Abstract

Aim

To determine whether Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition) (Bayley-III) motor scores and neurological examination at 2 years' corrected age predict motor difficulties at 4.5 years' corrected age.

Method

A prospective cohort study of children born at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia in Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand. Assessment at 2 years was performed using the Bayley-III motor scale and neurological examination, and at 4.5 years using the Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition) (MABC-2).

Results

Of 333 children, 8 (2%) had Bayley-III motor scores below 85, and 50 (15%) had minor deficits on neurological assessment at 2 years; 89 (27%) scored less than or equal to the 15th centile, and 54 (16%) less than or equal to the 5th centile on MABC-2 at 4.5 years. Motor score, fine and gross motor subtest scores, and neurological assessments at 2 years were poorly predictive of motor difficulties at 4.5 years, explaining 0 to 7% of variance in MABC-2 scores. A Bayley-III motor score below 85 predicted MABC-2 scores less than or equal to the 15th centile with a positive predictive value of 30% and a negative predictive value of 74% (7% sensitivity and 94% specificity).

Interpretation

Bayley-III motor scale and neurological examination at 2 years were poorly predictive of motor difficulties at 4.5 years.

Movement and motor competence are essential in everyday tasks and participation in social life.1 Motor competence in early childhood is positively associated with the duration and intensity of physical activity in adolescence.2 Motor difficulties that cause low participation in physical activities in turn may lead to poor muscle strength, poor bone health, and obesity.3

Early screening for motor difficulties using assessment tools and routine neurological examination is performed regularly, especially in children born at risk of adverse outcomes,4,5 to guide the requirement for early supportive interventions. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (Bayley) have been widely used to assess neurodevelopment of children from 1 to 42 months of age.6 The third edition of the Bayley Scales (Bayley-III) includes a motor scale, which is commonly used as a test of motor function in research and clinical settings,7 although it was reported to underestimate rates of later motor difficulties in a cohort of 96 children born very preterm.8 Demands of tasks increase as children grow. Therefore, neurodevelopmental problems might become more evident as children get older,9 as has been demonstrated for cognitive function.10 Moreover, it is unclear if general neurological examination that is often part of assessment protocols in research and clinical settings at 2 years is itself predictive of later motor difficulties.

Therefore, we aimed to determine whether (1) Bayley-III motor score, and fine and gross motor subtest scores, and (2) routine neurological examination at 2 years predict motor difficulties at 4.5 years' corrected age in a large cohort of children born late preterm or at term and at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia.

Method

Participants

Participants were part of the CHYLD Study, a prospective cohort of children born at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia at Waikato Women's Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand, between 2006 and 2010.11 Infants were recruited to one of two neonatal studies, BABIES12 or Sugar Babies,13 owing to the presence of one or more of the following risk factors for neonatal hypoglycaemia: preterm (32–36 completed weeks' gestation), small (<2500g or <10th centile), large (>4500g or >90th centile), born to diabetic mothers, or other (poor feeding or sepsis). This study was limited to children born at or after 35 weeks' gestation and seen for follow-up at 2 and 4.5 years.

Neurodevelopmental assessments

Children and their families were invited to take part in a follow-up assessment at 2 years ± 4 weeks,11 and at 4.5 years ± 2 months corrected age. The assessment consisted of developmental tests administered by a trained examiner, vision assessment by an optometrist, and neurological, motor skills, and general health examinations by a trained doctor. All assessors were blinded to neonatal history and glycaemic status of children.

At 2 years ± 4 weeks' corrected age, children underwent Bayley-III and structured neurological examination, as previously described.11 Assessment at 4.5 years ± 2 months' corrected age included neurological examination and standardized tests of cognitive function (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence [3rd edition]), visual–motor integration (Beery–Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual–Motor Integration [6th edition]), and motor function (Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition [MABC-2]).

