Abstract

Cell counts of planctomycetes showed that there were high levels of these organisms in the summer and low levels in the winter in biofilms grown in situ in two polluted rivers, the Elbe River and the Spittelwasser River. In this study 16S rRNA-based methods were used to investigate if these changes were correlated with changes in the species composition. Planctomycete-specific clone libraries of the 16S rRNA genes found in both rivers showed that there were seven clusters, which were distantly related to the genera Pirellula, Planctomyces, and Gemmata. The majority of the sequences from the Spittelwasser River were affiliated with a cluster related to Pirellula, while the majority of the clones from the Elbe River fell into three clusters related to Planctomyces and one deeply branching cluster related to Pirellula. Some clusters also contained sequences derived from freshwater environments worldwide, and the similarities to our biofilm clones were as high as 99.8%, indicating the presence of globally distributed freshwater clusters of planctomycetes that have not been cultivated yet. Community fingerprints of planctomycete 16S rRNA genes were generated by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis from Elbe River biofilm samples collected monthly for 1 year. Sixteen bands were identified, and for the most part these bands represented organisms related to the genus Planctomyces. The fingerprints showed that there was strong seasonality of most bands and that there were clear differences in the summer and the winter. Thus, seasonal changes in the abundance of Planctomycetales in river biofilms were coupled to shifts in the community composition.

Biofilms composed of complex communities of algae, bacteria, and invertebrates embedded in extracellular polymeric substances cover all solid surfaces in rivers and have a profound effect on biogeochemical processes by increasing hydrodynamic transient storage of nutrients and the retention of suspended particles (1). We previously investigated the microbial communities in biofilms which were grown in a standardized way in situ on glass plates in two polluted rivers, the Elbe River and the Spittelwasser River, for 1 year. Using culture-independent methods, we showed that beta-proteobacteria were the dominant group in the massively polluted Spittelwasser River at all times (3) and that there were biofilm-specific freshwater clusters that showed distinct seasonal patterns of diversity (4). Clear seasonal peaks of abundance were observed by using fluorescent in situ hybridization for the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium phylum and the Planctomycetales; the latter group accounted for 7 to 10% of the DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) counts in the summer, compared to <2% of the DAPI counts in the winter (4). Since these seasonal changes were observed in both rivers, they seemed to be connected more with the higher temperature and higher abundance of algae in the summer than with differences in the xenobiotic compounds in the two rivers. High levels of Planctomycetales during the production period have also been found in Elbe snow (2) and in a eutrophic lake (23). Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine if these seasonal changes in abundance of planctomycetes in river biofilms were correlated with changes in the species composition of the community, indicating that there were ecologically adapted populations.

The order Planctomycetales belongs to a separate phylum in the domain Bacteria (20, 28, 9) and exhibits special characteristics for cell structure, genetics, and physiology (reviewed in references 7 and 12). Planctomycetes were considered to be solely aquatic microorganisms (23) until they were discovered unexpectedly in soil by culture-independent 16S rRNA methods (16). Meanwhile, they have been found in many habitats (summarized in reference 17), even in the guts of animals (8). So far, four genera, Planctomyces, Pirellula, Gemmata, and Isosphaera, have been validly described (23). Moreover, three Candidatus genera were recently suggested for the not-yet-cultured anaerobic planctomycetes performing anaerobic ammonia oxidation (anammox) (14, 21, 25). Because sequences of Planctomycetales appear in rather small amounts in conventional clone libraries, we developed specific primer pairs in order to obtain clone libraries, as well as community fingerprints consisting solely of members of this group. The primers covered all Planctomyces-, Gemmata-, and Pirellula-related sequences but not the deeply branching anammox group and some other distantly related uncultured organisms. The primers are referred to as planctomycete specific below for the sake of simplicity. A planctomycete-specific clone library was created for each river. The migration behavior of 95 clones from the Elbe River biofilms was compared to bands in the planctomycete community fingerprints by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE). By sequencing matching clones from the Elbe River and randomly chosen clones from both rivers it was possible to obtain phylogenetic information on the majority of TGGE bands and a general overview of the affiliation of river biofilm Planctomycetales.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling site and sampling procedure.

Biofilms were grown in situ on glass plates held by a Plexiglas frame in the Elbe River upstream of the city of Magdeburg, Germany (11°40′E, 54°4′N) and the Spittelwasser River, a highly polluted second-order tributary of the Elbe River in Germany (12°17′E, 52°4′N). Sampling took place approximately monthly from May 1997 until May 1998. The sampling sites and procedure are described in more detail elsewhere (3).

