Abstract

This work reports the utilization of an in vivo expression technology system to identify in vivo-induced (ivi) genes in Yersinia ruckeri after determination of the conditions needed for its selection in fish. Fourteen clones were selected, and the cloned DNA fragments were analyzed after partial sequencing. In addition to sequences with no significant similarity, homology with genes encoding proteins putatively involved in two-component and type IV secretion systems, adherence, specific metabolic functions, and others were found. Among these sequences, four were involved in iron acquisition through a catechol siderophore (ruckerbactin). Thus, unlike other pathogenic yersiniae producing yersiniabactin, Y. ruckeri might be able to produce and utilize only this phenolate. The genetic organization of the ruckerbactin biosynthetic and uptake loci was similar to that of the Escherichia coli enterobactin gene cluster. Genes rucC and rupG, putative counterparts of E. coli entC and fepG, respectively, involved in the biosynthesis and transport of the iron siderophore complex, respectively, were analyzed further. Thus, regulation of expression by iron and temperature and their presence in other Y. ruckeri siderophore-producing strains were confirmed for these two loci. Moreover, 50% lethal dose values 100-fold higher than those of the wild-type strain were obtained with the rucC isogenic mutant, showing the importance of ruckerbactin in the pathogenesis caused by this microorganism.

Intensive aquaculture has led to an increase in the problems associated with infectious diseases in farmed fish. Yersiniosis, or enteric redmouth disease, is among the most widespread and causes economic losses all over the world. Its causative agent is the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia ruckeri, which mainly infects salmonids. This is a highly homogeneous species, but several serogroups have been identified (41), O1 being the most virulent. Carrier fish are the prime source of infection by shedding bacteria from their intestine, and transmission is also favored by the capacity of most wild strains to survive and remain infective in the aquatic environment (54), sometimes forming biofilms (13). Although fish are generally treated with inactivated whole-cell vaccines, outbreaks still occur under severe stress or poor hygiene conditions. Moreover, commercial vaccines do not confer protection against a new serogroup recently isolated in southern England (3).

Despite the importance of this syndrome, there is little information about the precise pathogenic mechanisms by which this bacterium is able to defeat the host defenses and cause disease. Until now, the only molecule whose involvement in virulence has been proved is the protease Yrp1 (20, 21), but it is only produced by Azo+ strains (47). Previously, Romalde et al. (42) showed that the extracellular products of Y. ruckeri, which included lipase, protease, and cytotoxic and hemolytic activities, reproduce some characteristic symptoms of this pathology, such as hemorrhage in the mouth and intestine. Besides, they proved the ability of Y. ruckeri to adhere to and effectively invade fish cell lines cultured in vitro. Other reports describe the production of a phenolate siderophore by this pathogen (40), as well as four iron-regulated outer membrane proteins (16). All these molecules are known to be important virulence factors in other microorganisms and could therefore constitute an interesting field of research.

Iron acquisition is a prerequisite for a successful colonization and invasion of many microbial pathogens (for a review, see references 19 and 59). Siderophores are small iron-chelating molecules and can be divided into three major classes, catecholates, hydroxamates, and heterocyclic compounds. In contrast to other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, pathogenic Yersinia species (mouse-virulent Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica biogroup 1B) do not produce either catecholate or hydroxamate siderophores. However, they are provided with uptake systems for both of them. The only siderophore that these strains are able to produce and utilize is the heterocyclic compound yersiniabactin, which has been related to pathogenicity.

Laboratory media appear to be a limited tool when trying to study the molecular mechanisms of disease, since it is very difficult to mimic the complex and changing environment of the host. In an attempt to overcome these limitations, Mahan et al. (32) developed a genetic selection device called in vivo expression technology. This technique is actually a promoter trap that uses the host as a selection medium, allowing the identification of genes expressed during infection but not under laboratory conditions. The in vitro expression approach has been successfully applied in other microorganisms (1) and has led to the discovery of novel virulence genes whose mutation produce an attenuation of the parental strain, for instance, the putative iron transport system SitABCD of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (29) or a transcriptional regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (56). Originally, it was based on the in vivo complementation of purine auxotrophy (32), but later a new system based on antibiotic resistance was developed (33). This adaptation facilitates the use of this technique in many other pathogen-host systems with no need for identification of attenuating auxotrophies. For this reason, the vector pIVET8 (33) has been chosen to select gene fusions expressed specifically in fish tissues. This plasmid has promoterless cat and lacZY genes, which permit the selection of active promoters either in vivo or in vitro. In addition, the use of a suicide plasmid not only eliminates the high-copy-number effect of a replicative vector, but also avoids the risk of gene disruption of transposon insertion fusions.

In this paper, we report the optimization of an in vivo selection system for a fish-pathogenic species as well as the identification and sequencing of 14 ivi (in vivo-induced) genetic loci. It also shows a deeper analysis of those related to iron acquisition and tests the involvement in virulence of two of them. Moreover, it confirms the production and utilization of a virulence-involved catecholate siderophore by Y. ruckeri.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. For the routine culture of Escherichia coli strains, 2×TY (tryptone/yeast) broth and agar were used, whereas Y. ruckeri strains were grown on either nutrient broth (NB), nutrient agar (NA), or eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar (Pronadisa). If required, the following compounds were added to the media: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), rifampin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), 2,2′-dipyridyl (100 μΜ), or FeCl3 (100 μΜ). Incubations were at 37°C for E. coli and 18 or 28°C for Y. ruckeri, with orbital shakers at 250 rpm. For the detection of siderophore production, chrome azurol S (CAS) plates and low-iron minimal medium M9 were prepared as described by Barghouthi et al. (4) and Romalde et al. (40), respectively. All glassware used to prepare these two media was first treated with 1 M HCl to remove iron traces and rinsed with water.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Yersinia ruckeri | ||

| 150 | Trout isolate, virulent strain | 47 |

| 150R | Rifr derivative of 150 | 20 |

| 150R ivi I-XIV | Strains containing ivi fusions expressed only in the host | This study |

| 150RrucC | RifrrucC::pIVET8 Apr | This study |

| 150RrupG | RifrrupG::pIVET8 Apr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5αλpir | F′ endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) | 58 |

| SM10λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu Km::λpir | 50 |

| S17-1λpir | λ(pir) hsdR pro thi RP4-2 Tc::Mu Km::Tn7 | 50 |

| S17-1λpir iviI-iviXIV | E. coli strains carrying iviI-XIV plasmids | This study |

| MT1694 | HB101 derivative containing pRK2013 | 37 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIVET8 | AproriR6K mob+ promoterless cat-lacZY | 33 |

| pRK2013 | Tra+ Kmr | 22 |

| pLPY3 | pIVET8::BglII (entC), Apr | This study |

| pLPY4 | pIVET8::BglII (fepG), Apr | This study |

Genetic techniques.

