T/A/V)G(L/I/V/M)X5(G/S) (6), corresponding to a carotenoid binding domain, was found at the C terminus (NLFFVGASTHPGTGVPIVLAG). The deduced CarB protein has a highly hydrophobic region at the C-terminal end that is characteristic of membrane-associated proteins.

The carRA deduced protein was similar to fungal proteins with lycopene cyclase/phytoene synthase activity and had high similarity to lycopene cyclases/phytoene synthases from M. circinelloides (67%) (36), P. blakesleeanus (55%) (3), X. dendrorhous (31%) (39), F. fujikuroi (29%) (22), and N. crassa (28%) (31). The CarRA protein had two different domains, as described for P. blakesleeanus, M. circinelloides, and X. dendrorhous: a hydrophobic transmembrane domain (R), located near to the 5′ end expressing lycopene cyclase (240 residues), and a hydrophilic domain, P, located downstream that expresses phytoene synthase (362 residues). A putative protease cleavage site, AQAILH (residues 241 to 246), that could split the polypeptide between residues 243 and 244 is present at the boundary between the two domains.

Wild-type carB and carRA genes from B. trispora (GenBank AY176663).

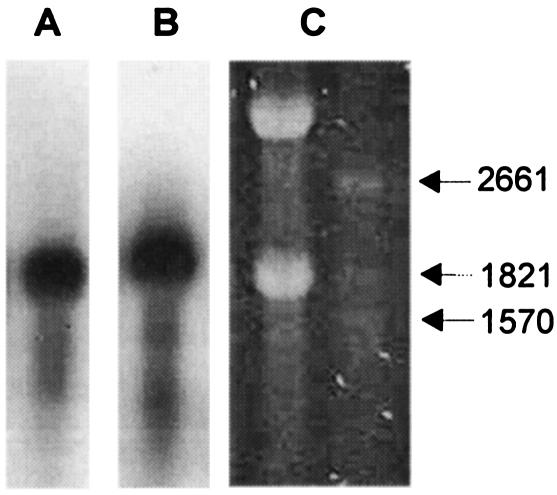

The B. trispora wild-type strain (NRRL2457) and mutant β-carotene-overproducing strain (F-744) both had the same hybridization pattern in Southern blots, suggesting that carB and carRA are present at a single copy per genome. The carB and carRA mutant and wild-type genes differ from each other by two nucleotides per gene (four total differences). The A1791→C mutation in carB substitutes an arginine for the wild-type serine at position 528 (S528R). An A1958→G transition mutation occurred in the carB stop codon, changing the wild-type TAA to TAG but not affecting the protein sequence. The T497→C mutation in the carRA gene changes the wild-type proline at position 143 to a serine (P143S), while the C568→T mutation does not change the amino acid encoded (glycine at position 166). Transcripts of the carB (1.8-kb) and carRA (1.9-kb) genes were the expected size and were present at a constant level during fermentation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Transcription of carB (A) and carRA (B) genes. Northern analyses were done with total RNA purified at 96 h from pilot scale fermentation under β-carotene production conditions (13). (C) Stained gel showing rRNAs and molecular weight markers used to estimate transcript size of carB (1.8-kb) and carRA (1.9-kb) genes.

Expression of the carB and carRA genes of B. trispora strain F-744 in M. circinelloides.

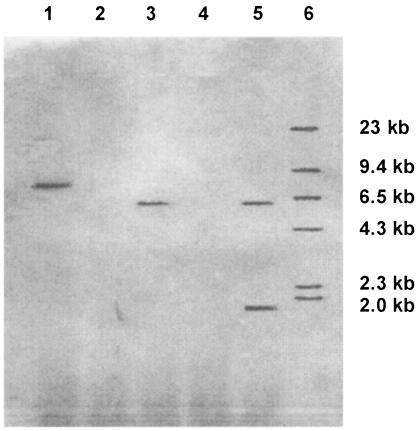

Several transformants for each strain-plasmid combination (Table 3) were grown on YNB plates. The mycelium of the MS8/pLeu4 and MS23/pEPM9 control transformants remained as white as the parental strains, while MS8/pALBT119 and MS23/pALBT120 had a weak yellowish coloration, suggesting the accumulation of carotenoids other than phytoene. Southern blot analyses of digested genomic DNA with probes from carRA (Fig. 3) and carB (data not shown) genes are consistent with autonomous replication, the absence of rearrangements, and the lack of hybridization with the endogenous carRP gene of M. circinelloides. Ampicillin-resistant colonies were selected by transforming E. coli DH5α with total DNA from MS8/pALBT119, MS12/pALBT119, MS12/pALBT120, MS12/pALBT119/pALBT120, and MS23/pALBT120. Fifty independent clones of each type were analyzed, and most of them (>97%) had the expected restriction pattern for pALBT119 and pALBT120, confirming the extrachromosomal location of the plasmids in M. circinelloides and an almost total lack of rearrangements. Most of the E. coli transformants selected with DNA from MS12/pALBT119/pALBT120 (96%) had the pALBT119 pattern, implying a lower copy number of pALBT120 in M. circinelloides. The carotenoids accumulated by wild-type strains of M. circinelloides, mutants, and transformants were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Carotenoids produced by M. circinelloidesa