Isolation of DNA and specific amplification and cloning of 16S rRNA genes.

Genomic DNA was extracted by a modified direct lysis procedure as previously described (4, 6).

16S rRNA genes were amplified from the DNA samples of each site separately by using bacterial primers as described previously (4). Comparisons of TGGE patterns of Planctomycetales amplified directly or by nested PCR from biofilm DNA revealed very few differences (data not shown). About equal amounts of these PCR products (11 products from the Elbe River and 9 products from the Spittelwasser River) were mixed prior to specific amplification with primers t-PVC30f (5′-TTTTGACTGACTGA-ACGTTGGCGGCGTGGA-3′) and t-Pla1384r (5′-TTTTGACTGACTGA-GCGGTGTGTACAAGGCTCA-3′), which covered almost the full length of the 16S rRNA gene (Escherichia coli positions 30 to 1402). For improved blue-white screening of transformants both primers contained a nonmatching tail with stop codons and three additional thymidine residues (underlining) to promote ligation (4) (boldface type indicates specifically binding nucleotides). The forward primer had a signature nucleotide (16, 28) at the 3′ end that was specific for most planctomycetes, chlamydiae, and verrucomicrobia. It also contained a mismatch at position 44 (A instead of G) with a number of members of the genus Pirellula, the genus Gemmata, and an uncultured cluster, which could be neglected since the low annealing temperature made selection against these organisms unlikely. The reverse primer targeted almost all planctomycetes; the only exceptions were some uncultured clones and the deeply branching lineage of the anaerobic ammonia oxidation-performing (anammox) planctomycetes. Like the forward primer, it contained the signature nucleotide A at the 3′ end, which resulted in a critical adenosine-cytosine mismatch with other organisms. However, some members of the genus Treponema showed only a weak mismatch.

Five parallel PCR mixtures (20 μl each) contained 1 μl of template (1:100 dilution of the pooled amplified 16S rRNA genes). The PCR mixture and conditions were the same as those described previously (4), except that there was no dimethyl sulfoxide. The specifically amplified PCR products for each river were pooled and purified by gel extraction (QIAquick gel extraction kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Finally, both PCR mixtures were ligated into the linear plasmid vector pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and transformed into competent E. coli JM109 cells by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Screening of clones for insert size and affiliation. Ninety-five transformants were picked for each river. The lysate of the clones (picked clone dissolved in 50 μl of sterile water and incubated at 95°C for 15 min) served as the template for the vector-specific PCR to confirm positive clones, to check the insert size, and to produce the template for subsequent analyses of the clones. A PCR with the pGEM-T-specific primers T7 and Sp6 targeting the bacteriophage-derived promoters was carried out as described previously (4).

PCR for TGGE analysis.

For partial amplification of planctomycete 16S rRNA genes the modified primers GC-BP968f (CGCCCGGGGCGCGCCCCGGGCGGGGCGGGGGCACGGGGGG-AACGCGAAGAACCTTA) containing a GC clamp and Pla1384r (identical to the reverse cloning primer without a tail) were used, which covered E. coli positions 968 to 1402. The forward primer was derived from the TGGE primer GC-968f (18), which targets most bacteria, but was shortened by one base at the 3′ end, which had a strong mismatch with sequences of planctomycetes. A few members of the genera Gemmata and Pirellula had a weak mismatch at the 5′ end of the primer (U instead of A), which could be neglected. Organisms belonging to the genus Isosphaera and some uncultured species might have been excluded. PCR for specific amplification of fragments to be analyzed by TGGE was performed as described previously (4), but the annealing temperature was raised to 64°C. The PCR conditions were optimized by using reference strains with one or more mismatches (data not shown). 16S rRNA genes from biofilm DNA (diluted) were amplified in 50-μl (total volume) mixtures. For specific amplification of the cloned inserts 10 μl was sufficient.

TGGE.

For sequence-specific separation of PCR products, a TGGE system (QIAGEN) was used as described previously (4); a temperature gradient of 35 to 44°C for 6.75 h was used. For screening the river-specific reference pattern (see Fig. 2) was applied to every third or fourth lane. The performance of electrophoresis was controlled by applying a mixture of 16S rRNA fragments from several soil bacteria (6).