Routine DNA manipulation was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (44). Phage T4 DNA ligase and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Roche Ltd., restriction enzymes were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd., and oligonucleotides were from Sigma Aldrich Co.

A genomic library was constructed by ligating BglII-digested and dephosphorylated pIVET8 with Y. ruckeri 150 chromosomal DNA partially digested with Sau3AI and size fractionated in a sucrose gradient (20). The fractions selected for ligation had an average fragment size of 3 to 5 kb. The resulting ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5αλpir. Pooled plasmid DNA was extracted and used to transform E. coli SM10λpir, from which the library was transferred to Y. ruckeri by filter mating (20). The transconjugants were pooled and conserved in 25% glycerol at −70°C.

Experimental infections.

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) weighing from 10 to 15 g were kept in 60-liter tanks at 18 ± 1°C in continually flowing dechlorinated water. Six groups of 30 fish were injected intraperitoneally with doses of 104 transconjugant cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. At 24 and 48 h postinfection, fish were given intramuscular injections of 50 μl of 6-mg/ml chloramphenicol; 72 h postinfection, the animals were sacrificed and dissected, and the liver, spleen, and intestine were homogenized in NB with a stomacher. Afterwards, the pool of bacteria was grown in NB supplemented with ampicillin plus rifampin and used for a second round of infection in the same conditions.

Analysis of ivi clones.

Lac− clones recovered in EMB plates after the second round of infection were selected for further analysis. Plasmid DNA was recovered from Y. ruckeri chromosome by triparental mating (37). Briefly, cultures of the Y. ruckeri fusion-containing strain, an E. coli π+ recipient (S17-1λpir), and an E. coli strain harboring a helper plasmid (pRK2013) that encodes Tra were mixed in equal amounts (100 μl of overnight cultures), pelleted, plated onto a 2×TY plate, and incubated at 28°C for 6 h. Transconjugants were selected in plates with both ampicillin and streptomycin at the concentrations mentioned above. Plasmid DNA obtained from the resulting strains was digested with BamHI to differentiate allelic groups. The nucleotide sequences upstream of the cat and bla genes was sequenced with the initial primers catseq-2 (5′-CGGTGGTATATCCAGTG-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 31 to 15 of the cat gene) and blaseq (5′-GGGAATAAGGGCGACAC-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 36 to 20 of the bla gene). Subsequent primers were derived from ivi sequences. For gene rucC, a degenerate reverse primer called rucCRP (5′-ACNACCCAYTCNCCRTT-3′) was designed from homologous proteins in order to obtain more of the coding sequence (N is A, C, G, or T; Y is C or T; R is A or G). It was used to perform a PCR with forward primer rucCFP (5′-TCACGGGCGGTAGAAAC-3′) (Ta = 47°C, te = 1 min). An amplicon of about 600 bp was obtained and sequenced.

DNA sequencing was performed by the dideoxy chain termination method with the DR Terminator kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions in an ABI Prism 310A automated DNA sequencer from Perkin-Elmer. Sequences were compared to those in the databases with the Blastx program. For promoter activity studies, the iviII and iviIII clones were grown in M9, M9 supplemented with 2,2′-dipyridil, or M9 supplemented with FeCl3 at either 18 or 28°C. Samples from stationary-phase cultures were collected, and β-galactosidase activity was measured as described by Miller (34). After an analysis of variance test, P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Construction and analysis of insertion mutants.

Internal fragments of the predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of rucC (449 bp) and rupG (604 bp) were amplified by PCR with the following primers: forward primers rucC1 and rupG1 (5′-GCCAAGATCTCGTAGTTTGCCGAACGA-3′, nucleotides 361 to 377 in bold type, and 5′-GCCAAGATCTGCTACGATGGCGCTGAT-3′, nucleotides 238 to 255 in bold type), respectively, and reverse primers rucC2 and rupG2 (5′-CGTTAGATCTTGAATGAGTGATGGCTG-3′, nucleotides 809 to 793 in bold type, and 5′-CGTTAGATCTGTGCGGCCAGTGCAATA-3′, nucleotides 841 to 824 in bold type), respectively. The reaction was performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9700 GeneAmp thermocycler with an initial denaturation cycle at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 46 and 49°C for rucC and rupG, respectively, for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min), and a final 7-min elongation step at 72°C. All primers contained a BglII site (italic) and four additional bases at their 5′ end. The amplicons generated were digested with BglII and ligated into pIVET8 previously digested with the same enzyme and dephosphorylated.

The ligation mixture was used to transform electrocompetent cells of E. coli SM10λpir. Clones containing inserts were used to conjugate with Y. ruckeri 150R to obtain the mutants as previously described (20). These mutations were, then confirmed by Southern blot analysis after digestion of genomic DNA from mutant and wild-type strains with BamHI. The amplicons mentioned above were used as probes. Mutant clones were tested for their production of siderophores in CAS-agar plates as well as by the Arnow assay (2). Afterwards, 50% lethal dose (LD50) tests of both wild-type and mutant strains were carried out as described by Fernández et al. (20) to determine the involvement in virulence of the genes tested. Briefly, groups of 10 fish (Oncorhynchus mykiss) weighing between 8 and 10 g were kept in 60-liter tanks at 18 ± 1°C. They were challenged by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 ml of serial 10-fold dilutions as described by Fernandez et al. (20). The LD50 determinations were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (38).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence accession numbers for the iviI to iviXIV genes in the GenBank database are AY576529 to AY576542, respectively.