Bayley-III includes a motor score, and fine and gross motor subtest scores. The standardized mean motor score is 100 (SD 15), with scores lower than 85 indicating mild impairment, and lower than 70 indicating moderate or severe impairment. MABC-2 results include a total score and three subtest scores: manual dexterity, aiming and catching, and balance. Standardized mean MABC-2 standard score is 10 (SD 3), and recommended MABC-2 cut-offs are less than or equal to the 15th centile, indicating a child is at risk of motor difficulty, and less than or equal to the 5th centile, indicating the presence of significant motor difficulty.14

Neurological examination included assessment of tone, deep tendon reflexes, gait, and level of disability in children with cerebral palsy using the Gross Motor Function Classification System.15 Abnormal findings were defined as one or more of the following: decreased or increased tone or deep tendon reflexes, ankle clonus more than five beats, limited movements of hip abductors and extensors, toe walking (heels off the ground), asymmetrical gait. All abnormal findings were reviewed by a panel of study paediatricians (JMA, JEH, CJDMcK). Children with abnormal findings, but judged by the examiner and the study paediatricians to not have cerebral palsy, were classified as having minor neurological abnormalities.

Children were excluded from analysis if they had experienced significant head trauma that could have had an effect on neurodevelopment, or cerebral palsy diagnosed before or at the 2-year assessment.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using JMP Software, version 11.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 2013). Data are presented as mean (SD), median (interquartile range), or number (percentage).

Characteristics of children with MABC-2 scores above and at or below the 15th centile were compared using χ2 tests and one-way analysis of variance.

Linear regression was used to explore the relationship between Bayley-III motor score and MABC-2 total score, Bayley-III fine motor subtest score and MABC-2 manual dexterity score, and Bayley-III gross motor subtest score and MABC-2 aiming and catching and balance scores. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to assess the predictive value of Bayley-III motor scores for MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th and 5th centiles.

Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between neurological examination at 2 years and MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th centile at 4.5 years. Agreement between outcomes of 2- and 4.5-year examinations was assessed using κ agreement statistics.

Because it is possible that the assessment tasks for the Bayley-III motor scale involve cognitive and visual–motor integration skills as well as motor skills at 2 years, we also explored the association between Bayley-III motor scores and measures of cognitive function and visual–motor skills at 4.5 years using linear regression analysis.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Northern Y Health and Disability Ethics Committee (reference number NTY/10/03/021). Caregivers of children gave written informed consent before assessment at both 2 and 4.5 years.