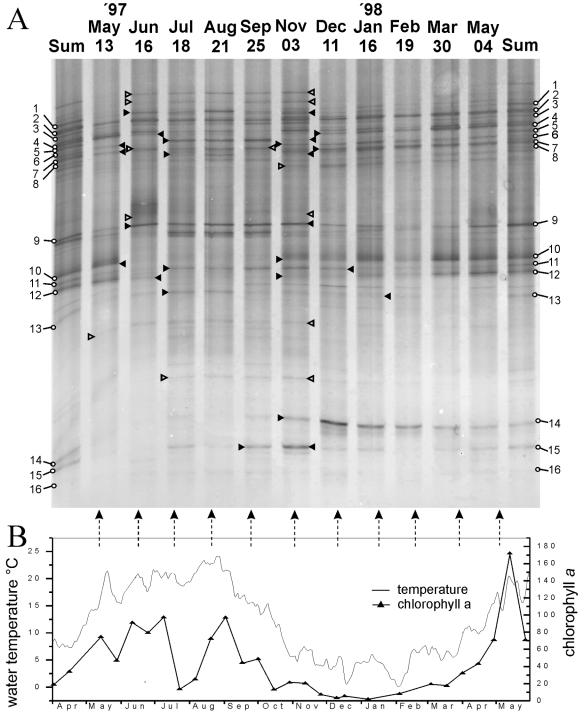

FIG. 2.

(A) Community profiles of members of the Planctomycetales based on specific amplification and TGGE separation of 16S rRNA gene sequences (positions 968 to 1402) from 1-month-old biofilms grown in the Elbe River. The numbers indicate bands for which corresponding clones were found. Sum is an abbreviation for the river-specific reference generated from pooled PCR products from all sampling dates. Dates of sampling are indicated above the lanes. Solid and open arrowheads indicate the seasonal occurrence of bands for which corresponding clones were found and not found, respectively. Arrowheads pointing toward each other indicate occurrences in adjacent months, and arrowheads pointing outward indicate occurrences in nonadjacent time periods. (B) Temperature and chlorophyll a concentration for the Elbe River during the sampling period. The arrows indicate values at the time of sampling. The low chlorophyll concentration in July was caused by a flood.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis.

Of 88 clones with correct insert sizes picked from the Elbe River, 24 clones with matching TGGE patterns and 28 representative clones with fuzzy, smeared, and nonmatching bands were chosen and sequenced. For the Spittelwasser River biofilms, 28 randomly chosen clones were sequenced. Amplified inserts from clones were purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; QIAGEN) and used as templates for the sequencing reaction with primers T7 and Sp6. Inserts were sequenced by the MWG-Biotech custom DNA sequencing service (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). All sequences were checked for chimera formation with the CHECK_CHIMERA software of the Ribosomal Database Project (version 2.7; www.rdp.cme.msu.edu/cgis/chimera.cgi). Five clones from the Elbe River were rejected as chimeras, and seven clones were found to be identical by TGGE and partial sequencing and were not submitted to the EMBL but were included in the analysis (see Fig. 1). Finally, 40 clones from the Elbe River were submitted to the EMBL. In 7 of the 28 previously submitted clones from Spittelwasser River biofilms chimeric ends were identified and removed, and the sequences were updated accordingly.