RESULTS

Isolation of transcriptional fusions induced in vivo.

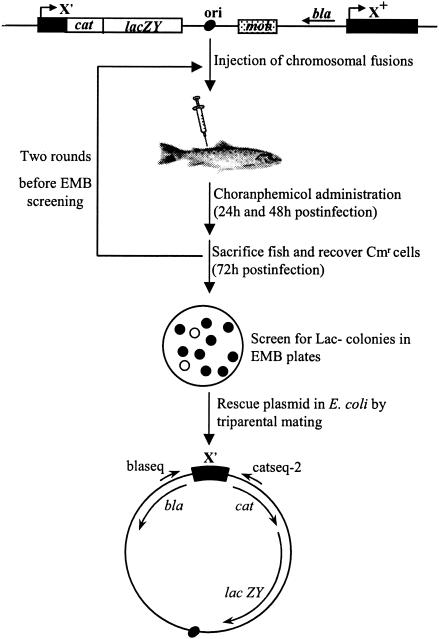

Fragments with an average size of 3 to 5 kb were ligated into the single BglII site of pIVET8. The ligation mixture was then electroporated into E. coli DH5αλpir, and at least 67,000 individual transformants were pooled. Randomly selected clones were checked, showing that about 85% of the population contained inserts. Plasmid DNA obtained from the pool was transformed into E. coli SM10λpir, and the library was then transferred to Y. ruckeri 150R by means of filter mating. Since Y. ruckeri lacks the Pi protein necessary for the replication of pIVET8, transconjugants should have integrated the plasmid in their chromosome by a single-crossover recombination, with the cloned bacterial DNA as a source of homology (Fig. 1). About 300,000 individual exconjugants were obtained in 10 independent conjugation experiments.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of in vitro expression selection in fish. Approximately 104 cells of Y. ruckeri transcriptional fusions were injected intraperitoneally in rainbow trout (O. mykiss). At 24 and 48 h postinfection, chloramphenicol (6 mg/ml) was injected intramuscularly, and the fish were sacrificed 24 h later. Bacterial cells were recovered from fish tissue, and a new round of infection was carried out. Then, cells were plated on EMB, and Lac− colonies were identified. Triparental mating was used for plasmid rescue from the ivi clones, and sequencing of the cloned fragments was carried out with primers blaseq and catseq-2 from the contiguous bla and cat genes, respectively.

These 10 independent pools were used for experimental infections as described above. The ability of chloramphenicol to select active promoters in vivo was tested by the increase in Lac+ colonies after two rounds of infection, which is known as the red shift (32, 33). The average percentage of Lac− colonies in the transconjugants pool was 57.5%, whereas it fell to 1.5% after the second passage through fish. In the 10 experiments, a total of 70 ivi clones were isolated.

Analysis of ivi clones.

Clones were rescued from the Y. ruckeri chromosome through triparental mating with E. coli S17-1λpir as a recipient strain. Afterwards, plasmid DNA from the different clones was obtained and analyzed after digestion with BamHI. This allowed classification into 14 allelic groups. The sequence of fragments 400 to 600 bp upstream of cat gene (Fig. 1) was determined and compared with the sequences in the databases in all six reading frames by the Blastx program (Table 2). Not surprisingly, all of them were novel sequences, since only a few genes have been sequenced in this pathogen.

TABLE 2.

In vivo-induced Y. ruckeri genesa

| Gene | Database homology (accession no.) | Predicted function | Amino acid identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| iviI | Fct/Erwinia chrysanthemi (Q47162) | Ferrichrysobactin receptor precursor | 52 |

| iviII | EntC/MenF/Chromobacter violaceum (NP_901155) | Isochorismate synthase | 42 |

| iviIII | FepC/Y. enterocolitica (AAD29087) | Putative transport protein | 80 |

| iviIV | Hypothetical protein/E. coli (NP_753126) | Putative hemagglutinin or hemolysin | 49 |

| iviV | ShlB/Serratia marcescens (P15321) | Hemolysin activator protein | 48 |

| iviVI | No significant similarity | ||

| iviVII | TonB complex protein/Y. pestis (NP_670792) | Transport of small molecules | 74 |

| iviVIII | No significant similarity | ||

| iviIX | TctC/P. luminescens (NP_930410) | Tricarboxylic transport | 74 |

| iviX | Hypothetical protein/E. coli (NP_755736) | Putative inner membrane protein | 60 |

| iviXI | No significant similarity | ||

| iviXII | TraI/Serratia entomophila (NP_938092) | Relaxase | 57 |

| iviXIII | TadD-like protein/Y. pestis (NP_670787) | Required for aggregation | 54 |

| iviXIV | YdhC-like/Y. pestis (NP_405925) | Putative drug resistance protein | 54 |

Only those open reading frames in the same strand as cat-lacZY were taken into account. Genes listed in this table are the ones immediately upstream of the cat gene in each clone.

Four of these clones (iviI, iviII, iviIII, and iviVII) contained putative ORFs which showed high homology with genes involved in iron uptake through siderophores in other microorganisms. They were analyzed more deeply in order to characterize this system in Y. ruckeri as well as its involvement in virulence.

iviIV, iviV, iviXII, and iviXIII had significant similarity to genes whose products have been related to virulence in other bacteria, a putative hemagglutinin or hemolysin, a hemolysin activator protein, a putative type IV secretion system, and proteins involved in tight adherence, respectively. Thus, the deduced iviIV translational product had significant homology with members of the ShlA/HecA/FhaA exoprotein family, such as a putative E. coli protein (NP_753126), a putative Y. pestis hemagglutinin-like secreted protein (NP_669014), and Erwinia chrysanthemi hemolysin/hemagglutinin-like protein HecA (39), with 49, 46, and 33% identity, respectively. The iviV locus showed 48, 48, and 38% identity with hemolysin secretion/activation proteins such as Serratia marcescens ShlB (36), Photorhabdus luminescens PhlB (7), and Edwardsiella tarda EthB (26). iviXII showed 57 and 53% identity with the relaxase TraI from Serratia entomophila (27) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (31) and 31% with DotC from Legionella pneumophila (55). The iviXIII ORF had the highest homology with proteins involved in tight adherence such as a hypothetical TadD-like protein from Y. pestis (NP_670787) and TadD from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (30) and Pasteurella multocida (NP_245783), having 54, 47, and 46% amino acid identity, respectively.