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype | Color | Carotenoid

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Carotene | γ-Carotene | Lycopene | Neurosporene | Phytoene | |||

| ATCC 1216a | Wild type | Yellow | 290 ± 87 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 0 | ND |

| ATCC 1216b | Wild type | Yellow | 380 ± 32 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0 | ND |

| MS8 | leuA1 carRP5 | White | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND |

| MS8/pLeu4 | leuA1 carRP5 leuA | White | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND |

| MS8/pALBT119 | leuA1 carRP5 leuA carRA | Weak yellowish | 8.7 ± 1.3 | 11 ± 0.9 | 19 ± 2.3 | 0 | ND |

| MS23 | leuA1 pyrG4 carB11 | White | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 ± 3.6 |

| MS23/pEPM9 | leuA1 pyrG4 carB11 pyrG | White | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND |

| MS23/pALBT120 | leuA1 pyrG4 carB11 | Yellowish | 230 ± 27 | 13 ± 3.4 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 1.4 |

| MS12 | leuA1 pyrG4 | Yellow | 400 ± 53 | 44 ± 11 | 30 ± 4.4 | 0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| MS12/pALBT119 | leuA1 pyrG4 leuA carRA | Yellow | 590 ± 59 | 84 ± 8.3 | 43 ± 8.2 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| MS12/pALBT120 | leuA1 pyrG4 pyrG carB | Yellowish | 390 ± 45 | 14 ± 4.7 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 0 | ND |

| MS12/pALBT119/pALBT120 | leuA1 pyrG4 leuA pyrG carRA carB | Yellow | 550 ± 83 | 25 ± 3.5 | 12 ± 3.0 | 0 | ND |

Average results (micrograms per gram of dry weight) of four independent cultures ± standard deviations are shown. ND, not determined.

FIG. 3.

Southern analysis of DNA from M. circinelloides MS8 (lanes 2 and 4) and MS8/pALBT119 (lanes 1, 3, and 5) with a 526-bp BglII-SalI fragment corresponding to the carRA gene of B. trispora as a probe. DNA was digested with BamHI (lanes 1 and 2), EcoRV (lanes 3 and 4), and PvuII (lane 5). Lane 6 contains the size markers.

DISCUSSION

We cloned the carB and carRA genes from the β-carotene-overproducing strain B. trispora F-744 and from the low-producing strain B. trispora NRRL2457. The deduced polypeptides, phytoene dehydrogenase and lycopene cyclase/phytoene synthase, are similar at the amino acid level to enzymes from the zygomycetes M. circinelloides and P. blakesleeanus, the ascomycetes N. crassa and F. fujikuroi, and the basidiomycete X. dendrorhous. The location and structure of the introns are not generally conserved. The first intron of the carB gene is located at almost the same position in B. trispora, M. circinelloides, and P. blakesleeanus. The single intron in carRA is also located in a similar position in B. trispora, M. circinelloides, and P. blakesleeanus but differs in size. The CarB deduced protein includes a dinucleotide binding motif in the N-terminal region and a carotenoid binding domain in the C terminus. This last motif is conserved in both bacterial and fungal sequences but differs from the motif for crtP-type phytoene dehydrogenases.

The three enzymatic activities needed to convert geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate to β-carotene in B. trispora depend on the expression of two closely linked genes that are divergently transcribed. A similar arrangement, which permits expression of the whole pathway from a single promoter region, also is found in P. blakesleeanus (3) and M. circinelloides (36). The promoter regions of B. trispora, M. circinelloides, and P. blakesleeanus differ significantly in both length and regulatory signals. APE elements probably involved in light regulation are located in the 5′ upstream region of N. crassa al-3 (11) and also are present with minor modifications in the carB-carRA promoter region of M. circinelloides (36), P. blakesleeanus (29), and B. trispora, even though β-carotene biosynthesis in B. trispora is not stimulated by blue light (34).

Other regulatory signals present in the promoter region of B. trispora and P. blakesleeanus include putative TR box binding sites for the Ste11 transcription factor, an HMG box protein essential for induction of sexual development in S. pombe (17). β-Carotene accumulation in B. trispora is strongly linked to sexual interaction and increases 5- to 15-fold during mating (18), which is consistent with the presence of the three putative TR boxes in the promoter region of the carB-carRA genes, if sexual development is mediated by an Ste11-like transcription factor in B. trispora. Two putative TR boxes are present in the carB-carRA promoter of P. blakesleeanus, but they are absent in this promoter of M. circinelloides.