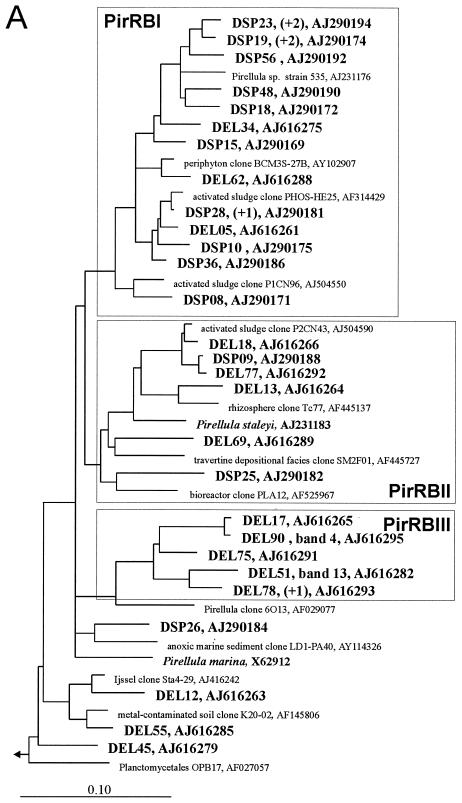

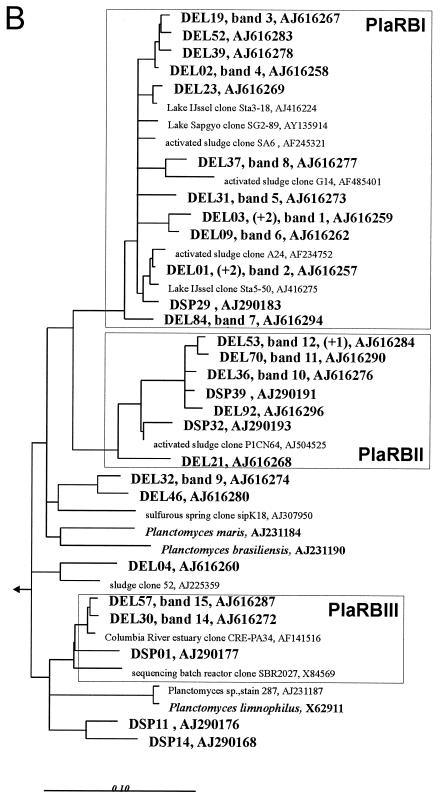

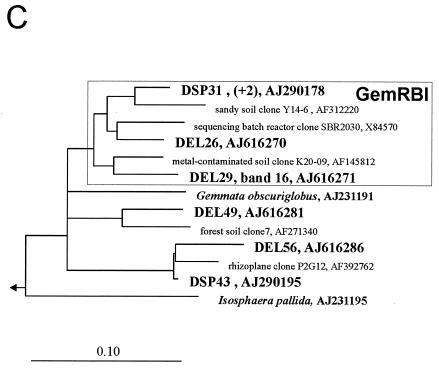

FIG. 1.

Rooted phylogenetic consensus trees for 16S rRNA sequences showing the affiliations of Elbe River (DEL) and Spittelwasser River (DSP) biofilm clones within the Planctomycetales. Scale bars = 10% difference in nucleotide sequence. The outgroups were Brocadia ammoxidans (accession number AF375994), Kuenenia stuttgartiensis (AF375995), Verrucomicrobium spinosum (X90515), and E. coli (X8075) (data not shown). The numbers of identical sequences (levels of similarity, more than 99%) not shown in the trees are indicated in parentheses. Corresponding bands with the community pattern and EMBL accession numbers are indicated. The boxes indicate river biofilm clusters (PirRB, PlaRB, and GemRBI clusters) containing at least three different biofilm clones, together with cultured organisms and related environmental clones (only the closest relatives of biofilm clones are shown). (A) Partial tree showing clusters PirRBI to PirRBIII. (B) Partial tree of the Planctomyces branch showing clusters PlaRBI to PlaRBIII. (C) Partial tree of the Gemmata branch showing cluster GemRBI.

For the first identification and to find the closest relatives, the sequences were submitted to the sequence match program BLAST of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (updated 26 August 2002; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Our sequences, as well as previously published planctomycete sequences (as of February 2003), were imported into an ARB database (release June 2002) of the ARB program package (release 1999; http://www.arb-home.de); more than 600 planctomycete sequences were used. In this database the sequences were automatically aligned and manually corrected. All sequences that were more than 1,290 bp long were selected (a total of 55 sequences), and trees were calculated by using four treeing methods with the appropriate tools embedded in ARB, distance matrix, maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and neighbor joining, by using a majority rule filter for planctomycetes. E. coli and other organisms were used as outgroups. Subsequently, biofilm clone sequences and the remaining most closely related previously published sequences were added to each tree with the parsimony tool without changing the overall tree topology. Finally, a consensus tree was constructed, in which uncertain branching orders were replaced by a multifurcation (Fig. 1).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the EMBL database under accession numbers AJ616257 to AJ616296 and AJ290168 to AJ290195.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Planctomycete community composition.

The planctomycete communities in the small, strongly polluted Spittelwasser River clearly differed from those of the large, moderately polluted Elbe River. About two-thirds (64%) of the clones from the Spittelwasser River were affiliated within the Pirellula branch; 21 and 14% of the clones from the Spittelwasser River were remotely related to Planctomyces and Gemmata, respectively. However, in the Elbe River more than one-half (57%) of the sequences were affiliated with Planctomyces, one-third (34%) belonged to Pirellula, and 9% were affiliated with Gemmata.