Other ivi genes (iviIX, iviX, and iviXIV) had similarity with genes not related to virulence or putative translational products not studied yet. Thus, iviIX showed high homology with the TctC protein of the tripartite tricarboxylate transporter family, such as those of P. luminescens (NP_930410), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (NP_461712), and Pseudomonas putida (NP_743576), with 74, 77, and 71% identity, respectively. iviX had a significant similarity with hypothetical transmembrane proteins from E. coli (NP_755736), Shigella flexneri (NP_708914), and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (NP_462152), having 60, 60, and 59% identity, respectively. The iviXIV locus was similar to several putative drug resistance proteins such as those from E. coli (17), P. luminescens (NP_929842), and Y. pestis (NP_405925), with 55, 54, and 45% amino acid identity, respectively.

Finally, there were three clones (iviVI, iviVIII, and iviXI) with no significant homology to known sequences on the minus strand.

Genetic organization of Y. ruckeri genes involved in siderophore-mediated iron uptake.

As mentioned above, some of the in vivo-induced genes (iviI, iviII, iviIII, and iviVII) isolated in Y. ruckeri might be involved in iron acquisition by a catechol siderophore. Following an initial screening of the genes directly upstream of the reporter cat-lacZY cassette, further sequencing analysis was carried out in order to identify the presence and relative location of other genes essential in siderophore-mediated iron uptake.

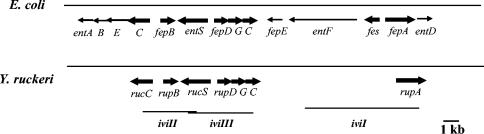

Partial sequence analysis upstream of the cat gene (Fig. 2) in the fragment cloned in iviI showed the presence of a gene (rupA) encoding a putative protein with significant similarity to TonB-dependent receptors. It had the highest homology, 52%, with the ferrichrysobactin receptor Fct from Erwinia chrysanthemi (45), which, despite being a catechol siderophore receptor, showed greater similarity with receptors of hydroxamate chelators than with those of other catecholates such as E. coli enterobactin. So does the Y. ruckeri putative receptor, which is 46 and 42% homologous to the ferrioxamine B receptor FoxA from Y. enterocolitica (5) and ferrichrome-iron receptor FhuA from E. coli (15), respectively.

FIG. 2.

Genetic organization of iviI, iviII, and iviIII clones from Y. ruckeri containing the ruckerbactin biosynthetic uptake cluster, and comparison with the E. coli enterobactin gene cluster. Thick arrows represent genes identified in both microorganisms.

The putative translational product of the sequence just upstream of cat in iviII (Fig. 1) showed high homology with isochorismate synthases, the enzymes that catalyze the first step in the biosynthetic pathway of catechol siderophores. The cloned fragment plus an additional 600 bp amplified by PCR allowed us to identify the initial 338 amino acids of a protein (RucC) highly homologous to EntC from Chromobacterium violaceum (NP_901155), Brucella suis (NP_699223), and E. coli (AAB40793), with 50, 46, and 44% identity, respectively. The sequence upstream of rucC was obtained, revealing the presence of a gene homologous to fepB (rupB), and the deduced initial 115 amino acids of this protein showed 58, 58, and 56% identity with FepB from C. violaceum (NP_901909), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (NP_455170), and E. coli (NP_308658), respectively. The FepB protein binds the siderophore and delivers the ligand to the corresponding inner membrane permease complex.

The initial analysis of iviIII revealed the presence of a putative ORF encoding one of the components of an ABC transporter system responsible for the mobilization of the iron-siderophore complex from the periplasm into the cytoplasm. The product of this gene (rupC) had the highest homology with FepC from Y. enterocolitica (46) and C. violaceum (NP_901904) and Vibrio cholerae ViuC (60), with 80, 63, and 58% identity, respectively. The deduced sequence of the initial 146 amino acids contained one of the two conserved amino acid motifs characteristic of the ATP-binding component of this type of transporter, known as Walker motif A, GPNACGKS (amino acids 48 to 55). It had only one residue different from that of E. coli (A instead of G) and was identical to that of Y. enterocolitica. The second ORF encoded a protein (RupG) homologous to FepG from Y. enterocolitica (46), E. coli (NP_286316), and C. violaceum (NP_901905) with 60, 48, and 46% identity, respectively.

The next ORF (rupD) encoded a protein similar to the third component of this type of transporter, FepD. It showed 80, 53, and 53% identity with FepD from Y. enterocolitica (46), E. coli (NP_286317), and S. flexneri (NP_706446), respectively. These two proteins, FepG and FepD, form the integral membrane permease complex that transports the siderophore across the inner membrane. It is likely that these three genes (rupDGC) are transcribed as a single operon encoding the ruckerbactin transport complex. Upstream of fepD (Fig. 2) but in the opposite orientation, another ORF was found. It has only been sequenced partially, showing 65% amino acid identity with the initial 61 amino acids of a probable POT family transport protein from C. violaceum (NP_901907) and P43 from S. flexneri (NP_706447) and E. coli (49). This kind of protein has recently been proven to be involved in enterobactin secretion to the extracellular environment and has been designated EntS (24).