Results

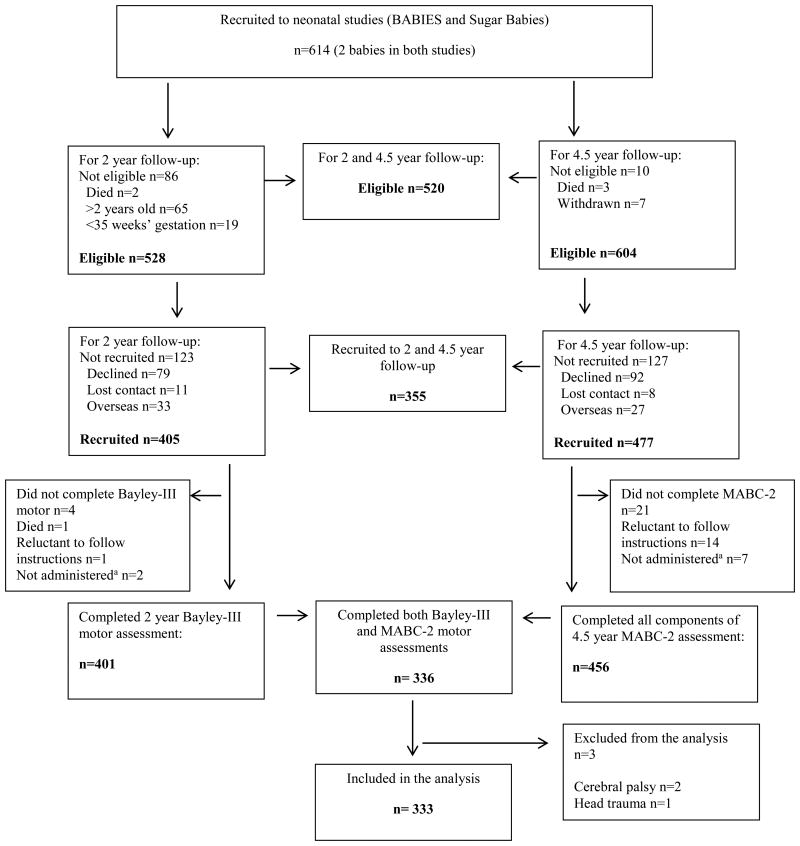

Of 614 children recruited to the neonatal studies, 86 were ineligible for 2-year follow-up, most because they were already older than 2 years when the study started, or because they were born before 35 weeks' gestation (Fig. 1). Compared with children who were eligible for 2-year follow-up, ineligible children had lower birthweight (2485g [SD 852] versus 3109g [854], p<0.0001, and gestational age 35.1 [2.6] versus 37.8 [1.7] wk, p<0.0001) but had similar sex distribution and socioeconomic status (data not shown). Sociodemographic and neonatal characteristics of children eligible and ineligible for 4.5-year follow-up were similar. Characteristics of children recruited and not recruited to 2-year follow-up did not differ, whereas at 4.5-year follow-up children not recruited were from more deprived areas than those recruited (New Zealand Deprivation index16 decile 7.2 [2.3] versus 6.4 [2.8], p=0.002).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants. MABC-2, Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition); Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition). aThe test was not administered because trained assessors were unable to assess the child in person (only questionnaire data obtained).

The median (interquartile range) Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence full-scale IQ was lower in children who did not complete the Bayley-III motor test (IQ 88 [74–97], n=3) or MABC-2 (IQ 86 [67–96], n=21) compared with those who did complete motor tests (IQ 98 [89–109]) at 4.5 years (Fig. 1).

Of 355 children who were assessed at 2 and 4.5 years, 352 completed 2-year Bayley-III motor assessments, 339 completed 4.5-year MABC-2, and 336 children completed both assessments (Fig. 1). Two children with cerebral palsy and one child who had experienced significant head trauma were excluded, leaving 333 children for analysis. The mean corrected age at assessments was 24 (SD 1.8) and 53 (1.8) months, respectively. Children with MABC-2 scores above and at or below the 15th centile at 4.5 years were similar in sex ratio, gestational age, birthweight, and neonatal risk factors for hypoglycaemia (Table I).

Table I. Characteristics of the study cohort.

| Characteristic | Cohort n=333 |

MABC-2 ≤15th centile at 4.5y | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yes n=89 |

No n=244 |

pa | ||

| Males | 171 (51) | 49 (55) | 122 (50) | 0.4 |

| Ethnicityb: | ||||

| New Zealand European | 165 (52) | 35 (41) | 130 (56) | |

| Maori | 115 (36) | 42 (49) | 73 (31) | |

| Pacific Islander | 11 (3) | 3 (4) | 8 (3) | |

| Other | 28 (9) | 5 (6) | 23 (10) | 0.03 |

| Neonatal risk factor:c | ||||

| Pre-term | 116 (35) | 33 (37) | 83 (34) | 0.60 |

| Infant of a diabetic mother | 134 (40) | 40 (45) | 94 (39) | 0.29 |

| Small | 92 (28) | 22 (25) | 70 (29) | 0.47 |

| Large | 91 (27) | 28 (31) | 63 (26) | 0.31 |

| Other | 11 (3) | 2 (2) | 9 (4) | 0.51 |

| Gestational age, wks | 38 (36–39) | 38 (36–39) | 38 (36–39) | 0.09 |

| Birthweight, g | 3006 (2485–3673) | 3010 (2500–3640) | 2998 (2471–3712) | 0.8 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 141 (42) | 44 (49) | 97 (40) | 0.14 |

| Bayley-III motor score | 99 (9) | 97 (8) | 100 (9) | 0.002 |

| WPPSI-III full-scale IQ | 98 (89–109) | 92 (81–102) | 101 (91–111) | <0.001 |

| New Zealand Deprivation index | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (4–9) | 0.02 |

| Maternal educationb: | ||||

| Secondary school | 95 (30) | 29 (36) | 66 (28) | |

| Tertiary | 218 (70) | 51 (64) | 167 (72) | 0.18 |

Data are number (%), mean (SD), or median (interquartile range). Bold type indicates significant result.

Comparing characteristics of children ≤15th and >15th centiles on MABC-2.