As in all PCR-based studies, some limitations and biases have to be considered (reviewed in reference 27). Although chimeras were omitted from this study, the use of specific primers produced high numbers of very closely related sequences, which might have resulted in undetectable chimeras (as observed by Speksnijder et al.[22]). Although the primers excluded some groups of planctomycetes, the study still covered the majority of planctomycete diversity and enhanced the yield of planctomycete clones dramatically, so that many members of this group came to light which might have been overlooked if universal bacterial primers had been used (26). All sequenced clones analyzed belonged to the Planctomycetales, which showed that despite the low annealing temperature used, the PCR was stringent.

While the analysis of the Spittelwasser River clone library was based on randomly selected clones, for the Elbe River clone library random selection was coupled with the preferential sequencing of clones that produced bands in the TGGE fingerprints. As a consequence, Planctomyces-related clones were preferentially sequenced for the Elbe River, because Pirellula- and Gemmata-related clones often produced fuzzy bands or smears. If clones that produced bands matching the TGGE fingerprint were omitted, the proportion of Planctomyces- and Pirellula-related sequences in the Elbe River biofilm clone library was more balanced.

Most clones fell into seven clusters, which were defined as groups of sequences containing at least three biofilm clones and related sequences of environmental clones and isolates. Clusters did not always contain sequences with the same similarity level, but they were stable independent of the treeing method used. The phylogenetic affiliations are shown in Fig. 1. Although about the same number of biofilm clones from the two rivers were related to the genus Pirellula, river-specific subclusters were observed. While cluster PirRBII contained sequences from both the Elbe and Spittelwasser rivers, cluster PirBI was clearly dominated by sequences retrieved from the Spittelwasser River and the deeply branching cluster PirRBIII consisted exclusively of sequences from the Elbe River. Most sequences affiliated with Planctomyces were retrieved from the Elbe River, and thus clusters PlaRBI to PlaRBIII were dominated by sequences from this habitat.

As in many other studies, clones from river biofilms were more closely related to cloned environmental sequences (4, 5) than to cultivated organisms, with the exception of several sequences in cluster PirRBI which had high similarities to Pirellula sp. strain 535. Other than that, the similarities to described species were rather low, ranging from 85 to 92%. The related environmental sequences, a selection of which is shown in Fig. 1, originated mainly from freshwater habitats, but some were also derived from marine or soil habitats. Many of these sequences had relatively high levels of similarity with the biofilm clones, often more than 98% up to 99.8%. Some clusters consisted of sequences retrieved exclusively (PirRBI, PirRBIII, and PlaRBI) or predominantly (PlaRBII) from freshwater habitats with different levels of pollution from distant regions of the world. Therefore, we concluded that they represent globally distributed planctomycetes specifically adapted to the freshwater environment. Globally distributed habitat-specific clusters were also found in other clone library investigations of natural microbial communities, including investigations of freshwater habitats (4, 11, 30, 31), marine environments (reviewed in reference 10), soil (19), and marine sponges (13), and these clusters belong to many different phylogenetic groups. Cultivating organisms which are representative of globally distributed habitat-specific clusters, which in the case of planctomycetes are only distantly related to cultivated genera, will be crucial for understanding their ecology and biogeochemical roles.

Identification of TGGE bands in Elbe River biofilms.

There is currently no alternative to profiling the community composition on high-resolution gels if changes in complex microbial communities need to be analyzed for many samples. Although in principle the biases and limitations of TGGE-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis profiling are known, they can only be tracked down specifically if community profiling is combined with identification of bands, as in this study. Here the migration behavior of the cloned 16S rRNA genes of planctomycetes was compared with bands in the river reference pattern (Sum in Fig. 2) by TGGE. The data show that only a certain fraction of the planctomycete clones, mainly organisms related to the genus Planctomyces, could form a band in the TGGE fingerprints (57% of the 88 clones investigated). About one-half of the latter patterns (25%) matched the community pattern. The remaining clones produced fuzzy bands (26%) or produced only smears on the gel (17%), a phenomenon observed previously (4, 29), which was probably due to the presence of multiple melting domains within the amplified fragments (15). These clones were affiliated predominantly with Pirellula or Gemmata, which were therefore underrepresented on TGGE community fingerprints. However, identification of TGGE bands by sequencing matching clones was possible for practically all major bands in the community fingerprint (Table 1). Only band 4 could not be clearly identified, because clones affiliated with Planctomyces, as well as Pirellula, matched. For some bands several identical clones (>99% similarity) were found, confirming the unambiguous assignment of this band to a single phylotype.

TABLE 1.