The iviVII predicted ORF would encode a protein belonging to the TonB complex, necessary to provide the energy for iron transport at the outer membrane. The percentage of identity was 74, 69, and 68% to ExbB from Y. pestis (35), E. coli (18), and S. flexneri (51), respectively. In summary, sequence analysis of these four clones revealed the presence of genes responsible for ruckerbactin biosynthesis (rucC), secretion (rucS), reception (rupA), periplasmic binding (rupB), transport to the cytoplasm (rupDGC), and energy transduction (exbB). In addition, it disclosed the hypothetical chromosomal location of some of these genes, showing the great similarity to that of enterobactin in E. coli (Fig. 2).

In vitro regulation of rucC and rupDGC by iron and temperature.

The four ivi clones containing genes involved in siderophore-mediated iron uptake were grown in EMB plates with either iron or 2,2′-dipyridyl. All of them were Lac− in the iron-rich medium, but only three of them (iviI, iviII, and iviVII) had strong β-galactosidase activity in the iron-depleted medium. On the contrary, iviIII showed only weak activity in the presence of the chelator.

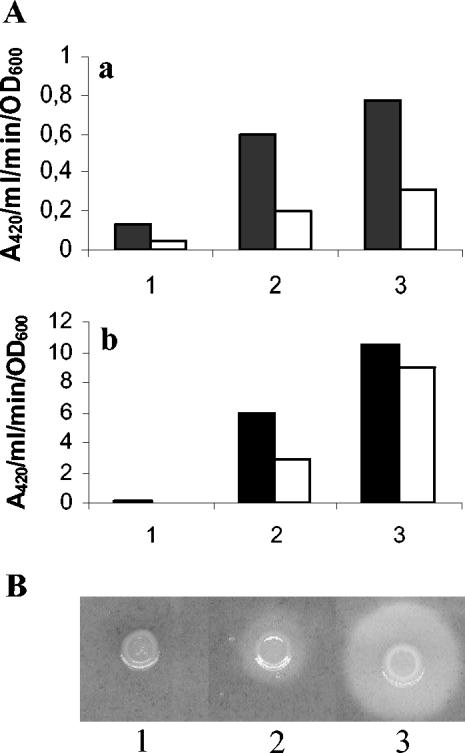

To study these two patterns of iron regulation more deeply, β-galactosidase activity assays were carried out with the rucC(iviII), involved in the biosynthesis of ruckerbactin, and rupDGC(iviIII), the membrane transport components, clones. The results (Fig. 3A, a and b) showed that both operons are regulated by iron availability and temperature. Expression was induced under low-iron conditions, as expected, but in the rupDGC clone (P = 1.31 e−5), the induction was much weaker than in rucC (P = 5.4 e−6). Besides, the expression levels when the growth temperature was 18°C were higher than at 28°C (Fig. 3A, a and b) (P values of 0.009 and 0.04 for rupG and rucC, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Anaysis of rucC and rupDGC loci from the ruckerbactin cluster of Y. ruckeri. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of rupDGC (a) and rucC (b) lacZ fusions was measured in cells grown at 18°C (solid bars) and 28°C (open bars) in minimal medium (M9) containing: FeCl3 (100 μM) (column 1), M9 (column 2), or 2,2′dipyridyl (100 μM) (column 3). The results are the averages of three independent experiments. Note that the data are plotted in different scales. (B) Siderophore production in CAS-agar plates by strains 150RrucC (rucC insertion mutant) (lane 1), 150R (wild type) (lane 2), and 150RrupG (rupG insertional mutant) (lane 3).

Analysis of rucC and rupG mutants and presence of these genes in different Y. ruckeri strains.

Isogenic rucC and rupG mutant strains were obtained, checked by Southern blot analysis, and tested for the production of siderophores in CAS-agar plates. Chromosomal DNA from the wild-type and mutant strains digested with BamHI was analyzed by hybridization with the PCR amplicons from rupG and rucC as probes. Both mutant strains showed a different hybridization pattern from the wild-type strain with the respective probes, confirming that gene interruption had occurred as expected. The CAS-agar plate assay for the production of siderophores showed that the rucC mutant strain did not produce them at all, whereas the rupG mutant had a much larger halo than the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B), indicating ruckerbactin overproduction. Identical results were obtained with the Arnow assay, confirming the catecholic nature of the siderophore activity detected in CAS-agar plates. Thus, the rucC mutant did not have any catecholate in its supernatant after growth in low-iron conditions, whereas the wild-type and rupG mutant strains produced even more of this kind of molecule.

Both mutant strains showed retarded growth compared to the wild-type strain in iron-depleted medium and were unable to reach the same cell density. The maximum optical density was 50% of that of the wild-type strain in the presence of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl. Nevertheless, the mutants behaved differently when assayed for their virulence for fish. The LD50 obtained with the rucC mutant was 100-fold higher than with the wild-type strain (Table 3). In contrast, the LD50 of the rupG mutant was only slightly higher than that of the wild-type strain (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Quantitative infection after intraperitoneal injection of rainbow trout with the parental (150R) and mutant (150RrucC and 150RrupG) strainsa

| Inoculum (100 μl) | No. of fish dead/10 in group

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150R

|

150RrucC

|

150RrupG

|

||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | |

| 107 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| 106 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 10 |

| 105 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 |

| 104 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 103 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LD50 | 2.45 × 104 | 2.83 × 104 | 2.45 × 106 | 2.74 × 106 | 4.87 × 104 | 1.47 × 105 |

LD50 was calculated for each experiment 7 days after the infection by the method of Reed and Muench (38). Groups of 10 fish were injected intraperitoneally with doses ranging from 103 to 107 cells. Columns A and B correspond to dead fish from two independent experiments.