The carB-carRA region of wild-type and overproducing strains differed at only four point mutations in the coding sequence. The S528R mutation of CarB is located in a poorly conserved region, while the P143S mutation of CarRA occurred in a conserved region. The effect of these mutations on enzymatic activities is not known.

There is no transformation system for B. trispora, so the function of the cloned sequences was tested indirectly with M. circinelloides. Heterologous expression of the P. blakesleeanus carB gene in a mutant of M. circinelloides lacking phytoene dehydrogenase only partially restores the enzymatic activity and β-carotene production and may be due to the formation of a poorly functional heterologous enzyme complex, improper recognition of the heterologous gene promoter, or the dilution of a fixed number of transcription factors across additional promoters. Transformation of M. circinelloides with autonomously replicating plasmids containing a homologous wild-type copy of the carB gene silences the carB function in 3% of transformants. This reduction in carB function is not due to differences in transcription levels but to the biosynthesis of two size classes of small antisense RNAs (26). Either inefficient heterologous expression or antisense RNA could explain the behavior of transformant MS23/pALBT120, in which β-carotene biosynthesis is partially restored and there is some accumulation of phytoene and neurosporene.

The expression of the carRA gene in mutant strain MS8, deficient in lycopene cyclase/phytoene synthase activities, partially complements this mutation and restores a minimal amount of β-carotene production. In MS12 transformants, the accumulation of lycopene and γ-carotene at levels three to seven times higher than in ATCC 1216b suggests that carB and carRA expression is in some manner different. Extra copies of carB do not increase carotenoid production, but additional copies of carRA do. This effect could be due to a pALBT119 (carRA)/pALBT120 (carB) ratio of 20:1.

At present, β-carotene is produced commercially by chemical synthesis. We are now using a new industrial process with B. trispora to produce β-carotene. Although neither gene number nor gene sequence in B. trispora can yet be altered by transformation, the carB and carRA sequences described here can be used to guide the development of overproducing strains that are altered either in these genes themselves or in other genes that affect their expression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants FIT-010000-2001-132 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology and QLRT-2000-00780 from the Fifth Framework of the European Commission. B. Paz was supported by a fellowship, Acción MIT-F2, from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology.

We thank A. P. Eslava for M. circinelloides strains and pEPM9, S. Torres-Martínez for pLeu4, and M. Sandoval, P. Merino, C. Alonso, and E. G. Quiñones for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnau, J., and P. Strøman. 1993. Gene replacement and ectopic integration in the zygomycete Mucor circinelloides. Curr. Genet. 23:542-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrach, N., R. Fernández-Martín, E. Cerdá-Olmedo, and J. Ávalos. 2001. A single gene for lycopene cyclase, phytoene synthase and regulation of carotene biosynthesis in Phycomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1687-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. Moore, J. A. Smith, J. G. Seidman, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 5.Balance, D. J. 1986. Sequences important for gene expression in filamentous fungi. Yeast 2:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartley, G. E., T. J. Schmidhauser, C. Yanofsky, and P. A. Scolnik. 1990. Carotenoid desaturases from Rhodobacter capsulatus and Neurospora crassa are structurally and functionally conserved and contain domains homologous to flavoprotein disulfide oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 265:16020-16024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauernfeind, J. C. 1981. Carotenoids as colorants and vitamin A precursors: technical and nutritional applications. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Benito, E. P., V. Campuzano, M. A. López-Matas, J. I. De Vicente, and A. P. Eslava. 1995. Isolation, characterization and transformation, by autonomous replication, of Mucor circinelloides OMPdecase-deficient mutants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248:126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britton, G. 1983. The biochemistry of natural pigments. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 10.Britton, G., S. Liaaen-Jensen, and H. Pfander. 1998. Carotenoids. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland.

- 11.Carattoli, A., C. Cogoni, G. Morelli, and G. Macino. 1994. Molecular characterization of upstream regulatory sequences controlling the photoinduced expression of the albino-3 gene of Neurospora crassa. Mol. Microbiol. 13:787-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerdá-Olmedo, E. 1987. Carotene, p. 199-222. In E. Cerdá-Olmedo and E. D. Lipson (ed.), Phycomyces. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 13.Costa, J., A. T. Marcos, J. L. de la Fuente, M. Rodríguez-Sáiz, B. Díez, E. Peiro, W. Cabri, and J. L. Barredo.August 2003. Method of producing β-carotene by means of mixed culture fermentation using (+) and (−) strains of Blakeslea trispora. International patent WO 03/064673.