Identification of 16S rRNA genes cloned from Elbe River biofilms comigrating with bands in the TGGE community fingerprints, affiliations with river biofilm clusters, and seasonal appearance of corresponding bands

| TGGE band | Clonea | Sequence length | River biofilm cluster | Nearest previously described relative (accession no.) | % Simi- larityb | Origin of sequence | Appearance (strongest)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DEL03 (DEL28, DEL74) | 1235 | PlaRBI | Clone A24 (AF234752) | 94.2 | Activated sludge | P; May-Nov. |

| 2 | DEL01 (DEL08, DEL20) | 1308 | PlaRBI | Clone A24 (AF234752) | 99.4 | Activated sludge | P |

| 3 | DEL19 | 1310 | PlaRBI | Clone SA6 (AF245321) | 95.6 | Activated sludge | P; Feb. weak |

| 4 | DEL02 (DEL71) | 1310 | PlaRBI | Clone SA6 (AF245321) | 97.0 | Activated sludge | May/June; Dec.-May; not definable |

| DEL90 | 1312 | PirRBIII | Clone 6O13 (AF029077) | 89.2 | Marine particulates | May/June; Dec.-May; not definable | |

| 5 | DEL31 | 1313 | PlaRBI | Clone SA6 (AF245321) | 95.6 | Activated sludge | July-Nov. |

| 6 | DEL09 | 1309 | PlaRBI | Clone SA6 (AF245321) | 98.4 | Activated sludge | May 1997; Nov-May 1998 |

| 7 | DEL84 | 1048 | PlaRBI | Clone Sta5-50 (AJ416275) | 96 | Lake Ijssel | May 1997; Dec.-May 1998 |

| 8 | DEL37 | 1307 | PlaRBI | Clone G14 (AF485401) | 95.9 | Activated sludge | July-Nov. |

| 9 | DEL32 | 1301 | Clone sipK18 (AJ307950) | 89.3 | Sulfurous spring | P; June-Nov. | |

| 10 | DEL36 | 1293 | PlaRBII | Clone PICN64 (AJ504525) | 99.4 | Activated sludge | P; May 1997: Nov.-May 1998 |

| 11 | DEL70 | 1293 | PlaRBII | Clone PICN64 (AJ504525) | 98.5 | Activated sludge | P; July-Dec. |

| 12 | DEL53 (DEL54) | 1293 | PlaRBII | Clone PICN64 (AJ504525) | 99.8 | Activated sludge | May/June 1997; Nov.-May 1998 |

| 13 | DEL51 | 1295 | PirRBIII | Clone 6O13 (AF029077) | 88.3 | Marine particulates | P: July-Jan. |

| 14 | DEL30 | 1317 | PlaRBIII | CRE-PA34 (AF141516) | 98.3 | Columbia River estuary | P; Sept.-May |

| 15 | DEL57 | 1293 | PlaRBIII | CRE-PA34 (AF141516) | 98.5 | Columbia River estuary | Sporadic; Sept.-Nov. |

| 16 | DEL29 | 1148 | GemRBI | Clone K20-09 (AF145812) | 97.10 | Contaminated soil | P |

Clones in parentheses were identical clones.

Similarity value for the clone listed first as determined with the Distance Matrix ARB tool by using all available nucleotides.

P, permanent resident.

Some clones with adjacent TGGE bands had high levels of similarity with each other or were affiliated at least in the same cluster (bands 1 to 8 for cluster PlaRBI; bands 10 to 12 for cluster PlaRBII; bands 14 and 15 for cluster PlaRBIII). On the other hand, some clones produced bands that were far apart from each other (bands 4 and 13), even though they were affiliated in one cluster (PirRBIII), due to low intracluster similarity (89%).

Seasonal variability of planctomycete 16S rRNA genes in Elbe River biofilms.

Figure 2 shows the monthly community profiles for 1 year (May 1997 to May 1998). For many of the bands identified strong seasonal variability was observed (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Typically, most of the bands occurred in several adjacent months rather than sporadically, indicating that there were relatively stable summer and winter populations. The greatest changes were seen in the transition phases between summer and winter (e.g., in May 1997 and November 1997). The biofilm fingerprints for May 1997 and January to May 1998 showed very similar patterns, which were therefore very likely caused by the same forces. As observed previously for beta-proteobacteria (4), bands assigned to the same cluster (e.g., bands 1 to 8 in cluster PlaRBI and bands 10 to 12 in cluster PlaRBII) did not always exhibit the same seasonal variability, which indicated that the corresponding clones belonged to different populations of microorganisms with separate ecological niches. Seasonal patterns were also observed for bands for which no clones were found (Fig. 2) and which were present especially in the warmer season. In the Elbe River, increases in temperature were correlated with increases in the chlorophyll concentration (Fig. 2B), which in turn may have selected for specifically adapted planctomycetes. The need for algae or their decomposition products for enrichment of planctomycetes is well known (7) and was directly observed for Planctomyces bekefii, which has not been cultured yet and accompanies algal or cyanobacterial blooms (24). Consequently, the recently completed genome of marine Pirellula sp. strain 1 (www.regx.de) contained a large number of open reading frames encoding enzymes required for degradation of plant detritus and algal polysaccharides (17).