Twelve Y. ruckeri strains (146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 3585, 4319, 1386, 955, 956, A100, and A102) (21, 47) were positive for the production of siderophores in CAS-agar plates. In addition, PCR assays for the detection of rucC and rupG confirmed the presence of these genes in all the strains tested, even though three different plasmid profiles, represented by strains 955, 956, and the rest of the strains, respectively, were analyzed.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial gene expression is, in many cases, a response to specific environmental stimuli. During the pathogen-host interaction, a group of bacterial genes contribute to facilitate colonization, invasion, and definitive infection progression. The expression of some of these genes is enhanced or occurs exclusively in vivo. An in vitro expression strategy based on plasmid pIVET8 (33) was employed as a selection system for promoters induced during the infection of fish by Y. ruckeri. This vector allowed the selection of active promoters in vivo by chloramphenicol treatment and the isolation of those inactive in vitro with the lacZY cassette as a reporter. The most limiting factor in this technique is the determination of the appropriate conditions for antibiotic selection in the host due to the pharmacokinetics of the drug. As this is the first time an in vitro expression system has been used in fish, parameters such as the number of bacteria for intraperitoneal injections, the antibiotic dose for selection, and the organs used for the recovery of bacteria were first established. Before and after two rounds of fish infection, screening on EMB plates indicated the effective selection of active promoters in vivo because of the significant increase in the proportion of Lac+ colonies, a phenomenon known as the red shift (32, 33).

Fourteen loci were selected, and most of them encoded proteins which had homology to known virulence factors from other pathogens. Others were similar to proteins whose involvement in virulence was not known or unclear.

Two loci (iviIV and iviV) encode proteins that belong to the two-partner secretion family that includes several cytolysins and adhesins (28). One (iviV) is homologous proteins involved in the activation and secretion of Serratia-type hemolysins, which form pores not only in erythrocytes but also in fibroblasts and epithelial cells and have been related to invasiveness (25). Both hemolytic and cytotoxic activities have been described in the exocellular products of Y. ruckeri (42) that were able to reproduce some of the symptoms of the disease, such as hemorrhages in the gills and intestine. The other (iviIV) encodes a putative pore-forming toxin of this type, but its function as a hemolysin or as an adhesin is still to be determined.

Another interesting locus is the one encoding a protein similar to TadD (iviXIII), which is involved in the tight adherence properties of A. actinomycetemcomitans and is part of a gene cluster responsible for the synthesis, assembly, and transport of Flp pili. These proteins have been proposed to constitute a new subfamily of type IV secretion systems (6) and seem to be involved in virulence, since a tadD mutant of Pasteurella multocida was reported to be attenuated for virulence in mice (23). Perhaps this system is responsible for the previously described biofilm-forming capacities of some Y. ruckeri strains (13), being necessary to survive in the environment. On the other hand, the in vivo activation of these genes suggests their putative role in adherence to host tissues.

Type IV secretion systems built from core components of conjugation machines and transport proteins or protein-DNA complexes have been demonstrated to be involved in virulence in other microorganisms, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens (43), Helicobacter pylori (14), and Legionella pneumophila (61). iviXII shows homology with the lipoproteins TraI and DotC, involved in secretion systems of this type. Several studies show that the Tra operon is often induced by extracellular or growth phase-dependent signals (for a review, see references 8 and 57). Recently, a conjugative transfer system has also been described in Y. enterocolitica (53).

Metabolic genes induced by the presence of a particular substrate could be selected as ivi genes if the inductor molecule is present in the host and not in the culture medium. This could be the case with the tctC homologue. TctC is part of a tripartite tricarboxylate transporter system that has not been well characterized yet. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium tctC mutants showed poor growth in the presence of citrate, one of the binding substrates of this protein (52). The isolation of an orthologous tctC in Y. ruckeri as an iviIX gene and its induction in vivo suggest that it plays an important role in obtaining a carbon and energy source in the host.

iviX and iviXIV are putative transmembrane proteins whose involvement in transport of molecules such as proteins and metals or in mechanisms of drug resistance is still to be analyzed.

Counterparts of the loci fct (TonB-dependent receptor), entC (isochorismate synthase), fepDGC (ABC transport system), fepB (periplasmic iron-siderophore binding protein), entS (involved in secretion of the siderophore), and exbB (TonB complex component), all involved in iron piracy, were identified in Y. ruckeri. This confirms that this microorganism produces a catechol siderophore (ruckerbactin), as previously suggested by Romalde et al. (40). This system turned out to be similar to that of E. coli enterobactin not only in terms of amino acid sequence homology but also in the chromosomal arrangement of some of these genes. In addition, high homology was found between the ruckerbactin receptor (RupA) and the ferrichrysobactin receptor (Fct) from E. chrysanthemi (45), showing more similarity with hydroxamate receptors than with other catecholate receptor proteins such as FepA from E. coli. This suggests that ruckerbactin is more similar to chrysobactin than to enterobactin in chemical structure.

However, this differs from other pathogenic yersiniae that synthesize only the heterocyclic compound yersiniabactin in spite of its ability to transport and utilize other siderophores belonging to the catecholate and hydroxamate families. For instance, they are endowed with a gene cluster encoding the proteins needed for enterochelin uptake (fepA, fepDGC, and fepB). However, the genes required for enterochelin biosynthesis and secretion seem to have been deleted. All these data, together with the involvement of protease Yrp1 in virulence (20), show that, in terms of pathogenicity mechanisms, Y. ruckeri is closer to E. chrysanthemi than to other yersiniae.

The absence of a halo in CAS-agar plates around the rucC mutant colonies indicates that this is the only high-affinity iron-scavenging system present in this microorganism. In contrast, the rupG mutant strain showed a larger halo than the wild-type strain, indicating overexpression of the siderophore biosynthetic pathway. As expected, rucC and rupG were both upregulated under iron-limited conditions in vitro. This induction was temperature dependent, being higher at 18°C, the infection temperature, than at 28°C, the optimal growth temperature, as occurs with Y. ruckeri protease Yrp1 (20) and other genes from fish pathogens (11, 48). Nevertheless, induction of rupG was weaker than of rucC, in agreement with data published by Christoffersen et al. (9) for E. coli, where expression levels of rupDGC were significantly lower than those of the other enterobactin transcription units. Siderophore production seems to be a conserved character in this species, because 12 strains from different origins were positive in the CAS-agar plate assay. Additionally, PCR analysis showed that rucC and rupG were present in Y. ruckeri strains with three different plasmid profiles, which suggests but does not prove that the ruckerbactin gene cluster is not plasmid borne.