Data missing for 20 children

Risk factors not mutually exclusive.

MABC-2, Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition); Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition); WPPSI, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (3rd edition).

The mean Bayley-III motor score was 99 (SD 9.1). No child had a Bayley-III motor score lower than 70, and eight out of 333 (2%) had a score lower than 85 at 2 years. The mean MABC-2 total score at 4.5 years was 72 (14.4) and standard score 9 (3). A total of 89 out of 333 (27%) children had MABC-2 total scores at or below the 15th centile, and 54 out of 333 (16%) had total scores at or below the 5th centile. A mean difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 3.5 (1.3; 5.7; p=0.002) in Bayley-III motor score was found for children with MABC-2 total scores above and at or below the 15th centile (Table I).

Of the 89 children who had MABC-2 total scores at or below the 15th centile, 62 (70%) had scores at or below the 15th centile on manual dexterity, 23 (26%) on aiming and catching, and 69 (78%) on balance. Almost half of these children (43 of 89, 48%) had low scores on two subtests, and 11 of 89 (12%) on all three subtests of MABC-2. Minor neurological abnormalities were identified at neurological examination in 50 of 331 (15%) children at 2 years, and in 99 of 315 (31%) children at 4.5 years.

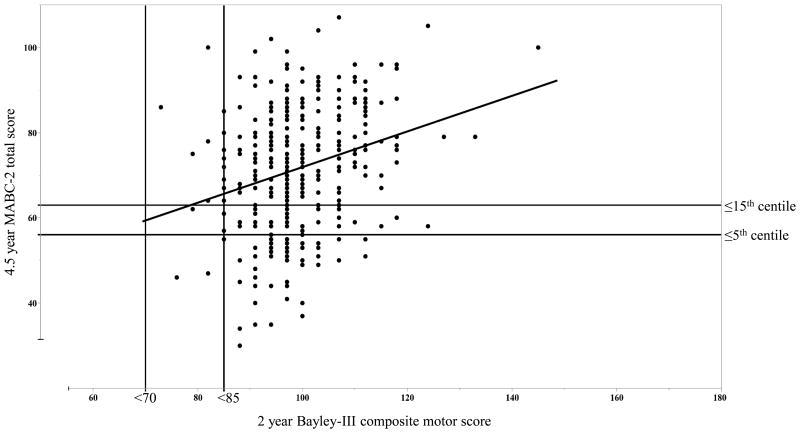

Of the 89 children with MABC-2 total scores at or below the 15th centile at 4.5 years, only three (2%) had a Bayley III motor score lower than 85 at 2 years. Similarly, of 54 children with total scores at or below the 5th centile at 4.5 years, only two (1%) had a Bayley III motor score lower than 85 at 2 years. Bayley-III motor scores at 2 years were significantly but weakly related to total MABC-2 scores at 4.5 years (β=0.4 [95% CI 0.3–0.6]; R2=0.07; p<0.0001; Fig. 2). There was also a weak association between Bayley-III motor scores and MABC-2 manual dexterity scores (β=0.8 [0.5–1.1]; R2=0.06; p<0.0001) and balance scores (β=0.7 [0.4–1.0]; R2=0.05; p<0.0001), but no association with aiming and catching scores (β=0.2 [−0.1 to 0.6]; R2=0.00; p=0.197). Bayley-III fine motor subtest scores were only weakly associated with MABC-2 manual dexterity scores at 4.5 years (β=2.7 [1.5–4.0]; R2=0.05; p<0.0001). Similarly, Bayley III gross motor subtest scores were only weakly associated with MABC-2 aiming and catching scores (β=1.8 [0.6–3.1]; R2=0.02; p=0.003) and balance scores (β=2.4 [1.2–3.5]; R2=0.04; p<0.0001) at 4.5 years.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of the relationship between 4.5-year MABC-2 total standard score and 2-year Bayley-III motor composite score. Regression line plotted (β=0.4 [95% CI 0.3–0.6]; R2=0.07; p<0.0001). Vertical lines indicate cut-off values of 70 (2 SD below mean) and 85 (1 SD below mean) on the Bayley-III motor scale. Horizontal lines indicate cut-off values of 5th and 15th centiles on the MABC-2 total scores. MABC-2, Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition); Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition).