- 14.Dailey, T. A., and H. A. Dailey. 1998. Identification of an FAD superfamily containing protoporphyrinogen oxidases, monoamine oxidases, and phytoene desaturase. Expression and characterization of phytoene desaturase of Myxococcus xanthus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13658-13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrenshaft, M., and M. E. Daub. 1994. Isolation, sequence, and characterization of the Cercospora nicotianae phytoene dehydrogenase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2766-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gribskov, M., J. Devereux, and R. R. Burgess. 1984. The codon preference plot: graphic analysis of protein coding sequences and prediction of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kjœrulff, S., D. Dooijes, H. Clevers, and O. Nielsen. 1997. Cell differentiation by interaction of two HMG-box proteins: Mat1-Mc activates M cell-specific genes in S. pombe by recruiting the ubiquitous transcription factor Ste11 to weak binding sites. EMBO J. 16:4021-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampila, L. E., S. E. Wallen, and L. B. Bullerman. 1985. A review of factors affecting biosynthesis of carotenoids by the order Mucorales. Mycopathologia 90:65-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasker, B. A., and P. T. Borgia. 1980. High frequency heterokaryon formation by Mucor racemosus. J. Bacteriol. 141:565-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, P. C., and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2002. Metabolic engineering towards biotechnological production of carotenoids in microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linden, H., P. Ballario, and G. Macino. 1997. Blue light regulation in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 22:141-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linnemannstöns, P., M. M. Prado, R. Fernández-Martín, B. Tudzynski, and J. Ávalos. 2002. A carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster in Fusarium fujikuroi: the genes carB and carRA. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267:593-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathews, D. H., J. Sabina, M. Zuker, and D. H. Turner. 1999. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 288:911-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta, B., and E. Cerdá-Olmedo. 1995. Mutants of carotene production in Blakeslea trispora. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 42:836-838. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta, B. J., I. N. Obraztsova, and E. Cerdá-Olmedo. 2003. Mutants and intersexual heterokaryons of Blakeslea trispora for production of β-carotene and lycopene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4043-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolás, F. E., S. Torres-Martínez, and R. M. Ruiz-Vázquez. 2003. Two classes of small antisense RNAs in fungal RNA silencing triggered by non-integrative transgenes. EMBO J. 22:3983-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roncero, M. I. G., L. P. Jepsen, P. Strøman, and R. van Heeswijck. 1989. Characterization of a leuA gene and an ARS element from Mucor circinelloides. Gene 84:335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz-Hidalgo, M. J., A. P. Eslava, M. I. Álvarez, and E. P. Benito. 1999. Heterologous expression of the Phycomyces blakesleeanus phytoene dehydrogenase gene (carB) in Mucor circinelloides. Curr. Microbiol. 39:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Hidalgo, M. J., E. P. Benito, G. Sandmann, and A. P. Eslava. 1997. The phytoene dehydrogenase gene of Phycomyces: regulation of its expression by blue light and vitamin A. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:734-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Schmidhauser, T. J., F. R. Lauter, M. Schumacher, W. Zhou, V. E. A. Russo, and C. Yanofsky. 1994. Characterization of al-2, the phytoene synthase of Neurospora crassa: cloning, sequence analysis and photoregulation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12060-12066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidhauser, T. J., F. R. Lauter, V. E. A. Russo, and C. Yanofsky. 1990. Cloning, sequence and photoregulation of al-1, a carotenoid biosynthetic gene of Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5064-5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Specht, C. A., C. C. DiRusso, C. P. Novotny, and R. C. Ullrich. 1982. A method for extracting high-molecular-weight deoxyribonucleic acid from fungi. Anal. Biochem. 119:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutter, R. P. 1970. Effect of light on beta-carotene accumulation in Blakeslea trispora. J. Gen. Microbiol. 64:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutter, R. P., and M. E. Rafelson. 1968. Separation of β-factor synthesis from stimulated β-carotene synthesis in mated cultures of Blakeslea trispora. J. Bacteriol. 95:426-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velayos, A., A. P. Eslava, and E. A. Iturriaga. 2000. A bifunctional enzyme with lycopene cyclase and phytoene synthase activities is encoded by the carRP gene of Mucor circinelloides. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:5509-5519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velayos, A., J. L. Blasco, M. I. Álvarez, E. A. Iturriaga, and A. P. Eslava. 2000. Blue-light regulation of phytoene dehydrogenase (carB) gene expression in Mucor circinelloides. Planta 210:938-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verdoes, J. C., N. Misawa, and A. J. J. van Ooyen. 1999. Cloning and characterization of the astaxanthin biosynthetic gene encoding phytoene desaturase of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 63:750-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdoes, J. C., P. Krubasik, G. Sandmann, and A. J. J. van Ooyen. 1999. Isolation and functional characterisation of a novel type of carotenoid biosynthetic gene from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]