This study has proved that ruckerbactin is one of the iron uptake systems that this pathogen utilizes in the host and is also involved in virulence. First, it confirms that genes involved in the siderophore pathway are upregulated during the infection of fish. On the other hand, the LD50 of a rucC mutant strain was 100-fold higher than that of the wild-type strain. Strikingly, the rupG mutant strain LD50 was similar to that of the wild-type strain despite its retarded growth in vitro in iron-depleted medium, like the rucC mutant. Perhaps this mutant has altered overexpression in other systems able to supply iron in the host, with different sources such as hemoglobin. The connection between siderophores and iron acquisition in the virulence of bacteria is well established (19, 59), and studies on in vivo induction of genes related to iron in fish-pathogenic microorganisms has already been described. Thus, iron limitation during in vivo growth induces the expression of outer membrane proteins in Vibrio salmonicida (10). In the same way, studies carried out in Vibrio anguillarum 01 showed that iron acquisition by siderophore is involved in the virulence of this bacterium (12).

In summary, this study has led to the identification of 14 transcription units specifically induced in the fish pathogen Y. ruckeri during infection. Four of these loci turned out to be part of a catechol-type siderophore system. The chemical structure and biosynthetic route of this molecule, called ruckerbactin, are still to be determined. Most of the remaining genes were identified as putative virulence factors according to their sequence homology with known virulence factors from other pathogens. This work may be the basis for future analysis of these genes in order to have a general picture of the main pathogenicity determinants in this bacterium.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Spanish MCYT (grants AGL2000-0869 and AGL2003-229). L.F. was the recipient of an FPI grant from the MCYT.