The area under the Bayley III motor score receiver operating characteristic curve for MABC-2 score at or below the 15th centile was 0.62 (95% CI 0.56–0.67) and 0.62 (95% CI 0.57–0.67) for MABC-2 score at or below the 5th centile. A Bayley-III motor score lower than 85 identified children with MABC-2 total score at or below the 15th centile with a positive predictive value of 30% and negative predictive value of 74% (sensitivity of 7% and specificity 94%). The best combination of sensitivity (79%) and specificity (39%) was for a Bayley-III motor score cut-off below 100, which is the standardized test mean (Table II). The specificity and sensitivity of a Bayley-III motor cut-off lower than 85 was similar in children with different risk factors for hypoglycaemia (data not shown).

Table II. Characteristics of Bayley-III motor score cut-off values to predict motor impairment at 4.5y.

| Motor outcome at 4.5y | Bayley-III motor composite cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤15th centile on MABC-2 | 79 | 2 (0–8) | 99 (97–100) | 50 (7–93) | 74 (68–78) |

| 85 | 7 (3–14) | 94 (91–97) | 30 (12–54) | 74 (68–78) | |

| 100a | 79 (69–87) | 39 (33–45) | 32 (26–39) | 83 (75–90) | |

| ≤5th centile on MABC-2 | 79 | 2 (0–10) | 99 (97–100) | 25 (1–81) | 84 (80–88) |

| 85 | 6 (1–15) | 94 (90–96) | 15 (3–38) | 84 (79–88) | |

| 100a | 83 (71–92) | 38 (32–44) | 21 (15–27) | 92 (86–96) |

Data are composite scores and percentages (95% confidence intervals).

Cut-off with the optimal sensitivity and specificity to predict MABC-2 motor scores ≤15th centile and ≤5th centile at 4.5y corrected age. There were no children with motor scores <70 on Bayley-III at 2y. Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition); MABC-2, Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition).

Bayley-III motor scores were only weakly associated with full-scale IQ at 4.5 years (β=0.5 [95% CI 0.3–0.6]; R2=0.09; p<0.0001). Similarly, Bayley-III fine motor subset scores were only weakly associated with full-scale IQ at 4.5 years (β=1.8 [1.2–2.4]; R2=0.09; p<0.0001), and there was no association between Bayley-III gross motor subset score and full-scale IQ (β=0.6 [−0.1 to 1.2]; R2=0.01; p=0.078) There was also no association between Bayley-III motor scores, or fine and gross motor subset scores, and Beery–Buktenica Visual Motor Integration scores at 4.5 years (motor score; β=0.2 [−0.4 to 0.8]; R2=−0.01; p=0.540).

Children with minor neurological abnormality at 2 years had similar MABC-2 scores to those who had a normal neurological examination, and were not at increased risk of MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th centile at 4.5 years (OR=1.7; 95% CI 0.9–3.12; p=0.124). Further, there was only slight agreement between the outcomes of 2- and 4.5-year neurological examinations (κ=0.10 [95% CI 0.00–0.21]). Of 313 children who had neurological examination at 2 and 4.5 years, 21 (7%) had minor abnormalities at both assessments, 26 out of 47 (55%) children with minor abnormalities at 2 years had no abnormalities at 4.5 years, and 78 out of 99 (79%) with minor abnormalities at 4.5 years had none at the 2-year assessment. At 2 years, the presence of a minor neurological abnormality had positive and negative predictive values (95% CI) for a neurological abnormality at 4.5 years of 45% (30–60) and 71% (65–76), respectively.

Discussion

We found that Bayley-III motor scores, including fine and gross motor subtest scores, at 2 years are poorly predictive of motor difficulties at 4.5 years, as detected by MABC-2, in children born at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia. Routine neurological examination at 2 years also did not predict motor difficulties at 4.5 years. More children were identified at risk of motor difficulty at 4.5 years than at 2 years.