The TGGE fingerprints presented here mainly show the seasonal variability of Planctomyces-related species and not the complete diversity of the planctomycete community or the absolute numbers of organisms represented by bands. However, due to the identical treatment of samples the changes in band intensity were most probably caused by shifts in community composition in the habitat, resulting in changes in the relative abundance of the 16S rRNA amplicon in question. Thus, our data show that the decrease in the abundance of Planctomycetales in the winter, revealed by fluorescent in situ hybridization previously, goes along with a partial change in the species composition of the community.

In this study we investigated the community composition and seasonal variability of planctomycetes in river biofilms, a group which has great ecological importance but currently is not well understood since most of the natural diversity has not been cultivated yet. Using the 16S rRNA approach, we identified globally distributed uncultivated freshwater clusters of planctomycetes. Moreover, we showed that the planctomycete community undergoes qualitative and quantitative changes during the different seasons, which might be partially related to changes in algal composition and biomass.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes to I.H.M.B.

We are grateful to all institutions and individuals who contributed data to the Arbeitgemeinschaft zur Reinerhaltung der Elbe. We thank the STAU (Federal Bureau of Environmental Protection) Magdeburg and especially S. Thieme for access to the measuring platform and the STAU Dessau for Spittelwasser River data. We thank K. Smalla for advice on TGGE. Critical discussions with and the advice of B. Engelen, I. Fritz, and G. Wieland were helpful.