We thank M. J. Mahan and J. J. Mekalanos for kindly providing the pRK2013 and pIVET8 plasmids, respectively. We thank A. F. Braña for assistance and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelichio, M. J., and A. Camilli. 2002. In vivo expression technology. Infect. Immun. 70:6518-6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnow, L. E. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylamine-tyrosine mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531-541. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin, D. A., P. A. W. Robertson, and B. Austin. 2003. Recovery of a new biogroup of Yersinia ruckeri from diseased rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barghouthi, S., R. Young, M. O. J. Olson, J. E. L. Arceneaux, L. W. Clem, and B. R. Byers. 1989. Amonabactin, a novel tryptophan- or phenylalanine-containing phenolate siderophore in Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Bacteriol. 171:1811-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bäumler, A. J., and K. Hantke. 1992. Ferrioxamine uptake in Yersinia enteroco litica: characterization of the receptor protein FoxA. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1309-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharjee, M. K., S. C. Kachlany, D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2001. Nonspecific adherence and fibril biogenesis by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: TadA protein is an ATPase. J. Bacteriol. 183:5927-5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brillard, J., E. Duchaud, N. Boemare, F. Kunst, and A. Givaudan. 2002. The PhlA hemolysin from the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens belongs to the two-partner secretion family of hemolysins. J. Bacteriol. 184:3871-3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie, P. J. 2001. Type IV secretion: intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol. Microbiol. 40:294-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christoffersen, C. A., T. J. Brickman, I. Hook-Barnard, and M. A. McIntosh. 2001. Regulatory architecture of the iron-regulated fepD-ybdA bidirectional promoter region in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2059-2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun, D. J., and H. Sorum. 1998. Outer membrane protein expression during in vivo cultivation of Vibrio salmonicida. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 8:367-377. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colquhoun, D. J., and H. Sorum. 2001. Temperature-dependent siderophore production in Vibrio salmonicida. Microb. Pathog. 31:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conchas, R. F., M. L. Lemos, J. L. Barja, and A. E. Toranzo. 1991. Distribution of plasmid- and chromosome-mediated iron uptake systems in Vibrio anguillarum strains of different origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2956-2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coquet, L., P. Cosette, L. Quillet, F. Petit, G. A. Junter, and T. Jouenne. 2002. Occurrence and phenotypic characterization of Yersinia ruckeri strains with biofilm-forming capacity in a rainbow trout farm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:470-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulton, J. W., P. Mason, D. R. Cameron, G. Carmel, R. Jean, and H. N. Rode. 1986. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science 284:1328-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covacci, A., J. L. Telford, G. Del Giudice, J. Parsonnet, and R. Rappuoli. 1999. Protein fusions of β-galactosidase to the ferrichrome-iron receptor of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 165:181-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies, R. L. 1991. Yersinia ruckeri produces four iron-regulated proteins but does not produce detectable siderophores. J. Fish Dis. 14:563-570. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eberhardt, S., G. Richter, W. Gimbel, T. Werner, and A. Bacher. 1996. Cloning, sequencing, mapping and hyperexpression of the ribC gene coding for riboflavin synthase of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 242:712-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eick-Helmerich, K., and V. Braun. 1989. Import of biopolymers into Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequences of the exbB and exbD genes are homologous to those of the tolQ and tolR genes, respectively. J. Bacteriol. 171:5117-5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faraldo-Gomez, J., and M. S. P. Sanson. 2003. Acquisition of siderophores in gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. 4:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández, L., P. Secades, J. R. López, I. Márquez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2002. Isolation and analysis of a protease gene with an ABC transport system in the fish pathogen Yersinia ruckeri: insertional mutagenesis and involvement in virulence. Microbiology 148:2233-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández, L., J. R. López, P. Secades, A. Menéndez, I. Márquez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2003. In vitro and in vivo studies of the Yrp1 protease from Yersinia ruckeri and its role in protective immunity against enteric redmouth disease of salmonids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7328-7335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuller, T. E., M. J. Kennedy, and D. E. Lowery. 2000. Identification of Pasteurella multocida virulence genes in a septicemic mouse model using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microb. Pathog. 29:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furrer, J. L., D. N. Sanders, I. G. Hook-Barnard, and M. A. McIntosh. 2002. Export of the siderophore enterobactin in Escherichia coli: involvement of a 43 kDa membrane exporter. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1225-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hertle, R., M. Hilger, S. Weingardt-Kocher, and I. Walev. 1999. Cytotoxic action of Serratia marcescens hemolysin on human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:817-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirono, I., N. Tange, and T. Aoki. 1997. Iron-regulated haemolysin gene from Edwardsiella tarda. Mol. Microbiol. 24:851-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurst, M. R., M. O'Callaghan, and T. R. Glare. 2003. Peripheral sequences of the Serratia entomophila pADAP virulence-associated region. Plasmid 50:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacob-Dubuison, F., C. Locht, and R. Antoine. 2001. Two-partner secretion in Gram-negative bacteria: a thrifty, specific pathway for large virulence proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 40:306-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janakiraman, A., and J. M. Slauch. 2000. The putative iron transport system SitABCD encoded on SPI1 is required for full virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1146-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kachlany, S. C., P. J. Planet, M. K. Bhattacharjee, E. Kollia, R. DeSalle, D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2000. Nonspecific adherence by Actinobacillus actinomycetem comitans requires genes widespread in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 182:6169-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komano, T., T. Yoshida, K. Narahara, and N. Furuya. 2000. The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1348-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahan, M. J., J. M. Slauch, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1993. Selection of bacterial virulence genes that are specifically induced in host tissues. Science 259:686-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahan, M. J., J. W. Tobias, J. M. Slauch, P. C. Hanna, R. J. Collier, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Antibiotic-based selection for bacterial genes that are specifically induced during infection of a host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:669-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 354. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Perry, R. D., J. Shah, S. W. Bearden, J. M. Thompson, and J. D. Fetherson. 2003. Yersinia pestis TonB: role in iron, heme, and hemoprotein utilization. Infect. Immun. 71:4159-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole, K., E. Schiebel, and V. Braun. 1988. Molecular characterization of the hemolysin determinant of Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 170:3177-3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rainey, P. B., D. M. Heithoff, and M. J. Mahan. 1997. Single-step conjugative cloning of bacterial gene fusions involved in microbe-host interactions. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rojas, C. M., J. H. Ham, W. Deng, J. J. Doyle, and A. Collmer. 2002. HecA, a member of a class of adhesins produced by diverse pathogenic bacteria, contributes to the attachment, aggregation, epidermal cell killing, and virulence phenotypes of Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16 on Nicotiana clevelandii seedlings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13142-13147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romalde, J. L., R. F. Conchas, and A. E. Toranzo. 1991. Evidence that Yersinia ruckeri possesses a high affinity iron uptake system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 80:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romalde, J. L., R. F. Conchas, and A. E. Toranzo. 1993. Antigenic and molecular characterisation of Yersinia ruckeri. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16:411-419. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romalde, J. L., and A. E. Toranzo. 1993. Pathological activities of Yersinia ruckeri, the enteric redmouth (ERM) bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 112:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salmond, G. P. C. 1994. Secretion of extracellular virulence factors by plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 32:181-200. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Sauvage, C., T. Franza, and D. Expert. 1996. Analysis of the Erwinia chrysanthemi ferrichrysobactin receptor gene: resemblance to the Escherichia coli fepA-fes bidirectional promoter region and homology with hydroxamate receptors. J. Bacteriol. 178:1227-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schubert, S., D. Fischer, and J. Heesemann. 1999. Ferric enterochelin transport in Yersinia enterocolitica: molecular and evolutionary aspects. J. Bacteriol. 181:6387-6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Secades, P., and J. A. Guijarro. 1999. Purification and characterization of an extracellular protease from the fish pathogen Yersinia ruckeri and effect of culture conditions on production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3969-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Secades, P., B. Alvarez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2001. Purification and characterization of a psychrophilic calcium induced, growth-phase-dependent metalloprotease from the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2436-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shea, C. M., and M. A. McIntosh. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of the ferric enterobactin transport system: homology to other periplasmic binding protein-dependent systems in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1415-1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smajs, D., and G. M. Weinstock. 2001. The iron- and temperature-regulated cjrBC genes of Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli strains code for colicin Js uptake. J. Bacteriol. 183:3958-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Somers, J. M., G. D. Sweet, and W. W. Kay. 1981. Fluorocitrate resistant tricarboxylate transport mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 181:338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strauch, E., G. Goelz, D. Knabner, A. Konietzny, E. Lanka, and B. Appel. 2003. A cryptic plasmid of Yersinia enterocolitica encodes a conjugative transfer system related to the regions of CloDF13 Mob and IncX Pil. Microbiology 149:2829-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorsen, B. K., Ø. Enger, S. Norland, and K. A. Hoff. 1992. Long-term starvation survival of Yersinia ruckeri at different salinities studied by microscopical and flow cytometric methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1624-1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogel, J. P., H. L. Andrews, S. K. Wong, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279:873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, J., A. Mushegian, S. Lory, and S. Jin. 1996. Large-scale isolation of candidate virulence genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by in vivo selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10434-10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winans, S. C., D. L. Burns, and P. J. Christie. 1996. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 4:64-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodcock, D. M., P. J. Crowther, J. Doherty, S. Jefferson, E. DeCruz, M. Nover-Weidner, S. S. Smith, M. Z. Michael, and M. W. Graham. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:3469-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woolridge, K. D., and P. H. Williams. 1993. Iron uptake mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:325-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wykoff, E. E., A. Valle, S. L. Smith, and S. M. Payne. 1999. A multifunctional ATP-binding cassette transporter system from Vibrio cholerae transports vibriobactin and enterobactin. J. Bacteriol. 181:7588-7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zink, S. D., L. Pedersen, N. P. Cianciotto, and Y. A. Kwaik. 2002. The Dot/Icm type IV secretion system of Legionella pneumophila is essential for the induction of apoptosis in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 70:1657-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]