Possible explanations of our results are inability of Bayley-III to assess skilled motor function, appearance of motor problems only later in childhood, or variability of motor skills as children grow. Serial assessments of motor performance up to 2 years of age using Bayley-III or II have shown relatively stable or decreasing rates of motor difficulties.17,18 However, few studies have followed children beyond 2 years, and in studies where motor function is assessed in later life, a different motor test is required after the age of 42 months.

It is possible that the Bayley-III motor score measures functions that are part of overall development rather than specific motor function defined as a motor competence or skilled movement.14 The fine motor subtest evaluates ocular–motor control, hand and finger movements, reaching and grasping, pre-writing skills, and use of tools (blocks, scissors, etc.). The gross motor subtest evaluates skills that are important for movement and play: head control, rolling, sitting, walking, and balance. All of these skills are essential for future skilled motor performance, but many are not purposeful at 2 years, whereas MABC-2 includes timed and graded tasks that require accurate and skilled movement and the ability to plan actions and correct errors to achieve a goal. Therefore, as test demands increase, motor difficulties may become more evident.

It is also possible that motor difficulties are not apparent until a later stage of development. In one prospective study of 50 children born before 29 weeks' gestation or less than 1000g, who did not have cognitive or neurological deficits, or vision and hearing problems at 12 months' corrected age, the prevalence of gross motor impairment assessed using the Peabody Developmental Motor Scale increased from 14% at 18 months to 33% at 3 years and 81% at 5 years, while impairment in fine motor function was found in 54%, 47%, and 64% of children, respectively.19 Our results show that Bayley-III motor scores and fine motor subtest scores explained a similar proportion of the variance in cognitive score at 4.5 years (9%) and in MABC-2 motor scores (7%), suggesting that the Bayley-III motor scale is not assessing skills that relate specifically to either later cognitive or motor function. In studies assessing predictive validity of Bayley-III cognitive and language scales, both were related to 4-year IQ (correlation coefficients 0.81 and 0.78 respectively),20 but Bayley-III cut-offs below 85 did not have strong sensitivity and specificity to detect developmental delay at 4 years.21

The variability of a child's motor development has been described in many studies of high-risk children born preterm or with low birthweight, but the direction of these changes is not clear. For example, the prevalence of motor difficulties increased from 3 to 5 years of age,19 while in another study motor impairment improved from 6 to 8 years, and was then relatively stable at 12 to 13 years.22 Furthermore, in full-term low-risk children, gross motor scores were more stable between 21 months and 4 years using the Peabody Developmental Motor Scale (70% of children remained in the same category) compared with fine motor scores (36% of children had stable scores).23 Similarly, meta-analysis of reports of motor development of very preterm and very low birthweight children found that up to 2 years children catch up to comparison groups in motor development measured by Bayley Scales, but then motor proficiency declines during elementary school and adolescence when measured by MABC.24 Therefore, it is not clear whether the reported changes are due to variability of children's motor development, or to different requirements of the tests used at different ages.

In previous studies, the predictive value of early motor testing for later motor outcomes has been mixed. An Australian study showed that motor difficulties on MABC-2 at 4 years were accurately predicted by two tests administered at 4, 8, and 12 months to children born preterm.25 The Alberta Infant Motor Scale scores at 4 months most accurately predicted MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th and 5th centiles at 4 years (accuracy 79%), while the Neuro-sensory Motor Developmental Assessment at 12 months most accurately predicted cerebral palsy at 4 years (accuracy 77%).25 However, in a prospective study of healthy term-born children, scores of motor function tests administered at a mean age of 10 days, 12 weeks, and 18 months were not associated with motor outcomes at school age (mean 6y 1mo).26 Therefore, accuracy of prediction of preschool and school motor performance may depend on the tests used in assessments and the study population.