REFERENCES

- 1.Battin, T. J., L. A. Kaplan, J. D. Newbold, and C. M. E. Hansen. 2003. Contributions of microbial biofilms to ecosystem processes in stream mesocosms. Nature 426:439-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böckelmann, U., W. Manz, T. R. Neu, and U. Szewzyk. 2000. Characterization of the microbial community of lotic organic aggregates (‘river snow’) in the Elbe River of Germany by cultivation and molecular methods. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 33:157-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brümmer, I. H. M., W. Fehr, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2000. Biofilm community structure in polluted rivers: abundance of dominant phylogenetic groups over a complete annual cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3078-3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brümmer, I. H. M., A. Felske, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2003. Diversity and seasonal variability of β-proteobacteria in biofilms of polluted rivers: analysis by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis and cloning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4463-4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crump, B. C., E. V. Armbrust, and J. A. Baross. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of particle-attached and free-living bacterial communities in the Columbia River, its estuary, and the adjacent coastal ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3192-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichner, C. A., R. W. Erb, K. N. Timmis, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 1999. Thermal gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of bioprotection from pollutant shocks in the activated sludge microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:102-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuerst, J. A. 1995. The planctomycetes: emerging models for microbial ecology, evolution, and cell biology. Microbiology 141:1493-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fürst, J. A., H. G. Gwilliam, M. Lindsay, A. Lichanska, G. Belcher, J. E. Vickers, and P. Hugenholtz. 1997. Isolation and molecular identification of planctomycete bacteria from postlarvae of the giant tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:254-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrity, G. M., and J. G. Holt. 2001. The roadmap to the manual, p. 119-166. In D. R. Boone and R. W. Castenholz (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. Springer, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannoni, S., and M. Rappé. 2000. Evolution, diversity, and molecular ecology of marine prokaryotes, p. 47-84. In D. L. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the ocean. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 11.Glöckner, F. O., E. Zaichikov, N. Belkova, L. Denissova, J. Pernthaler, A. Pernthaler, and R. Amann. 2000. Comparative 16S rRNA analysis of lake bacterioplankton reveals globally distributed phylogenetic clusters including an abundant group of actinobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5053-5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glöckner, F. O., M. Kube, M. Bauer, H. Teeling, T. Lombardot, W. Ludwig, D. Gade, A. Beck, K. Borzym, K. Heitmann, R. Rabus, H. Schlesner, R. Amann, and R. Reinhardt. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the marine planctomycete Pirellula sp. strain 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8298-8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hentschel, U., J. Hopke, M. Horn, A. B. Friedrich, M. Wagner, J. Hacker, and B. S. Moore. 2002. Molecular evidence for a uniform microbial community in sponges from different oceans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4431-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jetten, M. S., O. Sliekers, M. Kuypers, T. Dalsgaard, L. van Niftrik, I. Cirpus, K. van de Pas-Schoonen, G. Lavik, B. Thamdrup, D. Le Paslier, H. J. Op Den Kamp, S. Hulth, L. P. Nielsen, W. Abma, K. Third, P. Engstrom, J. G. Kuenen, B. B. Jorgensen, D. E. Canfield, J. S. Sinninghe Damste, N. P. Revsbech, J. Fuerst, J. Weissenbach, M. Wagner, I. Schmidt, M. Schmid, and M. Strous. 2003. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by marine and freshwater planctomycete-like bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 63:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kisand, V., and J. Wikner. 2003. Limited resolution of 16S rDNA DGGE caused by melting properties and closely related DNA sequences. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liesack, W., and E. Stackebrandt. 1992. Occurrence of novel groups of the domain Bacteria as revealed by analysis of genetic material isolated from an Australian terrestrial environment. J. Bacteriol. 174:5072-5078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neef, A., R. Amann, H. Schlesner, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1998. Monitoring a widespread bacterial group: in situ detection of planctomycetes with 16S rRNA-targeted probes. Microbiology 144:3257-3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nübel, U., B. Engelen, A. Felske, A. Snaidr, A. Wieshuber, R. I. Amann, W. Ludwig, and H. Backhaus. 1996. Sequence heterogeneities of genes encoding 16S rRNAs in Paenibacillus polymyxa detected by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 178:5636-5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sait, M., P. Hugenholtz, and P. H. Janssen. 2002. Cultivation of globally distributed soil bacteria from phylogenetic lineages previously only detected in cultivation-independent surveys. Environ. Microbiol. 4:654-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlesner, H., and E. Stackebrandt. 1986. Assignment of the genera Planctomyces and Pirella to a new family Planctomycetaceae fam. nov. and description of the order Planctomycetales ord. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 8:174-176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid, M., U. Twachtmann, M. Klein, M. Strous, S. Juretschko, M. Jetten, J. W. Metzger, K.-H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 2000. Molecular evidence for genus level diversity of bacteria capable of catalyzing anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speksnijder, A. G. C. L., G. A. Kowalchuk, S. De Jong, E. Kline, J. R. Stephen, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2001. Microvariation artifacts introduced by PCR and cloning of closely related 16S rRNA gene sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:469-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staley, J. T., J. A. Fuerst, S. Giovannoni, and H. Schlesner. 1992. The order Planctomycetales and the genera Planctomyces, Pirellula, Gemmata, and Isosphaera, p. 3710-3731. In A. Balows, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, K. H. Schleifer, and H. G. Trüper (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Starr, M. P., and J. M. Schmidt. 1989. Genus Planctomyces Gimesi 1924, p. 1946-1958. In J. T. Staley, M. P. Bryant, N. Pfennig, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 3. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strous, M., J. A. Fuerst, E. H. M. Kramer, S. Logemann, G. Muyzer, K. T. van de Pas-Schonen, R. I. Webb, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M Jetten. 1999. Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature 400:446-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vergin, K. L., E. Urbach, J. L. Stein, E. F. DeLong, B. D. Lanoil, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1998. Screening of a fosmid library of marine environmental genomic DNA fragments reveals four clones related to members of the order Planctomycetales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3075-3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Göbel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51:221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu, Y., V. M. Hayes, J. Osinga, I. M. Mulder, M. W. G. Looman, C. H. C. M. Buys, and R. M. W. Hofstra. 1998. Improvement of fragment and primer selection for mutation detection by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:5432-5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwart, G., B. C. Crump, M. P. Kamst-van Agterveld, F. Hagen, and S.-K. Han. 2002. Typical freshwater bacteria: an analysis of available 16S rRNA gene sequences from plankton of lakes and rivers. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 28:141-155. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwart, G., W. D. Hiorns, B. A. Methé, M. P. van Agterveld, R. Huismans, S. C. Nold, J. P. Zehr, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1998. Nearly identical 16S rRNA sequences recovered from lakes in North America and Europe indicate the existence of clades of globally distributed freshwater bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:546-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]