Both positive and negative predictive values were poor for the cut-off of a Bayley-III score below 85, although there were only eight children with scores below this at 2 years. Therefore, we investigated whether a different cut-off for Bayley-III motor scores would better predict later motor difficulties. We found that the sum of sensitivity and specificity for predicting motor difficulties at 4.5 years was maximal at a cut-off below 100, which is the test mean, but predictive value was still poor. Recent studies have found that Bayley-III underestimated developmental delay compared with the previous edition, Bayley-II.27 Further, Bayley-II has also been reported to have poor predictive validity for later developmental delays.28 An alternative cut-off of below 73 was suggested for Bayley-III motor score instead of below 85 to improve sensitivity and specificity for identifying motor difficulties at 18 to 22 months' corrected age in babies born before 27 weeks' gestation.7 In another study that used the same motor tests as our study, 2-year Bayley-III motor score cut-offs of below 97 and below 94 were considered optimal to identify at risk and significant movement difficulty respectively in 4-year-old children born very preterm.8 Those proposed motor cut-offs had slightly lower sensitivity (74% for at or below the 15th and 78% for at or below the 5th MABC-2 centiles) but higher specificity (77% for both) compared with that found for the below 100 cut-off in our study (sensitivity 79% for at or below the 15th and 83% for at or below the 5th MABC-2 centiles, specificity 39% and 38%).

Routine neurological examination has been shown to predict major neurological deficits such as cerebral palsy.29 However, data on the ability of neurological examination to predict mild and moderate motor impairment are limited. We found that neurological examination at 2 years was not predictive of motor outcomes at 4.5 years. In a study of 5-year-olds, similar results were found for paediatric overall judgement (at risk, abnormal, or optimal categories) with a sensitivity of paediatric examination to detect motor difficulties of 19% and specificity of 98%.30 Moreover, in our study there was only slight agreement between 2- and 4.5-year neurological examinations. Our data suggest that, although routine neurological examination at 2 years may be useful in detecting major neurological deficits, it is not a useful tool for predicting skilled motor performance or minor neurological abnormalities in children at 4.5 years.

Study limitations

We do not have MABC-2 reference values for New Zealand children. Moreover, the CHYLD cohort comprises children born at risk of hypoglycaemia and our findings might not be applicable to the general population. We also do not know the incidence of MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th and 5th centiles in children born without risk factors for hypoglycaemia. Further research is needed to understand motor function and assessment of motor difficulties in typically developing children.

The reference population on which MABC-2 norms are based comprises 1172 children from the UK,14 and may differ from the population in our study. For example, Dutch children performed better on the MABC-2 than the reference population,31 although total scores of 3- to 6-year-old children were similar to the reference population. Further, the prevalence of children with MABC-2 scores at or below the 15th centile was greater than the reference norms for 3- to 6-year-olds and lower for 7- to 10-year-olds and 11- to 16-year-olds. Nevertheless, MABC-2 is the most widely used test of motor performance in children,32 and other studies have reported good intraclass correlation coefficient, test–retest reliability, and internal consistency, and to be able to discriminate typically developing children from those with motor difficulties.32–34

The poor agreement in neurological status between 2 and 4.5 years could be partly due to examination by different assessors. However, all examiners were experienced in assessing young children and followed a common examination protocol.

Conclusions

Bayley-III motor scores at 2 years were poorly predictive of MABC-2 motor scores at 4.5 years in this cohort of children at risk, even when alternative cut-off values were used. Neurological examination at 2 years also did not predict later motor difficulties. Bayley-III motor scale and neurological examination at 2 years may be of limited utility in routine follow-up assessments of children at risk of adverse long-term neurological and skilled motor performance outcomes.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Two-year Bayley-III motor scores were poorly predictive of motor difficulties at 4.5 years.

Minor deficits on neurological examination at 2 years also did not predict motor difficulties at 4.5 years.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank CHYLD study team (Appendix S1). This research was supported by grants from The Health Research Council of New Zealand and Auckland Medical Research Foundation. The project described was supported by Grant Number R01HD069622 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. Funding bodies did not take part in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, or publication decisions. Additional information is available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- Bayley-III

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (3rd edition)

- MABC-2

Movement Assessment Battery for Children (2nd edition)

Footnotes

The authors have stated that they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Supporting Information: The following additional material may be found online: Appendix S1: Further acknowledgements.

References

- 1.Bart O, Jarus T, Erez Y, et al. How do young children with DCD participate and enjoy daily activities? Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett LM, van Beurden E, Morgan PJ, et al. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boreham C, Riddoch C. The physical activity, fitness and health of children. J Sports Sci. 2001;19:915–29. doi: 10.1080/026404101317108426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyen T, Lui K. Developmental coordination disorder in “apparently normal” school children born extremely preterm. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:298–302. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.134692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolaños L, Matute E, Ramírez-Dueñas MDL, et al. Neuropsychological impairment in school-aged children born to mothers with gestational diabetes. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:1616–24. doi: 10.1177/0883073815575574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan AF, Bann C, Boatman C, et al. Do currently recommended Bayley-III cutoffs overestimate motor impairment in infants born <27 weeks gestation? J Perinatol. 2015;35:516–21. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spittle AJ, Spencer-Smith MM, Eeles AL, et al. Does the Bayley-III motor scale at 2 years predict motor outcome at 4 years in very preterm children? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:448–52. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser JR, Bai S, Gibson N, et al. Association between transient newborn hypoglycemia and fourth-grade achievement test proficiency: a population-based study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:913–21. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elgen I, Sommerfelt K, Ellertsen B. Cognitive performance in a low birth weight cohort at 5 and 11 years of age. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:111–6. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinlay CJD, Alsweiler JM, Ansell JM, et al. Neonatal glycemia and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1507–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris DL, Battin MR, Williams CE, et al. Cot-side electro-encephalography and interstitial glucose monitoring during insulin-induced hypoglycaemia in newborn lambs. Neonatology. 2009;95:271–8. doi: 10.1159/000166847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Signal M, Chase JG, Harding JE. Dextrose gel for neonatal hypoglycaemia (the Sugar Babies study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:2077–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson SE, Sugden DA, Barnett AL. Movement Assessment Battery for Children. 2nd. London, UK: Psychological Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, et al. Content validity of the expanded and revised gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:744–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmond C, Crampton P, King P, et al. NZiDep: a New Zealand index of socioeconomic deprivation for individuals. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1474–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koseck K, Harris SR. Changes in performance over time on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II when administered to infants at high risk of developmental disabilities. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2004;16:199–205. doi: 10.1097/01.PEP.0000145910.38982.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene MM, Patra K, Silvestri JM, et al. Re-evaluating preterm infants with the Bayley-III: patterns and predictors of change. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:2107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goyen T, Lui K. Longitudinal motor development of “apparently normal” high-risk infants at 18 months, 3 and 5 years. Early Hum Dev. 2002;70:103–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bode MM, D'Eugenio DB, Mettelman BB, et al. Predictive validity of the Bayley, third edition at 2 years for intelligence quotient at 4 years in preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35:570–5. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer-Smith MM, Spittle AJ, Lee KJ, et al. Bayley-III cognitive and language scales in preterm children. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1258–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powls A, Botting N, Cooke RWI, et al. Motor impairment in children 12 to 13 years old with a birthweight of less than 1250 g. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73:F62–6. doi: 10.1136/fn.73.2.f62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darrah J, Magill-Evans J, Volden J, et al. Scores of typically developing children on the peabody developmental motor scales-infancy to preschool. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2007;27:5–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, et al. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:2235–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spittle AJ, Lee KJ, Spencer-Smith M, et al. Accuracy of two motor assessments during the first year of life in preterm infants for predicting motor outcome at preschool age. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roze E, Meijer L, Van Braeckel KNJA, et al. Developmental trajectories from birth to school age in healthy term-born children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1134–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, et al. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:352–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, et al. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:333–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heineman KR, Hadders-Algra M. Evaluation of neuromotor function in infancy – a systematic review of available methods. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:315–23. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318182a4ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Kleine MJK, Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden MWG, Den Ouden AL. Is paediatric assessment of motor development of very preterm and low-birthweight children appropriate? Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1202–8. doi: 10.1080/08035250500525301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niemeijer AS, van Waelvelde H, Smits-Engelsman BCM. Crossing the North Sea seems to make DCD disappear: cross-validation of Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 norms. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;39:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuang Y, Su J, Su C. Reliability and responsiveness of the Movement Assessment Battery for Children–Second Edition Test in children with developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:160–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valentini NC, Ramalho MH, Oliveira MA. Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2: translation, reliability, and validity for Brazilian children. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:733–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellinoudis T, Evaggelinou C, Kourtessis T, et al. Reliability and validity of age band 1 of the Movement Assessment Battery for Children – Second Edition. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1046–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.